Abstract

Objective

The effect of zinc and glutamine on brain development was investigated during the lactation period in Swiss mice.

Methods

Malnutrition was induced by clustering the litter size from 6–7 pups/dam (nourished control) to 12–14 pups/dam (undernourished control) following birth. Undernourished groups received daily supplementation with glutamine by subcutaneous injections starting at day 2 and continuing until day 14. Glutamine (100 mM, 40–80μl) was used for morphological and behavioral studies. Zinc acetate was added in the drinking water (500 mg/L) to the lactating dams. Synaptophysin (SYN) and myelin basic protein (MBP) brain expressions were evaluated by immunoblot. Zinc serum and brain levels and hippocampal neurotransmitters were also evaluated.

Results

Zinc with or without glutamine improved weight gain as compared to untreated, undernourished controls. In addition, zinc supplementation improved cliff avoidance and head position during swim behaviors especially on days 9 and 10. Using design-based stereological methods, we found a significant increase in the volume of CA1 neuronal cells in undernourished control mice, which was not seen in mice receiving zinc or glutamine alone or in combination. Undernourished mice given glutamine showed increased CA1 layer volume as compared with the other groups, consistent with the trend toward increased number of neurons. Brain zinc levels were increased in the nourished and undernourished-glutamine treated mice as compared to the undernourished controls on day 7. Undernourished glutamine-treated mice showed increased hippocampal GABA and SYN levels on day 14.

Conclusion

We conclude that glutamine or zinc protects against malnutrition-induced brain developmental impairments.

Keywords: malnutrition, hippocampus, stereology, ontogeny behavior, suckling mice

INTRODUCTION

The human and rodent brain development relies in great part on post-natal plasticity, especially within highly dynamic brain regions such as cerebellum, hippocampus and neocortex [1]. Nutritional insults during the first weeks of life in rodents (somewhat analogous to the first two years in humans) can delay the acquisition of early motor reflexes [2], with associated deleterious effects in the cerebellum, mostly related to zinc deficiency [3]. Specific behavioral impairments due to nutritional deficits, during the first weeks of life, such as iron-deficiency, might be retained even when these animals reach adulthood [4].

In our previous cohort studies of children living in impoverished Brazilian urban areas, we have shown a reciprocal “vicious cycle” between malnutrition and diarrheal illnesses with lasting physical and cognitive impairments, which are sustained into schooling age [5-7].

The pursuit of selective and time-effective nutritional interventions to ameliorate these deficits is critical to rescue, as much as possible, the normal course of child development. Zinc and glutamine are considered critical gut-trophic nutrients, which have protective roles, as demonstrated in various animal models of intestinal injury [8] and have been proved to be beneficial in clinical studies enrolling children afflicted with malnutrition and diarrhea in the developing world [9]. The recovery of the intestinal barrier function following nutritional therapy might improve the supply of brain-related nutrients (iron, fatty acids and zinc) during critical time-windows of brain development.

Thus, the aim of this study was to evaluate the role of zinc and glutamine treatment, alone or in combination, in preserving the hippocampus morphology, with emphasis on the CA1 region, following early post-natal malnutrition, as assessed by unbiased stereological methods. The value of stereological analyses for understanding histological alterations in the hippocampus has been extensively highlighted [10]. In addition, we followed the ontogeny of some motor reflexes during the first two weeks of life in mice to test the hypotheses that the effect of glutamine and zinc on brain morphological and biochemical changes would correlate with improved behavioral function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Malnutrition and treatment

Swiss mice were obtained from the Federal University of Ceara (UFC) vivarium and were housed in breeding pairs with free access to standard chow diet and water in a temperature-controlled room. Pregnant mice were transferred to individual cages until delivery. All behavior tests were conducted in a silent room (14:00–16:00h), under 12h light/dark cycle. Study protocols were in accordance with the Brazilian College for Animal Care (COBEA) guidelines and were approved by the UFC Animal Care and Use Committee. Malnutrition was induced by clustering the litter size (undernourished group, 12 to 14 pups per litter, and the nourished group with seven to eight pups per litter, since birth) during the first two weeks. The undernourished groups received daily supplementation with glutamine (100 mM) by subcutaneous injections (40μl during days 4–8 and 80μl during days 9–14), starting at day two until day 14. Zinc acetate was added in the drinking water to the lactating dam in a concentration of 500 mg/L during the periods of lactation, which has been shown to be beneficial to the offspring immune system during the suckling time [11]. Therefore, we defined the following supplemented groups: glutamine + PBS; zinc acetate + PBS; glutamine + zinc acetate (the latter given to the dams in their drinking water and presumably transferred to the pups by the breast-milk). The dose of glutamine (100 mM) was chosen based on a dose-response curve (50, 100 and 200 mM) during the first two weeks (data not shown). Untreated nourished and undernourished groups received only PBS. Growth was monitored daily by recording tail length and body weight gains. Effort was made to keep the same degree of handling for all experimental groups. Although a gender effect is unlikely to constitute a strong factor in newborn mice, litters with high deviations from 1:1 ratio were not included in this study.

Behavioral studies

Behavioral studies, including cliff avoidance and swimming behaviors were conducted in the first two weeks of life and scored as described elsewhere [12,13]. The cliff avoidance reflex test [14,15] is used to assess the integration of exteroceptive input (vibrissae) and locomotor output, providing information concerning physical and motor development as well as sensory function and/or processing. The offspring is placed on a platform elevated 10 cm above a table top. The forelimbs and snout of the animals are positioned so that the edge of the platform passes just behind an imaginary line drawn between the eye orbits. Avoidance is scored by reflex latency between being placed on the edge and turning until it is parallel to the edge of the table (0= no response, latency > 60s; 1= <15 s; 2 <10 s; 3 < 5 s). The swimming behavior test is used to assess navigational and motor development. The offspring is placed into a tank with water temperature maintained at 27 ± 1°C and swimming behavior is rated for direction (straight = 3, circling = 2, floating = 1) and head angle (ears out of water = 4, ears half out of water = 3, nose and top of head out of water = 2, and unable to hold head-up = 1). Limb movement is rated as either 1 = all four limbs used, or 2 = hind limbs only used.

Stereology

Tissue sampling and sectioning

A total of 19 male Swiss mice (5–10g) were used in this protocol. Brain tissue was collected at day 14 (the end point), following a trans-cardiac perfusion-fixation with Palay’s solution (containing 1% formaldehyde and 1% glutaraldehyde in 0.12 M phosphate buffer at pH 7.2) [16] and immediately immersed in the same solution for stereological analyses.

After euthanasia the hippocampus was dissected out from the brain and halved. Each hemi-hippocampus was systematically, uniformly and randomly selected (SURS) [17] between left and right and weighed. Subsequently, the selected hemi-hippocampus (left or right) was manually straightened along its septotemporal axis to diminish the anatomical organ curvature.

Subsequently, the straightened hippocampus was embedded in a 10% agar solution and exhaustively cut into a thin section (100μm-thick) followed by a thick section (1 mm-thick), alternately and using a vibratome (VT 1000 S (Leica®, Wetzlar, Germany) [18]. Sections were orthogonal to hippocampus’ long axis and a fraction (10−1) of those paired sections (thin and thick section) was SUR selected. The average interval (K) between the section pairs was 400μm. Thin sections were collected onto glass slides, stained with an 1% alcoholic toluidine blue solution, dehydrated in progressive ethanol concentrations, mounted under a coverslip with DPX (Fluka®, Buchs, Switzerland) and used not only to record the exact position of CA1 layer in the hippocampus, i.e. mapping sections [18], but also for the estimate of post-embedding hippocampus and CA1 layer volumes using Cavalieri’s principle.

Thick sections were used to produce vertical, uniform and random sections (VUR sections) [19]. First of all thick sections were positioned onto a transparent plate of Silgard® in the centre of a circle with 36 (360°) equidistant divisions along the perimeter. Next step, a random number between 0 and 36 was generated using a random number table (SURS) [18].

Subsequently, a transparent cutting guide containing lines was placed onto the thick section at the same selected angle. Finally, a razor blade was used to produce bars from the sections guided by the lines in the cutting guide.

Each bar containing hippocampus was rotated by 90° around the vertical axis to the sections and allowed for VUR sections parallel to the vertical axis. The bars from each section were then re-embedded in a 10% agar solution and exhaustively sectioned at 50μm-thick using a vibratome, i.e. mean block advance (BA) is 50μm.

Thick sections (from bars) were collected onto glass slides, stained with an 1% alcoholic toluidine blue solution, dehydrated in progressive ethanol concentrations, mounted under a coverslip with DPX (Fluka®) and they were therefore used to simultaneously estimate number and volume of the same CA1 neurons.

Section images were acquired using a Leica® DMR Microscope coupled with a Digital Camera PLA622 (Pixellink®) and a stereological software New Cast Visiopharm® (version 2.16.1.0). The area of the unbiased counting frame used was 5,000 μm2 [20]. Before starting the counting procedure, a z-axis distribution (calibration) was performed to know the neuron distribution throughout section thickness and establish the disector height, which was 20μm. Section thickness was measured in every second field of view using the central point on the unbiased counting frame. The neuron nucleus was defined as the counting unit.

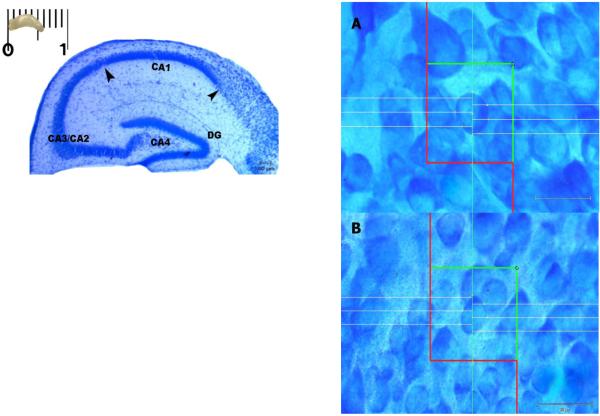

In this study the whole hippocampal structure including the granular cell layer of dentate gyrus (DG) and the pyramidal cell layer of CA1, CA2, CA3 was defined at all levels of sectioning according to the stereotaxic coordinates published elsewhere [21]. Hippocampus regions are represented in Fig. 1. The CA1 area of the hippocampus was chosen for further stereological analyses because it constitutes one of the simplest and most examined cortical areas and where recent progress has been made in explaining neuronal diversity and because of their highly intricate GABAergic interneuronal and glutamatergic principal circuitry supporting behavioral processing [22].

Figure 1.

Details of a hippocampus coronal section showing the whole layered-organ-structure. Arrow heads point CA1-layer limits. Because of the small dimensions of CA2 layer the latter was joined to CA3 pyramidal layer, named CA3/CA2. Toluidine blue. Scale bar: 100 μm. Cell volume differences between (A) undernourished (B) nourished mice. CA1 cells undergo a malnutrition-related hypertrophy. White lines show the application of six-line vertical rotator. Toluidine blue. Scale bar: 20 μm for panels A and B.

Hippocampus Volume: V (HIP)

Hemi-hippocampus fresh weight was converted into volume to estimate tissue shrinkage. The formula used was: V(volume) = m(mass)/d(density). The specific density (d(density)) was 1.04 g . cm−3 [18]. In the results we have reported the bilateral volume which was elicited multiplying V (HIP) by 2 since the left or right hemi-hippocampus was SUR sampled [17].

Volume of CA1 layer: V (CA1) and V(HIPpost-emb)

The volume of CA1 layer and the post-embedding volume of the selected hemi-hippocampus were estimated using the Cavalieri principle on the thin sections (100μm-thick). Then, V (CA1) or V(HIPpost-emb) := ΣP · ap · BA · K , where P is the number of test points hitting the tissue (CA1 or the whole hippocampus) (we have used on average 100 (CA1) and 200 (HIP) points per animal), ap is the area associated with each test point, BA is the mean block advance (or mean section thickness= 100 μm) and K is the distance between the sections sampled.

The error variance of Cavalieri’s estimator (CE) was estimated according to [23]. Therefore, the error variance of Cavalieri’s estimate was 0.04 for group 1, 0.04 for group 2, 0.03 for group 3, 0.03 for group 4, and 0.04 for group 5.

The volume shrinkage was then calculated as: Volume shrinkage = 1 – volume after: volume before [18].

The hemi-hippocampus shrinkage volume (%) was estimated to be (mean ± SD): 4.75 ± 1.22 (group 1); 5.56 ± 1.52 (group 2); 4.16 ± 1.21 (group 3); 5.05 ± 1.17 (group 4), and 5.75 ± 1.12 (group 5). No correction for global shrinkage was performed since inter-group differences were not statistically significant (p= 0.13).

Numerical density of CA1 neurons: NV (CA1)

The optical disector was used to estimate the numerical density of CA1 neurons in a given hemi-hippocampus. The formula for NV estimation is: where ΣQ− is the total number of particles counted by disectors, a is the counting frame area, p is the number of reference points per counting frame and ΣP is the total number of reference points in each counting frame, which hit the reference volume, CA1 layer in this case, t‾q− is the Q− -weighted mean section thickness measured and BA is the mean block advance in the vibratome. The mean number of disectors applied and particles counted (Q−) per group was (24; 244) (Group 1), (22; 241) (Group 2), (23; 342), (Group 3), (21; 274) (Group 4), and (22; 282) (Group 5), respectively.

Total Number of CA1 neurons: N (CA1)

The total number of CA1 neurons was estimated by multiplying the numerical density of CA1 neurons by the volume of CA1 layer. Therefore: N(CA1) := Nv(CA1) ·V(CA1) The bilateral number was obtained by simply multiplying N(CA1) · 2 since the left or right hemi-hippocampus was SUR sampled [17].

The error variance of total neuron number (CE(N)) was estimated as shown in [24] and [23]. The error variance was 0.03 for group 1; 0.03 for group 2; 0.03 for group 3; 0.03 for group 4, and 0.02 for group 5.

Mean Neuronal Volume: v‾N (CA1)

The mean perikaryal volume of CA1 neurons was estimate using a six-line vertical rotator [25]. On average, 200 neurons were sampled for the volume estimation, i.e. the same neurons which were sampled for number estimation.

Western blots

In brief, either the entire brain (n=7/group) or the hippocampus (n=4/group) from 14 day-old pups was carefully dissected and immediately dig-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Thawed specimens were pulverized with an electric homogenizer (ultra-Turrax homogenizer, Sigma, Saint Louis, MO), containing lysis buffer and then transferred to test tubes with protease inhibitor cocktail and centrifuged at 14 000 rpm. Supernatants were assayed using the bicinchoninic acid method, BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL) to standardize 50 μg of protein product. Samples were loaded into 15% denaturating polyacryamide min gels (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA), and gels were transferred overnight and then blotted onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were incubated with either rabbit synaptophisin or myelin basic protein (MBP) antibodies (at dilution of 1:500) for 1 hour and then rinsed 3 times in rinsing buffer then incubated in a secondary antibody and rinsed as described above. Each membrane was washed and exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY). Stripped blots were later incubated with actin antibodies as an internal control.

Biochemical analyses

Analyses of brain and serum zinc levels were conducted using atomic absorption spectroscopy (SpectrAA 55 AAS, Varian, CA, USA). A standard calibration curve was obtained using a standard zinc solution (0.2 mg Zn/L, J.T. Baker). The whole brain from 7 and 14 day-old pups was removed quickly after decapitation and rinsed with deionized water and stored frozen until analyzed. After thawing the whole brain was weighed and mineralized using a heated HNO3 (~110°C) solution and thereafter analyzed by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Dissected hippocampi were obtained from another set of 14 day-old experimental pups, and stored until analyzed. Analyses of amino acids (aspartate, glutamate, taurine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid, GABA) were carried out from dissected hippocampus using a high-performance liquid chromatography apparatus (HPLC, Shimadzu, Japan), and a fluorimetric detection method. Briefly, frozen tissue specimens were homogenized in 0.1M perchloric acid, and sonicated for 30 s at 25°C. After sonication, samples were centrifuged at 15,000 rpm, for 15min at 4°C. Supernatants were removed and filtered through a membrane (Millipore, 0.22 μm), and the amino acids were derivatized with mercaptoethanol and O-phthaldialdehyde. O-phthaldialdehyde derivatives were then separated on a C18 column (150mm × 4.6mm; from Shimadzu, Japan) and after derivatization, amino acids were separated, using a mobile phase, consisting of sodium phosphate buffer (50mM, pH 5.5) and 20% methanol. The area of each peak was determined with a Shimadzu software, and compared with the peak area of the corresponding external standard. Amino acid concentrations were expressed as μmol/mg of wet tissue.

Statistical analyses

Normal distribution was assured using Kolmogorov-Smirnov’s test and equity of variances (homoscedasticity) was checked by means of Levene’s test. Nutrition state-related effects amongst groups were assembled using one-way ANOVA through a statistical package, i.e. Minitab 15® (2007) and Graph Pad Prism 4.01 (2004). In case of p<0.05, Bonferroni’s test was applied to draw multiple comparisons amongst groups. In some behavioral tests, independent Student’s t test was used when appropriate.

RESULTS

Growth and behavioral tests in Swiss-mice

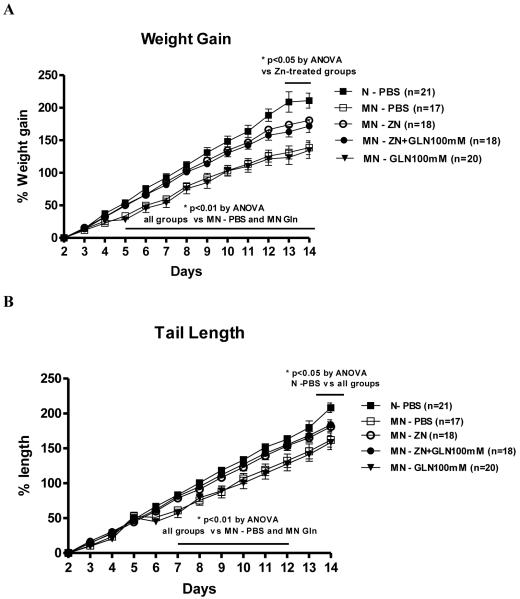

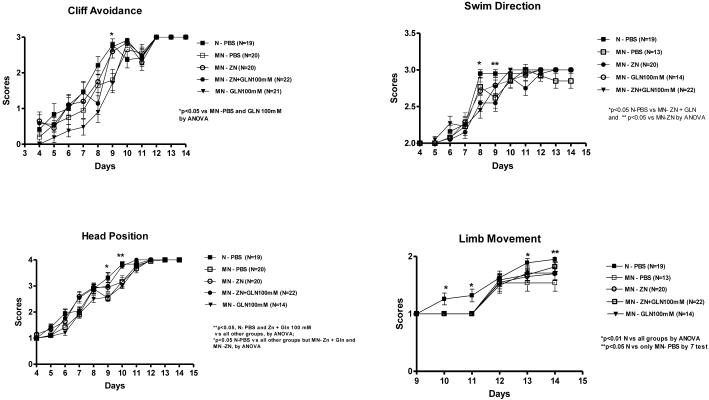

We have found a significant benefit of zinc treatment with or without glutamine on growth during the first two weeks of life (Fig.2). This zinc supplementation improved growth in the undernourished mice as early as the 5th day in weight gain and by the 7th day in tail length. Zinc treatment delayed the decrement in tail length as opposed to the other groups up to day 12 (Fig. 2B). Glutamine treatment alone was not sufficient to improve growth as compared to the untreated control. Zinc plus glutamine and zinc alone-treated groups had better cliff avoidance scores at day 9 than the untreated undernourished controls, reaching similar performance to the nourished mice (Fig 3A). The glutamine-treated undernourished mice did not show reductions in swim direction scores at day 9, as opposed to the untreated undernourished and zinc-treated groups (Fig.3B). In addition, both undernourished zinc-treated groups had similar scores as the nourished controls regarding head position during pool swimming at day 10 (p<0.05) and delayed the decrement of this reflex for 1 day (day 9) as compared with the untreated undernourished group (Fig. 3C). All treatments improve limb movement during swim at day 14, reaching similar score as the nourished control (Fig. 3D), although were not different as the undernourished control.

Figure 2.

Relative weight (A) and tail length (B) gain from the experimental mice during the malnutrition schedule. Statistical analyses were done from raw data using one-way analysis of variance corrected by Bonferroni’s test. The significance level was set at P<0.05. The results are shown as mean ± SEM. MN= malnourished mice; N= nourished mice.

Figure 3.

Behavioral tests (cliff avoidance and swim reflexes: direction, head position, and limb movement) conducted in the first two weeks of life in the nourished (N) and malnourished (MN) groups. Results are stratified in scores, accordingly. The significant level was set at P < 0.05.

Stereology

There was no significant difference in the hippocampus volume, V (HIP), total number of CA1 neurons, N (CA1), nor in the numerical density of CA1 neurons, NV (CA1), between the experimental groups (p>0.05). The undernourished mice supplemented with glutamine showed significant increase in the volume of CA1 layer, V (CA1), as compared with all other groups (p=0.018). Furthermore, the mean perikaryal volume of CA1 neurons, v‾N (CA1), was found remarkably increased in the undernourished untreated group (1,150.20 μm3) (0.13) as compared with all other groups (p=0.001). All treatments were able to prevent the increase in the neuronal volume to the level of the nourished controls (Tab.1). Fig. 1 illustrates the mouse hippocampus in coronal section with topographic regions and the application of a vertical rotator on nourished and undernourished subjects. Malnutrition-related neuronal hypertrophy is depicted in figure 1A (right top panel).

Table 1.

The effects of mice post-natal diet supplementation on the volume of CA1 layer (mm3), mean neuronal volume (μm3), hippocampus volume (mm3), numerical density of CA1 neurons (mm−3) and total number of CA1 neurons

| Variable | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | Group 4 | Group 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hippocampus Volume | 18.70 (0.24) |

17.60 (0.25) |

23.03 (0.36) |

22.11 (0.25) |

28.46 (0.43) |

| Layer Volume | 0.59 (0.10) |

0.57 (0.19) |

0.87(a) (0.34) |

0.52 (0.04) |

0.68 (0.25) |

|

Mean Neuronal

CA1 Volume |

1.150.20(b) (0.13) |

519.52 (0.06) |

664.51 (0.40) |

758.92 (0.23) |

599.58 (0.33) |

|

Neumerical Density

of Neurons |

2.20 × 105 (0.22) |

2.15 × 105 (0.16) |

2.20 × 105 (0.38) |

2.60 × 105 (0.01) |

2.78 × 105 (0.17) |

|

Total Number of

Neurons |

2.60 × 105 (0.29) |

2.40 × 105 (0.22) |

3.80 × 105 (0.36) |

2.70 × 105 (0.04) |

3.80 × 105 (0.36) |

Group 1: undernourished mice; Group 2- undernourished mice supplemented with zinc acetate; Group 3- undernourished mice supplemented with glutamine (100 mM); Group 4- undernourished mice supplemented with zinc acetate and glutamine (100 mM); Group 5- nourished mice receiving PBS. Values are group means (CV) for n=4 (groups 1, 2, 3, 5), and n=3 (group 4). Nutrition state-related effects amongst groups were assembled using one-way ANOVA. In case of p<0.05, Tukey’s test was applied to draw multiple comparisons amongst groups.

Group 3 is different from all other groups (p=0.018)

Group 1 is different from all other groups (p=0.001)

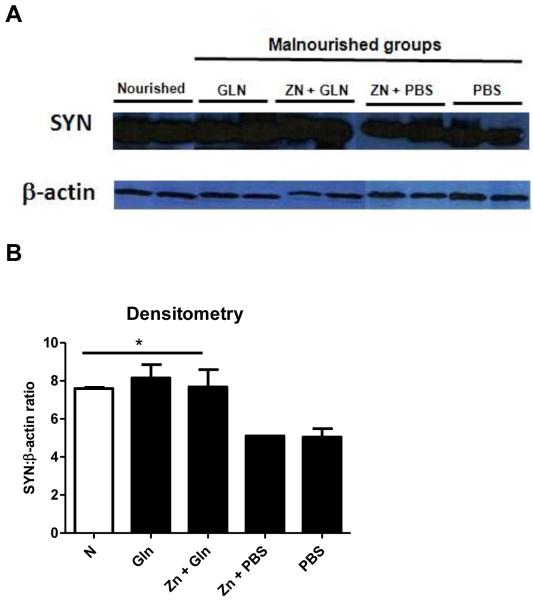

Western blots

Although clear expressions of myelin basic protein (MBP) were found in the whole brains and hippocampi of experimental mice, no difference were found between groups on day 14th. However, we could find higher expression of synaptophysin (SYN) in the dissected hippocampus of the nourished group compared with the untreated undernourished group. In addition, glutamine treatment with or without zinc increased hippocampal synaptophysin expression, reaching similar expressions as the nourished control group (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

A: Representative immunoblots of the hippocampus from the experimental mice for synaptophysin (SYN) on day 14th. B: Synaptophysin was normalized against β-actin and the densitometry data plotted. White bar represents the nourished group; black bars depict the malnourished groups. The significance level was set at P<0.05, by Student T test. The results are shown as mean ± SEM.

Biochemical analyses

In order to appreciate the importance of zinc in the results mentioned above, we measured zinc brain and serum levels at days 7 and 14th of birth, during the malnutrition schedule. We found no differences in zinc serum levels between groups, although a trend of improvement was found. Furthermore, we found a significant increase in brain zinc levels in the glutamine (100 mM) treated group at day 7 as compared to the untreated and zinc-treated malnourished mice (p<0.01). A difference was also found between the nourished group and the undernourished control (p=0.02) (Tab. 2). No difference was found between the groups at day 14, although a trend of increase brain zinc levels in the glutamine group was apparent (p=0.07).

Table 2.

Hippocampal neurotransmitter levels and serum zinc and whole brain levels

| Sample Groups |

Zinc | Glutamate | Aspartate | GABA | Taurine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum (μg/dL) |

Brain (μg of tissue/dL) |

Hippocampus (μmol/g of tissue) |

||||||

| 7th day | 14th day | 7th day | 14th day | 14th day | ||||

| Nourished | 228 ± 12.6 (n=7) |

141 ± 4.91 (n=16) |

28.22 ± 0.56** (n=7) |

17.69 ± 0.56 (n=8) |

319.7 ± 68.08 (n=6) |

4937 ± 1135* (n=3) |

520.2 ± 738.3 (n=5) |

2480 ± 525.3 (n=8) |

| PBS | 202.7 ± 7.6 (n=3) |

150.7 ± 9.77 (n=19) |

23.66 ± 1.93 (n=5) |

18.08 ± 0.9 (n=14) |

538.8 ± 407.3 (n=3) |

788.5 ± 173.3 (n=3) |

117.6 ± 99.8 (n=5) |

1699 ± 820 (n=5) |

| Gln | 207 ± 10.7 (n=6) |

151.3 ± 10.29 (n=19) |

34.84 ± 1.29# (n=6) |

22.43 ± 2.28 (n=12) |

888.1 ± 250.7 (n=6) |

230 ± 102.7** (n=6) |

1194 ± 347.2# (n=6) |

2291 ± 570.3 (n=6) |

| Zn | 223.6 ± 9.47 (n=7) |

167.4 ± 13.3 (n=14) |

30.46 ± 2.87 (n=7) |

21.13 ± 1.63 (n=9) |

481.7 ± 74.54 (n=5) |

1525 ± 821.8 (n=3) |

702.1 ± 188.9** (n=6) |

2672 ± 299.3 (n=7) |

| Zn + Gln | 192 ± 6.45 (n=6) |

180.2 ± 12.4 (n=11) |

25.44 ± 1.37 (n=7) |

20.86 ± 1.07 (n=8) |

492.5 ± 112.2 (n=6) |

1047 ± 562.6 (n=6) |

134 ± 44.2 (n=6) |

2274 ± 475.2 (n=6) |

Data are presented as Mean ± SEM.

p <0.05 vs all other groups by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison test.

p<0.05 vs malnourished PBS by unpaired Student T test

p<0.05 vs malnourished PBS and Zn plus Gln-treated groups by one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison test

No changes were seen with the amino acids taurine and glutamate between groups. Aspartic acid brain levels were significantly reduced by litter size clustering. This effect was not improved by any treatment. Same happens with glycine levels (data not shown). Glutamine and zinc treatments significantly increased GABA brain levels in undernourished mice as opposed to the PBS untreated group (p<0.05) (Tab. 2).

DISCUSSION

Malnutrition during suckling in experimental rodents has been consistently recognized to cause lasting effects on behavior, growth, innate immunity and endocrine functions, which may predispose to obesity and ultimately cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases [26-28].

In accordance with our findings of zinc benefit on growth, a recent metanalyses of preventive zinc supplementation among infants and children have shown a significant evidence of weight gain and linear growth improvements [29]. In support to our findings of lack of glutamine benefit on growth, most of the clinical data available have not shown growth advantages of glutamine parenteral nutrition to low-birth infants [30], although controversial findings exist. Recently, a double-blinded clinical trial has found a growth benefit of long-term (4 month-treatment) supplemented enteral nutrition on different nutritional parameters in very low birth-weight infants [31].

Our behavioral findings (delays in swim reflex) among undernourished mice in the first weeks of life are in agreement with classic studies of suckling mice reared in large litters [32], however our data differ from those of Tanaka et al [13]. Barros and colleagues using a low protein diet to the dams (with a formula similar to Brazilian regional diets accessible to children) also found delays of reflex ontogenesis in undernourished suckling pups [33].

Malnutrition can also disrupt the hippocampus, although a time-related vulnerability of the brain to malnutrition seems to occur; some alterations were observed only at birth (e.g., GFAP); others were observed on the 2nd and 15th post-natal days (e.g., ERK phosphorylation) [34].

Nutrients given by supplementation may or may not interact with each other in supporting brain development. For example, zinc supplementation given chronically to vitamin A-deficient mice improved nerve growth factor levels in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex and cerebellum extracts, however did not enhance mouse memory outcomes when vitamin A was deprived [35]. Zinc deficiency during lactation in rats was found to have lasting growth deficits after dietary rehabilitation and delay the first-week post-natal reflexes, including auditory startle, air righting and rope descent as compared to nourished controls [36]. In our study, we have found a significant brain zinc deficiency due to litter clustering in 7 day-old mice but not later with 14 days old. The reason might be that suckling mice have a faster growth pace at this age and are more dependent on breast milk-derived zinc to thrive. Additionally, intestinal absorption of zinc may come exclusively from the breast-milk borne zinc-binding-protein transport, since the intestinal zinc-binding protein system is absence during the neonatal time [37]. We speculate that breast-milk restriction by litter clustering may have decreased zinc-binding proteins provided by the breast-milk and impaired zinc absorption to the pups. Zinc may especially be driven to the developing brain and this effect may compensate the malnutrition challenge to the nervous tissue. This fact could explain the behavioral benefit of the zinc-treated groups.

Despite the lack of significant negative results regarding the myelin basic protein expression (MBP, an oligodendrocyte-derived protein) in the brains of undernourished mice compared to the nourished controls, we cannot rule out a regional effect, since our western blot data come from the whole brain and the hippocampus from the suckling pups. Montanha-Rojas et al found that rats submitted to malnutrition during the first half of the lactation period exhibited lower MBP expression in the temporal lobes, which were partially sustained in adulthood [38]. Gressens and colleagues using a low protein diet (5% of casein) to early pregnant rats observed a moderate increased expression of synaptophysin in the basal ganglia of their undernourished offspring at birth and at post-natal day 7, however were not able to find changes in the neocortex, hippocampus, brain stem and cerebellum in different time tables throughout the first and second week of post-natal development [39]. Our study likewise did not find changes in synaptophysin (a marker for synaptic density) in brain tissues of undernourished mice at day 14. However, we could find a reduction in the hippocampal synaptophysin expression in suckling mice afflicted by malnutrition as compared with the nourished control at the same time point. Furthermore, we were able to find increased synaptophysin expression among the glutamine-treated group as opposed to the undernourished PBS control. This finding deserves further clarification, but it may indicate an advantageous increase in the synaptic pool within the hippocampus rather than an abnormal burst of synaptogenesis, since it was found in similar levels in the nourish group. Interestingly, brain zinc levels were increased in the undernourished glutamine-treated group by yet an unknown mechanism. Interestingly, zinc is abundantly found in the hippocampal synaptic contacts, as previously stressed.

Our current data in Swiss mice provide new evidence of zinc supplementation early in life to prevent behavioral deficits due to malnutrition by restricting lactation. Zinc deficiency has been implicated to reduce the overall brain size with profound deficits in the cerebellum, including loss of cortical granular cells, immature Purkinje and basket cells [40,41]. In addition, one of the highest levels of zinc in the brain is found in the hippocampus in synaptic vesicles, boutons, and mossy fibers [42]. Improvements in motor-reflex development seen with zinc supplementation might be explained by the better plasticity in areas such as the hippocampus and cerebellum.

Breast-milk zinc levels seem to be affected by this malnutrition model, since oral supplementation to the dams improved most of the behavioral tests. Most of our findings suggest the more important role of zinc in improving early motor reflex acquisition than glutamine during suckling time. In addition, we showed for the first time the benefit of both treatments in preventing morphological changes in the neuronal volume, associated with malnutrition.

The main morphoquantitative findings in this study were: 1- CA1 neuron hypertrophy in undernourished mice, 2- increase in CA1 neuron layer volume in undernourished glutamine-supplemented mice and 3- no malnutrition-induced changes in the total number of CA1 neurons.

CA1 neurons in undernourished mice are 92% bigger than nourished subjects and also larger than all supplemented mice. The size of those hypertrophied cells (1,150 μm3) is in line with that of a CA1 neuron of rat hippocampus, i.e. 1,661 μm3 [18]. That seems a compensatory mechanism to circumvent the deficiency in nutrients. Along similar lines, neuron hypertrophy may occur as a result of ageing-related loss of human substantia nigra neurons indicating cell degeneration or necrosis, and characterized by perikaryon and dendrite swelling [43].

Another surprising outcome of this paper was a 28% increase in the volume of CA1 layer in undernourished-glutamine supplemented mice when compared to untreated nourished and undernourished subjects, which might be partially explained by the observed trend toward increased cell number in this layer. To our knowledge, there is a lack of studies exploring the role of glutamine supplementation in the brain plasticity during early development. Phosphate-activated glutaminase (PAG) is present at high levels in the cerebellar mossy fiber terminals and glutamine availability may enable the synthesis of glutamate, an important excitatory neurotransmitter [44]. In addition, increased PAG immunoreactivity was recorded in subpopulations of surviving neurons in the hippocampal formation, particularly in CA1 and CA3 and in the polymorphic layer of the dentate gyrus in patients with temporal lope epilepsy [45].

In contrast to previous studies using either pre-natal [46,47] or post-natal protein-deprivation models in rats [16], we have shown no reduction in the volume of CA1 layer in undernourished mice. Pre-natal protein deprivation caused a 22% [46] and 17% [47] decrease in hippocampus CA1 layer volume whereas post-natal protein deficit led to a 33% irreversible diminution in the same neuron layer.

A possible explanation for the non-reduction in CA1 layer volume may be the nature and length of our post-natal malnutrition model, which seems to be less severe than a six, twelve or eighteen-month post-natal protein deprivation scheme [16,48].

It is widely known that protein deficit yields an irreversible CA1 neuron loss in rats during either pre-natal, e.g. 20% [46], 12% [47] or post-natal development even followed by refeeding, e.g. 120% [16] and 30% [49]. Paradoxically, this study depicted no changes in the total number of CA1 neurons, and it may be related to the malnutrition model used, which was performed using selective and time-effective nutritional interventions [50]. Similarly, a chronic food-restriction program (not protein deprivation) failed to show decrements in CA1 neuron number in rats [49].

An intriguing and remaining question is how to mechanistically explain the increase in CA1 region volume (undernourished and glutamine-supplemented mice) without changes in individual cell sizes (in the same animals). By the same token, the number of CA1 neurons in undernourished and glutamine-supplemented mice is exactly the same as that from nourished mice. Albeit CA1 neuron number did not change, we cannot exclude the possibility that neuron remodeling might have occurred in these animals. Thus, further studies may focus on possible on-going neuroplasticity processes (neurons and synapses) using selective and less severe malnutrition programs as employed in this paper. In fact, thiamine re-administering reversed impaired hippocampal neurogenesis (CA1 and CA3 neurons) induced by thiamine deficiency [51].

Interesting data come from GABA levels changed by glutamine intervention in our litter size studies with Swiss mice. GABA, an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the adult brain, has been associated as an excitatory neurotransmitter in the neonatal brain, having a role with synaptic circuitry plasticity in the hippocampus [52] and may be protective in models of hippocampal injury in young mice [53]. Recently, Tamano et al found GABA declines in the hippocampus following zinc deprivation, and suggest that state of undernutrition could lead to glucose insufficiency for GABA synthesis [54]. Unexpectedly, glutamine intervention led to an early increase in zinc brain levels and may facilitate glucose bioavailability to the hippocampus. However, these findings were not accompanied by a significant behavior advantage by single glutamine treatment, suggesting that the components of our testing battery may not be revealing a consistent hippocampal-born behavior. We are now planning Morris maze assessments in older cohort mice to evaluate this hypothesis.

Although, we acknowledge that sociability issues due to different litter sizes may have a role in this model, we emphasize that crowded households and large numbers of children are often seen in shantytown communities in association with poor socioeconomic status and constitute as a risk factor for the enteric infection and malnutrition vicious cycle [55].

CONCLUSION

We concluded that glutamine or zinc protects against malnutrition-induced increased in neuronal cell volume, increased that like predispose to cell death. Glutamine also increased CA1 layer volume with a trend toward increased cell number, raised hippocampal synaptophysin expression and transiently increased zinc brain levels. In addition, zinc improved several behavioral parameters as well as growth. These overall findings suggest the advantage of zinc and glutamine supplementation in undernourished children. More studies are needed to examine the mechanisms (e.g. Apoptosis and neurogenesis in the hippocampus) related to these alterations, as well as their relevance to cognitive development in children, studies which are now being planned by our group.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank José Ivan Rodrigues de Sousa for laboratory technical assistance. This study was supported by NIH Research grants 5D43TW006578-06 funded by the Fogarty International Center and 5R01HD053131 funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and the NIH Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) and by the Brazilian funding agencies FUNCAP and CNPq.

Abbreviations used

- SYN

synaptophysin

- MPB

myelin basic protein

- PAG

phosphate-activated glutaminase

- DG

dentate gyrus

- SUR

systematic-uniform random

- VUR

vertical uniform-random

- CA

cornu ammonis

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- GABA

gamma-amino butyric acid

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- HAZ

height-for-age z score

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

FVLD, AABLD, and AAMCR contributed with the stereological studies.

SBCC, BPC, ICC, BBO, and CMCC contributed with the behavioral studies

AAML, RLG, and RBO contributed with the study design, study analysis and manuscript preparation

GAM and CECM contributed with neurochemical and zinc measurements.

References

- [1].Rice D, Barone S., Jr. Critical periods of vulnerability for the developing nervous system: evidence from humans and animal models. Environ Health Perspect. 2000;108(Suppl 3):511–533. doi: 10.1289/ehp.00108s3511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Frankova S, Barnes RH. Effect of malnutrition in early life on avoidance conditioning and behavior of adult rats. J Nutr. 1968;96:485–493. doi: 10.1093/jn/96.4.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Georgieff MK. Nutrition and the developing brain: nutrient priorities and measurement. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:614S–620S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.614S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Pinero D, Jones B, Beard J. Variations in dietary iron alter behavior in developing rats. J Nutr. 2001;131:311–318. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.2.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Moore SR, Lima AA, Conaway MR, Schorling JB, Soares AM, Guerrant RL. Early childhood diarrhoea and helminthiases associate with long-term linear growth faltering. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:1457–1464. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.6.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Patrick PD, Oria RB, Madhavan V, Pinkerton RC, Lorntz B, Lima AA, et al. Limitations in verbal fluency following heavy burdens of early childhood diarrhea in Brazilian shantytown children. Child Neuropsychol. 2005;11:233–244. doi: 10.1080/092970490911252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Lorntz B, Soares AM, Moore SR, Pinkerton R, Gansneder B, Bovbjerg VE, et al. Early childhood diarrhea predicts impaired school performance. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:513–520. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000219524.64448.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Drozdowski L, Thomson AB. Intestinal mucosal adaptation. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:4614–4627. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i29.4614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Penny ME, Marin RM, Duran A, Peerson JM, Lanata CF, Lonnerdal B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effect of daily supplementation with zinc or multiple micronutrients on the morbidity, growth, and micronutrient status of young Peruvian children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:457–465. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Miki T, Satriotomo I, Li HP, Matsumoto Y, Gu H, Yokoyama T, et al. Application of the physical disector to the central nervous system: estimation of the total number of neurons in subdivisions of the rat hippocampus. Anat Sci Int. 2005;80:153–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-073x.2005.00121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lastra MD, Pastelin R, Herrera MA, Orihuela VD, Aguilar AE. Increment of immune responses in mice perinatal stages after zinc supplementation. Arch Med Res. 1997;28:67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rotstein M, Bassan H, Kariv N, Speiser Z, Harel S, Gozes I. NAP enhances neurodevelopment of newborn apolipoprotein E-deficient mice subjected to hypoxia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:332–339. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.106898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tanaka T. Effects of litter size on behavioral development in mice. Reprod Toxicol. 1998;12:613–617. doi: 10.1016/s0890-6238(98)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pantaleoni GC, Fanini D, Sponta AM, Palumbo G, Giorgi R, Adams PM. Effects of maternal exposure to polychlorobiphenyls (PCBs) on F1 generation behavior in the rat. Fundam Appl Toxicol. 1988;11:440–449. doi: 10.1016/0272-0590(88)90108-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Palanza P, Parmigiani S, vom Saal FS. Effects of prenatal exposure to low doses of diethylstilbestrol, o,p’DDT, and methoxychlor on postnatal growth and neurobehavioral development in male and female mice. Horm Behav. 2001;40:252–265. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.2001.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Andrade JP, Madeira MD, Paula-Barbosa MM. Effects of long-term malnutrition and rehabilitation on the hippocampal formation of the adult rat. A morphometric study. J Anat. 1995;187(Pt 2):379–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chen F, Madsen TM, Wegener G, Nyengaard JR. Changes in rat hippocampal CA1 synapses following imipramine treatment. Hippocampus. 2008;18:631–639. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hosseini-Sharifabad M, Nyengaard JR. Design-based estimation of neuronal number and individual neuronal volume in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci Methods. 2007;162:206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2007.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Baddeley AJ, Gundersen HJ, Cruz-Orive LM. Estimation of surface area from vertical sections. J Microsc. 1986;142:259–276. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1986.tb04282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Gundersen HJ. Estimators of the number of objects per area unbiased by edge effects. Microsc Acta. 1978;81:107–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 2004. 2nd. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Klausberger T, Somogyi P. Neuronal diversity and temporal dynamics: the unity of hippocampal circuit operations. Science. 2008;321:53–57. doi: 10.1126/science.1149381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nyengaard JR. Stereologic methods and their application in kidney research. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1100–1123. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1051100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB, Kieu K, Nielsen J. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology--reconsidered. J Microsc. 1999;193:199–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1999.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tandrup T, Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB. The optical rotator. J Microsc. 1997;186:108–120. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.1997.2070765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Prestes-Carneiro LE, Laraya RD, Silva PR, Moliterno RA, Felipe I, Mathias PC. Long-term effect of early protein malnutrition on growth curve, hematological parameters and macrophage function of rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2006;52:414–420. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.52.414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Castellano C, Oliverio A. Early malnutrition and postnatal changes in brain and behavior in the mouse. Brain Res. 1976;101:317–325. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(76)90272-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mozes S, Sefcikova Z, Lenhardt L. Functional changes of the small intestine in over- and undernourished suckling rats support the development of obesity risk on a high-energy diet in later life. Physiol Res. 2007;56:183–192. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.930952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Brown KH, Peerson JM, Baker SK, Hess SY. Preventive zinc supplementation among infants, preschoolers, and older prepubertal children. Food Nutr Bull. 2009;30:S12–S40. doi: 10.1177/15648265090301S103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].van den Berg A, van Elburg RM, Vermeij L, van ZA, van den Brink GR, Twisk JW, et al. Cytokine responses in very low birth weight infants receiving glutamine-enriched enteral nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:94–101. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181805116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Korkmaz A, Yurdakok M, Yigit S, Tekinalp G. Long-term enteral glutamine supplementation in very low birth weight infants: effects on growth parameters. Turk J Pediatr. 2007;49:37–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Nagy ZM, Porada KJ, Anderson JA. Undernutrition by rearing in large litters delays the development of reflexive, locomotor, and memory processes in mice. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1977;91:682–696. doi: 10.1037/h0077340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Barros KM, Manhaes-De-Castro R, Lopes-De-Souza S, Matos RJ, Deiro TC, Cabral-Filho JE, et al. A regional model (Northeastern Brazil) of induced mal-nutrition delays ontogeny of reflexes and locomotor activity in rats. Nutr Neurosci. 2006;9:99–104. doi: 10.1080/10284150600772148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Feoli AM, Leite MC, Tramontina AC, Tramontina F, Posser T, Rodrigues L, et al. Developmental changes in content of glial marker proteins in rats exposed to protein malnutrition. Brain Res. 2008;1187:33–41. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Kheirvari S, Uezu K, Sakai T, Nakamori M, Alizadeh M, Sarukura N, et al. Increased nerve growth factor by zinc supplementation with concurrent vitamin A deficiency does not improve memory performance in mice. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2006;52:421–427. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.52.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Eberhardt MJ, Halas ES. Developmental delays in offspring of rats undernourished or zinc deprived during lactation. Physiol Behav. 1987;41:309–314. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(87)90393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Duncan JR, Hurley LS. Intestinal absorption of zinc: a role for a zinc-binding ligand in milk. Am J Physiol. 1978;235:E556–E559. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.5.E556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Montanha-Rojas EA, Ferreira AA, Tenorio F, Barradas PC. Myelin basic protein accumulation is impaired in a model of protein deficiency during development. Nutr Neurosci. 2005;8:49–56. doi: 10.1080/10284150500049886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gressens P, Muaku SM, Besse L, Nsegbe E, Gallego J, Delpech B, et al. Maternal protein restriction early in rat pregnancy alters brain development in the progeny. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1997;103:21–35. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(97)00109-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Dvergsten CL, Fosmire GJ, Ollerich DA, Sandstead HH. Alterations in the postnatal development of the cerebellar cortex due to zinc deficiency. I. Impaired acquisition of granule cells. Brain Res. 1983;271:217–226. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(83)90284-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dvergsten CL, Johnson LA, Sandstead HH. Alterations in the postnatal development of the cerebellar cortex due to zinc deficiency. III. Impaired dendritic differentiation of basket and stellate cells. Brain Res. 1984;318:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(84)90058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Pfeiffer CC, Braverman ER. Zinc, the brain and behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 1982;17:513–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Cabello CR, Thune JJ, Pakkenberg H, Pakkenberg B. Ageing of substantia nigra in humans: cell loss may be compensated by hypertrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2002;28:283–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2002.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Holten AT, Gundersen V. Glutamine as a precursor for transmitter glutamate, aspartate and GABA in the cerebellum: a role for phosphate-activated glutaminase. J Neurochem. 2008;104:1032–1042. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Eid T, Hammer J, Runden-Pran E, Roberg B, Thomas MJ, Osen K, et al. Increased expression of phosphate-activated glutaminase in hippocampal neurons in human mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:137–152. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lister JP, Blatt GJ, DeBassio WA, Kemper TL, Tonkiss J, Galler JR, et al. Effect of prenatal protein malnutrition on numbers of neurons in the principal cell layers of the adult rat hippocampal formation. Hippocampus. 2005;15:393–403. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Lister JP, Tonkiss J, Blatt GJ, Kemper TL, DeBassio WA, Galler JR, et al. Asymmetry of neuron numbers in the hippocampal formation of prenatally malnourished and normally nourished rats: a stereological investigation. Hippocampus. 2006;16:946–958. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Andrade JP, Paula-Barbosa MM. Protein malnutrition alters the cholinergic and GABAergic systems of the hippocampal formation of the adult rat: an immunocytochemical study. Neurosci Lett. 1996;211:211–215. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12734-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Lukoyanov NV, Andrade JP. Behavioral effects of protein deprivation and rehabilitation in adult rats: relevance to morphological alterations in the hippocampal formation. Behav Brain Res. 2000;112:85–97. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Ziegler TR, Evans ME, Fernandez-Estivariz C, Jones DP. Trophic and cytoprotective nutrition for intestinal adaptation, mucosal repair, and barrier function. Annu Rev Nutr. 2003;23:229–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Zhao N, Zhong C, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Gong N, Zhou G, et al. Impaired hippocampal neurogenesis is involved in cognitive dysfunction induced by thiamine deficiency at early pre-pathological lesion stage. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;29:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Gaiarsa JL. Plasticity of GABAergic synapses in the neonatal rat hippocampus. J Cell Mol Med. 2004;8:31–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2004.tb00257.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Azimi-Zonooz A, Shuttleworth CW, Connor JA. GABAergic protection of hippocampal pyramidal neurons against glutamate insult: deficit in young animals compared to adults. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:299–308. doi: 10.1152/jn.01082.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Tamano H, Kan F, Kawamura M, Oku N, Takeda A. Behavior in the forced swim test and neurochemical changes in the hippocampus in young rats after 2-week zinc deprivation. Neurochem Int. 2009;55:536–41. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Guerrant RL, Kirchhoff LV, Shields DS, Nations MK, Leslie J, de Sousa MA, et al. Prospective study of diarrheal illnesses in northeastern Brazil: patterns of disease, nutritional impact, etiologies, and risk factors. J Infect Dis. 1983;148:986–997. doi: 10.1093/infdis/148.6.986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]