Abstract

Genes include cis-regulatory regions that contain transcriptional enhancers. Recent reports have shown that developmental genes often possess multiple discrete enhancer modules that drive transcription in similar spatio-temporal patterns1-4: primary enhancers located near the basal promoter and secondary, or “shadow”, enhancers located at more remote positions. It has been hypothesized that the seemingly redundant activity of primary and secondary enhancers contributes to phenotypic robustness1,5. We tested this hypothesis by generating a deficiency that removes two newly-discovered enhancers of shavenbaby (svb), a gene encoding a transcription factor that directs development of larval trichomes6. At optimal temperatures for embryonic development, this deficiency causes minor defects in trichome patterning. In embryos that develop at both low and high extreme temperatures, however, absence of these secondary enhancers leads to extensive loss of trichomes. These temperature-dependent defects can be rescued by a transgene carrying a secondary enhancer driving transcription of the svb cDNA. Finally, removal of one copy of wingless, a gene required for normal trichome patterning7, causes a similar loss of trichomes only in flies lacking the secondary enhancers. These results support the hypothesis that secondary enhancers contribute to phenotypic robustness in the face of environmental and genetic variability.

The cis-regulatory region of the svb gene integrates inputs from multiple gene regulatory networks to generate a complex pattern of transcription in the embryonic epidermis of insect species6,8. Svb protein then activates many downstream genes, ultimately resulting in trichome morphogenesis9,10. Three enhancer modules located in a 50 Kb region upstream of the svb transcription start site (called 7, E, and A) together recapitulate the complete svb epidermal expression pattern11. Partial loss of function of all three enhancers led to the evolutionary loss of the long, thin quaternary trichomes (indicated in Fig. 1a and 2a) on first-instar larvae of D. sechellia, a species that is closely related to D. melanogaster11. Evolution of svb expression patterns has probably also contributed to parallel loss of quaternary trichomes in the D. virilis group, species of which are distantly related to D. melanogaster12.

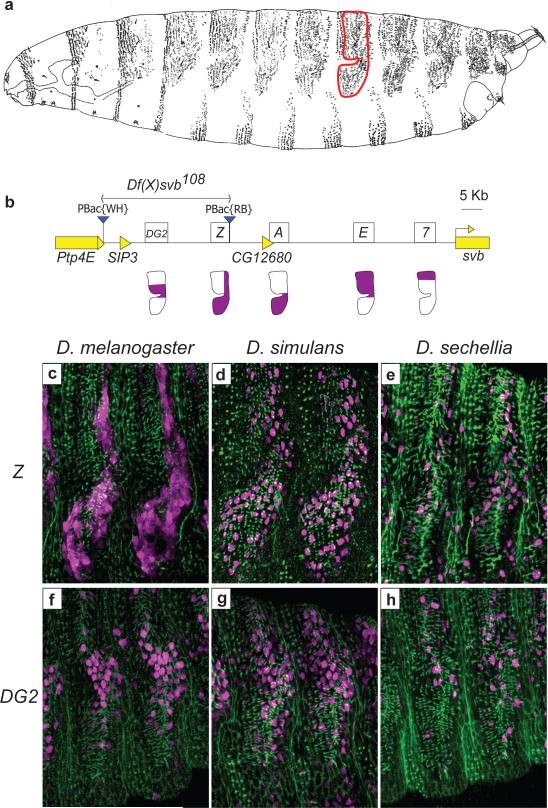

Figure 1. The svb cis-regulatory region in D. melanogaster.

a, Drawing from the lateral perspective of a D. melanogaster first instar larva. The domain producing quaternary trichomes on the fifth abdominal segment is enclosed in a red outline. b, Diagram of the region upstream of the svb first exon, showing the positions of the five enhancers for this locus: DG2, Z, A, E, and 7. The expression driven by these enhancers in quaternary cells is shown in purple in the diagrams below each enhancer. The piggyBac elements used to generate Df(X)svb108 are shown as blue triangles. c,f, Expression pattern driven by D. melanogaster Z::lacZ (c) and DG2::lacZ (f) in the 5th and 6th abdominal segments of a stage-15 embryo (purple). An anti-Dusky-like antibody was used to stain developing trichomes (green). d,g, Expression pattern driven by D. simulans Z::lacZ (d) and DG2::lacZ (g). e,h, Expression pattern driven by D. sechellia Z::lacZ (e) and DG2::lacZ (h). β-galactosidase protein produced by D. melanogaster Z::lacZ is expressed in the cytoplasm; β-galactosidase from all other constructs is localized to the nucleus.

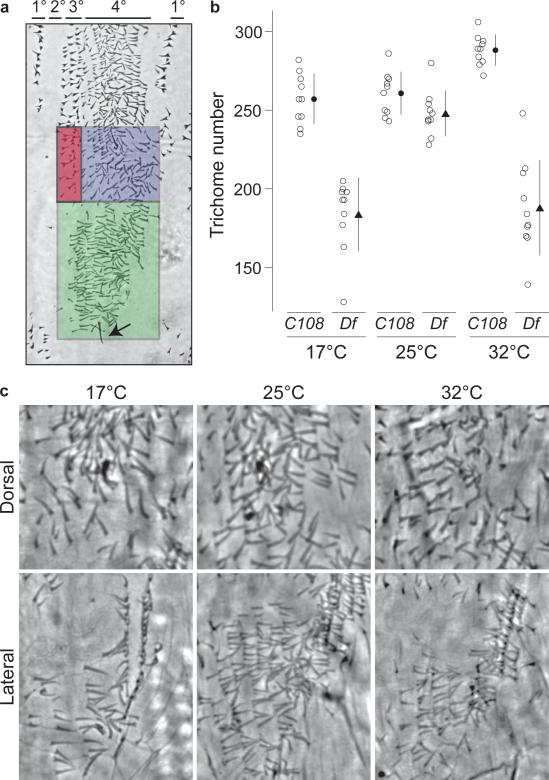

Figure 2. Effect of Df(X)svb108 on the number of quaternary trichomes.

a, The lateral patch (green) and dorsal region (blue) in which trichomes were counted. The green and blue boxes correspond to the regions where the Z and DG2 enhancers are expressed strongly. The primary, secondary, tertiary, and quaternary cell types are indicated with horizontal lines above the photograph. The arrow marks the spiracle that was used to set the lower boundary for the green box. The blue box was positioned directly above the green box. The red box identifies the stout tertiary trichomes, which were excluded from the counts. b, Number of trichomes in the lateral plus dorsal region (blue and green boxes) of the fifth abdominal segment of the larva. Open circles give trichome numbers for each individual (n=10); the black symbols and lines show the mean ±1SD. Embryos from each of the two genotypes (C108 and Df(X)svb108) were reared at three different temperatures: 17°C, 25°C, and 32°C. c, Cuticle images showing the quaternary trichomes in the lateral patch (below) and dorsal region (above) of Df(X)svb108 first-instar larvae that developed at the three different temperatures. The genotype by temperature interaction term of a two-way ANOVA was highly significant (F = 27.57, P<0.0001).

We noticed that a 41 kb region upstream of the three known svb enhancers displays high conservation among drosophilids, but contains only one small gene named SIP3 (Fig. 1b and S1). To test whether this region contained additional svb enhancers, we assayed reporter constructs encompassing the entire region (Fig. S1). Two constructs drove expression in the dorso-lateral epidermis in patterns that reproduced part of the native svb expression pattern (Fig. 1c, f, and S2). To characterize the precise expression domains driven by these newly-discovered enhancers, we performed co-immunodetection of the β-galactosidase reporter and of the Dusky-like protein, an early component of developing trichomes10.

The Z enhancer drove expression in many cells that produce quaternary trichomes (Fig. 1c). This expression overlaps the patterns driven by the three previously identified enhancers: 7, E, and A (Fig. 1b). The DG2 enhancer drove expression in a more restricted region (Fig. 1f) that overlaps the domain of expression driven by the E enhancer. Both Z and DG2 drive expression starting at stage 14 of embryogenesis (Fig. S2), which is similar to the time when svb mRNA can be detected in epidermal cells.

Given the redundant expression patterns of Z and DG2 with the three previously identified enhancers, we sought further evidence that Z and DG2 encode functional svb enhancers. We reasoned that if the Z and DG2 enhancers contribute to trichome patterning, then they should have evolved in a similar way to the previously discovered 7, E, and A enhancers; they should retain expression in species that also produce quaternary trichomes (such as D. simulans), and show reduced expression in D. sechellia, which has lost quaternary trichomes. We therefore assayed Z and DG2 enhancer constructs made with orthologous regions from D. simulans and D. sechellia. These regions were straightforward to identify because the genomes of these species are 3-5% divergent from D. melanogaster. The D. simulans Z and DG2 enhancers drove an expression pattern similar to that of the orthologous D. melanogaster enhancers (Fig.1c, d, f, and g), which suggests that Z and DG2 contribute to the production of quaternary trichomes both in D. melanogaster and in D. simulans. In contrast, the Z and DG2 enhancers from D. sechellia drove low levels of expression in only a few cells (Fig. 1e and h). The weak expression driven by the D. sechellia Z and DG2 constructs is consistent with the partial loss of expression driven by the D. sechellia A, E, and 7 enhancers and with the loss of quaternary trichomes in this species11.

To further assess the functional importance of the Z and DG2 enhancers, we generated a 32 kbp chromosomal deficiency on the X chromosome that removes both enhancers, called Df(X)svb108 (Fig. 1b). As a control, we used strain C108, which carries both of the parental transposable elements that were used to generate the deletion. Df(X)svb108 flies are viable and display no gross abnormalities. We examined first-instar larvae in detail and found that, when Df(X)svb108 embryos developed at the optimal temperature for development (25°C), larvae exhibited slightly fewer quaternary trichomes (Fig. 2b) and a reduction in the size of the lateral sensory bristles (Fig. S3). These results suggest that, under optimal conditions, Z and DG2 are functional enhancers of the svb gene that contribute to fine details of trichome patterning and perhaps to bristle morphogenesis. Despite this evidence that the Z and DG2 enhancers contribute to svb activity, their loss-of-function phenotype was considerably weaker than one would have expected, given the strong expression driven by these enhancers. We reasoned that this resulted from the fact that the Z and DG2 enhancers drive overlapping expression with the enhancers 7, E, and A, and that the latter three enhancers drive expression levels that are sufficient to generate most larval trichomes when embryos develop under optimal conditions11.

We therefore considered the hypothesis that Z and DG2 contribute to phenotypic robustness. Natural populations experience repeated stresses over evolutionary time, including variable temperatures. Temperature influences membrane fluidity, enzymatic activity, protein folding, protein-protein interactions, and protein-DNA interactions13,14. Organisms have evolved developmental mechanisms to buffer the phenotype in the face of temperature-induced cellular changes. We reasoned that sub-optimal temperatures might destabilize the transcriptional output of genes during embryogenesis and that secondary enhancers may confer a selective advantage by maintaining transcription above a required minimum threshold. We therefore tested the effect of Df(X)svb108 in embryos that had developed at 17°C and 32°C, temperatures close to the extremes at which Drosophila embryos survive15. We counted the number of quaternary trichomes in the regions where Z and DG2 are expressed strongly (Fig. 2a). The svb gene is an ideal target for this analysis, because quantitative changes in svb transcription influence trichome density, size and shape16.

Control embryos reared at all temperatures produced similar numbers of trichomes, implying that the number of trichomes is canalized against temperature variation17. The number of trichomes on Df(X)svb108 larvae reared at 25°C was similar to the number on control C108 larvae at all temperatures (Fig. 2b). In contrast, Df(X)svb108 larvae displayed a highly significant decrease in trichome numbers when reared at extreme temperatures (Fig. 2b). The primary and tertiary trichomes look normal on Df(X)svb108 larvae at all temperatures (data not shown), which is expected, because the Z and DG2 enhancers do not drive expression in cells producing primary and tertiary trichomes.

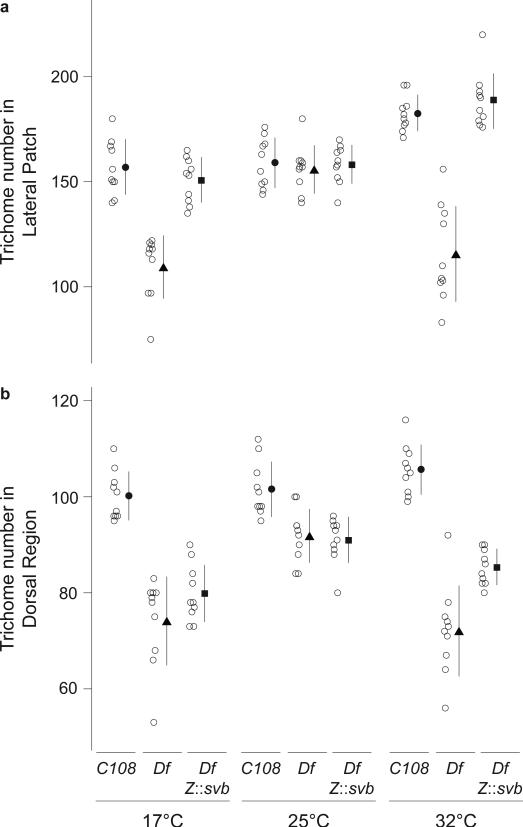

In principle, the loss of trichomes observed on Df(X)svb108 larvae reared at extreme temperatures may have resulted from mechanisms acting independently of the Z and DG2 enhancers. If the effects observed with Df(X)svb108 resulted from loss of the Z and DG2 enhancers, then reintroducing a functional Z or DG2 enhancer into a Df(X)svb108 background should rescue some trichomes. We tested this hypothesis for the Z enhancer. We generated a transgene carrying the svb cDNA under the transcriptional control of the Z enhancer and introduced it onto the third chromosome of Df(X)svb108 flies. At extreme temperatures, the Z::svb cDNA transgene completely rescued wild type trichome numbers in the lateral patch (Fig. 3a and S3). However, in the region dorsal to the lateral patch, the rescue is very weak or absent (Fig. 3b and S3). This is consistent with the fact that Z drives expression at high levels in the lateral region, where rescue is observed, and only weakly in a small number of cells of the dorsal region (Fig. 1). The loss of canalization in the dorsal region of Df(X)svb108 larvae may be caused by loss of DG2, which drives expression mainly in this dorsal region. These results demonstrate that Z contributes to phenotypic robustness. Moreover, the rescue of trichome numbers by a transgene introduced onto a different chromosome from the svb locus suggests that Z does not need to be in intimate contact with other svb enhancers or with the svb basal promoter to buffer svb function. Instead, we hypothesize that Z contributes to phenotypic robustness simply by boosting levels of svb transcription in the cells in which Z drives expression.

Figure 3. Rescue of the temperature-dependent trichome loss in the lateral patch by a Z::svb transgene.

a,b, Trichome number in the lateral patch (a) and dorsal region (b) of the 5th abdominal segment of larvae with the genotypes C108, Df(X)svb108, and Df(X)svb108; Z::svb. Open circles represent trichome numbers for each individual (n=10); the black symbols and lines show the mean ±1SD.

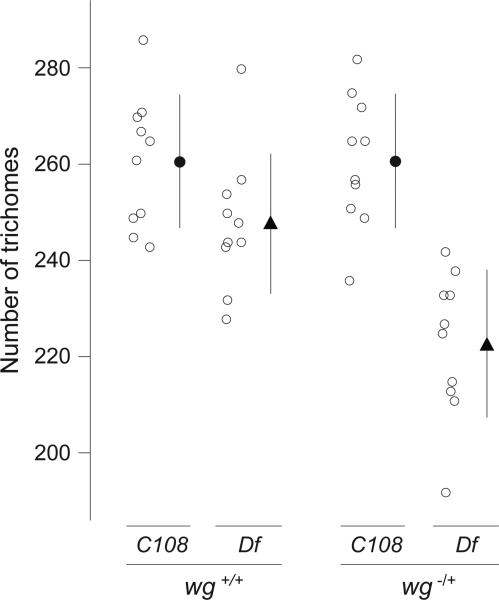

Given this evidence that the Z enhancer, and possibly also DG2, contribute to robustness against environmental perturbations, we asked whether these enhancers also buffer against genetic perturbations. For example, Boettiger & Levine18 have reported that two Dorsal target genes that possess “shadow” enhancers maintain synchronous transcriptional activation across Dorsal+/- embryos, whereas two Dorsal target genes that seem to lack such “shadow” enhancers display less synchrony in Dorsal+/- embryos. Therefore, we tested the effect of reducing Wingless signaling, which is required for normal development of quaternary trichomes7, by crossing the Df(X)svb108 allele and the C108 control allele into a background heterozygous for a wingless null allele. At 25°C, the Df(X)svb108;wg-/+ embryos produced significantly fewer trichomes than C108;wg-/+ embryos, Df(X)svb108 embryos, and C108 embryos (Fig. 4). The combined results suggest that the Z and DG2 enhancers buffer against both environmental and genetic perturbations.

Figure 4. Effect of Df(X)svb108; wg-/+ on the number of quaternary trichomes.

C108 and Df(X)svb108 embryos that were heterozygous for a null allele of wingless were reared at 25°C. Quaternary trichomes were counted as described in the legend to Fig. 2. A two-way ANOVA reveals a highly significant genotype by temperature interaction (F=7.79, p=0.0084), which is caused by a large reduction in the number of trichomes on Df(X)svb108; wg-/+ larvae relative to all other genotypes.

These results indicate that the production of larval trichomes is normally canalized and that this is accomplished, at least in part, through transcriptional activation mediated by the svb secondary enhancers that are removed in Df(X)svb108.

The svb locus contains multiple enhancers with overlapping expression patterns. Similar patterns of overlapping enhancer activity have been found for the cis-regulatory regions of the Drosophila genes sog1, vnd3, and brinker1 and for the cis-regulatory regions of the mouse genes sonic hedgehog4 and sox102. Moreover, it has been estimated that 50% of the target genes of the transcription factor Dorsal contain shadow enhancers5. Therefore, the presence of additional enhancers in cis-regulatory regions may be a common signature of developmental regulators. This may explain why, in previous reports, animals carrying deletions of highly conserved enhancers have not displayed observable phenotypic defects when reared in standard laboratory conditions19,20.

Developmental buffering is likely to result from many molecular mechanisms. For example, deletion of the conserved miRNA miR7 in D. melanogaster has no obvious phenotypic effect in normal laboratory conditions, but it is required to canalize the expression of the gene atonal under fluctuating temperatures21. Similarly, our results indicate that svb secondary enhancers have a minimal role at optimal conditions for development, but that they are essential to buffer the trichome phenotype under genetic or environmental variability. Secondary enhancers are likely to be evolutionarily maintained by selection for robustness against temperature fluctuation, genetic background effects22, and expression noise23.

Methods summary

The target regions were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA from D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. sechellia. These PCR fragments were cloned into pCaSpeR-hs43-lacZ or placZattB and integrated into the D.melanogaster genome to test their enhancer activity. The precise expression domains of the enhancer constructs were determined by double staining with a mouse anti-βGal antibody (Promega) and a rabbit anti-Dusky-like antibody10 and then by examining stained embryos with a confocal microscope. Df(X)svb108 was generated via flipase-induced deletion of the DNA between two FRTs present in C108. We made 0-3 hour embryo collections and reared embryos to hatching at different temperatures. First-instar larvae were mounted in 1:1 Hoyer's:lactic acid mixture and cuticles were imaged with phase-contrast microscopy. Trichomes were counted using ImageJ. A null allele of wingless (wgIG22)24 was used to obtain males with the genotypes Df(X)svb108 /Y, +/wgIG22 and C108/Y, +/wgIG22.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank D. Chien and D. Erezyilmaz for assistance with early experiments, L. Kruglyak, S. Levin, and S. Tavazoie for helpful comments on the manuscript, and E. Wieschaus for providing the wg mutant flies. This work was supported by The Pew Charitable Trusts Latin American Fellows Program in the Biomedical Sciences Fellowship to N. F., Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Blanc 2008, Netoshape) to F. P., and NIH (GM063622-06A1) and NSF (IOS-0640339) grants to D.L.S.

Methods

Reporter constructs

Genomic DNA from D. melanogaster, D. simulans, and D. sechellia (see table below) was amplified using the Expand HiFi PCR system (Roche) and cloned into pGEMT Easy (Promega). Fragments Z from D. melanogaster and Zprox from D. simulans were subcloned into pCaSpeR-hs43-lacZ using NotI. This plasmid was co-injected with pTURBO33 into D. melanogaster w1118 embryos using standard conditions. At least three independent transgenic lines were established for each construct. The remaining fragments were subcloned into placZattB using NotI and injected into line M{3xP3-RFP.attP} ZH-51D (with M{vas-int.Dm}ZH-2A)25.

| Region name | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| D.melanogaster DGO | TGGCCTGTGCCATGTGTGCGAGTACG | TGGGTGCGCAATTATGCCGCCAGAGC |

| D.melanogaster DG1 | CTGGGTGTGTGTGCAATATGTGAGC | GTGAGGGTACAAGGCGAAATCGAAA |

| D.melanogaster DG2 | AATTGTTCGCACGCTTCGCTCTAA | GATTGGTGCCGAGAGGTGAAAGTG |

| D.melanogaster DG3 | GGCCACAACTCAATGGCAAAAATG | CAGCAGCGAATCAAGACGAAAGGT |

| D.melanogaster DG4 | CCCCCGTCTTTGTCTGTTTGTCTG | GGAACACAATCTGCCTGCCTGACT |

| D.melanogaster DG5 | TATCCTTTTACGACGCCCCTGTGTC | GATTCGGTTCCTTGGGATTGGATTT |

| D.melanogaster Z | ATTGCTTCGGCTCTCCCGTTA | TTGTGTGGCTCACTTGGCAC |

| D.simulans Zprox | GTGAAAGATCGGATCCGTCT | GTTCGTATCGCCCACTTGAAT |

| D.simulans Z | ATTGCTTCGGCTCTCCCGTTA | TTATGTGGCTCACTTGGCAC |

| D.sechellia Z | ATTGCTTCGGCTCTCCCGTTA | TTGTGTGGCTCACTTGGCAC |

| D.simulans DG2 | TGCTTTTCCAACCCCTCAGTT | GGGGGTGCAGGCTATTTTGTTC |

| D.sechellia DG2 | TGCTTTTCCAACCCCTCAGTT | GAGGGTGCAGGCTATTTTGTTC |

Only transgenes containing the Z and DG2 regions drove expression in the dorso-lateral epidermis. DG3, which is contained within the region deleted by Df(X)svb108, drove weak expression in the ventral epidermis, but no phenotypic changes in the ventral denticles were observed at any temperature. Zprox was analyzed from D. simulans DNA, as this region lacked a large roo element that is present in the D.melanogaster genome.

Immunohistochemistry and Immunofluorescence

Embryos were fixed using standard conditions. To determine the precise expression domains of the enhancer constructs we performed fluorescent double staining with a mouse anti-βGal antibody (Promega) and a rabbit anti-Dusky-like antibody10. Alexa-488 anti-rabbit and Alexa-647 anti-mouse (Molecular Probes) were used as secondary antibodies. The embryos were examined on a Leica TCS SPE confocal microscope. For immuno-histochemistry, we used a rabbit anti-βGal antibody (Cappel) and anti-rabbit antibody coupled to HRP (Santa Cruz Biotech) and staining was developed with DAB/Nickel.

Generation of Df(X)svb108

pBac{WH}Ptp4E[f02952] and pBac{RB}e03292 were recombined onto the same X chromosome and a homozygous stock was generated (named C108). This stock was crossed to a line containing a hs::flipase and larvae were heat shocked at 37C for 1 hour each day during larval development. After crossing these adults to white- flies, we selected adults that had lost one copy of the white+ transgene (originating on one of the pBac transgenes), which is expected if the two FRT sites recombined to generate a deletion. The deletion was confirmed by a PCR experiment, which amplified a fragment containing a chimeric piggyBac element. The primer used (TGCATTTGCCTTTCGCCTTAT) amplified the expected 7.3 kb fragment26. We then generated a stock homozygous for the deletion. This allele is named Df(X)svb108.

Embryo collection and cuticle microscopy

We made 0-3 hour embryo collections (many hours before the onset of svb expression in epidermal tissues) and transferred embryos to dishes with water at the different temperatures. Two days later, we collected first instar larvae and incubated them at 60C for 4 hours. Subsequently, larvae were mounted on a microscope slide with a drop of 1:1 Hoyer's:lactic acid mixture. After overnight drying, the cuticles were imaged with phase-contrast microscopy.

Trichome counting

A spiracle below the lateral patch was used as a landmark to position the green box (shown in Fig.2a). The blue box was positioned directly above the green box (shown in Fig.2a). Both boxes were programmed as macros in Image J software (Rasband, W.S., ImageJ, U. S. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/, 1997-2009). The trichomes were counted using the cell-counter option of Image J.

Rescue experiments

The cDNA of svb was amplified from the plasmid pUAS-svb6 with primers NsiI-svbcDNAfw (ATGCATTTAACTCACCTGGGCGAATCC) and NdeI-svbcDNArv (CATATGTTGCAGCTTGTTCGGTTGGTA) and cloned into pCR-Blunt II-TOPO (Invitrogen). The svb cDNA was subcloned with NsiI and NdeI into a version of placZattB25 that had the lacZ removed (by cutting with PstI and NdeI). We named this plasmid pRSQsvb. The Z enhancer was amplified with the primers used previously (see reporter constructs) that had the addition of 3’ XbaI sites. This PCR fragment was cloned into pGEMT (Promega) and subcloned into pRSQsvb using XbaI. This plasmid was injected into the recipient line M{3xP3-RFP.attP}ZH- 86Fb (with M{vas-int.Dm}ZH-2A)25. A third chromosome carrying the Z::svb transgene was introduced into the Df(X)svb108 line to obtain a stock homozygous for both the deficiency, on the X chromosome, and Z::svb, on the third chromosome, and is referred to as Df(X)svb108; Z::svb.

Wingless experiment

A null allele of wingless (wgIG22)24 was used to obtain males of the genotype FM7c, actin::GFP/Y; CyO, actin::GFP/wgIG22. These males were crossed to females with either Df(X)svb108/Df(X)svb108 or C108/C108 genotypes. We selected for non-fluorescent progeny, which were male first-instar larvae heterozygous for the wingless null allele: Df(X)svb108/Y; wgIG22/+ or C108/Y; wgIG22/+.

References

- 1.Hong JW, Hendrix DA, Levine MS. Shadow enhancers as a source of evolutionary novelty. Science. 2008;321:1314. doi: 10.1126/science.1160631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Werner T, Hammer A, Wahlbuhl M, Bosl MR, Wegner M. Multiple conserved regulatory elements with overlapping functions determine Sox10 expression in mouse embryogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6526–6538. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeitlinger J, et al. Whole-genome ChIP-chip analysis of Dorsal, Twist, and Snail suggests integration of diverse patterning processes in the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 2007;21:385–390. doi: 10.1101/gad.1509607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeong Y, El-Jaick K, Roessler E, Muenke M, Epstein DJ. A functional screen for sonic hedgehog regulatory elements across a 1 Mb interval identifies long-range ventral forebrain enhancers. Development. 2006;133:761–772. doi: 10.1242/dev.02239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry MW, Cande JD, Boettiger AN, Levine M. Evolution of Insect Dorsoventral Patterning Mechanisms. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1101/sqb.2009.74.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Payre F, Vincent A, Carreno S. ovo/svb integrates Wingless and DER pathways to control epidermis differentiation. Nature. 1999;400:271–275. doi: 10.1038/22330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bokor P, DiNardo S. The roles of hedgehog, wingless and lines in patterning the dorsal epidermis in Drosophila. Development. 1996;122:1083–1092. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.4.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Overton PM, Chia W, Buescher M. The Drosophila HMG-domain proteins SoxNeuro and Dichaete direct trichome formation via the activation of shavenbaby and the restriction of Wingless pathway activity. Development. 2007;134:2807–2813. doi: 10.1242/dev.02878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chanut-Delalande H, Fernandes I, Roch F, Payre F, Plaza S. Shavenbaby couples patterning to epidermal cell shape control. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e290. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fernandes I, et al. A scaffold of ZP proteins remodels the apical compartment for localized cell shape changes. Developmental Cell. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGregor AP, et al. Morphological evolution through multiple cis-regulatory mutations at a single gene. Nature. 2007;448:587–590. doi: 10.1038/nature05988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sucena E, Delon I, Jones I, Payre F, Stern DL. Regulatory evolution of shavenbaby/ovo underlies multiple cases of morphological parallelism. Nature. 2003;424:935–938. doi: 10.1038/nature01768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crane-Robinson C, Dragan AI, Read CM. Defining the thermodynamics of protein/DNA complexes and their components using micro-calorimetry. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;543:625–651. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-015-1_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hochachka PW, Somero GN. Biochemical adaptation : mechanism and process in physiological evolution. Oxford University Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powsner L. The effects of temperature on the durations of the developmental stages of Drosophila melanogaster. Physiological Zoology. 1935;8:474–520. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delon I, Chanut-Delalande H, Payre F. The Ovo/Shavenbaby transcription factor specifies actin remodelling during epidermal differentiation in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 2003;120:747–758. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(03)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nijhout HF, Davidowitz G. In: Developmental Instability (DI): Causes and Consequences. Polak M, editor. Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boettiger AN, Levine M. Synchronous and stochastic patterns of gene activation in the Drosophila embryo. Science. 2009;325:471–473. doi: 10.1126/science.1173976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cretekos CJ, et al. Regulatory divergence modifies limb length between mammals. Genes Dev. 2008;22:141–151. doi: 10.1101/gad.1620408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong N, Kang C, Raulet DH. Redundant and unique roles of two enhancer elements in the TCRgamma locus in gene regulation and gammadelta T cell development. Immunity. 2002;16:453–463. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00285-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, Cassidy JJ, Reinke CA, Fischboeck S, Carthew RW. A microRNA imparts robustness against environmental fluctuation during development. Cell. 2009;137:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crickmore MA, Ranade V, Mann RS. Regulation of Ubx expression by epigenetic enhancer silencing in response to Ubx levels and genetic variation. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000633. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raser JM, O'Shea EK. Noise in gene expression: origins, consequences, and control. Science (New York, N.Y. 2005;309:2010–2013. doi: 10.1126/science.1105891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Heuvel M, Harryman-Samos C, Klingensmith J, Perrimon N, Nusse R. Mutations in the segment polarity genes wingless and porcupine impair secretion of the wingless protein. EMBO J. 1993;12:5293–5302. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06225.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bischof J, Maeda RK, Hediger M, Karch F, Basler K. An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ-line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:3312–3317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611511104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parks AL, et al. Systematic generation of high-resolution deletion coverage of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36:288–292. doi: 10.1038/ng1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.