ABSTRACT

Purpose: To describe international clinical internships (ICIs) for Canadian physical therapy (PT) students, explore the experiences of individuals involved in ICIs, and develop recommendations for future ICIs based on these findings.

Methods: This study employed a mixed-methods approach. An online questionnaire surveyed academic coordinators of clinical education (ACCEs, n=14) on the availability, destinations, and number of ICIs from 1997 to 2007. Semi-structured telephone interviews were then conducted with eight PT students, seven ACCEs, and three supervising clinicians to investigate their ICI experiences. Interview transcripts were coded descriptively and thematically using NVivo.

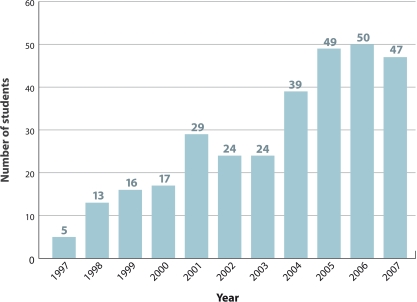

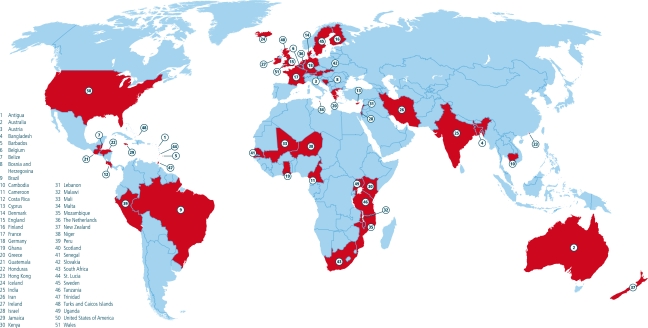

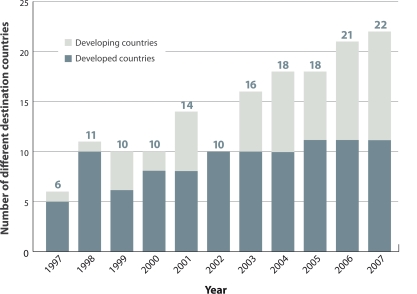

Results: ICIs are currently available at 12 of 14 Canadian PT schools. A total of 313 students participated in ICIs in 51 different destination countries from 1997 to 2007. Over this period, increasing numbers of students participated in ICIs and developing countries represented an increasing proportion of ICI destinations. Key themes identified in the interviews were opportunities, challenges, and facilitating factors.

Conclusions: ICIs present unique opportunities for Canadian PT students. Recommendations to enhance the quality of future ICIs are (1) clearly defined objectives for ICIs, (2) additional follow-up post-ICI, and (3) improved record keeping and sharing of information on ICI destination countries and host sites.

Key Words: clinical education, global health, international clinical internships, mixed methods, physical therapy

RÉSUMÉ

Objectif : Décrire les stages cliniques internationaux pour les étudiants en physiothérapie canadiens, explorer les expériences vécues par les personnes qui ont participé à de tels stages et formuler des recommandations pour les futurs stages internationaux à partir des constatations obtenues.

Méthode : Cette étude a eu recours à des méthodologies mixtes. Un questionnaire en ligne a permis d'effectuer un sondage auprès de coordonnateurs de la formation clinique des universités (CFCUs, n=14) portant sur la disponibilité, les destinations et les quantités de stages internationaux disponibles de 1997 à 2007. Des entrevues téléphoniques semi-structurées ont ensuite été réalisées auprès de 8 étudiants en physiothérapie, de 7 coordonnateurs de la formation clinique en milieu universitaire et de 3 cliniciens superviseurs de stage afin d'en savoir plus sur leur expérience de tels stages. La transcription de ces entrevues a été codée par description et par thème à l'aide du logiciel NVivo.

Résultats : Des stages cliniques internationaux sont présentement offerts dans 12 des 14 écoles de physiothérapie au Canada. Au total, de 1997 à 2007, 313 étudiants ont pris part à de tels stages, qui ont eu lieu dans 51 pays. Au cours de cette période, un nombre croissant d'élèves ont participé à des stages cliniques internationaux. Les stages dans des pays en développement forment une plus grande proportion des destinations pour ces types de stages. Les grands thèmes évoqués dans les entrevues ont été les possibilités offertes par de tels stages, les défis et les facteurs favorables.

Conclusions : Les stages cliniques internationaux offrent des chances uniques aux étudiants en physiothérapie canadiens. Les recommandations formulées pour l'amélioration de ces stages sont les suivantes : (1) définir plus clairement les objectifs poursuivis par ces stages; (2) assurer un suivi supplémentaire après ces stages; (3) améliorer la tenue de dossiers et le partage de l'information sur les pays hôtes et sur les lieux où se déroulent ces stages.

Mots clés : formation clinique, méthodes mixtes, physiothérapie, santé globale, stages cliniques internationaux

INTRODUCTION

Global health is an increasingly important area of study and practice for physical therapists. Global health draws on a philosophy of health and human rights and seeks to provide a certain standard of health and health care for individuals worldwide.1 Global health addresses the impact of factors beyond government agencies and non-governmental organizations and involves considering the health needs of people worldwide above the concerns of particular nations.2 The global health landscape has changed in the last decade, largely as a result of globalization; such changes include increased income inequality and poverty, both of which are related to disability and affect the accessibility and delivery of health care, in both developed and developing countries.2–6 Physical therapy (PT) may have a unique role in addressing disability and its relationship to poverty through rehabilitation and mobility.5 Furthermore, it has been suggested by the World Confederation for Physical Therapy (WCPT) that, as health professionals, “physical therapists are obliged to work toward achieving justice in the provision of health services for all people.”7(p.6) In order to meet the future challenges facing PT as a profession with global responsibilities, physical therapists need to receive relevant education that prepares them to work internationally and establishes a core foundation of social responsibility.3,8 The profession's growing role in global health requires entry-level education that emphasizes not only clinical competence but also adaptability, problem solving, and an understanding of the impact of globalization on health systems and individual wellness.3,9

One strategy to prepare PT students for their future professional responsibilities is through clinical internships in other countries. An international clinical internship (ICI) can be defined as any clinical internship completed anywhere outside Canada by a PT student as part of his or her formal clinical education through a Canadian PT programme. Clinical internships are essential for the consolidation of theoretical knowledge and practical skills for PT students;10 ICIs may also provide opportunities for students to gain an appreciation for cultural differences in perceptions of health and illness and to experience different models of health care delivery.5,9 In addition to providing work experience in an international setting, ICIs may also prepare PT students for work in the changing ethno-cultural background of Canada. Between 2001 and 2006, the number of Canadian residents born outside of Canada grew by 13.6%, and in 2006, one in five Canadian residents were foreign born.11 Additionally, the delivery of health care in Canada is influenced by global health issues, particularly as increased international travel brings people from around the world to Canada.12 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is a notable example of how global health issues affect Canadians, with devastating consequences on health care systems, patients, and health care providers.13 An integral objective of international clinical experience is to allow students to adapt their knowledge, skills, and professional behaviour to unfamiliar situations within unique cultural and ethical frameworks.5,14

Jung et al. have described international experiences for PT students' ICIs within a single university programme,14 and other authors have outlined the importance of incorporating international themes in PT curricula, including fostering an appreciation of globalization and the political context of health care.3,9 However, there is no published research that specifically addresses ICIs as part of PT clinical education. Understanding the ICI experiences of PT students may give Canadian PT educational institutions a crucial starting point from which to define their role. Despite the lack of research specifically involving PT students, evidence supporting international clinical experience (ICE) as part of formal education for medical and nursing students has been encouraging, showing a positive impact on personal and professional development.14–20 The supporting literature from the medical and nursing professions has included ICE in both developed and developing countries. Global health experience in developing environments has been shown to expose students to clinical situations and patient relationships different from those they typically experience in developed settings.1,21 Following ICEs, nursing students reported gaining an appreciation of the strengths and weaknesses of their own country's health care system as well as insights into disparities in global health care systems.16 Medical and nursing students also reported a greater awareness of cultural differences, as well as increased self-confidence, self-awareness, coping skills, and leadership skills.14,16 As a positive demonstration of the lasting effects of such experiences, nursing students who participated in international education were more likely to continue to pursue international experiences in their future employment, volunteer, and education opportunities.17,18

Canadian PT students may benefit from ICIs in ways that parallel the positive effects demonstrated for students in other health professions; however, ICI experiences for Canadian PT students have yet to be examined. The present study addresses this gap in the literature by describing the history, current trends, and future implications of ICIs in Canadian PT clinical education. The research objectives were (1) to describe the history and current status of ICIs for Canadian PT students; (2) to explore the opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned regarding ICIs for Canadian PT students from the perspectives of ACCEs, students, and supervising clinicians involved in ICIs; and (3) to determine the implications for future ICI programmes for Canadian PT students and for future research. This information may be used to further develop clinical education programmes that address the new and evolving roles of Canadian physical therapists, both in Canada and abroad.

METHODS

A mixed-methods approach was used to allow for the combination of both predetermined and emergent approaches to data collection and analysis.22 A questionnaire consisting of closed-ended questions was developed to address the first research objective, enabling the investigation of predetermined outcomes of interest.22 Key-informant interviews were conducted to address the second research objective, enabling the interpretation of phenomena and of the meanings people bring to them.23 Qualitative approaches have also been identified as useful in research investigating process-related features of clinical education.24 Results from both quantitative and qualitative data were synthesized to address the third research objective. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Toronto.

Survey

An Internet-based, self-administered questionnaire was developed to collect descriptive information on the history and current state of ICIs in Canadian PT programmes from 1997 through 2007. The electronic format was selected to maximize convenience for participants.25

Participants and Recruitment

ACCEs from all 14 Canadian PT programmes were selected to complete the survey because of their access to information on clinical internships at their institutions. Each ACCE initially received an e-mail inviting him or her to participate in the study through the National Association for Clinical Education in Physiotherapy (NACEP). Following development and piloting of the questionnaire in January 2008, a second e-mail was sent to each ACCE with the information required to provide informed consent and a link to the questionnaire.

Data Collection

Results from each respondent were assigned an identification number, and responses were collected and organized using the questionnaire software SurveyMonkey (SurveyMonkey.com, Portland, OR; see Appendix A for a copy of the questionnaire).

Data Analysis

A descriptive quantitative analysis was performed on the results of the questionnaire. The variables of interest were the number, destinations, and durations of ICIs per year; eligibility criteria; and the presence/absence and level of financial support for Canadian PT students on ICIs. Destination countries were categorized as “developed” or “developing”; for the purposes of this study, “developing countries” were defined as developing and emerging economies as identified by the International Monetary Fund in its World Economic Outlook database.26

Key-informant Interviews

Semi-structured one-on-one telephone interviews were then conducted between March and July 2008 to explore the perceptions and experiences of ACCEs, former students of Canadian PT programmes who participated in ICIs, and clinicians who supervised Canadian PT students during ICI experiences.

Participants and Recruitment

ACCEs were recruited for interviews following completion of the questionnaire. To maintain anonymity, interview participation was not linked to questionnaire responses. Former students of Canadian PT programmes and supervising clinicians were recruited to participate in interviews via electronic mailing lists through the International Health Division of the Canadian Physiotherapy Association, the working groups of the International Centre for Disability and Rehabilitation at the University of Toronto, and online forums of the World Confederation for Physical Therapy. All students and supervising clinicians who expressed interest were contacted, and interviews were scheduled at their convenience. Snowball sampling was employed, meaning that each interview participant was asked to identify others who had experienced ICIs as students or as supervising clinicians. Individuals identified through this process were contacted with study information and were invited to participate in interviews.

Data Collection

The semi-structured one-on-one telephone interviews were conducted by three investigators. Pilot interviews were conducted with one ACCE and one student to inform modifications to the interview guide. Prior to the telephone interview, participants were sent information about the study as well as an informed consent document. Once the participant had been reached by phone, the investigator reviewed the informed consent document with the participant. Interviews lasted approximately 1 hour and were conducted in English or French as preferred by the participant. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, with identifiers removed, for analysis. Interviewers also took detailed field notes. Open-ended questions in an interview guide were used to explore each participant's experience of opportunities, challenges, and lessons learned from ICIs (see Appendix B).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using an inductive, constant comparative approach to describe and identify key themes. Transcripts were systematically coded descriptively and then thematically using NVivo (QSR International Inc, Cambridge, MA). First, two investigators independently completed open coding of one transcript; they then met to develop an initial list of descriptive codes. One investigator completed descriptive coding of all transcripts, and 50% of transcripts were double-coded by one of three other investigators. Each transcript was also read by all investigators. All investigators met to review coding categories, identify key concepts and emerging themes, and group these concepts into broader themes and sub-themes.

RESULTS

The results from the survey and the key-informant interviews are presented separately.

Survey

All 14 ACCEs completed the questionnaire. Respondents reported on ICIs that had taken place from 1997 to 2007 at their respective PT programmes. Of the 14 programmes surveyed, 12 (86%) reported that ICI opportunities were available to students and 2 (14%) reported they were not available. The earliest reported ICI was in 1984; however, seven respondents (58%) did not know when ICIs were first coordinated at their institutions.

A reported total of 313 students participated in ICIs between 1997 and 2007; the overall number of students increased across years (see Figure 1). Students who took part in ICIs represent only 4% of the 7,213 individuals who graduated from Canadian PT programmes between 1997 and 2007.27,28 In total, 51 different countries (22 developed and 29 developing countries) were reported as ICI destinations (see Figure 2). The number of different destination countries for ICIs reported each year increased more than threefold during the time period examined (see Figure 3). Developing countries also increased as a proportion of the total (see Figure 3), from almost 17% of ICI destinations in 1997 to 50% in 2007. The reported duration of ICIs ranged from 4 to 8 weeks; most ICIs lasted 5 weeks.

Figure 1.

Number of students participating in ICIs, 1997–2007

Figure 2.

ICI destination countries, 1997–2007

Figure 3.

Number of different ICI destination countries, 1997–2007

ACCEs also reported a variety of requirements for students to participate in an ICI (see Table 1). The majority of respondents (83%) reported that PT students were required to be supervised by an on-site physical therapist. Other supervisory models reported were “virtual” supervision online by a physical therapist or university faculty member and supervision by an on-site health care professional from another discipline (e.g., nurse, physician). All respondents reported that students were responsible for the costs associated with the ICI. Seven respondents (58%) reported that some financial aid was available to ICI students. Financial aid was not available at four schools and was reported as “unknown” by one respondent. Of respondents who reported that financial aid was available to ICI students, the amount available was CAD$101–$500 at two schools, CAD$501–$1000 at three schools, and CAD$1001 or more at two schools. The sources for this funding were reported to be the academic institution, the provincial government, non-governmental organizations within Canada, and private sources located by the students (e.g., Rotary Club, a local church).

Table 1.

Reported requirements for students to participate in ICI

| Reported Requirements | % Respondents |

|---|---|

| No previous history of academic concerns | 100 |

| Must have successfully completed at least one previous clinical internship | 66.7 |

| Minimum overall grade requirement for programme | 58.3 |

| Must be in last year of programme | 58.3 |

| Personal essay or letter of intent | 50.0 |

| Reference letters | 33.3 |

| Must demonstrate evidence of particular interpersonal skills | 33.3 |

| No criminal record | 25.0 |

| Minimum grade requirement in course content specific to ICI | 16.7 |

| Interview process | 8.3 |

| Application form | 8.3 |

| Must submit background work regarding the placement, including budget and international contacts | 8.3 |

| Final clinical internship | 8.3 |

| No previous failed clinical internships/successfully completed all clinical internships | 8.3 |

| Elective course in international health if ICI destination is a developing country | 8.3 |

ACCEs indicated that global or international health groups existed at seven universities and did not exist at three. An example of such a group is the International Centre for Disability and Rehabilitation at the University of Toronto. The remaining four ACCEs did not know whether or not such a group existed at their institutions. Global and international health topics (e.g., international models of health care delivery) were included in the PT programme curriculum at five universities and were not included at another five; the remaining four ACCEs did not know whether these topics were included in their institutions' curricula.

Key-informant Interviews

A total of 18 one-on-one interviews were conducted during the study. Interview participants included seven ACCEs, eight former students of Canadian PT programmes who completed an ICI, and three supervising clinicians. Of the eight former students, three had travelled to developed countries and the remaining five to developing countries; all had completed their ICIs between 1999 and 2007. Two supervising clinicians were Canadian physical therapists practising abroad, and the other was a physical therapist trained and employed outside of Canada. Three key themes and associated sub-themes relevant to the research questions were identified: opportunities, challenges, and facilitating factors (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Key themes and sub-themes

| Key Themes | Sub-themes |

|---|---|

| Opportunities |

|

| Challenges |

|

| Facilitating factors |

|

Opportunities

Interview participants reported beneficial learning opportunities during international clinical experiences. In particular, these opportunities were expressed as broadening perspectives, helping host communities, and applying learning to future practice.

The opportunity for broadening perspectives was expressed in several different ways. Participants from all groups reported that ICIs placed students in different cultural contexts and health care delivery models, exposing them to clinical scenarios not previously seen in Canada.

Students and ACCEs reported that working in these environments gave students an appreciation of the resources afforded by the Canadian health care system. One ACCE commented,

I know the differences in the way health care is delivered in different countries and as Canadians, I think we are very privileged in our health care system and the opportunities that we have … I think it's important for our students to acknowledge that, and to be aware of that.

Inter-professional education (IPE) was another beneficial opportunity reported by ACCEs that was associated with broadening students' perspectives. They reported that some students had the opportunity to complete an ICI with students from other health faculties at the same university, such as nursing or occupational therapy. As well, some PT students had the opportunity to work alongside, or to be supervised by, clinicians from different health professions while participating in an ICI. Such opportunities foster collaboration with other health care professionals and with local health organizations.

Interview participants also reported that ICIs offered students the opportunity to experience health care delivery designed to help meet the needs of the host community. Some ICIs were structured around specific community health interests, such as HIV/AIDS or disability. Students reported participating in health-education and health-promotion workshops as well as working alongside international health groups to reach larger populations of people and their families. These opportunities to assist host communities helped students to broaden their perspectives on the role of community health education and health promotion and to advocate for the role of physical therapy at the community level. One ACCE noted,

I guess that the other thing is like we believe really, really strongly here that physios need to play a much bigger role in health promotion and disease prevention. And so … in developing countries we don't necessarily see so much that we're sending the student over there to treat sprained ankles or frozen shoulders, as they are to see what is health? What is clean water? What is housing? … What does it take to have a healthy community? And what can your physio knowledge contribute to promoting health, preventing injury?

Skills and learning experiences that can be applied to future practice are yet another reported benefit to ICIs. Students who participated in ICIs reported having improved confidence in applying clinical skills within resource limited environments:

I think that it helped to make me a little bit more creative as a therapist … because of the lack of resources and equipment and stuff like that you really have to come up with new ways and new techniques.

Developing cultural competence and an understanding of determinants of health was reported by ACCEs as a reason for offering ICIs:

So we actually sort of believe that if you can go to a developing country and see some of … some of the health disparities and the determinants of health, and act on them, that we're hoping students will make connections to some of the communities we have right at home in our own province.

Bringing lessons learned back to Canada, or applying these lessons to future international work, was reported as a positive outcome of ICIs. As well, students reported that they felt more culturally sensitive following their experiences and that this sensitivity persisted when they returned to Canada.

Challenges

Participants reported facing challenges during the organization of internships, during the internship experience itself, and during the post-internship period once the student had returned to Canada. Specifically, challenges were expressed in the areas of initially arranging the internship, risks and uncertainty, cultural differences the students were exposed to, and lack of follow-up.

In terms of organizing the internships, participants reported difficulty in finding a host site, particularly for student-initiated ICIs, as noted by this student:

There were a few students who had gone the year before on international placements and there was some information on their experiences … I tried to follow up on one of them but I never got any information back, so I just ended up searching on my own for most of it.

Another challenge associated with the process of organizing the internship was difficulty in communicating with host sites and receiving signed site-affiliation agreements. Participants reported that in some settings access to e-mail was quite limited and the postal system was unreliable. Interestingly, ACCEs reported difficulties in arranging internships for students wanting to go the United States because of visa issues after September 11, 2001.

Funding was also addressed by all three groups as a challenge associated with organizing ICIs. Although several ACCEs reported that some funding was available to students through various groups and organizations, students reported having to cover all costs associated with their ICI. In addition to financial resources, both students and ACCEs noted that ICIs required great effort to organize. ACCEs reported that the effort required to plan ICIs must be justified by the benefits to the student and the PT programme.

Potential safety risks—including political instability, natural disasters, and violence—were identified as a concern for both ACCEs and students. Students also reported challenges in trying to plan for the unknown, feeling unprepared, experiencing a lack of control, adapting to a new situation, and coping with unexpected events:

I thought I had an idea of, like, what we were going through, beforehand. But no matter how much we prepared … you can never be prepared. Like, there's always a curve ball or always something, you know, thrown in your way once you get there.

Potential difficulties in the relationship between students and CIs were also identified as concerns by all participant groups. While similar problems could arise during clinical internships in Canada, they were seen as a greater challenge in ICIs because the student was farther away from the support of the ACCE and the home institution. In addition, students and ACCEs reported risks associated with the possibility that an ICI would not meet programme requirements for graduation. There is inherent uncertainty associated with ICIs, which can cause anxiety for all groups involved and negatively affect the quality of the experience.

Adapting to cultural differences was a challenge for some students. These differences included clinical practice in areas of extreme poverty and cultural differences in beliefs about disability. One student commented,

Obviously the culture shock. That was one thing that was kind of dramatic for me, like, I've never been outside, like, the Western world, and going to a developing country, that took a little while to get used to.

Language barriers were also identified as a challenge, as was working with translators to communicate with co-workers, patients, and patients' families. Dealing with differences in clinical practice was perceived to be challenging as well: for example, adjusting to a lack of privacy and confidentiality, lower standards for record keeping, and use of different terminology. Students whose ICIs took place in developed countries, such as Australia, reported minimal challenges with respect to cultural differences.

All three groups of interview participants reported the need for additional follow-up after the completion of ICIs. One student noted,

Part of learning is learning from each other, and being able to share experiences … Especially if a student encountered something that they've never experienced before … then how much more learning and insight can you gain if you don't have anyone to talk to about that? … I'm not sure how a school would go about doing that, but I do think it's a good idea.

Some of the difficulties with follow-up were related to the timing of ICIs within the PT programme, particularly when the ICI constituted a student's final placement and represented the end of his or her professional education. Most ACCEs reported engaging the students in some sort of post-ICI debriefing or presentation; however, it was believed that additional follow-up activities could provide more information to the ACCE about the quality of the ICI and help to develop a relationship with the host site. ACCEs stated that inadequate record keeping made it difficult to report on the history of ICIs at their institution. They also felt that having thorough records on the history of ICIs at their institution would allow them to better evaluate previous students' experiences and that such information would be valuable in organizing future ICIs.

Facilitating Factors

Participants identified specific facilitating factors that enhanced the success of the experience of ICIs, including personal qualities of the student, peer support, preparation activities, and an ongoing relationship between the school and the host site.

Participants felt that to have a successful ICI experience, students should be adaptable. Being open-minded and flexible was seen to help students cope with cultural differences, differences in clinical practice, and unpredictable situations.

Students were also perceived to benefit from perseverance, especially with respect to the challenges and length of time associated with organizing ICIs. Strong clinical skills and academic success were considered important in facilitating a successful ICI, as well as being a prerequisite for participating in ICIs. The perceived importance of clinical and academic achievement was also a reason that participants recommended making the ICI the final placement in the student's PT education, as noted by one supervising clinician:

I think because it was her final placement … that was really important, that she had developed skills to be able to, to, work in a more challenging environment.

As well, such qualities allow students to be positive representatives of their universities and of Canadian physical therapists while on ICIs. One ACCE noted,

We want to make sure that they're going to represent the university well in an international setting, because certainly that can set the tone for future students, and also, you know, it's sort of our reputation at stake, so to speak.

The availability of peer support for students participating in ICIs was also seen as a facilitating factor. Having more than one student participating together in an ICI was believed to foster collaborative learning and to provide support in adapting to a new environment. One ACCE commented,

We prefer that if students are going to countries, especially those with significantly different cultures, that they go as a pair. So we prefer that because then … they have someone who speaks their language, they can have someone to … be homesick with … just to bounce ideas off of.

All participants reported preparation activities as important in making ICIs successful. Seeking out information and resources prior to the ICI was reported to be beneficial, as was talking to people with prior experience in the destination country. One student commented,

Talking to people who had gone before … I mean the little things were really helpful, like what the food was going to be like when you went there, what the days were going to be like. And what your living quarters would be like. 'Cause you really have no idea if no one would tell you. And then just the patients; what kind of patients you'd expect to see.

ACCEs identified processes in place at their universities to help prepare students for their ICIs. ACCEs reported hosting information sessions for students to describe opportunities for ICIs as part of clinical education. These sessions took place well in advance of the placement date, to allow sufficient preparation for all involved. As well, some ACCEs reported that students participating in an ICI were required to attend pre-departure orientation sessions or an elective course in international health. Participants also felt that learning about the destination country and learning some of the language of the host community were helpful. One ACCE noted,

The students have to come up with a contingency plan, in case something should go wrong while they are on placement, whether it be they are either injured or something happens in the country, if it is in a developing country with respect to political unrest or earthquakes, floods, or … anything like that.

Participants felt that the presence of an ongoing relationship between the PT school and the host site facilitated the process of organizing future ICIs and minimized the risks involved in the internships. Established exchanges were seen to facilitate ICIs, as they require less work to organize on the part of both the ACCE and the student. Also, an established relationship between the PT school and the host site or institution allowed ACCEs, in particular, to be more certain about the quality and safety of the ICI. ICIs involving IPE experiences organized by the university were also a way of assuring quality and safety.

DISCUSSION

History and Current Trends

Despite increasing numbers of students participating in ICIs over time, only a minority of all PT students involve themselves in ICIs. Regardless of the relatively small numbers of students participating in ICIs, there has been an overall shift toward a more formalized process of organizing ICIs, as demonstrated by (1) scheduled ICI education information sessions presented by ACCEs to students during class time, (2) the existence of clear eligibility criteria for students, and (3) the presence of established international exchange programmes with international universities and in collaboration with international health interest groups. Despite this shift, however, only a few PT programmes include global health topics in their curricula, and the existence of international health interest groups was reported at only half the institutions surveyed. These findings suggest that international clinical education is still evolving as part of PT programmes nationally.

The increasing numbers of students travelling to developing countries and the incorporation of inter-professionalism are evidence that the ICI experience is evolving. Consequently, the learning objectives of ICIs may need to change to reflect the unique opportunities presented by these two trends. ICIs in developing countries may present unique opportunities for students to develop a greater appreciation for cultural differences, resource management, and community health needs. Our findings suggest that ICIs in developing countries may be beneficial to PT students both because the skills and experiences gained in these internships can contribute positively to their personal and professional development and because students develop more interest in and gain a better appreciation of health issues affecting developing communities. Similarly, research has demonstrated that international health experiences help students in other health disciplines to acquire knowledge and skills relevant to appreciating patients' cultural differences, the multi-factorial influences on health, problem-solving skills, and evidence-based medicine.17,19–21 Research also suggests that international education opportunities foster an appreciation for the impact of globalization on health care delivery and help strengthen the commitment to practice in under-served areas.18,21

Our findings suggest that whether students worked alongside or were supervised by members of other health professions, ICIs incorporating IPE were positive learning experiences. Research has demonstrated that IPE has led to improved communication among health professionals, which facilitates goal setting and clarifies patient objectives, ultimately improving patient care.29 Collaboration between professionals can also increase cultural knowledge and provide solutions in situations where cultural differences affect health care delivery.30,31 ICIs allow student exposure to global health issues in settings where inter-professional relationships can enhance the successful delivery of health care. To our knowledge, however, the combination of IPE and ICI experiences has not yet been investigated in research.

Our findings suggest that follow-up activities for students and PT programmes are an important component of the ICI experience. Follow-up activities that currently exist for students following ICIs include debriefing sessions with ACCEs to discuss and reflect on the ICI and presentations by students to share their ICI experiences with others. For many students, ICIs take place at the end of the PT curriculum, and formal follow-up activities are not always possible. Establishing formal follow-up opportunities for students, and building on the follow-up activities that already exist, could enable students and ACCEs to discuss opportunities and challenges experienced during the ICI, allowing for improved ability to develop specific future preparatory activities, learning objectives, and relevant contingency plans. Follow-up activities for students also provide an opportunity to engage in “reflection on action,” in which students consider challenging situations that occurred during their clinical experience.32 Structured time for reflective practice following ICIs could contribute to students' professional development; through this reflection, students can identify areas of strength and areas for improvement, as well as developing an action plan for the future.33

Limitations

An important component of follow-up for PT schools is keeping records of past ICIs. The limited nature of the formal record-keeping systems currently in place has potential effects on both the resources available to schools attempting to organize ICIs and the results of this study. Record-keeping difficulties limit the ability of PT programmes to evaluate ICIs effectively and hinder the establishment of ongoing relationships with host sites. Limited record keeping and difficulty in accessing information on ICIs were identified as challenges by ACCEs during the interviews and further documented by incomplete reporting of the number of students and destination countries on the questionnaire. This lack of data limits both the quantitative and the qualitative results of our study, as our findings reflect only the information that ACCEs were able to provide. The survey allowed ACCEs to answer “unknown” when asked for the number of students participating in ICIs or the destination countries for a given year, so that they could complete the survey even if they did not have access to complete records for the entire period under study. Though ACCEs representing all Canadian PT programmes completed the questionnaire, information obtained on the history of ICIs was incomplete, and therefore we are not able to produce meaningful descriptions of ICIs at individual universities. This study represents an initial description of the history and current state of ICIs undertaken by Canadian PT students.

While we also explored the experiences of key informants, the qualitative results of the study are not meant to be generalizable to or representative of all people who have taken part in ICIs. Though half of all Canadian ACCEs participated in interviews, relatively few students and supervising clinicians were interviewed. Barriers to recruiting students included privacy restrictions at universities, which precluded the distribution of student contact information and unsolicited invitations to participate in research based in unaffiliated institutions. Recruiting supervising clinicians was particularly challenging: recruiting primarily through e-mail and online forums may have tended to exclude clinicians outside Canada who work in settings with limited access to the Internet. In addition to electronic mailing lists related to international health and physical therapy, we also employed snowball sampling. Distributing recruitment information through these outlets creates a potential recruiting bias toward individuals who have an interest in international health and favour ICI experiences for students. To facilitate recruitment of students and supervising clinicians in future studies, it would be beneficial to have access to more extensive records of students and clinicians who have taken part in ICIs.

Future Implications

Our findings suggest that future ICIs could be improved by addressing (1) the need to establish clear objectives for ICIs, (2) the need for additional post-ICI follow-up, and (3) the need for improved record keeping and sharing of information regarding ICI destination countries and host sites.

The variety of work environments and learning experiences that students are exposed to requires learning objectives that match these experiences. With clear learning objectives, all groups involved are better informed as to the overall purpose of the ICI. Ultimately, the resource-intensive process of organizing and preparing for an ICI is not only justified but facilitated by the establishment of specific learning objectives. Follow-up activities may provide information to enhance the preparation of students, PT schools, and host sites for future ICIs. Follow-up also benefits host sites, as information sharing allows ICIs to better address the host community's health care needs. In addition, follow-up assists both in establishing appropriate objectives for subsequent internships and in providing information to improve record keeping. Success in organizing ICIs, preparing students, and conducting follow-up requires a substantial amount of record keeping on the part of ACCEs. With access to information about previous student experiences, ACCEs are better able to facilitate the organization process and help future students select an ICI that meets their learning objectives. We recommend that ACCEs continue to collect information about ICIs, so that they can support future students in accessing information about positive learning opportunities and potential challenges.

To further understand and develop the ICI experience, future research should explore the impact of ICIs on the knowledge, attitudes, skills, and professional development of PT students and investigate the impact of ICIs on host communities. The effects of combining IPE and ICI experiences could also be evaluated. Opportunities exist to investigate the effects of different supervisory models (e.g., supervision by Canadian vs. international clinicians, different student-to-supervisor ratios) and of the presence or absence of peer support. International clinical education could also be compared across medical and allied health faculties at Canadian universities.

CONCLUSION

The experience of ICIs for Canadian PT students from 1997 to 2007 was positive from the perspectives of students, ACCEs, and supervising clinicians. ICIs expose PT students to unique global health issues, which is recognized as important to their professional development. ICIs help PT students to understand the significance of globalization and its effects on health care delivery, which is essential knowledge for all health care professionals. The findings of this study lend further support and encouragement to the ongoing development of ICIs as a way to provide rich educational experiences that, in turn, may more fully prepare future physical therapists for the changing landscape of clinical practice in Canada and abroad.

KEY MESSAGES

What Is Already Known on This Subject

Rehabilitation has an important role in global health, and global health issues are important for physical therapists to understand, whether they work in Canada or abroad. International student experiences have demonstrated benefits as part of clinical education in other health disciplines.

What This Study Adds

This study describes the evolution of ICIs for Canadian PT students and documents evidence of an increasing number of students and an increasing variety of destinations over time, with an increasing proportion of ICIs occurring in developing countries. There has also been movement toward integrating experiences in IPE, community development, and health promotion. This study highlights opportunities for improvement to enhance ICIs from the perspective of those involved.

Appendix A

Outline of Online Survey Used

-

What year did you begin your position as ACCE/DCE at your institution?

[Drop-down selection of years]

-

Are international clinical internships (ICI) available to physical therapy students at your institution?

[Yes/No]

-

What year did your institution first coordinate an international clinical internship for a physical therapy student?

[Drop down selection of years]

-

Please describe the number of students participating in ICIs and the average duration of their ICIs.

# of Students on ICIs Average Length of

Internship2007 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 2006 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 2005 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 2004 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 2003 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 2002 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 2001 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 2000 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 1999 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 1998 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection 1997 Drop-down selection Drop-down selection -

What were the destination countries of the ICIs?

Unknown—please explain 2007 [List of all countries] 2006 [List of all countries] 2005 [List of all countries] 2004 [List of all countries] 2003 [List of all countries] 2002 [List of all countries] 2001 [List of all countries] 2000 [List of all countries] 1999 [List of all countries] 1998 [List of all countries] 1997 [List of all countries] -

Are there eligibility criteria to participate in international clinical internships for students? (check all that apply)

None

Minimum overall grade requirement for program

Minimum grade requirement in course content specific to ICI

No previous history of academic concerns

Must be in last year of program

Reference letters

Must have successfully completed at least one previous clinical internship

Must demonstrate evidence of particular interpersonal skills

Personal essay or letter of intent

No criminal record

Other (please specify)

-

For Bachelor's programs—What year of study are students first eligible to participate in an ICI?

Not applicable—Bachelor's program not offered

1 of 4

2 of 4

3 of 4

4 of 4

-

For Master's programs—What year of study are students first eligible to participate in an ICI?

Not applicable—Master's program not offered

1 of 2

2 of 2

-

Is there a maximum number of ICIs that one particular student can participate in during their course of study?

[Yes/No]

-

Are students required to be supervised by an on site Physical Therapist during the ICI?

Yes

No, Please specify how students are being supervised

-

Are students responsible for all the costs associated with the ICI?

[Yes/No]

-

Are there financial aids available to students to support the ICI?

[Yes/No/Unknown]

-

What is the average amount of financial support per student?

$0–100

$101–500

$501–1000

$1001 or more

-

What are the sources? Check all that apply.

Your academic institution

Provincial Government

Federal Government

Community organization within Canada

Non-governmental organization within Canada

Non-governmental organization outside of Canada

Other (please specify)

-

Is there an international health interest group at your academic institution?

[Yes/No/Unknown]

-

Are global and international health topics included in your physical therapy program curriculum?

[Yes/No/Unknown]

Phase 2 of our study consists of a one-on-one telephone interview in which you would share with us your thoughts and experiences regarding student international clinical internships. The interview will not be associated with the information you have provided here. Interviews may be conducted in English or French.

-

Would you like to participate in a telephone interview?

[Yes/No]

Appendix B

Interview guide

ACCEs of PT Programs That Offer ICIs

Can you tell me about the international internship(s) you have coordinated?

Have you noticed any trends or changes over time?

Why did your school first start providing international internships?

Why does your school continue to coordinate international internships?

Can you tell me about the process of setting up the internship(s)?

Can you reflect on your experience while the students are on their international internships?

Do you feel that students have been adequately prepared for international internships?

Do you feel that the supervising clinicians and internship sites have been adequately prepared?

Can you tell me about what has happened after the internship has been completed?

Is there anything happening at your institution to encourage or discourage international internships?

What role do you see for international internships in the future?

ACCEs of PT Programs That Do Not Offer ICIs

Why does your school not offer international internships for students?

Is there anything happening at your institution to encourage or discourage international internships?

What role do you see for international internships in the future?

Students in Canadian PT Programs Who Completed ICIs

Can you tell me about the international clinical internship you participated in?

Why did you decide to do an international clinical internship?

Can you tell me about the process of setting up the internship?

What was your experience like while you were there?

How prepared did you feel for your internship?

What was your experience like after the internship?

Do you think your international internship experience has changed the way you think about PT, or about your career?

Clinicians Who Supervised ICIs for Canadian PT Students

Can you tell me about the international internship(s) and student(s) you have supervised?

Why did you decide to supervise an international internship student?

Can you tell me about the process of setting up the internship?

Can you tell me about your experience while the student was there?

Do you feel that the student was prepared for the internship?

Can you tell me about any follow-up that happened after the internship?

Crawford E, Biggar JM, Leggett A, Huang A, Mori B, Nixon SA, Landry MD. Examining international clinical internships for Canadian physical therapy students from 1997 to 2007. Physiother Can. 2010;62:261–273.

References

- 1.Pinto AD, Upshur REG. Global health ethics for students. Dev World Bioeth. 2009;9:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00209.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8847.2007.00209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown TM, Cueto M, Fee E. The World Health Organization and the transition from “international” to “global” public health. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:62–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.050831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Higgs J, Hunt A, Higgs C, Neubauer D. Physiotherapy education in the changing international healthcare and educational contexts. Adv Physiother. 1999;1:17–26. doi: 10.1080/140381999443528. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landry MD, Dyck T, Raman S. Poverty, disability and human development: a global challenge for physiotherapy in the twenty-first century. Physiotherapy. 2007;93:233–4. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alappat C, Siu G, Penfold A, McGovern B, McFarland J, Raman S, et al. Role of Canadian physical therapists in global health initiatives: SWOT analysis. Physiother Can. 2007;59:272–85. doi: 10.3138/ptc.59.4.272. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunleavy K. Physical therapy education and provision in Cambodia: a framework for choice of systems for development projects. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29:903–20. doi: 10.1080/09638280701240433. doi: 10.1080/09638280701240433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Confederation for Physical Therapy. World Confederation for Physical Therapy. Declaration of principle: ethical principles [Internet] London: The Confederation; 2007. [cited 2007 Dec 7]. Appendix; p. 3. Available from: http://www.wcpt.org/sites/wcpt.org/files/files/WCPT-DoP-Ethical_Principles-Aug07.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunt A, Adamson B, Higgs J, Harris L. University education and the physiotherapy professional. Physiotherapy. 1998;84:264–73. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9406(05)65527-7. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broberg C, Aars M, Beckmann K, Emaus N, Lehto P, Lahteenmaki ML, et al. A conceptual framework for curriculum design in physiotherapy education—an international perspective. Adv Physiother. 2003;5:161–8. doi: 10.1080/14038190310017598. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barrett K. Facilitating culturally integrated behaviors among allied health students. J Allied Health. 2002;31:93–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chui T, Tran K, Maheux H. Immigration in Canada: a portrait of the foreign-born population, 2006 census [Internet] Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2007. [cited 2009 Mar 14]. Available from: http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/english/census06/analysis/immcit/pdf/97-557-XIE2006001.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rekart ML, Rekart JT, Patrick DM, Brunham RC. International health: five reasons why Canadians should get involved. Can J Public Health. 2003;94:258–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03403546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nicholas DB, Gearing RE, Koller D, Salter R, Selkirk EK. Pediatric epidemic crisis: lessons for policy and practice development. Health Policy. 2008;88:200–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.11.006. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jung B, Larin H, Gemus M, Birnie S. International clinical placements for occupational therapy and physiotherapy students: an organizational framework. Can J Rehabil. 1999;12:245–9. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson CL, Pust RE. Why teach international health? a view from the more developed part of the world. Educ Health. 1999;12:85–9. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Button L, Green B, Tengnah C, Johansson I, Baker C. The impact of international placements on nurses' personal and professional lives: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;50:315–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03395.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harrison L, Malone K. A study abroad experience in Guatemala: learning first-hand about health, education, and social welfare in a low-resource country. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh. 2004;1:1040–56. doi: 10.2202/1548-923x.1040. doi: 10.2202/1548-923X.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy ME, Farmer S, Ravert P, Huittinen L. Institutional issues in the implementation of an international student exchange program. J Nurs Educ. 2003;42:399–405. doi: 10.3928/0148-4834-20030901-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Broome JL, Gordon JK, Victory FL, Clarke LA, Goldstein DA, Emmel ND. International health in medical education: students' experiences and views. J Health Organ Manag. 2007;21:575–9. doi: 10.1108/14777260710834355. doi: 10.1108/14777260710834355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callister LC, Cox AH. Opening our hearts and minds: the meaning of international clinical nursing electives in the personal and professional lives of nurses. Nurs Health Sci. 2006;8:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00259.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2006.00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Trehan I, Piskur JR, Prystowsky JJ. Collaboration between medical students and NGOs: a new model for international health education. Med Educ. 2003;37:1031–1031. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01642.x. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01642.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Introduction: the discipline and practice of qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The Sage handbook of qualitative research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2005. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strohschein J, Hagler P, May L. Assessing the need for change in clinical education practices. Phys Ther. 2002;82:160–72. doi: 10.1093/ptj/82.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roberts LD. Opportunities and constraints of electronic research. In: Reynolds RA, Woods R, Baker JD, editors. Handbook of research on electronic survey and measurements. Hershey, PA: Idea Group Reference; 2007. pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Monetary Fund. World economic outlook: housing and the business cycle [Internet] Washington, DC: The Fund; 2008. [updated 2008 Apr; cited 2008 Jul 25]. Available from: http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2008/01/index.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canada's health care providers, 1997 to 2006: a reference guide. Ottawa: The Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vibert J. Canadian physiotherapy graduates in 2007. E-mail to: Adrienne Leggett (Department of Physical Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, ON) 2008. Aug 7, Vibert J. (Canadian Alliance of Physiotherapy Regulators, Toronto, ON)

- 29.Robson M, Kitchen SS. Exploring physiotherapy students' experiences of interprofessional collaboration in the clinical setting: a critical incident study. J Interprof Care. 2007;21:95–109. doi: 10.1080/13561820601076560. doi: 10.1080/13561820601076560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hilgenberg C, Schlickau J. Building transcultural knowledge through intercollegiate collaboration. J Transcult Nurs. 2002;13:241–7. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003014. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kulwicki AD, Miller J, Schim SM. Collaborative partnership for culture care: enhancing health services for the Arab community. J Transcult Nurs. 2000;11:31–9. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100106. doi: 10.1177/104365960001100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schön DA. Educating the reflective practitioner: towards a new design for teaching and learning in the professions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mori B, Batty HP, Brooks D. The feasibility of an electronic reflective practice exercise among physiotherapy students. Med Teach. 2008;30:e232–8. doi: 10.1080/01421590802258870. doi: 10.1080/01421590802258870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]