Abstract

Evidence-based practices to improve outcomes for children with severe behavioral and emotional problems have received a great deal of attention in children's mental health. Therapeutic Foster Care (TFC), a residential intervention for youth with emotional or behavioral problems, is one of the few community-based programs that is considered to be evidence-based. However, as for most treatment approaches, the vast majority of existing programs do not deliver the evidence-based version. In an attempt to fill this gap and improve practice across a wide range of TFC agencies, we developed an enhanced model of TFC based on input from both practice and research. It includes elements associated with improved outcomes for youth in “usual care” TFC agencies as well as key elements from Chamberlain's evidence-based model. The current manuscript describes this “hybrid” intervention - Together Facing the Challenge - and discusses key issues in implementation. We describe the sample and settings, highlight key implementation strategies, and provide “lessons learned” to help guide others who may wish to change practice in existing agencies.

Keywords: Therapeutic Foster Care, Evidence Based Practice, Changing Practice, Implementation of Evidence Based Practices, Train the Trainer

Introduction

There has been a great deal of attention in recent years to improving outcomes for children with severe behavioral and emotional problems by implementing “evidence-based practices” in children's mental health services (Brestan & Eyberg, 1998; Burns & Hoagwood, 2002; Chamberlain, et al, 2008; Chambless & Ollendick, 2001). Although the field has made significant gains toward developing and implementing evidence-based interventions, there is still a great deal to learn about the process (Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, & Wallace, 2005). The dissemination of evidence based practices into “real world” settings, which is the goal of translational science in mental health, depends on developing and refining processes that can move these practices into usual care (Brekke, Ell, & Palinkas, 2007). Central to the challenge of translational science in children's mental health services is the larger task of improving practice in usual care. The discussion of implementation of evidence based practices generally focuses on dissemination of the relatively few community-based treatments that are supported by multiple empirical studies. While such straight dissemination of evidence-based interventions will ultimately benefit the field, it does not address the larger and immediate issue of how to improve the overall quality of the many programs that are currently providing services to youth and families in “real world” settings. One of the promising areas for improving treatment in “usual care” settings is changing practice through focused training, consultation, and support for new and more “evidence-based” models of care (Dorsey et al. 2008).

Treatment foster care (TFC) provides an excellent example of this dilemma. The evidence base for TFC comes almost exclusively from research done by Chamberlain and colleagues in Oregon (e.g., Chamberlain, 1994; Chamberlain & Moore, 1998, Chamberlain & Reid, 1998; Eddy, Whaley, & Chamberlain, 2004; Leve & Chamberlain, 2005; Smith, Stormshak, Chamberlain, & Whaley, 2001). The evidence-based version of TFC, Multidimensional TFC (MTFC), (Chamberlain, 2002) is currently being disseminated in approximately 50 sites across the United States (mtfc.com). However, there are over 3500 agencies in the US that currently provide TFC to youth (Cole, personal communication). While the vast majority of existing agencies do not deliver the “evidence-based” version of MTFC (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000), treatment foster care is proliferating as a core service in community based interventions for youth with serious emotional disorders. Data from a recent state-wide study we conducted, suggests that many TFC agency directors are interested in improving practice within their sites and that there is clearly a need for such improvements (Farmer, Burns, Dubs, & Thompson, 2002).

We recently completed an NIMH funded randomized trial that will fill this gap by creating an enhanced model of TFC which is informed by evidence-based practice, but recognizes the limited reach of full evidence-based implementation to the myriad of potential ‘real-world’ sites. The intervention model we tested is an enhanced model of ‘usual care’ TFC, called Together Facing the Challenge. The goal of this randomized trial was to develop a model and approach that can be used in existing agencies in an attempt to improve overall quality of TFC. Our model brings together elements of the evidence-based model of MTFC with promising practices in “usual care” TFC to improve and enhance care in these existing agencies. Our intervention model was built around the goal of enhancing skills at both the treatment foster parent level as well as at the supervisory level in an effort to provide agencies with the tools needed to enhance their effectiveness. Specifically, the intervention was designed to increase (a) treatment parent skills, knowledge, and competence in the general areas of behavior management and (b) the TFC supervisors' ability to adequately support and guide these efforts.

The core of our implementation of the enhanced model was a ‘Train the Trainer” approach to changing practice (Stambaugh, Mustillo, et al., 2007). There is a tremendous need in community-based services to improve implementation toward more empirically-supported treatment approaches if we are going to see improved treatment and outcomes for youth. Current conceptualizations of effective implementation and change recognize that stand-alone training is unlikely to lead to adequate uptake or implementation of improved practice. Rather, we need to provide more extended coaching and consultation to support the uptake of such improved treatments. Our recent work in TFC suggests the substantial potential to change practice in “real world” treatment settings. We describe in this paper the implementation of our model using the “Train the Trainer” approach and discuss the challenges and lessons learned in changing practice in “real world” settings.

Background

Treatment Foster Care (TFC) is a residential intervention for youth with mental health or behavioral problems. Trained treatment foster parents work with youth in their homes to provide a structured, therapeutic environment while also providing opportunities for the youth to live in a family setting and learn how to live, work, and get along with others (Chamberlain, 1994; Chamberlain & Mihalic, 1998). TFC is appealing to many mental health professionals, administrators, and policy makers for a variety of reasons. First, it provides the least restrictive treatment-based residential option for youth with serious mental health or behavioral problems, meaning that youth are able to experience as ‘normal’ an environment as possible, while still receiving the intensive treatment they need. Second, TFC has an established evidence base of research that shows positive outcomes for youth (Chamberlain, 1994; Chamberlain, 2002; Farmer, Mustillo, & Dorsey, 2004). Because very few community-based treatments for youth with mental health problems have empirical support in the research literature, TFC has a competitive advantage on this front. Third, TFC is substantially less expensive to provide than more restrictive residential options for youth (Farmer, Burns, Dubs, & Thompson, 2002). Therefore, TFC is appealing philosophically, has established data to show that it can produce positive outcomes for youth, and is more cost-effective in its delivery than other options for youth in out-of-home treatment. Given the promise of TFC, providers, policy makers, and payers in many parts of the country are enthusiastic about TFC as a core treatment option.

Key Factors in TFC

Findings from Chamberlain's research on TFC and previous research by our group on “usual care” TFC suggest key elements that are associated with better outcomes for youth (Chamberlain, 2002; Chamberlain, Leve, & DeGarmo, 2007; Chamberlain & Mihalic, 1998; Chamberlain & Reid, 1998; Chamberlain, et al., 2008; Farmer, Murray, Dorsey, & Burns, 2006). Central among these are (1) supportive, involved relationships between TFC supervisors and treatment parents; (2) effective use of behavior management strategies by treatment parents; and (3) supportive and involved relationships between treatment parents and the youth in their care. For all three of these domains, TFC in “usual care” shows much lower rates of implementation than Chamberlain's evidence-based model. Although nearly all treatment parents receive at least some training in using behavior management strategies (often during pre-service training), our findings, including data from conversations with agency personnel, suggested that treatment parents had difficulty applying these skills effectively and consistently to the youth in their care (Farmer, Murray, and Southerland, 2009). For example, when the treatment parents were initially interviewed about effective strategies for addressing problematic behavior, the majority responded that restricting or removing privileges was one of the most effective approaches. However, when asked about what they actually did in response to specific problem behaviors by the youth in their care, 80% reported using other strategies such as talking, discussing, warning, or reminding. Similarly, while agencies expected TFC supervisors to provide consultation and support to treatment parents, many of the TFC supervisors we worked with in our intervention stated that they were uncertain how to do this and did not have a clear agenda or idea of what to do during supervisory visits in the homes. Additionally, most TFC supervisors in “usual care” TFC meet with treatment parents only two times per month, and few of the treatment parents participate in any type of group or support meetings on a regular basis with other treatment parents (Farmer, et al., 2006).

Description of the Intervention

Together Facing the Challenge was an NIMH-funded randomized trial conducted in North Carolina, in order to determine if we could improve practice in these three critical domains, in usual care settings. Fifteen sites were randomized to either experimental or control conditions. The current description and discussion focuses on the intervention arm of the study and agencies randomized to the experimental condition (n=8). We only include those agencies in the intervention condition in this discussion. As part of a 24 month implementation of the enhanced model, a total of 85 agency TFC supervisors and 350 treatment foster parents were trained across the eight agencies. The intervention sites varied on a number of domains. One of the sites was public (run by the local mental health authority), 6 were private non-profits, and one was a private for-profit agency. The length of time the agency had been providing TFC services ranged from 2 to 15 years, while the number of licensed homes ranged from 13 to 100. The number of TFC supervisors trained per site ranged from 5 to 20, and the number of treatment parents per site ranged from 15 to 57.

Despite these differences in ownership and size, the general structure of the participating sites showed substantial similarity. Each site had supervisory level position(s) (generally an individual with masters-level training in social work or other relevant field) that provided oversight to BA-level staff who directly supervised the TFC families. (In the following sections, these BA-level staff are referred to as “TFC supervisors.”) Beyond this rather standard structure, however, the frequency, duration, and intensity of both on-going training and supervision varied greatly. Only 2 of the 8 sites reported having regularly scheduled trainings for TFC supervisors on an on-going basis. Supervision of the TFC supervisors (by the masters-level staff) also varied. Two sites held weekly group supervision, while the rest of the sites provided monthly supervision to the TFC supervisors, in either individual or group sessions. Supervision meetings were often held in conjunction with staff meetings and both administrative and clinical issues were covered during this time. The number of cases assigned per TFC supervisor also ranged widely, from 6 to 20.

Expectations pertaining to frequency and method of supervision contacts of the TFC supervisors with treatment families varied as well. Frequency of required contact for most agencies was twice a month, though a few agencies required contact to be more frequent (i.e., weekly) and others less frequent (i.e., monthly). The types of contact with families included in-home, telephone, case conferences, and school-related meetings. In addition, when asked to describe their treatment model, 4 of the 8 sites reported not using a specific model of care with their therapeutic foster care program. The identified models used at the other sites included; a resiliency model (n=2), behavior modification (n=1), and gentle teaching (n=1).

Characteristics of Treatment Parents and Youth

Among the agencies in the intervention, 136 families were enrolled. Treatment parents ranged in age from 22 - 77 (mean=48). In 91% of households, females identified themselves as the primary care provider for the TFC child. A majority of the treatment parents (78 %) were African American. Sixty percent of treatment parents were married, 29% were divorced or widowed, and 11% had never been married. In terms of educational background, 29% had a high school diploma or less, 49% had some college, 16% had a college degree, and 6% had attended some level of graduate school.

Enrolled youth in the intervention sites ranged in age from 2-21 years, with a mean age of 13 (sd=3.8). The sample of youth was 51% female, 58% African American, 33% Caucasian, and 9% bi-racial or other ethnic/racial minorities. Youth entered their index TFC setting from a variety of other placements, including their family's home (24 %), another TFC home (36 %), group home (20 %), traditional foster care (8 %), while the other 12% came from a myriad of other placements. According to agency records, the most common diagnoses of youth entering these TFC sites were Attention Deficit Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Agencies also reported that a majority of the youth being served had a history of significant physical and/or sexual abuse. Learning and school related problems were also noted, and the vast majority of youth had school performance and/or school related behavioral issues.

The Train the Trainer Approach

Developing an effective training program is a key component of successful implementation of evidence based practice into the larger field (Fixsen, et al., 2005). Previous research has shown that traditional didactic training is ineffective in producing changes in practice (e.g. Dixon et al., 1999). Multi-faceted training that includes lecture-based information, instructional videos or demonstration of new practices, practical examples, and opportunities for practice with behavioral response are significantly more effective in successfully implementing a change in practice (Torrey et al., 2001; Dixon et al., 1999: Torrey, Lynde, Gormal, 2005). Additionally, any new model should be designed to be implemented in a step-wise fashion (Torrey et al., 2005; Chamberlain, Price, Reid, & Landsverk, 2008), so that practitioners are able to practice one new method at a time rather than trying to effectively implement all new practices simultaneously (Newhouse, Dearholt, Poe, Pugh, White, 2005). A Train the Trainer approach to dissemination potentially has several advantages, including building in a structure for sustainability, adaptability, and relationship building (Orfaly, et al. 2005). We discuss the strategies we used in the implementation of our enhanced model, to improve skills at both the treatment foster parent level as well as at the supervisory level, in an effort to provide them with the tools needed to enhance their effectiveness in working with the youth in treatment foster care. In the following sections, we describe our process of implementing the intervention model, Together Facing the Challenge, in usual care TFC agencies. In particular, we highlight the components of the Train the Trainer approach we developed. Finally, we discuss lessons learned.

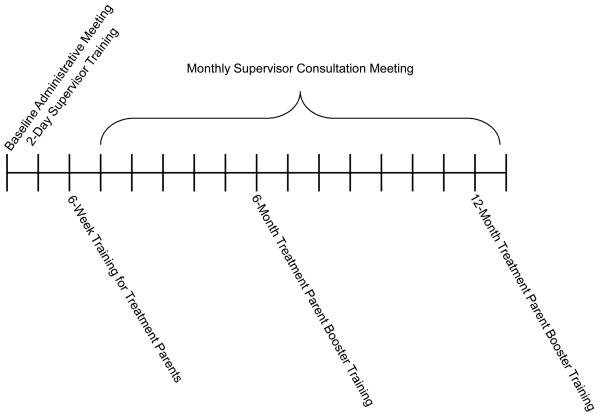

Training treatment parents in parent management strategies was a central part of the intervention component of the randomized trial (Farmer, 2002; Farmer, et al., 2006) and TFC supervisors were trained to support the treatment parents in implementing those strategies. The treatment parent training was built around a curriculum developed specifically for this intervention and is described in detail elsewhere (Murray, et al., 2007; Murray, 2006). In addition to training treatment parents, our implementation strategy centered on a Train the Trainer approach with TFC supervisors, which consisted of intensive in-person training (prior to training with the agency's treatment parents), and follow-up consultation, training, coaching and support with TFC supervisors and other agency staff involved with implementation of the model. This set of activities was based on the available literature on effective training approaches for changing practice among existing staff (Barwick et al., 2008; Chambers, 2008; Chorpita et al., 2002). As illustrated in Figure 1, the intervention agencies received (1) a two-day training for TFC supervisors; (2) 6-week training for treatment parents; (3) monthly consultation for TFC supervisors for one year following the initial training; and (4) booster sessions for treatment parents (at 6 and 12 months). University-based staff led trainings but efforts were made to involve TFC supervisors as co-facilitators and to train them as trainers for sustainability of the intervention. Data collection was conducted with treatment parents and youth across time at all sites. Details of data collection and outcomes are described elsewhere (see Farmer, Murray, & Dorsey, 2006; Farmer, et al., under review).

Figure 1.

Timeline of Together Facing the Challenge trainings and consultations, each tic on the line indicating approximately one month

Treatment Parent Training

The treatment parent training consisted of a structured 12 hour (6-session) curriculum developed to address the needs of treatment foster parents by teaching specific parenting strategies and techniques to use in their work with youth in TFC. The training has six components (see Table 1 for brief description).

Table 1.

Description of Treatment Parent Training Components

| Session Titles | Discussion Topics | |

|---|---|---|

| Building Relationships and Teaching Cooperation |

|

|

| Setting Expectations |

|

|

| Use of Effective Parenting Tools to Enhance Cooperation |

|

|

| Implementing Effective Consequences |

|

|

| Preparing Kids for the Future |

|

|

| Taking Care of Self |

|

|

For the majority of sites, trainings with treatment parents occurred over a six week period, with one session each week. Training sessions were usually held in the evening and dinner and child care were provided. Although adaptations to this structure were made (e.g. delivering the training over the course of two, day-long sessions to fit with a few agencies' preferred in-service training approach), the training seemed to be most effective when delivered once a week over a six week period. The weekly interval offered parents an ideal opportunity to practice the skills being presented in the training and to obtain feedback from the trainers about specific problems or issues faced while trying out some of the parenting strategies during the week. For example, one of the sessions focused on understanding conflict cycles and avoiding power struggles. As the more “seasoned” treatment foster parents were well aware, difficult child behaviors can wear down even the most skilled and caring caregivers. The importance of being aware of their own personal “buttons” and the potential impact during a power struggle situation was one of the many skill areas covered during the training. In addition participants were given specific techniques to help them cope during times of conflict. Teaching participants when and how to intervene in a conflict situation is an important skill that takes time to learn and develop competence. As one parent put it, “I learned that when I was in the middle of a conflict with my therapeutic foster child and both he and I were getting heated, I could take a time out as well.” Practicing the newly acquired skills was an integral component of the training. As part of the Train the Trainer approach, it was highly recommended for TFC supervisors to follow-up with their families between sessions to prompt, encourage, and coach families as they were learning these new strategies.

Booster sessions for treatment parents

In addition to the initial intensive training, booster sessions for treatment parents were conducted at 6 months and one year post initial training. These sessions were designed to offer additional training in specific content from the curriculum that had been identified by both staff and treatment foster parents as being in need of further review and practice. This training was conducted as an evening session and, like the initial training, included a meal and child care.

TFC supervisor Training

The TFC supervisors received 12 hours of training prior to training sessions held for their treatment parents. The initial 2-day training led the TFC supervisors through an accelerated version of the parent management training that would be done with their treatment parents and laid the foundation for our partnership with them. The TFC supervisor training was used as an opportunity to engage these individuals in the strategies and techniques that their treatment parents would be trained in and to prepare them to work intensively with their treatment families in implementing these approaches. One of our goals was to provide TFC supervisors with the needed information and training to enable them to co-facilitate upcoming training sessions with their treatment families (e.g., take the lead in role-plays, provide leadership for “break out” exercises, work with treatment parents on homework assignments, etc.).

Follow-up consultation

Follow-up consultation with TFC supervisors was a critical component of the Train the Trainer approach. These sessions began when the treatment parent training ended and continued for one year. The goal of this component was to teach, support, and coach TFC supervisors as they worked with their assigned families. The consultation consisted of monthly in-person or phone conferences with each agency. Whenever feasible, in-person consultation sessions were conducted. These in-person sessions proved to be a very valuable part of our implementation approach, even if it required significant travel to sites. What may have been lost in efficiency (due to travel time) was made up for in the effectiveness of the time spent together. These meetings were generally an hour in length and the agenda was tailored to meet the individual needs of each group. Some of the covered topics included revisions to in-service training offered at various sites to enhance treatment parent attendance and participation, development of a structured protocol for home visit meetings, case consultation with a focus on problem solving barriers to challenging youth and family situations, and planning for organizational level training and supervision needs. In addition TFC supervisors were encouraged to e-mail or call between scheduled meetings for consultation or support as needed.

This follow-up work was necessary in order to facilitate the process of putting the enhanced model of care into “practice as usual.” Regularly scheduled in-person meetings and phone calls helped to prevent potential problems from becoming insurmountable barriers to implementation. The consultation offered a forum for on-going dialogue with the TFC supervisors and provided a means for them to process issues and concerns they experienced as they tried to assist their treatment families in implementing the various skills and techniques presented in the treatment parent training. Once the initial training for treatment parents and their TFC supervisors was completed, the next challenge faced was dealing with how to be most effective and efficient in working to reach the ultimate goal of changing practice within existing programs.

Lessons Learned

Making change within an existing organization is a very challenging task. We learned several lessons from our experiences with implementing the enhanced TFC model in these “real world” agencies. There are many curricula, programs, and frameworks that could potentially benefit existing agencies. The content has to be well-designed, relevant, in line with current agency goals, etc. However, the process by which an agency is approached and worked with is possibly more important than the exact content of any new curriculum, program, or philosophy in determining whether the agency will be receptive and attempt to implement the changes. Based on our experience, and previous literature on implementing evidence based practice in real world settings (Chorpita, Yim et al. 2002; Chambers, Ringeisen et al. 2005) and changing organizational culture (Glisson & Shoenwald, 2005), we identified four topic areas where critical issues emerged in the process of working with the various intervention sites: (1) Engagement, (2) Roles and Responsibilities, (3) Culture, and (4) Coaching. These four topic areas were identified through an iterative process of review and revision of our training approach by our intervention research team. We expect that explication of our lessons learned in these areas will be useful to others who are attempting to change practice.

Engagement

Establishing a core training group within each site was critical in enabling agencies to provide training to new staff and treatment foster families while providing routine follow-up to the existing staff and families. Although the composition of these training groups varied based on the individual sites and resources available, the staff person overseeing and supervising the TFC supervisors typically provided the group's leadership. Other key participants often included the agency trainer and one or two TFC supervisors identified by the administrative staff as central members of the team. This Train the Trainer approach was viewed as a viable method of sustaining the training over time and incorporating it into “practice as usual.”

Informal time spent getting to know the staff, becoming familiar with their organizational culture, and learning how to work with their established structures was important in smoothing the way for bringing change to an agency (Glisson & James, 2002). Before beginning to work with each organization, we first met with the upper-level administrators to explain the study and intervention process to them, learn more about their agency and current practices, and give them an opportunity to ask questions, suggest ways to effectively work with their staff, etc. After this, we had a group meeting with the TFC supervisors. Again, we explained the study, asked about how they currently did their job, and solicited their input on a variety of topics (e.g., current practices, challenges in their work, things that were working well, what they'd like to see changed, etc.) to begin building a relationship and dialogue. The initial meetings were vital for establishing a sense of shared mission and understanding and for beginning to develop rapport between the research/training team and the agency. We found that senior research/training staff who had extensive experience in the field should take the lead in these early meetings. The credibility and acceptability of the trainer to the agency staff in the early stages of relationship building was critical (Torrey et al., 2005). It was important for the individuals who conducted these initial meetings to show their familiarity with the field, challenges, potential, etc. of TFC.

The initial stage of establishing and building relationships with staff at individual agency sites was crucial in providing the foundation for ongoing collaboration. The “up front” time spent in getting to know the staff at each site was well worth the effort. We learned the importance of providing support at both the direct staff and administrative level. Although we had the advantage of having a previously established relationship with many of these agencies, maintaining those ties continued to be a very important factor in effectively implementing the curriculum. This level of intervention within a “usual care” setting required a significant amount of time, energy, and commitment on the part of each agency staff member. Our goal was to train the TFC supervisors, then offer them continuing support through the consultation approach in an effort to sustain the intervention once the study came to an end.

Staff engagement, however, was not an up-front-only activity, it was ultimately about relationships. Like any relationship, it required consistent effort, attention, and prioritizing. Also like any relationship, engagement occurred at different rates for different participants. In some agencies, from our initial meetings forward, we felt welcomed, embraced, and as though the agency had been long-hoping for the type of training and support we could provide. In other agencies, initial meetings were more reserved with staff asking more pointed questions, showing less enthusiasm, and generally suggesting that their willingness to commit to the effort involved in this project was not yet certain. As we moved through the project, it was evident that this initial level of enthusiasm, warmth, or receptivity was not a reliable indicator of either our long-term relationship with the agency or with their ability to implement the program. Initial enthusiasm and welcome was wonderful, but it did not mean that the work of relationship building was completed. Additionally, lack of overwhelming support at initial meetings did not mean that the agency was resistant, difficult, or unenthusiastic. Rather, initial impressions were just that. Initial meetings were essential for beginning to create a sense of partnership with the agency and make it clear that the agency staff and the research/training staff were collaborators in what was to come. They also provided the opportunity to learn about the agency's program, gauge initial enthusiasm, and provide information for subsequent approaches (discussed below).

Roles and Responsibilities

As we approached agencies, we asked questions about how things were currently done, using both structured and unstructured interview techniques. In this process, we expected to learn who played what role, how the various roles and inhabitants interacted with each other, and who was responsible for what. One thing we learned is that this often was not clear to agency staff members. In some sites staff could clearly articulate their job duties, while in other sites staff appeared perplexed and unsure about their role and how to carry it out. The staff who reported confusion and uncertainty about their position tended to be staff within sites that also reported having limited (if any) individual supervision time or opportunities for enhancing their clinical skills through on-going training and consultation. An exercise wherein staff defined their roles to the consultant was a great starting point to help them define these roles for themselves and their colleagues. During this exercise the true roles that each person took on within the agency (as opposed to the stated roles) began to emerge. The outcome of this exercise became an important reference point for role clarification during all phases of the intervention.

An important role that was identified early in the implementation of the practice model is that of staff champions. As “outsiders,” in this case the trainers/consultants who led the change process, we found it very useful to identify one or more people who have characteristics that allow them to be seen as champions for change within the organization. Those were the folks who got very enthusiastic about change and were the “person on the ground.” For them change was exciting and offered an opportunity to try out new ideas and strategies. They tended to be optimistic and full of energy. It was important that this person or persons not be seen as ‘just someone who likes change for change's sake’, but also was seen by others as a natural leader. They did not have to have a formal leadership role, but had to be someone who was respected and looked up to and/or sought out informally by others (i.e., enacting a leadership role). Identifying this person early in the process and in some way affording them leadership status, whether formal or informal, was very helpful in the implementation process. The best way to locate such individuals is simply by asking – we found that it didn't take long to identify these individuals, they generally emerged early in the process. We typically ascertained this information during informal meetings with agency directors or other administrative level staff within each of our sites.

Culture

Creating a culture in order to work together within the agency sites was a critical component in the change process. The goal was to integrate the process of change into the activities of the agency so that the staff came to see the changes as part of the “new normal.” For instance, monthly meetings were scheduled in advance, placed on the agenda, held at the same time each month and became a routine part of the work schedule. In addition to soliciting feedback from TFC supervisory staff prior to each meeting, a written agenda was used to help keep on track and ensure the group that all agenda items would be addressed. It was important for staff to see this meeting as distinct from their other staff meetings, which focused more on administrative related tasks and responsibilities. One strategy used to set this meeting apart was the development of rituals. Refreshments provided during these meetings were just one example of things done to create a unique atmosphere at each site. Sharing food together also helped facilitate the process of getting to know one another as we began to build a working partnership. Unlike administrative meetings, our sessions were heavily focused on treatment related issues, concerns, and needs. We encouraged the groups to use problem-solving methods including peer feedback to deal with barriers faced in their efforts to fully implement the enhanced practice model.

Getting staff buy-in was an important foundation for creating the change in culture necessary to change practice. Previous work has shown that without buy-in and strong cooperation from the staff, implementation is likely to fail (Fixsen, et al., 2005; Glisson and Schoenwald 2005). Making a change in practice took time and effort on the agency staff's part, and therefore, it was very important for them to see the change as something that would hold value to them, not just “one more thing” to add to an already full workload. Giving recognition to staff for the many challenges faced in fulfilling their role while simultaneously helping to facilitate the atmosphere for change within the organization was a delicate balancing act which was a critical element in the implementation process. Some of the strategies we used included offering staff and families not only the opportunity to ask questions but also eliciting input from them about their specific concerns, issues, and needs. We asked treatment parents to complete questionnaires in a confidential and anonymous manner. We wanted them to feel comfortable sharing their thoughts, feelings, and concerns with us about their role as a TFC parent without having concerns whether or not the agency would have access to it. The questions pertained to the quality of the relationship between the treatment parent and their agency TFC supervisor, most challenging and satisfying aspects of their role, and specific feedback for improving the overall quality of TFC. This information was then used to assist the lead trainer in their on-going consultation with agency staff.

As the intervention began moving forward, meetings with staff were scheduled to learn more about the individual sites and the infra-structure in place to assess how to most effectively intervene. Although agency staff often reported already using many of the parenting skills and strategies presented in the training, they also reported that prior to the training what was missing had to do more with the lack of a cohesive infra-structure to ensure that everyone working within the agency (both staff and treatment foster parents) received the same level of training and that a systematic approach to implementing specific parenting strategies and techniques be in place to ensure both consistency and adherence to the model. One agency TFC supervisor put it this way, “now we have more of a foundation by providing us with a common language in which to work together.”

Coaching

On-going supervision, coaching and support were central to enhancing skills of TFC parents. Likewise, it was a critical component of the Train the Trainer approach to sustaining the new program. A typical area in which agencies struggled was in providing on-going coaching for staff, particularly the TFC supervisors involved in working directly with TFC families. In the intervention agencies, the TFC supervisor tended to be relatively inexperienced or ‘green’ and frequently fairly new to the mental health field. Despite some formal pre-service training, consisting of reading through some type of manual and getting instruction on the “ever-dreaded” paper work, there was minimal formal training conducted with this level staff, particularly about how to engage and work with families in an effective manner. Often shadowing more experienced staff was the extent of on-the-job training for these positions. Although the use of shadowing trained staff was an effective learning approach, it seldom seemed to be integrated into a more comprehensive training curriculum. Often the shadowing occurred as a pre-service activity, a time when newly hired TFC supervisors were already experiencing information overload. It would be beneficial to continue this type of training on an ongoing basis. We were struck by the limited training offered to the TFC supervisors on a regularly scheduled basis, and more importantly, the limited coaching offered (training being the presentation of new material, and coaching being the opportunity to reflect on previously learned material to improve practice). Along the same line, TFC supervisors tended to have minimal structured and regularly scheduled supervisory meetings with their TFC supervisor to provide on-going feedback, guidance, and support in their work with youth and families in TFC. To overcome this potential obstacle, we created structure by implementing regularly scheduled meetings specifically designed to focus on the treatment aspect of their work with youth and families in TFC. Hence, we provided some of this needed supervision temporarily and modeled such supervision as an expected part of the “new normal.”

As a parallel to the paucity of training offered to TFC supervisors, we also observed similar needs with treatment parents. Unlike the TFC supervisors who received very little training when they started their job, the vast majority of TFC treatment parents received extensive pre-service training (for licensure) which, for the most part, TFC supervisors were not involved in. Once a child was placed in the home, however, the system of training seemed to break down. Agencies varied greatly in the frequency and content of on-going training offered to treatment parents, and most of the sites reported low attendance rates even when it was offered. Even for those families who were offered frequent and high quality training, the opportunities for in-vivo coaching were very limited. Given what is known about effective use of behavior management strategies as one of the key variables related to positive outcomes for youth in care (Pacifici, Chamberlain, & White, 2002; Patterson & Forgatch, 1987), it was essential that on-going training to enhance clinical skills be an integral component of the services provided to TFC supervisors and treatment foster families. This cannot be done in occasional, didactic training, but can only be done when the training is followed-up by regular coaching, a format we rarely saw even in the more mature, higher quality agencies.

A critical component of coaching is that much of it occurs in-vivo. In addition to providing agency staff with on-going feedback during the regularly scheduled follow-up consultation sessions, we also had opportunities to observe TFC supervisors conducting home visits with some of their treatment foster families. This provided an opportunity to model good coaching as a TFC supervisor. Also, these in-vivo experiences provided the TFC supervisors with a forum to reflect on their work with families, receive feedback, and problem-solve specific areas of concern or need. The ongoing supervisory meetings we provided, which focused on behavior management strategies, better prepared the TFC supervisors to offer training, consultation, and coaching to the families they serve during home visits. Home visits provided an ideal opportunity to practice and fine-tune the skills through on-going coaching (the follow-up to the training). They also provided an ideal way to assess first hand how things are going both for the treatment foster family and the child.

Meeting with families in their home was a central component of implementing our enhanced TFC model. Frequent in-person contacts scheduled on a regular basis can provide families with the needed support, guidance, and oversight to assist them in working more effectively with the youth in their care. We found great variability in terms of frequency, duration, content, and the format being implemented both with-in and across agency sites. Feedback received from one administrator included a need for a more structured format to the sessions and more of a focus on treatment related planning and intervention. On the other hand the feedback from several of the TFC supervisory staff focused on the need for more training and consultation to help them be more effective in carrying out the desired goals of the home visits. As a result of feedback received, we developed (in collaboration with agency staff) a form for TFC supervisors to use during in-home sessions with treatment foster parents. This form, titled the Bi-weekly Behavior Update Report, led the TFC supervisor in helping families identify and describe specific/identifiable positive and problem behaviors to be addressed, plan interventions and strategies to target those behaviors, assess effectiveness of interventions implemented, and identify future steps to be taken to reach the desired behavior outcome. It also provided a format for following up on progress in subsequent home visits.

Discussion and Implications

Making change within an existing organization can be a daunting proposition. Whether the change is seen as positive or negative, change in itself tends to be challenging both on an individual and a systems level. In our experience we found several factors that either inhibited or enhanced our ability to successfully implement the intervention across sites. One of the key variables that facilitated our efforts to create change within a given agency was our focus on developing strong working relationships with staff at all levels of the organization. Some of the strategies we found most effective included informal visits spent getting to know staff, learning about the organizational hierarchy and structure of each site and how to effectively intervene, finding frequent opportunities to reinforce and praise staff, and creating a unique atmosphere or culture with a focus on collaboration and support. The upfront time and attention spent in ‘relationship building’ was time well spent as it provided the foundation for our working partnership. During the implementation phase of our study, we identified a pattern among our sites in relation to staff roles, responsibilities, and training. On a whole there appear to be minimal resources set aside to provide TFC supervisors with the level and degree of training, supervision, coaching, and support needed to carry out their work with youth and families on their caseload.

The work described here was an initial attempt to improve practice in “usual care” TFC agencies. Findings from this research supported that the approach utilized here can result in improved youth-level outcomes (symptoms, behaviors, strengths) (Famer et al., under review). However, they also indicated the need for additional work to produce the full range of desired changes. To more fully assess how change is progressing, we have been developing a measure of fidelity of implementation of the enhanced TFC model. Such a measure will provide research-relevant data on degree and domains of change as well as provide ongoing in-house assessment for program delivery and quality improvement.

Improving practice in existing agencies is a critical part of improving the overall quality of treatment for children. Our paper examined the format and implementation of such an approach with a variety of “real world” TFC agencies. Findings illustrated the challenges faced in conducting this type of intervention, as well as the potential to both influence and change practice. Overall, the process and results of this effort suggested the substantial potential to improve practice even in sites that are not involved in dissemination of current evidence-based interventions. It also suggested the effort, resources, and commitment required by agencies and staff to do so. Such change is not easy, but it is possible and potentially beneficial and rewarding with gains for agencies, staff, families, and youth.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (MH057448)

References

- About MTFC: Current sites. (n.d.). Retrieved November 10, 2008, from http://www.mtfc.com/currentsites.html.

- Barwick M, Boydell K, Stasiulis E, Ferguson HB, Blase K, Fixsen D. Research utilization among children's mental health providers. Implementation Science. 2008;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brekke John S., Ell Kathleen, Palinkas Lawrence A. Translational Science at the National Institute of Mental Health: Can Social Work Take Its Rightful Place? Research on Social Work Practice. 2007;17:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Brestan EV, Eyberg SM. Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:180–189. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2702_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns BJ, Hoagwood K, editors. Community treatment for youth: Evidence-based interventions for severe emotional and behavioral disorders. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. Family connections: A treatment foster care model for adolescents with delinquency. Castalia Publishing Company; Eugene, OR: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P. Treatment foster care. In: Burns BJ, Hoagwood K, editors. Community treatment for youth: Evidence-based interventions for severe emotional and behavioral disorders. Oxford University Press; New York: 2002. pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Leve LD, DeGarmo DS. Multidimensional treatment foster care for girls in the juvenile justice system: 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:187–193. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Mihalic SF. Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care. In: Elliott DS, editor. Book eight: Blueprints for violence prevention. Institute of Behavioral Science, University of Colorado at Boulder; Boulder, CO: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Moore K. A clinical model for parenting juvenile offenders: A comparison of group care versus family care. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998;3:375. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Leve LD, Laurent H, Landsverk JA, Reid JB. Prevention of behavior problems for children in foster care: Outcomes and mediation effects. Prevention Science. 2008;9:17–27. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0080-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Price J, Reid J, Landsverk J. Cascading implementation of a foster and kinship parent intervention. Child Welfare. 2008;87:27–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain P, Reid J. Comparison of two community alternatives to incarceration for chronic juvenile offenders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:624–633. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers D. Advancing the science of implementation: A workshop summary. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:3–10. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Ringeisen H, Hickman EE. Federal, state, and foundation initiatives around evidence-based practices for child and adolescent mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:307–327. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless DL, Ollendick TH. Empirically supported psychological interventions: Controversies and evidence. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001;52:685–716. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Yim LM, Donkervoet JC, Arensdorf A, Amundsen MJ, McGee C, et al. Toward large-scale implementation of empirically supported treatments for children: A review and observations by the Hawaii Empirical Basis to Services Task Force. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2002;9:165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon L, Lyles A, Scott J, Lehman A, Postrado L, Goldman H, et al. Services to families of adults with schizophrenia: From treatment recommendations to dissemination. Psychiatric Services. 1999;50:233–238. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey S, Farmer EMZ, Barth RP, Greene KM, Reid J, Landsverk J. Current status and evidence base of training for foster and treatment foster parents. Children and Youth Services Review. 2008;30:1403. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddy JM, Whaley RB, Chamberlain P. The prevention of violent behavior by chronic and serious male juvenile offenders: A 2-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2004;12:2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EM, Burns BJ, Murray M, Wagner R, Southerland D. Improving outcomes in TFC: Effects of a randomized trial. Psyciatric Services. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.6.555. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EM, Burns BJ, Dubs MS, Thompson S. Assessing conformity to standards for treatment foster care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2002;10:213–222. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Dorsey S, Mustillo SA. Intensive home and community interventions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:857–884. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Murray M, Dorsey S, Burns BJ. Enhancing and adapting treatment foster care. In: Newman CC, Liberton CJ, Kutash K, Friedman RM, editors. The 18th Annual Research Conference Proceedings, A System of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base; The Research and Training Center for Children's Mental Health; Tampa. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EM, Murray M, Southerland D. Together facing the challenge: Preliminary findings from a randomized clinical trial of therapeutic foster care; Symposium conducted at the meeting of the 22nd Annual Research Conference, A System of Care for Children's Mental Health: Expanding the Research Base; Tampa, FL. 2009, March. [Google Scholar]

- Fixsen DL, Naoom SF, Blase KA, Friedman RM, Wallace F. Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. Louis de la Parte Florida Mental Health Institute, National Implementation Research Network; Tampa, FL: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, James LR. The cross-level effects of culture and climate in human service teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2002;23:767–794. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK. The ARC organizational and community intervention strategy for implementing evidence-based children's mental health treatments. Mental Health Services Research. 2005;7:243–259. doi: 10.1007/s11020-005-7456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leve LD, Chamberlain P. Association with delinquent peers: Intervention effects for youth in the juvenile justice system. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M. Together Facing the Challenge: Effective Training for Treatment Foster Parents; Presented at Foster Family-Based Treatment Association (FFTA); 20th Annual Conference on Treatment Foster Care; Pittsburgh, PA. July, 2006.2006. [Google Scholar]

- Murray M, Dorsey S, Farmer EMZ, Potter E, Burns BJ, Kelsey KL. Together Facing the Challenge: A Therapeutic Foster Care Resource Toolkit. Services Effectiveness Research Program, Duke University Medical Center; DUMC Box 3454, Durham, NC 27710: 2007. Available from the. [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse R, Dearholt S, Poe S, Pugh LC, White K. Evidence-based practice: A practical approach to implementation. The Journal of Nursing Administration. 2005;35:35–40. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200501000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orfaly RA, Frances JC, Campbell P, Whittemore B, Joly B, Koh H. Train the Trainer as an Educational Model in Public Health Preparedness. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice. 2005;11:S123. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200511001-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici C, Chamberlain P, White L. Off road parenting: Practical solutions for difficult behavior. Northwest Media Inc; Eugene, OR: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Forgatch MS. Parents and adolescents living together: Part 1: The basics. Castalia Publishing Co; Eugene, OR: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Rones M, Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DK, Stormshak E, Chamberlain P, Whaley RB. Placement disruption in treatment foster care. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2001;9:200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Stambaugh Leyla F., Mustillo Sarah A., Burns Barbara J., Stephens Robert L., Baxter Beth, Edwards Dan, Dekraai Mark. Outcomes from Wraparound and Multisystemic Therapy in a Center for Mental Health Services System-of-Care Demonstration Site. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2007;15:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Torrey WC, Drake RL, Dixon L, Burns BJ, Flynn L, Rush AJ. Implementing evidence-based practices for persons with severe mental illnesses. Psychiatric Services. 2001;52:42–50. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey WC, Lynde DW, Gorman P. Promoting the implementation of practices that are supported by research: The national implementing evidence-based practices project. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2005;14:297–306. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]