Abstract

CD44 is a highly glycosylated cell adhesion molecule that is involved in lymphocyte infiltration of inflamed tissues. We have demonstrated previously that sialic acid residues of CD44 negatively regulates its receptor function and CD44 plays an important role in the accumulation of T helper type 2 (Th2) cells in the airway of a murine model of acute asthma. Here we evaluated the role of sialidase in the hyaluronic acid (HA) receptor function of CD44 expressed on CD4+ T cells, as well as in the development of a mite antigen-induced murine model of acute asthma. Splenic CD4+ T cell binding of HA was examined with flow cytometry. Expression of sialidases (Neu1, Neu2, Neu3 and Neu4) in spleen cells was evaluated by quantitative real-time reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction. Airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) were evaluated in the asthmatic Neu1-deficient mouse strain SM/J model. Splenic CD4+ T cells from asthmatic model mice displayed increased HA receptor activity of CD44 after culture with the antigen, along with characteristic parallel induction of sialidase (Neu1) expression. This induction of HA binding was suppressed significantly by a sialidase inhibitor and was not observed in SM/J mice. Th2 cytokine concentration and absolute number of Th2 cells in the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and AHR were decreased in SM/J mice. In conclusion, HA receptor activity of CD44 and acute asthmatic reactions, including Th2-mediated airway inflammation and AHR, are dependent upon Neu1 enzymatic activity. Our observation suggests that Neu1 may be a target molecule for the treatment of asthma.

Keywords: asthma, CD44, Neu1 sialidase, SM/J mice, Th2 cells

Introduction

CD44 is a widely expressed cell adhesion molecule thought to be involved in several physiological and pathological processes, such as haemopoiesis, homing to mucosal lymphatic tissue and lymphocyte infiltration of inflamed tissues [1,2]. The principal ligand for CD44 is hyaluronic acid (HA) [3]. Although most blood cells express CD44, few of the cells use the molecule for HA recognition [1]. We have reported previously that an inducible sialidase might influence the glycosylation and receptor activity of CD44 on human monocytes [4].

Accumulation of antigen-activated CD4+ T cells in the airway is believed to contribute to the development of asthma [5]. CD44–HA interactions can promote extravasation and egress of antigen-activated lymphocytes in inflamed vascular beds [6]. Recently, we reported that anti-CD44 monoclonal antibody (mAb) treatment inhibits the development of antigen-induced airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in Ascaris suum antigen-induced murine model of pulmonary eosinophilia [7]. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CD44 plays an important role in the accumulation of T helper type 2 (Th2) cells in the airway of mice with Dermatophagoides farinae (Derf)-induced allergic asthma [8].

Sialic acids exist at the terminal positions of glycoproteins, glycolipids and gangliosides, and are involved in a variety of physiological processes, including immune responses [9,10]. Sialidases are a family of exoglycosidases that hydrolyze the terminal sialic acid linkage in these biomolecules. Therefore, the removal of sialic acids catalysed by a sialidase greatly influences many biological processes, such as cell differentiation, cell growth and apoptosis, through changing the conformation of glycoproteins and masking the biological sites of functional molecules [10]. Four types of mammalian sialidases have been identified and characterized, designated Neu1, Neu2, Neu3 and Neu4, which differ in their subcellular localization and enzymatic properties [10,11]. In addition to glycoconjugate catabolism, Neu1 and Neu3 are involved in cellular signalling, including immune responses [12,13]. Neu1 is also present on the surface of activated T cells [14], where it may influence Th2 cytokine production [15,16].

In the present study, we evaluated the role of sialidase in the HA binding ability of CD44 expressed on CD4+ T cells using a murine model of asthma. Spleen cells from BALB/c mice with Derf-induced asthma were stimulated with antigen in vitro, and CD44 receptor activity and sialidase expression were evaluated. Furthermore, induction of the HA binding ability of CD44 and sialidase activity was examined in spleen cells from the SM/J mouse model of asthma. Finally, we analysed Th2-mediated airway inflammation and AHR using SM/J mice.

Materials and methods

Animal model

BALB/c and DBA/1J mice (female, 8–12 weeks old) were obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Yokohama, Japan). SM/J mice (female, 8–12 weeks old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Mice were sensitized by intraperitoneal injections of 500 µg Derf allergen (Greer Laboratories Inc., Lenoir, NC, USA) with 2 mg alum on day 0 and day 14. The mice were then challenged by intranasal administration of 800 µg of Derf solution on day 29. Negative control animals were injected with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) plus alum and exposed to PBS in a similar manner. All experiments in this study were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of Kagawa University.

Bronchoalveolar lavage and AHR

Broncoalveolar lavage was performed 24 h after the antigen challenge, and differential cell counts were performed. Airway resistance (sRaw) was measured as described previously [8]. AHR is expressed as the concentration of methacholine (Mch) required to provoke a doubling of sRaw (PC200).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Amounts of interferon (IFN)-γ, interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13 and eotaxin (CCL11) (R&D Systems Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were measured using a commercial ELISA kit. The detection limits were 2·0, 2·0, 2·0, 1·5 and 3·0 pg/ml for IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-5, IL-13 and eotaxin, respectively. Concentrations below the detection limits were assumed to be zero for the purpose of statistical analysis.

Flow cytometry

Splenocytes were removed from an asthmatic model mouse and depleted of red blood cells. Cells were stimulated with Derf (10 µg/ml) in the presence or absence of a sialidase inhibitor, NeuAc2en (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), and tested for HA binding by flow cytometry after staining with fluorescein-conjugated HA (FL-HA) [4] in the presence or absence of anti-CD44 mAb, IRAWB14, which enhances the HA-binding ability of cells [17], and allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-CD4 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). As a specificity control, cells were also incubated with the CD44 blocking antibody KM81 (Cedarlane, Ontario, Canada), followed by staining with FL-HA. To test the peanut-agglutinin (PNA) binding, the cells were stained with FL-PNA (Seikagaku, Tokyo, Japan). Lymph nodes were obtained from the paratracheal, perihilar and peribronchial regions of an asthmatic mouse model (BALB/c). In some experiments, cells were treated with bacterial sialidase as described previously [4]. Cell surface expression of CD44 and HA binding were examined by direct immunofluorescence using a flow cytometer. Flow cytometric analysis was performed by gating the lymphocyte population on the basis of their relative size (forward light scatter) and granularity (side angle scatter) in splenocytes. BALF cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-anti-T1/ST2 (MD Biosciences, Zurich, Switzerland) as a Th2 cell surface marker [18], phycoerythrin (PE)-anti-Tim-3 (eBiosciences, San Diego, CA) as a Th1 cell surface marker [19], APC-anti-CD4 and peridinin–chlorophyll–protein complex (PerCP) anti-CD3 (BD Biosciences). T cell clones (BF3 and BF4) [20] were stimulated with immobilized anti-CD3 mAb in the presence of anti-CD28 mAb and IL-2. Activated T cell clones were tested for HA and PNA binding by flow cytometry.

Endogenous sialidase assay

Endogenous sialidase activity of Derf antigen-stimulated cells and T cell clones activated via T cell receptors were determined under the optimal conditions as described previously [4,21,22]. 4-Methylumbelliferyl-a-N-acetyl-D-neuraminic acid (4MU NeuAc; Nakarai, Japan) and bovine mixed gangliosides (Type II; Sigma) were used as substrates at the optimal pH of 4·6, as they are considered to be appropriate substrates for lysosomal-type sialidases (Neu1) and for membrane associated sialidases (Neu3), respectively [23–25]. For assays with 4-MU-NeuAc, the amount of 4-MU released was determined fluorometrically [21]; for assays with gangliosides, the sialic acids released were measured by reversed-phase liquid chromatography [22]. Protein concentration was determined by a dye-binding assay (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA). One unit of sialidase was defined as the amount of enzyme that catalysed the release of 1 nmol of sialic acid per hour.

Reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR)

Quantitative analysis of endogenous mouse sialidase mRNA levels for Neu1, Neu2, Neu3 and Neu4 were performed by real-time PCR using a Light Cycler rapid thermal cycler system (Roche) with respective primers, as described previously [26]. To normalize for sample variation, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal control. To compare the sialidase levels with one another, standard curves for sialidase cDNA were generated by serial dilution of the Bluescript vector containing the respective genes covering the entire coding sequence.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). The Kruskal–Wallis test was used to compare values of different groups. In cases with a significant difference between groups, intergroup comparisons were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U-test. Differences with probability values of less than 0·05 were considered significant.

Results

HA binding ability of CD4+ T cells in a murine model of asthma

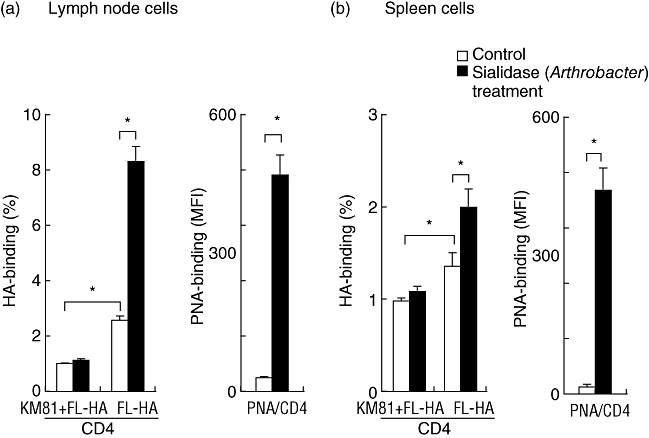

We developed an acute asthmatic model induced by the Derf antigen, as reported previously [8]. The ability of lymph nodes and spleen CD4+ T cells of this asthmatic model to bind HA was examined by flow cytometry. A small but significant number of these CD4+ T cells was able to bind HA in a CD44-dependent manner (P < 0·05, Fig. 1). This binding was increased by treatment with bacterial sialidase in vitro. Sialidase activity was monitored by PNA staining of enzyme-treated cells. Sialidase treatment significantly induced PNA binding of CD4+ T cells obtained from lymph nodes and spleen (P < 0·05, Fig. 1). Sialic acid negatively regulated CD44-dependent HA binding of these cells.

Fig. 1.

HA binding ability of CD44 expressed on CD4 T cells of lymph nodes and spleen of a murine model of asthma. Lymph node and spleen cells from a BALB/c mouse model of Dermatophagoides farinae (Derf)-induced asthma were treated with sialidase, and stained with fluorescein-conjugated hyaluronic acid (FL-HA) or FL peanut-agglutinin (FL-PNA) and allophycocyanin (APC)-anti-CD4. CD44-dependent HA-binding was evaluated by flow cytometry gating on CD4+ cells. Data represent means ± standard error of the mean. The values shown are means from three independent experiments with six mice. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0·05) between the indicated groups. KM81 is an anti-CD44 blocking antibody.

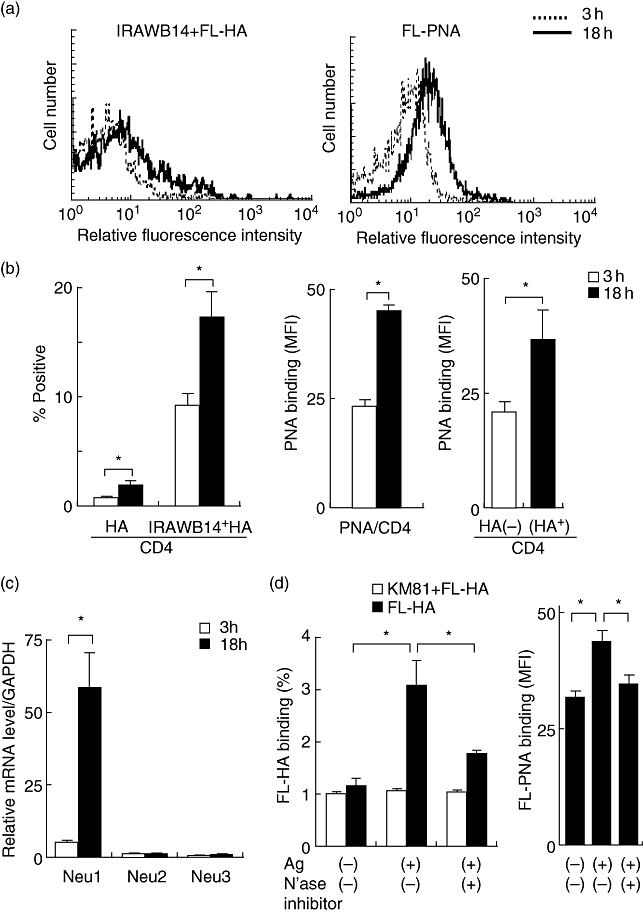

The in vitro ability of antigen-activated splenic CD4+ T cells to bind HA was examined by flow cytometry. These CD4+ T cells had increased CD44 receptor activity after culture with the antigen in the presence or absence of the anti-CD44 mAb IRAWB14, which enhances HA binding to CD44 [17]. PNA binding was increased significantly by the antigen stimulation, and was significantly higher in HA-binding CD4+ T cells than in HA non-binding CD4+ T cells (P < 0·05, Fig. 2a,b).

Fig. 2.

Role of sialidase in the induction of CD44 receptor activity on CD4+ spleen cells. Spleen cells from Dermatophagoides farinae (Derf)-sensitized and Derf-challenged BALB/c mice were cultured with Derf (10 µg/ml) and harvested 3 h or 18 h after reactivation in vitro. (a) Cells were incubated with fluorescein-conjugated hyaluronic acid (FL-HA) in the presence of IRAWB14 or FL-peanut-agglutinin (PNA), followed by staining with CD4-allophycocyanin (APC). HA and PNA binding of Derf antigen-activated CD4+ spleen cells were evaluated by flow cytometry. These results were typical of those obtained in three independent experiments. (b) Harvested cells were stained with FL-HA in the presence or absence of IRAWB14, or FL-PNA and CD4-APC. To analyse the PNA binding on cells that did or did not have the ability to recognize HA, cells were stained with FL-HA, biotinylated PNA plus streptavidin–phycoerythrin, and CD4-APC. HA and PNA binding was estimated by fluorescence intensity gating on CD4+ cells. (c) Expression of sialidases (Neu1, Neu2 and Neu3) was examined by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) in spleen cells 3 h or 18 h after reactivation in vitro. (d) The presence of sialidase (N'ase) inhibitor abrogates the induction of HA and PNA binding of CD4+ spleen cells. Spleen cells were cultured with Derf in the presence or absence of sialidase inhibitor, NeuAc2en (4 mM), and HA and PNA binding was estimated by flow cytometry. Data represent means ± standard error of the mean. The values shown are averaged from three independent experiments with nine mice. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0·05) between the indicated groups.

We have reported previously that an inducible sialidase might influence the glycosylation and receptor activity of CD44 expressed on human monocytes [4]. Subsequently, we investigated whether sialidases are induced in mouse spleen cells by antigen stimulation. The levels of sialidase mRNAs (Neu1, Neu2, Neu3 and Neu4) in the spleen of this model were evaluated by quantitative RT–PCR. Endogenous levels were compared with one another as they were measured quantitatively using standard curves of respective cDNAs. Neu1 was the most highly expressed, whereas Neu4 was hardly detected (data not shown). Derf-antigen induced the expression of Neu1, but not Neu2 and Neu3, in spleen cells along with characteristic parallel induction of the HA binding ability of CD44 (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, the increase in HA and PNA binding by activated CD4+ spleen cells was suppressed significantly by the sialidase inhibitor NeuAc2en (Fig. 2d).

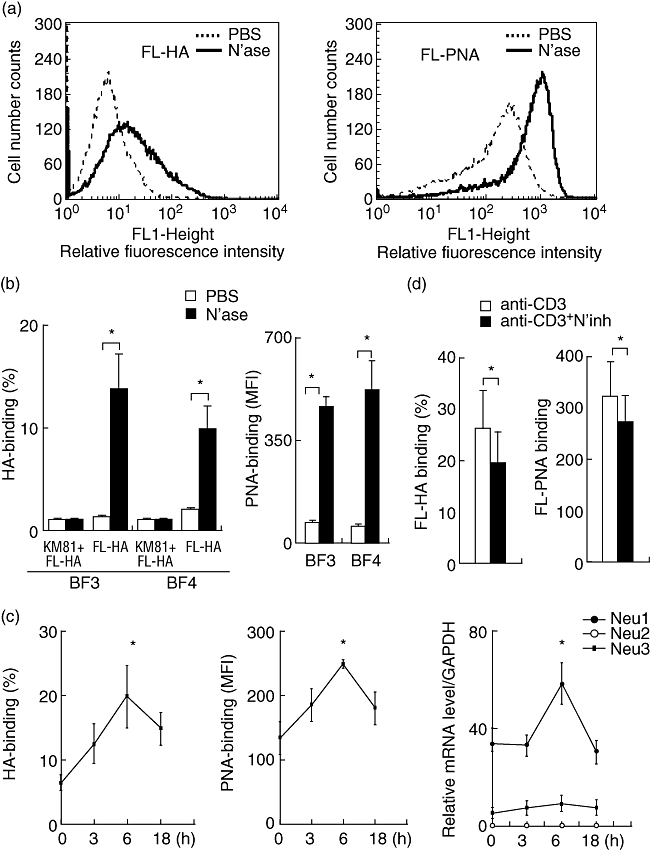

Induction of CD44 receptor activity and sialidase in CD4+ T cell clones

Subsequently, we investigated whether sialidases are induced in mouse T cells by stimulation via T cell receptors. First, CD4+ T cell clones (BF3, BF4) were treated with bacterial sialidase. HA and PNA binding of these cells was increased significantly (Fig. 3a,b). T cell clones transiently displayed increased CD44 receptor activity, along with characteristic paralleled induction of Neu1, but not Neu2 and Neu3, mRNAs (Fig. 3c). Although Neu3 was increased slightly at 6 h, the change in the mRNA level was negligible. The induction of HA-binding ability via T cell receptors was suppressed significantly by the sialidase inhibitor NeuAc2en (Fig. 3d). These observations suggest that endogenous sialidase (Neu1) has an important role in the activation of CD44 receptor activity on CD4+ T cells.

Fig. 3.

Role of sialidase in the induction of CD44 receptor activity on CD4+ T cell clones. (a) T cell clone (BF3) was treated with sialidase (N'ase) (bold line) or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (dotted line). Hyaluronic acid (HA) and peanut agglutinin (PNA) binding ability of T cell clone were estimated by flow cytometry. These results are typical of those obtained in three independent experiments. (b) T cell clones (BF3 and BF4) were treated with sialidase and CD44-dependent HA binding ability of T cell clones was estimated by flow cytometry. Harvested cells were stained with fluorescein-conjugated HA (FL-HA) in the presence or absence of KM81. To analyse the PNA binding, cells were stained with FL-PNA. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0·05) between the indicated groups. (c) T cell clone (BF3) was cultured with immobilized anti-CD3 in the presence of anti-CD28 and interleukin (IL)-2, and harvested 3 h, 6 h or 18 h after activation. Harvested cells were stained with FL-HA or FL-PNA. HA and PNA binding were estimated by flow cytometry. Expression of sialidase (Neu1, Neu2 and Neu3) in T cell clone was examined by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) 3 h, 6 h or 18 h after stimulation via T cell receptors. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0·05). (d) The presence of a sialidase inhibitor (N'inh) abrogates induction of HA and PNA binding of T cell clones. T cell clone (BF3) was cultured with anti-CD3 mononuclear cells (mAb) in the presence or absence of NeuAc2en (4 mM), and HA and PNA binding were estimated by flow cytometry. Data represent means ± standard error of the mean. The values shown are means from three independent experiments. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0·05) between the indicated groups.

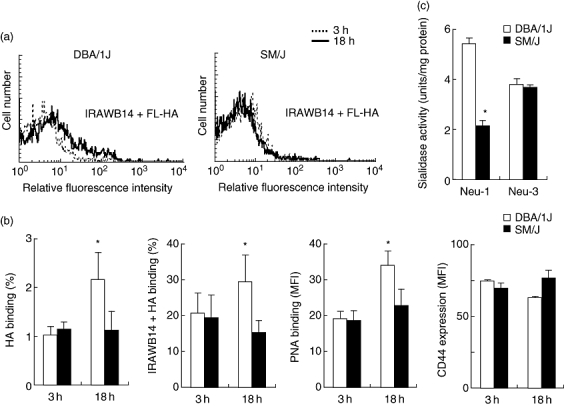

Activation of splenic CD4+ T cells from SM/J mice does not increase the HA-binding ability of CD44

We developed a Derf-induced murine model of asthma in the Neu1-deficient mouse strain SM/J to compare with the mouse strain DBA/1J, whose genetic background is closest to that of SM/J [27]. HA and PNA binding of CD4+ spleen cells was induced by antigen stimulation in DBA/1J mice, but not in SM/J mice (Fig. 4a,b). The CD44 expression level did not change during stimulation with the antigen in DBA/1J or SM/J mice (Fig. 4b). Neu1 sialidase activity in antigen-activated splenocytes in SM/J mice was significantly lower than that in BDA/1J mice, although Neu3 sialidase activity was similar between these two strains (Fig. 4c). These findings indicated that Neu1 activity was critical for activation of CD44 receptor activity on splenic CD4+ T cells stimulated by Derf antigen.

Fig. 4.

The receptor activity of CD44 fails to be induced effectively in CD4+ splenic T cells from an SM/J mouse model of asthma. Spleen cells from DBA/1J and SM/J Dermatophagoides farinae (Derf)-sensitized and Derf-challenged mice were cultured with Derf (10 µg/ml) and harvested 3 h or 18 h after reactivation in vitro. (a) Harvested cells were stained with fluorescein-conjugated hyaluronic acid (FL-HA) in the presence of IRAWB14, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP) anti-CD3 and allophycocyanin (APC) anti-CD4. HA binding was analysed by flow cytometry gating on CD3+ and CD4+ T cells. These results are typical of those obtained in three independent experiments. (b) CD44-dependent HA binding ability of CD4+ spleen cells was estimated by flow cytometry. Harvested cells were stained with FL-HA in the presence or absence of IRAWB14, PerCP anti-CD3 and APC anti-CD4. To analyse the peanut-agglutinin (PNA) binding, cells were stained with FL-PNA, PerCP anti-CD3 and APC anti-CD4. HA and PNA binding were estimated by flow cytometry gating on CD3+ and CD4+ T cells. (c) Sialidase activity (Neu1 and Neu3) of spleen cells activated by antigen for 18 h was estimated as described in Materials and methods. Data represent means ± standard error of the mean. The values shown are means from six independent experiments with 12 mice per group. Asterisks indicate significant differences (P < 0·05) between the two mouse strains.

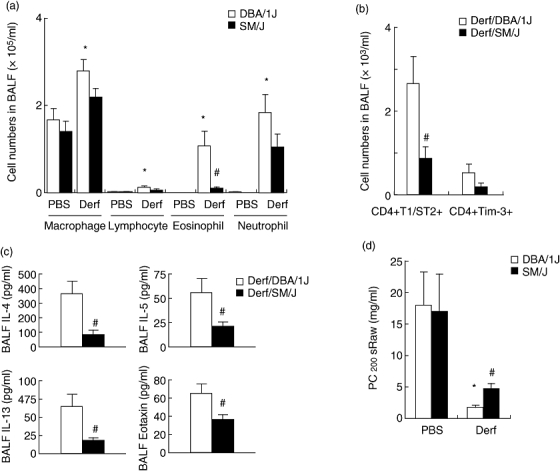

Suppression of acute asthmatic reaction in the Neu1-deficient SM/J mouse strain

We evaluated Derf induced airway inflammation and AHR in SM/J mice compared with DBA/1J mice. The two groups of mice were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection with either Derf in PBS or PBS alone. The number of inflammatory cells in the BALF was evaluated 24 h after the transnasal antigen challenge. After Derf exposure, numbers of macrophages, lymphocytes, eosinophils and neutrophils were increased significantly in the BALF compared with PBS-exposed DBA/1J mice (Fig. 5a; DBA/1J:Derf versus PBS). There were significantly fewer eosinophils in the BALF of Derf-challenged SM/J mice compared with BALF of Derf-challenged DBA/1J mice. Th2 cells play a critical role in this asthmatic mouse model [8]. Expression of T1/ST2 and Tim-3 on CD4+ T cells in the BALF was evaluated by flow cytometry 24 h after Derf challenge. T1/ST2 and Tim-3 are makers of Th2 [18] and Th1 [19] cells, respectively. The numbers of Th2 cells (P = 0·0154), but not Th1 cells (P = 0·2473), in the BALF was significantly lower in Derf-challenged SM/J mice than in Derf-challenged DBA/1J mice (Fig. 5b). Furthermore, concentrations of Th1 (IFN-γ) and Th2 (IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13) cytokines as well as eotaxin (CCL11), a representative eosinophil chemoattractant, in the BALF were measured by ELISA. The amounts of Th2 cytokines and eotaxin was increased in the BALF by transnasal Derf administration in both DBA/1J mice and SM/J mice, and these levels were markedly lower in SM/J mice than in DBA/1J mice (Fig. 5c). Th2 cytokines and eotaxin levels in BALF of PBS-exposed mice and IFN-γ levels in all BALF samples were below the detection limit (data not shown). Finally, airway reactivity was evaluated 24 h after Derf challenge by double-flow plethysmography. In the Derf groups, an aerosolized methacholine challenge induced AHR compared with the PBS groups in both DBA/1J mice (P = 0·0039) and SM/J mice (P = 0·0103), and AHR was reduced significantly in Derf-challenged SM/J mice compared with Derf-challenged DBA/1J mice (Fig. 5d).

Fig. 5.

Critical role of Neu1 sialidase in Th2-related airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) in a mouse model of Dermatophagoides farinae (Derf)-induced asthma. The absolute numbers of inflammatory cells in the bronchoalveolar fluid (BALF) were estimated as described in Materials and methods (a). CD4+T1/ST2+ T cells and CD4+Tim-3+ T cells in the BALF were determined by flow cytometry (b). BALF cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-T1ST2, phycoerythrin anti-Tim3, peridinin chlorophyll (PerCP) anti-CD3 and allophycocyanin (APC) anti-CD4. Th1 and Th2 cells were evaluated by Tim-3 and T1/ST2 expression gating on CD3+ and CD4+ T cells. (c) Concentrations of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, IL-13 and eotaxin in the BALF were determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. (d) AHR was measured and expressed in PC200 sRaw (mg/ml) as described in Materials and methods. Data represent means ± standard error of the mean. The values shown are means from six independent experiments with six to 10 mice per group; *P < 0·05 compared with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)-challenged DBA/1J mice (PBS); #P < 0·05 compared with Derf-challenged DBA/1J mice.

Discussion

CD44 is a highly glycosylated cell adhesion molecule that is involved in lymphocyte infiltration of inflamed tissues [2]. We have demonstrated previously that CD44 plays an important role in the accumulation of Th2 cells in the airway of a murine model of allergic asthma [8]. Although CD4+ T cells express CD44 on their surface, few of the cells use the molecule for recognition of HA [1]. HA binding function of CD44 is activated transiently on T cells [28], but the mechanisms associated with such changes are not understood fully. In the present study, we demonstrated the critical role of Neu1 sialidase in the receptor activity of CD44 on CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells in the spleen of the BALB/c mouse model of Derf-induced asthma showed increased in vitro CD44 receptor activity after culture with the antigen, along with characteristic parallel induction of Neu1 sialidase. The increase in HA binding ability was suppressed significantly by the sialidase inhibitor, and was not observed in the Neu1-deficient mouse strain SM/J. Finally, the accumulation of Th2 cells in the airway was reduced in the Derf-induced asthmatic SM/J mouse model.

Sialidases are a family of exoglycosidases that hydrolyze the terminal sialic acid linkage in biomolecules, such as glycoproteins, glycolipids and gangliosides. Four sialidases have been identified at the molecular level in mice. They differ from one another in terms of subcellular localization, substrate preference in vitro and tissue distribution [10,11]. mRNAs of Neu1 and Neu3, but not Neu2, are expressed highly in mouse spleen [16] and Neu4 is undetectable in spleen cells [29]. In the present study, we examined the induction of endogenous sialidases in spleen cells activated by the Derf antigen and those in CD4+ T cell clones stimulated via T cell receptors. Consistent with the earlier reports, Neu1 expression was the highest, followed by Neu3 and Neu2, and the Neu4 level was almost zero in activated spleen cells and T cell clones.

The gene that encodes or controls the activity of the murine Neu1 sialidase maps near the H-2D end of the murine major histocompatibility complex [30]. Sialidase activity is reduced in the naturally occurring inbred strain SM/J mouse strain. This defect is linked to a single gene, neu1, on chromosome 17, which was mapped by linkage analysis to the H-2 locus. SM/J mice have a single amino acid substitution (Leu 209 to Ile) in the Neu1 protein, which is responsible for the partial deficiency of lysosomal sialidase [31]. Neu1 is a lysosomal sialidase that is presumed to have narrow substrate specificity. Neu1 enzyme activity has been reported on artificial substrates such as 4-MU-NeuAc and nitrophenyl-NeuAc, but not gangliosidses, fetuin or sialyllactose [32]. Neu3 is a plasma membrane-bound sialidase, described originally as ganglioside sialidase. Neu3 preferentially hydrolyzes gangliosides, although glycoproteins, 4-MU-NeuAc, sialyllactose, etc. are also hydrolyzed [33]. In the present study, we examined Neu1 and Neu3 sialidase activity of Derf-activated spleen cells from SM/J and DBA/1J mice. Estimated Neu1 activity of antigen-activated spleen cells was reduced in SM/J mice compared with DBA/1J mice as reported previously [16], while the Neu3 activity of activated spleen cells from SM/J mice was similar to that from DBA/1J mice.

Mammalian sialidases are implicated not only in lysosomal catabolism but also in the regulation of important cellular events, including cell differentiation, cell growth and apoptosis [10]. Previous studies demonstrated that in addition to the lysosomes, Neu1 is present on the surface of activated T cells [14], where it may influence the immune function. In mouse T cells, Neu1 enzyme activity is increased upon activation by concanavalin A [34] or anti-CD3 mAb [15]. Treatment of T cells with a bacterial sialidase increases the production of IL-4, but not of IFN-γ[15]. Furthermore, ovalbumin-induced airway eosinophilia and expression of Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-13) in the lung are suppressed in SM/J mice [16]. In the present study, Derf antigen-induced asthmatic reactions, including Th2-related airway inflammation and AHR, were reduced in SM/J mice. In particular, the accumulation of Th2 cells in the airway was suppressed in SM/J mice. Furthermore, HA receptor activity of CD44 on CD4+ splenic T cells was not induced by Derf antigen stimulation in SM/J mice. Derf-sensitized splenic CD4+ T cells can induce asthmatic airway inflammation and AHR (manuscript in preparation). In addition to IL-4 production, Neu1 plays a critical role in the accumulation of Th2 cells in the airway by a CD44-dependent mechanism. Airway eosinophilia was suppressed almost completely in SM/J mice but not in DBA/1J mice. The reduction of airway eosinophilia in SM/J asthma model may be caused by the reduction of the levels of Th2 cytokine and eotaxin in BALF, while sialidase deficiency in eosinophils of SM/J mice can contribute directly to the decrease of airway eosinophils.

Previous studies have demonstrated that activated Th1 cells bind to P-selectin and migrate into inflamed tissues, whereas Th2 cells do not [35]. HA-binding ability was consistently greater on Th2 than Th1 cells in vitro, while inhibition of CD44 reduced rolling and adhesion to the intestinal vasculature similarly in Th1 and Th2 cells in vivo[36]. In the present study we found that the number of Th2 cells, but not Th1 cells, in BALF was decreased significantly in Neu1-deficient mice compared with DBA/1J mice. CD44 might contribute preferentially to the accumulation of Th2 cells into the airway compared with Th1 cells. Further examination is required to clarify the difference of CD44 function between Th1 and Th2 cells in the airway inflammation.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that the HA receptor activity of CD44 and acute asthmatic reactions are dependent upon the enzymatic activity of Neu1 sialidase. CD4+ T cells may be capable of enzymatic remodelling cell surface CD44, altering their ability to interact with HA. Our observation suggests that sialidase Neu1 could be a target molecule for the treatment of asthma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology of the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

Disclosure

None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Lesley J, Hyman R, Kincade PW. CD44 and its interaction with the extracellular matrix. Adv Immunol. 1993;54:271–335. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60537-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeGrendele HC, Estess P, Picker LJ, Siegelman MH. CD44 and its ligand hyaluronate mediate rolling under physiologic flow: a novel lymphocyte-endothelial cell primary adhesion pathway. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1119–30. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyake K, Underhill CB, Lesley J, Kincade PW. Hyaluronate can function as a cell adhesion molecule and CD44 participates in hyaluronate recognition. J Exp Med. 1990;172:69–75. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katoh S, Miyagi T, Taniguchi H, et al. An inducible sialidase regulates the hyaluronic acid binding ability of CD44-bearing human monocytes. J Immunol. 1999;162:5058–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wills-Karp M. Immunologic basis of antigen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:255–81. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeGrendele HC, Estess P, Siegelman MH. Requirement for CD44 in activated T cell extravasation into an inflammatory site. Science. 1997;278:672–5. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Katoh S, Matsumoto N, Kawakita K, Tominaga A, Kincade PW, Matsukura S. A role for CD44 in an antigen-induced murine model of pulmonary eosinophilia. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:1563–70. doi: 10.1172/JCI16583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katoh S, Ishii N, Nobumoto A, et al. Galectin-9 inhibits CD44-hyaluronan interaction and suppresses a murine model of allergic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:27–35. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1243OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schauer R. Achievements and challenges of sialic acid research. Glycoconj J. 2000;17:485–99. doi: 10.1023/A:1011062223612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyagi T, Yamaguchi K. Sialic acids. In: Kamerling JP, Boona G, Lee YC, Suzuki A, Taniguchi N, Voragen AGJ, editors. Biochemistry of glycans: sialic acids in comprehensive glycoscience. Amsterdam: Elsevier BV; 2007. pp. 297–322. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Monti E, Preti A, Venerando B, Borsani G. Recent development in mammalian sialidase molecular biology. Neurochem Res. 2002;27:649–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1020276000901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang F, Seyrantepe V, Landry K, et al. Monocyte differentiation up-regulates the expression of the lysosomal sialidase, Neu-1, and triggers its targeting to the plasma membrane via majior histocompatibility complex class II-positive compartments. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27526–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605633200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyagi T, Wada T, Yamaguchi K, Hata H, Shiozaki K. Minireview. Plasma membane-associated sialidase as a crucial regulator of transmembrane signaling. J Biochem. 2008;144:279–85. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvn089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lukong KE, Seyrantepe V, Landry K, et al. Intracellular distribution of lysosomal sialidase is controlled by the internalization signal in its cytoplasmic tail. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:46172–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X-P, Enioutina EY, Daynes RA. The control of IL-4 gene expression in activated murine T lymphocytes. A novel role for neu-1 sialidase. J Immunol. 1997;158:3070–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang P, Zhang J, Bian H, et al. Induction of lysosomal and plasma membrane-bound sialidases in human T-cell via T-cell receptor. Biochem J. 2004;380:425–33. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kincade PW, Zheng Z, Katoh S, Hanson L. The importance of cellular environment to function of the CD44 matrix receptpr. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:635–41. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohning M, Stroehmann A, Coyle AJ, et al. T1/ST2 is preferentially expressed on murine Th2 cells, independent of interleukin 4, interleukin 5, and interleukin 10, and important for Th2 effector function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6930–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhu C, Anderson AC, Schubart A, et al. The Tim-3 ligand galectin-9 negatively regulates T helper type 1 immunity. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1245–52. doi: 10.1038/ni1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminuma O, Mori A, Ogawa K, et al. Successful transfer of late-phase eosinophil infiltration in the lung by infusion of helper T cell clones. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1997;16:448–54. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.4.9115756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uemura T, Shiozaki K, Yamaguchi K, et al. Contribution of sialidase NEU1 to suppression of metastasis of human colon cancer cells through desialylation of integrin beta4. Oncogene. 2009;28:1218–29. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada T, Hata K, Yamaguchi K, et al. A crucial role of plasma membrane-associated sialidase (NEU3) in the survival of human cancer cells. Oncogene. 2007;26:2483–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyagi T, Tsuiki S. Rat-liver lysosomal sialidase: solubilization, substrate specificity and comparision with the cytosolic sialidase. Eur J Biochem. 1984;141:75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1984.tb08159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyagi T, Tsuiki S. Purification and characterization of cytosolic sialidase from rat liver. J Biol Chem. 1985;206:6710–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyagi T, Sagawa J, Konno K, Handa S, Tsuiki S. Biochemical and immunological studies on two distinct ganglioside-hydrolyzing sialidase from the particulate fraction of rat brain. J Biochem. 1990;107:787–93. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a123126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shiozaki K, Koseki K, Yamaguchi K, Shiozaki M, Narimatsu H, Miyagi T. Developmental change of sialidase Neu4 expression in murine brain and its involvement in the regulation of neuronal cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21157–64. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.012708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beck JA, Lioyd S, Hatezparast M, et al. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat Genet. 2000;24:23–5. doi: 10.1038/71641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lesley J, Howes N, Perchl A, Hyman R. Hyaluronan binding function of CD44 is transiently activated on T cells during an in vivo immune response. J Exp Med. 1994;180:383–7. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Comelli EM, Amado M, Lustig SR, Paulson JC. Identification and expression of Neu4, a novel murine sialidase. Gene. 2003;321:155–61. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carrillo MB, Milner CM, Ball ST, Snoek M, Campbell RD. Cloning and characterization of a sialidase from the murine histocompatiblity-2 complex: low levels of mRNA and a single amino acid mutation are responsible for reduced sialidase activity in mice carrying the Neu1a allele. Glycobiology. 1997;7:975–86. doi: 10.1093/glycob/7.7.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.d'Azzo A, Bonten E, Rottier RJ. A point mutation in the neu-1 locus causes the neuraminidase defect in the SM/J mouse. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:313–21. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Milner CM, Smith SV, Carrillo MB, Taylor GL, Hollinshead M, Campbell RD. Identification of a sialidase encoded in the human major histocompatibility complex. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4549–56. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasegawa T, Yamaguchi K, Wada T, Takeda A, Itoyama Y, Miyagi T. Molecular cloning of mouse ganglioside sialidase and its increased expression in Neuro2a cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8007–15. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.8007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Landolfi NF, Leone J, Womack JE, Cook RG. Activation of T lymphocytes results in an increase in H-2-encoded neuraminidase. Immunogenetics. 1985;22:159–67. doi: 10.1007/BF00563513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blander JM, Visintin I, Janeway CA, Jr., Medzhitov R. alpha(1,3)-Fucosyltransferase VII and a(2,3)-sialyltransferase IV are up-regulated in activated CD4 T cells and maintained after their differentiation into Th1 and migration into inflammatory sites. J Immunol. 1999;163:3746–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bonder CS, Clark SR, Norman MU, Johnson P, Kubes P. Use of CD44 by CD4+ Th1 and Th2 lymphocytes to roll and adhere. Blood. 2006;107:4798–806. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]