Abstract

Introduction:

Empirical work has demonstrated a linkage between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms. However, there is little understanding of the mechanisms underlying this association.

Method:

The present investigation examined the role of coping-based smoking motives in terms of mediating the relations between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms and anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate among a sample of treatment-seeking adult smokers (N = 123; 84 women; Mage = 45.93, SD = 10.34).

Results:

Results indicated that coping motives mediated the relations between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms and anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate.

Discussion:

These results suggest that coping motives play a key role in terms of better understanding the association between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms.

Introduction

A recent and increasingly robust body of literature has begun to examine the linkages between smoking and anxiety-related disorders (Feldner, Babson, & Zvolensky, 2007; Morissette, Tull, Gulliver, Kamholz, & Zimering, 2007; Patton et al., 1998; Zvolensky, Feldner, Leen-Feldner, & McLeish, 2005). Several empirical studies have demonstrated that smoking at higher rates may be concurrently and prospectively associated with an increased risk of more severe anxious arousal symptoms and greater life impairment related to such symptoms (Breslau & Klein, 1999; Breslau, Novak, & Kessler, 2004; Goodwin, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 2005; Isensee, Wittchen, Stein, Höfler, & Lieb, 2003; Johnson et al., 2000; McLeish, Zvolensky, & Bucossi, 2007; Zvolensky, Schmidt, & McCreary, 2003). For instance, Johnson et al. (2000) found that smoking rate was prospectively related to an increased risk of panic attacks. A related body of scientific literature, while limited, has demonstrated that more severe symptoms of anxiety may be associated with greater rates of smoking (Morissette et al., 2007; Patton et al., 1998; Rose, Ananda, & Jarvik, 1983). For example, prospective work examining smoking initiation among adolescents has demonstrated that anxiety-related symptoms may increase the likelihood of (a) initiating smoking and (b) transitioning to regular (e.g., daily) smoker status (Patton et al., 1998).

Despite the documented association between smoking rate and anxiety symptoms and vice versa, there is less understanding of the mechanisms involved. Motivational models of substance use predict that distinct motives may theoretically be related to particular types of substance-related problems or individual emotional vulnerability characteristics (Cooper, 1994; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Cox & Klinger, 1988; Stewart, Zeitlin, & Samoluk, 1996). Such an approach recognizes that two individuals may use tobacco for different reasons and one individual may use for multiple types of reasons (Cooper; Ikard, Green, & Horn, 1969; Russell, Peto, & Patel, 1974). Motivational models predict that distinct motives may theoretically be related to particular types of problems (Cooper). Several distinct smoking motives have been identified (Ikard et al.). Of particular relevance to the study of anxiety–smoking relations are coping-oriented motives. To provide greater clarity to the overall presentation of ideas and contextualization of them within the larger scientific literature, we use the term “coping motives” throughout the present article (please see Measures section for additional information regarding the coping motives subscale). Specifically, individuals who frequently use tobacco for negative affect reduction or regulation reasons may be apt to be at an increased concurrent and prospective risk for negative emotional states such as anxiety (Zvolensky & Bernstein, 2005). Thus, cigarette smokers who are more motivated to use tobacco as a coping strategy for negative emotional experiences, such as anxious arousal, may be most vulnerable to anxiety disturbances. Alternatively, smokers with higher levels of anxious arousal symptoms may rely on smoking to cope and therefore be more apt to smoke at higher rates. Thus, there are possible bidirectional effects between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms, but in both cases, coping motives for smoking may play a key explanatory role.

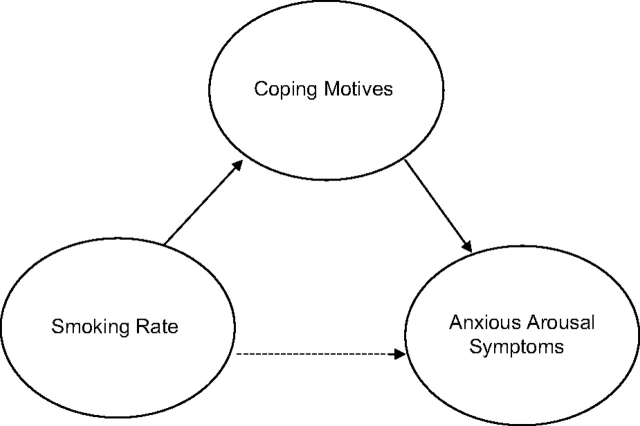

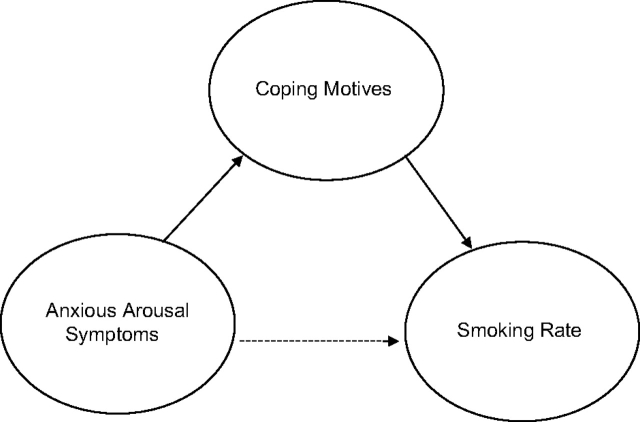

It is presently unclear whether coping-based smoking motives mediate the relation between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms or the alternative model of anxious arousal symptoms to smoking rate. This information is important theoretically for explicating the mechanisms underlying smoking–anxiety linkages and may help guide treatment planning for high-risk samples (e.g., smokers with anxiety disturbances). Accordingly, the present investigation tested the hypothesis that among treatment-seeking adult daily smokers, coping motives for smoking would concurrently mediate (explain) the relation between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms (see Figure 1). A secondary aim of the present investigation was to explore a second mediational model wherein coping motives mediated the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate (see Figure 2). Please see the Data Analytic Strategy section for a detailed description of our statistical rationale.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized mediational model: coping motives mediating smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms.

Figure 2.

Hypothesized mediational model: coping motives mediating anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate.

Method

Participants

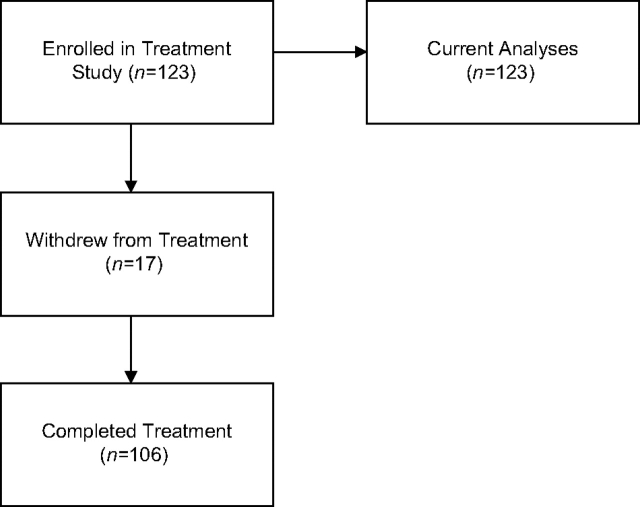

Figure 3 shows a CONSORT flow diagram detailing recruitment procedures and the identification of the present sample. Participants included 123 daily cigarette smokers (84 women; Mage = 45.93 years, SD = 10.34) living in the Halifax Regional Municipality, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. Daily smokers were recruited for participation from among those attending a structured 4-week group Tobacco Intervention Program offered through Addiction Prevention and Treatment Services, Capital District Health Authority. All those daily smokers participating in the program were invited to participate. Participants reported attaining the following levels of education: 41% completed high school, 31% completed college (community college or technical schooling), 13% completed university (traditional 4-year schooling), 11% completed junior high school, and 4% completed elementary school. With regard to marital/relationship status, 48% of the sample reported being married/cohabiting with a partner, 35% reported being separated/divorced/widowed, and 17% reported being single.

Figure 3.

CONSORT diagram illustrating the process of participant selection.

Participants reported smoking an average of 15.46 (SD = 7.95) cigarettes per day and endorsed relatively high levels of nicotine dependence (M = 6.25, SD = 2.17), as indexed by the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND; Fagerström, 1978; Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991) at treatment outset. Participants reported initiating daily smoking at a mean age of 16.60 years (SD = 4.77) and smoking regularly for an average of 28.28 years (SD = 10.64). In terms of smoking cessation, participants endorsed an average of 2.95 (SD = 2.85) self-defined “serious” lifetime quit attempts, and 5.77 (SD = 12.57) lifetime quit attempts lasting longer than 12 hr (as indexed by the Smoking History Questionnaire [SHQ]; Brown, Lejuez, Kahler, & Strong, 2002). The average longest lifetime period of smoking abstinence after a quit attempt among participants was 1.14 years (SD = 2.74).

Measures

Smoking History Questionnaire.

The SHQ (Brown et al., 2002) is a self-report questionnaire used to assess smoking history and pattern. The SHQ includes items pertaining to smoking rate, age at onset of smoking initiation, and years of being a daily smoker. The SHQ has been successfully used in previous studies as a measure of smoking history (e.g., Zvolensky, Lejuez, Kahler, & Brown, 2004). Smoking rate (i.e., average number of cigarettes smoked per day in the past week) was used in the present analyses.

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence.

The FTND(Fagerström, 1978 ; Heatherton et al., 1991) is a six-item scale designed to assess gradations in tobacco dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991). The FTND has shown good internal consistency, positive relations with key smoking variables (e.g., saliva cotinine; Heatherton et al.), and high degrees of test–retest reliability (Pomerleau, Carton, Lutzke, Flessland, 1994).

Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire.

The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ; Watson et al., 1995) is a 62-item measure of affective symptoms. Participants indicate how much they have experienced each symptom during the past week on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely). Factor analysis indicates that this scale taps distinct anxiety and depression symptom domains. The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire–Anxious Arousal (MASQ-AA) subscale measures symptoms of somatic tension and arousal (e.g., “felt dizzy”). The Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire–Anhedonic Depression (MASQ-AD) subscale measures a loss of interest in life (e.g., “felt nothing was enjoyable”), and reverse-keyed items measure positive affect. The MASQ shows excellent convergence with other measures of anxiety and good discriminative validity for anxious versus depressive symptoms via the MASQ-AA and MASQ-AD subscales, respectively (Watson et al., 1995). The MASQ-AA and MASQ-AD subscales displayed good internal consistency in the current sample (alpha coefficients: .83 and .89, respectively) and were used to index anxious arousal and depressive symptoms in the present investigation.

Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives.

Smoking dependence motives were assessed with the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68; Piper et al., 2004), a 68-item measure in which respondents indicate on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = not true of me at all to 7 = extremely true of me) the degree to which they have smoked cigarettes for a variety of possible reasons (e.g., improves my mood). Factor analysis of the scale indicates that it has 13 first-order factors. In the present study, we were primarily interested in the coping motives subscale termed Negative Reinforcement Smoking Dependence Motives (e.g., smoking improves my mood; Piper et al., 2004). The WISDM has acceptable levels of internal consistency for each of the 13 factors and has been shown to be significantly related to several measures of dependence (i.e., DSM-IV nicotine-dependence criteria; Piper et al., 2004). The coping motives subscale demonstrated good internal consistency within the present sample (alpha coefficient: .89).

Procedure

The current study is a facet of a larger investigation (Zvolensky, Stewart, Vujanovic, Gavric, & Steeves, 2009). The current analyses have not been reported previously and therefore are a novel contribution. The procedure of the study has been described in detail elsewhere (Zvolensky et al., 2009). The initial phase of the larger study recruited smokers attending an information session about the Tobacco Intervention Program offered through Capital Health. Potential participants were informed about the nature and purpose of the study and were invited to participate in the research portion of the program. Two weeks following the initial information session, eligible participants participated in the study at their first (precessation) meeting of their Tobacco Intervention Program group. At this time, participants were instructed to complete a demographic questionnaire, the SHQ, the FTND, the MASQ, and the WISDM. In addition, participants were offered the chance to receive Nicotine Replacement Therapy (NRT). The program consisted of one 90-min group session per week for 4 weeks, including clinical time (1-hr group) as well as the time for the research component (half an hour). The manualized treatment included both evidence-based behavioral and cognitive strategies and NRT. All participants were provided with a $10 movie pass as compensation. The present analyses were conducted using baseline (precessation) data from the larger study.

Data Analytic Strategy

To test the hypothesized mediational model as well as to explore the second mediational model, we used analytic strategies that are recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986). Specifically, two separate series of mediational analyses were used to test whether: (a) coping motives would mediate the relation between smoking rate (predictor) and anxious arousal symptoms (criterion) and (b) coping motives would mediate the relation between anxious arousal symptoms (predictor) and smoking rate (criterion). Overall, this analytic approach is consistent with general recommendations for mediational analysis (Preacher & Hayes, 2004).

Results

Table 1 shows the zero-order (or point-biserial, as applicable) correlations among predictor and criterion variables. It should also be noted that a correlational analysis was conducted to examine the relation between the smoking rate and the FTND (Fagerström, 1978). Smoking rate was significantly related to the FTND (r = .64). Moreover, smoking rate was significantly related to coping motives and anxious arousal symptoms (observed rs: .27 and .23, respectively); however, smoking rate was not significantly related to anhedonic depression symptoms (r = .13). In addition, coping motives were significantly related to anxious arousal (r = .32) and anhedonic depression symptoms (r = .28). Please note that in order to ensure that the current findings were unique to anxious arousal symptoms, a supplementary test of specificity also was conducted, replacing anxious arousal symptoms with anhedonic depression symptoms. Specifically, smoking rate did not significantly predict anhedonic depression symptoms; likewise, anhedonic depression symptoms did not significantly predict smoking rate. Because smoking rate and anhedonic depression symptoms were unrelated, we could not proceed further to test the possible mediating role of coping motives. Please contact the corresponding author (Dr. Zvolensky) for the full results of these additional analyses.

Table 1.

Zero-order correlations among theoretically relevant variables

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | M or % (SD) | Observed range |

| 1. Gender | 1 | −.01 | .23* | .00 | .10 | 68.29% female | |

| 2. Cigs/Day | 1 | .27** | .23* | .13 | 15.46 (7.95) | 1–45 | |

| 3. WISDM-NR | 1 | .32** | .28** | 4.78 (1.47) | 1–7 | ||

| 4. MASQ-AA | 1 | .42** | 28.18 (8.90) | 17–54 | |||

| 5. MASQ-AD | 1 | 58.06 (13.77) | 31–91 |

Note. Gender dummy coded 0 = males, 1 = females; Cigs/Day = average number of cigarettes smoked per day; WISDM-NR = Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives–Negative Reinforcement subscale; MASQ-AA = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire–Anxious Arousal subscale; MASQ-AD = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire–Anhedonic Depression subscale.

*p < .01; **p < .001.

Initially, a hierarchical linear regression was conducted to examine the relation between smoking rate (the predictor) and anxious arousal symptoms (the criterion). Gender was included as a covariate at Step 1 of the model, and smoking rate was entered at Step 2. Overall, the model predicted 5.1% of variance in anxious arousal symptoms, F(2, 120) = 3.17, p < .05. Step 1 of the model did not significantly predict anxious arousal symptoms (see Analysis 1 in Table 2). Step 2 accounted for 5.1% of variance, and as hypothesized, smoking rate was a significant predictor of anxious arousal symptoms above and beyond gender (see Analysis 1 in Table 2).

Table 2.

Regression analyses testing for mediation: Coping motives mediating the relation between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms

| Independent variable(s) | Dependent variable | b | F |

| 1. Gender (Step 1) | MASQ-AA | .01 | .00 |

| Cig/Day (Step 2) | .23 | 6.34* | |

| 2. Gender (Step 1) | WISDM-NR | .23 | 6.20* |

| Cig/Day (Step 2) | .28 | 10.02** | |

| 3. Gender (Step 1) | MASQ-AA | −.07 | .00 |

| WISDM-NR (Step 2) | .33 | 6.80** | |

| 4. Gender (Step 1) | MASQ-AA | −.05 | 3.23* |

| Cig/Day (Step 1) | .15 | ||

| WISDM-NR (Step 2) | .29 | 9.57** | |

| 5. Gender (Step 1) | MASQ-AA | −.05 | 6.79** |

| WISDM-NR (Step 1) | .29 | ||

| Cig/Day (Step 2) | .15 | 2.74 |

Note. β = standardized beta weight provided for hierarchical multiple regression; F = change in F statistic provided for hierarchical multiple regression (only one F statistic is reported for each step); gender dummy coded 0 = males, 1 = females; Cigs/Day = average number of cigarettes smoked per day; WISDM-NR = Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives–Negative Reinforcement subscale; MASQ-AA = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire–Anxious Arousal subscale.

* p < .05, ** p < .01.

A second hierarchical linear regression was conducted to examine the relation between smoking rate (the predictor) and coping motives (the mediator). Gender was included as a covariate at Step 1 of the model, and smoking rate was entered at Step 2. The model predicted 12.6% of variance in coping motives, F(1, 118) = 8.35, p < .001. Step 1 of the model predicted 5.0% of variance, with gender being a significant predictor of coping motives (see Analysis 2 in Table 2); here, women endorsed greater levels of coping motives than men. Step 2 accounted for an additional 7.5% of variance, and as hypothesized, smoking rate was a significant predictor above and beyond gender (see Analysis 2 in Table 2).

A final hierarchical linear regression was conducted to examine the relation between coping motives (the mediator) and anxious arousal symptoms (the criterion). Similar to the above analyses, gender was included as a covariate at Step 1 of the model, and coping motives were entered at Step 2. Here, 10.4% of variance in anxious arousal symptoms was explained in total, F(1, 119) = 6.80, p < .01. Step 1 of the model did not significantly predict anxious arousal symptoms (see Analysis 3 in Table 2). Step 2 accounted for 10.4% of variance, and coping motives significantly predicted anxious arousal symptoms above and beyond the variance accounted for by gender (see Analysis 3 in Table 2).

As described in Table 2, the mediational role of coping motives in the relation between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms was then examined by using the strategy proposed by Baron and Kenny (1986). In this analysis, when controlling for the effects of smoking rate, coping motives significantly predicted anxious arousal symptoms (see Analysis 4 in Table 2); however, smoking rate was no longer a significant predictor of anxious arousal symptoms after controlling for coping motives. Thus, coping motives mediated the relation between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms (see Analysis 5 in Table 2). Moreover, post-hoc analyses using the Sobel test of mediation revealed that coping motives significantly mediated the relation between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms Z = 2.32 (p < .05).

As mediational analyses are often conducted using longitudinal data, one powerful method of strengthening the interpretation of mediational analyses conducted with cross-sectional data is to conduct an additional analysis reversing the proposed mediator and criterion variable (Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Sheets & Braver, 1999; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). This analytic approach helps ensure that the observed relations are not simply apparent for all combinations of tested variables. That is, reversing their order in the mediational test permits an examination of mediation via a different ordering of the variables. Here, we evaluated whether anxious arousal symptoms mediated the relation between smoking rate and coping motives. Analyses indicated that smoking rate remained a significant predictor of coping motives after controlling for anxious arousal symptoms, F(3, 118) = 9.17, p < .001. This result initially appears inconsistent with mediation. However, post-hoc analyses using the Sobel test for mediation revealed that anxious arousal symptoms partially mediated the relation between smoking rate and coping motives Z = 1.96 (p = .051). Specifically, anxious arousal symptoms accounted for a portion of the unique variance in coping motives; however, anxious arousal symptoms did not fully explain (mediate) the relation between smoking rate and coping motives.

To examine our second model that coping motives mediate the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate, an initial hierarchical linear regression was conducted to examine the relation between anxious arousal symptoms (the predictor) and smoking rate (the criterion). Gender was included as a covariate at Step 1 of the model, and anxious arousal symptoms were entered at Step 2. Overall, the model predicted 5.1% of variance in smoking rate, F(2, 120) = 3.18, p < .05. Step 1 of the model did not significantly predict smoking rate (see Analysis 1 in Table 3). Step 2 accounted for 5.1% of variance, with anxious arousal symptoms being a significant predictor of smoking rate above and beyond gender (see Analysis 1 in Table 3).

Table 3.

Regression analyses testing for mediation: Coping motives mediating the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate

| Independent variable(s) | Dependent variable | β | F |

| 1. Gender (Step 1) | Cig/Day | −.01 | .01 |

| MASQ-AA (Step 2) | .23 | 6.34** | |

| 2. Gender (Step 1) | WISDM-NR | .22 | 6.32* |

| MASQ-AA (Step 2) | .31 | 13.59** | |

| 3. Gender (Step 1) | Cig/Day | −.09 | .09 |

| WISDM-NR (Step 2) | .29 | 10.02** | |

| 4. Gender (Step 1) | Cig/Day | −.08 | 3.28* |

| MASQ-AA (Step 1) | .16 | ||

| WISDM-NR (Step 2) | .24 | 6.16** | |

| 5. Gender (Step 1) | Cig/Day | −.08 | 5.06** |

| WISDM-NR (Step 1) | .24 | ||

| MASQ-AA (Step 2) | .16 | 2.74 |

Note. β = standardized beta weight provided for hierarchical multiple regression; F = Change in F statistic provided for hierarchical multiple regression (only one F statistic is reported for each step); gender dummy coded 0 = males, 1 = females; Cigs/Day = average number of cigarettes smoked per day; WISDM-NR = Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives–Negative Reinforcement subscale; MASQ-AA = Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire–Anxious Arousal subscale.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

A second hierarchical linear regression was conducted to examine the relation between anxious arousal symptoms (the predictor) and coping motives (the mediator). Gender was included as a covariate at Step 1 of the model, and anxious arousal symptoms were entered at Step 2. The model predicted 15% of variance in coping motives, F(2, 119) = 10.29, p < .001. Step 1 of the model predicted 5.1% of variance, with gender being a significant predictor of coping motives (see Analysis 2 in Table 3); here, women endorsed greater levels of coping motives than men. Step 2 accounted for an additional 9.9% of variance, and once again, anxious arousal symptoms were a significant predictor above and beyond gender (see Analysis 2 in Table 3).

A final hierarchical linear regression was conducted to examine the relation between coping motives (the mediator) and smoking rate (the criterion). Similar to the above analyses, gender was included as a covariate at Step 1 of the model, and coping motives were entered at Step 2. Here, 8% of variance in smoking rate was explained in total, F(2, 118) = 5.06, p < .01. Step 1 of the model did not significantly predict smoking rate (see Analysis 3 in Table 3). Step 2 accounted for 8% of variance, and coping motives significantly predicted smoking rate above and beyond the variance accounted for by gender (see Analysis 3 in Table 3).

As described in Table 3, the mediational role of coping motives in the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate also was examined. In these analyses, when controlling for the effects of anxious arousal symptoms, coping motives significantly predicted smoking rate (see Analysis 4 in Table 3); however, anxious arousal symptoms were no longer a significant predictor of smoking rate after controlling for coping motives. Thus, coping motives mediated the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate (see Analysis 5 in Table 3). Moreover, post-hoc analyses using the Sobel test of mediation revealed that coping motives significantly mediated the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate Z = 2.07 (p < .05).

As with the previously tested mediational model, we attempted to strengthen this interpretation by conducting an additional analysis reversing the proposed mediator and criterion variable (Preacher & Hayes, 2004; Sheets & Braver, 1999; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Here, we evaluated whether smoking rate mediated the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and coping motives. Results were not consistent with mediation in this direction, as anxious arousal symptoms remained a significant predictor of coping motives after controlling for smoking rate, F(3, 118) = 9.17, p < .001. Post-hoc analyses using the Sobel test of mediation revealed that smoking rate did not mediate the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and coping motives Z = 1.59 (p = ns).

Discussion

Smoking rate was significantly and uniquely associated with anxious arousal symptoms; specifically, smoking rate accounted for approximately 5.1% of the unique variance in anxious arousal symptoms, and its effect was apparent after controlling for the variance accounted for by gender (Level 1). Also, coping motives mediated the relation between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms. Although the cross-sectional nature of the research design does not allow us to definitively disentangle whether coping motives “develop” following smoking at higher rates per se (Baron & Kenny, 1986), the present data are consistent with a coping motives mediational model of anxiety symptoms among daily smokers. We attempted to strengthen confidence in this observation by evaluating an alternative model where anxious arousal symptoms mediated the relation between smoking rate and coping motives. Analyses indicated that smoking rate remained a significant predictor of coping motives after controlling for anxious arousal symptoms. While this result initially appeared to be inconsistent with mediation, post-hoc analyses revealed that anxious arousal symptoms partially mediated the relation between smoking rate and coping motives. Specifically, anxious arousal symptoms accounted for a portion of the unique variance in coping motives; however, anxious arousal symptoms did not fully explain (mediate) the relation between smoking rate and coping motives (see below for an expanded discussion of this finding).

A secondary aim of the present investigation was to explore a second mediational model. Namely, we sought to examine whether coping motives mediated the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate. Here, anxious arousal symptoms were significantly related to smoking rate. Specifically, anxious arousal symptoms accounted for 5.1% of the unique variance in smoking rate, above and beyond the variance accounted for by gender (Level 1). Moreover, coping motives mediated the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and smoking rate. Similar to the method described above, we attempted to strengthen confidence in this observation by evaluating an alternative model where smoking rate mediated the relation between anxious arousal symptoms and coping motives. Consistent with our initial findings, smoking rate did not mediate this relation.

Taken together, these mediational findings suggest that there may be a bidirectional effect between the studied variables where anxious arousal leads to greater smoking rate, which in turn contributes to elevations in anxious arousal. It is not possible to determine the causal processes potentially at play due to the cross-sectional and correlational nature of the research design. Despite this limitation, the present data suggest that coping motives are a possibly important mediational element in the smoking rate–anxiety linkage and serve as a potentially clinically important step in the elucidation of smoking–anxiety pathways. For example, a feed forward cycle may develop, whereby smoking is used as a coping strategy for managing aversive anxiety states in the short term yet paradoxically confers longer term risk for experiencing more frequent and intense anxious arousal symptoms (Zvolensky & Bernstein, 2005). Alternatively, for smokers with higher levels of anxiety symptoms, coping motives may lead to greater rates of cigarette use (Patton et al., 1998). From a clinical perspective, it is possible that coping-based motives for smoking may need to be addressed as part of cessation-based care for smokers with anxiety-related vulnerabilities or difficulties. For example, among smokers with high levels of anxious arousal symptoms, it may be necessary to focus educational and therapeutic strategies on the role of coping motives in smoking behavior. This type of targeted strategy may help such smokers more accurately learn about the nature of their smoking behavior and perhaps be better equipped to change it during efforts to stop smoking.

The present study has a number of limitations and related future directions that warrant further discussion. First, the present sample is limited in that it comprised a relatively homogenous group of adult smokers who volunteered to participate in a treatment-focused study. To rule out potential self-selection bias among persons with these characteristics and increase the generalizability of these findings, it will be important for researchers to draw from populations other than those included in the present study. Second, given that self-report measures were used as the assessment methodology, method variance due to the unimethod approach used may have contributed, in part, to the observed results. To address this concern, future research could use alternative assessment methodologies that incorporate multimethod approaches. For instance, future studies may choose to use an ecological momentary approach to assess smoking motives in “real time” (Shiffman, 2000). Finally, the cross-sectional nature of the current data precludes definitive conclusions regarding directional effects. Building from the current study, future work is poised to make further exciting inroads into this domain of study by exploring the empirical merit of more complex models. Here, it is possible that certain coping mechanisms may interact with specific smoking expectancies (beliefs about the effects of smoking; Brandon, Juliano, & Copeland, 1999; e.g., negative affect reduction) to explain rates of smoking. Thus, future prospective tests examining the mediational and moderational role of coping motives for smoking is a useful next research step.

Overall, the present study provides novel empirical information concerning putative bidirectional pathways among smoking rate, coping-based smoking motives, and anxious arousal symptoms among treatment-seeking adult smokers. Results indicated that coping motives mediated the relation between smoking rate to anxious arousal symptoms and anxious arousal symptoms to smoking rate. Although still preliminary, the present data globally highlight the important role of coping-based smoking motives in terms of better understanding linkages between smoking rate and anxious arousal symptoms.

Funding

Dr. S.S. is supported by a Killam Research Professorship from the Dalhousie University Faculty of Science. This work was supported by an Idea Research Grant from the Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (15683) awarded to Dr. S.S., Dr. M.J.Z, and D.S.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests for this research project.

Supplementary Material

References

- Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon TH, Juliano LM, Copeland AL. How expectancies shape experience. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Klein DF. Smoking and panic attacks: An epidemiologic investigation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:1141–1147. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Novak SP, Kessler RC. Daily smoking and the subsequent onset of psychiatric disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2004;34:323–333. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Strong DR. Distress tolerance and duration of past smoking cessation attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:180–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström K. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addictive Behaviors. 1978;3:235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldner MT, Babson KA, Zvolensky MJ. Smoking, traumatic event exposure, and posttraumatic stress: A critical review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:14–45. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin RD, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Cigarette smoking and panic attacks among young adults in the community: The role of parental smoking and anxiety disorders. Biological Psychiatry. 2005;58:686–693. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikard FF, Green DE, Horn D. A scale to differentiate between types of smoking as related to the management of affect. International Journal of Addictions. 1969;4:649–659. [Google Scholar]

- Isensee B, Wittchen HU, Stein MB, Höfler M, Lieb R. Smoking increases the risk of panic: Findings from a prospective community study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:692–700. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Pine DS, Klein DF, Kasen S, Brook JS. Association between cigarette smoking and anxiety disorders during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2348–2351. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.18.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasser K, Boyd JW, Woolhander S, Himmelstein DU, McCormick D, Bor DH. Smoking and mental illness: A population-based prevalence study. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;284:2606–2610. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.20.2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeish AC, Zvolensky MJ, Bucossi MM. Interaction between smoking rate and anxiety sensitivity: Relation to anticipatory anxiety and panic-relevant avoidance among daily smokers. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2007;21:849–859. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morissette SB, Tull MT, Gulliver SB, Kamholz BW, Zimering RT. Anxiety, anxiety disorders, tobacco use, and nicotine: A critical review of interrelationships. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:245–272. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton GC, Carlin JB, Coffey C, Wolfe R, Hibbert M, Bowes G. Depression, anxiety, and smoking initiation: A prospective study over 3 years. American Journal of Public Health. 1998;88:1518–1522. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.10.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piper ME, Piasecki TM, Federman BE, Bolt DM, Smith SS, Fiore MC, et al. A multiple motives approach to tobacco dependence: The Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68) Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:139–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA. Reliability of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addictive Behaviors. 1994;19:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JE, Ananda S, Jarvik ME. Cigarette smoking during anxiety-provoking and monotonous tasks. Addictive Behaviors. 1983;8:353–359. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(83)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell MAH, Peto J, Patel UA. The classification of smoking by factorial structure of motives. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1974;137:313–329. [Google Scholar]

- Sheets V, Braver SL. Organizational status and perceived sexual harassment: Detecting the mediators of a null effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1999;25:1159–1171. [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S. Real-time self-report of momentary states in the natural environment: Computerized ecological momentary assessment. In: Stone AA, Turkkan JS, Bachrach CA, Jobe JB, Kurtzman H, editors. The science of self-report: Implications for research and practice. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 277–296. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zeitlin SB, Samoluk SB. Examination of a three-dimensional drinking motives questionnaire in a young adult university student sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1996;34:61–71. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00036-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Weber K, Assenheimer JS, Clark LA, Strauss O, McCormick J. Testing a tripartite model. I. Evaluating the convergent and discriminant validity of anxiety and depression symptom scales. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1995;104:3–14. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.104.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Cigarette smoking and panic psychopathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2005;14:301–305. [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Feldner MT, Leen-Feldner EW, McLeish MC. Smoking and panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia: A review of the empirical literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:761–789. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Lejuez CW, Kahler CW, Brown RA. Panic attack history and smoking cessation: An initial examination. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:825–830. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB, McCreary BT. The impact of smoking on panic disorder: An initial investigation of a pathoplastic relationship. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2003;17:447–460. doi: 10.1016/s0887-6185(02)00222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvolensky MJ, Stewart SH, Vujanovic A, Gavric D, Steeves D. Anxiety sensitivity and anxiety and depressive symptoms in the prediction of early smoking lapse and relapse during smoking cessation treatment. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:323–331. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.