Abstract

EB1 is a microtubule plus-end tracking protein that plays a central role in the regulation of microtubule (MT) dynamics. GFP-tagged EB1 constructs are commonly used to study EB1 itself and also as markers of dynamic MT plus ends. To properly interpret these studies, it is important to understand the impact of tags on the behavior of EB1 and other proteins in vivo. To address this problem and improve understanding of EB1 function, we surveyed the localization of expressed EB1 fragments and investigated whether GFP tags alter these localizations. We found that neither N-terminal nor C-terminal tags are benign: tagged EB1 and EB1 fragments generally behave differently from their untagged counterparts. N-terminal tags significantly compromise the ability of expressed EB1 proteins to bind MTs and/or track MT plus ends, although they leave some MT-binding ability intact. C-terminally tagged EB1 constructs have localizations similar to the untagged constructs, initially suggesting that they are benign. However, most constructs tagged at either end cause CLIP-170 to disappear from MT plus ends. This effect is opposite to that of untagged full-length EB1, which recruits CLIP-170 to MTs. These observations demonstrate that although EB1-GFP can be a powerful tool for studying microtubule dynamics, it should be used carefully because it may alter the system that it is being used to study. In addition, some untagged fragments had unexpected localizations. In particular, an EB1 construct lacking the coiled-coil tracks MT plus ends, though weakly, providing evidence against the idea that EB1 +TIP behavior requires dimerization.

INTRODUCTION

Microtubules (MTs) are highly dynamic and polar structures that are involved in many important cellular processes including mitosis, cargo trafficking, and subcellular organization. MTs are usually anchored at the minus end, while the plus end undergoes phases of growth and shortening known as dynamic instability (Desai and Mitchison 1997). It is becoming apparent that the growing MT plus end is an attachment site for many proteins. A group of proteins that dynamically localize to the growing plus ends are collectively known as MT plus-end tracking proteins or +TIPs (Akhmanova and Hoogenraad 2005; Akhmanova and Steinmetz 2008; Carvalho et al. 2003; Howard and Hyman 2003; Schuyler and Pellman 2001). +TIPs often serve to modulate MT dynamics or act as mediators between MTs and other proteins or membranes.

One +TIP, End Binding protein 1 (EB1), is particularly well-conserved and interacts with a large fraction of other +TIPs (Lansbergen and Akhmanova 2006; Morrison 2007; Vaughan 2005). EB1 was first discovered as an APC binding partner (Su et al. 1995), but it also binds to other proteins including CLIP-170 (Goodson et al. 2003; Komarova et al. 2005), p150 (Askham et al. 2002; Hayashi et al. 2005; Honnappa et al. 2006), CLASPs (Mimori-Kiyosue et al. 2005), and spectraplakins (Bu and Su 2003; Kodama et al. 2003). The sum of these observations suggests that EB1 is the core of a network of proteins found at the MT plus end (Komarova et al. 2005; Lansbergen and Akhmanova 2006; Morrison 2007; Vaughan 2005). EB1 has received a great deal of experimental attention because of its importance, but also because EB1 localization is a useful marker of dynamic MT plus ends. Endogenous EB1 detected by commercially available antibodies labels plus ends in fixed cells (Morrison et al. 1998). Exogenous EB1-GFP is a popular marker for the study of dynamic MT plus ends in living cells as analyzed by video microscopy (Ma et al. 2004; Mimori-Kiyosue et al. 2000; Salaycik et al. 2005; Stepanova et al. 2003; Yao et al. 2008; Goodson and Wadsworth 2005).

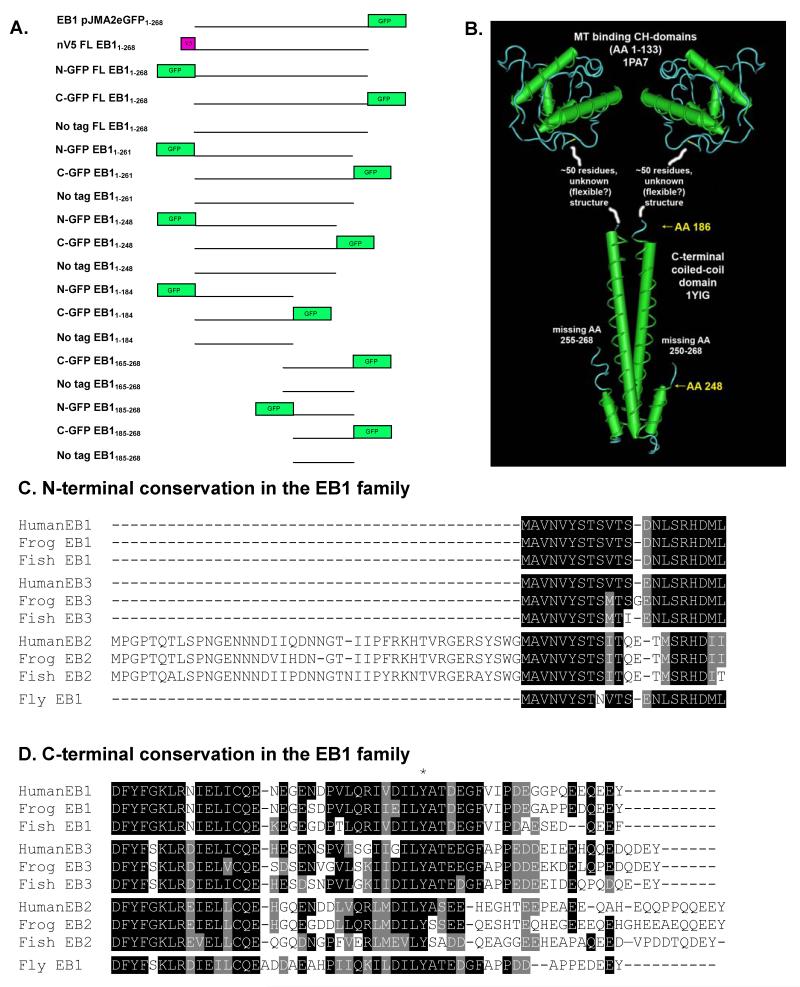

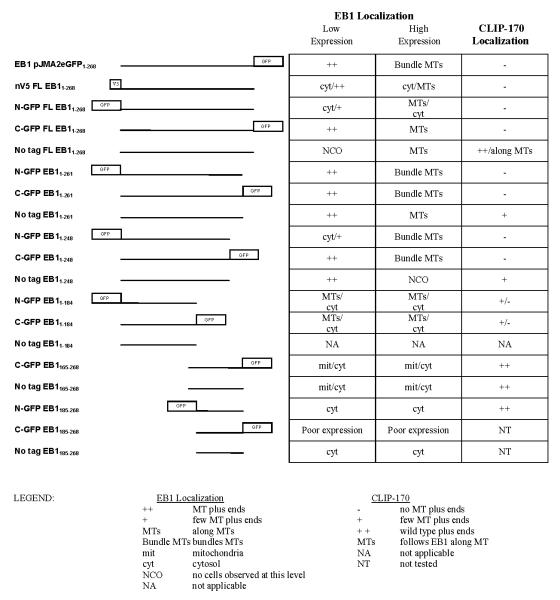

In an effort to study the dependence of the localization of EB1 on its different domains, we created a series of tagged and untagged EB1 deletion mutants; these constructs varied in the position of the tag (N-terminal, C-terminal, or none) and in the tag identity (GFP or V5) (Figure 1). We examined the localization of each expressed fragment in Cos-7 cells, and also assayed its effect on the MT network, the localization of CLIP-170, and (when possible) the endogenous EB1 protein. We find that in many cases tagged EB1 fragments behave differently from their untagged counterparts, and that N-terminal tags have effects distinct from C-terminal tags. In particular, N-terminal tags reduce the ability of the EB1 constructs to bind MTs, but both N- and C-terminally tagged EB1 constructs can interfere with the localization of endogenous CLIP-170, a protein implicated in the regulation of MT dynamics. These observations demonstrate that tagged constructs can give misleading results when they are used to examine the behavior and activity of EB1 and EB1 fragments. They also indicate that caution is warranted when using EB1-GFP as a tool for examining dynamic MT plus ends: under some conditions, this marker is not always benign.

Fig 1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Constructs

All EB1 constructs were cloned using directional TOPO cloning of the Gateway Cloning System (Invitrogen) from either prSETA EB1 or pJMA2eGFP EB1 (Askham et al. 2000; Morrison et al. 2002), both generous gifts of Ewan Morrison. Briefly, primers were designed to amplify bases 1-804, 1-783, 1-744, 1-552, 493-804, and 553-804. Forward primers include the bases CACC on the 5′ end to allow directional cloning into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector as described in the Gateway cloning manual. All deletion fragments were cloned into pDEST 47, pDEST 53, or pcDNA3.1/Nv5-DEST using LR Clonase. Unless otherwise noted, all data were acquired using EB1 constructs expressed from these Gateway vectors. The pDEST vectors introduce a significant linker between the protein and the tag (GFP or V5). Linker sequences for the pDEST vectors used are as follows:

pDEST 47- C-terminal GFP

KGGRADPAFLYKVVRSRM (18aa)

pDEST 53- N-terminal GFP

KSGSGPDQTSLYKKAGSAAAPFT (23aa)

pcDNA3.1/Nv5-DEST- N-terminal V5

ENLYFQGPDPSTNSADITSLYKKAGSAAAPFT (32aa)

Cell Culture and Cell Transfection

Cos-7 cells (ATCC) were grown on 100mm plates in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) with 10% FBS, 1% L-Glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin(pen/strep) at 37°C in 5% CO2. Reagents used in cell culture were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies via Fisher Scientific. Cells used for transfection were seeded on 10mm2 (20mm2 in live cell studies) coverslips in a 60mm plate and transfected using the CaPO4 method as previously described (Valetti et al. 1999). Transfected cells were incubated in 5% CO2, at 37°C for 20 to 24 hours. Transfections were stopped by washing 2 times with 1X PBS and adding back DMEM+pen/strep. Fixing and/or viewing of cells was done within 30 minutes of stopping the transfection.

Antibodies

Visualization of CLIP-170 was achieved using either affinity purified polyclonal α-55 (Pierre et al. 1992) or a combination of the monoclonal antibodies 4D3 and 2D6 (Pierre et al. 1992; Rickard and Kreis 1991). The monoclonal EB1 antibody was obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories (#610534) and used to visualize all untagged EB1 proteins, with one exception. The epitope for the EB1 antibody is reported to lie within amino acids 107-268 (BD Biosciences). We found that the antibody is able to recognize the fragment EB1185-268, but not EB11-184, in a western blot, indicating that the epitope is not present in the region between amino acids 107-184 (data not shown). For this reason, the untagged EB11-184 fragment was unable to be detected. Tubulin was visualized using the monoclonal 1A2 or the polyclonal T13 antibodies (Kreis, 1987). The anti-V5 antibody was purchased from Invitrogen (#R96025). Mitochondria were detected using Mitotracker (Molecular Probes #M7512.) The secondary antibodies Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes #s A-11008 and A-11029), Cy3 and Cy5 (Jackson Immunoresearch #s 111-165-144, 115165-146 and #s 715-175-1500, 711-175-1520 respectively) were used for immunofluorescence.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Cells were fixed using either MeOH or a combination of MeOH/paraformaldehyde (PFA) (Dujardin et al. 1998). MeOH fixed coverslips were submerged in ice-cold MeOH for 10 minutes, washed with 1X PBS 3 times, then stained with antibodies as described below. Fixation using the MeOH/PFA combination was performed by the following procedure: coverslips were placed in ice-cold MeOH for 10 minutes, washed one time in 1X PBS, then incubated 15 minutes in 3% PFA, followed by three 1X PBS washes, a 5 minute incubation in 50mM NH4Cl, and three 1X PBS washes. Antibody staining after either fixation consisted of incubation in primary antibody for 20 minutes, three 1X PBS washes, incubation in the secondary antibody for 20 minutes, and three more 1X PBS washes; coverslips were then mounted on slides using 5μL of Mowiol. Microscopy was performed on a Zeiss Axiovert S100TV inverted microscope using a 63X 1.4NA objective and a Princeton Instruments Micromax camera, or alternatively, a Nikon inverted microscope TE2000 using a 60X 1.4NA objective with or without a 1.5X optivar and Cascade 512B camera. Both microscopes were fitted with High Q filter sets from Chroma (Brattleboro, VT). Image acquisition was controlled by Metamorph software. To allow semi-quantitative comparison of expression level in cells in different photographs, all images were acquired under identical camera settings (exposure time, etc.). Expression levels were assessed by measuring the total integrated pixel intensity in each cell and categorizing the value as low, moderate (medium) or high. Images were further processed for presentation using Adobe Photoshop 7.0 (Adobe Systems, Mountain View, CA).

RESULTS

Construction of EB1 expression vectors

EB1 and EB1 fragments were cloned into a set of matched vectors (Gateway system) to allow their expression as N-terminally GFP-tagged, C-terminally GFP-tagged, or untagged constructs (Figure 1). We also cloned selected fragments into Gateway vectors allowing expression as V5-tagged constructs. These constructs were transiently transfected into Cos-7 cells, and their behavior (localization and effect on CLIP-170 in fixed cells) was analyzed as discussed below.

Localization of full-length EB1 depends on tag placement and identity

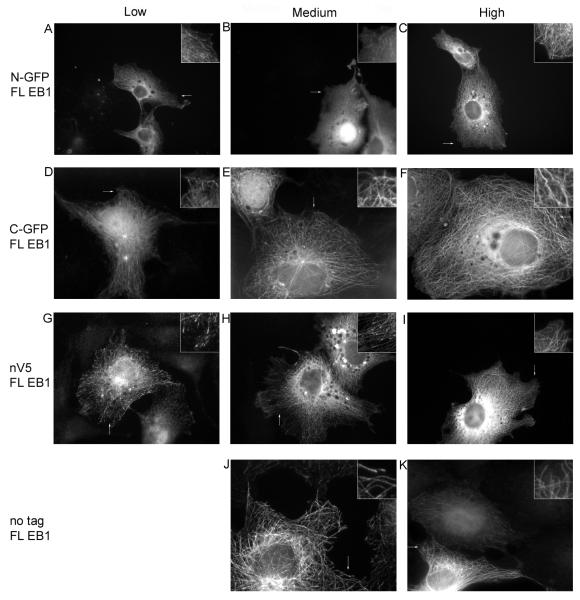

Consistent with previous observations (Askham et al. 2002; Bu and Su 2001; Mimori-Kiyosue et al. 2000; Wu et al. 2005), the C-terminally GFP tagged full-length (FL) EB1 localizes to MT tips when expressed at low levels and along MTs when expressed at moderate levels (Figure 2d, e and Supplementary Figure 1). At high levels of expression, C-terminally GFP tagged FL EB1 bundles MTs (Figure 2f and Supplementary Figure 1). The localization of untagged FL EB1 (visualized by antibodies) is similar to that of C-terminally GFP tagged FL EB1 (Figure 2j, k). In contrast, expressed N-terminally GFP tagged FL EB1 localizes predominantly to the cytosol, with some plus-end labeling observed at low and moderate expression levels (Figure 2a, b). This protein rarely binds along MTs, even at high expression levels (Figure 2c), and was never observed to bundle MTs

Figure 2.

To determine whether the relatively large size of GFP is a factor in the mislocalization of N-terminally GFP tagged FL EB1, we created a construct containing the small 14aa V5 tag at the N-terminus. This protein labels plus ends significantly better than N-GFP FL EB1 but still has more cytosolic localization than C-GFP FL EB1 or untagged EB1(Figure 2g-i). Moreover, it bundles MTs less than either C-GFP FL EB1 or untagged FL EB1 (Figure 2 and data not shown).

These observations initially suggest that placing a GFP tag at the EB1 C-terminus has little functional consequence. In contrast, N-terminal tags (both GFP and V5) reduce FL EB1-MT interactions without preventing them completely; the smaller V5 tag interferes with FL EB1 localization less than the larger GFP tag, but still behaves differently from the untagged protein. These conclusions are consistent with previous EB1 structure-function analyses: the MT binding site lies within the N-terminal calponin homology domain (Bu and Su 2003; Hayashi and Ikura 2003), and the N-terminus lies near amino acids implicated by mutagenesis in MT binding (Slep and Vale 2007).

The apparently normal behavior of C-GFP FL EB1 initially seems unremarkable given the distance of the tag from the MT binding site. However, this behavior becomes more surprising when one considers that the C-terminus of EB1 is involved in EB1 autoregulation and mediates interactions with CAP-GLY containing proteins such as CLIP-170 and p150 (Akhmanova and Steinmetz 2008; Askham et al. 2002; Berrueta et al. 1999; Hayashi et al. 2005; Komarova et al. 2005; Ligon et al. 2003; Ligon et al. 2006). Indeed, different C-GFP FL EB1 expression constructs do not necessarily behave identically: full-length C-terminally tagged EB1 expressed from a different vector (pJMA2eGFP instead of pDEST 47) exhibits more striking plus-end labeling and induces more MT bundling even when expressed at similar levels (Supplementary Figure 1 and data not shown). One significant difference between these vectors is that the linker between EB1 and the GFP is much shorter in pJMA2eGFP (< 5aa) than in the Gateway vector (18aa). Given that it is the N-terminal domain of EB1 that binds to MTs, it is not clear why this linker difference would affect MT binding. It is possible that the longer linker (and thus larger tag) interferes with the autoregulation process.

To investigate possible functional consequences of C-terminal GFP tags on EB1, we decided to examine the effects of expressed EB1 on CLIP-170. We chose to look at CLIP-170 because CLIP-170 is involved in the regulation of MT dynamics and depends on EB1 for its localization to MT tips (Bieling et al. 2008; Dixit et al. 2009; Komarova et al. 2005). More specifically, CLIP-170 interacts with the EB1 C-terminus, so GFP tags at the EB1 C-terminus might be expected to alter the interaction with CLIP-170 and thereby alter CLIP-170 function.

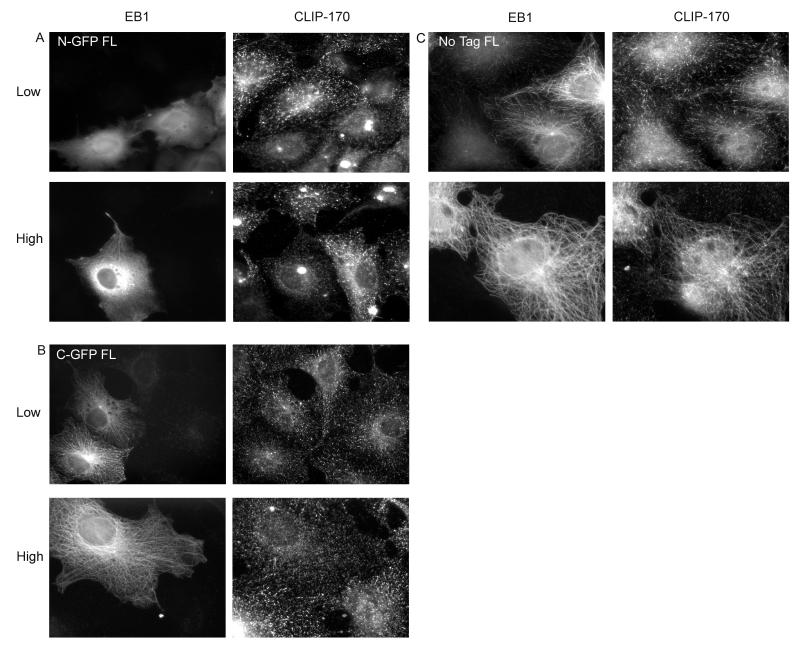

Effects of EB1 tags on the localization of CLIP-170

We transfected Cos-7 cells with tagged or untagged FL EB1 constructs, and examined both the EB1 and CLIP-170 localization. We found that expression of both N-terminally tagged and C-terminally tagged FL EB1 interferes with CLIP-170 localization to MT plus ends, but that the degree of interference depends on both the expression level and the location of the tag. Low levels of C-GFP FL EB1 did not appear to interfere with CLIP-170, but low-moderate levels (corresponding in these cells to EB1-GFP labeling that began to extend along MTs) caused CLIP-170 to disappear from MT plus ends (Figure 3b and data not shown). With N-GFP FL EB1, even low levels interfered with CLIP-170 localization (Figure 3a). In contrast, untagged FL EB1 had the opposite effect – it recruited CLIP-170 to MTs (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

The observation that C-terminally tagged EB1 displaces CLIP-170 from MT plus ends is consistent with evidence that CLIP-170 binds to the EB1 C-terminus and requires this interaction with EB1 for normal plus-end localization (Bieling et al. 2008; Dixit et al. 2009; Honnappa et al. 2005; Komarova et al. 2005; Mishima et al. 2007; Weisbrich et al. 2007): perhaps the tagged EB1 (which doesn’t bind CLIP-170 because of the C-GFP tag) displaces the endogenous EB1 and so prevents CLIP-170 binding to the MT tip. A plausible explanation for the effect of N-terminally tagged EB1 is that this protein, which binds poorly to MTs but contains the CLIP-170 binding site, sequesters CLIP-170 in the cytosol. To probe these issues and elucidate EB1 structure/function relationships, we investigated the behavior of EB1 fragments, both tagged and untagged. The conclusions are summarized in Table 1. Results for selected constructs are discussed below.

Table 1.

|

Behavior of EB1 fragments

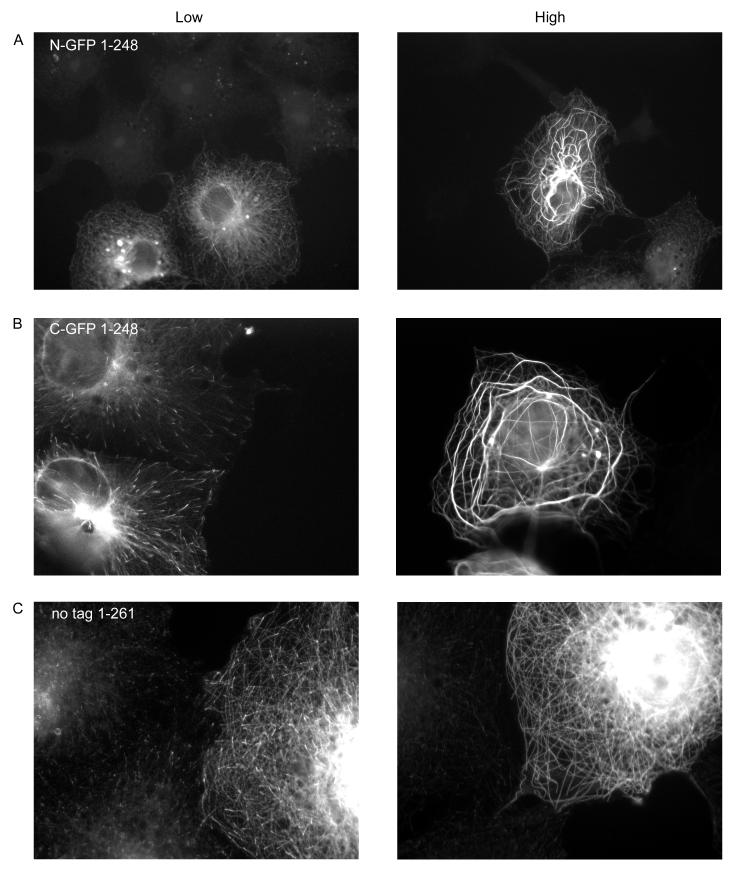

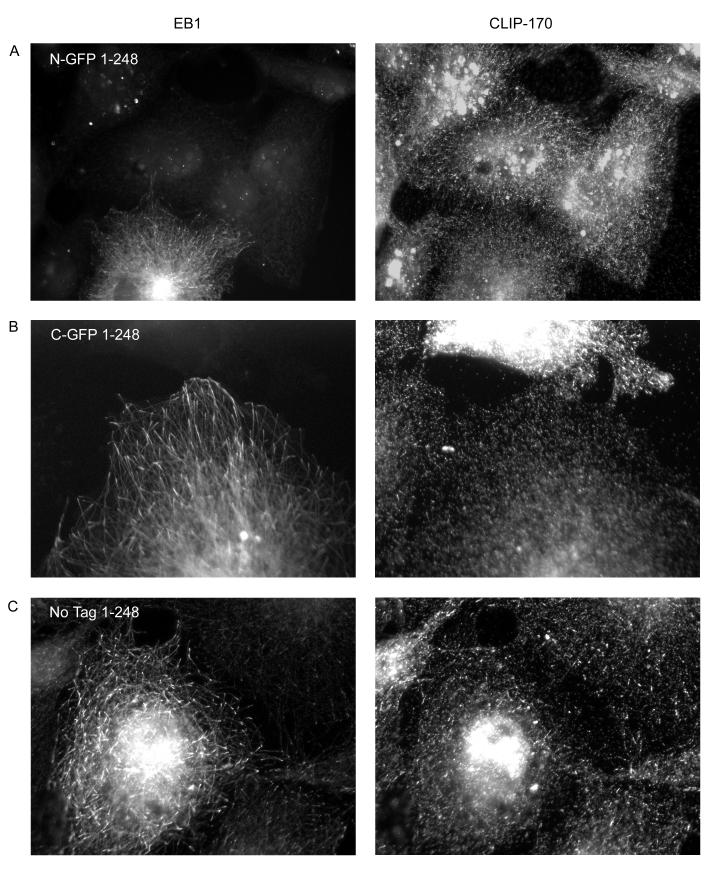

Localization of EB11-248 (mutant missing the C-terminal tail)

The C-terminal tail of EB1 is thought to be an autoinhibition domain (Hayashi et al. 2005; Manna et al. 2008). Therefore, proteins missing this domain are expected to be hyperactive. Consistent with this model, N-GFP-EB11-248 has strong MT bundling activity when expressed at moderate to high levels (Figure 4a, Supplementary Figure 2a). This is in contrast to full-length N-terminally tagged EB1, which was never observed to bundle MTs (Figure 2 and data not shown). C-GFP-EB11-248 behavior was similar to that of C-GFP FL EB1, except that the plus-end labeling in fixed cells is more easily observed (compare Figures 2 and 4). The localization of untagged EB11-248 appears indistinguishable from C-GFP-EB11-248 when expressed at lower levels (Figure 5c). We were not able to find cells expressing higher levels of untagged EB11-248, suggesting that this construct might affect cell viability. A slightly longer untagged construct, EB11-261, did express at both low and high levels and is intermediate in behavior between full-length and EB11-248 (Figure 4c). It is interesting to note that the bundles induced by the N-terminally tagged and C-terminally tagged EB11-248 proteins are often different in appearance: the N-terminally tagged EB11-248 tends to produce “curly” bundles that correspond to an unidentified subset of microtubules (Figure 4a and Supplementary Figure 2a), while the C-terminally tagged EB11-248 tends to produce more radial bundles (Figures 4b and Supplementary Figure 2b).

Figure 4.

Figure 5.

Effect of EB11-248 on CLIP-170

As noted above, removal of the last 20 amino acids renders EB1 incapable of binding to CLIP-170 (Komarova et al. 2005). Both N- and C-terminally tagged EB11-248 constructs cause a loss of CLIP-170 from MT plus ends even under conditions where GFP-EB1 is still predominantly localized to MT plus ends (Figure 5 a, b). Given that both N-and C- GFP EB11-248 can track MT plus ends, it is reasonable to propose that they interfere with CLIP-170 localization by displacing endogenous EB1 at MT tips. Surprisingly, untagged EB11-248 appears to have little or no effect on CLIP-170 (Figure 5c). However, it is difficult to make a definitive analysis because we observed no high level transfectants (see above), and it is difficult to distinguish cells expressing low levels of untagged EB11-248 from those expressing endogenous EB1 alone (the EB1 antibody recognizes both endogenous and expressed EB1, and endogenous EB1 expression can vary from cell to cell).

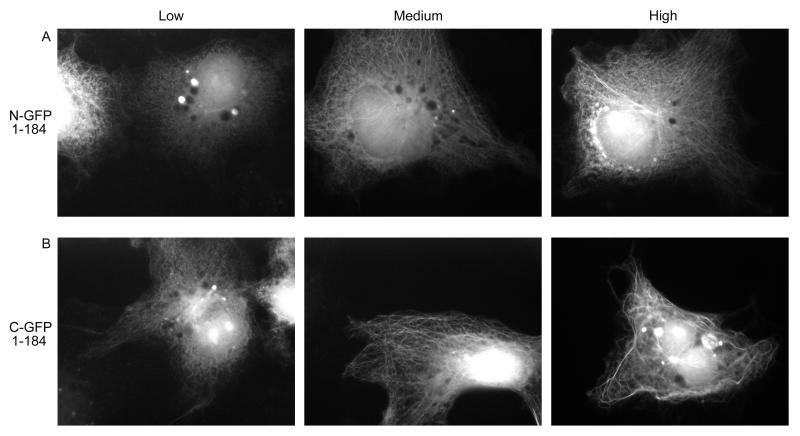

Behavior of EB11-184

This fragment consists only of the N-terminal MT binding domain and the linker region (Figure 1); it lacks both the CLIP-170-binding extreme C-terminal region and the conserved coiled-coil (responsible both for dimerizing the protein and for interacting with a number of proteins including adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)) (Honnappa et al. 2005; Slep et al. 2005). In fixed cells, N- and C-terminally tagged EB11-184 fragments localize along MTs with some bundling at moderate expression levels. Higher expression levels generally correlate with more MT bundling and some cytosolic staining (Figure 6). There is little obvious difference between N- and C-terminally tagged versions of this fragment in fixed cells, although N-GFP-EB11-184 has a greater tendency to exhibit cytosolic staining (data not shown). However, a striking difference was noted when the proteins were observed live: at low expression levels, N-GFP-EB11-184 is primarily cytosolic (it starts to localize to microtubules at higher expression levels) with no observed plus-end labeling, but in some cells C-GFP-EB11-184 exhibits +TIP behavior (Figure 6, Supplementary Movie 1 and Supplementary Figure 3). The observation that C-GFP-EB11-184 tracks MT plus ends is surprising, because it has been reported that dimerization is required for EB1 +TIP behavior (Slep and Vale 2007). This observation suggests that this conclusion may be premature, and indeed, Komarova and colleagues (2009) have recently reported that monomeric versions of the EB1 relative EB3 can track MT plus ends.

Figure 6.

Both N- and C-terminally tagged EB11-184 constructs interfere with CLIP-170 MT plus-end localization at higher expression levels (data not shown). The mechanism for this effect is unclear given the relatively poor MT binding of N-GFP EB11-184. The untagged EB11-184 fragment is not recognized by the EB1 antibody (see Materials and Methods), so we were not able to examine the behavior or effect of the untagged EB11-184 fragment.

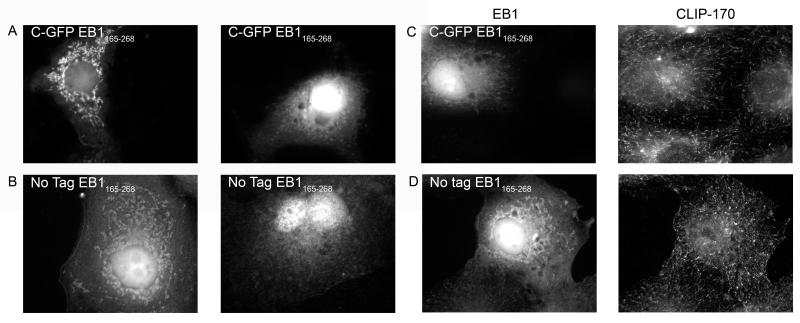

Behavior of “headless” EB1

To fully characterize the behavior of EB1 fragments it is necessary to examine the localization and effects of EB1 constructs lacking the MT-binding CH domain. We examined two of these constructs: one including some of the linker region between the CH domain and the coiled coil (EB1165-268), and one starting at the coiled coil (EB1185-268). The C-GFP version of the EB1165-268 fragment was previously found to be a dominant negative inhibitor of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) or active mDia induced MT stabilization (Wen et al. 2004). As expected, no version of either fragment is observed on MTs or at MT plus ends. However, we saw two localizations that were surprising. First, while the N-GFP versions of these constructs are cytosolic in both fixed cells and live cells (data not shown), the C-terminal and untagged EB1165-268 constructs exhibit some localization to structures that appear to be mitochondria (Figure 7); co-staining with Mitotracker confirmed that these structures are mitochondria (data not shown). With C-GFP EB1165-268 the mitochondrial localization is more apparent in live cells than in fixed cells (Figure 7 and data not shown), but it is still quite prominent in fixed cells transfected with the untagged version of this fragments (Figure 7b, d and data not shown).

Figure 7.

In addition, we were surprised to note that these constructs often have a prominent nuclear localization (Figure 7). It is tempting to dismiss this localization as an artifact. However, it is not simply a GFP-induced artifact because the untagged fragments frequently displayed nuclear localization as well (Figure 7b, d), and neighboring untransfected cells show no nuclear staining (data not shown). These observations caused us to reexamine images of other fragments for possible nuclear localization. Interestingly, full-length tagged EB1 is sometimes found with intense nuclear localization (Figure 2b and data not shown). The significance of this localization is not known.

Effect of “headless” EB1 on CLIP-170

None of the headless EB1 constructs have an obvious effect on CLIP-170 localization even at high expression levels (Figure 7c, d and data not shown). This is surprising for two reasons. First, since these constructs contain the CLIP-170 binding tail but cannot bind to MTs, one would expect them to sequester CLIP-170 in the cytosol or even pull CLIP-170 onto mitochondria. We did not observe either outcome. Second, C-GFP EB1165-268 has been shown to behave as a dominant negative inhibitor of microtubule stabilization as induced by LPA or active mDia (Wen et al. 2004). The observation that this construct has no effect on CLIP-170 localization suggests that this dominant negative effect is not mediated through effects on CLIP-170.

Discussion

EB1 has been the target of intense research since its discovery as an APC binding partner in 1995 (Su et al. 1995). Much of this work has been directed at EB1 itself, but more recently, EB1 has been exploited as a powerful tool for marking dynamic MT plus ends (Dhonukshe et al. 2006; Piehl et al. 2004; Rosa et al. 2006; Stepanova et al. 2003; Tirnauer et al. 2004). Many of these studies have utilized GFP tagged EB1 constructs. A fundamental assumption of these studies has been that the expressed EB1 does not alter the dynamics that it is meant to measure. However, the observation that moderate expression of C-GFP EB1 constructs (both full-length and most of the fragments) displace CLIP-170 from MT plus ends (Figures 3 and 5, see also Komarova et al. 2005) suggests that EB1-GFP is a powerful tool that should be used with caution. At a minimum, it might be prudent to verify that CLIP-170 localization has not been altered at the EB1 expression levels used. However, it is important to remember that CLIP-170 is only one of a surprisingly wide array of proteins that interact with EB1 (Akhmanova and Steinmetz 2008; Lansbergen and Akhmanova 2006), and it is possible that CLIP-170 is neither the most sensitive nor the most significant component of this network.

The behavior of the fragments and the differential effects of N- and C- terminal tags on these fragments provide insight into the function and mechanism of EB1 itself. First, our results are broadly consistent with previous findings about EB1: we see that the N-terminal CH domain is necessary and sufficient for MT binding (Hayashi and Ikura 2003) and that removal of the C-terminal autoinhibitory domain increases the activity of EB1 on MTs (Bu and Su 2003; Hayashi et al. 2005; Manna et al. 2008).

However, some of our observations are puzzling, and others appear to contradict conclusions in the literature. Most importantly, we find that a construct containing only the first 184 amino acids exhibits plus-end tracking behavior (see Supplementary Movie 1 and Supplementary Figure 3). This fragment is generally believed to be monomeric as illustrated by its lack of dimerization with endogenous EB proteins (Komarova et al. 2009). The observation of +TIP behavior by this construct suggests either that the construct dimerizes to some extent, or that dimerization is not a requirement of plus-end tracking behavior as has been proposed (Slep and Vale 2007). Recent work by Komarova et al. (2009) showed that the closely related EB1-relative, EB3, does not require dimerization to track MT plus-ends, consistent with our observation that EB1 lacking the dimerization domain can track MT plus ends.

Another puzzling observation is that most of the EB1 constructs tested altered CLIP-170 localization, including those that should not bind to CLIP-170 (Figures 3, 5, and data not shown). What could be the mechanism(s) of these observations? First, constructs that have normal MT binding but defective CLIP-170 interactions (induced, for example, by the presence of a C-terminal GFP tag) may interfere with CLIP-170 behavior by displacing endogenous EB1 from MT plus ends. In contrast, constructs that bind normally to CLIP-170 but poorly to MTs may cause CLIP-170 to disappear from MT plus ends by trapping it in the cytoplasm. It is possible that some constructs that have effects at relatively low levels do so by heterodimerizing with the endogenous EB1 proteins (Komarova et al. 2009) and interfering with their functions. Finally, any of these constructs could interfere with CLIP-170 localization by directly or indirectly altering MT dynamics. Such an effect might be expected from overexpression of the conserved coiled-coil, which binds to a series of other +TIP proteins. However, there is also the possibility that some of these effects are caused by degradation of endogenous EB1. Recent work has shown that EB1 is protected from degradation by the COP9 signalosome (CSN), a component of the machinery involved in ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis (Peth et al. 2007). Overexpression of EB1 missing the first 120aa leads to degradation of endogenous EB1, apparently by titrating out the interaction with the CSN (Peth et al. 2007). Thus, the puzzling effects of some EB1 fragments on CLIP-170 may actually be due to depletion of endogenous EB1. At present it is not feasible to distinguish between these possibilities.

One construct expected to interfere with CLIP-170 localization, EB1165-268, did not appear to displace CLIP-170 from the plus-ends. This is surprising because this fragment contains the CLIP-binding EB1 tail but lacks the MT binding CH domain. Given that CLIP-170 apparently requires interactions with EB1 to track MT plus ends, this combination of attributes suggests that EB1165-268 should sequester CLIP-170 in the cytoplasm. One explanation is that this fragment does not fold properly, and concerns about folding are reinforced by the frequent localization of this fragment to mitochondria (Figure 7). Perhaps erroneous folding has given this construct irrelevant activities and behaviors. However, Wen et al. demonstrated that an apparently identical EB1 fragment is a dominant negative inhibitor of MT stabilization as induced by LPA or active mDia (Wen et al. 2004), suggesting that it does maintain some relevant activities. The observation that this fragment does not affect CLIP-170 localization suggests that this inhibition is not mediated through effects on CLIP-170.

Additional puzzles emerge from consideration of the interaction between EB1 and MTs. First, it is somewhat surprising that the EB1-MT binding interaction can accommodate the presence of an N-terminal GFP given the strong conservation of the N-terminus and the recent evidence that EB1 binds in the cleft formed at the MT seam (Sandblad et al. 2006). Although the binding of N-GFP EB1 constructs to MTs is weaker than seen with untagged and C-GFP tagged proteins, it is still sufficient to label the length of MTs and to bundle them aggressively when the C-terminal autoinhibition domain is removed (Figures 2, 4, 6, and Supplementary Figure 2). These observations support the idea that other parts of EB1, for example the flexible linker, contribute to MT binding. As mentioned above, it is also likely that the behavior of some fragments at low expression is dictated by heterodimerization with endogenous EB1. However, this does not explain the ability of C-GFP-EB11-184 to track MT plus ends because this fragment lacks the coiled-coil and is thought to be monomeric (Komarova et al. 2009).

This work raises questions about how best to use EB1-GFP as a marker for MT plus ends. It is clear that EB1-GFP is an important and powerful tool for the study of MT dynamics in a large variety of cell types, tissues, and organisms (examples include Browning et al. 2003; Cuschieri et al. 2006; Dawson et al. 2007; Mimori-Kiyosue et al. 2000; Piehl and Cassimeris 2003; Salaycik et al. 2005; Schwartz et al. 1997; Stepanova et al. 2003; Tirnauer et al. 1999). However, care must be used to ensure that expression levels are kept low, and that the tool does not alter the system it is being used to study. In our work expressing full length C-GFP-EB1 in Cos-7 cells, we did not see alterations in CLIP-170 localization until expression levels were “low-moderate”. This level corresponded to a situation where the expressed EB1 was starting to be found along MTs. However, it is possible that this relationship will not hold in other cell types, and that problems with CLIP-170 localization (with concomitant effects on MT dynamics) will appear at lower C-GFP-EB1 levels. It is also important to remember that CLIP-170 is only one of a wide array of proteins that interact with EB1 (Akhmanova and Steinmetz 2008; Lansbergen and Akhmanova 2006), and that other as-yet uncharacterized effects on these proteins may be more significant. When possible, it seems prudent to use stable cell lines expressing minimal amounts of C-GFP-EB1, and to measure MT dynamics in the system to ensure that they are normal as compared to non-expressing controls. CLIP-170 localization provides an additional useful test for whether expression of the EB1 fusion protein is altering the behavior of the system.

In conclusion, this work is the first systematic examination of the localization of EB1 fragments, the effect of tags and tag placement on these fragments, and the effect of expressing these constructs on endogenous CLIP-170. We stress that though effects of EB1 on CLIP-170 have some interest for their own sake, we view CLIP-170 as a proxy (though imperfect) for the complex network of proteins that depend on EB1 for localization and/or activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by 1R01 GM065420 from the National Institutes of Health and the Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry at the University of Notre Dame. We thank members of the Goodson laboratory for insightful discussions and critiques of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Akhmanova A, Hoogenraad CC. Microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins: mechanisms and functions. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Tracking the ends: a dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(4):309–22. doi: 10.1038/nrm2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askham JM, Moncur P, Markham AF, Morrison EE. Regulation and function of the interaction between the APC tumour suppressor protein and EB1. Oncogene. 2000;19(15):1950–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askham JM, Vaughan KT, Goodson HV, Morrison EE. Evidence that an interaction between EB1 and p150(Glued) is required for the formation and maintenance of a radial microtubule array anchored at the centrosome. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(10):3627–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-01-0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berrueta L, Tirnauer JS, Schuyler SC, Pellman D, Bierer BE. The APC-associated protein EB1 associates with components of the dynactin complex and cytoplasmic dynein intermediate chain. Curr Biol. 1999;9(8):425–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80190-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieling P, Kandels-Lewis S, Telley IA, van Dijk J, Janke C, Surrey T. CLIP-170 tracks growing microtubule ends by dynamically recognizing composite EB1/tubulin-binding sites. J Cell Biol. 2008;183(7):1223–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning H, Hackney DD, Nurse P. Targeted movement of cell end factors in fission yeast. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5(9):812–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu W, Su LK. Regulation of microtubule assembly by human EB1 family proteins. Oncogene. 2001;20(25):3185–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bu W, Su LK. Characterization of functional domains of human EB1 family proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(50):49721–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho P, Tirnauer JS, Pellman D. Surfing on microtubule ends. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13(5):229–37. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuschieri L, Miller R, Vogel J. Gamma-tubulin is required for proper recruitment and assembly of Kar9-Bim1 complexes in budding yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(10):4420–34. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-03-0245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson SC, Sagolla MS, Mancuso JJ, Woessner DJ, House SA, Fritz-Laylin L, Cande WZ. Kinesin-13 regulates flagellar, interphase, and mitotic microtubule dynamics in Giardia intestinalis. Eukaryot Cell. 2007;6(12):2354–64. doi: 10.1128/EC.00128-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhonukshe P, Vischer N, Gadella TW., Jr Contribution of microtubule growth polarity and flux to spindle assembly and functioning in plant cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119(Pt 15):3193–205. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixit R, Barnett B, Lazarus JE, Tokito M, Goldman YE, Holzbaur EL. Microtubule plus-end tracking by CLIP-170 requires EB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(2):492–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807614106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dujardin D, Wacker UI, Moreau A, Schroer TA, Rickard JE, De Mey JR. Evidence for a role of CLIP-170 in the establishment of metaphase chromosome alignment. J Cell Biol. 1998;141(4):849–62. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.4.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson HV, Skube SB, Stalder R, Valetti C, Kreis TE, Morrison EE, Schroer TA. CLIP-170 interacts with dynactin complex and the APC-binding protein EB1 by different mechanisms. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2003;55(3):156–73. doi: 10.1002/cm.10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodson HV, Wadsworth P. Methods for Expressing and Analyzing GFP-Tubulin and GFP-Microtubule-associated Proteins. In: Goldman RD, Spector DL, editors. Live cell imaging : a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: 2005. p. xvi.p. 631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi I, Ikura M. Crystal structure of the amino-terminal microtubule-binding domain of end-binding protein 1 (EB1) J Biol Chem. 2003;278(38):36430–4. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi I, Wilde A, Mal TK, Ikura M. Structural basis for the activation of microtubule assembly by the EB1 and p150Glued complex. Mol Cell. 2005;19(4):449–60. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honnappa S, John CM, Kostrewa D, Winkler FK, Steinmetz MO. Structural insights into the EB1-APC interaction. Embo J. 2005;24(2):261–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honnappa S, Okhrimenko O, Jaussi R, Jawhari H, Jelesarov I, Winkler FK, Steinmetz MO. Key interaction modes of dynamic +TIP networks. Mol Cell. 2006;23(5):663–71. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J, Hyman AA. Dynamics and mechanics of the microtubule plus end. Nature. 2003;422(6933):753–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodama A, Karakesisoglou I, Wong E, Vaezi A, Fuchs E. ACF7: an essential integrator of microtubule dynamics. Cell. 2003;115(3):343–54. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00813-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova Y, De Groot CO, Grigoriev I, Gouveia SM, Munteanu EL, Schober JM, Honnappa S, Buey RM, Hoogenraad CC, Dogterom M. Mammalian end binding proteins control persistent microtubule growth. J Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807179. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komarova Y, Lansbergen G, Galjart N, Grosveld F, Borisy GG, Akhmanova A. EB1 and EB3 control CLIP dissociation from the ends of growing microtubules. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(11):5334–45. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-07-0614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansbergen G, Akhmanova A. Microtubule plus end: a hub of cellular activities. Traffic. 2006;7(5):499–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon LA, Shelly SS, Tokito M, Holzbaur EL. The microtubule plus-end proteins EB1 and dynactin have differential effects on microtubule polymerization. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(4):1405–17. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-03-0155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligon LA, Shelly SS, Tokito MK, Holzbaur EL. Microtubule binding proteins CLIP-170, EB1, and p150Glued form distinct plus-end complexes. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(5):1327–32. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Shakiryanova D, Vardya I, Popov SV. Quantitative analysis of microtubule transport in growing nerve processes. Curr Biol. 2004;14(8):725–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna T, Honnappa S, Steinmetz MO, Wilson L. Suppression of microtubule dynamic instability by the +TIP protein EB1 and its modulation by the CAP-Gly domain of p150glued. Biochemistry. 2008;47(2):779–86. doi: 10.1021/bi701912g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Grigoriev I, Lansbergen G, Sasaki H, Matsui C, Severin F, Galjart N, Grosveld F, Vorobjev I, Tsukita S. CLASP1 and CLASP2 bind to EB1 and regulate microtubule plus-end dynamics at the cell cortex. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(1):141–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405094. others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shiina N, Tsukita S. The dynamic behavior of the APC-binding protein EB1 on the distal ends of microtubules. Curr Biol. 2000;10(14):865–8. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00600-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishima M, Maesaki R, Kasa M, Watanabe T, Fukata M, Kaibuchi K, Hakoshima T. Structural basis for tubulin recognition by cytoplasmic linker protein 170 and its autoinhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(25):10346–51. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703876104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison EE. Action and interactions at microtubule ends. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64(3):307–17. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6360-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison EE, Moncur PM, Askham JM. EB1 identifies sites of microtubule polymerisation during neurite development. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2002;98(1-2):145–52. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(01)00290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison EE, Wardleworth BN, Askham JM, Markham AF, Meredith DM. EB1, a protein which interacts with the APC tumour suppressor, is associated with the microtubule cytoskeleton throughout the cell cycle. Oncogene. 1998;17(26):3471–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peth A, Boettcher JP, Dubiel W. Ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of the microtubule end-binding protein 1, EB1, is controlled by the COP9 signalosome: possible consequences for microtubule filament stability. J Mol Biol. 2007;368(2):550–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehl M, Cassimeris L. Organization and dynamics of growing microtubule plus ends during early mitosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14(3):916–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-09-0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piehl M, Tulu US, Wadsworth P, Cassimeris L. Centrosome maturation: measurement of microtubule nucleation throughout the cell cycle by using GFP-tagged EB1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(6):1584–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308205100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre P, Scheel J, Rickard JE, Kreis TE. CLIP-170 links endocytic vesicles to microtubules. Cell. 1992;70(6):887–900. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90240-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickard JE, Kreis TE. Binding of pp170 to microtubules is regulated by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(26):17597–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosa J, Canovas P, Islam A, Altieri DC, Doxsey SJ. Survivin modulates microtubule dynamics and nucleation throughout the cell cycle. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17(3):1483–93. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-08-0723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salaycik KJ, Fagerstrom CJ, Murthy K, Tulu US, Wadsworth P. Quantification of microtubule nucleation, growth and dynamics in wound-edge cells. J Cell Sci. 2005;118(Pt 18):4113–22. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandblad L, Busch KE, Tittmann P, Gross H, Brunner D, Hoenger A. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe EB1 homolog Mal3p binds and stabilizes the microtubule lattice seam. Cell. 2006;127(7):1415–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler SC, Pellman D. Microtubule “plus-end-tracking proteins”: The end is just the beginning. Cell. 2001;105(4):421–4. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00364-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz K, Richards K, Botstein D. BIM1 encodes a microtubule-binding protein in yeast. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8(12):2677–91. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.12.2677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep KC, Rogers SL, Elliott SL, Ohkura H, Kolodziej PA, Vale RD. Structural determinants for EB1-mediated recruitment of APC and spectraplakins to the microtubule plus end. J Cell Biol. 2005;168(4):587–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200410114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slep KC, Vale RD. Structural basis of microtubule plus end tracking by XMAP215, CLIP-170, and EB1. Mol Cell. 2007;27(6):976–91. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanova T, Slemmer J, Hoogenraad CC, Lansbergen G, Dortland B, De Zeeuw CI, Grosveld F, van Cappellen G, Akhmanova A, Galjart N. Visualization of microtubule growth in cultured neurons via the use of EB3-GFP (end-binding protein 3-green fluorescent protein) J Neurosci. 2003;23(7):2655–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02655.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LK, Burrell M, Hill DE, Gyuris J, Brent R, Wiltshire R, Trent J, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. APC binds to the novel protein EB1. Cancer Res. 1995;55(14):2972–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer JS, O’Toole E, Berrueta L, Bierer BE, Pellman D. Yeast Bim1p promotes the G1-specific dynamics of microtubules. J Cell Biol. 1999;145(5):993–1007. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer JS, Salmon ED, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule plus-end dynamics in Xenopus egg extract spindles. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15(4):1776–84. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valetti C, Wetzel DM, Schrader M, Hasbani MJ, Gill SR, Kreis TE, Schroer TA. Role of dynactin in endocytic traffic: effects of dynamitin overexpression and colocalization with CLIP-170. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10(12):4107–20. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.12.4107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan KT. TIP maker and TIP marker; EB1 as a master controller of microtubule plus ends. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(2):197–200. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisbrich A, Honnappa S, Jaussi R, Okhrimenko O, Frey D, Jelesarov I, Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Structure-function relationship of CAP-Gly domains. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(10):959–67. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Eng CH, Schmoranzer J, Cabrera-Poch N, Morris EJ, Chen M, Wallar BJ, Alberts AS, Gundersen GG. EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(9):820–30. doi: 10.1038/ncb1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu XS, Tsan GL, Hammer JA., 3rd Melanophilin and myosin Va track the microtubule plus end on EB1. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(2):201–7. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M, Wakamatsu Y, Itoh TJ, Shoji T, Hashimoto T. Arabidopsis SPIRAL2 promotes uninterrupted microtubule growth by suppressing the pause state of microtubule dynamics. J Cell Sci. 2008;121(Pt 14):2372–81. doi: 10.1242/jcs.030221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.