Abstract

A Mexican woman, aged 71 years, with life-long exposure to soot from a wood cook stove in a closed environment, who was treated for tuberculosis 4-years prior, presented with prominent mediastinal lymphadenopathy with anthracosis. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is a common presentation of diverse granulomatous, malignant and infectious conditions like tuberculosis. Anthracotic pigment is found in different conditions such as tuberculosis or domestically acquired particulate lung disease. Accurate assessment of chronology and causative factors presents a challenge. Recognizing that pneumoconiosis can mimic or coexist with other granulomatous, infectious and malignant conditions presenting as mediastinal lymphadenopathy is important. Misdiagnosis may result in under- or over-treatment of potentially curable conditions such as tuberculosis, under-treatment of a lethal condition such as melanoma, or exposure of patients to inappropriate administration of costly therapy with potential untoward effects.

Keywords: Anthracosis, Domestically acquired particulate lung disease, Hut lung, Mediastinal lymphadenopathy, Pneumoconiosis, Pulmonary tuberculosis

A non-smoking Mexican woman, aged 67 years, presented with cough and sputum production to a community health clinic. A chest radiograph showed left upper lobe nodular opacities. Mycobacteriology smear was positive for 1 to 9 acid fast bacilli (AFB) per 10 oil immersion fields, with final isolation of mycobacterium tuberculosis complex made by analysis of the mycolic acid peak profile produced by high performance liquid chromography. The isolate was pansensitive to the antibiotics tested (isoniazid 0.2 μg/ml, isoiazid 1 μg/ml, rifampin 1 μg/ml, ethambutol 5 μg/ml, pyrazinamide 100 μg/ml). She was immediately treated under directly-observed therapy with a regimen consisting of four oral anti-tuberculosis medications: isoniazid 300 mg daily for 6 months, rifampin 600 mg daily for 6 months, pyrazinamide 300 mg daily for 2 months, and ethambutol 600 mg daily for 2 months. Six weeks after initiation of therapy, the three consecutive-day sputum examination was positive for 1 to 9 AFB per 100 oil immersion fields with negative cultures. Three consecutive-day sputum smears and cultures obtained subsequently were negative.

Four years after treatment for pulmonary tuberculosis, the patient presented with a two-month history of productive cough (grayish-black sputum) and a five-pound weight loss. She had no associated hemoptysis, night sweats, anorexia or fever. A chest radiograph revealed fullness in the left paratracheal area without parenchymal scarring. A follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 5.9 cm x 4.5 cm apical lung mass associated with multiple hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes (figure 1▶). Hypermetabolic foci were revealed by F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (FDG-PET) scan; a maximum standard uptake value (SUV) of 7.89 was observed in the apical lung lesion, and a maximum SUV of 7.9 was observed in the most intense subcarinal mediastinal adenopathy (figure 2▶). She underwent bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsies and brushings that were negative for malignancy and AFB, but had abundant anthracotic pigment suspicious of pneumoconiosis (figure 3A▶).

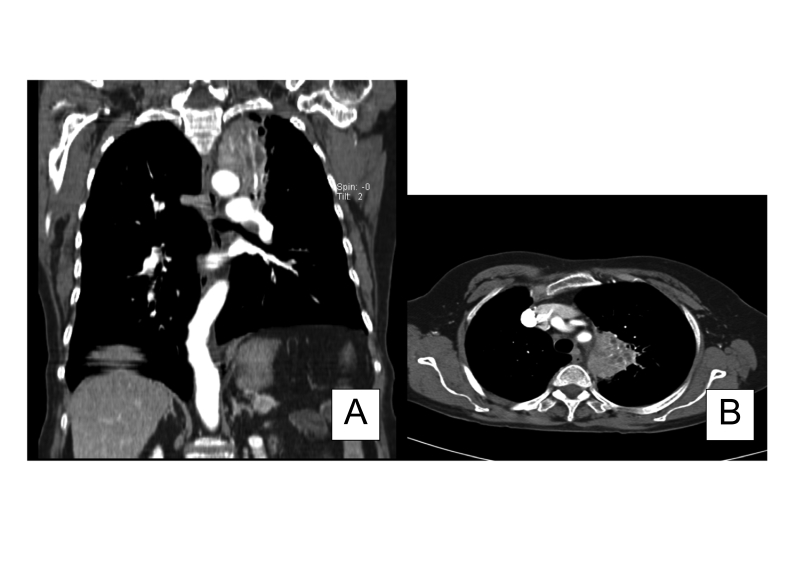

Figure 1.

Computed tomography showing (A) apical lung lesion with mediastinal adenopathy, frontal image, and (B) apical lung lesion with mediastinal adenopathy.

Figure 2.

F-18-FDG-PET/CT showing (A) increased uptake in the left upper lobe (maximum SUV=7.89) abutting the aortic arch, and extending superiorly to near the apex and inferiorly into the left hilum, with bilateral hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy (maximum SUV=7.96), and (B) bilateral hilar and mediastinal adenopathy (maximum SUV=7.96).

Figure 3.

Histology of lymph nodes sampled. (A) Transbronchial needle biopsies of subcarina demonstrating abundant anthracotic pigment (Papanicolaou stain, original magnification X200). (B) Cell block of the subcarinal lymph node FNA by EUS showing voluminous anthracotic pigment (H&E stain, original magnification X200). (C) Numerous epithelioid histiocytes with abundant anthracotic pigment in the celiac node FNA by EUS (Papanicolaou stain, original magnification X200).

She subsequently underwent an endoscopic ultrasound of the mediastinal lymph node with fine needle aspiration. A 3.5 cm x 1.1 cm hypoechoic irregular subcarinal lymph node and a 0.8 cm x 0.9 cm hypoechoic round celiac lymph node were identified. Fine needle aspirations of both lymph nodes (performed with different 25 gauge needles) were negative for AFB, fungi including Pneumocystis jiroveci, and malignancy. There were, however, multiple epitheloid histiocytes with abundant anthracotic pigments seen in both the subcarinal and celiac lymph nodes, suggesting pneumoconiosis (figures 3B and 3C▶). Spirometry was performed with a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 2.21 (102% of predicted). Forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of 1.38 (85% of predicted), FEV1/FVC ratio of 0.62, and forced midexpiratory flow (FEF25–75%) of 0.77 (52% of predicted). There was no significant change post bronchodilator indicating mild airway obstruction with no significant change post bronchodilator.

Further review of the patient’s history revealed no exposure to a coal mine, but a life-long exposure to soot from a wood cook-stove in a closed environment with minimal ventilation. She was diagnosed with anthracotic pneumonoconiosis presenting as a mediastinal mass and was referred to pulmonary medicine. She declined the referral since she was asymptomatic and has been following up with her primary care provider with no significant symptoms 12 months after her initial presentation to us.

Discussion

Anthracosis is a form of pneumoconiosis seen in coal workers, although other environmental factors such as cigarette smoke, air pollution and biomass fuels used extensively for cooking and home heating are also known to cause anthracosis.1–6 The terms “hut lung” or “domestically acquired particulate lung disease” have been used to describe the condition.7 A diagnostic feature in anthracosis is the black-colored deposits along the airway or lymph nodes. Problems caused by chronic exposure to biomass smoke and other particulates, such as dust or silicates from food grinding, are becoming more relevant in the western world due to immigration.7,8 Individuals may develop both physical and radiologic abnormalities of the lung presenting as chronic obstructive or fibrotic lung disease due to chronic exposure to smoke and particulates. Recent estimates attribute 1.5 to 2 million deaths per year worldwide to indoor air pollution, most of them (1 million) occurring in children younger than 5 years due to acute respiratory infections, but also in women due to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer.3

Anthracosis rarely presents as a mediastinal mass, mediastinal lymphadenopathy or axillary lymphadenopathy9–15 Our patient presented with mediastinal and celiac node adenopathy mimicking a neoplasm. Mediastinal lymphadenopathy is a common presentation of diverse granulomatous, malignant and infectious conditions such as tuberculosis. Our patient had a recent history of tuberculosis and a life-long history of exposure to wood-stove soot. An important question is, which came first? Tuberculosis can remain dormant in the body for decades. Dust deposition and scar formation are common findings in old lymphadenitis due to tuberculosis; therefore, one can argue that the inflammation induced by tuberculosis in the mediastinal lymph nodes may be the inciting stimulus for the final mass in this patient. However, the converse may be the case; environmental exposure to wood soot may be an immunosuppressive event in which the host’s cellular immunity action is diverted to engulfing anthracosis leading to impairment of respiratory defenses against mycobacteria.1,2

Based on this and multiple other case reports in the literature of diagnostic dilemmas,7,9,10,12,16 we emphasize the importance of recognizing that pneumoconiosis can mimic or coexist with other granulomatous, infectious and malignant conditions presenting as mediastinal lymphadenopathy. The discriminatory diagnosis is critical, since misdiagnosis can result in under- or over-treatment of potentially curable conditions such as tuberculosis, under-treatment of a lethal condition such as melanoma, or inappropriate administration of costly therapy in uncomplicated cases exposing patients to untoward effects of such therapies, including death.16

Evaluation of mediastinal mass can be a challenging diagnostic dilemma. Transesophageal endosonography with fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) and FDG-PET have become standard diagnostic procedures in such cases in thoracic medicine. EUS-FNA and FDG-PET are complementary diagnostic procedures combining the high sensitivity of FDG-PET and the high specificity of EUS-FNA to accurately diagnose malignancy in enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes identified by CT scan. The combination of the two procedures in selected cases with pulmonary cancer or extra-thoracic tumors avoided more invasive diagnostic and surgical procedures.17 PET has a sensitivity greater than 90%, but sensitivity of only about 80% in diagnosing pulmonary pathology.18,19 EUS has sensitivity of 60% to 90% and specificity of 70% to 100%.20 Combining EUS-guided FNA and PET in one study increased the overall specificity and positive predictive value to 100%, with an overall accuracy of 97%.21 The differential diagnosis of conditions that can cause mediastinal adenopathies include infectious etiologies such as tuberculosis, coccidioidomycosis, and histoplasmosis; granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis; malignancies such as lung cancer, Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and thymoma; and particulate lung diseases such as silicosis, anthracosis and berylliosis. These benign and malignant causes of mediastinal mass can be associated with PET positivity, mostly due to the increased cellular activity associated with malignancy, inflammation and infection. However, since our patient did not have malignancy or active inflammatory disease, it is difficult to understand the cause of increased FDG uptake on PET. Further research into the mechanism of false positive PET is needed.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marshfield Clinic Research Foundation’s Office of Scientific Writing and Publication for editorial assistance in the preparation of this article.

References

- 1.Zelikoff JT, Chen LC, Cohen MD, Schlesinger RB. The toxicology of inhaled woodsmoke. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev 2002;5:269–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torres-Duque C, Maldonado D, Pérez-Padilla R, Ezzati M, Viegi G; Forum of International Respiratory Studies (FIRS) Task Force on Health Effects of Biomass Exposure. Biomass fuels and respiratory diseases: a review of the evidence. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:577–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ezzati M, Kammen DM. The health impacts of exposure to indoor air pollution from solid fuels in developing countries: knowledge, gaps, and data needs. Environ Health Perspect 2002;110:1057–1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naccache JM, Monnet I, Guillon F, Valeyre D. Occupational anthracofibrosis. Chest 2009;135:1694–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran-Mendoza O, Pérez-Padilla JR, Salazar-Flores M, Vazquez-Alfaro F. Wood smoke-associated lung disease: a clinical, functional, radiological and pathological description. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2008;12:1092–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirsadraee M, Saeedi P. Anthrasocis of Lung: Evaluation of potential underlying causes. Bronchol 2005;12:84–87. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gold JA, Jagirdar J, Hay JG, Addrizzo-Harris DJ, Naidich DP, Rom WN. Hut lung. A domestically acquired particulate lung disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 2000;79:310–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albalak R, Frisancho AR, Keeler GJ. Domestic biomass fuel combustion and chronic bronchitis in two rural Bolivian villages. Thorax 1999;54:1004–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murata T, Imai T, Hoshino K, Kato M, Tanigawa K, Higuchi T, Kozuka Y, Inoue R, Watanabe M, Shiraishi T, Takubo K. Esophageal anthracosis: lesion mimicking malignant melanoma. Pathol Int 2002;52:488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varghese LR, Stanley MW, Wakely PE Jr, Lucido ML, Mallery S, Bardales RH. A case report of anthracosilicotic spindle-cell pseudotumor of mediastinal lymph node: cytologic diagnosis by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Diagn Cytopathol 2005;33:268–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murty DA, Das DK. Pulmonary tuberculosis with anthracosis: an unusual diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology. Acta Cytol 1993;37:639–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bilici A, Erdem T, Boysan SN, Acbay O, Oz B, Besirli K, Gundogdu S. A case of anthracosis presenting with mediastinal lymph nodes mimicking tuberculous lymphadenitis or malignancy. Eur J Intern Med 2003; 14:444–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Long R, Wong E, Barrie J. Bronchial anthracofibrosis and tuberculosis: CT features before and after treatment. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;184:S33–S36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cserni G. Misidentification of an axillary sentinel lymph node due to anthracosis. Eur J Surg Oncol 1998;24:168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klaaver M, Kars AH, Maat AP, den Bakker MA. Pseudomediastinal fibrosis caused by massive lymphadenopathy in domestically acquired particulate lung disease. Ann Diagn Pathol 2008;12:118–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bircan HA, Bircan S, Oztürk O, Ozyurt S, Sahin U, Akkaya A. Mediastinal tuberculous lymphadenitis with anthracosis as a cause of vocal cord paralysis. Tuberk Toraks 2007; 55:409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bataille L, Lonneux M, Weynand B, Schoonbroodt D, Collard P, Deprez PH. EUS-FNA and FDG-PET are complementary procedures in the diagnosis of enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes. Acta Gastroenterol Belg 2008;71:219–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer BM, Mortensen J, Højgaard L. Positron emission tomography in the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer: a systematic, quantitative review. Lancet Oncol 2001; 2:659–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vansteenkiste JF, Stroobants SG. Positron emission tomography in the management of non-small cell lung cancer. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2004;18:269–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puri R, Vilmann P. Transesophageal endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy of lesions in the mediastinum: a minimal invasive method for primary diagnosis of unknown mediastinal lesions and staging of lung cancer. J Assoc Physicians India 2009;57:467–471. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalade AV, Eddie Lau WF, Conron M, Wright GM, Desmond PV, Hicks RJ, Chen R. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration when combined with positron emission tomography improves specificity and overall diagnostic accuracy in unexplained mediastinal lymphadenopathy and staging of non-small-cell lung cancer. Intern Med J 2008;38:837–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]