Abstract

Background. Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) account for the majority of end-stage renal disease in children (50%). Previous studies have mapped autosomal dominant loci for CAKUT. We here report a genome-wide search for linkage in a large pedigree of Somalian descent containing eight affected individuals with a non-syndromic form of CAKUT.

Methods. Clinical data and blood samples were obtained from a Somalian family with eight individuals with CAKUT including high-grade vesicoureteral reflux and unilateral renal agenesis. Total genome search for linkage was performed using a 50K SNP Affymetric DNA microarray. As neither parent is affected, the results of the SNP array were analysed under recessive models of inheritance, with and without the assumption of consanguinity.

Results. Using the non-consanguineous recessive model, a new gene locus (CAKUT1) for CAKUT was mapped to chromosome 8q24 with a significant maximum parametric Logarithm of the ODDs (LOD) score (LODmax) of 4.2. Recombinations were observed in two patients defining a critical genetic interval of 2.5 Mb physical distance flanked by markers SNP_A-1740062 and SNP_A-1653225.

Conclusion. We have thus identified a new non-syndromic recessive gene locus for CAKUT (CAKUT1) on chromosome 8q24. The identification of the disease-causing gene will provide further insights into the pathogenesis of urinary tract malformations and mechanisms of renal development.

Keywords: congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT), kidney development, total genome search for linkage, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, vesicoureteral reflux

Introduction

Congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract (CAKUT) occur in as many as 0.5% of all pregnancies and cover a wide range of structural and functional malformations that result from a defect in the development of the kidney and urinary tract [1,2]. CAKUT phenotypes include renal agenesis, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, prevesical stenosis, megaureter [3] and vesicoureteral reflux (VUR). They represent the most common cause for end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) in infants and children and account for ~50% of cases [4,5]. Urinary tract abnormalities occur in about three to six per 1000 live births. CAKUT can be inherited in an autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive or X-linked manner. In the dominant forms of CAKUT, there may be incomplete penetrance (skipping of a generation) or variable expressivity (varying severity and extent of abnormalities) [4]. As demonstrated in animal models, this phenotype variability, which ranges from VUR to renal agenesis, occurs on the basis of stochastic spatiotemporal differences during embryogenesis, when the ureteric bud grows out to meet and induce the metamorphogenic mesenchyme [6]. Dominant CAKUT may occur with isolated genitourinary involvement (non-syndromic CAKUT) or as part of over 200 multiorgan malformation syndromes that affect the central nervous, cardiovascular and skeletal systems (syndromic CAKUT). The overall incidence of CAKUT is difficult to estimate, because many cases are not diagnosed as they may appear non- or oligosymptomatic.

Mutations in renal developmental genes have been demonstrated in patients with various forms of CAKUT such as TCF2 (also called HNF1β) mutations in renal cysts and diabetes syndrome (RCAD) associated with maturity-onset diabetes of the young type 5 [7–9], EYA1, SIX1 and SIX5 mutations in branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome [10–13], PAX2 mutations in renal-coloboma syndrome [14,15], KAL1 mutations in Kallmann syndrome [16,17] and mutations in SALL1 in patients with Townes–Brocks syndrome (TBS) [18,19]. Recently, TCF2 mutations were identified in 25 of 80 children with renal hypodysplasia typically with cortical microcysts [20].

Previous studies have also suggested autosomal dominant loci for urinary tract malformation on chromosomes 1p13 [21], 6p21 [22–24], 19q13 [25], 10q26 [26] and 13q33–34 [27]. Mutations in angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE), angiotensin type-2 receptor (AT2R) [28] and FOXC1 [29] genes have been associated with an increased incidence of CAKUT. Also, mutations in Uroplakin IIIa (UPIII) are now known to be a rare cause of renal hypodysplasia (RHD) in humans [30]. In 2007, Lu et al., [31] illustrated that mutations in the ROBO2 gene can contribute to the pathogenesis of VUR/CAKUT in a small proportion of families. Furthermore, dominant mutations with incomplete penetrance have been demonstrated in BMP4 and SIX2 in patients with RHD. The roles of SIX2 and BMP4 have been implicated in the development of renal cysts, and defects in these proteins are shown to affect kidney development at multiple stages, leading to CAKUT [32]. Reduced BMP4 abundance in Gata2 hypomorphic mutant mice has also been shown to result in uropathies resembling human CAKUT [33].

Recently, Weber et al. performed a very interesting study in which they screened 99 unrelated patients with non-syndromic RHD for mutations in TCF2, PAX2, EYA1, SIX1 and SALL1 genes (European multicenter Effect of Strict Blood Pressure Control and ACE Inhibition on CRF Progression in Pediatric Patients/ESCAPE study) [34]. In the study, mutations or variants in these genes were detected in 17 (17%) of the patients. Fifteen percent of patients with RHD had mutations in TCF2 or PAX2, whereas abnormalities in EYA1, SALL1 and SIX1 were rare. This demonstrated that mutations in TCF2 or PAX2 are more frequently observed than mutations in other genes. Interestingly, they identified a SIX1 sequence variant in two siblings with renal-coloboma syndrome as a result of PAX2 mutation, which suggested an oligogenic inheritance in these cases with CAKUT. The variability in the severity of CAKUT between individuals with identical mutations also invokes the role of ‘modifier genes’ in the pathogenesis of the disease.

In this study, we performed a genome-wide search for linkage in Somalian kindred with 12 children, eight of whom presented with CAKUT. We identify a new non-syndromic recessive gene locus for CAKUT on chromosome 8q24 and report fine mapping to a 2.5-Mb genetic interval. This 2.5-Mb interval on chromosome 8q24 contains only one annotated gene called KH domain containing, RNA binding, signal transduction associated 3 (KHDRBS3). KHDRBS3 is an RNA-binding protein that plays a role in the regulation of alternative splicing and influences mRNA splice site selection and exon inclusion [34,36]. It may also play a role as a negative regulator of cell growth and inhibits cell proliferation. In the tissues, it is expressed in testis, skeletal muscle and brain. In the kidneys, it is expressed in podocytes and the glomerular epithelial cells [37].

Materials and methods

Patient recruitment

Blood samples and clinical data were obtained after informed consent from the parents and 12 children, eight of whom were affected with CAKUT. Ethnic origin of this family was Somalian. The pedigree is depicted in Figure 1. The affected individuals showed a diverse spectrum of CAKUT as follows: unilateral renal agenesis, kidney malrotation, severe ureteropelvic junction obstruction, duplication of the pyelon, VUR grades II–V, Hutch diverticulum and remnant ureteral ostium. The clinical findings in this family have been described previously [38]. However, while updating the pedigree data from the previous publication, it was revealed that Individual II-4 is also affected. Furthermore, Individuals II-3 and II-4 were found to be dizygotic twins. Diagnosis was established by pediatric nephrologists and pediatric urologists. The affected status in an individual was defined by the presence of at least two out of the following malformations: unilateral renal agenesis, severe ureteropelvic junction obstruction, VUR grade III or higher. The findings were confirmed by abdominal ultrasounds, intravenous urogram (IVU) and renal scans. Further, clinical characteristics of the affected individuals are shown in Table 1. Age at detection of CAKUT ranged from 0 to 10 years. The mother of the affected individuals is healthy with completely normal renal ultrasound. Though the father was unavailable for the study, he is also known to be healthy with no medical records or history of hospitalization.

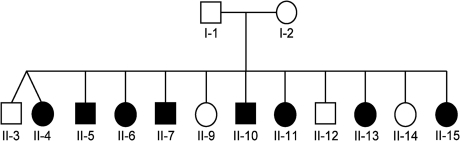

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of the Somalian kindred with CAKUT (circles denote females, squares denote males; filled symbols represent affected individuals; Individuals II-3 and II-4 are dizygotic twins).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics on the eight individuals with CAKUT from Somalian family

| Individual | Age of diagnosis | VUR | UPJO | Renal agenesis | Further findings | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left | Right | Left | Right | ||||

| II-4 | 9 years | + | + | ||||

| II-5 | 10 years | + | + | Duplicate left pyelon | |||

| II-6 | 6 years | + | + (left) | ||||

| II-7 | 1 month | +a | + (left) | Remnant left ureteral ostium | |||

| II-10 | in utero | + | + | ||||

| II-11 | 5 days | + | + | ||||

| II-13 | 5 days | + | + | ||||

| II-15 | 1 day | + | + | Right Hutch diverticulum, malrotated left kidney | |||

VUR—vesicoureteral reflux, UPJO—ureteropelvic junction obstruction.

Presumed diagnosis before surgery in Somalia.

Genome-wide linkage analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated from blood samples according to manufacturer's instructions (Puregene Gentra Systems). For the genome-wide search for linkage, DNA was available from eight affected siblings, three apparently unaffected siblings and the parents. No DNA was available from Individual II-3. Family history revealed that the maternal grandmother, her brother and her sister were also affected by an unspecified urinary tract malformation. Clinical data from these individuals were unavailable. We performed genome-wide scans for linkage on the eight affected children and both parents using a 50K single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays (GeneChip) from Affymetrix, Inc (50K Hind Array). As neither parent is affected and as it is not known whether they are consanguineous, the results of the genome-wide search for linkage were analysed under a recessive model of inheritance alternatively, with and without the assumption of consanguinity.

Since many cases of urinary tract malformations are oligosymptomatic and therefore unrecognized due to incomplete penetrance or variable expressivity [4], only affected individuals were evaluated for Logarithm of the ODDs (LOD) score analysis, and apparently, unaffected individuals were coded as unknown affected status (‘affecteds-only strategy’). Parametric linkage analysis was performed by a modified version of the program GENEHUNTER 2.1 [39,40] and by the program ALLEGRO [41]. Haplotypes were reconstructed with ALLEGRO and presented graphically with HaploPainter [42]. All data handling was performed using the graphical user interface ALOHOMORA [43].

Mutation analysis

For all the affected-only individuals of this family, exon PCR and direct sequencing was performed in the candidate gene KHDRBS3, the only annotated gene present in the 2.5-Mb interval on chromosome 8q24. Sequences were aligned and evaluated with the SEQUENCHER™ software (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI).

Results

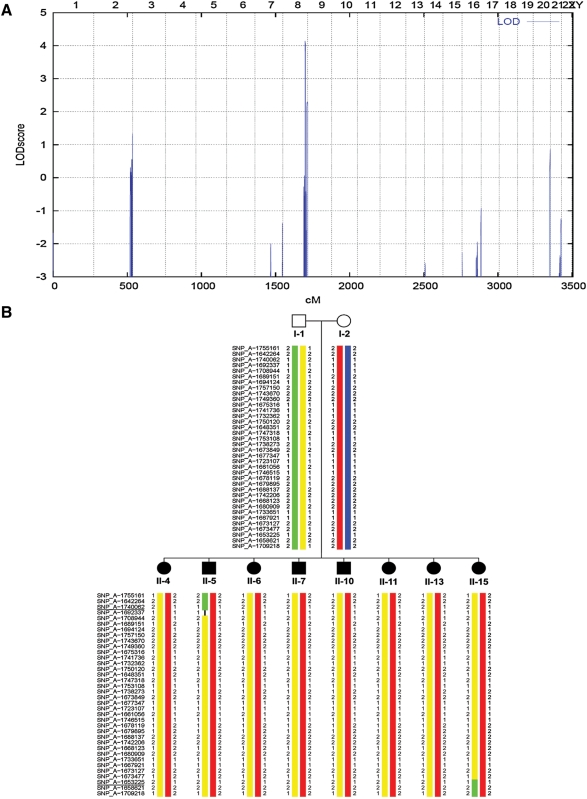

Haplotype analysis data from the genome-wide search for linkage excluded the known loci for urinary tract malformations on chromosomes 1p13 [21], 6p21 [22–24], 19q13 [25], 10q26 [26], 13q33–34 [27] and the chromosomal regions containing candidate genes such as EYA1, SIX1, SIX5, TCF2, PAX2, BMP4, SIX2, UPIII, SALL1 and others. The genome-wide search under the non-consanguineous recessive model yielded a single region with a significant maximum parametric LOD score of (LODmax = 4.2) on chromosome 8q24 (Figure 2A). There was no additional alternative suggestive locus anywhere in the genome (Figure 2A). Haplotype analysis revealed that in the region of chromosome 8q, all eight affected children carried the same maternal haplotype (Figure 2B). The proximal flanking marker SNP_A-1740062 and distal flanking marker SNP_A-1653225 were defined by recombination events in Individuals II-5 and II-15, respectively, which delimit a critical genetic interval of 2.5-Mb physical distance. No mutation was found by directly sequencing all exons of the only annotated gene, KHDRBS3, within the region (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

(A) Parametric multipoint LOD score profile across the human genome, calculated in the eight affected individuals for a non-consanguineous model. Parametric LOD scores are on the y-axis in relation to genetic position on the x-axis. Human chromosomes are concatenated from p-terminal (left) to q-terminal (right) on the x-axis. Note the significant maximum LOD score of 4.2 on human chromosome 8, defining a new gene locus (CAKUT 8) for CAKUT on chromosome 8q24. (B) Haplotypes of the affected children and parents on chromosome 8q24. Only data from affected children are shown. All children have inherited the same paternal (represented in yellow) and maternal (represented in red) haplotype. Recombination breakpoints in Individuals II-5 and II-15 define the proximal and distal boundaries, respectively, of the critical interval. Flanking markers SNP_A-1740062 and SNP_A-1653225 are underlined.

Discussion

Employing an SNP array mapping strategy, we identified by genome-wide linkage analysis a new gene locus for non-syndromic recessive CAKUT, mapping it to chromosome 8q24. According to the University of California Santa Cruz Genome Browser, the interval between markers SNP_A-1740062 and SNP_A-1653225 spans a physical distance of approximately 2.5 Mb.

In this Somalian family, as eight out of 12 children are affected, the mode of inheritance is more likely to be an autosomal dominant trait, which would then imply that one of the parents was affected. However, both, the father and the mother of the affected children, are known to be healthy with no clinical history. Their consanguinity is also unknown. In light of healthy parents, we thus consider the mode of inheritance as an autosomal recessive trait and believe that the high rate of affected children is the result of a random genetic effect.

In addition to the 12 children shown in the pedigree (Figure 1), there are four more non-affected children who are from a different father (data not shown). The fact that all four children from a different father are healthy also supports the autosomal recessive model of inheritance of the disease.

We thus consider an autosomal dominant or codominant transmission (with incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity in the parents) unlikely, although based on the data presented, it cannot be ruled out with absolute certainty. The evaluation of the total genome search for linkage based on this dominant model of inheritance did not yield a significant LOD score (data not shown).

In summary, by total genome search for linkage, we mapped a new recessive locus (CAKUT1) for CAKUT to chromosome 8q24. The critical genetic region is flanked by markers SNP_A-1740062 and SNP_A-1653225 by the criterion of lack of consanguinity in parents. Mutational analysis of KHDRBS3, the only known gene within the 2.5-Mb interval, did not reveal any mutations. There is a slight possibility that we might be missing a disease-causing mutation in the promoter region of this gene, but it is very unlikely. Large-scale analysis of the entire critical genetic region will be necessary to identify the disease-causing gene. The identification of the gene mutated in the CAKUT phenotype will provide further insights into the molecular basis of urinary tract infections and into the development of the kidney and urinary tract.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank this family for participating in this study. F.H. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, a Frederick G.L. Huetwell Professor for the Cure and Prevention of Birth Defects and a Doris Duke distinguished clinical scientist and is supported by the National Institutes of Health (HD045345-01).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

References

- 1.Queisser-Luft A, Stolz G, Wiesel A, et al. Malformations in newborn: results based on 30,940 infants and fetuses from the Mainz congenital birth defect monitoring system (1990–1998) Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2002;266:163–167. doi: 10.1007/s00404-001-0265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schedl A. Renal abnormalities and their developmental origin. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:791–802. doi: 10.1038/nrg2205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuwayama F, Miyazaki Y, Ichikawa I. Embryogenesis of the congenital anomalies of the kidney and the urinary tract. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17, Suppl 9:45–47. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.suppl_9.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pohl M, Bhatnagar V, Mendoza SA, et al. Toward an etiological classification of developmental disorders of the kidney and upper urinary tract. Kidney Int. 2002;61:10–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woolf AS. A molecular and genetic view of human renal and urinary tract malformations. Kidney Int. 2000;58:500–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davies JA. Mesenchyme to epithelium transition during development of the mammalian kidney tubule. Acta Anat (Basel) 1996;156:187–201. doi: 10.1159/000147846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bingham C, Ellard S, Allen L, et al. Abnormal nephron development associated with a frameshift mutation in the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor-1-beta. Kidney Int. 2000;57:898–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.057003898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bingham C, Bulman MP, Ellard S, et al. Mutations in the hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta gene are associated with familial hypoplastic glomerulocystic kidney disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:219–224. doi: 10.1086/316945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bellanne-Chantelot C, Chauveau D, Gautier JF, et al. Clinical spectrum associated with hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta mutations. Ann Intern Med. 2004;6:510–517. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-140-7-200404060-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelhak S, Kalatzis V, Heilig R, et al. Clustering of mutations responsible for branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome in the eyes absent homologous region (eyaHR) of EYA1. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:2247–2255. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.13.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Kimberling WJ, Weston MD, et al. Identification of three novel mutations in human EYA1 protein associated with branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Hum Mutat. 1998;11:443–449. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1998)11:6<443::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruf RG, Xu PX, Silvius D, et al. SIX1 mutations cause branchio-oto-renal syndrome by disruption of EYA1-SIX1-DNA complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8090–8095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308475101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoskins BE, Cramer CH, Silvius D, et al. Transcription factor SIX5 is mutated in patients with branchio-oto-renal syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:800–804. doi: 10.1086/513322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sanyanusin P, Schimmenti LA, McNoe LA, et al. Mutation of the PAX2 gene in a family with optic nerve colobomas, renal anomalies and vesicoureteral reflux. Nat Genet. 1995;9:358–364. doi: 10.1038/ng0495-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanyanusin P, McNoe LA, Sullivan MJ, et al. Mutation of PAX2 in two siblings with renal-coloboma syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:2183–2184. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.11.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Izumi Y, Tatsumi K, Okamoto S, et al. A novel mutation of the KAL1 gene in Kallmann syndrome. Endocr J. 1999;46:651–658. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.46.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagata K, Yamamoto T, Chikumi H, et al. A novel interstitial deletion of KAL1 in a Japanese family with Kallmann syndrome. J Hum Genet. 2000;45:237–240. doi: 10.1007/s100380070033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohlhase J, Wischermann A, Reichenbach H, et al. Mutations in the SALL1 putative transcription factor gene cause Townes-Brocks syndrome. Nat Genet. 1998;18:81–83. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweetman D, Smith T, Farrell ER, et al. The conserved glutamine-rich region of chick csal1 and csal3 mediates protein interactions with other spalt family members. Implications for Townes-Brocks syndrome. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:6560–6566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209066200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulinski T, Lescure S, Beaufils S, et al. Renal phenotypes related to hepatocyte nuclear factor-1beta (TCF2) mutations in a pediatric cohort. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:497–503. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feather SA, Malcolm S, Woolf AS, et al. Primary, nonsyndromic vesicoureteric reflux and its nephropathy is genetically heterogeneous, with a locus on chromosome 1. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1420–1425. doi: 10.1086/302864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groenen PM, Vanderlinden G, Devriendt K, et al. Rearrangement of the human CDC5L gene by a t(6;19)(p21;q13.1) in a patient with multicystic renal dysplasia. Genomics. 1998;49:218–229. doi: 10.1006/geno.1998.5254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Izquierdo L, Porteous M, Paramo PG, et al. Evidence for genetic heterogeneity in hereditary hydronephrosis caused by pelvi-ureteric junction obstruction, with one locus assigned to chromosome 6p. Hum Genet. 1992;89:557–560. doi: 10.1007/BF00219184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sengar DP, Rashid A, Wolfish NM. Familial urinary tract anomalies: association with the major histocompatibility complex in man. J Urol. 1979;121:194–197. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56716-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Groenen PM, Garcia E, Debeer P, et al. Structure, sequence, and chromosome 19 localization of human USF2 and its rearrangement in a patient with multicystic renal dysplasia. Genomics. 1996;38:141–148. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogata T, Muroya K, Sasagawa I, et al. Genetic evidence for a novel gene(s) involved in urogenital development on 10q26. Kidney Int. 2000;58:2281–2290. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vats KR, Ishwad C, Singla I, et al. A locus for renal malformations including vesico-ureteric reflux on chromosome 13q33–34. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1158–1167. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005040404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rigoli L, Chimenz R, di Bella C, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme and angiotensin type 2 receptor gene genotype distributions in Italian children with congenital uropathies. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:988–993. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000145252.89427.9E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakano T, Niimura F, Hohenfellner K, et al. Screening for mutations in BMP4 and FOXC1 genes in congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract in humans. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2003;28:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schönfelder E, Knüppel T, Tasic V, et al. Mutations in Uroplakin IIIA are a rare cause of renal hypodysplasia in humans. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;47:1004–1012. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.02.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu W, van Eerde AM, Fan X, et al. Disruption of ROBO2 is associated with urinary tract anomalies and confers risk of vesicoureteral reflux. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:616–632. doi: 10.1086/512735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weber S, Taylor JC, Winyard P, et al. SIX2 and BMP4 mutations associate with anomalous kidney development. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:891–903. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoshino T, Shimizu R, Ohmori S, et al. Reduced BMP4 abundance in Gata2 hypomorphic mutant mice result in uropathies resembling human CAKUT. Genes Cells. 2008;13:159–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber S, Moriniere V, Knüppel T, et al. Prevalence of mutations in renal developmental genes in children with renal hypodysplasia: results of the ESCAPE study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:2864–2870. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006030277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stoss O, Olbrich M, Hartmann AM, et al. The STAR/GSG family protein rSLM-2 regulates the selection of alternative splice sites. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8665–8673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venables JP, Vernet C, Chew SL, et al. T-STAR/ETOILE: a novel relative of SAM68 that interacts with an RNA-binding protein implicated in spermatogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:959–969. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.6.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen T, Boisvert FM, Bazett-Jones DP, et al. A role for the GSG domain in localizing Sam68 to novel nuclear structures in cancer cell lines. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3015–3033. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.9.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasch A, Hoefele J, Grimminger H, et al. Multiple urinary tract malformations with likely recessive inheritance in a large Somalian kindred. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:3172–3175. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kruglyak L, Daly MJ, Reeve-Daly MP, et al. Parametric and nonparametric linkage analysis: a unified multipoint approach. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:1347–1363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Strauch K, Fimmers R, Kurz T, et al. Parametric and nonparametric multipoint linkage analysis with imprinting and two-locus-trait models: application to mite sensitization. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1945–1957. doi: 10.1086/302911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gudbjartsson DF, Jonasson K, Frigge ML, et al. Allegro, a new computer program for multipoint linkage analysis. Nat Genet. 2000;25:12–13. doi: 10.1038/75514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Thiele H, Nurnberg P. HaploPainter: a tool for drawing pedigrees with complex haplotypes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:1730–1732. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruschendorf F, Nurnberg P. ALOHOMORA: a tool for linkage analysis using 10K SNP array data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:2123–2125. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]