Abstract

We examined whether exiting high school was associated with alterations in rates of change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors. Participants were 242 youth with ASD who had recently exited the school system and were part of our larger longitudinal study; data were collected at five time points over nearly 10 years. Results indicated overall improvement of autism symptoms and internalized behaviors over the study period, but slowing rates of improvement after exit. Youth who did not have an intellectual disability evidenced the greatest slowing in improvement. Lower family income was associated with less improvement. Our findings suggest that adult day activities may not be as intellectually stimulating as educational activities in school, reflected by less phenotypic improvement after exit.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder, transition to adulthood, maladaptive behaviors, autism symptoms

The rapid rise in the number of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) began in the early 1990’s (Gurney et al., 2003) and children from that generation are now beginning to exit the secondary school system. For youth with ASD, this transition is a time of change and uncertainty. At high school exit, they lose the entitlement to many (and sometimes all) of the services that they received while in school. In most cases, youth with ASD enter a world of adult services plagued by waiting lists and a dearth of appropriate opportunities to achieve a maximum level of adult independence (Howlin, Alcock, & Burkin, 2005). As more and more individuals with ASD continue to leave the school system and transition into the adult service world, it is critical to understand the factors that promote an optimal transition process.

The present study addresses these issues by examining changes in the autism behavioral phenotype before and after individuals with ASD exit the school system. Furthermore, we tested whether the impact of high school exit on the autism behavioral phenotype differed for those with and without an intellectual disability and for males versus females, as well as for those whose families had greater or lesser economic resources. Although there have been a few studies examining adult outcomes for individuals with ASD (for a review see Taylor, 2009), no previous study has followed the same individuals with ASD prospectively, starting before the transition out of the school system and continuing until after high school exit. These data are available in our ongoing longitudinal study (Lounds, Seltzer, Greenberg, & Shattuck, 2007; Seltzer et al., 2003), and thus we have the unprecedented opportunity to examine how individuals with ASD are impacted by this major life transition, as well as how individual and family characteristics affect these relations.

Change in the Autism Behavioral Phenotype during Adolescence and Adulthood

Autism symptoms

Consensus is beginning to emerge in the extant literature regarding the course of autism symptoms throughout adolescence and adulthood. Studies that have compared Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord, Rutter, & LeCouter, 1994) early childhood symptom ratings to “current” symptom ratings have generally found that parents report fewer symptoms in adolescence and adulthood than they recall when their child was very young (Fecteau, Mottron, Berthiaume, & Burack, 2003; McGovern & Sigman, 2005; Piven, Harper, Palmer, & Arndt, 1996; Seltzer et al., 2003). Clinical follow-up studies have also shown modest improvement in autism symptoms from early childhood to adulthood (Billstedt, Gillberg, & Gillberg, 2007; Howlin, Mawhood, & Rutter, 2000; Mawhood, Howlin, & Rutter, 2000).

In our ongoing research (Shattuck et al., 2007), we have examined change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors over a 4.5 year period for a broad age range of adolescents and adults with ASD (range from 10 years to 52 years). On average, we found that autism symptomotology improved over the study period, particularly for repetitive behaviors and stereotyped interests, impairments in social reciprocity, and impairments in verbal communication. Perhaps most importantly, relatively few adolescents and adults with ASD had symptoms that were worsening over time, ranging from 26% for non-verbal communication to 15% for social reciprocity. Improvements in autism symptoms were also observed over 3 years in a smaller sample of transition-aged, primarily co-residing youth with ASD by Lounds et al (2007). These patterns are consistent with Piven et al’s (1996) observation that “autism is a lifelong disorder whose features change with development.”

Maladaptive behaviors

Although not a part of the diagnostic criteria of ASD, maladaptive behaviors are often exhibited by people with ASD (Aman, Lam, Collier-Crespin, 2003; Hollander, Phillips, & Yeh, 2003; Lecavalier, 2006; Shea et al., 2004) and are a primary source of stress for their parents (Hastings, 2003; Hastings & Brown, 2002; Lecavalier, Leone, & Wiltz, 2006; Tomanik, Harris, & Hawkins, 2004). Maladaptive behaviors interfere with day-today functioning and include such behaviors as self-injury, aggression, and uncooperative behaviors. Concurrent with the improvements in autism symptoms, our research has found reduction of maladaptive behaviors during adolescence and adulthood (Lounds et al., 2007, Shattuck et al., 2007). Specifically, Shattuck and colleagues (2007) found that internalized, externalized, and asocial maladaptive behaviors became significantly less severe over 4.5 years for adolescents and adults with ASD. This pattern of improvement was also reported by Tonge and Einfeld (2003), who observed reductions in maladaptive behaviors over an 8-year period for children with autism.

The impact of high school transition

We conceptualize high school exit as an important “turning point” in the lives of individuals with ASD that may alter the trajectory of the autism behavioral phenotype over adolescence and early adulthood. In the life course developmental literature, turning points refer to any event that changes the direction of the life course relative to previously established trajectories (Wheaton & Gotlib, 1997), and they are often normative life events such as exiting high school. Leaving school represents a significant turning point for typically developing youth (Wheaton & Gotlib, 1997), and we expect alterations to the life course to be even greater for youth with ASD given the disparities between services provided to them in the secondary school system and in the adult service system.

Studies of individuals with intellectual disabilities (ID) point to the disruptive influence of transitions, or turning points, in behavioral phenotypic expression. Esbensen, Seltzer, and Krauss (2008) examined changes in the maladaptive behaviors of adults with ID before and after turning points such as moving out of the parental home or parental death. Both of these transitions were associated with a worsening of maladaptive behaviors in the years following the event. It is likely that for individuals with ASD, who tend to have difficulty with environmental change (Shea & Mesibov, 2005), high school exit may have a similarly disruptive effect on the trajectories of autism symptoms and behavior problems.

Correlates of the Autism Phenotype and Transition Outcomes

Intellectual disability

In order to elucidate the effects of high school exit for individuals with ASD, it is necessary to examine the factors that promote phenotypic improvement after exit. A handful of studies have predicted success in achieving adult independence (living independently, working without supports) after high school exit for individuals with ASD from variables measured earlier in the life course. Their results point to less independent adult outcomes for individuals who have comorbid ID compared to those with higher IQ scores (Eaves & Ho, 2008; Gillberg & Steffenburg, 1987; Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2004; Lord & Bailey, 2002). Comorbid ID is also related to greater severity of autism symptoms during adolescence and adulthood (Billstedt et al., 2007) and less improvement in autism symptoms over time (McGovern & Sigman, 2005; Shattuck et al., 2007). Therefore, we expected that individuals who had comorbid ID would display more severe symptoms and less improvement over time, both prior to high school exit and after, compared to those who did not have ID.

Gender

In general, studies find few differences in the autism behavioral phenotype in adulthood or adult outcomes based on the gender of the person with ASD. Billstedt and colleagues (2007) found that females with ASD had better quality social interactions than males, although gender was unrelated to reciprocal communication or limited patterns of self-chosen activities. However, Howlin and colleagues (2004) found no gender differences in autism symptoms or adult outcomes. Finally, Shattuck and colleagues (2007) did not find gender differences in degree of change in any subscales of autism symptoms or maladaptive behaviors. More research is clearly needed to determine the role of gender in phenotypic change as well as how males and females with ASD experience the transition out of high school and into adulthood.

Familial socio-economic resources

Another factor that may influence how the autism behavioral phenotype changes during the transition out of high school is family socio-economic resources. Although socio-economic status is understudied in ASD populations, there is some research that suggests that families who have greater socio-economic resources are able to better access services for their school-aged children with ASD. A recent large-sample survey (Thomas, Ellis, McLaurin, Daniels, & Morrissey, 2007) as well as a population-based study (Liptak et al., 2008) found that families of children with ASD who had higher annual incomes received a greater number of autism-related services and reported fewer barriers to service use. Parental education was also an important predictor of autism service use, with higher educated parents more likely to use the services of a neurologist compared to parents with less education (Thomas et al., 2007).

Although researchers have yet to examine the relations between parental socio-economic resources and the transition to adulthood in an autism sample, a study by Galambos, Barker, and Krahn (2006) of typically developing youth may provide insight into this association. They found that depression and expressed anger decreased faster from age 18 to 26 among typically developing youth from families with greater socio-economic resources compared to those from families with fewer socio-economic resources. The authors interpreted these findings as suggesting that more affluent parents were better able to financially assist their children in making the transition to adulthood, and the reduced depression and anger were a consequence of this smoother transition. Given the income disparities in autism services during childhood (Liptak et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2007), we expect that families with more socio-economic resources will have better access to services after their son or daughter exits high school, which will be related to greater reduction in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors after exit compared to families with fewer socio-economic resources.

The Present Study

The present study extends our previous work examining change in autism symptoms and behavior problems in two important ways. First, instead of examining change at two points in time separated by 4.5 years, as we did in Shattuck et al. (2007), we now have collected sufficient data to examine change over a nearly 10-year period. The present analyses use a multi-level modeling approach incorporating all five waves of data collected thus far over the study period. Using all of the data points makes it possible to capture more nuanced patterns of change over time than can be observed using change scores. More importantly, the present study focuses on change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors at a specific time in the development of individuals with ASD, namely, as they are transitioning out of high school and into the adult world. By first examining change in symptoms and behavior problems while individuals with ASD are in high school, and then testing whether the rate of change differs after high school exit, we can begin to understand how the autism behavioral phenotype is affected by this major turning point in development.

Therefore, our first aim was to determine whether exiting the secondary school system was associated with changes in slopes of autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors for adolescents and young adults with ASD. Based on our previous research with adults who have ID that has found that turning points, particularly transitioning out of the parental home or parental death, is associated with a worsening of maladaptive behaviors (Esbensen et al., 2008), we hypothesized that the transition out of high school would have a similar negative effect on changes in autism symptoms and behavior problems for individuals with ASD. Specifically, we expected the pattern of improvement in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors observed by Shattuck and colleagues (2007) and Lounds and colleagues (2007) to be attenuated in the years following high school exit.

Our second aim was to examine whether changes in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors, both prior to high school exit and after exit, depended on the gender or ID status of the adolescents and young adults with ASD or family socio-economic resources such as maternal education and family income. We expected greater attenuation in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors after high school exit for youth with ASD who did not have ID and whose families had greater socio-economic resources.

Method

Sample and Procedure

In the present analysis, we used a subsample (n = 242) drawn from our larger longitudinal study of families of adolescents and adults with ASD (N = 406; Seltzer et al., 2003; Shattuck et al., 2007). The criteria for inclusion in the larger study were that the son or daughter with ASD was age 10 or older (age range = 10 to 52 at the beginning of the study), had received an ASD diagnosis (autistic disorder, Asperger disorder, or pervasive developmental disorder) from an educational or health professional, and had a researcher-administered Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Lord et al., 1994) profile consistent with the diagnosis. Nearly all of the sample members (94.6%) met the ADI-R lifetime criteria for a diagnosis of autistic disorder. Case-by-case review of the other sample members (5.4%) determined that their ADI-R profile was consistent with their ASD diagnosis (i.e., meeting the cutoffs for reciprocal social interaction and repetitive behaviors for Asperger disorder, and for reciprocal social interaction and either impaired communication or repetitive behaviors for PDD-NOS). Half of the participants lived in Wisconsin (n = 202) and half in Massachusetts (n = 204). We used identical recruitment and data-collection methods at both sites. Families received information about the study through service agencies, schools, and clinics; those who were interested contacted a study coordinator and were subsequently enrolled. Five waves of data have thus far been collected: four waves collected every 18 months from 1998 to 2003, spanning a 4.5 year period, and a fifth wave collected in 2008, 10 years after the study began. At each time point, data were collected from the primary caregiver, who was usually the mother, via in-home interviews that typically lasted 2 to 3 hours and via self-administered questionnaires.

For the present analysis, we included families whose son or daughter with ASD exited high school at any of the study’s five data points or who remained in high school at the fifth point of data collection (note that depending on when a sample member exited high school during the study period, he or she may have contributed data to the slope before high school exit only, or the slopes before and after high school exit). By focusing on this sample, it was possible to examine change in autism symptoms and behavior problems during the transition to adulthood, an understudied period in the lives of individuals with ASD and their families. Of a possible 259 sample members who met the above inclusion criterion, there were 17 who were not included in the present analysis. In eight cases, the father was the respondent instead of the mother. In eight of the remaining families, mothers of individuals with ASD completed separate interviews for two children with ASD; we randomly chose one child from each family as the target child, resulting in the elimination of eight cases. Finally, one case was eliminated because the daughter was home schooled and was not receiving services through the school system. This resulted in a final sample of 242 mothers of transition-aged sons and daughter with ASD.

The adolescents and young adults with ASD included in this analysis averaged 16.3 years of age (SD = 3.1) when the study began (Time 1), with a range from 10.1 to 23.5 years. Three fourths (73.1%) were male and 80.6% were living with their parents at this time. Roughly 19% were reported to have a seizure disorder, and 76.4% of individuals were verbal, as indicated by daily functional use of at least three-word phrases. Nearly two thirds (63.2%) had comorbid ID. Thus, the characteristics of the present sample are consistent with what would be expected based on epidemiological studies of autistic disorder (Bryson & Smith, 1998; Fombonne, 2003).

At Time 1, the mothers in this subsample ranged from 32.3 years to 65.7 years of age (M = 45.9, SD = 5.8). Over half (56.6%) had attained at least a bachelor’s degree. Mothers were primarily married at Time 1 (85.5%) and 90.9% were Caucasian. Almost three fourths (72.7%) were employed, and the median household income was between $50,000 and $60,000.

All of the 242 sample members provided Time 1 data. Data were available for 217 families (89.7%) at Time 2, 214 (88.4%) at Time 3, 194 (80.2%) at Time 4, and 159 (65.7%) at Time 5. Mothers who remained in the study at Time 5 (n = 159) were compared on all of the study variables as well as indicators of socioeconomic status to those who dropped out of the study or those who died (or whose child died) prior to the most recent wave of measurement (n = 83). There were no significant differences between the groups in child’s gender, rates of comorbid ID, residential status, or child’s age, nor were there differences in maternal age, marital status, employment status or race. Furthermore, similar levels of Time 1 autism symptoms and behavior problems were reported for children of mothers who remained in the study at Time 5, compared to those who did not continue to participate. These overall patterns suggest similarity on a number of dimensions between mothers who continued to participate compared to those who did not; however, we did observe differences in two socio-economic status variables. Mothers who remained in the study had more years of education and higher household incomes than mothers who did not participate at Time 5, ts (240) = −2.35 and −3.69, respectively, ps < .05. Because of these group differences, education and income were included in all analyses that included between-persons covariates.

Measures

Outcome Variables

Autism symptoms

The ADI-R (Lord et al., 1994) measured current autism symptoms at all five times of measurement. Thirty-three items from the diagnostic algorithm appropriate for adolescents and adults were administered in interviews with mothers. Ratings of current functioning were made at each time of measurement by interviewers who had participated in an approved ADI-R training program. Inter-rater agreement between the interviewers and two supervising psychologists experienced in the diagnosis of autism and in the use of the ADI-R averaged 89% at Time 1, and the average Kappa was .81. Past research has demonstrated the test–retest reliability, diagnostic validity, convergent validity, and specificity and sensitivity of the items used in the ADI-R diagnostic algorithm (Hill et al., 2001; Lord et al., 1997). Each ADI-R item was scored on the following scale: 0 = no abnormality, 1 = possible abnormality, 2 = definite autistic-type abnormality, 3 = severe autistic-type abnormality.

We recoded each ADI-R item to reflect either no impairment (coded 0, corresponding to an ADI-R code of 0) or some degree of impairment (coded 1, corresponding to an ADI-R code of 1, 2, or 3). This coding strategy has been used previously (Fecteau et al., 2003; Lounds et al., 2007; Seltzer et al., 2003; Shattuck et al., 2007) and allowed us to capture the qualitative difference between having and not having a given autism symptom. Also, this coding strategy provides a conservative estimate of change, as an individual is identified as having improved on any given item only if he or she changed from symptomatic (an initial code of 1, 2, or 3) to asymptomatic functioning (a code of 0).

We created four ADI-R subscales – restricted repetitive behaviors and interests, reciprocal social interaction impairments, non-verbal communication impairments, and verbal communication impairments – based on consultation with one of the instrument’s designers (C. Lord). This grouping of items is based on the clustering of items established by the ADI-R scoring protocol (Lord et al., 1994), our prior work using this instrument (Shattuck et al., 2007), and analysis of the factor structure of the instrument (Lecavalier et al., 2006). A full listing of the items included in each subscale can be found in Shattuck and colleagues (2007). Scale scores were created by summing the number of items on which an individual was symptomatic. Verbal communication impairments scores were only available for those subjects who were verbal, as defined by daily functional use of phrases of three words or more.

Maladaptive behaviors

Mothers completed the Behavior Problems subscale of the Scales of Independent Behaviors – Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks, Woodcock, Weatherman, & Hill, 1996) at each of the 5 times of measurement. The Problem Behavior scale measures maladaptive behaviors, grouped in three domains (Bruininks et al., 1996): internalized behaviors (hurtful to self, unusual or repetitive habits, withdrawal or inattentive behavior), externalized behaviors (hurtful to others, destructive to property, disruptive behavior), and asocial behaviors (socially offensive behavior, uncooperative behavior). Mothers who indicated that their child displayed a given behavior then rated the frequency (1 = less than once a month to 5 = 1 more times/hour) and the severity (1 = not serious to 5 = extremely serious) of the behavior. Standardized algorithms (Bruininks et al., 1996) translate the frequency and severity ratings into subscale scores (internalized behaviors, externalized behaviors, and asocial behaviors). Higher scores indicate more severe maladaptive behaviors. Reliability and validity of this measure have been established by Bruininks et al. (1996).

Time-varying, Within-Persons Independent Variables

Time since high school exit

Detailed record review allowed for the determination of whether the son or daughter with ASD was in high school at each of the measurement times, as well as the date at which he or she left the school system. From this information, we calculated a variable indicating the amount of time that had passed since the person with ASD had exited high school at each data collection time point (coded as 0 when the son or daughter was still in high school). Some adolescents and young adults with ASD graduated with their peers but continued to receive services through the school system, while others never graduated but instead “timed out” of secondary school on their 22nd birthday. For clarity, the date of high school exit was defined as the month and year that the son or daughter stopped receiving services through the secondary school system (regardless of graduation date).

Residential status

At each time of measurement, mothers indicated where their adolescent or adult child lived. When the son or daughter lived at home a code of 0 (co-residing) was assigned. When the child lived away from the family home (e.g., group home, independent living, etc.) a code of 1 (living away from the family home) was assigned. This coding strategy allowed us to control for the effects of moving out of the parental home on autism symptoms and behavior problems when examining the impact of high school exit.

Between-Persons Independent Variables

At Time 1, the age and gender (0 = son, 1 = daughter) of the son or daughter with ASD was recorded. Mothers were also asked about their family’s income in the previous year, coded from 1 = less than $5,000 to 13 = over $70,000. The highest level of education that the mothers had completed was collected, coded on the following scale: 1 = high school graduate or less than high school; 2 = some college; 3 = associate or bachelor’s degree; 4 = post-bachelor’s education or graduate degree.

Comorbid intellectual disability status (0 = no intellectual disability, 1 = intellectual disability) was determined using a variety of sources. Standardized IQ was obtained by administering the Wide Range Intelligence Test (WRIT; Glutting, Adams, & Sheslow, 2000) to 50.2% of the individuals with ASD. The WRIT is a brief measure with strong psychometric properties and both verbal and nonverbal sections. Adaptive behavior was assessed by administering the Vineland Screener (Sparrow, Carter, & Cicchetti, 1993) to mothers. The 45-item screener measured daily living skills in the youth with ASD and correlates well with the full-scale Vineland score (r = .87 to .98). It has higher interrater reliability (r = .98) and good external validity (Sparrow et al., 1993). Individuals with standard scores of 70 or below on both IQ and adaptive behavior measures were classified as having an intellectual disability (ID), consistent with diagnostic guidelines (Luckasson et al., 2002). For cases where the individual with ASD scored above 70 on either measure, or for whom either of the measures was missing, a review of records by three psychologists, combined with a clinical consensus procedure, was used to determine ID status.

Data Analysis

Multilevel modeling, using the Hierarchical Linear Modeling program (HLM; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002), was the primary method of data analysis used to examine change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors. Multilevel modeling has several advantages over more traditional ways to study change; one advantage that is especially salient for longitudinal research is its ability to flexibly handle missing data. As long as one occasion of measurement is available, the case can be used in the estimation of effects. However, individuals who have more data points yield more reliable estimates, which are weighted more heavily in the group mean estimates than individuals who have fewer time points (Bryk & Raudenbush, 1987; Francis, Fletcher, Steubing, Davidson, & Thompson, 1991). Furthermore, multilevel modeling allows for the measurement periods to be unequally spaced. This flexibility is especially beneficial when examining the amount of time that has passed since the son or daughter with ASD exited secondary school; in some cases the person with autism exited within a month prior to the measurement occasion, whereas in other cases they exited a year or more before the subsequent time point of measurement. Multilevel modeling allows us to accurately represent the individual variability in the amount of time that has passed since high school exit (as well as individual variability in timing of measurement occasions). Finally, the inclusion of observed predictors of attrition in the models (maternal education and family income) and the use of all available time points for participants reduces bias (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Singer & Willett, 2003).

In order to address the first research aim, examining the average effect of high school exit on changes in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors, a set of “unconditional” models were estimated that included only the two main Level 1 (within-persons) time variables: the amount of time that had passed since the start of the study; and the amount of time that had passed since high school exit. Seven separate models were run, one for each of the autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors subscales, resulting in an initial score for each variable, a slope reflecting rate of change prior to high school exit, and a slope reflecting the difference in rate of change after high school exit (Singer & Willett, 2003). After determining slopes, these models were re-estimated controlling for residential status at each time point as a time-varying covariate. Controlling for this variable allowed us to determine whether differences in the trajectory of autism symptoms or maladaptive behaviors after high school exit could be accounted for by changes in residential status (i.e., adolescents and young adults with ASD moving out of the parental home) at this time.

The second research aim addressed whether changes in autism symptoms or maladaptive behaviors, either prior to or after high school exit, depended on the age, gender, or ID status of the adolescents and young adults with ASD, maternal education, or family income. In a second set of models, those between-persons (Level 2) variables were included to determine whether they had an impact on symptoms or behaviors at the start of the study (intercept), on rates of change in autism symptoms or maladaptive behaviors prior to high school exit (time slope), or on differences in rates of change of symptoms or behaviors after high school exit (change in slope after exit). Although age was not one of our hypothesized between-persons variables, we added it as a control due to the relatively wide age range of the sample at Time 1 (10.1 to 23.5 years). Residential status at each time point was controlled in the second set of models. Dichotomous predictors were centered at 0 (e.g., female = .5 and male = −.5) and continuous variables (maternal education, income and age of the son or daughter) were grand mean centered.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Means and standard deviations for each of the dependent variables at each time point are presented in Table 1. Visual examination of the means suggested that autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors were improving (i.e., reducing in severity) over time. Furthermore, fewer young adults with ASD were living with their families over the study period, which was related to exiting the school system. Specifically, at each time point, over 80% of young adults with ASD who were still in high school were living in the parental home or with family, compared to approximately 60% of young adults who had exited. Most of the young adults who were still in high school but not co-residing were living in community residences, residential schools, or institutional settings. Those who had exited and were not co-residing tended to mainly be living in community residences. Very few young adults were living independently, ranging from one young adult at Time 1 to nine at Time 5.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Within-Persons Variables by Wave of Measurement

| Variable | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Outcomes | ||||||||||

| Autism Symptoms | ||||||||||

| Repetitive Behaviors | 4.33 | 1.74 | 3.81 | 1.71 | 3.85 | 1.89 | 3.45 | 1.88 | 3.42 | 1.80 |

| Social Reciprocity | 7.94 | 2.41 | 7.81 | 2.44 | 7.39 | 2.76 | 6.88 | 2.96 | 7.25 | 3.01 |

| Non-Verbal Communication | 2.98 | 1.22 | 2.91 | 1.24 | 2.94 | 1.23 | 2.75 | 1.31 | 2.99 | 1.33 |

| Verbal Communication | 3.73 | 1.33 | 3.69 | 1.41 | 3.51 | 1.49 | 3.29 | 1.48 | 3.10 | 1.55 |

| Maladaptive Behaviors | ||||||||||

| Internalized Behaviors | 117.31 | 10.69 | 114.31 | 9.88 | 114.42 | 10.54 | 112.61 | 11.02 | 112.25 | 11.44 |

| Externalized Behaviors | 107.40 | 12.19 | 107.83 | 10.64 | 106.16 | 10.75 | 105.74 | 11.23 | 104.30 | 9.82 |

| Asocial Behaviors | 113.45 | 12.76 | 113.61 | 12.15 | 111.52 | 12.15 | 109.34 | 11.73 | 108.14 | 10.78 |

| Time-Varying Covariate | ||||||||||

| Proportion Living Outside of Parental Home | .19 | .40 | .22 | .41 | .25 | .44 | .34 | .47 | .47 | .50 |

| Total N for Dependent Variables | 242–235 | 213–209 | 210–201 | 195–180 | 158–146 | |||||

| Total N for Verbal Communication (only verbal participants) | 185 | 168 | 148 | 123 | 116 | |||||

Correlations within each construct over time ranged from .68 (Time 2 to Time 3 externalized behaviors) to .29 (Time 1 to Time 5 repetitive behaviors); these data are available from the first author. In general, the within-construct correlations were as expected, with measurements taken closer together in time being more highly correlated than measurements taken further apart. Repetitive behaviors, social reciprocity, and verbal communication symptoms were moderately correlated with maladaptive behaviors subdomains, with coefficients ranging from .12 to 46. Non-verbal communication was not correlated with maladaptive behaviors.

Unconditional Growth Models

For all growth models, time relative to the start of the study was coded as the number of years since the initial time point for each sample member based on the exact date of measurement. Time 1 was coded as 0, the mean for Time 2 was 1.62 years (range from .5 to 2.33), the mean for Time 3 was 3.18 (range from 2.08 to 4.00), the mean for Time 4 was 4.75 (range from 3.92 to 6.01), and the mean for Time 5 was 8.60 (range from 7.50 to 9.59). An additional time variable – the number of years since high school exit – was also included in these models. At Time 1, 20 young adults with ASD had exited high school within the previous 18 months and therefore they had data for the number of years after exit at all time points. An additional 27 young adults with ASD left high school between Time 1 and Time 2, 26 left between Time 2 and Time 3, 24 left between Time 3 and Time 4, and 49 young adults exited high school between Time 4 and Time 5. For all time points before high school exit for each individual, the time since exit variable was coded as 0. For all time points after high school exit for each individual, the exit date was subtracted from the date of data collection to indicate the number of years that had passed since exit. These growth curve models estimate three parameters: autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors at Time 1 (intercept), slopes of symptoms and behaviors prior to high school exit, and changes in slopes of symptoms and behaviors after high school exit.

Autism symptoms

Results of the four unconditional growth models, which allow us to estimate the average change of autism symptoms for the sample prior to and after high school exit, are presented in Table 2. All four subscale scores significantly improved, on average, prior to high school exit, Bs = −.14 for repetitive behaviors, −.18 for social reciprocity, −.05 for non-verbal communication, and −.10 for verbal communication, ps < .01. However, for all autism symptoms scores except verbal communication impairments, improvement significantly slowed after high school exit, Bs = .08 for repetitive behaviors, .11 for social reciprocity, and .07 for non-verbal communication, ps < .05. Specifically, improvement in repetitive behaviors slowed from .14 points per year to .06 (−.14 + .08) points per year, and improvement in social reciprocity impairments slowed from .18 to .07 (−.18 + .11) points per year. Non-verbal communication impairments changed from improving at .05 points per year prior to high school exit to getting worse over time, after exit, at a rate of .02 points per year (−.05 + .07).

Table 2.

Multilevel Growth Models of Rates of Change before High School Exit and Rates of Change after Exit in Autism Symptoms and Maladaptive Behaviors

| Autism Symptoms | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repetitive Behaviors (n=242) | Social Reciprocity (n=242) | Non-Verbal Communication (n=242) | Verbal Communication (n=193) | |||||

| Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | |

| Initial Status | 4.16** | .10 | 7.88** | .14 | 2.97** | .07 | 3.75** | .09 |

| Intercept (Random) Slope Prior to High School Exit (Random) | −.14** | .03 | −.18** | .04 | −.05** | .01 | −.10** | .02 |

| Change in Slope After High School Exit (Random) | .08* | .04 | .11* | .06 | .07** | .02 | .04 | .04 |

| Maladaptive Behaviors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internalized (n=240) | Externalized (n=242) | Asocial (n=242) | ||||||

| Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | |||

| Initial Status | 116.52** | .62 | 107.72** | .71 | 113.65** | .76 | ||

| Intercept (Random) Slope Prior to High School Exit (Random) | −.82** | .14 | −.40** | .14 | −.80** | .16 | ||

| Change in Slope After High School Exit (Random) | .51* | .21 | −.03 | .23 | .20 | .24 | ||

p < .05

p < .01

Maladaptive behaviors

Results of the three unconditional growth models for maladaptive behaviors are also presented in Table 2. On average, maladaptive behaviors prior to high school exit were improving over time for all three subscales, Bs = −.82, −.40, and −.80 for internalized, externalized, and asocial behaviors, respectively, ps < .01. Non-significant coefficients for changes in slope after high school exit for externalized behaviors and asocial behaviors suggest that, on average, there was no statistically significant attenuation in improvement after high school exit. However, improvement in internalized maladaptive behaviors slowed significantly after high school exit. Prior to exit, internalized behaviors were improving at a rate of .82 points per year, whereas after exit the rate of this improvement was reduced by over one-half, improving by .31 (−.82 + .51) points per year.

Controlling for Moving out of the Parental Home

For some young adults with ASD, moving out of the parental home occurs concurrent with exiting the secondary school system. We hypothesized that the slowing in improvement in autism symptoms and internalized behaviors after high school exit may be accounted for by moving out of the parental home. That is, it may be that changing living arrangements, and not exiting high school per se, accounts for the attenuation of improvement in symptoms and behaviors. In order to test this hypothesis, we re-estimated the unconditional models, with the inclusion of residential status (living in the home or out of the home) at each time point as a fixed time-varying covariate. If change in residential status was responsible for the reduction in improvement, then controlling for placement over time would explain the change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors, resulting in a non-significant change in slope after exit. However, this was not the case; all of the changes in slope after high school exit that were statistically significant in the prior set of models remained so, suggesting that the attenuation of improvement was not merely a result of change in residential status (data available from the first author).

Adding Between-Persons Variables

In the next series of models, the effects of between-persons (Level 2) covariates on initial status and change in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors were tested. Seven separate models were run, one for each subscale of autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors. Adding the between-persons variables into the models allowed us to examine three questions: (1) Do the Time 1 scores of autism symptoms or maladaptive behaviors depend on ID status, child age and gender, maternal education, or family income? (2) Do changes over time in symptoms or behaviors, prior to high school exit, depend on ID status, child age and gender, maternal education, or family income? (3) Do any differences in change after high school exit depend on these same between-subjects variables? Finally, residential status at each time point was controlled by entering it into the models as a fixed, time-varying predictor.

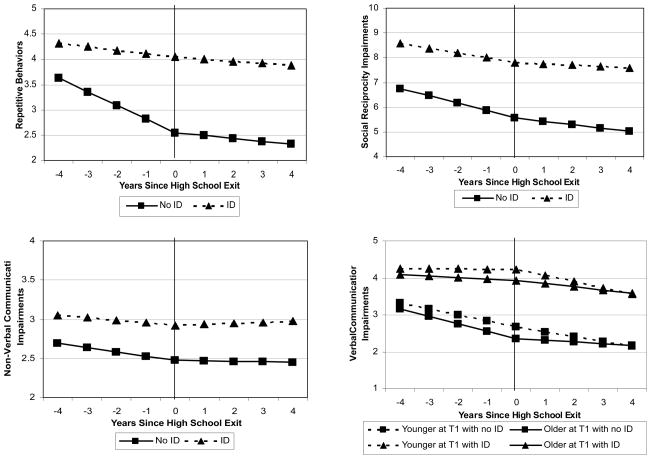

Autism symptoms

Table 3 presents the coefficients and standard errors for the prediction of autism symptoms from the multilevel models that included between-persons factors. These conditional growth curve models are plotted in Figure 1, which depicts the effects of statistically significant between-persons factors for each subscale. For repetitive behaviors, ID status predicted initial levels of symptoms, change in symptoms prior to high school exit, as well as change in slope of symptoms after exit. Individuals who did not have ID had fewer repetitive behaviors at the start of the study and repetitive behaviors that were improving more while in high school (.27 points/year), compared to those with comorbid ID (.07 points/year). However, for these young adults with ASD without ID, improvement in repetitive behaviors attenuated significantly after high school exit, B = .21, SE = .08, p < .05, with a rate of change after exit of .06 points/year. In contrast, for those with comorbid ID, exiting high school did not significantly change their rate of improvement in repetitive behaviors over time (change from .07 points/year to .04 points/year), B = .03, SE = .08, p = ns.

Table 3.

Multilevel Models of Between Group Effects of Intellectual Disability Status, Child Age, Child Gender, and Family Income on Initial Status and Rates of Change (Pre-Exit and Post-Exit) of Autism Symptoms

| Repetitive Behaviors |

Social Reciprocity |

Non-Verbal Communication |

Verbal Communication |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | |

| Initial Status Intercept (Random) | 3.97** | .14 | 7.67** | .18 | 2.87** | .09 | 3.70** | .10 |

| Intellectual Disability | .69** | .21 | 1.82** | .29 | .36* | .15 | .93** | .18 |

| Child Age | .01 | .03 | .04 | .04 | .02 | .02 | −.04 | .03 |

| Daughter | −.22 | .24 | .15 | .31 | −.15 | .16 | .08 | .19 |

| Maternal Education | .03 | .08 | .03 | .12 | .09 | .06 | .01 | .08 |

| Family Income | −.03 | .03 | .08 | .05 | .00 | .02 | .01 | .03 |

| Slope Prior to High School Exit (Random) | −.17** | .05 | −.25** | .06 | −.04 | .03 | −.11** | .03 |

| Intellectual Disability | .20** | .06 | .11 | .08 | .02 | .03 | .16** | .05 |

| Child Age | −.01 | .01 | −.02 | .02 | .00 | .01 | −.01 | .01 |

| Daughter | .09 | .06 | −.08 | .09 | .01 | .03 | .00 | .05 |

| Maternal Education | .01 | .02 | −.01 | .03 | .01 | .01 | −.03 | .02 |

| Family Income | .00 | .01 | −.00 | .01 | −.01 | .01 | .01 | .01 |

| Change in Slope After High School Exit (Random) | .12 | .07 | .15 | .10 | .05 | .05 | .01 | .06 |

| Intellectual Disability | −.19* | .08 | −.02 | .11 | −.00 | .06 | −.19** | .07 |

| Child Age | .01 | .01 | .01 | .02 | −.00 | .01 | .03* | .01 |

| Daughter | −.17 | .09 | −.07 | .12 | −.06 | .06 | −.03 | .07 |

| Maternal Education | −.02 | .03 | .05 | .05 | .00 | .02 | .06 | .03 |

| Family Income | −.02 | .01 | −.01 | .02 | .00 | .01 | −.02 | .01 |

| Lives Outside Parental Home (Fixed Slope) | −.20 | .18 | −.06 | .26 | −.03 | .11 | −.04 | .12 |

p < .05

p < .01

Figure 1.

Conditional growth curve models for autism symptom subscales. Statistically significant between-persons covariates are depicted for each subscale. For all subscales, triangles represent those with ASD and comorbid intellectual disability and squares represent those without intellectual disability. For verbal communication impairments (bottom right panel), dotted lines represent those who were younger at Time 1 (around 14 years old) and solid lines represent those who were older at Time 1 (around 18 years old).

A similar pattern was observed for impairments in verbal communication, although in addition to ID status predicting all 3 parameters (initial status, slope prior to high school exit, and change in slope after high school exit), the child’s age at the start of the study predicted change in rate of improvement after exiting high school. Improvement in verbal communication continued after high school exit for those who were younger at the start of the study. For those who were older, improvement slowed after exit, particularly for those who did not have comorbid ID.

Although ID status predicted the Time 1 scores of social reciprocity and non-verbal communication impairments, none of the between-subjects variables predicted change in these autism subscales (either before or after high school exit). This suggests that the slowing in improvement in social reciprocity and non-verbal communication after high school exit (see Table 2) was not significantly affected by disability status, child’s age, gender, maternal education, or family income.

Maladaptive behaviors

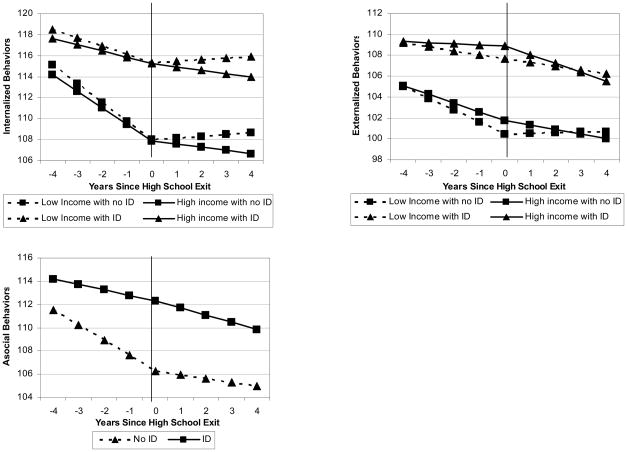

Table 4 presents the coefficients and standard errors for the prediction of maladaptive behaviors from the multilevel models that included between-persons factors. These conditional growth curve models are plotted in Figure 2, which depicts the effects of statistically significant between-persons factors for each subscale. ID status significantly predicted initial status for both internalized and externalized behaviors, and predicted change both prior to and after high school exit for all three maladaptive behaviors subscales. Adolescents and young adults without ID had fewer internalized behaviors at Time 1, and they were improving more rapidly while in high school (1.71 pts/year) relative to youth with ASD and an intellectual disability (.72 points/year). However, for both those with and without ID, improvement in internalized behaviors essentially stopped after high school exit, slowing to .01 points for year.

Table 4.

Multilevel Models of Between Group Effects of Intellectual Disability Status, Child Age, Child Gender, and Family Income on Initial Status and Rates of Change (Pre-Exit and Post-Exit) of Maladaptive Behaviors

| Internalized |

Externalized |

Asocial |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | Coefficient | S.E. | |

| Initial Status Intercept (Random) | 116.50** | .83 | 107.12** | .86 | 112.87** | 1.00 |

| Intellectual Disability | 3.43** | 1.30 | 4.21** | 1.50 | 2.68 | 1.72 |

| Child Age | −.16 | .20 | .11 | .22 | .13 | .24 |

| Daughter | .67 | 1.46 | −.30 | 1.55 | .32 | 1.65 |

| Maternal Education | .76 | .56 | .65 | .66 | .97 | .74 |

| Family Income | −.22 | .21 | .03 | .25 | −.18 | .29 |

| Slope Prior to High School Exit (Random) | −1.22** | .21 | −.66** | .22 | −.89** | .25 |

| Intellectual Disability | .99** | .26 | .74* | .31 | .83* | .35 |

| Child Age | −.07 | .06 | −.04 | .06 | −.00 | .07 |

| Daughter | .07 | .29 | −.14 | .31 | .25 | .33 |

| Maternal Education | .09 | .13 | .05 | .13 | .10 | .15 |

| Family Income | .05 | .05 | .07 | .05 | .03 | .06 |

| Change in Slope After High School Exit (Random) | 1.21** | .34 | .34 | .37 | .42 | .41 |

| Intellectual Disability | −1.01* | .41 | −1.16* | .48 | −1.11* | .52 |

| Child Age | .02 | .08 | .06 | .09 | −.02 | .09 |

| Daughter | .27 | .44 | .30 | .49 | −.54 | .51 |

| Maternal Education | −.03 | .18 | .06 | .18 | .04 | .20 |

| Family Income | −.17* | .08 | −.19* | .08 | −.09 | .09 |

| Lives Outside Parental Home (Fixed Slope) | .41 | 1.01 | −.03 | 1.00 | −1.82 | 1.03 |

p < .05

p < .01

Figure 2.

Conditional growth curve models for maladaptive behavior subscales. Statistically significant between-persons covariates are depicted for each subscale. For internalized (top left panel) and externalized (top right panel) behaviors, dotted lines represent those from lower income families (25th percentile or $40,000 to $45,000/year) and solid lines represent those from higher income families (75th percentile or over $70,000/year). For all subscales, triangles represent those with ASD and comorbid intellectual disability and squares represent those without intellectual disability

Youth without ID also had fewer externalized behaviors at Time 1, and behaviors that improved more rapidly while in high school (1.03 points/year) relative to those with comorbid ID (.29 points/year). After exit, change was reduced to .11 points/year for those without ID, whereas improvement became more pronounced (.53 points/year) for those with comorbid ID. A similar pattern was observed for asocial behaviors.

There was a significant effect of family income on change in internalized and externalized behaviors after high school exit. Figure 2 depicts the change in internalized and externalized behaviors, respectively, for families with lower incomes for this sample (income at the 25th percentile or $40,000 to $45,000 per year) and higher incomes for this sample (income at the 75th percentile or over $70,000 per year). For those adolescents and young adults whose families had higher incomes, internalized and externalized behaviors after exit improved more over time relative to those whose families had lower incomes. Interestingly, family income only impacted change in maladaptive behaviors after high school exit, but not initial levels of behaviors or behaviors while the son or daughter with ASD was in the school system

Discussion

This study is the first to shed light on how exiting high school – an important turning point in the lives of all youth including those with ASD – impacts the autism behavioral phenotype. Our results are cause for concern. Although autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors were generally improving while adolescents and young adults with ASD were in the secondary school system, improvement slowed significantly after high school exit for internalizing behaviors and all but one of the autism symptoms subdomains. For each of these subscales, the rate of improvement in symptoms and behaviors was reduced by over one-half after high school exit. Our findings are consistent with previous research examining the impact of turning points for adults with ID (Esbensen et al., 2008). Parental death and moving out of the parental home was associated with increased maladaptive behaviors for adults with ID; it appears the exiting high school has a disruptive effect in behavioral phenotypic improvement for youth with ASD.

Although there are a number of possible explanations for the slowing in improvement at high school exit, such as slowing of cognitive development or hormonal changes during this time, we find changes in disability-related services the most compelling prospect. In addition to the disruptive effects of changing from school to adult day activities, it is possible that the slowing of improvement in the autism behavioral phenotype following high school exit is reflective of the less stimulating adult occupational and day activities than those experienced in school. Supporting this interpretation, Shepperdson (1995) found that adolescents with Down syndrome who had less stimulating home environments had poorer language ability and social competence scores.

Contrary to our hypotheses, the most pronounced slowing of improvement after high school exit was observed for young adults with ASD who did not have ID. This stood in contrast to behavioral phenotypic change while these youth were in high school. Consistent with our previous research (Shattuck et al., 2007), those with ASD who did not have ID improved more in both autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors while they were in high school compared to those with comorbid ID. After high school exit, however, improvement in symptoms and behaviors slowed more for those without ID, with trajectories that appeared similar to youth with comorbid ID. This suggests that for youth without comorbid ID, high school exit appeared to have a more pronounced influence on their autism symptoms and behavior problems over time.

The disruptive influence of high school exit for young adults without ID may be related to difficulties finding appropriate educational and occupational activities after exit. Taylor and Seltzer (under review) found that nearly three-fourths (74%) of young adults with ASD and comorbid ID were receiving adult day services in the years immediately following high school exit compared to only 6% of those without ID. Furthermore, over one-quarter of young adults with ASD without ID had no occupational, educational, or day activities at this time, a percentage that was over three times greater than youths with comorbid ID. In sum, it appears that the adult service system may not provide adequate opportunities for adults with ASD who do not have comorbid ID to achieve maximum levels of independence and find employment activities appropriate to their interests and level of functioning. The lack of stimulating activities after exit may be at least in part responsible for the slowing of improvement of the autism behavioral phenotype observed while these youth were in high school. Future research should explore this issue directly by examining the relations between appropriate, stimulating adult daytime employment and activities and changes in the behavior phenotype from before to after high school exit.

If the relations between high school exit and slowing improvement are indeed due to an inadequacy of services after exit, findings from the present study would have important implications for developing more effective adult services and stimulating job opportunities for youth with ASD – particularly those without ID. Although there are a handful of model programs that include services for transition-aged youth with ASD without ID (such as the Kelly Autism Program at Western Kentucky University), these programs are inaccessible to the majority of families. Employment-related programs that consider the interests and specific needs of all youth with ASD, and that provide appropriate and meaningful supports to those without ID may encourage continued phenotypic improvement after these youth exit high school.

Our analyses also suggest that improvement in maladaptive behavior slows more for those young adults with ASD whose families have lower incomes compared to families with higher incomes. Although lower socio-economic status (SES) is an important and well-identified risk factor for poor physical and psychological health among the general population (Marmot, Ryff, Bumpass, Shipley, Marks 1997; Ryff & Singer, 1998), it has largely been overlooked in studies of individuals with ASD and their families. The few studies that have examine the impact of SES in autism samples find that families who have lower incomes or less parental education have less access to autism-related services in early childhood than families who have more socio-economic resources (Liptak et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2007). Therefore, our findings of slowed improvement in maladaptive behaviors after high school exit for those from lower income families may reflect an income disparity in the availability and quality of adult services.

Perhaps most interesting, family income was unrelated to initial severity of maladaptive behaviors or improvement in maladaptive behaviors while individuals with ASD were in the secondary school system – income was instead only related to change after high school exit. This may indicate some degree of success of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), which mandates appropriate educational services for all school-aged children with disabilities. Assuming that better services are related to behavioral phenotypic improvement, the lack of relations between income and improvement while in high school may reflect autism services through the school system that differ little based on parental SES. Following this line of reasoning, however, also suggests that income may have a large effect on service availability after youth with ASD exit the school system. Higher parental income has been shown to “smooth the way” for typically developing youth who are transitioning to adulthood (Galambos et al., 2006) and future research should study whether higher parental income also promotes a smoother transition to adulthood for young adults with ASD.

Not only do our findings have important implications for individuals with ASD who are transitioning out of the school system and their subsequent adult services, but also for their families during this time. Although research findings are mixed regarding the relations between autism symptoms and family well-being (Benson, 2006; Tobing & Glenwick, 2002), a well-established body of research suggests that maladaptive behaviors are among the most difficult aspects of caring for a son or daughter with ASD (Hastings, 2003; Hastings & Brown, 2002; Tomanik et al., 2004; Lecavalier et al., 2006). Families may have become accustomed to improvement in maladaptive behaviors while their son or daughter was in the secondary school system, and slowing of improvement after high school exit occurs at the same time that parents begin assuming the role of service coordinator for their son or daughter (Howlin, 2005). The situation becomes potentially more serious when considering that all of this change is occurring among families that tend to be more stressed throughout the life course than families of children with any other developmental disorder (Bouma & Schweitzer, 1990; Donovan, 1988; Dumas, Wolf, Fisman, & Culligan, 1991; Holroyd & McArthur, 1976; Rodrigue, Morgan, & Geffken, 1990; Wolf, Noh, Fisman, & Speechley, 1989). Therefore, future research should consider how exiting high school impacts the well-being of families of transition-aged youth with ASD.

There are three limitations to the present study that are worth noting. First, the sample in the larger study was a volunteer sample, most of the sample members were Caucasian, and the sample was skewed toward those with higher SES. These factors place limits on the generalizability of the results to non-White and lower SES populations. Second, because this was not an experimental study, it is impossible to determine whether exiting high school is the causal factor in symptom and behavior change. Although we ruled out moving from the parental home concurrent with exit as a competing explanation, there could be a number of other factors associated with this developmental stage (e.g., slowing of cognitive development, hormonal changes) causing slowing in improvement of the autism behavioral phenotype. Finally, we were unable to examine the quality of services within the school system or after high school exit in relation to change in the autism behavioral phenotype. It may be that those young adults who received high quality services while in school and lower quality services after exit may experience more phenotypic change compared to young adults who receive higher quality services both before and after high school exit.

These limitations are offset by a number of strengths. This is the first longitudinal study to follow adolescents and young adults with ASD from before to after high school exit, allowing us to prospectively examine how this turning point is associated with behavioral functioning. Although there are limits to its generalizeability, our sample was relatively large and recruited from the community, making our findings more generalizeable than many other studies of individuals with ASD. Finally, this is the first empirical study to suggest that exiting high school is a disruptive influence in the lives of youth with ASD. Because we know that the transition out of high school does not happen in a vacuum, future research should integrate multiple levels of analysis such as change in biological functioning, services, and family functioning in order to fully understand how individuals with ASD experience the transition out of high school and into adulthood.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Marino Autism Research Institute (J.L. Taylor, PI), the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG08768, M.M. Seltzer, PI) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P30 HD15052, E.M. Dykens, PI: P30 HD03352, M.M. Seltzer PI). We are grateful to Erin Barker for statistical consultation and Dan Bolt for his comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

Contributor Information

Julie Lounds Taylor, Vanderbilt Kennedy Center, Department of Pediatrics, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and the Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital at Vanderbilt, Nashville, TN, USA.

Marsha Mailick Seltzer, Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA.

References

- Aman MG, Lam KSL, Collier-Crespin A. Prevalence and patterns of use of psychoactive medicines among individuals with autism in the Autism Society of Ohio. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:527–534. doi: 10.1023/a:1025883612879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PR. The impact of child symptom severity on depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: The mediating role of stress proliferation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:685–695. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt E, Gillberg IC, Gillberg C. Autism in adults: symptom patterns and early childhood predictors. Use of the DISCO in a community sample followed since childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48:1102–1110. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01774.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouma R, Schweitzer R. The impact of chronic childhood illness of family stress: A comparison between autism and cystic fibrosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;46:722–730. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199011)46:6<722::aid-jclp2270460605>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruininks RH, Woodcock RW, Weatherman RF, Hill BK. Scales of Independent Behavior Revised. Rolling Meadows IL: Riverside Publishing; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson SE, Smith IM. Epidemiology of autism: Prevalence, associated characteristics, and implications for research and service delivery. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews. 1998;4:97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bryk AS, Raudenbush SW. Application of hierarchical linear models to assessing change. Psychological Bulletin. 1987;101:147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan AM. Family stress and ways of coping with adolescents who have handicaps: Maternal perceptions. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 1988;92:502–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumas JE, Wolf LC, Fisman SN, Culligan A. Parenting stress, child behavior problems, and dysphoria in parents of children with autism, Down syndrome, behavior disorders, and normal development. Exceptionality. 1991;2:97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Eaves LC, Ho HH. Young adult outcomes of autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008;38:739–747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-007-0441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbensen AJ, Seltzer MM, Krauss MW. Stability and change in health, functional abilities, and behavior problems among adults with and without Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2008;113:263–277. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2008)113[263:SACIHF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fecteau S, Mottron L, Berthiaume C, Burack JA. Developmental changes of autistic symptoms. Autism. 2003;7:255–268. doi: 10.1177/1362361303007003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Epidemiological surveys of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders: An update. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:365–382. doi: 10.1023/a:1025054610557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DJ, Fletcher JM, Stuebing KK, Davidson KC, Thompson NM. Analysis of change: Modeling individual growth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:27–37. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NL, Barker ET, Krahn HJ. Depression, self-esteem, and anger in emerging adulthood: Seven-year trajectories. Developmental Psychology. 2006;42:350–365. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C, Steffenburg S. Outcome and prognostic factors in infantile autism and similar conditions: A population-based study of 46 cases followed through puberty. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1987;17:273–287. doi: 10.1007/BF01495061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glutting JJ, Adams W, Sheslow D. Wide Range Intelligence Test. Wilmington, DE: Wide Range; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Gurney JG, Fritz MS, Ness KK, Sievers P, Newschaffer CJ, Shapiro EG. Analysis of prevalence trends of autism spectrum disorder in Minnesota. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2003;157:622–627. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.7.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP. Child behaviour problems and partner mental health as correlates of stress in mothers and fathers of children with autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2003;47:231–237. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Brown T. Behavior problems of children with autism, parental self-efficacy, and mental health. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2002;107:222–232. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2002)107<0222:BPOCWA>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A, Bolte S, Petrova G, Beltcheva D, Tacheva S, Poustka F. Stability and interpersonal agreement of the interview based diagnosis of autism. Psychopathology. 2001;34:187–191. doi: 10.1159/000049305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander E, Phillips AT, Yeh CC. Targeted treatments for symptom domains in child and adolescent autism. Lancet. 2003;362:732–734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14236-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd J, McArthur D. Mental retardation and stress on the parents: A contrast between Down’s syndrome and childhood autism. American Journal on Mental Deficiency. 1976;80:431–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P. Outcomes in autism spectrum disorders. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen D, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders, Vol. 1: Diagnosis, development, neurobiology, and behavior. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. pp. 201–220. [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Alcock J, Burkin C. An 8 year follow-up of a specialist supported employment service for high-ability adults with autism or Asperger syndrome. Autism. 2005;9:533–549. doi: 10.1177/1362361305057871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M. Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Mawhood L, Rutter M. Autism and developmental receptive language disorder A follow-up comparison in early adult. II: Social, behavioural, and psychiatric outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:561–578. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L. Behavioral and emotional problems in young people with pervasive developmental disorders: Relative prevalence, effects of subject characteristics, and empirical classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006;36:1101–1114. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecavalier L, Leone S, Wiltz J. The impact of behaviour problems on caregiving stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2006;50:172–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liptak GS, Benzoni LB, Mruzek DW, Nolan KW, Thingvoll MA, Wade CM, et al. Disparities in diagnosis and access to health services for children with autism: Data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2008;29:152–160. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318165c7a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Bailey A. Autism spectrum disorders. In: Rutter M, Taylor E, editors. Child and adolescent psychiatry. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific; 2002. pp. 664–681. [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Pickles A, McLennan J, Rutter M, Bregman J, Folstein S, et al. Diagnosing autism: Analyses of data from the Autism Diagnostic Interview. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1997;27:501–517. doi: 10.1023/a:1025873925661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Le Couteur A. Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1994;24:659–685. doi: 10.1007/BF02172145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lounds J, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Shattuck PT. Transition and change in adolescents and young adults with autism: Longitudinal effects on maternal well-being. American Journal on Mental Retardation. 2007;112:401–417. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[401:TACIAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckasson R, Borthwick-Duffy S, Buntinx WHE, Coulter DL, Craig EM, Reeve A, et al. Mental retardation: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. 10. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M, Ryff CD, Bumpass LL, Shipley M, Marks NF. Social inequalities in health: Next questions and converging evidence. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;44:901–910. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00194-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawhood L, Howlin P, Rutter M. Autism and developmental receptive language disorder—a comparative follow-up in early adult life. I: Cognitive and language outcomes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2000;41:547–559. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern CW, Sigman M. Continuity and change from early childhood to adolescence in autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46(4):401–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piven J, Harper J, Palmer P, Arndt S. Course of behavioral change in autism: A retrospective study of high-IQ adolescents and adults. Journal of the Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1996;35:523–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199604000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue JR, Morgan SB, Geffken GR. Families of autistic children: Psychological functioning of mothers. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1990;19:371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff CD, Singer BH. Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2008;9:13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer MM, Krauss MW, Shattuck PT, Orsmond G, Swe A, Lord C. The symptoms of autism spectrum disorders in adolescence and adulthood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2003;33:565–581. doi: 10.1023/b:jadd.0000005995.02453.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shattuck PT, Seltzer MM, Greenberg JS, Orsmond GI, Kring S, Bolt D, et al. Changes in autism symptoms and maladaptive behaviors among adolescents and adults with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1735–1747. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0307-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea S, Turgay A, Carroll A, Schulz M, Orlik H, Smith I, et al. Risperidone in the treatment of disruptive behavioral symptoms in children with autistic and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatrics. 2004;114:634–641. doi: 10.1542/peds.2003-0264-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea V, Mesibov GB. Adolescents and adults with autism. In: Volkmar FR, Paul R, Klin A, Cohen DJ, editors. Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders, Vol. 1: Diagnosis, development, neurobiology, and behavior. 3. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2005. pp. 288–311. [Google Scholar]

- Shepperdson B. Two longitudinal studies of the abilities of people with Down’s syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1995;39:419–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2788.1995.tb00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Carter AS, Cicchetti DV. Vineland Screener: Overview, reliability, validity, administration, and scoring. New Haven: Yale University Child Study Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL. The transition out of high school and into adulthood for individuals with autism and for their families. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 2009;38:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor JL, Seltzer MM. Brief report: Employment and post-secondary educational activities for young adults with autism spectrum disorders during the transition to adulthood. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-1070-3. under review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobing LE, Glenwick DS. Relation of the Childhood Autism Rating Scale-Parent version to diagnosis, stress, and age. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2002;23:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0891-4222(02)00099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP. Access to care for autism-related services. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007;37:1902–1912. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0323-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomanik S, Harris GE, Hawkins J. The relationship between behaviours exhibited by children with autism and maternal stress. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability. 2004;29:16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Tonge BJ, Einfeld S. Psychopathology and intellectual disability: The Australian child to adult longitudinal study. International Review of Research in Mental Retardation. 2003;26:61–91. [Google Scholar]

- Wheaton B, Gotlib IH. Trajectories and turning points over the life course: Concepts and themes. In: Gotlib IH, Wheaton B, editors. Stress and adversity over the life course: Trajectories and turning points. UK: Cambridge Press; 1997. pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf LC, Noh S, Fisman SN, Speechley M. Psychological effects of parenting stress on parents of autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1989;19:157–166. doi: 10.1007/BF02212727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]