Abstract

Background

Arrhythmias are benign or lethal depending on their sustainability and frequency. To determine why lethal arrhythmias are prone to occur in diseased hearts, usually characterized by non-uniform muscle contraction, we investigated the effect of non-uniformity on sustainability and frequency of triggered arrhythmias.

Methods and Results

Force, membrane potential, and intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) were measured in 51 rat ventricular trabeculae. Non-uniform contraction was produced by exposing a restricted region of muscle to a jet of 20 mmol/L 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM) or 20 μmol/L blebbistatin. Sustained arrhythmias (>10 s) could be induced by stimulus trains for 7.5 s only with the BDM or blebbistatin jet (100 nmol/L isoproterenol, 1.0 mmol/L [Ca2+]o, 24°C). During sustained arrhythmias, Ca2+ surges preceded synchronous increases in [Ca2+]i, while the stoppage of the BDM jet made the Ca2+ surges unclear and arrested sustained arrhythmias (n = 6). With 200 nmol/L isoproterenol, 2.5 mmol/L [Ca2+]o, and the BDM jet, lengthening or shortening of the muscle during sustained arrhythmias accelerated or decelerated their cycle both in the absence (n = 10) and the presence of 100 μmol/L streptomycin (n = 10), a stretch-activated channel blocker, respectively. The maximum rate of force relaxation correlated inversely with the change in cycle lengths (n = 14, P<0.01). Sustained arrhythmias with the BDM jet were significantly accelerated by 30 μmol/L SCH00013, a Ca2+ sensitizer of myofilaments (n = 10).

Conclusion

These results suggest that non-uniformity of muscle contraction is an important determinant of the sustainability and frequency of triggered arrhythmias due to the surge of Ca2+ dissociated from myofilaments in cardiac muscle.

Keywords: triggered activity, contraction, calcium, non-uniform myocardium

Introduction

Abnormal automaticity,1 re-entry due to slow conduction and heterogeneous repolarization,2, 3 and delayed4, 5 or early afterdepolarizations6 caused by alteration in Ca2+ handling7 are mechanisms responsible for life-threatening arrhythmias in diseased hearts.8, 9 Among these mechanisms, delayed afterdepolarizations (DADs) play an important role, especially in arrhythmias associated with catecholamine-excess,10, 11 heart failure,12-14 and mutations of the ryanodine receptor or calsequestrin.15 These arrhythmias can be benign or lethal in nature depending on their hemodynamic consequence, which is regulated by various factors, including their duration and ventricular rate, that is, sustainability and frequency.16, 17 While it has been reported that the sustainability and frequency of re-entrant arrhythmias are at least in part determined by the wavelength of re-entering impulse and the circuit path,18 what determines the sustainability and frequency of triggered arrhythmias remains to be established.19, 20

In diseased hearts, non-uniform muscle contraction commonly occurs21, 22 as a result of muscle damage,23, 24 heterogeneous adrenergic activation,25, 26 heterogeneous protein expression,27 or non-uniform electrical activation.28 In such diseased hearts, a surge of Ca2+ emerges in the border zone (BZ) between contracting and stretched regions of the muscle due to dissociation of Ca2+ from the myofilaments during relaxation,29 initiates Ca2+ waves by regenerative Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR) from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR),29 elicits DADs,30 and frequently induces triggered arrhythmias.29, 31 However, whether this non-uniformity of muscle contraction affects the sustainability and frequency of already initiated triggered arrhythmias remains unknown.

Thus, in the present study we investigated the effect of non-uniform muscle contraction on the sustainability and frequency of triggered arrhythmias using a model of non-uniform contraction in rat cardiac trabeculae. Our results indicate that non-uniformity of muscle contraction is an important determinant of the sustainability and frequency of triggered arrhythmias due to the surge of Ca2+ that has been dissociated from the myofilaments within the BZ during the relaxation phase.

Materials and Methods

Measurements of force, membrane potential, [Ca2+]i and sarcomere length in rat trabeculae

All animal procedures were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996) and were approved by the Ethics Review Board of Tohoku University (approval reference number: 20-4). Briefly, trabeculae (n = 51, length: 2.3 ± 0.3 mm, width: 229 ± 75 μm, thickness: 83 ± 3 μm in an unloaded condition) were dissected from the right ventricle of rat hearts and mounted on an inverted microscope between a force transducer and a micromanipulator with a direct current torque motor, which was controlled by a computer. All preparations were continuously superfused with HEPES solution as in.32 Sarcomere length (SL) was determined from the first order of the He-Ne laser light diffraction band, and membrane potential was measured using ultracompliant glass microelectrodes, as previously described.30

[Ca2+]i was measured as previously described.32 Briefly, fura-2 pentapotassium salt was microinjected electrophoretically into a mounted trabecula. Excitation light of 340, 360, or 380 nm was used and the fluorescence was collected using a photomultiplier tube or an image intensified CCD camera (30 frames/s) to assess local [Ca2+]i. We calculated [Ca2+]i from the calibrated ratio of F360/F380 in the region of interest along the trabecula (see Supplemental Methods in the Online Supplemental Material).

Reduction of local contraction

A non-uniform muscle contraction model was created as previously described (see Supplemental Methods and Figures in the Online Supplemental Material).30 Briefly, a restricted region of a trabecula was exposed to a small jet of solution (≈0.06 mL/min) directed perpendicular to a small muscle segment (≈300 μm) using a syringe pump connected to a glass pipette (≈100 μm in diameter). To purposefully reduce contraction in the exposed region, the jet solution was composed of standard HEPES solution containing 20 mmol/L 2,3-butanedione monoxime (BDM) or 20 μmol/L blebbistatin, a myosin II ATPase inhibitor.33, 34 The Ca2+ and isoproterenol in the jet solution were the same concentrations as those in the HEPES superfusion solution.

Experimental protocol

In the present study we defined twitch contractions induced by trains of electrical stimulation as “triggered arrhythmias” and the triggered arrhythmias lasting more than 10 s as “sustained arrhythmias”.

First, to investigate the effect of non-uniform muscle contraction on the sustainability of triggered arrhythmias, trains of electrical stimuli of 7.5 s duration and at various stimulus intervals were repeated every 15 s in 23 trabeculae. The longest stimulus interval, which induced sustained arrhythmias, was then determined in the presence and the absence of the regional BDM or blebbistatin jet because it is known that shorter stimulus intervals are prone to induce triggered arrhythmias35 ([Ca2+]o = 1.0 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 100 nmol/L, SL = 2.0 μm, temperature = 24°C). When sustained arrhythmias were induced with the BDM jet, we stopped the regional application of the BDM jet and measured the force, membrane potential, and regional [Ca2+]i (n = 6).

Second, to investigate the effect of non-uniform muscle contraction created by the BDM jet on the frequency of triggered arrhythmias, [Ca2+]o was increased stepwise (step: 0.5 mmol/L) in the presence of 200 nmol/L isoproterenol until sustained arrhythmias were induced by trains of 300 ms electrical stimuli ([Ca2+]o = 2.5 ± 0.5 mmol/L, temperature = 24°C). Changes in the initial muscle length (10% stretch or 5% release) were used to vary the force of contraction at a given Ca2+ concentration. 36, 37 These experiments were done in the presence and the absence of 100 μmol/L streptomycin,38, 39 a stretch-activated channel blocker. Stretch of the entire muscle increases the force of contraction in the non-paralyzed region by the Frank-Starling effect. This causes greater phasic deformation in the paralyzed region, which causes greater dissociation of Ca2+ from the myofilaments30 and more inward current.31 A reduction in initial fiber length would have the opposite effect. Additionally, the affinity of the myofilaments for Ca2+ was increased by 30 μmol/L SCH00013,40, 41 a novel Ca2+ sensitizer for myofilaments (see Supplemental Methods and Figures in the Online Supplemental Material).

Finally, sustained arrhythmias were still observed by trains of 300 ms electrical stimuli when the temperature was increased to 35°C in the trabeculae.42

Statistics

All measurements were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer for multiple comparisons, a paired t-test for two-group comparisons, and Pearson's correlation coefficient test for the linear regression analysis when the data were normally distributed. The Friedman test was used only to analyze the effect of SCH00013 on the cycle lengths of arrhythmias because the data were not normally distributed. These analyses were performed using software for statistical analysis (Ekuseru-Toukei 2008, Social Survey Research Information Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Values of P < 0.01 were considered to be significant.

The authors had full access to and take full responsibility for the integrity of the data. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Results

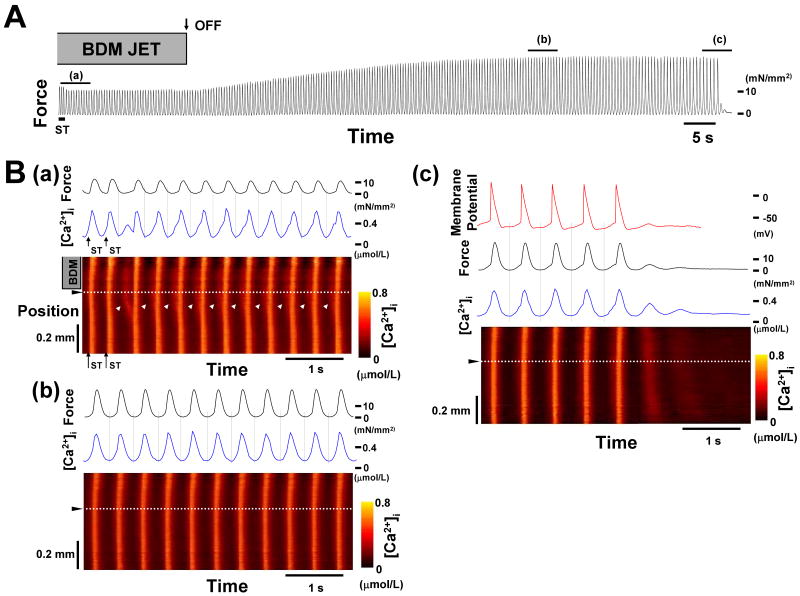

Sustained arrhythmias were induced in 9 out of 15 trabeculae with the regional application of a 20 mmol/L BDM jet and 5 out of 8 trabeculae with a 20 μmol/L blebbistatin jet. The longest stimulus interval which induced sustained arrhythmias was 420 ± 16 ms with the BDM jet and 394 ± 34 ms with the blebbistatin jet. In contrast, no sustained arrhythmias were induced by stimulus intervals of 200, 300 and 400 ms without the BDM jet. To further investigate the role of non-uniformity of muscle contraction in the sustainability of triggered arrhythmias, the BDM jet was stopped during sustained arrhythmias (Figure 1A). The stoppage of the regional application of BDM jet enhanced the developed forces by 97 ± 14% (n = 6, p < 0.01), slowed the cycle of sustained arrhythmias from 396 ± 22 ms to 431 ± 23 ms (n = 6, p < 0.01), and finally resulted in the arrest of arrhythmias. Figure 1B shows the regional changes in [Ca2+]i before and after the stoppage of the regional application of the BDM jet. Before the stoppage of the BDM jet, Ca2+ surged within the BZ between the contracting and stretched region produced by the BDM jet during the relaxation phase of muscle contraction and preceded synchronous increases in [Ca2+]i with twitch contractions (Figure 1B(a)). In contrast, with the stoppage of the BDM jet, the Ca2+ surges within the BZ became unclear, and the sustained arrhythmias were decelerated (Figure 1B(b)), resulting in the arrest of the sustained arrhythmias (Figure 1B(c)). This pattern was observed in all 6 trabeculae, suggesting that these Ca2+ surges within the BZ play an important role in the sustainability of triggered arrhythmias.

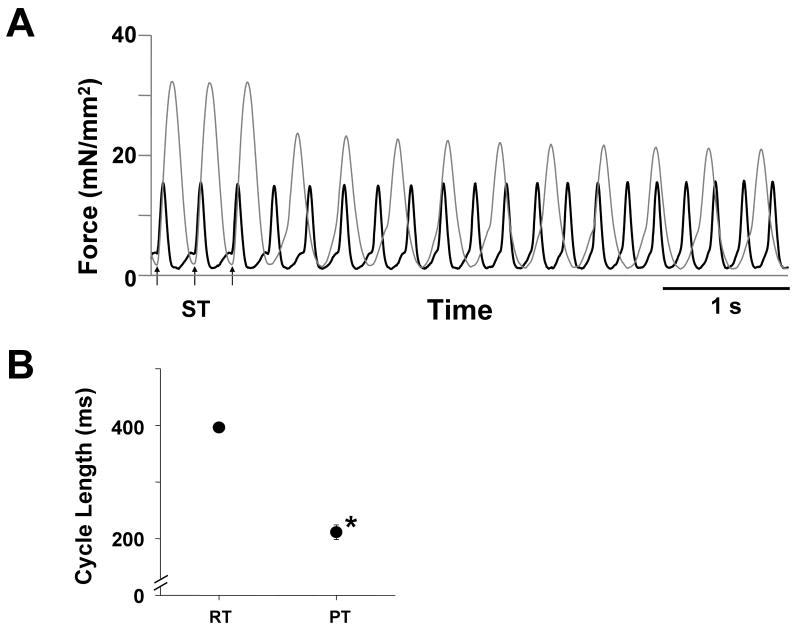

Figure 1. Effect of regional application of a BDM jet on a sustained arrhythmia.

A. Continuous chart recording of force during a sustained arrhythmia induced by electrical stimulation (ST, 300 ms stimulus interval). Arrow with OFF indicates when the BDM jet was turned OFF. After the jet was turned OFF, the contractions became larger and slower, and eventually the arrhythmia was arrested. ([Ca2+]o = 1.0 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 100 nmol/L, temperature = 23.9°C, Exp.090114)

B. Expanded recordings of force (black lines), membrane potential (red line), [Ca2+]i at the position indicated by the dotted white lines in the lower panels (blue lines), and regional changes in [Ca2+]i (lower panels) during the periods indicated by lines of (a), (b), and (c) within Panel A. During period (a), white arrowheads in the lower panel indicate Ca2+ surges within the border zone between the contracting and stretched region produced by the BDM jet. Note that the Ca2+ surges started to emerge during the relaxation phase of muscle contractions and preceded the synchronous increases in [Ca2+]i. The cycle lengths were 396-400 ms. During period (b), Ca2+ surges were unclear and [Ca2+]i started to increase after the relaxation phase of muscle contractions. The cycle lengths decreased to 427-436 ms. During period (c), the arrhythmia was further decelerated and finally arrested, followed by Ca2+ waves arising from one end of the trabecula. Arrows with ST indicate the moments of electrical stimulation.

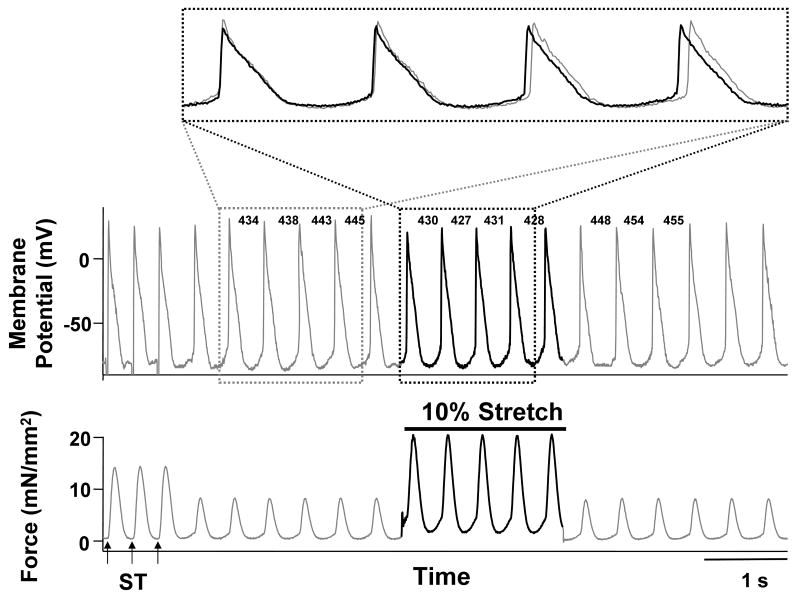

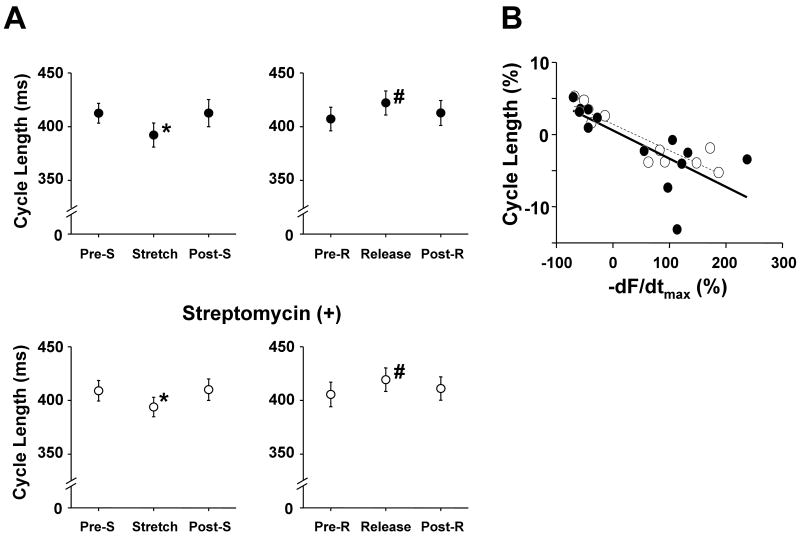

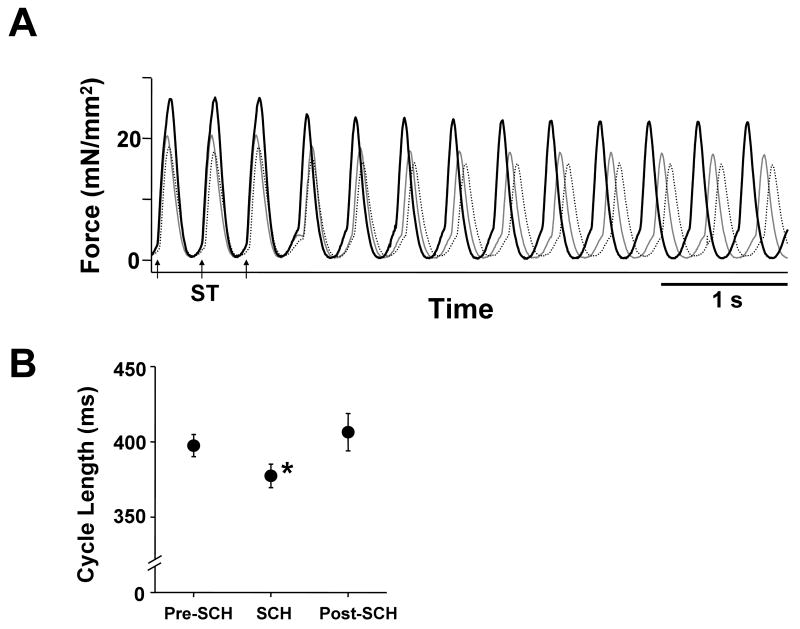

At 2.5 ± 0.5 mmol/L [Ca2+]o and 200 nmol/L isoproterenol, sustained arrhythmias were induced in all trabeculae with the regional application of a 20 mmol/L BDM jet. To investigate the role of Ca2+ dissociated from myofilaments, which has been reported to be responsible for the Ca2+ surge,29-31 in the frequency of triggered arrhythmias, the affinity of myofilaments for Ca2+ was altered by changing muscle length transiently or by adding SCH00013, a Ca2+ sensitizer for myofilaments. Figure 2 shows a representative effect of a transient 10% stretch of trabeculae on the frequency of triggered arrhythmias. Note that the cycle length of the arrhythmia was reduced during muscle stretching. As shown in Figure 3A, 10% stretch of muscle length significantly accelerated sustained arrhythmias, and 5% release of muscle length significantly decelerated sustained arrhythmias. Importantly, the stretch induced changes in cycle length were not suppressed in the presence of 100 μmol/L streptomycin, a stretch-activated channel blocker. Such changes in cycle length shown in Figure 3A were reproducible in all the preparations. Furthermore, the change of the maximum rate of muscle relaxation was inversely correlated with those of cycle length in the presence and the absence of 100 μmol/L streptomycin (Figure 3B). The cycle of the sustained arrhythmia was also significantly accelerated in the presence of the calcium sensitizer SCH00013 (30 μmol/L; Figure 4). This acceleration of arrhythmias was similar in all the preparations.

Figure 2.

Representative tracings of membrane potential and force during sustained arrhythmias with the regional application of a BDM jet when 10% stretch of cardiac muscle was added for 2 seconds. The upper panel shows membrane potential and lower panel shows force during the last three electrical stimuli in 300 ms interval (arrows with ST) and the subsequent sustained arrhythmia. During the arrhythmia, a stretch pulse was added for 2 seconds (thick lines). The numbers between action potentials in the upper panel indicate the cycle lengths between the action potentials. Expanded tracings of membrane potential show action potentials before (thin line) and during the stretch pulse (thick line). Note that a 10% stretch pulse transiently accelerated the arrhythmia. ([Ca2+]o = 1.0 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 200 nmol/L, temperature = 23.9°C, Exp.080924)

Figure 3.

A. Effect of a transient 10% stretch or 5% release of cardiac muscle on cycle lengths of sustained arrhythmias with the regional application of a BDM jet. Sustained arrhythmias were induced by trains of 300 ms electrical stimuli. The cycle lengths were measured before, during, and after the transient stretch or release of muscle for 2 seconds in the absence (upper panels, n = 10) and the presence of 100 μmol/L streptomycin, a stretch-activated channel blocker (lower panels, n = 10). Streptomycin did not suppress the changes in the cycle lengths caused by the transient stretch or release. Pre-S, Stretch, and Post-S indicate the measurements before the stretch, during the 10% stretch, and after the stretch, respectively. Pre-R, Release, and Post-R indicate the measurements before the release, during the 5% release, and after the release, respectively. * P < 0.01 vs Pre-S and Post-S, # P < 0.01 vs Pre-R and Post-R (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA with Tukey-Kramer). ([Ca2+]o = 2.5 ± 0.5 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 200 nmol/L, temperature = 24.1 ± 0.2°C)

B. Relationships between changes of the maximum rate of force relaxation (-dF/dtmax) and those of the cycle lengths caused by the transient stretch or release of muscle without (filled circles, n = 14, r = 0.74) and with 100 μmol/L streptomycin (open circles, n = 10, r = 0.89). They were both linearly correlated (p < 0.01) (Pearson's correlation coefficient test).

Figure 4. Effect of 30 μmol/L SCH00013 on the cycle lengths of sustained arrhythmias with the regional application of a BDM jet.

A. Continuous chart recordings of force during sustained arrhythmias before the addition (thin line), in the presence (thick line), and after the washout of SCH00013 (dotted line). Sustained arrhythmias were induced by trains of 300 ms electrical stimuli (arrows with ST). ([Ca2+]o = 2.0 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 200 nmol/L, temperature = 24.0°C, Exp.081127)

B. Effect of 30 μmol/L SCH00013 on the cycle lengths of sustained arrhythmias (n = 10). Pre-SCH indicates the measurements before the addition of SCH00013, SCH indicates the measurements 15 minutes after the addition of SCH00013, and Post-SCH indicates the measurements 15 minutes after the washout of SCH00013. Cycle lengths were significantly shorter in the presence of SCH00013. * P < 0.01 vs Pre-SCH and Post-SCH (Freedman test). ([Ca2+]o = 2.3 ± 0.2 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 200 nmol/L, temperature = 24.1 ± 0.2°C)

When the temperature was increased from 24°C to 35°C in 5 trabeculae, the cycle lengths of the sustained arrhythmias decreased to a value shorter than the stimulus interval needed for induction in all preparations (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effect of temperature on the cycle lengths of sustained arrhythmias with the regional application of a BDM jet.

A. Continuous chart recordings of force during sustained arrhythmias at 23.9°C (gray line) and 35.2°C (black line). Sustained arrhythmias were induced by trains of 300 ms electrical stimuli (arrows with ST). ([Ca2+]o = 3.0 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 200 nmol/L, Exp.091125)

B. Effect of temperature on the cycle lengths of sustained arrhythmias (n = 5). When the temperature was increased from RT (room temperature, 24.4 ± 0.2°C) to PT (physiological temperature, 35.2 ± 0.2°C), the cycle lengths decreased from 396 ± 8 ms to 211 ± 13 ms. * P < 0.01 vs RT (paired t-test). ([Ca2+]o = 3.2 ± 0.6 mmol/L, isoproterenol = 200 nmol/L)

Discussion

The present study characterized the effect of non-uniform muscle contraction on the sustainability and frequency of triggered arrhythmias in intact rat trabeculae. To the best of our knowledge, it shows for the first time that non-uniform muscle contraction is one of the determinants of the sustainability and frequency of triggered arrhythmias caused by the surge of Ca2+ dissociated from the myofilaments within the BZ during the muscle relaxation.

Effect on sustainability of triggered arrhythmias

It has been reported that plasma norepinephrine concentration is elevated in diseased hearts43 and can be a predictor of sudden death.44 Thus, in the present study we used isoproterenol45 to induce triggered arrhythmias in a non-uniform contraction model of rat hearts.29, 30

Concerning the mechanism of triggered arrhythmias, it has been shown that spontaneous Ca2+ release from the SR causes DADs, leading to triggered action potentials,46, 47 which contribute to the next cycle of spontaneous Ca2+ release through a process including the CICR from the SR and the following Ca2+ reuptake into the SR.31, 48 Interestingly, in the present study with conditions of 1 mmol/L [Ca2+]o and 100 nmol/L isoproterenol, sustained arrhythmias occurred only upon the regional application of a BDM or blebbistatin jet. Termination of the BDM jet decelerated the arrhythmias, eventually resulting in their arrest (Figure 1A), suggesting that non-uniform muscle contraction plays an important role in the sustainability of triggered arrhythmias. Also, the observations that Ca2+ surges within the BZ preceded synchronous increases in [Ca2+]i during sustained arrhythmias and that the disappearance of Ca2+ surges after the stoppage of the BDM jet resulted in the arrest of sustained arrhythmias (Figure 1B) suggest that Ca2+ surges contribute to the sustainability of triggered arrhythmias. Furthermore, as previously reported, we know that these Ca2+ surges are derived from the Ca2+ dissociated from myofilaments within the BZ during the relaxation phase,29, 30 initiate Ca2+ waves from the BZ by CICR from the SR,29, 32 and enhance DADs.30, 31 Taken together, our results suggest that non-uniform muscle contraction with a BDM or blebbistatin jet dissociates Ca2+ from myofilaments within the BZ with the emergence of Ca2+ surges, increases Ca2+ release from the SR, which in turn enhances the amplitude of a DAD sufficiently to trigger an action potential, and thus sustains the triggered rhythms. It is generally accepted that mechanisms underlying arrhythmias in diseased hearts49 are secondary to repolarization,50 conduction,51 and/or [Ca2+]i cycling abnormalities7. In fact, the present study suggests for the first time that contraction abnormalities are also a mechanism underlying arrhythmias in diseased hearts.

Effect on frequency of triggered arrhythmias

Reports have been inconsistent as to how the amplitude of a DAD affects the frequency of triggered arrhythmia, that is, larger DADs increased the frequency in one report20 and had no effect in another.19 The present study suggests that the amount of Ca2+ dissociated from the myofilaments, which determines the amplitude of DADs in this experimental model,30, 31 affects the frequency of arrhythmias. Four observations support this conclusion. First, the disappearance of Ca2+ surges after the stoppage of the BDM jet decelerated the cycle of arrhythmias (Figure 1). Second, the transient lengthening of cardiac muscle accelerated the arrhythmias, while the shortening of cardiac muscle inversely decelerated the arrhythmias. These events occurred even in the presence of streptomycin, at a concentration that is known to block stretch-activated channels (Figures 2 and 3A).38, 39 In addition, we have previously reported that a 10% stretch of cardiac muscle dissociates more Ca2+ from the myofilaments with the emergence of larger Ca2+ surges within the BZ and enhances aftercontractions and thus the initiator of these changes.30 Third, changes in the maximum rate of muscle relaxation were inversely correlated with those of cycle length of sustained arrhythmias (Figure 3B), suggesting that the velocity of sarcomere shortening within the BZ during the relaxation phase may affect the frequency of arrhythmias due to changes in the Ca2+ dissociated from myofilaments.36, 37 Fourth, 30 μmol/L SCH00013, a novel Ca2+ sensitizer for myofilaments,40, 41 accelerated the arrhythmias (Figure 4), presumably as a result of more Ca2+ dissociated from myofilaments during the muscle relaxation. Thus, we suggest that the increased force of contraction produced by stretching the cardiac muscle or by adding a myofilament Ca2+ sensitizer causes dissociation of more Ca2+ from myofilaments in the paralyzed region during diastole, giving rise to larger Ca2+ surges.30 Such surges then go on to increase Ca2+ release from the SR, enhance the amplitude of the DAD sufficiently to reach an action potential threshold, and accelerate the triggered arrhythmia. Because the frequency of the arrhythmias became sufficiently high at physiological temperature (Figure 5), these results may explain why high-frequency arrhythmias occur more frequently in failing hearts, which in many cases are characterized by non-uniform muscle contraction,21, 22 an elevation of plasma norepinephrine concentration,42 and an increase in wall stress due to dilation of the left ventricle.52 Furthermore, in a failing heart with dyssynchronous contraction,28 non-uniform muscle contraction may play a role in arrhythmias as in this experimental model. It is well known that in failing hearts, impaired muscle is widely distributed throughout the heart, causing significant opposing regions of normal and delayed contraction. At the interface of two such areas we can imagine that the impaired muscle can be stretched by contractions of the more viable neighboring muscle.

Limitations of the study

It is important to detect how the Ca2+ within the BZ surges during non-uniform muscle contraction. However, here we have not reported Ca2+ surges at the subcellular level because the movement of trabeculae during muscle contractions makes measurement of the Ca2+ surges using confocal microscopy difficult. Confocal microscopy has been used to detect intracellular Ca2+ mainly under the resting conditions in isolated myocytes53 or trabeculae54 and after the cardiac arrest caused by BDM in whole hearts.55

Conclusion

Non-uniform muscle contraction sustains and accelerates triggered arrhythmias due to the greater amount of Ca2+ dissociated from the myofilaments within the BZ during the relaxation phase. This increases the likelihood of life-threatening arrhythmias in non-uniform diseased hearts.

Clinical Perspective.

In failing hearts, wall stress increases due to dilation of the left ventricle. Because the arrangement of muscle fascicles in the cardiac wall transmits force longitudinally, this increase in wall stress aggravates the regional difference in contractile strength around impaired muscle, which is widely distributed throughout failing hearts. Regional differences in contractile strength may cause paradoxical stretching and shortening of the impaired muscle by contractions of the neighboring more viable muscle. Results of the present study suggest that surges of Ca2+ occur within the border zone between the contracting and stretched regions during the muscle relaxation and increase the duration and the ventricular rate of triggered arrhythmias. Consequently, the presence of non-uniformity of muscle contraction may explain, at least in part, why life-threatening arrhythmias are prone to occur in failing hearts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (M. Miura, No. 20590205), a grant from Mochida Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and NIH HL 58860.

Footnotes

Disclosures: All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boyden PA, Barbhaiya C, Lee T, ter Keurs HEDJ. Nonuniform Ca2+ transients in arrhythmogenic Purkinje cells that survive in the infarcted canine heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:681–693. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00725-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson KP, Walker R, Urie P, Ershler PR, Lux RL, Karwandee SV. Myocardial electrical propagation in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:122–140. doi: 10.1172/JCI116540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akar FG, Rosenbaum DS. Transmural electrophysiological heterogeneities underlying arrhythmogenesis in heart failure. Circ Res. 2003;93:638–645. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000092248.59479.AE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vermeulen JT, McGuire MA, Opthof T, Coronel R, de Bakker JM, Klöpping C, Janse MJ. Triggered activity and automaticity in ventricular trabeculae of failing human and rabbit hearts. Cardiovasc Res. 1994;28:1547–1554. doi: 10.1093/cvr/28.10.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnar DO, Xing D, Martins JB. Overdrive pacing of early ischemic ventricular tachycardia: evidence for both reentry and triggered activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H1124–H1130. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01162.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vos MA, de Groot SHM, Verduyn SC, van der Zande J, Leunissen HDM, Cleutjens JPM, van Bilsen M, Daemen MJAP, Schreuder JJ, Allessie MA, Wellens HJJ. Enhanced susceptibility for acquired torsade de pointes arrhythmias in the dog with chronic, complete AV block is related to cardiac hypertrophy and electrical remodeling. Circulation. 1998;98:1125–1135. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.11.1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bers DM, Eisner DA, Valdivia HH. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ and heart failure. Roles of diastolic leak and Ca2+ transport. Circ Res. 2003;93:487–490. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000091871.54907.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Packer M. Sudden unexpected death in patients with congestive heart failure: a second frontier. Circulation. 1985;72:681–685. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.72.4.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myerburg RJ, Interian A, Mitrani RM, Kessler KM, Castellanos A. Frequency of sudden cardiac death and profiles of risk. Am J Cardiol. 1997;80:10F–19F. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)00477-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Priori SG, Mantica M, Schwartz PJ. Delayed afterdepolarizations elicited in vivo by left stellate ganglion stimulation. Circulation. 1988;78:178–185. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.1.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimizu W, Antzelevitch C. Cellular basis for the ECG features of the LQT1 form of the long-QT syndrome: effects of beta-adrenergic agonists and antagonists and sodium channel blockers on transmural dispersion of repolarization and torsade de pointes. Circulation. 1998;98:2314–2322. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.21.2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pogwizd SM, McKenzie JP, Cain ME. Mechanisms underlying spontaneous and induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1998;98:2404–2414. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.22.2404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janse MJ, Vermeulen JT, Opthof T, Coronel R, Wilms-Schopman FJ, Rademaker HM, Baartscheer A, Dekker LR. Arrhythmogenesis in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:496–499. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.00496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Verkerk AO, Veldkamp MW, Baartscheer A, Schumacher CA, Klöpping C, van Ginneken AC, Ravesloot JH. Ionic mechanism of delayed afterdepolarizations in ventricular cells isolated from human end-stage failing hearts. Circulation. 2001;104:2728–2733. doi: 10.1161/hc4701.099577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu N, Rizzi N, Boveri L, Priori SG. Ryanodine receptor and calsequestrin in arrhythmogenesis: What we have learnt from genetic diseases and transgenic mice. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buxton AE, Waxman HL, Marchlinski FE, Untereker WJ, Waspe LE, Josephson ME. Role of triple extrastimuli during electrophysiologic study of patients with documented sustained ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Circulation. 1984;69:532–540. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.69.3.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevenson WG, Brugada P, Waldecker B, Zehender M, Wellens HJJ. Clinical, angiographic, and electrophysiologic findings in patients with aborted sudden death as compared with patients with sustained ventricular tachycardia after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1985;71:1146–1152. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.6.1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pogwizd SM. Cycle length dynamics during ventricular tachycardia in the infarcted heart. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2000;11:545–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2000.tb00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charpentier F, Baudet S, Le Marec H. Triggered activity as a possible mechanism for arrhythmias in ventricular hypertrophy. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1991;14:1735–1741. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1991.tb02756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Groot SHM, Vos MA, Gorgels APM, Leunissen JDM, Hermans M, Dohmen LRB, Wellens HJJ. The dynamic behavior of the diastolic slope of monophasic action potential can be related to the occurrence and maintenance of delayed afterdepolarization dependent arrhythmias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1999;22:49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.1999.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siogas K, Pappas S, Graekas G, Goudevenos J, Liapi G, Sideris DA. Segmental wall motion abnormalities alter vulnerability to ventricular ectopic beats associated with acute increases in aortic pressure in patients with underlying coronary artery disease. Heart. 1998;79:268–273. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.3.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Young AA, Dokos S, Powell KA, Sturm B, McCulloch AD, Starling RC, McCarthy PM, White RD. Regional heterogeneity of function in nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:308–318. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00248-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smalling RW, Ekas RD, Felli PR, Binion L, Desmond J. Reciprocal functional interaction of adjacent myocardial segments during regional ischemia: an intraventricular loading phenomenon affecting apparent regional contractile function in the intact heart. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;7:1335–1346. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(86)80155-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian YW, Clusin WT, Lin SF, Han J, Sung RJ. Spatial heterogeneity of calcium transient alternans during the early phase of myocardial ischemia in the blood-perfused rabbit heart. Circulation. 2001;104:2082–2087. doi: 10.1161/hc4201.097136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beau SL, Tolley TK, Saffitz JE. Heterogeneous transmural distribution of beta-adrenergic receptor subtypes in failing human hearts. Circulation. 1993;88:2501–2509. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen LS, Zhou S, Fishbein MC, Chen PS. New perspectives on the role of autonomic nervous system in the genesis of arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2007;18:123–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2006.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spragg DD, Leclercq C, Loghmani M, Faris OP, Tunin RS, DiSilvestre D, McVeigh ER, Tomaselli GF, Kass DA. Regional alterations in protein expression in the dyssynchronous failing heart. Circulation. 2003;108:929–932. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000088782.99568.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cleland JG, Daubert JC, Erdmann E, Freemantle N, Gras D, Kappenberger L, Tavazzi L, Cardiac Resynchronization-Heart Failure (CARE-HF) Study Investigators The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1539–1549. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakayama Y, Miura M, Stuyvers BD, Boyden PA, ter Keurs HEDJ. Spatial nonuniformity of excitation-contraction coupling causes arrhythmogenic Ca2+ waves in rat cardiac muscle. Circ Res. 2005;96:1266–1273. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000172544.56818.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miura M, Wakayama Y, Endoh H, Nakano M, Sugai Y, Hirose M, ter Keurs HEDJ, Shimokawa H. Spatial non-uniformity of excitation-contraction coupling can enhance arrhythmogenic-delayed afterdepolarizations in rat cardiac muscle. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;80:55–61. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.ter Keurs HEDJ, Boyden PA. Calcium and arrhythmogenesis. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:457–506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miura M, Boyden PA, ter Keurs HEDJ. Ca2+ waves during triggered propagated contractions in intact trabeculae. Determinants of the velocity of propagation. Circ Res. 1999;84:1459–1468. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.12.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Straight AF, Cheung A, Limouze J, Chen I, Westwood NJ, Sellers JR, Mitchison TJ. Dissecting temporal and spatial control of cytokinesis with a myosin II Inhibitor. Science. 2003;299:1743–1747. doi: 10.1126/science.1081412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farman GP, Tachampa K, Mateja R, Cazorla O, Lacampagne A, de Tombe PP. Blebbistatin: use as inhibitor of muscle contraction. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455:995–1005. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0375-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vos MA, Gorgels APM, Leunissen JDM, van Deursen RTAM, Wellens HJJ. Significance of the number of stimuli to initiate ouabain-induced arrhythmias in the intact heart. Circ Res. 1991;68:38–44. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Housmans PR, Lee NKM, Blinks JR. Active shortening retards the decline of the intracellular calcium transient in mammalian heart muscle. Science. 1983;221:159–161. doi: 10.1126/science.6857274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen DG, Kentish JC. Calcium concentration in the myoplasm of skinned ferret ventricular muscle following changes in muscle length. J Physiol. 1988;407:489–503. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamill OP, McBride DW., Jr The pharmacology of mechanogated membrane ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1996;48:231–252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Calaghan S, White E. Activation of Na+-H+ exchange and stretch-activated channels underlies the slow inotropic response to stretch in myocytes and muscle from the rat heart. J Physiol. 2004;559(1):205–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.069021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sugawara H, Endoh M. A novel cardiotonic agent SCH00013 acts as a Ca2+ sensitizer with no chronotropic activity in mammalian cardiac muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;287:214–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tadano N, Morimoto S, Yoshimura A, Miura M, Yoshioka K, Sakato M, Ohtsuki I, Miwa Y, Takahashi-Yanaga F, Sasaguri T. SCH00013, a novel Ca2+ sensitizer with positive inotropic and no chronotropic action in heart failure. J Pharmacol Sci. 2005;97:53–60. doi: 10.1254/jphs.fp0040654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stuyvers BD, McCulloch AD, Guo J, Duff HJ, ter Keurs HEDJ. Effect of stimulation rate, sarcomere length and Ca2+ on force generation by mouse cardiac muscle. J Physiol. 2002;544:817–830. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Braunwald E. Congestive heart failure: a half century perspective. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:825–836. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohn JN, Levine TB, Olivari MT, Garberg V, Lura D, Francis GS, Simon AB, Rector T. Plasma norepinephrine as a guide to prognosis in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:819–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198409273111303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wit AL, Cranefield PF. Triggered and automatic activity in the canine coronary sinus. Circ Res. 1977;41:435–445. doi: 10.1161/01.res.41.4.434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferrier GR. The effects of tension on acetylstrophanthidin-induced transient depolarizations and aftercontractions in canine myocardial and Purkinje tissues. Circ Res. 1976;38:156–162. doi: 10.1161/01.res.38.3.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clusin WT, Buchbinder M, Harrison DC. Calcium overload, “injury” current, and early ischaemic cardiac arrhythmias - A direct connection. Lancet. 1983;321:272–274. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91688-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature. 2002;415:198–205. doi: 10.1038/415198a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin H, Lyon AR, Akar FG. Arrhythmia mechanisms in the failing heart. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2008;31:1048–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8159.2008.01134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O'Rourke B, Kass DA, Tomaselli GF, Kääb S, Tunin R, Marbán E. Mechanisms of altered excitation-contraction coupling in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure, I: experimental studies. Circ Res. 1999;84:562–570. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.5.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laurita KR, Chuck ET, Yang T, Dong WQ, Kuryshev YA, Brittenham GM, Rosenbaum DS, Brown AM. Optical mapping reveals conduction slowing and impulse block in iron-overload cardiomyopathy. J Lab Clin Med. 2003;142:83–89. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2143(03)00060-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayashida W, Kumada T, Nohara R, Tanio H, Kambayashi M, Ishikawa N, Nakamura Y, Himura Y, Kawai C. Left ventricular regional wall stress in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1990;82:2075–2083. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.6.2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cheng H, Lederer WJ, Cannell MB. Calcium sparks: elementary events underlying excitation-contraction coupling in heart muscle. Science. 1993;262:740–744. doi: 10.1126/science.8235594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wier WG, ter Keurs HEDJ, Marban E, Gao WD, Balke CW. Ca2+ ‘sparks’ and waves in intact ventricular muscle resolved by confocal imaging. Circ Res. 1997;81:462–469. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kaneko T, Tanaka H, Oyamada M, Kawata S, Takamatsu T. Three distinct types of Ca2+ waves in Langendorff-perfused rat heart revealed by real-time confocal microscopy. Circ Res. 2000;86:1093–1099. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.10.1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.