Abstract

The complexes [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(CQ)Cl2] (1), [Ru(η6-benzene)(CQ)Cl2] (2), [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(CQ)(H2O)2][BF4]2 (3), [Ru(η6- p-cymene)(en)(CQ)][PF6]2 (4), [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(η6-CQDP)][BF4]2 (5) (CQ = chloroquine base; CQDP = chloroquine diphosphate; en = ethylenediamine) interact with DNA to a comparable extent to that of CQ and in analogous intercalative manner with no evidence for any direct contribution of the metal, as shown by spectrophotometric and fluorimetric titrations, thermal denaturation measurements, circular dichroism spectroscopy and electrophoresis mobility shift assays. Complexes 1–5 induced cytotoxicity in Jurkat and SUP-T1 cancer cells primarily via apoptosis. Despite the similarities in the DNA binding behavior of complexes 1–5 with those of CQ the antitumor properties of the metal drugs do not correlate with those of CQ, indicating that DNA is not the principal target in the mechanism of cytotoxicity of these compounds. Importantly, the Ru-CQ complexes are generally less toxic toward normal mouse splenocytes and human foreskin fibroblast cells than the standard antimalarial drug CQDP and therefore this type of compound shows promise for drug development.

Keywords: Anticancer drug, apoptosis, binding affinity, toxicity, DNA binding, ruthenium complexes

1. Introduction

Cisplatin, carboplatin and oxaliplatin are widely used as first line treatments for cancer; nevertheless, toxicity and resistance limit their clinical efficacy [1,2]. trans-Pt(II) [3–6], octahedral Pt(IV) [7], or polynuclear Pt complexes [8–10] have been proposed as alternatives but they have not yet reached clinical use. Ruthenium complexes are emerging as promising candidates for novel cancer therapies for several reasons: This metal has several oxidation states accessible under physiological conditions [11]; Ru(II) and Ru(III) preferentially form octahedral compounds that interact with macromolecules in a different manner from those of platinum; more importantly, ruthenium complexes are able to mimic iron in binding biologically relevant molecules such as albumin and transferrin and as a consequence their toxicity is much lower than that of platinum therapies [12]. Two Ru-based drugs are in clinical development: (ImH)[trans-RuCl4(DMSO)(Im)] (Im = imidazole) (NAMI-A) is effective against lung metastases [13–17]; although this compound interacts with DNA in vitro [15] such binding may not contribute to the anticancer mechanism. On the other hand, (IndH)[trans-RuCl4(Ind)2]) (Ind = indazole) (KP1019) is active against colon carcinomas [18,19, 20–24] and DNA has been proposed as a possible important target [23].

Organometallic compounds are another source of anticancer drugs with (η5-C5H5)2TiCl2 as the first of such species in clinical trials [25]. [Ru(η6-arene)(X)(Y–Z)] complexes (where Y–Z is a chelating ligand, and X is monoanionic ligand) are highly cytotoxic against human ovarian tumor cells [26–29] and they are thought to act through covalent Ru-DNA interactions [30,31]. Related compounds incorporating the 1,3,5-triaza-7-phosphaadamantane (PTA) ligand, e.g. [Ru(η6- p-cymene)(PTA)Cl2] (RAPTA-C), have shown activity against metastases and although their mechanism of action has not been established, a pH dependent interaction with DNA may be a key component [32].

We have been investigating ruthenium complexes of known drugs as potential new chemotherapeutic agents for different applications [33]. The complexes Ru(KTZ)2Cl2 and Ru(CTZ)2Cl2) (KTZ = ketoconazole; CTZ = clotrimazole) display enhanced activity against Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas’ disease, and lowered toxicity to normal mammalian cells, in relation to the free ligands. These properties are due to a dual mechanism involving Ru-DNA binding and sterol biosynthesis inhibition by KTZ or CTZ [34–36]. Ru(KTZ)2Cl2 also induces cytotoxicity and apoptosis-associated caspase-3 activation in several cancer cell lines with IC50 values ~ 25 µM; this complex is more effective than cisplatin at inducing PARP fragmentation and proapoptotic Bak expression, suggesting that Ru(II) and Pt(II) complexes act through alternative signaling pathways [37]. We have also designed new antimalarial agents derived from Ru complexes of chloroquine (CQ), which was the drug of choice for decades until parasite resistance became widespread [38–41]; binding CQ to Ru results in an enhancement of the efficacy against resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum. In a recent paper we described the complexes Ru(η6-arene)(CQ)L2 (1–4) and [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(η6-CQDP)][BF4]2 (5) (Fig. 1) (CQDP = chloroquine diphosphate), which are up to 5 times more active than CQ against resistant strains of Plasmodium falciparum [42], due an adequate combination of lipophilicity, basicity and structural features [43]. These arene-Ru-CQ complexes are also of great interest in cancer research, since (i) they are structurally related to the [Ru(η6-arene)(X)(Y–Z)] and [Ru(η6-p-cymene)PTA)Cl2] active compounds mentioned above; and (ii) CQ itself has some anticancer activity, induces preventive effects and enhances the effectiveness of other anticancer drugs [44–49]. It was thus reasonable to expect that a combination of both motifs in a single molecule would lead to enhanced antitumor activity. Indeed, [Ru(η6-p-cymene)Cl2(CQ)] (1) and [Ru(η6-p-cymene)η6-CQDP)][BF4]2 (5) were found to be active against HCT-116 colon cancer cell lines and against a dedifferentiated liposarcoma cell line LS141 (IC50 8 µM for complex 1), for which there are no chemotherapies [42].

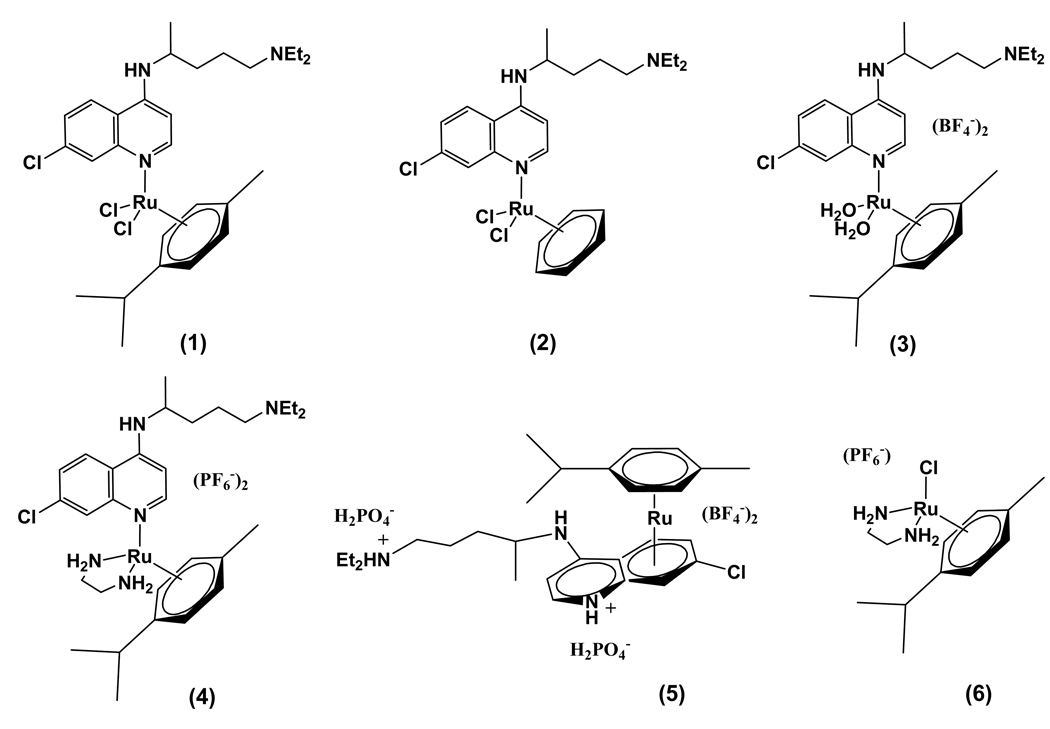

Fig. 1.

Structures of the complexes object of this study: [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(CQ)Cl2] (1); [Ru(η6-benzene)(CQ)Cl2] (2); [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(CQ)(H2O)2][BF4]2 (3); [Ru(η6-arene)(en)(CQ)][PF6]2 (4); [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(η6-CQDP)][BF4]2 (5); [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(en)Cl][PF6] (6).

As far as the mechanism of action is concerned, DNA can be considered a potential target for the Ru-CQ compounds because (i) CQ binds to DNA through intercalation [50–56], along with electrostatic interactions of the ionic side chain with the DNA phosphate groups [57–59]; and (ii) the related compounds [Ru(η6-arene)(X)(Y–Z)] exert their antitumor action through covalent binding of Ru to DNA. It was thus important to investigate the interactions of our compounds with DNA and to establish any possible relevance to antitumor behavior.

Here we show that complexes 1–5 are cytotoxic to Jurkat human T lymphocyte leukemia and SUP-T1 lymphoma cells with preferential induction of apoptosis; we also describe the interactions of these compounds with DNA in relation to the antitumor behavior and we show that the complexes display low toxicity toward normal mouse splenocytes and human foreskin fibroblasts. The combined results suggest that this family of compounds is promising for drug development.

2. Experimental

2.1. General

Calf Thymus (CT) DNA, pBR322 plasmid DNA, buffers and solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Solvents were purified by use of a PureSolv purification unit from Innovative Technology, Inc.; all other chemicals were used as received. Spectrophotometric studies and thermal denaturation experiments were performed on an Agilent 8453 diode-array spectrophotometer equipped with a HP 89090 Peltier temperature control accessory. Steady-state fluorescence measurements were carried out using a Spex Fluorolog Tau 2 fluorimeter (SPEX-Horiba Instruments, Inc., New Jersey) equipped with a thermostated cuvette holder. CD spectra were taken in a Chirascan CD Spectrometer also equipped with a thermostated cuvette holder. The complex [Ru(η6- p-cymene)(en)Cl][PF6] (6) (en = ethylenediamine) was prepared following the procedure described by Crabtree et al., using NH4PF6 instead of NaBPh4 [60].

The synthesis of complexes 1–5 was previously described by us in detail; the characterization was achieved by a combination of 1D and 2D 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, combined with FTIR measurements and DFT (DFT = density functional theory) calculations [42]; in short: [Ru(η6-arene)Cl2(CQ)] (1, 2). [Ru(η6-arene)Cl2]2 (1 mmol) and CQ (2 mmol) were stirred in an appropriate solvent (30 mL) under N2 at room temperature. The resulting mixture was evaporated to dryness and the product was redissolved and purified by filtration or crystallization. [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(H2O)2(CQ)][BF4]2 (3). [Ru(η6- p -cymene) Cl2]2 (0.65 mmol) and AgBF4 (2.61 mmol) were stirred in acetone (40 mL) at 55 °C under N2. The solution was filtered through celite; CQ (1.31 mmol) was added and the mixture was allowed to react at 55 °C for 20 h. The resulting solution was dried under vacuum to obtain a brown solid, which was purified by recrystallization. [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(en)(CQ)][PF6]2 (4). CQ (0.21 mmol) and AgPF6 (0.21 mmol) were added to a solution of [Ru(η6-p-cymene)Cl(en)][PF6] (0.21 mmol) in methanol. The mixture was allowed to react for 20 h under N2 at room temperature, then evaporated and the product was extracted with acetone and precipitated with diethyl ether. [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(η6-CQDP)][BF4]2 (5). [Ru(η6-p-cymene)Cl2]2 (0.49 mmol) was dissolved in water; AgBF4 (1.96 mmol) and chloroquine diphosphate (0.98mmol) were added under N2. The mixture was stirred for 20 h at 55 °C and then filtered through celite. The solvent was evaporated and the final product was dried under vacuum. Once isolated, the Ru(II) were found to be very stable as solids and as aqueous solutions. Compounds 1 and 2 rapidly (< 1 min) exchange one of the chloride ligands by water to form [Ru(η6-arene)(CQ)(H2O)Cl]Cl (1’ and 2’), as shown by electrical conductivity measurements. The UV-vis and NMR spectra of aqueous solutions of all the complexes remain unchanged over a period of 3 days. The purity of each complex was further verified by mass spectrometry and/or elemental analysis [40].

2.2. Interaction of metal complexes with CT DNA by spectrophotometric titration

The binding constants for the metal complexes with CT DNA were determined by absorption titration at room temperature through the stepwise addition of a CT DNA solution (10 µl, ~3 mM) to a solution of each drug (2 ml, 25 µM) in buffer (5 mM Tris/HCl and 50 mM NaClO4, pH 7.39). Absorption spectra were recorded at 330 and 343 nm and the titration was terminated when the intensity of those two bands did not change significantly upon further addition of DNA. An excellent fit for two binding constants Kb1 and Kb2 was obtained by using the Scatchard equation r/Cf = K(n-r) for ligand-macromolecule interactions with non-cooperative binding sites [61–64], where r is the number of moles of Ru complex bound to 1 mol of CT DNA (Cb/CDNA), n is the number of equivalent binding sites, and K is the affinity of the complex for those sites. Concentrations of free (Cf) and bound (Cb) complexes were calculated from Cf = C(1-α) and Cb = C-Cf, respectively, where C is the total Ru concentration. The fraction of bound complex (α) was calculated from α = (Af-A)/(Af-Ab), where Af and Ab are the absorbance of the free and fully bound drug at the selected wavelengths, and A is the absorbance at any given point during the titration. The plot of r/Cf vs. r gives the binding constants Kb as the slopes of the graphs.

For complex 6, samples of 2 ml of a solution 300 µM in the complex were incubated with 1–4 equivalents of CT DNA over a period of 24 h at 37°C, also in 5 mM Tris/HCl and 50 mM NaClO4, pH 7.39. The results were corrected with a blank containing buffer and the same amount of DNA as for each of the samples.

2.3. Interaction of metal complexes with CT DNA by fluorimetric titration

Excitation and emission wavelengths for all complexes were set to 343 and 380 nm with bandwidths of 4 nm and 8 nm, respectively. Using standard right-angle emission optics, fluorescence intensity measurements were recorded using the photon counting mode and corrected for any fluctuations of the 450-Watt Xenon arc lamp source by deflecting a portion of the excitation signal onto a separate photodiode. The measured intensity signals are thus reported in the ratio mode (S/R) as counts per second (S) measured on the emission photomultiplier over the photodiode current (R). For all fluorescence studies, the absorption of the sample at the wavelength of excitation was less than 0.1 in order to obviate inner filter effects. The fluorimetric titration was carried out at room temperature. Fixed amounts (2–5 µl) of a ~3 mM solution of CT DNA were added to a 3 µM solution of the metal complex, both in Tris/HCl buffer (5mM Tris/HCl and 50 mM NaClO4, pH = 7.39) and emission spectra were monitored at 380 nm until saturation was reached. Binding data were cast into the form of a Scatchard plot of r/Cf vs. r in a similar way as for absorption titration. In this case, α was calculated according to α = (Ff-F)/(Ff-Fb), where Ff and Fb are the fluorescence of the free and fully bound drug at the selected wavelength, and F is the fluorescence at any given point during the titration [65]. Kb is obtained from the slope of the plot.

2.4. Interaction of metal complexes with CT DNA by thermal denaturation experiments

Melting curves were recorded in 5 mM Tris/HCl buffer media at two different ionic strengths: 25 and 50 mM NaClO4 (pH=7.39). The absorbance at 260 nm was monitored for solutions of CT DNA (35 µM) before and after incubation with a solution of the drug under study (17.5 µM in Tris/HCl buffer) for 1 h at room temperature. The temperature was increased by 0.5 °C/min in the range 65–82°C and by 3°C/min in the ranges 25–65°C and 82–97°C.

2.5. Interaction of metal complexes with CT DNA by circular dichroism spectroscopy

Stock solutions (5 mM) of each complex were freshly prepared in water prior to use. The right volume of those solutions was added to 3 ml samples of an also freshly prepared solution of CT DNA (195 uM) in Tris/HCl buffer (5 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaClO4, pH=7.39) to achieve molar ratios of 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 drug/DNA. The samples were incubated at 37°C for a period of 20 h. All CD spectra of DNA and of the DNA-drug adducts were recorded at 25°C over a range 220–420 nm and finally corrected with a blank and noise reduction. The final data is expressed in molar ellipticity (millidegrees).

2.6. Interaction of metal complexes with plasmid pBR322 by Electrophoresis Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

10 µl aliquots of pBR322 plasmid DNA (20 µg/ml) in Tris/HCl 5 mM, 50 mM NaClO4, buffer (pH=7.39) were incubated at 37°C for 20 h with molar ratios between 0.25 and 1.0 of the Ru compounds. After incubation, the samples were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gel for ~1 h at 90 V using Tris-borate-EDTA buffer (TBE). Afterwards, the DNA was dyed with a solution of GelRed Nucleic acid stain (Biotum,Inc.) for ~ 20 min. Samples of free DNA and cisplatin-DNA adduct were used as controls. The experiment was carried out in a Bio-Rad Mini sub-cell GT horizontal electrophoresis system connected to a Bio-Rad Power pack 300 power supply.

2.7. Cytotoxicity assay by flow cytometry

Jurkat human T lymphocyte leukemia and Stanford University Pediatric (SUP)-T1 lymphoma cell lines [61] (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) in exponential growth phase, were seeded in a 24-well plate format at a density of 100,000 cells/well using 1 ml RPMI 1640 media (HyClone, Logan, UT), supplemented with antibiotics and 10% heat-inactivated newborn calf serum (HyClone, Logan, UT). After overnight incubation, the cells were incubated for 20 h to a range of concentrations of chemical compounds. Cells from each individual well were collected in an ice-cold tube and placed on ice and centrifuged at 1,400 rpm by 5 min at 4°C. The media was then removed and the cells were resuspended in 500 µl of staining solution, containing 2 µg/ml propidium iodide (PI) dissolved in FACS buffer (PBS, 0.5 mM EDTA, 2% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum, and 0.1% sodium azide) (PBS = phosphate buffered saline). After incubation in the dark on ice for 15 min, the stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry, using a Cytomic FC 500 (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL). The cytometric system is equipped with air-cooled argon-ion laser tuned to emit at 488 nm as excitation wavelength. The data were acquired and analyzed using CXP software (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL) specially designed for both functions. Each value was directly obtained from each histogram as percentage of viable or necrotic cells. In addition, corrected values were obtained by subtracting the cytotoxicity mean value of untreated cells from the cytotoxicity mean value of each concentration tested [67].

2.8. Apoptosis assays using flow cytometry

Jurkat human T lymphocyte leukemia cells were seeded in a 24-well plate at 100,000 cells/well using 1 ml RPMI media (HyClone, Logan, UT) supplemented with antibiotics and 10% heat-inactivated newborn calf serum (also referred as complete media). Cells were exposed for 16 h to 100 µM chemical compounds, collected in an ice-cold tube, and centrifuged at 1,400 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. Cells from each individual well were washed, first with cold complete media, and then with cold PBS. Staining was performed by resuspending the cells in 100 µl binding buffer (0.1 M HEPES, pH 7.4; 140 mM NaCl; 2.55 mM CaCl2) containing 1 µl of 25 µg/ml Annexin V-FITC (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) and 5 µl of 250 µg/ml PI. After incubation for 15 min on ice in the dark, cell suspensions were added with 400 µl of ice-cold binding buffer, gently homogenized and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry using a Cytomics FC 500 (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). For each sample, 10,000 individual events were collected and analyzed using CXP software (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). Prior to data acquirement, the flow cytometer was set up and calibrated utilizing unstained, single- (PI or Annexin V-FITC) and double- (Annexin V-FITC plus PI) stained cells.

2.9. Toxicity assay against primary cultures of mouse splenocytes by flow cytometry

Spleens were obtained from C57BL/6J female mice (8 to 10 weeks old) and transferred to a Petri dish containing complete media (see above) and minced into small pieces, after which the material was passed through a stainless steel-wire mesh, as previously described [68]. The dispersed cells were passed through 70 µm pore size filter to remove tissue debris using a tube with cell strainer cap (BD Falcon, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Cell suspensions of mouse splenocytes were exposed to 1 ml of red blood cell lysis solution (0.16 M NH4Cl, 10mM KHCO3, and 0.13 mM EDTA) for 2 min to eliminate erythrocytes, followed by one wash with 15 ml of complete media. After centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in complete media supplemented with 10 µg/ml of lipopolisaccharides (LPS) from E.coli bacteria (Sigma-Aldrich. St. Louis, MO), a powerful B lymphocyte mitogen, and incubated overnight at 37°C in a humid atmosphere of air plus 5% CO2. The viability of the splenocytes was evaluated the following day by trypan blue exclusion and cells were seeded at 100,000 cell/ml density of viable cells in a 24-well flat bottom plate. After overnight culture, stock solutions and dilutions of experimental Ru-CQ complex compounds were added in triplicate directly to each well containing LPS-stimulated splenocytes in complete media, incubated 20 h. Cell death/viability was monitored using PI and flow cytometry as described above.

2.10. Toxicity against human foreskin fibroblast cell line by the MTS assay

The normal human foreskin fibroblast cell line (Hs27, American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) was cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Mediatech, Inc. Herndon, VA), supplemented with antibiotics and 10% heat-inactivated bovine calf serum (HyClone. Logan, UT) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Fibroblasts were seeded in flat-bottomed 96-well plates at 5,000 cells/well density, in a total volume of 100 µl of medium and incubated overnight to allow cell attachment. Cellular debris and non-attached cells were washed out with fresh medium previously to addition of ruthenium-based compounds. After addition of chemical compounds, the fibroblasts were incubated for 20 h, followed by addition of 20 µl of CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution reagent (MTS reagent; Promega. Madison, WI) to each well, and incubated for an additional 2 h before recording the absorbance (optical density, OD). The colored formazan product was measured by absorbance at 490 nm with a reference wavelength of 650 nm. Therefore, for each individual well the absorbance value at 650 nm was automatically subtracted from the absorbance value at 490 nm to eliminate signals coming from excess cell debris, fingerprints, and other nonspecific artifacts. All absorbance measurements were done by the use of a VERSAmax tunable microplate reader equipped with Softmax® PRO Version 4.0 software (MDS, Inc. Toronto, Canada). Wells containing cells that were not exposed to ruthenium compounds (also annotated as untreated cell) were taken as 100% of viability/vitality. As a positive control for cytotoxicity, hydrogen peroxide was included at a concentration known to affect cell viability [69]. All chemical compounds were dissolved in physiological saline solution, except complex 3 and complex 4 which were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Also, the diluents of ruthenium compounds, physiological saline solution (0.9% NaCl) and DMSO, were tested at the same concentration as contained in the samples as a control for non-specific effects, and to be used to normalize the raw data values. In addition, average from triplicate wells, included in each assay, filled with medium (without cells) containing the same volumes of medium and MTS reagent as experimental wells, was subtracted from every experimental point to remove background absorbance. Every experimental point, as well as all controls, was assessed in triplicate.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interaction of complexes 1–6 with CT DNA

The key role of DNA in cell replication makes this biomolecule one of the most interesting targets in cancer chemotherapy. Platinum complexes owe their antitumor activity to strong covalent interactions with the nucleotide bases of DNA [70]. The Ru-based anti-metastatic agent NAMI-A was initially thought to act through DNA interactions but it is now accepted that its activity is due to a combination of angiogenesis control [17,71] and anti-invasive properties toward tumor cell blood vessels. On the other hand, DNA has been shown to be a primary target for other Ru(III) and Ru(II) compounds, such as pentaamine(purine)ruthenium(III) complexes [72], cis- and trans-RuCl2(dmso)4 [73,74] or KP1019 [23]. [Ru(η6-arene)(X)(Y–Z)] compounds are activated by replacement of a monoanionic X ligand by water, followed by nucleophilic attack by the nucleotide bases of DNA to form covalent monofunctional adducts [26,27,30,31]. The phosphate groups of the nucleotides act as initial binding sites, prior to coordination of ruthenium to guanine [75,76]; arene-base stacking, arene intercalation and minor groove binding (in the case of polycyclic arenes) also contribute to the binding of these Ru(II) complexes to double helical DNA [30].

The molecular design in our arene-Ru(II) complexes incorporates CQ, a known DNA intercalator, in the coordination sphere of the metal. We have reported data on the antitumor action of complexes 1 and 5 against colon and liposarcoma cell lines [42] and in this paper we disclose new results concerning other tumor cells. In view of the observed anticancer activity, we have tried to establish whether the new drugs are able to bind DNA, what the nature of such binding is, how the structural particularities of these molecules affect the interactions and ultimately, whether those interactions contribute to the antitumor activity and/or to any toxicity against normal cells. The DNA binding ability of the five complexes was investigated by use of several techniques and directly compared to those of CQ and of the reference compound [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(en)Cl]PF6 (6), a representative example of an arene-Ru(II) complex with known antitumor activity [26] that does not contain CQ.

3.1.1. Spectrophotometric and fluorimetric titrations

The interaction of complexes 1–5 and CQDP with CT DNA was followed by spectrophotometric titrations. All compounds display two intense bands at 330 and 343 nm attributed to CQ bound to ruthenium (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1) whose intensity decreases upon incremental addition of CT DNA, clearly indicating that an interaction is taking place between the metal complex and DNA. From the Scatchard plot of the changes at 330 and 343 nm two binding affinities Kb1 and Kb2 can be calculated, corresponding to two major binding interactions with cooperative effects [61–64]. This interaction was also studied by fluorimetric titration; samples were excited at 343 nm and the emission at 380 nm was monitored upon consecutive additions of a solution of DNA (see Supplementary material, Fig. S2). As for the absorption titration, the quenching of the emission at 380 nm indicates an interaction involving two major binding affinities that are, within experimental error, in good agreement with the results from absorption measurements.

Table 1 contains the average values of Kb1 and Kb2 obtained from the absorption and emission titrations for complexes 1–5 and for CQDP; we note that CQDP and all five metal complexes interact with DNA to a comparable extent and most likely in an analogous manner. It is known that free CQDP displays a double action on DNA; the side chain of the CQDP molecule interacts electrostatically with the phosphate groups, while the aromatic rings intercalate between nucleotide bases [50–59]. In the case of the Ru-CQ complexes 1–5, the overall positive charge and especially the presence of the metal ion could offer additional binding possibilities, such as covalent bonding of Ru with nitrogen bases. The reference complex 6 does not contain CQ and therefore lacks the intense bands at 330 and 343 nm; we therefore followed the d-d transition at 365 nm but no change was observed when 6 was titrated with DNA under similar conditions (data not shown). Incubating 6 with 1–4 eq of DNA at 37 °C for 24 h caused a slight decrease in the intensity of the 365 nm band (See Supplementary material, Fig. S3), in agreement with a slow covalent interaction, clearly different from that of CQDP and complexes 1–5.

Table 1.

Binding affinities of complexes 1–5 calculated from the absorption and emission titrations at 25°C in 5mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaClO4 buffer, pH=7.39

| Absorption Titration | Emission Titration | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complex | Kb1 (x 107 M−1)a | Kb2 (x 105 M−1)a | Kb1 (x 107 M−1)b | Kb2 (x 105 M−1)b |

| CQDP | 1.07 ± 0.05 | 1.23 ± 0.68 | 2.63 | 4.38 |

| (1) | 0.75 ± 0.04 | 2.09 ± 0.89 | 8.82 | 1.64 |

| (2) | 1.43 ± 0.07 | 2.24 ± 0.73 | 3.45 | 2.37 |

| (3) | 0.13 ± 0.001 | 0.38 ± 0.47 | 0.66 | 3.71 |

| (4) | 1.58 ± 0.06 | 2.41 ± 0.11 | 3.38 | 1.08 |

| (5) | 2.10 ± 0.68 | 3.15 ± 0.12 | 0.12 | 3.54 |

average of values calculated at 330 and 343 nm

values calculated at 380 nm

3.1.2. Thermal denaturation experiments

In order to further probe whether the observed interaction between complexes 1–5 and DNA is due to intercalation, electrostatic interaction, or covalent bonding, thermal denaturation measurements were performed. The melting technique is a sensitive tool to detect even slight DNA conformational changes; a destabilizing interaction with the double helix (often covalent) is manifested as a decrease in the melting point (Tm), while a stabilizing interaction (intercalation or electrostatic) induces an increase of Tm [76]. Since in aqueous solution the complexes are all cationic [42] and at physiological pH the side chain of CQ will be partially protonated, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the DNA melting behavior for all complexes will have an electrostatic contribution, whose extent can be determined by using different ionic strengths of 5 mM Tris/HCl buffer. Table 2 shows the DNA behavior after 1 h of incubation with complexes 1–5, CQDP or the reference complex 6.

Table 2.

Change in the Tm of CT DNA when incubated for 1h at 25°C with 0.5 equivalents of each drug in 5 mM Tris/HCl buffer, pH=7.39

| Compound | ΔTm (°C) /1h incubation/25mM NaClO4 |

ΔTm (°C) /1h incubation/50m M NaClO4 |

|---|---|---|

| CQDP | +4.9 | +3.0 |

| (1) | +5.5 | +4.0 |

| (2) | +4.4 | +3.5 |

| (3) | +4.8 | +2.9 |

| (4) | +3.4 | +1.6 |

| (5) | +5.1 | +2.8 |

| (6) | −1.3 | −0.6 |

Complexes 1–5 containing CQ produce a stabilizing effect (increase in Tm) on DNA both at low and high Na+ concentration. In contrast, compound 6 caused a decrease in Tm (Table 2), in agreement with previously reported data, which were interpreted in terms of the formation of a covalent adduct with DNA [76]. Thermal stabilization of the double helix, as observed for compounds 1–5, can be ascribed to either the positive charge of the side chain of CQ, the overall positive charge of the complex after hydrolysis, or the intercalation of the aromatic rings of CQ. At low Na+ concentrations the increase of Tm is higher, most likely due to the complexes stabilizing DNA through both electrostatic binding and intercalation. On the other hand, at high salt concentration the stabilizing effects are reduced since the electrostatic component is lowered by the increased concentration of Na+ counterions. These results lead us to two main conclusions: (1) A covalent interaction between the Ru atom and the nucleotide bases does not seem to take place for complexes 1–5 since the stabilization effects do not significantly differ from those of CQDP; more importantly, a covalent interaction would tend to destabilize rather than stabilize DNA, as observed for cisplatin and for [Ru(η6-p-cymene)(en)(Cl)]+ complexes [76,77]. (2) Intercalation of the aromatic part of the CQ molecule prevails over electrostatic effects, as shown by the fact that doubling the concentration of salt has a relatively small effect on ΔTm. It is worth highlighting that the ΔTm values for complex 4 are consistently lower than those for the rest of the drugs at both Na+ concentrations, suggesting an extra destabilizing interaction, most likely between the NH2 groups of the ethylenediamine ligand and the nucleotide bases.

3.1.3. Circular dichroism spectroscopy studies

More detailed DNA conformational alterations can be detected by means of circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. Fig. 2 shows a typical CD spectrum of DNA in its B conformation, treated with increasing amounts of CQDP (racemic mixture) (Fig. 2A) and with the reference complex (6) (Fig. 2B). The band of the CD spectrum of DNA at 275 nm is due to stacking between base pairs, whereas the band at 248 nm is originated because of the right-handed helicity [78].

Fig. 2.

CD spectra of CT DNA incubated for 24 h at 37°C with CQDP at 0, 0.1, 0.3 and 0.5 ratios (A); and CT DNA incubated for 24 h at 37°C with the reference complex 6 at 0, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.5 ratios (B).

The effects of both CQDP and 6 on the secondary structure of CT DNA have been reported [57,76] and they agree with our results. CQDP is a chiral molecule and the (+) and (−) enantiomers give mirror image CD spectra [57], which explains the lack of CD bands for the racemate used in our experiments. Additionally, it has been determined by both spectrophotometric titrations and CD spectroscopy of pure CQDP enantiomers that the (−) enantiomer has a higher binding affinity for a given polynucleotide than the (+) one, with a ratio of 1.29 and 1.28 for poly (dG-dC).poly (dG-dC) and poly (dA-dT).poly (dA-dT) respectively [57]. This preferential binding of (−)-CQDP causes a change in the enantiomeric composition of the remaining drug not-bound to DNA, thus generating optical activity due to excess of free (+) CQDP. That phenomenon is clearly observed in Fig. 2A; the CD spectra after DNA was incubated with racemic CQDP shows two new sizable CD bands at 330 and 340 nm (inset) due to the presence of a higher proportion of free (+) CQDP. The changes in the 200–300 nm region can be attributed to either conformational changes in the double helix, or to the sum of the DNA band plus the appearance of (+) CQDP bands, or to both. When CT DNA is incubated with increasing amounts of 6 (Fig. 2B), a slight decrease of the intensities of the positive and especially the negative bands are observed. Those small changes in the stacking and the helicity of CT DNA are consistent with the non-intercalating binding mode of this complex, which forms covalent adducts and unwind the double helix by 7° [76].

Fig. 3 shows the changes induced on the CT DNA CD spectrum after incubation with increasing amounts of complexes 1–5 for 24 h at 37°C. A direct comparison with Fig. 2A and 2B leads to the conclusion that the effect of complexes 1–5 on CT DNA is analogous to that induced by racemic CQDP, confirming that the interaction of the Ru-CQ complexes takes place through the chloroquine moiety with a similar selectivity for the (−) enantiomer. The lack of changes in the negative band of the CD spectrum of CT DNA, in contrast to what was observed for 6, together with the fact that no other alteration different from what CQDP itself induces, suggests that no covalent metal-nucleotide bases adducts directly involving the Ru ion are formed. These results agree with our absorption and emission spectrophotometric titration data and thermal denaturation experiments.

Fig. 3.

CD spectra of CT DNA and CT DNA incubated with 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5 equivalents of complexes 1 (A), 2 (B), 3 (C), 4 (D) and 5 (E) for 20 h at 37°C.

3.1.4. Agarose gel electrophoresis studies

Modifications on the tertiary structure of DNA plasmid pBR322 were also investigated by agarose gel electrophoresis and the results are shown in Fig. 4. The plasmid pBR322 has two main forms: OC (open circular) and CCC (covalently closed circular). Changes in electrophoretic mobility of both forms are usually taken as evidence of direct metal-DNA interactions. Generally, the larger the retardation of supercoiled DNA (CCC), the greater the DNA unwinding produced by the drug [78]. Binding of cisplatin to plasmid DNA, for instance, results in a decrease in mobility of the CCC form and an increase in mobility of the OC form (lane 3, Fig. 4) [79].

Fig. 4.

Electrophoresis of DNA plasmid pBR322 incubated in 5 mM Tris/HCl buffer for 20 h at 37°C with cisplatin, CQDP, complex 1 and complex 6. Lanes 1 and 13: molecular marker; lane 2: DNA pBR322; lane 3: DNA treated with 0.5 eq. of cisplatin; lanes 4–6: DNA treated with 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 eq. of CQDP; lanes 7–9: DNA treated with 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 eq. of complex 1; lanes 10–12: DNA treated with 0.25, 0.5 and 1.0 eq. of complex 6.

Treatment with increasing amounts of CQDP (lanes 10–12) does not cause any significant effect either in the mobility of the CCC form or of the OC plasmid, indicating that this drug does not induce a noticeable alteration on the tertiary structure of the plasmid under these conditions. Complex 1 (lanes 7–9) displays an analogous behavior to that of CQDP, in agreement with the spectroscopic results, thus confirming that the interaction of this drug with DNA is comparable in manner and extent to that of chloroquine. Analogous results were obtained for complexes 2–5 (data not shown); in contrast, the formation of monofunctional covalent adducts of the reference compound 6 not containing CQ retards the mobility of the fast-running supercoiled form as a consequence of the unwinding of the double helix, especially at high molar ratios (lane 12). We therefore conclude that in the case of the Ru-CQ complexes 1–5, only the CQ moiety binds to DNA, while the metal ion or the ancillary ligands do not play an important role in the interaction with the double helix, although they are essential in modulating the physicochemical properties of the drugs.

3.2. Cytotoxic effect of ruthenium complexes 1–6 against human lymphoid cells analyzed by flow cytometry

3.2.1. Cytotoxicity on Jurkat and SUP-T1 cells

Loss of plasma membrane integrity is a characteristic of cell death. Cell cytotoxicity/viability was monitored by flow cytometry using the cell-impermeant, double-stranded nucleic acid intercalating dye, propidium iodide (PI). Cells with compromised plasma membrane were counted in comparison with the total population (n = 10,000 events) using a double strand nucleic acid staining solution (see Experimental section). Untreated cells were used as negative control. A positive control for cytotoxicity was obtained by incubating cells with media containing 500 µM hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), known as inducer of apoptosis and necrosis [69], to ensure that the flow cytometer was calibrated properly. Also, the diluents of ruthenium complexes, 0.9 % sodium chloride or DMSO, were tested at the same concentration as contained in the samples, as a control for non-specific effects. The compound [Ru(η6-arene)(en)Cl]PF6 (6), which features a structure similar to those of our complexes but lacks the CQ ligand, was also tested under identical conditions as a reference complex with known antitumor properties and low toxicity against normal cells [26–29]. Cell cytotoxicity data for complexes 1–5 on the human T lymphocyte Jurkat and SUP-T1 lymphocyte cell lines are summarized in Table 3, together with data for free CQDP and for the reference compound 6. We previously reported that complexes 1 and 5 have interesting antitumor properties against HCT-116 colon cancer and LS141 liposarcoma cells, with higher sensitivity to 1, especially in the case of the liposarcoma cells (IC50 = 8 µM), for which there are currently no effective therapies [42]. The new data obtained using the conditions described in the Experimental section show that complexes 1–5 exhibit cytotoxic behavior toward SUP-T1 and Jurkat cells in a range of concentrations from 54 to 153 µM (Table 3); these values are comparable to those observed for other arene-Ru complexes [26, 27, 32, 78]. Complexes 2–5 were, on average, twice as active as CQDP against the SUP-T1 line and displayed a slightly better behavior towards Jurkat cells. CQDP has been reported to exert its antitumor properties due to a combination of a lysosomotropic effect that potentiates apoptosis, the inhibition of some enzymes that regulate the cell cycle [44] and probably DNA interactions [50–56]. Although it is known that CQDP inhibits DNA and RNA polymerase activities [53], it is not clear whether that is directly related to its antitumor properties [44]. In an attempt to correlate the anticancer behavior of our compounds to their ability to interact with DNA, two main observations must be noted: 1) the modifications of DNA induced by CQDP and complexes 1–5 are comparable in extent and manner. Nevertheless, complexes 2–5 display a similar activity to CQDP against the Jurkat cell line, but a considerably different activity on SUP-T1 cells. 2) Despite the fact that all the new compounds interact in essentially the same way with DNA, the antitumor properties are in some cases significantly different within the same tumor cell line or between both Jurkat and SUP-T1 lines. Therefore, DNA interactions do not seem to be the principal mechanism of antitumor action.

Table 3.

Cytotoxic Concentration (CC)50 of Ruthenium compounds measured against Jurkat and SUP-T1 human cell lines analyzed by flow cytometry.

| CC50 (µM) a |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell line | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | CQDP |

| SUP-T1 | 128 | 88 | 54 | 75 | 70 | Non toxicb | 130 |

| Jurkat | 153 | 90 | 81 | 86 | 77 | 129 | 95 |

CC50 is defined as the concentration of drug required to disrupt the plasma membrane of 50% of cell population, compared to untreated cells, after 20 h of incubation. Cells with compromised plasma membrane were monitored using propidium iodide (PI) and flow cytometry.

Even when SUP-T1 cells, a human T-lymphoma cell line, were exposed to 100 µM of [Ru(η6-arene)(en)Cl]PF6 (6), the cytotoxicity measured was similar to that of untreated control cells. All values represent average obtained from triplicates.

On the other hand, it is interesting to point out that the CQ-containing complexes 1–5 are more active against both cancer cell lines tested than complex 6, which displays excellent antitumor properties against the A2780 human ovarian cancer cell line [26–29]. Under our experimental conditions, 6 inflicted moderate cytotoxicity on the Jurkat T lymphocyte leukemia cell line, but had no measurable effect on SUP-T1 lymphoma cells. A particularly important comparison is between complexes 4 and 6 and CQDP. Both metal complexes display similar molecular structures, containing p-cymene and a chelating ethylenediamine ligand. The presence of chloroquine in the coordination sphere of 4 is the major structural difference between these two compounds and that seems to result in a higher cytotoxicity against the cancer cells, when compared to complex 6 and also to CQDP. This is in line with our hypothesis that combining the organo-ruthenium fragment with CQ should lead to higher anticancer activity than any of the parent substructures. We also note that the π-bonded Ru-CQDP complex 5 was more active than the N-bonded Ru-CQ complex 1, in opposition to our previous observations on colon cancer and liposarcoma cells [42]. Compounds 1–5 are somewhat more active against SUP-T1 than against Jurkat, with the highest activity being observed for 3 against SUP-T1 cells and the lowest for complex 1 against Jurkat cells.

3.2.2 Apoptosis on Jurkat cells

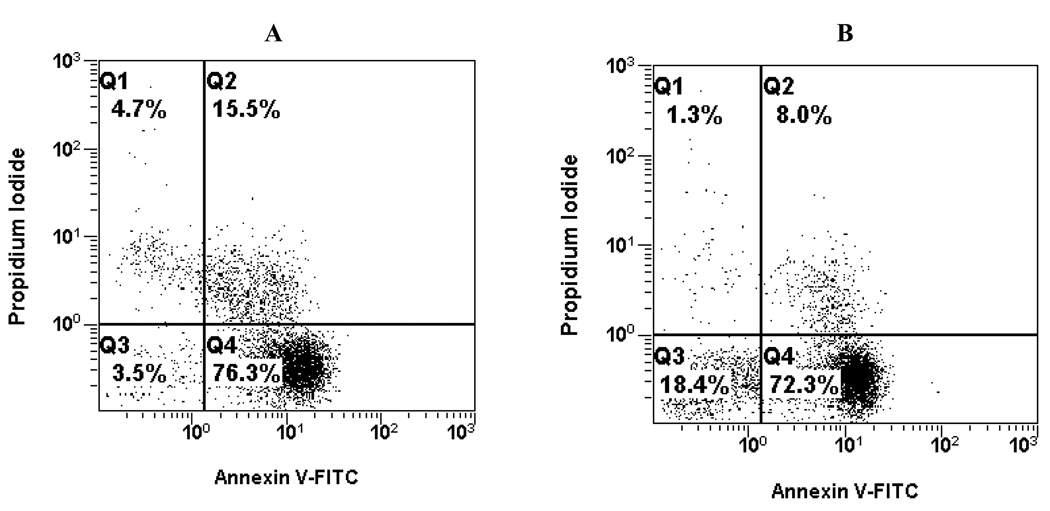

In order to gain some insight into the cell death type induced by complexes 1–6, we performed apoptosis assays on Jurkat cells. Cells sensing an inflicted aggression by a chemical compound undergo two major forms of death, necrosis or apoptosis, each with very distinct characteristics. Cell necrosis is a consequence of the inability to maintain intracellular homeostasis, initiated by an unbalance of ions and water influx, which is followed by cell swelling and rupture of intracellular organelles. That in turn leads to final loss of cell integrity by disruption of plasma membrane. When this phenomenon happens, the intracellular content, including lysosomal enzymes, are released into the cell surroundings, provoking a significant inflammatory response, frequently associated with extensive tissue damage in vivo. The necrosis process does not require metabolic energy, occurs at 4°C and can take place within seconds [80]. Apoptosis, on the other hand, is a genetically structured sequence of events in which the cell uses several metabolic pathways to actively destroy itself, with a slow gradual loss of plasma membrane integrity [81]. In contrast with necrosis, apoptosis is a much slower metabolic energy-dependent process, where RNA and protein synthesis is required; it does not occur at 4°C and takes from a few hours to a few days. In a human, about 100,000 cells are produced every second by mitosis, and a similar number die by apoptosis [82]. The removal of these dying cells takes place through noninflammatory phagocytosis, without damaging neighboring cells or tissue. Apoptosis is irreversible and its progression culminates in cell death, which is manifested by disruption of membrane integrity. In early stages of apoptosis, one of the significant biochemical features is loss of plasma membrane phospholipid asymmetry, due to translocation of phosphatidylserine (PS) from the cytoplasmic to the extracellular side. By employing Annexin V (FITC-conjugated), a molecule with specific binding to PS, it is possible to quantify the number of cells in this stage of apoptosis. Once programmed cell death is initiated, it will eventually result in permeabilization of the cell membrane allowing PI to stain double strand nucleic acids. Both cellular staining reagents are commonly used to discern between apoptotic and necrotic cell death mechanisms. Fig. 5 shows the data for the apoptosis-inducing effect on Jurkat cells of two representative examples: the N-bonded CQ complex 4 and the η6-bonded CQDP complex 5. Each histogram is divided in four quadrants; the left top quadrant shows necrotic cells that lost their membrane integrity and are permeable to PI, without Annexin V-FITC signal. The right top quadrant shows cells with compromised plasma membrane, permeable to PI, and stained with Annexin V-FITC, which indicates late apoptosis while the right bottom quadrant- represents cells binding to Annexin V-FITC, indicative of early apoptosis. The left bottom quadrant shows live cells that have intact membranes and therefore are not detected by either reagent. It is clear that both complexes mainly induce apoptosis while necrosis is not an important path of cell death for either complex. Similar studies were also performed with compounds 1, 2, 3 and 6. Fig. 6 summarizes the data, which indicate preferential induction of apoptosis in Jurkat cells when incubated with 100 µM concentrations of complexes 1–6.

Fig. 5.

Representative histograms from apoptosis assay on Jurkat cells induced by complex 4 (A) and complex 5 (B); both tested at 100 µM and measured by using two-color flow cytometry.

Fig. 6.

Mechanism of cell death (Apoptosis/Necrosis) of Jurkat cells provoked by 100 µM ruthenium compounds measured by using two-color flow cytometry, after 16 h of incubation time. Complexes 1, 2, 5 and 6 were dissolved in saline physiological solution (0.9% NaCl), whereas complexes 3 and 4 were dissolved in DMSO. Graph bars represent the average and standard deviation of cytotoxicity percentage from triplicates (see Experimental section for details).

3.3. Cytotoxicity of Ru-CQ complexes toward normal mammalian cells

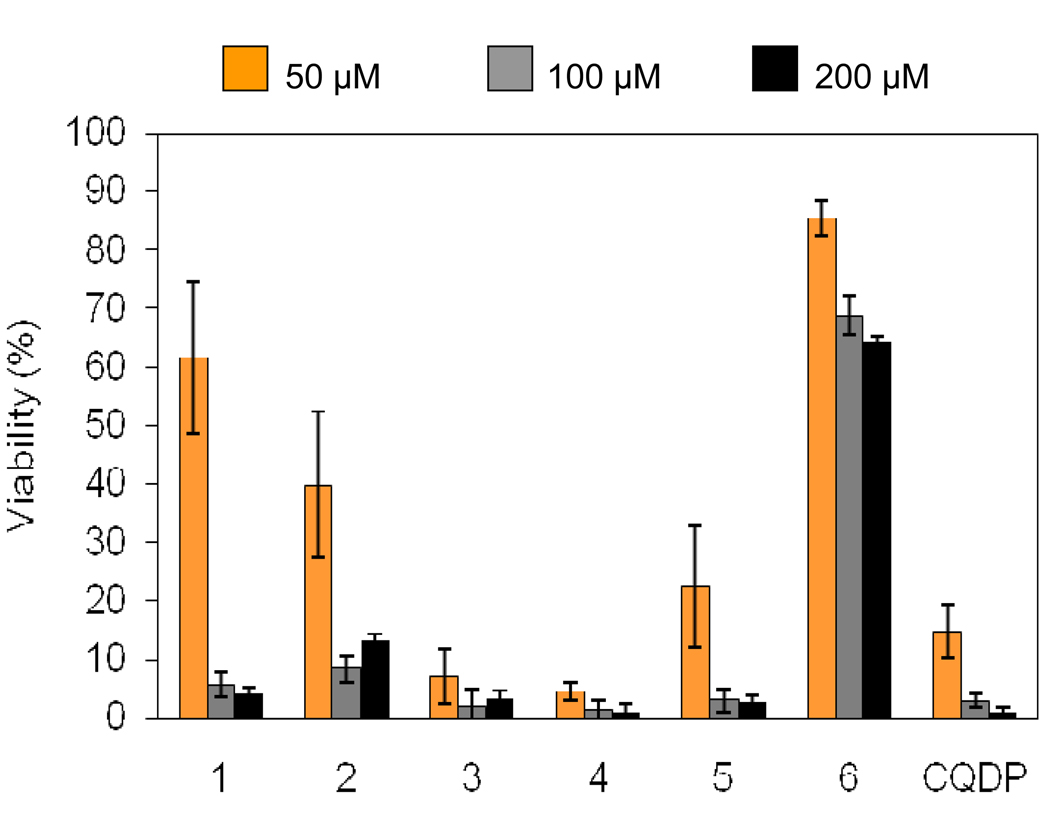

For any new compounds displaying biological activity, it is crucial to establish whether they also produce undesirable toxic effects that may limit their therapeutic potential. In order to probe this important feature, we studied the effect of treating two types of normal cells with the Ru-CQ complexes 1–5, in direct comparison with CQDP and with the reference compound 6. The results of a toxicity assay performed by flow cytometry on normal splenic cells freshly extracted from a mouse (C57B6), normalized against untreated controls, are shown in Fig. 10. The most important conclusions derived from these experiments are: (i) Complexes 1, 2, 3 and 5, display a level of toxicity to normal cells that is comparable to or lower than that of CQDP, a non-toxic antimalarial drug that has been widely used by humans throughout the world for decades. Our data thus indicate that binding CQ to ruthenium does not increase and can actually decrease the toxicity of this common drug against normal cells. (ii) The reference complex 6, which has a structure similar to those of our complexes but without CQ, is much less toxic than CQDP or our Ru-CQ complexes against the two normal cell lines tested in this work.

In a second set of experiments, an MTS assay of cell viability was carried out on the human foreskin fibroblast Hs27 cell line. This adherent cell line could not be analyzed by cytometry due to the difficulties in detaching them from plates without destroying the majority of the cells. The MTS assay relies on the ability of the MTS tetrazolium compound to be bioreduced by cells into a colored formazan product that is soluble in tissue culture medium [83]. This conversion is presumably accomplished by NADPH or NADH produced by dehydrogenase enzymes in metabolically active cells [84] and is dramatically disrupted in dying cells. Therefore, the quantity of formazan product, as measured by the absorbance at 490 nm, is directly proportional to the number of living cells in culture. The results for the MTS experiment on the Hs27 cells are shown in Fig. 8. It is important to highlight that as a consequence of the intrinsic characteristics of the MTS experiment and due to the high concentrations necessary to test the toxicity of the drugs (see details in Experimental section), the cell viability observed is, in general, low for all compounds. However, it is clear that a similar trend to that observed on mouse splenocytes emerges for the human foreskin fibroblast cells: (i) All ruthenium-CQ complexes are equally or less toxic than chloroquine; and (ii) the reference complex 6 displays a remarkably low toxicity.

Fig. 8.

Normalized results of the effect of ruthenium compounds on the viability of Hs27 cells after 20 h of incubation via the MTS viability assay. Complexes 1, 2, 5 and 6 were dissolved in saline physiological solution (0.9% NaCl), whereas complexes 3 and 4 were dissolved in DMSO. The percentage of cell viability is expressed as percentage of the absorbance as compared with cells that were treated with only physiological saline solution or DMSO. Bars represent the standard deviation of the mean of triplicate experiments.

These observations indicate that our Ru-CQ complexes 1–5 can be considered of low toxicity and that any residual toxicity is due to the presence of the standard drug chloroquine, and not of ruthenium, lending further support to the use of this metal as a basis for discovering new highly active, non-toxic drugs.

4. Conclusion

We have demonstrated that the arene-Ru-CQ complexes 1–5 interact with DNA to a comparable extent to that of chloroquine and in analogous intercalative manner, with no evidence for any direct contribution of the metal and/or the ancillary ligands. Complexes 1–5 were also found to display cytotoxicty toward Jurkat and SUP-T1 cancer cells, with induction of apoptosis as the main path for cell death. Under our assay conditions, complexes 1–5 were more active against both cell lines than a reference complex 6 not containing chloroquine. Despite the similarities in the DNA binding behavior of complexes 1–5 with those of CQ, the antitumor properties of the ruthenium drugs towards SUP-T1 and Jurkat cells are not in good correlation with those of CQ, indicating that DNA is not the principal target in the mechanism of cytotoxicity of these compounds. Importantly, the Ru-CQ complexes were found to be generally less toxic than the standard antimalarial drug CQDP toward normal mouse splenocytes and human foreskin fibroblasts and therefore this type of compound shows promise for drug development purposes.

Supplementary Material

Fig. 7.

Normalized data of toxicity on mouse splenocytes provoked by 10, 50 and 100 µM Ruthenium compounds measured by using two-color flow cytometry, after 20 h of incubation time. Complexes 1, 2, 5 and 6 were dissolved in saline physiological solution (0.9% NaCl), whereas complexes 3 and 4 were dissolved in DMSO. Graph bars represent the average and standard deviation of the mean cytotoxicity percentage from triplicates (see Experimental section for more details).

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the NIH through grant 1S06GM 076168-04 (to R. A. S.-D.) is gratefully acknowledged. We thank the staff of the Cell Culture and High Throughput Screening (HTS) Core Facility of UTEP for services and facilities provided. This core facility is supported by grant 5G12RR008124 to the Border Biomedical Research Center (BBRC), granted to the University of Texas at El Paso from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) of the NIH. We also thank Dr. Javier Suárez for assistance with electrophoresis experiments.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following information (Fig. S1–Fig. S3) are available as Supplementary materials.

Fig. S1. Spectrophotometric titration of complex 1 with CT DNA in 5 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaClO4 buffer, pH=7.39. Inset: Scatchard plot of data at 343 nm used to calculate values of Kb1 and Kb2

Fig. S2. Fluorimetric titration of complex 4 with CT DNA in 5 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaClO4 buffer, pH=7.39. Inset: Scatchard plot of data at 380 nm used to calculate values of Kb1 and Kb2.

Fig. S3. Spectrophotometric data of complex 6 incubated with 1–4 equivalents of CT DNA in 5 mM Tris/HCl, 50 mM NaClO4 buffer, pH=7.39 for 24h at 37°C.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Alberto Martínez, Chemistry Department, Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210.

Chandima S.K. Rajapakse, Chemistry Department, Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210

Armando Varela-Ramírez, Department of Biological Sciences, Biosciences Research Building, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 West University Ave., El Paso, TX 79968.

Carolina Lema, Department of Biological Sciences, Biosciences Research Building, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 West University Ave., El Paso, TX 79968.

Renato J. Aguilera, Department of Biological Sciences, Biosciences Research Building, University of Texas at El Paso, 500 West University Ave., El Paso, TX 79968

Roberto A. Sánchez-Delgado, Chemistry Department, Brooklyn College and The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 2900 Bedford Avenue, Brooklyn, NY 11210.

References

- 1.Boulikas T, Vougiouka M. Oncol. Rep. 2003;10:1663–1682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasini A, Zunino F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1987;26:615–624. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martínez A, Lorenzo J, Prieto MJ, de Llorens R, Font-Bardia M, Solans X, Avilés FX, Moreno V. ChemBioChem. 2005;6:2068–2077. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farrell N, Ha TTB, Souchard JP, Wimmer FL, Cros S, Johnson NP. J. Med. Chem. 1989;32:2240–2241. doi: 10.1021/jm00130a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pérez JM, Fuertes MA, Alonso C, Navarro-Ranninger C. Crit. Rev. Oncol./Hematol. 2000;35:109–120. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martínez A, Lorenzo J, Prieto MJ, Font-Bardia M, Solans X, Avilés FX, Moreno V. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007;15:969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vouillamoz-Lorenz S, Buclin T, Lejeune F, Bauer J, Leyvraz S, Decosterd LA. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:2757–2765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson A, Qu Y, van Houten B, Farrell N. Nucl. Ac. Res. 1992;20:1697–1703. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.7.1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kasparkova J, Zehnulova J, Farrell N, Brabec V. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:48076–48086. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zehnulova J, Kasparkova J, Farrell N, Brabec V. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:22191–22199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103118200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allardyce CS, Dyson PJ. Platinum Met. Rev. 2001;45:62–69. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Timerbaev AR, Hartinger CG, Aleksenko SS, Keppler BK. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2224–2248. doi: 10.1021/cr040704h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rademaker-Lakhai JM, Van Den Bongard D, Pluim D, Beijnen JH, Schellens JHM. Clin. Cancer Res. 2004;10:3717–3727. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sava G, Bergamo A, Zorzet S, Gava B, Casarsa C, Cocchietto M, Furlani A, Scarcia V, Serli B, Iengo B, Alessio E, Mestroni G. Eur. J. Cancer. 2002;38:427–435. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergamo A, Gagliardi R, Scarcia V, Furlani A, Alessio E, Mestroni G, Sava G. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1999;289:559–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sava G, Capozzi I, Clerici K, Gagliardi G, Alessio E, Mestroni G. Clin. Exp. Metastasis. 1998;16:371–379. doi: 10.1023/a:1006521715400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morbidelli L, Donnini S, Filippi S, Messori L, Piccioli F, Orioli P, Sava G, Ziche M. Br. J. Cancer. 2003;88:1484–1491. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bratsos I, Jedner S, Gianferrara T, Alessio E. Chimia. 2007;61:692–697. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartinger CG, Jakupec MA, Zorbas-Seifried S, Groessl M, Egger A, Berger W, Zorbas H, Dyson PJ, Keppler BK. Chem. Biodiversity. 2008;5:2140–2155. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garzon FT, Berger MR, Keppler BK, Schmaehl D. Cancer Chemoth. Pharmacol. 1987;19:347–349. doi: 10.1007/BF00261487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berger MR, Garzon FT, Keppler BK, Schmaehl D. Anticancer Res. 1989;9:761–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Seelig MH, Berger MR, Keppler BK. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 1992;118:195–200. doi: 10.1007/BF01410134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kapitza S, Pongratz M, Jakupec M, Heffeter P, Berger W, Lackinger L, Keppler BK, Marian B. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2005;131:101–110. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0617-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jakupec MA, Galanski M, Arion VB, Hartinger CG, Keppler BK. Dalton Trans. 2008:183–194. doi: 10.1039/b712656p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christodoulou CV, Eliopoulos A, Young A, Hodgkins L, Ferry DR, Kerr DJ. Br. J. Cancer. 1998;77:2088–2097. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris RE, Aird RE, Murdoch PdS, Chen H, Cummings J, Hughes ND, Parsons S, Parkin A, Boyd G, Jodrell D, Sadler PJ. J. Med. Chem. 2001;44:3616–3621. doi: 10.1021/jm010051m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aird RE, Cummings J, Muir M, Morris RE, Chen H, Sadler PJ. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;86:1652–1657. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dougan SJ, Melchart M, Habtermariam A, Parsons S, Sadler PJ. Inorg. Chem. 2006;45:10882–10894. doi: 10.1021/ic061460h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang F, Bella J, Parkinson JA, Sadler PJ. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2005;10:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s00775-004-0621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen H, Parkinson JA, Novakova O, Bella J, Wang F, Dawson A, Gould R, Parsons S, Brabec V, Sadler PJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100:14623–14628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2434016100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marini V, Christofis P, Novakova O, Kasparkova J, Farrell N, Brabec V. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:5819–5828. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scolaro C, Bergamo A, Brescacin L, Delfino R, Cocchietto M, Laurenczy G, Geldbach TJ, Sava G, Dyson PJ. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:4161–4171. doi: 10.1021/jm050015d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sánchez-Delgado RA, Anzellotti A, Suárez L. Metal Ions and their Complexes in Medication. In: Sigel H, Sigel A, editors. Metal Ions in Biological Systems. Vol. 41. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navarro M, Lehman T, Cisneros EJ, Fuentes A, Sánchez-Delgado RA, Silva P, Urbina JA. Polyhedron. 2000;19:2319–2325. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sánchez-Delgado RA, Lazardi K, Rincón L, Urbina JA, Hubert AJ, Noels AN. J. Med. Chem. 1993;36:2041–2043. doi: 10.1021/jm00066a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sánchez-Delgado RA, Navarro M, Lazardi K, Atencio R, Capparelli M, Vargas F, Urbina JA, Bouillez A, Noels AF, Masi D. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1998;275–276:528–540. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strasberg Rieber M, Anzelloti A, Sánchez-Delgado RA, Rieber M. Int. J. Cancer. 2004;112:376–384. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sachs J, Malaney P. Nature. 2002;425:680–685. doi: 10.1038/415680a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenthal PhJ., editor. Antimalarial Chemotherapy: Mechanism of Action, Resistance and New Directions in Drug Discovery. New Jersey: Humana Press; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sánchez-Delgado RA, Navarro M, Pérez H, Urbina JA. J. Med. Chem. 1996;39:1095–1099. doi: 10.1021/jm950729w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Martínez A, Rajapakse CSK, Naoulou B, Kopkalli Y, Davenport L, Sánchez-Delgado RA. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:703–712. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0356-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rajapakse CSK, Martínez A, Naoulou B, Jarzecki AA, Suárez L, Deregnaucourt C, Sinou V, Schrével J, Musi E, Ambrosini G, Schwartz GK, Sánchez-Delgado RA. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:1122–1131. doi: 10.1021/ic802220w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martínez A, Rajapakse CSK, Jalloh D, Dautriche C, Sánchez-Delgado RA. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2009;14:863–871. doi: 10.1007/s00775-009-0498-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Solomon VR, Lee H. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2009;625:220–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maclean KH, Dorsey FC, Cleveland JL, Kastan MB. J. Clin. InVest. 2008;118:79–88. doi: 10.1172/JCI33700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dang CV. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:15–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI34503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kastan MB, Bakkenist CJ. Prophylactic treatment of cancer with chloroquine compounds. 20050032834. U.S. Patent Appl. Publ. 2005 February 10;

- 47.Zamora JM, Pearce HL, Beck WT. Mol. Pharmacol. 1988;33:454–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sorensen M, Sehested M, Jensen PB. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1997;54:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(97)80318-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Press OW, DeSantes K, Anderson SK, Geissler F. Cancer Res. 1990;50:1243–1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Irvin JL, Irvin EM, Parker FS. Science. 1949;110:426–428. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2860.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kurnick NB, Radcliffe IE. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 1962;60:669–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cohen SN, Yielding KL. J. Biol. Chem. 1965;240:3123–3131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cohen SN, Yielding KL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1965;54:521–527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.54.2.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Brien RL, Olenick JG, Hahn FE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1966;55:1511–1517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.55.6.1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hahn FE, O’Brien RL, Ciak J, Allison JL, Olenick JG. Milit. Med. 1966;131:1071–1089. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Allison JL, O’Brien RL, Hahn FE. Science. 1965;149:1111–1113. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3688.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Scaria PV, Craig JC, Shafer RH. Biopolymers. 1993;33:887–895. doi: 10.1002/bip.360330604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yielding KL, Blodgett LW, Sternglanz H, Gaudin D. Prog. Mol. Subcell. Biochem. 1971;2:69–90. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geroghiou S. Photochem. Photobiol. 1977;26:59–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1977.tb07450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Crabtree RH, Pearman AJ. J. Organomet. Chem. 1977;141:325–330. [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGhee JD, Von Hippel PH. J. Mol. Biol. 1974;86:469–489. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(74)90031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wei C, Jia G, Yuan J, Feng Z, Li C. Biochemistry. 2006;45:6681–6691. doi: 10.1021/bi052356z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Boyer R. Biochemistry Laboratory: modern theory and techniques. Reading: Benjamin Cummings; 2006. pp. 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cusumano M, Di Pietro ML, Giannetto A. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1754–1758. doi: 10.1021/ic9809759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Satyanarayana S, Dabroviak JC, Chaires J. Biochemistry. 1992;31:9319–9324. doi: 10.1021/bi00154a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Smith SD, Shatsky M, Cohen PS, Warnke R, Link MP, Glader BE. Cancer Res. 1984;44:5657–5670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elie BT, Levine C, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Varela-Ramirez A, Aguilera RJ, Ovalle R, Contel M. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009:3421–3430. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200900279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Coligan JE, Kruisbeek AM, Margulies DH, Shevach EM, Strober W, editors. Current protocols in immunology. New York: John Wiley; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyoshi N, Oubrahim H, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. PNAS. 2006;103(6):1727–1731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510346103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cardonna JP, Lippard SJ, Gait MJ, Singh M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982:5793–5795. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vacca A, Bruno M, Boccarelli A, Coluccia M, Ribatti D, Bergamo A, Garbisa S, Sartor L, Sava G. Br. J. Cancer. 2002;86:993–998. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kelman AD, Clarke MJ, Edmons HJ, Peresie HJ. J. Clin. Hematol. Oncol. 1977;7:274–288. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mestroni G, Alessio E, Calligras M, Attia WM, Quadrifoglio F, Cauci S, Sava G, Zorzet S, Pacor S, Monti-Bragadin C, Tamaro M, Dolzani L. Prog. Clin. Biochem. Med. 1989;10:71–87. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gallori E, Vettori C, Alessio E, González-Vilchez F, Vilaplana R, Orioli P, Casini A, Messori L. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2000;376(1):156–162. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chen H, Parkinson JA, Morris RE, Sadler PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:173–186. doi: 10.1021/ja027719m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Novakova O, Chen H, Vrana O, Rodger A, Sadler PJ, Bravec V. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11544–115554. doi: 10.1021/bi034933u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Habtemariam A, Melchart M, Fernández R, Parsons S, Oswald IDH, Parkin A, Fabbiani FPA, Davidson JE, Dawson A, Aird RE, Jodrell DI, Sadler PJ. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6858–6868. doi: 10.1021/jm060596m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fox K. Drug-DNA Interact. Protocols. 1997;90:95–106. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sherman SE, Lippard SJ. Chem. Rev. 1987;87:1153–1181. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Collins JA, Schandl CA, Young KK, Vesely J, Willingham MC. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1997;45:923–934. doi: 10.1177/002215549704500702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Br. J. Cancer. 1972;26(4):239–257. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vaux DL, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell. 1999;96(2):245–254. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80564-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barltrop JA, Owen TC, Cory AH, Cory JG. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1991;1:611–614. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Berridge MV, Tan AS. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993;303:474–482. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.