Abstract

When non-psychiatric individuals compare the weights of two similar objects of identical mass, but of different sizes, the smaller object is often perceived as substantially heavier. This size-weight illusion (SWI) is thought to be generated by a violation of the common expectation that the large object will be heavier, possibly via a mismatch between an efference copy of the movement and the actual sensory feedback received. As previous research suggests patients with schizophrenia have deficits in forward model/efference copy mechanisms, we hypothesized that schizophrenic patients would show a reduced SWI. The current study compared the strength of the SWI in schizophrenic patients to matched non-psychiatric participants; weight discrimination for same-sized objects was also assessed. We found a reduced SWI for schizophrenic patients, which resulted in better (more veridical) weight discrimination performance on illusion trials compared to non-psychiatric individuals. This difference in the strength of the SWI persisted when groups were matched for weight discrimination performance. The current findings are consistent with a dysfunctional forward model mechanism in this population. Future studies to elucidate the locus of this impairment using variations on the current study are also proposed.

Keywords: schizophrenia, size-weight illusion, pre-pulse inhibition, forward model, efference copy, weight discrimination

1. Introduction

When people compare the weights of two similar objects of identical mass, one large and one small, the smaller object is often perceived as substantially heavier. This striking perceptual effect, the size-weight illusion (SWI) (Charpentier, 1891), is thought to be generated by a violation of expectation, such that when participants initially view the objects, the brain “expects,” that the larger object will be heavier. When both are subsequently lifted, the larger object feels surprisingly light, and the smaller object feels surprisingly heavy, so the small object is perceived as the heavier of the two (Ross, 1966; Ross and Gregory, 1970). Previous research has indicated that sensorimotor (Ross, 1966; Ross and Gregory, 1970), perceptual (Flanagan and Beltzner, 2000; Grandy and Westwood, 2006), and cognitive (Ellis and Lederman, 1998) components all contribute to the illusion.

The current study investigated the SWI in patients with schizophrenia, a population with known deficits in a prediction mechanism believed to be essential for the generation of this illusion. The sensorimotor mismatch explanation for the SWI has been framed within the context of the forward model of motor control (Wolpert and Miall, 1996; Jordan and Rumelhart, 1992), which proposes that when a motor command is sent to the primary motor cortex, an efference copy of that command is also generated, and used to predict the sensory feedback that would be expected if the movement is executed successfully. A comparator then makes comparisons between this predicted sensory feedback and actual sensory feedback, which are used for online movement adjustments, cancelling sensory reafference, and improving movement prediction and planning (Wolpert, 1997; Wolpert and Kawato, 1998). Within this framework, the SWI is thought to be caused by a mismatch between predicted sensory feedback and conflicting sensory feedback received when the objects are actually lifted.

This forward model mechanism also allows for the discrimination of internally and externally generated motor movements, as self-initiated speech and actions will be preceded by an efference copy, and externally generated stimulation will not. Previous researchers (e.g. Feinberg, 1978; Ford and Mathalon, 2005; Frith, 1987) have proposed that a deficient forward model mechanism in schizophrenic patients, at the level of the efference copy or the comparator, may explain some of the positive symptoms of the disorder. For example, auditory hallucinations may be inner speech misidentified as an external “voice,” and delusions of control may be self-initiated movements incorrectly labeled as externally controlled. Experimental evidence for such forward model deficits in schizophrenic patients have been found in the auditory (Ford and Mathalon, 2005; Ford et al., 2001a; Ford et al., 2001b; Ford et al., 2007), motor (Shergill et al., 2005), and tactile (Blakemore et al., 2000) domains. Based on these previous findings, we hypothesized that a deficient forward model mechanism would result in a reduced or absent SWI in schizophrenic patients, relative to non-psychiatric comparison participants.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were twenty schizophrenic patients and twenty non-psychiatric participants, recruited via the UCSD Schizophrenia Research Program. All patients had confirmed diagnoses based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, with no other Axis 1 diagnoses or history of neurologic insult. Current clinical symptoms were assessed using the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS, Andreasen, 1984a) and the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS, Andreasen, 1984b). Non-psychiatric participants were recruited through newspaper advertisements and flyers posted at the UCSD medical center, and were screened to rule out past or present Axis I or II diagnoses and drug abuse. Participants were assessed on their capacity to provide informed consent, and given a detailed description of their participation in the study. Written consent was obtained via a consent form approved by the University of California, San Diego institutional review board (Protocol # 070052).

All schizophrenic patients were clinically stable, and Tables 1 and 2 contain demographic, clinical and medication information. Groups did not differ in age [t(38) = 0.37; p = .71] and there was a trend towards higher years of education for the non-psychiatric group [t(38) = 1.94, p = .06]. Handedness was assessed with Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, 1971) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | NCP | SZ Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 50.7 (9.37) | 51.75 (8.77) |

| Male/Female, # | 9/11 | 8/12 |

| Education, mean (SD), years | 14.95 (2.54) | 13.45 (2.35) |

| Handedness, Right/Left/Ambidextrous, # | 19/1/0 | 18/1/1 |

Abbreviations: NCP, Non-psychiatric comparison participants; SZ, schizophrenia.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients with Schizophrenia

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Duration of Illness, mean (SD), years | 29.85 (10.5) |

| Hospitalizations, mean (SD), # | 5.9 (6.7) |

| Diagnostic Subtype, # | |

| Paranoid | 11 |

| Undifferentiated | 5 |

| Residual | 4 |

| Medication, # | |

| Atypical antipsychotic | 19 |

| Unmedicated | 1 |

| Living situation, # | |

| Independently or with family | 15 |

| Board and Care facility | 5 |

| SAPS Score, mean (SD) | 8.2 (5.22) |

| SANS Score, mean (SD) | 13.85 (4.85) |

2.2. Size-weight Illusion (SWI)

To assess the SWI, participants compared pairs of gray painted wooden disks and reported which was heavier. Disks were 1.5″ tall and were either large (5″ diameter) or small (2″ diameter). The surface area of the small disk was 25% the surface area of the large disk (15.71 in2 for the small disk, 62.83 in2 for the large), resulting in a size disparity between objects of 75%. The objects’ mass was evenly distributed about their centers, and disks appeared to be of uniform material. Participants were told, “during this experiment, you will be asked to compare the weights of these grey disks. Some are large (experimenter holds up large disk) and some are small (experimenter holds up small disk). On some trials you will compare two disks of the same size; that is, two large disks or two small disks; and on some trials you will have one of each size.” During testing, two disks were simultaneously placed onto participants’ outstretched hands, and they had up to 10 seconds to respond. Participants were instructed to view the disks while making the discrimination judgment. If participants’ looked away from the disks, or appeared to shift their attention away from the task, they were redirected by the experimenter before a response was recorded. SWI trials compared a 90 gram small disk to large disks of increasing weights (100 – 210 grams in 10 gram increments). Weight discrimination trials compared same-sized disks in five series, with a standard weight compared against three heavier and three lighter disks, in increments of 10 grams. There were three weight discrimination series with large disks (standards 120, 150, 180 grams) and two with small disks (standards 120, 150 grams). Each SWI comparison was tested four times, and each weight discrimination trial was tested twice, counterbalanced for hand, for a total of 118 trials in one of five random orders. As “same weight” judgments were not allowed, 90 g small vs. 90 g large comparisons were excluded from final analyses.

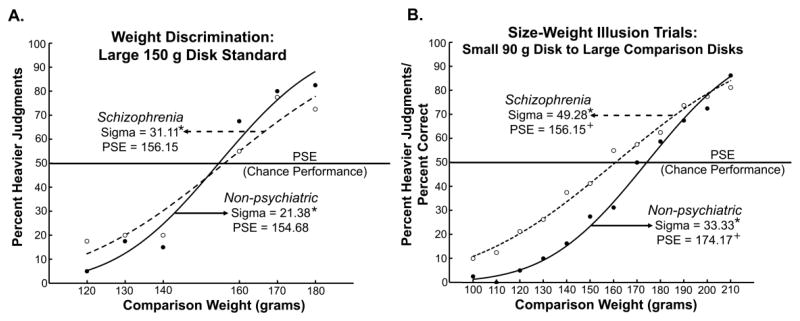

2.3. Statistical Analyses

For all series of comparisons (five weight discrimination and one SWI), data were averaged across group (Schizophrenic vs. Control) and fit with a cumulative normal curve using Matlab (The Mathworks, Natick, MA, Figure 1). For each group, we calculated sigma, a measure of weight discrimination sensitivity, and the point of subjective equality (PSE), or the point at which subjects are equally likely to report that one weight is heavier than the other, and therefore cannot discriminate between the two stimuli (Gescheider, 1997). Sensitivity was calculated as the standard deviation (σ, higher values = less sensitive) and the PSE as the mean (μ) of the underlying normal distribution that generated the cumulative normal fit to the data (Table 3). As there are relatively few trials per participant for individual comparisons, data fits for individual participants are unstable, making traditional parametric statistics such as an ANOVA non-optimal for these data. Statistical significance was therefore assessed using a bootstrap method (Davison and Hinkley, 2006; Efron and Tibshirani, 1993) in Matlab to assess whether the observed differences between groups are more extreme than differences expected by chance alone. Random groups of twenty participants were selected from the entire sample and compared to the remaining twenty participants. Data were averaged across the randomly selected groups, and fit as described above. Values for each group were subtracted from one another to create a between-groups difference score for each metric. This was repeated 10 000 times for each series, and difference scores were used to create a sampling distribution of mean differences for random assignment to groups. Observed mean differences in each condition were compared to these sampling distributions, and conditions for which the observed difference (Schizophrenic – Control) fell within the upper or lower 2.5% of the sampling distributions, as in a two-tailed hypothesis test at α < .05, were considered significant.

Figure 1.

Cumulative normal fits for A) a representative example of weight discrimination series with a large disk standard weight of 150 grams and B) size-weight illusion (SWI) trials, which compared a 90 gram small disk to large disks of increasing weights, 100 – 210 grams in 10 gram increments. Points are average percent heavier values for the respective groups; closed circles and solid lines represent non-psychiatric comparison participants, whereas open circles and dotted lines represent schizophrenic patients. Within panels, values marked with a star or a plus sign significantly differ from one another at p < .05. Although the sigma values, a measure of weight discrimination sensitivity, differ between groups in both conditions, the point of subjective equality (PSE) – where the weights are perceived as equal and the SWI is nulled – differs only in the SWI condition. For schizophrenic patients, the PSE is shifted to the left, with a significantly lighter value compared to non-psychiatric participants, indicative of a reduced SWI.

Table 3.

Sigma and PSE Values for All Conditions.

| Sigma | PSE (g) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparison Series | Schizophrenic | Non-Psychiatric | Difference | Schizophrenic | Non-Psychiatric | Difference |

| Size-Weight Illusion | 49.28 | 33.33 | 15.95* | 160.80 | 174.17 | −13.37* |

| Weight Discrimination Large 120 Standard | 32.53 | 20.44 | 12.09* | 120.86 | 121.49 | −0.63 |

| Weight Discrimination Large 150 Standard | 31.11 | 21.38 | 9.73* | 156.15 | 154.68 | 1.47 |

| Weight Discrimination Large 180 Standard | 47.51 | 25.19 | 22.32* | 176.66 | 178.31 | −1.65 |

| Weight Discrimination Small 120 Standard | 23.71 | 21.98 | 1.73 | 122.59 | 117.36 | 5.23 |

| Weight Discrimination Small 150 Standard | 32.65 | 23.83 | 8.82* | 149.47 | 148.74 | 0.73 |

Starred values significant at p < .05.

3. Results

In all but one condition, schizophrenic patients had significantly higher sigma values than non-psychiatric individuals (Table 3 and Figure 1), indicative of less sensitive weight discrimination as expected based on previous studies (Ritzler, 1977; Leventhal et al., 1982; Javitt et al., 1999). The PSE did not differ between groups for any weight discrimination series (Table 3; graphs for other conditions in Supplementary Data, Figure 1). For the SWI trials, however, the PSE for the schizophrenic patients, 160.80 g, was significantly lighter than the PSE for non-psychiatric individuals, 174.17 g. The PSE, where the compared weights are perceived as equal, is the point at which the illusion is nulled (Figure 1B). As such, the PSE is a measure of the strength of the SWI, with heavier values indicating a stronger illusion. This pattern of results supports our hypothesis of a reduced SWI in the schizophrenic patient group. Excluding residual schizophrenic patients, the unmedicated patient, and non-right handed participants, respectively, did not change this pattern of results, and results are reported for the full sample.

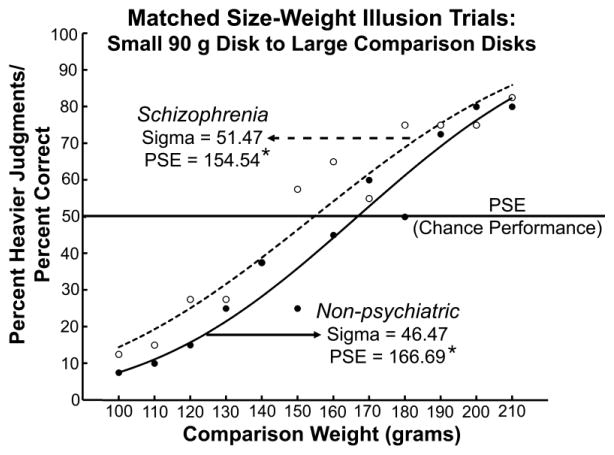

The fact that schizophrenic patients showed less sensitive weight discrimination performance across five of the six discrimination series, whereas the PSE difference appears only in the size-weight condition, implies that the PSE differences in the SWI cannot be explained by these sensitivity differences alone. However, to further control for the influence of discrimination sensitivity, the same analyses were also run on data from ten participants in each group matched on weight discrimination performance. In this subset analysis, neither the PSE nor sigma differed between the groups for any of the weight discrimination series. With this performance matching, the PSE for the schizophrenic patients in the SWI condition, 154.54 g, was still significantly lighter than that of non-psychiatric individuals, 166.69 g, while sigma values did not differ significantly (Figure 2). This provides further evidence that the reduced SWI in the patient group cannot be explained by differences in weight discrimination ability.

Figure 2.

Cumulative normal fit for size-weight illusion (SWI) trials for ten participants in each group matched for weight discrimination performance. Points are average percent heavier values for the respective groups; closed circles and solid lines represent non-psychiatric comparison participants, whereas open circles and dotted lines represent schizophrenic patients. Starred values differ from one another at p < .05. The sigma values (weight discrimination sensitivity) do not significantly differ between groups, indicating successful matching for weight discrimination performance. With this performance matching, the point of subjective equality (PSE) for the schizophrenic patients in the SWI condition is still significantly lighter than that of non-psychiatric individuals, providing further evidence that this finding cannot be explained by differences in weight discrimination ability.

Ideally, the strength of a single participants’ SWI would be determined by the PSE of cumulative normal fits of individual size-weight datasets. However, the large range of weight discriminations tested in the current study restricted the number of judgments per comparison that could be reasonably collected in a single experimental session, a limitation that could be addressed in a future, dedicated study. Therefore, as an alternative way to investigate the relationship between incidence of the SWI and the symptoms of schizophrenia, a linear correlation was run between the number of trials (out of a possible 52) that patients’ experienced the SWI, and positive (global SAPS) and negative (global SANS) symptom ratings. No significant correlations were found between SWI performance and either type of symptoms. The absence of a correlation between the SWI and positive symptoms is somewhat surprising, given previous proposals that abnormal forward model processes may drive some of these symptoms. However, it is possible the count metric employed to quantify the SWI for individual participants is not sensitive enough to detect this relationship or that positive symptom scores reflect additional processes, in addition to underlying forward model deficits, that are also impaired.

4. Discussion

In the size-weight illusion (SWI) condition, the point of subjective equality (PSE), where the illusion is nulled and the weights are perceived as equal, differed between groups. This PSE value quantifies the strength of the SWI, as it represents the perceived weight of the small comparison disk. Therefore, a lighter PSE (160.80 g) in the patient group compared to the non-psychiatric group (174.17 g) demonstrates that schizophrenic patients experience a weaker SWI, confirming our prediction based on impaired forward model processes. In contrast, the PSE did not differ between groups in any weight comparison series, supporting a specific deficit in the illusion condition, above and beyond expected differences in weight discrimination sensitivity.

Schizophrenic patients also showed consistently more veridical weight discrimination performance across almost the entire range of size-weight stimuli (Figure 1B). For over 30 years, since Sutton and colleagues (Zubin et al., 1975) posed the challenge, neuroscientists have searched for tasks on which schizophrenic patients “outperform” non-psychiatric individuals based on their underlying cognitive and neural dysfunction. Finding tasks such as these minimizes the need to consider attentional impairments (Braff, 1993; Nuechterlein and Dawson, 1984) and/or decreased motivation to perform (e.g., avolition) in the patient group as possible explanations for between-group differences, which is a concern for many studies conducted with schizophrenic patients. These results offer promise that the SWI may be one of the rare paradigms fitting the criterion of “better performance based on a deficit” (also see Shergill et al., 2005; de Gelder et al., 2003 for similar patterns of data).

This finding is consistent with previous accounts of abnormal forward model mechanisms in schizophrenic patients, which have been proposed to underlie some of the positive symptoms of schizophrenia (Feinberg, 1978; Ford and Mathalon, 2005; Frith, 1987). Although this reduction in the SWI is consistent with a specific problem with the efference copy mechanism, as has been proposed in other studies of patients with schizophrenia (Ford et al., 2007), a reduced illusion could arise from dysfunction at any part of the forward model prediction process, including the motor prediction, the comparator mechanism, or the incoming sensory feedback after lifting the objects. These data reveal a forward model deficit in a new domain - weight perception.

Areas of the brain implicated in the SWI and forward motor models in general include the parietal lobe (Jenmalm et al., 2006; Chouinard et al., 2009; Sirigu et al., 2004) and the cerebellum (Miall et al., 1993), which are also known to be abnormal in patients with schizophrenia (Danckert et al., 2004; Ross and Pearlson, 1996; Torrey, 2007; Andreasen and Pierson, 2008). A reduced SWI in schizophrenic patients also fits with emerging research indicating a specific deficit in multisensory integration in this population (de Gelder et al., 2003; de Gelder et al., 2005; de Jong et al., 2009; Ross et al., 2007), as the SWI is strongest when both visual and tactile cues are presented (Ellis and Lederman, 1993; Kawai et al., 2007).

One potential limitation to the current study design is that participants were not explicitly tested on their ability to discriminate the visual size of the large and small objects. A previous study (Holcomb et al., 2004) has shown that patients with schizophrenia are less sensitive to visual size differences between objects compared to non-psychiatric individuals, which could affect the strength of the SWI. We believe this to be a relatively minor factor in the current study as the size disparity between objects (75%) is much greater than the range tested in this previous study (1% - 25%); however, this could also contribute to a reduced illusion. Finally, despite all efforts to equilibrate attention to the task, task motivation, and attention to the size of the stimuli across diagnostic groups, we cannot conclusively state that these factors did not vary between groups. To address this potential confound, participants were tested by a researcher experienced in administering this psychophysical task (L.E.W.) who redirected participants’ attention on a trial by trial basis, as needed. Also, task instructions specifically referenced disk size and labeled disks as large and small. Although schizophrenic patients demonstrated less sensitive weight discrimination than the non-psychiatric group, their performance is above chance levels, and modulated by task difficulty in a similar manner to the non-psychiatric group (decreasing performance as disks become closer in weight). However, the fact that we can not definitively conclude patients and controls were paying equal attention to the task limits how strongly this finding of “better performance based on a deficit” can be interpreted.

Building on this novel initial finding, future studies are needed to address the limitations presented above, replicate this finding in chronic medicated schizophrenic patients and to further explore the clinical correlates of these deficits by testing with early illness, acute patient groups, and with other patients with psychotic features such as patients with bipolar disorder. Additional studies using variations of the current paradigm may provide insight into whether these forward model deficits occur at the level of the motor prediction, the efference copy, the comparator mechanism or the sensory feedback, which is yet to be understood. The fact that patients experience the SWI, albeit to an attenuated degree, indicates that an efference copy is being generated, and compared with actual sensory feedback. To further explore the nature of the deficit, previous research has shown that that typical individuals incorrectly estimate the forces needed to lift size-weight objects on initial trials, but rapidly adjust their grip and lift forces for the actual mass of the object (Flanagan and Beltzner, 2000; Grandy and Westwood, 2006). In testing with schizophrenic patients, if their initial lift forces are similar to non-psychiatric individuals, this would imply that prediction mechanisms are intact, and that the dysfunction lies either in the efference copy, sensory feedback, or comparator processes. An even more dramatic test of updating and adaptation in the patient group would be to train patients with stimuli that have an inverted volume-weight relationship, which have been shown to reduce and even reverse the SWI in non-psychiatric participants (Flanagan et al., 2008). A reduced training effect in the patient group would support the hypothesis that schizophrenic patients either do not register sensory mismatches or violations of expectations as strongly as do non-psychiatric individuals or that these prediction errors are not used to revise and update internal models. Evidence for this type of deficit would have important functional implications, as revisions to internal prediction models are necessary to successfully adapt to a changing environment.

In conclusion, the current study presents a rare finding for schizophrenia research, in which the patients’ deficits result in more accurate than normal performance on a sensory illusion task. This reduced SWI in the schizophrenic group persists even when groups are matched on weight discrimination performance, indicating these results can not be explained by poor discrimination sensitivity in the patient group. Future studies using related paradigms and additional levels of investigation (e.g., functional brain imaging) may provide further insight into the specific nature of the forward model mechanism deficits in schizophrenic patients, as well as potential consequences in terms of perceptual learning and adaptation, relationship with clinical profiles, and a better understanding of how higher-order cognitive problems in schizophrenia may arise from lower-level perceptual deficits.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Karen Dobkins, Neal Swerdlow, Steven Hillyard and Stuart Anstis for helpful discussion, as well as John Greer, Kelsey Thomas, and Marissa Wagner for assistance with pilot data collection

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, Email: vramacha@ucsd.edu.

Edward M. Hubbard, Email: edhubbard@gmail.com.

David L. Braff, Email: dbraff@ucsd.edu.

Gregory A. Light, Email: glight@ucsd.edu.

References

- Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) University of Iowa; Iowa City, Iowa: 1984a. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) University of Iowa; Iowa City, Iowa: 1984b. [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen NC, Pierson R. The role of the cerebellum in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(2):81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakemore SJ, Smith J, Steel R, Johnstone CE, Frith CD. The perception of self-produced sensory stimuli in patients with auditory hallucinations and passivity experiences: evidence for a breakdown in self-monitoring. Psychol Med. 2000;30(5):1131–1139. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799002676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braff DL. Information processing and attention dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1993;19(2):233–259. doi: 10.1093/schbul/19.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charpentier A. Analyse experimentale de quelques elements de la sensation de poids [Experimental analysis of some elements of weight sensations] Archives de Physiologie Normales et Pathologiques. 1891;3:122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chouinard PA, Large ME, Chang EC, Goodale MA. Dissociable neural mechanisms for determining the perceived heaviness of objects and the predicted weight of objects during lifting: an fMRI investigation of the size-weight illusion. Neuroimage. 2009;44(1):200–212. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danckert J, Saoud M, Maruff P. Attention, motor control and motor imagery in schizophrenia: implications for the role of the parietal cortex. Schizophr Res. 2004;70(2–3):241–261. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AC, Hinkley D. Bootstrap Methods and their Application. 8. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- de Gelder B, Vroomen J, Annen L, Masthof E, Hodiamont P. Audio-visual integration in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2003;59(2–3):211–218. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(01)00344-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Gelder B, Vroomen J, de Jong SJ, Masthoff ED, Trompenaars FJ, Hodiamont P. Multisensory integration of emotional faces and voices in schizophrenics. Schizophr Res. 2005;72(2–3):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2004.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JJ, Hodiamont PP, Van den Stock J, de Gelder B. Audiovisual emotion recognition in schizophrenia: Reduced integration of facial and vocal affect. Schizophr Res. 2009;107(2–3):286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An introduction to the bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; New York, NY: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RR, Lederman SJ. The golf-ball illusion: evidence for top-down processing in weight perception. Perception. 1998;27(2):193–201. doi: 10.1068/p270193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis RR, Lederman SJ. The role of haptic versus visual volume cues in the size-weight illusion. Percept Psychophys. 1993;53(3):315–324. doi: 10.3758/bf03205186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg I. Efference copy and corollary discharge: implications for thinking and its disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1978;4(4):636–640. doi: 10.1093/schbul/4.4.636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JR, Beltzner MA. Independence of perceptual and sensorimotor predictions in the size-weight illusion. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3(7):737–741. doi: 10.1038/76701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JR, Bittner JP, Johansson RS. Experience can change distinct size-weight priors engaged in lifting objects and judging their weights. Curr Biol. 2008;18(22):1742–1747. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM, Mathalon DH. Corollary discharge dysfunction in schizophrenia: can it explain auditory hallucinations? Int J Psychophysiol. 2005;58(2–3):179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM, Mathalon DH, Heinks T, Kalba S, Faustman WO, Roth WT. Neurophysiological evidence of corollary discharge dysfunction in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2001a;158(12):2069–2071. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM, Mathalon DH, Kalba S, Whitfield S, Faustman WO, Roth WT. Cortical responsiveness during inner speech in schizophrenia: an event-related potential study. Am J Psychiatry. 2001b;158(11):1914–1916. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JM, Roach BJ, Faustman WO, Mathalon DH. Out-of-Synch and Out-of-Sorts: Dysfunction of Motor-Sensory Communication in Schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frith CD. The positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia reflect impairments in the perception and initiation of action. Psychol Med. 1987;17(3):631–648. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700025873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gescheider GA. Psychophysics: The Fundamentals. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Grandy MS, Westwood DA. Opposite perceptual and sensorimotor responses to a size-weight illusion. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95(6):3887–3892. doi: 10.1152/jn.00851.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holcomb HH, Parwani A, McMahon RP, Medoff DR, Frey K, Lahti AC, Tamminga CA. Parametric study of accuracy and response time in schizophrenic persons making visual or auditory discriminations. Psychiatry Res. 2004;127(3):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javitt DC, Liederman E, Cienfuegos A, Shelley AM. Panmodal processing imprecision as a basis for dysfunction of transient memory storage systems in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(4):763–775. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenmalm P, Schmitz C, Forssberg H, Ehrsson HH. Lighter or heavier than predicted: neural correlates of corrective mechanisms during erroneously programmed lifts. J Neurosci. 2006;26(35):9015–9021. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5045-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan MI, Rumelhart DE. Forward Models: Supervised learning with a distal teacher. Cognitive Science. 1992;16:307–354. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai S, Henigman F, MacKenzie CL, Kuang AB, Faust PH. A reexamination of the size-weight illusion induced by visual size cues. Exp Brain Res. 2007;179(3):443–456. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0803-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal DB, Schuck JR, Clemons JT, Cox M. Proprioception in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1982;170(1):21–26. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198201000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miall RC, Weir DJ, Wolpert DM, Stein JF. Is the Cerebellum a Smith Predictor? J Mot Behav. 1993;25(3):203–216. doi: 10.1080/00222895.1993.9942050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME. Information processing and attentional functioning in the developmental course of schizophrenic disorders. Schizophr Bull. 1984;10(2):160–203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/10.2.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia. 1971;9(1):97–113. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzler BA. Proprioception and schizophrenia: a replication study with nonschizophrenic patient controls. J Abnorm Psychol. 1977;86(5):501–509. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.86.5.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CA, Pearlson GD. Schizophrenia, the heteromodal association neocortex and development: potential for a neurogenetic approach. Trends Neurosci. 1996;19(5):171–176. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(96)10022-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE. Sensory information necessary for the size-weight illusion. Nature. 1966;212(5062):650. doi: 10.1038/212650a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross HE, Gregory RL. Weight illusions and weight discrimination-a revised hypothesis. Q J Exp Psychol. 1970;22(2):318–328. doi: 10.1080/00335557043000267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross LA, Saint-Amour D, Leavitt VM, Molholm S, Javitt DC, Foxe JJ. Impaired multisensory processing in schizophrenia: deficits in the visual enhancement of speech comprehension under noisy environmental conditions. Schizophr Res. 2007;97(1–3):173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shergill SS, Samson G, Bays PM, Frith CD, Wolpert DM. Evidence for sensory prediction deficits in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2384–2386. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirigu A, Daprati E, Ciancia S, Giraux P, Nighoghossian N, Posada A, Haggard P. Altered awareness of voluntary action after damage to the parietal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(1):80–84. doi: 10.1038/nn1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF. Schizophrenia and the inferior parietal lobule. Schizophr Res. 2007;97(1–3):215–225. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert DM. Computational approaches to motor control. Trends in Cognitive Science. 1997;1:209–216. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(97)01070-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert DM, Kawato M. Multiple paired forward and inverse models for motor control. Neural Netw. 1998;11(7–8):1317–1329. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(98)00066-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpert DM, Miall RC. Forward Models for Physiological Motor Control. Neural Netw. 1996;9(8):1265–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0893-6080(96)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubin J, Salzinger K, Fleiss JL, Gurland B, Spitzer RL, Endicott J, Sutton S. Biometric approach to psychopathology: abnormal and clinical psychology-statistical, epidemiological, and diagnostic approaches. Annu Rev Psychol. 1975;26:621–671. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.26.020175.003201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.