Abstract

Environmental cues previously associated with reinforcing drugs can play a key role in relapse to drug seeking behaviors in humans. The mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) system plays a critical role in cocaine-induced neurobiological changes. DA D1 and D3 receptors modulate locomotor-stimulant and positive reinforcing effects of cocaine, and cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Moreover, activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) induced by acute cocaine administration is regulated by both D1 and D3 receptors. How D1 and D3 receptors modulate the acquisition and extinction of cue-elicited cocaine seeking behavior and associated changes in the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway in different brain regions, however, remains unclear. In the present study, we found that D1 receptor mutant mice failed to acquire conditioned place preference (CPP) while D3 receptor mutant mice show delayed CPP extinction compared to wild-type mice. Moreover, ERK, but not the c-Jun N-terminal kinase and p38, is activated in wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice but not in D1 receptor mutant mice following CPP acquisition. D3 receptor mutant mice also exhibit sustained ERK activation compared to wild-type mice following extinction training. Our results suggest that D1 and D3 receptors differentially contribute to learned association between cues and the rewarding properties of cocaine by regulating, at least in part, ERK activation in specific areas of the brain.

Keywords: dopamine, D1 and D3 receptors, MAPK, cocaine, cue, drug seeking

Introduction

A key feature of drug addiction is that individuals experience intense drug craving after long abstention and are susceptible to relapse to drug seeking by exposure to drug-associated cues (Dackis and O'Brien 2005). Memories of this learned association between cues and the rewarding properties of abused drugs are difficult to extinguish and contribute significantly to the high propensity to relapse (Koob et al. 2004; Kalivas and Volkow 2005; Hyman et al. 2006; Kauer and Malenka 2007; Kalivas and O'Brien 2008). The mesocorticolimbic dopamine (DA) system projecting from the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), amygdala (AMG), prefrontal cortex (PFC) and other structures mediate the effects of drugs of abuse (Koob and Volkow 2009). Addictive drugs increase levels of synaptic DA in the brain (Ritz et al. 1987; Di Chiara and Imperato 1988). The NAc, basolateral AMG (BLA) and PFC are part of the circuitry underlying cue-elicited cocaine seeking, including acquisition and extinction (Weiss 2005; Feltenstein and See 2008; Kalivas and O'Brien 2008; Koob and Volkow 2009). The BLA mediates learning conditioned associations between the rewarding effects of cocaine and cues. The PFC contributes to decision-making and execution of goal-directed actions. The NAc modulates motivation for cocaine seeking by integrating information from the BLA and PFC and relaying it to motor output structures, and it mediates reinforcement.

DA receptors are divided into two subfamilies (Missale et al. 1998). The D1-like subfamily includes D1 and D5 receptors and activation of these receptors leads to increased intracellular levels of cAMP. The D2-like subfamily includes D2, D3 and D4 receptors and activation of these receptors is negatively linked to the cAMP production. D1 receptors are mainly expressed in the NAc, caudate putamen, hippocampus, AMG and PFC whereas D3 receptors are primarily expressed in the NAc and to a lesser extent, AMG and PFC (Missale et al. 1998). A large percentage of D3 receptor-bearing neurons co-express D1 receptors in the NAc (Surmeier et al. 1996; Schwartz et al. 1998; Ridray et al. 1998). We and others have shown that D1 and D3 receptors mediate locomotor-stimulant and positive reinforcing effects of cocaine, as well as cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking (Xu et al. 1994a; 1994b; 1997; Pilla et al. 1999; Xu et al. 2000; Carta et al. 2000; Di Ciano and Everitt 2004; Heidbreder et al. 2005; Berglind et al. 2006; Caine et al. 2007; Chen et al. 2007; Di Ciano 2008; Liu et al. 2009).

The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family is a major modulator of cell function (Adams and Sweatt 2002). There are three major subtypes of MAPK including the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the p38 kinase. ERK plays key roles in neuronal plasticity while JNK and p38 regulate neuronal cell death (Thomas and Huganir 2004). Drugs of abuse such as cocaine and related cues can activate ERK in the brain DA system in the NAc, AMG, and PFC (Valjent et al. 2000; 2005; Miller and Marshall 2005a; Lu et al. 2005; 2006). Activated ERK enters the cell nucleus to modulate its downstream targets, including cAMP response element-binding protein and c-Fos, to regulate gene expression and ultimately behavioral effects of drug of abuse (Valjent et al., 2000; Choe and McGinty 2001; Wang et al. 2004; Zhang et al. 2004; Mattson et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2006; Lu et al. 2006).

Previous work showed that ERK activation is regulated by DA D1 and D3 receptors following cocaine administration (Zhang et al. 2004; Bertran-Gonzalez et al. 2008). Inhibiting the ERK signaling pathway reduces cocaine-induced behavioral responses (Pierce et al. 1999; Valjent et al. 2000; 2006; Ferguson et al. 2006). While these findings suggest the importance of the ERK signaling pathway in cocaine-induced changes in synaptic plasticity and behavior, how D1 and D3 receptors modulate the acquisition and extinction of cue-elicited cocaine seeking and associated changes in MAPK signaling in different brain regions remains unclear. In the present study, we used D1 and D3 receptor mutant mice and the conditioned place preference (CPP) behavioral paradigm (Bardo and Bevins 2000) to investigate this issue. Our data suggest that DA D1 and D3 receptors differentially contribute to aspects of cue-elicited cocaine seeking by regulating, at least partially, ERK activation in specific areas of the brain.

Materials and methods

Mice

DA D1 and D3 receptor mutant mice used in this study were generated previously (Xu et al. 1994a; 1997). Homozygous mutant mice and wild-type littermates were produced by crossing heterozygous parents. The genotype of the mutant and wild-type mice was identified by Southern blotting using gene-specific probes (Xu et al. 1994a; 1997). The genetic background of all mice was initially 50% each of 129SvJ and C57BL/6J, and was bred with C57BL/6J mice for 3 generations. D1 and D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice were group housed and were on a 12 hour light/dark cycle with food and water available ad libitum. Similar numbers of male and female mice, 10 to 16 weeks old (mean 12.8 weeks), were used in the current study. The temperature and humidity of the room were controlled. Animal use was strictly according to the NIH guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

Drugs and antibodies

Cocaine hydrochloride was purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and was dissolved in sterile saline. All injections were administered intraperitoneally (i.p.) in a volume of 10 ml/kg body weight. Cocaine doses used in the current study were 2.5, 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg. Primary antibodies against phospho-ERK, phospho-JNK, phospho-p38, ERK, JNK and p38 were from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Primary antibodies for actin and HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-goat second antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Technology (Santa Cruz, CA).

CPP

Eight three-chamber place preference apparatuses (MedAssociates, E. Fairfield, VT) were used in the current study (Zhang et al. 2006). The apparatus consisted of two larger compartments (16.8×12.7×12.7 cm), and a smaller compartment (7.2×12.7×12.7 cm) which separated the larger compartments. The two larger compartments had different visual and tactile cues. One compartment was black with a stainless steel grid rod floor. The other compartment was white with a stainless steel mesh floor. The smaller compartment was gray with a smooth PVC floor. The apparatus had a clear Plexiglas top with a light on it.

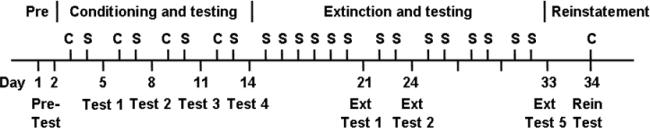

We used a CPP procedure similar to that described before (Zhang et al. 2006) with modifications (Fig. 1). During the preconditioning phase (day 1–2, pre-test), mice were placed in the smaller compartment and allowed to explore the 3 compartments freely for 20 minutes daily. The time spent in each compartment was recorded. Mice spending over 500 seconds in the smaller compartment or over 800 seconds on either large compartment (21 out of 241) were excluded. The next 12 days (day 3–14) were the conditioning (one session per day) and testing phase. The drug-paired group received an i.p. cocaine injection and was confined in the white compartment for 30 minutes on day 3. On day 4, this mouse group received an i.p. saline injection and was confined in the black compartment for 30 minutes. As a control, the saline group received i.p. saline injections in both compartments. On day 5 (test 1), mice were allowed to freely explore the 3 compartments for 20 minutes without injections, and the time spent in each compartment was recorded. Each mouse received 4 each of conditioning sessions and 4 tests. Following the conditioning and testing phase was the extinction phase. During extinction training, all animals were administrated saline i.p. once daily and were confined to the white (day 15) and then black (day 16) compartments for 30 minutes on alternative days. After 6 days of extinction training, mice were tested on day 21 (Ext-test 1). Mice were allowed to explore all compartments for 20 minutes without injections and the time spent on each side was recorded. Mice were then tested after every 2 days of extinction training until the extinction actually occurred (defined as mice no longer showing preference to the drug-paired side in two continuous tests). On the reinstatement test day (day 34), 24 hours after the last extinction test, mice received an i.p. cocaine (20 mg/kg) injection immediately before being placed in CPP boxes. Time spent on each side was recorded for 20 minutes.

Fig. 1.

The CPP behavioral paradigm and testing schedule. Preconditioning phase (Pre or Pre-test: day 1–2): mice were allowed to explore the CPP boxes for 20 minutes to determine the initial preference. Conditioning and testing phase (day 3–14): mice received once daily i.p. cocaine (C) or saline (S) injections alternatively and were confined in the white and black compartments respectively for 30 minutes. After every 2 days of training, mice were tested for place preference. Extinction and testing phase (day 15–33): mice received i.p. saline injections on both sides of the boxes and were confined for 30 minutes. The first extinction (Ext) test was given after 6 days of extinction training on day 21 and it was for 20 minutes. Then mice were tested after every 2 days of extinction training until CPP was extinguished. Reinstatement phase (Rein: day 34): mice received an i.p. cocaine injection before testing for CPP for 20 minutes.

As a control for studying extinction-related MAPK signaling, a group each of D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice was treated with cocaine or saline in the behavioral room exactly as all cocaine CPP groups except these mice did not go through CPP acquisition and extinction training (No-CPP). All behavioral testing was performed during the light phase of the light/dark cycle (8 am–8 pm).

Protein extracts

Different groups of mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation immediately after CPP expression (day 14) or extinction tests (day 21). The No-CPP groups were sacrificed at the same time (day 21) when the other groups of mice went through the first extinction test. Brains were quickly removed, frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C. Brains were sliced into 1 mm sections using the brain matrix. NAc, AMG and PFC were dissected using a mouse brain atlas (Paxinos and Franklin, 1997). Tissues were homogenized in 300 μl ice-cold extraction buffer. Homogenates were incubated on ice for 20 minutes and were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 20 minutes at 4°C (Zhang et al. 2006). Supernatants were collected and protein concentrations were determined using a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Western blotting

Changes in protein levels were analyzed by using Western blotting as before (Zhang et al. 2006). Equivalent amounts of protein (10–20 μg) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes after electrophoresis. The membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 1 hour at room temperature. Membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C with different primary antibodies. After 3 washes with a 0.1% Tween 20 Tris-buffered saline (pH7.6), membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-goat secondary antibodies. Signals were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. Primary antibodies against phospho-ERK and phospho-JNK were used at 1:2000 dilutions, and the anti-phospho-38 antibody was used at 1:1000 dilutions. The secondary antibodies were used at 1:5000 dilutions. The same membranes were stripped and incubated with antibodies against total ERK, JNK and p38 (1:2000; Zhang et al. 2004). The membranes were stripped again and re-probed with an anti-actin antibody (1:5000) to assure equal loading of the samples. All Western blot analyses were performed a minimum of twice.

Quantification and data analysis

The behavioral data were analyzed as time spent on the saline-paired side subtracted from time spent on the drug-paired side and were presented as mean ± SEM. Two-way repeated measure ANOVA with test as within factors and genotype and treatment as between-subjects were used, followed by one-way ANOVA test. Pair-sample t-test was used for within-subjects comparisons. The results for Western blotting were analyzed using densitometry. Ratios of phospho- to total ERK, JNK and p38 densities were calculated for each sample. Saline and No-CPP controls were set at 1. A one-way ANOVA was used to analyze changes in MAPK activation. Statistically significant level was set at p<0.05.

Results

DA D1 receptor mutant mice do not acquire CPP at multiple doses of cocaine

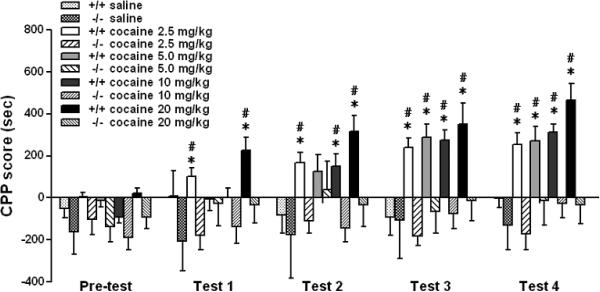

To investigate the role of D1 receptors in the rewarding effects of cocaine, we used 5 groups each of D1 receptor mutant and wild-type mice at 4 different cocaine doses and saline (0, 2.5, 5, 10 and 20 mg/kg, n=10–16 mice per group) to perform a CPP study. Following 4 conditioning sessions, there was a significant main effect of genotype (F (1,130)=46.507, p<0.001) and treatment (F (4,130)=4.489, p<0.01). Subsequent pair-sample t-tests indicated that wild-type mice had developed CPP at the first test session with 2.5 and 20 mg/kg cocaine, at the second test session with 10 mg/kg cocaine and at the third test session with 5 mg/kg cocaine. There was no CPP in D1 receptor mutant mice after conditioning at all cocaine doses and following saline treatment (Fig. 2, F (4,58)=0.558, p>0.05). One-way ANOVA analysis revealed that there was a significant difference between D1 receptor mutant mice and wild-type at all 4 cocaine doses (2.5 mg/kg: F (1,27)=40.921, p<0.001; 5 mg/kg: F (1,24)=5.769, p<0.05; 10 mg/kg: F (1,27)=14.490, p<0.01; 20 mg/kg: F (1,27)=10.385, p<0.01). Further analysis revealed that D1 receptor mutant and wild-type mice showed significant differences after 1 conditioning session at 2.5 and 20 mg/kg cocaine doses, and after 2 conditioning sessions at 5 and 10 mg/kg cocaine doses. There was no difference between D1 receptor mutant and wild-type mice following saline treatment (F (1,21)=0.722, p>0.05). These results suggest that D1 receptors are necessary for cocaine-induced CPP. Moreover, because of the acquisition deficit, the D1 receptor mutant mouse model is not suitable for investigating the role of this receptor in the extinction of cocaine-induced CPP.

Fig. 2.

D1 receptor mutant mice do not acquire CPP at multiple cocaine doses. Five groups each of D1 receptor mutant (D1−/−) and wild-type (WT) mice received either cocaine (2.5, 5, 10, 20 mg/kg, n=12–16 per group) or saline (n=10 per group) injections alternatively and were confined to CPP chambers. Mice were then tested for place preference without injections at the indicated time points. Results represent mean ± SEM time spent on the drug-paired side minus the saline-paired side. Wild-type mice showed significant place preference at all 4 cocaine doses. In contrast, D1 receptor mutant mice did not. Saline-treated D1 receptor mutant and wild-type mice did not show significant preference. *p<0.05 compared with the same mouse group before drug administration (pre-test). #p<0.05 compared between two genotype at the same dose and test.

DA D3 receptor mutant mice show equal CPP acquisition and reinstatement but delayed extinction compared to wild-type mice

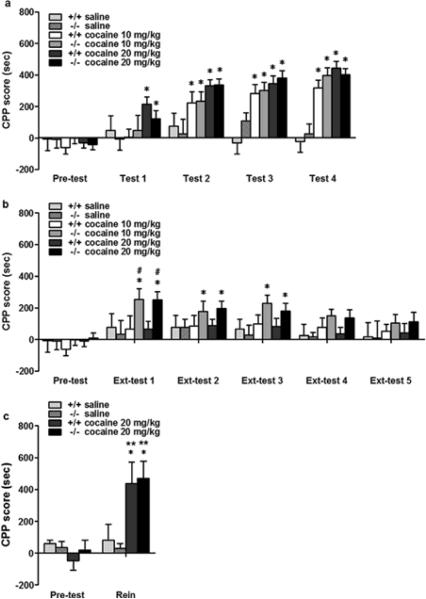

We next investigated the role of the D3 receptor in the acquisition, extinction and reinstatement of cue-elicited cocaine seeking. We used 3 groups each of D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice at 2 different cocaine doses and saline (0, 10 and 20 mg/kg, n=10–22 mice per group). There was a significant main effect of treatment (F (2,80)=21.268, p<0.001) but not genotype (F (1,80)=0.021, p>0.05) after conditioning. D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice developed similar levels of CPP after conditioning (Fig. 3a, wild-type 10 mg/kg: F (4,49)= 9.916, p<0.001; wild-type 20 mg/kg: F (4,109)=18.520, p<0.001; D3 receptor mutant 10 mg/kg: F (4,49)=8.118, p<0.001; D3 receptor mutant 20 mg/kg: F (4,109)=21.348, p<0.001). Subsequent pair-sample t-tests revealed that D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice had developed CPP at the second test session with 10 mg/kg cocaine. At the 20 mg/kg cocaine dose, wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice revealed CPP at the first test session. D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice do not show CPP acquisition after saline injections (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

D3 receptor mutant mice show similar CPP acquisition and reinstatement but delayed extinction compared to wild-type mice. a. CPP acquisition. Three groups each of D3 receptor mutant (D3−/−) and wild-type (WT) mice received either cocaine (10, 20 mg/kg, n=10–22 each) or saline (n=10 each) injections alternatively and were confined to specific compartments. These mice were tested for place preference without injections. Both D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice showed equal CPP acquisition at 10 and 20 mg/kg cocaine doses but not following saline treatment. b. Extinction. Once acquired CPP, these mice (n=10–14 each) received saline injections and were confined to both sides alternatively. Extinction tests were performed at the indicated time points. Wild-type mice showed extinction of CPP on ext-test 1 and thereafter. D3 receptor mutant mice exhibited delayed extinction compared to wild-type mice. c. Reinstatement. One day after the last extinction test, mice (n=6 each) received an i.p. cocaine (20 mg/kg) injection and were tested for place preference. Both D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice with prior exposure to cocaine but not to saline exhibited CPP following cocaine injections. Results represent mean ± SEM time spent on the drug-paired side minus the saline-paired side. *p<0.05 compared with the same mouse group before drug administration (pre-test). **p<0.05 compared with the last extinction test of the same mouse group. #p<0.05 compared between two genotype at the same cocaine dose and test.

Based on the finding that there was no obvious difference in CPP induction between D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice at these 2 cocaine doses, we next investigated whether the D3 receptor modulates extinction of cocaine-induced CPP. After 6 days of extinction training, there was a significant main effect of genotype (F (1,64)=5.300, p<0.05) but not treatment (F (2,64)= 1.987, p>0.05) at Ext-test 1 (Day 21). Compared to preconditioning tests, wild-type mice showed CPP extinction whereas D3 receptor mutant mice did not (Fig. 3b, wild-type 10 mg/kg: F (1,19)=0.757, p>0.05; wild-type 20 mg/kg: F (1,27)=1.742, p>0.05; D3 receptor mutant 10 mg/kg: F (1,19)=23.225, p<0.001; D3 receptor mutant 20 mg/kg: F (1,27)=15.672, p<0.01). Moreover, there is a significant difference between D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice at both cocaine doses (10 mg/kg group: F (1,19)=8.037, p<0.05; 20 mg/kg group: F (1,27)=4.434, p<0.05). Subsequent analysis revealed that D3 receptor mutant mice showed significant preference compared to pre-tests at Ext-tests 1–3, and these mutant mice did not show CPP extinction until Ext-tests 4 and 5.

Because both D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice eventually exhibit CPP extinction, we studied whether these mice would show cocaine-induced CPP reinstatement. One day after the last extinction test, mice were given an i.p. injection of cocaine (20 mg/kg) and were tested for CPP. There was a significant main effect of treatment (F (1,21)=11.655, p<0.01) but not genotype (F (1,21) =0.015, p>0.05). D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice that had exhibited CPP extinction showed significant preference to drug-paired side compared to pre-tests (Fig. 3c, D3 receptor mutant: F (1,11)=13.372, p<0.01; wild-type: F (1,11)=10.798, p<0.01), and compared to the last extinction test (D3 receptor mutant: F (1,11)=9.623, p<0.05; wild-type: F (1,11)=5.487, p<0.05). Moreover, there was no difference between D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice in the level of CPP (Fig. 3c). Finally, a cocaine injection did not induce preference in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice previously treated with saline (Fig. 3c). Together, these results suggest that, at the cocaine doses used, D3 receptors contribute to the extinction but not the acquisition or reinstatement of cue-elicited cocaine seeking.

ERK, but not JNK and p38, is activated in wild-type mice but not in D1 receptor mutant mice following CPP acquisition

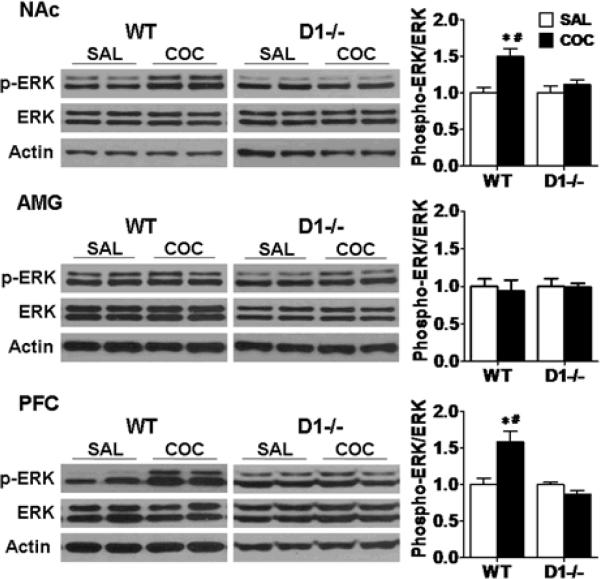

D1 receptor mutant mice do not readily acquire CPP at multiple cocaine doses. To investigate whether there is a corresponding loss of induction of ERK in D1 receptor mutant mice, we determined levels of phospho-ERK in mice receiving 20 mg/kg of cocaine or saline injections following CPP induction. All mice were sacrificed immediately after the last CPP acquisition test which was 20 minutes (day 14). ERK activation, as reflected by an increase in phospho-ERK levels, was quantified by Western blotting. In wild-type mice (n=7), ERK was activated in the NAc and PFC as compared to the saline-treated group (Fig. 4, NAc: F (1,13)= 14.437, p<0.01; PFC: F (1,13) =9.643, p<0.01). There was no significant change in phospho-ERK levels in the AMG in wild-type mice (Fig. 4, F (1,13)=0.191, p>0.05). In sharp contrast, there were no significant changes in phospho-ERK levels in all three brain regions in D1 receptor mutant mice (n=6) following cocaine treatment compared to saline-treated control mice (Fig. 4). There was a significant difference in ERK activation in the NAc and PFC between D1 receptor mutant and wild-type mice (Fig. 4, NAc: F (1,12)=8.078, p<0.05; PFC: F (1,12)=13.390, p<0.01).

Fig. 4.

ERK is activated in the NAc and PFC in wild-type mice and not in D1 receptor mutant mice following CPP expression. Mice were given cocaine (COC, 20 mg/kg) or saline (SAL) injections and were sacrificed immediately after the last test. Western blotting were performed using brain samples from D1 receptor mutant (D1−/−, n=6 each) and wild-type (WT, n=7 each) mice after CPP acquisition test. Ratios of phospho-ERK relative to total ERK protein levels in the NAc, AMG and PFC were analyzed. Data were expressed as mean± SEM relative to saline controls that were set as 1. Actin levels were used as a loading control. *p<0.05 compared with the saline control group of the same genotype. #p<0.05 compared with cocaine-treated D1 receptor mutant mice.

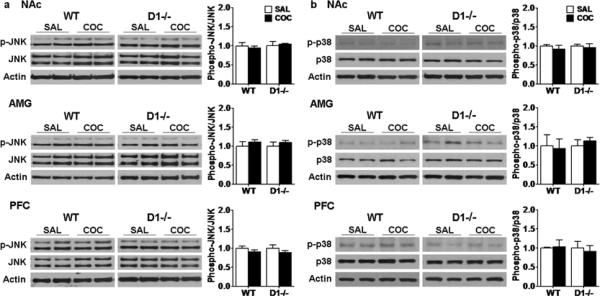

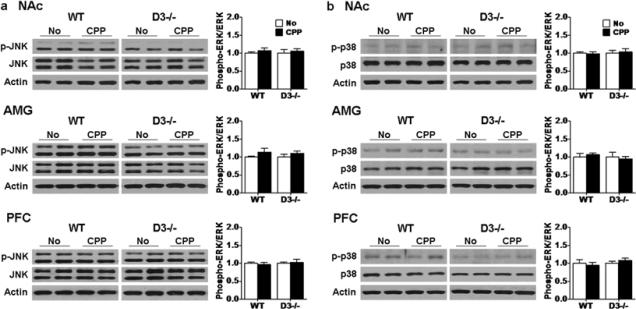

We also investigated potential changes in the activation of other members of the MAPK family following acquisition of cocaine-induced CPP using the same brain samples. No obvious changes in phospho-JNK and p38 levels were found in any of the 3 brain regions in D1 receptor mutant mice and wild-type mice following CPP acquisition or saline treatment (Fig. 5, p>0.05). Together, these results suggest that ERK, but not JNK and p38, is activated in the NAc and PFC in wild-type mice but not D1 receptor mutant mice following CPP acquisition.

Fig. 5.

JNK and p38 are not obviously activated in wild-type and D1 receptor mutant mice following CPP expression. Western blotting for a JNK and b p38 were performed using samples from D1 receptor mutant (D1−/−, n=6 each) and wild-type (WT, n=7 each) mice after CPP acquisition test as before. Ratios of phospho-JNK and phosphor-p38 relative to total JNK and p38 protein levels in the NAc, AMG and PFC were analyzed. Data represent mean± SEM relative to saline controls that were set as 1. Actin levels were used as a loading control.

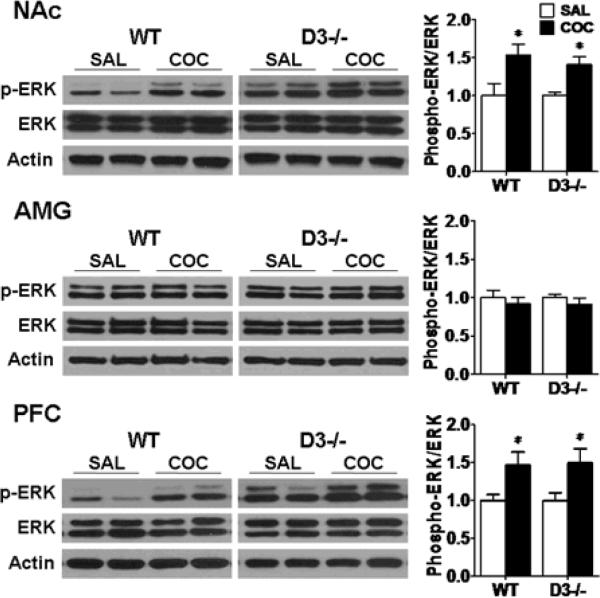

ERK, but not JNK and p38, is similarly activated in wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice following CPP acquisition

DA D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice show apparently equal acquisition of cocaine-induced CPP. We investigated the status of the 3 major MAPKs in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type (n=8 each) mice following CPP expression tests. ERK was activated in the NAc and PFC in D3 receptor mutant mice compare to saline-treated control group (Fig. 6, NAc: F (1,15)=13.906, p<0.01; PFC: F (1,15)=5.105, p<0.05). In wild-type mice, ERK was also activated in the NAc and PFC as compared to the saline-treated group (Fig. 6, NAc: F (1,15)=6.436, p<0.05; PFC: F (1,15)=5.933, p<0.05). Moreover, there were no differences in phospho-ERK levels in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice (Fig 6, p>0.05). In contrast, no significant changes in phospho-ERK levels in the AMG were observed in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice following CPP induction. There were also no obvious changes in phospho-JNK and p38 levels in any of the 3 brain regions in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice following CPP induction or saline treatment (Fig. 7, p>0.05). Together, these results suggest that ERK, but not JNK and p38, is similarly activated in the NAc and PFC in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice following CPP acquisition.

Fig. 6.

ERK is similarly activated in the NAc and PFC in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice following CPP expression. Mice were given cocaine (COC, 20 mg/kg) or saline and were sacrificed immediately after the last CPP test. Western blotting were performed using brain samples from D3 receptor mutant (D3−/−, n=8 each) and wild-type (WT, n=8 each) mice after CPP acquisition test. Ratios of phospho-ERK relative to total ERK protein levels in the NAc, AMG and PFC were analyzed. Data were expressed as mean± SEM relative to saline controls that were set as 1. Actin levels were used as a loading control. *p<0.05 compared with the saline control mouse group of the same genotype.

Fig. 7.

JNK and p38 are not obviously activated in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice following CPP expression. Western blotting for a JNK and b p38 were performed using brain samples from D3 receptor mutant (D3−/−, n=8 each) and wild-type (WT, n=8 each) mice after CPP acquisition test as before. Ratios of phospho-JNK and phospho-p38 over total JNK and p38 protein levels in the NAc, AMG and PFC were analyzed. Data represent mean± SEM relative to saline controls and were set as 1. Actin levels were used as a loading control.

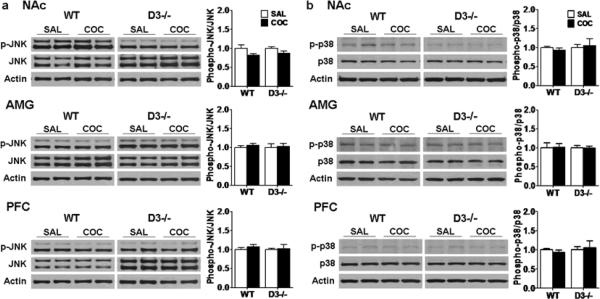

Sustained ERK activation in D3 receptor mutant mice compared to wild-type mice following 6 days of extinction training

D3 receptor mutant mice exhibit an apparently delayed CPP extinction compared to wild-type mice. We investigated whether there is a corresponding difference in MAPK activation in the 3 brain regions in D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice during extinction. We sacrificed D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice (n=7 each) following 6 days of extinction training and 1 extinction test at which time wild-type mice showed CPP extinction whereas D3 receptor mutant mice did not (Fig. 3b, day 21). The No-CPP control groups (n=6 each) were sacrificed at the same time. ERK was still activated in the NAc and PFC in D3 receptor mutant mice compared to wild-type mice and to the No-CPP control mice (Fig. 8, NAc: F (1,13)=51.984, p<0.001 compared to wild-type; compared to No-CPP: F (1,12)= 41.791, p<0.001; PFC: F (1,13)=9.482, p<0.05 compared to wild-type; compared to No-CPP: F (1,12)=111.978, p<0.001). Phospho-ERK levels remained high in the AMG in both wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice compared to the No-CPP groups (Fig. 8, wild-type: F (1,12)=10.546, p<0.01; D3 receptor mutant: F (1,12)=8.095, p<0.05). There was no difference in ERK levels in the AMG between wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice with or without CPP training.

Fig. 8.

Sustained ERK activation in D3 receptor mutant mice compared to wild-type mice following 6 days of extinction training and extinction test. Mice were given saline for 6 days of extinction training and were sacrificed immediately after extinction test which was 20 minutes. At the same time, the No-CPP (No) control groups were sacrificed 24 hours after the last saline injection in the behavioral room. Western blotting were performed using brain samples from D3 receptor mutant (D3−/−) and wild-type (WT) mice from the extinction groups (n=7 each) and No-CPP groups (D3−/− and WT: n=6 each). Ratios of phospho-ERK relative to total ERK levels in the NAc, AMG and PFC were analyzed. Data were expressed as mean± SEM relative to No-CPP controls that were set as 1. Actin levels were used as a loading control. *p<0.05 compared with the No-CPP control mouse group of the same genotype. #p<0.05 compared with cocaine-treated wild-type mice with CPP training.

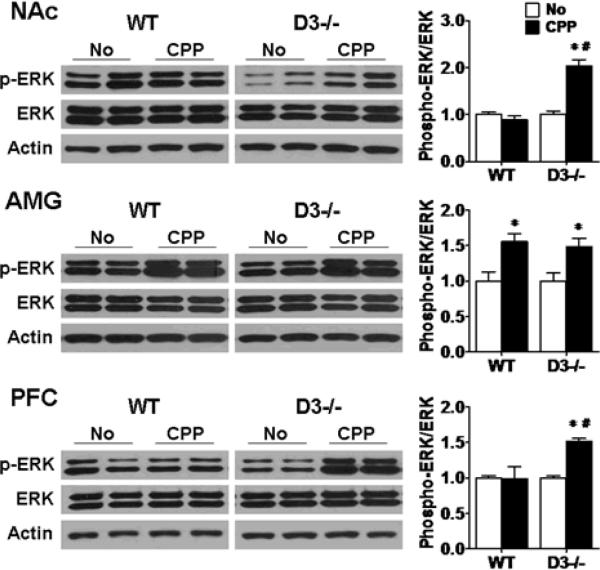

No significant changes in phospho-JNK and p38 levels were found in any of the 3 brain areas in wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice despite differences in CPP extinction (Fig. 9, p>0.05). These results suggest that the delayed extinction of CPP correlates with sustained ERK activation in the NAc and PFC in D3 receptor mutant mice.

Fig. 9.

JNK and p38 are not changed in wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice following 6 days of CPP extinction training and test. Western blotting for a JNK and b p38 were performed using brain samples from D3 receptor mutant (D3−/−) and wild-type (WT) mice from the extinction groups (n=7 each) and the No-CPP groups (D3−/− and WT: n=6 each) as before. Ratios of phospho-JNK and phospho-p38 relative to total JNK and p38 protein levels in the NAc, AMG and PFC were analyzed. Data were expressed as mean± SEM relative to No-CPP controls that were set as 1. Actin levels were used as a loading control.

Discussion

Previous work showed that DA D1 and D3 receptors modulate locomotor-stimulant and positive reinforcing effects of cocaine, as well as cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. A large percentage of D3 receptor-bearing neurons co-express D1 receptors especially in the NAc. However, how D1 and D3 receptors modulate the acquisition and extinction of cue-elicited cocaine seeking behavior and associated changes in MAPK signaling in different brain areas remains unclear. We have investigated this issue by using D1 and D3 receptor mutant mice and the CPP behavioral paradigm. Our results suggest that D1 and D3 receptors are differentially involved in learned association between cues and the rewarding properties of cocaine by regulating, at least in part, ERK activation in specific areas of the brain.

Using a CPP behavioral paradigm to investigate the role of D1 and D3 receptors in cue-elicited cocaine seeking

Environmental cues previously associated with reinforcing drugs can play a key role in relapse to drug-seeking behaviors in humans (Dackis and O'Brien 2005). This classical conditioning in which previously neutral cues acquire secondary reinforcing properties when paired with a primary reinforcer can be tested in the CPP paradigm (Bardo and Bevins 2000). CPP is thought to reflect aspects of cue-elicited drug seeking behavior because experimental animals approach and remain in contact with cues that have been paired with the effects of the drugs. CPP is thus useful in studying mechanisms related to cue-elicited drug seeking and its extinction. CPP is sensitive and can be reliably produced at low doses of drugs and with as little as one pairing of drugs. Testing for CPP is under drug-free conditions and drug-induced effects do not influence the final behavioral outcome. For these reasons, the CPP paradigm has been increasingly used to dissect neurobiological mechanisms underlying aspects of acquisition, extinction and reinstatement of drug seeking behavior, particularly in genetically modified mouse models (Xu et al. 1997; Kreibich and Blendy 2004; Karasinska et al. 2005; Zhang et al. 2006; Tzschentke 2007). In the current study, we used the CPP paradigm to evaluate the role of D1 and D3 receptors in cue-elicited cocaine seeking.

The DA D1 receptor is necessary for the induction and the D3 receptor modulates the extinction of cue-elicited cocaine seeking

We found that D1 receptor mutant mice do not acquire CPP over a wide range of cocaine doses (Fig. 2). This result is similar to those from pharmacological studies demonstrating that D1 receptor antagonists can block cocaine-induced CPP (Tzschentke 1998). This finding is also in agreement with those showing that D1 receptors mediate locomotor-stimulant and positive reinforcing effects of cocaine (Xu et al. 1994a; 1994b; 2000; Caine et al. 2007). DA is involved in reward-related learning (Schultz 1998; Ito et al. 2000; Wise 2004). Multiple DA signals can be detected during the extinction of cocaine self-administration, suggesting the involvement of DA receptors in this process (Stuber et al. 2005). A c-fos mutation in D1 receptor-bearing neurons delays CPP extinction without affecting acquisition (Zhang et al. 2006). A D1 receptor mutation delays the extinction of conditioned fear, yet does not affect acquisition (El-Ghundi et al. 2001). Whereas these results imply the importance of D1 receptors in modulating the extinction process, because of the acquisition deficit, the D1 receptor mutant mouse model is not suitable for investigating the role of this receptor in the extinction of cocaine-induced CPP.

While overwhelming evidence pointing to the critical involvement of D1 receptors in the general rewarding effects of cocaine, D1 receptor mutant mice have been reported to exhibit similar cocaine-induced CPP compared to wild-type mice (Miner et al. 1995; Karasinska et al. 2005). We note that these studies used a different line of D1 receptor mutant mice in which the D1 receptor gene was altered by the insertion of a drug selectable marker (Drago et al. 1994). These experiments were performed using different experimental protocols and the genetic background of the mice can be different from that used in the current study. Whether these factors contributed to the different results remains unclear.

D3 receptor mutant mice showed CPP induction that is similar to that of the wild-type mice at 2 cocaine doses (Fig. 3a) which is also similar to previous findings (Karasinska et al. 2005). Based on this finding, we used the D3 receptor mutant mouse model to investigate how this receptor may modulate CPP extinction. We found that the D3 receptor mutation attenuates extinction but not reinstatement (Fig. 3b and c). This new result implies that this receptor and related signaling pathways contribute to the extinction of CPP. Others have found that a partial D3 receptor agonist and D3 receptor antagonism inhibit cue-induced cocaine seeking behaviors (Pilla et al. 1999; Heidbreder et al. 2005; Di Ciano, 2008). The use of pharmacological agonists and antagonists for DA receptors during extinction training likely interfere with the process. Moreover, mutant mice carrying DA receptor gene mutations likely carry unknown developmental compensations that may obscure interpretations of the role of DA receptors, the use of an inducible genetic approach to change DA receptor levels may potentially provide more accurate insights into contributions of DA receptors to extinction of cue-elicited cocaine seeking in the future.

D1 and D3 receptors modulate ERK activation in different brain regions during acquisition and extinction of cue-elicited cocaine seeing

The NAc, BLA and PFC are part of the brain circuitry underlying cue-elicited cocaine seeking (Fuchs et al. 2002; Di Ciano and Everitt 2004; Weiss 2005; Feltenstein and See 2008; Koob and Volkow 2009). Lesions of the NAc impair cue-elicited cocaine seeking (Ito et al. 2004; Fuchs et al. 2004). The BLA mediates learning conditioned associations between the rewarding effects of cocaine and cues while the PFC contributes to decision-making and execution of goal-directed actions. Conditioned cues can activate these brain regions (Neisewander et al. 2000; Volkow et al. 2004; 2005). Extinction training engages the NAc and PFC to suppress cocaine seeking, and these brain areas also mediate reinstatement following non-contingent exposure to a previously self-administered drug (Peters et al. 2008). In the context of CPP, the excitatory drive from the BLA to the NAc is enhanced during cocaine seeking (Miller and Marshall 2005b). The NAc is involved in the retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-paired contextual memory (Miller and Marshall, 2005a). Drug-related cues can increase DA levels (Volkow et al. 2008; Koob and Volkow 2009). These results imply the general importance of DA receptors and associated signaling mechanisms in these brain regions in cue-elicited cocaine seeking.

The MAPK family is a key modulator of cellular signaling. ERK activation is regulated by D1 and D3 receptors following exposure to cocaine (Zhang et al. 2004; Bertran-Gonzalez et al. 2008). Inhibiting the ERK signaling pathway attenuates cocaine-induced behavioral responses (Pierce et al. 1999; Valjent et al. 2000; 2006; Ferguson et al. 2006). These findings suggest the importance of DA receptor-mediated ERK activation in cocaine-induced changes in synaptic plasticity and behavior. The NAc, BLA and PFC express D1 and D3 receptors (Missale et al. 1998). We thus investigated DA receptor-mediated MAPK activation in these brain regions following CPP acquisition. There is corresponding ERK activation in the NAc and PFC in wild-type and D3 receptor mice, but not in D1 receptor mutant mice (Fig. 4 and 6). We did not observe an obvious change in ERK activation in the AMG following CPP acquisition. Exposure to drug-associated cues increased ERK activation in the central AMG after 30 days, but not 1 day, of withdrawal (Lu et al. 2005), implying that the rise in phospho-ERK levels in AMG depends on withdrawal time. Similar to previous reports (Mizoguchi et al. 2004), no obvious changes in phospho-JNK and p38 levels were found in the NAc, AMG and PFC following CPP acquisition (Fig. 5 and 7). These results suggest that activation of the ERK signaling pathway in the NAc (Valjent et al. 2000; Miller and Marshall 2005a; Valjent et al. 2006; Ferguson et al. 2006) and PFC, but not JNK and p38, via D1 receptors contributes to the induction of cue-elicited cocaine seeking as measured by the CPP paradigm.

We found that D3 receptor mutant mice show a delayed CPP extinction and a sustained ERK activation in the NAc and PFC compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 8). These results suggest that the delayed extinction of CPP correlates with sustained ERK activation in the NAc and PFC. Notably, ERK is significantly and similarly activated in the AMG in both D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice at this time point (Fig. 8). This activation is unlikely due to non-contingent exposure to cocaine because simple exposure to cocaine without place conditioning and extinction does not lead to ERK activation in the AMG, NAc and PFC in the No-CPP mouse groups at the similar time point (Fig. 8). ERK activation in the AMG is implicated in the extinction of fear memory (Yang and Lu 2005; Henry et al. 2006; Myers and Davis 2007). It is possible that the heightened ERK activation is related to the new learning mediated by AMG. No significant changes in phospho-JNK and p38 levels were found in any of the 3 brain areas in wild-type and D3 receptor mutant mice despite differences in CPP extinction (Fig. 9). These results suggest that there is a heightened ERK activation in the AMG following CPP extinction. Moreover, the delayed extinction of CPP exhibited by D3 receptor mutant mice correlates with sustained ERK activation in the NAc and PFC. JNK and p38 are not significantly involved in the extinction of cue-elicited cocaine seeking.

D3 receptor mutant and wild-type mice show similar levels of cocaine-induced reinstatement in CPP (Fig. 3c). We will determine potential MAPK activation in different brain regions in these mice in the future. In the current study, we did not distinguish the NAc core and shell, and the BLA and central AMG. The future use of histological methods will be necessary. CPP is thought to reflect aspects of cue-elicited drug seeking (Bardo and Bevins 2000) and it may not fully model addicted states in humans as drugs are delivered noncontingently and only a few pairings are required to produce CPP. We will consider using the self-administration paradigm which is viewed to model active drug seeking and taking as an alternative in the future (Kalivas et al. 2006; Caine et al. 2007). It should be noted that this paradigm measures different processes than those by CPP (Bardo and Bevins 2000). Despite these unresolved issues, our results suggest that DA D1 and D3 receptors are differentially involved in cue-elicited cocaine seeking by regulating, at least in part, ERK activation in specific regions of the brain.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. H. Jiao for general help, and members of our laboratory for discussions, and Dr. D. Hall for critically reading the manuscript. M.X. was supported by grants from NIDA (DA17323 and DA025088). L.C. was supported, in part, by the China Scholarship Council.

References

- Adams JP, Sweatt JD. Molecular psychology: Roles for the ERK MAP kinase cascade in memory. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;42:135–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.42.082701.145401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo MT, Bevins RA. Conditioned place preference: what does it add to our preclinical understanding of drug reward? Psychopharm. 2000;153:31–43. doi: 10.1007/s002130000569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berglind WJ, Case JM, Parker MP, Fuchs RA, See RE. Dopamine D1 or D2 receptor antagonism within the basolateral amygdala differentially alters the acquisition of cocaine-cue associations necessary for cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine-seeking. Neurosci. 2006;137:699–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.08.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertran-Gonzalez J, Bosch C, Maroteaux M, Matamales M, Hérve D, Valjent E, Girault JA. Opposing patterns of signaling activation in dopamine D1 and D2 receptor-expressing striatal neurons in response to cocaine and haloperidol. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5671–5685. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1039-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caine SB, Thomsen M, Gabriel KI, Berkowitz JS, Gold LH, Koob GF, Tonegawa S, Zhang J, Xu M. Lack of cocaine self-administration in dopamine D1 receptor knockout mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13140–13150. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2284-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carta AR, Gerfen CR, Steiner H. Cocaine effects on gene regulation in the striatum and behavior: increased sensitivity in D3 dopamine receptor-deficient mice. Neuroreport. 2000;11:2395–2399. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200008030-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PC, Lao CL, Chen JC. Dual alteration of limbic dopamine D1 receptor-mediated signaling and the Akt/GSK3 pathway in dopamine D3 receptor mutant during the development of methamphetamine sensitization. J Neurochem. 2007;100:225–241. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe ES, McGinty JF. Cyclic AMP and mitogen-activated protein kinases are required for glutamate-dependent cyclic AMP response element binding protein and Elk-1 phosphorylation in the dorsal striatum in vivo. J. Neurochem. 2001;76:401–412. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dackis C, O'Brien C. Neurobiology of addiction: treatment and public policy ramifications. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:1431–1436. doi: 10.1038/nn1105-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Imperato A. Drugs abused by humans preferentially increase synaptic dopamine concentrations in the mesolimbic system of freely moving rats. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:5274–5278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P. Drug seeking under a second-order schedule of reinforcement depends on dopamine D3 receptors in the basolateral amygdala. Behav. Neurosci. 2008;122:129–139. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ciano P, Everitt BJ. Direct interactions between the basolateral amygdala and nucleus accumbens core underlie cocaine-seeking behavior by rats. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:7167–7173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1581-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drago J, Gerfen CR, Lachowicz JE, et al. Altered striatal function in a mutant mouse lacking D1A dopamine receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:12564–12568. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Ghundi M, O'Dowd BF, George SR. Prolonged fear responses in mice lacking dopamine D1 receptor. Brain Res. 2001;892:86–93. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03234-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feltenstein MW, See RE. The neurocircuitry of addiction: an overview. Br. J. Phar. 2008;154:261–274. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Fasano S, Yang P, Brambilla R, Robinson TE. Knockout of ERK1 enhances cocaine evoked immediate early gene expression and behavioral plasticity. Neuropsychopharm. 2006;31:2660–2668. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Weber SM, Rice HJ, Neisewander JL. Effects of excitotoxic lesions of the basolateral amygdala on cocaine-seeking behavior and cocaine conditioned place preference in rats. Brain Res. 2002;929:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(01)03366-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs RA, Evans KA, Parker MC, See RE. Differential involvement of the core and shell subregions of the nucleus accumbens in conditioned cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking in rats. Psychopharm. 2004;176:459–465. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1895-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidbreder CA, Gardner EL, Xi ZX, Thanos PK, Mugnaini M, Hagan JJ, Ashby CR., Jr. The role of central dopamine D3 receptors in drug addiction: a review of pharmacological evidence. Brain Res. Rev. 2005;49:77–105. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herry C, Trifilieff P, Micheau J, Luthi A, Mons N. Extinction of auditory fear conditioning requires MAPK/ERK activation in the basolateral amygdala. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2006;24:261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04893.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: The role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2006;29:565–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Dalley JW, Howes SR, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Dissociation in conditioned dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens core and shell in response to cocaine cues and during cocaine-seeking behavior in rats. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:7489–7495. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07489.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito R, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Differential control over cocaine-seeking behavior by nucleus accumbens core and shell. Nat. Neurosci. 2004;7:389–397. doi: 10.1038/nn1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, O'Brien C. Drug addiction as a pathology of staged neuroplasticity. Neuropsychopharm. 2008;33:166–180. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Peters J, Knackstedt L. Animal models and brain circuits in drug addiction. Mol. Interv. 2006;6:339–344. doi: 10.1124/mi.6.6.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasinska JM, George SR, Cheng R, O'Dowd BF. Deletion of dopamine D1 and D3 receptors differentially affects spontaneous behaviour and cocaine-induced locomotor activity, reward and CREB phosphorylation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2005;22:1741–1750. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauer JA, Malenka RC. Synaptic plasticity and addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:844–858. doi: 10.1038/nrn2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Ahmed SH, Boutrel B, Chen SA, Kenny PJ, Markou A, O'Dell LE, Parsons LH, Sanna PP. Neurobiological mechanisms in the transition from drug use to drug dependence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27:39–749. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharm Rev. 2009:1–22. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreibich AS, Blendy JA. cAMP response element-binding protein is required for stress but not cocaine-induced reinstatement. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:6686–6692. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1706-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Mao L, Zhang G, Papasian CJ, Fibuch EE, Lan H, Zhou HF, Xu M, Wand JQ. Activity-dependent modulation of limbic dopamine D3 receptors by CaMKII. Neuron. 2009;61:425–438. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Hope BT, Dempsey J, Liu SY, Bossert JM, Shaham Y. Central amygdala ERK signaling pathway is critical to incubation of cocaine craving. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8:212–219. doi: 10.1038/nn1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Koya E, Zhai H, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Role of ERK in cocaine addiction. Trends. Neurosci. 2006;29:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson BJ, Bossert JM, Simmons DE, Nozaki N, Nagarkar D, Kreuter JD, Hope BT. Cocaine-induced CREB phosphorylation in nucleus accumbens of cocaine-sensitized rats is enabled by enhanced activation of extracellular signal-related kinase, but not protein kinase A. J Neurochem. 2005;95:1481–1494. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Marshall JF. Molecular substrates for retrieval and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated contextual memory. Neuron. 2005a;47:873–884. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller CA, Marshall JF. Altered Fos expression in neural pathways underlying cue-elicited drug seeking in the rat. E. J. Neurosci. 2005b;21:1385–1393. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner LL, Drago J, Chamberlain PM, Donovan D, Uhl GR. Retained cocaine conditioned place preference in D1 receptor deficient mice. Neuroreport. 1995;6:2314–2316. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199511270-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missale C, Nash SR, Robinson SW, Jaber M, Caron MG. Dopamine receptors: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 1998;78:189–225. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.1.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizoguchi H, Yamada K, Mizuno M, Mizuno T, Nitta A, Noda Y, Nabeshima T. Regulations of methamphetamine reward by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2/ets-like gene-1 signaling pathway via the activation of dopamine receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:1293–1301. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KM, Davis M. Mechanisms of fear extinction. Mol. Psychiatry. 2007;12:120–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, Baker DA, Fuchs RA, Tran-Nguyen LT, Palmer A, Marshall JF. Fos protein expression and cocaine-seeking behavior in rats after exposure to a cocaine self-administration environment. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:798–805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00798.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Franklin KBJ. The mouse brain in stereotaxic Coordinates. Academic Press; San Diego: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Peters J, LaLumiere RT, Kalivas PW. Infralimbic prefrontal cortex is responsible for inhibiting cocaine seeking in extinguished rats. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:6046–6053. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1045-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce RC, Pierce-Bancroft AF, Prasad BM. Neurotrophin-3 contributes to the initiation of behavioral sensitization to cocaine by activating the Ras/Mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction cascade. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:8685–8695. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-19-08685.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilla M, Perachon S, Sautel F, Garrido F, Mann A, Wermuth CG, Schwartz J-C, Everitt BJ, Sokoloff P. Selective inhibition of cocaine-seeking behaviour by a partial dopamine D3 receptor agonist. Nature. 1999;400:371–375. doi: 10.1038/22560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridray S, Griffon N, Mignon V, Souil E, Carboni S, Diaz J, Schwartz JC, Sokoloff P. Coexpression of dopamine D1 and D3 receptors in islands of calleja and shell of nucleus accumbens of the rat: Opposite and synergistic functional interactions. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1998;10:1676–1686. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritz MC, Lamb RJ, Goldberg SR, Kuhar MJ. Cocaine receptors on dopamine transporters are related to self-administration of cocaine. Science. 1987;237:1219–1223. doi: 10.1126/science.2820058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz W. Predictive reward signal of dopamine neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1–27. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz JC, Diaz J, Bordet R, Griffon N, Perachon S, Pilon C, Ridray S, Sokoloff P. Functional implications of multiple dopamine receptor subtypes: the D1/D3 receptor coexistence. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 1998;26:236–242. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(97)00046-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber GD, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Extinction of cocaine self-administration reveals functionally and temporally distinct dopaminergic signals in the nucleus accumbens. Neuron. 2005;46:661–669. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmeier DJ, Song WJ, Yan Z. Coordinated expression of dopamine receptors in neostriatal medium spiny neurons. J. Neurosci. 1996;16:6579–6591. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-20-06579.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas GM, Huganir RL. MAPK cascade signaling and synaptic plasticity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference paradigm: a comprehensive review of drug effects, recent progress and new issues. Prog. Neurobiol. 1998;56:613–672. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference (CPP) paradigm: update of the last decade. Addict. Biol. 2007;12:227–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2007.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corvol JC, Pages C, Besson MJ, Maldonado R, Caboche J. Involvement of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascade for cocaine-rewarding properties. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:8701–8709. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08701.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Pascoli V, Svenningsson P, et al. Regulation of a protein phosphatase cascade allows convergent dopamine and glutamate signals to activate ERK in the striatum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:491–496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408305102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valjent E, Corbille AG, Bertan-Gonzalez J, Hérve D, Girault JA. Inhibition of ERK pathway or protein synthesis during reexposure to drugs of abuse erases previously learned place preference. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:2932–2937. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511030103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ. The addicted human brain viewed in the light of imaging studies: brain circuits and treatment strategies. Neuropharm. 2004;47:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Ma Y, Fowler JS, Wong C, Ding YS, Hitzemann R, Swanson JM, Kalivas P. Activation of orbital and medial prefrontal cortex by methylphenidate in cocaine-addicted subjects but not in controls: relevance to addiction. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3932–3939. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0433-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Telang F, Fowler JS, Logan J, Childress AR, Jayne M, Ma Y, Wong C. Dopamine increases in striatum do not elicit craving in cocaine abusers unless they are coupled with cocaine cues. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1266–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang JQ, Tang Q, Parelkar NK, Liu Z, Samdani S, Choe ES, Yang L, Mao L. Glutamate signaling to ras-MAPK in striatal neurons: Mechanisms for inducible gene expression and plasticity. Mol. Neurobiol. 2004;29:1–14. doi: 10.1385/MN:29:1:01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss F. Neurobiology of craving, conditioned reward and relapse. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2005;5:9–19. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:483–494. doi: 10.1038/nrn1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Moratalla R, Gold LH, Hiro N, Koob GF, Graybiel AM, Tonegawa S. Dopamine D1 receptor mutant mice are deficient in striatal expression of dynorphin and in dopamine-mediated behavioral responses. Cell. 1994a;79:729–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90557-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Hu XT, Cooper DC, Moratalla R, Graybiel AM, White FJ, Tonegawa S. Elimination of cocaine-induced hyperactivity and dopamine-mediated neurophysiological effects in dopamine D1 receptor mutant mice. Cell. 1994b;79:945–955. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Koeltzow TE, Santiago GT, et al. Dopamine D3 receptor mutant mice exhibit increased behavioral sensitivity to concurrent stimulation of D1 and D2 receptors. Neuron. 1997;19:837–848. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80965-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Guo Y, Vorhees CV, Zhang J. Behavioral responses to cocaine and amphetamine in D1 dopamine receptor mutant mice. Brain Res. 2000;852:198–207. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)02258-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YL, Lu KT. Facilitation of conditioned fear extinction by D-cycloserine is mediated by mitogen-activated protein kinase and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase cascades and requires de novo protein synthesis in basolateral nucleus of amygdala. Neurosci. 2005;134:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Lou D, Jiao H, Zhang D, Wang X, Xia Y, Zhang J, Xu M. Cocaine-induced intracellular signaling and gene expression are oppositely regulated by the dopamine D1 and D3 receptors. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:3344–3354. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0060-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhang L, Jiao H, Zhang Q, Zhang D, Lou D, Katz J, Xu M. c-fos Facilitates acquisition and extinction of cocaine-induced persistent change. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:13287–13296. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3795-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]