Abstract

A nitrated guanine nucleotide, 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-nitro-cGMP), is formed via nitric oxide (NO) and causes protein S-guanylation. However, intracellular 8-nitro-cGMP levels and mechanisms of formation of 8-nitro-cGMP and S-guanylation are yet to be identified. In this study, we precisely quantified NO-dependent formation of 8-nitro-cGMP in C6 glioma cells via liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Treatment of cells with S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine led to a rapid, transient increase in cGMP, after which 8-nitro-cGMP increased linearly up to a peak value comparable with that of cGMP at 24 h and declined thereafter. Markedly high levels (>40 μm) of 8-nitro-cGMP were also evident in C6 cells that had been stimulated to express inducible NO synthase with excessive NO production. The amount of 8-nitro-cGMP generated was comparable with or much higher than that of cGMP, whose production profile slightly preceded 8-nitro-cGMP formation in the activated inducible NO synthase-expressing cells. These unexpectedly large amounts of 8-nitro-cGMP suggest that GTP (a substrate of cGMP biosynthesis), rather than cGMP per se, may undergo guanine nitration. Also, 8-nitro-cGMP caused S-guanylation of KEAP1 in cells, which led to Nrf2 activation and subsequent induction of antioxidant enzymes, including heme oxygenase-1; thus, 8-nitro-cGMP protected cells against cytotoxic effects of hydrogen peroxide. Proteomic analysis for endogenously modified KEAP1 with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight-tandem mass spectrometry revealed that 8-nitro-cGMP S-guanylated the Cys434 of KEAP1. The present report is therefore the first substantial corroboration of the biological significance of cellular 8-nitro-cGMP formation and potential roles of 8-nitro-cGMP in the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response.

Keywords: Antioxidant, Cyclic GMP (cGMP), Cyclic Nucleotide Analogs, Cyclic Nucleotides, Nitric Oxide, Oxidative Stress, Post-translational Modification, Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) plays diverse physiological roles in vascular regulation, neuronal transmission, inflammation, and host defense against microbial pathogens. In vascular and neuronal systems, NO performs these functions mainly through a cGMP-dependent mechanism (1, 2), but the presence and contribution of other pathways that are not directly linked to cGMP have also been suggested to operate in certain aspects of NO signaling occurring in various cells and tissues in different organisms (3–5). Among these other mechanisms is chemical modification of biomolecules, including nitrosylation and nitration of amino acids, proteins, and lipids, this modification being induced by NO-derived reactive nitrogen oxide species (RNOS),3 such as peroxynitrite (ONOO−) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) (3–5).

RNOS cause nitration of nucleic acids in addition to amino acids, proteins, and lipids. We previously found that nitrated guanine derivatives, including 8-nitroguanine and 8-nitroguanosine, formed in cultured cells and in tissues from murine viral pneumonia and human lung disease (6–8). An important finding was that 8-nitroguanosine possessed a unique redox activity, which suggested a critical biological role of guanine nitration (9). In fact, we recently discovered that a novel nitrated cyclic nucleotide, 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (8-nitro-cGMP), is generated after NO production (10). 8-Nitro-cGMP had the strongest redox activity among the nitrated guanine derivatives tested, and this property was distinct from that activating cGMP-dependent protein kinases. Being an electrophile, 8-nitro-cGMP effectively reacted with sulfhydryl groups of cysteine residues and formed a protein-S-cGMP adduct, via a post-translational modification named protein S-guanylation (10).

Although we successfully determined the chemical identification of 8-nitro-cGMP in our earlier study (10), we had not yet achieved rigorous quantification of 8-nitro-cGMP in biological systems (e.g. cells), and mechanisms of 8-nitro-cGMP action were still to be clarified. One specific question concerned what constituted a target molecule for nitration: GTP, a substrate of soluble guanylate cyclase (sGC), or its product cGMP? Also, downstream signaling pathways of 8-nitro-cGMP were not fully understood.

In this context, we identified the redox sensor protein Keap1 (Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1) as one of the major targets for S-guanylation, albeit the physiological significance and structural characterization of Keap1 S-guanylation remain to be elucidated (10, 11). The Keap1-Nrf2 (nuclear factor-erythroid 2-related factor 2) system is one of the major cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative and electrophilic stresses (12–15). Nrf2 is a transcription factor regulating phase 2-detoxifying enzymes and antioxidant enzymes that act in cytoprotection against electrophiles and reactive oxygen species (ROS). Under quiescent conditions, Nrf2 is ubiquitinated and rapidly degraded by proteasome. Nrf2 is ubiquitinated specifically by an E3 ligase harboring Keap1, which localizes in the perinuclear cytoplasm (16) and serves as an adaptor of the Cul3-based ubiquitin ligase complex for Nrf2. Upon exposure to electrophiles or oxidative stresses, Nrf2 is stabilized and translocated into nuclei, which results in induction of a battery of cytoprotective genes.

Electrophiles have been shown to attack the highly reactive cysteine residues in Keap1, and covalent modification of the cysteine thiols inactivates Keap1-based E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. From several in vitro conjugation experiments, it became clear that electrophiles modify a certain combination of cysteine residues (17–22). In fact, we identified three cysteine residues (Cys151, Cys273, and Cys288) that are critical to Keap1 activity to repress Nrf2 and/or the Keap1 response to electrophiles (23). These data were obtained by means of a complementation rescue experiment with Keap1-null mice and KEAP1-expressing or mutant KEAP1-expressing transgenic lines of mice (23).

In the present study, we attempted to elucidate the quantitative and mechanistic aspects of 8-nitro-cGMP in the cells and the potential roles of 8-nitro-cGMP in protein S-guanylation during signal transduction induced by NO. We first demonstrated prolonged and significant intracellular accumulation of 8-nitro-cGMP after NO production in C6 rat glioma cells. A surprising finding was that the level of 8-nitro-cGMP formation was comparable with or higher than that of cGMP primarily formed in cells. More important is the functional consequence; 8-nitro-cGMP thus generated induced S-guanylation of Keap1 and increased Nrf2-dependent gene expression. Therefore, 8-nitro-cGMP was cytoprotective against adverse effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) through increasing expression of Nrf2 target genes, such as HO-1 (heme oxygenase-1 gene). We subsequently identified, via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF)-tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), one critical cysteine residue of KEAP1, Cys434, which was modified by 8-nitro-cGMP in cells. This study thus provides substantial evidence of both the biological significance and the elaborate formation mechanism of the appreciable quantity of 8-nitro-cGMP formed in cells. Another cutting edge achievement of our study is discovery of a new mode of electrophilic sensing by Keap1, which confirmed our belief that electrophilic stimuli are converted into a signal that is translated into the cysteine code in the Keap1 molecule to confer Nrf2 activation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Synthesis of Various Guanine Nucleotides

Authentic 8-nitro-cGMP labeled or unlabeled with a stable isotope (8-15NO2-cGMP and 8-14NO2-cGMP, respectively) was prepared according to the method we reported previously (10). 15N-Labeled cGMP (i.e. [U-15N5, 98%]guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate (c[15N5]GMP)) was synthesized from [U-15N5, 98%]guanosine 5′-triphosphate ([15N5]GTP) (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc., Andover, MA) via an enzymatic reaction by utilizing purified sGC. Specifically, 1 mm [15N5]GTP was incubated with sGC purified from bovine lung, as described previously (24), in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 12 h, and a product, c[15N5]GMP, of this sGC reaction was then obtained through high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as reported earlier (10). In certain experiments, 8-14NO2-c[15N5]GMP was prepared by direct nitration of c[15N5]GMP with ONOO−, as reported earlier (9). These stable isotope-labeled guanine nucleotides were used for a spike-and-recovery study with liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS analysis, as described below. Their chemical structures and characteristic fragmentation patterns are illustrated in supplemental Fig. S1.

Cell Treatment

Rat glioma C6 cells were cultured at 37 °C in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cells were plated at a density of 1.4 × 106 cells/well in 6-well plates for preparation of cell lysates for Western blotting and proteomics, at 1.5 × 106 cells/60-mm dish to prepare cell extracts for LC-MS/MS, and at 2 × 105 cells/chamber in BD Falcon Culture Slides (BD Biosciences) for immunocytochemistry. To study 8-nitro-cGMP formation, cells were treated with 50 μm S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI) for various time periods. For induction of inducible NO synthase (iNOS) expression, unless otherwise specified, cells were treated with 10 μg/ml lipopolysaccharide (LPS; from Escherichia coli; L8274) (Sigma), 100 units/ml interferon-γ (IFN-γ), 100 units/ml tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), and 10 ng/ml interleukin-1β (IL-1β) (all cytokines from R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN). In some experiments, to investigate the mechanism of 8-nitro-cGMP production, cells were stimulated in the presence of various inhibitors, including an NOS inhibitor, Nω-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA) (Sigma), the sGC inhibitor NS 2028 (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and an inhibitor of phosphodiesterase 5 (PDE5) (cGMP-specific PDE), zaprinast (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), followed by a series of various analyses for 8-nitro-cGMP formation and 8-nitro-cGMP-related signaling pathways. Moreover, the effect of GSH depletion on 8-nitro-cGMP formation was examined with cells treated or untreated with 1 mm buthionine sulfoximine (BSO) for 8 h and then with SNAP or LPS plus cytokines in the presence of 1 mm BSO. For overexpression of FLAG-tagged mouse KEAP1 (FLAG-KEAP1), cells were transfected with the expression plasmid p3×FLAG-CMV-KEAP1 (23) by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). At 36 h after transfection, FLAG-KEAP1 expressed by the cells was harvested for S-guanylation proteomics, as described below. In addition, to further analyze the effect of 8-nitro-cGMP on the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway, C6 cells overexpressing KEAP1 were treated with authentic 8-nitro-cGMP, followed by proteomic and signal transduction studies.

Quantitative Analysis of 8-Nitro-cGMP and Its Related Nucleotides by Means of LC-MS/MS and HPLC-Electrochemical Detection (ECD)

Intracellular levels of 8-nitro-cGMP as well as cGMP and GTP were measured by LC-electrospray ionization (ESI)-MS/MS and HPLC-ECD. After C6 cells plated on 60-mm dishes were treated with 50 μm SNAP or with a mixture of LPS, INF-γ, TNFα, and IL-1β in 5 ml of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 10% fetal bovine serum for various times, cells were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5 mm N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) (Sigma) and were collected by using a cell scraper (BD Biosciences) in 5 ml of ice-cold PBS containing 5 mm NEM, followed by centrifugation. The cell pellet thus obtained was homogenized in 5 ml of methanol containing 5 mm NEM. After the homogenate samples were centrifuged at 5000 × g at 4 °C, their resultant supernatant was dried in vacuo and then redissolved in distilled water. After the samples were mixed with hexane, an aqueous phase was obtained. This fraction was dried in vacuo and reconstituted with 50 μl of water. This sample was used for LC-ESI-MS/MS and HPLC-ECD analyses.

LC-ESI-MS/MS was performed with a Varian 1200L triple-quadrupole (Q) mass spectrometer (Varian, Inc., Palo Alto, CA), after reverse-phase HPLC on a Mightysil RP-18 column (50 × 2.0-mm inner diameter; Kanto Chemical (Tokyo, Japan)) with a linear 3–100% methanol gradient for 5 min in 0.1% formic acid at 40 °C. Total flow rate was 0.15 ml/min, and injection volume was 20 μl. The column effluent was introduced directly into the mass spectrometer operated in positive mode under the following conditions: collision gas (argon) pressure 2.2 millitorrs, drying gas (nitrogen) pressure 19 p.s.i. at 300 °C, nebulizing gas (nitrogen) pressure 52 p.s.i., scan time 0.2 s, needle voltage 5000 V, shield voltage 600 V, capillary voltage 100 V, and detector voltage 2000 V. LC-MS/MS scanning was performed under the multiple reaction monitoring mode with the scanning parameters shown in Table 1. These parameters were determined with the Automated MS/MS Breakdown software (Varian), using a stock solution of 8-nitro-cGMP and cGMP (10 μg/ml) in 50% methanol containing 0.1% formic acid. HPLC-ECD analysis for 8-nitro-cGMP formation was performed as described previously (10). Intracellular concentrations of various nucleotides were determined from values measured by LC-MS/MS analysis as described in the supplemental material.

TABLE 1.

LC-MS/MS scanning parameters

Values for each compound with a natural mass number (14N) are shown. The same collision energy was used for respective cyclic nucleotides labeled with the stable isotope (15N).

| Analyte | Precursor ion (m/z) | Product ion (m/z) | Collision energy (V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8-Nitro-cGMP | 391 | 197 | −8 |

| cGMP | 346 | 152 | −15 |

Recovery efficiency may vary greatly, depending on the cell treatment conditions and the amount of 8-nitro-cGMP formed in the cells. To ensure the precise determination of various endogenously formed nucleotides, we performed a spike-and-recovery study (i.e. we confirmed the validity of the cell extraction method in terms of nucleotide stability during processing, via verification of overall procedural recovery efficacy). The recovery rates were assessed by quantifying authentic compounds added exogenously by spiking different amounts of various 15N-labeled authentic guanine nucleotides, such as 8-15NO2-cGMP, c[15N5]GMP, and 8-14NO2-c[15N5]GTP, into each cell suspension upon extraction. Each stable isotope-labeled compound was added to the solution of cell extract and methanol, which was followed by preparation of the homogenate and cell extract. The recovered fraction of an authentic compound was determined by comparing its signal with signals of standards used for each spiking study as directly analyzed via LC-MS/MS. For each sample measurement, signals of the endogenous 14N-guanine nucleotides and the respective 15N-labeled derivatives were identified simultaneously, so that the exact values of endogenous nucleotide concentrations were accurately determined after correction by the amounts of derivatives finally recovered with MS analyses. The efficacy and validity of the present spike-and-recovery study are shown in supplemental Fig. S2. In brief, the recovery of endogenous 8-nitro-cGMP was markedly improved; its efficacy was elevated more than 60-fold by spiking with exogenous 15N-labeled 8-nitro-cGMP (i.e. 8-15NO2-cGMP and 8-14NO2-c[15N5]GMP), whereas recovery of cGMP was not appreciably affected by the same c[15N5]GMP spiking. This finding may indicate that a large part of the 8-nitro-cGMP formed in the cells remains as a cellular component during methanol cell extraction but that it can be efficiently stripped off and stabilized by adding the same authentic 15N-labeled compound, which would permit effective quantification of 8-nitro-cGMP via LC-MS/MS analysis.

Immunocytochemistry

For assessment of cellular 8-nitro-cGMP formation, immunocytochemical analysis was carried out by the previously described method (10). In brief, C6 cells, plated on culture slides (BD Biosciences) and treated as described above, were fixed with Zamboni solution (4% paraformaldehyde and 10 mm picric acid in 0.1 m phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) at 4 °C for 7 h. After permeabilization with 0.5% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 15 min, cells were incubated with BlockAce (Dainippon Pharmaceutical, Osaka, Japan) overnight at 4 °C to block nonspecific antigenic sites. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-8-nitro-cGMP monoclonal antibody 1G6 (1 μg/ml) (supplemental material) (10) in Can Get Signal Immunoreaction Enhancer Solution (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan). After three rinses with 10 mm PBS (pH 7.4), cells were incubated with Cy3-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG antibody (GE Healthcare). Cells were stained and then examined with a fluorescence microscope (Axioplan 2, Carl Zeiss (Jena, Germany)) equipped with an AxioCam MRm camera (Carl Zeiss).

Although some 8-nitro-cGMP formed may leak out from cells during the immunocytochemical procedure, fixed cellular components on culture slides may retain an appreciable amount of 8-nitro-cGMP in the cells. This possibility was supported by the present observation that only a limited fraction of 8-nitro-cGMP was recovered from the cell homogenate during methanol extraction for LC-MS/MS analysis, possibly because a substantial amount of 8-nitro-cGMP remained in cell-associated precipitates during this extraction, as evidenced in the spike-and-recovery study for LC-MS/MS illustrated in supplemental Fig. S2.

Identification of 8-Nitro-cGMP Formed from Nitrated GTP via sGC

GTP (5 mm; Sigma) was reacted with 0.5 mm ONOO−, prepared from acidified nitrite and H2O2 by a quenched-flow method according to the literature (25), three times in 50 mm Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at room temperature under vortex mixing. The reaction mixture was then incubated in the presence of the purified sGC (200 nm) with 4 mm MnCl2 at 37 °C for 12 h (complete system). In some experiments, ONOO− treatment or sGC incubation was omitted from the complete reaction system. The reaction products were analyzed by the HPLC system, consisting of an LC-10ADVP pumping system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a TSKgel ODS-80Ts column (4.6 × 250 mm; Tosoh (Tokyo, Japan)). The mobile phase was 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid containing CH3CN. The CH3CN concentration was increased from 2 to 50% during 20 min in a linear gradient mode, after which it was maintained at 50% for an additional 10 min. The column temperature was 40 °C, and the flow rate was 0.7 ml/min. On-line UV spectra were obtained with an SPD-M10AVP photodiode array detector (Shimadzu). Elution of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP was monitored at 254 and 400 nm, respectively. Formation of 8-nitro-cGMP was further identified by means of MS: an Agilent 6510 ESI-Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) equipped with an HPLC chip (Zorbax 300SB-C18, Agilent Technologies). The HPLC chip source was coupled to an Agilent 1200 series HPLC system with two pumps. A microscale pump controlled sample loading through the trapping column, whereas a nanoscale pump controlled loading through the analytical column. Samples (1 μl) were loaded onto the trapping column with 0.1% formic acid at 4 μl/min. Afterward, the trapping column was placed in-line with the analytical column and was eluted with 0.1% formic acid containing 5% CH3CN at 400 nl/min. The HPLC chip system was on-line with an Agilent 6510 ESI-Q-TOF mass spectrometer operating in the positive-ion mode. The nanoelectrospray voltage was set to 1800 V, with a drying gas of 4 liters/min nitrogen at 300 °C. The fragmentor voltage was 150 V, and the skimmer voltage was 65 V. Data were analyzed by using Agilent MassHunter software.

Western Blotting

We performed Western blotting to assess expression levels of various proteins in cells. Cells, treated as described above, were solubilized with radioimmune precipitation buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors. Proteins in cell lysates were heat-denatured and separated via SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and were transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P, Millipore (Bedford, MA)). After membranes were blocked with TTBS (20 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.6) containing 5% skim milk (Difco), they were incubated with antibodies in TTBS containing 5% skim milk at 4 °C overnight. For analysis of protein S-guanylation, we used two rabbit anti-S-guanylated protein antibodies (i.e. 8-RS-cGMP and 8-RS-Guo antibodies) with different specificities and one monoclonal anti-S-guanylated (8-RS-cGMP) antibody, as described previously (10) and in the supplemental material. Other antibodies used in the Western blotting analysis were as follows: anti-Keap1 antibody (rat monoclonal) (16), anti-actin antibody (C-11, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA)), anti-iNOS antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma), anti-HO-1 antibody (Stressgen Bioreagents, Victoria, Canada), and anti-NQO1 (NAD(P)H dehydrogenase, quinone 1) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Membranes were washed in TTBS three times and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody at room temperature for 1 h. After three washes in TTBS, immunoreactive bands were detected by using a chemiluminescence reagent (ECL Plus Western blotting reagent; GE Healthcare) with a luminescent image analyzer (LAS-1000UVmini, Fujifilm (Tokyo, Japan)).

Analysis of Modification of Keap1 Cysteines

S-Guanylation of Keap1 was examined via Western blotting using anti-S-guanylated antibodies and MALDI-TOF-MS/MS analysis. Not only endogenous wild-type Keap1 but also overexpressed KEAP1 was analyzed for S-guanylation. Whole-cell lysates of C6 cells with or without LPS plus cytokine mixtures were subjected to Western blotting. In some experiments, Keap1 S-guanylation was investigated with C6 cells after knockdown of Keap1 with small interfering RNA (siRNA). Specifically, C6 cells were plated in 12-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 cells/well. Cells were transfected with Keap1 siRNA (100 pmol/well; Rn-Keap1–3; Qiagen (Hilden, Germany)) by using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX transfection reagent (Invitrogen). At 72 h after transfection, cells were harvested, but just before harvest they were treated with LPS plus cytokines for various time periods.

To identify formation of S-guanylated FLAG-KEAP1 overexpressed in C6 cells, we utilized immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG M2 antibody. Cell lysates prepared from FLAG-KEAP1-overexpressing cells, after treatment with SNAP, the LPS-cytokine mixture, or 8-nitro-cGMP, or without treatment, were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma) at 4 °C for 2 h. After samples were washed three times with washing buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.4), SDS loading buffer was added to the gel, and the gel suspension was boiled for 3 min to elute bound FLAG-KEAP1. S-Guanylation of FLAG-KEAP1 thus obtained was analyzed via Western blotting and MALDI-TOF-MS/MS.

Simultaneously, sulfhydryl oxidation of overexpressed KEAP1 was analyzed by the method reported earlier (20). This method can detect dithiothreitol (DTT)-sensitive sulfhydryl modifications, such as disulfide bridges, S-nitrosothiols, and sulfenic acid derivatives. C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 were treated with 100 μm SNAP for 12 h or were left untreated. For analysis of sulfhydryl oxidation, cells were lysed with lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.2% SDS, 0.1 mm neocuproine) containing 20 mm NEM to block unmodified sulfhydryl groups. Proteins were precipitated with acetone and redissolved in lysis buffer. Samples were incubated with 20 mm DTT for 30 min on ice to reduce modified sulfhydryls, and unreacted DTT was removed by gel filtration (PD MiniTrap G-25, GE Healthcare). Samples were then incubated with 50 μm N′-(3-maleimidylpropionyl)biocytin (Invitrogen) for 30 min on ice to label sulfhydryl groups, after which samples were subjected to gel filtration to remove unreacted N′-(3-maleimidylpropionyl)biocytin. After sulfhydryls in the samples were biotin-labeled, FLAG-KEAP1 was immunoprecipitated as described above and subjected to SDS-PAGE. After samples were blotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, N′-(3-maleimidylpropionyl)biocytin-labeled proteins were detected by using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated NeutrAvidin (Invitrogen). S-Nitrosylated human serum albumin (SNO-HSA) was subjected to this assay as a positive control. Some experiments were done without the DTT-reducing step to confirm that DTT-sensitive modifications were detected.

Similarly, S-nitrosylation of KEAP1 was analyzed by the method reported earlier (26). C6 cells treated with 100 μm SNAP for 12 h or 5 mm SNAP for 6 h or left untreated were lysed with radioimmune precipitation buffer containing 0.1 mm neocuproine and protease inhibitors. Cell lysates were incubated in HENS buffer (250 mm HEPES, pH 7.7, 1 mm EDTA, 0.1 mm neocuproine, 1% SDS) containing 20 mm S-methyl methanethiosulfonate (Sigma) at 50 °C for 20 min. Samples were precipitated with acetone, resuspended in HENS buffer with 1 mm N-[6-(biotinamido)hexyl]-3′-(2′-pyridyldithio)propionamide (Pierce) and 1 mm sodium ascorbate, and then incubated at room temperature for 90 min (biotin-labeling reaction). After S-nitrosylated residues were biotin-labeled, FLAG-KEAP1 was immunoprecipitated by using FLAG M2 antibody affinity gel (Sigma) and was eluted by boiling for 3 min in SDS loading buffer not containing DTT. Eluted FLAG-KEAP1 was subjected to SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions, followed by blotting with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated NeutrAvidin (Invitrogen). HSA and SNO-HSA were used as negative and positive controls in this assay, respectively.

MALDI-TOF-MS/MS Analysis for S-Guanylated Sites in KEAP1

Sites of S-guanylation in KEAP1 were identified by means of MALDI-TOF-MS/MS with trypsin-digested peptide fragments of KEAP1. For a positive S-guanylated KEAP1 control, recombinant mouse KEAP1 protein (6 μg) (15) was incubated with 0.5 mm 8-nitro-cGMP in 0.1 m ammonium bicarbonate in the presence of 8 m urea at room temperature for 14 h. KEAP1 protein that was S-guanylated in cells was prepared by treating C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 with 0.1 mm 8-nitro-cGMP for 12 h. FLAG-KEAP1 was then extracted from cell lysates (4 mg of protein) by using anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma), as described below. FLAG-KEAP1 was eluted by boiling the gel suspension with elution buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 0.1% SDS, 5 mm DTT, pH 8.0) for 3 min. The KEAP1 protein preparation was then reduced, alkylated, and trypsinized according to the literature (27). Peptide fragments containing S-guanylation sites were then extracted by using anti-S-guanylated protein affinity gel. The affinity gel was prepared by immobilizing mouse monoclonal anti-S-guanylated (8-RS-cGMP) antibody (supplemental material) on Protein A-Sepharose (GE Healthcare), as described earlier (10). KEAP1 trypsin digests were incubated with the anti-S-guanylated protein affinity gel at room temperature for 1 h. The gels were washed three times with PBS. S-Guanylated peptides were eluted from the gel with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid containing 50% CH3CN and were then concentrated in a vacuum centrifuge. Dried samples were dissolved in 20 μl of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid and were then desalted by using ZipTips C18 (Millipore), and peptides were mixed with matrix solution (10 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid in 50% CH3CN and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid) and were crystallized on target plates. MALDI-TOF and tandem TOF data were acquired in batch mode using the ABI4700 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The reflector in the positive ion mode with automated acquisition of 1000–4000 m/z was used with 2000 shots per spectrum. Precursor ions were subjected to MS/MS, in which a positive ion mode with a collision-induced dissociation cell and 1-kV collision energy were used, and 5000 shots were acquired per spectrum.

Analysis of the Downstream Effector Signaling Pathway of Nrf2

Activation of the transcriptional activity of Nrf2 was assessed by using Western blot analyses to identify the up-regulation of HO-1 and NQO1 in C6 cells after the use of various stimuli, as described above.

Also, nuclear translocation of Nrf2 was analyzed by Western blotting using the nuclear fraction. Cells were transfected with p3×FLAG-CMV-KEAP1 to overexpress FLAG-KEAP1 and were harvested 36 h after transfection. Just before harvesting, 8-nitro-cGMP (100 μm) or SNAP (50 μm) treatments were performed for various time periods. Nuclear fractions were prepared by using the NE-PER nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction reagent kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and they were subjected to Western blotting using anti-Nrf2 antibody (H-300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). Anti-lamin B antibody (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) was used to check protein loading.

To further clarify the antioxidant response caused by Nrf2 activation, the effect of 8-nitro-cGMP on H2O2-induced cell death was examined. Cells were plated at a density of 3 × 104 cells/well in 96-well plates. Cells were treated with various concentrations of 8-nitro-cGMP for 24 h, and then they were treated with 400 μm H2O2 for 30 min to induce cell death. After H2O2 treatment, cells were incubated in medium without H2O2 for 4 h. Cell viability was determined by using the MTT method (28).

Measurement of ROS Generated in C6 Cells Treated with SNAP

Not only NO but also ROS generation is required for effective guanine nitration. We thus analyzed possible ROS formation in C6 cells after stimulation with SNAP by use of a mitochondria-specific ROS fluorescent probe, MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen). Briefly, after C6 cells were treated with various concentrations of SNAP for different time periods, they were washed with Hanks buffer (0.137 m NaCl, 5.4 mm KCl, 0.25 mm Na2HPO4, 0.44 mm KH2PO4, 1.3 mm CaCl2, 1.0 mm MgSO4, 4.2 mm NaHCO3) and were stained with 4 μm MitoSOX Red, followed by fluorometric analysis, as described previously (10, 29).

Statistical Analysis

All data are shown as means ± S.E. Statistical significance between two groups was determined by means of a two-tailed unpaired Student's t test.

RESULTS

NO-dependent Formation of 8-Nitro-cGMP in Cells

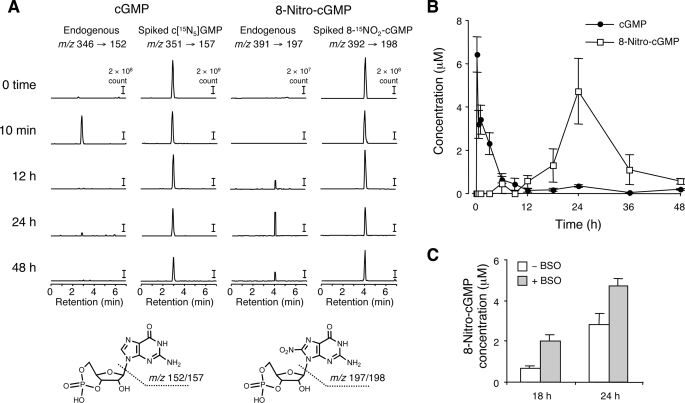

To elucidate the roles of 8-nitro-cGMP in the downstream signal transduction of NO, we first examined the formation of 8-nitro-cGMP in C6 cells in response to NO. We identified and quantified 8-nitro-cGMP by means of LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis. Formation of 8-nitro-cGMP is induced by exogenous and endogenous NO. In the present investigation, we successfully carried out a precise quantitative analysis via a spike-and-recovery study using stable isotope-labeled nucleotides. Specifically, as Fig. 1 illustrates, an appreciable amount of 8-nitro-cGMP was produced in the cells after treatment with SNAP. We also examined the change in cGMP levels according to time. It is notable that 8-nitro-cGMP production was sustained, in contrast with the quick decline in cGMP. cGMP concentration showed a rapid and transient elevation and a peak within a few h after SNAP treatment (Fig. 1), whereas 8-nitro-cGMP concentration gradually increased and reached a peak at 24 h after 50 μm SNAP treatment and declined thereafter. The important finding here is that, despite the apparent difference in time profiles of intracellular formation of the two compounds, 8-nitro-cGMP (even when treated with BSO) showed a peak value that was comparable with or higher than that of cGMP, an original second messenger molecule derived from the NO-sGC pathway (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S3). Also, the fact that BSO treatment led to an enhanced 8-nitro-cGMP formation suggests that GSH may somehow affect the stability of 8-nitro-cGMP formed in the cells. However, it should be also emphasized that an appreciable amount of 8-nitro-cGMP was still generated in the presence of GSH without BSO treatment as a result of the physiological concentration of NO as produced by SNAP. Relatively low concentrations of SNAP were sufficient to induce formation of micromolar concentrations of 8-nitro-cGMP, as shown in supplemental Fig. S3, which indicates effective guanine nitration and thus 8-nitro-cGMP production after SNAP treatment of cells.

FIGURE 1.

Quantitative LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis for measurement of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP formed in C6 cells treated with SNAP. Cells were treated with 50 μm SNAP for various times in the presence or absence of 1 mm BSO, and cell extracts were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, representative LC-ESI-MS/MS chromatograms of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP at each time point in cells treated with SNAP in the presence of BSO. B, time profiles of 8-nitro-cGMP and cGMP concentrations in SNAP-treated cells in the presence of BSO. C, the effect of BSO on intracellular concentrations of 8-nitro-cGMP after SNAP treatment. Data represent means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3).

8-Nitro-cGMP formation was investigated not only by means of LC-ESI-MS/MS but also via HPLC-ECD. Both methods showed a consistent time course of 8-nitro-cGMP accumulation in cells treated with SNAP (supplemental Fig. S4). To ensure the validity of the present LC-MS/MS analyses combined with the spike-and-recovery study, we compared cGMP and GTP contents by using different methods (or previous determinations). For example, the cGMP content quantified in C6 cells stimulated with SNAP via a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (cGMP-EIA Biotrak System, GE Healthcare) was almost the same as that found by using LC-MS/MS, as mentioned above (data not shown). Also, the GTP contents of C6 cells measured by LC-MS/MS did not change appreciably with or without SNAP and LPS-cytokine treatments (709.1 ± 175.6 μm), and in fact they were consistent with values reported earlier (30).

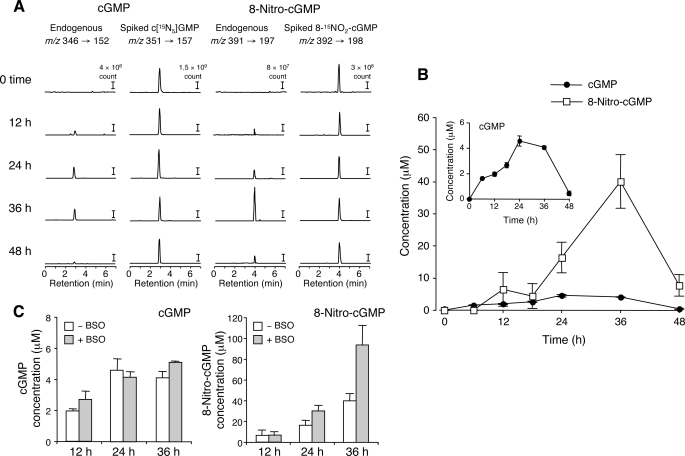

As in the case for SNAP-treated cells, C6 cells after stimulation with LPS and cytokines (IFN-γ, TNFα, and IL-1β) to induce iNOS and endogenous NO production generated a significant amount of 8-nitro-cGMP, as unequivocally identified by LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis (Fig. 2 and supplemental Fig. S5). Levels of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP began to rise after iNOS expression, and NO production became obvious at 6–12 h after the start of LPS plus cytokine treatment (supplemental Fig. S5). Although the time profile of 8-nitro-cGMP formation seemed to follow cGMP formation by a few h, the peak value of 8-nitro-cGMP concentration in iNOS-expressing cells was higher than that of cGMP (Fig. 2). The highest concentration of 8-nitro-cGMP generated in activated cells was 40 μm (without BSO) and was much higher than that in SNAP-treated cells. Also, higher levels of 8-nitro-cGMP were obtained in these iNOS-expressing cells throughout the course of stimulation compared with cells treated with SNAP. BSO had a similar effect on these LPS plus cytokine-treated cells; however, the magnitude of enhancement was not as marked. C6 cells are known to express Nox2 (NADPH oxidase 2), which may be activated by our LPS plus cytokine stimulation (31). These results may thus indicate that NO and ROS, if synchronously generated by these cells, can quite effectively produce 8-nitro-cGMP.

FIGURE 2.

LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis for measurement of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP formed in C6 cells stimulated with LPS plus cytokines. Cells were stimulated with a mixture of LPS (10 μg/ml), IFN-γ (200 units/ml), TNFα (500 units/ml), and IL-1β (10 ng/ml) for various time periods in the absence or presence of 1 mm BSO, and cell extracts were prepared as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, representative LC-ESI-MS/MS chromatograms of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP for activated cells without BSO. B, time profiles of intracellular 8-nitro-cGMP and cGMP concentrations after stimulation with LPS plus cytokines without BSO determined with LC-MS/MS. The inset highlights the profile of cGMP formation. C, the effect of BSO on intracellular concentrations of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP after LPS plus cytokine treatment. Data represent means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3).

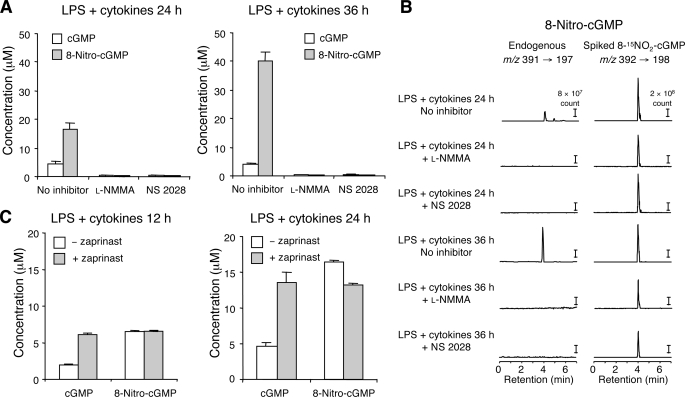

Furthermore, to see whether sGC is involved in 8-nitro-cGMP formation, 8-nitro-cGMP production was examined with cells treated or untreated with an sGC inhibitor, NS 2028. As Fig. 3 shows, not only cGMP but also 8-nitro-cGMP LC-MS/MS peaks were nullified by NS 2028 treatment in cells activated with LPS plus cytokines, which indicated that 8-nitro-cGMP was derived either via cGMP to be directly nitrated or from nitrated guanine nucleotides (e.g. 8-nitro-GTP) as a substrate for sGC, which catalyzed transformation of the triphosphate into the cyclic nucleotide. NOS inhibition by l-NMMA also suppressed 8-nitro-cGMP, but the PDE inhibitor zaprinast did not affect its formation. These results thus clearly suggest that cellular 8-nitro-cGMP formation depends solely on NO and sGC activity but that 8-nitro-cGMP may not originate directly from cGMP.

FIGURE 3.

Effect of various inhibitors of NOS, sGC, and PDE on cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP formation in C6 cells. Cells were stimulated with a mixture of LPS (10 μg/ml), IFN-γ (200 units/ml), TNFα (500 units/ml), and IL-1β (10 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of various inhibitors for various time periods, followed by quantification of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP formed in cells via LC-ESI-MS/MS, as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, cells were treated with 10 mm l-NMMA or 10 μm NS 2028, beginning 1 h before the addition of LPS and cytokines and stimulation with this mixture for 24 and 36 h, followed by measurement of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP. B, representative LC-ESI-MS/MS chromatograms for cells having various inhibitor treatments shown in A. C, the same activated cells were also treated with 0.1 mm zaprinast for 12 and 24 h, starting 1 h before stimulation began, and cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP were then quantified. Data represent means ± S.E. (error bars) (n = 3).

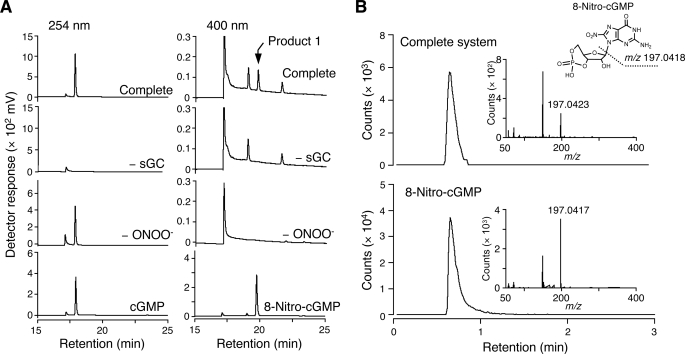

Our present preliminary experiments provide further evidence for these suggestions (Fig. 4). Treatment of GTP with ONOO− in a cell-free reaction mixture, followed by the addition of sGC, led to formation of a significant amount of 8-nitro-cGMP (product 1; Fig. 4A) in a manner dependent on the catalytic activity of sGC. It is also important that the ratio of 8-nitro-cGMP formation was almost 1% on the basis of GTP concentration. Because this efficacy of 8-nitro-cGMP was almost the same as that of nitration of GTP by ONOO− under the present experimental conditions, this highly efficient 8-nitro-cGMP formation may mean that nitrated GTP may behave as an excellent substrate for sGC even in the presence of excessive GTP.

FIGURE 4.

8-Nitro-cGMP generation via sGC from the reaction mixture of GTP and ONOO−. A, HPLC-UV analysis. In the complete system (Complete), GTP (5 mm) was reacted three times with ONOO− (0.5 mm), followed by incubation with sGC (200 nm). −sGC, the same setup as for complete but without sGC incubation; −ONOO−, complete but without ONOO− treatment; cGMP, cGMP standard (100 μm); 8-nitro-cGMP, 8-nitro-cGMP standard (100 μm). Product 1 showed a retention time identical to that of 8-nitro-cGMP standard. Top, mass chromatogram of product 1 monitored at 391.04. B, HPLC-MS analysis. Extracted ion chromatogram of m/z 391.04 ± 0.03 observed with the reaction mixture of complete system (top) and with authentic 8-nitro-cGMP (10 μm) (bottom). The insets show product ion mass spectrum of a molecular ion at m/z 391.04, eluted between 0.6 and 0.8 min.

Immunocytochemistry utilizing the 1G6 monoclonal antibody indicated that immunostaining for 8-nitro-cGMP increased markedly in C6 cells after treatment with the NO donor SNAP (supplemental Fig. S6, A and B). This increase was further enhanced by BSO, consistent with the above LC-MS/MS analyses. Similarly, 8-nitro-cGMP immunostaining markedly increased in C6 cells expressing increased amounts of iNOS after stimulation with LPS plus a mixture of the proinflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, TNFα, and IL-1β (supplemental Fig. S6C). Treatment of cells with l-NMMA and NS 2028, but not with zaprinast, almost completely nullified this elevated 8-nitro-cGMP immunoreactivity (supplemental Fig. S6C) (data not shown), also consistent with the LC-MS/MS analysis just mentioned. These multiple lines of evidence thus demonstrate that formation of 8-nitro-cGMP depends on NO production in the cells.

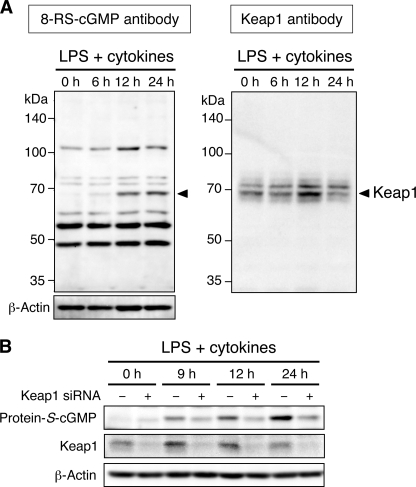

S-Guanylation of Keap1

We then analyzed 8-nitro-cGMP-induced protein S-guanylation in C6 cells treated with LPS plus cytokines (Fig. 5). Several bands were observed in the immunoblot after use of anti-S-guanylated protein (8-RS-cGMP) antibody, depending on treatment time (Fig. 5A, left), which indicated that specific proteins were prone to be S-guanylated. In particular, the intensity of a 70 kDa band dramatically increased after 12 h of LPS plus cytokine treatment (Fig. 5A, arrowhead). In our previous study, we found that the redox sensor protein Keap1 was highly susceptible to S-guanylation induced by 8-nitro-cGMP in an in vitro cell-free system (10). Inasmuch as the molecular size of Keap1 is ∼70 kDa (Fig. 5A, right), we suspected that the 70 kDa band corresponded to Keap1. To verify this conjecture, we used siRNA to knock down Keap1 expression and evaluated changes in band intensity. Band intensity after treatment with LPS plus cytokines was markedly decreased by Keap1 siRNA (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Protein S-guanylation in C6 cells treated with LPS plus cytokines. A, cells were stimulated with a mixture of LPS (10 μg/ml), IFN-γ (100 units/ml), TNFα (100 units/ml), and IL-1β (10 ng/ml). Cell lysates (10 μg of protein) were analyzed by using Western blotting with anti-S-guanylated protein (8-RS-cGMP) antibody (left) and anti-Keap1 antibody (right). The 70-kDa protein (arrowhead in the left panel), detectable only after treatment with LPS plus cytokines, showed electrophoretic mobility identical to that of Keap1 (arrowhead in the right panel). B, cells without or with transfection with Keap1 siRNA were stimulated with LPS plus cytokines as in A. Protein S-guanylation and Keap1 expression were analyzed by Western blotting.

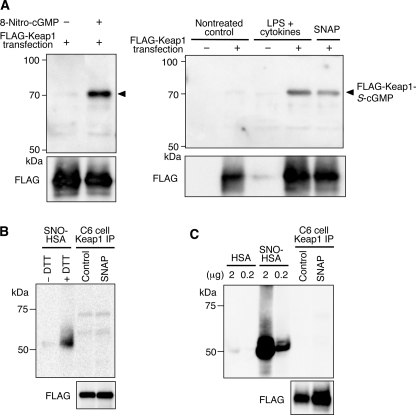

We also used immunoprecipitation to investigate S-guanylation of Keap1 in C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1, with subsequent immunoblot analysis using anti-S-guanylated protein (8-RS-cGMP) antibody (Fig. 6A). We found that S-guanylated KEAP1 was clearly pulled down by the anti-FLAG antibody from cells treated with 8-nitro-cGMP but not from cells without such treatment (Fig. 6A, left). Similarly, treatment of C6 cells with SNAP or LPS plus cytokines markedly increased S-guanylation of KEAP1 (Fig. 6A, right). We then evaluated how much KEAP1 expressed by C6 cells is S-guanylated by exogenous and endogenous 8-nitro-cGMP formed in the cells. In fact, appreciable levels (10–20%) of KEAP1 cysteine residues were found to be S-guanylated in cells forming 8-nitro-cGMP (supplemental Fig. S7). For this evaluation of KEAP1 S-guanylation, we chose the 12 h time point, when 8-nitro-cGMP began to increase in cells after stimulation with SNAP or LPS plus cytokines (Figs. 1 and 2). The reason why we used this relatively early time is that we previously observed that Keap1 seemed to decay and become unstable and less detectable by Western blotting at later times during treatment with LPS and cytokines (10) (data not shown). Therefore, the possibility exists that a much higher fraction of Keap1 was actually affected by S-guanylation after 12 h, when LC-MS/MS analysis showed peak values for 8-nitro-cGMP. However, these results do demonstrate that Keap1 is a major S-guanylated protein in NO-producing C6 cells.

FIGURE 6.

S-Guanylation and other sulfhydryl modifications of FLAG-KEAP1 isolated from C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1. A, FLAG-KEAP1 was transiently overexpressed in cells with a plasmid expression vector, and cells were treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (100 μm; left), LPS (10 μg/ml) plus cytokines (100 units/ml IFN-γ, 100 units/ml TNFα, and 10 ng/ml IL1-β) (right), or SNAP (50 μm; right) for 12 h. FLAG-KEAP1 was isolated from cell lysates (200 μg of protein) with FLAG M2 antibody affinity gel and was used in Western blotting analyses with anti-S-guanylated protein (8-RS-cGMP) antibody. The intensity of bands in the left and right panels was adjusted on the basis of the signal intensity of the S-guanylated protein standard (α1-protease inhibitor reacting with 8-nitro-cGMP in vitro) in each blotted membrane. The arrowheads indicate S-guanylated FLAG-KEAP1. B, oxidative modifications of KEAP1 cysteines. Lysates (200 μg of protein), prepared from C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 treated with 100 μm SNAP for 12 h (SNAP) or not treated (Control), were used for immunoprecipitation analysis (C6 cell Keap1 IP). SNO-HSA (0.2 μg) was subjected to this analysis as a positive control (+DTT). SNO-HSA was also analyzed without the reducing step by DTT (−DTT), to examine DTT-sensitive modifications. C, S-nitrosylation of FLAG-KEAP1. Lysates (200 μg of protein), prepared from C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 treated with 100 μm SNAP for 12 h or not treated, were subjected to immunoprecipitation analysis for S-nitrosylation. HSA (2 μg and 0.2 μg) and SNO-HSA (2 μg and 0.2 μg) were used as negative and positive controls, respectively. FLAG-KEAP1 detected with FLAG M2 antibody appears at the bottom (FLAG).

The possibility remained that Keap1 cysteine residues may be subjected to other modifications upon exposure to NO. To address this possibility, we analyzed sulfhydryl modifications of KEAP1 cysteine residues in cells treated with SNAP (Fig. 6, B and C, and supplemental Fig. S8). We specifically examined sulfhydryl oxidation and S-nitrosylation of KEAP1 via established methods (20, 26). We did not find any bands in samples pulled down by the anti-FLAG antibody in both experiments. However, positive control samples using SNO-HSA showed intense bands. No significant S-nitrosylation was observed with KEAP1 even under strong S-nitrosylating conditions with 5 mm SNAP, when many cellular proteins other than KEAP1 were extensively modified (see supplemental Fig. S8). These results indicate that Keap1 may be primarily subjected to S-guanylation, but not to sulfhydryl oxidation or S-nitrosylation, upon exposure to NO.

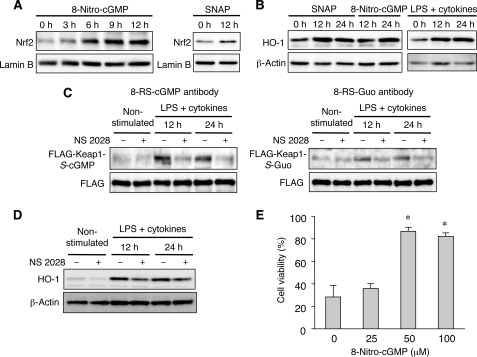

Nrf2 Activation by S-Guanylated Keap1 and Effects on Downstream Signaling

Because modification of certain cysteine residues in Keap1 reportedly inactivates ubiquitin ligase activity of Keap1 and results in stabilization of Nrf2, we anticipated that S-guanylation of Keap1 would also lead to activation of Nrf2 and cytoprotective gene expression. We therefore assessed the effect of 8-nitro-cGMP on nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 in C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1. We found that 8-nitro-cGMP treatment greatly increased the nuclear Nrf2 level (Fig. 7A, left). Exogenous NO derived from SNAP added to the cell culture also increased the nuclear Nrf2 level (Fig. 7A, right). These findings are consistent with the marked KEAP1 S-guanylation that was detected in C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 upon exposure to SNAP.

FIGURE 7.

Activation of Nrf2 and cytoprotective gene expression associated with 8-nitro-cGMP formation. A, nuclear translocation of Nrf2. C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 were treated with 8-nitro-cGMP (100 μm; left) or SNAP (50 μm; right) for the indicated time periods, and nuclear fractions were prepared. Nrf2 in nuclear fractions (10 μg of protein) was analyzed by Western blotting. B, Nrf2-regulated HO-1 expression. C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 were treated with SNAP, 8-nitro-cGMP, or LPS plus cytokines for the indicated time periods as described in Fig. 6, and cell lysates were prepared. Expression of HO-1 was analyzed by Western blotting. C, the effect of the sGC inhibitor NS 2028 on S-guanylation of KEAP1 of cells treated with LPS and cytokines, as analyzed by Western blotting with the use of two different S-guanylated antibodies (i.e. 8-RS-cGMP and 8-RS-Guo antibody) (see “Supplemental Methods” and supplemental Fig. S9 for details). C6 cells with or without LPS-cytokine stimulation were treated with 10 μm NS 2028 as described in the legend to Fig. 3, and FLAG-KEAP1 isolated from cell lysates was subjected to this S-guanylation analysis. D, the effect of NS 2028 on HO-1 expression. The same cells as those used in C were studied for HO-1 expression via Western blotting. E, 8-nitro-cGMP-associated cytoprotection against H2O2-induced cell death. C6 cells were treated with various concentrations of 8-nitro-cGMP for 24 h and were then exposed to 400 μm H2O2 for 30 min. Four hours after H2O2 exposure, cell death was analyzed by means of the MTT assay. Data represent means ± S.E. (n = 3). *, p < 0.01 versus cells not treated with 8-nitro-cGMP.

Nrf2 is known to regulate the expression of genes involved in the adaptive response to oxidative stress (12). To elucidate whether the increased nuclear Nrf2 would contribute to the expression of Nrf2 target genes, we investigated the expression of HO-1, one of these Nrf2 target downstream effector molecules. Immunoblot analysis revealed that 8-nitro-cGMP treatment of cells enhanced HO-1 expression (Fig. 7B). Similar induction of HO-1 was observed in cells treated with SNAP or with LPS plus cytokines (Fig. 7B). Other downstream enzymes, such as NQO1, were also up-regulated by endogenous and exogenously administered NO and 8-nitro-cGMP (data not shown).

Most important, as demonstrated in Fig. 7, C and D, Western blotting indicated that S-guanylation of KEAP1 was inhibited via suppression of 8-nitro-cGMP formation by the sGC inhibitor NS 2028, which totally nullified 8-nitro-cGMP formation in the same cells as those described above (Fig. 3). It is intriguing that suppression of KEAP1 S-guanylation was evident not only with the anti-S-guanylated (8-RS-cGMP) antibody, which can specifically recognize the whole cGMP structure of the S-guanylated adducts, but also with another anti-S-guanylated (8-RS-Guo) antibody, which recognizes only the guanosine moiety of the S-guanylated structure and thus has a rather broad spectrum of activity for almost all guanosine-containing derivatives (e.g. cGMP, GMP, GDP, and GTP) (supplemental Fig. S9 and Fig. 7C). In other words, these Western blotting data indicate that the KEAP1 S-guanylation structure identified by blotting analysis derives primarily from the RS-cGMP adducts. Furthermore, HO-1 expression was also appreciably reduced by the same NS 2028 treatment (Fig. 7D), which suggests again that, at least in part, S-guanylation of Keap1 indeed contributed to activation of the downstream signaling pathway involving Nrf2 transcriptional activation.

We then determined whether 8-nitro-cGMP possesses a cytoprotective function through nuclear accumulation of Nrf2. Because Nrf2 has been shown to regulate antioxidant enzyme expression, we examined the effect of 8-nitro-cGMP on H2O2-induced cell death (Fig. 7E). Pretreatment of C6 cells with 8-nitro-cGMP significantly increased cell viability after exposure to H2O2. This cytoprotective effect can be weakened by a specific inhibitor of HO-1 and HO-1 siRNA (data not shown), which suggests that HO-1 is an important target of Nrf2 for its antioxidant activity.

Activation of Keap1-Nrf2 signaling was observed with 8-nitro-cGMP but not with cGMP itself. We also found that unnitrated parental cGMP had no effects in terms of activation of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Because cGMP per se is ineffective as a pharmacological agent as a result of its rapid degradation by PDEs, we examined the effect of its PDE-resistant and membrane-permeable analogue, 8-bromo-cGMP, on Keap1-Nrf2 signaling and HO-1 expression. No apparent activating effect was observed, at least with physiological concentrations in C6 cells. A similar lack of such signaling functions of 8-bromo-cGMP for other types of cells (e.g. mouse peritoneal macrophages and RAW 264 and HepG2 cells) was reported elsewhere (11) (data not shown).

These results thus indicate that 8-nitro-cGMP induces S-guanylation of Keap1 and nuclear translocation of Nrf2. Nrf2 activated the antioxidant genes and protected cells from the cytotoxic effect of H2O2. On the basis of these observations, we concluded that the cytoprotective effect of NO is attributable, at least in part, to S-guanylation of Keap1 and activation of the Nrf2 pathway.

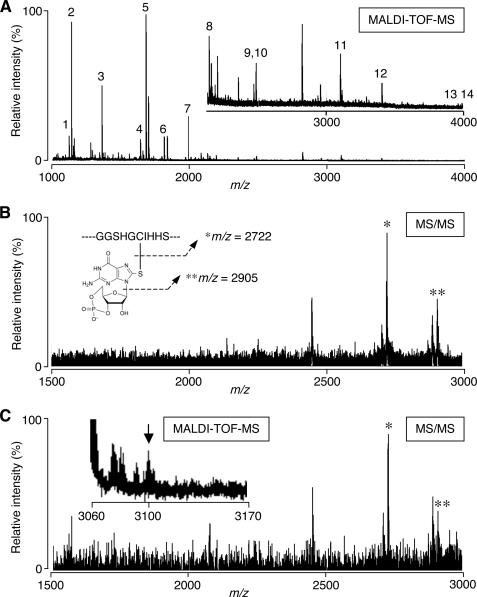

Identification of the Cys434 Residue Responsible for S-Guanylation

We recently proposed that each electrophile attacks a certain combination of cysteine residues of Keap1, and we defined this profile as a cysteine code (23). We suspected that 8-nitro-cGMP, acting as an electrophile, also shows a specific preference for certain Keap1 cysteine residues. To identify the cysteine residues responsible for S-guanylation by 8-nitro-cGMP, we determined the cysteine residues of Keap1 that were specifically modified by the cGMP moiety. Recombinant KEAP1 was first reacted with 8-nitro-cGMP in vitro in a cell-free system. KEAP1 was then alkylated and digested with trypsin. The resultant peptides containing S-guanylated cysteine residues were purified on the anti-S-guanylated protein antibody column, and these peptides were analyzed by using MALDI-TOF-MS/MS. We found that 18 of 25 cysteine residues in the KEAP1 molecule were S-guanylated (Fig. 8A and Table 2). In this MS/MS analysis, two fragment ions were typically detected in S-guanylated peptides after ionization (Fig. 8B), and this feature allowed us to detect specific S-guanylated peptides.

FIGURE 8.

MALDI-TOF-MS/MS analysis of S-guanylated cysteine residues in KEAP1. A, identification of S-guanylated cysteine in 8-nitro-cGMP-treated recombinant KEAP1. Recombinant KEAP1 protein was incubated with 0.5 mm 8-nitro-cGMP at room temperature for 14 h. KEAP1 peptide fragments containing S-guanylated cysteine that were enriched by using anti-S-guanylated protein affinity gel were subjected to MALDI-TOF-MS. Numbered peaks (1–14) indicate trypsin-digested peptides of KEAP1 containing S-guanylated cysteine, as estimated via molecular mass. Table 2 shows the sequences of each KEAP1 peptide. The inset in A shows 10-fold magnification of the relative intensity (y axis) for the corresponding mass range. B, identification of S-guanylation of Cys434 in 8-nitro-cGMP-treated recombinant KEAP1. The precursor ion of peak 11 (m/z 3099.67) in A was subjected to MS/MS. Theoretical fragmentation ions are illustrated in the inset in B, and corresponding peaks are shown with asterisks. C, identification of S-guanylated KEAP1 (Cys434) formed in cells treated with 8-nitro-cGMP. C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 were treated with 0.1 mm 8-nitro-cGMP for 12 h. FLAG-KEAP1 isolated from cells using FLAG M2 antibody-agarose gel was processed as in A to obtain S-guanylated peptides. MALDI-TOF-MS analysis (inset) identified the peptide corresponding to S-guanylated FLAG-KEAP1 peptide containing Cys434 (m/z 3099.32, arrow in inset). MS/MS analysis revealed that this peptide gave two peaks (asterisks) of fragmentation ion derived from Cys434-containing peptide, consistent with the data shown in B. Other molecular mass regions of the MS profile contained no S-guanylated peptide derived from FLAG-KEAP1 of 8-nitro-cGMP-treated cells.

TABLE 2.

Peptides containing S-guanylated cysteine residues in 8-nitro-cGMP-treated recombinant mouse KEAP1 detected by MALDI-TOF MS analysis

| Peak no.a | Molecular mass (m/z) | Amino acid sequenceb | Position of Cys residuec |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1124.44 | YDCPQR | 257 |

| 2 | 1140.51 | CHALTPR | 273 |

| 3 | 1361.64 | CEILQADAR | 288 |

| 4 | 1648.40 | SGVGVAVTMEPCR | 613 |

| 5 | 1687.76 | LNSAECYYPER | 489 |

| 6 | 1818.00 | LSQQLCDVTLQVK | 77 |

| 7 | 1992.08 | SGLAGCVVGGLLYAVGGR | 368 |

| 8 | 2131.94 | CPEGAGDAVMYASTECK | 23, 38 |

| 9 | 2478.00 | CVLHVMNGAVMYQIDSVVR | 151 |

| 10 | 2480.00 | QEEFFNLSHCQLATLISR | 226 |

| 11 | 3099.67 | IGVGVIDGHIYAVGGSHGCIHHSSVER | 434 |

| 12 | 3396.69 | SGAGVCVLHNCIYAAGGYDGQDQLNSVER | 513, 518 |

| 13 | 3960.90 | NNSPDGNTDSSALDCYNPMTNQWSPCASMSVPR | 395, 406 |

| 14 | 3990.16 | ACSDFLVQQLDPSNAIGIANFAEQIGCTELHQR | 171, 196 |

a Numbers correspond to the peaks indicated in Fig. 8A.

b The S-guanylated cysteine residues are underlined.

c Positions are amino acid numbers in mouse KEAP1 counted from the N terminus.

We then performed similar experiments with C6 cells overexpressing FLAG-KEAP1 after 8-nitro-cGMP treatment. We identified S-guanylation only at the Cys434 residue, as evidenced by MS/MS analysis (Fig. 8C). The present study thus demonstrated that one specific cysteine residue, Cys434, is selectively S-guanylated in vivo in cells in culture. This selective S-guanylation seems to inactivate the ubiquitin ligase activity of the Keap1 E3 ligase complex and results in stabilization and accumulation of Nrf2.

DISCUSSION

Chemical nitration of biological molecules by NO-derived RNOS, such as ONOO− and NO2, has been well documented (3–5). Of the various nitrated compounds identified to date, 8-nitro-cGMP has several unique features (10, 11, 32). Our current study revealed that 8-nitro-cGMP activates Nrf2 through S-guanylation of Keap1, and thereby antioxidant and cytoprotective enzyme genes are activated in cultured C6 cells. It should be also emphasized here that formation of a large amount of 8-nitro-cGMP, in a manner depending on NO formed endogenously in the cells or induced exogenously, was unambiguously verified via our LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis utilizing a spike-and-recovery study with stable isotope-labeled nucleotide derivatives.

We used C6 cells for the present analyses because they express relatively high levels of sGC, which is the sole enzyme responsible for effective cGMP formation after stimulation with NO. Also, C6 cells are easily activated by proinflammatory cytokines to express iNOS. In fact, C6 cells readily respond to stimulation with NO and produce an appreciable quantity of cGMP, as shown by LC-MS/MS (Figs. 1–3). In addition, the time course of intracellular cGMP formation was typical, in that formation increased quickly after stimulation with exogenous NO derived from SNAP and then declined to insignificant levels within a few hours. For the time profile of 8-nitro-cGMP in SNAP-treated cells, a great gap occurred for cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP production, in that 8-nitro-cGMP formation increased gradually several h after the peak of cGMP and reached a maximum level at 24 h after SNAP treatment started. Another point is that the peak level of 8-nitro-cGMP tended to be greater than that of cGMP. In addition, although the time profiles for cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP production in iNOS-expressing cells appeared somewhat different from those in SNAP-treated cells, some delay still occurred between the peaks, and much higher values were obtained for 8-nitro-cGMP compared with cGMP from cells activated to generate endogenous NO. This feature of the profiles of 8-nitro-cGMP formation, and especially the higher yield of 8-nitro-cGMP compared with the yield of cGMP, may exclude the possibility that cGMP is chemically nitrated and transformed into 8-nitro-cGMP when we consider the efficacy of a chemical nitration reaction (e.g. that induced by RNOS). Alternative mechanisms of this considerably effective intracellular 8-nitro-cGMP formation may therefore occur. Although in vivo mechanisms of 8-nitro-cGMP formation are not yet clear, NO-dependent guanine nitration mediated through RNOS must be involved in 8-nitro-cGMP formation within cells (10). The difference in time profiles of cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP formation may be explained by the chemical nature of 8-nitro-cGMP, inasmuch as this compound resists degradation by PDEs (10). Also, guanine nitration may be taking place primarily on the guanine moieties of nucleotides other than cGMP (e.g. GMP, GDP, and GTP). This may be just one feasible model for nitrated nucleotide-mediated electrophilic signaling occurring in vivo, which we are now eagerly pursing in our laboratories. In fact, our preliminary data revealed a unique pathway contributing to intracellular formation of 8-nitro-cGMP, which may be synthesized via sGC from 8-nitro-GTP, derived via GTP nitration by RNOS, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Moreover, because cGMP (e.g. 8-bromo-cGMP) lacks the potential to activate Keap1-Nrf2 and cGMP and 8-nitro-cGMP have quite different time profiles of production in cells, we may have an important conclusion here, that 8-nitro-cGMP and cGMP may have distinct roles in NO signal transduction.

The present work clarified another intriguing finding, which strongly supports the profound biological relevance of 8-nitro-cGMP formed in cells. As discussed above, the exact quantity of 8-nitro-cGMP formed was herein extensively evaluated and precisely determined. That such a considerable amount was sustained in cells may not be consistent with the electrophilic nature of 8-nitro-cGMP, because electrophilic compounds are generally thought to react readily and thus be degraded with sulfhydryls. In particular, 8-nitro-cGMP undergoes, during its reaction with sulfhydryls, denitration to release its nitro moiety, so that it in turns loses its unique electrophilicity. However, we are aware that 8-nitro-cGMP, compared with other biological electrophiles, is inert in terms of its electrophilicity. For example, the reaction rate constant for 8-nitro-cGMP and GSH is orders of magnitude lower than the rate constants of most fatty acid-derived electrophiles (33). This fact appears to agree well with the present finding that BSO treatment did not greatly enhance 8-nitro-cGMP generation in both SNAP- and LPS-cytokine-treated cells. Another interesting aspect of this significant 8-nitro-cGMP formation is that, even in the absence of BSO, SNAP as an NO donor alone could stimulate formation of an appreciable level of 8-nitro-cGMP. For effective nitration of guanine, not only NO but also ROS are required to generate RNOS. We therefore examined ROS formation in mitochondria of C6 cells with the use of a fluorescence probe for mitochondrial ROS. Although this assessment is semiquantitative, we clearly observed that SNAP could indeed generate ROS from mitochondria, as shown in supplemental Fig. S10. In fact, NO-induced ROS generation in cultured cells was recently reported (34). It is therefore reasonable that SNAP triggered RNOS formation by indirectly generating ROS, which led to efficient 8-nitro-cGMP formation in the cells. Effective RNOS formation related to 8-nitro-cGMP was achieved with C6 cells activated by LPS and cytokines, which can induce iNOS (supplemental Fig. S5) and may activate Nox2, as discussed above.

Our study also found that NO-dependent 8-nitro-cGMP production can induce such a cytoprotective response through activation of the Keap1-Nrf2 regulatory system. Although we suggested earlier that 8-nitro-cGMP may have some significant regulatory function in the Keap1-Nrf2 transcriptional pathway (10, 11), the molecular mechanism of Keap1-Nrf2 activation induced by 8-nitro-cGMP remains unclear. In this context, one of the most important findings of our study is that 8-nitro-cGMP-induced S-guanylation of Keap1 occurs at a specific cysteine residue, Cys434. It is intriguing that Cys434 is located near the Nrf2-binding region of Keap1 (see below). These results thus suggest that 8-nitro-cGMP is involved in the major signaling pathway for cytoprotection and adaptive responses to RNOS and ROS through targeting of Keap1 Cys434, which results in impaired Keap1-Nrf2 interaction.

Protein S-guanylation is a unique post-translational modification. We recently found that protein S-guanylation is caused by 8-nitroguanosine derivatives in general (10, 11, 32). To investigate the roles of protein S-guanylation in cell signaling, we examined the general profiles of S-guanylated proteins. We found that Keap1 is the major target S-guanylated by NO exposure, and its S-guanylated structure primarily derives from RS-cGMP adducts. Other chemical modifications, such as sulfhydryl oxidation and S-nitrosylation, that are often caused by NO and ROS were not observed in Keap1 cysteine residues in SNAP-treated cells, which indicates that Keap1 may play a predominant role in the NO signaling pathway via 8-nitro-cGMP.

In our MALDI-TOF-MS/MS analyses of S-guanylated cysteine residues in KEAP1, protein S-guanylation was identified only at Cys434 of KEAP1 isolated from 8-nitro-cGMP-treated cells. In recombinant KEAP1 reacted with 8-nitro-cGMP in an in vitro cell-free system, however, 18 of 25 total cysteine residues were S-guanylated, so that Cys434 S-guanylation was not dominant. It is therefore conceivable that the Cys434 of Keap1 may have a structural characteristic that under physiological conditions enables only its specific S-guanylation rather than S-guanylation of many cysteine residues of Keap1. Although a number of studies have examined Keap1-electrophile adducts generated in vitro in the presence of high concentrations of electrophilic reagents (17–21), to our best knowledge, we provide here the first biochemical identification (by MS analyses) of significant Keap1 cysteine modification with an endogenous electrophilic signaling molecule.

We previously described the in vivo significance of Cys151, Cys273, and Cys288 for Keap1 functions in a transgenic complementation rescue experiment in mice (23). Although rigorous verification of the in vivo requirement for Cys434 is yet to come, a recent study demonstrated that Cys434 in Keap1 is one of the most sensitive cysteine residues to S-glutathionylation and that disulfide adduct formation of Cys434 with GSH causes marked structural changes in the Nrf2-binding surface of the Keap1 molecule (35). Thus, the specific S-guanylation of Cys434 by 8-nitro-cGMP may function as a molecular sensing system for RNOS and/or ROS. This result is an intriguing addition to our model of the cysteine code in that each electrophile efficiently attacks a specific set of cysteine residues in vivo (22, 23).

We have determined that the Keap1-Nrf2 complex is composed of one molecule of Nrf2 and two molecules of Keap1 (15, 36). Our recent single-particle electron microscopic analysis revealed a cherry-bob structure (i.e. homodimer structure) of Keap1 (37). The BTB domain at the N-terminal region of Keap1 contributes to the homodimer formation, and DC domains at the C-terminal region consist of the two spheres. In addition, a previous co-crystallization study showed that two neighboring motifs of Nrf2 (i.e. DLG and ETGE) interact with the β-propeller structure at the bottom of the DC domain (36, 38). We have proposed a two-site binding (hinge and latch) model for the induction of Nrf2 activity. In the model, simultaneous binding of DLG and ETGE motifs to the Keap1 cherry-bob structure allows rapid ubiquitination of Nrf2 for efficient degradation (15, 36). Any events that distort or dissociate this tertiary complex stabilize Nrf2 by disrupting the low affinity binding between the ETGE/DLG motif and the DC domain.

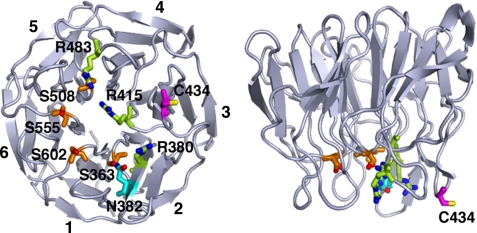

In this study, MS analyses showed that Cys434 of Keap1 is the target residue of S-guanylation. On the basis of the x-ray crystallographic analysis, Cys434 is located at blade 3 and exposed to the outer surface of the β-propeller structure, as shown in Fig. 9 (38, 39). As for the mechanism of how S-guanylation of Cys434 causes Nrf2 activation, we can envision two possibilities. One is that S-guanylation of Cys434 may weaken Keap1 binding to the ETGE and DLG motifs of Nrf2, because Cys434 is positioned close to the Nrf2-binding region of the DC domain (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Structure of the interface between KEAP1 and Nrf2 and location of Cys434. A bottom view (left panel) and a side view (right panel) of the KEAP1-DC structure as revealed by x-ray crystallography (38) are shown. Cys434 is pink. Residues in KEAP1 involved in direct interaction with the ETGE motif are indicated: Arg380, Arg415, and Arg483 in dark blue; Ser363, Ser508, Ser555, and Ser602 in orange; and Asn382 in light blue. Numbers of the blade structure (1–6) in KEAP1 are shown around the bottom view of the molecular model.

The other possibility is that the Cys434 modification may affect the integrity of the entire Keap1-Nrf2 complex. When the atomic model of the DC domain was fitted into the overall structure of the Keap1 homodimer obtained from single-particle electron microscopy, the globular portion of the Keap1 cherry-bob structure had greater bulk than did the DC domain, which suggests that the external surface of the DC domain is wrapped with the other portion of Keap1, possibly the intervening region between the BTB and DC domains (37). Thus, S-guanylation may disrupt the globular structure containing the DC domain, which would lead to disturbance of the whole structure and the decline of ubiquitin ligase activity of the Cul3-Keap1 complex.

This study determined that 8-nitro-cGMP mediates the cytoprotective response through S-guanylation of Keap1. Indeed, we found that treatment of C6 cells with 8-nitro-cGMP ameliorated cell death induced by oxidative stress. We also found that 8-nitro-cGMP increased the nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 and expression of HO-1. NO-induced expression of HO-1 reportedly contributes to cell survival in solid tumor models and during bacterial infection (11, 40, 41). Therefore, cytoprotection conferred by 8-nitro-cGMP after H2O2 exposure is associated, at least in part, with increased HO-1 expression. On the basis of these observations, we conclude that HO-1 is one of the major effectors mediating cytoprotective activity of 8-nitro-cGMP.

In summary, we clarified NO-dependent formation of 8-nitro-cGMP and simultaneous S-guanylation of Keap1 by 8-nitro-cGMP in cultured C6 cells. This NO- and 8-nitro-cGMP-mediated signaling pathway leads to Nrf2 activation and expression of cytoprotective genes, including HO-1, which seems to be involved in the adaptive response to oxidative stress in general. Identification of S-guanylation of Keap1 specifically at Cys434 in vivo unequivocally demonstrates that Keap1 exploits multiple sensing mechanisms that result in initiation of the Nrf2 pathway. An important idea emerging here is that S-guanylation of Keap1 by 8-nitro-cGMP is a unique trigger of the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway for enhancing cytoprotective activity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank J. B. Gandy for excellent editing of the manuscript. We also thank M. Fukase and M. Nakazawa (Osaka Prefecture University) for technical assistance. Thanks are also due to A. Irie (Kumamoto University) for technical support in the mass spectrometry analysis.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research and grants-in-aid for scientific research on Innovative Areas (research in a proposed area) from the Ministry of Education, Sciences, Sports and Technology (MEXT) and the Targeted Protein Research Program promoted by MEXT. This work was also supported by grants from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan and Tohoku University Global Centers of Excellence program for the Conquest of Diseases with Network Medicine.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Methods” and Figs. S1–S10.

- RNOS

- reactive nitrogen oxide species

- 8-nitro-cGMP

- 8-nitroguanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- PDE

- phosphodiesterase

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- MALDI

- matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization

- TOF

- time-of-flight

- MS

- mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

- tandem mass spectrometry

- SNAP

- S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine

- BSO

- buthionine sulfoximine

- iNOS

- inducible NO synthase

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- IFN-γ

- interferon-γ

- TNFα

- tumor necrosis factor α

- IL-1β

- interleukin-1β

- l-NMMA

- Nω-monomethyl-l-arginine

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- sGC

- soluble guanylate cyclase

- LC

- liquid chromatography

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography

- ECD

- electrochemical detection

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- NEM

- N-ethylmaleimide

- siRNA

- small interfering RNA

- HSA

- human serum albumin

- SNO-HSA

- S-nitrosylated human serum albumin

- c[15N5]GMP

- [U-15N5, 98%]guanosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate

- [15N5]GTP

- [U-15N5, 98%]guanosine 5′-triphosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Murad F. (1986) J. Clin. Invest. 78, 1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bredt D. S., Hwang P. M., Snyder S. H. (1990) Nature 347, 768–770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiserich J. P., Hristova M., Cross C. E., Jones A. D., Freeman B. A., Halliwell B., van der Vliet A. (1998) Nature 391, 393–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schopfer F. J., Baker P. R., Freeman B. A. (2003) Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 646–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radi R. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 4003–4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akaike T., Okamoto S., Sawa T., Yoshitake J., Tamura F., Ichimori K., Miyazaki K., Sasamoto K., Maeda H. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 685–690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshitake J., Akaike T., Akuta T., Tamura F., Ogura T., Esumi H., Maeda H. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 8709–8719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terasaki Y., Akuta T., Terasaki M., Sawa T., Mori T., Okamoto T., Ozaki M., Takeya M., Akaike T. (2006) Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 174, 665–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sawa T., Akaike T., Ichimori K., Akuta T., Kaneko K., Nakayama H., Stuehr D. J., Maeda H. (2003) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 311, 300–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawa T., Zaki M. H., Okamoto T., Akuta T., Tokutomi Y., Kim-Mitsuyama S., Ihara H., Kobayashi A., Yamamoto M., Fujii S., Arimoto H., Akaike T. (2007) Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 727–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zaki M. H., Fujii S., Okamoto T., Islam S., Khan S., Ahmed K. A., Sawa T., Akaike T. (2009) J. Immunol. 182, 3746–3756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Motohashi H., Yamamoto M. (2004) Trends Mol. Med. 10, 549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakabayashi N., Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Holtzclaw W. D., Kang M. I., Kobayashi A., Yamamoto M., Kensler T. W., Talalay P. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 2040–2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Holtzclaw W. D., Kensler T. W. (2005) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 18, 1779–1791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tong K. I., Katoh Y., Kusunoki H., Itoh K., Tanaka T., Yamamoto M. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 2887–2900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watai Y., Kobayashi A., Nagase H., Mizukami M., McEvoy J., Singer J. D., Itoh K., Yamamoto M. (2007) Genes Cells 12, 1163–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinkova-Kostova A. T., Holtzclaw W. D., Cole R. N., Itoh K., Wakabayashi N., Katoh Y., Yamamoto M., Talalay P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 11908–11913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levonen A. L., Landar A., Ramachandran A., Ceaser E. K., Dickinson D. A., Zanoni G., Morrow J. D., Darley-Usmar V. M. (2004) Biochem. J. 378, 373–382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi A., Kang M. I., Watai Y., Tong K. I., Shibata T., Uchida K., Yamamoto M. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 221–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckley B. J., Li S., Whorton A. R. (2008) Free Radic. Biol. Med. 44, 692–698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh J. Y., Giles N., Landar A., Darley-Usmar V. (2008) Biochem. J. 411, 297–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kobayashi M., Li L., Iwamoto N., Nakajima-Takagi Y., Kaneko H., Nakayama Y., Eguchi M., Wada Y., Kumagai Y., Yamamoto M. (2009) Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 493–502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yamamoto T., Suzuki T., Kobayashi A., Wakabayashi J., Maher J., Motohashi H., Yamamoto M. (2008) Mol. Cell Biol. 28, 2758–2770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomita T., Tsuyama S., Imai Y., Kitagawa T. (1997) J. Biochem. 122, 531–536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koppenol W. H., Kissner R., Beckman J. S. (1996) Methods Enzymol. 269, 296–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaffrey S. R., Erdjument-Bromage H., Ferris C. D., Tempst P., Snyder S. H. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, 193–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eggler A. L., Luo Y., van Breemen R. B., Mesecar A. D. (2007) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 20, 1878–1884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mosmann T. (1983) J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kirkland R. A., Saavedra G. M., Franklin J. L. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 11315–11326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Traut T. W. (1994) Mol. Cell Biochem. 140, 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hur J., Lee P., Kim M. J., Kim Y., Cho Y. W. (2010) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 391, 1526–1530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito Y., Taguchi H., Fujii S., Sawa T., Kida E., Kabuto C., Akaike T., Arimoto H. (2008) Chem. Commun. 5984–5986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawa T., Arimoto H., Akaike T. (2010) Bioconjug. Chem., in press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Z., Ji X., Boysen P. G. (2004) Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286, H1433–H1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holland R., Hawkins A. E., Eggler A. L., Mesecar A. D., Fabris D., Fishbein J. C. (2008) Chem. Res. Toxicol. 21, 2051–2060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tong K. I., Padmanabhan B., Kobayashi A., Shang C., Hirotsu Y., Yokoyama S., Yamamoto M. (2007) Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 7511–7521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogura T., Tong K. I., Mio K., Maruyama Y., Kurokawa H., Sato C., Yamamoto M. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2842–2847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Padmanabhan B., Tong K. I., Ohta T., Nakamura Y., Scharlock M., Ohtsuji M., Kang M. I., Kobayashi A., Yokoyama S., Yamamoto M. (2006) Mol. Cell 21, 689–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]