Abstract

Objectives

To examine the independent and joint effects of psychosocial chronic and acute stressors with weight status and to report the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for BMI.

Methods

Baseline data on 2782 employees from a group-randomized weight gain prevention intervention were examined to investigate the effect of high job strain and job insecurity on body mass index (BMI) and on the odds of overweight/obesity including potential confounders and mediating variables. Data were analyzed using mixed models.

Results

The mediating variables removed the effect of high job strain on weight (β = 0.68, p = 0.07; OR = 1.34, CI = 1.00, 1.80) while job insecurity was never significant. ICC for BMI is 0.0195, 0.0193 and 0.0346 overall, for men and women, respectively.

Conclusion

Worksite wellness should target health enhancing behaviors to minimize the health effects of psychosocial work conditions.

Introduction

Substantial research now exists relating to the psychosocial characteristics of the work environment, as opposed to the physical or chemical work environment, with health outcomes. Pressures and demands at work have been associated with cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality,1-7 the metabolic syndrome and its components, 8 obesity,9 stroke exhaustion,10 depression and anxiety,11 and self-reported poor health.12 In addition, there is some evidence that these conditions have negative effects on leisure time physical activity,13-14 eating habits,13,15 and the co-occurrence of adverse health behaviors.16 It has been hypothesized that psychosocial working conditions can affect health either directly by its effect on the immune system, biological, and hormonal pathways or indirectly by influencing behaviors that are in the intermediate causal pathway between the psychosocial work environment and health outcomes.9,17

The job demand-control model11,18-19 describes the psychosocial work environment and is perhaps the model that has been used more frequently to examine the effects of working conditions on health across different work settings and countries. The demand-control model was developed for work environments where “stressors” are chronic and are the product of human organizational decision making. Additionally, the model proposes that the psychosocial job experience promotes new patterns of behaviors and skills over a lifecourse of work experience that have ultimately had an impact on a variety of conditions of adult life.

Although there is extensive literature on worksite chronic stressors and health, not much is known about the health effects of acute stressors in the workplace. Although downsizing has become a common feature in American workplaces, little has been said on how downsizing affects remaining employees’ work-experience and the health of downsizing survivors (employees who have retained their jobs while their companies implemented major lay-offs). It has been observed that downsizing survivors are at higher risk of sickness absence, CVD mortality,20 and self reported morbidity.21 To our knowledge, there is only one article examining the effect of job insecurity on 5-year change in BMI.22

In this paper, we analyze baseline data from a worksite randomized control trial for weight gain prevention, “Images of a Healthy Worksite”. This study tested interventions attempting to create synergy between the worksite environment and workers’ food and physical activity choices. The study is being conducted in a manufacturing facility with multiple sites in upstate New York. At the time the study started, the company was undergoing a drastic re-structuring with massive layoffs and building closings. Employees interviewed during the formative research period prior to baseline assessments expressed on-going layoffs that left those remaining “doing the work of 5 people,” stress eating,23 and feeling like ‘vegging out’ instead of engaging in leisure time physical activity (unpublished data). Thus, at the time of baseline assessment, in addition to chronic stressors, the employees were under the effect of acute stressors as well. Given that the primary outcome of the trial is the prevention of weight gain in the population of employees, we consider it necessary to explore whether working conditions, long standing as well as new ones, may influence the main outcome and might have to be considered in the evaluation of the intervention effect as potential confounders or effect modifiers.

The goal of this paper is to present the baseline characteristics of the sample of employees and to examine the baseline association between chronic and acute stressors and employee weight status. In addition, we report on the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for body mass index (BMI) overall and by gender in our worksites to aid other investigators in determining the adequate sample size for group-randomized trials among worksites with characteristics similar to ours. Specifically, our hypotheses are: 1) high job strain, as chronic work stressors based on the demand-control model, and job insecurity, as acute work stressor, are independently and synergistically associated with employee weight status; and 2) the association of high job strain and job insecurity with weight status are at least partly mediated by the measures of physical activity, sedentary behavior, and diet quality.

Methods

Study Sample

The Images of a Healthy Worksite study is a group-randomized control trial that assigned 6 pairs of worksites within a single corporation in upstate New York to a nutritional and physical activity intervention and to delayed intervention. The 2-year intervention consisted in a comprehensive nutrition and physical activity strategy based on participatory research involving the worksite environment (e.g., reduced caloric density in cafeteria meals, half portion offerings, walking routes) and the individual employees (e.g., nutrition education workshops, stress reduction strategies). Employee advisory boards in each intervention worksite provided input in intervention design. Worksites were matched by type of job (white or blue collar) and presence or absence of a cafeteria in the building. We collected baseline data in a cross-sectional sample of employees and we are currently collecting post-intervention data on another cross-sectional sample of employees. Since the study lost a pair of worksites due to building closings, we are reporting the analysis of baseline data from the 5 remaining pairs plus an additional worksite that closed after the collection of baseline measurements (11 worksites). More details of the study have been published elsewhere.24 All employees in the 11 worksites were eligible to participate in assessments. We collected baseline measurements in 2,782 (71% of our targeted enrollment). Employees were recruited for baseline assessments through e-mails, flyers, and presentations at team meetings. Following informed consent, project staff took anthropometric measures, and distributed a survey with a self-addressed envelope for employees to complete on their own time.

Conceptual Framework

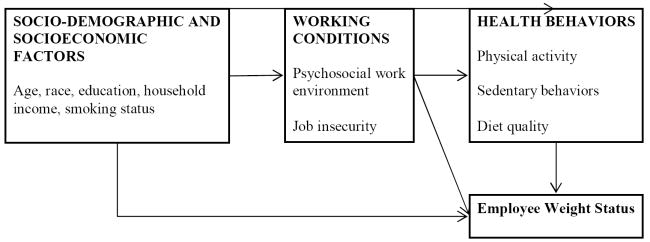

Figure 1 represents our hypothesized causal pathway between working conditions and weight status. According to this pathway, both acute and chronic stressors are related to weight status either directly or indirectly through health behaviors. Directly, adverse psychosocial factors in the workplace may act on employee weight status through the effects of ‘stress’ and its effects on the neuroendocrine system resulting in weight gain and abdominal fat accumulation.17,25 For example, stress may cause an increase in adrenal corticoid and therefore accumulation of abdominal fat as is seen in patients with Cushing’s syndrome.25 Also, stress may decrease sex hormones leading to weight gain and abdominal obesity as it is observed among menopausal women.25 Indirectly, adverse working conditions may affect weight status through unhealthy eating behaviors such as the consumption of fatty and sweet foods or not engaging in leisure time physical activity due to long work hours.26-27

Figure 1.

Hypothesized conceptual framework of the causal pathways linking working conditions with employee weight status.

Adapted from Lallukka, T. Doctoral Dissertation. 2008.45

Outcome Measures

We examined two outcome measures related to weight status: Body mass index (BMI) and proportion of overweight/obese employees. Body weight was measured using Tanita BWB 800S scale without shoes and wearing light clothing and height was measured without shoes using Shorr Infant/Child/Adult Height/ Length Measuring Board stadiometer. Body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2) was then calculated. Overweight/obesity was defined as BMI greater than 24.9 and healthy weight/underweight was defined as a BMI equal or less than 24.9.28

Main Predictors

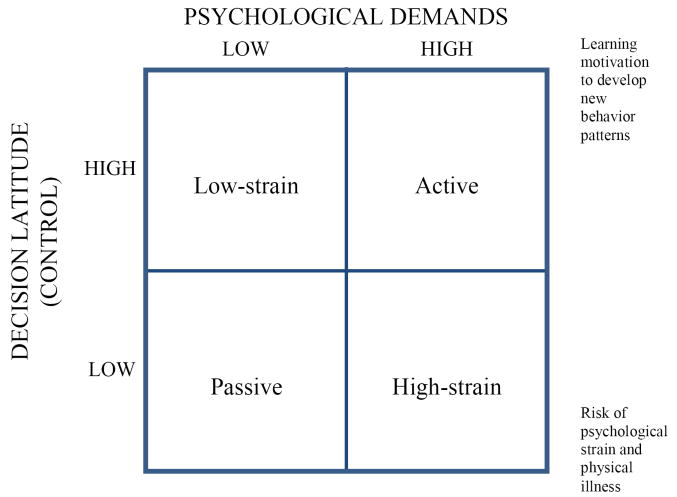

Assessment of chronic and acute stressors at work was based on a modified Job Content Questionnaire.29 Chronic work stressors were defined following the demand-control model. The Demand/Control model,11,18-19 describes two dimensions of the psychosocial work environment: the psychological demands of work and decision latitude, which is a combined measure of task control and skill use. The psychological demand dimension relates to pressures and heavy demands (‘how hard one works’); the decision latitude dimension refers to the worker’s ability to control his or her own activities and skill usage (who makes the decisions? who does what?’). The decision latitude scale has two components: task authority – employee’s control over decision making relevant to his/her work tasks and skill discretion – employee’s control over the use and development of his/her skills. When the psychological demand and the decision latitude dimensions are cross-tabulated, four quadrants of the psychosocial work environment are defined (figure 2). The high demand-low decision latitude quadrant, high job strain, is considered the most related to illness. The combination of high psychological demands and high decision latitude is defined as the active quadrant in which employees can cope with high demands because they can make more relevant decisions (this situation corresponds to psychological growth). The low-demand-high decision latitude quadrant, low job strain, is the ideal condition while the low-demand-low decision latitude quadrant, passive, seems to be associated with risk of loss of skills and psychological atrophy.19 Decision latitude was assessed by eight questions and psychological demands were assessed with 5 questions from the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ).29 To create ‘high’ and ‘low’ variables for the 4 quadrants of the demand-control model, the scores for the two dimensions (demands and latitude) were divided at the median point of the overall sample distribution. Cronbach’s alpha for the decision latitude scale for men and women were 0.83 and 0.80 and for the psychological demands were 0.63 and 0.62, respectively.29

Figure 2.

Psychological demand – decision latitude model. Source: Karasek

Acute work stressors were operationalized by the three-question job insecurity scale from the JCQ: five options for ‘how steady is your job?’ (regular and steady to both seasonal and frequent lay-offs); four options for ‘my job security is good’ (strongly disagree to strongly agree); and 4 options for ‘how likely is it that in the next couple of years you will lose your job’ (not at all likely to very likely). The score ranges from 3 to 13, the higher the score, the higher the job insecurity. Cronbach’s alpha for job insecurity was 0.53 and 0.41.29

Potential Confounders

To assess the independent association between high job strain and job insecurity with the outcomes we included the following potential confounders: age in years, gender, race (White, African American, Other), income (≤ $29,999, $30,000-$59,999, ≥ $60,000), education (secondary or less, undergraduate, graduate), and smoking status (never smoked, current, ex-smoker).

Potential Intermediate Variables

Three potential intermediate variables of the association between chronic and acute stressors and weight status were included in the model (figure 1): physical activity, sedentary behavior, and diet quality. Physical activity was operationalized using the Godin questionnaire that provides a total leisure time physical activity score.30 The questionnaire assesses how many times, on average, an employee has performed strenuous, moderate, and mild physical activity for more than 10 minutes during free time. The Pearson correlation between the questionnaire and objectives measures of physical condition was 0.24 (p<0.001). Two-week test-retest reliability coefficients were respectively 0.84, 0.46, and 0.48 for strenuous, moderate, and light leisure time physical activity.30 We combined strenuous, moderate, and light leisure time physical activity to obtain a total Godin score. Sedentary behavior was operationalized as the number of hours a day the employees spend watching TV (TV viewing: < 2 hrs/day, 2-3 hrs/day, ≥4 hrs/day). It has been proposed that TV viewing contributes to weight gain by providing passive entertainment through television and, therefore, making physical activity less attractive.31 Hours watching TV has been found to be negatively associated with cardiorespiratory fitness and moderate-intensity and hard-intensity physical activity and positively associated with light-intensity physical activity and BMI among adults.32 Diet quality was operationalized as the number of servings of fruits and vegetables per day using a 7-question food frequency questionnaire (FFQ). This FFQ asks about the frequency and types of fruits and vegetables consumed in the past month – fruit juices, fruits, salad, fried and not fried potatoes, and other vegetables. French fries are excluded from the calculation of the number of servings of fruit and vegetables. This short FFQ is an abbreviated version of a larger FFQ instrument.33 It was assumed that the more servings of fruits and vegetables the better quality of the overall diet. There is evidence that healthy eating (as defined by various scoring methods) helps maintain a healthy weight34 since, for example, a liberal intake of fruits and vegetables as well as whole-grain breads and cereals are markers for nutrient-dense diets providing adequate levels of dietary fiber.35

Statistical Analysis

We described the baseline characteristics by intervention and control status and the statistical comparisons of means and proportions. To test the hypotheses, we modeled the relationship of BMI with the quadrants of psychosocial work environment, job insecurity and other covariates by treating BMI as a continuous variable and as a two level categorical variable separately. When fitting models with BMI as a continuous variable, we used the linear mixed-effects models by considering the worksites as a random effect. When fitting models with BMI as a two-level categorical variable, we used the generalized linear mixed-effects models (GLIMMIX procedure in SAS) with a logit link function.

We first modeled the relationship between BMI and psychosocial work environment, job insecurity and other covariates by treating BMI as a continuous variable. Psychosocial work environment was modeled as a 3-level variable (high job strain, low job strain, active, and passive as the reference category). We fit a mixed-effects model for the data with the worksites as the random effects. We modeled the relationship of BMI with quadrant of the demand-control model and job insecurity separately in model 1A and model 1B, respectively, and then we fitted them together jointly in model 2. We added other potential confounders such as age, gender, race, income, smoking, and education with quadrants of the demand-control model and job insecurity in model 3. In the last model, we removed the insignificant terms from model 3 and added three potential intermediate covariates in model 4. We also tested for interactions between the quadrants of the demand-control model and job insecurity.

To further examine the effect of psychosocial work condition and job insecurity on employees’ weight status, we also considered the model where BMI is a two-level categorical variable (obese/overweight versus healthy weight/underweight). We then modeled the logit of falling into the obese/overweight group given the quadrants of the demand-control model, job insecurity, and other potential confounder and intermediate variables. We followed the same model building procedure as in the continuous outcome case. We fitted a generalized linear mixed-effects model with a logit link function to the data with the worksites as the random effects. This model estimates odds ratios (OR) with the associated confidence intervals. We modeled the relationship of BMI with quadrant and job insecurity separately in model 1A and model 1B and then jointly in model 2. We added the same potential confounders with the quadrants of the demand-control model and job insecurity in model 3. In the last model, we removed the insignificant terms from model 3 and added the three potential intermediate variables in model 4.

The ICC is the fraction of the total variation in the data that is attributable to the unit of assignment. In this case, we are reporting the fraction of the total variation in BMI that is attributable to the clustering of employees in the same worksite in comparison with employees of different worksites. The ICC overall was computed using the linear mixed-effects model with the worksites as the random effects. ICC by gender was computed similarly within the same gender group. All the models were fitted using SAS 9.1 windows version (Cary, NC). The study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board.

Results

Descriptive Statistics (table 1)

Table 1.

Images of a Healthy Worksite. Baseline Descriptive Statistics (N=11; n=2782)

| Variable | Intervention Mean(SE) | Control Mean(SE) | Significance p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits & Vegetables (servings/day) | 3.38 (0.12) | 3.48 (0.11) | 0.54 |

| Age (years) | 47.61 (0.14) | 47.40 (0.36) | 0.59 |

| BMI | 28.93 (0.30) | 28.87 (0.36) | 0.89 |

| Job Insecurity | 7.27 (0.05) | 7.37 (0.06) | 0.18 |

| Length of Employment (years) | 21.93 (1.09) | 21.98 (0.66) | 0.97 |

| Godin Score | 35.62 (0.71) | 33.70 (0.82) | 0.08 |

| Number (%) | Number (%) | p-value** | |

| Psychosocial Work Environment | 0.003 | ||

| High Job Strain | 255 (19.9) | 201 (23.0) | |

| Low Job Strain | 410 (32.0) | 315 (36.0) | |

| Active | 271 (21.2) | 180 (20.6) | |

| Passive | 345 (26.9) | 179 (20.5) | |

| Healthy Weight Status | 0.17 | ||

| Overweight | 623(41.51) | 477(37.35) | |

| Obese | 511(34.04) | 457(35.79) | |

| Education | 0.026 | ||

| Secondary or less | 253(18.63) | 255(24.40) | |

| Undergraduate | 857(63.11) | 655(62.68) | |

| Graduate | 248(18.26) | 135(12.92) | |

| Income | 0.06 | ||

| ≥ $60,000 | 871 (71.9) | 609 (67.1) | |

| $30,000-$59,999 | 308 (25.4) | 272 (30.0) | |

| ≤ $29,999 | 32 (2.6) | 26 (2.9) | |

| Race | 0.30 | ||

| White | 1243 (92.55) | 925 (89.81) | |

| African American | 60 (4.47) | 58 (5.63) | |

| Other | 40 (2.98) | 47 (4.56) | |

| Smoking Status | 0.76 | ||

| Never smoked | 839 (61.83) | 657 (62.87) | |

| Current | 144 (10.61) | 110 (10.53) | |

| Ex-smoker | 374 (27.56) | 278 (26.60) | |

| TV Viewing | 0.05 | ||

| < 2 hrs/day | 465 (34.3) | 280 (30.0) | |

| 2-3 hrs/day | 722 (53.3) | 545 (58.4) | |

| ≥ 4 hrs/day | 168 (12.4) | 109 (11.7) | |

| Marital Status | 0.29 | ||

| Married | 1050 (77.26) | 778 (74.95) | |

| Gender | < 0.0001 | ||

| Female | 470 (31.3) | 558 (43.7) | |

| Male | 1033 (68.7) | 720 (56.3) |

t-test of difference between means

Chi-square test of independence

The intervention and control groups are well balanced with respect to relevant characteristics with the exception of gender, the psychosocial work environment, and the educational level of the employees. This is a sample of middle aged employees (mean age of approximately 47 years), mostly white (>90%), mostly male (56% and 69% for control and intervention, respectively), married (more than a quarter of the employees), highly educated (76% and 81% of control and intervention employees, respectively, have undergraduate education or more) and relatively well-paid (67% and 72% of control and intervention employees, respectively, earn more than $60,000 a year), who have been working in the company for an average of almost 22 years. The employees’ weight status is in the overweight category (mean BMI of almost 29 for both groups) and the prevalence of overweight/obesity is 72.1% and 75.6% for control and intervention groups, respectively. Most of the employees work on low strain jobs (36% of the control and 32% of the intervention groups). The job insecurity score is approximately 7 for both groups with a range of 3 to 13 (data not shown). The mean Godin score (total leisure time physical activity) for both groups is 34.7 with a range of 0 to 169 (data not shown) and more than 65% of the employees watch 2 or more hours of TV per day.

Baseline Association between Chronic and Acute Stressors and BMI (table 2)

Table 2.

Images of a Healthy Worksite. Baseline association between chronic and acute stressors with BMI (N=11; n=2782)

| Table 2 | Model 1A | Model 1B | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | β (SE) | |

| Intercept | 28.27 (0.32) | 27.86 (0.53) | 27.70 (0.56) | 25.75 (1.01) | 25.90 (1.04) |

| Psychosocial Work Environment (ref: Passive) | |||||

| High Job Strain | 0.88 (0.35)* | 0.84 (0.36)* | 0.89 (0.39)* | 0.68 (0.39) | |

| Low Job Strain | 0.38 (0.31) | 0.28 (0.32) | 0.09 (0.34) | 0.01 (0.34) | |

| Active | 0.42 (0.35) | 0.39 (0.35) | 0.39 (0.37) | 0.49 (0.37) | |

| Job Insecurity | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.08 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.06 (0.07) | |

| Age | 0.05 (0.02)* | 0.04 (0.02)* | |||

| Gender Female | - 0.78 (0.27)* | - 0.84 (0.27)* | |||

| Race (ref: White) | |||||

| African American | 1.99 (0.63)* | 1.46 (0.63)* | |||

| Other | - 2.49 (0.72)* | - 2.39 (0.71)* | |||

| Income (ref: ≥ $60,000) | |||||

| $30,000-$59,999 | 0.90 (0.30)* | 0.76 (0.30)* | |||

| ≤ $29,999 | - 0.63 (0.86) | - 1.06 (0.85) | |||

| Smoking (ref: Never) | |||||

| Current | - 0.67 (0.44) | ||||

| Ex-smoker | 0.36 (0.29) | ||||

| Education (ref: Undergraduate) | |||||

| Graduate | - 1.50 (0.36)* | - 1.27 (0.36)* | |||

| Secondary or less | 0.16 (0.34) | - 0.10 (0.33) | |||

| Godin Score | - 0.02 (0.00)* | ||||

| Fruits and Vegetables (ser/day) | - 0.02 (0.06) | ||||

| TV Viewing (hrs/day) (ref: < 2 hrs/day) | |||||

| 2-3 hrs/day | 2.37 (0.43)* | ||||

| ≥ 4 hrs/day | 1.35 (0.28)* | ||||

BMI = Body Mass Index;

p-value = < 0.05

High job strain was the only quadrant of the demand-control model independently and positively associated with BMI in the crude analysis (model 1A) while job security was not (model 1B). Employees working in a high job strain environment have almost 1 BMI unit more than those working in a passive one (β=0.88, SE=0.35). These associations hold when fitting the two predictors together in model 2 and controlling for potential confounders in model 3. In addition, age, African American race, and income between $30,000 and $59,999 are positively associated with BMI while employees of other race, and females have a lower BMI than their reference values controlling for all other variables in the model. The effect of high job strain on BMI did not hold once the potential intermediate variables were included (model 4). Of the hypothesized intermediate variables, Godin score and TV-viewing were found to be associated with the outcome in the expected direction. For each unit change in Godin score, BMI decreases by 0.02 units (β=-0.02, SE=0.00) and employees who watch between 2-3 hours and equal or more than 4 hours of TV per day have a BMI 2.37 and 1.35 units larger than employees who watch less than 2 hours a day, respectively. Number of servings of fruits and vegetables per day had no statistical significant effect on BMI (β=-0.22, SE=0.06) although the effect is in the expected direction. The interaction term between the quadrants of the demand-control model and job insecurity are not statistically significant and therefore they were dropped from the models (data not shown).

Baseline Association between Chronic and Acute Stressors and the odds of overweight/obesity (table 3)

Table 3.

Images of a Healthy Worksite. Baseline association between chronic and acute stressors with the odds of being obese/overweight1 (N=11; n=2782)

| Predictors | Model 1A | Model 1B | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Psychosocial Work Environment (ref: Passive) | |||||

| High Job Strain | 1.49 (1.13, 1.96)* | 1.44 (1.09, 1.91)* | 1.45 (1.09, 1.95)* | 1.34 (1.00, 1.80)* | |

| Low Job Strain | 1.30 (1.01, 1.67)* | 1.23 (0.95, 1.59) | 1.24 (0.95, 1.62) | 1.24 (0.95, 1.62) | |

| Active | 1.28 (0.97, 1.69) | 1.26 (0.95, 1.67) | 1.45 (1.09, 1.94)* | 1.50 (1.12, 2.03)* | |

| Job Insecurity | 1.06 (1.01,1.12)* | 1.04 (0.99, 1.10) | 1.03 (0.98, 1.09) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | |

| Age | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03)* | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03)* | |||

| Gender (ref: Male) | |||||

| Female | 0.87 (0.71, 1.06) | ||||

| Race (ref: White) | |||||

| African American | 1.99 (1.33, 2.99)* | 1.69 (1.11, 2.58)* | |||

| Other | 0.36 (0.14, 0.95)* | 0.32 (0.12, 0.90)* | |||

| Smoking (ref: Never) | |||||

| Current Smoker | 0.75 (0.54, 1.05) | ||||

| Ex-smoker | 1.09 (0.88, 1.35) | ||||

| Education (ref: Undergraduate) | |||||

| Graduate | 0.48 (0.34, 0.68)* | 0.51 (0.35, 0.73)* | |||

| Secondary or less | 1.20 (0.95, 1.51) | 1.02 (0.81, 1.29) | |||

| Godin Score | 0.99 (0.97, 0.99)* | ||||

| Fruits/Vegetables Score | 1.00 (0.95, 1.05) | ||||

| TV Viewing (ref: < 2 hrs/day) | |||||

| 2-3 hrs/day | 1.77 (1.40, 2.24) | ||||

| ≥ 4 hrs/day | 2.50 (1.82, 3.45) | ||||

Obese/overweight: Body Mass Index > 24.9

P-value < 0.05

High and low job strain (OR=1.49, CI=1.13,196; OR=1.30, CI=1.01,16.7, respectively) and job insecurity (OR=1.06, CI=1.01,1.12) increased the odds of being overweight/obese in the crude analysis (models 1A and1B). The effect of job insecurity and low job strain did not hold in any of the subsequent models. High job strain, however, remained independently and positively associated with overweight/obesity in model 2 (OR=1.44,CI=1.09,1.91) and its effect did not appear to be confounded by the variables in model 3 (OR=1.45, CI=1.09,1.95). In the latter model, the active quadrant of the demand-control model became a significant predictor of the odds of overweight/obesity (OR=1.45, CI=1.09,1.94) compared to the passive quadrant. Age and African American race significantly increased while Other race and graduate education significantly decreased the odds of overweight/obesity in this sample. The inclusion of the hypothesized intermediate variables in model 4 removed the effect of high job strain while holding the effect of the active quadrant (OR=1.50, CI=1.12,2.03). In this model, Godin score decreased (OR=0.99, CI=0.97,0.99) and TV-viewing increased the odds of overweigh/obesity. Employees who report watching 2-3 hours a day of TV increased their odds of being overweight/obese by 77% while watching more than 4 hours a day increased the odds by 150% compared to those who watch less than 2 hours. Servings of fruit and vegetables per day was not associated with the outcome. Also, in these models, there was not interaction between the quadrants of the demand-control model and job insecurity (data not shown).

ICC for BMI

In our sample, the ICC for BMI overall is 0.0195. Once stratified by gender, the ICC for BMI for males is 0.0193, ICC for BMI for females is 0.0346.

Discussion

This cross-sectional study based on the baseline assessment of employees participating in a group-randomized trial for weight gain prevention suggests that high job strain, as a construct for chronic stressors in the work environment, and not job insecurity, as an acute stressor, is associated with weight status. Furthermore, there is no synergistic effect of chronic and acute stressors on the outcome. In this sample of employees it appears that high job strain has an effect on weight status through the adoption of unhealthy behaviors such as not engaging in leisure time physical activity and practicing sedentary behaviors (e.g., watching TV) since the effect of job strain all but disappears once the behavioral variables are added to the models. Diet quality, as operationalized by the intake of fruit and vegetables, does not seem to mediate the effect of a high job strain environment on weight status. These results are fairly consistent regardless of the way weight status was modeled. Unexpectedly, employees in an active work environment are more likely to be overweight or obese and its effect does not seem to be mediated by any of the postulated intermediate variables.

A fair comparison of the results of the current study with previous literature is difficult since there are differences in the way the psychosocial work environment is defined, the confounders included in the analyses, and the measurement of weight status (BMI, overweight, weight gain). In a recent review9 of 18 investigations examining the components of the demand-control model and body weight published between 1989 and 2006, 15 examined the effect of high job strain, of which 12 studies were cross-sectional and 3 were prospective. According to this review, the evidence is inconsistent since in 3 of the studies the association between high job strain and a measure of body weight was fully confirmed, in one was partially confirmed, and in 10 there was no association. In a subsequent comparative study of pooled cross sectional data from three worksite cohorts in Britain, Finland, and Japan, the high strain, passive, and active quadrants of the demand-control model were not associated with obesity36 when compared with the low strain quadrant neither in the unadjusted nor in the fully adjusted models. On the contrary, in the prospective Whitehall II study,37 repeated measures of work stress over a period of 19 years showed a dose response relationship with incident overall obesity (BMI >=30kg/m2) and central obesity once adjusted for a variety of health behaviors (alcohol consumption, smoking, daily intake of fruit and vegetables, fiber consumption, exercise). Work stress, however, is defined as high job strain and lack of work social support and, thus, it is not fully comparable to the effect of job strain alone as examined in the study presented here. The inconsistency of the relationship between job strain and body weight might be explained by the findings of two prospective studies included in the previous review.9 These two studies among British civil servants38 and Danish men22 indicated that the longitudinal effects of job strain on weight differ according to initial BMI. Whereas high job strain predicted weight gain among overweight or obese employees at baseline, high job strain predicted weight loss among the leanest ones. Other potential explanations for the conflicting results is that different population of workers may have diverging coping strategies allowing them to handle high job strain in different ways. For example, age, social support in and outside the workplace, work-home interface,39 and the existence of a social safety net may influence the way workers respond to a stressful work environment. In addition, different individual responses to ‘stress’ through eating and physical activity have been reported in the literature26,40-41 and may explain the lack of consistency across populations and study designs.

Our study adds more evidence of a lack of cross-sectional association between high job strain and body weight. Although the magnitude of the association was relatively strong after adjusting for confounders, measures of leisure time physical activity and sedentary behavior remove the effect of job strain on weight status. High job strain was associated with low leisure time physical activity among men in London and women in Helsinki14,36 but was not related to measures of exercise among workers in Minnesota.42 To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies of the effect of high job strain on TV viewing as a measure of sedentary behavior. There is, however, evidence of an association of hours of TV viewing with weight gain31 and overweight and obesity35 among adults. Thus, further investigations of sedentary behaviors as measured by TV-viewing and high job strain are needed to confirm the mediating role of the latter behavior with weight status.

We hypothesized that physical activity, sedentary behaviors, and the number of servings of fruit and vegetables per day as a proxy for diet quality would be one of the mechanisms for which high job strain would have an effect on measures of body weight. The hypotheses were partially confirmed since our measures of physical activity and sedentary behaviors were associated with weight status in our sample and modify the magnitude of the association between job strain and weight status. In contrast, this study did not confirm our hypothesis regarding diet quality. It is possible that the fruit and vegetable FFQ used was not an appropriate measure of diet quality since it does not include other components of a healthy diet such as whole grain breads and cereals and the quality of the fat intake (saturated versus unsaturated fat). Although several studies have found no relationship between high job strain and diet quality measured as the consumption of fruit and vegetables,23,43-44 one Japanese cross-sectional study found that high job strain ratio was related to a higher intake of fat among men.15 Again, the varied tools used to measure diet quality preclude an accurate comparison of the findings. Interestingly, Jeffery and French31 found that energy intake and percentage of energy from fat were also positively associated with TV viewing. It does raise the possibility that in our study, TV viewing might have inadvertently served as a proxy for caloric intake and diet quality and may have counteracted the effect of our proxy for diet quality. Finally, it is important to note that characteristics of the psychosocial work environment have been hypothesized to have a direct effect on health outcomes including overweight and obesity independently of their effect on individual behavior.9

An unexpected finding was that active work environment was associated with overweight or obesity. Among Minnesota workers, active job environment was not associated with BMI.42 Since the effect of an active job environment was only observed in the adjusted analysis and was not mediated by other variables, we suspected that the relationship might be confounded by age since employees in an active work situation have more resources to cope with high psychological demands and the latter may be related to seniority. However, in our data there is no difference in mean age between workers in high job strain situations and all other quadrants included active environments (data not shown). In synthesis, further investigations of the characteristics of employees who work in active job environments in our sample will help understand this association.

Given that at the time of baseline assessments in the current study, the company was implementing massive lay-offs, we hypothesized that job insecurity would work as an acute stressor in the workplace and would act directly or indirectly on measures of weight status.22 Also, we expected to find an interaction between acute and chronic stressors. In our sample, we were unable to confirm our hypotheses. Health effects on lay-off survivors are generally understudied.20-21 It is plausible that our measurements were done too soon to be able to capture any effects on employees’ weights.

This study has several limitations. One of which is the impossibility of providing causal inferences given the cross-sectional nature of the data. Also, we do not know how representative our sample is of our worksite population since the company lacks information for relevant comparisons. Finally, the 3 item subscale assessing job insecurity as an acute stressor does not necessarily represent current job insecurity. One item of the subscale represents job insecurity in general, another represents current job insecurity, and the third represents future job insecurity. We expected, nonetheless, that in our particular context this subscale would capture the current situation. Although employees’ concern about their job security might have existed for a long time, the situation at the moment of baseline data collection went beyond what the company had previously experienced as evidenced by the unprecedented magnitude of the layoffs and the fact that entire worksites and their operations were decommissioned. The strengths of the study are that we count with measured height and weight and self-reported instead of imputed job strain measures. These data suggest that wellness programs in the worksite should target health enhancing behaviors to minimize the health effects of psychosocial work conditions. At the same time, worksites should examine their organizational and personnel development in order to prevent stressful work environments. For example, future research should investigate mechanisms that could reduce employees’ demands or increase their control over their jobs such as supportive supervision and changes in the structure of jobs. Further studies on the effect of the psychosocial work environment on weight status should be prospective, examine the potential bidirectionality of the effect of job stress by stratifying for baseline weight status, include measures of individual psychological features and work-home interface that can moderate the effect of working conditions. More evidence is needed on the health of lay-off survivors, in particular under the current economic downturn.

Acknowledgments

Funding source: National Hearth Lung and Blood Institute

Contributor Information

Fernandez Isabel Diana, Division of Epidemiology, Department of Community and Preventive Medicine, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry, 601 Elmwood Ave., Box 644, Rochester, NY 14642, Phone: 585-275-9554, Fax: 585-461-4532, diana_fernandez@urmc.rochester.edu.

Hayan Su, Department of Mathematical Sciences, Montclair State University.

Paul C Winters, Family Medicine Research, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

Hua Liang, Department of Biostatistics and Computation Biology, University of Rochester School of Medicine and Dentistry.

References

- 1.Karasek R, Baker D, Marxer F, Ahlbom A, Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1981 Jul;71(7):694–705. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.7.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karasek RA, Theorell T, Schwartz JE, Schnall PL, Pieper CF, Michela JL. Job characteristics in relation to the prevalence of myocardial infarction in the US Health Examination Survey (HES) and the Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (HANES) Am J Public Health. 1988 Aug;78(8):910–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.8.910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theorell T, Karasek RA. Current issues relating to psychosocial job strain and cardiovascular disease research. J Occup Health Psychol. 1996 Jan;1(1):9–26. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.9. Review. Erratum in: J Occup Health Psychol 1998 Oct;3(4):369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuper H, Marmot M, Hemingway H. Systematic review of prospective cohort studies of psychosocial factors in the etiology and prognosis of coronary heart disease. Semin Vasc Med. 2002;2:267–314. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-35401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M, Siegrist J, et al. Is the effect of work stress on cardiovascular mortality confounded by socioeconomic factors in the Valmet study? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:1019–20. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.016881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kivimäki M, Ferrie JE, Brunner E, Head J, Shipley MJ, Vahtera J, Marmot MG. Justice at work and reduced risk of coronary heart disease among employees: the Whitehall II Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Oct 24;165(19):2245–51. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.19.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aboa-Eboulé C, Brisson C, Maunsell E, Mâsse B, Bourbonnais R, Vézina M, Milot A, Théroux P, Dagenais GR. Job strain and risk of acute recurrent coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2007 Oct 10;298(14):1652–60. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chandola T, Brunner E, Marmot M. Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: prospective study. BMJ. 2006;332:521–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38693.435301.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siegrist J, Rödel A. Work stress and health risk behavior. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006 Dec;32(6):473–81. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsutsumi A, Kayaba K, Kario K, Ishikawa S. Prospective study on occupational stress and risk of stroke. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(1):56–61. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karasek RA. Job demands, job decision latitude and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q. 1979;24:285–308. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sacker A, Bartley MJ, Frith D, Fitzpatrick RM, Marmot MG. The relationship between job strain and coronary heart disease: evidence from an english sample of the working male population. Psychol Med. 2001 Feb;31(2):279–90. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Payne N, Jones F, Harris PR. The impact of job strain on the predictive validity of the theory of planned behaviour: an investigation of exercise and healthy eating. Br J Health Psychol. 2005 Feb;10(Pt 1):115–31. doi: 10.1348/135910704X14636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kouvonen A, Kivimaki M, Wlovainio M, Virtanen M, Linna A, Vahtera J. Job strain and leisure-time physical activity in female and male public sector employees. Prev Med. 2005;41(2):532–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawakami N, Tsutsumi A, Haratani T, Kobayashi F, Ishizaki M, Hayashi T, Fujita O, Aizawa Y, Miyazaki S, Hiro H, Masumoto T, Hashimoto S, Araki S. Job strain, worksite support, and nutrient intake among employed Japanese men and women. J Epidemiol. 2006 Mar;16(2):79–89. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kouvonen A, Kivimäki M, Väänänen A, Heponiemi T, Elovainio M, Ala-Mursula L, Virtanen M, Pentti J, Linna A, Vahtera J. Job strain and adverse health behaviors: the Finnish Public Sector Study. J Occup Environ Med. 2007 Jan;49(1):68–74. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31802db54a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wardle J, Gibson EL. Impact of stress on diet: processes and implications. In: Stansfeld SA, Marmot M, editors. Stress and the Heart: Psychosocial Pathways to Coronary Heart Disease. London, GBR: BMJ Publishing Group; 2001. pp. 124–143. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karasek RA. The impact of the work environment on life outside the job. Doctoral Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work: stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vahtera J, Kivimaki M, Pentti J, Linna A, Virtanen M, Virtanen P, et al. Organisational downsizing, sickness absence, and mortality: 10-town prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2004 Mar 6;328(7439):555. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37972.496262.0D. Epub 2004 Feb 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferrie JE, Shipley JM, Stansfeld SA, Marmot MG. Effects of chronic job insecurity and change in jobs security and self reported Health, minor psychiatric morbidity, physiological measures, and health related behaviours in British civils servants: The Whitehall II Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2002;56(6):405–6. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.6.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hannerz H, Albertsen K, Nielsen ML, Tuchsen F, Burr H. Occupational factors and 5-year weight change among men in a Danish national cohort. Health Psychol. 2004;23(3):283–8. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.3.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Devine CM, Nelson JA, Chin N, Dozier A, Fernandez ID. Pizza is cheaper than salad”: assessing workers’ views for an environmental food intervention. Obesity. 2007;15(Suppl 1):57S–68S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pratt CA, Lemon SC, Fernandez ID, Goetzel R, Beresford SA, French SA, Stevens VJ, Vogt TM, Webber LS. Design characteristics of worksite environmental interventions for obesity prevention. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007 Sep;15(9):2171–80. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.258. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada Y, Ishizaki M, Tsuritani I. Prevention of weight gain and obesity in occupational populations: a new target of health promotion services at worksites. J Occup Health. 2002;44:373–384. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epel E, Jimenez S, Brownell K, Stroud L, Stoney C, Niaura R. Are stress eaters at risk for metabolic syndrome? Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1032:208–210. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lallukka T, Laaksonen M, Martikainen P, Sarlio-Lähteenkorva S, Lahelma E. Psychosocial working conditions and weight gain among employees. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 Aug;29(8):909–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. The Evidence Report. NIH Publication No. 98-4083. National Institutes of Health; Sep, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karasek R, Brisoon C, Kawakami N, Houtman I, Bongers P, Amick B. The Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An Instrument for International Comparative Assessments of Psychosocial Job Characteristics. Journal of Occupation Health Psychology. 1998;3(4):332–55. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Godin G, Shephard RJ. A Simple Method to Assess Exercise Behavior in the Community. Canadian Journal of Applied Sport Science. 1985;10(3):141–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jeffery RW, French SA. Epidemic obesity in the United States: are fast foods and television viewing contributing? Am J Public Health. 1998 Feb;88(2):277–80. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pettee KK, Ham SA, Macera CA, Ainsworth BE. The reliability of a survey question on television viewing and associations with health risk factors in US adults. Obesity. 2009;17(3):487–93. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Serdula M, Coates R, Byes T, Mokdad A, Jewell S, Chavez N, Mares-Perlman J, Newcomb P, Ritenbaugh C, Treiber F, Block G. Evaluation of a brief telephone questionnaire to estimated fruit and vegetable consumption in diverse study populations. Epidemiology. 1993;4:448–63. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199309000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baecke JA, Burema J, Frijters JE, Hautvast JG, Wiel-Wetzels WA. Obesity in young Dutch adults: II, daily life-style and body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1983;7:13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liebman M, Pelican S, Moore SA, Holmes B, Wardlaw MK, Melcher LM, Liddil AC, Paul LC, Dunnagan T, Haynes GW. Dietary intake, eating behavior, and physical activity-related determinants of high body mass index in rural communities in Wyoming, Montana, and Idaho. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Jun;27(6):684–92. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lallukka T, Lahelma E, Rahkonen O, Roos E, Laaksonen E, Martikainen P, Head J, Brunner E, Mosdol A, Marmot M, Sekine M, Nasermoaddeli A, Kagamimori S. Associations of job strain and working overtime with adverse health behaviors and obesity: evidence from the Whitehall II Study, Helsinki Health Study, and the Japanese Civil Servants Study. Soc Sci Med. 2008 Apr;66(8):1681–98. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunner EJ, Chandola T, Marmot MG. Prospective effect of job strain on general and central obesity in the Whitehall II Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007 Apr 1;165(7):828–37. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk058. Epub 2007 Jan 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kivimäki M, Head J, Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, Brunner E, Vahtera J, Marmot MG. Work stress, weight gain and weight loss: evidence for bidirectional effects of job strain on body mass index in the Whitehall II study. Int J Obes. 2006 Jun;30(6):982–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devine CM, Stoddard AM, Barbeau EM, Naishadham D, Sorensen G. Work-to-family spillover and fruit and vegetable consumption among construction laborers. Am J Health Promot. 2007;21(3):175–82. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-21.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stone A, Brownell KD. The stress-eating paradox: multiple daily measurements in adult males and females. Psychol Health. 1994;9:425–436. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliver G, Wardle J, Gibson EL. Stress and food choice: a laboratory study. Psychosom Med. 2000 Nov-Dec;62(6):853–65. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200011000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hellerstedt WL, Jeffery RW. The association of job strain and health behaviors on men and women. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(3):575–583. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Loon AJ, Tijhuis M, Surtees PG, Ormel J. Lifestyle risk factors for cancer: the relationship with psychosocial work environment. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29(5):785–92. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.5.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lallukka T, Sarlio-Lähteenkorva S, Roos E, Laaksonen M, Rahkonen O, Lahelma E. Working conditions and health behaviours among employed women and men: the Helsinki Health Study. Prev Med. 2004 Jan;38(1):48–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lallukka T. Associations among Working Conditions and Behavioral Risk Factors: The Helsinki Health Study with International Comparisons. Doctoral Dissertation University of Helsinki. 2008 [Google Scholar]