Abstract

In humans, β-hexosaminidase A (αβ) is required to hydrolyze GM2 ganglioside. A deficiency of either the α- or β-subunit leads to a severe neurological disease, Tay-Sachs or Sandhoff disease, respectively. In mammals β-hexosaminidase B (ββ) and S (αα) are other major and minor isozymes. The primary structures of the α- and β-subunits are 60% identical, but only the α-containing isozymes can efficiently hydrolyze β-linked GlcNAc-6-SO4 from natural or artificial substrates. Hexosaminidase has been grouped with glycosidases in family 20. A molecular model of the active site of the human hexosaminidase has been generated from the crystal structure of a family 20 bacterial chitobiase. We now use the chitobiase structure to identify residues close to the carbon-6 oxygen of NAG-A, the nonreducing β-GlcNAc residue of its bound substrate. The chitobiase side chains in the best interactive positions align with α-Asn423Arg424 and β-Asp453Leu454. The change in charge from positive in α to negative in β is consistent with the lower Km of hexosaminidase S, and the much higher Km and lower pH optimum of hexosaminidase B, toward sulfated versus unsulfated substrates. In vitro mutagenesis, CHO cell expression, and kinetic analyses of an αArg424Lys hexosaminidase S detected little change in Vmax but a 2-fold increase in Km for the sulfated substrate. Its Km for the nonsulfated substrate was unaffected. When αAsn423 was converted to Asp, again only the Km for the sulfated substrate was changed, increasing by 6-fold. Neutralization of the charge on αArg424 by substituting Gln produced a hexosaminidase S with a Km decrease of 3-fold and a Vmax increased by 6-fold for the unsulfated substrate, parameters nearly identical to those of hexosaminidase B at pH 4.2. As well, for the sulfated substrate at pH 4.2 its Km was increased 9-fold and its Vmax decreased 1.5-fold, values very similar to those of hexosaminidase B obtained at pH 3.0, where its βAsp453 becomes protonated.

There are two major β hexosaminidase (Hex)1 isozymes in normal human tissues, Hex A (αβ) and Hex B (ββ). A very small amount of a third unstable, acidic isozyme, Hex S (αα), can be detected in cells that are deficient in the β protein, i.e., from Sandhoff patients. However, this isozyme can be readily detected in αcDNA-transfected cells (1), and because of its low pI, it can be readily separated from the major Hex A and B isozymes by methods such as ion-exchange chromatography (2, 3). The primary structures of the α- and β-subunits are 60% identical. Thus they must also share very similar three-dimensional structures with conserved functional domains. Despite data showing that monomeric subunits are not active, the existence of the three Hex isozymes, representing all possible dimeric combinations of α- and/or β-subunits, indicates that each subunit must contain all of the residues necessary to form an active site. While all three Hex isozymes can cleave the terminal nonreducing β1–4-linked glycosidic bonds of either amino sugar (GlcNAc or GalNAc), e.g., from Asn-linked oligosaccharides or some neutral glycolipids, only Hex A and Hex S can cleave terminal nonreducing β1–4-linked GlcNAc-6-sulfate residues from keratan sulfate, and only Hex A can cleave the β1–4-linked GalNAc residue from GM2 ganglioside. Sensitive, fluorescent, artificial substrates have been developed that mimic the former two groups of natural substrates, 4-methylumbelliferyl 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranoside (MUG, total Hex) and 2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-D-glucopyranoside-6-sulfate (MUGS, Hex A and Hex S). Although MUGS is often referred to as α specific, the β active site can also slowly hydrolyze this substrate. The MUG/MUGS ratio for each isozyme is as follows: Hex B, 200–300/1; Hex A, 3–4/1; Hex S, 1–1.5/1 (4). In vivo, it is the GM2 activator:GM2 ganglioside complex that is the true Hex A-specific substrate. It follows that defects in any of the genes encoding the subunits of Hex A (HEXA encodes α, and HEXB encodes β) or the monomeric GM2 activator (GM2A) can result in the lysosomal accumulation of GM2 ganglioside, mainly in neuronal tissues where its synthesis is greatest, causing inheritable neurodegenerative diseases, collectively known as the GM2 gangliosidoses: Tay-Sachs, HEXA mutations; Sandhoff disease, HEXB mutations; AB-variant, GM2A mutations (reviewed in refs 5 and 6).

Hopes of identifying structure–function relationships in human Hex through analysis of mutations associated with GM2 gangliosidoses have not been realized because most naturally occurring mutations, even missense mutations, first affect protein transport out of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (reviewed in refs 6 and 7). Retention and enhanced degradation of mutant proteins by this ER quality control system have been recognized as the direct cause of other diseases (8). Thus, retention in the ER can be viewed as a strong indication that a change has occurred in a protein’s folding patterns due to a mutation (9–11).

Human Hex A and B are members of the family 20 glycosidase (12). Members of this family are believed to be evolutionarily and thus structurally related. Thus, molecular modeling of the human α-subunit of Hex and recently Hex from Streptomyces plicatus, Sp-Hex, has been tried on the basis of the only known crystal structure for a family 20 glycosidase, a bacterial chitobiase [structures have been determined with and without a bound chitobiose substrate molecule, NAG(A)-NAG(B)] (13). However, chitobiase has only 26% sequence identity to its human counterpart, which occurs only within their active site regions. Outside of this region there is little sequence similarity. Thus, the modeling data for the active sites of the human Hex subunits need to be validated experimentally. We (14, 15), and others (16, 17) have demonstrated experimentally that the molecular models for human and SP Hex are at least partially accurate. In this report we take further advantage of the molecular model to identify those residues that are in close proximity to the oxygen atom on carbon-6 of the bound NAG-A portion of the chitobiose substrate. The aligned residues in α were examined as candidates for its 6-sulfate binding site.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA Construction and Mutagenesis

To create the pREP4-α constructs encoding the mutations Arg424Lys, Arg424Gln, and Asn423Asp, site-directed mutagenesis was carried out. The previously reported pREP4-α construct (4) was used as a template for the three PCR reactions. For the Arg424Lys substitution, the primer GCCCCCTGGTACCTGAACAAGATATCCTATGG, containing the CTG → AAG substitution, was used. The Arg424Gln substitution was created using the primer GCCCCCTGGTACCTGAACCAAATATCCTATGG, containing the CTG → CAA substitution. Finally, the Asn423Asp substitution used the primer GCCCCCTGGTACCTGGACCGTATATCCGG, containing the AAC → GAC substitution. The reactions were performed in 100 μL. Each of the reaction mixtures contained 50 ng of plasmid DNA, 0.2 mM each of dNTPs, 0.5 μg of each primer, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 5 units of Ample Taq Gold (Rote). The cycling steps used were as follows: 1 cycle of denaturation at 94 °C for 10 min, 30 cycles each consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 20 s, annealing at 62 °C for 20 s, and extension at 72 °C for 10 s, in a Perkin-Elmer-Cetus thermal cycler. Each of the three PCR products was purified and digested with KpnI and subcloned into pREP4-α.

To create the βAspLeu455-AsnArg double mutation, a two-step PCR procedure was used. In the first PCR round, a 200 bp product was generated, using a forward primer having the sequence TCCATTGTCTGGCAGGAGGTT, and a reverse primer ATAACTAATCCGATTTAA, containing the substitutions necessary to produce the βAspLeu455-AsnArg mutation. The reactions were performed in 100 μL. Each reaction mixture contained 10 ng of plasmid DNA, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.01% gelatin, 0.2 mM each of dNTPs, 0.5 μg of each primer, and 0.5 unit of Vent polymerase (18). The cycling steps used were as follows: 1 cycle of heat denaturation at 94 °C for 5 min, 25 cycles each consisting of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s in a Perkin-Elmer-Cetus thermocycler. The product of the first PCR amplification was purified and utilized as a primer (<1 μg) along with an antisense primer spanning the BamHI restriction site of the pCDβ43 construct. PCR was conducted using the same conditions as mentioned above. The second fragment was subcloned directly into pCDβ43 (19) using the BamHI restriction sites. The mutation was confirmed by sequencing the 700 bp region, by using the T7 Sequencing Kit (Pharmacia).

Cell Culture and DNA Transfections

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were grown in α-MEM with 10% FCS and antibiotics at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Transfections were performed according to the Superfect reference manual from Qiagen. Briefly, CHO cells were seeded overnight in 100 mm tissue culture dishes and grown overnight until they were about 80% confluent. Four dishes were seeded, with one plate receiving the wild-type pREP4-α construct and the other three plates, the three mutant pREP4-α constructs. For each of the four constructs, 10 μg of DNA was mixed with 60 μL of Superfect in 300 μL of serum-free MEM. The mixtures were allowed to incubate for 10 min at room temperature to form the DNA–Superfect complexes. Three milliliters of α-MEM-containing serum was added to each of the four mixtures prior to being added dropwise to the culture dishes. The dishes were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h, after which time the cells were washed and refed with α-MEM containing 10% FCS for 48 h. Following this, the cells were refed α-MEM plus 10% FCS and 1 μL/mL hygromycin B every 2 days. After 1 month, the four plates containing mixed colonies were trypsinized, and the cells were passaged into larger dishes for further growth and analyses. Hygromycin B was present in all of the stable transfectants. Transfection of the mutant Hex B construct, produced from the original pCDβ43 clone (19), was done in a similar manner except an empty pREP4 vector was cotransfected along with the Hex B cDNA in order to provide hygromycin resistance. Two micrograms of pREP4 and 8 μg of the Hex B construct were used.

Separation of Secretory Hex S by Diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) Ion-Exchange Chromatography

Lysates collected from the four stably transfected cell lines or control CHO cells were dialyzed against 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 6, containing 0.12 M NaCl overnight. Each dialyzed lysate (6 mL) was applied to a 1 mL column of DEAE-Sepharose CL-6B (Pharmacia). The column was then washed with 30 mL of the phosphate buffer plus NaCl. The bound Hex S fraction was collected by eluting the column with 0.2 M NaCl. Three 1 mL fractions were collected and assayed for Hex activity. Fractions 2 and 3 were pooled for each of the four constructs. A similar amount of lysate from nontransfected cells was subjected to the same ion-exchange procedure, and the pool of protein eluted at 0.2 M NaCl served as a negative control.

Hex Activity Assay

Proteins contained in each set of pooled Hex S fractions and CHO cell lysate containing mutant human Hex B were quantitated using the Bio-Rad protein assay. Hex activity was measured using MUG and MUGS substrates as previously reported (4) using 1.6 mM MUG or MUGS substrate incubated at pH 4.2 in citrate phosphate buffer at 37 °C for 30 min or 1 h, respectively. The mutant Hex B protein was separated from endogenous CHO cell Hex by immunoprecipitation as previously described (20, 21). Wild-type Hex B was obtained either from a purified placental preparation (3) or from the lysate of Tay-Sachs fibroblasts.

pH Optimum

The pH optimum was determined using both MUG and MUGS substrates. The pH range varied between 3.0 and 6.0, increasing in increments of 0.5 pH unit for the various forms of Hex S with either substrate. With MUG the same procedure was used for Hex B, but with MUGS a pH range of 2.5–4.5 with increments of 0.25 pH unit was used. Hex B was checked and found to be stable at 37 °C for 1 h at pH 2.5–4 (data not shown). Data points were “smoothed” by fitting them to a third-order polynomial equation using KaleidaGraph 3.0, and the optimum pH was estimated (±0.2 pH). Velocity data for Hex B are given in fluorescence units (FU).

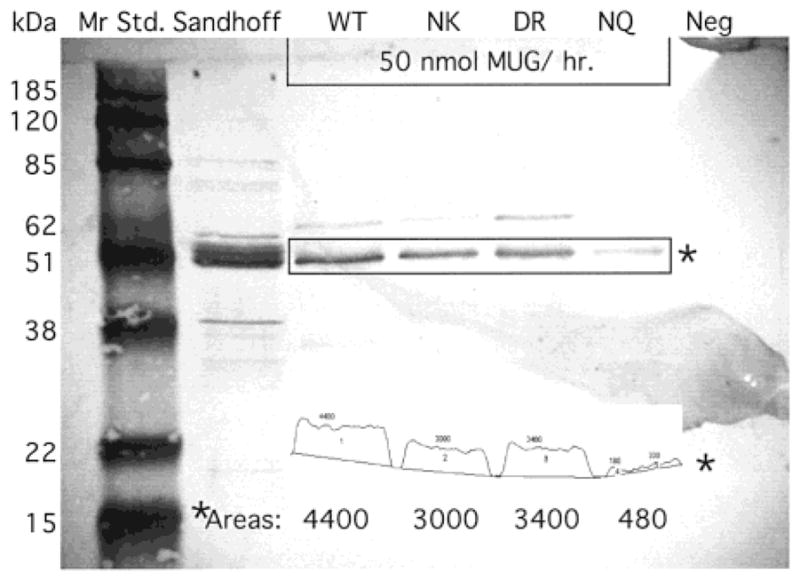

Western Blot Analysis and αCRM Quantitation

Pooled fractions of mutant and wild-type Hex S each able to hydrolyze 50 nmol of MUG/h (0.6–3.3 μg), 35 μg of lysate from a Sandhoff fibroblast cell line (positive control), and 3.3 μg from a nontransfected CHO cell lysate, fractionated by the same method used for the transfected cell lysates (negative control), were individually mixed with sample buffer containing 3% SDS and 25 mM DTT and incubated at 60 °C for 15 min. The proteins in each sample were separated by SDS–PAGE using the Laemmli gel system (10% gel) (22). The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose overnight (21). Nitrocellulose was blocked by exposure to 5% skim milk in BLOTTO (10 mM Tris base, 150 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 7.5) for 4 h with gentle shaking and then incubated with a 1:1500 dilution (1% skim milk in BLOTTO) of rabbit anti-human Hex A (αβ) IgG overnight. Nitrocellulose was washed four times with TST (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, with 0.5 M NaCl and 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated with a 1:2500 dilution (TST) of donkey anti-rabbit IgG conjugated with alkaline phosphatase for 1 h at room temperature. The nitrocellulose was then washed four times for 10 min with TST and, once again, quickly in TST without Tween 20 and blotted with filter paper to slightly dry the membrane. The nitrocellulose was then incubated in BCIP/NBT Membrane Phosphate Substrate (Kirkegaard and Perry Laboratories) for 2–10 min to develop a signal.

After a light signal was observed (all bands at less than saturation levels) on the nitrocellulose membrane (above), the reaction was stopped by washing with water, and the membrane was dried between two filter papers. The membrane was then converted to a digital image using a CCD video camera. The image was then analyzed using the Gel Plot Macro for NIH Image 1.60 software. The relative density of each of the mature αCRM bands from the four forms of Hex S expressed by the CHO cells was determined as Areas using this software. The amount of α protein present in each sample was calculated from each Area using the previously determined Units of MUG activity loaded and the known SA of the purified wild-type Hex S (4).

Kinetic Analysis

The Km values were determined for the ion-exchange column-enriched wild-type Hex S and the three mutant Hex S proteins at pH 4.2 by determining the initial velocity at concentrations of the MUGS substrate between 0.1 and 3.5 mM. When MUG was used as a substrate, its concentration was varied from 0.2 to 5 mM. The Km values for purified placental Hex B were determined at both pH 4.2 (MUG and MUGS) and pH 3.0 (MUGS). Kinetic constants were calculated using a computerized nonlinear least-squares curve-fitting program for the Macintosh, KaleidaGraph 3.0. Each kinetic experiment was repeated at least three times. Standard errors were calculated from the best fit curve generated by the computer program. Specific activity values [nmol of MU h−1 (μg of Hex)−1] were plotted versus millimolar MUGS for the kinetic examinations of purified Hex B, whereas Hex S values were experimentally determined as nmol of MU h−1 μg−1 because it was not fully purified from the transfected CHO cell lysates. The final calculations of SA at Vmax [nmol of MU h−1 (μg of Hex)−1] for each of the four mutant forms of Hex S were accomplished using the μg of αCRM/μg of total protein values determined through Western blotting and densitometry (see above).

RESULTS

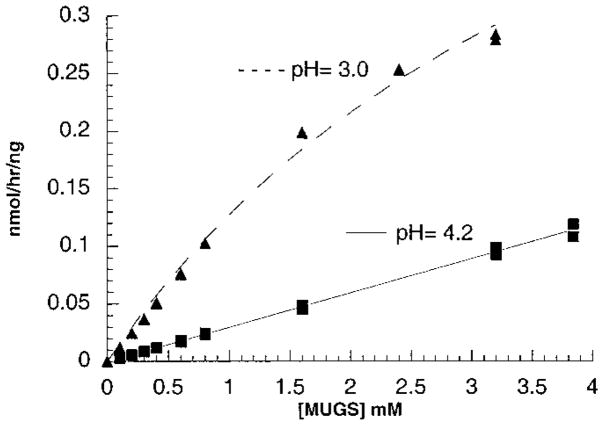

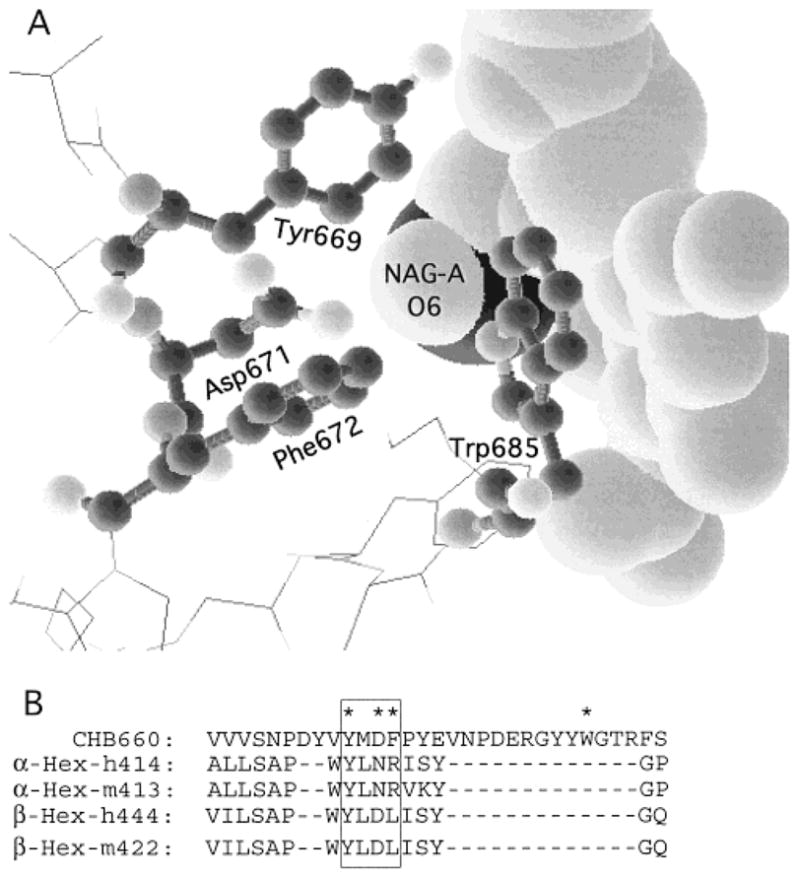

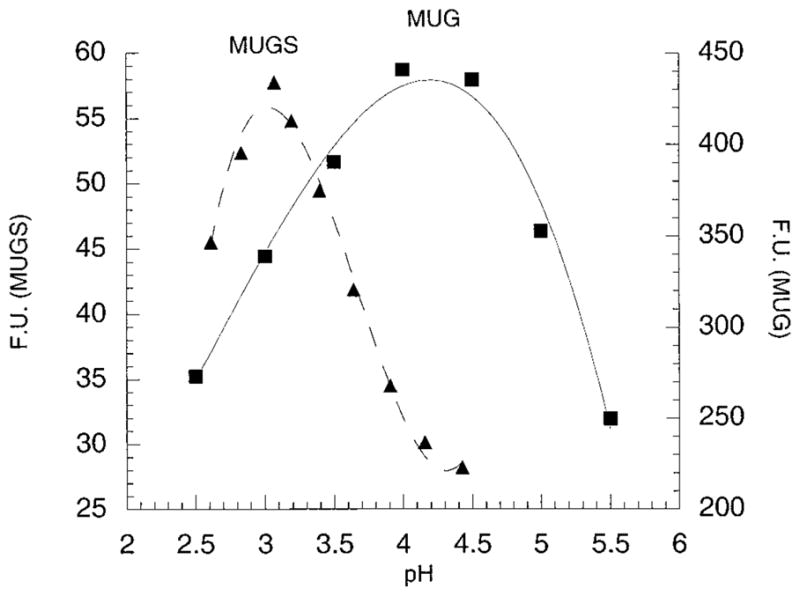

Using the program RasMol v2.6.1 and the file 1QBB-chito+dinag.pdb from the Protein Data Base web site containing the coordinates of the crystal structure of bacterial chitobiase with a bound substrate molecule, chitobiose [NAG(A)-NAG(B)], four residues that had atoms within 3.5 Å of the oxygen atom on carbon-6 of NAG-A were identified (Figure 1A). Of the four residues the side chains of c-Asp671 and c-Phe672 are in the best interactive positions. Based on the published molecular model of the active site of the human α-subunit (13), these two residues align with α-Asn423Arg424 which in turn align with β-Asp453Leu454 (23) (Figure 1B). The change in charge from negative in β to positive in α is consistent with this site being involved in 6-sulfate binding. In addition, the pH optimum of purified placental Hex B was found to be 4.2 for MUG and 3.0 for MUGS (Figure 2), as compared with a pH optimum for Hex S of 4.0 for both substrates (Table 1). The change in pH optimum for Hex B with the MUGS substrate was found to be accompanied by a lowering of its Km for the substrate from “incalculable”, because of substrate solubility limits at pH 4.2, to 4.6 mM at pH 3.0 (Figure 3, Table 1) (substrate inhibition was noted with MUGS >3.5 mM; data not shown). These data are consistent with the need to neutralize an Asp residue (pKa = 3.9) at the site in Hex B that interacts with the 6-sulfate group.

Figure 1.

(A) Output of the program RasMol v2.6.1 and the file “1QBB-chito+dinag.pdb” from the Protein Data Base web site. The file contains the coordinates of the crystal structure of bacterial chitobiase with a bound substrate molecule chitobiose [NAG(A)-NAG(B)]. The program allows one to identify residues within a set distance from another moiety. In the picture four residues, shown in “ball-and-stick” format, were identified as having atoms within 3.5 Å of the oxygen atom on carbon-6 of NAG-A, shown in the “space-filling” format (other surrounding residues are shown in the “wire” format). Of these four residues it is apparent that Asp671 and Phe673 have side chains in the best positions to interact with NAG-A’s O6 atom. (B) Alignment of the area identified in “A” on the basis of the molecular modeling of human Hex from chitobiase (13) with residues in human and mouse α- and β-subunits.

Figure 2.

pH optima profiles of purified placental Hex B using MUG or MUGS as a substrate. Florescent units were plotted versus pH.

Table 1.

Characterization of Substrate Specificity, Specific Activity, and pH Optima of Wild-Type and/or Mutant Forms of Hex

| forms of Hex | MUG/MUGSa | nmol of MUG h−1 (μg of total protein)−1 b | αCRM/units of MUGc | μg of Hex/μg of total proteind | nmol of MUG h−1 (μg of Hex)−1 d | MUG pH optimum ± 0.2 | MUGS pH optimum ± 0.2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pure Hex Se: 2(αNR424) | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 1000 ± 100 | 1.0 | 1000 ± 100 | 4.1 | 4.0 | |

| WTf Hex S: 2(αNR424) | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 69 ± 6 | 1.0 | 0.069 | 1000 | 4.0 | 3.9 |

| Hex S: 2(αNK424) | 1.9 ± 0.3 | 31 ± 2 | 0.68 | 0.021 | 1500 | 4.0 | 3.9 |

| Hex S: 2(αDR424) | 2.8 ± 0.7 | 15 ± 1 | 0.77 | 0.011 | 1400 | 4.2 | 4.1 |

| Hex S: 2(αNQ424) | 52 ± 15 | 78 ± 3 | 0.11 | 0.0086 | 9100 | 4.0 | 3.7 |

| pure Hex Bg: 2(βDL454), pH 4.2/MUGS, pH 3 | 210 ± 30 55 ± 20h |

10000 ± 1000d | N/Ai | 1.0 | 10000 ± 1000 | 4.2 | 3.0 |

| CHO negative controlj | 0.7 | 0.04 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | N/A | N/A |

The ratio of units of MUG to MUGS hydrolyzed by the indicated form of Hex at pH 4.2 with substrate concentrations of 1.6 mM.

Specific activity (SA) of the purified and partially purified forms of the Hex isozymes at pH 4.2 and 1.6 mM substrate.

Ratio of the level on αCRM as determined by densitometry scanning of a Western blot (Figure 4) versus units of MUG activity, normalized against the expression of the wild-type αcDNA construct.

Micrograms of pure Hex per microgram of total protein calculated by (the SA of each Hex form) × (αCRM/units of MUG)/(the SA of pure Hex S).

Data from ref 4.

Wild type.

Purified placental Hex B.

Determined at 4.2 for MUG and pH 3.0 for MUGS.

Not applicable.

The untransfected CHO cell lysate was fractionated by DEAE ion-exchange chromatography in a manner identical to that of the transfected cell lysate.

Figure 3.

Kinetic examination of purified placental Hex B using MUGS as a substrate at pH = 3.0 or 4.2. At pH = 3.0, substrate inhibition was noted with MUGS concentrations >3.5 mM (data not shown); thus assays were restricted to less than optimal substrate concentrations. The absolute specific activities (nanomoles of MU per hour per nanogram of Hex B) were plotted versus substrate concentration.

Hex S, WT, and forms mutated at the α-Asn423Arg424site were analyzed after partial purification by ion-exchange chromatography to remove endogenous CHO cell Hex A and B. Western blot analyses of the partially purified forms of Hex S, each containing 50 units of MUG activity, detected mature, i.e., lysosomal (1, 20, 24) α-chains in each sample, indicating that all forms were able to fold properly and exit the ER (4, 14, 20, 25) (Figure 4) (reviewed in refs 9, 26, and 27). The relative SA (MUG units/total protein) of each pool varied, ranging from 78 to 15 nmol h−1 μg−1. A relative SA of 0.04 nmol h−1 μg−1 was determined for the pool of proteins comprising the negative control (untransfected CHO cell lysate identically fractionated by ion-exchange chromatography) (Table 1). This extremely low level of Hex activity in the negative control reflects the normally very low levels of endogenous Hex S in all mammalian cells and allowed us to ignore its contribution to all the following kinetic analyses.

Figure 4.

Western blot of transfected CHO cells containing 50 units of MUG activity each: WT, wild-type Hex S; NK, Hex S containing a Arg424 → Lys substitution; DR, Hex S containing a Asn423 → Asp substitution; NQ, Hex S containing a Arg424 → Gln substitution. Sandhoff is a positive control lane containing lysate from a Sandhoff patient’s fibroblasts, and Neg is the negative control lane containing untransfected CHO cell lysate. The output from Gel Plot Macro of NIH Image 1.60 software is presented as an insert near the bottom of the membrane, and the calculated Areas are reproduced in a larger font size below the scans of each mature αCRM band. Note that the Image program divided the smallest NQ band into two sections. Only the sum of these sections (480) is shown in larger size font below.

The absolute SA of purified Hex S for 1.6 mM MUGS at pH 4.2 and 37 °C (standard assaying conditions) has been reported as 1000 nmol h−1 μg−1 (4), while that for purified Hex B is 10-fold higher (15). Since the amounts of protein analyzed by Western blotting from each pool of semipurified Hex S from transfected CHO cell lysate were adjusted to contain the same number of MUG units (50 nmol/h) densitometry scanning of the four samples (WT, NK, DR, and NQ, Figure 4) was used as a means of assessing any major changes in the SA of the mutant forms of Hex S (Figure 4, insert). While the SA of the NK (αArg424Lys), and DR (αAsn423Asp) mutants were slightly increased over the WT (1.5-fold), the SA of the NQ (αArg424Gln) was increased 9-fold over the WT, making its SA for MUG more comparable to Hex B than to Hex S (Table 1).

When each form of Hex S was assayed under standard conditions (1.6 mM substrate at pH 4.2) with MUGS and the MUG/MUGS ratios were calculated, other major differences were seen (Table 1). The largest change was again observed when the charge on Arg424 was neutralized by its conservative substitution with Gln (1.4/1, WT, versus 52/1, NQ) (Table 1). This ratio was within experimental error limits of the ratio for purified Hex B assayed at pH 4.2 with MUG and at pH 3.0 with MUGS (55/1) (Table 1).

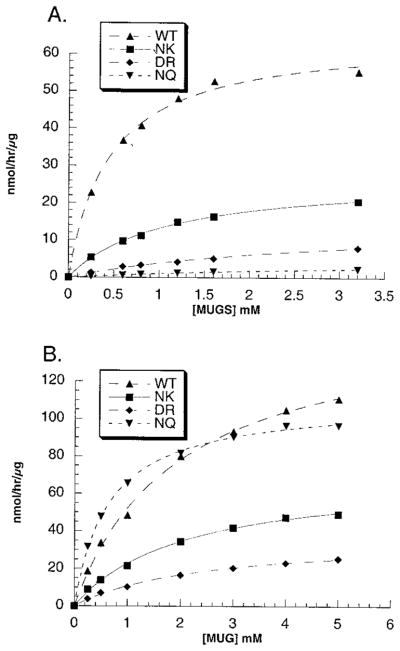

A more detailed kinetic examination confirmed that even a conservative αArg424Lys substitution increased the Km for the MUGS substrate by 2.4-fold (Figure 5A, Table 2), while having no effect on the Km for MUG (Figure 5B, Table 2). SA at Vmax calculations (Table 2, columns 4 and 7) based on levels of αCRM (Figure 4, Table 1 column 5) showed slight, 1.5-fold increases from the WT values for both substrates. The replacement of the neutral wild-type αAsn423 with the aligned negatively charged residue in β, Asp, produced a 6.4-fold larger increase in the Km for the MUGS substrate, again with no effect on the Km for MUG (Figure 4, Table 1). Again only a small change in the isozyme’s SA at Vmax was observed with both substrates, identical to the values obtained for the αArg424Lys substitution (Table 2, columns 4 and 7). Not surprisingly, the largest increase of 9-fold in the Km for MUGS was seen when Arg424 was neutralized by Gln (Figure 5A, Table 2). Interestingly, this Km was not significantly different from the Km for MUGS of Hex B when assayed at pH 3.0 where the Asp residue becomes neutral. Additionally, the αArg424Gln substitution, unlike all of the other changes, also affected the Km of Hex S for MUG, lowering it to ~0.7 mM, a value indistinguishable from the Km for MUG of purified placental Hex B at pH 4.2 (Figure 5, Table 2). Finally, the calculated SA at Vmax values for each substrate were changed so that they too were very nearly identical to those of purified Hex B, in the case of MUG when assayed at pH 4.2 and of MUGS when assayed at pH 3.0 (Table 2).

Figure 5.

Kinetic examinations of the mutant, i.e., WT α-Asn423-Arg424 → (a) Asn-Lys (NK), (b) Asp-Arg (DR), or (c) Asn-Gln-(NQ), and wild-type (WT) forms of Hex S using (A) MUGS or (B) MUG as a substrate. In these cases Hex S was enriched by ion-exchange chromatography but not purified. Velocity values are given in nanomoles of MU per hour per microgram of total protein.

Table 2.

Kinetic Analyses of Wild-Type and/or Mutant Forms of Hex S and B with MUG and MUGS Substrates

| forms of Hex | MUG Km (mM) | MUG Vmax [nmol h−1 (μg of total protein)−1] | MUG Vmax [nmol h−1 (μg of Hex)−1]a | MUGS Km (mM)b | MUGS Vmax [nmol h−1 (μg of total protein)−1]b | MUGS Vmax [nmol h−1 (μg of Hex)−1]a,b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pure Hex S: 2(αNR424) | 1.5 ± 0.2c | 2000 ± 50 | 2000 ± 50 | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 940 ± 40 | 940 ± 40 |

| WT Hex S: 2(αNR424) | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 155 ± 5 | 2200 | 0.45 ± 0.04 | 65 ± 2 | 940 |

| Hex S: 2(αNK424) | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 71 ± 2 | 3400 | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 28 ± 1 | 1350 |

| Hex S: 2(αDR424) | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 37 ± 1 | 3400 | 2.9 ± 0.5 | 15 ± 1 | 1350 |

| Hex S: 2(αNQ424) | 0.65 ± 0.05 | 110 ± 1 | 13000 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 5.3 ± 0.6 | 620 |

| pure Hex B: 2(βDL454) | 0.71 ± 0.1 | 14500 ± 500 | 14500 ± 500 | NDd | ND | ND |

| at pH 3.0e | N/Af | N/A | N/A | 4.6 ± 0.6 | 710 ± 60 | 710 ± 60 |

Vmax values were adjusted to reflect the amount of Hex protein used in each assay (based on data from column 5, Table 1).

Assay was carried out at pH 4.2 for Hex S and at pH 3.0 for Hex B.

± are standard errors calculated from the curve-fitting program and do not include the experimental errors from determining either the initial protein or substrate concentrations which are estimated at an additional ~±10%.

Not determined. Assays produced only a linear response up to the limit after which substrate inhibition was observed at pH 3 (>3.5 mM; data not shown).

Assays were done at pH 3.0.

Not applicable.

Since it appears that both αArg424 and a neutral adjoining residue, e.g., αAsn423, are needed for efficient MUGS hydrolysis by Hex S, we substituted both for their aligned residues in β, i.e., βAspLeu454AsnArg, to see if they were sufficient to confer such activity on Hex B. Unfortunately, the levels of expression were much lower using the pCDβ vector (28) cotransfected with the empty pREP4 vector for selection than was the case with the α constructs contained within the pREP4 vector (data not shown). Thus the human βAspLeu454AsnArg Hex B was enriched by immunoprecipitation from the endogenous CHO cell Hex B and A using a human anti-β antiserum (21). This resulted in MUG activity ~3-fold greater than that precipitated from an identical amount of lysate protein from nontransfected CHO cells (Table 3). Measurements of MUGS activity were found to be ~2-fold higher than the negative control level. Tay-Sachs disease fibroblast lysates, alone and spiked with nontransfected CHO cell lysate, were used as the positive control (Table 3). Western blot analysis of transfected cell lysates detected mature β chain, suggesting that the mutant Hex B that exited the ER was thus properly folded (14, 20) (data not shown). After subtraction of the negative control, the MUG/MUGS ratio for the mutant Hex B was 6. Thus replacement of the βAspLeu454 by AsnArg was sufficient to convey increased MUGS specificity to the mutant Hex B.

Table 3.

Substrate Specificity of the βAsp-Leu454Asn-Arg Hex B As Compared to Tay-Sachs Disease Fibroblast Lysate, Immunoprecipitated with Human-Specific Anti-Hex A IgG

| sample | MUG (nmol/h)a | MUGS (nmol/h)a | MUG/MUGS |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHO(−)b (480 μg) | (12)c | (6)c | N/A |

| TSDd (2.8 μg) + CHO(−) (480 μg) | 20 | <0 | N/A |

| TSDe (2.8 μg) | 27f | 0.5g | 54 |

| Asp-Leu454Asn-Arg Hex Bh | 26 | 4 | 6 |

Total nanomoles of MU activity per hour bound to Protein A–Sepharose anti-human Hex A IgG beads.

Negative control: untransfected CHO cell lysate (480 μg).

Negative control levels in parentheses were subtracted from the values listed below, except for TSD lysate alone where much smaller levels were encountered because of the lack of nonhuman, CHO cell Hex.

Positive control 1: Tay-Sachs disease fibroblast lysate (2.8 μg) added to the above negative control.

Positive control 2: Tay-Sachs disease fibroblast lysate (2.8 μg) alone.

Negative control level for this sample was ~0.5%.

Negative control level for this sample was ~10%.

Transfected CHO cell lysate, 480 μg, containing a mutant form of Hex B substituted with the two α-subunit residues associated with MUGS binding and hydrolysis (Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Because the degree of identity between human Hex and bacterial chitobiase, the only member of family 20 to be crystallized, is very low, even at the active site, the accuracy for the derived human Hex three-dimensional model (13) must be determined experimentally. We have demonstrated that the model accurately predicts the function of several active site residues in human Hex (14, 15). In this study we test the model again by using it to locate amino acid residues that are close to the C6–O atom of NAG(A) (Figure 1A). The aligned residues in the α-subunit of Hex A and Hex S were then examined as candidates for residues involved in binding the 6-sulfate group in MUGS, which give the α active site its unique substrate specificity as compared with β (Figure 1B). The simplest explanation for the difference in the ability of Hex A or S to efficiently bind and hydrolyze MUGS versus Hex B is that the α-subunit contains a positively charged residue in close proximity to the 6-sulfate of bound MUGS, while the β-subunit contains a negatively charged residue. This hypothesis was strengthened by the observed lower Km value for MUGS as compared to MUG, previously documented for Hex A and S (4) (suggesting that the sulfate is actively bound by the α subunit) and our present determination of the pH profile of Hex B for MUGS (Figure 2). This profile shows a 1.2 pH unit shift from Hex B’s optimum for MUG, pH = 4.2, when MUGS is the substrate. Such a shift is strongly suggestive of the need to neutralize an Asp residue (pKa = 3.9) which, if in close proximity, would otherwise actively repel the 6-sulfate group. Consistent with this hypothesis, when Km measurements for MUGS were made using purified Hex B, a much lower Km was determined at pH 3.0 than at pH 4.2 (Figure 3, Table 2).

The residues identified by the chitobiase model, whose side chains were the closest to C6–O of NAG-A, were Asp671 and Phe672, which align with βAsp453Leu454 and αAsn423Arg424 (Figure 1B). The presence of a negatively charged Asp in β as compared to a positively charged Arg in α is consistent with our above hypothesis. To test the role of αArg424 in binding the 6-sulfate group in MUGS, we constructed two cDNAs encoding conservative substitutions for this residue. The most conservative substitution was αArg424Lys. Despite the retention of a positive charge the Km for MUGS increased 2.5-fold (Figure 4A), with no change in the Km for MUG and only a small increase in its SA at Vmax for both substrates (Figure 4B, Table 2).

After calculation of the SA at Vmax for MUG and MUGS of the αAsn423Asp substituted form of Hex S, only slight increases were noted. Interestingly, while its Km for MUG was also unaffected, there was a 6-fold increase in its Km for MUGS (Table 2). These kinetic data were similar to those of the αArg424Lys form of Hex S, but with an additional 2.5-fold increase in its Km for the MUGS substrate.

When the charge on the αArg424 in Hex S was neutralized by substitution with Gln, major changes in the Km and SA at Vmax values for both substrates were observed (Table 2). In the case of MUG the Km becomes identical to that of Hex B assayed at pH 4.2, decreasing 3-fold from WT Hex S to 0.65 mM (Table 2). Similarly, the Km for MUGS determined for this form of Hex S was identical to that of Hex B assayed at pH 3.0 (where its Asp residue is neutral). Finally, the SA at Vmax values for both substrates were also very different from the other forms of Hex S, becoming nearly identical to purified Hex B. Thus, kinetically, Arg424Gln Hex S cannot be distinguished from WT Hex B at pH 3.0 using MUGS or from WT Hex B at pH 4.2 using MUG (Table 2).

To determine if the substitutions of Asn-Arg for βAsp453Leu454 were sufficient to promote MUGS hydrolysis by Hex B, we permanently transfected CHO cells by cotransfecting an empty pREP4 vector for selection with a mutated β-cDNA encoding the two substitutions contained in the pCD vector (28). Expression levels using the vector combination proved to be much lower than we obtained for Hex S directly cloned into the pREP4 vector (data not shown). As well, unlike Hex S, CHO cells contain large amounts of endogenous Hex A and B which forced us to use immunopurification of the mutant human Hex B followed by solid-state assays (21, 25) as a means of assessing any change in substrate specificity. As positive controls for this procedure we used Tay-Sachs fibroblast lysate, either alone or spiked with large amounts of untransfected CHO cell lysate (Table 3). Analyses of the immunoprecipitated mutant Hex B from 480 μg of transfected CHO cell lysate confirmed that it was able to hydrolyze MUGS with an MUG/MUGS ratio of ~6 (Table 3). This is still not as low as wild-type Hex S, but it is much lower than purified Hex B (Table 1), or the ratio calculated from the immunoprecipitated Tay-Sachs fibroblast lysate (2.8 μg) alone, ~50. When 2.8 μg of Tay-Sachs lysate was used to spike 480 μg of nontransfected CHO cell lysate and the mixture was immunoprecipitated, no MUGS activity above the CHO(−) background was detected (Table 2). Thus, it remains possible that other areas in the β-subunit may have some small additional involvement in MUGS hydrolysis. Clearly, analyses of more highly purified mutant forms of Hex B are needed to clarify this issue.

All of the above data (Tables 1 and 2) confirm our hypothesis that αArg424 directly binds the 6-sulfate group of MUGS in the α-subunits of Hex A and S. The observation that Lys cannot fully substitute for αArg424 is one of the strongest pieces of evidence for such a direct interaction. For example, the MUG kinetic data from the αArg424Lys Hex S demonstrate that in this case the Lys can substitute for the Arg in increasing Hex S’s Km and decreasing its Vmax for this substrate (Table 2). Thus the negative effects on MUG binding and hydrolysis are caused by a general positive charge at α424 rather than by a specific amino acid. Similarly, by extrapolation from the αAsn423Asp Hex S and αArg424Gln Hex S kinetic data, as well as the difference in WT Hex B’s MUGS kinetics at pH 4.2 versus 3.0, it appears that the general negative charge from βAsp453 of Hex B actively inhibits 6-sulfate binding while βLeu454 neither assists nor inhibits.

Footnotes

This work was supported by a Medical Research Council of Canada grant to D.M.

Abbreviations: Hex, β-hexosaminidase; GM2 or GM2 ganglioside, GalNAcβ(1–4)-[NANAα(2–3)]-Galβ(1–4)-Glc-ceramide; GM2 activator protein, activator; MU, 4-methylumbelliferone; MUG, 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-N-acetylglucosamine; MUGS, 4-methylumbelliferyl-β-N-acetylglucosamine-6-sulfate; NAG-A, the β-linked GlcNAc residue at the nonreducing end of chitobiose; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; WT, wild type; SA, specific activity.

References

- 1.Brown CA, Mahuran DJ. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:497–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Dowd BF, Klavins MH, Willard HF, Gravel R, Lowden JA, Mahuran DJ. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:12680–12685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahuran DJ, Lowden JA. Can J Biochem. 1980;58:287–294. doi: 10.1139/o80-038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hou Y, Tse R, Mahuran DJ. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3963–3969. doi: 10.1021/bi9524575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gravel RA, Clarke JTR, Kaback MM, Mahuran D, Sandhoff K, Suzuki K. In: The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1995. pp. 2839–2879. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mahuran DJ. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1455:105–138. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(99)00074-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahuran DJ. In: Protein Dysfunction in Human Genetic Disease. Swallow D, Edwards Y, editors. Bios Scientific; Oxford U.K: 1997. pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng SH, Richard JG, Marshall J, Paul S, Souza DW, White GA, O’Riordan CR, Smith AE. Cell. 1990;63:827–834. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edgington SM. Bio/Technology. 1992;10:1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/nbt1192-1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gottesman S, Wickner S, Maurizi MR. Genes Dev. 1997;11:815–823. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.7.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ashkenas J, Byers PH. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:267–272. doi: 10.1086/514865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Henrissat B. Biochem J. 1991;280:309–316. doi: 10.1042/bj2800309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tews I, Perrakis A, Oppenheim A, Dauter Z, Wilson KS, Vorgias CE. Nat Struct Biol. 1996;3:638–648. doi: 10.1038/nsb0796-638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hou Y, Vocadlo D, Leung A, Withers S, Mahuran D. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2201–2209. doi: 10.1021/bi002018s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou Y, Vocadlo D, Withers S, Mahuran D. Biochemistry. 2000;39:6219–6227. doi: 10.1021/bi992464j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandes MJG, Yew S, Leclerc D, Henrissat B, Vorgias CE, Gravel RA, Hechtman P, Kaplan F. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:814–820. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mark BL, Wasney GA, Salo TJS, Khan AR, Cao ZM, Robbins PW, James MNG, Triggs-Raine BL. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19618–19624. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tse R, Vavougios G, Hou Y, Mahuran DJ. Biochemistry. 1996;35:7599–7607. doi: 10.1021/bi960246+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Dowd B, Quan F, Willard H, Lamhonwah AM, Korneluk R, Lowden JA, Gravel RA, Mahuran D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1184–1188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hou Y, McInnes B, Hinek A, Karpati G, Mahuran D. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21386–21392. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown CA, Neote K, Leung A, Gravel RA, Mahuran DJ. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21705–21710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli UK. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korneluk RG, Mahuran DJ, Neote K, Klavins MH, O’Dowd BF, Tropak M, Willard HF, Anderson MJ, Lowden JA, Gravel RA. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:8407–8413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hasilik A, Neufeld EF. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:4937–4945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hou Y, Vavougios G, Hinek A, Wu KK, Hechtman P, Kaplan F, Mahuran DJ. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:52–58. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurtley SM, Helenius A. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1989;5:277–307. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.001425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pelham RB. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1989;5:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okayama H, Berg P. Mol Cell Biol. 1982;2:161–170. doi: 10.1128/mcb.2.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]