Abstract

Objective

To investigate determinants of job satisfaction among home care workers in a consumer-directed model.

Data Sources/Setting

Analysis of data collected from telephone interviews with 1,614 Los Angeles home care workers on the state payroll in 2003.

Data Collection and Analysis

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to determine the odds of job satisfaction using job stress model domains of demands, control, and support.

Principal Findings

Abuse from consumers, unpaid overtime hours, and caring for more than one consumer as well as work-health demands predict less satisfaction. Some physical and emotional demands of the dyadic care relationship are unexpectedly associated with greater job satisfaction. Social support and control, indicated by job security and union involvement, have a direct positive effect on job satisfaction.

Conclusions

Policies that enhance the relational component of care may improve workers' ability to transform the demands of their job into dignified and satisfying labor. Adequate benefits and sufficient authorized hours of care can minimize the stress of unpaid overtime work, caring for multiple consumers, job insecurity, and the financial constraints to seeking health care. Results have implications for the structure of consumer-directed models of care and efforts to retain long-term care workers.

Keywords: Long-term care, home care providers, consumer direction

The home care workforce is comprised of 600,000–800,000 workers nationally who provide personal assistance services for the disabled of all ages. Aging of the baby boom generation and high rates of women's employment portend an increased demand for, but diminished supply of, traditional caregivers, making recruitment and retention of workers a critical long-term care issue (Dawson and Surpin 2000; Stone and Weiner 2001; Montgomery et al. 2005;).

Job satisfaction, fostered by the intrinsic rewards of helping others, predicts retention among direct care workers (Denton et al. 2007). Intrinsic rewards, however, are often accompanied by physical and emotional demands of providing care and by inadequate extrinsic rewards (Benjamin and Matthias 2004; Stacey 2005; Geiger-Brown et al. 2007;). The rewards and stressors of the dyadic care relationship, individually experienced by workers, are shaped by long-term care policies. Insufficient authorized hours of care, for example, may force workers to choose between providing less than optimal care or working unpaid overtime hours, creating stress in the care relationship. Financial strain and health status, considered personal stressors in some models (Ejaz et al. 2008), are influenced by long-term care wage and benefit policies (Howes 2008).

Home care workers straddle the informal arena of the home and formal employment (Folbre 2001). Research into their job stressors and support has been sparse compared to research in institutional settings. Theoretical frameworks developed for the nursing home industry (Eaton 2001) have limited applicability to care provided in the home (Kemper 2007). The stress process model, created for unpaid family caregivers (Aneshensel et al. 1995), is likewise limited in its application to paid home care workers.

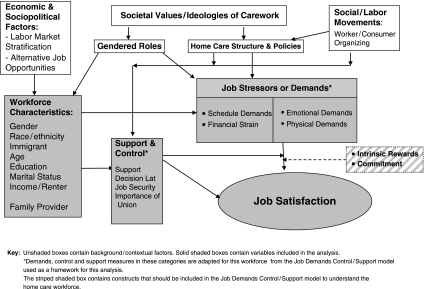

We adapt the Job Demand Control/Support (JDC/S) model as our conceptual framework to examine three dimensions of job-related stress—job demands, control, and support (Karasek 1979; Johnson and Hall 1988;). We conceptualize demands from a multilevel perspective—dyadic care interactions set within home care policies that, together, influence job satisfaction. The dyadic care relationship encompasses the physical and emotional interaction between workers and consumers and the demands and rewards of that interaction. Policies frame the setting within which interactions occur and include wages, benefits, and hours of authorized care that may create schedule, financial, and health stressors for workers.

Control can likewise be conceptualized at two levels—decision latitude over daily job tasks and, at a macro level, a collective voice in policy decisions and job security. Support for workers comes from family and friends, and it may include consumers; by contrast, coworkers and supervisors provide support in traditional employment structures. Control and support may exert direct positive effects on job satisfaction or may attenuate the impact of job demands.

Home care policies originate in the larger sociopolitical and macroeconomic arena as demonstrated in the conceptual model in Figure 1. Cost-cutting and privatization of home care services has been linked to worker dissatisfaction, stress, and turnover (Denton et al. 2007). Policies that allowed for unionization led to higher wages and health benefits, increasing satisfaction and retention (Howes 2004). We examine the degree to which job demands, control, and support predict job satisfaction, and identify policies that could enhance job satisfaction, improving worker retention and quality care.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model—Social, Cultural, Economic, and Political Factors That Shape Home Care Work

In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS)

California has the largest consumer-directed program in the country, IHSS, employing >200,000 workers to provide personal assistance and household chores for over 300,000 low-income elderly and disabled consumers. Most consumers choose their own provider who may be a family member, friend, or worker identified through a registry. County-level public authorities provide administrative services and workers are unionized.

Research comparing worker satisfaction in traditional agency and consumer directed models of care finds satisfaction with working conditions in both models, but dissatisfaction among those in the consumer-directed model who worked more overtime hours and had difficulty finding backup respite care. Stressors were particularly acute among workers who are related to or live with consumers, who care for multiple consumers, or those with greater impairment (Benjamin and Matthias 2004; Foster, Dale, and Brown 2007;).

We first describe workforce characteristics and conditions of work, including demands, support, and control. We then examine the role of each in a multivariate model. Results have implications for discussions about how to shape increasingly popular consumer-directed care (Benjamin and Matthias 2001; Stone and Weiner 2001;).

DESIGN AND METHODS

This study is part of a larger mixed methods investigation (Arteaga et al. 2002; Geiger-Brown et al. 2007;). Focus group methodology and results have been described elsewhere (Delp 2006) and are used here to help interpret survey findings. Pseudonyms protect respondents' anonymity and human subjects protocols were certified by the University of Maryland and UCLA.

Sample

About three-quarters of the 72,000 workers on the 2003 County IHSS payroll reported English or Spanish as their primary language. A probability sample of 4,530 English- and Spanish-speaking workers was generated for this study; limited resources prohibited sampling from the smaller groups of workers who speak many other languages. Half (52 percent) of the sample could not be reached, primarily due to incorrect phone numbers. Ultimately, 74 percent of those contacted (1,614) completed computer-assisted telephone interviews.

Measures

Survey questions were developed or adapted to the home care workforce from existing measures based on results of focus group discussions.1 Measures chosen for this analysis reflect the JDC/S conceptual framework of demands, support, and control as adapted to include emotional demands by Söderfeldt et al. (1996); see Figure 1. Workers were asked about physical, emotional, schedule, and work-health demands; all responses are self-reported. Scales were created from the mean of responses to items with factor loadings of at least 0.60.

Job satisfaction was measured by a four-point Likert scale with workers responding not at all, not too, somewhat, and very satisfied. Only 2.4 percent were “not too” or “not at all” satisfied; thus, responses were collapsed into very satisfied (58.9 percent) and all others.

Predictors include job demands (physical, emotional, schedule, and other), control and support, potential modifiers of job demands, and sociodemographic characteristics.

Two variables indicate physical demands: (1) an overall indicator, “how often is your work physically demanding” on a four-point Likert scale; and (2) frequency of physical tasks scale (α=0.84) created from seven items measuring personal care and household tasks on a five-point Likert scale.

Two variables represent emotional demands: (1) a scale measuring frequency of abuse (α=0.85), comprised of responses on a five-point Likert scale to five items measuring anger, accusations, prejudicial remarks, and unreasonable demands directed at the worker from the consumer or family member; and (2) emotional suppression, a single item with a four-point Likert scale asking how often workers have to “hide their feelings” while providing care.

Three variables involve schedule demands: (1) hours worked per week, (2) unpaid overtime hours, and (3) number of consumers, one or more.

Other demands reflect the intersection of carework, home care policies, and health needs. Workers were asked whether they had health insurance, how many days they worked while sick in the last month, and whether they needed to see a doctor in the past year but could not due to cost.

Control includes several domains: control over daily job tasks, over employment status (job security), and collective control over home care policies (Johnson 1989; Muntaner and Schoenbach 1994;). Control over job tasks was assessed by the JDC/S model's nine-item decision latitude scale (α=0.8) (Karasek 1979) encompassing skill discretion (e.g., “My job requires a high level of skill”; “My job requires that I learn new things”) and decision authority (e.g., “My job allows me to make a lot of decisions on my own”). Workers were also asked, “Are you worried about becoming unemployed?” and “How important is belonging to the union for you?” Responses to the latter were collapsed from three categories—not at all, somewhat, and very—to two categories—very important and all others—because <3 percent responded “not at all.”

Support, a potential effect modifier (Johnson and Hall 1988), was measured on a four-point Likert scale by the mean of two items (r=0.7), the ability to rely on one's spouse, friends, or relatives when things are tough at work, and their willingness to listen to personal problems.

Gender, race/ethnicity, age, education, marital status, home ownership, and household income were included in the model. Immigrant status and language (English versus Spanish) were excluded due to multicollinearity with race/ethnicity. Wages—then U.S.$7.50/hour—do not vary within the study county and are excluded. Financial strain was measured on a four-point Likert scale, “how difficult is it for your family to pay the bills?” A composite variable combines relationship between the worker and the consumer (related or not) and worker coresidence with the consumer.

Analysis

Stata version 8 was used for data analysis. Missing data were imputed using the multiple imputation method (Royston 2004, 2005). Multivariate logistic regression analysis determined the odds of being very satisfied versus somewhat, not too, or not at all satisfied by constructs of job-related demands, control, and support. Interaction terms between job demands and related support and control variables were created to determine whether support and control attenuated the impact of job demands.

RESULTS

Descriptive Results

Workers are primarily female (86 percent), middle-aged (mean of 52 years), ethnically diverse (32 percent African Americans, 23 percent whites, and 45 percent Hispanic), and poor (median household income of U.S.$11,000) (see Table 1). Almost half (47 percent) find it very or somewhat difficult to pay the bills. Two-thirds (67 percent) graduated from high school; 49 percent of Hispanics, 80 percent of African Americans, and 83 percent of whites. Immigrants comprise 53 percent overall; 94 percent of Hispanics, 2 percent of African Americans, and 44 percent of whites.

Table 1.

Distribution of Variables (SD in Parentheses), N=1,614

| Sociodemographic variables | |

| Mean age | 51.97 (13.50) |

| Gender: % female | 85.69 |

| % Married or living together | 50.50 |

| Race/ethnicity of sample | |

| African American | 32.16 |

| White | 22.99 |

| Hispanic | 44.86 |

| % Renters | 58.85 |

| Household income | 10,720 (mean) |

| 11,000 (median) | |

| Difficult to pay bills (1=not at all, 4=very) | 2.39 (1.08) |

| % High school graduate and college | 66.99 |

| % Immigrant | 52.68 |

| % Related to consumer | 71.13 |

| Related, reside in same home (52%) | |

| Related, different home (19%) | |

| Not related, same home (4%) | |

| Not related, different home (26%) | |

| Job-related stressors | |

| Physically demanding (1=never, 4=always) | 2.81 (1.12) |

| Physical tasks frequency (1=infrequent, 5=daily) | 2.03 (0.64) |

| Emotional suppression (1=never, 4=always) | 1.81 (1.15) |

| Abuse (1=never, 5=always) | 1.23 (0.58) |

| Works for >1 consumer | 22.63% |

| Reported hours worked (hours/week) | 33.58 (27.81) |

| Unpaid overtime (hours/week) | 10.80 (15.21) |

| Health insurance | 77.35% |

| Days worked while sick (in last month) | 2.19 (5.0) |

| Financially difficult to see MD | 40.00% |

| Control and support | |

| Decision latitude | 69.16 (8.01) |

| Job insecurity (worried about unemployment) | 54.06% |

| Very important to belong to the union | 57.29% |

| Support (1=very little, 4=a lot) | 2.80 (0.92) |

| Job satisfaction | |

| % Very satisfied | 59.03% |

Almost three-quarters (71 percent) care for relatives; some also care for unrelated consumers. Workers who live with relatives they care for comprise 52 percent of the total sample; another 19 percent care for relatives but live elsewhere. A quarter (26 percent) care for unrelated consumers and live elsewhere while 4 percent live with unrelated consumers they care for.

Workers “often” find the job physically demanding, assisting consumers “one to three times a week” with physical tasks ranging from lifting to bathing to household chores. Workers rarely report abusive behavior from consumers or their family members; emotional suppression is more common. Almost a quarter (23 percent) care for multiple consumers. Home care providers work an average of 34 hours/week over 6.3 days, with considerable variance in reported hours and an average of 10.8 hours of unpaid overtime reported per week. Over three-quarters have health insurance (77 percent), some from union-negotiated health benefits and others, especially Hispanics, from Medi-Cal coverage. However, 40 percent were unable to see a doctor in the last year because of the cost. They worked an average 2.2 days while sick in the previous month.

Home care workers report relatively high decision latitude; a mean of 69.16 on a scale from 24 to 96. Over half (54 percent) worry about becoming unemployed; 86 percent of Hispanic, 27 percent of African American, and 29 percent of white workers; and 57 percent of women versus 36 percent of men. More than half (57 percent) report belonging to the union as very important. Friends and relatives are a source of emotional support, to be relied on to “some extent.” Overall, 59 percent of home care workers report being very satisfied with their job.

Multivariate Analysis

Several physical and emotional demands of home care work are, unexpectedly, associated with higher job satisfaction (Table 2). Workers who report more physical demands or personal assistance services (physical task frequency) have greater odds of being very satisfied. Workers are 25 percent more likely to be very satisfied with each increment of physical demands; 75 percent for physical task frequency. Workers who hide their feelings are 24 percent more likely to be very satisfied with each increment of emotional suppression. By contrast, workers who encounter abuse from consumers or family members are 37 percent less likely to be very satisfied with each increment of abuse frequency.

Table 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Model—Odds of Being Very Satisfied with Home Care Job

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic and economic factors† | |

| Gender (reference=female) | |

| Male | 0.859 (0.592, 1.246) |

| Race/ethnicity (reference=African American) | |

| Caucasian | 1.309 (0.891, 1.921) |

| Hispanic | 0.338 (0.211, 0.542)*** |

| Age | 1.019 (1.009, 1.029)*** |

| Education (reference=HS graduate) | |

| <HS graduate | 1.414 (1.021, 1.956)* |

| >HS | 0.845 (0.598, 1.192) |

| Difficulty paying bills (four-point scale) | 0.964 (0.844, 1.101) |

| Relative/coresidence (reference=worker and consumer related, live in same home) | |

| Related, live in different home | 0.967 (0.728, 1.470) |

| Not related, live in same home | 0.448 (0.222, 0.905)* |

| Not related, live in different home | 1.02 (0.726, 1.436) |

| Physical and emotional demands | |

| Subjective physical demands (four-point scale) | 1.246 (1.089, 1.426)** |

| Physical task frequency (five-point scale) | 1.747 (1.334, 2.289)*** |

| Emotional suppression (four-point scale) | 1.235 (1.097, 1.390)*** |

| Abuse (five-point scale) | 0.634 (0.499, 0.805)*** |

| Schedule demands | |

| Overtime hours | 0.989 (0.979, 0.999)* |

| Number of consumers (reference=1 consumer) | |

| More than one consumer | 0.595 (0.433, 0.818)** |

| Work-health demands | |

| No health insurance (reference=insured) | 1.086 (0.776, 1.517) |

| Days worked while sick | 1.029 (0.998, 1.062) |

| Unable to see doctor due to cost (reference=saw doctor) | 0.668 (0.504, 0.886)** |

| Control | |

| Decision latitude—control over job tasks | 1.000 (0.974, 1.022) |

| Job Security—control over employment | |

| Not worried about becoming unemployed (reference=worried about unemployment) | 1.490 (1.081, 2.054)* |

| Importance of belonging to union (collective control) | |

| Very important (reference=not at all/somewhat important) | 2.632 (1.782, 3.888)*** |

| Social support | |

| Social support (four-point scale) | 1.412 (1.195, 1.669)*** |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001;

Sociodemographic variables omitted from the model due to multicollinearity or small cell size: immigrant, citizenship status, ethnic match between worker and consumer. Variables included in the model but not significant: marital status, log income, homeowner versus renter.

Schedule and work-health demands are associated with low job satisfaction. Workers who care for more than one consumer are 40 percent less likely to be very satisfied than those with only one consumer. Each self-reported unpaid overtime hour is associated with slight but significantly greater odds of being less satisfied. Those unable to see a doctor when needed due to cost are 1/3 less likely to be very satisfied. Health insurance and days worked while sick are not significantly associated with job satisfaction.

Decision latitude is not associated with job satisfaction but control over employment and collective control are. Workers with job security are 1.5 times more likely to be very satisfied than those without and workers who consider belonging to the union very important are 2.6 times more likely to be very satisfied than those who do not. With each increment of social support from friends and relatives, workers are 1.4 times more likely to be very satisfied. Analysis of interaction terms indicates that control and support do not attenuate the impact of demands; rather they exert a direct effect on job satisfaction.

Race/ethnicity, age, education, and relative/coresidence are significantly associated with job satisfaction after controlling for working conditions. Hispanic workers are least likely to be very satisifed; two-thirds less likely than African Americans, the reference group. Workers who did not graduate from high school are 1.4 times more likely to be very satisfied compared with graduates. Older workers are significantly more likely to be very satisfied. Unrelated workers who live with the consumer are 55 percent less likely to be very satisfied compared with related workers who do and significantly less satisfied than all other workers.

DISCUSSION

These findings confirm that home care workers simultaneously experience job stress and satisfaction. They face an array of demands—abuse from consumers, working unpaid hours, and caring for multiple consumers—that predict dissatisfaction, as do job insecurity and the inability to see a physician because of the cost. By contrast, physical demands, emotional suppression, social support, and perception of the union as important predict a greater odds of being very satisfied.

We discuss these results within a multilevel framework to interpret how workers' job satisfaction is influenced by the worker–consumer dyadic interaction and home care polices, including the structure of the IHSS consumer-directed model of care. While in reality these levels are intertwined, the distinct results of each have implications for home care policies in California and beyond. Data from home care worker focus groups help interpret the nuance and complexity of the quantitative findings within the JDC/S framework.

Dyadic Interaction—Transforming Home Care

Most surprising is the association of more physical demands and emotional suppression with greater job satisfaction. While the JDC/S model would predict a negative association, other research shows that workers can transform physical and emotional demands into dignified and satisfying labor by establishing positive relationships with consumers in their care (Aronson and Neysmith 1996; Ibarra 2002; Stacey 2005;). Juana, a focus group participant, stated with obvious satisfaction: “the Señora [I care for] is fascinated with the way I cook; she likes how I keep her house clean.” She described their bond, “She tells me things about her life in her country and I do too. We talk about her family and about mine” (Delp 2006). This suggests that instrumental tasks of cleaning and cooking can embody a deeper meaning than appears on the surface, generating intrinsic rewards and mutual support from meaningful interaction.

Maria conveyed her ability to suppress her feelings for the consumer's well-being: “I like to give them a lot of love, attention … and not show them that we're bored, nor say to them ‘ay, you've already told me that many times,’ but instead to say, ‘is that so?’ as though you've never heard them talk about it so they're comfortable.” Her narrative reflects genuine concern and demonstrates an ongoing relationship, which evokes satisfaction, knowing she has met the unique needs of a particular consumer. In contrast, the construct of emotional labor, created to capture the toll of feigning interest in more casual customers (Hochschild 2003), would be considered a demand in the JDC/S model.

Workers transform some emotional demands into satisfying carework but others outweigh intrinsic rewards. Abusive behavior from consumers or family members creates a hostile environment predicting dissatisfaction in this study and depression in subgroups of the workforce (Geiger-Brown et al. 2007). Focus group participants illustrate the strain of confronting verbal abuse but, simultaneously, their ability to suppress emotions to facilitate communication and their pride in maintaining quality care (Delp 2006).

She accused me of taking from her … two or three times out of the month, we would go over the same tune … Its tough, that's an additional job because you got to take the brutality … falsely accused of something you haven't done, and you can't explode … but ain't nobody else going to take care of them like we do.

Carework is a source of both stress and satisfaction, requiring support to enable workers to transform stressors into satisfying labor. Other research highlights the needs of workers in this environment that is devoid of coworkers and supervisors, traditional sources of support in the JDC/S model. Our results demonstrate a positive association between job satisfaction and social support from friends and family members. Consumers can also be sources of support as described by Juana above and by Cristina: “It can sometimes be a very difficult job, no? I don't have family here but I've had some very good people [consumers] who have given me affection.” However, familial and informal social networks are often inadequate (Pavalko and Woodbury 2000), requiring policy interventions to enhance worker and consumer well-being.

Home Care Policies, Structure, and Context

Policies about paid hours of care, wages, and benefits affect the dynamics of the dyadic care relationship as well as workers' economic well-being, access to health care, and job satisfaction. Elements of the IHSS structure also affect satisfaction.

Home Care Policies

Hours of authorized care that are insufficient to meet consumers' needs and lack of access to respite care lead to unpaid overtime as described in previous studies (Benjamin and Matthias 2004). These policies originate in cost-containment measures and social norms that influence what constitutes paid labor, particularly that provided by a family member. Relatives who live with consumers report significantly more overtime hours than others. Focus group participants describe being “on call 24/7” to care for a grandson who “could have seizures at any time,”“being drained … and having no time for yourself” when caring for a mother who was dying. Unrelated workers also report being on call and unpaid hours waiting with consumers for medical appointments. Trends towards taylorizing care, operationalized by allocating minutes for fragmented physical tasks such as brushing teeth or asserting it should take “only five minutes” to drop them off at the hospital, value instrumental care to the exclusion of affective care and permeate criteria used to authorize hours (Abel 2000; Lopez 2006;). Exacerbating this trend, in 2009 California reduced IHSS coverage, eliminating paid time for some household activities, with the threat that replacing authorized tasks like bathing with unauthorized activities such as meal preparation requested by disabled consumers might be considered worker fraud (Wallace et al. 2009). If fully implemented, this policy may add to workers' job strain by decreasing wages, increasing unpaid hours, and fostering negative interactions between workers and consumers. Such policies negate carework as a social interaction that integrates relationship-building into instrumental tasks, viewing it instead as discrete tasks and casual interactions (Eustis and Fischer 1991; Stone 2000; Stacey 2005;).

Workers who care for multiple consumers are less satisfied. Low wages combined with few authorized hours require workers to care for multiple consumers for financial reasons. In addition, to obtain health insurance benefits they had to work a minimum of 112 hours per month. Finally, workers care for multiple consumers as insurance against a total loss of hours in the event a consumer is hospitalized or dies.

Difficulty paying bills is not significant; however, financial constraints that limit access to health care reduce job satisfaction. Inability to see a physician in the last year because of cost illustrates the impact of a convergence of three policies on this workforce: (1) inadequate health benefits that do not cover all workers nor all costs, (2) no sick leave, requiring workers to forego wages when they miss work for medical appointments, and (3) no backup respite care, forcing workers to choose between caring for themselves and abandoning consumers, or ignoring their own health needs.

These results support Abel and Nelson's (1990) contention that the lack of organizational constraints in home care provides workers' greater flexibility and control than in institutional settings, but leaves them without support to limit their hours, seek health care, or otherwise care for themselves. Leonor, a focus group participant, stated with a sigh, “I would love to have eight hours … to be able to say ay, now I am going to rest.” Policies that authorize inadequate hours of care in essence exploit workers' sense of responsibility (Status of Women 2003), creating stress and diminished satisfaction for those who must choose between the competing demands of work and their own needs. Policies that fail to provide backup respite care also pose a threat to consumers' health; in this study, respondents reported working an average 2.2 days while sick in the previous month because they had no alternative.

Finally, job insecurity emanates from the unstable nature of personal carework in which consumers' hospitalization or death may leave a worker with no income or health benefits. Focus group participants described being “left in the cold” when hours drop suddenly, causing loss of wages and health insurance. Registries ameliorate the impact of job loss by providing access to other consumers through county-level public authorities and/or unions. A temporary financial bridge such as loans, groceries, or other sources of material support could also ameliorate financial strain.

IHSS Structure

Compared with relatives and unrelated workers who do not live with consumers, unrelated workers who live with consumers are less satisfied. Other researchers (Benjamin and Matthias 2004; Foster et al. 2007;) document the stressors and lack of respite care experienced by live-in providers and by relatives, a common feature of consumer-directed models. Our study combines relative status and coresidence, highlighting a potentially important subgroup of workers. Unrelated workers who live with consumers experience unrelenting demands associated with physical and emotional proximity but may experience fewer rewards than related workers. Given the small numbers in this category, results are preliminary. They have important implications, however, as the demand for live-in care increases along with the growth of the “oldest old” segment of society.

Belief in the importance of belonging to the union is associated with greater job satisfaction. Workers in focus groups described the union as a source of instrumental and emotional support and a mechanism to exert influence over policy decisions on behalf of themselves and their consumers. Although others have highlighted the importance of collective control for workers (Johnson 1989; Muntaner and Schoenbach 1994;), limited research exists on unionization in the isolated home care work environment. Findings suggest that actively engaging union members plays a supportive role for individual workers and a collective advocacy role for home care services increasingly threatened by budget cuts (Legislative Analyst's Office 2008; Wallace et al. 2009;).

Sociocultural and Economic Context

Intriguing differences remain between subgroups of the workforce. The greater satisfaction expressed by older workers and those with limited education may be partially due to their competitive disadvantage in the job market and by other factors in Figure 1; home care thus becomes a viable option for those in search of a fulfilling job (Howes 2005; Stacey 2005;).

Hispanic workers report less job satisfaction. Other researchers have also identified unexplained racial differences (Benjamin and Matthias 2004). Possible reasons include differences in the experience and appraisal of demands, in coping strategies, and in access to resources (Aranda and Knight 1997; Dilworth-Anderson, Williams, and Gibson 2002;); others include ethnic segregation and prejudice (Feldman, Sapienza, and Kane 1990; Neysmith and Aronson 1997;). Racial/ethnic differences between African Americans and Hispanics parallel differences in immigrant status and language, making it impossible to distinguish the effects of each. These differences warrant further investigation.

Limitations

Because this study uses cross-sectional data, observed associations are not necessarily causal. The cross-sectional design may also underreport the impact of job demands due to the “healthy worker effect” whereby those with work-related health or other problems leave the workforce (Pavalko and Woodbury 2000). Second, some relevant measures could not be included. Wages, an important extrinsic factor affecting job satisfaction in other studies, do not vary in our sample and so were not included. Objective measures of consumer impairment, which predicted job satisfaction in other research (Benjamin and Matthias 2004), were not available. And immigrant status and language were excluded due to multicollinearity with race/ethnicity. Third, these results represent conditions in one county at one point in time. Other counties have backup respite care, and wages and benefits have since increased. Finally, the generalizability of results is limited by selecting a subsample of eligible workers based on language. Results may not reflect the experience of excluded workers or represent areas with a different mix of racial/ethnic groups. Investigation in other geographic areas is warranted.

The JDC/S model provides an important albeit limited conceptual framework to assess home care working conditions. Demand, support, and control constructs require adaptation to the consumer-directed model of home care. Job stress models typically exclude intrinsic rewards and commitment to consumers, which surfaced in focus groups and which, together with workers relational skills, pride in their work, and supportive policies, may explain how stressors were transformed into satisfying labor. The striped box in Figure 1 contains constructs required to adapt the model for home care workers.

CONCLUSION

Recruitment and retention of workers is critical to meet the demand for long-term care. This study examines determinants of job satisfaction, key to worker retention, in the growing consumer-directed home care model.

Carework, a dyadic relationship between the provider and recipient of care, is both stressful and satisfying. Given adequate support and resources, workers transform some job stressors into satisfying labor. The availability of those resources is influenced by the political and economic context and by social norms, which have historically devalued carework. Worker and consumer organizing have partially countered that trend in California, resulting in policies to create a consumer-directed structure that provides a voice for workers and consumers. Negotiations have increased wages and access to health insurance, reducing worker turnover in some counties, but gaps remain.

This research highlights the need for policies that will enhance the quality of the dyadic care relationship and improve workers' well-being. Job-related stressors result from a convergence of physical, emotional, and schedule demands, and the work-health stressors emanating from inadequate wages and benefits. Policies that reduce demands and enhance control and support can increase job satisfaction. Improved health benefits, sick leave for workers, and backup respite care for consumers would improve workers' access to health care; adequate authorized hours of care and support to deal with emotional demands would minimize stress; and a temporary financial bridge to supplement lost wages when consumers die or are hospitalized would minimize financial strain. Finally, structures that allow workers a voice in policy decisions can enhance worker satisfaction as well as worker involvement in the improvement of home care services. This study highlights several ways home care policy can contribute to worker satisfaction and retention to meet the growing need for long-term care.

Acknowledgments

Joint Acknowledgment/Disclosure Statement: Supported by National Institute for Occupational Safety & Health (NIOSH) grant R01OH007440 and in part by NIA grant 5P30AG021684-07 to Wallace and the UCLA/Drew Center for Health Improvement for Minority Elders (CHIME). The authors thank the Homecare Workers Training Center, SEIU Local 434B staff, and the many home care workers who shared their experiences and inspired the research. UCLA dissertation advisors Emily Abel, Carol Aneshensel, and Judith Siegel contributed to the development of this article as did colleagues from the California Home Care Research Working Group; funds from the UC Institute for Research on Labor and Employment enabled the group to convene. Delp presented preliminary results at the American Public Health Association conference and on behalf of the Research Working Group to the California legislature in support of continued funding for IHSS services.

Disclosures: None.

Disclaimers: None.

NOTE

Survey instrument available from corresponding author.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Appendix SA1: Author Matrix.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

REFERENCES

- Abel EK. A Historical Perspective on Care. In: Meyer MH, editor. Care Work: Gender, Labor and the Welfare State. New York: Routledge; 2000. pp. 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Abel EK, Nelson MK. Circles of Care: An Introductory Essay. In: Abel EK, Nelson MK, editors. Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women's Lives. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1990. pp. 4–34. [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Zarit SH, Whitlatch CJ. Profiles in Caregiving: The Unexpected Career. San Diego: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Aranda MP, Knight BG. The Influence of Ethnicity and Culture on the Caregiver Stress and Coping Process: A Sociocultural Review and Analysis. Gerontologist. 1997;37(3):342–54. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J, Neysmith SM. “You're Not Just in There to Do the Work”: Depersonalizing Policies and the Exploitation of Home Care Workers' Labor. Gender and Society. 1996;10(1):59–77. [Google Scholar]

- Arteaga S, Geiger-Brown J, Muntaner C, Trinkoff A, Lipscomb J, Delp L. Home Care Work Organization and Health: Do Hispanic Women Have Different Concerns? Hispanic Health Care International. 2002;1(3):135–41. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin AE, Matthias R. Age, Consumer Direction, and Outcomes of Supportive Services at Home. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):632–42. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin AE, Matthias R. Work–Life Differences and Outcomes for Agency and Consumer-Directed Home-Care Workers. Gerontologist. 2004;44(4):479–88. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson SL, Surpin R. The Home Health Aide: Scarce Resource in a Competitive Marketplace. Care Management Journals. 2000;2(4):226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delp L. 2006. “Job Stressors among Home Care Workers in California's Consumer-Directed Model of Care: The Impact on Job Satisfaction and Health Outcomes.” Ph.D. dissertation. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Dissertation Services/ProQuest.

- Denton M, Zeytinoglu IU, Kusch K, Davies S. Market Modeled Home Care: Impact on Job Satisfaction and Propensity to Leave. Canadian Public Policy. 2007;33(suppl):S81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Dilworth-Anderson P, Williams IC, Gibson BE. Issues of Race, Ethnicity, and Culture in Caregiving Research: A 20-Year Review (1980–2000) Gerontologist. 2002;42(2):237–72. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton S. Appropriateness of Minimum Nurse Staffing Ratios in Nursing Homes Phase II Final Report, Chapter 5: What a Difference Management Makes! Nursing Staff Turnover Variation with a Single Labor Market. Baltimore: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2001. 64pp. [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz FK, Noelker LS, Menne HL, Bagaka's JG. The Impact of Stress and Support on Direct Care Workers' Job Satisfaction. Gerontologist. 2008;48:60–70. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eustis NN, Fischer LR. Relationships between Home Care Clients and Their Workers: Implications for Quality of Care. Gerontologist. 1991;31(4):447–56. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman PH, Sapienza AM, Kane NM. Who Cares for Them? Workers in the Home Care Industry. New York: Greenwood Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Folbre N. The Invisible Heart: Economics and Family Values. New York: The New Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Foster L, Dale SB, Brown R. How Caregivers and Workers Fared in Cash and Counseling. Health Services Research. 2007;42(1, part 2):510–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger-Brown J, Muntaner C, McPhaul K, Lipscomb J, Trinkoff A. Abuse and Violence during Home Care Work as Predictor of Worker Depression. Home Health Care Services Quarterly. 2007;26(1):59–77. doi: 10.1300/J027v26n01_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling: with a New Afterword. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Upgrading California's Home Care Workforce: The Impact of Political Action and Unionization. In: Milkman R, editor. The State of California Labor. Los Angeles: University of California Institute for Labor and Employment; 2004. pp. 71–106. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Living Waged and Retention of Homecare Workers in San Francisco. Industrial Relations. 2005;44(1):139–63. [Google Scholar]

- Howes C. Love, Money, or Flexibility: What Motivates People to Work in Consumer-Directed Home Care? Gerontologist. 2008;48(1):46–59. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibarra M. Emotional Proletarians in a Global Economy: Mexican Immigrant Women and Elder Care Work. Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development. 2002;(Fall–Winter):17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JV. Collective Control: Strategies for Survival in the Workplace. International Journal of Health Services. 1989;19(3):469–80. doi: 10.2190/H1D1-AB94-JM7X-DDM4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job Strain, Work Place Social Support, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Random Sample of the Swedish Working Population. American Journal of Public Health. 1988;78:1336–42. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek RA., Jr. Job Demands, Job Decision Latitude, and Mental Strain: Implications for Job Redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly. 1979;24(2):285–308. [Google Scholar]

- Kemper P. Commentary: Social Experimentation at Its Best: The Cash and Counseling Demonstration and Its Implications. Health Services Research. 2007;42(1, part 2):577–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legislative Analyst's Office. Analysis of the 2008–2009 Budget Bill: Health & Social Services. Sacramento, CA: Legislative Analyst's Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez EL. 2006. “All-County Letter No. 06-34, RE: Welface and Institutions Code (WIC) Section 12301.2.” C. D. o. S. Services.

- Montgomery RJV, Lyn H, Deichert J, Kosloski K. A Profile of Home Care Workers from the 2000 Census: How It Changes What We Know. Gerontologist. 2005;45(5):595–600. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.5.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntaner C, Schoenbach C. Psychosocial Work Environment and Health in U.S. Metropolitan Areas: A Test of the Demand–Control and Demand–Control–Support Models. International Journal of Health Services. 1994;24(2):337–53. doi: 10.2190/3LYE-Q9W1-FHWJ-Y757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neysmith SM, Aronson J. Working Conditions in Home Care: Negotiating Race and Class Boundaries in Gendered Work. International Journal of Health Services. 1997;27(3):479–99. doi: 10.2190/3YHC-7ET5-5022-8F6L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko EK, Woodbury S. Social Roles as Process: Caregiving Careers and Women's Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(1):91–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple Imputation of Missing Values. Stata Journal. 2004;4(3):227–41. [Google Scholar]

- Royston P. Multiple Imputation of Missing Values: Update. Stata Journal. 2005;5(2):1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Söderfeldt B, Muntaner M, O'Campo P, Warg LE, Ohlson CG. Psychosocial Work Environment in Human Service Organizations: A Conceptual Analylsis and Development of the Demand–Control Model. Social Science and Medicine. 1996;42(9):1217–26. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey CL. Finding Dignity in Dirty Work: The Constraints and Rewards of Low-Wage Home Care Labour. Sociology of Health and Illness. 2005;27(6):831–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Status of Women. The Changing Nature of Home Care and Its Impact on Women's Vulnerability to Poverty. Canada: Status of Women; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Stone D. Caring by the Book. In: Meyer MH, editor. Care Work: Gender, Labor and the Welfare State. New York: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stone RI, Weiner JM. Who Will Care for Us: Addressing the Long-Term Care Workforce Crisis. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute and American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace SP, Benjamin AE, Villa VM, Pourat N. California Budget Cuts Fray the Long-Term Care Safety Net. PB2009-8. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.