INTRODUCTION

According to Drug Abuse Warning Network data for 2006, marijuana was involved in 209,563 emergency department (ED) visits and was the most frequently mentioned drug of abuse reported for adolescents.1 Heavy marijuana use is a risk factor for injury and illness.2, 3 Regular use in early adolescence has been associated with greater likelihood of persistent and dependent daily use in adulthood and poor school, job and relationship outcomes.4 Children who are already using drugs by age 12 or 13 typically become involved with marijuana and then advance to other illegal drugs,5 and those who smoke marijuana before age 17 are from 1.6 to 6 times more likely to report abuse of or dependence on alcohol or an illicit drug later on in life.6 In a 10-year follow-up of 1,943 14–15 year olds in an Australian community cohort, weekly or more frequent cannabis use predicted a sevenfold increase in daily use at age 20, and heavy cannabis use in adolescence was associated with greater likelihood of cannabis dependence, cigarette smoking, illicit substance abuse, poor education and training outcomes, and less likelihood of being in a relationship in young adulthood.7

Motivational interventions for alcohol and injury among adolescents have been studied in the ED, 8–10 and marijuana interventions have been shown to be effective in community settings,11 but marijuana interventions for adolescents in the ED setting have not yet been reported. In this preliminary study, we test the effectiveness of a brief motivational intervention, conducted by peer educators during a pediatric ED visit (PED), to negotiate abstinence and/or reductions in marijuana use and related consequences among 14–21 year olds.

METHODS and MATERIALS

Study Design

This was a prospective randomized, controlled blinded trial of screening and brief intervention (SBI) for youth and young adults ages 14–21 presenting to the PED from January, 2005–March, 2007. Randomization was to three groups (intervention, standard assessed control and non-assessed control) in order to test the feasibility of identifying potential assessment reactivity effects. The study was approved by the BUMC Institutional Review Board and written informed consent was obtained on all subjects, and the study received a certificate of confidentiality at both federal and state levels. The study was monitored yearly by a Data Safety Monitoring Board.

Study Setting and Population

The study took place in the Pediatric Emergency Department (PED) of an inner-city, academic hospital. The PED is a component of a level I trauma and has a yearly census of approximately 29,000 patients from birth through the 21st birthday. Of these, 8,000 are between the ages of 18–21. The patient population is 60% female and ethnically and culturally diverse: 46% African American; 19% Hispanic, 12% white, 7% Cape Verdean and 5% Asian. Four-fifths speak English at home.

Screening

PED patients aged 14–21 years old who gave verbal consent were screened seven days per week from 8am–10pm in the privacy of either a room adjacent to the waiting room, the examining room, or at the bedside if admitted to the hospital. The screening was conducted as part of a larger randomized, controlled trial for an alcohol intervention study for youth and young adults. The screening instrument, “Youth and Young Adult Health and Safety Needs Survey,” included risk questions from the CDC Youth Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (YBRFS). All patients presenting during the hours of screening were invited to participate in the study if they: 1) did not report “at risk alcohol use”; 2) smoked marijuana ≥3 times in the last 30 days; 3) or reported risky behavior temporally associated with marijuana use such as driving a car or riding in a car with someone who was smoking marijuana, getting in a fight, being injured, or having unplanned or unprotected sex after smoking marijuana. The cutoff of ‘3 to 5 days per month’ on the YBRFS question was selected because the goal of an SBIRT intervention is to address early use, in contrast to studies of youth in treatment, where 5 days a month is often used as the criterion for eligibility, and the goal is closer to tertiary prevention.

Patients were included in the study if they could communicate in English, Spanish, Haitian Creole or Cape Verdean Creole, were alert and oriented to person, time and place, and could give autonomous informed consent or assent if they were below the age of 18. Patients were excluded if they 1) could not be interviewed in privacy from accompanying family members; 2) planned to leave the area in the next three months; 3) could not provide reliable contact information to complete the follow-up procedures; 4) were currently in a residential substance abuse treatment facility; 5) were in custody or institutionalized; or 6) presented for a rape exam or psychiatric evaluation for suicide precautions. Eligible patients were asked to repeat and explain the key elements of the study prior to signing informed consent, and their responses were documented on a checklist.

Randomization

Enrollees were randomized to three conditions: Intervention (I), Assessed Control (AC) and Non-Accessed Control (NAC). Randomization was based on computer-generated random numbers in blocks of 100 stratified by age group (14–17 and 18–21). A double opaque envelope system enabled blinding of the research assistants who performed the assessment to randomization status. The first envelope, with randomization to assessed (I, AC) or non-assessed (NAC) status, was opened immediately after enrollment. A second envelope indicating I or AC status was not opened until after assessment. Participants were cautioned not to reveal to the research assistants at the time of follow-up whether or not they had received any further testing after enrollment.

Procedures

The NAC group received only brief written information about risks associated with marijuana use along with a list of community resources and adolescent treatment facilities, and an appointment for follow-up in one year. The AC group received a battery of standard assessment instruments (see below), the written handout, and appointments to return at three months and one year. After assessment, the I group received a 20–30 minute structured conversation delivered by a peer educator in addition to the written materials, appointments for three months and one year, and a booster telephone call at 10 days post-enrollment.

Assessment Instruments

Measures designed to assess outcomes

The Timeline FollowBack Calendar (TLFB) was used to obtain reliable and valid self-report data on the number of days of marijuana use and days of getting high in the 30 days. The I and AC groups reported use prior to enrollment and again at three and 12 months; the NAC group reported use at 12 months only. The TLFB uses calendars, holidays and special events to trigger memory and is reported to reduce error in retrospective self-report; validity and reliability for recall of marijuana use have been well established. 12, 13

The Adolescent Injury Checklist (AIC), created for alcohol but adapted as a record of marijuana associated injury, was conducted at baseline for the I and AC group. The AIC has an internal consistency of α = .67 for injury occurrence and α =.62 for injury requiring medical care.14

Measures administered to assess comparability of randomization groups

Because this study was a pilot with a small sample, several instruments were used to measure variables that have been shown to moderate substance abuse associated risks, e.g. depression, global risk-taking personality propensity, and prior exposure to violence associated with PTSD symptoms.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (adolescent version) or PHQ-A Depression scale is a 15 item self-report questionnaire designed for the purpose of assessing mood disorders among adolescents seen in primary care clinic. This scale has good concurrent validity testing against DSM-IV diagnoses.15 The I and AC groups completed this questionnaire at baseline.

The Simpson and Joe Risk-taking Scale, conducted at baseline for I and AC groups, has been shown to be a strong predictor of self-reported drug use. This scale has an acceptable test-retest reliability and good psychometric properties (internal consistency of α =.77 and GFI of .97.16

The PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) is a 17 item inventory that assesses the specific symptoms that make up the post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis. Test-retest reliability is excellent at .96 and diagnostic efficiency is .90.17 The I and AC groups completed this questionnaire at baseline.

Intervention

Interventions were delivered by peer educators who were under 25 years of age and spoke Spanish, Haitian Creole and Cape Verdean as well as English; all except one had a bachelor’s degree. The peer educators received one month of training consisting of slide presentations on human subjects protections, study protocol, adolescent development, rationale for intervention, and elements of motivational interviewing style. The intervention algorithm was taught using video demonstrations, role playing with simulated patients, and review of video and audio tapes of practice interviews.

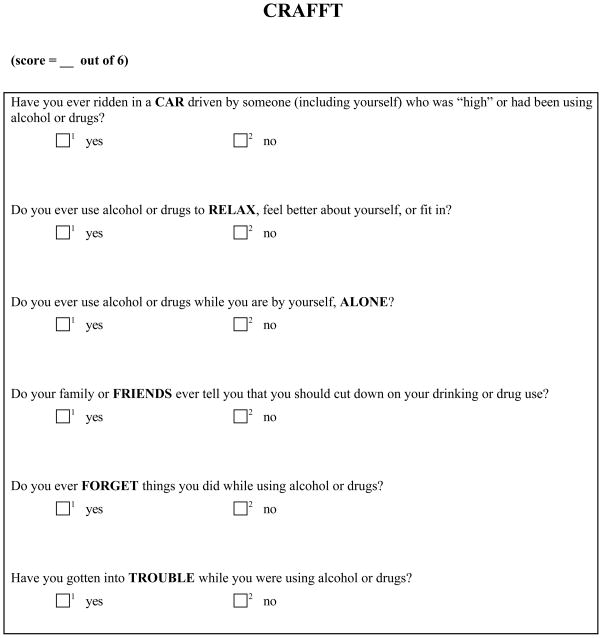

The intervention format, successfully tested with adults in a cocaine and heroin study 18, was adapted to incorporate both developmental and contextual aspects of young people’s lives, and included an emphasis on assessing and enhancing sources of resilience. Content, based on research by Miller,19 Rollnick,20 and Monti, 8–10 consisted of the following components: 1) obtaining engagement and permission to raise subject; 2) establishing context (“What’s a typical day in your life like?”); 3) offering brief feedback, information and norms, specific to age and gender, and exploring pros and cons of use: eliciting ‘change talk’ and using the CRAFFT 21 questions and a Readiness to Change ruler to reinforce movement toward behavior change); 4) generating a menu of options; 5) calling up assets/instilling hope; 6) discussing the challenges of change; and ending in a 7) prescription for change, generated by the subject and referrals to community resources and specialty drug treatment services. Patients with CRAFFT scores of ≥2 (see figure 1) were advised that the score may indicate high risk and a possible need for further evaluation and treatment. All intervention patients received a five to ten minute booster phone call during which the interventionist reviewed the elements of the change plan, inquired about any progress towards change, and offered further referrals if those originally provided had not been possible to accomplish.

Figure 1.

The CRAFFT Questions21

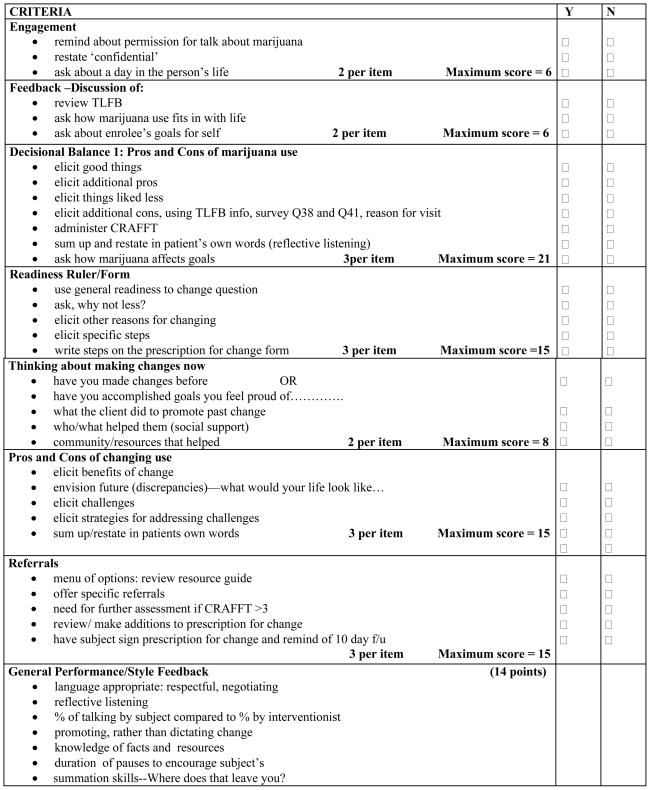

Adherence to the intervention algorithm was assessed weekly by the investigators and the project coordinator. The tapes were scored using an adherence check list of the key elements of the intervention (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The Adherence Scoring Checklist (Passing score 80/100 possible points)

Follow-up Procedures

Follow-up occurred at three and twelve months for the I and AC groups and at 12 months only for the NAC group. Participants received $10 at enrollment and $35 at subsequent follow-up visits. To minimize attrition, participants received written and telephone reminders, including e-mail and text messages, at intervals prior to appointments, using standard methods for contacting friends, family members, caseworkers and agencies.22,23

Definitions

Abstinence as defined as zero marijuana consumption (smoke in any form including passive smoke and tokes, or consumables) in the last 30 days, as recorded on the Timeline Followback. For this preliminary study, we did not attempt to quantify marijuana consumption. Use was therefore defined as any use, from tokes to blunts or quantities in baked goods, as distinguished from the cut-off of use at least three days out of the last thirty that was used as a criterion for enrollment.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcomes included: abstinence at 12 months and changes in patterns of marijuana use measured by TLFB; intention to stop using, cut back on use, or change the circumstances of use; and reduction of consequences and high risk behaviors related to marijuana use.

Data Analysis

Power considerations

Large differences between study groups would be needed for adequate power to show significance. However this is a pilot study. Planned enrollment samples of n=70 per group and an anticipated 25% loss to follow-up by 12 months yield expected analysis samples of n=52 per group at 12 months. Given an abstinence rate of 20% in the assessed control group, an abstinence rate of 45.5% in the intervention group (corresponding to an odds ratio of 3.30) would be needed for 80% power.

Primary outcomes

The I and AC groups were compared at 3 and 12 months to test the effects of brief intervention on abstinence and days of consumption, adjusting only for baseline levels of marijuana consumption. Because this was a pilot study with a small sample, it was not possible to control for other factors with the potential to play a role. Demographic and marijuana use variables for age, gender, race and language were analyzed to determine comparability of groups, using Chi square analysis for categorical variables, t-test for continuous variables, and Wilcoxon rank-sum for non-normal distributions. Two tailed t-test for means and Wilcoxon rank test for medians were used at the 3-month and 12-month follow-up to analyze differences from baseline in the number of days in the last 30 that marijuana was used. General estimating equation (GEE) methods were used to analyze the changes in marijuana consumption and risk behaviors in a pooled analysis using both 3 and 12 month data, controlling for baseline data. GEE methods also examined intention to change use at 3 and 12 months, without adjusting for baseline intentions.

Secondary outcome

To evaluate assessment reactivity, the AC and NAC groups were compared at 12 months. Preliminary analyses examined the feasibility of including a non-assessed control group by examining loss-to-follow-up across these two study groups. Differences in 12 month marijuana use, controlling for available screening data on level of baseline use, through multiple regression analysis explored potential assessment reactivity in the AC group.

RESULTS

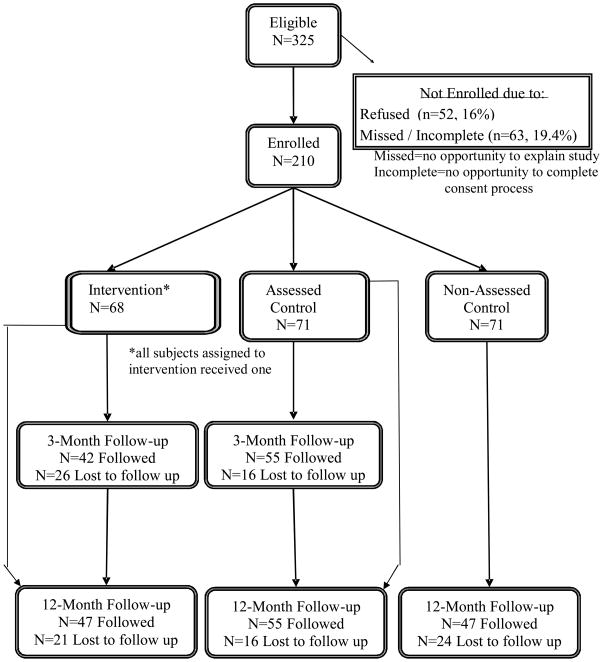

Among 7,804 PED patients screened, 325 met eligibility criteria and 210 (65% of eligibles) were enrolled and randomized (I n=68, AC n=71, NAC n=71). Seventy percent completed the three month follow-up and 71% completed the 12-month follow-up (see Figure 3, Consort diagram).

Figure 3.

CONSORT Diagram

The enrolled group included a greater proportion of patients under 17 years of age than did the group of eligibles (28% vs 23%), but there were no significant differences at baseline in gender, race, or language spoken at home. Among the three randomization groups, there were no significant differences at baseline in age, gender, race, language, or pattern of marijuana use. Among the I and AC groups, there were no significant differences in baseline scores for PTSD, depression, risk-taking, or marijuana-related injury. (Baseline characteristics of I and AC groups are reported in Table 1, where p values are presented to demonstrate equivalence of groups.)

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics: Intervention (I) and Assessed Control (AC) Groups.

| I (n=68) | AC (n=71) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age | |||

| ≤ 17 | 20 (29.4) | 21 (29.6) | 0.983 |

| ≥ 18 | 48 (70.6) | 50 (70.4) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 25 (36.8) | 23 (32.4) | 0.588 |

| Female | 43 (63.2) | 48 (67.6) | |

| Race | |||

| Black/African American | 57 (83.8) | 55 (77.5) | 0.394* |

| Hispanic/Latino | 7 (10.3) | 11 (15.5) | |

| White | 3 (4.4) | 5 (7.0) | |

| Other | 1 (1.5) | 0 | |

| Primary language | |||

| English | 62 (91.2) | 62 (87.3) | 0.796* |

| Other: Spanish, Haitian Creole, Cape Verdean | 6 (8.8) | 9 (12.7) | |

| Marijuana use in last 30 days | |||

| 1–9 times | 26 (38.3) | 30 (42.3) | 0.629 |

| 10 or more times | 42 (61.7) | 41 (57.7) | |

| PTSD + | 22 (32.4) | 18 (25.4) | 0.362 |

| Depression + | 10 (15.2) | 6 (8.5) | 0.222 |

| Risk-taking + | 10 (14.7) | 13 (18.3) | 0.568 |

| Marijuana use prior to injury | 8 (11.8) | 9 (12.7) | 0.870 |

P-values from chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests (Fisher’s exact test denoted by an asterisk).

Although there were no significant differences at baseline of risk behaviors, the I group used marijuana on more days per month (19 (sd 10.9)) than the AC group (15.3 (sd 10.1) as measured by TLFB (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Risk Factors by Randomization Group: Intervention (I) and Assessed Control (AC) Groups.

| I (n=68) | AC (n=71) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Times per month using marijuana (TLFB) | 19.0 (10.9) | 15.3 (10.1) | 0.039 |

| In the last 30 days: | N (%) | N (%) | p-value |

| Got in fight after using marijuana | 3 (4.4) | 3 (4.3) | 1.0* |

| Drove a car after using marijuana | 9 (13.2) | 10 (14.7) | 0.804 |

| Rode in a car with person who was drunk/high | 16 (23.5) | 12 (17.4) | 0.373 |

| Got injured after using marijuana | 2 (2.9) | 0 | 0.241* |

| Got arrested after using marijuana | 1 (1.5) | 1 (1.5) | 1.0* |

| Had sex without a condom after using marijuana | 9 (13.2) | 9 (12.9) | 0.980 |

For measurement variables, p-value from t-test. For categorical variables, p-values from chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests (Fisher’s exact test denoted by an asterisk).

Intervention effects

All scored Adherence Checklists met the required cut-off of 80 out of 100 points.

Abstinence (see Table 3)

Table 3.

Comparison by randomization group of marijuana abstinence (among smokers) at 3 and 12 month follow-up by Timeline Followback 30 day recall.

| I | AC | Odds Ratio | 95 % CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 3 months | (n=42) | (n=55) | |||

| abstinent | 6 | 7 | 1.15 | 0.36, 3.73 | 0.814 |

| not abstinent | 35 | 47 | |||

| At 12 months | (n=47) | (n=55) | |||

| abstinent | 21 | 12 | 2.89 | 1.22, 6.84 | 0.014 |

| not abstinent | 26 | 43 | |||

There was no significant difference in marijuana use in the past 30 days at the three-month follow-up between the I and the AC groups. At the 12 month follow-up, however, 45% of the intervention group were marijuana abstinent as measured by TLFB, compared to 22% of the assessed controls (OR 2.89, 95%CI 1.22, 6.84, p<0.014).

Although the I and the AC groups were similar in demographics and marijuana use at baseline, and similar in demographics at follow-up (see Table 4), there was a differential loss in numbers followed between the two groups at 12 months. For this reason we ran a sensitivity analysis, assuming the position that all subjects lost to follow-up were not abstinent (see Table 5). Although the results of this analysis only bordered on significance (p=.053, 95%CI 0.98, 4.92), the odds ratio did remain above 2 in this worst-case scenario.

Table 4.

Comparison of baseline factors between those followed and those lost to follow-up at 12 months.

| I (n=68) | AC (n=71) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Followed n=47 | Lost to f/u n=21 | p-value | Followed n=55 | Lost to f/u n=16 | p-value | |

| Age | ||||||

| ≤17 | 31.9 | 23.8 | 0.498 | 34.6 | 12.5 | 0.123 |

| ≥18 | 68.1 | 76.2 | 65.5 | 87.5 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 70.2 | 47.6 | 0.074 | 67.3 | 68.8 | 0.912 |

| Male | 29.8 | 52.4 | 32.7 | 31.3 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| Black | 85.1 | 81.0 | 0.727 | 76.4 | 81.2 | 1.0 |

| Non-black | 14.9 | 19.0 | 23.6 | 18.8 | ||

| Marijuana use past 30 days | ||||||

| 1–9 times | 63.8 | 57.1 | 56.4 | 62.5 | ||

| ≥10 times | 36.2 | 42.9 | 0.600 | 43.6 | 37.5 | 0.662 |

P-values from chi-square tests.

Table 5.

Sensitivity analysis assuming worst-case scenario that all subjects lost to follow-up were non-abstinent

| At 12 months | I (n=68) | AC (n=71) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinent | 21 | 12 | 2.2 |

| Non-abstinent | 47 (including 21 lost to f/u) | 59 (including 16 lost to f/u) | 0.98, 4.92 (p=.053) |

Reductions in consumption (see Table 6)

Table 6.

Outcomes by Randomization Group: Days per month using Marijuana using Timeline Follow-back.

| Intervention |

Assessed Control |

I vs AC p-value |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) | N | Mean (SD) | ||

| Baseline | 68 | 19.0 (10.9) | 71 | 15.3 (10.1) | 0.039 |

| 3-month follow up | 41* | 14.2 (10.8) | 54* | 13.7 (11.2) | 0.837 |

| Change baseline to 3-month | 41 | −5.0 (9.1) | 54 | −0.8 (9.9) | 0.039 |

| 12-month follow up | 47 | 11.0 (10.7) | 55 | 13.2 (11.7) | 0.352 |

| Change baseline to 12-month | 47 | −7.1 (11.2) | 55 | −1.8 (11.9) | 0.024 |

| Baseline among those with 3-mo. f/u | 41 | 19.1 (11.2) | 54 | 14.5 (9.7) | 0.035 |

| 3-month follow up | 41 | 14.2 (10.8) | 54 | 13.7 (11.2) | 0.837 |

| Change baseline to 3-month | 41 | −5.0 (9.1) | 54 | −0.8 (9.9) | 0.039 |

| Decline in marijuana use greater in the intervention group by −4.2 days/mo. (95% CI −8.1, −0.3) | |||||

| Baseline among those with 12-mo. f/u | 47 | 18.1 (10.8) | 55 | 15.0 (10.4) | 0.142 |

| 12-month follow up | 47 | 11.0 (10.7) | 55 | 13.2 (11.7) | 0.352 |

| Change baseline to 12-month | 47 | −7.1 (11.2) | 55 | −1.8 (11.9) | 0.024 |

| Decline in marijuana use greater in the intervention group by −5.3 days/mo. (95% CI −10, −0.6) | |||||

P-values from t-tests.

one person in each group has 3 month follow-up form but no 3 month timeline follow-back

On univariate analysis comparing TLFB mean use at baseline (BL) to data from the 12-month follow-up visit, the I group had four fewer days of use from BL at three months and six fewer days of use from BL at 12 months than ACs, with similar results from both t-test and Wilcoxon rank-sum analyses.

Consumption and risk factors adjusted for baseline levels (see Table 7)

Table 7.

GEE analyses, comparing I and AC Groups: Outcomes at 3 and 12 months

| BL, 3 Mo. 12 Mo. |

I N=55 N=42 N=47 |

AC N=64 N=55 N=55 |

Adjusted Odds Ratio comparing I to AC | p-value for AOR | Main Effect p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Timeline Followback (TLFB) Smoked Marijuana 1+ days/month |

BL | 55 (100) | 64 (100) | |||

| 3 | 35 (85.4) | 47 (87.0) | 0.87 (0.27, 2.81) | 0.815 | 0.048† | |

| 12 | 26 (55.3) | 43 (78.2) | 0.35 (0.15, 0.82) | 0.016 | ||

| Felt unsafe past 30 days (composite safety variable) | BL | 33 (64.7) | 40 (63.5) | |||

| 3 | 14 (34.2) | 25 (45.5) | 0.53 (0.21, 1.33) | 0.176 | 0.003 | |

| 12 | 11 (23.4) | 29 (52.7) | 0.20 (0.08, 0.55) | 0.002 | ||

| Carried weapon (gun, knife, club), past 30 days | BL | 7 (13.0) | 13 (20.3) | |||

| 3 | 5 (11.9) | 17 (30.9) | 0.35 (0.11, 1.13) | 0.079 | 0.079 | |

| 12 | 5 (10.6) | 11 (20.0) | 0.57 (0.17, 1.88) | 0.358 | ||

| Physical fight past 12 months | BL | 27 (50.0) | 33 (51.6) | |||

| past 30 days | 3 | 9 (21.4) | 14 (25.5) | 0.88 (0.32, 2.38) | 0.800 | 0.075 |

| past 30 days | 12 | 6 (12.8) | 19 (34.6) | 0.26 (0.08, 0.81) | 0.020 | |

| Drove a car after using marijuana, past 30 days | BL | 8 (14.6) | 9 (14.8) | |||

| 3 | 6 (14.3) | 10 (18.5) | 0.82 (0.24, 2.76) | 0.745 | 0.383 | |

| 12 | 8 (17.0) | 13 (24.5) | 0.60 (0.21, 1.75) | 0.352 | ||

| Rode in a car with a person drunk/high after using marijuana, past 30 days | BL | 12 (21.8) | 11 (17.8) | |||

| 3 | 11 (26.2) | 13 (24.1) | 1.01 (0.39, 2.62) | 0.985 | 0.800 | |

| 12 | 10 (21.3) | 13 (23.6) | 0.81 (0.31, 2.10) | 0.668 | ||

| Tried to cutback marijuana use | ||||||

| … in the last 3 months | 3 | 29 (69.1) | 28 (50.9) | 2.15 (0.93, 4.99) | 0.074 | 0.029† |

| …since you enrolled | 12 | 34 (73.9) | 33 (60.0) | 0.19 (0.81, 4.42) | 0.143 | |

| Tried to stop using marijuana | ||||||

| … in the last 3 months | 3 | 23 (54.8) | 19 (34.6) | 2.29 (1.01, 5.23 | 0.048 | 0.020† |

| …since you enrolled | 12 | 25 (54.4) | 21 (38.2) | 1.93 (0.87, 4.27) | 0.106 | |

| Tried to be careful about situations you got into when using marijuana | ||||||

| … in the last 3 months | 3 | 32 (78.1) | 38 (69.1) | 1.59 (0.62, 4.05) | 0.331 | 0.357† |

| …since you enrolled | 12 | 34 (73.9) | 38 (70.4) | 1.19 (0.49, 2.88) | 0.694 | |

| High on marijuana in 30 days (among those who smoked 1+ days in past 30 per TLFB) | 55 (100) | 64 (100) | ||||

| 3 | 36 (87.8) | 46 (83.6) | 1.41 (0.43, 4.57) | 0.568 | 0.171† | |

| 12 | 25 (53.2) | 41 (74.6) | 0.39 (0.17, 0.89) | 0.026 | ||

Denotes: did not adjust for a baseline measure

A GEE analysis of those followed at three and at 12 months, controlling for baseline marijuana use, confirmed these results; at 12 months, those in the intervention group who smoked marijuana in the past 30 days reported fewer days high (OR 0.39, 95% CI 0.17, 0.89, p<0.027). There were no significant differences in risk behaviors.

Intentions to change behavior (see Table 7)

The intervention group was significantly more likely to report efforts to cut back or quit using marijuana, but groups were similar in reporting care taken with situations when using.

Referrals

The intervention group was more likely to report receiving a referral to community resources (OR: 3.36, 95% CI 1.09–10.40, p<.05). We were not able, in this small pilot study, to tie referrals to outcomes.

Assessment reactivity

There were no baseline differences in demographics between the NAC and AC groups or baseline differences in times per month of marijuana use. Preliminary analyses showed a difference in loss to follow-up between these two groups; loss to follow-up among light users (1 to 9 times per month) at baseline was 20% among the AC and 47% among the NAC group. We therefore controlled for baseline level of use (1–9 times vs. 10+ based on a screening question available for both groups) when comparing these two groups. There was no significant difference between groups in the average number of days of use at the 12 months follow-up visit (p=.095), with the NAC averaging 3.7 fewer days of use. These data suggest that the decline in use in the NAC group may be due to regression to the mean rather than to assessment reactivity.

Potential for PTSD to modify intervention results (see Table 8)

Table 8.

Effect of intervention on marijuana use, stratified by PTSD

| PCL-C Positive (n=40) | OR (95% CI) | PCL-C Negative (n=99) | OR(95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | AC | Intervention | AC | |||

| At 3 Months: | ||||||

| Abstinent | 0 | 2 | Cannot be computed | 6 | 5 | 1.8 (0.5, 6.7) |

| Not abstinent | 12 | 12 | 23 | 35 | ||

| At 12 Months: | ||||||

| Abstinent | 4 | 3 | 1.0 (0.2, 5.7) | 17 | 9 | 4.8 (1.7, 3.5) |

| Not abstinent | 13 | 10 | 13 | 33 | ||

Participants in this study were assessed for PTSD positivity primarily to assure comparability of groups at baseline. Because prevalence was high and similar between the two groups, we performed a sub-analysis to evaluate potential differences in intervention effectiveness among those who were positive on the PCL-C scale.

This very exploratory analysis suggests that 1) rates of abstinence are in general lower among those with PTSD, 2) intervention has less of an effect for patients with PTSD, and 3) the observed effect of intervention is largely due to the effect in the group without PTSD.

DISCUSSION

It is important to note that standard statistical models for multivariable analysis and longitudinal analysis of dichotomous outcome variables are based on the odds ratio, and differences in abstinence and other categorical outcomes were described through odds ratios. Some of our outcomes had moderately high prevalence, and so these odds ratios will be further from the null than the corresponding relative risks. For example, Table 3 reports an odds ratio and 95% CI of 2.89 (1.22, 6.84) for abstinence in the intervention vs. assessed control group. The corresponding relative risk and 95% CI is 2.05 (1.13, 3.70).

Reducing marijuana use at the critical developmental stage of adolescence may interrupt a trajectory that would otherwise lead to injury, illness, dependence, and other negative health and social effects associated with heavy marijuana consumption. This preliminary PED study suggests that a 20 minute motivational interviewing style of conversation with a peer educator at the time of a clinical visit to the ED could reduce marijuana consumption, increase abstinence and decrease days of use. We are encouraged by the worst case analysis presented in Table 4, which sustains an odds ratio greater than 2. In other studies in which we were able to investigate reasons for refusal to keep a follow-up appointment, many patients stated that they did not come in because their use was behind them, they had changed their lives, and they did not want to be associated with the label of user or past-user.18 We therefore think it is unlikely that all non-followed patients in this sample were still using, as we presumed for this worst-case analysis.

Although the intervention group in this preliminary study was more likely to be marijuana abstinent at 12 months or to report reduce marijuana consumption if they were not abstinent, we detected no impact of either abstinence or reduced consumption on consequences and risk behavior. An earlier ED study among adult cocaine and heroin users receiving a peer intervention also increased abstinence rates and reductions in drug use based on hair analysis, but did not measure risk behaviors or consequences.18 Among adolescents and young adults who were high risk drinkers, intervention at time of the ED visit shows mixed results, with reductions in alcohol consequences in one study (n=94)8 and in consumption in a second, larger study (n=198).10 The current investigation differed from these alcohol intervention studies in three ways: 1) it focused on marijuana, not alcohol; 2) the motivational intervention was delivered by slightly older peers, rather than by experienced Masters’ level counselors; and 3) it enrolled PED patients who presented for a range of medical conditions rather than only those who were admitted for intoxication or an alcohol-related injury.

In a community setting, researchers investigated the efficacy of a single session of motivational interviewing in reducing use of marijuana.11 Those using marijuana who received the intervention were approximately 3.5 times as likely to decide to stop or cut down on the use of marijuana compared to those who received the non-intervention “educational as usual” control condition, even after adjusting for baseline and other potential confounders. The mean frequency of marijuana use declined by 66% in the intervention group; by contrast, the control showed a 27% increase of marijuana use. Notably, the intervention showed the most significant impact on those youth considered high risk: males, frequent cigarette smokers, recipients of government benefits, and those who were rated more psychosocially vulnerable. While the findings of our study are somewhat less dramatic, they do demonstrate a significant intervention effect, especially since the PED intervention was limited to 20 minutes compared to one hour in the McCambridge study cited above.

We believe that the PED presents a difficult environment in which to effect behavior change because of the challenges of working around time restraints, the primacy of patient flow, clinical staff priorities, and variations in acuity. Despite these barriers, the peer educators integrated well into the ED setting and were able to deliver a consistent intervention with excellent adherence to protocol. In the population that uses an inner-city PED, marijuana use is a norm and a difficult topic to broach, yet peers in this study were able to engage on this issue and negotiate successfully with accompanying parents to leave the room during interviewing so that the adolescent’s privacy and confidentiality could be protected.

This preliminary study was not powered to capture relatively rare events or control for potential confounders. Follow-on studies are indicated to investigate impact on substance associated injury, identify the most effective context for screening questions (direct, drug-focused or embedded in a more comprehensive health survey), conduct sub-analyses to elaborate the role of predictors and moderators (demographics, mental health status, and operator differences), and determine which intervention components are most effective at what level of severity.

LIMITATIONS

This is a small pilot study. Although the sample size was adequate to show differences in marijuana consumption from baseline to 12-month follow-up, there was not sufficient power in this preliminary investigation to show differences in risk behaviors and consequences such as injuries that occur infrequently. Eligibility criteria for this study may also have been a factor, because low-end users were enrolled (3 or more days use per month or experience of consequences with fewer days of use). Randomization procedures stratified for severity of use may help to limit any ‘noise’ introduced by differences in severity.

The self-report measure used in this study (number of days of use on 30-day recall) did not attempt to quantify use (e.g. blunts, joints, tokes and time of day). Although formats such as Form-90 have been used for this purpose with adults, they have not been validated for accuracy in capturing dose, which can vary greatly with batch strength. Confirmation with a reliable chemical marker to quantify use over a 30-day window would have been helpful, and is certainly indicated for a follow-on study.

We also did not attempt to have participants recall use of the entire 12 months of the follow-up period, and may have missed efforts at abstinence that only lasted a few months but did not persist to the point of follow-up. We did obtain a 30 day snapshot at three months, but we did not believe that we could get accurate data retrospectively over a whole year’s time with this population. Since there are a number of studies that have demonstrated the accuracy of a 30 day follow back report with adolescents who are not in treatment, we selected that shorter window. However it is the 12 month endpoint, not specific intervals within the 12 months, that is of the most interest. SBIRT in all the studies previously discussed has only a modest effect size, so it is particularly important to assure that the effects, when they occur, have real clinical impact and duration.

Exploratory analyses suggest that PTSD may play a role in intervention effectiveness, but this was a pilot study with very few participants. A follow-on study with a sample size large enough to permit appropriate sub-analyses should include subjects with PTSD in order to examine this question more fully.

It should also be noted that the participants in this study did not report significant alcohol use or polydrug use at baseline, and therefore results may have limited applicability to other populations. In the diverse patient population seen in urban pediatric emergency departments, however, marijuana use commonly precedes alcohol use, and results may be particularly useful in those settings.

Finally, differential attrition in the important variable of severity of use at baseline occurred in the non-assessed group at follow-up. Because we had no information about the mental health characteristics, risk-taking attributes or injury history of those who we did not assess, we may also have had other important sources of differential attrition in the NAC group that we were unable to measure. We learned a valuable lesson: A no-assessment group still has to have high contact to avoid differential loss to follow-up.

CONCLUSION

A preliminary trial of SBI in the PED increased marijuana abstinence and reduced consumption among patients aged 14–21. These effects were strongest at 12 months, as reported by both 30 day recall and self-report of intention to change. However, there were no differences noted in risk behaviors or health consequences from baseline to final follow-up. This study demonstrated that a pediatric emergency department visit offers an opportunity to engage youth in a discussion of how drug use fits in with their lives and their goals.

We were not successful in measuring the impact of assessment on marijuana consumption and other behaviors after enrollment in a control group. A no-contact condition for the non-assessed group over the year after enrollment was insufficient to capture enrollees for follow-up across a range of baseline acuity.

Acknowledgments

Funded in part by a supplement from NIH/NIDA to The Youth Alcohol Prevention Center (P60AA13759.

The authors thank Michael Winter of the BUSPH Data Coordinating Center for assistance with data management and analysis. The successful completion of this study was made possible by the diligent efforts of two study coordinators, Anel Marchena-Suazo, MPH, and Melanie Rambaud, MPH, and a talented team of interventionists: Laura Cody, MPH, Stephanie Elliott-Moxley, MPH, John Murphy, Nilushka Nethisinghe, MPH, Michelle Sandoval, MPH, Stephanie Trilling, Delisa Vieira, Renel Vital, Georgina Waweru, Erin Wnorowski, MPH.

References

- 1.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. DAWN Series D-30, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 08-4339. Rockville, MD: 2008. Office of Applied Studies. Drug Abuse Warning network, 2006: National Estimates of Drug Related Emergency Department Visits. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerberich SG, Sidney S, Braun BL, Tekawa IS, Tolan KK, Queensberry CP. Marijuana use and injury events result in hospitalization. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:230–237. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(02)00411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kalant H. Adverse effects of cannabis on health: an update of the literature since 1996. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharm Beh Psychiatr. 2004;28:849–863. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gruber AJ, Pope HG, Hudson JL, Yurgelin-Todd D. Attributes of long term heavy cannabis users: a case control study. Psych Med. 2003;33:1415–1422. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kandel DB. Does marijuana use cause the use of other drugs? JAMA. 2003;289:482–483. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lynskey MT, et al. Escalation of drug use in early-onset cannabis users vs. co-twin controls. JAMA. 2003;289(4):427–433. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Patton GC, Coffey C, Lynskey MT, Hemphill S, Carlin JB, Hall W. Trajectories of adolescent alcohol and cannabis use into young adulthood. Addiction. 2007;102:607–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monti PM, Colby SM, Barnett NP, Spirito A, Rohsenow DJ, Myers M, et al. Brief intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J Consul Clin Psychol. 1999;67:989–94. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spirito A, Monti P, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Sindelar H, Rohsenow DJ, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol positive adolescents. J Pediatr. 2004;145:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monti P, Barnett NP, Colby SM, Gwaltney CJ, Sindelar H, Longabaugh R, Woolard R, Nirenberg T, Minugh P. A motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinkers. Addiction. 2007;102:1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McCambridge J, Strang J. The efficacy of single-session motivational interviewing in reducing drug consumption and perceptions of drug-related risk and harm among young people: Results from a multi-site cluster randomized trial. Addiction. 2002;99:39–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobell L, Sobell M. Time-line follow back: A technique for assessing self-reported alcohol consumption. In: Litten R, Allen J, editors. Measuring Alcohol Consumption. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levy S, Sherritt L, Harris SK, Gates EC, Holder DW, Kulig JW, Knight JR. Test-retest reliability of adolescents’ self-report of substance use. Alcohol Clin Exper Res. 2004;28:1236–1241. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000134216.22162.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jelalian E, Spirito A, Rasile D, Vinnick L, Rohrbeck C, Arrigan M. Risk taking, reported injury, and perception of future injury among adolescents. J Ped Psychol. 1997;22:513–31. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.4.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, et al. The Patient Health Questionnaire for Adolescents: Validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(3):196–204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broome KM, Joe GW, Simpson DD. Engagement models for adolescents in DATOS-A. J Adolesc Res. 2001;16:608–623. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Beh Res Ther. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, Heeren T, Levenson S, Hingson R. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alc Depend. 2005;77:49–59. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller WR. Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, DHHS Publication no. 99–3354. Rockville, MD: DHHS; 1999. Enhancing motivation for change in substance abuse treatment. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change addictive behavior. 2. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vanderbilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Ped Adolesc Med. 1999;153:591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall EA, Zuniga R, Cartier J, Anglin MD, Danila B, Ryan R, Mantius K. Staying in touch: a fieldwork manual of tracking procedures for locating substance abusers in follow-up studies. 2. Los Angeles CA: UCLA Integrated Substance Abuse Programs; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woolard RH, Carty K, Wirtz P, Longabaugh R, Nirenberg TD, Minough PA, Becker B, Clifford PR. Research fundamentals: Follow-up of subjects in clinical trials: Addressing subject attrition. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11:859–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2004.tb00769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]