Abstract

Aims

A better understanding of the ionic mechanisms for cardiac automaticity can lead to better strategies for engineering bio-artificial pacemakers. Here, we attempted to better define the relative contribution of If and IK1 in the generation of spontaneous action potentials (SAPs) in cardiomyocytes (CMs).

Methods and results

Monolayers of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were transduced with a recombinant adenovirus (Ad) to express a gating-engineered HCN1 construct (HCN1-ΔΔΔ) for patch-clamp and multielectrode array (MEA) recordings. Single NRVMs exhibited a bi-phasic response in the generation of SAPs (62.6 ± 17.4 b.p.m., Days 1–2; 194.3 ± 12.3 b.p.m., Days 3–4; 73% quiescent, Days 9–10). Although automaticity time-dependently decreased and subsequently ceased, If remained fairly stable (−5.2 ± 1.1 pA/pF, Days 1–2; −5.1 ± 1.4 pA/pF, Days 7–8; −4.3 ± 1.3 pA/pF, Days 13–14). In contrast, IK1 declined rapidly (from −16.9 ± 2.7 pA/pF on Days 1–2 to −4.4 ± 1.6 pA/pF on Days 5–6). Maximum diastolic potential/resting membrane potential (r = 0.89) and action potential duration at 50% (APD50, r = 0.73) and 90% (APD90, r = 0.75) but not the firing rate (r = −0.3) were positively correlated to the IK1. Similarly, monolayer NRVMs ceased to spontaneously fire after long-term culture. Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ transduction restored pacing in silenced individual and monolayer NRVMs but with reduced conduction velocity and field potential amplitude.

Conclusion

We conclude that the combination of IK1 and If primes CMs for bio-artificial pacing by determining the threshold. However, If functions as a membrane potential oscillator to determine the basal firing frequency. Future engineering of automaticity in the multicellular setting needs to have conduction taken into consideration.

Keywords: If, IK1, HCN, Automaticity, Action potential

Introduction

Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) have been commonly employed as an in vitro model for studying cellular electrophysiological properties of the heart. When cultured as a confluent monolayer, NRVMs beat spontaneously up to 40 days.1,2 The pacemaker current (If), encoded by hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-modulated (HCN) channel gene family, is known to play an important role in mediating automaticity. If, activated upon hyperpolarization and modulated by intracellular cAMP, depolarizes cells to the action potential (AP) threshold (a.k.a. take-off potential or TOP). We previously demonstrated that focal transduction of an engineered HCN channel in a swine model of sick-sinus syndrome suffices to generate a stable in vivo bio-artificial sinoatrial (SA) node for physiological pacing.3 Overexpression of HCN2 in NRVMs likewise leads to robust If expression and promotes automaticity,4 although the underlying ionic basis has not been fully explored. In contrast, dominant-negative suppression of HCN2 channels markedly reduces native If and even silences spontaneous firing of NRVM.5 Despite the various lines of functional evidence, the mechanistic role of If has been questioned due to its intrinsically slow kinetics and negative activation relative to the time scale and voltage range of cardiac pacing.6–8 On the basis of the experimental observation that IK1 suppression unleashes the latent pacemaker activity of normally silent adult ventricular cardiomyocytes (CMs), it has been suggested that down-regulation of IK1, rather than the up-regulation of If, is the key to automaticity.9,10 Developmentally, IK1 densities markedly increase in the foetal and neonatal hearts to shorten the action potential duration (APD) and hyperpolarize the resting membrane potential (RMP).11–15 Kir2.1 overexpression increases the conduction velocity (CV) by improving the availability of voltage-gated Na+ channels for opening.16 However, the functional interaction between IK1 and If is just beginning to be understood. In a series of computational and functional studies, we demonstrated that the relative If/IK1 activity is crucial for both the induction and the modulation of pacemaking.17–20 Using NRVMs as an in vitro model, here, we tested the hypothesis that alterations of the balance of If and IK1 activities directly lead to changes in the generation of spontaneous action potentials (SAPs). The results are discussed in the context of the dissected individual functional roles of If and IK1 in cardiac automaticity.

Methods

In this study, the time-dependent changes of SAP generation as well as the relationship of If and IK1 were examined using a combination of adenovirus (Ad)-mediated gene transfer and electrophysiological techniques.

Cardiomyocyte isolation and culture

Ventricles from neonatal Wistar rats (0- to 1-day-old) sacrificed by decapitation were quickly removed, rinsed four times with modified Hank's solution, and minced into small pieces on ice. The tissue fragments were then transferred into a 50 mL Falcon tube with the addition of 10 mL of 0.2% trypsin pre-warmed to 37°C. The tube was placed in a water bath on the top of a hot plate stirrer stirring the tissue fragments with a magnetic bar for 10 min at 37°C. The supernatant was discarded to remove dead and blood cells. After that, fresh pre-warmed 0.2% trypsin was added to digest the minced myocardium for another 5 min at 37°C. To stop the digestion, the supernatant was aspirated gently and transferred to a 50 mL tube on ice containing 7 mL foetal bovine serum. These two steps were repeated five times with all the supernatant collected in two 50 mL tubes. Next, the cells were centrifuged at 156.8 g for 5 min with the supernatant aspirated. To reduce fibroblast contamination, the cells re-suspended in NRVM culture medium were pre-plated for 1 h. Again, the supernatant was aspirated gently, and the cells were plated in six-well plates or MEA dishes at the density of 6 × 105 cells/mL. Culture media were changed every day. These procedures reproducibly generate monolayer cultures that contract synchronously at >300 b.p.m. consistent with the normal beating rate of the intact rat heart. For patch-clamping, monolayer cultures were re-suspended by brief exposure to trypsin–EDTA. The cells were re-plated onto gelatin-coated cover slips at a lower density (2 × 105 cells/mL), allowing the cells to settle down overnight subjecting to study within 14–24 h.

Gene transfer

Adenovirus-mediated HCN1 gene transfer was performed as we described previously.17,19 In brief, the bicistronic Ad shuttle vector pAdCMV-GFP-IRES (pAdCGI) was employed. Internal ribosomal entry site (IRES) allows the simultaneous translation of two transgenes with a single transcript and, in our experiments, GFP and an HCN1 construct. HCN1Δ235–237-GFP (HCN1-ΔΔΔ) with shortened S3–S4 linker was cloned into the second position of pAdCGI at EcoRI and XmaI to generate pAdCGI-HCN1-ΔΔΔ (pAdHCN1-ΔΔΔ).21 Adenoviruses were generated by Cre-lox recombination of purified ψ 5 viral DNA and shuttle vector DNA using Cre4 cells. The recombinant products were plaque purified, amplified, and purified again by CsCl gradients, yielding concentrations on the order of 1010 plaque-forming units per 1 mL. As needed, NRVMs were transduced with Ad-CGI or Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ at ∼2 × 109. A transduction efficiency of ∼70–80% could be typically achieved. The dishes were kept at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 overnight, and then the supernatant was discarded. The dishes were washed, refilled with the normal culture medium, and remained in an incubator for 1 day before electrophysiological experiments.

Electrophysiological recording

In patch-clamp experiments, ionic current recordings were performed in the whole-cell mode with individual cells isolated from monolayers being superfused at room temperature (∼23°C). For AP recordings at 36 ± 0.5°C, the perforated-patch technique was employed with 100 µM amphotericin B added to the pipette solution.22 The electrode tip resistances in both cases were ∼3–4 MΩ, whereas the sampling frequencies were 1.25 and 2.00 kHz, respectively. For If recordings, external [K+]o was increased to 25 mM. BaCl2 2 mM, CdCl2 200 µM, and 4-aminopyridine 4 mM were added to block IK1, ICa,L, and Ito, respectively. If was measured as the difference between the instantaneous current at the beginning of a hyperpolarizing step, ranging from −30 to −140 mV in 10 mV increments, and the steady-state current at the end of the 3 s hyperpolarizing step. For IK1 recordings, external [K+]o was also increased to 25 mM. Two hundred micromolars of CdCl2 were added to block ICa,L. INa was inactivated by a holding potential of –30 mV. For Ba2+-sensitive IK1, currents recorded before and after the addition of 2 mM BaCl2 were subtracted. Since measurements of ionic current and AP involved different pipette solutions, cells were subjected to either recording at a time. Averages of 6–16 measurements were performed for each set of parameters.

Multielectrode array recording

In vitro multielectrode array (MEA) recordings were performed at 37°C by simultaneously measuring extracellular field potentials from 60 microelectrodes (of 30 μm diameter) arranged in an 8 × 8 layout grid with a 200 µm inter-electrode distance. Six monolayers of NRVMs were cultured on gelatin-coated MEA plates for experiments. The raw signals were collected at 25 kHz, bandpass filtered, and amplified (Multi-channel Systems), followed by analysis with MC Data Tool V1.3.0 to generate a conduction map based on the time differences at which signals were detected at each of the microelectrodes. Filtered signals were differentiated digitally to determine the local activation time (LAT) at each electrode. Colour-coded activation maps were constructed by plotting the LAT values against the electrode sites. Activation maps were generated using the Matlab standard two-dimensional plotting function (pcolor) (Matlab 5.3; Mathworks Inc.). Conduction velocity was calculated using the first method described previously by Meiry et al.23

Statistical analysis

All data reported are means ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined for all individual data points and fitting parameters using one-way ANOVA with Tukey's HSD post hoc test. Furthermore, correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationships between various AP parameters and IK1 properties. Calculations were performed with OriginPro 7.5 software (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA). A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Bi-phasic changes of the spontaneous action potentials of individual neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

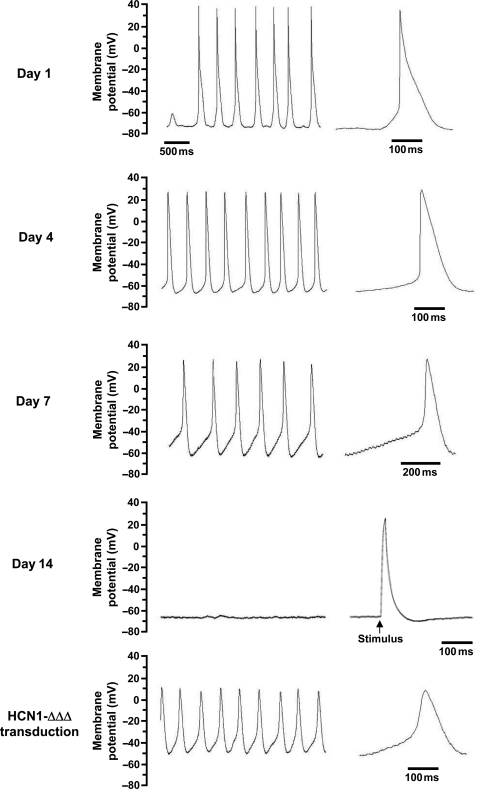

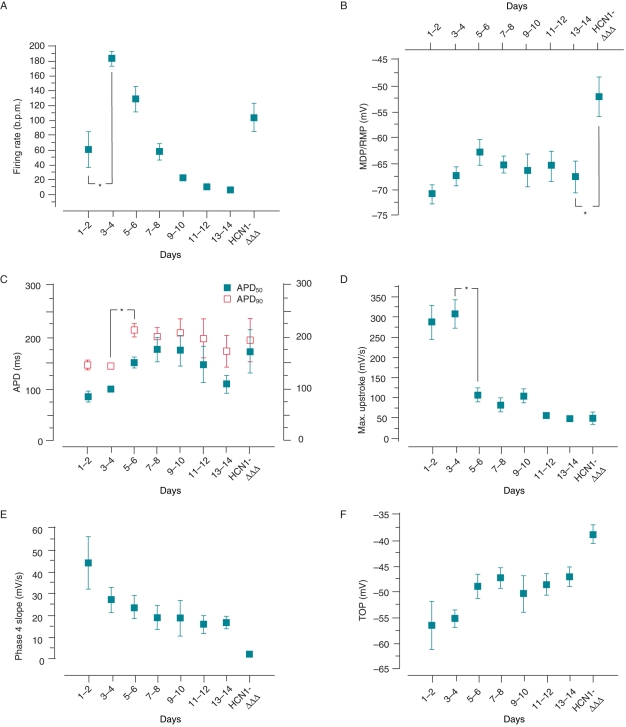

Representative AP tracings recorded from individual NRVMs at different time points are given in Figure 1. Same as previous studies,11,14 no SAPs were observed from freshly isolated NRVMs (n = 12). After 24 h culturing, SAP firing (n = 5) with a mean frequency of 62.6 ± 17.4 b.p.m., a relatively hyperpolarized maximum diastolic potential (MDP = −71.0 ± 1.8 mV), rapid AP upstroke (288.2 ± 41.6 mV/s), and Phase 4 depolarization (43.6 ± 12.4 mV/s) could be recorded. Action potential duration at 50% (APD50) and APD90 were 81.4 ± 10.5 and 144.4 ± 7.6 ms, respectively (Figure 2). On Days 3–4 in culture, AP firing significantly increased and peaked at 194.3 ± 12.3 b.p.m. (n = 10) (P < 0.05). A gradual time-dependent decrease was observed until SAPs completely disappeared on Days 13–14 (n = 12). Maximum diastolic potential further depolarized and stabilized at −63.0 ± 2.5 mV on Days 5–6. In Figure 2C, on Days 1–2 and 3–4 of culture, APD90 was relatively short at 144.4 ± 7.6 and 141.1 ± 5.7 ms, respectively. It then prolonged (212.1 ± 12.8 ms on Days 5–6 and 198.5 ± 18.0 ms on Days 7–8, P < 0.05) when automaticity began to slow down and the recovered cells silenced from Days 9 to 14 (170.2 ± 31.4 ms on Days 13–14). In contrast to the bi-phasic change, both the maximum upstroke velocity and Phase 4 depolarization slope continued to decrease with the TOP becoming more and more depolarized during the course of our experiments (Figure 2D–F).

Figure 1.

Representative SAPs recorded from control and HCN1-ΔΔΔ-transduced NRVMs at 36°C. After 14 days of culture, SAP was abolished but a single AP could be elicited upon electrical stimulation of 0.1–1 nA for 5 ms. Spontaneous action potentials restored 1 day after HCN1-ΔΔΔ transduction. Single APs were magnified to the right for comparison.

Figure 2.

Summary of SAP parameters. Time-dependent change of firing rate (A), MDP/RMP (B), APD at 50% and 90% repolarization (APD50 and APD90) (C), maximum AP upstroke velocity (D), Phase 4 depolarization slope (E), and TOP (F) of control and HCN1-ΔΔΔ-transduced cells. *P < 0.05.

If is not responsible for the time-dependent loss of automaticity, but its overexpression suffices to induce pacing in otherwise silenced neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

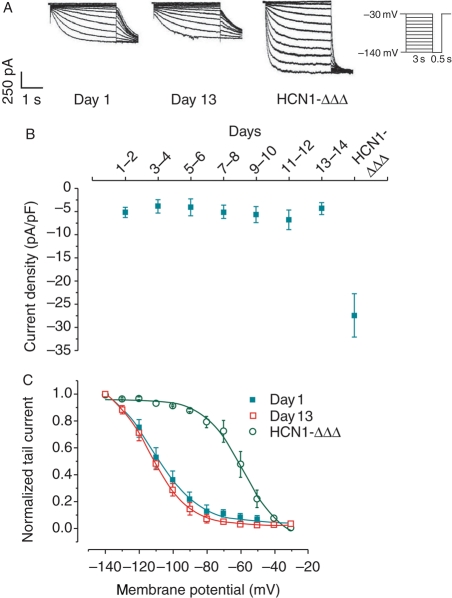

If was elicited by hyperpolarizing steps to −140 mV from a holding potential of −30 mV. Under the physiological extracellular K+ concentration ([K+]o) of 5 mM at room temperature, no measurable hyperpolarization-activated inward current could be recorded from NRVMs (data not shown). As reported previously,5 If was determined after increasing [K+]o to 25 mM (Figure 3A). Interestingly, although the automaticity time-dependently decreased and subsequently became abolished in culture, If remained fairly stable (−5.2 ± 1.1, −5.1 ± 1.4, and −4.3 ± 1.3 pA/pF on Days 1–2, 7–8, and 13–14, respectively; P > 0.05) (Figure 3B). Furthermore, the steady-state activation curves on Days 1 and 13 were identical; the half activation potentials (V1/2) were −109.1 ± 4.2 and −113.2 ± 1.7 mV, respectively (P > 0.05; Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

(A) Representative If current recordings of control (Days 1 and 13) and Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ-transduced cells using the voltage protocol provided in the inset. If remained relatively unchanged in culture and increased significantly after Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ transduction. (B) If at −140 mV of control and Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ-transduced cells. (C) Activation curves of control (Days 1 and 13) and Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ-transduced cells. (n = 7).

Transduction of NRVMs with Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ on Day 13 led to robust expression of If with a current density of −27.5 ± 4.7 pA/pF at −140 mV under the physiological [K+]o. Yet, it was significantly larger than that of control cells recorded at [K+]o of 25 mM (Figure 3A and B). The activation curve also became significantly shifted in the positive direction with a V1/2 of −56.3 ± 4.5 mV (Figure 3C), consistent with what we previously reported for the gating-engineered construct that opens more readily than the wild-type (WT) counterparts.21 The firing rate of 13-day-old quiescent cells 1 day after transduction was 104.8 ± 18.9 b.p.m. (Figures 1 and 2A). In addition, depolarization of MDP (−52.3 ± 3.8 mV) and prolongation of APD (APD50 = 572.6 ± 70.2 ms; APD90 = 707.0 ± 80.2 ms) were also observed (Figure 2B and C).

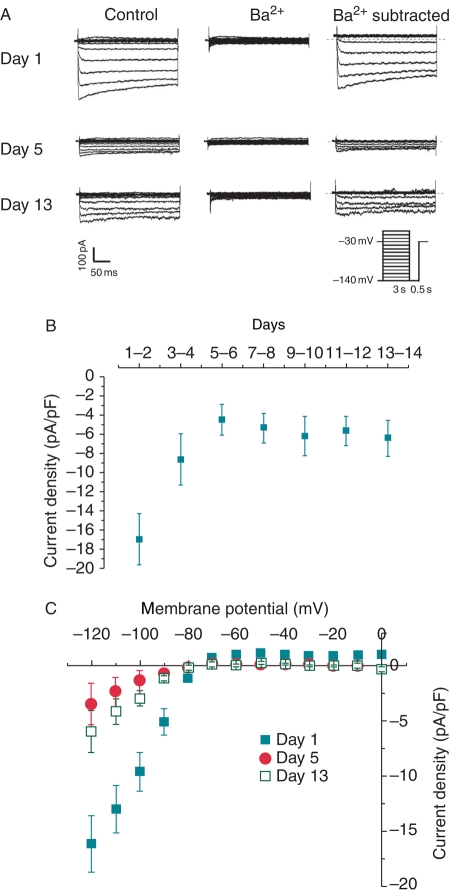

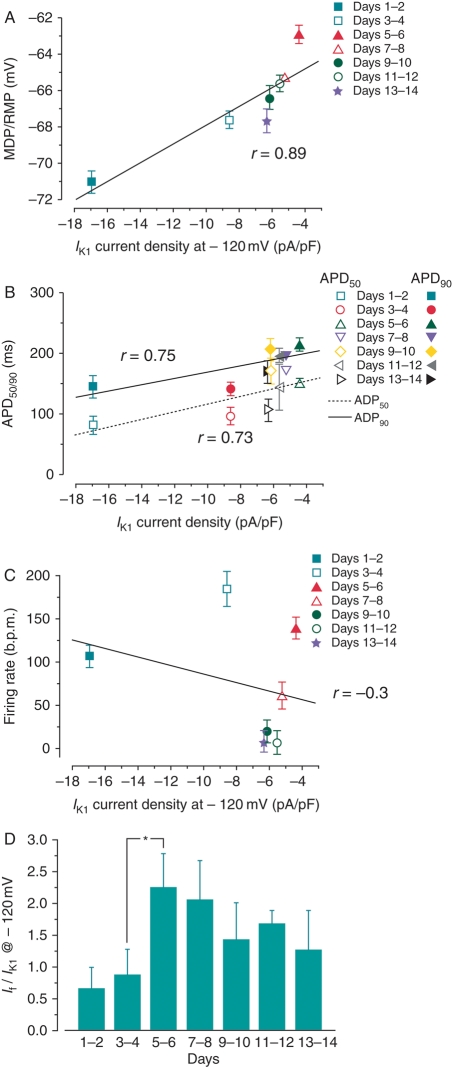

Correlation between IK1 and automaticity

At −120 mV, the IK1 density of was −16.9 ± 2.7 pA/pF on Days 1–2. This declined rapidly to −4.4 ± 1.6 pA/pF on Days 5–6, then modestly recovered to about −6.0 pA/pF by the end of 14 days (Figure 4B). The current–voltage relationships of IK1 in culture are shown in Figure 4C. The reversal potential remained unchanged. Since IK1 displayed a bi-phasic change similar to that of SAP (cf. Figure 2A), correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationships between various AP parameters and IK1 properties. The MDP/RMP (r = 0.89), APD50 (r = 0.73), and APD90 (r = 0.75) of NRVMs during culture were positively correlated to the IK1 current density at –120 mV (Figure 5A and B). In contrast, no obvious correlations were found between firing rate and IK1 density (r = −0.3; Figure 5C). The relative If:IK1 ratio at −120 mV on individual NRVMs during culture showed a sudden increase on Days 3–4 (0.88 ± 0.40) to the maximum value on Days 5–6 (2.25 ± 0.54; P < 0.05). Thereafter, it gradually decreased to ∼56% of the maximum on Days 13–14 (1.27 ± 0.62) (Figure 5D).

Figure 4.

(A) Representative IK1 current tracings of control cells on Days 1, 5, and 13. Electrophysiological protocol is given in the inset. Whole-cell hyperpolarization-activated currents (left panel), Ba2+-insensitive If current (middle panel), and Ba2+-sensitive IK1 current (right panel) were shown. (B) IK1 current density at −120 mV of control cells exhibited a bi-phasic time-dependent change. (C) Current–voltage (IV) curve of control on Days 1, 5, and 13 (n = 10).

Figure 5.

(A) The MDPs or RMPs of NRVMs were plotted against IK1 at the same time point. A strong linear correlation (r = 0.89) between the bi-phasic change of MDP (or RMP) and IK1. (B) The correlation between APD50/90 and IK1 is relatively weak (r = 0.73 and 0.75, respectively). (C) Correlation was absent between firing rate and IK1 current density. (D) Change of If to IK1 ratio (|If/IK1|) at −120 mV on NRVMs during culture (n = 16), *P < 0.05.

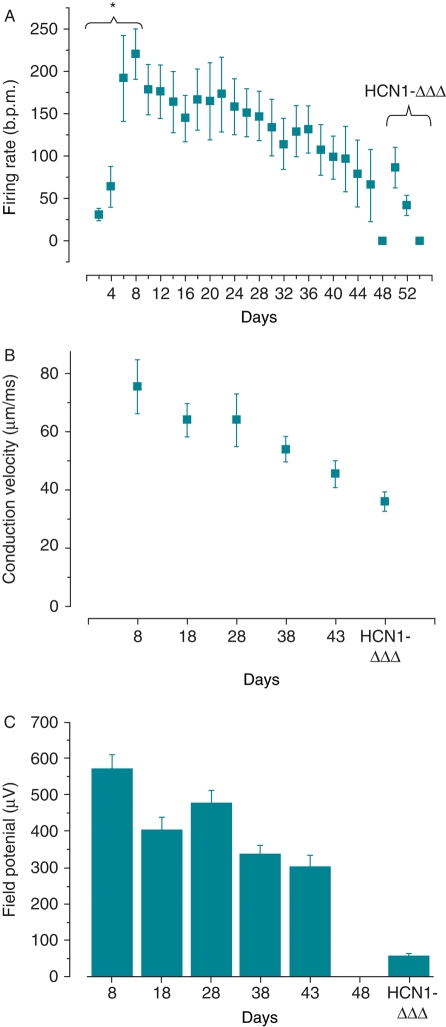

The automaticity change of monolayer culture of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

Unlike individual NRVMs (Figure 2A), synchronized spontaneous firing of monolayers disappeared as soon as after 3 days in culture. The initial firing rate of the monolayer was 36 ± 7.9 b.p.m., about twice slower than that of individual NRVMs on Day 1 as gauged by single-cell current-clamp recordings. The time to the peak firing rate was also delayed (on Day 8) compared with single cells (on around Day 4) (Figures 2A and 6A). At its fastest (i.e. Day 8), however, the firing rate of monolayers was comparable (220 ± 29.5 b.p.m.). This slowly declined to 98 ± 25.6 b.p.m. on Day 40 and became completely ceased on Day 48 (Figures 6A and 7). Transduction with Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ led to spontaneous beating with a firing rate of 86.0 ± 23.7 b.p.m.

Figure 6.

Summary of MEA recording parameters of NRVM monolayer. (A) Firing rate of control and Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ-transduced monolayer cultures. (B) Conduction velocity. (C) Amplitude of field potential (n = 6), *P < 0.05.

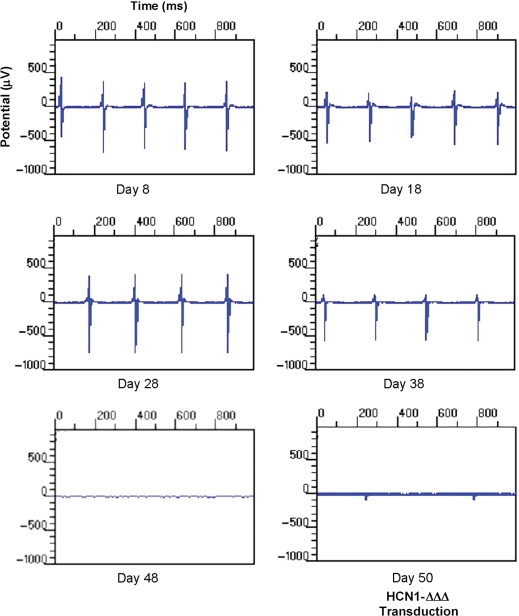

Figure 7.

Representative MEA recordings. Automaticity remained up to 48 days and could be rescued by Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ transduction.

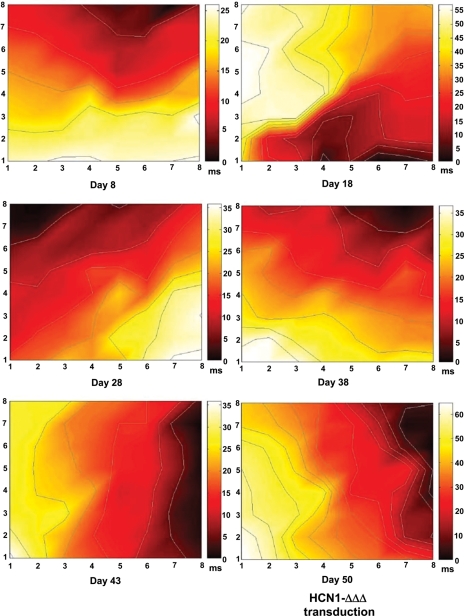

Along with the decrease in spontaneous firing, both the CV and field potential amplitude of the monolayer also time-dependently reduced to about half from 75.3 ± 9.4 µm/ms and 569.3 ± 39.2 µV on Day 8 to 36.0 ± 3.4 µm/ms and 301.4 ± 30.8 µV on Day 43, respectively (Figure 6B and C). The CV reduction was irreversible even after Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ transduction. Noticeably, after Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ transduction, the field potential amplitude reduced further and significantly to 57.9 ± 5.5 µV, about one-sixth of that on Day 43 (Figure 6C; P < 0.05). Colour-coded activation maps showed that the activation (firing) origin changed during culture (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Colour-coded activation maps from a representative culture showing the pacing origin and the decrease in CV. The scales of the maps vary from 0 to 65 ms.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated cardiac automaticity in individual cells and monolayers of NRVMs. Our key findings are as follows. For individual cells, (1) spontaneous AP displays a bi-phasic change in the firing rate with a peak appearing early on Days 3–4; (2) lack of changes of If and IK1 down-regulation cannot account for the time-dependent loss of automaticity change; (3) automaticity can be conferred on silenced single cells or monolayer upon gene transfer of HCN1-ΔΔΔ. As for monolayers, (4) spontaneous AP likewise displays a bi-phasic change in the firing rate but this automaticity sustains for about a month longer than individual cells with comparable maximal firing rates; (5) AP firing rate, CV, and field potential similarly exhibit a trend of gradual decrease in magnitude over time; (6) and gene transfer of HCN1-ΔΔΔ in quiescent cultures partially restores the spontaneous beating.

Several gene-based approaches have been explored to confer upon non-pacing CMs the ability to intrinsically fire APs like genuine nodal pacemaker cells. Protein engineering has been recently applied as an alternative to overexpress WT HCN1 or 2 channels alone in normally quiescent ventricular CMs and cause cellular rhythmic oscillations.4,17 Mathematically, AP was simulated using a computational model to understand the contribution of If to proper pacing.18 Pacemakers were then engineered into non-pacing CMs via somatic gene transfer of HCN1-ΔΔΔ both in vitro and in vivo.21 In a sick-sinus syndrome porcine model, physiological heart rhythms can be restored via focal transduction of the left atrium via Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ injection (as opposed to the right atrium where the native SA node is anatomically located). Mechanistically, we have reported that a fine balance between If and IK1 is key to successful automaticity induction in both atrial and ventricular CMs.17,19 In NRVMs, Qu et al.4 and Er et al.5 have demonstrated its critical role in SAP generation and pacing modulation. In the present study, no measurable If could be recorded at physiological [K+]o (5 mM). Furthermore, its current density at [K+]o of 25 mM and activation relation remained unchanged during the time course of our experiments, in sharp contrast to the bi-phasic change of SAP. This finding suggested that If alone is not responsible for the time-dependent loss of automaticity of NRVMs in culture. However, this could be rescued by forced expression of If via Ad-mediated gene transfer in both silenced individual and monolayer NRVMs, although the firing rates were slower.

Compared with If, the relationships between IK1 and AP have been much better defined. In addition to its contribution to Phase 3 repolarization, IK1 stabilizes a negative RMP (−80 mV) and suppresses any latent spontaneous electrical activity.24 This was demonstrated by Hirano et al.25 and Imoto et al.26 in 1988 that blockade of IK1 by Ba2+ induces automaticity in isolated guinea pig ventricular myocytes. Miake et al.10 confirmed these findings using a genetic approach to dominant-negatively suppress Kir2-encoded IK1 and thereby unleash the latent pacemaker activity of normally silent ventricular myocytes. On the basis of these findings, the absence of the strongly polarizing IK1, rather than the presence of If, has been proposed as a key factor for pacing.9 As presented in this study, IK1 time-dependently down-regulates in a manner reciprocal to the slowing of the firing rates, although If remained essentially unchanged. These results are in complete accordance with the view that effective induction and modulation of cardiac automaticity involves components other than IK1.

In this study, the automaticity of individual NRVMs in culture could only maintain up to 2 weeks. However, that of monolayer culture recorded by MEA lasted up to 48 days. Such differences in the electrical properties of the monolayer culture from those of single cells can be attributed to cell–cell coupling. Colour-coded activation maps indicate that one or multiple pacemaking sites can arise during long-term culture (Figure 8). Of note, the presence of a few firing cells may suffice to lead to firing of the entire monolayer via electrical coupling through gap junctions. Consistently, Yasui et al.27 have demonstrated that gap junction channels are important for maintaining the electrophysiological activities of cultured NRVMs. Ad-HCN1-ΔΔΔ-induced automaticity in silenced NRVMs is associated with a reduction of CV. Some possible underlying mechanisms include down-regulation of connexin-mediated gap junction for cell–cell coupling, alterations of voltage-gated Na+ channel for rapid conduction of APs, etc. Taken together, our results implicate that further development of bio-artificial pacemakers should have conduction properties taken into consideration, an area that has not been extensively explored.

In summary, we have employed long-term culturing of NRVMs as an in vitro model for investigating the role of IK1 and If in cardiac automaticity at the singe- and multicellular levels. On the basis of the present and other results, we conclude that while the combination of IK1 and If primes CMs for bio-artificial pacing (by determining the threshold), If functions as a membrane potential oscillator to determine the basal firing frequency. For multicellular preparations, the engineering of automaticity needs to have conduction taken into consideration.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL72857 to R.A.L.), the Hong Kong Research Grant Council General Research Fund (HKU 763306M, HKU 7747/08M and HKU 776908M to C.W.S., H.F.T., and R.A.L.), and the CC Wong Stem Cell Fund (to H.F.T. and R.A.L.).

References

- 1.Harary I, Farley B. In vitro studies on single beating rat heart cells. I. Growth and organization. Exp Cell Res. 1963;29:451–65. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(63)80008-7. doi:10.1016/S0014-4827(63)80008-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harary I, Farley B. In vitro studies on single beating rat heart cells. II. Intercellular communication. Exp Cell Res. 1963;29:466–74. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(63)80009-9. doi:10.1016/S0014-4827(63)80009-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tse HF, Xue T, Lau CP, Siu CW, Wang K, Zhang QY, et al. Bioartificial sinus node constructed via in vivo gene transfer of an engineered pacemaker HCN channel reduces the dependence on electronic pacemaker in a sick-sinus syndrome model. Circulation. 2006;114:1000–11. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615385. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.615385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qu J, Barbuti A, Protas L, Santoro B, Cohen IS, Robinson RB. HCN2 overexpression in newborn and adult ventricular myocytes: distinct effects on gating and excitability. Circ Res. 2001;89:E8–E14. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.094395. doi:10.1161/hh1301.094395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Er F, Larbig R, Ludwig A, Biel M, Hofmann F, Beuckelmann DJ, et al. Dominant-negative suppression of HCN channels markedly reduces the native pacemaker current I(f) and undermines spontaneous beating of neonatal cardiomyocytes. Circulation. 2003;107:485–9. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000045672.32920.cb. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000045672.32920.CB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baruscotti M, Difrancesco D. Pacemaker channels. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1015:111–21. doi: 10.1196/annals.1302.009. doi:10.1196/annals.1302.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satoh H. Sino-atrial nodal cells of mammalian hearts: ionic currents and gene expression of pacemaker ionic channels. J Smooth Muscle Res. 2003;39:175–93. doi: 10.1540/jsmr.39.175. doi:10.1540/jsmr.39.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Irisawa H, Brown HF, Giles W. Cardiac pacemaking in the sinoatrial node. Physiol Rev. 1993;73:197–227. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1993.73.1.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marban E, Cho HC. Creation of a biological pacemaker by gene- or cell-based approaches. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2007;45:133–44. doi: 10.1007/s11517-007-0165-2. doi:10.1007/s11517-007-0165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miake J, Marban E, Nuss HB. Biological pacemaker created by gene transfer. Nature. 2002;419:132–3. doi: 10.1038/419132b. doi:10.1038/419132b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haddad GE, Petrich ER, Zumino AP, Schanne OF. Background K+ currents and response to metabolic inhibition during early development in rat cardiocytes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1997;177:159–68. doi: 10.1023/a:1006854427788. doi:10.1023/A:1006854427788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Masuda H, Sperelakis N. Inwardly rectifying potassium current in rat fetal and neonatal ventricular cardiomyocytes. Am J Physiol. 1993;265:H1107–11. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.4.H1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahler GM. Developmental increases in the inwardly rectifying potassium current of rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:C1266–72. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.262.5.C1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilborn MJ, Fedida D. A study of the developmental changes in outward currents of rat ventricular myocytes. J Physiol. 1990;430:37–60. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1990.sp018280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie LH, Takano M, Noma A. Development of inwardly rectifying K+ channel family in rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H1741–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sekar RB, Kizana E, Smith RR, Barth AS, Zhang Y, Marban E, et al. Lentiviral vector-mediated expression of GFP or Kir2.1 alters the electrophysiology of neonatal rat ventricular myocytes without inducing cytotoxicity. Am J Physiol. 2007;293:H2757–70. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00477.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue T, Siu CW, Lieu DK, Lau CP, Tse HF, Li RA. Mechanistic role of I(f) revealed by induction of ventricular automaticity by somatic gene transfer of gating-engineered pacemaker (HCN) channels. Circulation. 2007;115:1839–50. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659391. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.659391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Azene EM, Xue T, Marban E, Tomaselli GF, Li RA. Non-equilibrium behavior of HCN channels: insights into the role of HCN channels in native and engineered pacemakers. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;67:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.006. doi:10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lieu DK, Chan YC, Lau CP, Tse HF, Siu CW, Li RA. Overexpression of HCN-encoded pacemaker current silences bioartificial pacemakers. Heart Rhythm. 2008;5:1310–7. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.010. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2008.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan YC, Siu CW, Lau YM, Lau CP, Li RA, Tse HF. Synergistic effects of inward rectifier (IK1) and pacemaker (If) currents on the induction of bioengineered cardiac automaticity. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8167.2009.01475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsang SY, Lesso H, Li RA. Dissecting the structural and functional roles of the S3–S4 linker of pacemaker (hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-modulated) channels by systematic length alterations. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43752–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408747200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408747200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rae J, Cooper K, Gates P, Watsky M. Low access resistance perforated patch recordings using amphotericin B. J Neurosci Methods. 1991;37:15–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-0270(91)90017-t. doi:10.1016/0165-0270(91)90017-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meiry G, Reisner Y, Feld Y, Goldberg S, Rosen M, Ziv N, et al. Evolution of action potential propagation and repolarization in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2001;12:1269–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.01269.x. doi:10.1046/j.1540-8167.2001.01269.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopatin AN, Nichols CG. Inward rectifiers in the heart: an update on I(K1) J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:625–38. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1344. doi:10.1006/jmcc.2001.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirano Y, Hiraoka M. Barium-induced automatic activity in isolated ventricular myocytes from guinea-pig hearts. J Physiol. 1988;395:455–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp016929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Imoto Y, Ehara T, Matsuura H. Voltage- and time-dependent block of iK1 underlying Ba2+-induced ventricular automaticity. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:H325–33. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1987.252.2.H325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasui K, Kada K, Hojo M, Lee JK, Kamiya K, Toyama J, et al. Cell-to-cell interaction prevents cell death in cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;48:68–76. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00145-0. doi:10.1016/S0008-6363(00)00145-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]