Abstract

Hereditary hearing impairment (HI) is the most genetically heterogeneous trait known in humans. So far, 54 autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing impairment (ARNSHI) loci have been mapped, and 21 ARNSHI genes have been identified. Here is reported the mapping of a novel ARNSHI locus, DFNB55, to chromosome 4q12-q13.2 in a consanguineous Pakistani family. A maximum multipoint LOD score of 3.5 was obtained at marker D4S2638. The region of homozygosity and the 3-unit support interval are flanked by markers D4S2978 and D4S2367. The region spans 8.2 cM on the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map and contains 11.5 Mb. DFNB55 represents the third ARNSHI locus mapped to chromosome 4.

Keywords: 4q12-q13.2, autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing impairment, DFNB55, Pakistan

Hearing disorders produce significant health problems in the world population. The vast majority of genetic hearing impairment (HI) is designated as non-syndromic, which is further categorized by mode of inheritance: approximately 77% of cases are autosomal recessive; 22% are autosomal dominant; 1% are X-linked and <1% are due to mitochondrial inheritance (1). Autosomal recessive non-syndromic HI (ARNSHI) is usually clinically homogeneous, is non-progressive in nature and exhibits a high degree of genetic heterogeneity. To date, 54 loci have been mapped for ARNSHI and 21 genes have been identified (2). The majority of these genes were mapped and identified by studying large consanguineous families. Identification of genetic defects causing HI contributes to the understanding of the molecular basis that is important to hearing function. This article describes a new ARNSHI locus, DFNB55, which maps to 4q12-q13.2 and was localized in a consanguineous Pakistani family.

Materials and methods

Family history

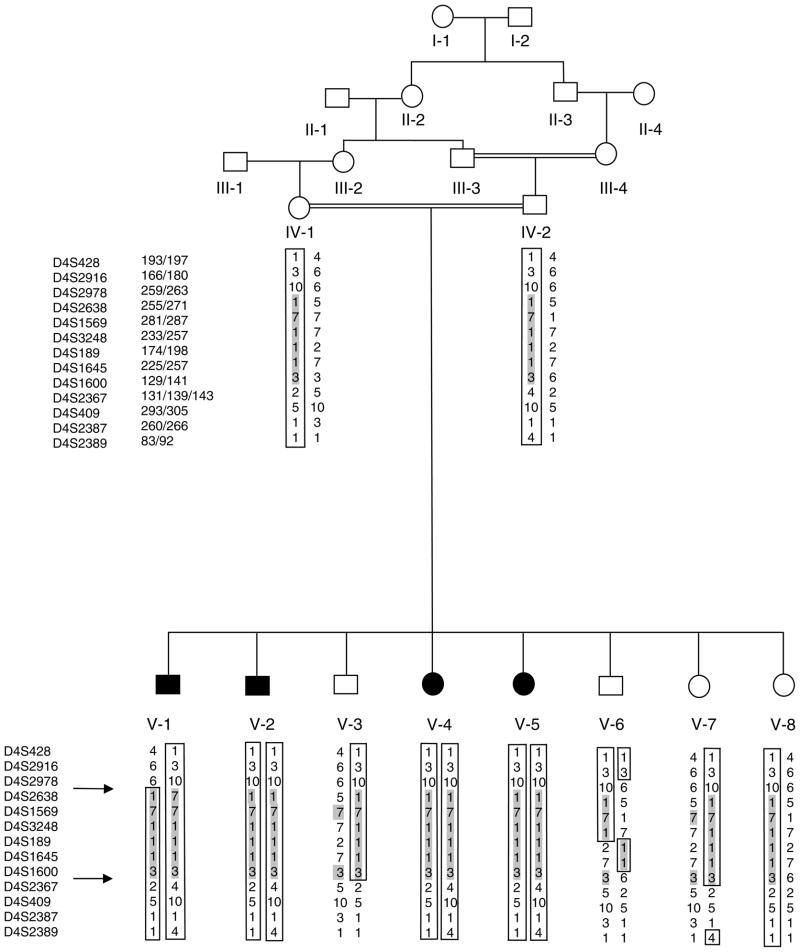

Before the start of the study, approval was obtained from the Quaid-i-Azam University and Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Boards. Signed informed consent was obtained from all family members who participated in the study. The pedigree structure is based upon interviews with multiple family members. Personal interviews with key figures in the kindred clarified the consanguineous relationships. For the analysis, correct specification of consanguineous relationships is extremely important, as misspecification of familial consanguineous relations will increase type I and II error. Family 4153 is from the Sind province of Pakistan. This consanguineous pedigree provides convincing evidence of autosomal recessive mode of inheritance (Fig. 1). Clinical findings in this family are consistent with the diagnosis of ARNSHI. Medical history and physical examination of the affected individuals were performed by trained otolaryngologists affiliated with government hospitals. All affected individuals have a history of prelingual profound HI involving all frequencies and use sign language for communication. The hearing-impaired family members underwent a clinical examination for mental retardation, defects in ear morphology, dysmorphic facial features, eye disorders including night blindness and tunnel vision, and other clinical features that could indicate that HI was syndromic. There was no evidence in this kindred that HI belonged to a syndrome or that there was gross vestibular involvement.

Fig. 1.

Pedigree drawing of family 4153. Black symbols represent individuals with hearing impairment. Clear symbols represent unaffected individuals. The sex of some of the family members was changed to protect the anonymity of the family. Allele sizes in kilobases are indicated beside the upper column of microsatellite markers. Alleles are numbered according to the CEPH Genotype database V10.0 (5). Haplotypes are shown below each individual for whom genotypes are available. For individuals in generation V, maternal haplotypes are displayed on the left-hand side and paternal haplotypes on the right-hand side. Arrows and shaded areas indicate the region of homozygosity.

Extraction of genomic DNA and genotyping

Venous blood samples were obtained from seven family members including four individuals who are hearing-impaired. Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood following a standard protocol (3). As the GJB2 gene is the most frequent cause of ARNSHI, all non-syndromic HI families are screened for mutations in this gene before undergoing a genome scan. Those families, which are positive for functional GJB2 variants, are excluded from the genome scan. In family 4153, the GJB2 gene was sequenced in two hearing-impaired family members, V-5. and V-6. (4), and no functional variants or benign polymorphisms were observed. A genome scan was carried out on seven DNA samples at the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) Mammalian Genotyping Service (Center for Medical Genetics, Marshfield, WI). A total of 410 short tandem repeat polymorphism markers with an average heterozygosity of 0.75 were genotyped. These markers are spaced approximately 10 cM apart and are located on the 22 autosomes and the X and Y chromosomes. After the completion of the genome scan, three additional unaffected (V-6., V-7. and V-8.) family members were ascertained and their DNA samples were used for fine mapping of the DFNB55 locus.

For fine mapping, polymerase chain reactions (PCR) for microsatellite markers were performed according to standard procedure in a total volume of 25 μl with 40 ηg of genomic DNA, 0.3 μl of each primer, 200 μM of dNTP and 1 × PCR buffer (Fermentas Life Sciences, Burlington, ON, Canada). PCR was carried out for 35 cycles: 95 °C for 1 min, 57 °C for 1 min and 72 °C for 1 min in a thermal cycler (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA). PCR products were resolved on 8% non-denaturing polyacrylamide gel and genotypes were assigned by visual inspection. Alleles were numbered according to the CEPH Genotype database V10.0 (5).

Linkage analysis

The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Build 34 sequence-based physical map was used to determine the order of the genome scan markers and fine mapping markers (6). Several of the genome scan markers were not found on the NCBI sequence-based physical map and were placed on the sequence-based physical map using e-PCR (7). Genetic map distances according to the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map of the human genome were used to carry out the multipoint linkage analysis for the fine map and genome scan markers (8). For those genome scan markers for which no genetic map position was available, interpolation was used to place these markers on the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map. PEDCHECK (9) was used to identify Mendelian inconsistencies, while the MERLIN (10) program was used to detect potential genotyping errors that did not produce a Mendelian inconsistency. Haplotypes were constructed using SIMWALK2 (11, 12). Two-point linkage analysis was carried out using the MLINK program of the FASTLINK computer package for the genome scan and fine mapping marker loci (13). Multipoint linkage analysis was performed using ALLEGRO (14). An autosomal recessive mode of inheritance with complete penetrance and a disease allele frequency of 0.001 were used. For the genome scan, marker allele frequencies were estimated from the founders and reconstructed genotypes of founders from this family and 34 additional families from Pakistan that underwent a genome scan at the same time at the NHLBI Mammalian Genotyping Service. For the fine mapping markers, it was not possible to estimate allele frequencies from the founders because these markers were genotyped only in this family. False-positive results can be obtained when analysing the data using too low of an allele frequency for the allele segregating with the disease locus (15). Therefore, a sensitivity analysis was carried out for the multipoint linkage analysis by varying the allele frequency of the marker alleles that are segregating with the disease locus from 0.2 to 0.8 for the fine mapping markers. This was performed in order to determine whether the multipoint LOD scores are robust to allele frequency misspecification.

Results

From the genome scan data, a maximum two-point LOD score of 1.8 (θ = 0) was obtained at marker D4S3248 and a maximum multipoint LOD score of 2.6 was obtained at marker D4S3248. In order to establish linkage and fine-map the DFNB55 locus on chromosome 4, fifteen additional polymorphic microsatellite markers were selected from the Marshfield genetic map (16). Eight markers are proximal to D4S3248 (D4S2632, D4S1627, D4S2996, D4S428, D4S2916, D4S2978, D4S2638 and D4S1569) and seven of the markers distal to D4S3248 (D4S189, D4S1645, D4S1600, D4S409, D4S2387, D4S2389 and D4S1517). These markers and the genome scan markers in the region were genotyped in the seven family members who were originally included in the genome scan and in three additional family members that were ascertained after completion of the genome scan. Analysis of the marker genotypes within this region with PEDCHECK and MERLIN did not elucidate any genotyping errors. For the genotype data on the additional marker loci and family members, a maximum two-point LOD score of 2.8 (θ = 0) was obtained with marker D4S1645 (Table 1). A maximum multipoint LOD score of 3.5 was obtained at marker D4S2638. The 3-unit multipoint support interval is an 8.2-cM region according to the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map of the human genome and spans from marker D4S2978 to marker D4S2367 (8). Haplotypes were then constructed to determine the critical recombination events (Fig. 1). The region of homozygosity in HI individuals was also flanked by markers D4S2978 and D4S2367. This region corresponds to a physical map distance of 11.5 Mb (6).

Table 1.

Two-point LOD score results between the DFNB55 locus and chromosome 4 markers

| Markera | Genetic map positionb | Physical map positionc | LOD score at = |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.0 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | |||

| D4S428 | 71.42 | 55,549,948 | −∞ | −1.12 | −0.58 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.26 |

| D4S2916 | 72.35 | 55,728,673 | −∞ | −1.12 | −0.58 | −0.09 | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.26 |

| D4S2978 | 73.97 | 56,831,962 | −∞ | 0.57 | 0.82 | 1.00 | 1.04 | 1.04 | 0.77 | 0.42 |

| D4S2638 | 75.85 | 58,503,365 | 2.63 | 2.57 | 2.51 | 2.38 | 2.32 | 2.00 | 1.37 | 0.76 |

| D4S1569 | 76.81 | 59,564,470 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.37 |

| D4S3248 | 76.81 | 60,024,835 | 2.63 | 2.57 | 2.51 | 2.38 | 2.32 | 2.00 | 1.37 | 0.76 |

| D4S189 | 77.32 | 60,668,220 | 2.63 | 2.57 | 2.51 | 2.38 | 2.32 | 2.00 | 1.37 | 0.76 |

| D4S1645 | 77.37 | 61,986,341 | 2.75 | 2.68 | 2.62 | 2.48 | 2.42 | 2.08 | 1.43 | 0.79 |

| D4S1600 | 78.57 | 62,900,873 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.08 | 1.03 | 1.00 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.37 |

| D4S2367 | 82.19 | 68,286,182 | 0.19 | 1.04 | 1.27 | 1.46 | 1.50 | 1.54 | 1.27 | 0.82 |

| D4S409 | 82.19 | 68,327,249 | −1.65 | −0.79 | −0.54 | −0.30 | −0.24 | −0.07 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| D4S2387 | 82.60 | 69,105,934 | 1.37 | 1.35 | 1.32 | 1.27 | 1.24 | 1.10 | 0.82 | 0.52 |

| D4S2389 | 85.86 | 73,110,824 | −0.93 | −0.18 | 0.06 | 0.28 | 0.34 | 0.49 | 0.46 | 0.29 |

Markers displayed in italics flank the haplotype. Genome scan markers are shown in bold type.

Cumulative sex-averaged Kosambi cM genetic map distances from the Rutgers combined linkage-physical map of the human genome (8).

Sequence-based physical map distance in bases according to Build 34 of the human reference sequence (6).

When the marker allele frequencies for the alleles segregating with HI were varied for the fine mapping markers from 0.2 to 0.4, the maximum multi-point LOD score remained to be 3.5 at marker D4S2638. When the allele frequencies were varied between 0.6 and 0.8, the maximum LOD score occurred at marker D4S2638 but decreased to 3.4.

Discussion

In this study, a novel ARNSHI locus, DFNB55, was mapped to an 8.2-cM interval on chromosome 4q12-q13.2. Seven non-syndromic hearing impairment (NSHI) loci, DFNA6 [4p16.3] (17), DFNA14 [4p16] (17), DFNA24 [4q35] (18), DFNA27 [4q12] (19), DFNA39 [4q21.3] (20), DFNB25 [4p15.3-q12] (21) and DFNB26 [4q31] (22), have been previously mapped to chromosome 4. For these seven loci, two genes, WFS1 for DNA6/DFNA14 (17) and DSPP for DFNA39 (20), have been identified.

The genetic region for DFNB55 overlaps with the autosomal dominant NSHI locus DFNA27 (19). The DFNA27 locus maps between markers D4S428 (71.42 cM) and D4S392 (83.58 cM) and thus the genetic interval for DFNB55 is within the genetic interval for DFNA27. Although two genes in close proximity might cause DFNB55 and DFNA27, it is also possible that NSHI in DFNB55 and DFNA27 families is caused by different mutations in the same gene. It has been observed that different mutations in the same gene can cause both autosomal dominant and recessive NSHI (e.g. GJB2, MYO7A, TECTA and TMC1) (2). It should also be noted that the DFNB55 locus does not overlap with the DFNB25 locus (Richard Smith, personal communication).

The DFNB55 interval contains 14 known genes and a large number of hypothetical genes and expressed sequenced tags. Several of the known genes in this region are expressed in the inner ear (23, 24), namely ephrin receptor EPHA5 [MIM 600004], PPAT [MIM 172450], POLR2B [MIM 180661] and IGFBP7 [MIM 602867]. In particular, EPHA5, a member of a family of ligands that are implicated in the development and spatial patterning of cortical pathways to target organs such as the retina and the olfactory bulb (25, 26), has been immunolocalized to the apical and basal portions of supporting cells which flank utricular hair cells in the rat (27). Likewise, EPHA5 was detected in lateral wall fibrocytes and interdental cells in the spiral limbus of postnatal and adult gerbil cochlea (28). All exons of EPHA5 were sequenced in one hearing and two hearing-impaired members of family 4153 and were found to be negative for functional sequence variants.

An additional strong candidate gene found within the DFNB55 region is RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST) [MIM 600571], which is a transcriptional repressor of neural genes in non-neural cells (29). The REST gene was found to be expressed in supporting cells but not in hair cells of chick auditory epithelium (30). Additionally, REST mRNA is upregulated in both supporting cells and hair cells following gentamicin damage to the inner ear. The coding regions of the REST gene were sequenced in one unaffected and two hearing-impaired family members and no functional variant was identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family members for their invaluable participation and cooperation. This work was supported by the NHLBI Mammalian Genotyping Service, the Higher Education Commission, Islamabad, Pakistan, and the National Institutes of Health – National Institute of Deafness and other Communication Disorders grant R01-DC03594.

References

- 1.Morton NE. Genetic epidemiology of hearing impairment. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1991;630:16–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1991.tb19572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Camp G, Smith RJH. [Accessed March 2005];Hereditary Hearing Loss Homepage. from http://webhost.ua.ac.be/hhh/

- 3.Grimberg J, Nawoschik S, Bellusico L, McKee R, Turck A, Eisenberg A. A simple and efficient non-organic procedure for the isolation of genomic DNA from blood. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:83–90. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.20.8390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos RLP, Wajid M, Pham TL, et al. Low prevalence of Connexin 26 (GJB2) variants in Pakistani families with autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing impairment. Clin Genet. 2005;67:61–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00379.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray JC, Buetow KH, Weber JL, et al. A comprehensive human linkage map with centimorgan density. Cooperative Human Linkage Center (CHLC) [Accessed April 2005];Science. 1994 265:2049–2054. doi: 10.1126/science.8091227. CEPH Genotype database V10.0 – November 2004. from http://www.cephb.fr/cephdb/ [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.International Human Genome Sequence Consortium. Initial sequence and analysis of the human genome. [Accessed March 2005];Nature. 2001 409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. July 2003 reference sequence as viewed in: Genome Bioinformatics Group of UC Santa Cruz. UCSC Genome Browser. from http://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgGateway. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Schuler GD. Sequence mapping by electronic PCR. Genome Res. 1997;7:541–550. doi: 10.1101/gr.7.5.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kong X, Murphy K, Raj T, He C, White PS, Matise TC. A combined linkage-physical map of the human genome. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:1143–1148. doi: 10.1086/426405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Connell JR, Weeks DE. PedCheck: a program for identification of genotype incompatibilities in linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:259–266. doi: 10.1086/301904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abecasis GR, Cherny SS, Cookson WO, Cardon LR. Merlin – rapid analysis of dense genetic maps using sparse gene flow trees. Nat Genet. 2002;30:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weeks DE, Sobel E, O’Connell JR, Lange K. Computer programs for multilocus haplotyping of general pedigrees. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56:1506–1507. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sobel E, Lange K. Descent graphs in pedigree analysis: applications to haplotyping, location scores, and marker-sharing statistics. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:1323–1337. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cottingham R, Indury RM, Schaffer AA. Faster sequential genetic linkage computations. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;53:252–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gudbjartsson DF, Jonasson K, Frigge ML, Kong A. Allegro, a new computer program for multipoint linkage analysis. Nat Genet. 2002;25:12–13. doi: 10.1038/75514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freimer NB, Sandkuijl LA, Blower S. Incorrect specification of marker allele frequencies: effects on linkage analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:1102–1110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Broman KW, Murray JC, Sheffield VC, White RL, Weber JL. Comprehensive human genetic maps: individual and sex-specific variation in recombination. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:861–869. doi: 10.1086/302011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bespalova IN, Van Camp G, Bom SJ, et al. Mutations in the Wolfram syndrome 1 gene (WFS1) are a common cause of low frequency sensorineural hearing loss. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2501–2508. doi: 10.1093/hmg/10.22.2501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hafner FM, Salam AA, Linder TE, et al. A novel locus (DFNA24) for prelingual nonprogressive autosomal dominant nonsyndromic hearing loss maps to 4q35-qter in a large Swiss German kindred. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:1437–1442. doi: 10.1086/302865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridell RA, Boger EA, San Agustin T, Brownstein MJ, Friedman TB, Morell RJ. DFNA27, a new locus for autosomal dominant hearing impairment on chromosome, 4. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.00966.x. Program Nr, 1388. Accessed from http://genetics.faseb.org/genetics/ashg99/f1388.htm. (Abstract) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Xiao S, Yu C, Chou X, et al. Dentinogenesis imperfecta 1 with or without progressive hearing loss is associated with distinct mutations in DSPP. Nat Genet. 2001;27:129–130. doi: 10.1038/84848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odeh H, Hagiwara N, Skynner M, et al. Characterization of two transgene insertional mutations at pirouette, a mouse deafness locus. Audiol Neurootol. 2004;9:303–314. doi: 10.1159/000080701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riazuddin S, Castelein CM, Ahmed ZM, et al. Dominant modifier DFNM1 suppresses recessive deafness DFNB26. Nat Genet. 2000;26:431–434. doi: 10.1038/82558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Hearing Research Group at Brigham & Women’s Hospital. [Accessed March 2005];Human Cochlear cDNA library and EST database. from http://hearing.bwh.harvard.edu/estinfo.htm.

- 24.Holme RH, Bussoli TJ, Steel KP. [Accessed March 2005];Table of gene expression in the developing ear. from http://www.ihr.mrc.ac.uk/Hereditary/genetable/index.shtml.

- 25.Feldheim DA, Nakamoto M, Osterfield M, et al. Loss-of-function analysis of EphA receptors in retinotectal mapping. J Neurosci. 2004;24:2542–2550. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0239-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.St John JA, Pasquale EB, Key B. EphA receptors and ephrin-A ligands exhibit highly regulated spatial and temporal expression patterns in the developing olfactory system. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;138:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00454-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matsunaga T, Greene MI, Davis JG. Distinct expression patterns of Eph receptors and ephrins relate to the structural organization of the adult rat peripheral vestibular system. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:1599–1616. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bianchi LM, Liu H. Comparison of ephrin-A ligand and EphA receptor distribution in the developing inner ear. Anat Rec. 1999;254:127–134. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0185(19990101)254:1<127::AID-AR16>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schoenherr CJ, Anderson DJ. The neuron-restrictive silencer factor (NRSF): a coordinate repressor of multiple neuron-specific genes. Science. 1995;267:1360–1363. doi: 10.1126/science.7871435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberson DW, Alosi JA, Mercola M, Comanche DA. REST mRNA expression in normal and regenerating avian auditory epithelium. Hear Res. 2002;172:62–72. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00512-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]