Abstract

BACKGROUND

MUC4 is aberrantly expressed in colorectal adenocarcinomas (CRCs), but its prognostic value is unknown.

METHODS

Archival tissue specimens collected from 132 CRC patients, who underwent surgical resection without pre- or post-surgery therapy, were evaluated for expression of MUC4 by use of a mouse monoclonal antibody and horseradish peroxidase. The expression levels were correlated with clinicopathologic features and patient survival. Survival was estimated by both univariate Kaplan-Meier and multivariate Cox regression methods.

RESULTS

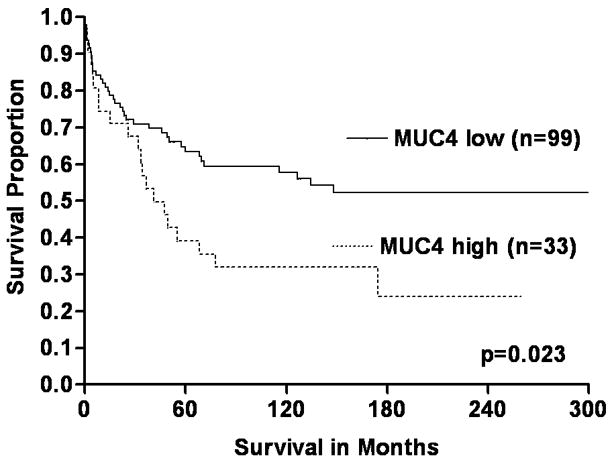

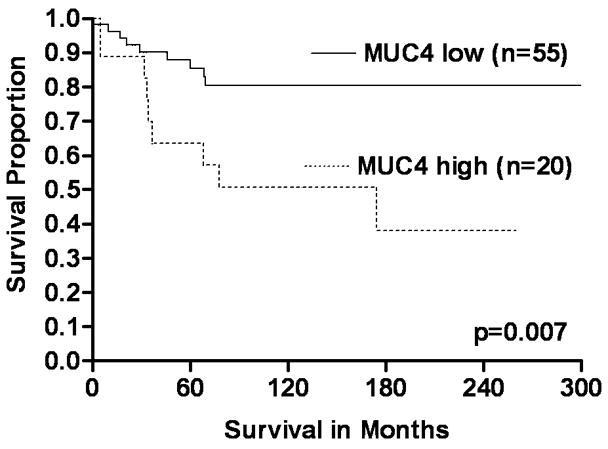

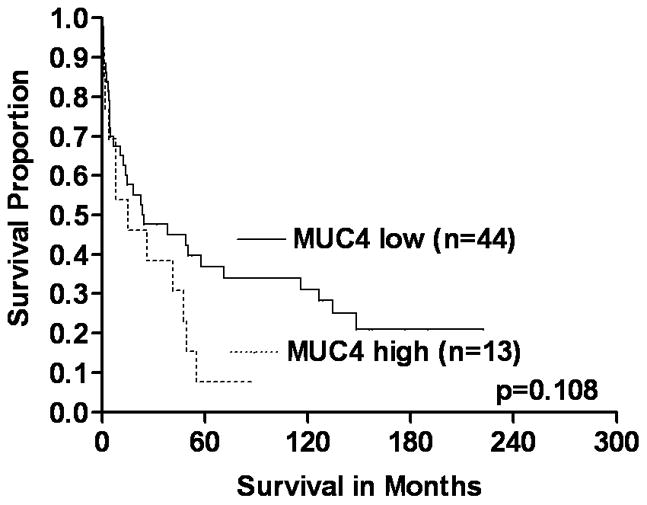

In both normal colonic epithelium and CRCs, MUC4 staining was primarily localized in the cytoplasm. The optimal immunostaining cutoff (≥75% positive cells and ≥2.0 ISS), derived by the bootstrap method, was used to categorize CRCs into groups of high- (33 of 132, 25%) or low-expression (99 of 132, 75%). Patients with early-stage tumors (I & II) with high MUC4 expression had a shorter disease-specific survival (log-rank, p=0.007) than those with low expression. Patients with advanced-stage CRCs (III & IV) did not demonstrate such a difference (log-rank, p=0.108). The multivariate regression models generated separately for early- and advanced-stage patients confirmed that increased expression of MUC4 was an independent indicator of a poor prognosis only for patients with early-stage CRCs (hazard ratio, 3.77; confidence interval, 1.46–9.73).

CONCLUSIONS

Increased MUC4 expression is a predictor of poor survival in CRC, specifically for patients with early stage tumors.

Keywords: MUC4, Colorectal Adenocarcinomas, Early-Stage, Prognosis, Survival

INTRODUCTION

Mucins are complex glycoproteins, subdivided into two structural and functional classes: secreted, gel-forming mucins (MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B, and MUC6) and transmembrane mucins (MUC1, MUC3A, MUC3B, MUC4, MUC11, MUC12, and MUC17). The products of some MUC genes (MUC7, MUC8, MUC9, MUC13, MUC15, MUC16) do not fit well into either class.1 In addition to being protective at the surface epithelium, altered expression of some of these mucins is associated with neoplastic progression and metastasis of various cancers, including colorectal cancers (CRCs).1–3

MUC4 is a transmembrane mucin located at chromosome locus 3q29. Although originally considered to be of tracheobronchial origin, it is located in normal stomach, ovary, salivary gland, colon, lung, uterus and prostate.1 MUC4 expression in lungs occur before organogenesis; in the jejunum and colon, it is expressed at 6.5 weeks of gestation.4 In the esophagus, expression correlates with stages of squamous cell differentiation.4 MUC4 has a mucin-like subunit, MUC4α, which has glycosylated tandem repeats, and MUC4β, which consists of three epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains and a short cytoplasmic tail.5 MUC4 expression is partially regulated by pathways associated with interferon-γ, retinoic acid and transforming growth factor-β signaling.4

MUC4 is implicated in the induction of ultrastructural changes in the transformation of normal epithelium and with tumorigenicity.6 It is also implicated in reducing accessibility of the tumor cell surface antigen to cytotoxic immune cells, thus aiding in evasion of the host immune response.7 With its EGF-like domains, MUC4 acts as a modulator of HER2/ErbB2 receptor tyrosine kinase and potentiates tumorigenesis and/or tumor growth in pancreatic4, 8 and gallbladder carcinomas.9 Further, MUC4 over-expression confers apoptotic resistance to tumor cells.10, 11 These characteristics indicate that MUC4 has multiple roles in tumor development and progression.

There is aberrant expression of MUC4 in malignancies of the gallbladder,9 biliary tract,12 lung,13, 14 salivary gland,15–17 pancreas,18, 19 ovary,18–20 and prostate.21 The prognostic significance of MUC4 expression is tissue-dependant and varies with the type of malignancy; for example, its expression in mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the salivary gland is associated with improved patient survival and late disease recurrence.15, 17 Its expression in lung adenocarcinomas, however, is associated with increased recurrence of disease and poor survival.14

Since the prognostic significance of MUC4 expression had not been studied in colorectal adenocarcinomas (CRCs), we determined the phenotypic expression of MUC4 in retrospective CRC tissues and correlated the extent of its expression with clinicopathological features and with patient survival based on tumor stage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient Population

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) approved this study. A total of 132 CRC patients who had undergone surgical resection for “first primary” CRC at the UAB Hospital between 1981 and 1993 were identified. As described below, the sample size and power were estimated based on a previous study.12 The retrospective samples were collected from an ‘unselected’ patient population. The use of patients from this time period allowed maximized post-surgery follow-up. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks from these patients were obtained from the Anatomic Pathology Division at UAB.

Those patients with surgical margin-involvement, unspecified tumor location, multiple primaries within the colorectum, or multiple malignancies; with a family history of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP); and those with family and/or personal histories of CRC were excluded. Since, based on information in patient charts, it was difficult to identify the familial vs. sporadic nature of CRCs, this retrospective cohort is a ‘consecutive’ patient population. Included were patients who had undergone surgery alone as a therapeutic intervention across all tumor stages (I–IV); excluded were those who received pre- or postsurgical chemo- or radiation therapy to control for treatment bias. Some patients with CRCs at stage III or IV did not receive adjuvant therapy but were subjected to surgery with a palliative intent.

Pathological Features

The surgical pathology reports were reviewed by three pathologists (CKS, NCJ & WEG), who individually reviewed slides stained with hematoxylin and eosin for the degree of histologic differentiation and re-graded lesions as well, moderate, poor or undifferentiated.22, 23 Cases with disagreement were resolved by re-evaluating the slides to reach a consensus. Well and moderately differentiated tumors were pooled into a low-grade group, and poor and undifferentiated tumors into a high-grade group.24 Pathologic staging was performed according to the criteria of the American Joint Commission on Cancer.25 The International Classification of Diseases for Oncology codes were used to specify the anatomic location of the tumor.22 The tumor was considered mucinous if ≥50% demonstrated mucinous histology.22 The anatomic sub-sites were the proximal colon, the distal colon and the rectum. Three-dimensional tumor size was determined; the largest dimension was used for statistical purposes.

Patient Demographics and Follow-Up Information

Patient demographics, along with clinical and follow-up information, were retrieved retrospectively from medical records, physician charts, and pathology reports and from the UAB tumor registry. Patients were followed either by the patients’ physician or by personnel associated with the tumor registry until their death or the date of the last documented contact. Through telephone and mail contacts, these personnel ascertained outcome (mortality) information directly from patients (or relatives) and physicians. This information was validated by examination of the state death registry. Demographic data, including patient age at diagnosis, gender, race/ethnicity, date of surgery, date of the last follow-up (if alive), date of recurrence (if any) and date of death, were collected. Collection of follow-up information, performed every six months, has ended in April 2009. Laboratory investigators (CKS & VRK) were blinded to the outcome information until completion of the assays.

Immunohistochemical Analysis

Tissue sections (5 μm) were cut from FFPE blocks representative of normal and tumor tissue of each case and were mounted on Superfrost/Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA). These sections were cut 1–2 days prior to immunostaining to avoid problems in antigen recognition due to storage.26 Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was performed as described previously.3, 27, 28 In brief, the sections were melted, incubated overnight at 37 °C, deparaffinized in xylene, rehydrated in graded alcohols, and transferred to a Tris-buffer bath (0.05 M Tris base, 0.15 M NaCl and 0.01% Triton X-100, pH 7.6). Antigen retrieval was accomplished by placing the slides in a pressure cooker for 10 min with EDTA buffer (EDTA 2.1 g, H2O 1000 ml, adjusting to pH 9 with NaOH). Each section was treated with 3% H2O2 for 5 min to quench the endogenous peroxidase activity and incubated with 3% goat serum at room temperature for 1 hr to reduce non-specific immunostaining. The sections were incubated with anti-human MUC4 mouse monoclonal antibody (clone 8G7) diluted at 1:1500 ratio. This dilution was determined after initial standardization. This antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Surinder K. Batra (University of Nebraska at Omaha, NE) and was characterized for its epitope (tandem repeat region-STGDTTPLPVTDTSSV) recognition and specificity.29 Sections on which the primary antibody was not applied served as controls.

Secondary detection was accomplished with a multi-species system (Signet Lab Inc., Dedham, MA). The sections were exposed to biotinylated multispecies antibodies, including anti-mouse antibodies, for 20 min, and then incubated with peroxidase-labeled streptavidin for 20 min. A diaminobenzidine tetrachloride super-sensitive substrate kit (BioGenex, San Ramon, CA) was used to visualize the antibody-antigen complex. Each section was counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated by graded concentrations of alcohol, and soaked in xylene before cover-slips were applied.

Slides were evaluated for MUC4 staining independently by three Pathologists (CKS, NCJ & WEG); if there was a discrepancy in individual scores, all three re-evaluated the slides together to reach a consensus before combining the individual scores. A semi-quantitative immunostaining score (ISS) for MUC4 was obtained as described previously. 3, 27, 28 In brief, each of the pathologists estimated the proportion of cells stained and the intensity of staining in the whole section. The intensity of immunostaining of individual cells was scored on a scale of 0 (no staining) to 4 (strongest intensity). Each pathologist estimated the proportion of cells stained at each intensity. The percent of cells at each intensity was multiplied by the corresponding intensity value to obtain an immunostaining score ranging from 0 to 4. The scores were combined to obtain an overall mean ISS.

Statistical Methods

Sample Size and Power Calculations

The sample size and power analysis were estimated based on a MUC4 immunohistochemistry study with extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma 12. In that study, increased expression of MUC4 was a poor prognostic indicator of survival, and 19 of 70 patients (27%) were positive for MUC4. The hazard ratio observed was 2.87 (p=0.0072). Thus, we proposed to evaluate 132 samples from patients with CRC for MUC4. Based on the published results,12 there was enough power to detect a hazard ratio ≥ 2.87. Therefore, the sample size (n=132) was sufficient to identify a statistically significant prognostic value for MUC4 expression.

Determination of the Optimal MUC4 Immunostaining Cutoff Point

Bootstrap method, as described below, was used to find an optimal cutoff-point of MUC4 staining that could be used to categorize tumors into groups of low and high expression. A Cox regression model was used to evaluate the results of the optimal cutoff-point determined by this method, after adjusting for other covariates as mentioned below (in the Statistical analyses section). The optimal cutoff point was the one with the highest statistical significance of MUC4 among the Cox models.

The bootstrap re-sampling procedure was used to assess the internal validity of the log-rank test for cutoff-point analysis. Two hundred different bootstrap samples were randomly drawn with replacement from the original dataset (n=132). The Kaplan-Meier (KM) analysis was repeated in each sample for each cutoff-point value, and the p-value of the log-rank test was recorded. The most frequent cutoff-off value (mode) among the optimal cutoff-point values were considered as an optimal cutoff-point value that resulted in lowest p-value in the subsequent Cox regression models generated for each cutoff-point. A cutoff-point ≥75% and ≥2.0 ISS was associated with the lowest p-value of 0.017 and was chosen for dichotomizing tumors into MUC4 high (≥75% and ≥2.0 ISS) and low (<75% and <2.0 ISS) expressors.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square analyses were used to assess the univariate associations of baseline characteristics with MUC4 expression. The group with low expression included cases that lacked staining. The baseline characteristics included were demographic variables (age and gender), pathologic variables (tumor location, size, histologic type, differentiation, and stage), and MUC4 status. The type I error rate of each test was controlled at <0.05. All analyses were performed with SAS statistical software version 9.0.30

Survival analysis was used to model time from date of surgery until death due to CRC. Deaths were the outcomes (events) of interest. Those patients who died of causes other than CRC and those who were alive at the end of the study were considered to be censored. Log-rank tests and KM survival curves31 were used to compare low and high MUC4 expression in each group of patients with early or low (stages I & II) and advance or high (stages III & IV) disease. The type I error rate of each test was controlled at <0.05.

In addition to the primary analysis determining the effect of MUC4 phenotypic expression described above, secondary analyses were performed to consider covariates known to be potential confounders or independent risk factors for death. These included age, gender, tumor location, tumor stage, tumor size, and tumor differentiation. For these analyses, Cox regressions32 were used within each group (early and advance stage), with a final Cox model including those covariates for which p<0.05.

RESULTS

Study Cohort Characteristics

Clinicopathological features are listed in Table 1. The mean age of the patients in the study cohort at the time of surgery was 65 years. At the last follow-up, the proportion of patients who were alive was 24% (32 of 132), dead due to CRC was 46% (61 of 132), and dead due to other causes was 30% (39 of 132).

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathological Features of the Study Cohort (N= 132)

| Variable | Number of patients (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group (years) | |

| < 65 | 63 (48) |

| ≥ 65 | 69(52) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 57 (43) |

| Male | 75 (57) |

| Ethnicity | |

| African-Americans | 45 (34) |

| Non-Hispanic Caucasians | 87 (66) |

| Tumor location | |

| Proximal colon | 59 (45) |

| Distal colon | 48 (36) |

| Rectum | 25 (19) |

| Tumor stage | |

| I | 23 (17) |

| II | 52 (40) |

| III | 40 (30) |

| IV | 17 (13) |

| Tumor grade | |

| Low | 97 (73) |

| High | 35 (27) |

| Tumor size (cm) | |

| < 5 | 46 (35) |

| ≥ 5 | 86 (65) |

| Tumor type | |

| Mucinous | 37 (28) |

| Non-mucinous | 95 (72) |

| Vital status (at follow-up) | |

| Alive | 32 (24) |

| Death due to CRC | 61 (46) |

| Death due to unknown cause or other than CRC | 39 (30) |

| Expression of MUC4 | |

| Low | 99 (75) |

| High | 33 (25) |

MUC4 Expression

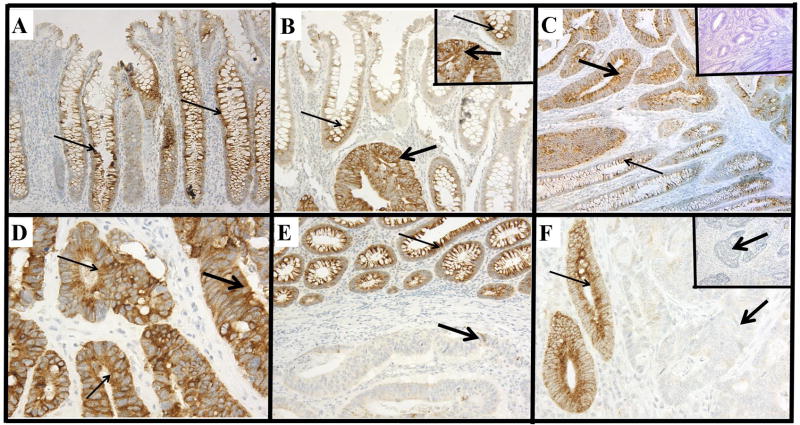

The phenotypic expression patterns of MUC4 are shown in Figure 1. In all cases, the normal colonic epithelium exhibited moderate cytoplasmic MUC4 expression with accentuated staining in the lower two-thirds of the normal crypts (Figures 1A & B). In CRCs, expression was observed predominantly in the cytoplasm. However, a small proportion of CRCs (17 of 132, 13%) exhibited membrane staining along with cytoplasmic staining (Figures 1D, thin arrows). Based on the cutoff-point, the CRCs were categorized into groups of low (99 of 132, 75%) and high expression (33 of 132, 25%) (Table 1). MUC4 staining was absent in 8 (6%) CRCs, but their corresponding normal tissues exhibited moderate staining (Figure 1F). The correlations between MUC4 expression status and clinicopathological features are shown in Table 2. Most (67%) patients in the older age groups demonstrated increased expression of MUC4 in their CRCs. Higher expression was observed in males (61%) compared to females (39%). For patients with high expression, 64% died due to CRC compared to 41% of those with decreased expression (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

Immunohistochemical expression patterns of MUC4.

A, normal colonic epithelium demonstrating cytoplasmic MUC4 staining (200 μm) (note: accentuation of staining in the lower two-thirds of the normal crypts). B, colorectal adenocarcinoma exhibiting stronger cytoplasmic immunostaining (thick arrows) than the adjacent normal colonic epithelium (400 μm) (thin arrows) (Inset: higher magnification, 600 μm). C, a CRC with strong cytoplasmic staining (thick arrows); the adjacent normal epithelium demonstrates moderate staining (thin arrows) (200 μm) (Inset: same area in another section on which primary antibody was not applied) (200 μm). D, a CRC with strong cytoplasmic staining (thick arrows) also exhibits mild to moderate membrane staining (thin arrows) (600 μm). E, a CRC demonstrating weak cytoplasmic staining (thick arrows) as compared to the strong staining of adjacent normal colonic epithelium (thin arrows) (200 μm). F, a CRC exhibiting a absence of immunostaining (thick arrows) and adjacent normal colonic crypts exhibiting strong cytoplasmic staining (thin arrows) (Inset: 400 μm, a CRC with a lack of immunostaining) (400 μm).

TABLE 2.

Association Between MUC4 Expression and Clinicopathological Characteristics

| Number of patients (N=132) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | MUC4 low expression 99 (75%) | MUC4 high expression 33 (25%) | χ2 P-value |

| Age group (years) | |||

| < 65 | 52 (53) | 11 (33) | 0.055 |

| ≥ 65 | 47 (47) | 22 (67) | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 44 (44) | 13 (39) | 0.612 |

| Male | 55 (56) | 20 (61) | |

| Ethnicity | |||

| African-Americans | 30 (30) | 15 (45) | 0.111 |

| Non-Hispanic Caucasians | 69 (70) | 18 (55) | |

| Tumor location | |||

| Proximal colon | 42 (42) | 17 (52) | 0.454 |

| Distal colon | 39 (39) | 9 (27) | |

| Rectum | 18 (19) | 7 (21) | |

| Tumor stage | |||

| I | 17 (17) | 6 (18) | 0.965 |

| II | 38 (38) | 14 (42) | |

| III | 31 (32) | 9 (27) | |

| IV | 13 (13) | 4 (13) | |

| Tumor grade | |||

| Low | 74 (75) | 23 (70) | 0.569 |

| High | 25 (25) | 10 (30) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| < 5 | 31 (31) | 15 (45) | 0.139 |

| ≥ 5 | 68 (69) | 18 (55) | |

| Tumor type | |||

| Mucinous | 25 (25) | 12 (36) | 0.264 |

| Non-mucinous | 74 (75) | 21 (64) | |

| Vital status (at follow-up) | |||

| Alive | 26 (26) | 6 (18) | 0.064 |

| Death due to CRC | 40 (41) | 21 (64) | |

| Death due to unknown cause or other than CRC | 33 (33) | 6 (18) | |

Survival Analyses

Univariate KM survival analyses of the complete study cohort (n=132), based on MUC4 expression, demonstrated that CRCs with increased expression were significantly associated with shortened disease-specific survival compared to those with low expression (log rank, p=0.023) (Figure 2A). Survival analyses to assess the significance of MUC4 expression based on tumor stage (early and advance) demonstrated that patients with early-stage (I & II) CRCs with high MUC4 expression had a significantly shorter disease-specific survival than those with CRCs with low expression (log-rank, p=0.007) (Figure 2B). Although patients with advanced-stage CRCs (III &IV) demonstrated a similar pattern in the survival curves, the survival difference was not statistically significant (log-rank, p=0.108) (Figure 2C). Univariate survival analyses based on MUC4 expression status and other parameters of patients (age at diagnosis, gender, and ethnicity/race) or tumors (location, size and grade) were not statistically significant (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

The significance of MUC4 expression status on survival of early and advanced stage patients with CRCs (KM survival curves). A Overall, CRC patients with increased (high) MUC4 expression had short survival compared to low expressors (log-rank, p=0.023). B & C In early stage CRCs (B), high expression of MUC4 was significantly associated with poor survival of patients (log-rank, p=0.007) relative to low expressors. However, there was no such difference in CRCs with advanced stages (C) (log-rank, p=0.108).

The independent prognostic significance of MUC4 expression on CRC-specific survival was evaluated with a Cox regression model. These multivariate models confirmed the independent effect of MUC4 on CRC-specific survival (Table 3). A multivariate model developed for the complete study cohort (n=132) demonstrated that patients with increased expression of MUC4 were 2.07 times (hazard ratio [HR=2.07]; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.14–3.75) more likely to die of CRC than low expressors (Table 3). These analyses indicated that MUC4 expression and tumor stage were independent prognostic indicators of CRC (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Cox Regression Analysis to Assess Prognostic Significance of MUC4 Expression

| Prognostic variables | Indicator of poor prognosis | Hazard ratio 95% (confidence intervals) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | |||

| Expression of MUC4 | |||

| MUC4 (low vs. high expression) | high expression | 2.07 (1.14–3.75) | 0.017 |

| Tumor stage | |||

| I vs. II | II | 1.34 (0.46–3.85) | 0.582 |

| I vs. III | III | 4.95 (1.84–13.27) | 0.001 |

| I vs. IV | IV | 14.15 (4.64–43.10) | < 0.0001 |

| Tumor grade | |||

| high vs. low | high grade | 1.47 (0.77–2.78) | 0.243 |

| Tumor location | |||

| proximal vs. distal colon | proximal colon | 0.92 (0.64–1.31) | 0.644 |

| Tumor size | |||

| > 5 cm vs. ≤ 5 cm | > 5 cm | 1.12 (0.63–1.97) | 0.693 |

| Tumor type | |||

| mucinous vs. non-mucinous | mucinous | 1.37 (0.73–2.59) | 0.321 |

| Early stage (Stage I & II) | |||

| MUC4 (low vs. high expression) | high expression | 3.77 (1.46–9.73) | 0.006 |

| Tumor grade (high vs. low) | high grade | 2.91 (1.00–8.44) | 0.049 |

| Advanced stage (Stage III & IV) | |||

| MUC4(low vs. high expression) | high expression | 1.74 (0.87–3.45) | 0.113 |

The multivariate regression models generated separately for early and advanced tumor stages demonstrated that increased expression of MUC4 is an independent indicator of a poor prognosis only in patients with early stage CRCs (Table 3). The hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for early stage were 3.77 and 1.46–9.73, respectively. For early-stage CRCs, tumor grade was also significantly associated with patient survival (HR, 2.91; CI, 1.00–8.44). The prognostic significance of MUC4 in advanced stage CRCs, however, was not statistically significant (HR, 1.74; CI, 0.87–3.45).

DISCUSSION

The current study, to our knowledge, is the first to report the prognostic value of phenotypic expression of MUC4 in primary CRCs. In general, MUC4 expression was observed in the cytoplasm of both normal colonic epithelium and CRCs. Some CRCs demonstrated membrane staining in addition to cytoplasmic localization. High expression of MUC4 was noted in 25% of CRCs. Survival analyses based on tumor stage indicated that MUC4 expression was associated with shortened survival of patients with early-stage but not with advanced-stage CRCs. These findings were confirmed in multivariate Cox regression analyses, suggesting that high MUC4 expression is an independent indicator of poor prognosis for patients with CRCs.

As observed in the current study, earlier investigations have reported cytoplasmic staining of MUC4 in normal colonic epithelium with an accentuated staining in the lower two-thirds of the normal crypts.33 In our study, increased expression of cytoplasmic MUC4, relative to normal epithelium, was observed in 25% of CRCs. Similar increased expression of MUC4 at mRNA level was reported in CRCs compared to normals.34 The present study found, in addition to its cytoplasmic localization, membrane staining in 13% of cases. A previous study with lung cancer13 demonstrated staining in the cytoplasm (33%), the membrane (9%) or both (58%). In pancreatic and extrahepatic bile-duct cancers, MUC4 staining was primarily in the cytoplasm.12, 35 In the current study, CRCs have demonstrated either a decreased (69%) or a complete lack (6%) of expression of MUC4. This decreased or lack of expression can be attributed to epigenetic mechanisms (DNA hypermethylation and histone modifications), as demonstrated in earlier studies of pancreas and gastric cancer cells.36 However, such a relationship (hypermethylation) was shown only in some colon cancer cells.37 These findings suggested that regulation of MUC4 expression is not organ-specific, but varies in individual cancer cells.

Aberrant expression of MUC4 in lung and pancreatic cancers has been evaluated as a diagnostic marker.35, 38 Over-expression of MUC4 was observed in pancreatic adenocarcinomas; its expression was undetectable in normal pancreas or in chronic pancreatitis.18, 19, 35, 39, 40 Thus, MUC4 could be used as an early diagnostic marker of pancreatic adenocarcinomas.35 Additionally, MUC4 has been used to differentiate lung adenocarcinomas from malignant mesothelioma in pleural effusions.38 Since, in our study, the expression of MUC4 was seen in the normal colonic epithelium and in CRCs, MUC4 cannot be used as a diagnostic marker.

The expression of MUC4 and its prognostic significance have been demonstrated in cancers of the biliary tract,12 lungs,13, 14 salivary glands,15–17 pancreas,18, 19 ovaries18–20 and prostate.21 However, its prognostic value has not been assessed in CRCs. In this study, we observed a significant association between increased MUC4 expression and poor patient survival both in univariate and multivariate survival analyses. Similarly, increased expression of MUC4 was associated with poor survival of patients with extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma12 and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.41 For ovarian carcinomas,20 increased MUC4 expression was associated with a trend towards poor survival. For mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the salivary glands, increased expression of MUC4 was not associated with prognosis.16 In contrast, high MUC4 expression was associated with longer patient survival and late disease recurrence in mucoepidermoid carcinomas of the salivary gland.15, 17 Similarly, in squamous cell carcinomas of the upper aero-digestive tract, MUC4 expression was associated with longer patient survival and a decreased rate of recurrence.42 However, in lung14 and pancreatic adenocarcinomas,43 MUC4 expression was associated with shortened disease-free and overall patient survival. These conflicting results on the prognostic value of MUC4 in different malignances indicate that its prognostic significance is tissue-dependant and varies with the type of malignancy.

In the present study, stage-based survival analyses showed that only early stage (I & II) CRCs with increased expression of MUC4 were significantly associated with shortened patient survival. Similarly, increased expression of MUC4 was associated with poor survival of early stage (IA), lung14 and ovarian carcinoma20 patients. Furthermore, in lung adenocarcinomas, the corresponding normal epithelium consistently expressed MUC4,14, 38 as was observed in the current study. Statistically significant survival difference was not observed for patients with advanced stage (III & IV) CRCs, even though a similar pattern of survival association was observed with MUC4 expression. The multivariate regression models generated separately for early and advanced tumor stages confirmed that increased expression of MUC4 as an independent indicator for poor prognosis only in patients with early stage CRCs. However, further larger studies are needed to assess MUC4 prognostic value in patients with advance stage CRCs. Although the basis for MUC4’s prognostic value in early, but not advanced-stage CRCs, is not known, MUC4 expression might have distinct roles in different phases of CRC progression, as observed a gradual increase of expression of NF-kappa B and loss of Bcl-2 expression from adenoma to adenocarcinomas.44 Similarly, MUC4 could be involved in progression of early-stage tumors more than in advanced-stage CRCs. Although this report demonstrates prognostic implications of MUC4 expression in a cohort of CRC patients, it does not elucidate the role of MUC4 expression in CRC development.

In the current study, tumor grade also emerged as an important prognostic indicator in early-stage but not in advanced-stage CRCs. Despite the subjective nature of the histological grading and considerable inter-observer variability, tumor grade is an independent prognostic factor in CRC.45, 46 In general, patients with advanced-stage CRCs (III & IV) have a poorer prognosis than those with early stages (I & II); however, a sub-set of patients with stage II CRCs have an increased risk of early recurrence and death. The underlying molecular mechanisms for these aggressive, early-stage CRCs are complex; however, identification of this high-risk subset would be important in the selection of patients for appropriate treatment. In such instances, determination of the MUC4 expression status should aid in identifying patients with aggressive forms of CRCs and help in designing individualized therapies.

In summary, moderate levels of MUC4 expression were observed in uninvolved colonic epithelium, but, in CRCs, expression levels varied from high to none. Univariate and multivariate survival analyses indicated that increased MUC4 expression was associated with poor patient survival, specifically for those with early-stage CRCs. After validating these findings in larger retrospective and prospective studies, the stage-based analyses could establish the utility of MUC4 as a prognostic molecular marker of early-stage CRCs. Further, use of MUC4 as a marker should aid clinicians in identifying patients with aggressive forms of early-stage CRCs.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources- This work was supported by funds from the National Institute of Health/National Cancer Institute to Dr. Manne (RO1-CA98932-01, R03-CA139629-01, and 2U54-CA118948-03) and to Dr. Grizzle (U24-CA086359).

We thank Donald L. Hill, Ph.D., Department of Preventive Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, for his critical review of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Byrd JC, Bresalier RS. Mucins and mucin binding proteins in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23(1–2):77–99. doi: 10.1023/a:1025815113599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ajioka Y, Allison LJ, Jass JR. Significance of MUC1 and MUC2 mucin expression in colorectal cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49(7):560–4. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.7.560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manne U, Weiss HL, Grizzle WE. Racial differences in the prognostic usefulness of MUC1 and MUC2 in colorectal adenocarcinomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6(10):4017–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Batra SK. Structure, evolution, and biology of the MUC4 mucin. Faseb J. 2008;22(4):966–81. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9673rev. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh AP, Chaturvedi P, Batra SK. Emerging roles of MUC4 in cancer: a novel target for diagnosis and therapy. Cancer Res. 2007;67(2):433–6. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moniaux N, Chaturvedi P, Varshney GC, Meza JL, Rodriguez-Sierra JF, Aubert JP, et al. Human MUC4 mucin induces ultra-structural changes and tumorigenicity in pancreatic cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2007;97(3):345–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Burchell JM, Plunkett T, Graham R, Correa I, Miles D, et al. MUC1 and the immunobiology of cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2002;7(2):209–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1020360121451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Chakraborty S, Chauhan SC, Bafna S, Meza JL, et al. MUC4 mucin interacts with and stabilizes the HER2 oncoprotein in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(7):2065–70. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miyahara N, Shoda J, Ishige K, Kawamoto T, Ueda T, Taki R, et al. MUC4 interacts with ErbB2 in human gallbladder carcinoma: potential pathobiological implications. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(7):1048–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaturvedi P, Singh AP, Moniaux N, Senapati S, Chakraborty S, Meza JL, et al. MUC4 mucin potentiates pancreatic tumor cell proliferation, survival, and invasive properties and interferes with its interaction to extracellular matrix proteins. Mol Cancer Res. 2007;5(4):309–20. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-06-0353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Komatsu M, Jepson S, Arango ME, Carothers Carraway CA, Carraway KL. Muc4/sialomucin complex, an intramembrane modulator of ErbB2/HER2/Neu, potentiates primary tumor growth and suppresses apoptosis in a xenotransplanted tumor. Oncogene. 2001;20(4):461–70. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tamada S, Shibahara H, Higashi M, Goto M, Batra SK, Imai K, et al. MUC4 is a novel prognostic factor of extrahepatic bile duct carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(14 Pt 1):4257–64. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon KY, Ro JY, Singhal N, Killen DE, Sienko A, Allen TC, et al. MUC4 expression in non-small cell lung carcinomas: relationship to tumor histology and patient survival. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131(4):593–8. doi: 10.5858/2007-131-593-MEINCL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsutsumida H, Goto M, Kitajima S, Kubota I, Hirotsu Y, Wakimoto J, et al. MUC4 expression correlates with poor prognosis in small-sized lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2007;55(2):195–203. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alos L, Lujan B, Castillo M, Nadal A, Carreras M, Caballero M, et al. Expression of membrane-bound mucins (MUC1 and MUC4) and secreted mucins (MUC2, MUC5AC, MUC5B, MUC6 and MUC7) in mucoepidermoid carcinomas of salivary glands. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(6):806–13. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000155856.84553.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Handra-Luca A, Lamas G, Bertrand JC, Fouret P. MUC1, MUC2, MUC4, and MUC5AC expression in salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma: diagnostic and prognostic implications. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(7):881–9. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000159103.95360.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weed DT, Gomez-Fernandez C, Pacheco J, Ruiz J, Hamilton-Nelson K, Arnold DJ, et al. MUC4 and ERBB2 expression in major and minor salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Head Neck. 2004;26(4):353–64. doi: 10.1002/hed.10387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrianifahanana M, Moniaux N, Schmied BM, Ringel J, Friess H, Hollingsworth MA, et al. Mucin (MUC) gene expression in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis: a potential role of MUC4 as a tumor marker of diagnostic significance. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7(12):4033–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moniaux N, Andrianifahanana M, Brand RE, Batra SK. Multiple roles of mucins in pancreatic cancer, a lethal and challenging malignancy. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(9):1633–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chauhan SC, Singh AP, Ruiz F, Johansson SL, Jain M, Smith LM, et al. Aberrant expression of MUC4 in ovarian carcinoma: diagnostic significance alone and in combination with MUC1 and MUC16 (CA125) Mod Pathol. 2006;19(10):1386–94. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh AP, Chauhan SC, Bafna S, Johansson SL, Smith LM, Moniaux N, et al. Aberrant expression of transmembrane mucins, MUC1 and MUC4, in human prostate carcinomas. Prostate. 2006;66(4):421–9. doi: 10.1002/pros.20372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO. International classification of diseases for oncology. 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Purdie CA, Piris J. Histopathological grade, mucinous differentiation and DNA ploidy in relation to prognosis in colorectal carcinoma. Histopathology. 2000;36(2):121–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Compton CC, Fielding LP, Burgart LJ, Conley B, Cooper HS, Hamilton SR, et al. Prognostic factors in colorectal cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124(7):979–94. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-0979-PFICC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Green FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz AG, Balch CM, Haller DG, et al. Cancer Staging Handbook from the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2006. American Joint Committee on Cancer. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobs TW, Prioleau JE, Stillman IE, Schnitt SJ. Loss of tumor marker-immunostaining intensity on stored paraffin slides of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88(15):1054–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.15.1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manne U, Myers RB, Moron C, Poczatek RB, Dillard S, Weiss H, et al. Prognostic significance of Bcl-2 expression and p53 nuclear accumulation in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;74(3):346–58. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19970620)74:3<346::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanmugam C, Katkoori VR, Jhala NC, Grizzle WE, Siegal GP, Manne U. p53 Nuclear accumulation and Bcl-2 expression in contiguous adenomatous components of colorectal adenocarcinomas predict aggressive tumor behavior. J Histochem Cytochem. 2008;56(3):305–12. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7362.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moniaux N, Varshney GC, Chauhan SC, Copin MC, Jain M, Wittel UA, et al. Generation and characterization of anti-MUC4 monoclonal antibodies reactive with normal and cancer cells in humans. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52(2):253–61. doi: 10.1177/002215540405200213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allison P. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan EMP. J AM Stat Assoc. 1958. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations; p. 53. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J Roy Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Winterford CM, Walsh MD, Leggett BA, Jass JR. Ultrastructural localization of epithelial mucin core proteins in colorectal tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1999;47(8):1063–74. doi: 10.1177/002215549904700811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogata S, Uehara H, Chen A, Itzkowitz SH. Mucin gene expression in colonic tissues and cell lines. Cancer Res. 1992;52(21):5971–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jhala N, Jhala D, Vickers SM, Eltoum I, Batra SK, Manne U, et al. Biomarkers in Diagnosis of pancreatic carcinoma in fine-needle aspirates. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;126(4):572–9. doi: 10.1309/cev30be088cbdqd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vincent A, Ducourouble MP, Van Seuningen I. Epigenetic regulation of the human mucin gene MUC4 in epithelial cancer cell lines involves both DNA methylation and histone modifications mediated by DNA methyltransferases and histone deacetylases. Faseb J. 2008;22(8):3035–45. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-103390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamada N, Nishida Y, Tsutsumida H, Goto M, Higashi M, Nomoto M, et al. Promoter CpG methylation in cancer cells contributes to the regulation of MUC4. Br J Cancer. 2009;100(2):344–51. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Llinares K, Escande F, Aubert S, Buisine MP, de Bolos C, Batra SK, et al. Diagnostic value of MUC4 immunostaining in distinguishing epithelial mesothelioma and lung adenocarcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2004;17(2):150–7. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Balague C, Gambus G, Carrato C, Porchet N, Aubert JP, Kim YS, et al. Altered expression of MUC2, MUC4, and MUC5 mucin genes in pancreas tissues and cancer cell lines. Gastroenterology. 1994;106(4):1054–61. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90767-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Balague C, Audie JP, Porchet N, Real FX. In situ hybridization shows distinct patterns of mucin gene expression in normal, benign, and malignant pancreas tissues. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(3):953–64. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yeh CN, Pang ST, Wu RC, Chen TW, Jan YY, Chen MF. Prognostic value of MUC4 for mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after hepatectomy. Oncol Rep. 2009;21(1):49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weed DT, Gomez-Fernandez C, Yasin M, Hamilton-Nelson K, Rodriguez M, Zhang J, et al. MUC4 and ErbB2 expression in squamous cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract: correlation with clinical outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(8 Pt 2 Suppl 101):1–32. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200408001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saitou M, Goto M, Horinouchi M, Tamada S, Nagata K, Hamada T, et al. MUC4 expression is a novel prognostic factor in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of the pancreas. J Clin Pathol. 2005;58(8):845–52. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2004.023572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Aranha MM, Borralho PM, Ravasco P, Moreira da Silva IB, Correia L, Fernandes A, et al. NF-kappaB and apoptosis in colorectal tumourigenesis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2007;37(5):416–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2007.01801.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Compton CC. Pathology report in colon cancer: what is prognostically important? Dig Dis. 1999;17(2):67–79. doi: 10.1159/000016908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alexander D, Jhala N, Chatla C, Steinhauer J, Funkhouser E, Coffey CS, et al. High-grade tumor differentiation is an indicator of poor prognosis in African Americans with colonic adenocarcinomas. Cancer. 2005;103(10):2163–70. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]