Abstract

Congestive heart failure (HF) is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent nitric oxide–mediated vasodilatation. The aim of this study was to examine the effects of sarco/endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+-ATPase 2a (SERCA2a) gene transfer on endothelial function in a swine HF model. Two months after the creation of mitral regurgitation to induce HF, the animals underwent intracoronary injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying SERCA2a (n = 7) or saline (n = 6). At 4 months, coronary flow (CF) was measured in the mid-portion of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery. In the failing animals, CF was decreased significantly; SERCA2a gene transfer rescued CF to levels observed in sham-group [ml/min/g, 0.47 ± 0.064 saline versus 0.89 ± 0.116, SERCA2a; P < 0.05; 1.00 ± 0. 185 sham P = NS (nonsignificant)]. In coronary arteries from HF animals, SERCA2a and endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) protein expression were decreased, but restored to normal levels by SERCA2a gene transfer. In human coronary artery endothelial cells (HCAECs), SERCA2a overexpression increased eNOS expression, phosphorylation, eNOS promoter activity, Ca2+ storage capacity, and enhanced histamine-induced calcium oscillations, eNOS activity, and cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) production. Thus, SERCA2a gene transfer increases eNOS expression and activity by modulating calcium homeostasis to improve CF. These findings suggest that SERCA2a gene transfer improves vascular reactivity in the setting of HF.

Introduction

Congestive heart failure (HF) is associated with impaired endothelium-dependent vasodilatation.1,2,3,4,5 A decrease in the bioavailability of endothelium-derived nitric oxide (NO) owing to a reduction in the expression and activity of the endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) has been identified as a primary cause of endothelial dysfunction in HF.6 eNOS is a constitutively expressed enzyme that in the presence of molecular oxygen oxidizes -arginine to -citrulline and NO. This reaction is Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent and requires phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 located within the calmodulin-binding domain.7 Activation of eNOS in endothelial cells (ECs) in response to various agonists, such as histamine, acetylcholine, or shear stress generates NO which, in turn, activates soluble guanylyl cyclase in vascular smooth muscle cells to increase cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) production and promote vasodilatation.7

In human ECs, histamine-induced Ca2+ oscillations are dependent upon transmembrane ion flux, sarcoplasmic Ca2+ release channels and sarco/endoplasmic Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA).8 At least 11 isoforms of human SERCA, encoded by three separate homologous genes have been discovered.9 In blood vessels, together with the ubiquitous isoform SERCA2b, the cardiac isoform SERCA2a has been detected in smooth muscle cells, whereas SERCA3 was described as a major isoform in ECs.10,11 In cardiomyocytes, SERCA2a plays a major role in the control of excitation/contraction coupling.12,13 One of the key abnormalities in both human and experimental models of HF is abnormal calcium handling associated with a decrease in the expression and activity of SERCA2a.12,13 A large number of studies in isolated cardiomyocytes and animal models of HF showed that restoring SERCA2a expression by gene transfer corrects the contractile abnormalities and improves energetic and electrical remodeling.12,13 Results from animal models have demonstrated clearly that cardiac SERCA2a gene transfer in the failing heart improves contractile function and the energetic state, with a concomitant reduction in anterior wall thickening and ventricular arrhythmias.14,15,16 Following a long line of investigation, two clinical trials are underway using intracoronary adeno-associated virus SERCA2a (AAV.SERCA2a) injection to restore SERCA2a expression in patients with HF.17 Sakata et al. has shown that transcoronary gene transfer of SERCA2a increases coronary blood flow in a type 2 diabetic rat model, suggesting that endothelial-dependent vasodilatation can be affected by SERCA; however, the influence of SERCA2a gene transfer on vascular endothelial function has not yet been determined.18 Recently, it has been shown that ablation of the SERCA activator S100A1 protein in EC diminished agonist-induced [Ca2+]i transients and basal acetylcholine-induced endothelial NO release, leading to impaired endothelium-dependent vascular relaxation and hypertension.19 In contrast, S100A1 overexpression in ECs increased SERCA activity, amplified agonist-induced [Ca2+]i transients and enhanced NO generation.19 Together, these observations suggest that SERCA may play a key role in the regulation of endothelial function and modulate agonist-induced NO production in ECs.

We hypothesized that intracoronary SERCA2a gene transfer, in addition to its beneficial effects on myocardial function, would improve endothelial function by increasing eNOS-derived NO production. The aim of this study was to investigate the influence of SERCA2a gene transfer on coronary blood flow and eNOS expression in a preclinical HF swine model. The effects of SERCA2a gene transfer on calcium handling and eNOS expression and activity were also explored in human coronary artery ECs (HCAEC). We found that SERCA2a gene transfer improves coronary blood flow and eNOS protein expression in a preclinical model of HF in vivo and leads to an increase in eNOS expression, phosphorylation, and activity in HCAEC.

Results

Transcoronary SERCA2a gene transfer increases coronary blood flow in a swine HF model

At study completion (4 months after creation of mitral regurgitation), no significant difference between SERCA2a (n = 7), saline (n = 6), and sham (n = 4) groups was observed for the following parameters: heart rate [beats/min; 86 ± 6 versus 88 ± 5 versus 84 ± 7; P = NS (nonsignificant)], left ventricular systolic pressure (mm Hg; 100.6 ± 6.3 versus 103.4 ± 6.1 versus 96.6 ± 10.6; P = NS), and left ventricular end diastolic pressure (mm Hg; 13.9 ± 3.2 versus 14.0 ± 0.5 versus 9.9 ± 0.9; P = NS). A significant difference was documented between the saline and the SERCA2a injected groups for left ventricular ejection fraction (%; 61.5 ± 3.0 versus 70.6 ± 1.3; P < 0.05) and for adjusted rate of rise, (dP/dt)max/P (15.5 ± 1.2 versus 20.7 ± 1.2; P < 0.01). There was, however, no observed difference between the sham and the SERCA2a groups for left ventricular ejection fraction (74.4 ± 3.5 versus 70.6 ± 1.3%; P = NS), and for (dP/dt)max/P (20.7 ± 1.6 versus 20.7 ± 1.2; P = NS) demonstrating that SERCA2a gene transfer improves systolic function in mitral regurgitation animals. These findings are consistent with a complete description of cardiac function parameters and remodeling in this model that was reported previously.20

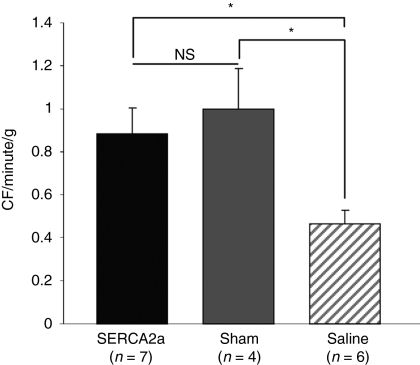

The adjusted coronary flow (CF, ml/min/g) was significantly increased in the SERCA2a group compared to the saline group (0.886 ± 0.116 versus 0.467 ± 0.064; P < 0.05), and was similar to that observed in sham-operated animals (1.0003 ± 0.185; P = NS versus SERCA group; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

SERCA2a gene transfer increases coronary blood flow in vivo in MR porcine model. Histogram showing coronary blood flow measurement in sham-operated (gray bar), MR+AAV1.SERCA2a (black bar), and MR+saline injection (hatched bars) groups. The data shown are mean ± SEM (*P < 0.05 versus saline). AAV, adeno-associated virus; MR, mitral regurgitation; NS, nonsignificant; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a.

To address the effect of AAV on vascular function, a group of sham-operated animals underwent intracoronary injection of an empty AAV (AAV null). At study completion (2 months after injection), no significant difference was documented in adjusted CF between sham (n = 4) and AAV-null group (n = 2) (1.003 ± 0.2137 versus 0.899 ± 0.042 ml/min/g; P = NS).

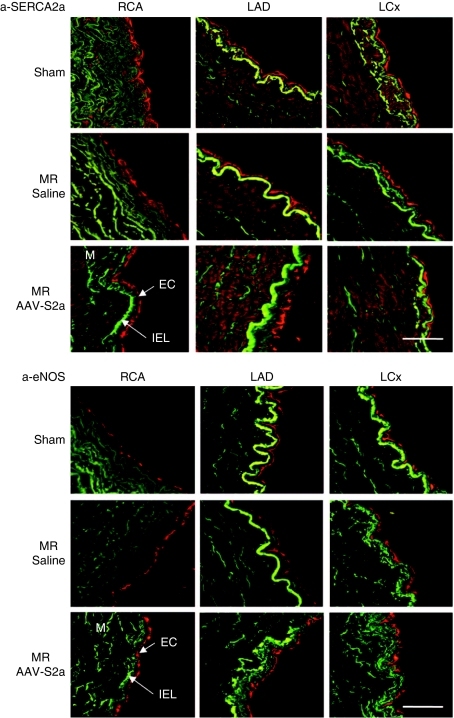

SERCA2a is expressed in coronary ECs of swine animals

Morphological analysis performed on hematoxylin/eosin stained sections of the left anterior descending (LAD), left circumflex, and right coronary arteries did not reveal any structural differences between sham, saline, or SERCA2a groups and there was no evidence of atherosclerosis in any of the samples analyzed (data not shown). Confocal microscopy immunofluorescence analysis of swine coronary artery sections demonstrated that SERCA2a is expressed in EC as well as in smooth muscle cells in all treatment groups; however, both eNOS and PECAM-1 (platelet EC adhesion molecule-1; markers of EC) were expressed only in EC in all treatment groups (Figure 2; Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2.

Confocal immunofluorescence analysis of porcine coronary arteries. Cross sections of left anterior descending (LAD), left circumflex (LCx), and right coronary arteries (RCA) obtained from sham-operated or MR animals injected either with AAV.SERCA2a or with saline were analyzed by confocal immunofluorescence (red) with specific antibody; anti-SERCA2a and anti-eNOS. The media was identified by elastin autofluorescence (green). At least three animals were analyzed for each group. Bar = 50 µm. AAV, adeno-associated virus; EC, endothelial cells; eNOS, endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase; IEL, internal elastic lamina; M, media; MR, mitral regurgitation; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a.

SERCA2a gene transfer increases eNOS expression in coronary artery ECs

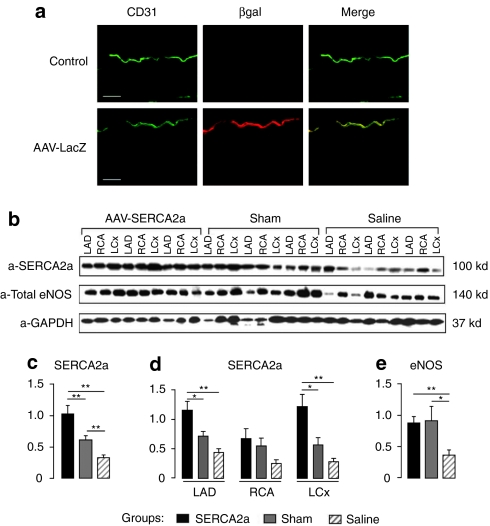

To determine the ability of AAV to transduce vascular cells during intracoronary infusion directly into the LAD artery, AAV1 encoding β-galactosidase (βgal) gene (AAV1.βgal) was infused into the LAD artery lumen of a normal pig (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

SERCA2a gene transfer increases eNOS expression in coronary arteries from MR animals. (a) βgal immunostaining (red) of the left anterior descending (LAD) of a control pig (upper panel) and of a pig injected with AAV1 encoding βgal (lower panel). CD31 (green) was also used in parallel to stain EC. Bar = 50 µm. (b) Representative western blot analysis (n = 3) of SERCA2a and eNOS protein expression in coronary arteries [left circumflex (LCx), right coronary artery (RCA) and LAD] from three experimental groups: sham-operated (gray bar), MR+saline (hatched bar), and MR+AAV1.SERCA2a (black bar). (c–e) Histograms showing relative SERCA2a and eNOS ratios normalized against GAPDH used as a control. The data shown are mean ± SEM (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 versus saline); (c) relative expression of SERCA2a in coronary arteries from different group of animals; (d) relative expression of SERCA2a in LAD, RCA, and LCx from different animal groups; (e) relative expression of eNOS in coronary arteries from different animal groups. AAV, adeno-associated virus; βgal, β-galactosidase; EC, endothelial cell; eNOS, endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; MR, mitral regurgitation; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a.

Two weeks after injection, X-gal-positive cells (blue) were detected at the luminal edge of the injected LAD artery, corresponding to EC layer (data not shown). No X-gal-positive cells were observed in the media or adventitial layers. The X-gal-positive ECs were not detected in the left circumflex or the right coronary artery of the injected animal as the injection was performed specifically in the LAD artery. Confocal microscopy immunofluorescence analysis using an endothelium-specific marker—anti-CD31 and in parallel anti-βgal antibodies revealed a significant transgene expression of βgal in EC layer of LAD artery transduced with AAV1.βgal compared to control noninfected animals (Figure 3a). These data demonstrate that following intracoronary infusion, AAV1 transduces only the EC of injected vessels.

Western blot analysis demonstrated that both SERCA2a and eNOS protein expressions were downregulated in the coronary arteries from failing saline-injected animals (Figure 3b–e). Two way analysis of variance indicated a significant effect of both treatment and EC origin P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively. Intracoronary injection of AAV1.SERCA2a increased the overall expression of SERCA2a in coronary arteries as compared to saline-treated and sham-operated animals (Figure 3). Group-specific analysis demonstrated that the increase in SERCA2a expression was significant only in the LAD artery and left circumflex groups but not in the right coronary artery (Figure 3d), indicating that the increase of SERCA2a expression was restricted to the arteries in which the virus was injected. Similarly, coronary artery expression of eNOS was significantly higher in failing hearts treated with AAV1.SERCA2a compared to failing saline-injected hearts (Figure 3e) and similar to that observed in sham-operated hearts.

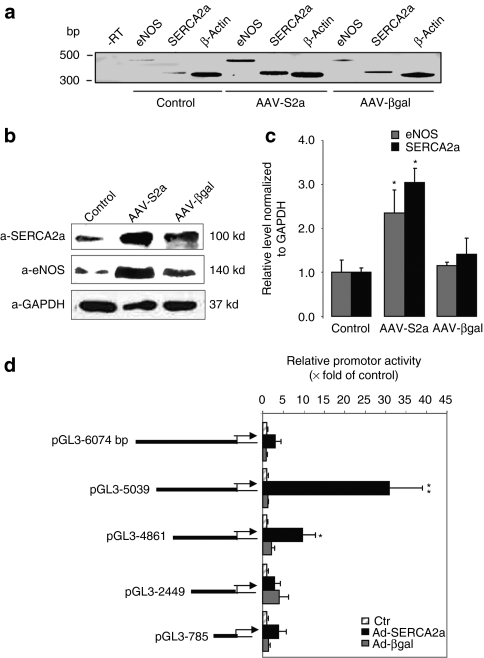

SERCA2a overexpression enhances eNOS expression in vitro

SERCA2a was detected in cultured human coronary artery EC (HCAEC) by reverse transcriptase-PCR (Figure 4a) and western blot analysis (Figure 4b). Infection of HCAECs with rAAV1.SERCA2a for 7 days increased eNOS mRNA (Figure 4a) and protein expression significantly (Figure 4b,c) compared to noninfected or βgal-infected cells. To examine whether SERCA2a is involved in the transcriptional activation of eNOS, five truncated promoter regions located upstream of the human eNOS gene in fusion constructs with the luciferase gene21 were analyzed for their ability to respond to SERCA2a overexpression (48 hours; Figure 4d). In SERCA2a-infected HCAECs, transcription induction was observed with the 5,039-bp heNOS construct (30.9 ± 8.7-fold, versus control n = 3) and with the 4,861-bp heNOS construct (9.6 ± 3.30-fold, versus control, n = 3). This response was reduced with the full length 6,047-bp construct (3.0 ± 2.26-fold, versus control n = 3) and was abolished with the shorter 2,449-bp and 785-bp constructs. Much lower levels of induction (3.75 ± 0.7-fold, versus control n = 3, for 5,039-bp heNOS construct) were obtained with non-ECs that do not express eNOS (HEK 293 cells, data not shown), suggesting that the endothelial-specific transcription factors are necessary for the efficient transcription of the eNOS gene. These data indicate that SERCA2a-response enhancer elements are located between bp −4861 and −5039 of eNOS promoter and that repressor elements are present in the full-length promoter between bp −5039 and −6074. Thus, SERCA2a overexpression increases eNOS expression by enhancing transcriptional activation of the human eNOS promoter.

Figure 4.

SERCA2a overexpression increases NOS expression in HCAEC. (a) Reverse trancriptase-PCR analysis of eNOS and SERCA2a mRNAs in HCAEC cells infected with AAV1-S2a or AAV1-βgal for 6 days. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (b) Representative western blot of lysates from noninfected or infected with either AAV1-SERCA2a or AAV1-βgal HCAEC. (c) Histogram showing the relative ratio of eNOS (gray bar), and SERCA2a (black bar) normalized to GAPDH in three experiments. The values were expressed as a percentage of the value obtained for the control in the same blot. The data are mean ± SEM of three experiments (*P < 0.05 versus control). (d) Functional analysis of the human eNOS promoter in HCAEC after infection with Ad-SERCA2a or Ad-βgal. Large-scale analysis of the human eNOS promoter using deletion mutants of 6,047-bp upstream region in fusion with the luciferase gene. Relative promoter activity is expressed as a percentage of luciferase activity in control noninfected cells. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three experiments (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 versus control). AAV, adeno-associated virus; Ad, adenovirus; eNOS, endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; HCAEC, human coronary artery endothelial cell; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a.

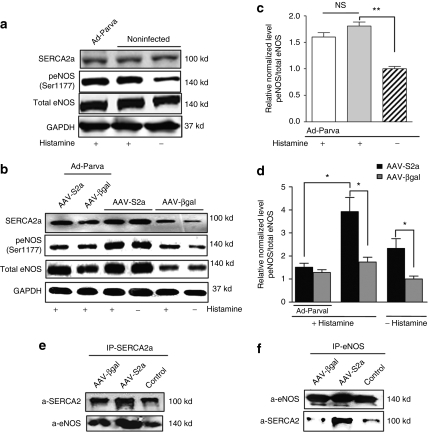

SERCA2a overexpression induces eNOS activation through Ser1177 phosphorylation

Next, we tested whether SERCA2a increases eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 (Figure 5). Infection of HCAECs with AAV1.SERCA2a for 7 days resulted in an increase in SERCA2a expression that was associated with an increase in eNOS protein expression and Ser1177 phosphorylation compared to control noninfected cells (Figure 5c) and βgal-infected cells (Figure 5d). Histamine treatment (1 µmol/l, 10 min) resulted in an increase of eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 in control, βgal-, or SERCA2a-infected cells (Figure 5a–d). Overexpression of parvalbumin, a protein that buffers intracellular Ca2+ ions, had no effect on Ser1177 phosphorylation in noninfected or βgal-infected cells. In contrast, parvalbumin significantly decreased the effect of histamine on Ser1177 phosphorylation in SERCA2a-overexpressing cells (Figure 5c,d). Together, these data demonstrate that the effect of SERCA2a on histamine-mediated phosphorylation of eNOS is dependent on Ca2+ signaling.

Figure 5.

SERCA2a overexpression increases eNOS phosphorylation in Ser1177. Western blot analysis (a,b) with indicated antibodies and histogram (c,d) showing relative ratio of p(Ser1177) eNOS/total eNOS in control (c), βgal- (gray bar), or SERCA2a-infected cells (black bar) (d). The values were expressed as a percentage of the value obtained for the control or βgal nonstimulated cells in the same blot. The results are mean ± SEM of three experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01). (e,f) Immunoprecipitation analysis of functional association between SERCA2a and eNOS in HCAEC. Cell lysates were incubated with (e) SERCA2a or (f) eNOS antibodies. The immune complexes were collected with protein A/G-agarose beads and revealed by western blot analysis. eNOS, endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase; HCAEC, human coronary artery endothelial cell; NS, nonsignificant; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a.

To determine whether SERCA2a and eNOS can interact in a cellular environment, lysates from HCAECs were immunoprecipitated with anti-SERCA2a or with anti-eNOS antibodies (Figure 5e,f). Reciprocally, anti-eNOS and anti-SERCA2a immunoprecipitates were immunoblotted with a-pan SERCA2 and anti-eNOS antibodies. In AAV-SERCA2a-infected cells, exogenous SERCA2a and eNOS were coimmunoprecipitated. A small amount of endogenous SERCA2a was also found to be associated with eNOS after immunoprecipitation with the anti-eNOS antibodies in noninfected and AAV.βgal-infected cells (Figure 5f). These results indicate that SERCA2a and eNOS interact with each other and SERCA2a–eNOS protein–protein complexes may indeed be formed in ECs.

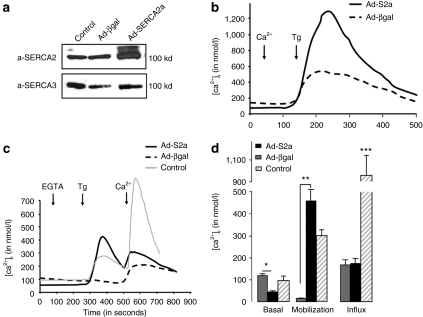

SERCA2a overexpression modulates calcium homeostasis in HCAECs

To investigate the mechanism underlying the role of SERCA2a in modulating eNOS activity, we examined calcium handling in SERCA2a-infected HCAECs. SERCA2a was expressed in normal HCAECs together with SERCA3 (Figure 6a). Adenovirus gene transfer of SERCA2a significantly increased the levels of total SERCA2 protein expression without modification of SERCA3 expression (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

SERCA2a gene transfer modulates calcium cycling in HCAEC. (a) Representative western blot of lysates from HCAEC noninfected or infected either with AAV1.SERCA2a or AAV1.βgal. Expression of SERCA2 and SERCA3 was revealed with an anti-pan SERCA2 (IID8) and an anti-pan SERCA3 (PLIM/430), respectively. (b–d) Effect of SERCA2a overexpression in HCAEC on [Ca2+]i: basal level, mobilization, and capacitative entry. At the time of the experiment (b) 1 mmol/l of CaCl2 (Ca2+) or (c) 100 µmol/l EGTA was added as indicated, and cells were then stimulated with 1 µmol/l of thapsigargin (Tg) for 4 minutes. (b) To observe the calcium capacitative entry, 300 µmol/l of CaCl2 (Ca2+) was then added to the medium. (d) Histograms showing the means ± SEM of the basal level in [Ca2+]i, Ca2+ release in response to Tg, and Ca2+ influx observed after addition of extracellular CaCl2. Representative of eight experiments obtained with four independent infections. (***P < 0.01, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05 versus βgal). AAV1, adeno-associated virus, βgal, β-galactosidase; EGTA, ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid; HCAEC, human coronary artery endothelial cell; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a.

Analysis of calcium handling in Fura-2 loaded cells demonstrated that SERCA2a-overexpressing HCAECs displayed a lower basal level of [Ca2+]i compared to noninfected or βgal-infected cells. A significant increase in the Ca2+ response to thapsigargin in the presence (Figure 6b) or absence (Figure 6c) of extracellular calcium was observed in SERCA2a-overexpressing cells compared to control and βgal-infected cells. This was due to a higher Ca2+ release from intracellular stores in response to thapsigargin as no modification of subsequent Ca2+ entry (store-operated calcium entry) was observed when compared to βgal-infected cells (Figure 6c,d). These data demonstrate that SERCA2a overexpression increases the Ca2+ storage capacity of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) but has no effect on the thapsigargin-induced Ca2+ capacitative entry.

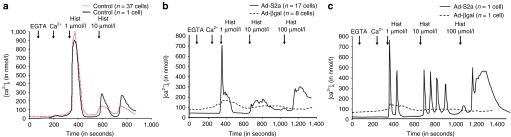

Classically, eNOS activity is regulated by the intracellular calcium transient.22 We conducted a series of experiments to analyze the effect of histamine on calcium transients in HCAECs (Figure 7a–c). Both the amplitude and duration of histamine-induced calcium transients were increased in SERCA2a-infected cells compared to noninfected and βgal-infected cells. Furthermore, SERCA2a overexpression increased the sensitivity of cells to histamine and the frequency of histamine-induced Ca2+ oscillations. This response was not observed in noninfected or βgal-infected cells. In noninfected cells, we observed that thapsigargin-induced store-operated calcium entry was significantly higher than in infected cells (Figure 6c,d) and that the initial response to histamine was also higher in amplitude than that observed in SERCA2a-infected cells, but no oscillations were detected. The difference observed between noninfected and βgal-infected cells might be due to the large expression of GFP,23 or to the infection itself (as the experiments were done 48 hours after infection).

Figure 7.

Effect of SERCA2a overexpression on histamine-induced calcium transient. Calcium responses with increasing histamine doses (1–10 µmol/l) in (a) control are presented as a mean of several cell (black trace) or as a single representative cell (hatched trace), and (b, c) Ad-S2a or Ad-βgal-infected HCAEC stimulated with histamine (1–10 µmol/l) in presence of extracellular calcium (100 µmol/l EGTA plus 300 µmol/l CaCl2) are presented as a mean of several cell or as a single representative cell. Ad, adenovirus; βgal, β-galactosidase; EGTA, ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a; HCAEC, human coronary artery endothelial cell.

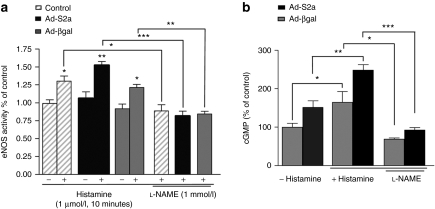

SERCA2a overexpression enhances agonist-induced eNOS activity

Next, we measured the effect of SERCA2a overexpression on eNOS activity and cGMP production in response to the endothelium-dependent agonist histamine (Figure 8a,b). Histamine increased eNOS activity and cGMP production in control, βgal-, and SERCA2a-infected cells. Both eNOS activity and cGMP production were increased significantly in SERCA2a-infected cells compared to control and βgal-infected cells. The effects of the histamine on eNOS activity and cGMP production were completely abolished by preincubation of the cells with NOS inhibitor -NAME, thereby confirming that eNOS was the source of increased NO and cGMP production (Figure 8a,b).

Figure 8.

SERCA2a gene transfer increases eNOS activity and cGMP production in HCAEC. (a) Assessment of eNOS activity in HCAEC by arginine–citrulline conversion assay. Control and infected Ad-S2a or Ad-βgal cells were treated with histamine (1 µmol/l, 10 min) and pretreated with or without -NAME (1 mmol/l) for 20 minutes. The data are mean ± SEM for four experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control). (b) cGMP production was measured using immunoassay. The values were normalized to the total protein content and were expressed as a percentage of the value obtained for the control βgal in the same experiment. The data are mean ± SEM for three experiments (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 versus control). eNOS, endothelial isoform of nitric oxide synthase; HCAEC, human coronary artery endothelial cell; SERCA2a, sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase 2a.

Discussion

SERCA2a is a very promising target for the treatment of HF. Normalization of SERCA2a function has been shown to increase contractility in failing human cardiomyocytes and to improve hemodynamics along with survival in rodent and large animal models of HF.12,13 The overexpression of SERCA2a has also been shown to restore energetics and to decrease ventricular arrhythmias in an ischemia/reperfusion.14,24,25 We have also demonstrated previously that transcoronary gene transfer of SERCA2a increases CF in a rat HF model.18 This study extends these results by showing that long-term overexpression of SERCA2a by in vivo intracoronary AAV1.SERCA2a gene transfer in a large animal model of HF can increase CF and restore eNOS expression in coronary artery ECs.

We have reported previously that a single intracoronary AAV1.SERCA2a infusion in this HF model results in significant improvements in contractile function and restoration of ventricular volumes compared with untreated animals.20 As CF has a linear relationship with cardiac output and occurs predominantly during diastole, diastolic function is an important determinant of CF. In this study, we observed a trend toward improved diastolic function in the AAV1.SERCA2a group compared to the saline group, although this finding was not statistically significant.20 We cannot, however, exclude that the overall benefit of SERCA2a gene transfer on the failing myocardium, including metabolic, energetic, and contractile rescue, could also influence coronary artery function. A second plausible explanation for the observed increase in CF in AAV1.SERCA2a-treated animals is improved endothelial function and increased NO production as a result of SERCA2a overexpression in EC. We demonstrated here that the intracoronary delivery of AAV1 results in efficient transduction of EC in injected vessels. Our data are in agreement with other in vivo studies that demonstrated that AAV transduced only EC in uninjured vessels,26 suggesting that both the EC and the internal elastic lamina might serve as barriers to prevent AAV penetration into the medial layer of vessel. Furthermore, our studies clearly document an increase in SERCA2a expression in coronary arteries from failing hearts following AAV1.SERCA2a infection compared to the saline-injected group.

The influence of HF on eNOS expression remains controversial. Decreased NO production with no change or increased vascular eNOS protein expression has been reported in animal models and human subjects with HF.27,28,29,30 In contrast, eNOS mRNA and protein expression have also been shown to be decreased in coronary microvessels and aorta EC from dogs with HF.6,30,31,32 In concordance with these latter results, we found decreased eNOS protein expression in coronary vessels from porcine failing hearts. Furthermore, we demonstrated that SERCA2a is also downregulated in HF coronary arteries and that the intracoronary injection of AAV1.SERCA2a restored both SERCA2a and eNOS expression leading to improved CF. These results suggest that the decrease in eNOS protein and NO production can be related directly to the decrease in SERCA2a expression in ECs during HF.

Furthermore, we demonstrated here that eNOS expression was increased in SERCA2a-overexpressing HCAECs as a result of SERCA2a-mediated activation of the eNOS promoter. Other investigators have reported that histamine treatment upregulates gene expression of eNOS in human EC,33 suggesting that the eNOS promoter contains a calcium-sensitive element. SERCA2a appears to play a role in the induction of eNOS transcription via an element in the promoter region from bp −5,039 to −4,861. This region was shown to contain a 269-bp activator element acting as an enhancer of transcription.21 This enhancer contains myeloid zinc finger–like, AP-2, Sp1, and Ets binding sites and is important for the endothelial specificity of eNOS promoter.21 We have also shown that Ets and Sp1 transcription factors were necessary for the regulation of SERCA gene transcription in EC.34 It has also been reported that increased SERCA activity enhanced agonist-induced NO synthesis,19 which, in turn, led to an NO-mediated feedback inhibition of SERCA activity.35 Thus, the observed increase of eNOS expression in SERCA2a-overexpressing ECs may be a compensatory adaptation to increased SERCA activity.

We also demonstrated that in SERCA2a-overexpressing cells, phosphorylation of eNOS Ser1177 was increased in the basal state. Furthermore, we demonstrated by coimmunoprecipitation that SERCA2a and eNOS are associated in a functional protein–protein complex. This indicates that both proteins are localized in a similar calcium environment and also suggests that SERCA2a may directly control eNOS activity.

SERCA2a overexpression in HCAECs leads to increased ER Ca2+ storage and mobilization without any changes in store-operated calcium entry. Furthermore, SERCA2a overexpression increased the sensitivity of cells to histamine and the amplitude of histamine-induced Ca2+ oscillations. Our results indicate that increasing the ER Ca2+ content and mobilization can contribute to the increase of the frequency of histamine-induced Ca2+ oscillations and thus to an increase in eNOS activity and cGMP production in EC. These results confirm prior observations demonstrating that increased SERCA activity by overexpression of S100A1 also increased NO production in EC.19

In conclusion, in a preclinical volume-overload model of HF, decreased coronary blood flow is associated with downregulation of SERCA2a and eNOS protein expression in coronary arteries. Long-term overexpression of SERCA2a by in vivo AAV1-mediated gene transfer (via intracoronary delivery), in addition to other benefits effect on contractile function,12,13 can preserve CF by increasing eNOS expression in coronary arteries. SERCA2a overexpression in cultured HCAECs enhanced ER calcium content and agonist-induced calcium cycling resulting in increased eNOS expression and activity. Our results suggest that increased CF occurring after intracoronary SERCA2a gene transfer in a HF model may be due to increased eNOS expression and activity in coronary artery EC.

Materials and Methods

Animal were handled as approved by the local Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees in accordance with the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care by the National Society for Medical research and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals” (NIH Publication no. 86-23, revised 1985).

Porcine volume-overload HF model, virus injection and CF measurement. Mitral regurgitation was created in 26 female Yorkshire-Landrace swine (33.5 ± 1.8 kg) to induce volume-overload HF as described previously.20 Subsequently, 1012 DNAse resistant particles of rAAV1.SERCA2a solution or a similar volume of saline was diluted in buffer (130 mmol/l NaCl, 20 mmol/l HEPES, pH 7.4, 1 mmol/l MgCl2, total volume of 10 ml). The mixture was then mixed with 10 ml of autologous whole blood in preparation for injection. A 7-F femoral artery sheath was placed and a coronary guiding catheter was then selectively engaged into the left main coronary artery ostium. After confirming catheter positioning by coronary angiogram, either rAAV1.SERCA2a or saline was delivered via a standard infusion pump over 10 minutes. To confirm the specificity of virus-directed tissue transduction, the AAV1.βgal was infused to control swine. Two months after gene transfer, 13 surviving animals (7 for AAV1.SERCA2a group and 6 for saline group) were subjected to hemodynamic and coronary blood flow (CF) measurements.20 The average CF peak velocity (APV) was measured in the mid-portion of the LAD artery using a 0.014-inch FloWire (Volcano Therapeutic, Rancho Cardova, CA) and flow map velocity calculation system (Endosonics, Rancho Cardova, CA). At the end of the measurement of APV, a coronary angiogram was performed to measure the diameter of the coronary artery (D) at the CF measurement site. CF was calculated as CF = 1/2APV × 3.14 × (D/2)2 and adjusted for the left ventricular weight (LVW). Adjusted CF (ml/min/g) = CF/LVW.

Confocal microscopy. The LAD, left circumflex, and right coronary arteries, from each animal were collected 4 months after gene transfer. The tissue sections (8 µm) were fixed in acetone and used for immunofluorescence. To assess the efficacy of gene transfer, longitudinal sections from each vessel were labeled with a-eNOS (BD Transduction Laboratories, Franklin Lakes, NJ), a-PECAM-1[CD31] (Abcys biologie, Paris, France), a-βgal, and a-SERCA2a36 antibodies followed by TRITC-labeled secondary antibody. Multitrack mode (images taken sequentially) was achieved using the argon and He/Ne lasers.

To assess efficacy of gene transfer, AAV1.βgal or saline was infused in the LAD artery of four normal pigs. One month postinfusion, the coronary arteries were harvested and tissue sections were paraffin embedded, These sections were then immunostained using goat polyclonal antibody to PECAM-1 followed by secondary donkey-anti-goat FITC (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) to identify ECs. To assess level of βgal expression, we used chicken polyclonal antibody to βgal followed by a rabbit anti-chicken Rhodamine (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Multitrack mode (images taken sequentially) was achieved using the argon and He/Ne lasers. Bar = 50 µm.

Cell culture. HCAECs (Lonza) were cultured in EGM-2 MV medium. HCAECs from passages 3–5 were used. At 80% confluency, the cells were infected with either AAV1-CMV.SERCA2a or AAV1-CMV.βgal (105 DNA-resistant particles/cell) for 7 days. In several experiments, we used adenovirus under the cytomegalovirus promoter encoding SERCA2a (Ad-S2a, 100 multiplicity of infection/cell) or βgal (Ad-βgal, 100 multiplicity of infection/cell; ref. 37), or adenovirus encoding parvalbumin (Ad-parva, 100 multiplicity of infection/cell; ref. 38) for 48 hours.

RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase-PCR. Reverse transcriptase-PCR was performed using total RNA from HCAEC. Fragments were amplified for 30 cycles with the following specific primers: β-actin-F: GGTCAAACAAACATGATCTGGG; β-actin-R: GGTCTCAAACATGATCTGGG; eNOS-F: GCTGCGCCAGGCTCTCACCTTC; eNOS-R: GGCTGCAGCCCTTTGCTCTCAA; h-SERCA2a-F: GTTCGGTTGCGTGCATGTCGT; h-SERCA2a-R: ATGTGGCGACTTGGCTGACGGC.

eNOS-promoter-luciferase assay. HCAECs were transfected with the plasmid constructs encoding the truncated human eNOS-promoter regions in fusion with the luciferase gene21,39 for 4 hours and then infected with Ad-S2a or Ad-βgal for 48 hours. Luciferase activity was measured by using luciferase assay kit (Promega, Winston-Salem, NC). Results were expressed as percentage of control noninfected cells in relative luciferase units.

Measurement of intracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i). HCAECs were infected with Ad-S2a or Ad-βgal for 48 hours. Cells were loaded with 2 µmol/l Fura-2-AM for 45 minutes at 37 °C and kept in serum-free medium for 30 minutes before the experiment. HEPES buffer (in mmol/l: 116 NaCl, 5.6 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 5 NaHCO3, 1 NaH2PO4, 20 HEPES pH 7.4) was used for the experiments. Single images of fluorescent emission at 510 nm under excitation at 340 and 380 nm were taken every 5 seconds. Changes in [Ca2+]i in response to the indicated agonist were monitored using the FURA-2 340/380 fluorescence ratio. Ca2+ release and influx were given as maximal rise [Ca2+]i after agonist addition over the basal level.

eNOS activity and cGMP assays. eNOS activity was measured using a commercial assay kit (Calbiochem, EMD4 Biosciences, San Diego, CA). cGMP was measured using a immunoassay kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Results were expressed as percentage increase in which the maximum response in control is defined as 100%.

Coimmunoprecipitation and western blot. HCAEC lysates were incubated with prewashed protein A/G-Sepharose beads (50 µl; Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) for 1 hour, before incubation with primary antibody anti-eNOS antibody (5 µg/ml; BD Transduction Laboratories), with pan anti-SERCA2 (ABR-Affinity Bioreagents, Golden, CO) or a-specific SERCA2a (Century 21st Biochemicals, Marlborough, MA) overnight at 4 °C with gentle shaking. Prewashed Sepharose beads were further incubated with lysate/antibody mixture for 1–2 hours. Beads were washed three times in 800 µl of ice-cold wash buffer. Proteins were resolved by 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequent western blot analysis. After transfer, the membranes were immunoblotted with anti-eNOS or a-peNOS (1:1,000; BD Transduction Laboratories, San Jose, CA), anti-SERCA3 (1:1,000, PLIM/430), anti-SERCA2 (1:1,000; Abcam), a-SERCA2a (1:1,000), overnight at 4 °C. Proteins were visualized using a horseradish peroxidase–conjugated goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody and an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit (Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). The membrane was divided in two: the upper part was hybridized with a-SERCA and anti eNOS whereas the lower part was hybridized with a-GAPDH (IMGENEX, San Diego, CA).

Statistical analysis. The results are presented as means ± SEM. Statistical differences were analyzed using one-way or two-way analysis of variance and pairwise comparisons were determined using Tukey's honest significance test with *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL Figure S1. Confocal immunofluorescence analysis of porcine coronary arteries.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by Leducq Foundation through the Caerus network (research agreement 05 CVD 03 to A.-M.L., E.G.K. and R.J.H.), by NIH R01 HL078691, HL057263, HL071763, HL080498, and HL083156 (R.J.H.), by NIH HL26057, HL64018, and HL77101 (E.G.K.) by AHA SDG 0930116N (L.L.), by the Association Française Contre les Myopathies, AFM (R.B.), and by NIH HL81110 and HL700819 (J.A.L.). We thank Sophie Nadaud (INSERM/UPMC UMRS 956, CHU Pitié-Salpêtrière Paris, France) for providing human eNOS-promoter constructs and Jocelyne Enouf (INSERM U689, Hôpital Lariboisière, Paris, France) for a-SERCA3 (PLIM/430).

Supplementary Material

Confocal immunofluorescence analysis of porcine coronary arteries.

REFERENCES

- Drexler H, Hayoz D, Münzel T, Just H, Zelis R., and, Brunner HR. Endothelial function in congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 1993;126:761–764. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90926-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo SH, Rector TS, Bank AJ, Williams RE., and, Heifetz SM. Endothelium-dependent vasodilation is attenuated in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 1991;84:1589–1596. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.4.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohri M, Egashira K, Tagawa T, Kuga T, Tagawa H, Harasawa Y, et al. Basal release of nitric oxide is decreased in the coronary circulation in patients with heart failure. Hypertension. 1997;30:50–56. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure CB, Vita JA, Cox DA, Fish RD, Gordon JB, Mudge GH, et al. Endothelium-dependent dilation of the coronary microvasculature is impaired in dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1990;81:772–779. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.3.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Shen W, Xu X, Ochoa M, Bernstein R., and, Hintze TH. Selective impairment of vagally mediated, nitric oxide-dependent coronary vasodilation in conscious dogs after pacing-induced heart failure. Circulation. 1995;91:2655–2663. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.10.2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CJ, Sun D, Hoegler C, Roth BS, Zhang X, Zhao G, et al. Reduced gene expression of vascular endothelial NO synthase and cyclooxygenase-1 in heart failure. Circ Res. 1996;78:58–64. doi: 10.1161/01.res.78.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming I., and, Busse R. Molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;284:R1–12. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00323.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paltauf-Doburzynska J, Frieden M, Spitaler M., and, Graier WF. Histamine-induced Ca2+ oscillations in a human endothelial cell line depend on transmembrane ion flux, ryanodine receptors and endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. J Physiol (Lond) 2000;524:701–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00701.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobe R, Bredoux R, Corvazier E, Lacabaratz-Porret C, Martin V, Kovács T, et al. How many Ca(2)+ATPase isoforms are expressed in a cell type? A growing family of membrane proteins illustrated by studies in platelets. Platelets. 2005;16:133–150. doi: 10.1080/09537100400016847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mountian II, Baba-Aissa F, Jonas JC, Humbert De S, Wuytack F, Parys JB. Expression of Ca2+ transport genes in platelets and endothelial cells in hypertension. Hypertension. 2001;37:135–141. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipskaia L, Pourci ML, Deloménie C, Combettes L, Goudounèche D, Paul JL, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and calcium-activated transcription pathways are required for VLDL-induced smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ Res. 2003;92:1115–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000074880.25540.D0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase Y., and, Hajjar RJ. The cardiac sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase: a potent target for cardiovascular diseases. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:554–565. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipskaia L, Chemaly ER, Hadri L, Lompre AM., and, Hajjar RJ. Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) ATPase as a therapeutic target for heart failure. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2010;10:29–41. doi: 10.1517/14712590903321462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Monte F, Lebeche D, Guerrero JL, Tsuji T, Doye AA, Gwathmey JK, et al. Abrogation of ventricular arrhythmias in a model of ischemia and reperfusion by targeting myocardial calcium cycling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5622–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305778101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Monte F, Williams E, Lebeche D, Schmidt U, Rosenzweig A, Gwathmey JK, et al. Improvement in survival and cardiac metabolism after gene transfer of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+)-ATPase in a rat model of heart failure. Circulation. 2001;104:1424–1429. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.095574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto MI, del Monte F, Schmidt U, DiSalvo TS, Kang ZB, Matsui T, et al. Adenoviral gene transfer of SERCA2a improves left-ventricular function in aortic-banded rats in transition to heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:793–798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjar R., and, Fuster V. Cardiac cell and gene therapies: two trajectories, one goal. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5:749. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata S, Lebeche D, Sakata Y, Sakata N, Chemaly ER, Liang L, et al. Transcoronary gene transfer of SERCA2a increases coronary blood flow and decreases cardiomyocyte size in a type 2 diabetic rat model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H1204–H1207. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00892.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleger ST, Harris DM, Shan C, Vinge LE, Chuprun JK, Berzins B, et al. Endothelial S100A1 modulates vascular function via nitric oxide. Circ Res. 2008;102:786–794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.172031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawase Y, Ly HQ, Prunier F, Lebeche D, Shi Y, Jin H, et al. Reversal of cardiac dysfunction after long-term expression of SERCA2a by gene transfer in a pre-clinical model of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laumonnier Y, Nadaud S, Agrapart M., and, Soubrier F. Characterization of an upstream enhancer region in the promoter of the human endothelial nitric-oxide synthase gene. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:40732–40741. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004696200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stefano GB, Prevot V, Beauvillain JC, Fimiani C, Welters I, Cadet P, et al. Estradiol coupling to human monocyte nitric oxide release is dependent on intracellular calcium transients: evidence for an estrogen surface receptor. J Immunol. 1999;163:3758–3763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbulut O, Coirault C, Niederländer N, Huet A, Vicart P, Hagège A, et al. GFP expression in muscle cells impairs actin-myosin interactions: implications for cell therapy. Nat Methods. 2006;3:331. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0506-331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata S, Lebeche D, Sakata N, Sakata Y, Chemaly ER, Liang LF, et al. Restoration of mechanical and energetic function in failing aortic-banded rat hearts by gene transfer of calcium cycling proteins. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:852–861. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata S, Lebeche D, Sakata Y, Sakata N, Chemaly ER, Liang LF, et al. Mechanical and metabolic rescue in a type II diabetes model of cardiomyopathy by targeted gene transfer. Mol Ther. 2006;13:987–996. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda Y, Ikeda U, Ogasawara Y, Urabe M, Takizawa T, Saito T, et al. Gene transfer into vascular cells using adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors. Cardiovasc Res. 1997;35:514–521. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(97)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauersachs J, Bouloumié A, Fraccarollo D, Hu K, Busse R., and, Ertl G. Endothelial dysfunction in chronic myocardial infarction despite increased vascular endothelial nitric oxide synthase and soluble guanylate cyclase expression: role of enhanced vascular superoxide production. Circulation. 1999;100:292–298. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare JM, Lofthouse RA, Juang GJ, Colman L, Ricker KM, Kim B, et al. Contribution of caveolin protein abundance to augmented nitric oxide signaling in conscious dogs with pacing-induced heart failure. Circ Res. 2000;86:1085–1092. doi: 10.1161/01.res.86.10.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein B, Eschenhagen T, Rüdiger J, Scholz H, Förstermann U., and, Gath I. Increased expression of constitutive nitric oxide synthase III, but not inducible nitric oxide synthase II, in human heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1179–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00399-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao G, Shen W, Zhang X, Smith CJ., and, Hintze TH. Loss of nitric oxide production in the coronary circulation after the development of dilated cardiomyopathy: a specific defect in the neural regulation of coronary blood flow. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1996;23:715–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1996.tb01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damy T, Ratajczak P, Shah AM, Camors E, Marty I, Hasenfuss G, et al. Increased neuronal nitric oxide synthase-derived NO production in the failing human heart. Lancet. 2004;363:1365–1367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Seyedi N, Xu XB, Wolin MS., and, Hintze TH. Defective endothelium-mediated control of coronary circulation in conscious dogs after heart failure. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:H670–H680. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.2.H670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Burkhardt C, Heinrich UR, Brausch I, Xia N., and, Förstermann U. Histamine upregulates gene expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase in human vascular endothelial cells. Circulation. 2003;107:2348–2354. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000066697.19571.AF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadri L, Ozog A, Soncin F., and, Lompré AM. Basal transcription of the mouse sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase type 3 gene in endothelial cells is controlled by Ets-1 and Sp1. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36471–36478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204731200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Sunami O, Saitoh N, Nishio H, Takeuchi T., and, Hata F. Inhibition of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase by nitric oxide. FEBS Lett. 1998;440:218–222. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01460-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JA, Wuytack F, Verbist J., and, Casteels R. Expression of endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2(+)-pump isoforms and of phospholamban in pig smooth muscle tissues. Biochem J. 1990;271:649–653. doi: 10.1042/bj2710649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipskaia L, del Monte F, Capiod T, Yacoubi S, Hadri L, Hours M, et al. Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase gene transfer reduces vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation in the rat. Circ Res. 2005;97:488–495. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000180663.42594.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq F, Lebeche D, Iyer V, Liao R., and, Hajjar RJ. Gene transfer of parvalbumin improves diastolic dysfunction in senescent myocytes. Circulation. 2004;109:2780–2785. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000131764.62242.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coulet F, Nadaud S, Agrapart M., and, Soubrier F. Identification of hypoxia-response element in the human endothelial nitric-oxide synthase gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46230–46240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305420200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Confocal immunofluorescence analysis of porcine coronary arteries.