Abstract

Four metabolites were identified upon incubation of brevetoxin (PbTx-2) with human liver microsomes. Chemical transformation of PbTx-2 confirmed the structures of three known metabolites BTX-B5, PbTx-9 and 41, 43-dihydro-BTX-B5 and a previously unknown metabolite, 41, 43-dihydro-PbTx-2. These metabolites were also observed upon incubation of PbTx-2 with nine human recombinant cytochrome P450s (1A1, 1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, 3A4 and 3A5). Cytochrome P450 3A4 produced oxidized metabolites while other CYPs generated the reduced products.

Keywords: brevetoxins, PbTx-2, metabolism, cytochrome P450, human liver microsome

Brevetoxins, produced by the “Florida red tide” dinoflagellate Karenia brevis, are a suite of neurotoxins which are responsible for massive fish kills and marine mammal mortalities (Landsberg et al., 2009). In humans, the brevetoxins are responsible for a syndrome known as Neurotoxic Shellfish Poisoning (NSP) which results from the consumption of tainted shellfish (Watkins et al., 2008) as well as respiratory distress in beachgoers upon exposure to aerosolized toxins (Fleming et al., 2005). Brevetoxin PbTx-2 (Fig. 1) is the primary constituent of this suite of toxins.

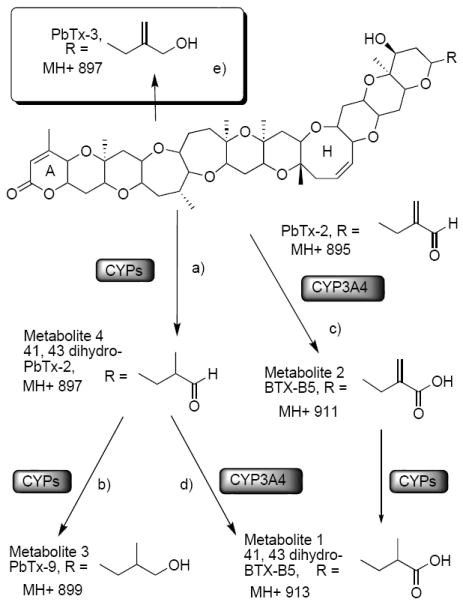

FIG. 1.

Enzymatic and chemical conversion of PbTx-2. a) H2/5% Pd-BaSO4, THF, 0 °C, 32 psi, 2 h; b) NaBH4, CH3CN, rt, 0.5 h; c) NaClO2, Na2HPO4, 2-methyl-2-butene, t-BuOH, RT, 4 h; d) NaClO2, Na2HPO4, 2-methyl-2-butene; t-BuOH, RT, 4 h; e) NaBH4, CeCl3·6H2O, MeOH, rt, 0.5 h.

Several studies of brevetoxin excretion and metabolism in mammals have demonstrated that the hepatobiliary system plays a key role in the detoxification and elimination of brevetoxins. Radwan found that in rats, PbTx-2 is rapidly detoxified and excreted in urine as cysteine conjugates and an unidentified oxidized metabolite. (Radwan et al., 2005) On the other hand, when fed to rats, [3H]-PbTx-3, which is unable to form cysteine conjugates, is eliminated in both the urine and feces. (Poli, et al., 1990; Cattet and Geraci, 1993) Radioimmunoassay of urine from two patients in Florida suffering from NSP showed brevetoxin-like activity which was later confirmed by LC-MS to be due to the presence of PbTx-3 and other unidentified metabolites. (Poli et al., 2000)

Wang reported the conversion of PbTx-2 to PbTx-3 and the hydrolyzed A-ring lactone by rat liver microsomes. (Wang et al., 2005) Later Radwan examined the metabolic activities of purified cDNA-expressed rat liver cytochrome P-450 (CYP) enzymes toward PbTx-2. All six CYPs studied (CYP1A2, CYP2A2, CYP2C11, CYP2D1, CYP2E1, and CYP3A1) were capable of metabolizing PbTx-2 to varying degrees. The metabolites produced by CYPs 1A2 and 3A1 were assigned on the basis of LC-MS analysis as PbTx-3, PbTx-9, BTX-B5 and the 27, 28-diol of PbTx-2. (Radwan and Ramsdell, 2006) Several additional metabolites were observed upon incubation with rat liver hepatocytes including: the H-ring epoxides of PbTx-2 and PbTx-3; the corresponding diols and two A-ring hydrolyzed products. Recently, Abraham (Abraham et al., 2008) assayed brevetoxin metabolites in urine from seventeen NSP patients and characterized them on the basis of LC-MS/MS as PbTx-3 and 27, 28-epoxy PbTx-3. Additionally, a previously unknown metabolite was tentatively assigned on the basis of MS fragmentation, as 41, 43-dihydro-BTX-B5.

In this communication, we describe the production of 4 metabolites by incubation of PbTX-2 with human liver microsomes and nine human recombinant cytochrome P450s (1A1, 1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, 3A4 and 3A5). These metabolites, which include 41, 43-dihydro-BTX-B5 and a previously unidentified metabolite, have been definitively characterized by chemical conversion of PbTx-2.

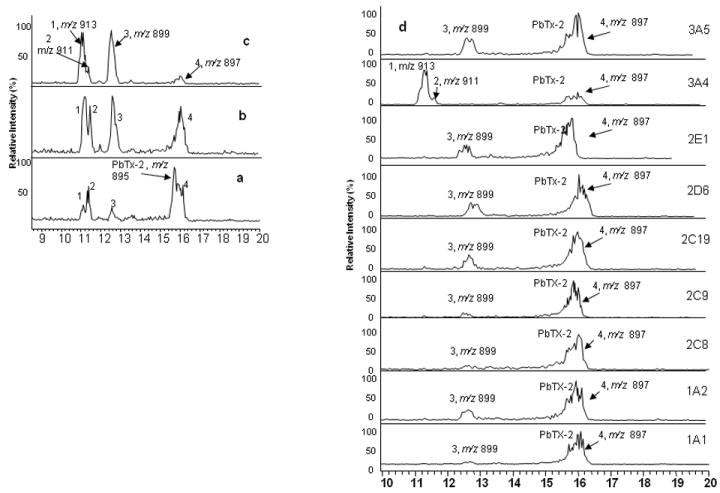

PbTx-2 was incubated with pooled human liver microsomes (HLM) and the reactions were monitored by LC-MS. The total ion current chromatogram obtained from the positive ion ESI LC-MS analysis of the reaction mixture after incubation of PbTx-2 with HLM for 30, 60, 180 min is shown in Fig. 2b-c. Four new peaks in the LC-MS profile of the reaction mixture were observed, including three (metabolite 1, tR 11.03 min; metabolite 2, tR 11.38 min; metabolite 3, tR 12.53 min) eluting before PbTx-2 (m/z 895, tR 15.68 min) and one peak (metabolite 4, tR 15.99 min) eluting after PbTx-2. The positive ESI full-scan mass spectrum of metabolites 1-4 produced molecular ion peaks [M+H]+ at m/z 913, 911, 899 and 897, respectively. This result suggested that metabolites 1 and 2 are oxidation products, while metabolites 3 and 4 result from reduction. Metabolites 2 and 4 were major peaks after 30 minutes of incubation, while metabolite 1 and 3 increased after 60 min. Metabolites 1 and 3 appeared as the major constituents and metabolite 4 was nearly gone at a reaction time of 180 min. This suggested that metabolite 4 may be an intermediate during PbTx-2 metabolism by human liver.

FIG. 2.

Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of metabolic products of 50 μM PbTx-2 incubated with pooled human liver microsomes (1 mg/mL) (a) 30 min. (b) 60 min. (c) 180 min. (d) Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of metabolic products of 50 μM PbTx-2 incubated for 30 min with 50 pmol CYPs.

PbTx-2 was also incubated with nine recombinant human cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP1A1, 1A2, 2C8, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, 2E1, 3A4 and 3A5). LC-MS analysis revealed that all nine enzymes are capable of metabolizing PbTx-2. Fig. 2d shows that CYP3A4 converts PbTx-2 to metabolites 1, 2 and 4, while the other enzymes convert PbTx-2 to metabolites 3 and 4 only. This result suggested that CYP3A4 is involved in the oxidation of PbTx-2 while the other CYPs catalyzed two reduction reactions.

Metabolite 4 is an important intermediate which appeared in all reactions. A difference of 2 in the m/z ratios for the molecular ion peaks of metabolite 4 when compared to PbTx-2 (m/z 895) is suggestive of a reduction of the PbTx-2 molecule. PbTx-3 (m/z 897) has been identified as a metabolite in the incubation of PbTx-2 with rat liver microsomes (Wang et al., 2005), rat hepatocytes (Radwan and Ramsdell, 2006) and in human urine (Abraham et al., 2008). However, the HPLC retention time of metabolite 4 did not correspond to that of PbTx-3 (m/z 897, tR 11.81 min, data not shown) which was slightly shorter than PbTx-2 (tR 15.68 min). Whereas the retention time of metabolite 4 (m/z 897, tR 15.99 min) was slightly longer than PbTx-2. A standard of 41, 43-dihydro-PbTx-2 was prepared by reduction of PbTx-2 with Pd on BaSO4 according to the method described by Lin. (Lin et al., 1981). Comparison of metabolite 4 with the semi-synthetic 41, 43-dihydro-PbTx-2 by LC-MS indicated that the two were identical. Furthermore, metabolite 4 may be converted to PbTx-9 by sodium borohydride reduction. These observations confirm that metabolite 4 is 41, 43-dihydro-PbTx-2. This metabolite has not been reported in earlier studies either in rat or humans. Metabolite 3 was identified as PbTx-9 by comparison with standard which was prepared by the reduction of PbTx-2 with NaBH4 in acetonitrile. As we did not observe any PbTx-3 in these reactions, we conclude that metabolite 3 (PbTx-9) was generated from the reduction of metabolite 4.

Two additional metabolites, 1 and 2 which produced molecular ion peaks [M+H]+ at m/z 913 and 911, were presumed oxidation products. Metabolite 2 has difference of 16 in the m/z ratio when compared to PbTx-2. Metabolite 2 was identical to BTX-B5 (Ishida et al., 2004) which was generated by the oxidation of PbTx-3 with NaClO2 according to the method described by Michelliza (Michelliza et al., 2007).

Metabolite 1 has same m/z as that of hydrolyzed A ring PbTx-2 which was reported earlier by Wang (Wang et al., 2005). However, the retention time of metabolite 1 differed from that of synthetic open A ring PbTx-2 (m/z 913, tR 10.04 min, data not shown) which was prepared as previously described (Roth et al., 2007). However, the oxidation of 41, 43-dihydro-PbTx-2 (metabolite 4) with NaClO2, yielded 41, 43-dihydro-BTX-B5, which was found to be identical to metabolite 1 and was tentatively identified by Abraham (Abraham et al., 2008).

This is the first study of metabolism of brevetoxins using human cytochrome P450 enzymes. Earlier studies were performed using rat enzymes (Radwan and Ramsdell, et al., 2006 and Wang, et al., 2005) and one study (Abraham, et al., 2008) identified metabolites in human urine. This work links a human xenobiotic metabolizing enzyme, with a specific metabolite. CYP3A4 was involved in the oxidation of the substrate, while other CYPs catalyzed two reduction reactions. A previously unknown metabolite (41, 43-dihydro-PbTx-2), has been identified which is incapable of forming the types of conjugates described by Abraham (Abraham, et al., 2008) and would thus not be readily excreted. Moreover, 41, 43-dihydro-BTX-B5 was confirmed as a metabolite. The characterization of all metabolites produced from a xenobiotic is crucial to understanding its range of toxicity, because diet, environment, gender, age, health, prior exposure to xenobiotics and genetic polymorphisms in liver xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in humans will influence metabolism and susceptibility in different populations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Grant S11 ES11181, and the NSF-NIEHS Oceans and Human Health Center Program (National Science Foundation grant 0432368 and NIEHS grant P50 ES12736-01).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary information: Supplementary data associated with this article including experimental details may be found at XXXXXXX

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abraham A, Plakas SM, Flewelling LJ, El Said KR, Jester ELE, Granade HR, White KD, Dickey RW. Biomarkers of neurotoxic shellfish poisoning. Toxicon. 2008;52:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2008.04.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cattet M, Geraci JR. Distribution and elimination of ingested brevetoxin (PbTx-3) in rats. Toxicon. 1993;31:1483–1486. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(93)90214-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming LE, Backer LC, Baden DG. Overview of aerosolized florida red tide toxins: exposures and effects. Environ Health Perspect. 2005;113(5):618–620. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida H, Nozawa A, Hamano H, Naoki H, Fujita T, Kaspar HF, Tsuji K. Brevetoxin B5, a new brevetoxin analog isolated from cockle Austrovenus stutchburyi in New Zealand, the marker for monitoring shellfish neurotoxicity. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Landsberg JH, Flewelling LJ, Naar J. Karenia brevis red tides, brevetoxins in the food web, and impacts on natural resources: decadal advancements. Harmful Algae. 2009;8(4):598–607. [Google Scholar]

- Lin YY, Risk M, Ray SM, Van Engen D, Clardy J, Golik J, James JC, Nakanishi K. Isolation and structure of brevetoxin B from the red tide dinonagellate Gymnodinium breve. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:6773–6775. [Google Scholar]

- Michelliza S, Abraham WM, Jacocks HM, Schuster T, Baden DG. Synthesis, modeling, and biological evaluation of analogues of the semisynthetic brevetoxin antagonist β-naphthoyl-brevetoxin. Chem BioChem. 2007;8:2233–2239. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200700317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli MA, Templeton CB, Thompson WL, Hewetson JF. Distribution and elimination of the brevetoxin PbTx-3 in rats. Toxicon. 1990;28:903–910. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(90)90020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poli MA, Musser SM, Dickey RW, Eilers PP, Hall S. Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning and brevetoxin metabolites: a case study from Florida. Toxicon. 2000;38:981–993. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(99)00191-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth PB, Twiner MJ, Wang Z, Dechraoui MYB, Doucette GJ. Fate and distribution of brevetoxin (PbTx) following lysis of Karenia brevis by algicidal bacteria, including analysis of open A-ring derivatives. Toxicon. 2007;50:1175–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan FFY, Wang Z, Ramsdell JS. Identification of a rapid detoxification mechanism for brevetoxin in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2005;85:839–846. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radwan FFY, Ramsdell JS. Characterization of in vitro oxidative and conjugative metabolic pathways for brevetoxin (PbTx-2) Toxicol Sci. 2006;89:57–65. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfj013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Hua Y, Wang G, Cole RB. Characterization of rat liver microsomal and hepatocytal metabolites of brevetoxins by liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2005;383:67–75. doi: 10.1007/s00216-005-3323-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins SM, Reich A, Fleming LE, Hammond R. Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning. Mar Drugs. 2008;6(3):431–455. doi: 10.3390/md20080021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.