Abstract

Background & Aims

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a PAS domain transcription factor previously known as the “dioxin receptor” or “xenobiotic receptor.” The goal of this study is to determine the endobiotic role of AhR in hepatic steatosis.

Methods

Wild type, constitutively activated AhR (CA-AhR) transgenic, AhR null (AhR-/-), and fatty acid translocase CD36/FAT null (CD36-/-) mice were used to investigate the role of AhR in steatosis and the involvement of CD36 in the steatotic effect of AhR. The promoters of the mouse and human CD36 genes were cloned and their regulation by AhR was analyzed.

Results

Activation of AhR induced spontaneous hepatic steatosis characterized by the accumulation of triglycerides. The steatotic effect of AhR is likely due to the combined upregulation of CD36 and fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs), suppression of fatty acid oxidation, inhibition of hepatic export of triglycerides, increase in peripheral fat mobilization, and increased hepatic oxidative stress. Promoter analysis established CD36 as a novel transcriptional target of AhR. Activation of AhR in liver cells induced CD36 gene expression and enhanced fatty acid uptake. The steatotic effect of an AhR agonist was inhibited in CD36-/- mice.

Conclusions

Our study reveals a novel link between AhR-induced steatosis and the expression of CD36. Industrial or military exposures to dioxin and related compounds have been linked to increased prevalence of fatty liver in humans. Results from this study may help to establish AhR and its target CD36 as novel therapeutic and preventive targets for fatty liver disease.

Keywords: aryl hydrocarbon receptor, fatty acid metabolism, steatosis, gene regulation

INTRODUCTION

The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) is a ligand-activated transcription factor that belongs to the basic helix-loop-helix/Period-AhR nuclear translocator-Single minded (bHLH/PAS) family proteins. AhR was originally isolated and characterized as a “xenobiotic receptor” sensing xenotoxicants, such as the 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD), or dioxin.1 Industrial or military exposures to dioxin, such as those associated with the use of herbicide and defoliant Agent Orange during the Vietnam War, have been linked to detrimental health effects.

AhR regulates xenobiotic enzyme expression by binding as heterodimers with the AhR nuclear translocator (Arnt)2 to the dioxin responsive elements (DREs) in the target gene promoters.3,4 Subsequent studies, mainly through the characterization of AhR-/- mice5,6, suggest that AhR also has endobiotic functions by affecting physiology and tissue development.6-8 The endobiotic function of AhR is also supported by the identification of endogenous AhR agonists.3,4 However, the molecular mechanism by which AhR affects normal physiology remains largely unknown.

Hepatic steatosis, or fatty liver, is a strongly associated with metabolic syndrome.9 Liver plays a central role in fatty acid and triglyceride metabolism. Other than de novo fatty acid synthesis, another major source of hepatic lipids is circulating free fatty acids (FFAs). Upon uptake by hepatocytes, FFAs can be converted to triglycerides, especially when intrahepatic FFAs are in excess. Indeed, FFA concentrations in plasma are often increased in disorders associated with hepatic steatosis.10 Hepatic uptake of FFAs is mediated by cell surface receptors, including the fatty acid translocase CD36/FAT. CD36 belongs to the class B scavenger receptor family. CD36 has been documented to play an important role in hepatic steatosis, and an increased expression of CD36 was found in patients of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).11 In addition to CD36, fatty acid uptake can also be facilitated by the fatty acid transport proteins (FATPs) and liver fatty acid-binding protein.12 Within the liver, fatty acids are either oxidized or re-esterized into triglycerides for storage. Fatty acid oxidation can occur in mitochondria, peroxisomes, or endoplasmic reticulum. The carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT-1) is required for mitochondrial β-oxidation, whereas the palmitoyl acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (ACOX-1) catalyzes peroxisomal β-oxidation.13 The liver triglycerides can be secreted as very-low density lipoprotein (VLDL) into the blood stream and utilized by the peripheral tissues.

In this study, we showed that activation of AhR induced marked hepatic steatosis, even when mice were maintained on a standard chow diet. We also showed that CD36 is a novel AhR target gene and plays an important role in the steatotic effect of AhR.

METHODS

Generation of CA-AhR transgenic mice, animal diet, and histology

To construct CA-AhR, AhR coding regions corresponding to amino acids 1-287 and 422-805 were amplified by PCR.14 See Supplementary Methods for details of the production of the CA-AhR transgenic mice. Transgenic mice and their WT littermates used in this study were maintained in FVB background. When necessary, doxycycline (DOX, 2 mg/ml) was given in drinking water. The creation of CD36-/- mice in C57BL/6J background15 and AhR-/- mice in C57BL/6J and SvJ129 mixed background7 was described. Mice were maintained in Prolab RMH3000, a standard rodent chow from PMI Nutrition International (St. Louis, MO) that contains 65% carbohydrates, 15% fat, and 20% protein. Mice were allowed for free access to food and water. Liver histology was performed as we have previously described.16 The use of mice in this study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Chemicals, animal drug treatment, and body composition analysis

TCDD and FICZ were purchased from Cambridge Isotope (Andover, MA) and Biomol (Plymouth Meeting, PA), respectively. Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma. When necessary, mice received a single gavage of vehicle (corn oil) or TCDD (30 μg/kg, dissolved in corn oil) by using plastic-coated mouse feeding needles (20GX1-1/2) and were sacrificed 7 days later. The gavage volume is 100 μl for a 20-g mouse. Mouse body composition was analyzed by using EchoMRI-100™ from Echo Medical Systems (Houston, TX).

Plasmid constructs, reporter gene assay, and siRNA transfection

The human CD36 promoter (nt -1961 to +57) was previously reported.16 The mouse CD36 promoter (nt -1411 to +56) was PCR-amplified. CV-1 and HepG2 cells were transfected in 48-well plates as described.17 The transfected cells were then treated with drugs for 24 hrs before luciferase and β-gal assays. Transfection efficiency was normalized against β-gal activity derived from the co-transfected pCMX-β-gal plasmid. Fold inductions were calculated as relative reporter activity compared to empty vector-transfected or vehicle-treated cells. Lipofectamine 2000 was used for AhR siRNA transfection.17 The human AhR siRNA (Cat#SI02780148) and a control scrambled siRNA (Cat#1027280) were purchased from QIAGEN (Valencia, CA).

Cell culture and primary hepatocyte preparation

Huh-7 cells were maintained in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. Primary human hepatocytes were obtained through the Liver Tissue Procurement and Distribution System. Primary mouse hepatocytes were prepared by collagenase perfusion.18 Primary hepatocytes were maintained in hepatocyte maintenance medium from Cambrex (Walkersville, MA). After overnight incubation, cells were treated with TCDD (10 nM), FICZ (200 nM), or Indigo (10 μM) for 24 hrs.

Northern blot, real-time RT-PCR, and Western blot analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIZOL reagent from Invitrogen. Northern hybridization using 32P-labeled cDNA probe was carried out as described.16 SYBR Green-based real-time PCR was performed with the ABI 7300 Real-Time PCR System.17 Data was normalized against control cyclophilin. Primer sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Primary antibodies used for Western blot analysis include ApoB100 (H-15) and ApoB48 (S-18) from Santa Cruz, CD36 (NB400-144) from Novus (Littleton, CO), AhR (SA-210) from Biomol, and β-actin (A1978) from Sigma.

DRE identification, electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA), and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

DREs were identified by inspecting CD36 gene promoter sequences for DRE consensus sequence TNGCGTG.19 EMSA was carried out using 32P-labeled oligonucleotides and receptor proteins prepared by the TNT method.16 For ChIP assay, Huh-7 cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or TCDD (10 nM) for 24 hrs. See reference 18 and Supplementary Methods for ChIP procedures and primer sequences.

Measurement of circulating and tissue lipids, serum chemistry, and lipid peroxidation

Circulating and tissue lipids were measured as previously described16 and detailed in Supplementary Methods. Plasma FFA and ALT levels were measured by using assay kits from Biovision (Mountain View, CA) and Calchem (Huntington, NY), respectively. To measure malondialdehyde (MDA) level, liver lipid extracts were added to a reaction mixture containing 0.67% thiobarbituric acid. Samples were then boiled for 1 hr at 95°C and centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min. Supernatant absorbance was measured by spectrophotometry at 532 nm and the MDA concentration was determined using a standard curve generated by using the standard chemical 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane.

Measurement of fatty acid uptake

This was performed by incubating cells with 4,4-difluoro-5,7-dimethyl-4-bora-3α, 4α-diaza-s-indacene-3-hexadecanoic acid (BODIPY-C16) from Invitrogen. See Supplementary Methods for details.

Measurement of peroxisomal β-oxidation

This was measured by monitoring the rate of NAD+ reduction to NADH at 340 nm using palmitoyl-CoA as a substrate.20 See Supplementary Methods for details.

Measurement of VLDL secretion rate

VLDL secretion rate in vivo was measured as previously described.21 Briefly, 16 hr-fasted mice were injected with Triton WR1339 (500 mg/kg in saline), a lipoprotein lipase inhibitor that inhibits VLDL hydrolysis, via the tail vein. VLDL secretion rate was calculated by subtracting triglyceride levels at 0 min from their counterpart levels at 90 min.

Statistical analysis

Results were presented as means ± SD. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA where appropriate. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Generation of tetracycline inducible transgenic mice expressing the constitutively activated AhR (CA-AhR) in the liver

To examine the effect of AhR activation in vivo, we generated tetracycline inducible CA-AhR transgenic mice expressing CA-AhR (Figure 1A). CA-AhR was constructed by deleting the minimal ligand-binding domain (amino acids 287-422) of AhR.14 CA-AhR bound to a prototypical DRE and transactivated an AhR reporter gene without an exogenously added ligand (Supplementary Figure 1). The “Tet-off” transgenic system is composed of two transgenic lines with one line (TetRE-CA-AhR) expressing CA-AhR under the control of a minimal cytomegalovirus promoter (PCMV) fused to the tetracycline responsive element (TetRE), and the other line (FABP-tTA) expressing the tetracycline transcriptional activator (tTA) in liver and intestine under the control of the fatty acid binding protein (FABP) gene promoter.16 In mice carrying both transgenes, tTA would bind to TetRE and induce the expression of CA-AhR, whereas treatment with DOX would dissociate tTA from TetRE and thus silence the expression of CA-AhR (Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Generation of transgenic mice expressing the constitutively activated AhR (CA-AhR) in the liver.

(A) Schematic representation of the “Tet-off” FABP-tTA/TetRE-CA-AhR transgenic system. DOX, doxycycline; FABP, fatty acid binding protein; PCMV, minimal CMV promoter; TetRE, tetracycline responsive element; tTA, tetracycline transcriptional activator. (B) Hepatic and intestinal expression of CA-AhR as shown by Northern blot analysis using the AhR cDNA probe. The membranes were stripped and re-probed with Cyp1a2 for a positive control of AhR activation and Gapdh for a loading control. (C) Treatment of bi-transgenic mice with DOX for one week silenced the expression of CA-AhR and induction of Cyp1a2. (D) CA-AhR transgene is not expressed in tissues outside of the liver and intestine, as determined by semi-quantitative RT-PCR. Cyclophilin is included as a loading control. (E) Activation of AhR in CA-AhR mice was not associated with obvious hepatotoxicity. Serum levels of ALT were measured in female mice of 5-6 weeks of age. Mice in the TCDD group received a single p.o. dose of TCDD (30 μg/kg) and sacrificed 7 days after. Each group has at least five mice. *, P<0.05.

Pronuclear microinjection of the FABP-tTA transgene yielded four independent tTA lines, among which Line 71 was chosen for subsequent cross-breeding due to the high expression of rTA in both the liver and intestine. Cross-breeding of six TetRE-CA-AhR founders with FABP-tTA mice yielded four bi-transgenic lines, among which Lines 4 and 6 were found to express CA-AhR in the liver and small intestine of both sexes (Figure 1B). The bi-transgenic mice also showed an increased mRNA expression of Cyp1a2, a known AhR target gene (Figure 1B). Interestingly, Line 3 expressed CA-AhR in the liver but not in the intestine, whereas Line 8 expressed CA-AhR in the liver and intestine of males but not females (Figure 1B). Line 4 was chosen for further characterization. The expression of CA-AhR and induction of Cyp1a2 were abolished when mice were given DOX-laced drinking water for one week (Figure 1C). CA-AhR was specifically expressed in the liver and intestine, but not in several other AhR-expressing tissues (Figure 1D). The serum level of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was not significantly changed in transgenic mice (Figure 1E), suggesting that the genetic activation of AhR was not associated with hepatotoxicity. This was in contrast to the known toxicity in TCDD-treated mice (Figure 1E, and reference 22). CA-AhR and TCDD treatment was equally efficient in inducing Cyp1a2 gene expression (data not shown).

CA-AhR transgenic mice developed spontaneous hepatic steatosis, and showed decreased body weight and fat mass

CA-AhR transgenic mice showed a modest hepatomegaly. At 5 weeks, the liver accounted for 5.08% of total body weight in WT females, and 5.64% in transgenic females, an increase of 11% (Figure 2A). H&E staining showed the hepatocytes from transgenic mice had a vacuolated-cytoplasmic appearance (Figure 2B), suggestive of lipid deposition. Oil-red O staining confirmed the increased lipid droplets in transgenic mice (Figure 2B). Liver tissue concentrations of triglyceride, but not cholesterol, were increased in transgenic mice (Figure 2C). The steatotic phenotype depended on AhR activation, because treatment of transgenic mice with DOX normalized Oil-red O staining and triglyceride content (Figure 2B and 2C). Steatosis was also observed in Line 3, in which CA-AhR was expressed only in the liver (data not shown), suggesting that activation of AhR in the liver was sufficient for the steatotic phenotype. Interestingly, the plasma level of triglycerides was not changed in transgenic mice (Figure 2D). The transgenic mice also showed modest but significantly decreased body weight compared to their WT littermates (Figure 2E). The transgenic mice had a 23% decrease in fat mass and 4% increase in lean mass when measured as percentages of body weight (Figure 2F).

Figure 2. CA-AhR transgenic mice developed spontaneous hepatic steatosis, and showed decreased body weight and fat mass.

Five to six weeks-old female mice were used. (A) The liver weight (LW) was measured as percentage of the total body weight (BW). (B) Liver sections of wild type (WT) and CA-AhR mice were stained with H&E (a and b) or Oil-red O (c-e). Mouse in (e) was treated with DOX for two weeks. The original magnification of all panels is 200x. (C-E) Measurements of liver lipid contents (C, n=4 for each group), plasma triglyceride content (D), and body weight (E). (F) Fat mass and lean mass were measured by MRI and the results are presented as percentage of BW. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, compared to the wild type, or the comparisons are labeled.

Activation of AhR in transgenic mice induced hepatic expression of CD36 and uptake of fatty acids

To understand the mechanism by which AhR promotes steatosis, we profiled the expression of genes in the liver by Affymetrix microarray analysis (see Supplementary Methods for details; The NCBI GEO accession number is GSE19518). The microarray analysis suggested that the expression of CD36 was induced in the liver of CA-AhR transgenic mice. In contrast, the expression of Srebp-1c and its target lipogenic enzymes Fas, Acc and Scd-1 was unchanged (data not shown). The induction of CD36 was confirmed by real-time PCR (Figure 3A), Northern blot (data not shown), and Western blot (Figure 3B) analyses. The regulation of CD36 was transgene-dependent, because the induction was abolished upon DOX treatment (Figure 3A and 3B). Interestingly, the AhR-mediated CD36 regulation was tissue specific, because the intestinal expression of CD36 remained unchanged despite the expression of the transgene in this tissue (data not shown). The hepatic induction of CD36 was also observed in WT mice treated with TCDD (Figure 3C), and this induction was abolished in AhR-/- mice (Figure 3C). In examining the transgenic effect on the expression of fatty acid transfer proteins (FATPs)12 and cell surface lipoprotein receptors that also contribute to lipid uptake, we found that the expression of Fatp1 and Fatp2 was modestly, but significantly, increased in transgenic mice; whereas the expression of Fatps 3-5, VLDLR, LDLR, SR-A, and SR-B was not affected (Figure 3D).

Figure 3. Activation of AhR in transgenic mice induced hepatic expression of CD36 and uptake of fatty acids.

(A) Real-time PCR analysis on the hepatic expression of CD36 mRNA in two-month old female mice. When applicable, mice were treated with DOX for 2 weeks before sacrificing. N=4 for each group. (B) Western blot analysis on the protein expression of CD36. Lanes represent individual mice. (C) Expression of CD36 and Cyp1a2 in WT and AhR-/- mice as determined by real-time PCR. (D) Real-time PCR analysis on the hepatic expression of Fatps, VLDLR, LDLR, SR-A, and SR-B. N=6 for each group. (E) Free fatty acid uptake in primary mouse hepatocytes was monitored by the uptake of BODIPY-C16. Top and bottom panels are fluorescence and phase contrast images of the cells, respectively. DOX concentration is 1 μg/ml. (F) Quantification of BODIPY-C16 uptake in (E). AU, arbitrary unit. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, compared to control animals, or the comparisons are labeled.

To determine whether the elevated expression of fatty acid transporters led to increased fatty acid uptake, primary hepatocytes were isolated and evaluated for fatty acid uptake by incubating cells with BODIPY-C16, a fluorescent fatty acid analog. As shown in Figure 3E and 3F, the BODIPY-C16 uptake by hepatocytes of transgenic mice was markedly increased, and this effect was largely abrogated upon DOX treatment. The transgene had little effect on the uptake of fluorescent LDL (Dil-LDL) (data not shown).

Treatment of primary human hepatocytes or Huh-7 human hepatoma cells with AhR agonists also induced the expression of CD36 (Supplementary Figure 2), suggesting that the regulation is conserved in human cells. In Huh-7 cells, treatment with TCDD increased the uptake of BODIPY-C16, but this effect was abolished when cells were transfected with AhR siRNA (Supplementary Figure 2).

The mouse and human CD36 gene promoters are transcriptional targets of AhR

Inspection of the mouse and human CD36 gene promoters revealed several putative DREs whose bindings to the AhR-Arnt heterodimers were confirmed by EMSA (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figure 3). ChIP analysis was performed on Huh-7 cells to determine whether AhR was recruited onto the CD36 gene promoter. As shown in Figure 4B, recruitment of AhR to both DREs in the human CD36 gene promoter was detected in TCDD-treated cells. Moreover, luciferase reporter genes containing the mouse (pGL-mCD36) or human (pGL-hCD36) CD36 promoters were activated by WT AhR in the presence of the AhR agonist 3-MC, or by CA-AhR without an exogenously added ligand (Figure 4C and 4D). Mutation of DREs abrogated AhR-dependent transactivation. pGL-mCD36 and pGL-hCD36 were also activated by the endogenous AhR agonists Indigo23 and FICZ24 (Figure 4E).

Figure 4. The mouse and human CD36 gene promoters are transcriptional targets of AhR.

(A) Top: The sequences of mouse and human CD36 dioxin responsive elements (DREs) and their mutant variants. Underlined are DREs and their mutants. Bottom: EMSA results. (B) Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays to show the recruitment of AhR onto CD36 promoter. Huh-7 cells were treated with vehicle (Veh) or 10nM of TCDD (T) for 24 hrs. CYP1A1/DRE and CYP7B1/non-DRE were included as a positive control and negative control, respectively. (C and D) Activation of the mouse (C) and human (D) CD36 promoter reporter genes by AhR in the presence of 3-MC, or by CA-AhR without an exogenously added ligand. HepG2 cells were co-transfected with indicated reporters and receptors. Transfected cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or 3-MC (2 μM) for 24 hrs before luciferase assay. (E) Activation of mCD36 and hCD36 promoter reporter genes by endogenous AhR agonists Indigo (10 μM) and FICZ (200 nM). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

Loss of CD36 in mice inhibited the steatotic effect of an AhR agonist

Having established CD36 as an AhR target gene, we went on to determine whether the expression of CD36 was required for the steatotic effect of AhR. As shown in Figure 5A and 5B, the BODIPY-C16 uptake by primary hepatocytes derived from WT mice was significantly increased by TCDD, but the TCDD effect was abolished in CD36-/- hepatocytes. To examine the effect of loss of CD36 on steatosis in vivo, WT and CD36-/- female mice were treated with a single dose of TCDD and the mice were sacrificed 7 days later. Treatment of WT mice with TCDD induced steatosis as confirmed by the measurement of liver triglyceride content (Figure 5C), which was consistent with a previous report.22 The steatotic effect of TCDD was inhibited in CD36-/- mice (Figure 5C). TCDD treatment also decreased the plasma triglyceride level in WT mice, and this effect was abolished in CD36-/- mice (Figure 5D).

Figure 5. Loss of CD36 in mice inhibited the steatotic effect of an AhR agonist.

(A and B) Free fatty acid uptake in primary mouse hepatocytes from WT and CD36-/- mice treated with vehicle (Veh) or TCDD is monitored by the uptake of BODIPY-C16. (A) Top and bottom panels are fluorescence and phase contrast images of the cells, respectively. (B) Quantification of BODIPY-C16 uptake in (A). TCDD concentration is 10 nM. (C and D) Two-month old female mice were gavaged with a single dose of TCDD (30 μg/kg). The mice were sacrificed 7 days later and subjected to the measurements of hepatic (C, n=4 for each group) and plasma (D, n=5 for each group) triglyceride levels. Mice were fasted for 16 hrs before sacrificing. *, P<0.05.

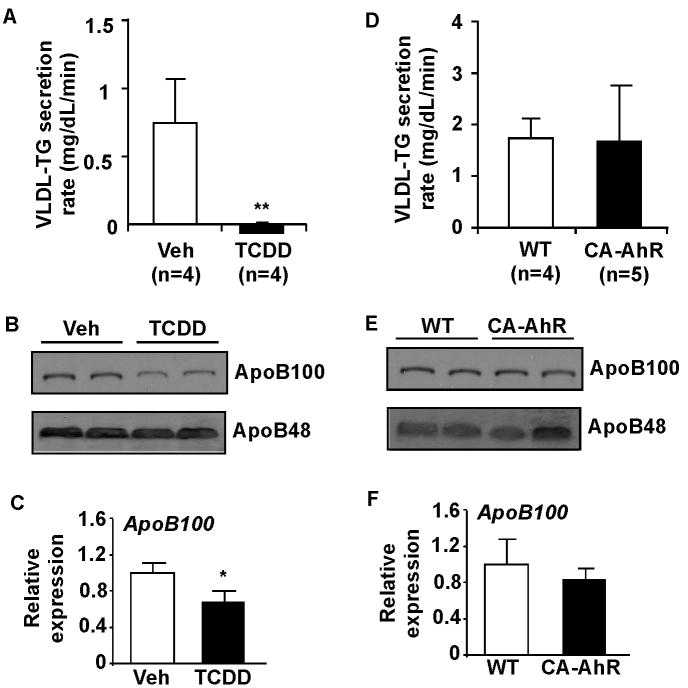

Treatment with AhR agonist inhibited VLDL-triglyceride secretion

Treatment of WT mice with TCDD for 7 days resulted in an inhibition of VLDL-triglyceride secretion (Figure 6A). The plasma protein levels of ApoB100, but not ApoB48, were decreased in TCDD-treated mice (Figure 6B). Interestingly, the hepatic mRNA expression of ApoB100 was also decreased in TCDD-treated WT mice (Figure 6C), although ApoBs are better known for their regulation at the protein translation and degradation levels.25 The mechanism for TCDD inhibition of ApoB100 remains to be determined. The suppression of VLDL-triglyceride secretion by TCDD was intact in CD36-/- mice (data not shown), suggesting that the effect was CD36-independent. Interestingly, VLDL-triglyceride secretion in CA-AhR transgenic mice was not affected (Figure 6D), and the transgene had little effect on the plasma levels of ApoB100/48 (Figure 6E), or hepatic mRNA expression of ApoB100 (Figure 6F). The expression of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP), a protein required for the assembly of VLDL, was unchanged in either TCDD-treated WT mice or CA-AhR transgenic mice (Supplementary Figure 4).

Figure 6. Treatment with AhR agonist inhibited VLDL-triglyceride secretion.

(A) Two-month old WT female mice were treated with a single dose of TCDD (30 μg/kg) for 7 days before measured for VLDL-triglyceride (TG) secretion. (B and C) Measurements of ApoB protein (B, shown is the Western blot result on plasma) and ApoB100 mRNA (C, shown is the real-time PCR result on liver) levels. (D-F) VLDL-TG secretion (D), plasma ApoB protein (E), and liver ApoB100 mRNA (F) levels in CA-AhR transgenic mice. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01, compared to the vehicle control.

Activation of AhR in transgenic mice inhibited hepatic fatty acid β-oxidation, decreased white adipose tissue (WAT) adiposity, and increased hepatic stress

The transgenic suppression of PPARα and its target genes acyl-coenzyme A oxidase 1 (Acox1), thiolase, long-chain Acyl CoA dehydrogenase (Lcad), and Cyp4a enzymes, initially suggested by microarray analysis (data not shown), was confirmed by real-time PCR (Figure 7A). Consistent with the suppression of Acox-1, the rate-limiting enzyme of peroxisomal β-oxidation, the liver extracts from transgenic mice exhibited decreased peroxisomal β-oxidation when palmitoyl-CoA was used as the substrate (Figure 7B). In contrast, the fasting plasma level of β-hydroxybutyrate, an indicator of mitochondrial β-oxidation, was not significantly affected (Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 7. Activation of AhR in transgenic mice inhibited hepatic fatty acid β-oxidation, decreased white adipose tissue (WAT) adiposity, and increased hepatic stress.

(A) Suppression of PPARa and its target genes involved in fatty acid oxidation in two-month old female CA-AhR transgenic mice, as shown by real-time PCR analysis. N=6 for each group. (B) Inhibition of peroxisomal β-oxidation in the liver extracts of transgenic mice. (C) Representative appearance of the omental fat, H&E staining of epididymal fat, and quantification of adipocyte size. (D) Omental fat tissue weight (WAT) was measured as percentage of total body weight (BW) in two-month old male WT and CD36-/- mice gavaged with vehicle (Veh) or TCDD (30 μg/kg) 7 days prior to being sacrificed (n=5 for each group). (E) Abdomen fat triglyceride lipase (ATGL) and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) mRNA expression as measured by real-time PCR analysis (N=5 for each group). (F) Hepatic concentrations of malondialdehyde (MDA). Liver lipids were extracted from 5-6 week old female mice and subjected to MDA measurement. When necessary, transgenic mice were treated with DOX for 2 weeks. N=3 for each group. *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01.

The decreased fat mass in transgenic mice was first suggested by MRI body composition analysis (Figure 2F). Necropsy showed smaller omental fat and adipocyte hypotrophy (Figure 7C) in transgenic mice. Treatment of WT mice with TCDD also decreased the omental fat mass (Figure 7D). Consistent with the decreased adiposity, the mRNA expression of adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL) was significantly increased in TCDD-treated WT mice (Figure 7E) and transgenic mice (data not shown), but the expression of hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) was unchanged. ATGL is a predominant adipose lipase involved in fat mobilization. The effects of TCDD on omental fat mass and ATGL gene expression were CD36-dependent, because these effects were abolished in CD36-/- mice (Figure 7D and 7E).

We also examined the transgenic effect on oxidative stress, inflammation, and tissue injuries. Lipid peroxidation was measured as a surrogate marker for oxidative stress. As shown Figure 7F, activation of AhR increased the liver concentration of the lipid peroxidation end product MDA, whereas this effect was abolished in DOX-treated transgenic mice. The hepatic mRNA expression of TNFα, but not IL-6, was significantly increased in the transgenic mice (Supplementary Figure 6). The transgene had little effect on apoptosis or proliferation (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have revealed an endobiotic function of AhR in fatty acid metabolism and hepatic steatosis. The AhR-induced fatty liver is likely a result of the combined effect of increased expression of CD36, suppression of fatty acid oxidation, increase in peripheral fat mobilization, and increased hepatic oxidative stress. Activation of AhR in liver cells induced CD36 gene expression and increased fatty acid uptake. CD36 is a transcriptional target of AhR and required for the fatty acid uptake and steatotic effect of AhR. The inhibition of VLDL-triglyceride secretion may have also contributed to the steatotic effect of TCDD. Interestingly, the CA-AhR transgene had little effect on VLDL secretion, the mechanism of which remains to be understood.

The implication of CD36 in steatosis has been recognized. In patients of type 2 diabetes, food intake increases liver fatty acid uptake,26 indicating the existence of a mechanism regulating hepatic fatty acid transport. An increased expression of CD36 was observed in the liver of high-fat diet fed mice27 and ob/ob mice.28 A forced expression of CD36 in the mouse liver increased fatty acid uptake and triglyceride storage.29 Moreover, an increased expression of CD36 was found in the liver of NAFLD patients.11 Together, these results suggest a causative role for CD36 in the pathogenesis of hepatic steatosis. Activation of CD36 gene expression has also been proposed to play a role in the steatotic effect of nuclear receptors pregnane X receptor16 and liver X receptor.30

The inhibition of hepatic fatty acid oxidation may have also contributed to the steatotic effect of AhR. The inhibition of fatty acid oxidation may lead to the storage of excess fatty acids as triglycerides. We showed that activation of AhR inhibited peroxisomal β-oxidation of fatty acids. Peroxisomal β-oxidation is important because peroxisomes represent an exclusive site for β-oxidation of very-long chain fatty acids. Peroxisomal β-oxidation becomes increasingly important during the periods of increased delivery of fatty acids into the liver in diabetes and fatty liver diseases.31

Results of this study are potentially implicated in NAFLD or simple steatosis. If unmanaged, NAFLD may develop into nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), in which the fat accumulation is associated with inflammation and scarring of the liver.32 Our transgenic mice showed signs of oxidative stress and inflammation, such as increased lipid peroxidation and expression of TNFα. It remains to be determined whether the hepatic steatosis will eventually progress to NASH. It was reported that dioxin exposure was associated with increased prevalence of fatty liver in human populations.33 AhR-mediated FFA uptake provides a plausible mechanism by which polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which can be generated during food-cooking, cigarette smoking, and use of herbicides/pesticides, may promote fatty liver.

In summary, our study provides an unexpected link between AhR-induced hepatic steatosis and the expression of CD36. The tetracycline inducible AhR transgenic mice, exhibiting fatty liver even when fed with a chow diet, represent a novel, convenient, and reversible model of NAFLD/simple steatosis. We propose that AhR and its target CD36 may represent novel therapeutic targets to manage NAFLD. It is encouraging that substantial progresses have been made in the development and use of AhR antagonists.3,4

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steve Strom for providing primary human hepatocytes. We thank Dr. Christopher Bradfield for the AhR and Arnt expression vectors, and Dr. Yanan Tian for the pGud-Luc reporter gene.

Grant Support: This work was supported in part by NIH grants ES014626 and DK076962 to W.X. J.H was supported by an AHA Postdoctoral Fellowship 09POST2280546. Normal human hepatocytes were obtained through the Liver Tissue Cell Distribution System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, which was funded by NIH Contract #N01-DK-7-0004 / HHSN267200700004C.

Abbreviations

- ACC-1

acetyl CoA carboxylase 1

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- Arnt

aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator

- DRE

dioxin responsive element

- EMSA

eletrophoretic mobility shift assay

- FABP

fatty acid binding protein

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- FAT

fatty acid translocase

- FATP

fatty acid transporter protein

- FFA

free fatty acid

- FICZ

6-formylindolo [3,2-b]carbazole

- 3-MC

3-methylchoranethrene

- NAFLD

non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- SCD-1

stearoyl CoA desaturase-1

- TCDD

2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin

- VLDL

very low density lipoprotein

- WAT

white adipose tissue

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest disclosures: No conflicts of interest exist.

Author contributions: Study concept and design (JHL, MF, WX); acquisition of data (JHL, TW, MF, TM, MJL, JH); analysis and interpretation of data (JHL, MF, FJG, WX); drafting of the manuscript (JHL, WX); critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content (MF, FJG, WX); statistical analysis (JHL); obtained funding (WX).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hoffman EC, Reyes H, Chu FF, Sander F, et al. Cloning of a factor required for activity of the Ah (dioxin) receptor. Science. 1991;252:954–958. doi: 10.1126/science.1852076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reyes H, Reisz-Porszasz S, Hankinson O. Identification of the Ah receptor nuclear translocator protein (Arnt) as a component of the DNA binding form of the Ah receptor. Science. 1992;256:1193–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.256.5060.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beischlag TV, Luis Morales J, Hollingshead BD, et al. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor complex and the control of gene expression. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2008;18:207–250. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v18.i3.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen LP, Bradfield CA. The search for endogenous activators of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21:102–116. doi: 10.1021/tx7001965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandez-Salguero PM, Hilbert DM, Rudikoff S, Ward JM, et al. Aryl-hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice are resistant to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin-induced toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1996;140:173–179. doi: 10.1006/taap.1996.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt JV, Su GH, Reddy JK, et al. Characterization of a murine Ahr null allele: involvement of the Ah receptor in hepatic growth and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:6731–6736. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Salguero P, Pineau T, Hilbert DM, et al. Immune system impairment and hepatic fibrosis in mice lacking the dioxin-binding Ah receptor. Science. 1995;268:722–726. doi: 10.1126/science.7732381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lahvis GP, Lindell SL, Thomas RS, et al. Portosystemic shunting and persistent fetal vascular structures in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10442–104427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190256997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Postic C, Girard J. Contribution of de novo fatty acid synthesis to hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance: lessons from genetically engineered mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:829–838. doi: 10.1172/JCI34275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradbury MW. Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation I. Hepatic fatty acid uptake: possible role in steatosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G194–198. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00413.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greco D, Kotronen A, Westerbacka J, et al. Gene expression in human NAFLD. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G1281–1287. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00074.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg IJ, Ginsberg HN. Ins and outs modulating hepatic triglyceride and development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1343–1346. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy JK, Hashimoto T. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha: an adaptive metabolic system. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:193–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.21.1.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGuire J, Okamoto K, Whitelaw ML, et al. Definition of a dioxin receptor mutant that is a constitutive activator of transcription: delineation of overlapping repression and ligand binding functions within the PAS domain. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41841–41849. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105607200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Febbraio M, Abumrad NA, Hajjar DP, et al. A null mutation in murine CD36 reveals an important role in fatty acid and lipoprotein metabolism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19055–19062. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Zhai Y, Mu Y, et al. A novel pregnane X receptor-mediated and sterol regulatory element-binding protein-independent lipogenic pathway. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15013–15020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511116200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee JH, Gong H, Khadem S, et al. Androgen deprivation by activating the liver x receptor. Endocrinology. 2008;149:3778–3788. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wada T, Kang HS, Angers M, et al. Identification of oxysterol 7alpha-hydroxylase (Cyp7b1) as a novel retinoid-related orphan receptor alpha (RORalpha) (NR1F1) target gene and a functional cross-talk between RORalpha and liver X receptor (NR1H3) Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:891–899. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt JV, Bradfield CA. Ah receptor signaling pathways. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:55–89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lazarow PB, De Duve C. A fatty acyl-CoA oxidizing system in rat liver peroxisomes; enhancement by clofibrate, a hypolipidemic drug. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:2043–2046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.6.2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merkel M, Weinstock PH, Chajek-Shaul T, et al. Lipoprotein lipase expression exclusively in liver. A mouse model for metabolism in the neonatal period and during cachexia. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:893–901. doi: 10.1172/JCI2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boverhof DR, Burgoon LD, Tashiro C, et al. Comparative toxicogenomic analysis of the hepatotoxic effects of TCDD in Sprague Dawley rats and C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Sci. 2006;94:398–416. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfl100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adachi J, Mori Y, Matsui S, et al. Indirubin and indigo are potent aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands present in human urine. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:31475–31478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100238200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rannug U, Rannug A, Sjoberg U, Li H, et al. Structure elucidation of two tryptophan-derived, high affinity Ah receptor ligands. Chem Biol. 1995;2:841–845. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher EA, Ginsberg HN. Complexity in the secretory pathway: the assembly and secretion of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17377–17380. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R100068200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravikumar B, Carey PE, Snaar JE, et al. Real-time assessment of postprandial fat storage in liver and skeletal muscle in health and type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288:E789–797. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00557.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inoue M, Ohtake T, Motomura W, et al. Increased expression of PPARgamma in high fat diet-induced liver steatosis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;336:215–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Memon RA, Fuller J, Moser AH, et al. Regulation of putative fatty acid transporters and Acyl-CoA synthetase in liver and adipose tissue in ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 1999;48:121–127. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koonen DP, Jacobs RL, Febbraio M, et al. Increased hepatic CD36 expression contributes to dyslipidemia associated with diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2007;56:2863–2871. doi: 10.2337/db07-0907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou J, Febbraio M, Wada T, et al. Hepatic fatty acid transporter Cd36 is a common target of LXR, PXR, and PPARgamma in promoting steatosis. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:556–567. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao MS, Reddy JK. Peroxisomal beta-oxidation and steatohepatitis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:43–55. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green RM. NASH--hepatic metabolism and not simply the metabolic syndrome. Hepatology. 2003;38:14–17. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee CC, Yao YJ, Chen HL, et al. Fatty liver and hepatic function for residents with markedly high serum PCDD/Fs levels in Taiwan. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2006;69:367–380. doi: 10.1080/15287390500244972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.