Abstract

In the past decade, podocyte research has been greatly aided by the development of powerful new molecular, cellular and animal tools, leading to elucidation of an increasing number of proteins involved in podocyte function and identification of mutated genes in hereditary glomerulopathies. Accumulating evidence indicates that podocyte disorders may not only underlie these hereditary glomerulopathies but also play crucial role in a broad spectrum of acquired glomerular diseases. Genetic susceptibility, environmental influence and systemic responses are all involved in the mediation of the pathogenesis of podocytopathies. Injured podocytes may predisopose to further injury of other podocytes and other adjacent/distant renal cells in a vicious cycle, leading to inexorable progression of glomerular injury. The classic view is that podocytes have a limited ability to proliferate in the normal mature kidney. However, recent research in rodents has provided suggestive evidence for podocyte regeneration resulting from differentiation of progenitor cells within Bowman’s capsule.

Keywords: podocyte, foot process effacement, slit diaphragms, hereditary proteinuria syndrome, acquired glomerular diseases, VEGF, progenitor cells, FSGS, diabetic nephropathy and kidney

1. INTRODUCTION

Podocytes are highly specialized epithelial cells that cover the outer layer of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), playing a crucial role in regulation of glomerular function, and podocyte injury is an essential feature of progressive glomerular diseases (Mundel and Kriz, 1995). Since the late 1990’s, studies using modern molecular and genetic techniques have increasingly extended our knowledge regarding the components and function of the podocyte and its role in congenital nephrotic syndromes (Tryggvason et al., 2006). Transmission electron microscopy has identified clear glomerular filtration barrier structures (Salmon et al., 2009). Human (Saleem et al., 2002) and rodent (Mundel et al., 1997, Mundel et al., 1997) differentiated podocyte culture techniques have allowed the study of podocytes in vitro (Shankland et al., 2007). In addition, the zebrafish glomerulus (Morello and Lee, 2002) as well the recent identification in Drosophila melanogaster of podocyte-like cells (the “nephrocyte”) with remarkably conserved slit diaphragms (Chaib et al., 2008), offer simpler model organisms in which to study podocyte biology and podocyte-associated diseases.

Recent studies indicate that local podocyte damage can spread to induce injury in otherwise healthy podocytes and further affect both glomerular endothelial and mesangial cells, implying that even limited podocyte injury might initiate a vicious cycle of progressive glomerular damage (Ichikawa et al., 2005). Podocyte injury due to mutation or alteration of intracellular proteins unique to this cell type underlies the hereditary proteinuric syndromes but is also involved in wide spectrum of acquired glomerular diseases. Despite a dramatically increased knowledge of podocyte biology, mechanisms underlying functional and structural podocyte disturbances, especially “crosstalk” between podocytes and endothelial or other cells during renal diseases, still remain incompletely delineated (Shankland, 2006). A brief update of podocyte biology, the podocyte’s pathogenic role in glomerular diseases and potential new therapeutic approaches are the subject of this review.

2. NEW ASPECTS IN PODOCYTE BIOLOGY

Podocytes are a highly differentiated cell with unique architecture. They are comprised of three major parts: cell body, major processes and foot processes. The foot processes of neighboring podocytes regularly interdigitate, leaving between them the filtration slits that are bridged by an extracellular structure, known as the slit diaphragm (Asanuma and Mundel, 2003). The slit diaphragm represents the only cell-cell contact between podocytes, while highly dynamic foot processes interposed to the slit diaphragm maintain podocyte structure to sustain the barrier function (Mundel and Shankland, 2002). Foot processes contain abundant microfilaments and modulate glomerular filtration (Ichimura et al., 2003), and the structure is maintained by an intricate actin cytoskeleton. Interference of actin cytoskeleton interactions with the slit diaphragm or the basal domain of foot processes itself will ultimately cause foot process effacement and proteinuria (Mundel and Shankland, 2002). Mutations in genes encoding slit diaphragm proteins result in proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome in both animal models and patients. The glomerular filtration barrier is traditionally considered as resulting from the fenestrated endothelial cells, glomerular basement membrane (GBM) and the slit diaphragm formed by the podocytes. Recently Salmon and his colleagues (Salmon et al., 2009) proposed adding two additional sites: the endothelial surface layer (ESL) and the subpodocyte space (SPS). ESL is a carbohydrate rich meshwork coating the luminal aspect of cytoplasmic and fenestral proteins of glomerular endothelial cells and may play an important role in glomerular permeability (Rostgaard and Qvortrup, 1997, Salmon et al., 2009). A new three-dimensional reconstruction of urinary spaces in the glomerular corpuscle using serial section transmission electron microscopy discovered that there are three interconnected but ultrastructurally distinct urinary spaces (Neal et al., 2007). SPS is bounded by the podocyte cell body and/or thin plate-like extensions above the podocyte cell body and under the glomerular filtration barrier, and SPSs cover 60% of the entire filterable surface area of the filtration barrier.

Newly discovered proteins that comprise the slit diaphragm junctional complex have been recently reviewed (Garg et al., 2007, Lowik et al., 2009, Tryggvason et al., 2006). They play a critical role in coordinating podocyte structure and function. Regardless of the debate concerning charge selectivity (Miner, 2008), GBM may be more than a fixed passive sieve (Salmon et al., 2009); in addition, podocytes are able to endocytose albumin, a process that appears to be statin sensitive (Eyre et al., 2007), and even to reverse filtration over a proportion of the glomeruli, suggesting a possible physiological role in the regulation of glomerular fluid flux across the glomerular barrier (Neal et al., 2007). New evidence has indicated that FcRn, an IgG and albumin transport receptor, is expressed in podocytes and functions to internalize IgG from the GBM, so podocytes may play an active role in removing proteins from the GBM (Akilesh et al., 2008). Recent studies have also documented several polarity protein complexes in podocytes such as the partitioning defective 3 (PAR3), partitioning defective 6 (PAR6) and atypical protein kinase C complex and have suggested an essential role for normal podocyte morphology and differentiation, suggesting that polarity signaling pathways may be involved in the regulation of glomerular development, slit diaphragm targeting and apico-basolateral molecular distribution (Simons et al., 2009).

These findings indicate a close connection of podocytes with adjacent components within the glomerular filtration barrier, especially with endothelial cells (Eremina et al., 2007). Signaling pathways in the “crosstalk” between podocytes and other adjacent cells (such as endothelial and mesangial cells) could play an important role in normal glomerular physiology and in the progression of glomerular diseases.

3. MUTATIONS OF PODOCYTE COMPONENTS IN HEREDITARY PROTEINURIA SYNDROM

Mutations in podocyte components are associated with hereditary renal diseases. Since the slit diaphragm and associated proteins regulate podocyte actin dynamics, mutations can alter podocyte functions, leading to proteinuria. Cytoskeleton de-organization also disrupts podocyte integrity, and alterations in transcriptional factors can lead to altered expression of podocyte-specific proteins and result in aberrant podocyte function (Chugh, 2007). The list of hereditary proteinuria syndromes associated with the mutation of podocyte molecules in slit diaphragm, cytoskeleton and nuclear transcriptional factors (Table I) continues to expand.

Table I.

Genetic glomerular diseases and their associated mutated podocyte genes

| Gene | Protein | Associated Disease | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slit Diaphram | |||

| NPHS1 | Nephrin | Finnish type NS | (Kestila et al., 1998) |

| NPHS2 | Podocin | Steroid-resistant NS | (Boute et al., 2000) |

| CD2AP | CD2 associated protein | NS in KO Mice | (Shih et al., 1999) |

| TRPC6 | TRPC6 | FSGS | (Winn et al., 2005) (Reiser et al., 2005) |

| PLCE1 | Phospholipase Cε1 | Early-onset NS with ESRD |

(Hinkes et al., 2006) |

| Cytoskeleton | |||

| ACTN4 | α Actin 4 | FSGS | (Kaplan et al., 2000) |

| MYH9 | NMMHC-A | FSGS | (Kao et al., 2008) |

| Nuclear protein | |||

| WT1 | Wilms’ tumor 1 | Denys Drash syndrome | (Jeanpierre et al.,1998) |

| LMX1B | LIM-homeodomain protein | Nail-patella syndrome | (Rohr et al., 2002) |

NS: nephritic syndrome; FSGS: focal segmental glomerular sclerosis; ESRD: end stage renal disease; KO: knock-out.

In recent years, genetic analysis of congenital and early childhood-onset human nephrotic syndrome and gene manipulation in animal experiments has greatly expanded our knowledge of slit diaphragm proteins (Mundel and Shankland, 2002). Slit diaphragm molecules are critical in maintaining the filtration barrier of the kidney and preventing protein loss into the urine. In the 1990’s, positional cloning of the gene responsible for congenital nephritic syndrome of the Finnish type led to the identification of nephrin (Kestila et al., 1998), which directly links podocyte junctional integrity to actin cytoskeletal dynamics (Asanuma et al., 2007). Nephrin is a transmembrane protein with a large extracellular portion of eight immunoglobulin-like domains. Neighboring nephrin molecules extend toward each other from adjacent foot-processes and interact through homophilic dimerization to form a zipper-like arrangement. The gene (NPHS1) is located on chromosome 19 and encodes a 136 kDa protein product (Kestila et al., 1998). Subsequently, CD2-associated protein (CD2AP), an adaptor molecule involved in podocyte homeostasis was confirmed to be another slit diaphragm component responsible for congenital nephrotic syndrome in mice deficient in the protein (Shih et al., 1999). However, mutations of CD2AP in human do not exclusively cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (Wolf and Stahl, 2003). Mutation of a gene, NPH2, associated with autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome was mapped to 1q25-31 found to be exclusively expressed in the podocytes of fetal and mature kidney glomeruli; it encodes an integral membrane protein, podocin (Boute et al., 2000). Winn et al. and Reiser et al. (Reiser et al., 2005, Winn et al., 2005) reported the identification of a mutation in TRPC6, a member of the transient receptor potential superfamily of non-selective cation channels (Montell, 2005, Ramsey et al., 2006) in patients with an autosomal dominant pattern of adult onset FSGS. TRPC6 is expressed in podocytes and co-localizes with nephrin, podocin and CD2AP (Reiser et al., 2005). The calcium-dependent phosphorylation and disassembly of the slit diaphragm is believed to underlie the pathogenic effects of TRPC6 mutations (Tiruppathi et al., 2002) (Schlondorff and Pollak, 2006).

In summary, the slit diaphragm represents a signaling platform that contributes to the regulation of podocyte function in health and disease (Benzing, 2004) (Huber and Benzing, 2005). An increasing number of proteins that comprise the slit diaphragm has been identified. Some proteins, such as FAT (Inoue et al., 2001, Jalanko et al., 2001), ZO-1(Kurihara et al., 1992), P-cadherin (Reiser et al., 2000) (Xu et al., 2005) and PLCE1 (Hinkes et al., 2006) have also been identified as SD components. All these proteins participate in intracellular signaling networks to support cytoskeletal organization, cell adhesion, and cell polarity; not surprisingly mutations in mice have shown effects on podocyte function and recent studies have indicated that PLCE1 mutations are a cause of congenital nephrotic syndrome in humans (Hinkes et al., 2006), although there may be additional genetic causes of FSGS (Gbadegesin et al., 2009).

The actin cytoskeleton anchors cell-cell contact and cell-matrix proteins, providing mechanical stability and a high dynamic capacity to respond to physical stress (Endlich and Endlich, 2006). Several human genetic diseases as well as transgenic mouse models provide evidence for a crucial role of the actin cytoskeleton in podocytes. In vitro, mutant alpha-actinin-4 binds filamentous actin (F-actin) more strongly than does wild-type alpha-actinin-4, an actin crosslinking protein. Mice with mutations in the gene encoding alpha-actinin-4 (ACTN4) develop autosomal dominant focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (Kos et al., 2003, Michaud et al., 2003). In human, mutations in ACTN4 cause or increase susceptibility to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (Kaplan et al., 2000). Some other specific proteins may also play important roles in actin filament bundling in foot processes, such as synaptopodin (Asanuma et al., 2005), palladin (Parast and Otey, 2000) and the non-muscle myosin heavy chain II A (NMMHC-IIA), a cytoskeletal contractile protein. Human Myosin heavy chain 9 (MYH9) gene encodes NMMHC-IIA and is mainly expressed in podocytes and peritubular vessels in the mature kidney (Arrondel et al., 2002); its mutation is responsible for Fechtner's syndrome (nephritis, deafness, congenital cataracts, macrothrombocytopenia, and characteristic leukocyte inclusions) (Seri et al., 2000). New genetic evidence suggests that MYH9 gene alterations are associated with an increased risk for developing FSGS and hypertensive nephrosclerosis in African Americans (about two to four times greater risk of nondiabetic end stage renal diseases compared to European Americans) (Kao et al., 2008).

In summary, the highly dynamic foot processes of podocytes contain an actin-based contractile apparatus comparable to that of smooth muscle cells or pericytes. The convergence of multiple interconnected signaling pathways from the cell membrane of different foot process domains on the podocyte actin cytoskeleton involves not only actin binding proteins, but also its signaling pathway, such as Rho family GTPases. Mutations affecting several podocyte proteins lead to rearrangement of the actin cytoskeleton, disruption of the filtration barrier and development of proteinuric renal disease (Faul et al., 2007).

A growing numbers of podocyte-expressed transcriptional factors that regulate podocyte function under normal and disease conditions have been identified. Wilm’s tumour1 (WT-1), a zinc finger protein, was the first recognized gene that is a podocyte transcriptional factor linked with human renal diseases: constitutional mutations of the WT1 gene are found in most patients with Denys-Drash syndrome, or diffuse mesangial sclerosis, associated with pseudohermaphroditism and/or Wilms tumor (Barbaux et al., 1997, Jeanpierre et al., 1998). Varying degrees of loss of podocyte WT1 content (Barisoni et al., 1999) or gene mutations (Orloff et al., 2005) are noted in specific forms of focal glomerulosclerosis. The most dramatic reduction in WT1 expression in human disease is seen in the collapsing variant of FSGS. Two WT1 associated proteins, WT1-interacting protein and brain acid soluble protein 1, are also expressed in the podocyte and function as corepressors of WT1 transcriptional factor activity. WT1-interacting protein monitors slit diaphragm protein assembly as part of a multiprotein complex, linking this specialized adhesion junction to the actin cytoskeleton, and shuttles into the nucleus after podocyte injury (Srichai et al., 2004). Mutations underlying the development of nail-patella syndrome have been linked to the LIM homeobox transcription factor 1β (Lmx1b) gene, which is expressed in podocytes (Dreyer et al., 1998) (McIntosh et al., 1998) (Vollrath et al., 1998). The Lmx1b protein appears to be particularly important during early embryonic development of the limbs, kidneys, and eyes. The findings in patients are corroborated by the fact that the inactivation of Lmx1b in mice also leads to a phenotype strongly resembling nail-patella syndrome (Chen et al., 1998, Sato et al., 2005) (Rohr et al., 2002). With continuing advancement in microarray array - based technology, large scale identification of additional target genes mediating podocyte-expressed transcriptional factors will soon be available (Chugh, 2007). It should also be noted that inherited defects in GBM and mitochondrial and lysosomal protein defects can also cause podocyte dysfunction, leading to glomerular diseases (Machuca et al., 2009, Moller et al., 2006).

4. THE ROLE OF PODOCYTE DISORDERS IN ACQUIRED GLOMERULAR DISEASES

Genotype-phenotype correlation and genetic molecular cloning have not only led to the discovery of the above mentioned gene mutations responsible for hereditary proteinuric syndrome but have also provided new insights into the potential role of podocyte disorders in non-congenital glomerular diseases. It is well known that podocytes are a major target in Minimal Change Disease and FSGS, and increasing evidence indicates that podocyte injury is also involved in a variety of other glomerular diseases, such as diabetic nephropathy, HIV nephropathy, membranous nephropathy and other acquired glomerular diseases (Mathieson, 2009).

Regardless of the etiology or pathologic classification, there are four major patterns of podocyte morphology alteration during glomerular diseases:

Foot process effacement: Foot process effacement represents an adaptive change in cell shape. Many factors may influence the actin cytoskeleton, including hypertrophy of the contractile apparatus, thereby reinforcing the supportive role of podocytes, mesangial support, glomerular pressure or impairment of GBM substructure and of podocyte-GBM-contacts (Shirato et al., 1996). In response, the podocyte actin cytoskeletion may be altered from parallel contractile bundles into a dense actin network (Drenckhahn and Franke, 1988). Foot process effacement requires the active reorganization of actin filaments (Shirato, 2002, Takeda et al., 2001). Loss of the foot processes of podocytes is characteristic of minimal change nephrotic syndrome and is also seen in many glomerulopathies associated with heavy proteinuria (Shirato, 2002).

Apoptosis: In nephrotic syndrome, foot process effacement is considered to be an early manifestation, which may be followed by a continuum of progressive podocyte damage characterized by vacuolization, pseudocyst formation, detachment of podocytes from the GBM and, finally, irreversible loss of podocytes (Kerjaschki, 1994). An apparent lack of podocyte regeneration following cell loss allows the denuded GBM to come into contact with Bowman’s capsule, resulting in synechiae formation, and initiating the development of a focally sclerotic lesion (Griffin et al., 2003) (Kriz et al., 1998). Depletion of podocytes is one of the features in primary and secondary FSGS and may be mediated by a TGFβ - Smad, along with other signaling pathways (Schiffer et al., 2001).

Arrested development: The inability of differentiated podocytes to proliferate and repopulate the damaged glomerulus has been taken as a key factor in the progression of glomerular scarring (Kriz, 2003). In some cases, podocytes fail to complete maturation, accompanied by preserved proliferative activity, typical of immature phases of nephrogenesis. The glomeruli maintain an immature appearance with increased mesangial matrix, such as in diffuse mesangial sclerosis, as seen with WT-1 or PLCE1 defects (Barisoni et al., 2009). Based on the evidence that podocyte detachment from GBM was observed (Ng et al., 1984) and the degree of podocytopenia was related to the severity of glomerular dysfunction (Lemley et al., 2002) (Hara et al., 2007), the pathologic importance of podocytic injury has also been highlighted in IgA nephropathy, a disease characterized by mesangial proliferation and expansion (Lai et al., 2009).

Dedifferentiation: Podocytes originate from the metanephric mesenchyme and develop into postmitotic terminally differentiated epithelial cells (Kreidberg, 2003). In most glomerular diseases, podocytes do not proliferate (Mundel and Shankland, 2002) (Kriz et al., 1998). One exception is human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated nephropathy, in which podocytes may dedifferentiate, and proliferate (Barisoni et al., 1999), resulting in collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with proliferation of epithelial cells in Bowman's space. Injured podocytes regress to a more immature state and re-engage the cell cycle (Griffin et al., 2003, Nagata et al., 2003). Podocyte dysfunction appears to be a direct result of HIV-1 protein expression, specifically Nef and Vpr as well as specific host factors (Lu et al., 2007).

As mentioned, podocyte injury underlies most forms of proteinuric kidney diseases (Pippin et al., 2009). Based on the etiologic factors and morphologic features, Barisoni et al recently created a taxonomy of diseases with podocyte injury, termed podocytopathies. Each of these morphologic entities needs then to be classified according to etiology as idiopathic, genetically transmitted, or reactive/secondary. The taxonomy does not include the cellular lesion and tip lesion. They re-organized podocyte diseases into four major types, all of which are associated with variable degrees of foot process effacement (Barisoni et al., 2009):

Minimal change nephropathy, by definition with normal morphology on light microscopy and preserved podocyte number;

FSGS, defined by segmental solidification of the tuft, occasionally accompanied by hyalinosis, foam cells or adhesion to the Bowman capsule, and decreased number of podocytes;

Diffuse mesangial sclerosis, defined by the presence of mesangial sclerosis with or without mild mesangial proliferation, and mildly increased proliferative activity of podocytes;

Collapsing glomerulopathy, where by definition the glomerular damage and podocyte number is substantially increased with pseudocrescent formation.

This taxonomy includes more glomerular diseases associated with disorder of podocytes than previous classifications (Thomas, 2009).

No matter what is the initiating mechanism, podocyte injury is involved in many forms of glomerular disease. Compared with the single gene mutation-induced congenital podocyte diseases, the pathogenesis for acquired podocytopathies is more complex, since a variety of pathophysiological stimuli may induce or predispose to podocyte diseases, including the underlying genetic profile, immune-mediated stresses, metabolic derangements, drugs, toxins, infections, hemodynamic changes, growth factors, and cytokines, to name but a few. Acquired podocyte diseases in diabetic nephropathy, passive Heymann nephritis, puromycin aminonucleoside nephrosis, doxorubicin nephrosis, liopolysaccharide, crescentic glomerulonephritis, and protein overload nephropathy have been identified in rodent models (Pippin et al., 2009). Both genetic and environment factors may affect susceptibility to podocyte injury:

Gene variants or alterations in gene regulation: Altered podocyte gene expression has been identified in patients with various human renal diseases, including minimal change nephropathy, FSGS, IgA nephropathy, lupus nephritis, and diabetic nephropathy (Koop et al., 2003). In addition multiple studies have linked podocyte gene variants to altered expression in diverse sporadic nephropathies, although in both situations, it is still controversial whether these podocyte alterations are “causes” or “consequences” of podocyte injury. In some cases, the “second hit” or gene-gene and gene-environment interaction is essential for determination of complex nephropathy phenotypes (Papeta et al., 2009). For example, CD2AP haploinsufficient mice do not develop overt nephropathy but have increased susceptibility to experimental glomerular injury or develop nephropathy in conjunction with a null allele in either the synaptopodin gene or the Fyn proto-oncogene (Kim et al., 2003) (Huber et al., 2006). It has also been found that mice over-expressing COX-2 in podocytes were predisposed to injury by doxorubicin (adriamycin) (Cheng et al., 2007) or puromycin (Jo et al., 2007). A mendelian locus on chromosome 16 has been found to mediate susceptibility to doxorubicin nephropathy in mice (Zheng et al., 2005). Genetic susceptibility was also recognized in HIV-nephropathy (Rosenstiel et al., 2009). A survey of the podocyte transcriptional response to HIV1 associated nephropathy-predisposing alleles demonstrated the importance of underlying genotype and environment in interpreting the relationship of the gene expression profile to nephropathy (Papeta et al., 2009). In these circumstances, genetic susceptibility represents a compensated state that is unmasked upon exposure to additional genetic or environmental insults (Papeta et al., 2009).

Systemic and environmental insults: Recently Pippin et al. reviewed rodent models for acquired podocyte diseases that were induced by toxins and drugs (puromycin aminonucleoside, adriamycin, liopolysaccharide), immune alterations (both active and passive models) and protein overload (Pippin et al., 2009), suggesting a pathogenic role of environmental insults. Most components of the renin-angiotensin-system (RAS) exist in podocytes (Velez et al., 2007); podocytes are not only a local source of angiotensin II production, but are also a target for its deleterious effects (Durvasula and Shankland, 2006). In addition, altered RAS activity is a major mediator of hemodynamic influences on podocytes. Altered podocyte function is a characteristic of diabetic nephropathy (DN) (Kanwar et al., 2008) (Marshall, 2005) (Marshall, 2007. Hyperglycemia and haemodynamic abnormalities, oxidative stress are key factors underlying its pathogenesis. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) are heterogeneous groups of macromolecules that are normally formed non-enzymatically and their accumulation is implicated in the pathogenesis and progressive of DN (Bierhaus et al., 1998). Recently the AGEs receptor, RAGE, has been proposed as a biomarker and potential therapeutic target for DN (Ramasamy et al., 2009) (D'Agati et al., 2009). RAGE is a multi-ligand signal transduction receptor, belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily. In the kidney RAGE is highly expressed on normal podocytes and is up-regulated in diabetic nephropathy, especially on podocytes (Tanji et al., 2000). RAGE does not promote the uptake and removal of AGE, but AGE-ligation to RAGE induces inflammation through persistent activation of the proinflammatory transcription factor, nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) (Bierhaus et al., 2005, Bierhaus and Nawroth, 2009). Protective effects of RAGE blockade or knockdown have been shown in diabetic animal models (Wendt et al., 2003) (Tan et al., 2007).

In response to patho-physiological stimuli, glomerular mesangial cells, podocytes and endothelial cells may undergo proliferation, de-differentiation, hypertrophy, senescence, apoptosis or necrosis. No matter where the injury initiated, these cells might crosstalk to each other during the disease progression. Here we will concentrate on the interaction between podocytes and endothelial or mesangial cells:

-

Podocytes and endothelial cells: In situ hybridization and immunohistochemical analyses define the podocyte as the site of glomerular VEGF production in vivo, while both glomerular endothelial cells and podocytes express VEGF receptors (Cui et al., 2004). VEGF (more accurately, its important subtype: VEGF-A) appears to be critical for the maintenance of capillary integrity, particularly in the glomerulus. In normal animals, systemic blockade of VEGF-A action is associated with endothelial cell damage, reduced nephrin expression and proteinuria (Sugimoto et al., 2003). VEGF-A is essential for kidney development, and loss of even one of the VEGF-A alleles in podocytes leads to glomerular capillary endothelial cell dysfunction and proteinuria. In contrast, podocyte over-expression of the longer splice VEGF A isoform, mouse VEGF 164, which contains a highly basic heparin-binding domain, leads to collapsing glomerulopathy and renal failure (Eremina et al., 2003). Up-regulated VEGF-A was reported in diabetes, and blockade of VEGF signaling ameliorates diabetic albuminuria in mice (Sung et al., 2006). Therefore, both deficiency and excess of VEGF appear to be detrimental to the physiological integrity of glomerular capillaries. Paracrine VEGF-A signaling occurs between podocytes and adjacent endothelial and mesangial cells, which express VEGF receptors 1 and 2 (Ferrara et al., 2003). Immuno-gold electron microscopic studies showed a clear concentration gradient of labeled VEGF particles from glomerulus to endothelial cells, with VEGF being clearly apparent on the endothelial side of the glomerular barrier (Guan et al., 2006). Recently Eremina et al reported that six patients treated with bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal VEGF antibody developed glomerular disease characteristic of thrombotic microangiopathy (Eremina et al., 2008). This study along with the identical histological lesion induced by podocyte-specific deletion of VEGF in adult mice (Eremina et al., 2008) provides robust evidence for the effects of podocyte-derived VEGF on the adjacent glomerular endothelium in the mature glomerulus.

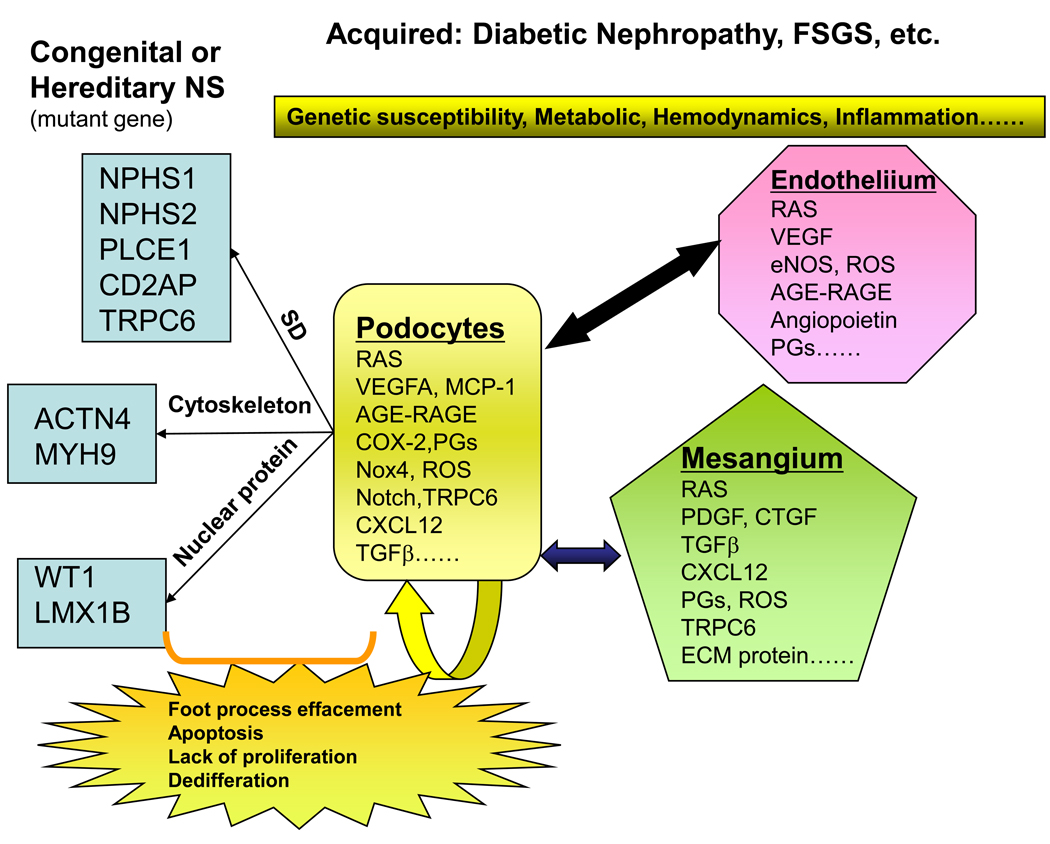

VEGF could be a potential activator of transient receptor potential ion channel (TRPC) (Schlondorff and Pollak, 2006), since it may induce the TRPC dependent calcium influx into endothelial cells and change in vascular permeability (Jho et al., 2005). Both podocytes and endothelial cells have angiotensin (AT) 1 and 2 receptors and RAGE. Angiotensin II signaling, AGE–RAGE interaction and ROS generation can stimulate podocyte VEGF mRNA expression (Okamoto et al., 2002) (Wendt et al., 2003). A number of other factors in the podocyte, such Nox4 (Brown and Griendling, 2009), Notch (Niranjan et al., 2009), CXCL12 (Sayyed et al., 2009), MCP-1 (Tesch, 2008), TGFβ (Barisoni and Mundel, 2003) and COX-2/prostaglandins (Pavenstadt, 2000) etc. are also potential candidates in mediating and signaling this interaction (Fig. 1).

Podocytes and mesangial cells: Three-dimensional reconstruction of glomeruli by electron microscopy provided physiologic evidence for “back-flow” across the GBM by increased renal perfusion pressure, which implied that growth factors and cytokines produced by the podocyte can access receptors on endothelial and mesangial cells (Neal et al., 2005) (D'Agati et al., 2009, Salmon et al., 2009). It has been shown that mesangial cells bear RAGE and VEGF and angiotensin receptors, especially under pathologic conditions. VEGF is also required for mesangial cell migration and survival (Eremina et al., 2006). There is evidence that the TGFβ -induced secretion of connective tissue growth factor and VEGF by podocytes acts as a paracrine regulatory mechanism on mesangial cells, which may cause mesangial matrix accumulation culminating in the development of glomerulosclerosis (Lee and Song, 2009). Podocyte-derived ROS and local podocyte RAS activation may also promote injury. On the other hand, TGFβ secreted as latent complexes by mesangial cells is stored in the mesangial matrix, from which soluble forms of latent TGFβ are released and localized to the podocyte surface in chronic glomerular disease (Lee and Song, 2009). Numerous mediators/pathway may be involved in both podocytes and mesangial cells injury in response to hyperglycemia or glomerular hypertension, and they may contribute to the “crosstalk” between those cell types (Gruden et al., 2005).

Fig. 1.

Podocyte disorders in hereditary and acquired proteinuria syndromes. Representative mutations linked to hereditary proteinuria syndromes are shown in the left. An individual’s genetic profile may lead to an increased susceptibility to development of podocyte diseases; environmental factors, including metabolic, homodynamic, immune, infection and inflammatory alterations, could trigger the onset of the diseases. Injured podocytes could spread injury to the healthy ones and other adjacent/ distant cells, like endothelial and mesangial cells in a vicious cycle. Many molecules/proteins are involved in the “cross-talk” between cells during the disease progression. Injured podocytes may have foot process effacement and slit diaphragm alterations as an early manifestation of injury and subsequently undergo detachment, apoptosis, impaired proliferation and de-differentiation.

SD: Slit diaphragm complex; RAS: renin-angiotensin system; AGE: Advanced glycation end-products; RAGE: receptor for AGEs; PGs: prostaglandins; ECM: extracellular matrix; FSGS: focal segmental glomerular sclerosis; NS: nephrotic syndrome.

4. CAN PODOCYTES BE REPAIRED?

Since the process from podocyte injury to sclerosis can be remarkably rapid, and the rate of progression depends upon the degree of initial podocyte injury (Ichikawa et al., 2005), exploration of novel therapeutic strategies to block this vicious cycle and enhance podocyte survival seems imperative. In the mature glomerulus, podocytes have a low level of DNA synthesis and do not readily proliferate under normal conditions (Marshall and Shankland, 2005). Traditionally podocyte proliferation is not considered to be a viable repair mechanism, although the ability to regenerate foot process architecture is an important component of repair in glomerular diseases (Quaggin and Kreidberg, 2008). Recent studies have raised the possibility that a population of stem cells might differentiate into, and replace, podocytes lost during injury or with normal aging. There is no evidence for one master stem cell in the kidney that can recapitulate development of all cell types (Little and Bertram, 2009). Although rare bone marrow-derived cells have been identified in the periphery of the glomerular tuft, there is not compelling evidence at present that bone marrow-derived stem cells play a significant role to repopulate the podocytes directly, and it has been argued that these cells simply act on an existing endogenous cell population, potentially a renal stem cell population, to repair renal architecture and function (Little and Bertram, 2009). Bussolati et al. (Bussolati et al., 2005) isolated potential progenitors from adult human kidney on the basis of expression of the stem cell marker CD133. Rodent research using careful immunohistochemistry and a transgenic animal model that differentially tagged the parietal epithelium vs. the glomerular visceral epithelium indicated the presence within the Bowman's capsule of podocyte progenitor cells that migrate over the basement membrane of the Bowman's capsule to ensure a constant re-supply of podocytes (Appel et al., 2009). Ronconi et al. isolated a CD133+, CD24+ population of cells from the Bowman's capsule of human kidneys and showed, upon reintroduction into an immuno-deficient animal model of renal damage, these cells contribute both to podocytes and to tubular epithelium. However, there is no definitive proof in either of these studies that these cells represent stem cells. Neither is there yet proof that podocyte localization in recipient xenotransplants is not due to fusion. However, these exciting results indicating that they are responsible for podocyte turnover is a revelation in nephrology (Ronconi et al., 2009, Sagrinati et al., 2006).

5. CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVE

In the past decade, there has been enormous progress in understanding the physiologic and pathophysiologic function of the podocyte. Development of powerful new molecular, cellular and animal tools has greatly enhanced our knowledge of podocyte biology and increased our understanding of underlying mechanisms of podocyte diseases. Podocytes are no longer considered to be simply a passive target but can also be a mediator of continuing glomerular injury (Fig.1). Finally, although highly differentiated podocytes have limited proliferative capacity under normal conditions, new experimental findings suggest a potential role in podocyte regeneration by progenitor cells residing within the Bowman's capsule, which may open a new era for the treatment of chronic glomerular diseases.

Cell facts

Podocytes are highly differentiated cells with a unique architecture that includes a cell body, major processes and foot processes bridged by slit diaphragms (SD).

Mutations in podocyte components are associated with hereditary renal diseases.

Podocyte disorders also play a crucial role in a broad spectrum of acquired glomerular diseases.

A potential role for podocyte regeneration may open a new era for the treatment of chronic glomerular diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This work was supported by funds from National Institutes of Health Grant DK38226, DK51265, DK62794 and DK79341 and funds from the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akilesh S, Huber TB, Wu H, Wang G, Hartleben B, Kopp JB, Miner JH, Roopenian DC, Unanue ER, Shaw AS. Podocytes use FcRn to clear IgG from the glomerular basement membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(3):967–972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711515105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appel D, Kershaw DB, Smeets B, Yuan G, Fuss A, Frye B, Elger M, Kriz W, Floege J, Moeller MJ. Recruitment of podocytes from glomerular parietal epithelial cells. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(2):333–343. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrondel C, Vodovar N, Knebelmann B, Grunfeld JP, Gubler MC, Antignac C, Heidet L. Expression of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain IIA in the human kidney and screening for MYH9 mutations in Epstein and Fechtner syndromes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(1):65–74. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V13165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Campbell KN, Kim K, Faul C, Mundel P. Nuclear relocation of the nephrin and CD2AP-binding protein dendrin promotes apoptosis of podocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(24):10134–10139. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700917104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Kim K, Oh J, Giardino L, Chabanis S, Faul C, Reiser J, Mundel P. Synaptopodin regulates the actin-bundling activity of alpha-actinin in an isoform-specific manner. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(5):1188–1198. doi: 10.1172/JCI23371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanuma K, Mundel P. The role of podocytes in glomerular pathobiology. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2003;7(4):255–259. doi: 10.1007/s10157-003-0259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbaux S, Niaudet P, Gubler MC, Grunfeld JP, Jaubert F, Kuttenn F, Fekete CN, Souleyreau-Therville N, Thibaud E, Fellous M, McElreavey K. Donor splice-site mutations in WT1 are responsible for Frasier syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17(4):467–470. doi: 10.1038/ng1297-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisoni L, Kriz W, Mundel P, D'Agati V. The dysregulated podocyte phenotype: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of collapsing idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(1):51–61. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisoni L, Mundel P. Podocyte biology and the emerging understanding of podocyte diseases. Am J Nephrol. 2003;23(5):353–360. doi: 10.1159/000072917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barisoni L, Schnaper HW, Kopp JB. Advances in the biology and genetics of the podocytopathies: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(2):201–216. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.2.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzing T. Signaling at the slit diaphragm. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(6):1382–1391. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000130167.30769.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierhaus A, Hofmann MA, Ziegler R, Nawroth PP. AGEs and their interaction with AGE-receptors in vascular disease and diabetes mellitus. I. The AGE concept. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37(3):586–600. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierhaus A, Humpert PM, Morcos M, Wendt T, Chavakis T, Arnold B, Stern DM, Nawroth PP. Understanding RAGE, the receptor for advanced glycation end products. J Mol Med. 2005;83(11):876–886. doi: 10.1007/s00109-005-0688-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierhaus A, Nawroth PP. Multiple levels of regulation determine the role of the receptor for AGE (RAGE) as common soil in inflammation, immune responses and diabetes mellitus and its complications. Diabetologia. 2009;52(11):2251–2263. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1458-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boute N, Gribouval O, Roselli S, Benessy F, Lee H, Fuchshuber A, Dahan K, Gubler MC, Niaudet P, Antignac C. NPHS2, encoding the glomerular protein podocin, is mutated in autosomal recessive steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. Nat Genet. 2000;24(4):349–354. doi: 10.1038/74166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DI, Griendling KK. Nox proteins in signal transduction. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussolati B, Bruno S, Grange C, Buttiglieri S, Deregibus MC, Cantino D, Camussi G. Isolation of renal progenitor cells from adult human kidney. Am J Pathol. 2005;166(2):545–555. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62276-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaib H, Hoskins BE, Ashraf S, Goyal M, Wiggins RC, Hildebrandt F. Identification of BRAF as a new interactor of PLCepsilon1, the protein mutated in nephrotic syndrome type 3. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294(1):F93–F99. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00345.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Lun Y, Ovchinnikov D, Kokubo H, Oberg KC, Pepicelli CV, Gan L, Lee B, Johnson RL. Limb and kidney defects in Lmx1b mutant mice suggest an involvement of LMX1B in human nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19(1):51–55. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H, Wang S, Jo YI, Hao CM, Zhang M, Fan X, Kennedy C, Breyer MD, Moeckel GW, Harris RC. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 predisposes to podocyte injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(2):551–559. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006090990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chugh SS. Transcriptional regulation of podocyte disease. Transl Res. 2007;149(5):237–242. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui TG, Foster RR, Saleem M, Mathieson PW, Gillatt DA, Bates DO, Harper SJ. Differentiated human podocytes endogenously express an inhibitory isoform of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF165b) mRNA and protein. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286(4):F767–F773. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00337.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agati V, Yan SF, Ramasamy R, Schmidt AM. RAGE, glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria: Roles in podocytes and endothelial cells. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drenckhahn D, Franke RP. Ultrastructural organization of contractile and cytoskeletal proteins in glomerular podocytes of chicken, rat, and man. Lab Invest. 1988;59(5):673–682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyer SD, Zhou G, Baldini A, Winterpacht A, Zabel B, Cole W, Johnson RL, Lee B. Mutations in LMX1B cause abnormal skeletal patterning and renal dysplasia in nail patella syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;19(1):47–50. doi: 10.1038/ng0598-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durvasula RV, Shankland SJ. The renin-angiotensin system in glomerular podocytes: mediator of glomerulosclerosis and link to hypertensive nephropathy. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2006;8(2):132–138. doi: 10.1007/s11906-006-0009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endlich N, Endlich K. Stretch, tension and adhesion - adaptive mechanisms of the actin cytoskeleton in podocytes. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85(3–4):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremina V, Baelde HJ, Quaggin SE. Role of the VEGF--a signaling pathway in the glomerulus: evidence for crosstalk between components of the glomerular filtration barrier. Nephron Physiol. 2007;106(2):32–37. doi: 10.1159/000101798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremina V, Cui S, Gerber H, Ferrara N, Haigh J, Nagy A, Ema M, Rossant J, Jothy S, Miner JH, Quaggin SE. Vascular endothelial growth factor a signaling in the podocyte-endothelial compartment is required for mesangial cell migration and survival. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(3):724–735. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremina V, Jefferson JA, Kowalewska J, Hochster H, Haas M, Weisstuch J, Richardson C, Kopp JB, Kabir MG, Backx PH, Gerber HP, Ferrara N, Barisoni L, Alpers CE, Quaggin SE. VEGF inhibition and renal thrombotic microangiopathy. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1129–1136. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eremina V, Sood M, Haigh J, Nagy A, Lajoie G, Ferrara N, Gerber HP, Kikkawa Y, Miner JH, Quaggin SE. Glomerular-specific alterations of VEGF-A expression lead to distinct congenital and acquired renal diseases. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(5):707–716. doi: 10.1172/JCI17423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre J, Ioannou K, Grubb BD, Saleem MA, Mathieson PW, Brunskill NJ, Christensen EI, Topham PS. Statin-sensitive endocytosis of albumin by glomerular podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;292(2):F674–F681. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00272.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul C, Asanuma K, Yanagida-Asanuma E, Kim K, Mundel P. Actin up: regulation of podocyte structure and function by components of the actin cytoskeleton. Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17(9):428–437. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N, Gerber HP, LeCouter J. The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):669–676. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg P, Verma R, Holzman LB. Slit diaphragm junctional complex and regulation of the cytoskeleton. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2007;106(2):e67–e72. doi: 10.1159/000101795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gbadegesin R, Bartkowiak B, Lavin PJ, Mukerji N, Wu G, Bowling B, Eckel J, Damodaran T, Winn MP. Exclusion of homozygous PLCE1 (NPHS3) mutations in 69 families with idiopathic and hereditary FSGS. Pediatr Nephrol. 2009;24(2):281–285. doi: 10.1007/s00467-008-1025-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SV, Petermann AT, Durvasula RV, Shankland SJ. Podocyte proliferation and differentiation in glomerular disease: role of cell-cycle regulatory proteins. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18 Suppl 6:vi8–vi13. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruden G, Perin PC, Camussi G. Insight on the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy from the study of podocyte and mesangial cell biology. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1(1):27–40. doi: 10.2174/1573399052952622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan F, Villegas G, Teichman J, Mundel P, Tufro A. Autocrine VEGF-A system in podocytes regulates podocin and its interaction with CD2AP. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291(2):F422–F428. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00448.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hara M, Yanagihara T, Kihara I. Cumulative excretion of urinary podocytes reflects disease progression in IgA nephropathy and Schonlein-Henoch purpura nephritis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;2(2):231–238. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01470506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkes B, Wiggins RC, Gbadegesin R, Vlangos CN, Seelow D, Nurnberg G, Garg P, Verma R, Chaib H, Hoskins BE, Ashraf S, Becker C, Hennies HC, Goyal M, Wharram BL, Schachter AD, Mudumana S, Drummond I, Kerjaschki D, Waldherr R, Dietrich A, Ozaltin F, Bakkaloglu A, Cleper R, Basel-Vanagaite L, Pohl M, Griebel M, Tsygin AN, Soylu A, Muller D, Sorli CS, Bunney TD, Katan M, Liu J, Attanasio M, O'Toole JF, Hasselbacher K, Mucha B, Otto EA, Airik R, Kispert A, Kelley GG, Smrcka AV, Gudermann T, Holzman LB, Nurnberg P, Hildebrandt F. Positional cloning uncovers mutations in PLCE1 responsible for a nephrotic syndrome variant that may be reversible. Nat Genet. 2006;38(12):1397–1405. doi: 10.1038/ng1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber TB, Benzing T. The slit diaphragm: a signaling platform to regulate podocyte function. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14(3):211–216. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000165885.85803.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber TB, Kwoh C, Wu H, Asanuma K, Godel M, Hartleben B, Blumer KJ, Miner JH, Mundel P, Shaw AS. Bigenic mouse models of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis involving pairwise interaction of CD2AP, Fyn, and synaptopodin. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(5):1337–1345. doi: 10.1172/JCI27400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa I, Ma J, Motojima M, Matsusaka T. Podocyte damage damages podocytes: autonomous vicious cycle that drives local spread of glomerular sclerosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2005;14(3):205–210. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000165884.85803.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichimura K, Kurihara H, Sakai T. Actin filament organization of foot processes in rat podocytes. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51(12):1589–1600. doi: 10.1177/002215540305101203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Yaoita E, Kurihara H, Shimizu F, Sakai T, Kobayashi T, Ohshiro K, Kawachi H, Okada H, Suzuki H, Kihara I, Yamamoto T. FAT is a component of glomerular slit diaphragms. Kidney Int. 2001;59(3):1003–1012. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.0590031003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jalanko H, Patrakka J, Tryggvason K, Holmberg C. Genetic kidney diseases disclose the pathogenesis of proteinuria. Ann Med. 2001;33(8):526–533. doi: 10.3109/07853890108995962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeanpierre C, Denamur E, Henry I, Cabanis MO, Luce S, Cecille A, Elion J, Peuchmaur M, Loirat C, Niaudet P, Gubler MC, Junien C. Identification of constitutional WT1 mutations, in patients with isolated diffuse mesangial sclerosis, and analysis of genotype/phenotype correlations by use of a computerized mutation database. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(4):824–833. doi: 10.1086/301806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jho D, Mehta D, Ahmmed G, Gao XP, Tiruppathi C, Broman M, Malik AB. Angiopoietin-1 opposes VEGF-induced increase in endothelial permeability by inhibiting TRPC1-dependent Ca2 influx. Circ Res. 2005;96(12):1282–1290. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000171894.03801.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YI, Cheng H, Wang S, Moeckel GW, Harris RC. Puromycin Induces Reversible Proteinuric Injury in Transgenic Mice Expressing Cyclooxygenase-2 in Podocytes. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2007;107(3):e87–e94. doi: 10.1159/000108653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanwar YS, Wada J, Sun L, Xie P, Wallner EI, Chen S, Chugh S, Danesh FR. Diabetic nephropathy: mechanisms of renal disease progression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2008;233(1):4–11. doi: 10.3181/0705-MR-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao WH, Klag MJ, Meoni LA, Reich D, Berthier-Schaad Y, Li M, Coresh J, Patterson N, Tandon A, Powe NR, Fink NE, Sadler JH, Weir MR, Abboud HE, Adler SG, Divers J, Iyengar SK, Freedman BI, Kimmel PL, Knowler WC, Kohn OF, Kramp K, Leehey DJ, Nicholas SB, Pahl MV, Schelling JR, Sedor JR, Thornley-Brown D, Winkler CA, Smith MW, Parekh RS. MYH9 is associated with nondiabetic end-stage renal disease in African Americans. Nat Genet. 2008;40(10):1185–1192. doi: 10.1038/ng.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JM, Kim SH, North KN, Rennke H, Correia LA, Tong HQ, Mathis BJ, Rodriguez-Perez JC, Allen PG, Beggs AH, Pollak MR. Mutations in ACTN4, encoding alpha-actinin-4, cause familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat Genet. 2000;24(3):251–256. doi: 10.1038/73456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerjaschki D. Dysfunctions of cell biological mechanisms of visceral epithelial cell (podocytes) in glomerular diseases. Kidney Int. 1994;45(2):300–313. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kestila M, Lenkkeri U, Mannikko M, Lamerdin J, McCready P, Putaala H, Ruotsalainen V, Morita T, Nissinen M, Herva R, Kashtan CE, Peltonen L, Holmberg C, Olsen A, Tryggvason K. Positionally cloned gene for a novel glomerular protein--nephrin--is mutated in congenital nephrotic syndrome. Mol Cell. 1998;1(4):575–582. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JM, Wu H, Green G, Winkler CA, Kopp JB, Miner JH, Unanue ER, Shaw AS. CD2-associated protein haploinsufficiency is linked to glomerular disease susceptibility. Science. 2003;300(5623):1298–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.1081068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koop K, Eikmans M, Baelde HJ, Kawachi H, De Heer E, Paul LC, Bruijn JA. Expression of podocyte-associated molecules in acquired human kidney diseases. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(8):2063–2071. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000078803.53165.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kos CH, Le TC, Sinha S, Henderson JM, Kim SH, Sugimoto H, Kalluri R, Gerszten RE, Pollak MR. Mice deficient in alpha-actinin-4 have severe glomerular disease. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(11):1683–1690. doi: 10.1172/JCI17988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreidberg JA. Podocyte differentiation and glomerulogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(3):806–814. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000054887.42550.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz W. Progression of chronic renal failure in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: consequence of podocyte damage or of tubulointerstitial fibrosis? Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(7):617–622. doi: 10.1007/s00467-003-1172-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz W, Gretz N, Lemley KV. Progression of glomerular diseases: is the podocyte the culprit? Kidney Int. 1998;54(3):687–697. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara H, Anderson JM, Farquhar MG. Diversity among tight junctions in rat kidney: glomerular slit diaphragms and endothelial junctions express only one isoform of the tight junction protein ZO-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89(15):7075–7079. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.7075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai KN, Leung JC, Chan LY, Saleem MA, Mathieson PW, Tam KY, Xiao J, Lai FM, Tang SC. Podocyte injury induced by mesangial-derived cytokines in IgA nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24(1):62–72. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Song CY. Differential role of mesangial cells and podocytes in TGF-beta-induced mesangial matrix synthesis in chronic glomerular disease. Histol Histopathol. 2009;24(7):901–908. doi: 10.14670/HH-24.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemley KV, Lafayette RA, Safai M, Derby G, Blouch K, Squarer A, Myers BD. Podocytopenia and disease severity in IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2002;61(4):1475–1485. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little MH, Bertram JF. Is there such a thing as a renal stem cell? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(10):2112–2117. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009010066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowik MM, Groenen PJ, Levtchenko EN, Monnens LA, van den Heuvel LP. Molecular genetic analysis of podocyte genes in focal segmental glomerulosclerosis--a review. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168(11):1291–1304. doi: 10.1007/s00431-009-1017-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu TC, He JC, Klotman PE. Podocytes in HIV-associated nephropathy. Nephron Clin Pract. 2007;106(2):c67–c71. doi: 10.1159/000101800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machuca E, Benoit G, Antignac C. Genetics of nephrotic syndrome: connecting molecular genetics to podocyte physiology. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18(R2):R185–R194. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall CB, Shankland SJ. Cell Cycle and Glomerular Disease: A Minireview. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2005;102(2):e39–e48. doi: 10.1159/000088400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SM. The podocyte: a major player in the development of diabetic nephropathy? Horm Metab Res. 2005;37 Suppl 1:9–16. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall SM. The podocyte: a potential therapeutic target in diabetic nephropathy? Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(26):2713–2720. doi: 10.2174/138161207781662957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieson PW. Update on the podocyte. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(3):206–211. doi: 10.1097/mnh.0b013e328326f3ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh I, Dreyer SD, Clough MV, Dunston JA, Eyaid W, Roig CM, Montgomery T, Ala-Mello S, Kaitila I, Winterpacht A, Zabel B, Frydman M, Cole WG, Francomano CA, Lee B. Mutation analysis of LMX1B gene in nail-patella syndrome patients. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63(6):1651–1658. doi: 10.1086/302165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud JL, Lemieux LI, Dube M, Vanderhyden BC, Robertson SJ, Kennedy CR. Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis in Mice with Podocyte-Specific Expression of Mutant alpha-Actinin-4. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1200–1211. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000059864.88610.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH. Glomerular filtration: the charge debate charges ahead. Kidney Int. 2008;74(3):259–261. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller CC, Pollak MR, Reiser J. The genetic basis of human glomerular disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2006;13(2):166–173. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2006.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell C. The TRP superfamily of cation channels. Sci STKE. 2005;2005(272) doi: 10.1126/stke.2722005re3. re3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morello R, Lee B. Insight into podocyte differentiation from the study of human genetic disease: nail-patella syndrome and transcriptional regulation in podocytes. Pediatr Res. 2002;51(5):551–558. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200205000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Kriz W. Structure and function of podocytes: an update. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1995;192(5):385–397. doi: 10.1007/BF00240371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Reiser J, Kriz W. Induction of differentiation in cultured rat and human podocytes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8(5):697–705. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V85697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Reiser J, Zuniga Mejia Borja A, Pavenstadt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W, Zeller R. Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1997;236(1):248–258. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mundel P, Shankland SJ. Podocyte biology and response to injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(12):3005–3015. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000039661.06947.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata M, Tomari S, Kanemoto K, Usui J, Lemley KV. Podocytes, parietal cells, and glomerular pathology: the role of cell cycle proteins. Pediatr Nephrol. 2003;18(1):3–8. doi: 10.1007/s00467-002-0995-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal CR, Crook H, Bell E, Harper SJ, Bates DO. Three-dimensional reconstruction of glomeruli by electron microscopy reveals a distinct restrictive urinary subpodocyte space. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(5):1223–1235. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal CR, Muston PR, Njegovan D, Verrill R, Harper SJ, Deen WM, Bates DO. Glomerular filtration into the subpodocyte space is highly restricted under physiological perfusion conditions. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(6):F1787–F1798. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00157.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng WL, Chan KW, Yeung CK, Kwan S. Peripheral glomerular capillary wall lesions in IgA nephropathy and their implications. Pathology. 1984;16(3):324–330. doi: 10.3109/00313028409068545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niranjan T, Murea M, Susztak K. The pathogenic role of notch activation in podocytes. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2009;111(4):e73–e79. doi: 10.1159/000209207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto T, Yamagishi S, Inagaki Y, Amano S, Koga K, Abe R, Takeuchi M, Ohno S, Yoshimura A, Makita Z. Angiogenesis induced by advanced glycation end products and its prevention by cerivastatin. FASEB J. 2002;16(14):1928–1930. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0030fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orloff MS, Iyengar SK, Winkler CA, Goddard KA, Dart RA, Ahuja TS, Mokrzycki M, Briggs WA, Korbet SM, Kimmel PL, Simon EE, Trachtman H, Vlahov D, Michel DM, Berns JS, Smith MC, Schelling JR, Sedor JR, Kopp JB. Variants in the Wilms' tumor gene are associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis in the African American population. Physiol Genomics. 2005;21(2):212–221. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00201.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papeta N, Chan KT, Prakash S, Martino J, Kiryluk K, Ballard D, Bruggeman LA, Frankel R, Zheng Z, Klotman PE, Zhao H, D'Agati VD, Lifton RP, Gharavi AG. Susceptibility loci for murine HIV-associated nephropathy encode trans-regulators of podocyte gene expression. J Clin Invest. 2009;119(5):1178–1188. doi: 10.1172/JCI37131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parast MM, Otey CA. Characterization of palladin, a novel protein localized to stress fibers and cell adhesions. J Cell Biol. 2000;150(3):643–656. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavenstadt H. Roles of the podocyte in glomerular function. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2000;278(2):F173–F179. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2000.278.2.F173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pippin JW, Brinkkoetter PT, Cormack-Aboud FC, Durvasula RV, Hauser PV, Kowalewska J, Krofft RD, Logar CM, Marshall CB, Ohse T, Shankland SJ. Inducible rodent models of acquired podocyte diseases. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2009;296(2):F213–F229. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90421.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaggin SE, Kreidberg JA. Development of the renal glomerulus: good neighbors and good fences. Development. 2008;135(4):609–620. doi: 10.1242/dev.001081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy R, Yan SF, Schmidt AM. RAGE: therapeutic target and biomarker of the inflammatory response--the evidence mounts. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(3):505–512. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0409230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol. 2006;68:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.68.040204.100431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser J, Kriz W, Kretzler M, Mundel P. The glomerular slit diaphragm is a modified adherens junction. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(1):1–8. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser J, Polu KR, Moller CC, Kenlan P, Altintas MM, Wei C, Faul C, Herbert S, Villegas I, Avila-Casado C, McGee M, Sugimoto H, Brown D, Kalluri R, Mundel P, Smith PL, Clapham DE, Pollak MR. TRPC6 is a glomerular slit diaphragm-associated channel required for normal renal function. Nat Genet. 2005;37(7):739–744. doi: 10.1038/ng1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohr C, Prestel J, Heidet L, Hosser H, Kriz W, Johnson RL, Antignac C, Witzgall R. The LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Lmx1b plays a crucial role in podocytes. J Clin Invest. 2002;109(8):1073–1082. doi: 10.1172/JCI13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronconi E, Sagrinati C, Angelotti ML, Lazzeri E, Mazzinghi B, Ballerini L, Parente E, Becherucci F, Gacci M, Carini M, Maggi E, Serio M, Vannelli GB, Lasagni L, Romagnani S, Romagnani P. Regeneration of glomerular podocytes by human renal progenitors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(2):322–332. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008070709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenstiel P, Gharavi A, D'Agati V, Klotman P. Transgenic and infectious animal models of HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20(11):2296–2304. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostgaard J, Qvortrup K. Electron microscopic demonstrations of filamentous molecular sieve plugs in capillary fenestrae. Microvasc Res. 1997;53(1):1–13. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1996.1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagrinati C, Netti GS, Mazzinghi B, Lazzeri E, Liotta F, Frosali F, Ronconi E, Meini C, Gacci M, Squecco R, Carini M, Gesualdo L, Francini F, Maggi E, Annunziato F, Lasagni L, Serio M, Romagnani S, Romagnani P. Isolation and characterization of multipotent progenitor cells from the Bowman's capsule of adult human kidneys. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(9):2443–2456. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem MA, O'Hare MJ, Reiser J, Coward RJ, Inward CD, Farren T, Xing CY, Ni L, Mathieson PW, Mundel P. A conditionally immortalized human podocyte cell line demonstrating nephrin and podocin expression. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13(3):630–638. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salmon AH, Neal CR, Harper SJ. New aspects of glomerular filtration barrier structure and function: five layers (at least) not three. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(3):197–205. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e328329f837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato U, Kitanaka S, Sekine T, Takahashi S, Ashida A, Igarashi T. Functional characterization of LMX1B mutations associated with nail-patella syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2005;57(6):783–788. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000157674.63621.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayyed SG, Hagele H, Kulkarni OP, Endlich K, Segerer S, Eulberg D, Klussmann S, Anders HJ. Podocytes produce homeostatic chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCL12, which contributes to glomerulosclerosis, podocyte loss and albuminuria in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52(11):2445–2454. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1493-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer M, Bitzer M, Roberts IS, Kopp JB, ten Dijke P, Mundel P, Bottinger EP. Apoptosis in podocytes induced by TGF-beta and Smad7. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(6):807–816. doi: 10.1172/JCI12367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlondorff JS, Pollak MR. TRPC6 in glomerular health and disease: what we know and what we believe. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2006;17(6):667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seri M, Cusano R, Gangarossa S, Caridi G, Bordo D, Lo Nigro C, Ghiggeri GM, Ravazzolo R, Savino M, Del Vecchio M, d'Apolito M, Iolascon A, Zelante LL, Savoia A, Balduini CL, Noris P, Magrini U, Belletti S, Heath KE, Babcock M, Glucksman MJ, Aliprandis E, Bizzaro N, Desnick RJ, Martignetti JA. Mutations in MYH9 result in the May-Hegglin anomaly, and Fechtner and Sebastian syndromes. The May-Heggllin/Fechtner Syndrome Consortium. Nat Genet. 2000;26(1):103–105. doi: 10.1038/79063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankland SJ. The podocyte's response to injury: Role in proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis. Kidney Int. 2006;69(12):2131–2147. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankland SJ, Pippin JW, Reiser J, Mundel P. Podocytes in culture: past, present, and future. Kidney Int. 2007;72(1):26–36. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih NY, Li J, Karpitskii V, Nguyen A, Dustin ML, Kanagawa O, Miner JH, Shaw AS. Congenital nephrotic syndrome in mice lacking CD2-associated protein. Science. 1999;286(5438):312–315. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato I. Podocyte process effacement in vivo. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;57(4):241–246. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirato I, Sakai T, Kimura K, Tomino Y, Kriz W. Cytoskeletal changes in podocytes associated with foot process effacement in Masugi nephritis. Am J Pathol. 1996;148(4):1283–1296. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons M, Hartleben B, Huber TB. Podocyte polarity signalling. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2009;18(4):324–330. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e32832e316d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srichai MB, Konieczkowski M, Padiyar A, Konieczkowski DJ, Mukherjee A, Hayden PS, Kamat S, El-Meanawy MA, Khan S, Mundel P, Lee SB, Bruggeman LA, Schelling JR, Sedor JR. A WT1 co-regulator controls podocyte phenotype by shuttling between adhesion structures and nucleus. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(14):14398–14408. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314155200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto H, Hamano Y, Charytan D, Cosgrove D, Kieran M, Sudhakar A, Kalluri R. Neutralization of circulating vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by anti-VEGF antibodies and soluble VEGF receptor 1 (sFlt-1) induces proteinuria. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(15):12605–12608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C300012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung SH, Ziyadeh FN, Wang A, Pyagay PE, Kanwar YS, Chen S. Blockade of vascular endothelial growth factor signaling ameliorates diabetic albuminuria in mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(11):3093–3104. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006010064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda T, McQuistan T, Orlando RA, Farquhar MG. Loss of glomerular foot processes is associated with uncoupling of podocalyxin from the actin cytoskeleton. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(2):289–301. doi: 10.1172/JCI12539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan AL, Forbes JM, Cooper ME. AGE, RAGE, and ROS in diabetic nephropathy. Semin Nephrol. 2007;27(2):130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanji N, Markowitz GS, Fu C, Kislinger T, Taguchi A, Pischetsrieder M, Stern D, Schmidt AM, D'Agati VD. Expression of advanced glycation end products and their cellular receptor RAGE in diabetic nephropathy and nondiabetic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(9):1656–1666. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1191656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesch GH. MCP-1/CCL2: a new diagnostic marker and therapeutic target for progressive renal injury in diabetic nephropathy. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2008;294(4):F697–F701. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00016.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DB. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis: a morphologic diagnosis in evolution. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(2):217–223. doi: 10.5858/133.2.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiruppathi C, Minshall RD, Paria BC, Vogel SM, Malik AB. Role of Ca2+ signaling in the regulation of endothelial permeability. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;39(4–5):173–185. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(03)00007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tryggvason K, Patrakka J, Wartiovaara J. Hereditary proteinuria syndromes and mechanisms of proteinuria. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(13):1387–1401. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez JC, Bland AM, Arthur JM, Raymond JR, Janech MG. Characterization of renin-angiotensin system enzyme activities in cultured mouse podocytes. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2007;293(1):F398–F407. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00050.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath D, Jaramillo-Babb VL, Clough MV, McIntosh I, Scott KM, Lichter PR, Richards JE. Loss-of-function mutations in the LIM-homeodomain gene, LMX1B, in nail-patella syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7(7):1091–1098. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendt TM, Tanji N, Guo J, Kislinger TR, Qu W, Lu Y, Bucciarelli LG, Rong LL, Moser B, Markowitz GS, Stein G, Bierhaus A, Liliensiek B, Arnold B, Nawroth PP, Stern DM, D'Agati VD, Schmidt AM. RAGE drives the development of glomerulosclerosis and implicates podocyte activation in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Am J Pathol. 2003;162(4):1123–1137. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63909-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, Farrington MK, Creazzo T, Hawkins AF, Daskalakis N, Kwan SY, Ebersviller S, Burchette JL, Pericak-Vance MA, Howell DN, Vance JM, Rosenberg PB. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science. 2005;308(5729):1801–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1106215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G, Stahl RA. CD2-associated protein and glomerular disease. Lancet. 2003;362(9397):1746–1748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14856-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu ZG, Ryu DR, Yoo TH, Jung DS, Kim JJ, Kim HJ, Choi HY, Kim JS, Adler SG, Natarajan R, Han DS, Kang SW. P-Cadherin is decreased in diabetic glomeruli and in glucose-stimulated podocytes in vivo and in vitro studies. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(3):524–531. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Z, Schmidt-Ott KM, Chua S, Foster KA, Frankel RZ, Pavlidis P, Barasch J, D'Agati VD, Gharavi AG. A Mendelian locus on chromosome 16 determines susceptibility to doxorubicin nephropathy in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(7):2502–2507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409786102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]