Abstract

In Sterkiella nova, α and β telomere proteins bind cooperatively with single-stranded DNA to form a ternary α·β·DNA complex. Association of telomere protein subunits is DNA-dependent, and α-β association enhances DNA affinity. To further understand the molecular basis for binding cooperativity, we characterized several possible stepwise assembly pathways using isothermal titration calorimetry. In one path, α and DNA first form a stable α·DNA complex followed by addition of β in a second step. Binding energy accumulates with nearly equal free energy of association for each of these steps. Heat capacity is nonetheless dramatically different with ΔCp = −305 ± 3 cal mol−1 K−1 for α binding with DNA and ΔCp = −2010 ± 20 cal mol−1 K−1 for addition of β to complete the α·β·DNA complex. By examining alternate routes including titration of single-stranded DNA with a preformed α·β complex, a significant portion of binding energy and heat capacity could be assigned to structural reorganization involving protein-protein interactions and repositioning of the DNA. Structural reorganization probably affords a mechanism to regulate high affinity binding of telomere single-stranded DNA with important implications for telomere biology. Regulation of telomere complex dissociation is thought to involve post-translational modifications in the lysine-rich C-terminal portion of β. We observed no difference in binding energetics or crystal structure when comparing complexes prepared with full-length β or a C-terminally truncated form, supporting interesting parallels between the intrinsically disordered regions of histones and this portion of β.

Telomere nucleoprotein complexes serve critical functions in eukaryotic cells, protecting the ends of chromosomes from degradation, recombination, and end-to-end fusion events (1–3). A conserved feature of telomere DNA is a single-stranded 3′-terminal extension (4–7) that acts as the primer for synthesis of telomere DNA repeats catalyzed by the ribonucleoprotein enzyme telomerase (8). By compensating for DNA loss accompanying lagging strand DNA synthesis, telomerase-mediated extension of telomere DNA ensures that genetic information in chromosomes is completely replicated with each cell division.

Telomeres found in the macronuclei of Sterkiella nova (Oxytricha nova formerly) are relatively simple and well defined yet possess higher levels of structural organization and therefore represent an important model system for understanding the structures of telomere ends. Telomere DNA in S. nova consists of 20 base pairs of double-strand DNA followed by 16 nucleotides of 3′-terminal single-stranded DNA of sequence d(TTTTGGGGTTTTGGGG) (4). The single-stranded DNA forms a tenacious salt-resistant complex with two protein subunits, a 56-kDa protein called α and a 41-kDa protein called β (9–12). The α protein contains two structurally and functionally separable domains, a 35-kDa N-terminal DNA-binding domain and a 21-kDa C-terminal domain necessary for protein-protein association (13). The 41-kDa β protein is readily processed by proteolysis to yield a 28-kDa C-terminally truncated form, β28-kDa, that retains many if not all of the single-stranded DNA-binding properties of full-length β (13). The lysine-rich, protease-sensitive, C-terminal portion of β is unstructured (14) and contains sites for phosphorylation that may be important for regulation of α·β·DNA complex disassembly (15, 16).

A stretch of 65 amino acid residues contained within the protease-resistant 28-kDa core of β is essential for protein-protein interactions (17). These residues form an α helix and extended peptide loop that contribute a substantial portion of the α-β protein-protein interface as seen in a single-stranded DNA co-crystal structure (18). The disposition of this peptide loop contributed by β indicates that when β is free in solution these residues are either unstructured or adopt an alternate conformation potentially stabilized by intramolecular interactions with the globular portion of β. In either case, these residues probably undergo substantial reorganization coupled with DNA complex assembly.

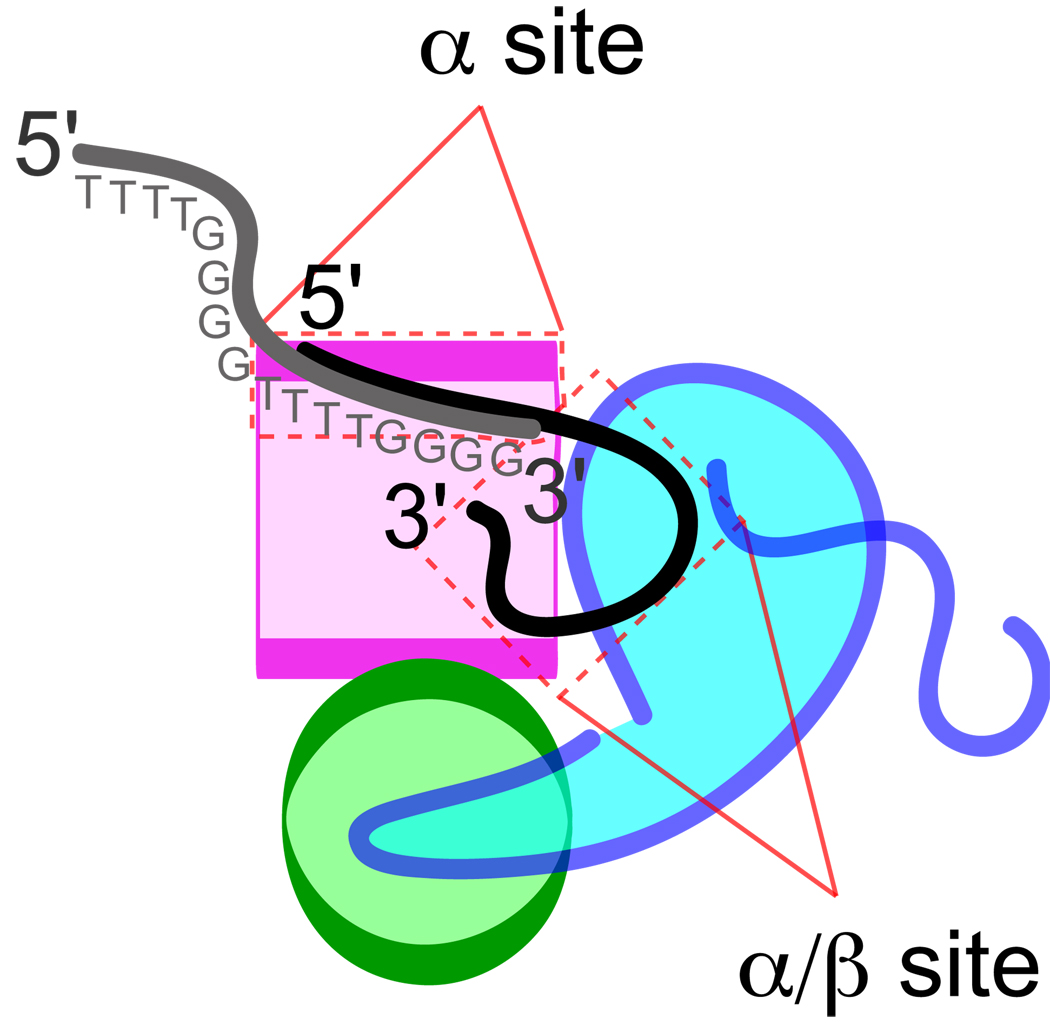

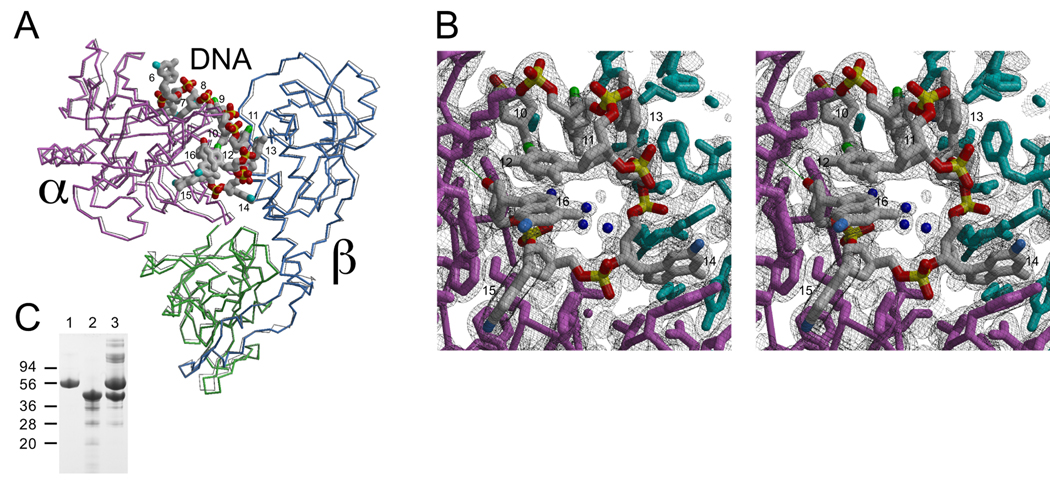

Single-stranded DNA in the α·β28-kDa·DNA crystal structure occupies two binding sites, a site constructed from residues of α called the α-site and a site at the α-β interface constructed from residues of α and β called the α/β-site (see Fig. 1). The DNA is oriented in the α·β28-kDa·DNA complex so that a 3′-terminal telomere repeat is positioned in the α/β-site and a partial 3′-distal repeat is located in the α-site. In other single-stranded DNA co-crystal structures lacking β, a partial 3′-terminal DNA repeat occupies the α-site (19, 20). Comparison of these crystal forms as well as results from biochemical studies in solution (11) leads to the conclusion that telomere DNA is repositioned upon association of β, resulting in a net movement of the 3′-terminal telomere repeat from the α-site to the α/β-site.

FIGURE 1. DNA-binding sites.

Telomere TTTTGGGG repeats interact with two distinct sites, an α-site located on the N-terminal domain of α (magenta square), and an α/β-site constructed from residues of both α and β (blue shape). Given limiting amounts of α and in the absence of β, telomere DNA prefers to bind with its 3′-terminal TTTTGGGG occupying the α-site. When β is available, a 3′-distal TTTTGGGG repeat occupies the α-site, and the 3′-terminal TTTTGGGG adopts a looped structure so as to fit into the α/β-site.

The S. nova telomere system affords a unique opportunity to explore how binding events can alter macromolecular complex structure with consequences important for biological function. Association with β substantially increases DNA complex stability (13, 17), which is probably important for DNA end protection. Additionally, by linking complex stability, structural reorganization within β, and DNA position, the system becomes potentially responsive to cell-cycle dependent events that regulate telomere end structure and permit access of the 3′-hydroxyl-bearing primer to telomerase.

To further understand binding cooperativity and the nature of structural reorganization encountered during telomere complex assembly, we characterized several possible stepwise assembly pathways using ITC2 and determined the crystal structure of a complex constructed with d(GGGTTTTGGGG) telomere-derived single-stranded DNA, α, and the full-length version of β. Our binding data reveal a large and negative heat capacity change consistent with dramatic folding events coupled to binding. Structural reorganization probably represents the driving force behind an allosteric switch that modulates DNA binding affinity and, importantly, DNA position. We propose that when this switch is reversed upon dissociation of β, the resulting α·DNA complex keeps DNA positioned with 3′-terminal nucleotides exposed and ready for productive association with telomerase. Comparison of the full-length α·β·DNA co-crystal structure with that previously obtained with the protease-resistant core domain of β showed that the protein-DNA interface is extremely well preserved. No additional electron density was apparent, confirming that the C-terminal tail of β is unstructured and suggesting that regulation via post-translational modification of these residues may have interesting parallels with regulation of chromatin structure via post-translational modification of histone tails.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Preparation of Protein and Single-stranded DNA

α (495 aa) the N-terminal domain of α (aa 1–326, α-N), β (385 aa) and the protease-resistant core of β (aa 1–260, β28-kDa) proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified to homogeneity through ammonium sulfate fractionation, ion exchange, and size exclusion chromatography as described previously (17, 18). Particular care was needed to prepare β in its intact full-length form. Precautions against proteolytic cleavage included keeping the protein preparation on ice and completing the purification procedure and experiment in as short a time as practical, typically within 1 or 2 days for ITC experiments and within 2 weeks for crystal growth. Analysis by SDS-PAGE confirmed that when handled with these precautions, β remains >95% intact for at least 4 weeks. DNA oligonucleotides were purified by reverse phase high pressure liquid chromatography in both trityl-protected and deprotected forms as previously described (21). The α·DNA complex was prepared by mixing molar equivalents of α and DNA, followed by size exclusion chromatography. Prior to titration experiments, solutions of each binding component were dialyzed against a common reservoir containing 0.15 m lithium chloride and 0.05 m Tris, pH 7.5.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Titrations were carried out with use of a Microcal VP-ITC instrument. Previous ITC studies of single-stranded telomere DNA demonstrated that high quality data could be obtained most consistently over a broad range of temperatures if the DNA component was included within the sample cell (21), and this constraint directed our choice of titrant and sample cell components. Typically, DNA or DNA-protein complex was diluted to 30 µm, degassed, and placed in the sample cell. Protein was diluted to 330 µm, degassed, and placed in the titration syringe. Higher concentrations of both titrant ([β] = 550 µm) and sample cell component ([α] = 50 µm) were employed in the case of protein-protein association reactions. The sample was stirred at a rate of 300 rpm. An initial 2- or 3-µl injection was followed by several 5- or 8-µl injections. Peaks in power versus time plots were integrated and normalized to yield molar enthalpies for each injection. Except for binding reactions noted below, the resulting binding isotherms were analyzed with the “one-site” model provided with the instrument to obtain binding enthalpy (ΔH), association constant (KA) and binding stoichiometry (n). Binding free energy (ΔG) was calculated as – RT ln(KA), where R = 1.987 cal mol−1 K−1 is the ideal gas law constant, and T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. Binding entropy (ΔS) was derived by rearrangement of the familiar Gibbs free energy equation, ΔG = ΔH – TΔS. To obtain thermodynamic parameters describing the temperature dependence of binding enthalpy and entropy, ΔH versus T plots were fit to the equation ΔH = ΔCp(T – TΔH=0), where ΔCp is the heat capacity change of binding and TΔH=0 is a reference temperature at which ΔH = 0.

Titrations of α into (DNA + β) were analyzed with a program written in C (by M. P. H.) that allowed use of a ternary (m−2) association constant in place of the binary association constant (m−1) employed with the “one-site” model. Heat contributed by the displaced volume was computed as described in the instrument user’s manual. Titrations of α·β into solutions of single-stranded DNA were treated with a more complete binding model so as to take into account heat evolved or absorbed as a consequence of multiple potential reactions, including dissociation of the α·β complex upon dilution into the sample cell and protein-protein association coupled with DNA binding. For this analysis, numerical methods encoded in a C language program (by M. P. H.) determined the concentrations of unbound species αfree, βfree, and DNAfree satisfying Equation 1–Equation 3.

| (Eq. 1) |

| (Eq. 2) |

| (Eq. 3) |

In solving this system of equations, substitutions indicated in Equation 4 and Equation 5 replaced α·β and α·β·DNA with expressions involving only the unknown quantities αfree, βfree, and DNAfree and the parameterized association constants KA-3.1 and KA-3.2.

| (Eq. 4) |

| (Eq. 5) |

Additional parameters, ΔH3.1 and ΔH3.2, described the binding enthalpy associated with α·β and α·β·DNA, respectively. The total heat expected upon each injection was then computed by keeping track of changes in the concentration of α·β and α·β·DNA both for the volume injected and the working volume of the sample cell. Parameters KA-3.1 and ΔH3.1 were defined by data measured during titrations of β into α and were treated as constants in these analyses. The remaining thermodynamic parameters, KA-3.2 and ΔH3.2, were adjusted so as to minimize the sum of squared residuals. Uncertainties in these parameters were estimated by a Monte-Carlo bootstrap method (22).

Crystallization

The α·β·DNA complex was prepared at a concentration of 150–200 µm by mixing stoichiometric amounts of d(GGGTTTTGGGG) and α followed by adding 1.2-fold excess β. To provide an opportunity for interactions with G-quartet DNA, d(GGGGTTTTGGGG) was included in all crystal trials. Crystals were obtained with the hanging drop vapor diffusion method by mixing equal volumes of reservoir and complex-containing solutions and allowing the resulting 4–6-µl reactions to equilibrate against 1 ml of reservoir at 4 °C. The reservoir contained 21% (w/v) polyethylene glycol 4000, 10% (v/v) ethylene glycol, 1.25–1.625 m sodium chloride, 40 mm MES pH 5–6, 2 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.02% sodium azide. Crystals with a hexagonal rod-shaped morphology appeared within 1 or 2 days and grew to a final size of about 250 × 250 × 500 µm over the period of several days. Crystals were briefly soaked in a harvesting solution containing 21% polyethylene glycol 4000, 20% ethylene glycol, 1 m sodium chloride, 40 mm MES, 2 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.02% sodium azide prior to freezing in liquid propane at 100 K.

X-ray Diffraction and Structure Refinement

X-ray diffraction data to the 1.91 Å resolution limit were collected in oscillation mode using synchrotron radiation at the SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source. To minimize the effects of x-ray induced damage, the crystal was repositioned at intervals corresponding with about 1200 s of x-ray exposure. Data were integrated, scaled, and merged using DENZO and SCALEPACK as implemented with the HKL2000 user interface (23). The structure was determined by rigid body positioning of the α·β28-kDa·DNA structure (Protein Data Bank code 1JB7) followed by iterative cycles of simulated annealing, geometry-restrained positional refinement, and restrained isotropic temperature factor refinement using maximum likelihood target functions implement in CNS (24). After each round of refinement, σ-A weighted 3|Fo| – 2|Fc|, 2|Fo| – |Fc|, and |Fo| – |Fc| electron density maps guided manual structural adjustments accomplished using the model building program O (25). Rfree values were computed with the same set of structure factors reserved for cross-validation of the previously determined structure, Protein Data Bank code 1JB7.

RESULTS

Experimental Design

Telomere α and β proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified in their intact and untagged forms. Previous to this work, much of the biochemistry and x-ray structure determination employed a C-terminally truncated form of the telomere β protein (260 amino acids, 28 kDa), since β28-kDa is more readily expressed in E. coli and purified compared with β in its full-length form (385 amino acids, 41 kDa). In this work, we wished to compare β28-kDa with β in terms of their binding properties and co-complex structures and therefore purified both proteins. SDS-PAGE verified that the full-length β protein remained intact over the course of each experiment, including the several days needed to prepare telomere α·β·DNA co-complex crystals.

With its G-rich repeats, telomere single-stranded DNA is prone to form G-quartet stabilized structures which are kinetically inert and incompatible with binding telomere proteins (26). To minimize the risk of trapping the DNA in such structures, the binding reaction buffer included lithium chloride, reasonable precautions were taken to exclude sodium and potassium ions, and DNA-binding reactions used a shortened 11-nt fragment (underlined) derived from the 3′-terminal portion of d(~TTTTGGGGTTTTGGGG) found at the ends of mature telomeres in S. nova. Use of a shorter 11-nt DNA also prevented α2·DNA complexes observed previously for binding reactions involving the full-length 16-nt DNA and the N-terminal domain of α (21), yet allowed for formation of a complete ternary α·β·DNA complex as verified by x-ray crystallography.

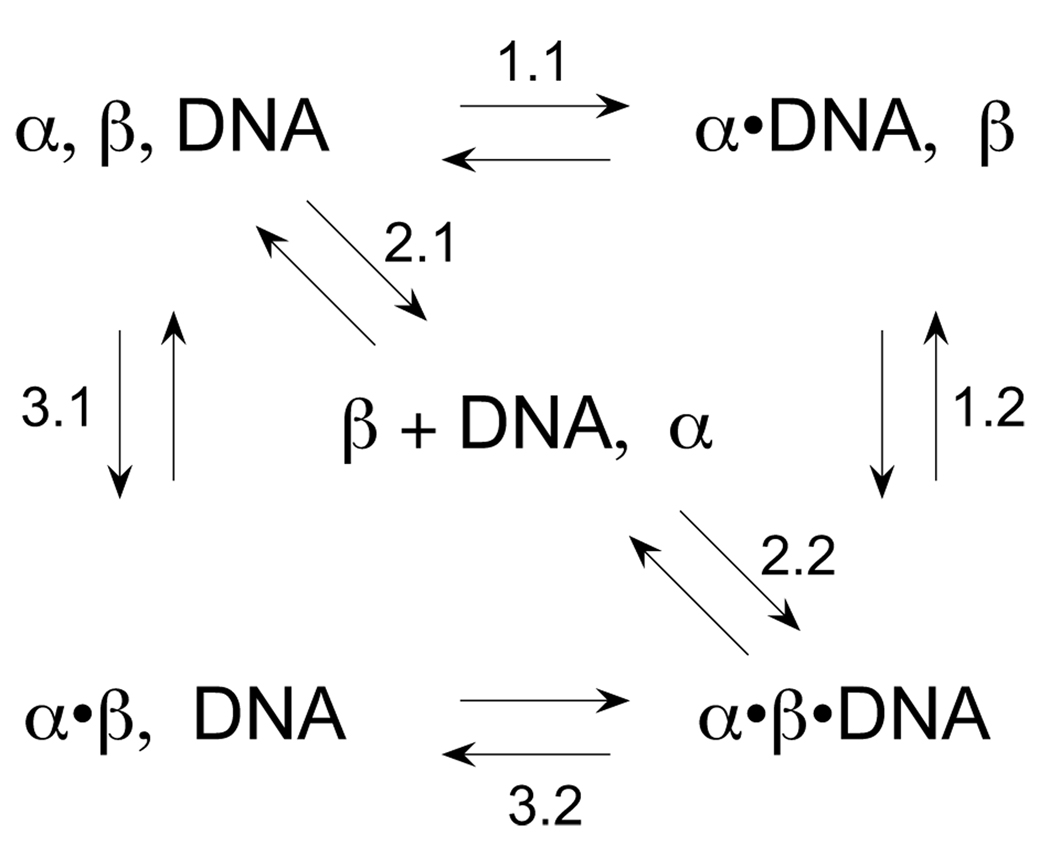

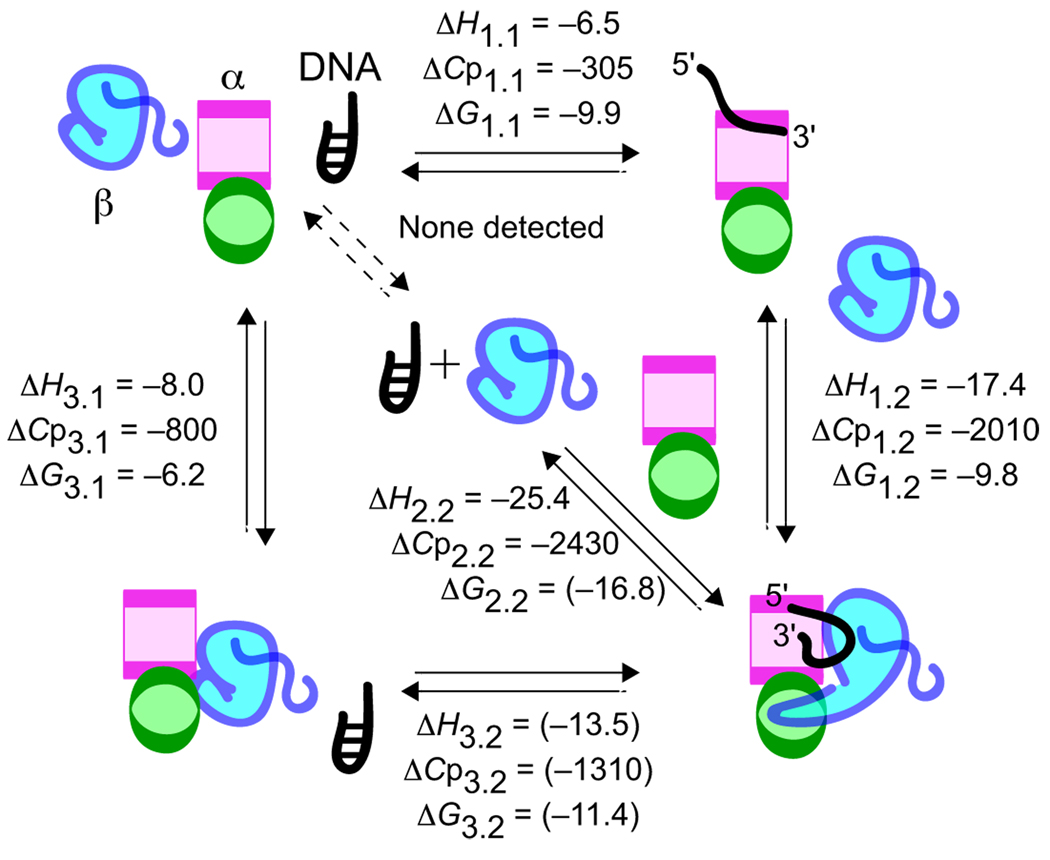

Formation of the α·β·DNA ternary complex may proceed through several pathways as illustrated in Scheme 1. In one pathway, α and DNA first form a stable α·DNA complex (step 1.1 of Scheme 1), followed by addition of β in a second reaction (step 1.2). In a second pathway, β is mixed with DNA before adding α (step 2.2). In a third pathway, α-β association (step 3.1) precedes DNA association (step 3.2). These binding reactions were each evaluated using ITC. Representative ITC data are presented in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3. Table 1 reports thermodynamic parameters including binding enthalpy (ΔH), entropy (ΔS), free energy (ΔG), stoichiometry (n), and heat capacity (ΔCp).

SCHEME 1. Formation of the α·β·DNA ternary complex.

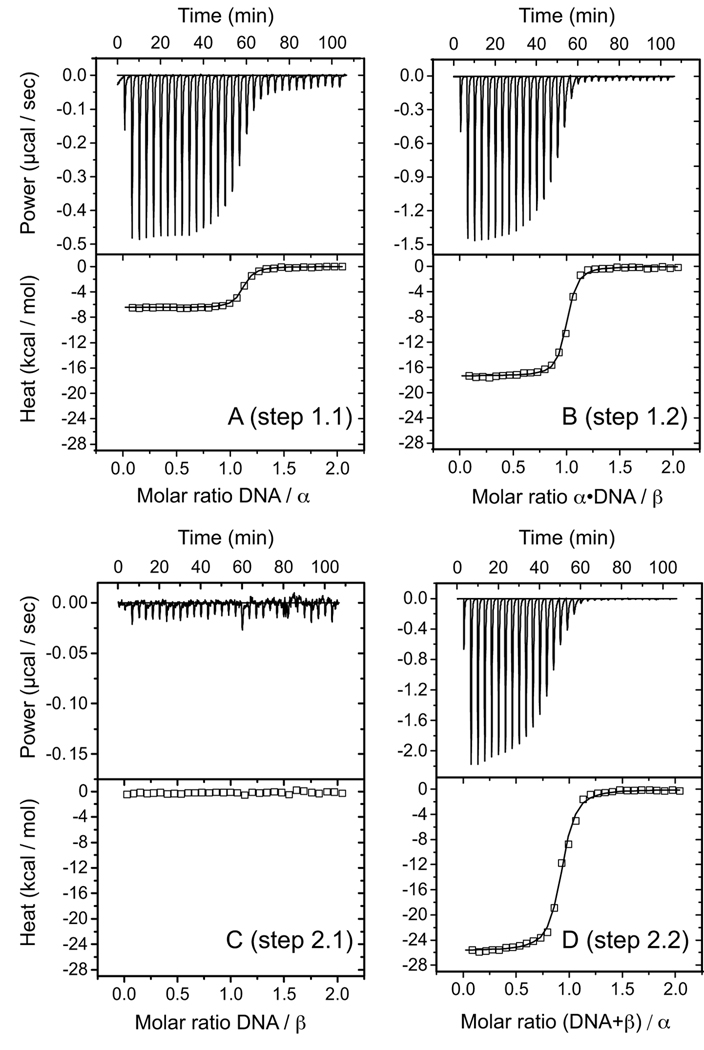

FIGURE 2. ITC for pathways 1 and 2 (DNA precedes protein-protein association).

Representative thermograms (upper half of each panel) and binding isotherms (bottom half) show data obtained at 25 °C. A, Titration of DNA with α (step 1.1 of Scheme 1). B, titration of α·DNA with β (step 1.2 of Scheme 1). C, titration of DNA with β (step 2.1 of Scheme 1). In this step, heat corresponds with heat of mixing (i.e. there is no detectable binding). D, titration of β + DNA with α (step 2.2 of Scheme 1). Model curves represent the results of nonlinear least-squares fitting of measurements.

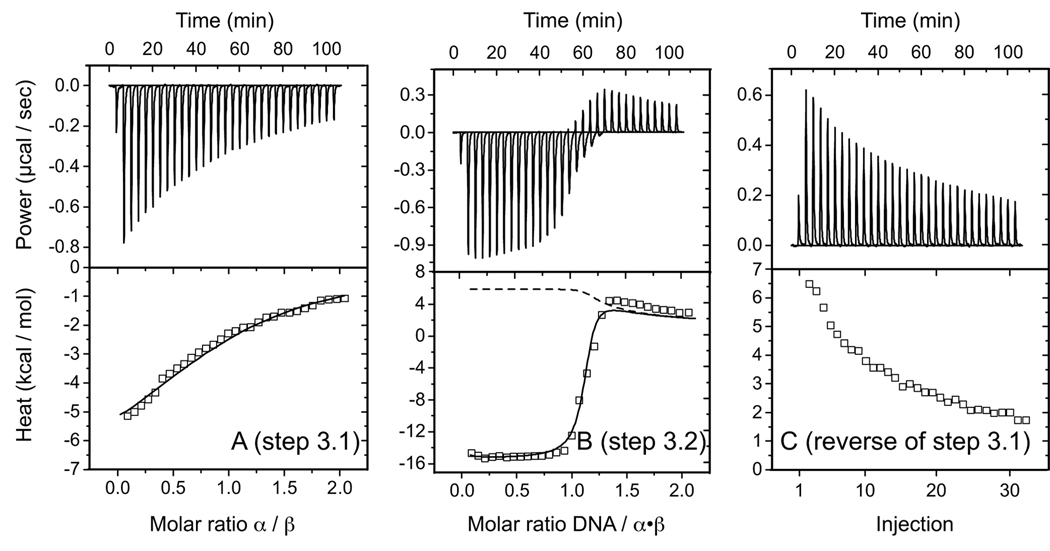

FIGURE 3. ITC for pathway 3 (DNA follows protein-protein association).

Representative data for binding reactions at 25 °C are shown. A, titration of α with β (step 3.1 of Scheme 1). B, titration of DNA with α·β (step 3.2 of Scheme 1). C, injection of α·β into buffer (reverse of step 3.1). Model curves represent the results of nonlinear least-squares fitting of measurements with a system of equilibria that includes the possibility for α·β dissociation upon dilution into the sample cell (dashed curve) and α·β association coupled with DNA binding (see “Experimental Procedures”).

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for telomere complex assembly

| Reactiona | T | ΔH | ΔS | ΔG | nb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| °C | kcal mol−1 | cal mol−1 K−1 | kcal mol−1 | ||

| 1.1. α + DNA | 10 | −1.91 ± 0.03 | 27.7 ± 0.6 | −9.7 ± 0.2 | 1.06 (2) |

| ΔCp = −305 ± 3 cal mol−1 K−1 | 20 | −4.84 ± 0.02 | 17.1 ± 0.3 | −9.84 ± 0.08 | 1.08 (1) |

| TΔH=0 = 277.0 ± 0.2 K | 25 | −6.46 ± 0.02 | 11.5 ± 0.1 | −9.89 ± 0.03 | 1.09 (0) |

| 30 | −8.01 ± 0.02 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | −9.79 ± 0.04 | 1.11 (0) | |

| 37 | −10.10 ± 0.04 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | −10.1 ± 0.1 | 1.07 (1) | |

| 1.2. β + α·DNA | 10 | 12.3 ± 0.1 | 73.9 ± 0.3 | −8.6 ± 0.1 | 0.90 (1) |

| ΔCp = −2010 ± 20 cal mol−1 K−1 | 20 | −7.37 ± 0.05 | 8.3 ± 0.6 | −9.8 ± 0.2 | 0.98 (1) |

| TΔH=0 = 289.4 ± 0.1 K | 25 | −17.4 ± 0.1 | −25.4 ± 0.9 | −9.8 ± 0.2 | 0.98 (1) |

| 30 | −28.0 ± 0.3 | −60 ± 1 | −9.8 ± 0.2 | 1.00 (2) | |

| 1.2. β28-kDa + α·DNA | 10 | 11.76 ± 0.07 | 75.1 ± 0.3 | −9.5 ± 0.1 | 0.88 (1) |

| ΔCp = −1930 ± 10 cal mol−1 K−1 | 20 | −7.40 ± 0.08 | 8.3 ± 0.9 | −9.8 ± 0.2 | 0.91 (1) |

| TΔH=0 = 289.3 ± 0.1 K | 25 | −16.97 ± 0.06 | −23.3 ± 0.5 | −10.0 ± 0.1 | 0.93 (1) |

| 30 | −27.0 ± 0.1 | −55.3 ± 0.8 | −10.2 ± 0.1 | 0.89 (1) | |

| 2.2. α + (β + DNA) | 10 | 10.65 ± 0.04 | 97 ± 1 | −16.9 ± 0.3 | 0.87 (1) |

| ΔCp = −2430 ± 40 cal mol−1 K−1 | 20 | −12.6 ± 0.1 | 13 ± 1 | −16.5 ± 0.3 | 0.94 (2) |

| TΔH=0 = 287.7 ± 0.2 K | 25 | −25.4 ± 0.1 | −29 ± 1 | −16.8 ± 0.2 | 0.92 (1) |

| 30 | −38.1 ± 0.2 | −69 ± 1 | −17.1 ± 0.2 | 0.91 (2) | |

| 3.1. β + α | 5 | 8 ± 1 | 49 ± 3 | −5.4 ± 0.1 | 1.36 (9) |

| ΔCp = −800 ± 10 cal mol−1 K−1 | 20 | −3.7 ± 0.3 | 10 ± 1 | −6.6 ± 0.1 | 1.01 (5) |

| TΔH=0 = 288.5 ± 0.1 K | 25 | −8 ± 1 | −6 ± 3 | −6.2 ± 0.1 | 1.00 (8) |

| 30 | −12 ± 2 | −19 ± 6 | −5.9 ± 0.1 | 1.10 (13) | |

| 3.1. β28-kDa + α | 5 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 34 ± 2 | −5.8 ± 0.1 | 0.99 (8) |

| ΔCp = −670 ± 20 cal mol−1 K−1 | 20 | −7 ± 1 | −3 ± 3 | −6.0 ± 0.1 | 0.93 (9) |

| TΔH=0 = 283.3 ± 0.4 K | 25 | −10 ± 1 | −13 ± 4 | −6.2 ± 0.1 | 1.01 (8) |

| 30 | −13 ± 2 | −24 ± 7 | −5.7 ± 0.1 | 0.97 (12) | |

| 3.2. α·β + DNA | 5 | 11.7 ± 0.4 | 76 ± 1 | −9.5 ± 0.1 | 0.78 (1) |

| ΔCp = −1310 ± 60 cal mol−1 K−1 | 20 | −6.5 ± 0.1 | 17 ± 2 | −11.5 ± 0.5 | 1.00 (1) |

| TΔH=0 = 287.4 ± 0.5 K | 25 | −13.5 ± 0.2 | −7 ± 3 | −11.4 ± 0.6 | 1.05 (2) |

| 30 | −21.6 ± 0.3 | −31 ± 3 | −12.1 ± 0.5 | 1.09 (2) |

Reactions are specified as titrant + cell component. For example, α + DNA (step 1.1) indicates that α in the titration syringe was injected into a solution of DNA in the sample cell.

Uncertainty for the least significant digit of n is reported in parenthesis.

Bimolecular binding equilibria, such as α + DNA → α·DNA (step 1.1 of Scheme 1) or α + β → α·β (step 3.1), were appropriately evaluated with the “one-site” binding model. Due to the exceptional stability of the α·DNA complex, the reaction β + α·DNA (step 1.2) could also be treated with the “one-site” model; however, such was not the case for α + (β + DNA) (step 2.2) or α·β + DNA (step 3.2). Analysis of these binding steps was therefore accomplished with more complete mathematical models appropriate for each case (see “Experimental Procedures”).

ITC for First Step Binding Reactions

The first step in ternary α·β·DNA complex formation consists of association of DNA with either α or β telomere proteins or by way of protein-protein association (steps 1.1, 2.1, and 3.1 in Scheme 1). Representative ITC data obtained at 25 °C for these binding reactions are shown in Fig. 2, A and C, and Fig. 3A. Association of α with d(GGGTTTTGGGG) DNA (step 1.1 in Table 1, Fig. 2A) was characterized by favorable enthalpy and entropy terms (ΔH1.1 < 0, ΔS1.1 > 0) at each temperature tested, making the resulting α·DNA complex very stable with ΔG1.1 = −9.89 ± 0.03 kcal/mol at 25 °C. Highly similar binding behavior with nearly identical thermodynamic parameters was observed for the N-terminal DNA-binding domain of α binding with the same 11-nt DNA (21), confirming that the N-terminal domain of α is sufficient for DNA binding and indicating that the C-terminal protein-protein association domain of α does not participate significantly in this initial encounter with DNA.

Titration of DNA with β at 25 °C showed no measurable interaction (step 2.1 in Scheme 1, Fig. 2C). Similar results were obtained at 30 °C, confirming the widely held belief that productive β-DNA interactions are α-dependent (11, 13). Protein-protein association (step 3.1 in Table 1, Fig. 3A) was characterized by ΔG3.1 = −6.2 ± 0.1 kcal/mol with overall favorable enthalpy (ΔH3.1 > 0) and unfavorable entropy (ΔS3.1 < 0) terms at 25 °C. The α·β species is therefore significantly less stable than the α·DNA intermediate. These results demonstrate that α-β association, although weak, is a formal possibility even in the absence of DNA.

ITC for Second Step Binding Reactions

The second step of ternary α·β·DNA complex formation involves adding β to the α·DNA intermediate (step 1.2 in Scheme 1), adding α to (β + DNA) (step 2.2) or adding the α·β species to DNA (step 3.2 of Scheme 1). Of these three reactions, β + α·DNA (step 1.2) was the most straightforward to analyze, since α·DNA could be treated as a stable species. Representative data for this reaction obtained at 25 °C are shown in Fig. 2B. These data defined a stoichiometric parameter of n = 1, consistent with 1:1:1 composition in the α·β·DNA complex (12). In a control experiment, a preformed complex of DNA bound with the N-terminal domain of α (α-N·DNA) was titrated with β (data not shown). No measurable interactions were detected in this experiment at 25 and 30 °C, indicating that the C-terminal domain of α is absolutely required for association of β with the α·DNA complex, in agreement with conclusions from a previous study (13). The free energy change, ΔG1.2 = −9.8 ± 0.2 kcal/mol at 25 °C, measured for binding β with α·DNA was remarkably similar to that measured for the first step in this pathway.

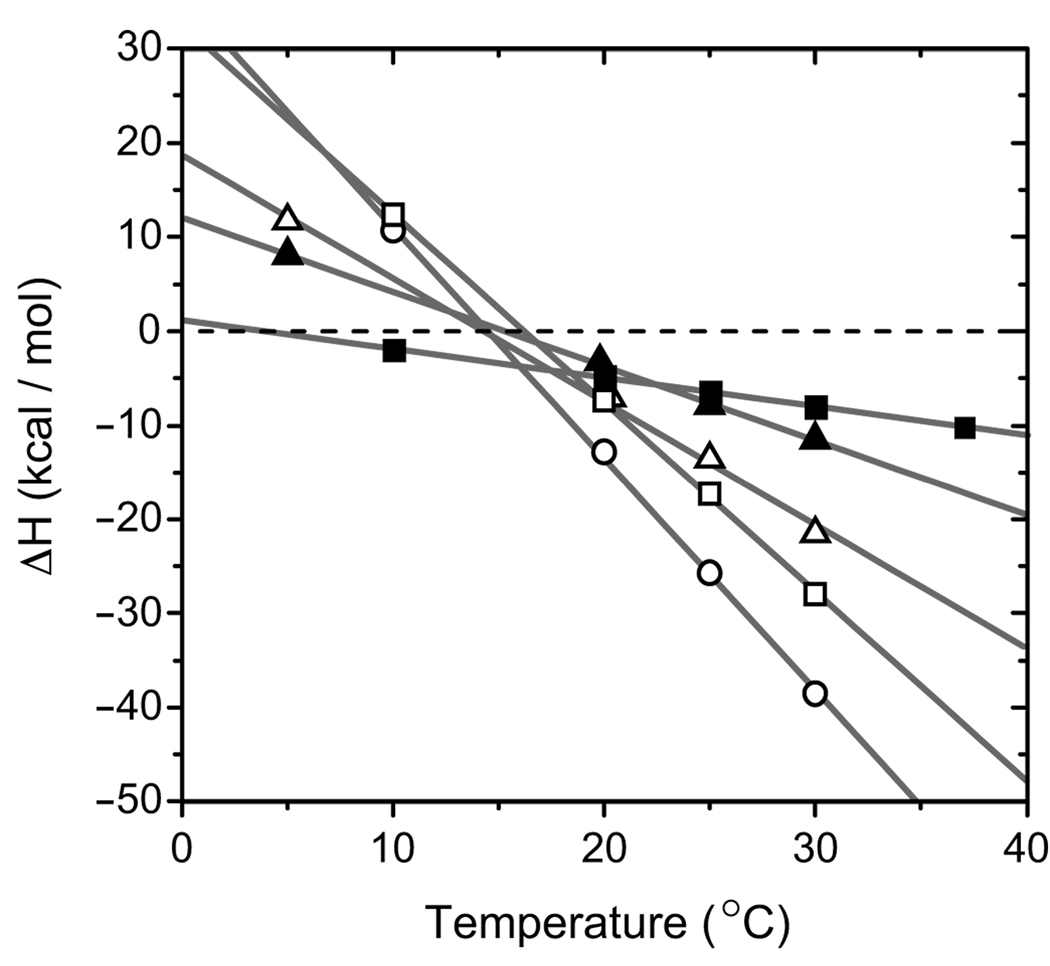

Although free energy is fairly evenly divided between steps 1.1 and 1.2 of this pathway, these steps have very distinct thermodynamic characteristics, with β + α·DNA (step 1.2) associated with enthalpy terms that are more strongly temperature-dependent and entropy terms that are larger in magnitude relative to those characterizing α + DNA (step 1.1). Binding enthalpy (ΔH) is plotted as a function of temperature in Fig. 4, and slopes in these plots define the heat capacity changes for binding (ΔCp). Heat capacity change is one of the most valuable thermodynamic parameters for inferring structural changes in binding components (27, 28). As seen in Fig. 4, data for α + DNA (filled squares, step 1.1) define a relatively shallow ΔH versus T slope, corresponding with a modest heat capacity change, ΔCp1.1 = −305 ± 3 cal mol−1 K−1. On the basis of our previous studies measuring the DNA length dependence of heat capacity and binding entropy, a portion of ΔCp1.1 probably reflects structural changes in the DNA, such as base unstacking and intramolecular G·G base pair dissociation, that are coupled with binding protein (21). Compared with the temperature dependence of the first step binding reaction, data for β + α·DNA (open squares, step 1.2) defined a distinctly steep slope with ΔCp1.2 = −2010 ± 20 cal mol−1 K−1. As will be seen below, a large and negative heat capacity change characterized each of the second step reactions and probably reflects dramatic structural reorganization coupled to binding.

FIGURE 4. Heat capacity change of binding.

Binding enthalpy (ΔH) is plotted as a function of temperature for each of five binding reactions. Filled squares, α + DNA (step 1.1 of Scheme 1); open squares, β + α·DNA (step 1.2); open circles, α + (β + DNA) (step 2.2); filled triangles, β + α (step 3.1); open triangles, α·β + DNA (step 3.2). Solid lines represents linear least-squares fitting of measurements where the slope of each line, ΔCp, is the heat capacity change of binding.

Fig. 2D shows representative data obtained by titrating α into a solution containing β + DNA (step 2.2 of Scheme 1). In analyzing this reaction, we employed a tertiary association constant (m−2) since there was no detectable interaction between β and DNA in the absence of α. The binding enthalpies obtained for this reaction were very nearly equal to the sum of the corresponding enthalpies measured for steps 1.1 and 1.2 (Table 1). The heat capacity characterizing α + (β + DNA) was ΔCp2.2 = −2430 ± 40 cal mol−1 K−1, which is also remarkably close to the sum of ΔCp1.1 + ΔCp1.2 = −2320 ± 30 cal mol−1 K−1. Enthalpy and heat capacity are apparently additive, with nearly identical values obtained whether measured by pathway 2 or as the sum of steps in pathway 1. Stoichiometric parameters (n) close to 1.0 were obtained indicating 1:1:1 complex stoichiometry in both pathways. These observations together with the fact that mixing β with DNA resulted in no detectable interaction lead us to the conclusion that all of the structural rearrangements attending steps 1.1 and 1.2 are also encountered in the reaction described by step 2.2. It may be the case that titration of β + DNA with α first leads to formation of an α·DNA intermediate that is rapidly converted to α·β·DNA. Although kinetic experiments will be needed to verify this idea, such a model is consistent with stepwise assembly of the α·β·DNA complex suggested by previous studies (20, 29).

Although enthalpy and heat capacity are additive, binding free energy was less well conserved with an apparent deficit of about 3 kcal/mol comparing ΔG2.2 with the sum of ΔG1.1 and ΔG1.2. Our interpretation of this situation is that β and DNA may interact in some nonspecific manner probably driven by attractive electrostatic forces. β has an excess of lysine and arginine residues compared with aspartate and glutamate residues, meaning that charge-charge attraction between β and DNA was anticipated. A binding energy of −3 kcal/mol corresponds to a association constant of about 200 m−1, which is well below the detection threshold for our ITC experiments. Even if β and DNA interact at this weak level, such interactions are probably different from the specific β-DNA interactions seen in the context of the α·β·DNA complex. If this is the case, the weak β-DNA interactions must be broken before new productive β-DNA interactions can reform coupled to α binding. In pathway 1, these weak and non-specific β-DNA interactions are avoided because DNA encounters α first, making subsequent association with β in step 1.2 more efficient. Given these considerations, we believe that ΔG1.1 + ΔG1.2 = −19.7 ± 0.3 kcal/mol at 25 °C represents the best estimate for α·β·DNA complex stability relative to the free α + β + DNA species.

Fig. 3B shows representative data obtained by titrating α·β into a solution containing single-stranded DNA. Because the α·β complex is relatively unstable at the concentrations employed and most but not all of the protein is associated as an α·β heterodimer, we constructed a mathematical model for obtaining thermodynamic parameters for these titrations. The model shows that protein-protein association will contribute to the heat of each injection so long as DNA is available for complex assembly. Once the DNA is consumed and completely converted into α·β·DNA, any excess α·β will experience a tendency to dissociate upon dilution into the sample cell (Fig. 3C). Although more intricate than a simple two-component binding system, we were able to take into account each of these processes in analyzing the measured data and arrived at reasonable estimates for parameters describing the isolated reaction corresponding with α·β + DNA (step 3.2 of Scheme 1), including a stoichiometric parameter close to 1.0 at each temperature. The free energy change for this reaction was ΔG3.2 = −11.5 ± 0.5 kcal/mol at 20 °C, which is in accord with the corresponding value of ΔGDNA = −11.9 ± 0.1 kcal/mol obtained for the stability of an α-β28-kDa fusion protein complexed with Cy5-labeled DNA (17).

The heat capacity change associated with this reaction, ΔCp3.2 = −1310 ± 60 cal mol−1 K−1, is 4-fold larger in magnitude compared with ΔCp1.1 = −305 ± 3 cal mol−1 K−1 for the reaction where α binds DNA without β. Since β substantially augments heat capacity change upon binding DNA, we conclude that a significant part of this heat capacity is derived from structural changes in β coupled with DNA binding.

Structural Reorganization and Cooperativity

Comparisons of first step and second step reactions underscore the interrelated and cooperative nature of the α-β-DNA system. As already noted, DNA association reactions when both proteins are present (step 3.2) have a heat capacity change that is much larger in magnitude than measured for the corresponding first step DNA association reaction when α (step 1.1) or β (step 2.1) is titrated individually into DNA. Protein-protein association reactions follow a similar pattern. When performed in the absence of DNA (step 3.1) or with DNA present in the form of α·DNA (step 1.2), α-β association is accompanied by widely different thermodynamic parameters, indicating that DNA augments α-β stability by −3.6 kcal/mol at 25 °C.

A portion of this excess free energy could potentially derive from new DNA-protein contacts formed at the α/β DNA-binding site. Favorable interactions between DNA and the α/β-site are, however, apparently offset by unfavorable energetic terms, as demonstrated by the nearly equivalent DNA binding affinities characterizing the N-terminal domain of α and fusion proteins constructed from the DNA-binding portions of α and β (17).3 The DNA-dependent excess free energy of −3.6 kcal/mol probably reflects reorganization of the α-β interface that is somehow linked with the formation of β-DNA interactions and that is not possible in the absence of DNA.

Further evidence for DNA-dependent structural reorganization is given by the large magnitude of heat capacity measured for association of β with α·DNA (step 1.2). The measured value of ΔCp1.2 = −2010 ± 20 cal mol−1 K−1 is much larger in magnitude than measured for typical protein-protein association reactions (30). Reasonable combinations of heat capacity measured for first step reactions cannot account for this very large and negative value. Comparing heat capacity measured for reactions 1.2 and 3.1 yields an excess heat capacity change of about −1200 cal mol−1 K−1, which reflects repositioning of the DNA into the newly formed α/β-site and additional DNA-dependent structural reorganization at the α-β interface that may be responsible, at least in part, for DNA-binding cooperativity.

Role of the β C-terminal Tail

The lysine-rich C-terminal tail of β may be critical for regulation of telomere complex stability and higher order organization of chromosomes within the nucleus (15, 16, 31). We therefore investigated the potential for this region of β to participate in structural changes accompanying telomere complex assembly by (a) measuring the binding behavior of β28-kDa, which lacks the C-terminal tail, and comparing this behavior with that of full-length β; and (b) determining the crystal structure of an α·β·DNA telomere complex constructed with full-length β and comparing this structure with that reported previously (18, 32) for a co-crystal complex with β28-kDa.

For binding behavior comparisons, we repeated titrations corresponding with steps 1.2, 2.1, and 3.1 in Scheme 1 and substituted β28-kDa in place of β. In each case, we obtained very comparable thermodynamic parameters (Table 1). As was the case for β, C-terminally truncated β28-kDa showed no detectable interaction with DNA if α was omitted (Scheme 1, step 2.1). Binding energies measured in the other reactions were conserved with ΔG1.2 = −10.0 ± 0.1 and −9.89 ± 0.03 kcal/mol at 25 °C for β28-kDa and β, respectively, and ΔG3.1 = −6.2 ± 0.1 kcal/mol at 25 °C for both versions of β. Binding enthalpy changes (ΔH) measured for β28-kDa + α·DNA (step 1.2) or β28-kDa + α (step 3.1) were somewhat less temperature-dependent compared with enthalpies measured for full-length β. On the basis of these comparisons, a portion of binding heat capacity, ΔΔCp ≈ −100 cal mol−1 K−1, may be attributed to the C-terminal domain of β. This value represents about 5–15% of the overall heat capacity measured for these binding reactions and suggests that the flexible and positively charged C-terminal tail may become somewhat more solvent-exposed when β associates with the telomere complex.

The crystal structure of α·β·DNA was determined by molecular replacement using x-ray diffraction data measured to the 1.91-Å resolution limit (Table 2), which is comparable with the 1.86 Å resolution limit obtained for the α·β28-kDa·DNA structure (18). Fig. 5A highlights structural similarity between these two complexes. We are confident that the new α·β·DNA crystals contained full-length β, because analysis of washed crystals by SDS-PAGE showed intact protein subunits (Fig. 5C). The root mean square deviation for main chain protein atoms (atoms CA, C, and N) was 0.5 Å when comparing the two structures. For DNA atoms, the root mean square deviation was 0.9 Å, slightly larger than that calculated for protein atoms as a consequence of the 3′-terminal base (G16) adopting an anti conformation in the new α·β·DNA crystal structure (Fig. 5C). This base adopts a syn conformation in the original α·β28-kDa·DNA structure (18). The anti conformation is seen for α·β28-kDa·DNA when crystals of this complex are grown from solutions containing high concentrations of sodium chloride,4 indicating that syn/anti conversion at the 3′-end position reflects differences in ionic strength, not the presence or absence of the C-terminal tail of β.

TABLE 2.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| 2I0Q (this work) | 1JB7 (32) | |

|---|---|---|

| Diffraction | ||

| Crystal composition | α, β, d(G3T4G4) | α, β28-kDa, d(G4T4G4), d(G4T4G4)·d(G4T4G4) |

| Concentration NaCl (m) | 1.5 | 0.05 |

| Space group | P6122 | P6122 |

| Unit cell (Å) a and b, c | 93.3, 423.8 | 93.1, 421.8 |

| Resolution limits (Å) | 50-1.91 | 20-1.86 |

| Rcryst (%) | 4.1 (46.6) | 6.5 (54.0) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.9 (95.7) | 99.1 (95.6) |

| I/σ(I) | 38.8 (3.5) | 16.9 (2.2) |

| Reflections | 690,471 | 903,239 |

| Unique reflections | 85,120 | 92,060 |

| Refinement | ||

| R (%) | 24.3 | 23.0 |

| Rfree (%) | 26.4 | 24.7 |

| Average B-values (Å2) α, β | 36.7, 57.4 | 30.1, 47.2 |

| DNA | 39.4 | 37.8 |

| Solvent | 40.9 | 40.2 |

| Root mean square deviation | ||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.0065 | 0.0067 |

| Angles (degrees) | 1.28 | 1.28 |

FIGURE 5. Crystal structure of α·β·DNA.

A, Protein subunits are shown as α-carbon traces, and the DNA is shown as an all-atom model. Protein domains and subunits are color-coded to match sketches shown in Fig. 1. The structure reported here is compared with that of a previously reported complex constructed with a C-terminally truncated form of β, also shown as an α-carbon trace (light grey lines; Protein Data Bank code 1JB7). Atoms in the DNA model are color-coded with phosphorous yellow, phosphate oxygens red, C5 methyl of T residues green, N2 nitrogen of G residues blue, and all other atoms grey. B, Detailed view of the single-stranded DNA-protein interface is shown in stereo. The region corresponds with the α/β site and is clothed with 2|Fo| – |Fc| electron density calculated to the 1.91 Å resolution limit and contoured at 1.2 σ. Inclusion of the extra 125-amino acid residues comprising the lysine-rich tail of β does not alter single-stranded DNA-protein contacts. Syn/anti isomerization noted for the 3′-terminal G residue (labeled 16) is due to differences in ionic strength, not differences in protein subunit structure (see “Results”). C, SDS-PAGE analysis of purified α (lane 1), full-length β (lane 2), and crystal components (lane 3). The near absence of smaller components verified that crystals contained intact β (41 kDa) with little or no proteolysis products.

Other differences noted in our structural comparisons involve DNA conformational heterogeneity. The original α·β28-kDa·DNA structure (32) and variants with DNA modifications (33) exhibit alternate DNA conformations with a thymine nucleotide looped out into a solvent-exposed position in some cases. In these structures, the first residue of the 12-nucleotide DNA appears to be disordered as a consequence of crystal packing contacts (18, 32). By substituting an 11-nucleotide telomere-derived DNA fragment, conformational heterogeneity within the single-stranded DNA structure is no longer detectable and all residues are defined by robust electron density. Such is the case for the current α·β·DNA structure and other structures determined for telomere complexes with β28-kDa under both low and high salt conditions.4

Aside from the syn/anti disposition of the 3′-terminal G and a simplified model for conformations sampled by the DNA, the single-stranded DNA-protein interface was remarkably well preserved when comparing telomere complexes constructed with full-length β or with C-terminally truncated β28-kDa. Hydrogen bonding interactions, lysine and arginine-phosphate salt bridges, aromatic stacking interactions, and hydrophobic packing contacts described for the original α·β28-kDa·DNA structure (18) are all retained in the new α·β·DNA structure (Fig. 5B). On the basis of these structural similarities, we conclude that the C-terminal portion of β has no direct effect on single-stranded DNA-protein interactions.

In the original low salt crystals constructed with β28-kDa, a G-quartet stabilized DNA dimer occupies a positively charged cavity constructed from the juxtaposition of three symmetry-related α·β28-kDa·DNA complexes (32). In solution, the C-terminal tail of β facilitates formation of G-quartet stabilized DNA structures (34), and we had hoped to see additional protein-G-quartet interactions by including this portion of β in these new crystals. Disappointingly, G-quartet DNA was apparently absent in the new α·β·DNA structure, although d(GGGGTTTTGGGG) DNA had been included in crystallization reactions. G-quartet DNA was absolutely required for crystal growth under the low salt conditions used for α·β28-kDa·DNA, suggesting that phosphate groups contributed by the G-quartet DNA balanced high positive electrostatic potential at crystal packing contacts (32). Crystals of α·β·DNA would not grow under low salt conditions. Under the high salt conditions required for α·β·DNA crystal growth, electrostatics are dampened by ion shielding, weakening repulsive forces at crystal packing contact points and apparently making G-quartet structures unnecessary in this crystal form. Of course, G-quartet structures are still compatible with our current observations, since lack of structure could equally well be explained by positional heterogeneity.

The portion of β with well defined electron density is the same for both structures. Residues 9β–224β are well determined in both α·β·DNA and α·β28-kDa·DNA; residues past 224β are not seen in either crystal structure. No new structured regions were found corresponding with the additional 125 residues (amino acids 261β–385β) contained within the lysine-rich C-terminal tail of β. The structural comparison together with the highly similar binding behavior observed for each form of β is entirely consistent with earlier suggestions (13, 14) that the C-terminal tail of β represents an unstructured and dynamic portion of this protein. As elaborated under “Discussion”, these characteristics make the C-terminal tail of β intriguingly comparable with intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) regions such as those found in histones (35).

DISCUSSION

A major goal of this work was to build a solid thermodynamic foundation for understanding binding cooperativity in the S. nova telomere DNA-protein complex. The ITC method allowed examination of all binding reactions leading to α·β·DNA telomere complex formation without labels, tags, or postequilibrium handling steps. Here we relate these thermodynamic measurements to structural information provided by x-ray crystallography (18–20), build a model for structural transitions that attend each binding reaction, and discuss broader implications of this work for telomere biology.

Structural Reorganization

Binding cooperativity was measured in this work as the difference in free energy, ΔΔG = −3.6 kcal/mol, comparing overall complex stability with ΔG values characterizing first step binding reactions. This value is in very close agreement with our previous study which derived ΔΔG = −3 kcal/mol from DNA binding behavior of native subunits and engineered fusion proteins (17). We believe structural reorganization provides the underlying mechanism for binding cooperativity.

Evidence for such structural changes comes from heat capacity measurements reported in our current work. A large negative heat capacity is anticipated for burial of hydrophobic groups during protein folding, protein-protein association and DNA-protein binding reactions. Measured heat capacity changes often differ from those expected on the basis of surface area calculations (36–38), and larger than expected heat capacity changes indicate that components undergo structural changes coupled with binding (39–42). In our approach, we estimated an excess heat capacity of about ΔΔCp = −1200 cal mol−1 K−1 not through surface area calculations but instead through examination of each step of the thermodynamic cycle. This is an important distinction since surface area parameters are currently unavailable for single-stranded DNA, and structures of the uncomplexed components are also not known.

How can these remarkable excess heat capacity and free energy values be interpreted in terms of telomere complex structure? Fig. 6 summarizes free energy (ΔG) and heat capacity (ΔCp) values obtained in this work and illustrates structural transitions consistent with our current understanding of this system. Many pieces of evidence point to the C-terminal domain of α and the protein-protein interaction loop contributed by β as focal points for structural reorganization underlying an allosteric switch that links DNA binding affinity to protein-protein interactions at a remote site (17). Both of these structural elements are required for DNA binding cooperativity (13, 17). Further proof that protein-protein interactions are critical for cooperative complex formation is provided by our observation that β cannot associate with an α-N·DNA complex, which lacks the protein-protein interaction domain of α. The extended nature of the protein-protein interaction loop of β suggests that these residues adopt some altered structure when β is dissociated from the complex. The fact that β28-kDa is relatively resistant to proteases (17)5 indicates that the peptide loop is not flexible or disordered in the unbound state. Accordingly, in Fig. 6 we depicted free β with the peptide loop refolded so as to interact with the globular portion of β. This model further explains why DNA-β interactions are not detectable in the absence of α, since the DNA-binding portion of β might be masked in this isoform.

FIGURE 6. Summary.

Three pathways to telomere complex formation are shown along with binding enthalpy (ΔH, kcal/mol) at 25 °C, binding free energy (ΔG, kcal/mol) at 25 °C, and heat capacity change of binding (ΔCp, cal mol−1 K−1). Parameters were measured in 0.15 m lithium chloride. The sum of free energy changes measured for steps 3.1 and 3.2 of pathway 3 falls short of the overall complex stability measured via pathway 1. The “missing” −2 kcal/mol is somewhat larger than can be reasonably accounted for by error propagation considerations alone (see Table 1 for uncertainties). A small degree of nonadditivity was similarly noted for enthalpy and heat capacity. Hidden energetic contributions may reflect the complex nature of the titration from which parameter values corresponding to step 3.2 were obtained, and we believe that the reported apparent values may underestimate the true values. This possibility is indicated by parentheses. Illustrations highlight structural transitions thought to account for a portion of ΔCp in each step. These structural transitions include resolving base stacking and G·G base-pairing interactions upon association of DNA with α (step 1.1), repositioning of DNA to occupy both α- and α/β-sites upon full complex formation (step 1.2), and DNA-dependent reorganization of the protein-protein interface (step 3.2).

Consistent with a relatively unstable α·β complex, initial α-β association does not result in a fully formed protein-protein interface (Fig. 6, step 3.1). The structural changes required for a complete protein-protein interface only occur when DNA is added to the system (Fig. 6, step 3.2). This aspect of our model explains why protein-protein association is so strongly DNA-dependent and why DNA association in the DNA + α·β reaction (step 3.2) is accompanied by such large negative heat capacity and free energy changes. Because DNA-protein and protein-protein interactions are located at a considerable distance from each other, DNA-dependent reorganization of the α-β interface resembles an allosteric system. Coupled with completion of the protein-protein interface, DNA is repositioned and refolded so as to occupy the newly formed α/β-site (Fig. 6, step 1.2). By linking DNA end position to protein-protein association in this way, access to the DNA 3′-end, required for telomerase-mediated elongation, becomes potentially sensitive to events at the protein-protein interface.

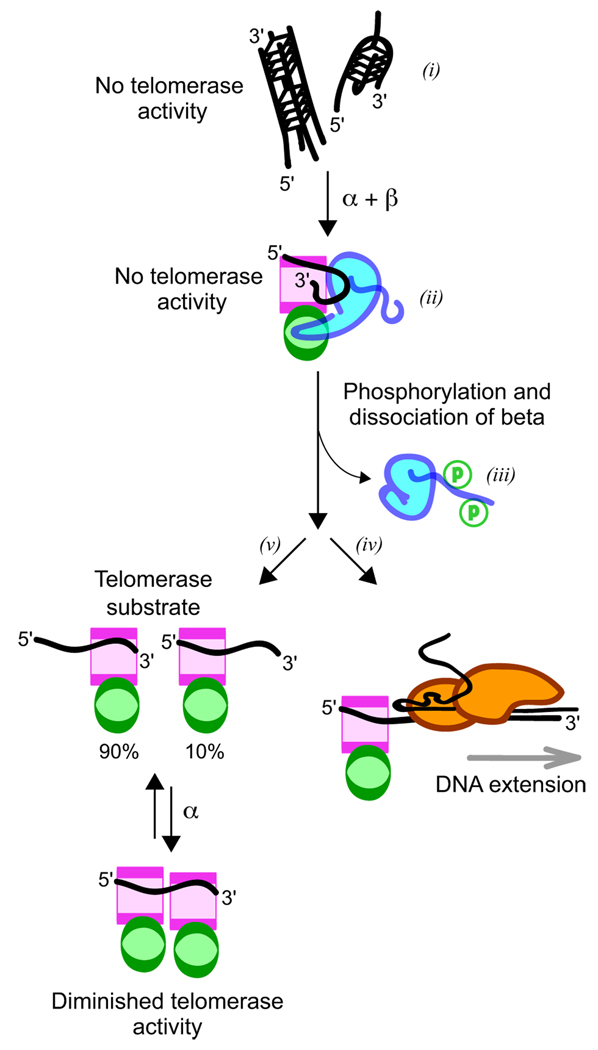

Implications for Telomere Biology

Our results have important implications for telomere biology, especially as related to telomere complex assembly and disassembly (see Fig. 7). These are critical events that potentially modulate telomerase activity. Telomere DNA in vitro readily forms potassium-ion stabilized G-quartet DNA structures, which are not suitable substrates for telomerase (i in Fig. 7) (43). S. nova telomere DNA, with its repeated d(GGGG) tracts, probably forms especially stable G-quartet structures. DNA complexed with one or two α subunits may not form a sufficiently stable complex to outcompete with G-quartet structures accessible for this DNA. Working cooperatively, α and β form a very stable DNA-protein complex (ii in Fig. 7), with an overall binding free energy measured here as ΔG = −19.7 kcal/mol that is probably sufficient to prevent or resolve G-quartet stabilized structures. As part of the α·β·DNA complex, DNA at this stage is unfolded but still inaccessible for telomerase (44).

FIGURE 7. Implications for telomere biology.

i, telomere 16-nt DNA on its own forms G-quartet stabilized multimeric structures, of which the potassium ion-associated forms are incompatible with telomerase activity. ii, DNA adopts an extended single-stranded conformation upon association with α and β telomere proteins. In this form, the 3′-terminus is inaccessible and cannot be extended by telomerase. iii, Modification of β at sites located within the unstructured lysine-rich C-terminal tail leads ultimately to dissociation of this subunit through an unknown mechanism. iv, In one plausible mechanism, modified β recruits remodeling factors that facilitate the displacement of β and the loading of telomerase to form an extension-competent complex. v, an alternative outcome in which α2·DNA complexes expected at equilibrium drive the DNA into a protected form inaccessible to telomerase.

In addition to augmenting telomere complex stability, β association is coupled with repositioning of the DNA with respect to α, which may be an important step in activation of telomerase. The significance of DNA position for telomerase activity is highlighted by results obtained for DNA-protein complexes constructed with human telomere-derived DNA fragments and the single-stranded telomere DNA-binding protein Pot1 (45). DNA·Pot1 complexes are not normally good substrates for telomerase (45); however, if the DNA-protein complex were to undergo an interconversion event that repositions Pot1 along the DNA, then the resulting DNA-protein complex can be an especially efficient substrate for telomerase so long as eight 3′-terminal nucleotides are exposed (45). The requirement for eight exposed nucleotides (six or seven are insufficient for processive telomerase activity) is very intriguing. Biochemical studies (11) and co-crystal structures of S. nova telomere proteins complexed with DNA (18–20) indicate that β-association is coupled with a net eight-nucleotide shift in DNA position, since nucleotides of the 3′-terminal telomere repeat interact with the newly formed α/β-site (see Fig. 1). The resulting α·β·DNA complex is not active for telomerase (ii in Fig. 7) (44); however, removal of β, perhaps triggered by modifications in its C-terminal tail (iii in Fig. 7), would expose these 3′-terminal nucleotides and make them available for potentially productive interaction with telomerase (iv in Fig. 7).

Dissociation of β provides a route to an elongation complex with telomerase; however, this event must be carefully coordinated to avoid α2·DNA complexes expected at equilibrium (21) that are also not telomerase substrates (v in Fig. 7) (44). Phosphorylation of residues within the lysine-rich C-terminal tail of β could provide a mechanism for complex dissociation ultimately controlled by cell cycle events (15, 16).

Although the C-terminal tail of β appears dispensable for single-stranded telomere DNA binding, phosphorylation of β in this region may nevertheless be a crucial requirement for complex disassembly. In one possible mechanism, phosphorylation could inhibit association of β with the α·DNA complex, as suggested by in vitro experiments (16). In the cell, modification of β may also facilitate interaction with other nuclear components required for DNA dissociation. These nuclear components could trigger complex disassembly by making use of the allosteric switch built into the α·β·DNA complex. Since structural reorganization intimately links α-β interactions with DNA-protein stability, accessory proteins recruited to the telomere through interaction with β could weaken the α·β·DNA complex and provide a route for DNA dissociation simply by weakening α-β interactions.

Comparison with Other Intrinsically Disordered Protein Systems

The structure reported here for full-length β complexed as α·β·DNA showed no ordered elements corresponding with 160 C-terminal residues of β. This lack of ordered structure together with a highly skewed amino-acid composition for this region (46) indicates that this portion of β may belong to the class of proteins identified as IDPs (35).

Homeodomain and high mobility group box proteins augment DNA binding affinity and specificity by inclusion of unstructured lysine and arginine-rich protein “tails” along with more stably folded DNA recognition elements (47–49). Our telomere-derived DNA fragments lack a double-stranded region. By analogy with homeodomain and HMG-box proteins, double-stranded DNA adjacent to authentic telomere ends may be the true interacting partner for the lysine-rich and unstructured C-terminal tail of β.

Perhaps the best known IDP regions are those found within the linker and core histones. Comparable with our results for thermodynamic and structural studies of β, removal of the IDP regions in core histones has very little effect on histone octamer stability (50), and these regions are not structured as determined by x-ray crystallography (51–53).

Lack of ordered structure does not mean IDPs are superfluous. In histones, the flexible IDP regions are subjected to post-translational modifications that lead to recruitment of chromatin-remodeling factors, ultimately providing access for transcription factors and RNA polymerase (54–56). If the model emerging for coordinated telomere complex disassembly holds true, then the unstructured C-terminal portion of β has a similarly profound influence over telomere nucleoprotein structure and provides access for another important polymerase, telomerase.

Acknowledgments

We thank D. P. Goldenberg for use of an isothermal titration calorimeter and S. Classen for assistance at the SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM067994 (to M. P. H). The University of Utah DNA/Peptide Research Core facility is supported by NCI, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Grant 5P30 CA42014. Research and development at the SIBYLS beamline 12.3.1 are supported by the NCI, NIH, Grant CA92584 and United States Department of Energy Grant DE-AC03 76SF00098.

The abbreviations used are: ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; aa, amino acids; nt, nucleotide; MES, 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid; IDP, intrinsically disordered protein.

P. Buczek, unpublished results.

M. P. Horvath, unpublished results.

S. C. Schultz, unpublished results.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2i0q) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

REFERENCES

- 1.Blackburn EH. Nature. 1991;350:569–573. doi: 10.1038/350569a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zakian VA. Science. 1995;270:1601–1607. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5242.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McClintock B. Genetics. 1941;26:234–282. doi: 10.1093/genetics/26.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klobutcher LA, Swanton MT, Donini P, Prescott DM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1981;78:3015–3019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.5.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henderson ER, Blackburn EH. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1989;9:345–348. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.1.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wellinger RJ, Wolf AJ, Zakian VA. Cell. 1993;72:51–60. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90049-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McElligott R, Wellinger RJ. Embo J. 1997;16:3705–3714. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottschling DE, Zakian VA. Cell. 1986;47:195–205. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90442-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Price CM, Cech TR. Biochemistry. 1989;28:769–774. doi: 10.1021/bi00428a053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gray JT, Celander DW, Price CM, Cech TR. Cell. 1991;67:807–814. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90075-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang G, Cech TR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:6056–6060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fang G, Gray JT, Cech TR. Genes Dev. 1993;7:870–882. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laporte L, Stultz J, Thomas GJ., Jr Biochemistry. 1997;36:8053–8059. doi: 10.1021/bi970283g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicke B, Rempel R, Maller J, Swank RA, Hamaguchi JR, Bradbury EM, Prescott DM, Cech TR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:1887–1893. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.11.1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paeschke K, Simonsson T, Postberg J, Rhodes D, Lipps HJ. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:847–854. doi: 10.1038/nsmb982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buczek P, Orr RS, Pyper SR, Shum M, Kimmel E, Ota I, Gerum SE, Horvath MP. J. Mol. Biol. 2005;350:938–952. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.05.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Horvath MP, Schweiker VL, Bevilacqua JM, Ruggles JA, Schultz SC. Cell. 1998;95:963–974. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81720-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peersen OB, Ruggles JA, Schultz SC. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nsb761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Classen S, Ruggles JA, Schultz SC. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;314:1113–1125. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.5191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buczek P, Horvath MP. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;359:1217–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.02.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP. Numerical Recipes in C. 2nd Ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1992. pp. 689–699. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otwinowski A, Minor W. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Rice LM, Simonson T, Warren GL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones TA, Zou JY, Cowan SW, Kjeldgaard Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A. 1991;47:110–119. doi: 10.1107/s0108767390010224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raghuraman MK, Cech TR. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:4543–4552. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.15.4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prabhu NV, Sharp KA. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2005;56:521–548. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.56.092503.141202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cooper A, Johnson CM, Lakey JH, Nollmann M. Biophys. Chem. 2001;93:215–230. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(01)00222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wojciechowski M, Fogolari F, Baginski M. J. Struct. Biol. 2005;152:169–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stites WE. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:1233–1250. doi: 10.1021/cr960387h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baumann P. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:832–833. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1005-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horvath MP, Schultz SC. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;310:367–377. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Theobald DL, Schultz SC. Embo J. 2003;22:4314–4324. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang G, Cech TR. Cell. 1993;74:875–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90467-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansen JC, Lu X, Ross ED, Woody RW. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:1853–1856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R500022200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stern JC, Anderson BJ, Owens TJ, Schildbach JF. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:29155–29159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402965200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berger C, Jelesarov I, Bosshard HR. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14984–14991. doi: 10.1021/bi961312a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lundback T, Chang JF, Phillips K, Luisi B, Ladbury JE. Biochemistry. 2000;39:7570–7579. doi: 10.1021/bi000377h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spolar RS, Record MT., Jr Science. 1994;263:777–784. doi: 10.1126/science.8303294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ayala YM, Vindigni A, Nayal M, Spolar RS, Record MT, Jr, Di Cera E. J. Mol. Biol. 1995;253:787–798. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Boniface JJ, Reich Z, Lyons DS, Davis MM. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999;96:11446–11451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.20.11446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kwong PD, Doyle ML, Casper DJ, Cicala C, Leavitt SA, Majeed S, Steenbeke TD, Venturi M, Chaiken I, Fung M, Katinger H, Parren PW, Robinson J, Van Ryk D, Wang L, Burton DR, Freire E, Wyatt R, Sodroski J, Hendrickson WA, Arthos J. Nature. 2002;420:678–682. doi: 10.1038/nature01188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahler AM, Williamson JR, Cech TR, Prescott DM. Nature. 1991;350:718–720. doi: 10.1038/350718a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Froelich-Ammon SJ, Dickinson BA, Bevilacqua JM, Schultz SC, Cech TR. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1504–1514. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.10.1504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lei M, Zaug AJ, Podell ER, Cech TR. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20449–20456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502212200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hicke BJ, Celander DW, MacDonald GH, Price CM, Cech TR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:1481–1485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Privalov PL, Jelesarov I, Read CM, Dragan AI, Crane-Robinson C. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;294:997–1013. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crane-Robinson C, Dragan AI, Privalov PL. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2006;31:547–552. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dragan AI, Li Z, Makeyeva EN, Milgotina EI, Liu Y, Crane-Robinson C, Privalov PL. Biochemistry. 2006;45:141–151. doi: 10.1021/bi051705m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karantza V, Freire E, Moudrianakis EN. Biochemistry. 2001;40:13114–13123. doi: 10.1021/bi0110140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Luger K, Mader AW, Richmond RK, Sargent DF, Richmond TJ. Nature. 1997;389:251–260. doi: 10.1038/38444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White CL, Suto RK, Luger K. Embo J. 2001;20:5207–5218. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.18.5207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Suto RK, Clarkson MJ, Tremethick DJ, Luger K. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2000;7:1121–1124. doi: 10.1038/81971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cheung P, Allis CD, Sassone-Corsi P. Cell. 2000;103:263–271. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Science. 2001;293:1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Turner BM. Cell. 2002;111:285–291. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]