Abstract

Several recent studies have examined the connection between religion and medical service utilization. This relationship is complicated because religiosity may be associated with beliefs that either promote or hinder medical helpseeking. The current study uses structural equation modeling to examine the relationship between religion and fertility-related helpseeking using a probability sample of 2,183 infertile women in the United States. We found that although religiosity is not directly associated with helpseeking for infertility, it is indirectly associated through mediating variables that operate in opposing directions. More specifically, religiosity is associated with greater belief in the importance of motherhood, which in turn is associated with increased likelihood of helpseeking. Religiosity is also associated with greater ethical concerns about infertility treatment, which are associated with decreased likelihood of helpseeking. Additionally, the relationships are not linear throughout the helpseeking process. Thus, the influence of religiosity on infertility helpseeking is indirect and complex. These findings support the growing consensus that religiously-based behaviours and beliefs are associated with levels of health service utilization.

Keywords: religiosity, motherhood, assisted reproductive technology, medical helpseeking, ethics, USA, utilization, infertility

Decades of research reveal that religiosity generally has positive effects on both mental and physical health (Ellison & Levin, 1998; Koenig & Larson, 2001; Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001). Researchers are paying increasing attention to the connection between religiosity and medical service utilization as a possible source of the relationship between religion and health (Benjamins, 2006; Hill, Ellison, Burdette, & Musick, 2006; King,& Pearson, 2003). This relationship is complex. First, the effect of religion on service utilization varies by specific outcome. Second, the impact of religion can work in contradictory directions; different religious beliefs could promote or hinder helpseeking. Third, the effect of religion may not be linear or identical at all stages of the helpseeking process. Finally, it remains unclear which dimensions of religion influence service utilization. In this article, we explore the influence of religion on infertility helpseeking for women who meet the medical definition of infertility -- twelve months of unprotected intercourse without conception.

Background

Religion and Service Utilization

Religion has been implicated in reduced mortality, decreased incidence of cardiovascular disease, expedited recovery from illness, and improved mental health (see e.g.; Chatters, 2000; Contrada, Goyal, & Cather, 2004; Hackney & Sanders 2003; Powell, Shahabi, & Thoreson, 2003). The proposed pathways through which religion influences health include encouraging healthy lifestyle habits, providing social support, bolstering self-esteem and self-efficacy, and providing a coherent structure for interpreting life events (George, Ellison, & Larson, 2002). Differential health care utilization is one possible explanation for the link between religiosity and health. The literature review that follows focuses on religion and service utilization and is not intended to provide a complete review of the extensive literature on religion and health in general.

Studies show that religion is related both to increased and decreased service utilization, depending on the type of service and the population examined (see e.g. Benjamins & Brown, 2003; Benjamins et al., 2006; King, & Pearson, 2003; McCullough, Larson, Hoyt, Koenig, & Thoreson, 2000). In a literature review on religion and health service utilization, Schiller and Levin (1988) found that 24 of 31 studies showed strong religious effects, but they caution that religion is not a unitary phenomenon; religious affiliation, religious salience, denomination, and religious attendance may not have similar impacts on service utilization. Most studies have focused on attendance and salience, and many are quite dated.

In many studies of religion and health services utilization, need for services is a confounding factor. If, for example, religion is negatively associated with doctor visits in a cross-sectional study, does that mean that religion leads to lower service use, or does it simply mean that religious people are healthier and therefore require fewer doctor visits? Focusing on preventive health services may be a partial solution to this issue. Studies investigating religion and the use of preventive health services show some positive associations. More frequent religious attendance is associated with increased likelihood of blood pressure screening (Benjamins, 2007; Felix-Aaron, Levine, & Burstein, 2003), diabetes screening (Benjamins, 2007), cancer screening (Benjamins, 2006); cholesterol screening (Benjamins, 2005, 2006), and regular checkups (Hill et al., 2006). Results, however, are inconsistent. For example, other studies fail to find associations between frequency of attendance and cholesterol screening (Benjamins, 2007), cancer screening (Fox, Pitkin, Paul, Carson, & Duan, 1998), and regular checkups (Ellison, Lee, Benjamins, Kraus, Ryan, and Marcum, 2008).

Studies of the impact of religious salience, or the importance of religion to an individual, reveal similar inconsistencies. Religious salience is positively related to blood pressure screening (Benjamins 2007), cholesterol screening (Benjamins, 2007; Benjamins & Brown, 2004), cancer screening (Benjamins, 2006; Benjamins & Brown, 2004; Benjamins et al., 2006), and getting flu shots (Benjamins & Brown, 2004). Yet, a study of older American women found religious salience was not associated with Pap smears or mammograms (Benjamins, 2006), and another study found no association between salience and diabetes screening among older Mexican adults (Benjamins 2007). Thus, religious salience is often, but not always, associated with preventive service use.

Although a majority of studies indicate that the relationship between religion and health behaviors and outcomes is positive, there is also evidence of a negative association. Religion can influence the types of medical treatment perceived as acceptable: the belief that certain treatments are not supported by religious doctrine may lead to treatment refusal or discontinuation. Some religions forbid or strongly discourage using specific medical devices or procedures such as contraceptives, vaccinations, and blood transfusions (Asser & Swan, 1998; Muromoto, 1999). Increased religiosity could also be associated with lower service utilization because of higher fatalism or external locus of control among those who are more religious (Nagel & Sgoutas-Emch, 2007). Individuals with lower personal efficacy and control should be less proactive than those with higher personal efficacy or control (Rodin, 1990; Zarit, Pearlin, & Schaie 2002). These sentiments could lead to an underutilization of health care services, such as those for cancer screening (Straughan & Seow, 1998, 2000). Other researchers, however, have argued that persons with a strong perception of God’s control may enjoy more favorable outcomes, especially compared with their counterparts who attribute control to non-religious external forces (Holt, Clark, Kreuter, & Rubio, 2003; Holt, Lukwago, & Kreuter, 2003; Johnson, Elbert-Avila, & Tulsky, 2005; Schieman, Pudrovska, Pearlin, & Ellison, 2006).

The inconsistencies in the prior literature regarding religion and service utilization are not well understood. No clear patterns emerge from the previous studies, with the possible exception that the studies reporting positive associations between religion and preventive service use tend to consist of samples of older people (e.g. Benjamins, 2006; Benjamins, 2007; Benjamins & Brown, 2004). Although we presume that the particular outcome under study should impact the relationship, we see no clear conclusion regarding the association between religion and utilization by type of service studied. Therefore, it is important that future studies include possible mechanisms that can better explain precisely how religion influences utilization.

More information about possible mechanisms is also helpful to better understand the influences that various dimensions of religion, such as religious attendance and salience, could have on service utilization. There are many theoretical reasons why these dimensions would operate differently. Measures of public religious participation, such as attendance, reflect social benefits provided to individuals through involvement with a religious organization. These may include greater access to services and health information, and increased motivation to maintain a healthy lifestyle. Individuals who frequently attend religious services have larger social networks, more frequent social interactions, and receive more frequent (and more types of) instrumental and socioemotional assistance than individuals who attend less often or never (Bradley 1995). Research on the effects of social relationships on a wide range of health behaviors supports the health enhancing benefits of these types of social interactions (Lewis and Rook, 1999). Religious congregations can also provide normative guidance for individual members, which may increase positive health behaviors (Hoffmann and Bahr 2005). Furthermore, religious attendance may also have more direct influences on preventive health care utilization. For example, some churches offer activities or information about health-related topics that may lead (directly or indirectly) to a greater use of health care services by members exposed to these resources. This direct role may help to explain some of the associations found for preventive health services, but is expected to be less relevant to fertility-related services.

The potential explanations for an association between aspects of religion and health care use are less clear. Participating in private religious activities (e.g. prayer or reading religious texts), holding religious beliefs, and considering religion to be important in one’s life may all impact service utilization through various pathways. Although limited, most research on this topic involves the influence of religious beliefs in encouraging positive health behaviors. Most of the findings, however, do not support such a relationship. For example, among Presbyterians, there was no support for the mediating role of the belief in a responsibility to God to maintain one’s health and a belief in the connection between spiritual and physical health (Benjamins, Trinitapoli, and Ellison, 2006). Another study found that beliefs in the sanctity of the body are actually associated with a decreased likelihood of having a routine health exam in the past year (Ellison et al., 2008). In contrast, Mahoney and associates (2005) found that sanctification of the body predicted positive health practices in college students. The influence of prayer and possible explanations for the impact of salience are also understudied; therefore there needs to be more work in this area.

Thus, although religion is associated with service utilization, it is difficult to succinctly characterize the relationship. Previous studies show generally positive, though not consistent, associations with utilization that cannot be explained by differing samples or outcomes. It is also not clear what characteristic or quality of religion is related to helpseeking. The impact of religion may be due to selection, better health of religious individuals, social support and capital from religious participation, specific health initiatives undertaken by certain religious organizations, or content of religious beliefs or specific theologies (Ellison et al., 2008). We address these limitations by extending the literature to another health service outcome of interest; by examining two distinct aspects of religion; and by investigating the role of potential mediators.

Infertility and Helpseeking

We assess the relationship between religiosity and health behavior via infertility helpseeking. The prevalence of infertility worldwide was recently estimated at 9% (Boivin, Bunting, Collins, & Nygren, 2007). According to the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), 15% of U.S. women reported “impaired fecundity” in 2002 (Chandra, Martinez, Mosher, Abma, & Jones, 2005), but lifetime prevalence rates are considerably higher. A probability-based sample of women in 12 Midwestern states found that 38% of women aged 25 to 45 reported infertility at some point in their lives (White, McQuillan, Greil, & Johnson, 2006).

Studies describe infertility as a devastating experience that brings feelings of emotional distress and a high level of commitment to treatment-seeking, especially among women (Becker, 2000; Greil, 1991; Sandelowski, 1993). Given this characterization, it is surprising that less than half of infertile women seek medical treatment (Boivin, Bunting, Nygren, & Collins, 2007; Chandra & Stephen, 1998). Of the infertile women studied in Wave 1 of the National Survey of Fertility Barriers (NSFB) (the dataset we use for this paper), 27% had visited a doctor concerning fertility problems, 21% more had gone on to have tests or treatment, and 3% had undergone in vitro fertilization (IVF) or other assisted reproductive technologies (ART) (Johnson & White, 2009).

Examining infertility help-seeking expands the study of religion and service utilization beyond health-related preventative behaviors. First, it is a condition with a high incidence but a relatively low treatment rate. In addition, many people do not seek help for infertility soon enough for treatment to be optimally effective. Second, infertility treatment is largely voluntary; it is rarely life-threatening and health professionals usually learn of it only when brought up by patients. It is a condition that need not be interpreted medically and for which many people do not, in fact, seek medical solutions. Finally, religion may be particularly salient for these types of decisions because religious traditions and beliefs are strongly connected to family and life course issues such as fertility.

Most religious traditions encourage child-bearing and emphasize the importance of family during services and other activities. Studies that find that higher religiosity is associated with lower acceptance of childlessness (Bulcroft & Teachman, 2004; Koropeckyj-Cox & Pendell, 2007) and higher fertility intentions (Hayford & Morgan, 2008). Research suggests that people with strong religious beliefs tend to be more traditional in lifestyle choices, gender ideology, and marriage and family patterns (Grasmick, Wilcox, & Bird, 1990; Jensen & Jensen, 1993, and this may encourage the pursuit of infertility treatment.

Importantly, many of the advances in reproductive technology are discouraged or prohibited by religious traditions. Religious officials are concerned with two main issues – the sanctity of the marital relationship and the sanctity of the embryo (for reviews, see Dutney, 2007; Schenker, 2005). For some denominations, such as Roman Catholicism, this results in opposition to the use of artificial insemination (including intra-uterine insemination (IUI) and in vitro fertilization (IVF)) (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, 1987). Protestantism, Judaism, and Islam have slightly fewer restrictions than Catholicism; these traditions generally approve of advanced reproductive technologies (ART), but they are against the use of donor gametes (Dutney, 2007). Perhaps for these reasons, religious individuals may choose to avoid such technologies and favor alternatives such as adoption. In fact, religious salience is associated with increased likelihood of seeking to adopt (Hollingsworth, 2000). Thus, the relationship between religion and infertility helpseeking is expected to be complex.

Finally, it is important to address factors relevant to infertility helpseeking. Women with primary infertility (no prior pregnancies) are more likely to seek help than are those with secondary infertility (Hirsch & Mosher, 1987; Schmidt & Munster, 1995). Greil and McQuillan (2004) and Jacob et al. (2007) showed the importance of considering pregnancy intentions at the time of the infertility episode. They categorized infertile women into two groups: “infertile with intent” (women who say they tried to conceive for at least 12 months without conception) and “infertile without intent” (women who report having had unprotected intercourse for a year or more without conception but who do not say that they were trying to conceive at the time). The infertile with intent are significantly more likely to seek treatment than the infertile without intent (White et al., 2006). Other factors associated with infertility helpseeking include wanting another child, higher income and education, and having private health insurance (Greil & McQuillan, 2004; Greil, McQuillan, Shreffler, Johnson, & Slauson-Blevins, 2009; White et al., 2006). Greil et al. (2009) found that Hispanic women were less likely to seek help even after a large array of other factors were controlled.

Statement of the Problem

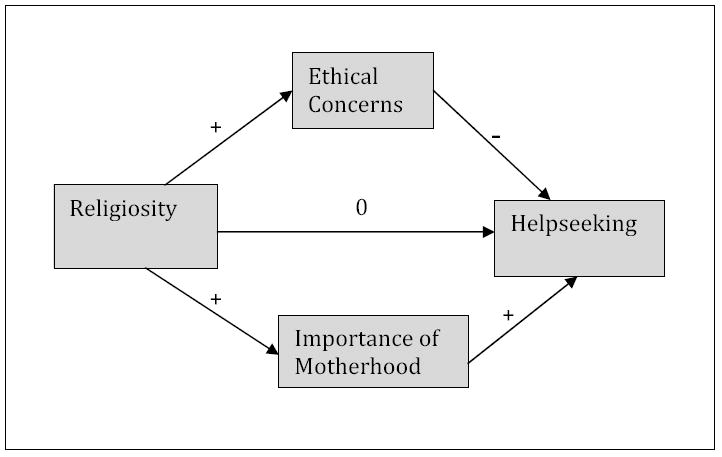

Our goal is to assess the influence of various aspects of religiosity on infertility helpseeking. There are reasons to expect that religiosity should impact infertility helpseeking. First, there is a generally positive association between religiosity and service utilization, previously discussed, that suggests religious women may be more likely to utilize health services. In addition, because many religions embrace pronatalist ideals, motherhood may be more important to more religious women; this should increase religious women’s likelihood of helpseeking if they experience fertility barriers. Certain religious beliefs, however, could also lead to fatalism. Religiosity may also increase ethical concerns about fertility treatment. We hypothesize that these two countervailing, mediating forces, importance of motherhood and ethical concern, will cancel each other out and that there will be no significant net effect of religiosity on infertility helpseeking. Figure 1 presents a schematic drawing of our basic theoretical model.

Figure 1.

Basic Theoretical Model.

Note: “0” indicates that no effect is anticipated.

Methodology

Sample

Our data come from the NSFB, a national random-digit-dialing telephone survey we designed to assess social and health factors related to reproductive choices and fertility for U.S. women. Between September 2004 and December 2005, we completed interviews with 4,712 women ages 25 to 45. We draw our data from 2,183 women who reported experiencing an infertility episode at some point in their lives. Although the NSFB also included interviews with a subsample of male partners, we did not include men in this analysis because it would have significantly reduced our sample size (n = 926) and analyses of the NSFB data have shown that male partners who responded to the survey represent a more select group of men (Johnson & White, 2009). For the purposes of this study, we were interested in the relationship between religion and help-seeking in a more representative group of women. Additionally, studies have shown that women are typically the more instrumental partner when a couple experiences infertility, taking responsibility for initiating help-seeking or treatment (Greil, 1991; Throsby & Gill, 2004).

Sampling procedures and selection criteria were used to ensure an adequate representation of women from racial/ethnic minority groups, women who have experienced infertility, and women who desire additional children. Ethics approval was provided by the University of Nebraska at Lincoln and the Pennsylvania State University Because the survey was long (potentially taking over 45 minutes to complete), we shortened it by randomly assigning participants to two-thirds of the items of each scale. This “planned missing” design provided a way to incorporate measures of all of the necessary theoretical concepts while minimizing respondent burden. This type of missing data fulfills the ‘missing completely at random’ (MCAR) assumption and does not bias results (Allison, 2002). We used the mean of available scale items in the analyses. The response rate for this sample is 53% for the screener and 37.2% overall. This response rate is typical for telephone surveys conducted in the last several years (McCarty, House, Harman, & Richards, 2006). Recent studies have shown that surveys with lower response rates are not necessarily more biased than higher response rate studies (Keeter, Dimock, Best, & Craighill, 2006). To assess the representativeness we compared it to the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG), a population-based survey with a response rate close to 90%, and found very similar responses to equivalent fertility-specific and demographic questions in the two surveys.

Concepts and Measures

Our main outcome is infertility helpseeking. Respondents were asked a series of questions about information-seeking, treatment-seeking, tests, and treatments related to infertility. From these, we constructed an ordinal variable with six values: (0) did not seek help (1) considered treatment; (2) talked to a doctor; (3) had tests; (4) received treatment; and (5) had ART. Anyone at a higher value has satisfied the conditions for all lower values. For example, anyone who has had tests has also talked to a doctor and considered treatment. Of the infertile women studied in Wave 1 of the NSFB, 63.4% reported not seeking help, 8.9% reported “considered only,” 7.0% saw a doctor only, 7.0% had tests but did not move on to treatment, 10.7% received conventional treatment only (such as artificial insemination or fertility drugs to stimulate ovulation), and 2.7% had some form of assisted reproductive technology (ART), involving manipulation of both egg and sperm outside of the body.

We used two main variables to capture religious involvement and belief: religiosity and religious attendance. Religiosity was measured by three questions: 1) “About how often do you pray,” 2) “How close do you feel to God most of the time,” and 3) “In general, how much would you say your religious beliefs influence your daily life?” The items formed a single factor with high reliability (α = .77). This was treated as a latent variable in our model. Religious attendance was assessed via a single question: “How often do you attend religious services?” Possible responses included: “never,” “less than once a year,” “about once or twice a year,” “about once a month,” “nearly every week,” “every week,” and “several times a week.” The Pearson’s r between religiosity and attendance is .274. We did not include a measure of religious denomination because a sufficiently detailed measure was not available to us.

Mediating variables

Our focal mediating variables were importance of motherhood and attitudes toward the ethics of ART. Both were treated as latent variables in our model. Importance of motherhood was constructed by averaging responses to five questions. Four items were measured using Likert scales (strongly agree to strongly disagree): 1) “Having children is important to my feeling complete as a woman,” 2) “I always thought I would be a parent,” 3) “I think my life will be or is more fulfilling with children,” and 4) “It is important for me to have children.” A fifth item was measured on a scale from very important to not important: “How important is each of the following in your life…raising children?” Higher scores indicate greater importance of motherhood. Factor analyses showed that these items formed a single factor that explained 64 % of the variance (α=.86). Attitudes toward the ethics of ART is a scale assessing the respondent’s concern with six instances of ART (alpha = .86): 1) insemination with husband’s sperm, 2) insemination with donor sperm, 3) in vitro fertilization, 4) use of donor eggs, 5) surrogate mothering, and 6) using a gestational carrier. Each item had three ordered response categories indicating no, some, or serious ethical problems.

Control Variables

A number of variables that have been shown to influence infertility helpseeking were included as controls in the analyses. Women who described themselves as trying to become pregnant at the time of their infertility episode were classified as infertile with intent, while women who did not report themselves as actively trying to become pregnant during their infertility episode were classified as infertile without intent. Respondents were classified as having primary infertility if they experienced a period of infertility before they had experienced any pregnancies. All other women were classified as having secondary infertility. Wants another child was coded 1 for those responding ‘yes’ to the question: “Would you, yourself, like to have (another) baby?” Age was measured in years. Due to people’s sensitivity to questions about income, family income was first constructed as an ordinal scale ranging from 1 (less than $5000 per year) to 12 ($100,000 or more). We then substituted the midpoint of each category for the category value in order to convert this into a continuous scale. Education was measured in years. Private health insurance status was assessed by the question, “Are you covered by private health insurance, by public health insurance such as Medicaid, or some other kind of health care plan or by no health insurance?” Respondents with private health insurance were coded as 1 while all other options were coded as 0. Public health insurance is appropriately classified with no insurance because infertility benefits are not covered by Medicaid in the U.S. (Bittler and Schmidt 2006). Dummy variables for race were constructed for Black, Hispanic, and Asian compared to non-Hispanic White women and women who listed their race as “other.” We collapsed the latter two because the small “other” group did not differ significantly from non-Hispanic White women with regard to the variables of interest.

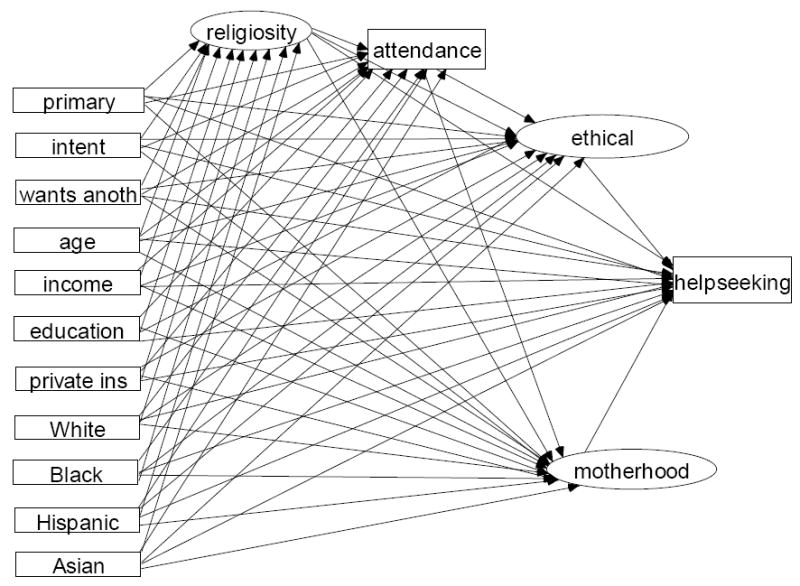

Method of Analysis

Figure 2 displays our full structural equation model. Our final dependent variable was infertility helpseeking. Religiosity was conceptualized as having indirect effects on helpseeking through religious attendance, ethical concerns, and importance of motherhood. Although we have hypothesized that religiosity would not have a direct effect on helpseeking, we retained the direct path in the model to test for this possibility. The ethics of ART and the importance of motherhood were included as latent variables with the items in each scale serving as the multiple indicators of the respective underlying constructs. All of the paths from the control variables to the focal variables in the model were left unconstrained in order to take into account the possible effects of the control variables on the focal variables.

Figure 2.

Elaborated SEM model.

We were restricted from using the common basic linear structural equation model both because our main outcome variable was ordinal and because we are interested in testing if the religiosity effects varied by treatment level. If the effects of the explanatory variables were the same at each level of helpseeking then an ordinal logistic regression model would be more parsimonious as only one coefficient for each variable would be needed. Ordinal logistic regression is appropriate only when the parallel lines assumption, also referred to as the proportional odds assumption, is met (Winship & Mare, 1984). This requires that the slopes predicting values of the dependent variable be parallel for every level of the dependent variable (Brant, 1990). The parallel lines assumption did not hold for our model so we treated helpseeking as a series of discreet stages rather than as a single ordinal variable. We followed the example of Williams (2006) and conducted five separate structural equation models with binary outcomes to estimate the effects of religiosity at each transition in the help-seeking process. All cases were included in each model; only the cut point was changed. For example, the first analysis included all women and compared those who did not seek help with all women at later stages (considered help-seeking and beyond), while the second analysis also includes all women but uses whether women actually saw a doctor as the cut point. The analysis was done with the full information maximum likelihood estimation method which uses all cases even if some variables have missing data.

Results

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics by each stage of helpseeking. For ease of presentation, continuous variables in our final model have been broken into categories. Women who have progressed to different stages of the helpseeking process appear to differ across all of the independent variables in the model. Thus, there is good reason to include these variables in an analysis of the relationship between religiosity, religious attendance, ethical concerns, importance of motherhood, and helpseeking.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics by categories of helpseeking.

| No help 1383 % | Considered 195 % | Talked to doc 153 % | Tests 159 % | Treatment 234 % | ART 59 % | p. | N for row 2183 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religiosity | ||||||||

| Lowest quartile | 21.7 | 28.2 | 28.8 | 33.3 | 19.2 | 32.2 | * | 516 |

| Second quartile | 31.4 | 26.7 | 24.8 | 23.9 | 28.6 | 23.7 | n.s. | 643 |

| Third quartile | 20.9 | 20.5 | 20.9 | 21.4 | 25.2 | 22.0 | n.s. | 467 |

| Highest quartile | 26.0 | 24.6 | 25.5 | 21.4 | 26.9 | 22.0 | n.s. | 557 |

| Religious attendance | ||||||||

| Lowest third | 36.3 | 35.7 | 33.9 | 36.5 | 33.3 | 38.8 | n.s. | 782 |

| Middle third | 35.9 | 37.9 | 40.1 | 36.8 | 29.8 | 34.2 | n.s. | 780 |

| Highest third | 27.8 | 26.3 | 26.0 | 27.0 | 36.8 | 27.1 | * | 621 |

| Primary infertility | 17.7 | 40.5 | 39.2 | 58.5 | 65.1 | 76.3 | *** | 674 |

| Infertile with intent | 28.0 | 72.2 | 72.4 | 85.5 | 94.4 | 96.7 | *** | 1053 |

| Wants a(nother) child | 34.3 | 60.8 | 52.3 | 57.6 | 46.5 | 59.3 | *** | 908 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 25 to 29 | 20.3 | 27.3 | 18.3 | 11.4 | 11.1 | 5.1 | *** | 409 |

| 30 to 35 | 25.7 | 26.8 | 28.1 | 35.4 | 24.8 | 23.7 | n.s. | 579 |

| 36 to 40 | 23.6 | 26.3 | 29.4 | 22.8 | 28.2 | 37.3 | n.s. | 547 |

| 41 to 45 | 30.3 | 19.6 | 24.2 | 30.4 | 35.9 | 33.9 | ** | 647 |

| Income | ||||||||

| 40K and greater | 49.7 | 53.3 | 56.6 | 53.3 | 69.2 | 87.5 | *** | 1176 |

| Below 40K | 50.3 | 46.7 | 43.4 | 36.7 | 30.8 | 12.5 | *** | 991 |

| Education | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | ||

| Less than H.S. | 18.6 | 18.5 | 15.1 | 12.6 | 11.2 | 3.4 | ** | 365 |

| High school | 32.4 | 25.1 | 37.5 | 22.0 | 28.0 | 16.9 | ** | 665 |

| Some college | 29.9 | 29.7 | 28.9 | 29.6 | 30.6 | 22.0 | ** | 647 |

| College degree or more | 19.1 | 26.7 | 18.4 | 35.8 | 30.2 | 57.6 | *** | 506 |

| Private health insurance | 54.0 | 56.9 | 67.1 | 70.4 | 72.8 | 86.4 | *** | 1294 |

| Race | ||||||||

| White | 52.7 | 47.1 | 60.8 | 60.4 | 65.6 | 79.7 | *** | 1210 |

| Black | 23.2 | 22.1 | 16.3 | 16.4 | 7.2 | 5.1 | *** | 435 |

| Hispanic | 19.5 | 22.6 | 22.9 | 13.8 | 14.9 | 5.1 | * | 409 |

| Asian | 4.9 | 8.2 | 0.0 | 9.4 | 12.3 | 10.2 | *** | 134 |

| Ethical concerns | ||||||||

| Lowest | 31.1 | 30.3 | 30.7 | 27.2 | 37.6 | 40.7 | n.s. | 691 |

| Higher | 38.8 | 41.5 | 42.5 | 39.9 | 46.6 | 44.1 | n.s. | 881 |

| Highest | 32.1 | 28.2 | 26.8 | 32.9 | 15.8 | 15.3 | *** | 638 |

| Motherhood important | 47.1 | 52.8 | 46.1 | 58.5 | 62.4 | 78.0 | *** | 1110 |

Chi square tests performed on all variables

=p<.05

=p<.01

=p<.001

The results of the series of analyses are in Table 2. For ease of presentation, we have not displayed the control variables (available upon request). Although the χ2 is significant in all analyses, other fit statistics are within the prescribed limits, suggesting that the model fits the data adequately. Neither religiosity nor religious attendance was associated with helpseeking in any of the analyses. Ethical concern about reproductive technology was negatively associated with helpseeking at all stages of the treatment process except the transition to ART; for this latter comparison, this may be due low statistical power because the effect size remains large (OR=.60). The relationship is strongest when comparing tests and lower stages of helpseeking to being treated. Increased ethical concerns reduces the odds of moving to the treatment stage by a factor of over three (OR=.30). Thus, the influence of ethical concerns on helpseeking can be observed throughout the helpseeking process but is strongest at the point where women move from lower stages of help-seeking to actually undergoing treatment.

Table 2.

Effects of religiosity on stages of infertility helpseeking (N=2,167)

| Considered | Talked to doctor | Tests | Treatment | ART | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | |

| Dep=religious attendance | ||||||||||

| Religiosity | 1.213 | .598 *** | 1.210 | .598 *** | 1.210 | .598 *** | 1.202 | .599 *** | 1.208 | .599 *** |

| R square | .355 | .354 | .355 | .356 | .356 | |||||

| Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | |

| Dep=ethical concerns | ||||||||||

| Religiosity | .011 | .052 | .011 | .052 | 0.011 | 0.052 | .011 | .052 | .011 | .051 |

| Religious attendance | .017 | .159 ** | .017 | .159 ** | 0.017 | 0.159 ** | .016 | .158 ** | .017 | .159 ** |

| R square | .093 | .093 | .093 | .093 | .093 | |||||

| Dep=imptnce of motherhd | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta | Est. | Beta |

| Religiosity | .096 | .200 *** | .096 | .176 *** | 0.096 | 0.200 *** | .095 | .200 *** | .095 | .200 *** |

| Religious attendance | .010 | .041 | .010 | .041 | 0.010 | 0.041 | 0.010 | 0.041 | 0.010 | 0.041 |

| R square | .135 | .135 | .135 | .135 | .135 | |||||

| Dep=helpseeking | Est. | OR | Est. | OR | Est. | OR | Est. | OR | Est. | OR |

| Ethical concerns | -.424 | .654 * | -.477 | .621 ** | -.689 | .502 ** | -1.219 | .296 *** | -.520 | .595 |

| Imptnce of motherhd | .120 | 1.127 | .114 | 1.121 | .222 | 1.249 ** | .173 | 1.189 | .359 | 1.432 ** |

| Religious attendance | .037 | 1.038 | .022 | 1.022 | .045 | 1.046 | .024 | 1.024 | -.009 | .991 |

| Religiosity | -.096 | .908 | -.051 | .950 | -.046 | .955 | .116 | 1.123 | .080 | 1.083 |

| Pseudo R square | .459 | .441 | .504 | .547 | .493 | |||||

| Chi square | 133.993 | 132.276 | 136.957 | 138.987 | 139.565 | |||||

| CF! | .961 | .962 | .958 | .956 | .957 | |||||

| TLI | .956 | .957 | .953 | .951 | .951 | |||||

| RMSEA | .019 | .019 | .020 | .020 | .020 | |||||

| WRMW | .905 | .883 | .914 | .921 | .917 | |||||

=p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Helpseeking categories: 0 = No help; 1 = Considered; 2 =talked to Doctor; 3 = Medical tests; 4 = Infertility Treatment; 5 = ART Control Variables (primary infertility, infertile with intent, wants a(nother) child, age, income, education, private health insurance,

Importance of motherhood was associated with increased odds of helpseeking, but only at two stages of the treatment process: when women moved between seeing a doctor and all lower stages of helpseeking to actually having medical tests (OR=1.25) and between conventional treatment and lower stages to ART (OR=1.43). Thus, the importance of motherhood plays a role at two crucial points in the help-seeking continuum where women must commit to undergoing invasive and time-consuming procedures. Having primary infertility and being infertile with intent were both associated with higher odds of proceeding to the next stage of helpseeking for all analyses. Stronger desire to have a child and having private insurance increased the odds of being in the next level of helpseeking in the early stages of the process. Age was relevant to helpseeking in the middle of the process. Race and income both were associated with helpseeking in the later stages of helpseeking. Our analysis accounts for about half of the variation in helpseeking (pseudo-R2 ranges from .441 to .547).

We turn now to the mediating variables: ethical concern and importance of motherhood. Religiosity was not related to ethical concerns about infertility treatment in any of the analyses, but religious attendance was positively associated with ethical concerns, regardless of helpseeking stage. In other words, women with higher levels of religious attendance were more likely to express ethical concerns about assisted reproductive technology. Additionally, Black, Hispanic, and Asian women express greater ethical concerns about infertility treatment than non-Hispanic White women and those who identify as members of other races.

As hypothesized, higher religiosity was associated with higher importance of motherhood in all five analyses. Women with primary infertility had lower importance of motherhood scores than women with secondary infertility. Women who were infertile with intent and women who reported wanting a (nother) child had higher importance of motherhood scores. Higher age was associated with lower importance of motherhood in all analyses. Black and Hispanic women scored lower on importance of motherhood than other women. Our analysis accounted for approximately one eighth of the variation in importance of motherhood (R2 =.135). Religiosity was strongly associated with religious attendance in all analyses. Thus, although religiosity was not associated with ethical concerns directly, it was associated with religious attendance, which in turn was associated with ethical concerns. Higher income and education were associated with higher religious attendance in all analyses, but with lower religious beliefs in all analyses. Black and Hispanic women have higher religiosity scores than non-Hispanic White women and women of “other” races in all analyses.

Table 3 further specifies the patterns of associations by providing total, direct, and indirect effects of religiosity on helpseeking. Only in the comparison between treatment and all lower stages of helpseeking is the total effect of religiosity on helpseeking significant. The direct effects of religiosity on helpseeking are not significant in any models. In some analyses, religiosity is associated with lower helpseeking through attendance and ethical concerns, and in others is associated with higher helpseeking through importance of motherhood. These effects, however, cancel each other out in all but one case.

Table 3.

Total, Indirect, and direct effects of religiosity on stages of infertility helpseeking.

| Considered | Talked to doctor | Tests | Treatment | ART | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Est. | S.E. | Sig. | Est. | S.E. | Sig. | Est. | S.E. | Sig. | Est. | S.E. | Sig. | Est. | S.E. | Sig. | |

| Total effects | -0.52 | 0.04 | n.s. | -0.03 | 0.05 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.05 | n.s. | 0.13 | 0.05 | ** | 0.09 | 0.06 | n.s. |

| Total indirect effects | 0.04 | 0.04 | n.s. | 0.02 | 0.04 | n.s. | 0.05 | 0.04 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.04 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.05 | n.s. |

| Through attendance | 0.04 | 0.04 | n.s. | 0.03 | 0.03 | n.s. | 0.05 | 0.04 | n.s. | 0.03 | 0.04 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.05 | n.s. |

| Through ethical concern.s. | 0.00 | 0.01 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. |

| Through att, ethics | -0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. | -0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.01 | * | -0.02 | 0.01 | ** | -0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. |

| Through motherhood | 0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. | 0.01 | 0.01 | n.s. | 0.02 | 0.01 | ** | 0.02 | 0.01 | n.s | 0.03 | 0.16 | * |

| Through att, mother | 0.00 | 0.00 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.00 | n.s. | 0.00 | 0.01 | n.s. |

| Direct effects | -0.10 | 0.06 | n.s. | -0.05 | 0.06 | n.s. | -0.07 | 0.07 | n.s. | 0.12 | 0.07 | n.s. | 0.08 | 0.10 | n.s. |

Discussion and Conclusions

The current study is the first we know of that examines the relationship between religion and infertility helpseeking using a nationally representative sample. Religion is not directly related to infertility helpseeking in most analyses, though this does not mean that religion is unrelated to helpseeking. Specifically, the positive effect of religion on helpseeking through the importance of motherhood is counterbalanced by a strong negative impact through increased ethical concerns. The evidence presented here suggests that the relationship between religion and infertility helpseeking is complicated. First, as noted above, religion appears to have both positive and negative impacts on infertility helpseeking. Second, the influence of religiosity on importance of motherhood is direct while the influence of religiosity on ethical concerns is indirect, through religious attendance. Third, the exact nature of the relationship between religion and helpseeking varies at different stages of the helpseeking process. It is only at the stage of moving from all lower stages of helpseeking (i.e., seeing a doctor, contemplating seeking help, not seeking any help) to receiving tests that our hypothesis is confirmed.

Our findings confirm previous research that identifies stronger pronatalist beliefs among religious women (Hayford & Morgan, 2008; Koropeckyj-Cox & Pendell, 2007). Results also lend support to studies indicating increased ethical concerns about medical tests and treatments, such as genetic testing and prenatal tests, among religious individuals (Singer, Corning, & Lamias, 1998). These conflicting influences result in a lack of an overall relationship, which is at odds with the previous findings that higher religiosity is associated with higher odds of seeking non-necessary medical service utilization. These previous studies on preventive services provide some foundation for the current study, which also examines a “voluntary” health service. The treatments for infertility are debated by religious leaders, however, and in some cases prohibited. Therefore the association between religiosity and medical helpseeking seems to depend upon the specific health issue studied. The relevance of religion for fertility in general and for infertility treatments, therefore, is likely to make helpseeking for this condition unlike many other health conditions.

As noted earlier, the possible mechanisms linking the different dimensions of religion to service utilization could be specific to each dimension. The current study revealed that religiosity is only related to ethical concerns about infertility treatments through attendance. In other words, it is only through involvement at religious services that religious women become more likely to have such ethical concerns. This may reflect individuals who attend more frequently having greater exposure to their religious organization’s official position on allowable infertility treatments. In contrast, individuals who have high levels of religiosity but less (or no) involvement with a religious organization may be unaware of such theological debates and stances. In addition, those who attend religious services more frequently may also be exposed to other individuals who disapprove of those choosing to disregard church policies and who may offer support for choosing alternatives in line with the stated positions. Findings regarding the lack of an association between attendance and the importance of motherhood are less easily explained and deserve further exploration.

As with all studies, there are limitations to this project. First, cross sectional data limit strong conclusions about temporal ordering. We know, for example, that higher ethical concerns are associated with lower levels of helpseeking, but we cannot decisively conclude that ethical concerns cause women to forgo treatments that might be medically appropriate. To make such claims, we need longitudinal data. Wave 2 of the NSFB, now in the field, will provide better temporal ordering and more clarity about the direction of associations. Central concepts (religiosity, importance of motherhood, and ethical concerns) were also measured contemporaneously, after the infertility episode. Therefore is possible that some women may have different attitudes at the time of the survey than they did during the infertility episode. For example, women who had few ethical concerns at the time they decided not to pursue treatment might have developed ethical concerns in retrospect. Here too, data from Wave 2 should help further specify the patterns of associations.

Many of the effect sizes reported here are relatively small. Clearly, we cannot argue that religion accounts for a major portion of the variation in infertility helpseeking. Nonetheless, the study of infertility has been shown to be an appropriate site for demonstrating the complexities of the association between religion and helpseeking. Another limitation of this study is that we were unable to test for the association of religious denomination on infertility helpseeking. This is an important issue to address in future studies.

In addition, more work is necessary to better understand the role of social and cultural factors in helpseeking. To begin, specific information about an individual’s religious affiliation would be useful to clarify the theological and social sources of potential ethical concerns. Furthermore, other aspects of the culture in which the infertile individual resides could be expected to influence the relationship between religion and helpseeking. To elucidate these influences, future studies are needed to explore the impact of religion among specific race/ethnic groups and within different countries. Additionally, because infertility is often experienced in the context of marriage or other intimate relationships, it may be important to understand how partners’ religiosity and religious affiliations either promote or inhibit help-seeking, particularly if partners have differing religious attitudes or dissimilar religious affiliations.

This study has implications beyond the study of infertility. Most generally, it supports the growing consensus that religiously-based behaviours and beliefs are associated with service utilization under specific conditions. For non-life threatening conditions, this study suggests that the meaning of the problem (e.g. importance of motherhood) mediates the association between religiosity and helpseeking. Additionally, if treatments are the topic of religious teaching (e.g. abortion, stem cell therapies), then attitudes about the ethics of these concerns should mediate the effects of religiosity on medical helpseeking. Specifying the associations between religious behaviour, religious beliefs, and medical helpseeking shows how meanings of symptoms and outcomes are crucial to understanding medical care. Increasing access to care by reducing cost and increasing coverage are very important, but alone are unlikely to be to meet potential medical care need. It is also important to understand the meaning of symptoms and treatments in order to understand how religion is associated with health service utilization.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grant R01-HD044144 “Infertility: Pathways and Psychosocial Outcomes” funded by NICHD. Dr. Lynn White (The University of Nebraska-Lincoln) and Dr. David R. Johnson (The Pennsylvania State University) were Co-PIs on the first wave of data collection.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Julia McQuillan, University of Nebraska at Lincoln.

Maureen Benjamins, Sinai Urban Health Institute

David R Johnson, Pennsylvania State University

Katherine M Johnson, Pennsylavania State University

Chelsea R Heinz, Alfred university

References

- Allison P. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Asser SM, Swan R. Child fatalities from religion-motivated medical neglect. Pediatrics. 1998;101:625–629. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker G. The elusive embryo: How women and men approach new reproductive technologies. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR. Social determinants of preventive service utilization: How religion influences the use of cholesterol screening in older adults. Research on Aging. 2005;27:475–497. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR. Religious influences on female preventive service utilization in a nationally representative sample of older women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;29:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10865-005-9035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR. Predictors of preventive health care use among middle-aged and older adults in Mexico: the role of religion. Journal of Cross Cultural Gerontology. 2007;22:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10823-007-9036-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR, Brown C. Religion and preventative health utilization among the elderly. Social Science and Medicine. 2004;58:109–118. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00152-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamins MR, Trinitapoli J, Ellison CG. Religious attendance, health beliefs, and mammogram utilization in a nationwide sample of Presbyterians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45:597–607. [Google Scholar]

- Bittler M, Schmidt L. Health Disparities and Infertility: Impacts of State Level Insurance Mandates. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;85:858–865. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin J, Bunting L, Collins J, Nygren KG. International estimates of infertility prevalence and treatment-seeking: Potential need and demand for infertility medical care. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:1506–1506. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley DE. Religious involvement and social resources: Evidence from the dataset ‘Americans’ Changing Lives.’. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1995;34:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Brant R. Assessing proportionality in the proportional odds model for ordinal logistic regression. Biometrics. 1990;46(4):1171–1178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulcroft R, Teachman J. Ambiguous constructions: Development of a childless or childfree life course. In: Coleman M, Ganong LH, editors. Handbook of contemporary families. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Martinez AG, Mosher WD, Abma JC, Jones J. Fertility, family planning, and reproductive health of U.S. women: Data from the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Statistics. 2005;25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Stephen EH. Impaired fecundity in the United States: 1982-1995. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30:34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM. Religion and public health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health. 2000;21:335–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. Donum vitae: Instruction on respect for human life in its origin and on the dignity of procreation. 1987 Retrieved June 2009, from http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_19870222_respect-for-human-life_en.html.

- Contrada R, T J, Goyal TM, Cather C. Psychosocial factors in outcomes of heart surgery: The impact of religious involvement and depressive symptoms. Health Psychology. 2004;23:227–238. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutney A. Religion, infertility, and assisted reproductive technology. Best Practice and Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2007;21:169–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Lee J, Benjamins MR, Kraus NM, Ryan DN, Marcum JP. Congregational support networks, health beliefs, and annual medical exams: Findings from a nationwide sample of Presbyterians. Review of Religious Research. 2008;50(2):176–193. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, Levin JS. The Religion-Health Connection: Evidence, Theory, and Future Directions. Health Education & Behavior. 1998;25:700–720. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix-Aaron K, Levine D, Burstein HR. African American church participation and health care practices. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2003;18:908–913. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20936.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SA, Pitkin K, Paul C, Carson S, Duan N. Breast cancer screening adherence: Does church attendance matter? Health Education and Behavior. 1998;25:742–758. doi: 10.1177/109019819802500605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George LK, Ellison CG, Larson DB. Explaining religious effects on health. Psychological Inquiry. 2002;13:190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Grasmick H, Wilcox LP, Bird S. The effects of religious fundamentalism and religiosity on preference for traditional family values. Sociological Inquiry. 1990;60:352–369. [Google Scholar]

- Greil AL. Not yet pregnant: Infertile couples in contemporary America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Greil AL, McQuillan J. Help-seeking patterns among subfecund women. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2004;22:305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Greil AL, McQuillan J, Shreffler K, Johnson KM, Slauson-Blevins K. Explaining racial/ethnic disparities in helpseeking: The case of infertility; Paper presented at annual meeting of the Society for the Study of Social Problems; San Francisco, CA. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hackney CH, Sanders GS. Religiosity and mental health: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42:43–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford SR, Morgan SP. Religiosity and fertility in the United States: The role of fertility intentions. Social Forces. 2008;86:1163–1188. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TD, Ellison CG, Burdette AM, Musick MA. Religious attendance and the health behaviors of Texas adults. Preventative Medicine. 2006;42:309–312. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch MB, Mosher WD. Characteristics of infertile women in the United States and their use of infertility services. Fertility and Sterility. 1987;47:618–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, Bahr SM. Crime/deviance. In: Ebaugh HR, editor. Handbook of Religion and Social Institutions. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 241–263. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth LD. Who Seeks to Adopt a Child? Findings from the National Survey of Family Growth (1995) Adoption Quarterly. 2000;3:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Clark EM, Kreuter MW, Rubio DM. Spiritual health locus of control and breast cancer beliefs among urban African American women. Health Psychology. 2003;22:294–299. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Lukwago SN, Kreuter MW. Spirituality, breast cancer beliefs, and mammography utilization among urban African American women. Journal of Health Psychology. 2003;8:383–396. doi: 10.1177/13591053030083008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob MC, McQuillan J, Greil AL. Psychological distress by type of fertility barrier. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:885–894. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L, Jensen J. Family values, religiosity and gender. Psychological Reports. 1993;73:429–430. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DR, White LK. National Survey of Fertility Barriers methodology report. Population Research Institute, Pennsylvania State University; 2009. Retrieved May, 2009, from http://sodapop.pop.psu.edu/data-collections/nsfb/dnd. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KS, Elbert-Avila KI, Tulsky JA. The influence of spiritual beliefs and practices on the treatment preferences of African Americans: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Geriatric Society. 2005;53:711–719. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeter S, Kennedy C, Dimock M, Best J, Craighill P. Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone Survey. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70:759–779. [Google Scholar]

- King DE, Pearson WS. Religious attendance and continuity of care. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2003;33:377–389. doi: 10.2190/F5DY-5GAB-K298-EMEK. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Use of acute hospital services and mortality among religious and non-religious copers with medical illness. Journal of Religious Gerontology. 1995;9(3):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Larson DB. Use of hospital services, religious attendance, and religious affiliation. Southern Medical Journal. 1998;91:925–932. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199810000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Larson DB. Religion and Mental Health: Evidence for an Association. International Review of Psychiatry. 2001;13:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, McCullough MF, Larson DB. Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Koropeckyj-Cox T, Pendell G. Attitudes about childlessness in the United States: Correlates of positive, neutral, and negative responses. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28:1054–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Markides KS. Religion and health in Mexican Americans. Journal of Religion and Health. 1985;24(1):60–69. doi: 10.1007/BF01533260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Rook KS. Social control and personal relationships: Impact on health behaviors and psychological distress. Health Psychology. 1999;18:63–71. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney A, Carels RA, Pargament KI, Wachhholtz A, Leeper LE, Kaplar M, Frutchey R. The sanctification of the body and behavioral health patterns of college students. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 2005;15:221–238. [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, House M, Harman J, Richards S. Effort in phone survey response rates: The effects of vendor and client-controlled factors. Field Methods. 2006;18:172–188. [Google Scholar]

- McCullough ME, Larson DB, Hoyt WT, Koenig HG, Thoresen C. Religious involvement and mortality: A meta-analytic review. Health Psychology. 2000;19:211–222. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Medical Sociology: A Selective View. New York: Free Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Muramoto O. Recent developments in medical care of Jehovah’s Witnesses. Western Journal of Medicine. 1999;170:297–301. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagel E, Sgoutas-Emch S. The relationship between spirituality, health beliefs, and health behaviors in college students. Journal of Religion and Health. 2007;46:141–154. [Google Scholar]

- Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58:36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodin J. Control by any other name: Definitions, concepts, and processes. In: Rodin J, Schooler C, editors. Self-directedness: Cause and effects throughout the life course. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. With child in mind: Studies of the personal encounter with infertility. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Schenker JG. Assisted reproductive practice: Religious perspectives. [January, 2005];Reproductive Biomedicine Online. 2005 doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61789-0. at: www.rbmonline.com/Article/1539. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schieman SH, Pudrovska T, Pearlin LI, Ellison CG. The sense of divine control and mental health in late life: Moderating effects of race and socioeconomic status. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45:529–549. [Google Scholar]

- Schiller PL, Levin JS. Is there a religious factor in health care utilization? Social Science and Medicine. 1988;27:1369–1379. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(88)90202-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L, Munster K. Infertility, involuntary infecundity, and the seeking of medical advice in industrialized countries 1970-1992: A review of concepts, measurements and results. Human Reproduction. 1995;10:1407–1418. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.6.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer E, Corning A, Lamias M. The polls-trends: Genetic testing, engineering, and therapy: Awareness and attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1998;62:633–664. [Google Scholar]

- Straughan PT, Seow A. Fatalism reconceptualized: A concept to predict health screening behavior. Journal of Gender, Culture, and Health. 1998;3:85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Straughan PT, Seow A. Attitudes as barriers in breast screening: A prospective study among Singapore women. Social Science & Medicine. 2000;51:1695–1703. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. Church members as a source of informal social support. Review of Religious Research. 1988;30:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- Throsby K, Gill R. “It’s different for men”: Masculinity and IVF. Men and Masculinities. 2004;6:330–348. [Google Scholar]

- White L, McQuillan J, Greil AL, Johnson DR. Infertility: Testing a help-seeking model. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62:1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. Generalized ordered logit/partial proportional odds models for ordinal dependent variables. The Stata Journal. 2006;6:58–82. A pre-publication version is available at http://www.nd.edu/~rwilliam/gologit2/gologit2.pdf.

- Winship C, Mare RD. Regression models with ordinal variables. American Sociological Review. 1984;49:512–525. [Google Scholar]

- Zarit SH, Pearlin L, Schaie KW. Mastery and control in the elderly. New York: Springer Publishing Co; 2002. [Google Scholar]