Abstract

The formation of blood vessels (angiogenesis) is a highly orchestrated sequence of events involving crucial receptor-ligand interactions. Angiogenesis is critical for physiological processes such as development, wound healing, reproduction, tissue regeneration, and remodeling. It also plays a major role in sustaining tumor progression and chronic inflammation. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-B, a member of the VEGF family of angiogenic growth factors, effects blood vessel formation by binding to a tyrosine kinase receptor, VEGFR-1. There is growing evidence of the important role played by VEGF-B in physiological and pathological vasculogenesis. Development of VEGF-B antagonists, which inhibit the interaction of this molecule with its cognate receptor, would be important for the treatment of pathologies associated specifically with this growth factor. In this study, we present the crystal structure of the complex of VEGF-B with domain 2 of VEGFR-1 at 2.7 Å resolution. Our analysis reveals that each molecule of the ligand engages two receptor molecules using two symmetrical binding sites. Based on these interactions, we identify the receptor-binding determinants on VEGF-B and shed light on the differences in specificity towards VEGFR-1 among the different VEGF homologs.

Keywords: Crystal Structure, Protein Structure, Receptor Structure-Function, Signal Transduction, X-ray Crystallography, Angiogenesis, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

Introduction

Angiogenesis, a process involved in physiological (embryogenesis, wound healing, and tissue repair) as well as pathological (tumor progression, psoriasis, diabetic retinopathy, and rheumatoid arthritis) processes, is the result of a complex interplay of positive and negative regulators (1–3). A diverse collection of polypeptide growth factors and their cognate receptors has been implicated as inducers of the vascular system. The best characterized member, vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A),2 is a diffusible dimeric glycoprotein involved in the differentiation, migration, proliferation, and vascular permeability of endothelial cells. VEGF-A along with VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, placenta growth factor (PlGF) and related proteins called VEGF-E (Orf virus-encoded protein), and VEGF-F (variant isolated from snake venom) belong to a structurally related superfamily of proteins called the cysteine-knot growth factors (4, 5). The members of the VEGF family of cytokines mediate their different biological roles by binding to three high affinity tyrosine kinase receptors as follows: VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3. Although VEGF-A binds to both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2, VEGF-B and PlGF bind only VEGFR-1. VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-3 bind to VEGF-C and VEGF-D to exert their cellular responses (6, 7). VEGFR-2 achieves most of the biologically relevant angiogenic signaling in endothelial cells. Apart from these three tyrosine kinases, discriminating splice forms of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and PlGF bind semaphorin receptors neuropilins 1 and 2 (8). Some of these isoforms also bind heparan sulfate proteoglycans (9).

Homodimeric VEGF-B exists as two alternatively spliced forms, VEGF-B167 and VEGF-B186, with identical N-terminal domains but nonhomologous C-terminal domains. VEGF-B has wide tissue distribution albeit overlapping with VEGF-A, and experiments reveal that VEGF-B can act as an endothelial cell growth factor (10). VEGF-B displays quite prominent expression in the developing heart and in several muscle derivatives during embryonic development (11, 12). Gene knock-out studies in mice by ablating VEGF-B expression revealed that response to myocardial recovery from ischemia and vascular occlusion is jeopardized (13). Recently, experiments revealed that VEGF-B167 (along with VEGF-A165 and PlGF-1) induced mast cell chemotaxis by activation of VEGFR-1 and had a role to play in inflammatory and neoplastic angiogenesis (14). Around the same time, it was shown that although VEGF-B is dispensable for blood vessel growth, it was absolutely critical for vascular survival. This study indicated that this property of VEGF-B, regulated by neuropilin-1 and VEGFR-1, could be targeted to inhibit angiogenesis (15). VEGF-B has also been implicated in several pathological conditions, such as metastases of cancer cells, through activation of plasminogen activator (16), pulmonary hypertension (17), and growth of tumors (18). Interestingly, some recent studies implicate a role for VEGF-B in lipid metabolism, a function not yet assigned for an angiogenic growth factor (19). Taken together, data from all the previous studies suggest that VEGF-B, unlike VEGF-A, is in the nascent stage of establishing its role in the field of angiogenesis. Studies focusing on VEGF-B along with its molecular and cellular targets become necessary to delineate the angiogenic capability of this cysteine-knot protein.

VEGF-B is known to regulate the bioavailability and activity of VEGF-A and PlGF by forming heterodimers with these growth factors (10, 20) via ligation of VEGFR-1 (21) and/or neuropilin-1 (22). The mitogenic capability of VEGFR-1 is not yet completely understood. Some experiments point to a synergistic role for VEGFR-1 whereby this receptor molecule regulates angiogenesis by augmenting VEGFR-2 signaling. Data also indicate that binding and phosphorylation of VEGFR-1 (by VEGF-B) can potentiate angiogenesis via activation of the Akt-endothelial nitric-oxide synthase pathway (23). Intriguing yet controversial data from experiments evaluating the role of VEGFR-1 mean that the therapeutic potential of ligands that bind specifically to this receptor has so far not been capitalized.

A considerable amount of structural information is available for VEGF-A. Three-dimensional structures of VEGF-A in native form (24) and in complex with VEGFR-1 (25), Fab-12 (26), Fab-Y0317 (27), Fab-G6 and Fab-B20-4 (28) have been elucidated. The same is not true for the VEGFR-1-specific ligands, VEGF-B and PlGF. Although the structures of the minimal receptor-binding domains of PlGF (29) and VEGF-B (30) have been elucidated, only the complex of PlGF with VEGFR-1 (31) has been reported until now. Structural data on VEGF-B were recently complemented by the elucidation of the structure of this ligand in complex with a neutralizing antibody fragment Fab2H10 (32). Here, we report the three-dimensional structure of VEGF-B in complex with domain 2 of VEGFR-1. The complex is topologically similar to the other receptor complexes reported for the VEGF family. However, structural comparisons of the present complex with the known receptor-ligand interactions highlight unique molecular features that help shed light on the differences in the molecular recognition of VEGFR-1 that seem to affect downstream signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Recombinant VEGF-B(10–108)

Human VEGF-B(10–108) cDNA was PCR-amplified from a plasmid encoding full-length human VEGF-B (clone ID: IRAUp969H0431D, imaGenes) using KOD Hot Start DNA polymerase (Novagen) and the following primers: forward primer 5′-GGTATTGAGGGTCGCCACCAGAGGAAAGTGGT-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGAGGAGAGTTAGAGCCCTACTTTTTTTTAGGTCTGCAT-3′. The PCR product was cloned into pET-32 Xa/LIC plasmid (Novagen), and the resulting expression plasmid was transformed into Rosetta-gamiTM B(DE3)pLysS strain. Cells were grown in TB media at 30 °C to an A578 of 1.0, cooled to 14 °C, and induced overnight at the reduced temperature by addition of 0.3 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside.

Cells obtained from 0.5 liter of bacterial culture were resuspended in 20 ml of sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 (lysis buffer), and lysed by sonication. The lysate was centrifuged for 20 min at 20,000 × g following which the supernatant was discarded. The pellet was resuspended in lysis buffer supplemented with 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, sonicated, and centrifuged. The pellet, consisting primarily of VEGF-B(10–108) (fusion protein), was washed once again with lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 m NaCl and collected by centrifugation as before. The inclusion bodies were dispersed in 8 m urea, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.3 m reduced glutathione, 2 mm EDTA and stirred under nitrogen gas for 2 h. Solubilized protein was added dropwise to 500 ml of 0.5 m l-arginine, pH 8.0, containing 1.2 mm oxidized glutathione and left for 24 h at 19 °C. The solution was clarified by centrifugation for 30 min at 10,000 × g and diluted 5-fold with water, and refolded protein was bound on a 1-ml HiTrap FF column (GE Healthcare). The column was washed with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm imidazole, and the bound protein was eluted with 50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, and 300 mm imidazole. The purity and the homogeneity of the protein were monitored by SDS-PAGE.

Protein Complex Formation and Purification

Purified VEGF-B(10–108) (fusion protein) and VEGFR-1D2 (cloned, expressed, and purified as described in Ref. 25) were mixed in a 1:2.1 molar ratio and incubated at 4 °C for 12 h. The resulting complex was purified on Superdex 200 (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 150 mm NaCl. Thioredoxin tag and His6 tag from the fusion complex were cleaved with factor Xa. The cleavage reaction was again separated on Superdex 75 and equilibrated with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and 150 mm NaCl to elute the untagged VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 complex. The complex was concentrated to 2.8 mg/ml.

Protein Crystallization, Data Collection, and Processing

Crystals were grown by sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 16 °C. Crystallization buffer containing 14% PEG 4000, 0.1 m sodium citrate, pH 5.6, and 0.2 m LiCl was mixed with an equal volume of protein solution. A complete dataset to 2.7 Å was collected from a single crystal using the Diamond Light Source, UK. Data were processed and scaled using HKL2000 (33) in the monoclinic space group P21 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic statistics

| Data collection | |

| Space group | Monoclinic, P21 (1 complex per asymmetric unit) |

| Cell dimensions | a = 39.25 Å; b = 65.45 Å; c = 82.91 Å; β = 90.31° |

| Resolution | 40-2.7 Å |

| No. of reflections measured | 136,489 |

| No. of unique reflections | 12,164 |

| Rsym (outermost shell)a | 12.2% (24.4%) |

| I/σI (outermost shell) | 12.4 (2.52) |

| Completeness (outermost shell) | 82.4% (39.3%) |

| Refinement | |

| Rcrystb | 28.2% |

| Rfree (%)c | 36.4% |

| r.m.s.d. in bond length | 0.007 Å |

| r.m.s.d. in bond angles | 1.11° |

| Average B-factor | 40.1 Å2 |

a Rsym = Σ(|Ij − 〈I〉|)/Σ 〈I〉, where Ij is the observed intensity of reflection j, and 〈I〉 is the average intensity of multiple observations.

b Rcryst = Σ‖Fo| − |Fc‖/Σ|Fo|, where Fo and Fc are the observed and calculated structure factor amplitudes, respectively.

c Rfree is equal to Rsym for a randomly selected 5% reflections not used in the refinement.

Structure Determination and Refinement

The structure of VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 complex was determined by maximum likelihood molecular replacement using the program PHASER from CCP4 suite (34). The initial search models used were native VEGF-B(10–108) (PDB code 2C7W) (30) and VEGFR-1D2 from VEGF-A in complex with VEGFR-1D2 complex (PDB code 1FLT) (25). The asymmetric unit consists of a VEGF-B(10–108) dimer and two molecules of VEGFR-1D2. Alternate rounds of model building with the program COOT (35) and further refinement with the program CNS (36) and finally REFMAC (34) resulted in the final structure for all data between 40 and 2.7 Å resolution (Table 1).

RESULTS

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Recombinant VEGF-B(10–108)

The cloning, expression, and purification of VEGF-B(10–108) have been reported previously (37). However, the reported protocol was not followed in this study as it involved three chromatographic steps to yield pure protein. To overcome this, recombinant VEGF-B(10–108) was cloned into pET-32 Xa/LIC vector and expressed as a fusion protein containing a thioredoxin (109 amino acids), His tag, and an S tag at the N-terminal end. Despite the presence of the thioredoxin tag and expression in Rosetta-gamiTM B(DE3)pLysS cells to enhance the formation of disulfide bonds in the cytoplasm, VEGF-B(10–108) expressed only in the insoluble fraction.

Solubilized inclusion bodies were refolded in an arginine-based buffer, and the protein was purified using Ni2+ affinity chromatography. SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of the purified protein revealed a major band with an apparent molecular mass of 56 kDa. This value is in agreement with the predicted molecular mass from the protein sequence and corresponds to the dimeric form of VEGF-B(10–108). Following metal affinity chromatography, the yield of pure dimeric tagged protein from 1 liter of bacterial culture was estimated to be between 10 and 12 mg.

Quality of the Structure

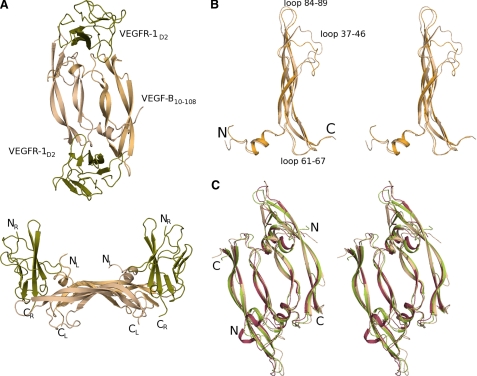

The structure of the complex between the minimal receptor-binding domain of VEGF-B (VEGF-B(10–108)) and domain 2 of VEGFR-1 (VEGFR-1D2) has been determined at 2.7 Å resolution (Fig. 1A and Table 1). The two symmetrical ends of the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer engage one molecule each of VEGFR-1D2 in the asymmetric unit. Analysis of the Ramachandran plot (38) indicated that 84.9% of residues fall in the most favored region and 15.1% in the additional allowed regions of the plot. There are no residues in the disallowed region of the plot. The construct for the receptor contains amino acids 129–226. However, electron density for the first three N-terminal amino acid residues could not be observed for chain X (MolA), and the last two residues at the C-terminal end could not be observed for chain C (MolB) of VEGFR-1D2. Although none of the residues in MolA of the receptor have been modeled as alanine or glycine, residues 139, 174, 180, and 182–184 of MolB have been clipped to the Cβ atom to compensate for poor electron density for the side chains. In the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer, monomer A has the full complement of amino acids, whereas the first N-terminal (residue 10) and the last C-terminal residue (residue 108) are not observed in monomer B. Electron density for monomer A seems to be better defined than that for monomer B, which is reflected by the number of residues that have been modeled as alanine or glycine in both monomer A (residues 12, 18, 38, and 85) and monomer B (residues 12, 38, 42, 44, 45, 84, 89, and 96). None of these residues form the binding interface and thus do not affect our analysis of the interface.

FIGURE 1.

Ribbon representation of VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 and its structural comparison with other members of the VEGF family. A, three-dimensional crystal structure of the complex between VEGF-B(10–108) and VEGFR-1D2. The structure has been color-coded to differentiate between different components. The two monomers of VEGF-B(10–108) are shown in wheat and light orange color, respectively, and the two copies of VEGFR-1D2 are colored olive-green. The lower panel is the side view of the complex with the N and C termini of each chain labeled. B, stereo view of the superpositioned monomers of VEGF-B(10–108) from the VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 complex. The N- and C-terminal ends along with the loop regions are labeled. The figure highlights the conformational differences between the two monomers. C, stereo view of the superpositioned dimers of VEGF-B(10–108) (wheat), VEGF-A(8–109) (olive-green), and PlGF-1 (raspberry) from their respective complexes with VEGFR-1D2. The figure shows that the structural core of the three dimers align well with conformational rearrangement of the loop regions that interface with the receptor. Figures were made using PyMOL.

Average temperature factors are 39.7 Å2 for VEGF-B(10–108) dimer, 39.3 Å2 for MolA, and 44.1 Å2 for MolB. Temperature factors for the residues, from the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer and the two molecules of receptor, involved in intermolecular interactions at the receptor-ligand interface are significantly lower than the average B-factor for the structure. A total of 44 water molecules was observed in the asymmetric unit. Also found interacting with the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer is one molecule of glycerol positioned along the symmetry axis such that both monomers of VEGF-B share the same molecule of glycerol. The average temperature factor for this shared glycerol molecule is 23.2 Å2.

Overall Structure of the VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 Complex

The VEGF-B(10–108) dimer in the receptor complex (Fig. 1A) is topologically similar to the dimer in the native structure (30) and in complex with the neutralizing antibody fragment Fab2H10 (32). The dimer essentially consists of two anti-parallel β-sheets with the cysteine-knot and the hydrophobic core positioned symmetrically opposite each other (30). The two monomers in the present structure superimpose with an r.m.s.d of about 1.0 Å (Fig. 1B), which is much higher than what was observed between the two monomers in the native (0.61 Å (30)) and in the antibody complex structure (0.62 Å (32)). Conformational differences in the three loop regions, residues 37–46, 61–67, and 84–89 of the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer (Fig. 1B), are observed in the present complex as well, similar to what was previously seen in the complex with the antibody fragment. In the present complex, the flexibility is quite pronounced for the loop comprising residues 37–46. Residues from the aforementioned loop regions, apart from loop 37–46, form a part of the binding interface between the receptor and the ligand. Given the lack of intermolecular interactions for loop 37–46 with both the receptor molecule and symmetry-related molecules, one could assume that its resulting pliancy is responsible for the higher r.m.s.d. value between the two VEGF-B(10–108) monomers in the present complex.

Domain 2 of VEGFR-1 is the minimal binding domain required to ligate with VEGF-B. Two receptor molecules bind to the distant poles of the dimeric ligand, each consisting of two β-sheets, one made up of five strands and the other made up of three strands. Each receptor has a disulfide bond formed between Cys-158 and Cys-207. The two molecules of VEGFR-1D2 in the asymmetric unit superimpose onto each other with an r.m.s.d. of around 0.9 Å for 94 Cα atoms. Superposition of VEGFR-1D2 from the three receptor-ligand complexes results in an r.m.s.d. of 0.8 Å for 95 Cα atoms between VEGF-B and VEGF-A complex (25) and 0.9 Å for 91 Cα atoms between VEGF-B and PlGF complex (31). This value is higher than that observed between VEGFR-1D2 from the VEGF-A and PlGF complex (∼0.6 Å for 91 Cα atoms).

The topology of the VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 complex (Fig. 1A) is essentially the same as that seen in the receptor complexes elucidated so far for the VEGF family of ligands. Pairwise superposition of these dimeric growth factors (Fig. 1C) in their receptor-bound state results in an r.m.s.d. of 1.5 Å over 218 Cα atoms (PDB code 1FLT (25)) and 2.0 Å over 256 Cα atoms (PDB code 1RV6 (31)). A comparison of VEGF-B(10–108) from the present complex with the structures of the unbound form (PDB code 2C7W (30)) and that bound to Fab-2H10 (PDB code (32)) results in an r.m.s.d. of 1.2 Å (181 Cα atoms) and 1.3 Å (175 Cα atoms), respectively.

VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 Interface

The mode of VEGFR-1D2 binding to the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer creates two interacting surfaces symmetrically opposite each other. Both these interfaces involve mostly similar interactions; hence, all our analysis and description given here refer to VEGF-B(10–108)-MolA interface unless otherwise indicated (Table 2). Complex formation between VEGF-B(10–108) dimer and the receptor buries around 1500 Å2 of the solvent-accessible surface area at each of the two interfaces. This value is comparable with the total surface area buried in each of the interfaces between PlGF and VEGFR-1D2 (1650Å2 (31)). It is, however, twice the area reported for that between VEGF-A and the same receptor domain (25). The shape correlation between the interacting surfaces of VEGF-B(10–108) and domain 2 of the receptor molecule was calculated to be about 0.66 (34). This value is similar to that calculated for the VEGF-A (0.62) and PlGF (0.65) receptor complexes but slightly more than that for the VEGF-B(10–108)·Fab2H10 complex (0.54 (32)).

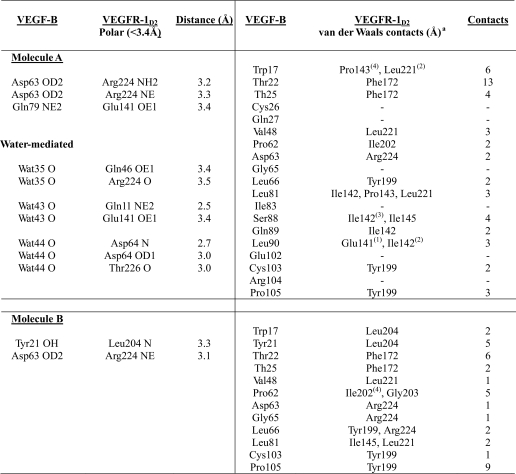

TABLE 2.

Intermolecular contacts at the VEGF-B(10–108) · VEGFR-1D2 interface

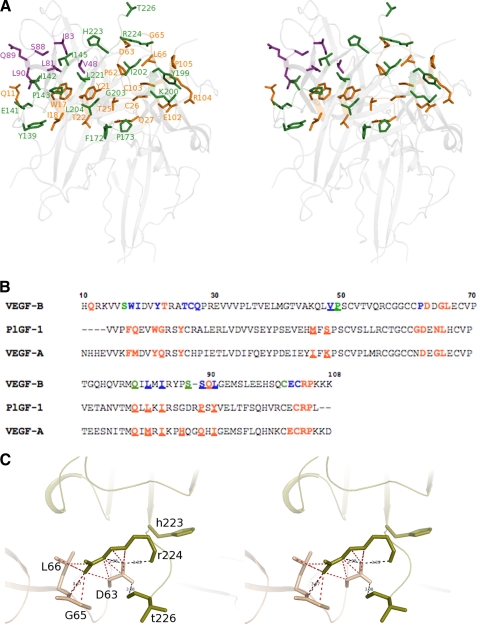

The interface is flat, largely hydrophobic and therefore energetically favored by the shape complementarity between the two interacting surfaces. Twenty six residues from the growth factor (residues from the N-terminal helix α1; the loop connecting strands β3 and β4; and the C-terminal residues from one monomer along with residues from β2 and the loop connecting strands β5 and β6 of the other monomer) and 25 amino acids from the receptor (segments 139–147, 171–175, 199–204, and 219–226) form a part of this contact surface. However, only 19 residues from VEGF-B(10–108) and 12 residues from VEGFR-1D2 participate in forming interactions at the binding interface (Fig. 2A). The two interfaces formed at the opposite ends of VEGF-B(10–108) are virtually identical, with the exception of loss/gain of a couple of residues contributed to the MolB interface from the loop connecting strands β5 and β6. These differences (detailed in Table 2) are mainly due to the slight rotations of each receptor molecule around the interface with respect to the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer. This difference in the orientation of the bound VEGFR-1D2 has been previously observed in the complex of VEGF-A with the receptor (25).

FIGURE 2.

VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 interface. A, stereo view of the interface of the VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 complex. Residues at the interface are rendered as ball-and-stick models. Residues from VEGFR-1D2 are shown in olive-green, and the residues from the two monomers of VEGF-B(10–108) are colored orange and purple, respectively. Ribbon representation of VEGF-B(10–108) and VEGFR-1D2 is shown in light gray in the background. B, structure-based sequence alignment of the receptor-binding domain of VEGF-B(10–108), VEGF-A(8–109), and PlGF-1. VEGF-B(10–108) numbering starts from 10 and is shown at the top (VEGF-A(8–109) numbering also begins from 10. PlGF-1 numbering starts from 22). Residues that interact with VEGFR-1D2 are colored red in all three sequences. Residues from monomer are colored and indicated as boldface and underlined and the others are just boldface. In the VEGF-B(10–108) sequence, the residues that interact with both VEGFR-1D2 and Fab-2H10 (32) are colored blue, and the amino acids that bind only Fab-2H10 are in green. C, stereo view of the environment of Asp-63 from VEGF-B(10–108) at the interface. Residues from the ligand are shown in wheat and those from the receptor are shown in olive-green. The interactions at the interface are shown as dotted lines. Hydrogen bonds are colored black with distances labeled. van der Waals contacts are colored red. Distances were calculated using CONTACT (35). D, top panel shows the contact surface on the ligands VEGF-B(10–108), VEGF-A(8–109), and PlGF-1. The bottom panel shows the binding surface on VEGFR-1D2 from its three complexes. The overall surface is colored gray. Residues (in both panels) are colored according to the percentage of accessible surface area in the interface (0–10%, chlorine; 11–20%, chartreuse; 21–30%, beryllium; 31–40%, dash; 41–50%, pale yellow; 51–60%, light orange; 61–70%, bright orange; 71–80%, orange; 81–90%, pink and 91–100%, red. E, mapping the electrostatic potentials to the protein surfaces of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, PlGF-1, VEGF-C VEGFR-1 (domain 2) and VEGFR-2 (domain 2). The color code of blue to red covers surface potential going from positive to negative charge. Figure was generated using PyMOL.

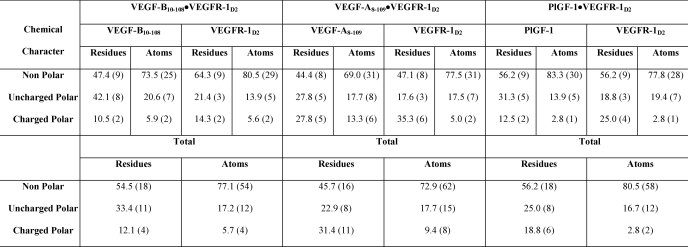

The interface involves 6 hydrogen bonds (three direct and three mediated via water molecules) and 49 van der Waals interactions (Table 2) between VEGF-B(10–108) and MolA. (The interface with MolB has 12 hydrophobic interactions less than the MolA interface.) At each of the two interfaces, three-quarters of the interactions come from one monomer (74%), and only 26% are contributed by the other monomer of VEGF-B(10–108). None of these interactions between the receptor and the ligand, neither van der Waals contacts nor hydrogen-bonding interactions, are between main-chain atoms. The network of interactions, involving mainly side chains, is contributed by 18 nonpolar residues (54.5% of the total 33 residues at the interface), only 4 charged polar residues (12.1%; equal contributions from positively and negatively charged amino acids), and 33.4% of uncharged polar residues. Almost two-thirds of the hydrophobic character of the interface is contributed by leucine/isoleucine/proline residues. This ratio for charge character at the binding interface changes significantly when individual atoms involved in the interactions are considered. At the atomic level, the interface includes 77% nonpolar atoms, 17% of the atoms are uncharged polar, and only a very small percent belong to the charged category of atoms (Table 3).

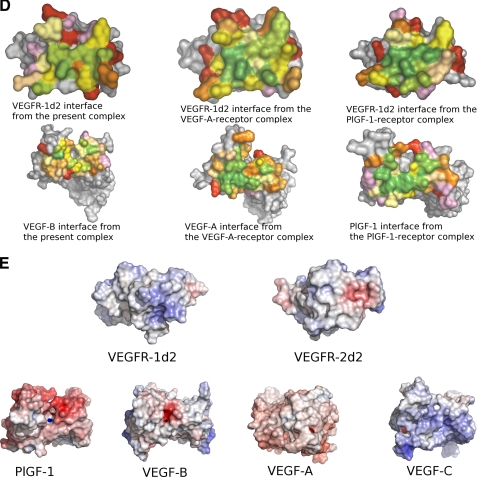

TABLE 3.

Chemical character of the residues and atoms interacting at the binding interface

DISCUSSION

Structure of VEGF-B(10–108) Bound Versus Unbound

The average distance between the backbone of the superimposed protein, in its bound and unbound form, is only 1.2 Å. This value, which is well within the range of allowed conformational flexibility, is similar to the r.m.s.d. calculated for the native protein superposed onto the dimer in the antigen·antibody complex (32). However, some perceptible changes are observed in the loop regions of the growth factor. The most significant is deviation in the peptide segment connecting residues 36–46. This loop is quite different even within the two monomers of the present structure (Fig. 1B). The Cα displacement for this region ranges from a maximum of 9.3 Å to a minimum of 1.7 Å. Comparing this loop with that in the native as well as in the antigen·antibody complex, one observes that this deviation is mainly induced by the lack of symmetry-related interactions. The overall conformation of the other two loop regions, regions 61–67 and 83–89, is quite similar in the native and bound forms of the dimer. These loops are involved either in weak crystal packing forces in the native structure or binding forces with the receptor in the present complex. Therefore, it can be said that the overall topology of the VEGF-B(10–108) dimer is not altered significantly when bound to the receptor.

Receptor-Ligand Interface, Comparison with Other Known Receptor Complexes

VEGF-B is the second growth factor that has been identified as a VEGFR-1-specific ligand (first one was PlGF). The present crystal structure of VEGF-B(10–108) in complex with domain 2 of VEGFR-1 shows a similar mode of binding as seen before in the two complexes of this receptor with VEGF-A (25) and PlGF (31). Analysis of these two previously solved structures showed that the two complexes were quite similar, and therefore it was suggested that the ligands required no induced-fit mechanism to enable receptor binding. In the present complex, we observe that VEGF-B deviates to a similar degree from both PlGF and VEGF-A (r.m.s.d. ∼1.8 Å over Cα 166 atoms). This deviation is slightly higher than that observed for superposition of VEGF-A and PlGF in their receptor-bound forms. Flexibility of the loop regions (causing this deviation) is likely to be a result of differences in the crystal packing environments between the three complexes. Also, it must be noted that the three growth factors differ in the length of the loop regions, especially the loop comprising residues 83–89 (VEGF-B numbering). The amino acid sequence of this region in VEGF-B has three deletions as opposed to two in VEGF-A and PlGF. Similar superposition of only the receptor molecules from the three complexes reveals that they are quite similar to each other with an r.m.s.d. of only about 0.8 Å over 95 Cα atoms. Taken together, the results of our analysis suggest that VEGF-B also does not undergo any major conformational changes to enable its binding to VEGFR-1.

A closer look at the interface of the three complexes reveals that despite low sequence conservation within the interacting residues from the growth factors, the binding expanse rendered to the receptor is virtually identical (Fig. 2B). Contribution from the ligands is quite varied in that only six residues are strictly conserved (∼25% of the total residues). This number rises to eight if residues conserved in character are also taken into account. It is interesting to note that despite the subtle (Leu-90 in VEGF-B and Ile-91 in VEGF-A) and/or obvious (Val-48 in VEGF-B, Lys-48 in VEGF-A, and Ser-56 in PlGF) amino acid differences between these three members of the VEGF family, the amino acids compensate for these changes by occupying structurally equivalent positions at the interface and therefore mediate very similar interactions with the receptor.

A major site for VEGFR-1 binding involves the loop region 60–68 of VEGF-A (numbering is same in VEGF-B but 69–76 region in PlGF-1) as indicated by mutational as well as structural studies. Alanine-scanning mutagenesis of VEGF-A showed that negatively charged residues Asp-63, Glu-64, and Glu-67 are essential for binding to the receptor (39). VEGF-B seems to share a requirement for acidic residues in this loop region. The residues are only partially conserved in PlGF-1. It seems that although position 63 of VEGF-A (position 71 in PlGF-1) is most dominant among the three acidic residues, the combination of mutations exhibit a synergistic effect on the interaction with VEGFR-1. It was also shown that Arg-224 (along with His-223) was an important ligand-binding determinant on VEGFR-1D2 (40). In both VEGF-A and PlGF-1 complexes, Asp-63 (Asp-71 in PlGF-1) makes a couple of charge-mediated hydrogen bonds with the side chain of Arg-224 of VEGFR-1D2. These polar interactions are mirrored by the corresponding aspartate in VEGF-B as well. Given the similarity of interactions in all three receptor-bound complexes, one would assume that this acidic stretch of residues would play an important role in VEGF-B as well (Fig. 2C). However, Olofsson et al. (21) showed that although this anionic sequence in VEGF-B contributes to receptor affinity, the residues involved are not the major determinants for VEGFR-1 binding. Detailed comparison of the previous two complexes with the present complex gives an insight as to why this might be the case. In the VEGF-A complex (25), the residues from this loop region make a total of 12 interactions with Arg-224 of VEGFR-1D2. Mutation of Asp-63 to alanine means a loss of about 67% of these interactions. In the PlGF-1 complex (31), all the interactions with Arg-224 are lost when Asp-71 side chain gets truncated down to Cβ atom. In the VEGF-B complex, however, there are two more residues, Gly-65 and Leu-66, that compensate for the loss of interactions upon mutation of Asp-63 to alanine (Fig. 2C). These two residues contribute 50% of the total contacts made with Arg-224. The receptor-binding interface in the present complex is dominated by hydrophobic interactions contributed by seven nonpolar residues (Trp-17, Val-48, Pro-62, Leu-66, Leu-81, Ile-83, and Leu-90) on the VEGF-B surface alone. These engage in van der Waals contacts with hydrophobic residues (such as Ile-142, Phe-172, Ile-202, Leu-204, and Leu-221) that lie among the important VEGFR-1 residues like His-223 and Arg-224 (Fig. 2A), which have been shown to discriminate between VEGF-A and PlGF (40). Because Asp-63 and/or Asp-64 (or even the triple mutant D63A/D64A/E67A) affect binding to only a modest degree when altered to alanine, this suggests that there might be other residues, possibly noncharged residues such as Leu-66 causing more potent effects on the interaction of VEGF-B and VEGFR-1 with single/multiple alanine replacements.

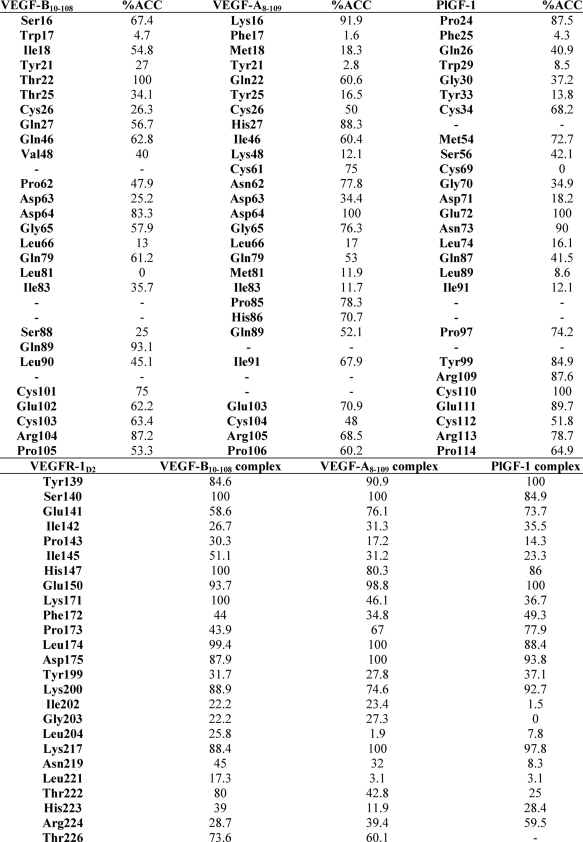

A comprehensive study of the surfaces buried at the interface in all three complexes reveals some very interesting differences (Fig. 2D). The residues rendered to the interface by the receptor are identical in all the three complexes. Most of these residues (with a few exceptions) make hydrophobic or hydrogen-bonding interactions with their respective ligands. Differences in the percentage of surface area of these residues accessible upon ligand binding (Table 4) give an insight into the potential importance of these amino acids in defining the affinity of VEGFR-1D2 toward the different members of the VEGF family. Similar differences are observed when the contact residues from the ligands are compared. For example, Ser-88 from VEGF-B(10–108) is buried more relative to the residues at its structurally equivalent position in VEGF-A(8–109) and PlGF-1. It is tempting to hypothesize that these differences might play a seminal role in determining receptor recognition and specificity of the VEGF homologs. However, further studies are required to analyze the importance of the VEGF-B residues that have come to light as being involved in binding to VEGFR-1 by virtue of the present structural study.

TABLE 4.

Accessible surface area for residues at the interface as calculated using DSSP (44)

DSSP indicates definition of secondary structure of proteins.

Receptor Recognition and Specificity, Structural Insights

Recognition and specificity for the tyrosine kinase receptors (VEGFR-1, VEGFR-2, and VEGFR-3) determine the role played by the different members of VEGF family of cysteine-knot proteins. Given the degree of sequence conservation among the different VEGF family members as well as the two tyrosine kinase receptors (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2), it is quite intriguing as to how specificity between these growth factors and their receptors is achieved. In this study, we have tried to use the tertiary structures of the different receptor-ligand complexes elucidated so far to address the question as to why VEGF-B (and PlGF) is able to interact with VEGFR-1 but not with VEGFR-2.

The structures of VEGFR-1 complexes (including the present complex) reveal that several negatively charged residues appear to be associated with receptor binding to some degree. Mutagenesis experiments complemented these findings by implicating positively charged residues in VEGFR-2 binding (39). The recently elucidated structure of VEGF-C in complex with domains 2 and 3 of VEGFR-2 (PDB code 2X1X (41)) revealed that not only was the overall architecture of the VEGF-receptor complex retained, the receptor domains (domain 2 from both the tyrosine kinase receptors) were indeed similar as suggested by amino acid sequence identity of about 32%. However, the degree of sequence conservation within the receptor-interacting residues, at the binding interface of the VEGFR-1 complexes as opposed to the VEGFR-2 complex, is rather minimal. Comparison of the amino acid sequences of VEGF-A, VEGF-B, and VEGF-C (structure-based alignment) shows that of the 19–22 residues contributed to the binding interface by these growth factors in their respective complexes only 3 amino acids are identical between all the ligands. VEGF-A and VEGF-C share 8 identical residues, and VEGF-B and VEGF-C share only 5 residues. Moreover, when the electrostatic potentials are mapped onto the protein surfaces (Fig. 2E), a considerable amount of dissimilarity is observed at the binding interface especially between the two receptors in question. The ligand-interacting region on VEGFR-2 seems to be dominated by mostly negative and neutral potentials, whereas the binding region on VEGFR-1 appears to be mostly basic. This distribution seems to tie up with the specificity/recognition profile of the different growth factors in the VEGF family. The binding interface on the VEGFR-1-specific ligands, VEGF-B and PlGF, is negatively charged (PlGF more so than VEGF-B), thereby reflecting their affinity for the basic VEGFR-1 interface. VEGF-A interface seems to be a combination of more neutral and less negatively charged residues. This duality seems to support the ability of VEGF-A to interact with both VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. On the other hand, the recognition of VEGFR-2 by VEGF-C is defined by the domination of basic residues at the binding interface of this growth factor. Because surface charge plays an important role in defining the mechanism of molecular recognition and protein-protein interactions, we believe that the structural insights we have gained from studying the differences in the electrostatic surface potentials highlight the reasons why VEGF-B shows a preference for only VEGFR-1 and not VEGFR-2.

Comparison with VEGF-B(10–108)·Fab-2H10 Complex

The VEGF-B-specific mAb 2H10 inhibits the biological activity of VEGF-B by preventing the growth factor from binding to VEGFR-1D2, thereby antagonizing receptor-mediated signaling (42). There is a striking resemblance between the binding sites of Fab-2H10 (32) on VEGF-B(10–108) and the binding sites of VEGFR-1D2 on VEGF-B(10–108) as observed from the present complex (Fig. 2B). The binding sites on the light and heavy chains of the variable domain of the antibody molecule co-localize with the VEGFR-1D2 determinants. In both complexes, the receptor-binding surface on the ligand appears as a contiguous segment, including residues contributed by both the monomers of VEGF-B(10–108). The Cα superposition of VEGF-B(10–108) from the two complexes results in an r.m.s.d of 1.4 Å over 170 Cα atoms. Similar superposition of native VEGF-B(10–108) with the receptor-bound and the antibody-bound ligand gives a structural displacement of 1.2 Å (over 181 Cα atoms) and 1.3Å (over 175 Cα atoms), respectively, indicating that the overall structure of the ligand in the two complexes is more similar to the native molecule than with each other. This could be a reflection of the significant displacement observed for 37–46 loop in both the complexes. In the present receptor-bound complex, this region does not form a part of the interface and is completely devoid of crystal packing interactions, resulting in differences even within the two monomers. However, in the antibody complex, this loop is arrested in the same conformation in both the monomers as the residues from the loop are involved in crystal packing with the Fab-2H10 molecule.

The 2H10 Fab molecule was shown to effectively block human VEFG-B(10–108) activity (42). The interacting segments in the two VEGF-B complexes are similar, but there are also several differences that become apparent when inspected at the residual level. The most notable difference between the two lies in the character of amino acids that make up the core of the interface. In the antibody complex (32), it was observed that the main contributors to the interface were the uncharged polar residues (50%). The rest of the interface was one-third charged (16.7%) in character and two-thirds nonpolar (33.3%). In the receptor-bound complex, however, the contribution is reversed with the nonpolar residues dominating the interface by contributing 54.5% of the residues. The bias toward tyrosine, serine, and threonine residues seen in the VEGF-B(10–108)·Fab-2H10 complex (32) is not observed in the VEGF-B(10–108)·VEGFR-1D2 interface. The interactions mediated by the aromatics in the receptor complex is almost half that seen for the antibody complex. Also, a total of nine hydrogen bonds mediate molecular recognition between the antigen and the antibody molecule, which is four less than those observed between the receptor and the ligand in the present complex. The large number of interactions mediated at the antigen-antibody interface is also a reflection of the difference in the size of VEGFR-1D2 when compared with Fab-2H10, the latter being almost three times the size. The present complex proves that the receptor and the antibody span the same expanse on the ligand surface and mediate comparable interactions at the interface with their binding partner. Hence, the neutralizing effect of the monoclonal antibody is brought about by steric hindrance and not via any induced-fit mechanism.

Heterodimerization, Functional Significance

The VEGF family is the most important contributor to angiogenesis. The occurrence of the different members of this family of growth factors and their isoforms implies a redundancy of functions for these angiogenic homodimers. This complexity is further increased when the different members form heterodimers with each other, reinforcing the notion that these dimeric complexes mediate partially overlapping cellular signals. Receptor specificity toward either VEGFR-1 and/or VEGFR-2 determines the role played by these polypeptides. However, not all these growth factors can recognize both these VEGF receptors. So, when VEGF-B or PlGF form heterodimers with VEGF-A, it is thought that they activate both the receptors simultaneously.

The structure of VEGF-C in complex with domains 2 and 3 of VEGFR-2 (41) has enabled us to model the VEGF-A/B heterodimer with VEGFR-1 (domain 2) at one interface and VEGFR-2 (domains 2 and 3) at the other interface (PDB code 2X1X (41)). The model revealed the asymmetric nature of the complex. The receptor-binding sites are composed of residues from two different monomers, indicating that the two sites may show preference for exclusive binding to either VEGFR-1 and or VEGFR-2. From our model, it appears that the putative contact residues are similar to those observed in all the complexes elucidated so far (including the present complex). However, a closer look at each of the receptor interfaces in the modeled complex, one for VEGFR-1 and the other for VEGFR-2, reveals that sequence conservation at the interface between VEGF-A and VEGF-B is not very high. The VEGFR-1-binding site is contributed by amino acids with either bulky or long side chains, most of which are hydrophobic in nature such as Phe-17, Tyr-21, Tyr-25, Leu-81, Ile-83, and Leu-90. The VEGFR-2-binding site on the other hand is mainly made up of amino acids with shorter side chains with the ability to make hydrogen-bonding interactions by virtue of their reactive groups. If, however, the two receptors swap the ends where they bind to the VEGF-A/B heterodimer, then the nature of the two binding sites also gets swapped. This then raises the question as to which receptor binds which of the two interfaces. It is possible that the orientation of the VEGFR-2-binding determinants on VEGF-A (Ile-46, Ile-83, and Lys-84) will have an important role in deciding where VEGFR-2 binds. It is likely that the differences manifest themselves via differential effects toward binding to VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. A detailed understanding of the versatility of these cysteine-knot proteins as a scaffold for recognition by both VEGFR-1 and VGEFR-2 will require further experimental structural studies.

Conclusions

Members of the VEGF family display functionally related structures despite high sequence variation. These molecules trigger their biological activities by binding two tyrosine kinase receptors, VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2. Although VEGF-A, the parent molecule of this family, has been quite extensively studied, the role of both VEGF-B and PlGF, molecules that interact solely with VEGFR-1, is rife with controversy. Therefore, it is essential to understand the exact nature of communication between the VEGF proteins and their receptors. This will help delineate the biological significance of the two tyrosine kinase receptor-mediated responses in angiogenesis and capitalize on the findings for therapeutics. Elucidation of the crystal structures of these ligands in complex with their binding partners is a step in this very direction. The structures determined until now highlight two interesting points. First, even though the Cα traces of these proteins align structurally, the functions are mutually exclusive. Second, the binding determinants need not be conserved to perform similar functions (as seen between VEGF-B and PlGF-1 complexes). Notwithstanding the gaps in our understanding of the mechanism of receptor recognition, the structures of the VEGFR-1D2-bound complexes provide a wealth of information on how subtle differences can potentially help this receptor discriminate between VEGF-A, PlGF, and VEGF-B. The present structure also highlights the complexity of interplay between VEGFR-1 and its ligands. Recent study on the unique role played by VEGF-B in regulating energy metabolism, mediated via VEGFR-1, further emphasizes the importance of this interaction. The study by Hagberg et al. (43) has opened up novel therapeutic avenues to study the role of this VEGFR-1-specific ligand in angiogenesis-mediated pathologies like diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular diseases. However, further structural and functional analyses through the use of receptor-selective VEGF-B mutants (as carried out for VEGF-A and PlGF) are essential to facilitate our comprehension of the important role played by VEGF-B.

Acknowledgments

We thank the scientists at Station I02, Diamond Light Source, Didcot (Oxon, UK) for their support during x-ray data collection. We thank Nethaji Thiyagarajan for help with data processing.

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (United Kingdom) Programme Grant 083191 and a Royal Society (United Kingdom) Industry Fellowship (to K. R. A.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2XAC) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- VEGF

- vascular endothelial growth factor

- VEGFR

- vascular endothelial growth factor receptor

- PlGF

- placenta growth factor

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- r.m.s.d.

- root mean square deviation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Folkman J., Shing Y. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 10931–10934 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folkman J. (1995) Nat. Med. 1, 27–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Otrock Z. K., Mahfouz R. A., Makarem J. A., Shamseddine A. I. (2007) Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 39, 212–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes D. I., Zachary I. (2005) Genome Biol. 6, 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamazaki Y., Morita T. (2006) Mol. Divers. 10, 515–527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuttfeld E., Ballmer-Hofer K. (2009) IUBMB Life 61, 915–922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otrock Z. K., Makarem J. A., Shamseddine A. I. (2007) Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 38, 258–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neufeld G., Lange T., Varshavsky A., Kessler O. (2007) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 600, 118–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mousa S. A. (2007) Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 33, 524–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olofsson B., Pajusola K., Kaipainen A., von Euler G., Joukov V., Saksela O., Orpana A., Pettersson R. F., Alitalo K., Eriksson U. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 2576–2581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lagercrantz J., Farnebo F., Larsson C., Tvrdik T., Weber G., Piehl F. (1998) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1398, 157–163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aase K., Lymboussaki A., Kaipainen A., Olofsson B., Alitalo K., Eriksson U. (1999) Dev. Dyn. 215, 12–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bellomo D., Headrick J. P., Silins G. U., Paterson C. A., Thomas P. S., Gartside M., Mould A., Cahill M. M., Tonks I. D., Grimmond S. M., Townson S., Wells C., Little M., Cummings M. C., Hayward N. K., Kay G. F. (2000) Circ. Res. 86, E29–E35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Detoraki A., Staiano R. I., Granata F., Giannattasio G., Prevete N., de Paulis A., Ribatti D., Genovese A., Triggiani M., Marone G. (2009) J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123, 1142–1149, 1149.e1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang F., Tang Z., Hou X., Lennartsson J., Li Y., Koch A. W., Scotney P., Lee C., Arjunan P., Dong L., Kumar A., Rissanen T. T., Wang B., Nagai N., Fons P., Fariss R., Zhang Y., Wawrousek E., Tansey G., Raber J., Fong G. H., Ding H., Greenberg D. A., Becker K. G., Herbert J. M., Nash A., Yla-Herttuala S., Cao Y., Watts R. J., Li X. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 6152–6157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunningham S. P., Currie M. J., Han C., Robinson B. A., Scott P. A., Harris A. L., Fox S. B. (2001) J. Pathol. 193, 325–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Louzier V., Raffestin B., Leroux A., Branellec D., Caillaud J. M., Levame M., Eddahibi S., Adnot S. (2003) Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 284, L926–L937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X., Aase K., Li H., von Euler G., Eriksson U. (2001) Growth Factors 19, 49–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karpanen T., Bry M., Ollila H. M., Seppänen-Laakso T., Liimatta E., Leskinen H., Kivelä R., Helkamaa T., Merentie M., Jeltsch M., Paavonen K., Andersson L. C., Mervaala E., Hassinen I. E., Ylä-Herttuala S., Oresic M., Alitalo K. (2008) Circ. Res. 103, 1018–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cao Y., Chen H., Zhou L., Chiang M. K., Anand-Apte B., Weatherbee J. A., Wang Y., Fang F., Flanagan J. G., Tsang M. L. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 3154–3162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olofsson B., Korpelainen E., Pepper M. S., Mandriota S. J., Aase K., Kumar V., Gunji Y., Jeltsch M. M., Shibuya M., Alitalo K., Eriksson U. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 11709–11714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Makinen T., Olofsson B., Karpanen T., Hellman U., Soker S., Klagsbrun M., Eriksson U., Alitalo K. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 21217–21222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoon Y. S., Losordo D. W. (2003) Circ. Res. 93, 87–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muller Y. A., Christinger H. W., Keyt B. A., de Vos A. M. (1997) Structure 5, 1325–1338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiesmann C., Fuh G., Christinger H. W., Eigenbrot C., Wells J. A., de Vos A. M. (1997) Cell 91, 695–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller Y. A., Chen Y., Christinger H. W., Li B., Cunningham B. C., Lowman H. B., de Vos A. M. (1998) Structure 6, 1153–1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen Y., Wiesmann C., Fuh G., Li B., Christinger H. W., McKay P., de Vos A. M., Lowman H. B. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 293, 865–881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuh G., Wu P., Liang W. C., Ultsch M., Lee C. V., Moffat B., Wiesmann C. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6625–6631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyer S., Leonidas D. D., Swaminathan G. J., Maglione D., Battisti M., Tucci M., Persico M. G., Acharya K. R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 12153–12161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iyer S., Scotney P. D., Nash A. D., Acharya K. R. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 359, 76–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Christinger H. W., Fuh G., de Vos A. M., Wiesmann C. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 10382–10388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonard P., Scotney P. D., Jabeen T., Iyer S., Fabri L. J., Nash A. D., Acharya K. R. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 384, 1203–1217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Collaborative Computational Project, No. 4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–76315299374 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scrofani S. D., Fabri L. J., Xu P., Maccarone P., Nash A. D. (2000) Protein Sci. 9, 2018–2025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramachandran G. N., Sasisekharan V. (1968) Adv. Protein Chem. 23, 283–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keyt B. A., Nguyen H. V., Berleau L. T., Duarte C. M., Park J., Chen H., Ferrara N. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5638–5646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davis-Smyth T., Presta L. G., Ferrara N. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 3216–3222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leppänen V. M., Prota A. E., Jeltsch M., Anisimov A., Kalkkinen N., Strandin T., Lankinen H., Goldman A., Ballmer-Hofer K., Alitalo K. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2425–2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scotney P. D., MacKenzie A., Maccarone P., Fabri L. J., Scrofani S. D., Gooley P. R., Nash A. D. (2002) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 29, 1024–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hagberg C. E., Falkevall A., Wang X., Larsson E., Huusko J., Nilsson I., van Meeteren L. A., Samen E., Lu L., Vanwildemeersch M., Klar J., Genove G., Pietras K., Stone-Elander S., Claesson-Welsh L., Ylä-Herttuala S., Lindahl P., Eriksson U. (2010) Nature 464, 917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kabsch W., Sander C. (1983) Biopolymers 22, 2577–2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]