Sirs,

Sudden cardiac arrest is a leading cause of death in developed nations and about 40% of victims present with ventricular fibrillation at the time of first heart rhythm analysis [4]. Acute myocardial ischemia is generally considered to be the most common factor triggering fatal arrhythmias [5]. We report a rare case of sudden cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation in a patient in whom diagnostic follow-up led to the diagnosis of a primary cardiac lymphoma (PCL).

Case report

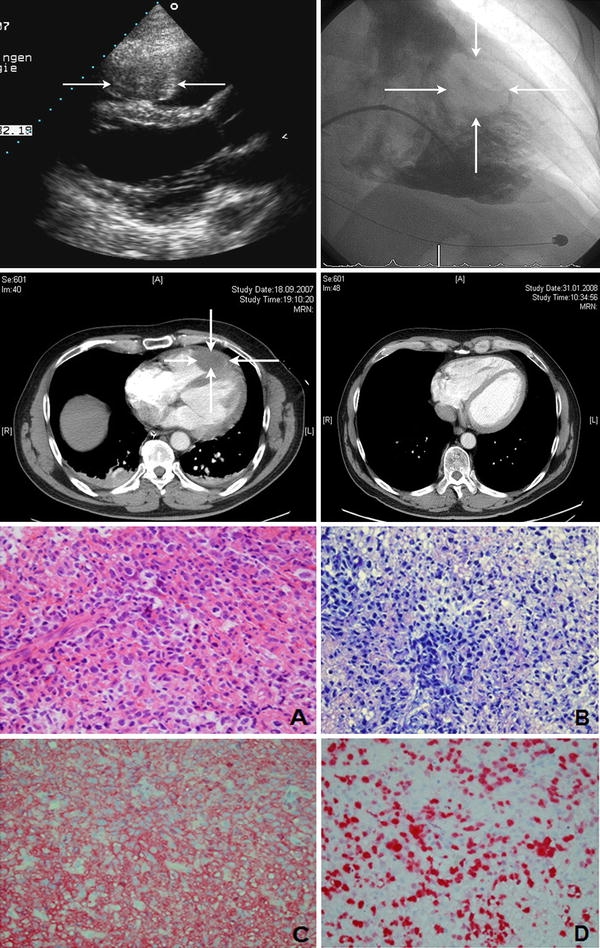

A 56-year-old Caucasian man was resuscitated at home for 25 min for ventricular fibrillation. Following the admission to our intensive care unit, he was sedated, intubated and mechanically ventilated. The initial laboratory measurement revealed a slightly diminished potassium (3.0 mmol/l), a positive troponin T value, but normal values for sodium, magnesium, renal function and creatinine kinase. The echocardiogram showed normal left and right ventricular function and no valvular heart disease. However, an approximately 4 × 3 cm mass was detected in the apex of the right ventricle which was confirmed by contrast-enhanced chest tomography (Fig. 1). Owing to slightly increasing values of cardiac enzymes, hemodynamic instability and T-wave inversion in the ECG, the patient was investigated by coronary angiography leading to the diagnosis of one-vessel coronary artery disease without the need of intervention. Angiography of the right ventricle showed an intraventricular filling defect following the injection of contrast medium (Fig. 1). Two biopsies were taken from the RV mass and the final diagnosis was diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with extranodal manifestation at the right ventricular apex, stadium I EB, international prognostic index of 1. The subsequent clinical course was uncomplicated and the patient was treated with six cycles of an anti-CD20/anthracycline-based polychemotherapy (rituxan, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone every 14 days) without radiation. After completing the last course of chemotherapy, echocardiography and CT could demonstrate a significant tumor size regression (Fig. 1). After 14 months of completing chemotherapy, a residual structure in the right ventricle of approximately 9 × 11 mm was found to be stable by echocardiography and except for chemotherapy-related low-grade peripheral polyneuropathia, the patient is otherwise in good clinical shape and free of symptoms.

Fig. 1.

Upper left panel: transthoracic echocardiogram shows an echodense structure in the right ventricle (arrows). Upper rightpanel: right ventricular angiography demonstrating an intraventricular filling defect after injection of contrast medium. Middle panel: contrast-enhanced computed tomography demonstrating an intraventricular filling defect after the injection of contrast material at the time of diagnosis (left) and after completing the last course of chemotherapy (right). Lower panel: histologic examination of the cardiac tumor biopsy showed sheets of large lymphoid cell admixed with small reactive lymphocytes [hematoxylin and eosin (a) and Giemsa (b) stains; ×400 magnification]. Immunohistochemistry demonstrated CD20 expression (c) on neoplastic cells. The proliferation rate was up to 80% (d ×400 magnification)

Discussion

Primary cardiac tumors are extremely rare and only a quarter of all cardiac tumors are malignant; 95% of these are sarcomas, 5% are lymphomas [10]. PCLs are defined as non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of different histology only involving the heart or the pericardium and usually arise in the right chambers of the heart [3]. The majority of patients presents with symptoms of right heart failure [6]. Arrhythmias are mostly described as atrial flatter or fibrillation, but lymphoma infiltration can also cause conduction disturbances. However, ventricular fibrillation is rarely described in the literature. Only one case of sudden death leading to the post mortem diagnosis of PCL and one case of ventricular tachycardia are documented in a review of 35 patients between 1960 and 2000 [2]. In our patient, the PCL was localized in the right ventricle. Infiltration of the myocardium and/or conduction system most likely induced ventricular fibrillation. Echocardiography represents a very sensitive non-invasive technique for the identification of intracardial tumors, in particular as a first diagnostic approach [8, 9]. Up to 60% of PCLs are found by transthoracic echocardiography and 97–100% by the transesophageal approach [3]. Most PCLs are of B cell lineage and about two-third is diagnosed as DLBCLs [2, 6]. A large study-based evaluation for the optimal therapeutic option is lacking due to the rarity and heterogeneous histology of PCLs. Ceresoli suggested that PCLs should be treated like bulky aggressive lymphomas arising in other primary sites [1]. In a review of 40 cases from 1995 to 2002, chemotherapy alone was applied in 57.5% and in combination with radiation in 12.5% of patients [6]. Antracycline-based chemotherapy resulted in 61% of complete remission (mean follow-up 17 months), whereas surgery did not seem to improve survival at all [1]. Despite the treatment, approximately 60% of patients died within 2–4 months after diagnosis [2, 6]. Of note, to date the standard treatment of any DLBCL is an anti-CD20/antracycline-based chemotherapy. Generally, survived cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation is a class I indication with evidence level A for an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) [7]. However, PCLs per se are associated with a high-mortality rate within the first months after diagnosis. On the other hand, complete remission should abolish the arrhythmogenic substrate. In case of lymphoma recurrence, prognosis would be very limited. Therefore, we decided against the implantation of an ICD, even if another episode of ventricular fibrillation may occur.

In conclusion, PCL can be the cause of sudden cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. In our patient, an anti-CD20/antracycline-based chemotherapy led to complete remission (unconfirmed, CRu), and no relapse 14 months after the initial diagnosis. This case supports that PCL should be treated like bulky aggressive lymphomas arising in other primary sites.

References

- 1.Ceresoli GL, Ferreri AJ, Bucci E, Ripa C, Ponzoni M, Villa E. Primary cardiac lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: diagnostic and therapeutic management. Cancer. 1997;80:1497–1506. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19971015)80:8<1497::AID-CNCR18>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chalabreysse L, Berger F, Loire R, Davouassoux G, Cordier JF, Thivolet-Bejui F. Primary cardiac lymphoma in immunocompetent patients: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2002;441:456–461. doi: 10.1007/s00428-002-0711-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faganello G, Belham M, Thaman R, Blundell J, Eller T, Wilde P. A case of primary cardiac lymphoma: analysis of the role of echocardiography in early diagnosis. Echocardiography. 2007;24:889–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2007.00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Handley AJ, Koster R, Monsieurs K, Perkins GD, Davies S, Bossaert L. European Resuscitation Council guidelines for resuscitation 2005. Section 2. Adult basic life support and use of automated external defibrillators. Resuscitation. 2005;67(Suppl 1):S7–S23. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huikuri HV, Castellanos A, Myerburg RJ. Sudden death due to cardiac arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1473–1482. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra000650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ikeda H, Nakamura S, Nishimaki H, Masuda K, Takeo T, Kasai K, Ohashi T, Sakamoto N, Wakida Y, Itoh G. Primary lymphoma of the heart: case report and literature review. Pathol Int. 2004;54:187–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2003.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung W, Andresen D, Block M, Böcker D, Hohnloser SH, Kuck K-H, Sperzel J. Leitlinien zur Implantation von Defibrillatoren. Clin Res Cardiol. 2006;95:696–708. doi: 10.1007/s00392-006-0475-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kober G, Magedanz A, Mohrs O, Nowak B, Scherer D, Bug R, Voigtländer T. Non-invasive diagnosis of a pedunculated left ventricular hemangioma: tumor classification and evaluation of relevant literature. Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96:227–231. doi: 10.1007/s00392-007-0493-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schwab J, Haack G, Sinss D, Bär I, Zahn R. Diagnosis of left ventricular myxoma with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Res Cardiol. 2007;96:189–190. doi: 10.1007/s00392-007-0489-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro LM. Cardiac tumours: diagnosis and management. Heart. 2001;85:218–222. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.2.218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]