Abstract

Aims

To investigate the prevalence and patterns of transitions between cigarette and snus use.

Design

Cross-sectional study within the population-based Swedish Twin Registry.

Setting and participants

A total of 31 213 male and female twins 42–64 years old.

Measurements

Age-adjusted prevalence odds ratios (POR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) described the association between gender and tobacco use, while Kaplan–Meier survival methods produced cumulative incidence curves of age at onset of tobacco use. Life-time tobacco use histories were constructed using ages at onset of tobacco use and current tobacco use status.

Findings

Although more males reported ever smoking (64.4%) than females (61.7%), more males were former smokers (POR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.27–1.39). Males were far more likely to use snus than females (POR: 18.0, 95% CI: 16.17–20.04). Age at onset of cigarette smoking occurred almost entirely before age 25, while the age at onset of snus use among males occurred over a longer time period. Most men began using cigarettes first, nearly one-third of whom switched to using cigarettes and snus in combination. While 30.6% of these combined users quit tobacco completely, only 7.4% quit snus and currently use cigarettes, while 47.7% quit cigarettes and currently use snus.

Conclusions

Current cigarette smoking is more prevalent among Swedish women than men, while snus use is more prevalent among men. Among men who reported using both cigarettes and snus during their life-time, it was more common to quit cigarettes and currently use snus than to quit snus and currently use cigarettes. Once snus use was initiated, more men continued using snus rather than quit tobacco completely.

Keywords: Cigarettes, prevalence, snus, Sweden, tobacco

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use is the largest preventable cause of death in the world [1]. To reduce the impact of tobacco use on world-wide health, tobacco users have been urged for decades to quit. Sweden was the only European country to meet the World Health Organization’s goal of having less than 20% daily cigarette smoking prevalence among adults by 2000 [2]. While cigarette use in Sweden has declined dramatically over time [3,4], overall tobacco use has remained fairly stable [5] as a result of the increasing popularity of snus (a form of oral snuff) that Swedes may be using as an alternative nicotine source. In order to develop more effective intervention strategies to achieve maximum reductions in death and disease from tobacco use, improved understanding of the prevalence and patterns of cigarette and snus use are required.

Swedish snus is a smokeless tobacco product manufactured in a way that is reported to deliver lower concentrations of harmful chemicals than other tobacco products while retaining its high nicotine content [6–8]. While snus is addictive [9], it has not been associated consistently with cancers of the head and neck [10,11], stomach [12,13], esophagus [13] or skin [8]. A recent study conducted in Norway, however, reported an increased risk of pancreatic cancer among men who had ever used snus [14]. The evidence is conflicting as to whether snus is associated with increased cardiovascular disease risk [15–19].

Swedes appear to be taking up snus as an alternative to smoking [20]. Although research documents the decline of cigarette use and rise of snus use in Sweden over time [3,4,21,22], most studies are ecological and lack individual-level information that permits more detailed evaluation of transitions between the types of tobacco use which underlie these trends. Only three studies, conducted among specific subpopulations, have evaluated transitions between different forms of tobacco in Sweden [5,23,24]. Rodu et al. [5,23] published findings from two studies among residents of two counties in Northern Sweden, while Ramström et al. [24] examined transitions between cigarette and snus use among males aged 18–34 years.

In order to understand the changes in tobacco use practices in Sweden, a more detailed picture of an individual’s tobacco use history over time is needed. The goals of this report are: (1) to describe the prevalence of cigarette smoking and snus use among 31 213 men and women 42–64 years of age in the population-based Swedish Twin Registry, (2) to examine age-at-onset curves for each type of tobacco use by gender and (3) to evaluate transitions between forms of tobacco use (cigarette and snus).

METHODS

Swedish Twin Registry (STR)

The STR (http://www.mep.ki.se/twinreg/index_en.html) is the largest population-based registry of twin births in the world [25,26]. The STR contains data on current vital status, marital status, address and place of birth for > 99% of all ~160 000 Swedish twins born between 1886 and 2000. The data collection procedures were reviewed and approved by the Swedish Data Inspection Board and the Regional Ethics Committee of the Karolinska Institutet. All subjects provided verbal informed consent during the telephone interview, which was later confirmed by postcard.

Assessment of smoking and snus use

Over a 4-year period ending in December 2002, all living, contactable, interviewable and consenting twins in the STR born 1 January 1935–31 December 1958 were screened for a range of disorders that included tobacco use (n = 31 425). Detailed tobacco use information from a telephone interview was available on 31 213 participants aged 42–64 years. Less than 1% of the interviewed twins did not contribute tobacco use information (n = 212, 0.7%) and were more likely to be male and older (mean and standard deviation of the age of non-participants 55.9 ± 5.7 versus 53.7 ± 5.8, P < 0.001). Participants answered questions regarding the types of tobacco they used during their life-time (cigarettes and/ or snus), age of initiation for each type of tobacco use and whether they used either type of tobacco at the time of interview. In addition, they provided information on the type of tobacco user they considered themselves to be; for the cigarette category the participant could describe him- or herself either as a regular smoker, someone who smokes now and then, someone who smokes at parties or someone who never even tried cigarettes. A snus user could describe him- or herself as a regular snus user, someone who uses snus now and then or someone who never tried snus. We used the ages at initiation of tobacco use and tobacco use status at the time of interview to reconstruct their tobacco use histories and determine transitions between tobacco use over time.

Statistical analyses

Analyses were conducted with SAS 9.1 [27] and were stratified by gender. Prevalence odds ratios (PORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were obtained from age-adjusted logistic regression models as measures of association between gender and tobacco use. As the sampling units for this survey were twin pairs, we used generalized estimating equations to adjust for the clustering or non-independence of members of a twin pair [28]. Specifically, we utilized the sandwich estimator of the variance and specified the exchangeable correlation structure. To test the robustness of our findings, we selected randomly one member from each twin pair and repeated the aforementioned analyses on this subset of singletons. As expected, the results were nearly identical, with the exception of wider confidence intervals due to diminished sample size. We used the Kaplan–Meier estimator method to examine age at onset curves of cigarette smoking in males and females, and of snus use among males [29,30]. For the age-at-onset curves, time was defined as chronological age. Ages at onset of tobacco use were used to define the event (i.e. ever cigarette use and ever snus use), while age at interview was used as the censoring variable for those who never used cigarettes or snus.

RESULTS

Prevalence of cigarette smoking and snus use

Tobacco use information was obtained on 31 213 participants, slightly more than half of whom were female (52.5%). The mean ages at interview (± standard deviation) for each gender were similar: 53.7 (± 5.8) years for males and 53.8 (± 5.8) years for females. Table 1 presents the prevalence of cigarette use and snus use separately for the total population and by gender. Of the total study population, 63% of participants reported ever smoking cigarettes in their life-time. At the time of interview 39.3% were former smokers, while 23.7% were current smokers. Approximately half the participants described themselves as ‘regular’ ever smokers, while 11.9% reported smoking ‘now and then’ or ‘at parties’.

Table 1.

Distributions of cigarette smoking and snus use in the Swedish Twin Registry.

| Total n = 31213 |

Males n = 14814 |

Females n = 16399 |

Age-adjusted POR (95% CI)1 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ever smoking and type of smoker | ||||

| Ever | 63.0% | 64.4% | 61.7% | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) |

| Regular | 51.1% | 53.4% | 49.0% | 1.18 (1.13–1.24) |

| Now and then | 4.8% | 4.6% | 5.0% | 0.96 (0.86–1.08) |

| At parties | 7.1% | 6.4% | 7.7% | 0.84 (0.77–0.93) |

| Never | 37.0% | 35.6% | 38.3% | 1.00 (reference) |

| Smoking status at time of interview | ||||

| Current | 23.7% | 21.6% | 25.6% | 0.80 (0.76–0.85) |

| Former | 39.3% | 42.8% | 36.1% | 1.33 (1.27–1.39) |

| Never | 37.0% | 35.6% | 38.3% | 1.00 (reference) |

| Ever snus use and type of snus user | ||||

| Ever | 15.8% | 30.4% | 2.5% | 18.00 (16.17–18.22) |

| Regular | 13.8% | 27.2% | 1.8% | 22.38 (19.75–25.35) |

| Now and then | 2.0% | 3.2% | 0.7% | 6.74 (5.50–8.27) |

| Never | 84.2% | 69.6% | 97.5% | 1.00 (reference) |

| Snus use status at time of interview | ||||

| Current | 9.9% | 19.1% | 1.5% | 15.90 (13.88–18.22) |

| Former | 5.9% | 11.3% | 1.0% | 12.57 (10.68–14.80) |

| Never | 84.2% | 69.6% | 97.5% | 1.00 (reference) |

Prevalence odds ratios (POR) describe the association between each smoking and snus variable comparing males to females, adjusted for age and after statistical adjustment for the non-independence of twin pairs.

The life-time prevalence of cigarette smoking differed significantly by gender. More males reported ever smoking than females. However, more males than females had quit smoking at the time of interview (42.8% versus 36.1%). The age-adjusted POR for former versus never smoking comparing males to females was 1.33 (95% CI: 1.27–1.39), while the age-adjusted POR for current versus never smoking comparing males to females was 0.80 (95% CI: 0.76–0.85). Regular smoking was more common among males, while similar proportions of males and females smoked ‘now and then’ and at parties.

The life-time prevalence of snus use in the total study population was 15.8%. At the time of interview, 5.9% of participants were former snus users, while 9.9% were current snus users. The prevalence of snus use differed dramatically by gender, with far more males than females reporting ever using snus (30.4% versus 2.5%), and far more males than females were current snus users (19.1% versus 1.5%). The age-adjusted POR for ever snus use comparing males to females was 18.0 (16.2–20.0). The age-adjusted POR for current snus use comparing males to females was 15.9 (95% CI: 13.9–18.2). Males were also more likely to report ‘regular’ snus use than females (POR: 22.4 (95% CI: 19.8–254). Given the low proportion of women who used snus in this population, we restricted further analyses involving snus use to males.

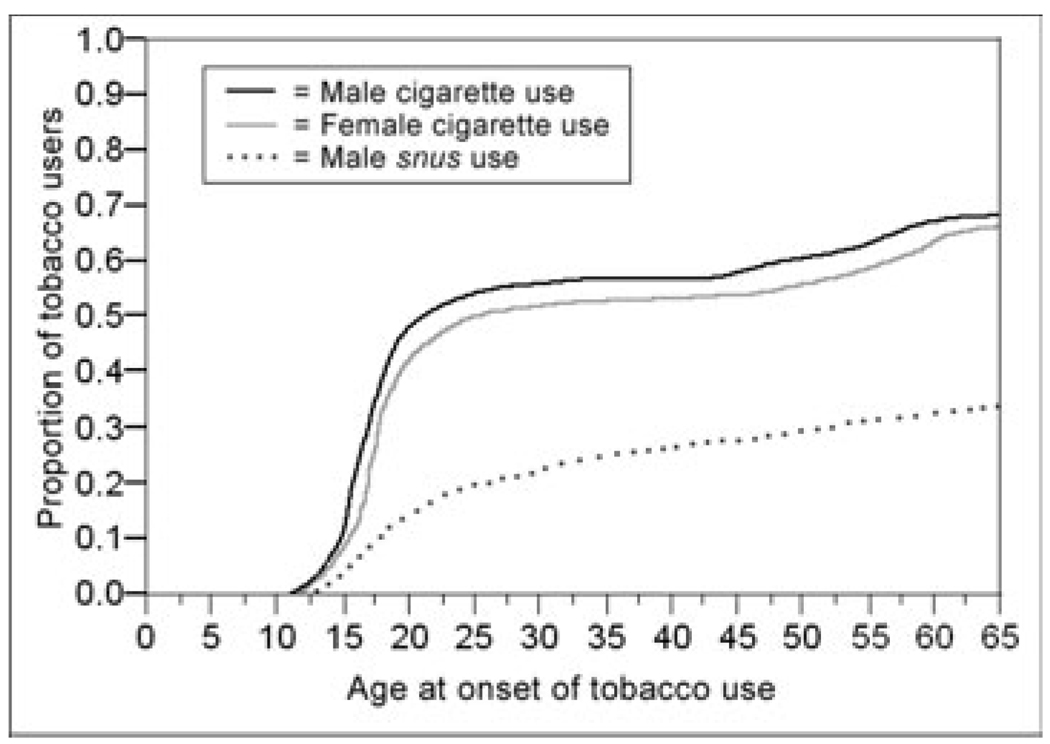

Ages at initiation of tobacco use

As shown in Fig. 1, age at onset of cigarette smoking occurred almost entirely before age 25 in this population, with an accelerated rate between 12 and 20 years of age. The median age at onset of cigarette smoking was somewhat earlier for males (16.0 years) than females (17.0 years) which is reflected in the survival curves; the curve for males is slightly above that of females. The log-rank test, which examined differences between genders within the framework of Cox’s proportional hazards model, was highly significant at P < 0.0001. Figure 1 also presents the age at onset of snus use curve among males in the STR. The median age at onset of snus use among males was 20 years. Onset of snus use occurred over a longer time span than that of cigarettes.

Figure 1.

Age at onset of tobacco use for males and females in the Swedish Twin Registry

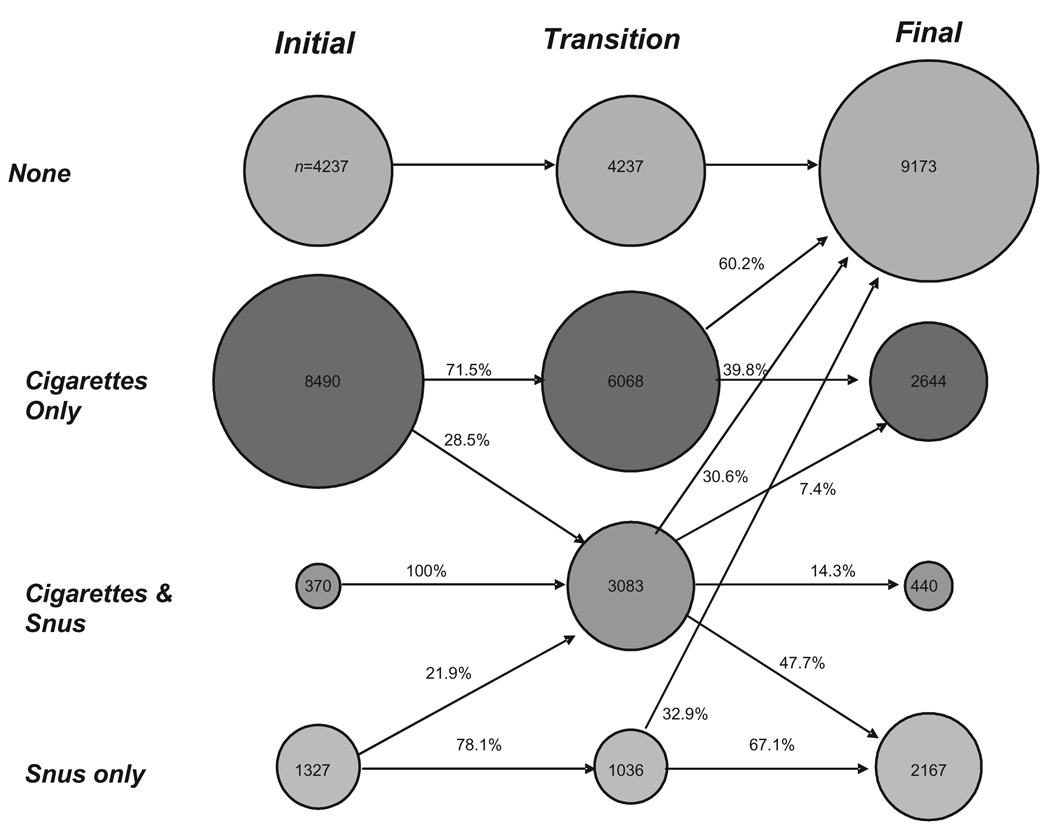

Transitions between forms of tobacco use

Figure 2 is a graphical depiction of transitions between tobacco use over time among 14 424 males in the STR. There were missing data for 390 men, who were excluded from this figure. The first column represents the type of tobacco males reported using initially (no use, cigarettes first, cigarettes and snus at the same time, and snus first), followed by a ‘transition’ column that reflects the number of men who moved from one type of tobacco use to another. Finally, the last column shows the number of tobacco users at the time of interview. The arrows between the columns depict transitions from one type of tobacco use (row) to another.

Figure 2.

Transitions between tobacco use among 14 424 males in the Swedish Twin Registry

Beginning at the upper left corner of Fig. 2, the first row of this column shows that a large proportion of men in this population reported they had never used either form of tobacco (4237/14 424 = 29.4%). As the diagram progresses to the right, the proportion of men in the sample who became non-tobacco users increased over time as a result of quitting tobacco use.

The first circle in the second row is a combination of exclusive cigarette users (71.5%) and men who began using cigarettes before they used snus (28.5%). At the time of interview, 60.2% of the men who were exclusive cigarette users had become former smokers, while 39.8% continued to smoke.

In contrasting rows two, three and four, it is evident that most men began smoking cigarettes first, rather than using snus first, or cigarettes and snus simultaneously. However, as evidenced by the larger circle in the intermediate column of row three, the proportion of men who reported a combination of cigarette and snus use increased over time. The arrows radiating from the circles indicate that the majority of men who used both cigarettes and snus either quit tobacco use altogether (30.6%) or are currently using only snus (47.7%). It was less common for men who used both cigarettes and snus to continue such practices (14.3%), and even less common for these men to quit snus and currently use only cigarettes (7.4%).

The last row of Fig. 2 depicts men who began using snus first. Only 21.9% of these men took up cigarette smoking later in life. Among men who used only snus in their lives, 67.1% were doing so at the time of interview while 32.9% of exclusive snus users had quit using snus.

DISCUSSION

Summary

In this study we have observed that the prevalence of cigarette and snus use differed dramatically by gender. Although males were more likely to have ever smoked in their life-time, females are more likely to be current smokers than males. Snus use was far more common among Swedish males than females. The ages at initiation of cigarette smoking were similar between genders; however, the slightly earlier age at initiation among males in this sample was statistically significant, given the large sample size. Men began snus slightly later in life, which was reflected in the later age at onset of snus use than of cigarette use. Finally, among men who ever used tobacco in their life-time, it was more common to start smoking cigarettes than to start with snus or both tobacco products simultaneously. Among men who reported using both cigarettes and snus during their life-time, it was far more common to quit cigarettes and currently use snus than to quit snus and currently use cigarettes. Once snus use was initiated, more men continued using snus rather than quit tobacco completely.

Comparison with previous reports

Only three studies have described transitions between cigarette smoking and snus use in Sweden, and did so among specific subgroups of people [5,23,24]. Rodu et al. described tobacco use patterns in the two northern-most counties in Sweden using data collected from different surveys at four points in time (1986, 1990, 1994 and 1999) [23]. Cigarette and snus use information was available from 2998 males and 3092 females aged 25–64 years. They reported that the prevalence of cigarette smoking among males declined from 23% in 1986 to 14% in 1999, while the use of snus increased from 22% to 30%. Among women, the prevalence of smoking remained fairly stable (~27%). The proportion of males who were former smokers was consistently higher than for females, and was associated strongly with the use of snus. Our results are generally supportive of these findings, as the prevalence of current cigarette smoking was ~26% for females and only ~22% for males. We did not investigate whether smoking status was related to snus use in this report.

Rodu et al. also performed a prospective study to describe the stability of snus use and smoking and transitions between the two utilizing tobacco use information from a subset of participants who participated in all four surveys (~70% of the original population) [5]. They found that snus use was stable, with only 2% of men switching to cigarette use and 20% quitting tobacco altogether. Smoking was less stable: 27% of smokers quit smoking and 12% used snus at the end of follow-up. Combined use of cigarettes and snus was the least stable, with 43% switching from cigarettes to snus and 6% switching from snus to cigarettes. They concluded that snus plays a major role in lowering smoking rates among men in Sweden.

In our report, we observed that among exclusive cigarette users 60.2% were former smokers, while 39.8% were current smokers. Among exclusive snus users, only 32.9% had become former snus users while 67.1% continued to use snus. Among men who reported using both cigarettes and snus in their life-time, it was far more common to quit cigarettes and continue using snus (47.7%) than to quit using snus and continue smoking cigarettes (7.4%). The patterns observed in our study are in line with those of Rodu et al. [5], as we confirmed that men were far more likely to switch from cigarettes to snus than from snus to cigarettes. However, as our data were not truly prospective we cannot conclude that snus directly affects smoking rates in Sweden. Furthermore, it is important to note that a high percentage of men who use snus exclusively or switch from cigarettes to snus are current snus users. Thus, it appears that Swedish men continue to use snus rather than quitting tobacco altogether. Future research should investigate whether it is harder to quit using snus than cigarettes by assessing quit attempt histories and nicotine dependence among different types of tobacco users.

Finally, in their study among 18–34-year-old Swedish men, Ramström et al. reported that among those who started tobacco use with cigarettes, 40% switched to snus while the other 60% continued smoking [24]. Only 25% of men who started with snus switched to cigarettes in their study. We observed similar patterns; among those who started tobacco use with cigarettes, 28.5% switched to snus while the other 71.5% continued smoking. Approximately 22% of men who started with snus switched to cigarettes. Our report extends these findings by reporting that among men who reported using both cigarettes and snus in their life-time, 30.6% quit all forms of tobacco, 14.3% continued using both, and only 7.4% quit using snus and continued smoking cigarettes. The majority of men who reported using both forms of tobacco quit cigarettes but continued using snus (47.7%).

Study strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study include its population-based design, representing a wide age range (42–64 years) of males and females, the detailed assessment of cigarette and snus use which permitted us to construct tobacco use histories for each tobacco user and, most notably, the large sample size, which was nearly six times larger than previous studies to date. Although twins tend to have higher morbidity and mortality during the first year of life than singletons and comprise only 1–2% of the adult population, there is compelling evidence that data from twins are generalizable to the general population and are a sound resource for epidemiological investigations [26]. Evans & Martin [31] concluded that twins are representative of the general population with respect to most health and behavioral outcomes, as twins exhibit similar means, frequencies and prevalences as singeltons for many traits and adult diseases.

The limitations of this study are acknowledged. As all tobacco use data were obtained through self-report, it is possible for recall bias to have affected our findings. Tobacco use histories were constructed based upon ages at initiation of tobacco use, which may be more difficult for older respondents to remember. However, there are no reasons to suspect that participants would recall their uses of cigarettes and snus use differently. Nor would one expect that males and females recall tobacco use histories in a different manner. It is reassuring that the proportions of cigarette smoking and snus use were similar to those in previous reports. Thus, our concern for differential misclassification error affecting these results is minimized. If non-differential misclassification of tobacco use had affected our findings, they would have biased our results towards the null [32]. We also acknowledge that quitting was not confirmed, and it was not known how long former smokers have been abstinent.

At this time, the generalizability of our findings is limited because snus is available (sold legally) only in Sweden, and other oral smokeless tobacco products consumed in other parts of the world, such as the United States or India, are very different from snus with respect to their pharmacological properties and effects on health [7]. In our recent paper, which reported that snus was associated with smoking cessation and not smoking initiation [33], we suggested that clinical trials should be conducted to evaluate snus as another form of nicotine replacement therapy. From a harm reduction perspective, should snus be shown to be as effective as or superior to existing nicotine replacement therapies, it may represent a more acceptable means by which to reduce the tobacco-related health burden.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we found that current cigarette smoking is more prevalent among Swedish women than men, while snus use is far more prevalent among men than women. Age at onset of cigarette smoking occurred almost entirely before age 25 in this population, with an accelerated rate between 12 and 20 years of age for both genders. The age at onset of snus use among males occurred over a longer time period. It appears that Swedish men are taking up snus later in life, perhaps as a way to help them to quit smoking. However, once snus use is started, men tended to continue using snus rather than quit tobacco completely. Future research should evaluate the ramifications of snus use in Sweden, with special emphasis on quit rates among snus users and the health effects of long-term snus use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US National Cancer Institute (CA085739 to PFS). The funding source had no involvement in study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, and was not involved in the decision to submit this paper for publication.

References

- 1.Fiore MC. Treating tobacco use and dependence: an introduction to the US Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline. Respir Care. 2000;45:1196–1199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fagerstrom KO, Schildt EB. Should the European Union lift the ban on snus? Evidence from the Swedish experience. Addiction. 2003;98:1191–1195. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wersall JP, Eklund G. The decline of smoking among Swedish men. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:20–26. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molarius A, Parsons RW, Dobson AJ, Evans A, Fortmann SP, Jamrozik K, et al. Trends in cigarette smoking in 36 populations from the early 1980s to the mid-1990s: findings from the WHO MONICA Project. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:206–212. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodu B, Stegmayr B, Nasic S, Cole P, Asplund K. Evolving patterns of tobacco use in northern Sweden. J Intern Med. 2003;253:660–665. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curvall M, Romert L, Norlen E, Enzell CR. Mutagen levels in urine from snuff users, cigarette smokers and non tobacco users—a comparison. Mutat Res. 1987;188:105–110. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(87)90098-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foulds J, Ramstrom L, Burke M, Fagerstrom K. Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:349–359. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Osterdahl BG, Jansson C, Paccou A. Decreased levels of tobacco-specific N-nitrosamines in moist snuff on the Swedish market. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:5085–5088. doi: 10.1021/jf049931a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holm H, Jarvis MJ, Russell MA, Feyerabend C. Nicotine intake and dependence in Swedish snuff takers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1992;108:507–511. doi: 10.1007/BF02247429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewin F, Norell SE, Johansson H, Gustavsson P, Wennerberg J, Biorklund A, et al. Smoking tobacco, oral snuff, and alcohol in the etiology of squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a population-based case-referent study in Sweden. Cancer. 1998;82:1367–1375. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980401)82:7<1367::aid-cncr21>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schildt EB, Eriksson M, Hardell L, Magnuson A. Oral snuff, smoking habits and alcohol consumption in relation to oral cancer in a Swedish case–control study. Int J Cancer. 1998;77:341–346. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980729)77:3<341::aid-ijc6>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ye W, Ekstrom AM, Hansson LE, Bergstrom R, Nyren O. Tobacco, alcohol and the risk of gastric cancer by sub-site and histologic type. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:223–229. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991008)83:2<223::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Lindgren A, Nyren O. The role of tobacco, snuff and alcohol use in the aetiology of cancer of the oesophagus and gastric cardia. Int J Cancer. 2000;85:340–346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boffetta P, Aagnes B, Weiderpass E, Andersen A. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of cancer of the pancreas and other organs. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:992–995. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolinder G, Alfredsson L, Englund A, de Faire U. Smokeless tobacco use and increased cardiovascular mortality among Swedish construction workers. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:399–404. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.3.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huhtasaari F, Asplund K, Lundberg V, Stegmayr B, Wester PO. Tobacco and myocardial infarction: is snuff less dangerous than cigarettes? BMJ. 1992;305:1252–1256. doi: 10.1136/bmj.305.6864.1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huhtasaari F, Lundberg V, Eliasson M, Janlert U, Asplund K. Smokeless tobacco as a possible risk factor for myocardial infarction: a population-based study in middle-aged men. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;34:1784–1790. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00409-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asplund K. Smokeless tobacco and cardiovascular disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2003;45:383–394. doi: 10.1053/pcad.2003.00102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hergens MP, Ahlbom A, Andersson T, Pershagen G. Swedish moist snuff and myocardial infarction among men. Epidemiology. 2005;16:12–16. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000147108.92895.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramstrom L. Patterns of use: a gate leading to smoking or a way out? Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2003;5:268. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bates C, Fagerstrom K, Jarvis MJ, Kunze M, McNeill A, Ramstrom L. European Union policy on smokeless tobacco: a statement in favour of evidence based regulation for public health. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:360–367. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.4.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henningfield JE, Fagerstrom KO. Swedish Match Company, Swedish snus and public health: a harm reduction experiment in progress? Tobacco Control. 2001;10:253–257. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rodu B, Stegmayr B, Nasic S, Asplund K. Impact of smokeless tobacco use on smoking in northern Sweden. J Intern Med. 2002;252:398–404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramstrom L. Snuff-an alternative nicotine delivery system. In: Ferrence R, editor. Nicotine and Public Health. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2000. pp. 159–178. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pedersen NL, Lichtenstein P, Svedberg P. The Swedish Twin Registry in the third millennium. Twin Res. 2002;5:427–432. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lichtenstein P, De Faire U, Floderus B, Svartengren M, Svedberg P, Pedersen NL. The Swedish Twin Registry: a unique resource for clinical, epidemiological and genetic studies. J Intern Med. 2002;252:184–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/Genetics® User’s Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stokes D, Koch GG. Categorical Data Analysis Using SAS. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cox DR. Analysis of Survival Data. London: Chapman & Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: a practical guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Evans DM, Martin NG. The validity of twin studies. Genescreen. 2000;1:77–79. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furberg H, Bulik C, Lerman C, Lichtenstein P, Pedersen N, Sullivan P. Is Swedish snus associated with smoking initiation or smoking cessation? Tobacco Control. 2005;14:422–424. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.012476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]