Abstract

Leucocyte transendothelial migration is strictly regulated to prevent undesired inflammation and collateral damage of endothelial cells by activated neutrophils/monocytes. We hypothesized that in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) patients' dysregulation of this process might underlie vascular inflammation. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and neutrophils from AAV patients (n = 12) and healthy controls (HC, n = 12) were isolated. The influence of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) on neutrophil/monocytes function was tested by N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenyl-alanine (fMLP)- and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-mediated ROS production, degranulation and interleukin (IL)-8 production. In addition, the ability of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-stimulated PBMC to produce tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α in the presence or absence of HUVEC was tested. HUVEC inhibited ROS production dose-dependently by fMLP-stimulated neutrophils but did not influence degranulation. No differences between neutrophils from HC and AAV were found. However, in only one active patient was degranulation inhibited significantly by HUVEC only before cyclophosphamide treatment, but not 6 weeks later. Co-cultures of HUVEC with LPS-stimulated neutrophils/monocytes increased IL-8 production while TNF-α production was inhibited significantly. There was no apparent difference between AAV patients and HC in this respect. Our findings demonstrate that HUVEC are able to inhibit ROS and modulate cytokine production upon stimulation of neutrophils or monocytes. Our data do not support the hypothesis that endothelial cells inhibit ROS production of neutrophils from AAV patients inadequately. Impaired neutrophil degranulation may exist in active patients, but this finding needs to be confirmed.

Keywords: ANCA-associated vasculitis, cytokines, degranulation, endothelial cells, reactive oxygen species

Introduction

The vascular endothelium is of eminent importance controlling a number of crucial homeostatic functions, including coagulation, fluid exchange with the tissue and aiding in immune surveillance for pathogens [1]. Under pathological conditions, e.g. during infections or inflammatory diseases, proinflammatory molecules are produced and activate the endothelium. When activated, the endothelial phenotype is changed dramatically to support leucocyte egress from the circulation [2]. Although leucocyte recruitment provides the first line of defence, it might also cause tissue injury and microvascular dysfunction [3]. Undoubtedly, the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by activated neutrophils or monocytes has the propensity to affect the integrity of the endothelium. Also, neutrophil degranulation can lead to tissue injury through the action of several serine and neutral proteases that have the capacity to degrade a broad spectrum of extracellular matrix proteins. These proteases can be internalized by endothelial cells and may initiate apoptosis in a nuclear factor kappa-β (NF-κB)-dependent fashion, as has been shown for proteinase-3 (PR-3) [4,5]. However, neutrophil degranulation also seems to provide a beneficial effect on transendothelial migration via the release of neutrophil elastase (NE). In NE–/– mice, neutrophil migration into lung tissue is impaired severely [6]. Similarly, Young et al. [7] have shown that pharmacological inhibition of NE impairs leukotriene B4 (LTB4)-induced neutrophil transmigration. Impaired neutrophil migration can result in more profound tissue injury as a consequence of prolonged neutrophil–endothelial interactions [6]. Regulation of oxidative burst and degranulation at the vascular interface is therefore pivotal to allow proper egress from the circulation. Deregulation of these processes may account for impaired neutrophil migration, leading subsequently to vascular injury.

In anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies (ANCA)-associated small vessel systemic vasculitis, e.g. Wegener's granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis, Churg–Strauss syndrome and ANCA-positive rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis (RPGN), it is believed that concomitant binding of ANCA to their putative antigens and to Fc receptors on the cell surface of neutrophils or monocytes is a critical event in the pathogenesis of these diseases [8]. Binding of ANCA to tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α-primed neutrophils leads unambiguously to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can subsequently damage the endothelium [8,9,10]. Recently, however, Lu et al. [11] have reported that endothelial cells have the intrinsic property to inhibit ROS production by neutrophils via the release of adenosine. This therefore raises the question of to what extent ROS production by ANCA-stimulated neutrophils is important in the pathogenesis of AAV. It must be emphasized, however, that studies using neutrophils from AAV patients have not been performed in such a setting; hence it is not known if neutrophils from these patients behave similarly to healthy controls. If endothelial cells do not inhibit oxidative burst or degranulation in neutrophils from AAV patients, this could explain, at least partly, the vascular pathology observed in AAV patients. Hence, this study was undertaken to test the hypothesis that in the interaction of endothelial cells with neutrophils of AAV patients there is a lack in the control of oxidative burst and degranulation.

Materials and methods

Media and reagents

The reagents used were Ficoll-Hypaque™ (Amersham Biosciences, Freiburg, Germany), luminol, p-coumaric acid, formyl-met-leu-phe (fMLP), cytochalasin B, phorbol myristate acetate (PMA), 5′-(N-ethyl carboxamido)adenosine (NECA), dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), adenosine deaminase (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), Iscove's modified Dulbecco's medium (IMDM) (PAN Biotec, Aidenbach, Germany), endothelial cell growth medium (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany), phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco Invitrogen, Karlsruhe, Germany), lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli and 1 × lysis buffer [155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0·1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA)].

Patients

All patients had histologically proven disease and were classified according to the Chapel Hill nomenclature as Wegeners's granulomatosis (n = 10) and microscopic polyangiitis (n = 2). All patients were ANCA-positive by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and indirect immunofluorescence (C-ANCA in 10 patients, P-ANCA in two patients). Disease activity was evaluated according to clinical and radiological parameters and assessed according to the Birmingham Vasculitis Activity Score (BVAS). At the time of blood collection, all but one patient were in complete remission. Treatment at the time of blood collection consisted of glucocorticosteroids (n = 8), mycophenolate–mofetil (n = 4), azathioprine (n = 2) and cyclophosphamide (n = 3). One patient was in stable remission without any immunosuppressive treatment (Table 1). The study was approved by the local ethics committee and all patients and controls gave informed consent.

Table 1.

Clinical data.

| No | Diagnosis | IIF | ELISA | Organ involvement | Immunosuppression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, K, L, PNP, CNS | Pred 5 mg |

| 2 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, K, L, PNP, CNS, J | Pred 7·5 mg, MMF 1·5 g |

| 3 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, K, J | Pred 7·5 mg, Aza 150 mg |

| 4 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, L | Pred 4 mg, MMF 1g |

| 5 | MPA | p-ANCA | MPO | L, K | Pred 15 mg, CYC |

| 6 | MPA | p-ANCA | MPO | K | Pred, CYC, PE |

| 7 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, E, K | Pred, CYC |

| 8 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, L, K | Aza 25 mg |

| 9 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, L, K, E; J, PNP | Pred 10 mg |

| 10 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | L, K, PNP | None |

| 11 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, L, K, J | MMF 0·5 g |

| 12 | WG | c-ANCA | PR-3 | ENT, L, K, J | MMF 1 g |

Aza, azathioprine; CNS, central nervous system; CYC, cyclophosphamide boli; E, eyes; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; ENT, ear, nose, throat; IIF, indirect immunofluorescence; J, joints; K, kidney; L, lung; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, microscopic polyangiitis; MPO, myeloperoxidase; PE, plasma exchange; PNP, polyneuropathy; PR-3, proteinase-3; Pred, prednisolone; WG, Wegener's granulomatosis.

Cell isolation and co-culture

EDTA–blood was diluted 1 : 1 (v/v) with PBS and layered carefully on 15 ml of Ficoll-Hypaque. After centrifugation at 400 g for 30 min at room temperature, the interface, representing peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), was used for co-culture experiments as described below. The sediment was resuspended in 50 ml of 155 mM ammonium chloride buffer followed by incubation for 15 min at room temperature. The tubes were then centrifuged at 400 g for 10 min at room temperature and the sediment was resuspended in 50 ml of PBS. The cells were washed twice with PBS and finally resuspended in IMDM medium. Purified cells were counted on a Casy1 TT instrument (Schärfe System, Reutlingen, Germany). The purity ranged from 97% to 99%.

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) were isolated from fresh umbilical cords. The cells were cultured in essential growth medium for endothelial cells in gelatin-coated culture flasks at 37°C, 95% relative humidity and 5% CO2. Confluent monolyers were passaged by trypsin 0·025%/EDTA 0·01%. In co-culture experiments HUVEC were seeded in 24-well plates and grown until confluence. All experiments involving HUVEC were performed in passages 3–5. Depending on the experiment, neutrophils or PBMC were added in 1 ml to the wells at a concentration of 106 cells/ml.

ROS production

ROS production was measured by luminol-amplified chemiluminescence, as described previously [12,13]. Briefly, 5 × 106 neutrophils were placed in vials to which different amounts of HUVEC were added. To each vial Luminol (2·5 mM) and p-coumaric acid (0·9 mM) dissolved in 1 ml of IMDM medium were added and the cells were incubated for 30 min at 37°C. In some experiments, NECA (50 µM) or adenosine deaminase (50 U/ml) was added. The cells were then stimulated with fMLP (10 µM) or PMA (1 µg/ml) and the chemiluminescence signal was measured at various time intervals after stimulation in a Luminometer (Lumat LB9507; Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany) over a period of 20 min.

Neutrophil degranulation

Neutrophil degranulation was assessed by myeloperoxidase (MPO) release. To this end, a chemiluminescence assay for MPO using the luminol reaction was standardized with commercial horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (500, 250, 125, 62·5, 31·25, 15·62 mU/ml) and H2O2 0·003%). Similar to the above, 5 × 106 neutrophils were placed in vials to which different amounts of HUVEC were added. The cells were stimulated with fMLP (10 µM) or PMA (1 µg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C. MPO release was measured by serial dilution of the supernatants in luminol reaction mix [luminol (2·5 mM), p-coumaric acid (0·9 mM) and H2O2 (0·003%)]. Chemiluminescence was completely dependent upon the presence of exogenous H2O2 (0·003%) and occurred only after neutrophil stimulation.

Cytokine production

HUVEC (105 cells/ml) were seeded in 24-well plates and grown until confluence. Hereafter, neutrophils or PBMC were added at 1 ml to the wells in a concentration of 106 cells/ml. HUVEC, neutrophils or PBMC alone were included in each experiment. The cells were stimulated for 24 h with 1 µg/ml of LPS. Supernatants were collected and assessed for TNF-α and IL-8 production by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (R&D Systems GmbH, Wiesbaden, Germany). ELISA was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each experimental condition was performed in duplicate and each experiment was confirmed at least three times.

Statistical analysis

Non-parametric methods were used for statistical analysis. Two groups were compared by means of Mann–Whitney U-test. For more than two groups, the Kruskal–Wallis test was performed. All data are given as means ± standard deviation (s.d.). A two-sided P < 0·05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Similar to the unspecific adenosine receptor agonist NECA, endothelial cells inhibited ROS production efficiently by fMLP-stimulated neutrophils (Fig. 1a). Inhibition had occurred already at a neutrophil : endothelial cell ratio of 50 : 1. Higher ratios increased the inhibitory effect slightly but this was not significant, and therefore 50 : 1 was used in all consecutive experiments. To substantiate further the involvement of adenosine in the inhibition of ROS production, adenosine deaminase (ADA) was used. As demonstrated in Fig. 1b, ADA could partly overcome the inhibitory effect of endothelial cells (Fig. 1b). Inhibition of ROS production occurred only after fMLP stimulation, but was not observed when PMA was used. In some experiments endothelial cells or NECA enhanced ROS production by PMA-stimulated neutrophils (Fig. 1c). Degranulation of fMLP-stimulated neutrophils, as assessed by MPO release, was not influenced by endothelial cells, although this was inhibited to some extent by NECA (Fig. 1d). Following PMA stimulation, as seen for ROS production, endothelial cells did not influence degranulation consistently. While in some experiments HUVEC did not influence MPO release, in other experiments an increase in MPO release was observed when HUVEC were added (Fig. 1e).

Fig. 1.

Influence of endothelial cells on neutrophil-reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and degranulation. (a) ROS production was measured in formyl-met-leu-phe (fMLP)-stimulated neutrophils to which endothelial cells were added at a ratio of 50 : 1 (neutrophils : endothelial cells) (filled squares). ROS production in the absence of endothelial cells was also measured (open squares). In addition, neutrophils were stimulated in the presence of 50 µM of 5′-(N-ethyl carboxamido)adenosine (NECA) (dashed symbol). **P<0·01, fMLP-stimulated neutrophils versus fMLP-stimulated neutrophils in the presence of endothelial cells and for fMLP-stimulated neutrophils versus fMLP-stimulated neutrophils in the presence of NECA. (b) Neutrophils were stimulated as in (a). Adenosine deaminase 10 units (dashed symbol) or an equal volume of medium (filled squares) was added to the combination of neutrophils and endothelial cells. fMLP-stimulated neutrophils served as control. *Adenosine deaminase versus medium, **fMLP-stimulated neutrophils versus fMLP-stimulated neutrophils in the presence of endothelial cells. (c) ROS production was measured in phorbol myristate acetate (PMA)-stimulated neutrophils essentially as described in (a). PMA stimulation alone (open squares), PMA stimulation in the presence of endothelial cells (filled squares), PMA stimulation in the presence of NECA (dashed symbol). (d) Degranulation of fMLP-stimulated neutrophils. Neutrophils were either stimulated with fMLP (10 µM) for 1 h at 37°C (hatched bars) or left untreated (open bars). During the incubation neutrophils were either in normal RPMI-1640 medium, in RPMI-1640 medium containing 100 µM NECA or endothelial cells were added to the neutrophils at a ratio of 50 : 1. After 1 h, the supernatants were collected and assessed for myeloperoxidase (MPO) release, as described in the Materials and methods. (e) Degranulation of PMA-stimulated neutrophils. The experiments were performed essentially as described in (d). For all experiments (a–e), the results of three independent experiments are expressed as mean relative light unit (RLU) ± standard deviation.

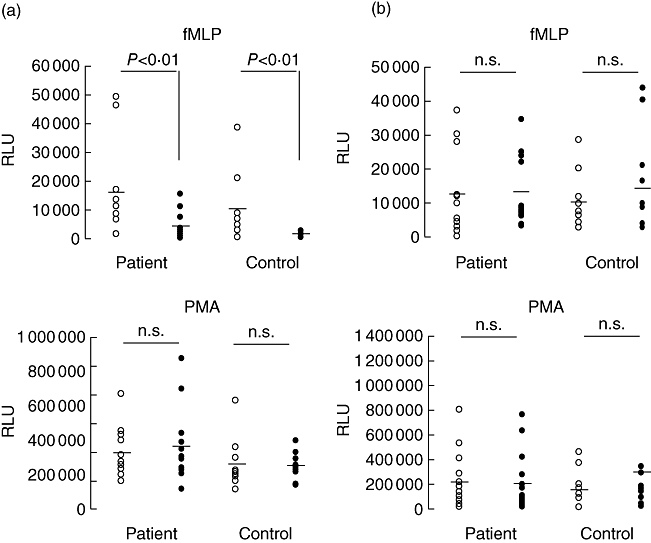

We next assessed if the behaviour of neutrophils from AAV patients was different from that of healthy controls (HC) when stimulated in the presence or absence of endothelial cells. There was a tendency that ROS production by fMLP-stimulated neutrophils was higher in patients compared to HC, but this did not reach statistical significance. In both patients and controls, addition of endothelial cells inhibited ROS production significantly (Fig. 2a, upper graph). Inhibition occurred only after fMLP but not after PMA stimulation (Fig. 2a, lower graph). Neither in patients nor in controls was degranulation influenced by endothelial cells (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Neutrophil-reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and degranulation in patients and controls. (a) ROS production in formyl-met-leu-phe (fMLP) (upper graph) and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) (lower graph)-stimulated neutrophils. Stimulation occurred in the presence (filled circles) or absence (open circles) of endothelial cells (ratio 50 : 1). (b) Neutrophil degranulation of fMLP (upper graph) and PMA (lower graph)-stimulated neutrophils. The results are expressed as peak relative light unit (RLU) signal for each patient (n = 12) and controls (n = 12). The mean in each group is represented by the dashed symbol.

All patients, with one exception, were in remission at the time of blood collection. In the active patient we were able to test neutrophils before cyclophosphamide treatment, and 6 weeks later under immunosuppressive treatment (Fig. 3). Interestingly, we observed that endothelial cells inhibited both ROS production and degranulation when neutrophils were tested before treatment. Six weeks after the initiation of treatment only ROS production was inhibited, while endothelial cells no longer inhibited neutrophil degranulation (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Influence of endothelial cells on neutrophil-reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and degranulation in an active patient before and 6 weeks after initiation of cyclophosphamide. Upper graph shows the effect of endothelial cells on neutrophil ROS production. Neutrophils were stimulated with formyl-met-leu-phe (fMLP) in the absence (open symbols) or presence of endothelial cells (filled symbols). Lower graphs represent neutrophil degranulation. Neutrophils were stimulated with fMLP for 1 h in the absence (open bars) or presence of endothelial cells (filled bars). Hereafter the supernatants were collected and assessed for myeloperoxidase (MPO) release as described. The results are expressed as mean relative light unit (RLU) of triplicate determinations ± standard deviation.

Because TNF-α plays an important role in ANCA-mediated ROS production by neutrophils, and IL-8 is an important chemoattractant for neutrophils, we also tested if endothelial cells are able to modulate the production of these cytokines. LPS-mediated production of TNF-α by PBMC was not different between patients and controls. When PBMC were co-cultured with endothelial cells, there was a significant reduction in TNF-α production. This was observed in both in patients and HC (Fig. 4a). Also, IL-8 production was influenced by endothelial cells. In these experiments IL-8 produced in co-cultures of endothelial cells and neutrophils was corrected for IL-8 production by endothelial cells alone. As shown in Fig. 4b, IL-8 production was higher in general in co-cultures compared to cultures of neutrophils alone. While the difference was statistically significant in HC, in patients only a trend was observed.

Fig. 4.

Influence of endothelial cells on lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-8 production in co-cultures. (a) Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were either added to confluent monolayers of endothelial cells (filled symbols) or seeded in a similar concentration to 24-well plates in the absence of endothelial cells (open symbols). Hereafter the cells were stimulated with LPS 1 µg/ml for 24 h. Supernatants were collected and tested for TNF-α production by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Each patient and each control was tested in triplicate. LPS-stimulated human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) was included in each experiment. The results are expressed as mean TNF-α production (pg/ml) for each patient (n = 12) and controls (n = 12). The mean in each group is represented by the dashed symbol. (b) Neutrophils were either added to confluent monolayers of endothelial cells (filled symbols) or were seeded in a similar concentration in 24-well plates in the absence of endothelial cells (open symbols). Hereafter the cells were stimulated with LPS 1 µg/ml for 24 h. Supernatants were collected and tested for IL-8 production by ELISA. LPS-stimulated HUVEC was included in each experiment to control for IL-8 production by HUVEC alone. IL-8 production of HUVEC alone was subtracted from the IL-8 production in co-cultures of HUVEC and neutrophils. The results are expressed as mean IL-8 production (pg/ml) for each patient (n = 12) and controls (n = 12). The mean in each group is represented by the dashed symbol.

Discussion

In lesions of small-vessel systemic vasculitis patients inflammatory cells accumulate and surround the vessel, leading ultimately to fibrinoid necrosis within the vessel wall. The increased number of circulating endothelial cells, as observed in active patients [14], might be a reflection of endothelial cell injury at the site of vascular lesions inflicted by invading inflammatory cells. However, how the inflammatory cells mediate endothelial cell injury is unclear at present. It has been shown recently for neutrophils from healthy individuals [11] that endothelial cells are able to inhibit fMLP-mediated neutrophil superoxide release. Similar studies with the use of neutrophils from vasculitis patients are still lacking. Therefore it is possible that neutrophils from patients behave differently at the vascular interface, and perhaps do not decrease ROS production when in contact with endothelial cells. In the present study we tested the hypothesis that in AAV patients endothelial cells are not able to control oxidative burst and or degranulation of neutrophils.

The main findings of this study are the following: first, our study confirms and extends previous data that endothelial cells inhibit ROS production, but not degranulation, of fMLP-activated neutrophils. Endothelial cells neither inhibit ROS production nor degranulation when neutrophils are challenged with PMA. Second, healthy controls and patients in remission do not differ in this respect. However, in the only active patient who was studied, degranulation was inhibited by endothelial cells before initiation of treatment but not 6 weeks later under immunosuppressive treatment. Third, endothelial cells inhibit LPS-mediated TNF-α production in co-cultures of endothelial cells and PBMC, but enhance IL-8 production in co-cultures of neutrophils and endothelial cells. This was also not different between patients and controls.

Like many other cells, human neutrophils release ATP in response to a number of stimuli in a connexin 43-dependent manner [15–17]. Hence neutrophils are an important source of extracellular nucleotides during inflammation [18–21]. Current evidence indicates that once ATP is released from neutrophils it either functions as a direct signalling molecule [22] or is converted rapidly to adenosine via the consecutive action of CD39 and CD73. Depending on the cell and receptors to which adenosine engage, it affects leucocyte trafficking in several ways [23]. Adenosine is able to act as chemoattractant by binding to the A3 adenosine receptor (A3AR) [24], but also increases the vascular barrier function of endothelial cells. A number of studies have also shown that adenosine is a potent inhibitor of neutrophil ROS production via binding to the A2AAR [25,26]. Because CD73 is expressed at the surface of endothelial cells, this might explain the inhibitory effect of endothelial cells on neutrophil ROS production. Interestingly, endothelial cells inhibited ROS production only when neutrophils were stimulated with fMLP but not with PMA. This might be explained by the fact that fMLP activates neutrophils in a receptor-dependent fashion, while PMA activated protein kinase C (PKC) directly.

Several reports have indicated that neutrophils from AAV patients differ from healthy controls [27–29]. Gene expression profile studies revealed a distinct profile in AAV patients compared to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients and healthy controls [27]. Importantly, genes that correlated with clinical activity in AAV patients were neutrophil-specific. In keeping with the classical view on the pathomechanism in AAV, in which neutrophils in conjunction with ANCA appear to be the key players, our findings are unexpected. It might be that although differences in gene expression in neutrophils exist between patients and healthy individuals, and even in PR3 expression, this does not translate directly into functional differences with respect to endothelial cell–neutrophil interactions. Our study shows that neutrophils from AAV patients behave similarly to that of healthy individuals with respect to inhibition of ROS production by endothelial cells. Nevertheless, it would be prudent to be cautious in concluding that adenosine generation, as a negative feedback in control of the oxidative burst, is not impaired in these patients. In our in vitro model ATP might be released in higher amounts from endothelial cells than from neutrophils, and hence adenosine generation would not be affected when neutrophils from patients are tested. One should also be aware that macrovascular endothelial cells from healthy individuals were used in our study. These cells may release more ATP compared to microvascular endothelial cells, or may differ in CD73 expression.

We are aware that neutrophil egress from the circulation occurs in smaller vessels, and therefore microvascular endothelial cells would be more appropriate to use than HUVEC. However, this study was not intended to investigate the role of the endothelium in the process of immune modulation but to test if the behaviour of neutrophils from vasculitis patients is essentially different compared to that of healthy controls.

Eight of twelve patients were on glucocorticoids at the time of blood collection. We are well aware of the fact that glucocorticoids may influence the oxidative burst in neutrophils and monocytes [30,31], yet neither in the absence nor in the presence of endothelial cells was there a difference between patients and controls regarding ROS production. With one exception, neutrophils from all patients reacted similarly, i.e. endothelial cells inhibited oxidative burst but not degranulation. In the only active patient, however, degranulation was inhibited strongly before cyclophosphamide treatment was initiated, but not 6 weeks later when the patient was under immunosuppression. Clearly, this casuistic finding should be confirmed in other active patients before firm conclusions can be drawn on the effect of medication. Failure of neutrophils to degranulate might be a double-edged sword. On one hand, it might reduce endothelial cell apoptosis caused by internalization of PR-3 by endothelial cells [4,5]; on the other hand, it might also cause sticking of neutrophils between endothelial cells as a consequence of low elastase concentrations.

Cockwell et al. [32] have postulated that frustrated neutrophil transmigration in AAV patients could contribute to bystander damage of endothelial cells. They have suggested that this might be caused by neutrophil IL-8 production within the glomerular capillary loops. Our data are in line with Cockwell et al. by showing that IL-8 production of activated neutrophils is increased when cultured in the presence of endothelial cells.

We also observed that LPS-mediated TNF-α production by PBMC was decreased significantly in co-culture experiments. We did not study whether this was mediated by adenosine, but others have shown that TNF-α production by monocyte is inhibited in an A2AR-dependent fashion [33,34].

In conclusion, our data do not support the hypothesis that endothelial cells inhibit ROS production of neutrophils from AAV patients inadequately. Impaired neutrophil degranulation may exist in active patients, but this finding needs to be confirmed. It also remains to be elucidated how and if immune modulation at the vascular interface is impaired in vasculitis patients. Further studies are warranted to address if ATP release by activated neutrophils is diminished in these patients. Similarly, the expression of CD39 and CD73 at vasculitic lesion might provide further clues as to whether the lack of adenosine generation might underlie vascular damage at these sites.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant of the International Research training group GRK 880 ‘Vascular Medicine’.

Disclosure

On behalf of all authors no conflicts of interest are to be disclosed.

References

- 1.Pober JS, Min W, Bradley JR. Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction, injury, and death. Annu Rev Pathol. 2009;4:71–95. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saeed RW, Varma S, Peng-Nemeroff T, et al. Cholinergic stimulation blocks endothelial cell activation and leukocyte recruitment during inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1113–23. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu L, He P. fMLP-stimulated release of reactive oxygen species from adherent leukocytes increases microvessel permeability. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H365–H372. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00812.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang JJ, Preston GA, Pendergraft WF, et al. Internalization of proteinase 3 is concomitant with endothelial cell apoptosis and internalization of myeloperoxidase with generation of intracellular oxidants. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:581–92. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64000-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preston GA, Zarella CS, Pendergraft WF, et al. Novel effects of neutrophil-derived proteinase 3 and elastase on the vascular endothelium involve in vivo cleavage of NF-kappaB and proapoptotic changes in JNK, ERK, and p38 MAPK signaling pathways. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2840–9. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000034911.03334.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaynar AM, Houghton AM, Lum EH, Pitt BR, Shapiro SD. Neutrophil elastase is needed for neutrophil emigration into lungs in ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:53–60. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0315OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Young RE, Voisin MB, Wang S, Dangerfield J, Nourshargh S. Role of neutrophil elastase in LTB4-induced neutrophil transmigration in vivo assessed with a specific inhibitor and neutrophil elastase deficient mice. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;151:628–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falk R, Terrell RS, Charles LA, Jennette JC. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibodies induce neutrophils to degranulate and produce oxygen radicals in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4115–19. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cid MC, Segarra M, Garcia-Martinez A, Hernandez-Rodriguez J. Endothelial cells, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and cytokines in the pathogenesis of systemic vasculitis. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2004;6:184–94. doi: 10.1007/s11926-004-0067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harper L, Savage CO. Mechanisms of endothelial injury in systemic vasculitis. Adv Nephrol Necker Hosp. 1999;29:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu X, Garfield A, Rainger GE, Savage CO, Nash GB. Mediation of endothelial cell damage by serine proteases, but not superoxide, released from antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-stimulated neutrophils. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:1619–28. doi: 10.1002/art.21773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kikuchi T, Suzuki K, Abe T, et al. Measurement of chemiluminescence from neutrophils in a 96-well microplate using Lumi Box U-800 II. J Biolumin Chemilumin. 1997;12:149–53. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1271(199705/06)12:3<149::AID-BIO440>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki K, Sato H, Kikuchi T, et al. Capacity of circulating neutrophils to produce reactive oxygen species after exhaustive exercise. J Appl Physiol. 1996;81:1213–22. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1996.81.3.1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woywodt A, Streiber F, de Groot K, Regelsberger H, Haller H, Haubitz M. Circulating endothelial cells as markers for ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis. Lancet. 2003;361:206–10. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12269-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckardt D, Theis M, Degen J, et al. Functional role of connexin43 gap junction channels in adult mouse heart assessed by inducible gene deletion. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eltzschig HK, Eckle T, Mager A, et al. ATP release from activated neutrophils occurs via connexin 43 and modulates adenosine-dependent endothelial cell function. Circ Res. 2006;99:1100–8. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000250174.31269.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodenough DA, Paul DL. Beyond the gap: functions of unpaired connexon channels. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:285–94. doi: 10.1038/nrm1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bodin P, Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling: ATP release. Neurochem Res. 2001;26:959–69. doi: 10.1023/a:1012388618693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eltzschig HK, Macmanus CF, Colgan SP. Neutrophils as sources of extracellular nucleotides: functional consequences at the vascular interface. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18:103–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roman RM, Feranchak AP, Davison AK, Schwiebert EM, Fitz JG. Evidence for Gd(3+) inhibition of membrane ATP permeability and purinergic signaling. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1222–30. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yegutkin G, Bodin P, Burnstock G. Effect of shear stress on the release of soluble ecto-enzymes ATPase and 5′-nucleotidase along with endogenous ATP from vascular endothelial cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;129:921–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erlinge D. Extracellular ATP: a central player in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle phenotype. Focus on ‘Dual role of PKA in phenotype modulation of vascular smooth muscle cells by extracellular ATP’. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C260–2. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00217.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reutershan J, Vollmer I, Stark S, Wagner R, Ngamsri KC, Eltzschig HK. Adenosine and inflammation: CD39 and CD73 are critical mediators in LPS-induced PMN trafficking into the lungs. FASEB J. 2009;23:473–82. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-119701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Y, Corriden R, Inoue Y, et al. ATP release guides neutrophil chemotaxis via P2Y2 and A3 receptors. Science. 2006;314:1792–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1132559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cronstein BN, Rosenstein ED, Kramer SB, Weissmann G, Hirschhorn R. Adenosine; a physiologic modulator of superoxide anion generation by human neutrophils. Adenosine acts via an A2 receptor on human neutrophils. J Immunol. 1985;135:1366–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaufmann I, Hoelzl A, Schliephake F, et al. Effects of adenosine on functions of polymorphonuclear leukocytes from patients with septic shock. Shock. 2007;27:25–31. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000238066.00074.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alcorta DA, Barnes DA, Dooley MA, et al. Leukocyte gene expression signatures in antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody and lupus glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 2007;72:853–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schreiber A, Otto B, Ju X, et al. Membrane proteinase 3 expression in patients with Wegener's granulomatosis and in human hematopoietic stem cell-derived neutrophils. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2216–24. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004070609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rarok AA, Stegeman CA, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Neutrophil membrane expression of proteinase 3 (PR3) is related to relapse in PR3-ANCA-associated vasculitis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2232–8. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000028642.26222.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davtyan TK, Mkrtchyan NR, Manukyan HM, Avetisyan SA. Dexamethasone, colchicine and iodine–lithium–alpha–dextrin act differentially on the oxidative burst and endotoxin tolerance induction in vitro in patients with Behcet's disease. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Citarella BV, Miskolci V, Vancurova I, Davidson D. Interleukin-10 versus dexamethasone: effects on polymorphonuclear leukocyte functions of the newborn. Pediatr Res. 2009;65:425–9. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e318199384d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cockwell P, Brooks CJ, Adu D, Savage CO. Interleukin-8: a pathogenetic role in antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1999;55:852–63. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.055003852.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun WC, Moore JN, Hurley DJ, et al. Adenosine A2A receptor agonists inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha by equine monocytes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2008;121:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang JG, Hepburn L, Cruz G, Borman RA, Clark KL. The role of adenosine A2A and A2B receptors in the regulation of TNF-alpha production by human monocytes. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:883–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]