Abstract

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a human genetic disease characterized by a DNA repair defect and progressive bone marrow failure. Central events in the FA pathway are the monoubiquitination of the Fancd2 protein and the removal of ubiquitin by the deubiquitinating enzyme, Usp1. Here, we have investigated the role of Fancd2 and Usp1 in the maintenance and function of murine hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Bone marrow from Fancd2−/− mice and Usp1−/− mice exhibited marked hematopoietic defects. A decreased frequency of the HSC populations including Lin-Sca-1+Kit+ cells and cells enriched for dormant HSCs expressing signaling lymphocyte activation molecule (SLAM) markers, was observed in the bone marrow of Fancd2-deficient mice. In addition, bone marrow from Fancd2−/− mice contained significantly reduced frequencies of late-developing cobblestone area-forming cell activity in vitro compared to the bone marrow from wild-type mice. Furthermore, Fancd2-deficient and Usp1-deficient bone marrow had defective long-term in vivo repopulating ability. Collectively, our data reveal novel functions of Fancd2 and Usp1 in maintaining the bone marrow HSC compartment and suggest that FA pathway disruption may account for bone marrow failure in FA patients.

Keywords: Hematopoiesis and Stem Cells, Fancd2 mice, Usp1 mice

INTRODUCTION

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a chromosome instability syndrome characterized by childhood-onset aplastic anemia, multiple congenital anomalies, heightened cancer susceptibility, and cellular hypersensitivity to interstrand DNA crosslinking agents [1, 2]. Increased chromosomal breakage following exposure to DNA crosslinking agents, such as mitomycin C (MMC), is the cellular hallmark of FA [3, 4]. FA patients have an increased risk of developing malignancies, particularly acute myelogenous leukemia and squamous cell carcinomas [5, 6]. Progressive bone marrow failure and late-developing myeloid malignancies account for 90% mortality and morbidity in FA patients [7]. Bone marrow failure in FA children is attributed partly to the excessive apoptosis and subsequent failure of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) compartment.

There are 13 known FA genes (A, B, C, D1, D2, E, F, G, I, J, L, M, N). The FA pathway, regulated by these 13 FA gene products [8], mediates DNA repair and promotes normal cellular resistance to DNA crosslinking agents [4]. A critical step in this pathway is the monoubiquitination of the FANCD2 protein and its binding partner FANCI [9–11]. Upon DNA damage or during S-phase, monoubiquitinated FANCD2 is targeted to chromatin [12] where it interacts, either directly or indirectly, with additional downstream FA proteins (FANCD1, FANCN, and FANCJ) and assembles in nuclear foci.

Recent studies indicate that FANCD2 is deubiquitinated by the ubiquitin-specific protease, USP1 [13, 14]. USP1 is not a FA gene per se, since no humans with FA have been identified with mutations in the USP1 gene. Disruption of the Usp1 gene in chicken cells (DT40) results in crosslinker hypersensitivity [15]. Usp1 deficiency in murine primary cells also leads to crosslinker hypersensitivity [16] and defective Fancd2-mediated DNA repair. Thus, Fancd2 and Usp1 are two critical regulators of the FA pathway. The Fancd2 gene encodes a protein with no clear homology to other protein functional motifs.

Murine models are available with disruption of Fancc [17], Fanca [18], Fancg [19], Fancl [20], Fancd2 [21], and Fancd1 [22]. FA-deficient mice are generally small, exhibit decreased fertility with abnormal germ cell development, and have heightened crosslinker sensitivity of their primary cells [23]. Interestingly, Usp1−/− mice have a strong resemblance to FA mice (small size, infertility, cellular MMC hypersensitivity, chromosome instability) [16]. Although FA mice do not develop spontaneous bone marrow failure, the Fancc−/− mice and mice with hypomorphic mutation in Fancd1 exhibit stem cell dysfunction upon transplantation [22, 24, 25]. FA mouse models also develop bone marrow failure after sublethal doses of MMC [26]. Here, we specifically address whether Fancd2 and Usp1, two critical regulators of FA pathway, are also vital for maintenance of the hematopoietic compartment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Mice deficient for Fancd2 were generated using embryonic stem (ES) cell lines in which Fancd2 was inactivated using retroviral insertional mutagenesis and gene trap technology as described [27] in the literature. The Omnibank library database of disrupted genes (http://www.lexgen.com) generated by Lexicon Genetics (The Woodlands, Texas.) was screened using the mouse Fancd2 cDNA sequence. Two independent murine ES cell clones (OST2 and OST5) with mutational insertion in intron one (between exon one and two) were identified, wherein the Fancd2 gene had been disrupted. Both the ES cell lines were used to generate Fancd2−/− mice. The ES cells were injected into C57BL/6 host blastocysts and implanted into pseudopregnant females. Chimeric mice were generated and bred to C57BL/6 mice. The resulting mice heterozygous for the gene trap (Fancd2+/−) were crossed to produce homozygous Fancd2−/− mice containing the gene trap in both alleles. Genotyping of the offsprings was confirmed by southern blotting (data not shown) as well as by PCR (Supporting Information Figure S1B). Following PCR primers were used to genotype the OST2 and OST5 mouse lines:

- OST2 Mice

- OST2 F: 5′–CAT GCA TAT AGG AAC CCG AAG G–3′

- OST2 R: 5′–CAG GAC CTT TGG AGA AGC AG–3′

- LTR F: 5′–GGC GTT ACT TAA GCT AGC TTG–3′

- OST5 Mice:

- OST5 F: 5′–AAG GTC AGC CAG TCC TCA GA–3′

- OST5 R: 5′–GCC AGA ATC TGT GGG TTT TG–3′

- LTR F: 5′–GGC GTT ACT TAA GCT AGC TTG–3′

Usp1−/− mice in C57BL/6 background were generated as described in Kim et al. [16]. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. In most of the experiments, mice were used between 3 and 7 months of age.

Chromosome Breakage Assay for Murine Splenocytes

Splenocytes were prepared from 3 to 4-month-old mice as previously described [19]. Briefly, spleen tissues were harvested from wild-type and Fancd2−/− mice and cell suspensions were made by mincing the tissue in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 10 mM HEPES buffer (Gibco, Grand Island, NY, http://www.invitrogen.com) (HBSS++). Splenocytes were passed through 21-gauge needles to obtain single cell suspensions and filtered through 70-lm nylon filter. Red blood cells were removed by lysis in ACK buffer (Biowhitaker, Lonza, Walkersville, MD, http://www.lonza.com) and lymphocytes were resuspended in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovine serum plus phytohemagglutinin. Cells were cultured for 24 hours and exposed to MMC for an additional 48–72 hours., and used for chromosomal analysis.

Immunoblotting of Murine Fancd2 and Fanci Proteins

Primary splenocytes or bone marrow cells were lysed in 2× SDS lysis buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA. http://www.bio-rad.com) after removal of RBCs using ACK lysis buffer (Biowhitaker). The proteins were electrophoresed on a 7.5% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose, and immunoblotted with a polyclonal antibodies against murine Fancd2 or Fanci. A rabbit polyclonal antibody (G33) against murine Fancd2 was generated in our laboratory using a GST-Fancd2 (N-terminal) and affinity purified using a GST-Fancd2 (N-terminal) column [28]. Anti-human-Fanci antibody (A301-250A) was obtained from Bethyl Laboratories, Inc. Anti-Usp1 and anti-PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) antibodies are previously described [16].

Immunohistochemistry for Fancd2

Mouse bones were fixed in 10% buffered formalin overnight and preserved in 70% alcohol. Following dehydration, the tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For immunostaining to detect FANCD2 expression using AQUA imaging system, the paraffin-embedded sections were subjected to heat-mediated antigen retrieval using standard protocols and the slides were pretreated with Peroxidase Block (DAKO USA, Carpinteria, CA, http://www.dakousa.com) for 5 minutes to quench endogenous peroxidase activity. Slides were washed in 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, and incubated in Protein Block, Serum Free (DAKO) for 20 minutes to reduce nonspecific background. Rabbit polyclonal anti-murine Fancd2 antibody was diluted (1:50) in DaVinci Green Diluent (Biocare Medical, http://www.biocare.net) and applied overnight. Slides were then treated with Envision antirabbit (ready to use; DAKO) for 1 hour to fully saturate the first primary antibody. After washing, Cy5-tyramide Signal Amplification System (1:50 dilution, Perkin-Elmer Life Science Products, Boston, MA, http://www.perkinelmer.com) was applied for 10 minutes to couple Cy5 dyes to the horseradish peroxidase. Polyclonal rabbit anti-myeloperoxidase antibody (1:500 dilution, DAKO) was incubated for 1 hour and detected using Alexa 555-conjugated goat antirabbit secondary antibody (1:200 dilution, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, http://www.invitrogen.com) for 30 minutes. Coverslips were sealed to slides by using Prolong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI (Molecular Probes) to visualize nuclei. Slides were scanned on PM2000 Imaging System (HistoRx, Inc., New Haven, CT, http://www.historx.com) with Spot Grabber software (HistoRx), and images were exported through AQUA analysis software (HistoRx).

Flow Cytometry

Bone marrow was harvested by flushing tibias and femurs from the hind limbs in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 2% fetal bovine serum and 10 mM HEPES buffer (Gibco) (HBSS++). Cells were then passed through 21-gauge needles to obtain single cell suspensions. The cellularity of bone marrow was determined by counting total live cells (excluding trypan blue) and total nucleated cells (using crystal violet in 3% acetic acid) on a hemocytometer. Initially, for LSK (Lineage-Sca-1+c-Kitþ) staining, cells were stained in HBSS++ using Biotinylated-anti-lineage antibody cocktail (anti-Mac1α, Gr-1, Ter119, CD3e, and B220 all from BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA, http://www.bdbiosciences.com), PE-anti-Sca-1 antibody (clone E13-161.7, BD Biosciences), and APC-anti-c-Kit antibody (clone 2B8, BD Biosciences), followed by staining with a secondary Cychrome-Streptavidin (BD Biosciences) antibody. For apoptosis detection, cells were further stained with FITC-AnnexinV (BD Biosciences). For multiparameter flow cytometric analysis of progenitors [29, 30] and HSC subpopulations [31, 32], bone marrow cells were stained using alternative flurochromes for lineage, anti-Sca-1 and anti-c-kit antibodies. Briefly, the lineage stain was represented with PE-Cy5-conjugated antibodies raised against CD3 (145-2c11-BD Biosciences), CD4 (RM4-5-BD Biosciences), CD8a (53-6.7-eBioscience), CD19 (6D5-eBioscience, San Diego, CA, http://www.ebioscience.com), B220 (RA3-6B2-eBioscience), Gr1 (RB6-8C5-eBioscience), and Ter119 (Ter119-Biolegend, San Diego, CA, http://www.biole-gend.com). The LSK population was determined by staining with c-Kit-AlexaFluor 750 (2B8-eBioscience) and Sca-1-APC (D7-eBioscience) in combination with the lineage cocktail described above. To assess long-term HSCs and dormant HSC-enriched populations, cells were stained with LSK antibodies in addition to CD150-PE (TC15-12F12.2-Biolegend), CD48-PacBlue (HM48-1-Biolegend), and CD34-FITC (RAM34-BD Biosciences). Long-term HSCs (LT-HSCs), short-term HSCs (ST-HSCs), and multipotent progenitors (MPPs) were quantified by combining Flk2 (CD135)-PE (A2F10.1-BD Biosciences) and CD34-FITC with the LSK stain. The various Myeloid progenitors populations were evaluated by staining total bone marrow cells with FcγRII/III (CD16/32)-PE-Cy7 (93-eBioscience) and CD34-FITC in addition to LSK stain. Common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) were evaluated by analyzing IL7R (CD127)-PE (SB/199-Biolegend) expression in addition to the LSK stain. The samples were acquired using a BD FACSAria high-speed sorter or Dako MoFlo high-speed sorters and data was subsequently analyzed using FlowJo software.

Colony Assays

Bone marrow cells were isolated from femurs and tibiae of mice, and cells were seeded in 12-well plates at a density of 70,000 cells/well in methylcellulose medium containing rm stem cell factor, rm IL-3, rm IL-6, and rh Erythropoietin (Methocult GF M3434, Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada, http://www.stemcell.com). For MMC treatments, MMC was added in cultures in a dilution series of 0–100 nM. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 7–10 days and macroscopic hematopoietic colonies (CFU-C, colony-forming units in culture) were counted. The triplicate cultures were set up and average was calculated.

Cobblestone area-forming cell (CAFC) assay

In vitro determination of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell frequencies was performed by a limiting dilution analysis of CAFC in microcultures using the bone marrow stromal cell line FBMD-1 according to methods previously described [33, 34]. This assay measures a spectrum of hematopoietic cells that is well validated to compare with other functional assays. Specifically, day 7 and day 14 CAFC correspond to early progenitor cells and to CFU (colony-forming units)-spleen-day 12 cells while the more primitive HSC with long-term repopulating ability correspond to day 28 and 35 CAFC [33].

Bone Marrow Transplantation Assay

The long-term repopulating ability of bone marrow from Fancd2−/− mice, Usp1−/− mice and littermate wild-type control mice was assessed using competitive repopulation assays [35]. Varying cell doses of donor CD45.2 bone marrow harvested from Fancd2−/−, Usp1−/−, or wild-type mice were mixed with 2 × 105 of competing bone marrow cells harvested from recipient-type B6.SJL-Ptprca Pep3b/BoyJ congenic CD45.1 mice (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME, http://www.jax.org) and injected IV into lethally irradiated (1000 cGy) B6.BoyJ congenic CD45.1 recipients. Five mice were transplanted for each donor cell dose group. Blood samples were collected from the recipients at 4 weeks and 16 weeks and the donor cells were determined. Donor-type blood chimerism was determined by staining peripheral blood samples with FITC-anti-CD45.2 (clone 104) antibody. For multilineage reconstitution, the percentage of donor-derived T-cells, B cells and myeloid cells was determined by costaining with PE-labeled anti-CD3e (clone 145-2C11), anti-B220 (clone RA3-6B2), and anti-Mac-1/Gr-1 antibodies (clones M1/70 and RB6-8C5), respectively and analyzed on a FACScan instrument (Beckton Dickinson). All the antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed for statistical difference between the wild-type and mutant groups using a two tailed Student’s t-test. Differences were considered significant at p < .05.

RESULTS

Tissue-Specific Expression of Murine FANCD2 Protein

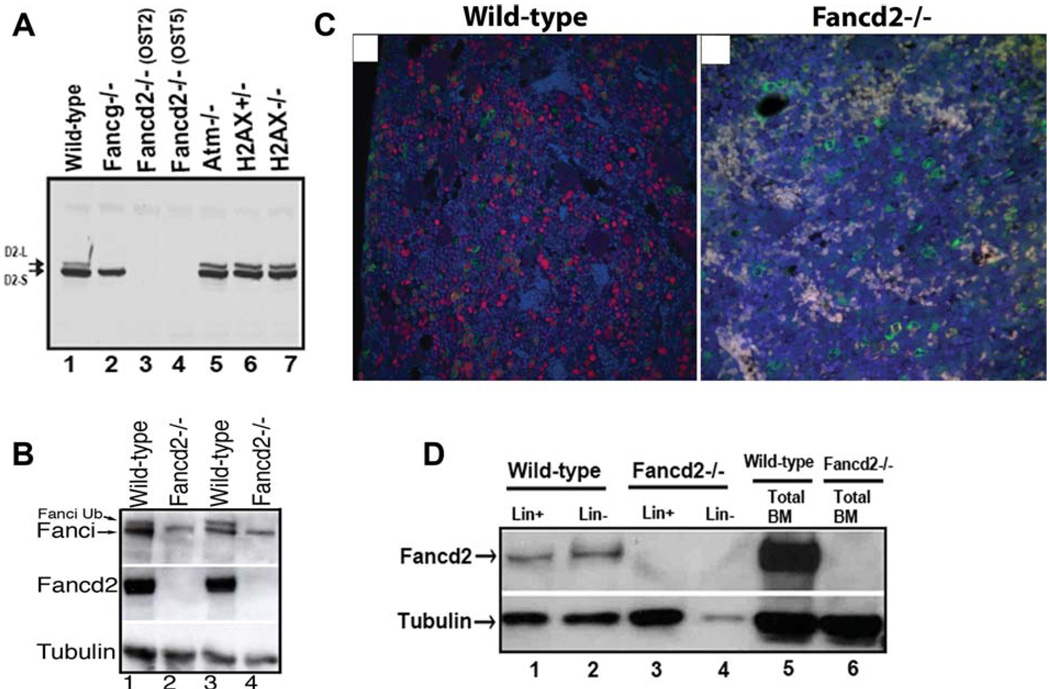

We generated Fancd2-deficient mice using the murine ES cell clones in which Fancd2 was inactivated due to retroviral insertion. The ES cell clones with inactivation of Fancd2 were readily available from a commercial source (Lexicon Genetics, The Woodlands, Texas) and therefore were used to generate the Fancd2-deficient mice. A schematic of the disrupted Fancd2 gene is shown in Supporting Information Figure S1A,B. Two independent mouse lines harboring retroviral insertion were derived. To confirm that protein expression was abrogated in these mouse lines, western blots were performed on splenocytes (Fig. 1A) and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; data not shown), using an antibody that recognizes the mouse Fancd2 protein [28]. The native Fancd2 protein, together with its higher molecular weight, ubiquitinated form were present in wild-type mice (Fig. 1A, lane 1). Ubiquitinated Fancd2 protein was not present in splenocytes from the Fancg−/− mice previously generated in our laboratory [19] (Fig. 1A, lane 2). No Fancd2 protein was detected in the splenocytes derived from either of the two independently derived Fancd2−/− mouse lines OST2 and OST5. As controls, ubiquitinated Fancd2 was expressed in splenocytes from mice deficient in Atm or H2AX (Fig. 1A, lanes 5, 6, 7). Fancd2 protein expression was abrogated in total bone marrow mononuclear cells from Fancd2−/−, mice (Fig. 1B, lanes 2,4). As predicted, the absence of Fancd2 protein resulted in decreased levels of Fanci protein and absent Fanci monoubiquitination (Fig. 1B, lanes 2,4).

Figure 1.

Fancd2 expression in murine tissues. (A): Western blot of Fancd2 in splenocytes with indicated genotypes. Note that Fancd2 protein expression is deficient in both OST2 and OST5 mouse lines (lanes 3, 4). (B): Western blot of Fanci and Fancd2 in bone marrow cells from four different mice with indicated genotypes. (C): Detection of Fancd2 in the bone marrow in the bone sections using the HistoRX fluorescence imaging system. Representative examples of fluorescent staining for Fancd2 (red) and myeloperoxidase (green) on wild-type and Fancd2−/− paraffin embedded bone sections are shown. DAPI stain (blue) highlights the total nuclei. Note that Fancd2 staining (red) is observed in subset of the myeloperoxidase stained myeloid cells (green) as well as in the myeloperoxidase negative cells in the wild-type bone marrow. Magnification ×400. (D): Western blot of Fancd2 in fractionated Lin+ and Lin− BM cells from wild-type and Fancd2−/− mice. Abbreviations: BM, bone marrow; Lin−, lineage negative; Lin+, lineage positive.

Immunohistochemical analysis for tissue-specific expression pattern of the Fancd2 protein revealed high expression of Fancd2 in spleen, bone marrow, testis, and lymph nodes (data not shown). When Fancd2 expression in the bone marrow was analyzed using a multiparameter fluorescence-based imaging system (Fig. 1C), Fancd2 was observed abundantly in both myeloid and nonmyeloid hematopoietic precursors. Fancd2 expression was also detected in the rare population of lineage negative bone marrow cells which are enriched for HSCs (Fig. 1D, lanes 1, 2). Collectively, these data indicated that Fancd2 is expressed in hematopoietic tissues including a population of bone marrow which contains HSCs, in keeping with previous studies indicating that FA genes are expressed in bone marrow in Lin- cells, CD34− cells and in CD34+ stem cells [36].

Loss of Fancd2 Leads to FA Phenotypes in Mice

The genotypes of offspring from crossing Fancd2+/− mice followed predicted Mendelian frequencies, indicating that no embryonic lethality or perinatal lethality was associated with biallelic Fancd2 mutations (data not shown). No gross phenotypic differences were noted between the wild-type, Fancd2+/−, or Fancd2−/− offspring. Severe abnormalities were observed in the gonads of Fancd2−/− mice along with reduced fertility (data not shown). Both ovaries and testes from Fancd2−/− mice demonstrated significant testicular and ovarian atrophy compared to wild-type littermate controls (Supporting Information Figure S2A,B and data not shown), consistent with abnormalities observed in other FA mouse models [21, 23]. In addition to this generalized atrophy, ovaries and testes from Fancd2-deficient mice demonstrated germ cell defects with limited spermatogenesis and oogenesis (Supporting Information Figure S2B).

Cytogenetic analysis of metaphase spreads of splenocytes following in vitro MMC treatment showed that splenocytes from Fancd2−/− mice exhibited significantly increased chromosomal breaks and the radial forms characteristic of FA (Supporting Information Figure S2C,D). In addition, when bone marrow cells were grown in methylcellulose cultures for CFU-C assay in the presence of increasing concentrations of MMC, the Fancd2−/− progenitors cells exhibited severely decreased survival compared to the normal wild-type bone marrow progenitors (Supporting Information Figure S2E). The bone marrow progenitor cells from both the OST2 and OST5 Fancd2−/− mouse lines showed similar MMC sensitivity (data not shown).

Reduced HSC Content and Decreased Hematopoietic Activity in Fancd2-Deficient Bone Marrow

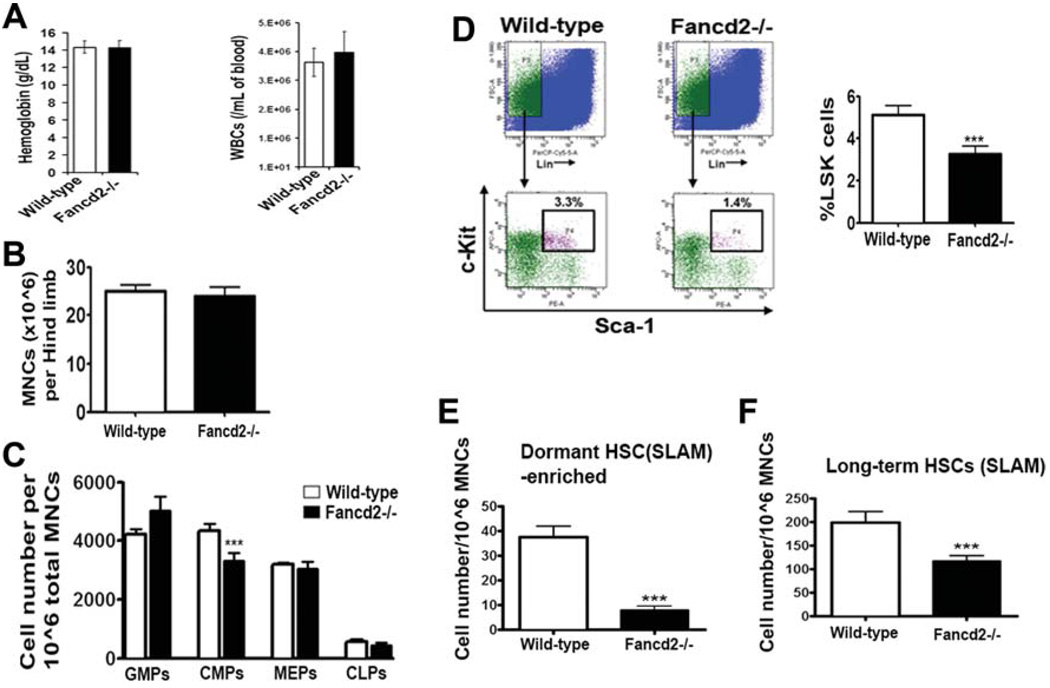

To test the role of Fancd2 in maintaining HSC function, we examined hematopoiesis in Fancd2-deficient mice (Fig. 2). Analysis of the peripheral blood in Fancd2−/− mice showed normal values for WBC counts, hemoglobin (Fig. 2A), platelets, erythrocyte mean cell volume, and hematocrit (data not shown). A comparison of the number of bone marrow mononuclear cells indicated no significant differences among wildtype and Fancd2−/− mice (Fig. 2B). To assess the abundance of hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells in Fancd2−/− mice, bone marrow was subjected to multiparameter fluorescence-activated cell scanning (FACS) analysis. Frequencies of mature myeloid cells or lymphoid cells were normal in the marrow of Fancd2−/− mice (data not shown). Except for the modest reduction in CMPs (common myeloid progenitors) (p value = .045), no statistical differences were observed in terms of CLP (common lymphoid progenitors), GMP (granulocyte/macrophage progenitor), and MEP (megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor) content between wild-type and Fancd2−/− bone marrow (Fig. 2C). In contrast, significant reduction in the frequencies of HSC-enriched LSK compartment, defined as Lin-Sca-1+c-Kit+ cells (Fig. 2D; p value = .005), was observed in the bone marrow of Fancd2−/− mice.

Figure 2.

Bone marrow from Fancd2−/− mice exhibit abnormalities in the size of progenitor and stem cell compartments. (A): Peripheral blood WBC counts and hemoglobin levels in wild-type and Fancd2−/− mice (n = 5 per group). (B): Bone marrow cellularity in wild-type and Fancd2−/− mice (n = 8 for wild-type and n = 13 for Fancd2−/−). (C): Number of myeloid progenitors (GMPs, CMPs, MEPs) and lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) in the bone marrow of wild-type and Fancd2−/− mice (n = 3 per group). (D): Reduced frequencies of HSCs in the Fancd2−/− bone marrow. The left panel shows an example of a flow cytometric plot of Sca-1 and c-Kit staining of lineage negative bone marrow. The right panel shows frequencies of Lin-Sca1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells in the bone marrow ((n = 11 for wild-type and n = 16 for Fancd2−/−). (E): Number of cells enriched for dormant HSCs expressing SLAM code (Lin lowSca1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48−CD34− cells) in wild-type and Fancd2−/− bone marrow (n = 3 per group). (F): Number of long-term HSCs expressing SLAM code (Lin lowSca1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48−cells) in wild-type and Fancd2−/− bone marrow (n = 3 per group). Error bars represent SEM in all the panels. Asterisks represent data with statistically significant difference compared to the wild-type with p values < .05. Abbreviations: CLP, common lymphoid progenitors; CMP, common myeloid progenitors; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor; MNC, mononuclear cells; SLAM, signaling lymphocyte activation molecule; WBC, white blood cells.

The LSK population is known to be enriched for ST-HSCs, LT-HSCs, and MPPs. Long-term HSC and the most primitive dormant HSC population can be identified by the expression of SLAM (signaling lymphocyte activation molecule) code (CD150+CD48−) and CD34 receptors [32]. Accordingly, we analyzed bone marrow from wild-type mice and Fancd2−/− mice for long-term HSCs and a population enriched for dormant HSC within the LSK population (Fig. 2E, 2F). Interestingly, a significant reduction in the LT-HSC-SLAM (Lin-Sca1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48− cells) content and a severe deficit in the population enriched for dormant HSC (Lin-Sca1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48−CD34− cells) content were observed in the bone marrow of Fancd2−/− mice. Bone marrow from Fancd2−/− mice contained a fivefold reduced numbers of cells enriched for dormant HSCs compared to the bone marrow from wild-type mice (Fig. 2E) (p value = .0035). Furthermore, LT-HSC (Lin-Sca1+c-Kit+Flk2-CD34− cells) and ST-HSC (Lin-Sca1+c-Kit+Flk2-CD34+ cells) cell populations defined on the basis of expression of Flk2 and CD34 receptors were also significantly decreased in the Fancd2−/− bone marrow (Supporting Information, Figure S3). These data revealed that bone marrow from Fancd2−/− mice contains normal numbers of progenitors but are deficient in HSCs and its subpopulations including dormant HSC populations.

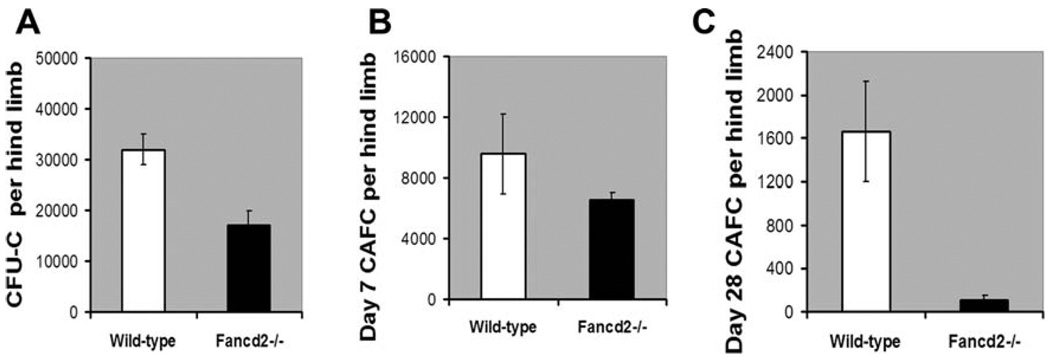

To examine the possible functional differences in the hematopoietic activity between the wild-type bone marrow and Fancd2−/− bone marrow, clonogenic in vitro assays were performed. The functional committed progenitor activity (CFU-C and day 7 CAFC frequencies) was moderately affected in the bone marrow of Fancd2−/− mice (Fig. 3A, 3B). Consistent with the reduced number of HSC, the primitive stem cell activity (late-developing day 28 CAFC activity) was significantly reduced (7–10-fold reduction, p value = .022) in the bone marrow of Fancd2−/− mice compared to the bone marrow from wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). Collectively, these data demonstrate a stem cell deficit in Fancd2−/− mice, in spite of their continuing ability to maintain progenitor populations and blood cells.

Figure 3.

Fancd2-deficient bone marrow contains reduced functional hematopoietic activity. (A, B) Decreased progenitor activity (CFU-C and day 7 CAFC) in the Fancd2−/− bone marrow compared to the wild-type bone marrow. (C): Significant reduction in the primitive HSC activity (day 28 CAFC) in the bone marrow of Fancd2−/− mice compared to the bone marrow of wild-type mice. Data in all the plots are average from n = 4 Wild-type mice and n = 4 Fancd2−/− mice. Error bars indicate SEM. The p values for the difference between wild-type and Fancd2−/− groups in the plots A, B, and C were 0.005, 0.172, and 0.022, respectively. Abbreviations: CAFC, cobblestone area-forming cell; CFU-C, colony-forming units in culture.

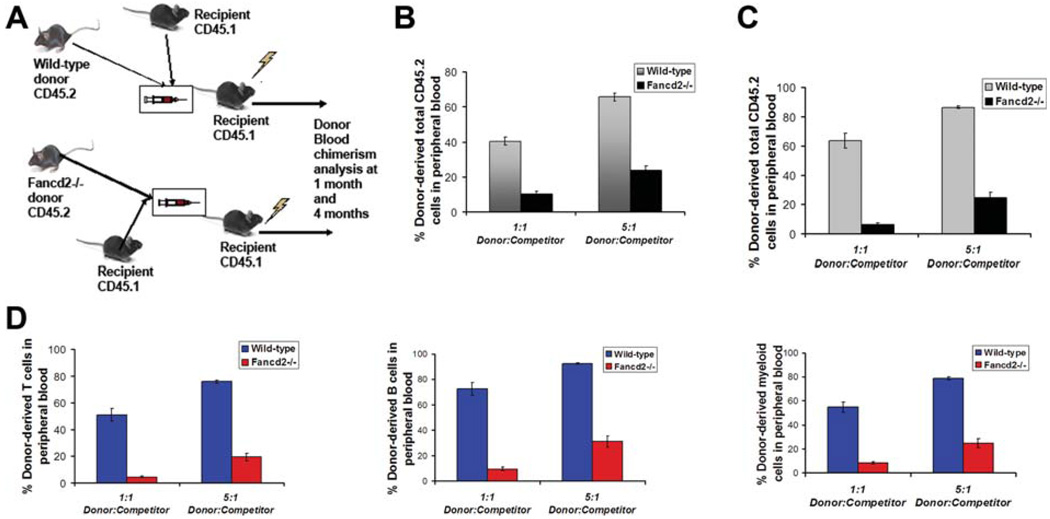

Fancd2-Deficient Bone Marrow Is Defective in Short-Term and Long-Term Repopulating Ability In Vivo

To confirm the HSC defect in the Fancd2−/− bone marrow, we performed competitive bone marrow transplants with whole bone marrow obtained from wild-type and Fancd2−/− mice. A constant number of wild-type competitor cells from CD45.1 mice were mixed with varying amounts of donor whole bone marrow cells from CD45.2 wild-type or Fancd2−/− mice and transplanted into lethally irradiated recipients (Fig. 4A). Engraftment analysis by peripheral blood chimerism at 4 week post-transplants showed three- to fourfold reduced chimerism in recipients transplanted with Fancd2−/− bone marrow (Fig. 4B). In addition, long-term engraftment assessed at 16 weeks post-transplant displayed a profound deficit. In comparison to the chimerism in recipients transplanted with wild-type marrow, severe reduction (average 8- and 10-fold reduction, at 1:1 donor:competitor ratios) in blood chimerism in total leukocytes was observed in recipients transplanted with Fancd2−/− bone marrow (Fig. 4C). Even when transplanted at 5:1, donor: competitor ratios, Fancd2−/− bone marrow revealed a three- and fourfold reduction in engraftment efficiency (Fig. 4C). Similar engraftment defects were revealed in the reconstitution of T-cells, B cells and myeloid cells in the recipients transplanted with Fancd2−/− bone marrow (Fig. 4D). Thus, animals receiving Fancd2−/− bone marrow showed significantly reduced short-term and long-term multilineage reconstitution as compared to the recipients of wild-type bone marrow. Taken together, this data indicated that Fancd2−/− bone marrow cells are impaired in their in vivo repopulating ability and confirmed that Fancd2 deficiency leads to HSC defects.

Figure 4.

Bone marrow cells from Fancd2−/− mice show reduced long-term repopulating potential in vivo. (A): Schematic of the competitive bone marrow transplantation strategy. (B): Donor cell engraftment (total leukocytes) at 4 weeks in peripheral blood of recipients transplanted with wild-type or Fancd2−/− donor bone marrow. (C): Donor cell engraftment (total leukocytes) at 16 weeks in peripheral blood of recipients transplanted with wild-type or Fancd2−/− bone marrow. (D): Donor-derived T-cell engraftment (left panel), B cell engraftment (middle panel), and myeloid cell engraftment (right panel) at 16 weeks in peripheral blood of recipients transplanted with wild-type or Fancd2−/− bone marrow. Data in all the plots are average from 15 recipients (n = 3 donor wild-type or Fancd2−/− mice in each group, n = 5 recipient mice per donor sample). Error bars represent SEM. The p values for the statistical difference between the wild-type and Fancd2−/− mice are highly significant (p < .0005).

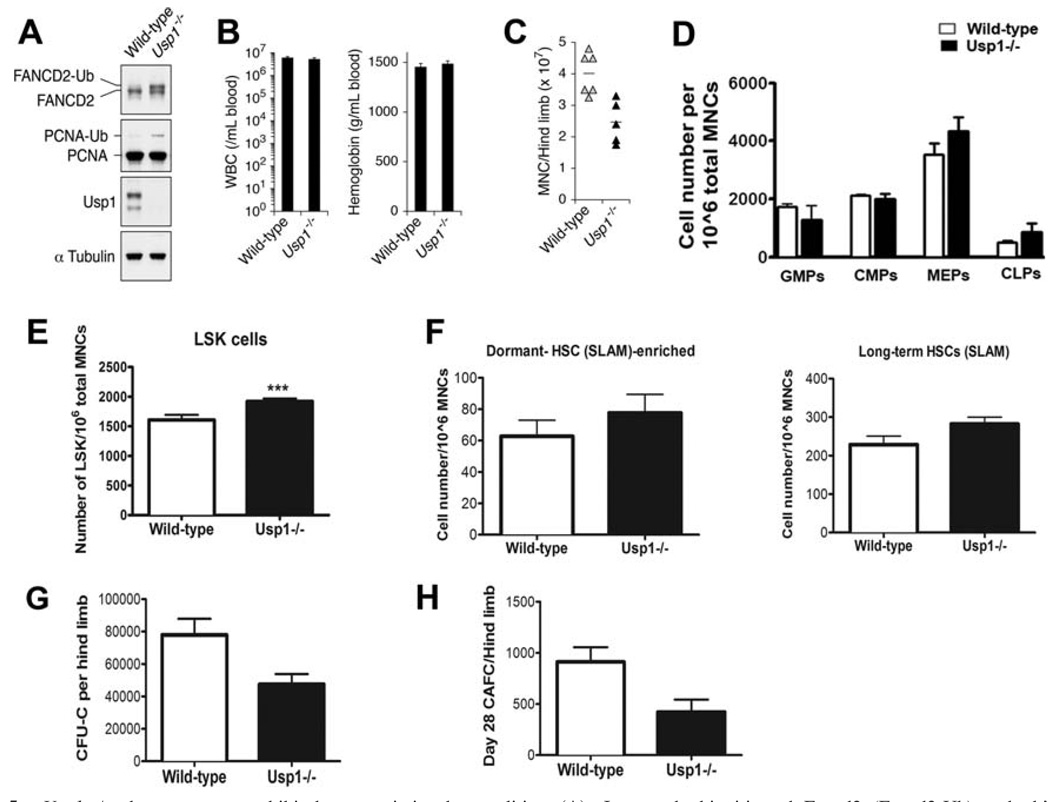

Bone Marrow from Usp1-Deficient Mice Exhibit Hematopoietic Abnormalities

Usp1−/− mice share many phenotypic features with other FA gene knockout mice [16]. Using Usp1−/− MEFs, we determined that Usp1 is a critical regulator of FA pathway required for Fancd2 foci formation during DNA repair [16]. In order to assess the function of Usp1 in bone marrow failure in FA, we analyzed hematopoiesis in Usp1−/− mice. Usp1 protein expression was absent in the bone marrow from Usp1−/− mice. As expected, the bone marrow from Usp1-deficient mice exhibited increased ubiquitination of both known Usp1 substrates Fancd2 and PCNA (Fig. 5A). Mice deficient in Usp1 did not develop anemia and showed normal values for white blood cell counts in the peripheral blood (Fig. 5B). However, the bone marrow cellularity was decreased in Usp1−/− mice (Fig. 5C) which may be due to their smaller size. Multiparameter flow cytometric analysis of the bone marrow from wild-type mice and Usp1−/− mice did not reveal statistically significant differences in the number of mature T/B/myeloid cells (data not shown), myeloid progenitors or lymphoid progenitors with an exception of a slight increase in the of MEP content in the Usp1−/− bone marrow (Fig. 5D). Interestingly, there appears to be a small but statistically significant increase in the size of the HSC compartment in the Usp1−/− bone marrow (Fig. 5E). Alternatively, the absence of Usp1 expression may alter the expression of HSC markers detected by FACS. Total LSK cells, including ST-HSCs and LT-HSCs, were higher in Usp1−/− bone marrow (Supporting Information Figure S4B,C). The abundance of long-term HSCs and dormant HSC-enriched populations defined on the basis of SLAM markers was not affected in the Usp1−/− bone marrow (Fig. 5F). When bone marrow from Usp1−/− mice was examined for functional hematopoietic activity, decreased CFU-C as well as day 28 CAFC frequencies were observed compared to the bone marrow from wild-type mice (Fig. 5G, 5H). Collectively, these data indicate that bone marrow hematopoiesis is perturbed in Usp1−/− mice, with an abnormal size of the HSC compartment and reduced HSC function.

Figure 5.

Usp1−/− bone marrow exhibit hematopoietic abnormalities. (A): Increased ubiquitinated Fancd2 (Fancd2-Ub) and ubiquitinted PCNA (PCNA-Ub) in the bone marrow of Usp1-deficient mice. Western blots of bone marrow lysates from wild-type and Usp1−/− mice immunoblotted with indicated antibodies are shown. (B): Normal blood counts and hemoglobin levels in Usp1−/− mice. (C): Decreased bone marrow cellularity in Usp1−/− mice. (D): Number of myeloid progenitors (GMPs, CMPs, MEPs) and lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) in the bone marrow from wild-type and Usp1−/− mice. (E): Number of HSCs (Lin-Sca1+c-Kit+ (LSK) cells) in the bone marrow from wild-type and Usp1−/− mice. (F): Number of long-term HSCs expressing SLAM code (Lin lowSca1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48− cells; right panel) and cells enriched for dormant HSCs expressing SLAM code (Lin lowSca1+c-Kit+CD150+CD48−CD34− cells; left panel) in wild-type and Usp1−/− bone marrow. (G): Reduced CFU-C activity of the bone marrow from Usp1−/− mice. (H): Decreased hematopoietic stem cell activity (day 28 CAFC) of the bone marrow from Usp1−/− mice. Data are average from at least three mice per group in all the panels. Error bars indicate SEM. Asterisks represent data with statistically significant difference compared to the wild-type with p values < .05. CFU-C, colony-forming units in culture; CAFC, cobblestone area-forming cell; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitors; GMP, granulocyte/macrophage progenitor; HSC, hematopoietic stem cell; LSK, Lineage-Sca-1+c-Kit+; MNC, mononuclear cells; MEP, megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; SLAM, signaling lymphocyte activation molecule; WBC, white blood cells.

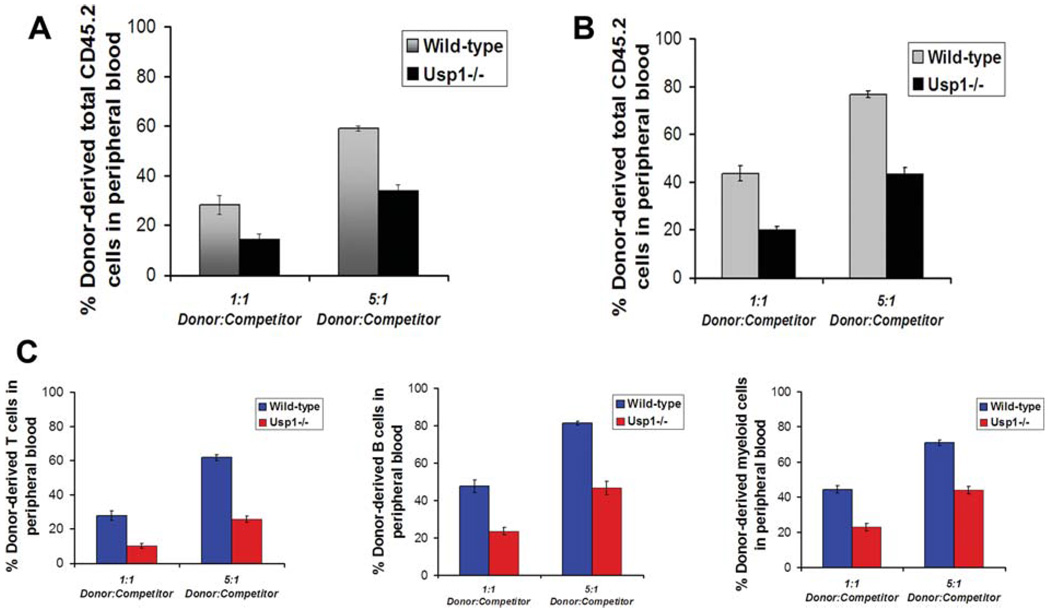

Usp1-Deficient Bone Marrow Display Reduced Short-Term and Long-Term Repopulating Ability In Vivo

To test whether Usp1 deficiency affects HSC function in vivo, we competitively transplanted bone marrow from CD45.2+ wild-type and littermate Usp1−/− mice into lethally irradiated recipients along with 2 × 105 wild-type CD45.1+ bone marrow cells. Four weeks and sixteen weeks following the transplantation, we analyzed the blood of the recipients for engraftment by CD45.2+ donor cells. Recipients transplanted with bone marrow from Usp1−/− mice showed twofold reduction in donor-derived chimerism compared to the recipients transplanted with bone marrow from wild-type mice (Fig. 6A) at 4 weeks post-transplantation. A two- to threefold reduction in the donor cell reconstitution of total leukocytes, including T-cells, B cells and myeloid cells, was observed in the recipients transplanted with Usp1−/− bone marrow (Fig. 6B, 6C) at 16 weeks post-transplantation. These results indicated that Usp1-deficient bone marrow is compromised in its short-term and long-term repopulating ability in vivo.

Figure 6.

Bone marrow cells from Usp1−/− mice show reduced long-term repopulating potential in vivo. (A): Donor cell engraftment (total leukocytes) at 4 weeks in peripheral blood of recipients transplanted with wild-type or Usp1−/− bone marrow. (B): Donor cell engraftment (total leukocytes) at 16 weeks in peripheral blood of recipients transplanted with wild-type or Usp1−/− bone marrow. (C): Donor-derived T-cell engraftment (left panel), B cell engraftment (middle panel), and myeloid cell engraftment (right panel) at 16 weeks in peripheral blood of recipients transplanted with wild-type or Usp1−/− bone marrow. Data in all the plots are average from 15 recipients (n = 3 donor wild-type or Usp1−/− mice in each group, n = 5 recipient mice per donor sample). Error bars indicate SEM. The p values for the statistical difference between the wild-type and Usp1−/− mice are highly significant (p < .0005).

DISCUSSION

The FA pathway plays a critical role in maintaining genomic stability and protecting cells from DNA damage by crosslinking agents. We have investigated the role of the pathway in hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells by using mouse models lacking Fancd2 or Usp1. Loss of Fancd2 or Usp1 in mice resulted in HSC defects in bone marrow. Significant deficiency in HSC content (including a population enriched for dormant HSCs) and severely impaired long-term repopulating activity were observed in the bone marrow from Fancd2−/− mice. Usp1-deficiency, in contrast, did not affect the HSC frequencies but did affect stem cell function, leading to the reduced long-term repopulating activity of the bone marrow. Together, our results indicate that Fancd2 and Usp1 are required for maintaining normal HSC function in the bone marrow.

Multiple FA mouse models have been previously described [23]. While FA patients develop spontaneous hematologic failure, most FA mouse models have relatively normal hematologic function, though anemia can be elicited by in vivo exposure to crosslinking agents [26]. In the current study, the cellular and gross phenotype of our Fancd2−/− mice are similar to those observed previously [21]. Cells from the Fancd2−/− mice exhibited the phenotypic hallmark of FA, namely, increased chromosomal breakage in response to MMC. A detailed assessment of the bone marrow function of Fancd2−/− mice has not been previously described, though the published Fancd2−/− model had significantly increased incidence of tumors.

Although spontaneous marrow failure has not been observed in FA mice, a defect in HSC function has been observed in Fancc−/− mice and Fancd1-deficient mice. Defects in the in vivo repopulating ability of bone marrow have been demonstrated in these mice using competitive repopulation and serial bone marrow transplant studies [22, 24, 25]. Our Fancd2-deficient and Usp1-deficient mice exhibited defects in their bone marrow hematopoietic functions, in spite of their ability to maintain the normal blood counts. Fancd2−/− bone marrow exhibited severely impaired in vivo multilineage repopulating activity in competitive bone marrow transplantation experiments. FACS analysis of the primitive subfractions of HSCs obtained from marrow of Fancd2−/− mice demonstrated that they contain almost 50% fewer LSK cells and almost 80% fewer cells enriched for dormant HSCs compared to the wild-type bone marrow.

In contrast to the decrease in HSC frequencies in the absence of Fancd2, loss of Usp1 resulted in a slight increase in the abundance (frequencies) of HSC compartment without affecting the myeloid/lymphoid progenitor compartments. The HSC functional activity (in vivo repopulation ability) of the bone marrow was reduced, however, in the absence of Usp1 gene function. Taken together, the loss of Fancd2 gene function in mice leads to severe deficiency of HSCs enriched for dormant population along with significant reduction in the marrow regenerative potential. Moreover, for the first time, we show that the loss of a deubiquitinating enzyme Usp1 in mice results in a bone marrow engraftment defect. Even though, the Usp1-deficient mice exhibit a more severe phenotype than most FA mouse models, with ~ 80% perinatal lethality, testicular atrophy, and depletion of male germ cells [16]; the bone marrow engraftment defect is less severe. Nonetheless, our data underscores the importance of Fancd2 and its regulation by monoubiquitination/deubiquitination in maintaining the bone marrow regenerative potential and suggests that this regulation may contribute to the pathogenesis of FA. Besides regulating the FA pathway in a co-operative fashion, Fancd2 and Usp1 may have additional independent functions that maintain the hematopoiesis as the double knockout mice deficient in both Fancd2 and Usp1 exhibit more severe HSC defects than either single knockout (data not shown).

It is unclear why FA mice have relatively normal blood cell levels, however, several mechanisms are possible. Shortened telomere length has been observed in cells from FA patients [37]. Mice harbor long telomere lengths which, together with their shorter life spans, might protect bone marrow cells from senescence. Alternatively, mice deficient in FA pathway, like humans, are hypersensitive to DNA interstrand crosslinks. The mild phenotype in mice could be due to fewer spontaneous DNA lesions, due to lower murine levels of endogenous crosslinking compounds, such as formaldehyde [38] or malondialdehyde [39].

The impaired regenerative potential of the Fancd2−/− bone marrow may be due to reduced HSC reserve, functionally defective HSCs, or a combination of the two. Defective repopulating potential of Usp1−/− marrow may be due to functionally defective self-renewing HSCs. Loss of HSC reserve in the absence of Fancd2 could result from increased DNA damage, increased apoptosis, increased cycling (loss of quiescence) or defective bone marrow microenvironment. Indeed, we observed increased apoptosis in HSCs from the bone marrow of Fancd2−/− mice in comparison to the HSCs from wild-type bone marrow (Supporting Information Figure S5). Moreover, HSCs from Fancd2−/− mice had increased number of cells in S/G2/M and significantly reduced number of quiescent cells in G0 phase of cell cycle (Supporting Information Figure S6). Defective homing capacity, associated with a decrease in Rho GTPase Cdc42, has been observed in human FA-A cells when transplanted into NOD/SCID (nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficiency) mice [40]. Enhanced cycling of HSCs have been reported in Fancc−/− bone marrow [41], perhaps contributing to apoptosis and defects in cytokine signaling. Loss of Fancg in mice results in a defect in mesenchymal stem/progenitor cell proliferation, suggesting that FA proteins may also be required for the bone marrow microenvironment [42]. Defective HSC function of the Fancd2-deficient bone marrow could result from hypersensitivity to xenotoxins other than cross-linking agents as FA cells are hypersensitive to interferon-gamma, TNF-alpha, and other agents causing oxidative damage [43–47].

A number of recent studies has suggested that DNA repair is essential for maintenance of hematopoietic function. Mice defective in different mechanisms of genome maintenance, for example NHEJ (Lig4-deficient mice Lig4Y288C, Ku80−/− mice), nucleotide base excision repair (XpdTTD mice), mismatch repair (MSH2−/− mice), interstrand cross-link repair (Ercc1−/− mice), and telomere maintenance (mTR−/− mice) have hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell defects [48–52]. HSCs from mice defective in homologous recombination-mediated DNA repair are most affected; bone marrow from Atm−/− mice and Rad50-deficient mice have hypocellular bone marrow [53, 54]. Our data on the loss of HSC function in Fancd2−/− mice and Usp1−/− mice further supports the importance of genomic stability in maintaining the long-term population of the bone marrow.

CONCLUSION

Fancd2 and Usp1, two important regulators of FA DNA repair pathway, are required to maintain the long-term regenerative potential of bone marrow. Fancd2 and Usp1 may also be required for protection of bone marrow HSC from DNA damage or for maintaining their quiescence status in the bone marrow microenvironment. Fancd2 and Usp1 mouse models may be useful in understanding the pathogenesis of FA and for the development of new therapeutic strategies to enhance the survival and expansion of FA HSCs.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are thankful to Mark Umphrey II, Dmitry Mirzon, and members of the DFCI flow cytometry facility for technical assistance. We thank Lisa Moreau for cytogenetic analyses. We thank Drs. Peter Mauch and Julian Down for valuable advice. This study was supported by NIH grants (RO1DK43889, RO1HL52725, U19A1067751) to A.D.D.

Footnotes

Author contributions: K.P.: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript; J.K., S.M.S., A.S., J.K.: conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; P.S., K.Z., A.H., M.K.D.: collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation; K.A., D.G.G.: conception and design, interpretation of data; A.D.: conception and design, data interpretation, financial support, manuscript writing, final approval of manuscript.

DISCLOSURE OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.D’Andrea AD, Grompe M. The Fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:23–34. doi: 10.1038/nrc970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joenje H, Patel KJ. The emerging genetic and molecular basis of Fanconi anaemia. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:446–457. doi: 10.1038/35076590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auerbach AD, Rogatko A, Schroeder-Kurth TM. International Fanconi Anemia Registry: Relation of clinical symptoms to diepoxybutane sensitivity. Blood. 1989;73:391–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang W. Emergence of a DNA-damage response network consisting of Fanconi anaemia and BRCA proteins. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:735–748. doi: 10.1038/nrg2159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosenberg PS, Greene MH, Alter BP. Cancer incidence in persons with Fanconi anemia. Blood 1. 2003;101:822–826. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy RD, D’Andrea AD. DNA repair pathways in clinical practice: Lessons from pediatric cancer susceptibility syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3799–3808. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.4171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kutler DI, Singh B, Satagopan J, et al. A 20-year perspective on the International Fanconi Anemia Registry (IFAR) Blood. 2003;101:1249–1256. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grompe M, van de Vrugt H. The Fanconi family adds a fraternal twin. Dev Cell. 2007;12:661–662. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garcia-Higuera I, Taniguchi T, Ganesan S, et al. Interaction of the Fanconi anemia proteins and BRCA1 in a common pathway. Mol Cell. 2001;7:249–262. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sims AE, Spiteri E, Sims RJ, III, et al. FANCI is a second monoubiquitinated member of the Fanconi anemia pathway. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:564–567. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smogorzewska A, Matsuoka S, Vinciguerra P, et al. Identification of the FANCI protein, a monoubiquitinated FANCD2 paralog required for DNA repair. Cell. 2007;129:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montes de Oca R, Andreassen PR, Margossian SP, et al. Regulated interaction of the Fanconi anemia protein, FANCD2, With Chromatin. Blood. 2005;105:1003–1009. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nijman SM, Huang TT, Dirac AM, et al. The deubiquitinating enzyme USP1 regulates the Fanconi anemia pathway. Mol Cell. 2005;17:331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nijman SM, Luna-Vargas MP, Velds A, et al. A genomic and functional inventory of deubiquitinating enzymes. Cell. 2005;123:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oestergaard VH, Langevin F, Kuiken HJ, et al. Deubiquitination of FANCD2 is required for DNA crosslink repair. Mol Cell. 2007;28:798–809. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim JM, Parmar K, Huang M, et al. Inactivation of murine Usp1 results in genomic instability and a Fanconi anemia phenotype. Dev Cell. 2009;16:314–320. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whitney MA, Royle G, Low MJ, et al. Germ cell defects and hematopoietic hypersensitivity to gamma-interferon in mice with a targeted disruption of the Fanconi anemia C gene. Blood. 1996;88:49–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong JC, Alon N, McKerlie C, et al. Targeted disruption of exons 1 to 6 of the Fanconi Anemia group A gene leads to growth retardation, strain-specific microphthalmia, meiotic defects and primordial germ cell hypoplasia. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:2063–2076. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang Y, Kuang Y, Montes De Oca R, et al. Targeted disruption of the murine Fanconi anemia gene, Fancg/Xrcc9. Blood. 2001;98:3435–3440. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agoulnik AI, Lu B, Zhu Q, et al. A novel gene, Pog, is necessary for primordial germ cell proliferation in the mouse and underlies the germ cell deficient mutation, Gcd. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:3047–3053. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.24.3047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Houghtaling S, Timmers C, Noll M, et al. Epithelial cancer in Fanconi anemia complementation group D2 (Fancd2) knockout mice. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2021–2035. doi: 10.1101/gad.1103403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Navarro S, Meza NW, Quintana-Bustamante O, et al. Hematopoietic dysfunction in a mouse model for Fanconi anemia group D1. Mol Ther. 2006;14:525–535. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parmar K, D’Andrea A, Niedernhofer LJ. Mouse models of Fanconi anemia. Mutat Res. 2009;668:133–140. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2009.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carreau M, Gan OI, Liu L, et al. Hematopoietic compartment of Fanconi anemia group C null mice contains fewer lineage-negative CD34+ primitive hematopoietic cells and shows reduced reconstruction ability. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1667–1674. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haneline LS, Gobbett TA, Ramani R, et al. Loss of FancC function results in decreased hematopoietic stem cell repopulating ability. Blood. 1999;94:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Carreau M, Gan OI, Liu L, et al. Bone marrow failure in the Fanconi anemia group C mouse model after DNA damage. Blood. 1998;91:2737–2744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zambrowicz BP, Friedrich GA, Buxton EC, et al. Disruption and sequence identification of 2,000 genes in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1998;392:608–611. doi: 10.1038/33423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kennedy RD, Chen CC, Stuckert P, et al. Fanconi anemia pathway-deficient tumor cells are hypersensitive to inhibition of ataxia telangiectasia mutated. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1440–1449. doi: 10.1172/JCI31245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kondo M, Scherer DC, King AG, et al. Lymphocyte development from hematopoietic stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:520–526. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, et al. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kiel MJ, Yilmaz OH, Iwashita T, et al. SLAM family receptors distinguish hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells and reveal endothelial niches for stem cells. Cell. 2005;121:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson A, Laurenti E, Oser G, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells reversibly switch from dormancy to self-renewal during homeostasis and repair. Cell. 2008;135:1118–1129. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ploemacher RE, van der Sluijs JP, van Beurden CA, et al. Use of limiting-dilution type long-term marrow cultures in frequency analysis of marrow-repopulating and spleen colony-forming hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse. Blood. 1991;78:2527–2533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ploemacher RE, van der Sluijs JP, Voerman JS, et al. An in vitro limiting-dilution assay of long-term repopulating hematopoietic stem cells in the mouse. Blood. 1989;74:2755–2763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrison DE. Competitive repopulation: A new assay for long-term stem cell functional capacity. Blood. 1980;55:77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aube M, Lafrance M, Brodeur I, et al. Fanconi anemia genes are highly expressed in primitive CD34+ hematopoietic cells. BMC Blood Disord. 2003;3:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2326-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leteurtre F, Li X, Guardiola P, et al. Accelerated telomere shortening and telomerase activation in Fanconi’s anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:883–893. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ridpath JR, Nakamura A, Tano K, et al. Cells deficient in the FANC/BRCA pathway are hypersensitive to plasma levels of formaldehyde. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11117–11122. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niedernhofer LJ, Daniels JS, Rouzer CA, et al. Malondialdehyde, a product of lipid peroxidation, is mutagenic in human cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31426–31433. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212549200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Shang X, Guo F, et al. Defective homing is associated with altered Cdc42 activity in cells from patients with Fanconi anemia group A. Blood. 2008;112:1683–1686. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Plett PA, Yang Y, et al. Fanconi anemia type C-deficient hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells exhibit aberrant cell cycle control. Blood. 2003;102:2081–2084. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li Y, Chen S, Yuan J, et al. Mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells promote the reconstitution of exogenous hematopoietic stem cells in Fancg−/− mice in vivo. Blood. 2009;113:2342–2351. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li X, Yang Y, Yuan J, et al. Continuous in vivo infusion of interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) preferentially reduces myeloid progenitor numbers and enhances engraftment of syngeneic wild-type cells in Fancc−/− mice. Blood. 2004;104:1204–1209. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dufour C, Corcione A, Svahn J, et al. TNF-alpha and IFN-gamma are overexpressed in the bone marrow of Fanconi anemia patients and TNF-alpha suppresses erythropoiesis in vitro. Blood. 2003;102:2053–2059. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-01-0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sejas DP, Rani R, Qiu Y, et al. Inflammatory reactive oxygen species-mediated hemopoietic suppression in Fancc-deficient mice. J Immunol. 2007;178:5277–5287. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.8.5277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Du W, Adam Z, Rani R, et al. Oxidative stress in Fanconi anemia hematopoiesis and disease progression. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1909–1921. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rani R, Li J, Pang Q. Differential p53 engagement in response to oxidative and oncogenic stresses in Fanconi anemia mice. Cancer Res. 2008;68:9693–9702. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niedernhofer LJ. DNA repair is crucial for maintaining hematopoietic stem cell function. DNA Repair (Amst) 2008;7:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rossi DJ, Bryder D, Seita J, et al. Deficiencies in DNA damage repair limit the function of haematopoietic stem cells with age. Nature. 2007;447:725–729. doi: 10.1038/nature05862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nijnik A, Woodbine L, Marchetti C, et al. DNA repair is limiting for haematopoietic stem cells during ageing. Nature. 2007;447:686–690. doi: 10.1038/nature05875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reese JS, Liu L, Gerson SL. Repopulating defect of mismatch repair-deficient hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2003;102:1626–1633. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-10-3035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prasher JM, Lalai AS, Heijmans-Antonissen C, et al. Reduced hematopoietic reserves in DNA interstrand crosslink repair-deficient Ercc1−/− mice. EMBO J. 2005;24:861–871. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ito K, Hirao A, Arai F, et al. Regulation of oxidative stress by ATM is required for self-renewal of haematopoietic stem cells. Nature. 2004;431:997–1002. doi: 10.1038/nature02989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bender CF, Sikes ML, Sullivan R, et al. Cancer predisposition and hematopoietic failure in Rad50(S/S) mice. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2237–2251. doi: 10.1101/gad.1007902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.