Abstract

Purpose of review

We discuss the latest findings on the biochemistry of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT), the effect of LCAT on atherosclerosis, clinical features of LCAT deficiency, and the impact of LCAT on cardiovascular disease from human studies.

Recent findings

Although there has been much recent progress in the biochemistry of LCAT and its effect on HDL metabolism, its role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis is still not fully understood. Studies from various animal models have revealed a complex interaction between LCAT and atherosclerosis that may be modified by diet and by other proteins that modify lipoproteins. Furthermore, the ability of LCAT to lower apoB appears to be the best way to predict its effect on atherosclerosis in animal models. Recent studies on patients with LCAT deficiency have shown a modest but significant increase incidence of cardiovascular disease consistent with a beneficial effect of LCAT on atherosclerosis. The role of LCAT in the general population, however, have not revealed a consistent association with cardiovascular disease.

Summary

Recent research findings from animal and humans studies have revealed a potential beneficial role of LCAT in reducing atherosclerosis but additional studies are necessary to better establish the linkage between LCAT and cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: LCAT, HDL, reverse cholesterol transport, atherosclerosis, cholesterol, cardiovascular disease

Introduction

Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) (EC2.3.1.43), first described in 1962 by Glomset[1], is a key enzyme for the production of cholesteryl esters in plasma and promotes the formation of high density lipoprotien (HDL). Shortly after its discovery, LCAT was proposed by Glomset[2] to promote the Reverse Cholesterol Transport (RCT), the anti-atherogenic mechanism by which excess cholesterol is removed from cells by HDL and delivered to the liver for excretion[3, 4]. Although the role of LCAT in cholesterol efflux from cells has largely been substantiated, its overall role in the pathogenesis of coronary heart disease (CHD) is still not completely understood, because it appears to depend upon other genes and environmental factors. In this review, we will first briefly discuss the biochemistry of LCAT and its role in HDL metabolism. Next, we will review the effect of increasing or decreasing the expression of LCAT on lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis in various animal models. Finally, clinical features of LCAT deficiency and evidence from recent human studies on the effect of LCAT on CHD will be discussed.

LCAT Biochemistry

The human lcat gene, localized at 16q22, is 4.5 kb in length and contains 6 exons, which contain 1.5 kb of coding sequence[5]. It is primarily expressed in the liver but is also produced in smaller amounts in the brain and testes[6–12]. LCAT gene expression is relatively insensitive to most drugs, diet modifications or other lifestyle factors; however, fibrates lower plasma LCAT activity by approximately 20%[13, 14], whereas torcetrapib and atorvastatin can modestly increase LCAT levels HDL[15–17]. The mature protein contains 416 amino acids and the primary amino acid sequence of LCAT is relatively well conserved[5–8, 18]. There is limited information on the tertiary structure of LCAT, but a stucutural model for LCAT based on its homology with the α/β hydrolase fold family proteins, such as the lipases, has been described[19]. The model nicely predicts the conformation of the known catalytic triad of the enzyme, which is formed by Ser181, Asp345, and His377 residues. Two disulfide bridges have been described in LCAT[20]. Residues 53 to 71, which contains the disulfide-linked Cys50-Cys74 residues, forms part of the lid-region and a lipid binding surface[21–23], which partially covers the active site of the enzyme[24]. LCAT also contains two free cysteines (Cys31, Cys184), which account for the sensitivity of the enzyme to inhibition by sulfhydryl reactive agents[25]. The mature fully processed protein is approximately 63 kDa, which is more than 20% greater than the predicted protein mass. Most of this extra mass is due to the presence of N-linked glycosylation[26, 27], which are important for its biological activity [28–31].

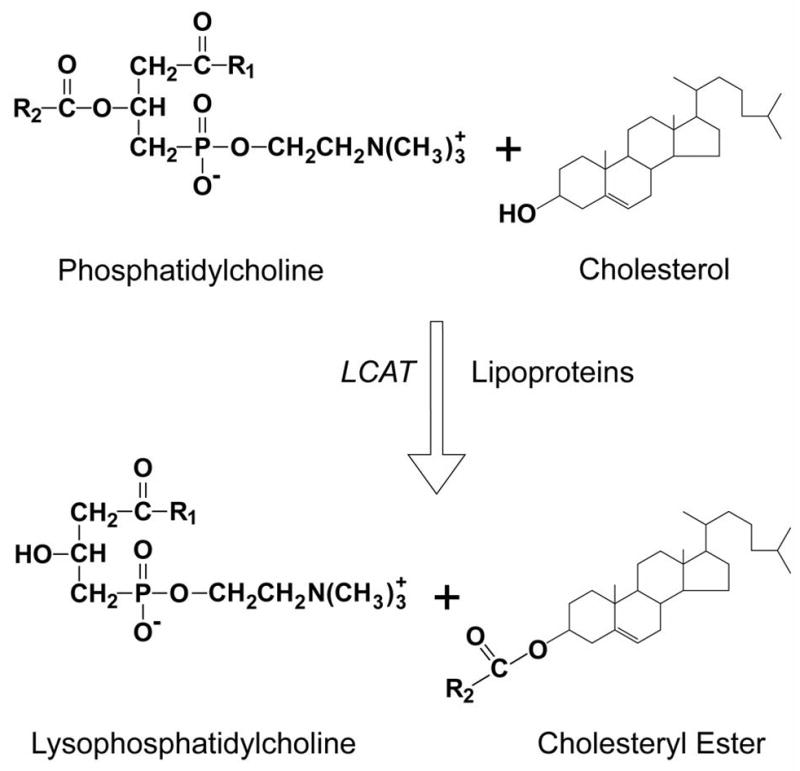

The LCAT reaction occurs in two steps (Fig. 1). After binding to a lipoprotein, LCAT cleaves the fatty acid in sn-2 position of phosphatidylcholine and transfers it onto Ser181. Next, the fatty acid is transesterified to the 3-β-hydroxyl group on the A-ring of cholesterol to form cholesteryl ester. Because cholesteryl esters are more hydrophobic than free cholesterol, it migrates into the hydrophobic core of lipoprotein particles. Approximately 75% of plasma LCAT activity is associated with HDL, but LCAT is also able to bind and produce cholesteryl esters on LDL and other apoB-containing lipoproteins[32, 33]. Human LCAT preferentially acts on phospholipids containing 18:1 or 18:2 fatty acids, whereas rat and mouse LCAT prefer phospholipids containing 20:4 fatty acids[34, 35]. Other phospholipids, such as phosphatidylethanolamine, can also participate in the LCAT reaction[36], whereas other lipids, such as sphingomyelin, can inhibit LCAT [37–40].

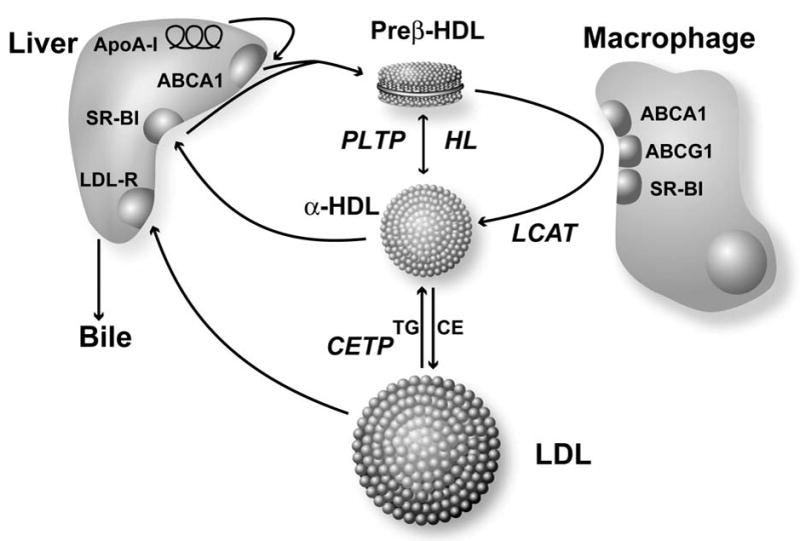

Figure 1. Diagram of the Reverse Cholesterol Transport Pathway.

Pre-beta HDL produced, as a consequence of the interaction of apoA-I with the ABCA1 transporter on the liver, obtains additional phospholipid and cholesterol from ABCA1 transporters on peripheral cells, such as macrophages. In addition, HDL can acquire more lipid by other mechanisms, such as from the ABCG1 transporter, the SR-BI receptor or by an aqueous diffusion process. Cholesterol removed from cells by HDL is converted to cholesteryl esters by LCAT, which transforms pre-beta HDL to alpha-HDL. Cholesterol can be directly returned to the liver after uptake by the SR-BI receptor or after transfer to apoB-containing lipoproteins by CETP. Phospholipid transfer protein (PLTP) and hepatic lipase (HL) promote the interconversion alpha-HDL and pre-beta HDL.

In vitro, many different apolipoproteins can activate LCAT[41, 42], but compared to apoA-I, they appear to be less effective and are not as abundant as apoA-I in plasma., They may still, however, play a physiologic role, particularly apoE, in activating LCAT on apoB-containing lipoproteins [43]. The exact mechanism by which apoA-I activates LCAT is not known[44–47], but one proposal is that it stabilizes an active conformation of LCAT, similar to the way colipase activates pancreatic lipase[48, 49]. In several recent HDL structural studies, the regions of apoA-I that activate LCAT appear to be more surface exposed compared to most other parts of apoA-I[44, 50, 51].

LCAT in HDL metabolism

Figure 2 shows where LCAT fits into the RCT pathway[3]. This pathway promotes the removal of excess cellular cholesterol from peripheral tissues and its delivery to the liver[52, 53] for excretion into the bile. It begins with the formation of HDL largely in the liver[54–56] and the transfer of phospholipid and cholesterol by various transporters[57–60] to HDL and its eventual uptake into the liver. According to this model, LCAT plays two important roles. First, as originally proposed by Glomset[3], LCAT has been shown to promote the efflux of cholesterol from peripheral cells[61]. The esterification of cholesterol on HDL increases the concentration gradient for free cholesterol between cell membranes and HDL. Without the ongoing esterification of cholesterol, the capacity of HDL to remove and bind additional cholesterol would eventually be diminished over time. CETP may further enhance this process by transferring cholesteryl esters formed by LCAT from HDL onto LDL[62, 63], creating additional capacity for HDL to bind cholesterol. The esterification of cholesterol also transforms the discoidal shaped nascent HDL with a pre-beta migration position on agarose gels into spherical shaped HDL, which is called alpha-HDL. Because cholesteryl esters are much more hydrophobic than cholesterol, the other consequence of LCAT is that it prevents the spontaneous back exchange of cholesterol from HDL to cells and thus promotes the net cellular removal of cholesterol [61]. Cholesteryl esters on HDL and LDL are essentially trapped on these lipoproteins until they can be removed from the circulation by the liver.

Figure 2. Diagram of the LCAT Reaction.

LCAT cleaves the fatty acid (R2) from the sn-2 position of phosphatidylcholine and then transesterifies it to the A-ring of cholesterol, producing lysophosphatidylcholine and cholesteryl ester.

Analysis of LCAT in animal models

An important experimental system for testing the role of LCAT in the RCT pathway and its effect on atherosclerosis has been the development of various animal models with either increased or decreased expression of LCAT (Table 1).

Table 1.

Animal models of overexpression or deficit of LCAT.

| Species | Model | Construct | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mice | Transgenic | Genomic hLCAT with its own promoter and 3′-flank | 10 |

| Mice | Transgenic | Genomic hLCAT with albumin enhancer and promoter | 85 |

| Mice | Transgenic | Genomic hLCAT with its own promoter and 3′-flank | 82 |

| Rabbits | Transgenic | hLCAT with its own promoter and 3′-flank region | 11 |

| Squirrel monkey | Viral infection | hLCAT in adenovirus | 88 |

| Mice | Knockout | Homologous recombination replacement vector | 92 |

| Mice | Knockout | Homologous recombination replacement vector | 93 |

One of the first LCAT transgenic mice produced had a relatively high level of expression, (10–200 fold), which was associated with an increase in total cholesterol, LDL-C and HDL-C[9, 69]. Mice with the highest level of LCAT were found to produce heterogeneous size HDL, which contained a mixture of apoA-I and apoA-II, as well as apoE, particularly on the larger HDL particles that were enriched in cholesteryl esters. ApoE-rich HDL in these mice was found to be dysfunctional, at least in regard to the delivery of cholesterol to the liver[69, 70]. LCAT has also been overexpressed in transgenic rabbits[11], which unlike mice express CETP. As observed in mice, overexpression of LCAT in rabbits also increased HDL-C but unlike mice it decreased LDL-C[71]. Transient expression of hLCAT in squirrel monkeys with adenovirus also raised HDL-C and decreased apoB-lipoproteins, due to increased catabolism[66].

LCAT transgenic rabbits had 50–60% lower levels of pro-atherogenic apo B lipoprotiens[71] and were protected against diet-induced atherosclerosis[10]. LCAT transgenic rabbits crossed with LDL-receptor deficient rabbits showed that the LDL-receptor is necessary for the ability of LCAT to lower apoB-lipoproteins and for reducing atherosclerosis[72]. In contrast, LCAT overexpression in mice did not protect against diet-induced atherosclerosis[70, 73, 74], and in fact, in some cases, increased atherosclerosis mice with very high levels of LCAT [70]. Crossbreeding of LCAT and CETP transgenic mice led, however, to an approximate 50% reduction of diet-induced atherosclerosis compared to LCAT transgenic mice, although it was still increased above control mice[69]. The HDL produce by these mice in the presence of CETP was found to be more functional. In addition, these mice had lower levels of apoB containing lipoproteins[69].

Studies of LCAT-knockout (K/O) mice have also advanced our knowledge of the effect of LCAT on HDL metabolism. LCAT-K/O mice have markedly reduced plasma total cholesterol, cholesteryl esters, HDL-C, apoA-I, and an increase in plasma triglycerides[67, 68]. The amount of alpha-HDL was strikingly decreased and the residual HDL was mostly pre-beta type HDL. When LCAT-K/O mice were placed on high cholesterol/cholate diet, it induced the formation of LpX-like lipoprotein particles, which can also be produced in cholestatic liver disease. Unlike normal lipoproteins, which have a micellar-like structure with a single monolayer of phospholipids and neutral lipid core, these abnormal particles, are multilamellar phospholipid vesicles that contain a minimum amount of neutral lipids but can contain common plasma proteins like albumin entrapped within the particle. Similar to LCAT-deficient patients, LCAT-K/O mice on a high fat diet developed proteinuria and glomerulosclerosis, characterized by mesangial cell proliferation, sclerosis, and lipid accumulation, which may be the consequence of the renal deposition of LpX [75]. Another mouse model of LCAT deficiency that spontaneously developed glomerulopathy on a normal chow diet was created by crossing LCAT-K/O mice with SREPB1a transgenic mice[76], which have increase production of apoB containing lipoproteins. These mice also had lower levels of paraoxonase and platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolases[77], two anti-oxidant enzymes that normally reside on HDL.

Unexpectedly, LCAT deficiency in mice significantly reduced diet-induced atherosclerosis when on a high cholesterol/cholate diet, despite causing a marked decrease of HDL-C[75]. This protection was also observed for LCAT deficiency when present in LDL-receptor-K/O and CETP-transgenic mice placed on high-cholesterol/cholate diet, as well as in apoE-K/O knockout mice on normal chow diet[75]. In all these cases, LCAT deficiency was associated with a significant decrease of apoB-containing lipoproteins. In another study, LCAT-K/O × apoE-K/O mice placed on a high fat diet but without cholate showed instead an increase of atherosclerosis[78]. On this diet, apoB levels increased and cholesteyl esters were enriched in pro-atherogenic saturated fatty acids. In contrast, LCAT-K/O × apoE-K/O mice on a normal chow diet had lower apoB levels and developed less atherosclerosis compared to just apoE-K/O mice[79]. Interestingly, these mice have higher paraoxonase 1 activity and decreased markers of oxidative damage compared to just apoE-K/O mice, presumably because in the absence of LCAT, paraoxonase 1, can relocate from HDL to the abnormal apoB-containing lipoproteins that accumulate with LCAT deficiency. Overall the results from the various animal models, indicate that there is a complex interaction between LCAT and atherosclerosis, which depends on the diet and can be modulated by the other proteins in the RCT pathway, such as CETP and the LDL-receptor. It appears, however, that the anti-atherogenic effect of LCAT more closely correlates with its ability to lower plasma levels of apoB-lipoproteins than on its ability to raise HDL-C.

Human Genetic Disorders of LCAT

Over 60 different mutations in the LCAT gene have been described[80–82], which can lead to two rare autosomal recessive disorders, namely Familial LCAT Deficiency[83, 84] (FLD) or Fish-Eye Disease[85] (FED). Both conditions are characterized by low HDL-C and corneal opacities, but FLD subjects have a more severe deficiency of LCAT and can develop other signs and symptoms (Table 2).

Table 2.

Clinical Findings in Patients with FLD and FED

| Clinical Features | FLD | FED |

|---|---|---|

| Corneal opacities | + | + |

| Anemia | + | − |

| Target cells in blood | + | − |

| Proteinuria | + | − |

| Renal Failure | + | − |

| Atherosclerosis | −/+ | −/+ |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | + | −/+ |

| Lympnadenopathy | + | −/+ |

FED subjects were first described to have reduced LCAT activity on HDL (alpha-LCAT) but near normal activity on LDL (beta-LCAT), whereas LCAT is nearly absent on both lipoproteins in FLD[86]. Some LCAT mutations have been shown to selectively affect LCAT activity on HDL[87], but not all mutations can be neatly categorized as affecting only the esterification of cholesterol on HDL or LDL, suggesting that some patients with FED may differ from FLD by having more residual LCAT activity on both HDL and LDL[88, 89].

FED and FLD subjects can have normal to elevated total cholesterol and triglycerides, and they both present with a similar low level of HDL-C (Table 3).

Table 3.

Plasma Lipids and Lipoprotein Profile in Patients with FED

| FED (range) | Reference Range | |

|---|---|---|

| TC (mg/dL) | 186 (64–253) | 120–280 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 146 (60–408) | 40–250 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 9 (0–27) | 30–85 |

| Apo A-I (mg/dL) | 42 (29–45) | 90–190 |

| CE/TC | 0.46 (0.57–0.65) | 0.67–0.71 |

| CER (nmoL/mL/h) | 51 (25–74) | 40–80 |

| LCAT mass (μg/mL) | 3.5 (0–4) | 3.8–6.6 |

TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; CE/TC: cholesteryl ester/total cholesterol ratio; LCAT: lecithin:cholesteryl acyltransferase; CER: cholesteryl esterification rate. Data from approximately 15 FLD subjects are shown as mean with range in parenthesis. Modified from re,f 95 with additional data from ref. 105 and 127.

Although also low in FED subjects, FLD subjects have a much lower ratio of CE/TC because of their greater reduction in LCAT activity. This is consistent with the much lower cholesterol esterification ratio (CER) typically found in FLD compared to FED[86]. The CER assay, which is a measure of LCAT activity based on endogenous lipoproteins, is performed by adding radiolabeled cholesterol to plasma and then determining the rate of cholesteryl ester formation. LCAT mass can be highly variable, because some mutations will primarily affect enzyme activity but not mass.

Many of the clinical features of these two diseases can be partially explained by the underlying defect in LCAT. As with other disorders of the RCT pathway, such as Tangier disease and apoA-I deficiency[94], cholesterol can accumulate in the cornea of these patients[80, 91], most likely as a consequence of decreased cholesterol efflux. A physical examination of the eyes of these subjects will typically reveal a pale cloudy cornea, with a whitish ring around the periphery that is similar to arcus senilis. Typically the corneal deposits do not significantly interfere with vision, but some patients have required corneal transplantation[80]. Hepatosplenomegaly may be a consequence of increased lipid accumulation, possibly from decreased cholesterol efflux but also because of accelerated red blood cell removal. FLD subjects can have normocytic normochromic anemia and abnormal red blood cells shapes, most likely because of a disturbance in the exchange of lipids between red blood cells and the abnormal level and type of lipoproteins in these subjects. Renal disease is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with FLD. Proteinuria can develop in childhood and progresses to nephrotic syndrome typically by the fourth to fifth decade of life[95]. Eventually these patients can develop hypertension and end-stage renal disease, which can be treated by renal transplantation, but the disease can reoccur in the renal allograft[95]. A recent report has suggested that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, which reduces proteinuria, may be useful in these patients for delaying the progression of the renal disease[96].

LCAT and Cardiovascular Disease

Although CHD has been reported in FLD and FED patients[82, 87, 90, 91, 97–101], in many cases they do not develop clinically apparent disease[102] and hence the role of LCAT in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis has been controversial. Recently, a relatively large study of carriers of LCAT defects have reported not only reduced HDL-C but also a marked increase in C-reactive protein and in intima media thickness (IMT) of the carotid artery. No significant change in IMT was observed in homozygotes, but an increased incidence of CHD was reported when heterozygotes were compared with controls[90–92, 103–105]. Similar findings for heterozygous subjects were observed in a 25 years follow-up study of a large Canadian LCAT deficient family and in 13 unrelated Italian families with FLD and FED[81, 93]. These results suggest that while heterozygosity for LCAT deficiency is associated with increased IMT and CHD, this may not be true for homozygous subjects, but this could potentially be explained by the low number of homozygous subjects studied. An alternative explantion is that homozygous FLD and FED patients may be partially protected from their low HDL, because they often also have reduced levels of LDL-C compared to heterozygotes and controls[80].

LCAT is not a very polymorphic protein and only a few studies examining genetic variants of the LCAT gene in the general population have been described. A novel P143L SNP with a frequency of about 6% was identified in a Chinese patients with coronary artery disease and was found to be linked with low HDL-C[106]. In contrast, a study of type 2 diabetes found no association between CHD and two other LCAT variants, Arg147Trp and Tyr171Stop[107]. Another LCAT variant, rs2292318, which was initially associated with lower HDL-C in a patient population with CHD, could not be subsequently validated in an independent population sample[108]. The lack of a clear association of LCAT SNPs with CHD may simply be due to lack of prevalent SNPs in the population, the possibility that the SNPs do not alter LCAT activity, and because total variation of HDL-C explained by LCAT SNPs appears to be relatively small[109].

Recently, a study reported greater IMT and elevated LCAT activity in subjects with metabolic syndrome, suggesting that higher LCAT activity may not be beneficial[110]. A similar positive association of LCAT was also observed in patients with angiographically proven CHD[111]. These results are in contrast, however, to multiple earlier papers describing either a negative or no association between LCAT activity and CHD[112–114]. These seemingly contradictory results may potentially be explained by the fact that most of these studies are relatively small and do not examine the other proteins and enzymes in the RCT pathway, which can potentially alter the effect of LCAT on atherosclerosis. For example, low LCAT activity when also linked with elevated levels of pre-beta HDL was associated CHD[115]. Another possible explanation for the contradictory results is that there may be other biochemical markers for the cholesterol esterification process that are better than the in vitro LCAT activity assay for assessing the HDL maturation process, such as the fractional esterification rate of apoB-depleted plasma (FERHDL)[116, 117]. Finally, it is important to note that it is impossible to p determine from epidemiologic studies whether LCAT is playing a causal role in promoting or decreasing atherosclerosis or instead may be being up or down regulated by some sort of compensatory response.

Summary

Although LCAT has been a subject of great interest in cardiovascular research for several decades, we still do not have a clear answer on its role in the pathogenesis of CHD. The preponderance of evidence appears to support the original contention by Glomset[3] that LCAT is an anti-atherogenic factor, but its effect is dependent upon other factors that modulate the RCT pathway, such as CETP. As was observed in mice[70], it is possible that LCAT could be pro-atherogenic for a subset of patients, with a particular lipoprotein disorder or profile that may alter the normal affect of LCAT on CHD. Our incomplete understanding of LCAT has discouraged efforts by drug companies to develop agents to modulate LCAT activity for the treatment of CHD. A small molecule that activates LCAT, however, has recently been described, but it is only in pre-clinical testing[118]. There may also be utility in increasing LCAT levels when reconstituted forms of HDL are infused in patients for the rapid stabilization of patients with acute coronary syndrome[4]. Under these circumstances, LCAT may perhaps become rate limiting and the addition of extra LCAT may potentiate the beneficial effects of the infused HDL. Besides using small molecule activators of LCAT or drugs that may increase the transcription of LCAT, the use of recombinant LCAT protein may be a good strategy for acutely raising LCAT, during HDL therapy4. Although it is a rare disorder, recombinant LCAT protein may also be useful as an enzyme replacement therapy agent for the prevention of renal disease in FLD subjects, particularly because of its relatively long half-life[119, 120], and the fact that LCAT acts in the plasma compartment and does not need to be delivered to a specific tissue or cellular compartment. Finally, once the complex interaction between LCAT and atherosclerosis is better understood, the measurement of some aspect of LCAT activity could potentially also aid in cardiovascular risk assessment.

Table 4.

Plasma Lipids and Lipoprotein Profile in Patients with FLD

| FLD (range) | Reference Range | |

|---|---|---|

| TC (mg/dL) | 173 (89–323) | 120–280 |

| TG (mg/dL) | 605 (85–1480) | 40–250 |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | 8 (0–16) | 30–85 |

| Apo A-I (mg/dL) | 39 (36–48) | 90–190 |

| CE/TC | 0.06 (0.06–0.49) | 0.67–0.71 |

| CER (nmoL/mL/h) | 1 (0–16) | 40–80 |

| LCAT mass (μg/mL) | 0.5 (0–2.6) | 3.8–6.6 |

TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; CE/TC: cholesteryl ester/total cholesterol ratio; LCAT: lecithin:cholesteryl acyltransferase; CER: cholesteryl esterification rate. Data from approximately 50 FLD subjects are shown as mean with range in parenthesis. Modified from ref. 95 with additional data from ref. 105 and 127.

Acknowledgments

XR, BV, MA, and AT were supported by intramural NHLBI research funds. AS was supported by the Danish Agency for Science Technology and Innovation.

REFERENCE LIST

- 1.Glomset JA. The mechanism of the plasma cholesterol esterification reaction: plasma fatty acid transferase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1962;65:128–35. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(62)90156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glomset JA, Janssen ET, Kennedy R, Dobbins J. Role of plasma lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase in the metabolism of high density lipoproteins. J Lipid Res. 1966;7:638–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glomset JA. The plasma lecithins:cholesterol acyltransferase reaction. J Lipid Res. 1968;9:155–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **4.Remaley AT, Amar M, Sviridov D. HDL-replacement therapy: mechanism of action, types of agents and potential clinical indications. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2008;6:1203–15. doi: 10.1586/14779072.6.9.1203. A review on a potential new strategy for treating cardiovascular disease by HDL-replacement. It discusses gaps in our current knowledge of this therapy and what studies need to be performed to validate this approach. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLean J, Fielding C, Drayna D, et al. Cloning and expression of human lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase cDNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986;83:2335–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.8.2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warden CH, Langner CA, Gordon JI, et al. Tissue-specific expression, developmental regulation, and chromosomal mapping of the lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase gene. Evidence for expression in brain and testes as well as liver. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:21573–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hixson JE, Driscoll DM, Birnbaum S, Britten ML. Baboon lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT): cDNA sequences of two alleles, evolution, andgene expression. Gene. 1993;128:295–9. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90578-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith KM, Lawn RM, Wilcox JN. Cellular localization of apolipoprotein D and lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase mRNA in rhesus monkey tissues by in situ hybridization. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:995–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vaisman BL, Klein HG, Rouis M, et al. Overexpression of human lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase leads to hyperalphalipoproteinemia in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12269–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.20.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoeg JM, Santamarina-Fojo S, Berard AM, et al. Overexpression of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase in transgenic rabbits prevents diet-induced atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:11448–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeg JM, Vaisman BL, Demosky SJ, Jr, et al. Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase overexpression generates hyperalpha-lipoproteinemia and a nonatherogenic lipoprotein pattern in transgenic rabbits. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4396–402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Albers JJ, Tollefson JH, Wolfbauer G, Albright RE., Jr Cholesteryl ester transfer protein in human brain. Int J Clin Lab Res. 1992;21:264–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02591657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staels B, van Tol A, Skretting G, Auwerx J. Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase gene expression is regulated in a tissue-selective manner by fibrates. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:727–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Homma Y, Ozawa H, Kobayashi T, et al. Effects of bezafibrate therapy on subfractions of plasma low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein, and on activities of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and cholesteryl ester transfer protein in patients with hyperlipoproteinemia. Atherosclerosis. 1994;106:191–201. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *15.Yvan-Charvet L, Matsuura F, Wang N, et al. Inhibition of cholesteryl ester transfer protein by torcetrapib modestly increases macrophage cholesterol efflux to HDL. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1132–8. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.106.138347. A study examining the effect of torcetrapib, a CETP-inhibitor on HDL. It showed that the drug increased the content of apoE and LCAT on lipid-rich forms of HDL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mishra M, Durrington P, Mackness M, et al. The effect of atorvastatin on serum lipoproteins in acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62:650–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *71.Kassai A, Illyes L, Mirdamadi HZ, et al. The effect of atorvastatin therapy on lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase, cholesteryl ester transfer protein and the antioxidant paraoxonase. Clin Biochem. 2007;40:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.05.016. Atorvastatin is a statin known to decrease LDL-cholesterol. This paper describes the previously unknown effects of atorvastatin on HDL remodeling enzymes on LCAT, and other lipoprotein modifying enzymes. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murata Y, Maeda E, Yoshino G, Kasuga M. Cloning of rabbit LCAT cDNA: increase in LCAT mRNA abundance in the liver of cholesterol-fed rabbits. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:1616–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peelman F, Goethals M, Vanloo B, et al. Structural and functional properties of the 154–171 wild-type and variant peptides of human lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249:708–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-2-00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang CY, Manoogian D, Pao Q, et al. Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. Functional regions and a structural model of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:3086–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adimoolam S, Jin L, Grabbe E, et al. Structural and functional properties of two mutants of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (T123I and N228K) J Biol Chem. 1998;273:32561–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.49.32561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peelman F, Vinaimont N, Verhee A, et al. A proposed architecture for lecithin cholesterol acyl transferase (LCAT): identification of the catalytic triad and molecular modeling. Protein Sci. 1998;7:587–99. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560070307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jin L, Shieh JJ, Grabbe E, et al. Surface plasmon resonance biosensor studies of human wild-type and mutant lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase interactions with lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 1999;38:15659–65. doi: 10.1021/bi9916729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brasseur R, Pillot T, Lins L, et al. Peptides in membranes: tipping the balance of membrane stability. Trends Biochem Sci. 1997;22:167–71. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(97)01047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Francone OL, Fielding CJ. Effects of site-directed mutagenesis at residues cysteine-31 and cysteine-184 on lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:1716–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller KR, Wang J, Sorci-Thomas M, et al. Glycosylation structure and enzyme activity of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase from human plasma, HepG2 cells, and baculoviral and Chinese hamster ovary cell expression systems. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:551–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ayyobi AF, Lacko AG, Murray K, et al. Biochemical and compositional analyses of recombinant lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) obtained from a hepatic source. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1484:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00199-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francone OL, Evangelista L, Fielding CJ. Lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase: effects of mutagenesis at N-linked oligosaccharide attachment sites on acyl acceptor specificity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1166:301–4. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(93)90110-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schindler PA, Settineri CA, Collet X, et al. Site-specific detection and structural characterization of the glycosylation of human plasma proteins lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase and apolipoprotein D using HPLC/electrospray mass spectrometry and sequential glycosidase digestion. Protein Sci. 1995;4:791–803. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francone OL, Evangelista L, Fielding CJ. Effects of carboxy-terminal truncation on human lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase activity. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:1609–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosman J, Jonas A. Deletion of specific glycan chains affects differentially the stability, local structures, and activity of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:37230–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Subbaiah PV, Albers JJ, Chen CH, Bagdade JD. Low density lipoprotein-activated lysolecithin acylation by human plasma lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase. Identity of lysolecithin acyltransferase and lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:9275–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rajaram OV, Barter PJ. Reactivity of human lipoproteins with purified lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase during incubations in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1985;835:41–9. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(85)90028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grove D, Pownall HJ. Comparative specificity of plasma lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase from ten animal species. Lipids. 1991;26:416–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02536066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Portman OW, Sugano M. Factors Influencing the Level and Fatty Acid Specificity of the Cholesterol Esterification Activity in Human Plasma. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1964;105:532–40. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(64)90048-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Christiaens B, Vanloo B, Gouyette C, et al. Headgroup specificity of lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase for monomeric and vesicular phospholipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1486:321–7. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bolin DJ, Jonas A. Sphingomyelin inhibits the lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase reaction with reconstituted high density lipoproteins by decreasing enzyme binding. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:19152–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.32.19152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Subbaiah PV, Kaufman D, Bagdade JD. Incorporation of dietary n-3 fatty acids into molecular species of phosphatidyl choline and cholesteryl ester in normal human plasma. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:360–8. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rye KA, Hime NJ, Barter PJ. The influence of sphingomyelin on the structure and function of reconstituted high density lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4243–50. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.8.4243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sparks DL, Pritchard PH. The neutral lipid composition and size of recombinant high density lipoproteins regulates lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase activity. Biochem Cell Biol. 1989;67:358–64. doi: 10.1139/o89-056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fielding CJ, Shore VG, Fielding PE. A protein cofactor of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;46:1493–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(72)90776-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jonas A. Lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase in the metabolism of high-density lipoproteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1084:205–20. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(91)90062-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao Y, Thorngate FE, Weisgraber KH, et al. Apolipoprotein E is the major physiological activator of lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) on apolipoprotein B lipoproteins. Biochemistry. 2005;44:1013–25. doi: 10.1021/bi0481489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexander ET, Bhat S, Thomas MJ, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I helix 6 negatively charged residues attenuate lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) reactivity. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5409–19. doi: 10.1021/bi047412v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sviridov D, Hoang A, Sawyer WH, Fidge NH. Identification of a sequence of apolipoprotein A-I associated with the activation of Lecithin:Cholesterol acyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19707–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000962200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoang A, Huang W, Sasaki J, Sviridov D. Natural mutations of apolipoprotein A-I impairing activation of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1631:72–6. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(02)00357-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roosbeek S, Vanloo B, Duverger N, et al. Three arginine residues in apolipoprotein A-I are critical for activation of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:31–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winkler FK, D’Arcy A, Hunziker W. Structure of human pancreatic lipase. Nature. 1990;343:771–4. doi: 10.1038/343771a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.van Tilbeurgh H, Egloff MP, Martinez C, et al. Interfacial activation of the lipase-procolipase complex by mixed micelles revealed by X-ray crystallography. Nature. 1993;362:814–20. doi: 10.1038/362814a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Peng DQ, Brubaker G, Wu Z, et al. Apolipoprotein A-I tryptophan substitution leads to resistance to myeloperoxidase-mediated loss of function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:2063–70. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *51.Davidson WS, Thompson TB. The structure of apolipoprotein A-I in high density lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22249–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700014200. A recent report on the structure of apo A-I. An understanding of this structure should be helpful in revealing how apo A-I activates LCAT. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.May P, Woldt E, Matz RL, Boucher P. The LDL receptor-related protein (LRP) family: an old family of proteins with new physiological functions. Ann Med. 2007;39:219–28. doi: 10.1080/07853890701214881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schwartz CC, VandenBroek JM, Cooper PS. Lipoprotein cholesteryl ester production, transfer, and output in vivo in humans. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1594–607. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300511-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maric J, Kiss RS, Franklin V, Marcel YL. Intracellular lipidation of newly synthesized apolipoprotein AI in primary murine hepatocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39942–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507733200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bodzioch M, Orso E, Klucken J, et al. The gene encoding ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 is mutated in Tangier disease. Nat Genet. 1999;22:347–51. doi: 10.1038/11914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brooks-Wilson A, Marcil M, Clee SM, et al. Mutations in ABC1 in Tangier disease and familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency. Nat Genet. 1999;22:336–45. doi: 10.1038/11905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zannis VI, Chroni A, Kypreos KE, et al. Probing the pathways of chylomicron and HDL metabolism using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2004;15:151–66. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200404000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang N, Lan D, Chen W, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9774–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403506101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, et al. Identification of Scavenger Receptor SR-BI as a High Density Lipoprotein Receptor. Science. 1996;271:518–520. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5248.518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murao K, Terpstra V, Green SR, et al. Characterization of CLA-1, a Human Homologue of Rodent Scavenger Receptor BI, as a Receptor for High Density Lipoprotein and Apoptotic Thymocytes. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:17551–17557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Czarnecka H, Yokoyama S. Regulation of cellular cholesterol efflux by lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase reaction through nonspecific lipid exchange. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2023–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chajek T, Fielding CJ. Isolation and characterization of a human serum cholesteryl ester transfer protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:3445–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fielding CJ. The human plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein: structure, function and physiology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1988;243:219–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-0733-4_27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Francone OL, Gong EL, Ng DS, et al. Expression of human lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase in transgenic mice. Effect of human apolipoprotein AI and human apolipoprotein all on plasma lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:1440–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI118180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mehlum A, Staels B, Duverger N, et al. Tissue-specific expression of the human gene for lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase in transgenic mice alters blood lipids, lipoproteins and lipases towards a less atherogenic profile. Eur J Biochem. 1995;230:567–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.tb20597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **66.Amar M, Shamburek R, Vaisman BL, et al. Adenovirus-mediatedexpression of LCAT in non-human primates leads to an anti-atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype by increasing HDL and lowering LDL. Metabolism. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2008.11.019. In Press. Overexpression by adenovirus of human LCAT in non-human primates resulted in an anti-atherogenic lipoprotein profile, by increasing HDL-C and lowering apo B. These results along with the potential beneficial changes in kinetic parameters for apoA-I and apoB suggest that, like in rabbits, increased expression of LCAT in an animal model that expresses CETP is most likely anti-atherogenic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sakai N, Vaisman BL, Koch CA, et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) gene. Generation of a new animal model for human LCAT deficiency. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7506–10. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.11.7506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ng DS, Francone OL, Forte TM, et al. Disruption of the murine lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase gene causes impairment of adrenal lipid delivery and up-regulation of scavenger receptor class B type I. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15777–81. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Foger B, Chase M, Amar MJ, et al. Cholesteryl ester transfer protein corrects dysfunctional high density lipoproteins and reduces aortic atherosclerosis in lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36912–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.36912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Berard AM, Foger B, Remaley A, et al. High plasma HDL concentrations associated with enhanced atherosclerosis in transgenic mice overexpressing lecithin-cholesteryl acyltransferase. Nat Med. 1997;3:744–9. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brousseau ME, Santamarina-Fojo S, Vaisman BL, et al. Overexpression of human lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase in cholesterol-fed rabbits: LDL metabolism and HDL metabolism are affected in a gene dose-dependent manner. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:2537–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Brousseau ME, Kauffman RD, Herderick EE, et al. LCAT modulates atherogenic plasma lipoproteins and the extent of atherosclerosis only in the presence of normal LDL receptors in transgenic rabbits. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2000;20:450–8. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.20.2.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mehlum A, Gjernes E, Solberg LA, et al. Overexpression of human lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase in mice offers no protection against diet-induced atherosclerosis. APMIS. 2000;108:336–42. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0463.2000.d01-65.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Furbee JW, Jr, Parks JS. Transgenic overexpression of human lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) in mice does not increase aortic cholesterol deposition. Atherosclerosis. 2002;165:89–100. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(02)00201-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lambert G, Sakai N, Vaisman BL, et al. Analysis of glomerulosclerosis and atherosclerosis in lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15090–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu X, Herzenberg AM, Eskandarian M, et al. A novel in vivo lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT)-deficient mouse expressing predominantly LpX is associated with spontaneous glomerulopathy. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1269–78. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63386-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Forte TM, Oda MN, Knoff L, et al. Targeted disruption of the murine lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase gene is associated with reductions in plasma paraoxonase and platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase activities but not in apolipoprotein J concentration. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:1276–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Furbee JW, Jr, Sawyer JK, Parks JS. Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency increases atherosclerosis in the low density lipoprotein receptor and apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3511–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ng DS, Maguire GF, Wylie J, et al. Oxidative stress is markedly elevated in lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase-deficient mice and is paradoxically reversed in the apolipoprotein E knockout background in association with a reduction in atherosclerosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11715–20. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Santamarina-Fojo S, Hoeg JM, Assmann G, Brewer JHB. The metabolic and molecular bases of inherited diseas. 2001. pp. 2817–33. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Calabresi L, Pisciotta L, Costantin A, et al. The molecular basis of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency syndromes: a comprehensive study of molecular and biochemical findings in 13 unrelated Italian families. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1972–8. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000175751.30616.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuivenhoven JA, Pritchard H, Hill J, et al. The molecular pathology of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency syndromes. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:191–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gjone E, Norum KR. Familial serum cholesterol ester deficiency. Clinical study of a patient with a new syndrome. Acta Med Scand. 1968;183:107–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Norum KR, Gjone E. Familial serum-cholesterol esterification failure. A new inborn error of metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1967;144:698–700. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(67)90064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Carlson LA, Philipson B. Fish-eye disease. A new familial condition with massive corneal opacities and dyslipoproteinaemia. Lancet. 1979;2:922–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Carlson LA, Holmquist L. Paradoxical esterification of plasma cholesterol in fish eye disease. Acta Med Scand. 1985;217:491–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0954-6820.1985.tb03252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.OK, Hill JS, Wang X, Pritchard PH. Recombinant lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase containing a Thr123-->Ile mutation esterifies cholesterol in low density lipoprotein but not in high density lipoprotein. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:81–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Klein HG, Duverger N, Albers JJ, et al. In vitro expression of structural defects in the lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase gene. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9443–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Klein HG, Santamarina-Fojo S, Duverger N, et al. Fish eye syndrome: a molecular defect in the lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) gene associated with normal alpha-LCAT-specific activity. Implications for classification and prognosis. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:479–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI116591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kuivenhoven JA, van Voorst tot Voorst EJ, Wiebusch H, et al. A unique genetic and biochemical presentation of fish-eye disease. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2783–91. doi: 10.1172/JCI118348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Funke H, von Eckardstein A, Pritchard PH, et al. A molecular defect causing fish eye disease: an amino acid exchange in lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) leads to the selective loss of alpha-LCAT activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4855–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kuivenhoven JA, Weibusch H, Pritchard PH, et al. An intronic mutation in a lariat branchpoint sequence is a direct cause of an inherited human disorder (fish-eye disease) J Clin Invest. 1996;98:358–64. doi: 10.1172/JCI118800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ayyobi AF, McGladdery SH, Chan S, et al. Lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency and risk of vascular disease: 25 year follow-up. Atherosclerosis. 2004;177:361–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nofer JR, Remaley AT. Tangier disease: still more questions than answers. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2005;62:2150–60. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5125-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Panescu V, Grignon Y, Hestin D, et al. Recurrence of lecithin cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency after kidney transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997;12:2430–2. doi: 10.1093/ndt/12.11.2430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **96.Aranda P, Valdivielso P, Pisciotta L, et al. Therapeutic management of a new case of LCAT deficiency with a multifactorial long-term approach based on high doses of angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) Clin Nephrol. 2008;69:213–8. doi: 10.5414/cnp69213. A case report on the use of ACE inhibitors for treating renal disease in patients with LCAT deficiency. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kuivenhoven JA, Stalenhoef AF, Hill JS, et al. Two novel molecular defects in the LCAT gene are associated with fish eye disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1996;16:294–303. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.16.2.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Owen JS, Wiebusch H, Cullen P, et al. Complete deficiency of plasma lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) activity due to a novel homozygous mutation (Gly-30-Ser) in the LCAT gene. Hum Mutat. 1996;8:79–82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:1<79::AID-HUMU13>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wiebusch H, Cullen P, Owen JS, et al. Deficiency of lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase due to compound heterozygosity of two novel mutations (Gly33Arg and 30 bp ins) in the LCAT gene. Hum Mol Genet. 1995;4:143–5. doi: 10.1093/hmg/4.1.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yang XP, Inazu A, Honjo A, et al. Catalytically inactive lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) caused by a Gly 30 to Ser mutation in a family with LCAT deficiency. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:585–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *101.Scarpioni R, Paties C, Bergonzi G. Dramatic atherosclerotic vascular burden in a patient with familial lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23:1074. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfm760. An interesting case of a patient with FLD, who developed severe peripheral vascular disease at the age of 42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Berard AM, Clerc M, Brewer B, Jr, Santamarina-Fojo S. A normal rate of cellular cholesterol removal can be mediated by plasma from a patient with familial lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;314:131–9. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(01)00689-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hovingh GK, de Groot E, van der Steeg W, et al. Inherited disorders of HDL metabolism and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:139–45. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000162318.47172.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hovingh GK, Hutten BA, Holleboom AG, et al. Compromised LCAT function is associated with increased atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2005;112:879–84. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.540427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kastelein JJ, Pritchard PH, Erkelens DW, et al. Familial high-density-lipoprotein deficiency causing corneal opacities (fish eye disease) in a family of Dutch descent. J Intern Med. 1992;231:413–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb00953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang K, Zhang S, Zheng K, et al. Novel P143L polymorphism of the LCAT gene is associated with dyslipidemia in Chinese patients who have coronary atherosclerotic heart disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;318:4–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.03.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Izar MC, Helfenstein T, Ihara SS, et al. Association of lipoprotein lipase D9N polymorphism with myocardial infarction in type 2 diabetes The genetics, outcomes, and lipids in type 2 diabetes (GOLD) study. Atherosclerosis. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Pare G, Serre D, Brisson D, et al. Genetic analysis of 103 candidate genes for coronary artery disease and associated phenotypes in a founder population reveals a new association between endothelin-1 and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:673–82. doi: 10.1086/513286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Spirin V, Schmidt S, Pertsemlidis A, et al. Common Single-Nucleotide Polymorphisms Act in Concert to Affect Plasma Levels of High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol. Am J Hum Genet. 2007:81. doi: 10.1086/522497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *110.Dullaart RP, Perton F, Sluiter WJ, et al. Plasma lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase activity is elevated in metabolic syndrome and is an independent marker of increased carotid artery intima media thickness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4860–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1213. A recent report showing that high LCAT activity in patients with metabolic syndrome was associated with increased CHD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wells IC, Peitzmeier G, Vincent JK. Lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase and lysolecithin in coronary atherosclerosis. Exp Mol Pathol. 1986;45:303–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(86)90019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ruhling K, Lang A, Richard F, et al. Net mass transfer of plasma cholesteryl esters and lipid transfer proteins in normolipidemic patients with peripheral vascular disease. Metabolism. 1999;48:1361–6. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Solajic-Bozicevic N, Stavljenic A, Sesto M. Lecithin:cholesterol acyltransferase activity in patients with acute myocardial infarction and coronary heart disease. Artery. 1991;18:326–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Solajic-Bozicevic N, Stavljenic-Rukavina A, Sesto M. Lecithin-cholesterol acryltransferase activity in patients with coronary artery disease examined by coronary angiography. Clin Investig. 1994;72:951–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00577734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Miida T, Nakamura Y, Inano K, et al. Pre beta 1-high-density lipoprotein increases in coronary artery disease. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1992–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Dobiasova M, Frohlich J. Measurement of fractional esterification rate of cholesterol in plasma depleted of apoprotein B containing lipoprotein: methods and normal values. Physiol Res. 1996;45:65–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Frohlich J, Dobiasova M. Fractional esterification rate of cholesterol and ratio of triglycerides to HDL-cholesterol are powerful predictors of positive findings on coronary angiography. Clin Chem. 2003;49:1873–80. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2003.022558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **118.Zhou M, Fordstrom P, Zhang J, et al. Novel small molecule LCAT activators raise HDL levels in rodent models. ATVB Meeting. 2008:174. [Google Scholar]

- 119.Murayama N, Asano Y, Kato K, et al. Effects of plasma infusion on plasma lipids, apoproteins and plasma enzyme activities in familial lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency. Eur J Clin Invest. 1984;14:122–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1984.tb02100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Norum KR, Gjone E. The effect of plasma transfusion on the plasma cholesterol esters in patients with familial plasma lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase deficiency. Scand J Clin LabInvest. 1968;22:339–42. doi: 10.3109/00365516809167071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]