Abstract

Background

In utero retinoid exposure results in numerous craniofacial malformations, including craniosynostosis. Although many malformations associated with retinoic acid syndrome are associated with neural crest defects, the specific mechanisms of retinoid-induced craniosynostosis remain unclear. The authors used the culture of mouse cranial suture–derived mesenchymal cells to probe the potential cellular mechanisms of this teratogen to better elucidate mechanisms of retinoid-induced suture fusion.

Methods

Genes associated with retinoid signaling were assayed in fusing (posterofrontal) and patent (sagittal, coronal) sutures by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Cultures of mouse suture–derived mesenchymal cells from the posterofrontal suture were established from 4-day-old mice. Cells were cultured with all-trans retinoic acid (1 and 5 µM). Proliferation, osteogenic differentiation, and specific gene expression were assessed.

Results

Mouse sutures were found to express genes necessary for retinoic acid synthesis, binding, and signal transduction, demonstrated by quantitative realtime polymerase chain reaction (Raldh1, Raldh2, Raldh3, and Rbp4). These genes were not found to be differentially expressed in fusing as compared with patent cranial sutures in vivo. Addition of retinoic acid enhanced the osteogenic differentiation of suture-derived mesenchymal cells in vitro, including up-regulation of alkaline phosphatase activity and Runx2 expression. Contemporaneously, cellular proliferation was repressed, as shown by proliferative cell nuclear antigen expression. The pro-osteogenic effect of retinoic acid was accompanied by increased gene expression of several hedgehog and bone morphogenetic protein ligands.

Conclusions

Retinoic acid represses proliferation and enhances osteogenic differentiation of suture-derived mesenchymal cells. These in vitro data suggest that retinoid exposure may lead to premature cranial suture fusion by means of enhanced osteogenesis and hedgehog and bone morphogenetic protein signaling.

Clinical and experimental data have demonstrated that vitamin A and its metabolites, or retinoids, can act as powerful teratogens.1 Over 50 years ago, the first teratogenic effects of hypervitaminosis A were discovered.2 More than 20 years ago, the widespread use of 13-cis-retinoic acid for the treatment of cystic acne resulted in severe congenital malformations.3 Since that time, retinoids and retinoic acid exposure have been associated with numerous craniofacial defects,4–8 including craniosynostosis or premature cranial suture fusion. For example, experimental exposure to teratogenic doses of retinoic acid in non-human primates results in a 100 percent incidence of coronal craniosynostosis.9 Moreover, epidemiologic studies in humans have associated in utero hypervitaminosis A with an increased risk of craniosynostosis.10 Recently, expression of retinol-binding protein 4 (Rbp4) has been shown by microarray analysis and immunohistochemistry to precipitously decline in human craniosynostotic sutures, both syndromic and sporadic.11 Rbp4 is assumed to be one factor controlling the local concentration of retinol.12 The specific, cellular mechanisms of retinoid-induced craniosynostosis remain poorly understood. However, retinoic acid is known to modulate the activation of a number of signaling cascades of importance in cranial suture biology. These include but are not limited to fibroblast growth factor,13 transforming growth factor-β, bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling,14–17 and hedgehog signaling.18,19

Numerous studies have examined the effects of retinoic acid on the in vitro osteogenic differentiation of bone-forming cells. In general, pharmacologic concentrations of retinoic acid enhance in vitro osteogenesis in multiple cell types, including cell lines,20 calvarial osteoblasts,21 and mesenchymal stem cells.22–25 However, retinoic acid does not ubiquitously induce osteogenic differentiation, as conflicting reports exist in the literature. The effects of retinoic acid in osteogenic differentiation of cells derived from the suture complex have not yet been described. Moreover, the mechanisms of retinoic acid–induced osteogenesis are not fully elucidated. Retinoic acid is known to increase expression of BMP-2 and BMP-4, and synergism has been demonstrated been between retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein signaling in osteogenesis.23,26–28 Locoregional differences in bone morphogenetic protein agonist and antagonists have been shown to underlie the processes of normal and pathologic suture fusion.29–31

The study of suture fusion in animal models has led to significant insights into the signaling pathways of importance in cranial suture biology.29,32 Our laboratory has specifically studied the murine posterofrontal suture as a paradigm of physiologic, programmed suture fusion. The posterofrontal suture is the only suture in the mouse skull to undergo fusion, and it does so in a highly orchestrated fashion within the first weeks of life.33 The molecular mechanisms that underlie this process, however, remain incompletely understood.34 Our laboratory has recently used the isolation and culture of mouse suture–derived mesenchymal cells to better understand cellular and molecular cranial suture biology.35 Suture-derived mesenchymal cells isolated from the posterofrontal suture have been observed to have unique properties in vitro, including a robust capacity for osteogenic differentiation.35 Moreover, posterofrontal suture–derived mesenchymal cells differentially respond to various cytokines important in cranial suture biology, including basic fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor-β1 and its isoforms.35–37 In the current study, we examined the effects of all-trans retinoic acid signaling in posterofrontal suture–derived mesenchymal cells to better elucidate potential mechanisms of retinoid-induced premature suture fusion.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and Supplies

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (catalogue no. 10565-018) and penicillin/streptomycin (catalogue no. 15140-163) were purchased from Gibco Life Technologies (Carlsbad, Calif.). Fetal bovine serum was purchased from Omega Scientific (Tarzana, Calif.). All-trans-retinoic acid (catalogue no. R2625), β-glycerophosphate (catalogue no. G9891), and ascorbic acid (catalogue no. A8960) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo.). All cell culture wares were purchased from Corning, Inc. (San Mateo, Calif.). Unless otherwise specified, all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Tissue Harvest and Primary Cell Culture

Posterofrontal suture-derived mesenchymal cells were harvested from 4-day-old CD-1 mice (n = 70) (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, Mass.) as described previously.35,37,38 Posterofrontal sutures with 500-µm bony margins were dissected with great care to remove all dural and pericranial tissue (Fig. 1). Suture explants were cultured in standard growth medium containing Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 100 IU/ml of penicillin/streptomycin. Sutures were placed with the endocranial surface face down to the culture dish, allowing for cellular migration (Fig. 1, below, right). Approximately 10 sutures were placed per 100-mm culture dish in 3 ml of standard growth medium, yielding six separate but similar populations of cells that were used for further assays. Explants were maintained at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% carbon dioxide; medium was changed every other day. After 8 days, the migrated cells were passaged by trypsinization. Suture-derived mesenchymal cells of passage 1 only were used.

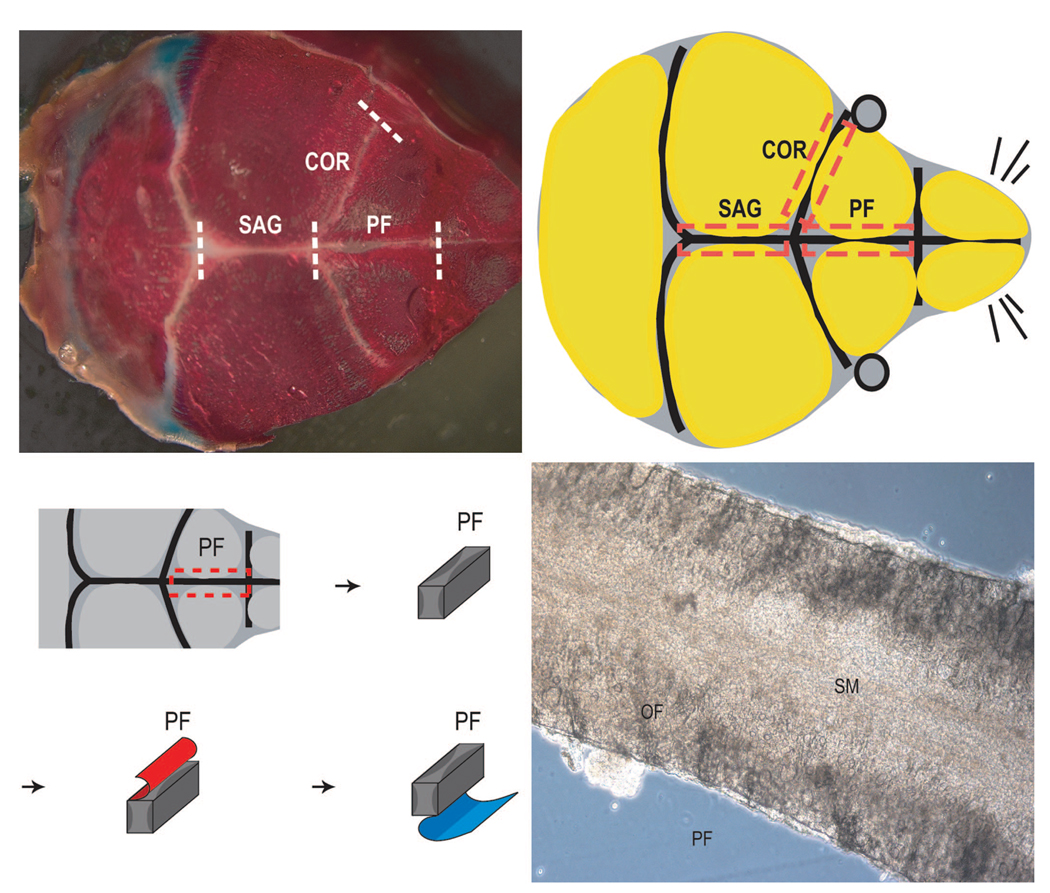

Fig. 1.

Appearance of mouse skull and dissection of mouse sutures. (Above left) Overhead view of the postnatal day-7 mouse skull as shown by bone and cartilage whole-mount preparation. Bone appears red and cartilage appears blue. The posterofrontal (PF) suture lies between paired frontal bones. Caudal to this, the sagittal (SAG) suture lies between paired parietal bones. Lateral to this, the coronal (COR) suture lies between paired frontal and parietal bones. (Above, right) Schema of overhead view in which the limitations of suture mesenchyme dissection are indicated by dashed red lines. The calvarial bones are shown in yellow. The anterior delimitation of the posterofrontal suture is the jugum limitans, and the bregma fontanelle marks the posterior delimitation. The sagittal suture begins at the bregma and ends posteriorly at the lambdoid suture. (Below, left) Once the suture mesenchyme is dissected, the pericranium is meticulously dissected off (red), followed by total removal of dural tissues (blue). (Below, right) Photomicrograph showing posterofrontal suture explant with 500-µm bony margins. Cells will migrate from the explant over 8 days in culture and are termed suture-derived mesenchymal cells. SM, suture mesenchyme; OF, osteogenic front. Original magnification, × 200.

Cellular Viability and Proliferation Assays

First, cell viability was assessed by trypan blue staining. Cells were treated with all-trans retinoic acid (retinoic acid, 1 and 5 µM) or vehicle control (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide) for up to 6 days in standard growth medium. Cell counting was performed by using a hemocytometer after staining with trypan blue (n = 4). The percentage positively stained cells was calculated. Less than 5 percent was considered normal cell turnover in culture.

To assess proliferation, relative gene expression of proliferative cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) was determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Cells were seeded onto 12-well plates at a density of 30,000 cells per well (n = 3). After attachment, cells were treated with standard growth medium with vehicle control (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide), osteogenic differentiation medium alone (consisting of standard growth medium with 100 µg/ml ascorbic acid, 10 mM β-glycerophosphate), or osteogenic differentiation medium with retinoic acid (1 µM). After 24, 48, and 96 hours, total RNA was isolated; relative gene expression of PCNA was determined by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction as described below.

Osteogenic Differentiation and Assessments

For osteogenic differentiation, cells were seeded onto 24-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well. On attachment, suture-derived mesenchymal cells were treated with standard growth medium with vehicle control (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide), osteogenic differentiation medium with vehicle control (0.1% dimethylsulfoxide), or osteogenic differentiation medium with retinoic acid (1 and 5 µM). Vehicle control was 0.1% dimethylsulfoxide. Medium was replenished after every 3 days of differentiation.

Alkaline phosphatase staining was performed at 1 week as described previously35 (n = 4). Cells were fixed with a 60% acetone/40% citrate solution and stained with a diazonium salt with 4% naphthol AS-MX phosphate alkaline solution. Alkaline phosphatase–positive cells appear purple.

RNA was isolated at 0, 1, 2, and 4 days of differentiation. Markers of osteogenic differentiation [runt-related transcription factor 2 (Runx2), alkaline phosphatase, type I collagen (Col1a1), osteopontin, bone morphogenetic protein-2 (Bmp2), hedgehog signaling (Sonic hedgehog, Indian hedgehog, Desert hedgehog, Patched-1, Gli1, Gli2, and Gli3] and retinoic acid synthesis and signaling transduction (Raldh 1–3, Rbp4, Rara, Rarg, and Rxra) were examined.

RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction

Total RNA was isolated from cells as described previously.35 In addition, RNA was isolated from microdissected sutures (posterofrontal, coronal and sagittal) without dura mater or pericranium on day 7 of life (n = 10 animals). Isolation was performed with the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Sciences, Frederick, Md.). DNase treatment was carried out with the DNA-free kit (Ambion, Inc., Austin, Texas). Reverse transcription was performed with Taqman Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction was carried out using the Applied Biosystems Prism 7900HT Sequence Detection System and Power Sybr Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Specific primers for the genes examined were designed based on their PrimerBank (http://pga.mgh.harvard.edu/primerbank/) sequence. See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, for quantitative polymerase chain reaction genes and primer sequences, http://links.lww.com/PRS/A154. The levels of gene expression were determined by normalizing to values of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. All reactions were performed in triplicate.

Statistical Analysis

Means and standard deviations were calculated from numerical data, as presented in the text, figures, and figure legends. In figures, bar graphs represent means, whereas error bars represent 1 SD. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way analysis of variance with replication when more than two factors were compared. In addition, the Welch two-tailed t test was used when standard deviations between groups were unequal. Inequality of standard deviations was confirmed by the Levene test, in which values of p < 0.05 were considered significant. For all other tests, a value of p ≤ 0.01 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Anatomical Relationship of the Posterofrontal and Sagittal Sutures

A brief verification of the general anatomy of the mouse calvaria was performed (Fig. 1). The posterofrontal suture was observed to lie anterior to the sagittal suture. The former is flanked by the frontal bones, whereas the latter is flanked by parietal bones (Fig. 1, above, left). The coronal sutures lie laterally, between the frontal and parietal bones. The posterofrontal suture was observed to begin its process of programmed suture fusion at or around postnatal day 7. Suture-derived mesenchymal cells were obtained from the posterofrontal suture on day 4 of life, before this process had begun (Fig. 1, below).

Differential Expression of Retinoic Acid Enzymes in Posterofrontal, Coronal, and Sagittal Sutures

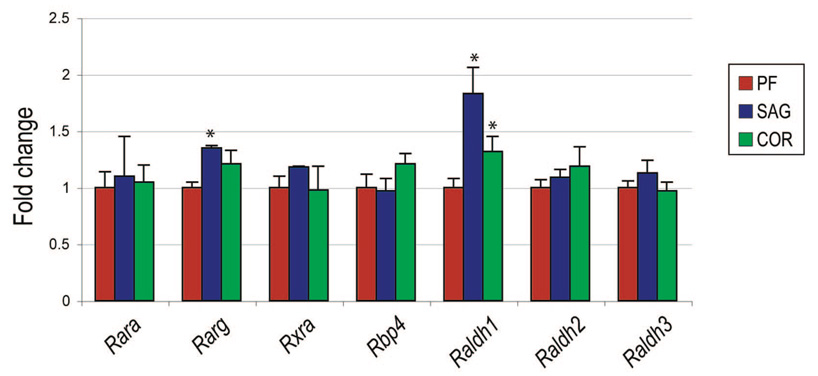

Next, we sought to examine the relative expression of retinoic acid receptors and synthesis enzymes in fusing and patent sutures. We chose to examine expression levels in the postnatal day-7 calvaria, a time point just as the sutures begin to obtain divergent morphologies.38 By quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, we found expression of all components of retinoic acid synthesis to be expressed in posterofrontal, sagittal, and coronal sutures (Raldh1, Raldh2, and Raldh3) (Fig. 2). Retinoic acid receptors were also expressed (Rara, Rarg, and Rxra), as was Rbp4. Notably, most components of the retinoic acid signaling system were equally expressed when comparing posterofrontal to the patent coronal and sagittal sutures. These data suggested that endogenous retinoic acid signaling may not play a dictatorial role in physiologic suture fusion.

Fig. 2.

Expression of retinoic acid signaling elements in posterofrontal (PF), sagittal (SAG), and coronal (COR) sutures. Posterofrontal, sagittal, and coronal sutures were microdissected from 10 p7 mice; relative gene expression was assayed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Results demonstrated similar expression levels of most retinoic acid signaling elements when sutures were compared. Interestingly, both Rarg and Raldh1 were observed to be predominantly expressed in the sagittal suture (n = 10 mice, *p < 0.01).

All-Trans Retinoic Acid Enhances Alkaline Phosphatase Activity in Suture-Derived Mesenchymal Cells

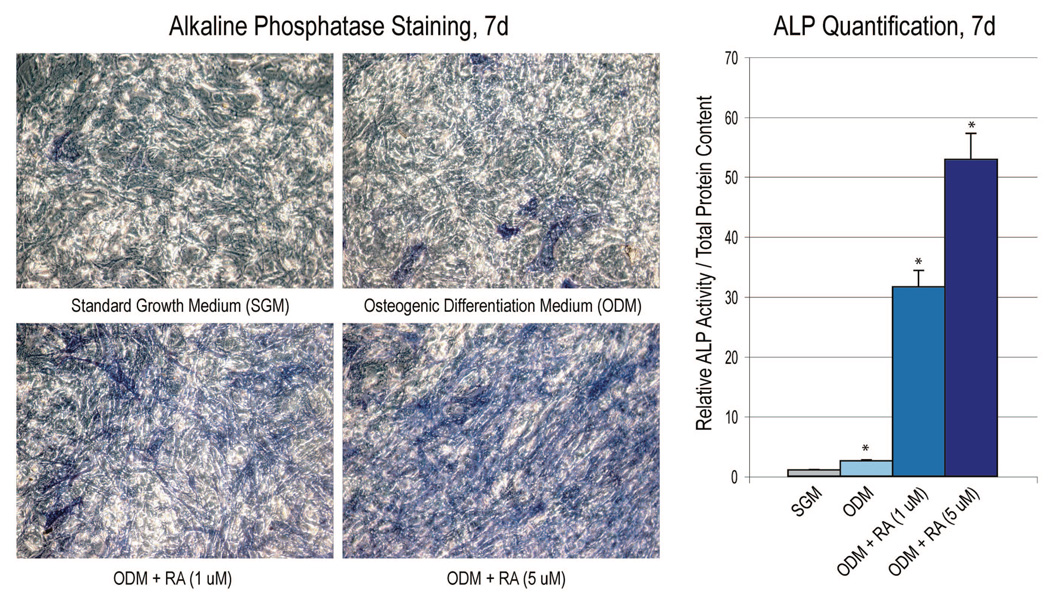

Having demonstrated that mouse sutures express genes necessary for the synthesis, storage, and signal transduction of retinoic acid, we inquired as to the effects of exogenous all-trans retinoic acid on the osteogenic differentiation of suture-derived mesenchymal cells. Pharmacologic concentrations of retinoic acid have been shown to increase osteogenesis in various bone-forming cells in vitro, including cell lines,20 calvarial osteoblasts,21 and mesenchymal stem cells.22,23 Alkaline phosphatase expression was examined after 7 days’ culture in standard growth medium alone, osteogenic differentiation medium alone, or osteogenic differentiation medium with retinoic acid (1 and 5 µM). This was performed both by microscopic imaging of staining and by quantification of enzymatic activity normalized to total protein content (Fig. 3). As expected, osteogenic differentiation medium alone increased alkaline phosphatase activity over growth medium alone (Fig. 3, above, left and above, center) (n = 4). Retinoic acid when added to osteogenic differentiation medium increased alkaline phosphatase activity over 30- and 50- fold at 1 and 5 µM, respectively (Fig. 3, above, left and above, center) (n = 4).

Fig. 3.

Retinoic acid enhances alkaline phosphatase activity in suture-derived mesenchymal cells. Alkaline phosphatase staining and quantification were performed at 7 days’ differentiation. (Left and center) Alkaline phosphatase staining, appearing purple (original magnification, ×20). (Right) Quantification of the alkaline phosphatase enzymatic activity was assessed, normalizing to total protein content. SGM, standard growth medium; ODM, osteogenic differentiation medium; RA, retinoic acid; ALP, alkaline phosphatase. Values represent calculated means and are normalized to culture in standard growth medium (gray bar); error bars = 1 SD; n = 4; *p < 0.01.

Retinoic Acid Enhances Osteoblast Gene Expression and Represses PCNA Expression in Suture-Derived Mesenchymal Cells

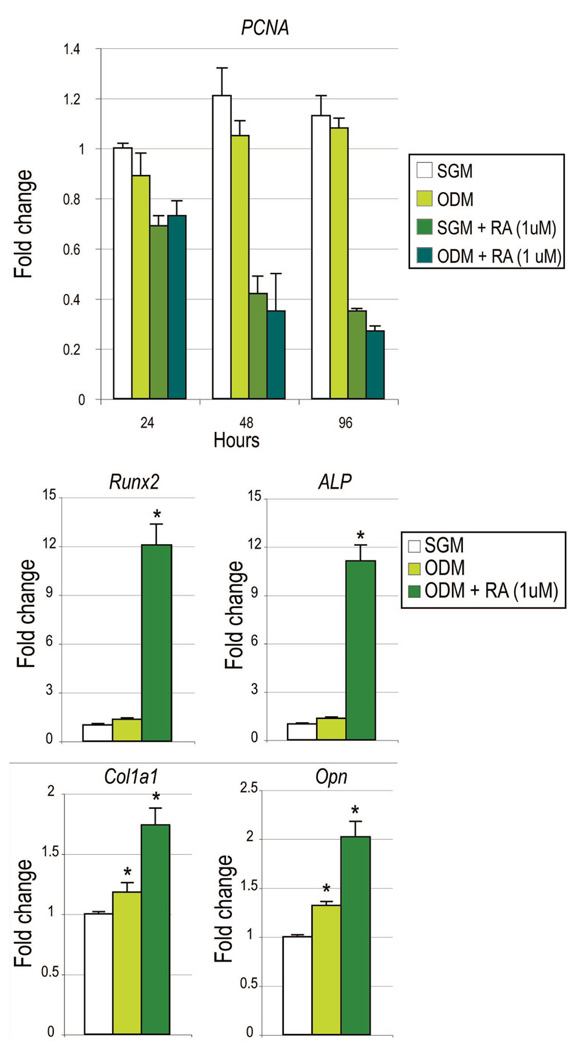

A theoretical inverse relationship exists in cell culture between proliferation and differentiation. Thus, a potent mitogen might be expected to simultaneously repress cellular differentiation. We sought to determine the effect of retinoic acid on suture-derived mesenchymal cell proliferation and differentiation (Fig. 4). PCNA expression was evaluated after 24, 48, and 96 hours in standard growth medium alone, osteogenic differentiation medium alone, standard growth medium with retinoic acid, or osteogenic differentiation medium with retinoic acid (1 µM, which is the minimum concentration needed to have a significant osteogenic effect). Results showed a small, non–statistically significant decrease in PCNA expression on addition of osteogenic differentiation medium alone (Fig. 4, above). However, a marked and significant decrease in PCNA transcript abundance was observed on addition of retinoic acid to either standard growth medium or osteogenic differentiation medium (Fig. 4, above) (n = 3).

Fig. 4.

Retinoic acid represses proliferation and enhances osteogenic gene expression in suture-derived mesenchymal cells. (Above) PCNA expression was assessed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction as a marker of cell proliferation. Cells were cultured in standard growth medium alone (SGM), osteogenic differentiation medium (ODM) alone, standard growth medium (SGM) with retinoic acid (RA), or osteogenic differentiation medium with retinoic acid. Retinoic acid significantly decreased PCNA expression across all time points. (Center and below) Osteogenic gene markers were assessed after 96 hours in culture by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, including Runx2, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), type I collagen (Col1α1), and osteopontin (Opn). Values are normalized to groups cultured in standard growth medium (whitebars); error bars = 1 SD; n = 3;*p ≤ 0.01.

To confirm retinoic acid–induced osteogenic gene expression in suture-derived mesenchymal cells, various osteogenic genes were assayed after 96 hours in culture (Fig. 4, center and below). As expected, a small induction of gene expression was observed with osteogenic differentiation medium alone. In contrast, a significant increase in all genes was observed with addition of retinoic acid to osteogenic differentiation medium, including an over 12-fold increase in Runx2 and a 10-fold increase in ALP expression (Fig. 4, center) (n = 3).

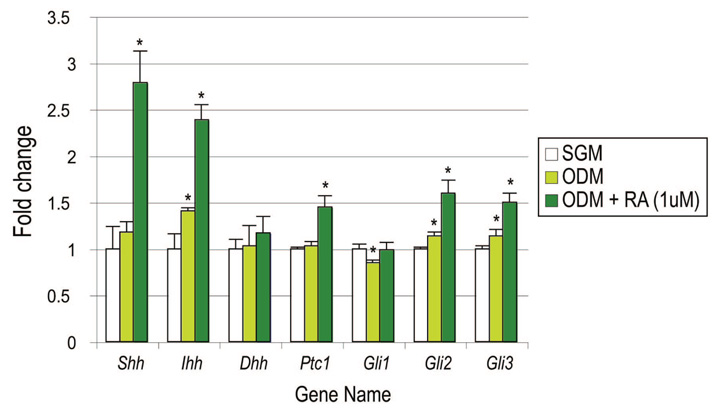

Retinoic Acid Increases Hedgehog Signaling in Suture-Derived Mesenchymal Cells

Hedgehog signaling, mediated by the three ligands Sonic, Indian, and Desert hedgehog, has been shown to be important in basic osteochon-droblast biology.39 We thus inquired as to whether retinoic acid may transcriptionally regulate hedgehog family members, thereby helping to explain the pro-osteogenic effect of retinoic acid (Fig. 5). Results by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction showed by 96 hours in culture an approximate 2.5-fold induction of both Sonic and Indian hedgehog on addition of retinoic acid to osteogenic differentiation medium (n = 3) (Fig. 5, far left). This was accompanied by an increase in the hedgehog transduction elements Gli2 and Gli3 (n = 3) (Fig. 5, far right).

Fig. 5.

Retinoic acid increases hedgehog expression in suture-derived mesenchymal cells. Suture-derived mesenchymal cells were cultured for 96 hours in either standard growth medium (SGM) alone, osteogenic differentiation medium (ODM) alone, or osteogenic differentiation medium with retinoic acid (RA). Various hedgehog signaling elements were assayed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Shh, Sonic hedgehog; Ihh, Indian hedgehog; Dhh, Desert hedgehog; Ptc1, Patched-1. Values are normalized to groups cultured in standard growth medium (whitebars); error bars = 1 SD; n = 3; *p ≤ 0.01.

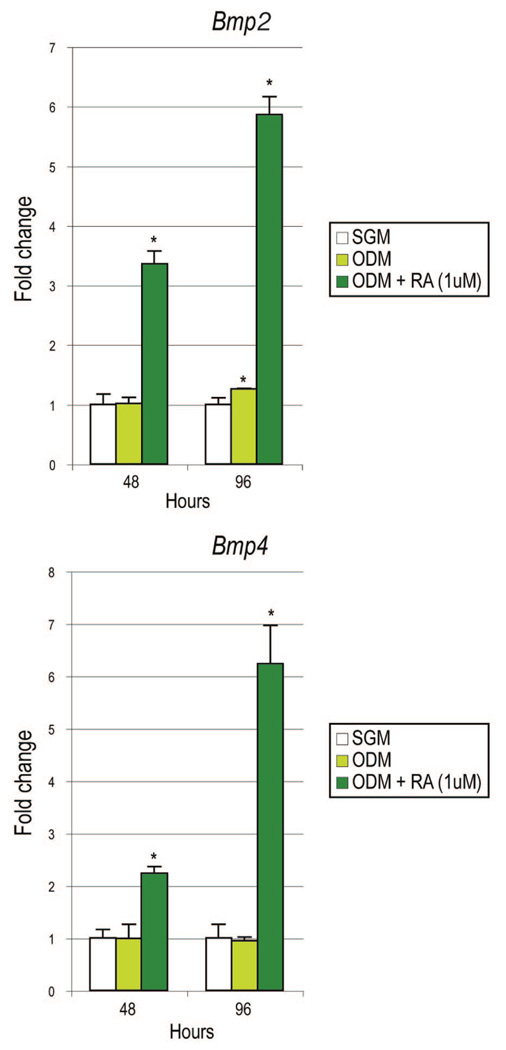

Retinoic Acid Increases Bone Morphogenetic Protein Signaling in Suture-Derived Mesenchymal Cells

Although retinoic acid induced hedgehog expression in suture-derived mesenchymal cells, this was observed to occur to a much lesser degree than the observed increase in alkaline phosphatase activity. Thus, we explored the expression of other potential pro-osteogenic cytokines on retinoic acid stimulation, namely, the bone morphogenetic protein family (Fig. 6). By quantitative realtime polymerase chain reaction, addition of retinoic acid to osteogenic differentiation medium resulted in increased transcript abundance for both Bmp2 and Bmp4 at 48 and 96 hours in culture (Fig. 6) (n = 3). By 96 hours, this amounted to an approximately sixfold increase in both Bmp2 and Bmp4 (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Retinoic acid increases bone morphogenetic protein expression in suture-derived mesenchymal cells. (Above) Bmp2 expression was assessed by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction after 48 and 96 hours. Cells were cultured in standard growth medium (SGM), osteogenic differentiation medium (ODM), or osteogenic differentiation medium with retinoic acid (RA). (Below) Bmp4 expression was similarly assayed. Values are normalized to groups cultured in standard growth medium (white bars); error bars = 1 SD; n = 3; *p ≤ 0.01.

DISCUSSION

A number of teratogens have been shown to induce premature cranial suture fusion, including aminopterin, diphenylhydantoin, and valproic acid.40 Perhaps the most notorious of these is retinoic acid, as retinoids are found with abundance in multivitamins, fortified food and drink, and acne medications. Epidemiologic studies have proved invaluable in making correlations between in utero exposure and subsequent craniofacial anomalies. However, the mechanistic insights that link biomolecular pathways to teratogen exposure to facial dysmorphism are as yet unclear. This gap in knowledge was the impetus to study the effects of retinoic acid on mouse suture–derived mesenchymal cells.

We focused our attention in particular on suture-derived mesenchymal cells from the fusing posterofrontal suture. It is important to note that the fusion of the posterofrontal suture is physiologic as opposed to pathologic, which is seen in clinical craniosynostosis. Posterofrontal suture– derived mesenchymal cells have been previously observed to have a robust capacity in vitro for osteogenic differentiation as compared with suture-derived mesenchymal cells taken from the normally patent sagittal suture.35 Moreover, they respond uniquely to various cytokine signals such as basic fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor-β isoforms.35,37 We hypothesized that retinoic acid may have a pro-osteogenic effect in this population of cells, as has been described in other preosteoblast cell types.21,22 After demonstrating the pro-osteogenic potential of suture-derived mesenchymal cells, we attempted to unravel potential mechanisms through which retinoic acid may exert its pro-osteogenic effect. We hypothesized that the soluble factors induced by retinoic acid in suture-derived mesenchymal cells in vitro may parallel those factors induced by retinoids in utero.

It is interesting to note that retinoic acid is not observed to have a pro-osteogenic effect in all cell and tissue types. For example, conflicting data exist in the literature regarding the precise effects of retinoic acid on osteoblasts in vitro, and whether the effect is pro-osteogenic, permissive of osteogenesis, or even antiosteogenic.20–22,41 A prime example of this is in the developing palate, a tissue type where retinoic acid seems to have the opposite effect as in the developing calvaria. Instead of palatal hypertrophic ossification, retinoic acid has long been recognized to induce palatal suture clefting.5 This apparently dichotomous effects of the same teratogen are intriguing and may depend on the dose of in utero exposure and different receptor expression profiles. More intriguing, however, is to speculate that a cell type–dependent effect exists where retinoic acid may either produce cell death or inhibit cell proliferation in the palate while inducing differentiation in the cranial vault. At present, these mechanisms are merely speculative. Future study will examine the differential modulation of gene expression by retinoic acid in the calvaria as compared with palate.

Retinoic acid is known to regulate the expression patterns of hedgehog signaling, although whether this is a positive or negative relationship depends on the cell type or model system.18,19 It is known that mice with genetic deficiency in Indian hedgehog have severe skeletal defects, including severely shortened limbs caused by a defect in endochondral ossification.42 Moreover, the Indian hedgehog null mouse has a cranial suture phenotype with reduced calvarial bone size, although this has not been well studied.42 In addition, preliminary data from our laboratory suggest that increased hedgehog signaling (by means of the addition of N-terminal Sonic hedgehog to osteogenic medium) significantly enhances the osteogenic differentiation of suture-derived mesenchymal cells in a fashion similar to retinoic acid (data not shown). However, it is worthwhile to note that the moderate up-regulation of hedgehog ligands did not rival the approximately 30-fold increase in alkaline phosphate activity. Thus, we hypothesized it was unlikely that the pro-osteogenic effect of retinoic acid is mediated solely by hedgehog signaling.

Bone morphogenetic protein signaling and bone morphogenetic protein antagonists have been shown to be differentially expressed in fusing and patent cranial sutures.29 Moreover, manipulation of bone morphogenetic protein signaling leads to altered cranial suture fate.29 Interestingly, retinoic acid–mediated osteogenesis has been shown to be accompanied by an increase in bone morphogenetic protein elaboration.15,16 Our findings in posterofrontal suture–derived mesenchymal cells indicate that retinoic acid increases bone morphogenetic protein expression. It is intriguing to speculate that suture fate (osseous fusion or ongoing patency) is altered on exposure to retinoids in utero by the up-regulation of both hedgehog and bone morphogenetic protein pathways. More specific studies of in vivo gene expression patterns and in vivo perturbations of retinoic acid signaling are warranted to determine whether such a relationship exists.

CONCLUSIONS

All-trans retinoic acid induces osteogenesis in suture-derived mesenchymal cells. This in vitro phenomenon is accompanied by repressed proliferation and an induction of bone morphogenetic protein transcription. These in vitro data have implications toward determining the mechanisms of retinoid-induced craniosynostosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Michael T. Longaker, M.D., M.B.A., was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research grants R01 DE-13194 and R21-DE019274, the Oak Foundation, and the Hagey Foundation; Antoine L. Carre, M.D., M.P.H., was supported by the Hagey Foundation Fellowship; and Benjamin Levi, M.D., was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases grant 1F32AR057302-01.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. A direct URL citation appears in the printed text; simply type the URL address into any Web browser to access this content. A clickable link to the material is provided in the HTML text of this article on the Journal’s Web site (www.PRSJournal.com).

REFERENCES

- 1.Geelen JA. Hypervitaminosis A induced teratogenesis. CRC Crit Rev Toxicol. 1979;6:351–375. doi: 10.3109/10408447909043651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohlan SQ. Congenital anomalies in the rat produced by excessive intake of vitamin A during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 1954;13:556–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammer EJ, Chen DT, Hoar RM, et al. Retinoic acid embryopathy. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:837–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198510033131401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vieux-Rochas M, Coen L, Sato T, et al. Molecular dynamics of retinoic acid-induced craniofacial malformations: Implications for the origin of gnathostome jaws. PLoS One. 2007;2:e510. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morriss-Kay G. Retinoic acid and craniofacial development: Molecules and morphogenesis. Bioessays. 1993;15:9–15. doi: 10.1002/bies.950150103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richman JM. The role of retinoids in normal and abnormal embryonic craniofacial morphogenesis. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1992;4:93–109. doi: 10.1177/10454411920040010701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM, Morriss-Kay GM. Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol. 2002;241:106–116. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston MC, Bronsky PT. Prenatal craniofacial development: New insights on normal and abnormal mechanisms. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1995;6:25–79. doi: 10.1177/10454411950060010301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yip JE, Kokich VG, Shepard TH. The effect of high doses of retinoic acid on prenatal craniofacial development in Macaca nemestrina. Teratology. 1980;21:29–38. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420210105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner JS, Guyard-Boileau B, Alderman BW, Fernbach SK, Greene C, Mangione EJ. Maternal exposure to prescription and non-prescription pharmaceuticals or drugs of abuse and risk of craniosynostosis. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:64–67. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coussens AK, Wilkinson CR, Hughes IP, et al. Unravelling the molecular control of calvarial suture fusion in children with craniosynostosis. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:458. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quadro L, Blaner WS, Hamberger L, et al. The role of extrahepatic retinol binding protein in the mobilization of retinoid stores. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1975–1982. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400137-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao X, Duester G. Effect of retinoic acid signaling on Wnt/beta-catenin and FGF signaling during body axis extension. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9:430–435. doi: 10.1016/j.gep.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmood R, Flanders KC, Morriss-Kay GM. The effects of retinoid status on TGF beta expression during mouse embryogenesis. Anat Embryol. 1995;192:21–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00186988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halilagic A, Ribes V, Ghyselinck NB, Zile MH, Dollé P, Studer M. Retinoids control anterior and dorsal properties in the developing forebrain. Dev Biol. 2007;303:362–375. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee SH, Fu KK, Hui JN, Richman JM. Noggin and retinoic acid transform the identity of avian facial prominences. Nature. 2001;414:909–912. doi: 10.1038/414909a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paralkar VM, Grasser WA, Mansolf AL, et al. Regulation of BMP-7 expression by retinoic acid and prostaglandin E(2) J Cell Physiol. 2002;190:207–217. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schneider RA, Hu D, Rubenstein JL, Maden M, Helms JA. Local retinoid signaling coordinates forebrain and facial morphogenesis by maintaining FGF8 and SHH. Development. 2001;128:2755–2767. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.14.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helms JA, Kim CH, Hu D, Minkoff R, Thaller C, Eichele G. Sonic hedgehog participates in craniofacial morphogenesis and is down-regulated by teratogenic doses of retinoic acid. Dev Biol. 1997;187:25–35. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Choong PF, Martin TJ, Ng KW. Effects of ascorbic acid, calcitriol, and retinoic acid on the differentiation of preosteoblasts. J Orthop Res. 1993;11:638–647. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100110505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song HM, Nacamuli RP, Xia W, et al. High-dose retinoic acid modulates rat calvarial osteoblast biology. J Cell Physiol. 2005;202:255–262. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malladi P, Xu Y, Yang GP, Longaker MT. Functions of vitamin D, retinoic acid, and dexamethasone on mouse adipose-derived mesenchymal cells (AMCs) Tissue Eng. 2006;12:2031–2040. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wan DC, Shi YY, Nacamuli RP, Quarto N, Lyons KM, Longaker MT. Osteogenic differentiation of mouse adipose-derived adult stromal cells requires retinoic acid and bone morphogenetic protein receptor type IB signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12335–12340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604849103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leboy PS, Beresford JN, Devlin C, Owen ME. Dexamethasone induction of osteoblast mRNAs in rat marrow stromal cell cultures. J Cell Physiol. 1991;146:370–378. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041460306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Descalzi Cancedda F, Gentili C, Manduca P, Cancedda R. Hypertrophic chondrocytes undergo further differentiation in culture. J Cell Biol. 1992;117:427–435. doi: 10.1083/jcb.117.2.427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helvering LM, Sharp RL, Ou X, Geiser AG. Regulation of the promoters for the human bone morphogenetic protein 2 and 4 genes. Gene. 2000;256:123–138. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Skillington J, Choy L, Derynck R. Bone morphogenetic protein and retinoic acid signaling cooperate to induce osteoblast differentiation of preadipocytes. J Cell Biol. 2002;159:135–146. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200204060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitching R, Qi S, Li V, Raouf A, Vary CP, Seth A. Coordinate gene expression patterns during osteoblast maturation and retinoic acid treatment of MC3T3-E1 cells. J Bone Miner Metab. 2002;20:269–280. doi: 10.1007/s007740200039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warren SM, Brunet LJ, Harland RM, Economides AM, Longaker MT. The BMP antagonist noggin regulates cranial suture fusion. Nature. 2003;422:625–629. doi: 10.1038/nature01545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob S, Wu C, Freeman TA, Koyama E, Kirschner RE. Expression of Indian Hedgehog, BMP-4 and Noggin in craniosynostosis induced by fetal constraint. Ann Plast Surg. 2007;58:215–221. doi: 10.1097/01.sap.0000232833.41739.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cooper GM, Curry C, Barbano TE, et al. Noggin inhibits postoperative resynostosis in craniosynostotic rabbits. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1046–1054. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Opperman LA, Nolen AA, Ogle RC. TGF-beta 1, TGF-beta 2, and TGF-beta 3 exhibit distinct patterns of expression during cranial suture formation and obliteration in vivo and in vitro. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:301–310. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1997.12.3.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sahar DE, Longaker MT, Quarto N. Sox9 neural crest determinant gene controls patterning and closure of the posterior frontal cranial suture. Dev Biol. 2005;280:344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lenton KA, Nacamuli RP, Wan DC, Helms JA, Longaker MT. Cranial suture biology. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2005;66:287–328. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)66009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.James AW, Xu Y, Wang R, Longaker MT. Proliferation, osteogenic differentiation, and fgf-2 modulation of posterofrontal/sagittal suture-derived mesenchymal cells in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:53–63. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31817747b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu Y, James AW, Longaker MT. Transforming growth factorbeta1 stimulates chondrogenic differentiation of posterofrontal suture-derived mesenchymal cells in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:1649–1659. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31818cbf44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.James AW, Xu Y, Lee JK, Wang R, Longaker MT. Differential effects of TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta3 on chondrogenesis in posterofrontal cranial suture-derived mesenchymal cells in vitro. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:31–43. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181904c19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James AW, Theologis AA, Bruggman SA, et al. Estrogen/estrogen receptor alpha signaling in mouse posterofrontal cranial suture fusion. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakamura T, Aikawa T, Iwamoto-Enomoto M, et al. Induction of osteogenic differentiation by hedgehog proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;237:465–469. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen MM., Jr Etiopathogenesis of craniosynostosis. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:507–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogston N, Harrison AJ, Cheung HF, Ashton BA, Hampson B. Dexamethasone and retinoic acid differentially regulate growth and differentiation in an immortalised human clonal bone marrow stromal cell line with osteoblastic characteristics. Steroids. 2002;67:895–906. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.St-Jacques B, Hammerschmidt M, McMahon AP. Indian hedgehog signaling regulates proliferation and differentiation of chondrocytes and is essential for bone formation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2072–2086. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.16.2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]