Abstract

Cbl proteins are ubiquitin ligases (E3s) that play a significant role in regulating tyrosine kinase signaling. There are three mammalian family members: Cbl, Cbl-b, and Cbl-c. All have a highly conserved N-terminal tyrosine kinase binding domain, a catalytic RING finger domain, and a C-terminal proline-rich domain that mediates interactions with Src homology 3 (SH3) containing proteins. Although both Cbl and Cbl-b have been studied widely, little is known about Cbl-c. Published reports have demonstrated that the N terminus of Cbl and Cbl-b have an inhibitory effect on their respective E3 activity. However, the mechanism for this inhibition is still unknown. In this study we demonstrate that the N terminus of Cbl-c, like that of Cbl and Cbl-b, inhibits the E3 activity of Cbl-c. Furthermore, we map the region responsible for the inhibition to the EF-hand and SH2 domains. Phosphorylation of a critical tyrosine (Tyr-341) in the linker region of Cbl-c by Src or a phosphomimetic mutation of this tyrosine (Y341E) is sufficient to increase the E3 activity of Cbl-c. We also demonstrate for the first time that phosphorylation of Tyr-341 or the Y341E mutation leads to a decrease in affinity for the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (E2), UbcH5b. The decreased affinity of the Y341E mutant Cbl-c for UbcH5b results in a more rapid turnover of bound UbcH5b coincident with the increased E3 activity. These data suggest that the N terminus of Cbl-c contributes to the binding to the E2 and that phosphorylation of Tyr-341 leads to a decrease in affinity and an increase in the E3 activity of Cbl-c.

Keywords: E3 Ubiquitin Ligase, Tyrosine-protein Kinase (Tyrosine Kinase), Ubiquitin-conjugating Enzyme (Ubc), Ubiquitin Ligase, Ubiquitination, Cbl Proteins, Cbl-c

Introduction

Cbl proteins are a highly conserved family of proteins that regulate signal transduction through many pathways (1–3). They function as ubiquitin ligases (E3s),3 generally targeting activated tyrosine kinases (TKs) and kinase-associated proteins for degradation (3). In mammals, there are three family members: Cbl (c-Cbl, Cbl2, and RNF55), Cbl-b (RNF56), and Cbl-c (Cbl-3, Cbl-SL, and RNF57) (4–9).4 Cbl proteins are characterized by their highly conserved N terminus consisting of a tyrosine kinase binding (TKB) domain, a linker region, and a RING finger (RF) domain (10). The TKB domain is composed of a 4-helix bundle, an EF-hand calcium binding motif, and a variant Src homology 2 (SH2) domain (10). The TKB is responsible for binding specific phosphorylated tyrosines on the substrate. The RF domain is the catalytic region responsible for the ubiquitin ligase activity of the protein (11, 12). The TKB and RF are joined by a small α helical region known as the linker. All three mammalian Cbl proteins have a conserved proline-rich (PR) domain believed to be involved in SH3 domain interactions. Cbl proteins function by specifically ubiquitinating activated TKs that are involved in cellular signaling pathways and mediating down-regulation of these TKs (13–20).

The function of Cbl proteins as regulators of TK signaling is, in large part, based on their E3 activity. Cells have evolved intricate ways to control substrate-specific ubiquitination by modulating the levels, activities, and subcellular localization of the E3s (21, 22). Regulation of Cbl function occurs at several levels. Binding to specific substrates via the TKB, PR, and/or the phosphorylated tyrosines in the C terminus of Cbl dictates substrate specificity for ubiquitination by Cbl proteins (23). In many instances, the Cbl proteins bind via the TKB to phosphorylated tyrosines on the target TK thus selecting the activated TK. For example, Cbl proteins bind to Tyr(P)-1045 on the activated EGFR and to Tyr(P)-1003 on the activated MET receptor tyrosine kinase (13, 24). In addition, phosphorylation of Cbl on a linker tyrosine by the interacting kinase is essential to E3 activity. Early studies showed that the ability of Cbl to ubiquitinate and down-regulate activated EGFR was impaired when a critical tyrosine within the linker region was mutated to phenyalanine (25). Further studies showed that deletion of the linker tyrosine of Cbl impaired E3 function and resulted in transforming forms of Cbl (26). This result demonstrated the importance of the linker tyrosine in the activation and regulation of the Cbl protein function. Work by Kassenbrock and Anderson (27) showed that the E3 activity of Cbl and Cbl-b is negatively regulated by the N terminus. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the linker tyrosine in Cbl resulted in a conformational change in the protein and a concomitant increase in ubiquitination (27). However, the mechanism by which this conformational change leads to an increase in E3 activity is unknown.

Although Cbl and Cbl-b have been well studied and characterized, less is known about Cbl-c. Cbl-c is the only family member expressed exclusively in epithelial tissues, whereas both Cbl and Cbl-b are widely expressed in mammalian tissues (4). Like Cbl and Cbl-b, the N terminus of Cbl-c is composed of the highly conserved TKB, RF, and linker regions. The C terminus of the protein diverges from the other two Cbl proteins. The PR domain is shorter and has a relatively limited SH3 protein interacting profile compared with the other Cbl proteins (4). Like Cbl and Cbl-b, Cbl-c is a functional E3, which has been shown to ubiquitinate and down-regulate the EGFR, v-Src, and RET in vivo (16, 25, 28–30). Although the E3 activity of Cbl-c has been shown to be affected by phosphorylation by v-Src, there are no studies of the inhibition of Cbl-c E3 activity by the N terminus. In this article we show that, like Cbl and Cbl-b, Cbl-c E3 activity is negatively regulated by its N-terminal TKB, and we map this region further to the EF-hand and SH2 domain. Like the other Cbl proteins, phosphorylation of the linker tyrosine of Cbl-c is necessary and sufficient for activation of the E3 activity. Importantly, we found that phosphorylation of the linker tyrosine by Src lowers the affinity of Cbl-c for the E2 UbcH5b and allows more rapid turnover of the E2. Together, our data suggest that the N-terminal of Cbl-c regulates the affinity of the E3-E2 interaction and that the phosphorylation-induced decrease in affinity is associated with increased E3 activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

Isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactoside and Zeocin were obtained from Invitrogen. Glutathione-Sepharose 4B was purchased from Amersham Biosciences. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and Luria-Bertani (LB) broth was purchased from KD Medical (Columbia, MD). Lysozyme and N-lauroyl sarcosine were purchased from Sigma. CAPS buffer was purchased from Protea Biosciences (Morgantown, WV). Imidazole was purchased from GE Healthcare. Tissue culture plasticware and other laboratory consumables were purchased from commercial sources.

Antibodies

Anti-ubiquitin (Z0458) was obtained from DAKO North America, Inc. (Carpinteria, CA). Anti-biotin (857.060.000) was obtained from Gen-Prove Diaclone SAS (Besançon, France). Horseradish peroxidase-linked donkey anti-rabbit and horseradish peroxidase-linked donkey anti-mouse were obtained from GE Healthcare. Anti-GST (Sc-138), anti-Cbl-c (Sc-8372), and horseradish peroxidase-linked rabbit anti-goat were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-Src (05-889) and anti-phosphotyrosine (16-105) were obtained from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Anti-phospho-Src (2101) was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA).

Expression Constructs

Site-directed mutagenesis using the QuikChange Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used to create the following constructs: GST-Cbl-c Y341E, Y341F, Y341, and Y0 and GST-Cbl-b Y363E. The GST-tagged Cbl-c WT construct was created by PCR with 5′ BamHI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sequences on the primer oligonucleotides. The PCR products were cloned into pGEX-4T-2. The GST-tagged Cbl-c RF (aa 331–421) and Cbl-c ΔNT (aa 331–474) and GST-tagged Cbl-b N1/2 (aa 29–483) were created by PCR with 5′ BamHI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sequences on the primer oligonucleotides and cloned into pGEX-5X-1. The GST-tagged Cbl-c Short, ΔCT (aa 1–421), NT (aa 112–421), NT2 (aa 222–421), NT3 (aa 277–421), and NT4 (aa 307–421) constructs were created by PCR with 5′ BamHI and 3′ EcoRI restriction sequences on the primer oligonucleotides and cloned into pGEX-6P-1. pGEX-4T-1, pGEX-5X-1, and pGEX-6P-1 were purchased from Amersham Biosciences. GST-tagged Cbl-c internal deletions (ID) (Δaa 222–306), ID2 (Δaa 147–260), and ID3 (Δaa 147–306) were created by individual PCR of the N- and C-terminal portions of the construct in the first cycle of PCR. Flanking oligonucleotides were used to amplify the combined products from the first amplifications and the products were cloned into pGEX-6P-1. His-tagged Cbl-c and Cbl-c Y341E were each created by PCR of the entire open reading frame and by subsequent cloning of the PCR product into pTrc-HisA vector at the XhoI and HindIII sites. pTrc-HisA was purchased from Invitrogen. pETb-UbcH5b was a provided by Dr. Allan Weissman. All of the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Production and Purification of GST Proteins

Bacterial expression vectors were transformed in Rosetta bacteria using heat shock. Selected colonies were grown in LB broth with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin and 50 μg/ml of chloramphenicol for selection. For GST-Cbl-c RF and GST-Cbl-c RF C351A, GST-Cbl-c C366A and GST-Cbl-c ΔNT constructs were grown in 10-ml overnight cultures diluted 1/10 in 90 ml of LB and grown at 37 °C for 1 h. Cultures were stimulated with 2 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside and grown at 37 °C for 4 h. For all other recombinant GST-tagged proteins, 100-ml overnight cultures were diluted 1/10 in 900 ml of LB and grown at 16 °C for 4 h. Cultures were stimulated with 2 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactoside and grown at 16 °C overnight. Cell pellets were resuspended in 5 ml of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 5 mm dithiothreitol, pH 8), sonicated, and clarified by centrifugation. A 50% slurry of 300 μl of glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Amersham Biosciences) was added to clarified lysate and incubated with rocking overnight at 4 °C. Beads were pelleted by centrifugation and washed 5 times in lysis buffer and then 5 times in cold PBS. Beads were resuspended to 50% slurry in PBS for storage.

Production and Purification of His Proteins

Bacterial expression vectors were transformed in Rosetta bacteria using heat shock. Selected colonies were grown in LB broth with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin selection. All His constructs were grown in 100-ml overnight cultures diluted 1/10 in 900 ml of LB and grown at 37 °C for 1 h. Cultures were stimulated with 2 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside and grown at 37 °C for 4 h. The culture was separated into 100-ml aliquots and pelleted by centrifugation. Extraction of His-tagged proteins from insoluble pellets was modified from previous reports (31). Cell pellets were resuspended in 10 ml of sonication buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 0.3 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mg/ml of lysozyme) and incubated for 30 min on ice. Resuspended pellets were sonicated for 12 s, 12 times total, and transferred to 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min. Supernantants were pooled and saved. The His-tagged Cbl-c proteins were contained in the insoluble pellet. The individual pellets were washed three times in wash buffer (20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 1% Triton X-100, and 5 mm EDTA) with centrifugation at 10,000 × g at 4 °C for 15 min between washes. Pellets were combined and solubilized in 1 ml of lysis buffer (0.3% N-lauroyl sarcosine, 50 mm CAPS buffer, pH 11.0, 0.3 m NaCl) at room temperature, rotated for 20 min, and centrifuged 15 min at 10,000 × g. The supernatant was removed and any remaining pellet was resuspended and treated as described above until no pellet remained after centrifugation. Combined supernatants were incubated with a 1-ml slurry of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid resin previously washed with lysis buffer (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and rocked at 4 °C. The combined resin and sample were applied to a column, washed twice with lysis buffer plus 5 mm imidazole, once with 20 mm imidazole, and eluted with 200 mm imidazole. Samples were evaluated by SDS-PAGE and staining with GelCode Blue protein staining (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Proteins were dialyzed into 50 mm BisTris, pH 6.0, 20 mm NaCl, 10 μm ZnCl using Fast Dialyzer chambers and RCIK membranes from Harvard Apparatus (Holliston, MA).

Production and Purification of Ubch5b

Bacterial expression vectors were transformed in Rosetta bacteria using heat shock. Selected colonies were grown in LB broth with 100 μg/ml of ampicillin selection. All His constructs were grown in 100-ml overnight cultures diluted 1/10 in 900 ml of LB and grown at 37 °C for 1 h. Cultures were stimulated with 2 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside and grown at 37 °C for 4 h. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in 0.5× PBS and sonicated to lyse. Lysed cells were centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant was collected and run through a Hi Trap Q HP 5-ml anion exchange column (GE Healthcare). The Ubch5b was collected in the flow-through, which was concentrated and loaded onto a Hi Prep 16/60 Sephacryl S-100 HR sizing column (GE Healthcare) and exchanged into 1× PBS. Fractions containing Ubch5b were collected and assayed for concentration.

In Vitro E3 Assay

In vitro E3 assays were performed in 30-μl reactions containing 50 mm Tris-HCl, 0.2 m ATP, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol, and 1 mm phosphocreatine di(tris)salt (Sigma), 15 units of creatine phosphokinase (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), 50 ng of purified recombinant rabbit ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1, EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), 0.5 μg of ubiquitin (Boston Biochem, Cambridge, MA), and 1 μl of a crude bacterial lysate overexpressing recombinant human UbcH5b (E2) or 200 nm recombinant purified ubch5b. An estimated 15–20 nm GST-tagged Cbl proteins bound to GSH-Sepharose beads were added to the reaction and assays were performed at 30 °C, with shaking at 1000 rpm. Incubation time was 1 h unless stated otherwise. Reactions were stopped by addition of SDS-PAGE protein loading buffer and boiling for 5 min. Where stated, 100 ng of active Src (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) were added to the reaction. Where stated, 0.33 mm PP2 (EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) was used to inhibit Src activity in the reaction. The proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran BA85; Whatman). Samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-ubiquitin and anti-biotin. Horseradish peroxidase-linked donkey anti-rabbit and horseradish peroxidase-linked donkey anti-mouse or rabbit anti-goat immunoglobulin was used with SuperSignal (Pierce Biotechnology Inc.) to visualize the blots. Where indicated, densitometry was performed using Scion Image software and analyzed using Graphpad Prism 5.

E2/E3 Binding

Tryptophan fluorescence readings were measured on a PerkinElmer LS 55 luminescence spectrometer using FL Winlab software from PerkinElmer Life Sciences. Excitation wavelength was set to 280 nm and emission wavelength was set to 355 nm. The excitation slit was set to 3.2 and the emission slit to 5.0. Increasing amounts of recombinant purified Ubch5b were titrated into the recombinant purified Cbl-c proteins kept constant at 0.5 μm. Emission readings for each individual protein at the equivalent concentrations was subtracted from the bound E3/E2 emission readings. The absolute values of the differences were normalized to the highest value in each data set and plotted against the concentration of UbcH5b. An average of six experiments was analyzed in Graphpad Prism 5 using the algorithm for single site binding with Hill slope.

RESULTS

N Terminus of Cbl-c Reduces E3 Activity in Vitro

Previous in vitro studies have demonstrated that the N termini of Cbl and Cbl-b regulate the E3 activity of these proteins (27, 32). Cbl-c is the most divergent of the three Cbl proteins. Across the N terminus and RF there is ∼60% identity compared with Cbl or Cbl-b. By contrast Cbl and Cbl-b share a greater than 90% identity across these regions (4). Thus, we first sought to determine whether the N terminus of Cbl-c regulates the E3 activity of Cbl-c. We investigated the E3 activity of Cbl-c using an in vitro E3 assay. In vitro E3 assays were performed using bacterially produced recombinant E1 (Ube1), recombinant E2 (UbcH5b), and a biotin-labeled ubiquitin (33). Recombinant GST-tagged Cbl-c proteins (Fig. 1A) were produced in bacteria and purified by affinity binding to GSH-Sepharose beads. E3 assays were performed with each of these proteins and a GST control. The relative activity of the proteins was determined by the size and intensity of the smear on an immunoblot using an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Full-length Cbl-c has weak E3 activity compared with the isolated RF of Cbl-c (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2 and 8). This suggests that some part of the Cbl-c full-length protein inhibits the E3 activity of the RF. Comparison of the E3 activity of the Cbl-c FL, ΔCT, ΔNT, and the Cbl-c RF proteins demonstrated that deletion of the N terminus of Cbl-c results in a dramatic increase of activity, whereas deletion of the C-terminal region of the protein does not affect the basal E3 activity (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2, 4, and 6). This finding is consistent with published reports that the N termini of Cbl and Cbl-b inhibit their E3 activities (27). In published work, Cbl and Cbl-b have strong E3 activity. To demonstrate that the N termini of Cbl and Cbl-b inhibit their E3 activity, the E3 assay had to be attenuated by shortening the reaction time and using low amounts of protein (27). However, under non-attenuated conditions, where a Cbl-b construct containing the N-terminal sequence through the RF (Cbl-b N1/2) has high E3 activity, Cbl-c is a relatively weak E3 (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 4 and 6). In contrast to the full-length Cbl-c protein, the isolated Cbl-c RF is as active as Cbl-b (Fig. 1C, compare lanes 6 and 8). This suggests that the N terminus of Cbl-c inhibits E3 activity to a greater degree than that of the N terminus of Cbl-b.

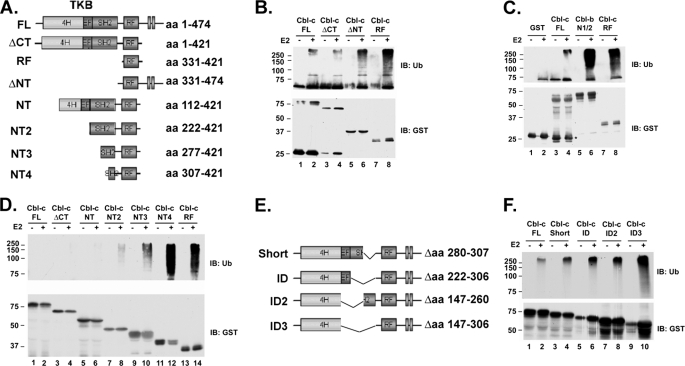

FIGURE 1.

Cbl-c E3 activity is inhibited by the N terminus of the protein. A and E, Cbl-c construct maps. All constructs were GST-tagged on the N terminus. B–D and F, in vitro E3 assays were performed in 50 mm Tris buffer with 0.2 mm ATP, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 mm phosphocreatine, 5 units of creatine phosphokinase, 50 ng of purified recombinant E1, 1 μl of recombinant Ubch5b crude lysate, 1 μg of purified recombinant ubiquitin, and the recombinant GST-Cbl-c constructs as labeled above the panel. Assays were performed at 30 °C for 1 h in the presence and absence of E2 to control for background not due to E3 activity and then immunoblotted (IB) as indicated. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown to the left of the panels. In panel B, the 25-kDa band in lanes 1–4 of the GST immunoblot represent truncated GST proteins that are present in the FL and ΔCT samples.

The EF-hand and SH2 Domains Inhibit E3 Activity

Although the previous work with Cbl and Cbl-b identified the N terminus of the proteins as a negative regulator of E3 activity, the domains responsible for this were not determined. To further characterize the region of the N terminus required to inhibit the E3 activity, a series of N-terminal deletions were created in the construct lacking the C terminus (Fig. 1A). Deletion of the N terminus of Cbl-c through the EF-hand (NT2) resulted in a slight increase in activity (Fig. 1D, lane 8). Deletion through the first 55 amino acids of the SH2 domain (NT3) increased activity further, and deletion through the first 85 amino acids of the SH2 domain (NT4) resulted in E3 activity similar to that of the isolated RF (Fig. 1D). To identify the minimal inhibitory region of the N terminus of Cbl-c, a series of internal deletions were made in Cbl-c (Fig. 1E). Cbl-c Short represents a naturally occurring splice variant that has a deletion of the second half of the SH2 domain of Cbl-c (4). Progressive increases in E3 activity can be seen with deletion of the second half of the SH2 domain (Fig. 1F, lane 4, Cbl-c Short), deletion of the entire SH2 domain (Fig. 1F, lane 6, ID) or deletion of the EF-hand and first half of the SH2 domain (Fig. 1F, lane 8, ID2). Deletion of the EF-hand and entire SH2 domain (ID3) leads to the greatest increase of E3 activity (Fig. 1F, lane 10, ID3). Together, these data define the EF-hand and SH2 domains as areas required for N-terminal inhibition of Cbl-c E3 activity. However, the level of activity in the ID3 construct is not equal to that of the isolated RF or CT constructs (data not shown). Thus, it is likely there are other regions that contribute to N-terminal inhibition.

Cbl-c E3 Activity Is Enhanced upon Phosphorylation of the Linker Tyrosine 341 by Active Src

Previous work indicates that phosphorylation of Cbl and Cbl-b by Src leads to an increase in E3 activity (27, 34). Similarly, Cbl-c can be phosphorylated when cotransfected with v-Src, and this phosphorylation leads to an increase in v-Src ubiquitination (16). However, the mechanism by which this occurs is still unknown. The in vitro E3 assay was used to determine more specifically how Src phosphorylation of Cbl-c can lead to an increase in activity. E3 assays were performed with GST-tagged Cbl-c FL in the presence and absence of activated Src. Incubation of Cbl-c with Src results in a significant increase in E3 activity (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 2 and 4). However, the increased E3 activity of Cbl-c in the presence of Src is not equal to that of the isolated RF (Fig. 2A, compare lanes 4 and 6). The reaction containing GST alone with Src and E2 had no measurable E3 activity (Fig. 2A, lane 8).

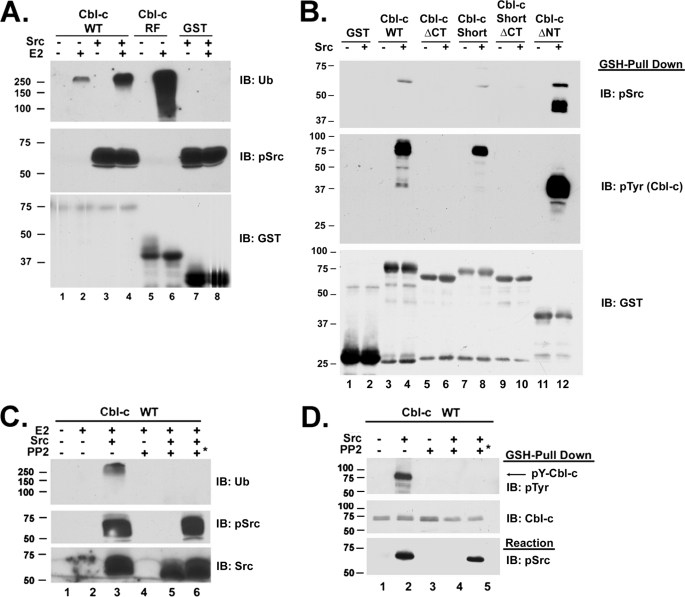

FIGURE 2.

Src binds to Cbl-c through the PR domain and increases Cbl-c E3 activity in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. A and C, in vitro E3 assays were performed as described in figure legend Fig. 1 using recombinant GST-Cbl-c constructs as labeled above the panel. 0.1 μg of recombinant purified active Src was added where indicated. Assays were performed for 1 h and immunoblotted (IB) as indicated. B and D, in vitro interaction between Src and GST-Cbl-c constructs were determined by incubating the proteins in the same buffer as the E3 assay described in the legend to Fig. 1 without E1, E2, and ubiquitin, followed by GSH pulldowns and immunoblotting as indicated. In panels C and D, the Src inhibitor PP2 was added to the reaction where indicated above the panel. PP2 was added concurrently with the active Src except in the last lane of each panel (lanes 6 and 5, respectively, indicated with an *), in which Src was incubated in the reaction mixture and allowed to autophosphorylate for 1 h prior to PP2 being added followed by the addition of Cbl-c. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown to the left of the panels.

To further characterize Src activation of Cbl-c E3 activity, the region of Cbl-c responsible for interacting with Src was determined. Because the TKB of Cbl-c can interact with phosphorylated tyrosines on Src and the PR domain of Cbl-c can interact with the SH3 domain of Src, constructs were utilized that disrupt or delete these regions individually or together. GST-tagged Cbl-c FL, Cbl-c Short (disrupted SH2 domain), Cbl-c ΔCT (deleted PR domain), Cbl-c Short ΔCT (disrupted SH2 and deleted PR domains), and Cbl-c ΔNT (lacking the entire TKB domain) were incubated with and without Src. Then the GST proteins were precipitated with GSH-Sepharose beads, washed, and immunoblotted with anti-GST, anti-phospho-Src, and anti-phosphotyrosine antibodies (Fig. 2B). All constructs containing the PR-rich domain of Cbl-c (Cbl-c WT, Cbl-c Short, and Cbl-c ΔNT) co-precipitated Src as indicated by the presence of phospho-Src in the top section of the panel (Fig. 2B, lanes 4, 8, and 12). By contrast constructs lacking the PR domain (Cbl-c ΔCT, and Cbl-c Short ΔCT, Fig. 2B, lanes 6 and 10) do not interact with Src. In all cases where Src can bind the Cbl-c proteins, those Cbl-c proteins are tyrosine phosphorylated (Fig. 2B, lanes 4, 8, and 12). This result shows that the interaction of activated Src and Cbl-c is mediated predominantly through the PR domain and not through the TKB domain.

Phosphorylation of Cbl-c by Src is dependent on interaction between the two proteins (Fig. 2B). To confirm that phosphorylation of Cbl-c was required for activation of Cbl-c a specific Src inhibitor, PP2, was utilized. When the inhibitor is added to the reaction at the beginning, PP2 abrogates autophosphorylation of Src, phosphorylation of Cbl-c (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 2 and 4), and the Src-induced activation of Cbl-c E3 activity (Fig. 2C, compare lanes 3 and 5). When Src was allowed to autophosphorylate and then PP2 added prior to addition of Cbl-c, phosphorylation (Fig. 2D, lane 5) and activation of the Cbl-c E3 activity were also abrogated (Fig. 2C, lane 6). This confirms that phosphorylation of Cbl-c by Src is necessary for activation of E3 activity. Previously, similar experiments demonstrated the requirement for Cbl phosphorylation by the activated EGFR (25).

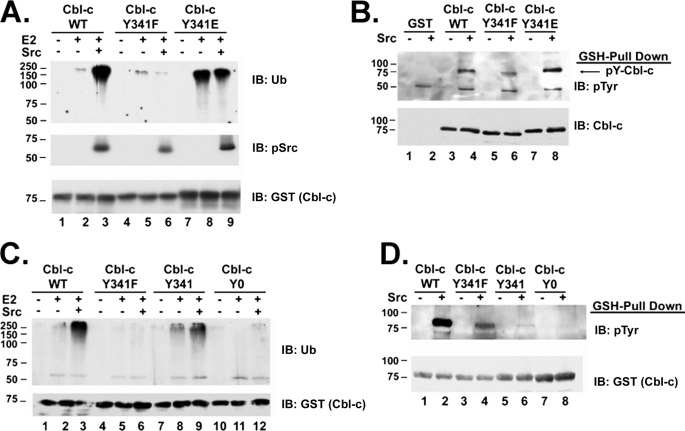

Phosphorylation of Tyrosine 341 of Cbl-c Is Necessary and Sufficient for Activation of Cbl-c E3 Activity

The TKB of Cbl proteins is separated from the RING finger by an α helical linker region (35). Early characterization of Cbl E3 activity implicated phosphorylation of the linker tyrosine in activation of E3 activity (25). In vitro work has demonstrated that Cbl is activated by phosphorylation of Tyr-371 located in the linker region between the TKB and the RF (27). Also, it has been shown that deletion of the corresponding tyrosine in Cbl-c, Tyr-341, can abolish the ability of Cbl-c to down-regulate vSrc (16). To further characterize the role of Tyr-341 in the activation of Cbl-c, a phosphomimetic mutant (Y341E) and a non-phosphorylatable mutant (Y341F) were generated in Cbl-c by site-directed mutagenesis. The Cbl-c wild type and Tyr-341 mutants were incubated with active Src to test whether Src enhanced the E3 activity. Similar to Cbl (27), mutation of Tyr-341 to glutamate leads to a dramatically higher E3 activity of Cbl-c. This activity is not altered by incubation with active Src (Fig. 3A, compare lanes 8 and 9 to lanes 2 and 3). The basal level of activity of Y341F is similar to Cbl-c WT but is unaffected by incubation with active Src (Fig. 3A, lanes 5 and 6). WT Cbl-c and Y341E mutant proteins are phosphorylated to similar levels by Src (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 4 and 8). Phosphorylation of Y341F by Src was only slightly reduced compared with WT Cbl-c (Fig. 3B, compare lanes 4 and 6). This indicates that there are additional sites of tyrosine phosphorylation in the GST-Cbl-c protein. To determine whether these other sites contribute to the activation of Cbl-c E3 activity by Src, site-directed mutagenesis was used to create mutant Cbl-c constructs where either all of the tyrosines were mutated to phenylalanine (Cbl-c Tyr-0) or where Tyr-341 was reintroduced as the only tyrosine in the protein (Cbl-c Tyr-341). The ability of Src to activate and phosphorylate Cbl-c WT, Y341F, Tyr-341, and Tyr-0 was tested. As above, the E3 activity of Cbl-c WT is increased when incubated with Src, whereas the activity of the Y341F mutant is not (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 3 and 6). Both proteins were phosphorylated by Src but again lower levels of tyrosine phosphorylation were seen when Y341F was incubated with Src (Fig. 3D, lanes 2 and 4). The E3 activity of the Cbl-c Tyr-0 mutant is not enhanced nor is it phosphorylated by incubation with active Src (Fig. 3C, lane 12 and 3D, lane 8). The lack of phosphorylation of Cbl-c Tyr-0 indicates that tyrosines on the GST fusion protein are not substrates for Src under these conditions. In contrast, the E3 activity of Cbl-c Tyr-341 is enhanced by Src to a similar degree as Cbl-c WT (Fig. 3C, compare lanes 2 and 3 to lanes 8 and 9). Cbl-c Tyr-341 is tyrosine phosphorylated by Src, although at a greatly reduced level compared with the WT or Y341F mutant (Fig. 3D, compare lane 6 to 2 and 4). These data show that although there are other sites of tyrosine phosphorylation, the phosphorylation of Tyr-341 of Cbl-c is necessary and sufficient for activation of Cbl-c E3 activity by Src.

FIGURE 3.

Src phosphorylation of Cbl-c at tyrosine 341 is necessary and sufficient for activation of E3 activity. A and C, in vitro E3 assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1 using recombinant GST-Cbl-c constructs as labeled above the panel. The assay was performed in the presence and absence of Src as indicated above the panel. B and D, in vitro phosphorylation assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 2 using recombinant GST-tagged Cbl-c constructs as labeled above the panel. The assays were performed in the presence and absence of Src as indicated above the panel. GSH pulldowns were performed and immunoblotted (IB) as indicated. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown to the left of the panels.

The N terminus of Cbl-c Inhibits E3 Activity by Increasing the Binding Affinity of Cbl-c to UbcH5b

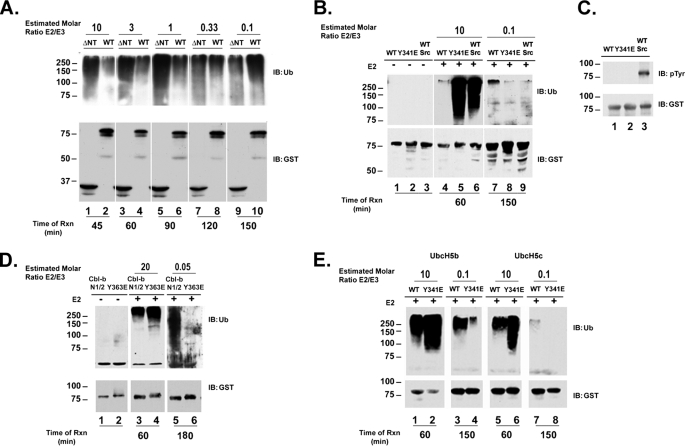

The data above demonstrate that the N terminus of Cbl-c lowers E3 activity and phosphorylation by Src increases that activity. RING finger E3s catalyze a direct transfer of ubiquitin from the thiol ester linkage on the E2 to the substrate without a covalent intermediate on the E3 (36). Thus the interaction between the RF and E2 is a critical factor in the rate of substrate ubiquitination. Recent work has shown that allosteric interactions can increase the affinity of the interaction between the RF and E2 and subsequently increase the rate of ubiquitination (37). To explore the mechanism by which the N terminus regulates E3 activity we began to measure the loss of ubiquitin from the E2 as a more proximal measure of E3 activity (a so-called E2-unloading assay). To be able to visualize the disappearance of ubiquitin-loaded E2 on an immunoblot, a greatly reduced concentration of E2 was used in the assay. (The previous assays had been done in ∼10-fold molar excess of E2 compared with E3.) An initial E2 ubiquitin unloading assay was performed using Cbl-c and Cbl-c ΔNT to determine optimal conditions. Surprisingly, in this preliminary assay we found that Cbl-c ΔNT, which yields a much higher activity in the E3 assays when E2 was in molar excess, unloads the ubiquitin from the E2 much less efficiently than the full-length proteins (data not shown). These data suggested that when the E2 is limiting in the reaction, the Cbl-c WT has a higher activity than Cbl-c ΔNT. To confirm this, an in vitro E3 assay was performed to compare activity of Cbl-c WT and Cbl-c ΔNT using decreasing concentrations of E2. Under conditions where the E2 is in a 10-fold molar excess of the E3, the Cbl-c ΔNT has a higher activity (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 1 and 2) consistent with the data presented in Figs. 1 and 2 above. As the E2/E3 ratio decreases the difference in E3 activity between Cbl-c WT and ΔNT decreases until, under conditions where the E2 is limiting, Cbl-c ΔNT has a lower activity compared with the full-length protein (Fig. 4A, lanes 9 and 10). As the E2 concentration was lowered, it was necessary to incubate the reactions for longer periods of time to see the E3 activity (Fig. 4A, see time of reaction listed below panels). Under limiting E2 conditions, the Cbl-c WT protein is a weak E3 but the relative activity of Cbl-c WT is significantly greater than that of Cbl-c ΔNT (Fig. 4A, compare lanes 9 and 10). To determine whether the relative activity of phosphorylated Cbl-c and the Cbl-c Tyr-341 phosphomimetic mutant is similarly affected by the E2 concentration, an E3 assay was performed with Cbl-c WT, Cbl-c WT phosphorylated by Src, and Cbl-c Y341E under conditions of excess and limiting E2. As seen above, phosphorylated Cbl-c WT and Cbl-c Y341E have higher activity than Cbl-c WT in the presence of excess E2 (Fig. 4B, compare lanes 5 and 6 to lane 4). When the reaction is incubated with limiting concentrations of the E2, Cbl-c WT has weak activity requiring a long incubation to see E3 activity. However, this activity is greater than the activity seen with the phosphomimetic mutant or Src-phosphorylated Cbl-c WT (Fig. 4B, compare lane 7 to lanes 8 and 9).

FIGURE 4.

Cbl-c WT has a higher E3 activity than Cbl-c ΔNT, phosphorylated Cbl-c, and Cbl-c Y341E when limiting E2 concentrations are used. A, in vitro E3 assays were performed as described in the legend to Fig. 1 with the exception that purified recombinant Ubch5b was used and we altered the E2 concentrations as noted. The recombinant GST-Cbl-c constructs used are labeled above the panel at an approximate concentration of 20 nm and E2 was added at the molar ratio indicated above the figure. Assays were performed in the presence of E2 in decreasing concentrations for each pair of reactions as noted above the panels. With decreased amounts of E2 the reactions were run at increased durations of time as labeled below the panel. The estimated molar ratio E2/E3 is listed above the panel. B, in vitro E3 assays were performed using recombinant GST-Cbl-c, Cbl-c Y341E, and GST-Cbl-c incubated with active Src prior to addition to the assay as labeled above the panel. The assays were performed with 200 nm E2 (10:1, E2:E3 ratio) or 2 nm E2 (0.1:1, E2:E3 ratio) as indicated above the panel and the corresponding reaction times labeled below the panel. B, GST-Cbl-c WT was incubated with or without Src prior to the addition to the E3 assay. C, to assess phosphorylation of Cbl-c by Src, protein, an aliquot of the proteins used in the E3 assay was immunoblotted for Tyr(P). D, in vitro E3 assays were performed with Cbl-b N1/2 and GST-Cbl-b Y363E as labeled above the panel at a concentration of 10 nm. The assays were performed with 200 nm E2 (20:1, E2:E3 ratio) or 0.5 nm E2 (0.05:1, E2:E3 ratio) as indicated above the panel and the corresponding reaction times labeled below the panel. E, in vitro assays were performed with GST-Cbl-c or GST-Cbl-c Y341E and either Ubch5b or Ubch5c as indicated above the panel. Assays were performed with the relative E2:E3 ratio as indicated above the panel and the corresponding reaction time as indicated below the panel. Assays were immunoblotted (IB) as indicated. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown to the left of the panels.

Previous work has demonstrated that the N terminus of Cbl and Cbl-b inhibits the E3 activity of these proteins and that a phosphomimetic mutation in the linker tyrosine equivalent to Tyr-341 of Cbl-c enhances the activity (27). These experiments were carried out at an excess of E2 relative to the E3. We assayed the E3 activity of Cbl-b and Cbl-b Y363E at high and limiting E2 concentrations to determine whether Cbl-b behaved like Cbl-c under these conditions. At high E2 concentrations, Cbl-b WT is less active than the phosphomimetic mutant Cbl-b Y363E (Fig. 4D, compare lanes 3 to 4). At a low E2 concentration, the Cbl-b WT construct was more active than the phosphomimetic mutant (Fig. 4D, lanes 5 and 6). Thus Cbl-b shows the same change in relative E3 activity at low E2 concentrations that is seen with Cbl-c.

To determine whether this shift in relative E3 activity was unique to Ubch5b, the E3 activity of Cbl-c was tested with a panel of E2s including Ubch5a, Ubch5b, Ubch5c, UbcH7, Ubc3, E2–25K, Ubc13, and E2-20K. Activity was only seen with UbcH5a, -b, and -c (data not shown). To test whether the E2 concentration-dependent shift in Cbl-c E3 activity was seen with another E2, we performed E3 assays using UbcH5c in excess and limiting conditions. Like with Ubch5b, Cbl-c WT has a lower activity than the phosphomimetic Y341E mutant when Ubch5c is in excess (Fig. 4E, compare lanes 5 and 6). At low concentrations of Ubch5c, Cbl-c WT is more active than Cbl-c Y341E (Fig. 4E, compare lanes 7 and 8).

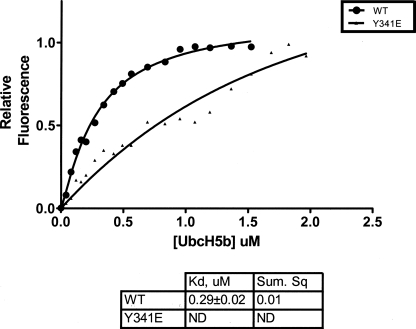

The transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate (in this case the E3 itself) can be divided into an E2/E3 binding step, followed by a catalytic step. When the E2 is in excess, the binding step is not limiting and the rate of ubiquitination is measured by the catalytic step. When the E2 concentration is lower, the binding step becomes limiting to the rate of transfer. Cbl-c WT has a higher activity compared with Cbl-c ΔNT or the phosphomimetic Cbl-c Y341E mutant when the E2 is limiting. The higher activity of Cbl-c WT compared with the mutants at low E2 concentrations suggests that Cbl-c WT binds the E2 with a higher affinity than either Cbl-c ΔNT or Cbl-c Y341E. We first attempted to measure the relative affinities between Cbl-c constructs and UbcH5b using pulldown assays but we were unable to co-precipitate the E2 with any Cbl-c construct (data not shown). This result is consistent with a low affinity interaction between Cbl-c and the E2, as has been reported for other RING finger E3-E2 interactions (37, 38). To measure the affinities between Cbl-c constructs and UbcH5b, we measured the binding of Cbl-c WT and Cbl-c Y341E to the E2, UbcH5b, using differential tryptophan fluorescence. The amount of Cbl-c proteins was kept constant as increasing amounts of Ubch5b were added. Samples were excited at 280 nm and emission readings were taken at 335 nm in triplicate. Both Cbl-c and UbcH5b have intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence, which is quenched upon interaction of the two proteins. Emission readings from the bound E3-E2 complex was subtracted from the sum of the emission readings for each individual protein at the equivalent concentrations. The values of the differences were normalized and plotted against the concentration of UbcH5b. An average of six experiments was analyzed in Graphpad Prism 5 using the algorithm for single site binding with Hill slope. Cbl-c WT demonstrated saturable binding to UbcH5b with a Kd of 0.29 ± 0.02 μm (Fig. 5). We were unable to determine a Kd when these experiments were repeated with Cbl-c Y341E as the fluorescence reached the maximum levels that the fluorimeter could measure before saturation was reached. Assuming that the mutant may have been close to saturation, these measurements would predict a minimum Kd of 0.97 ± 0.018 μm based on these results. Thus the phosphomimetic mutant would bind the E2 with at least a 3.37-fold lower affinity. However, the data do not indicate that saturation was reached, so the likely Kd for the phosphomimetic mutant is higher than 0.97 μm.

FIGURE 5.

Cbl-c WT binds to UbcH5b with a higher affinity than activated Y341E mutant. Purified UbcH5b was titrated into purified His-Cbl-c (closed circle) or His-Cbl-c Y341E (closed triangles). The adjusted tryptophan fluorescence of each was plotted and analyzed with a single site binding algorithm with Hill slope to determine Kd. A Kd for Cbl-c Y341E could not be determined due to a failure to reach saturation.

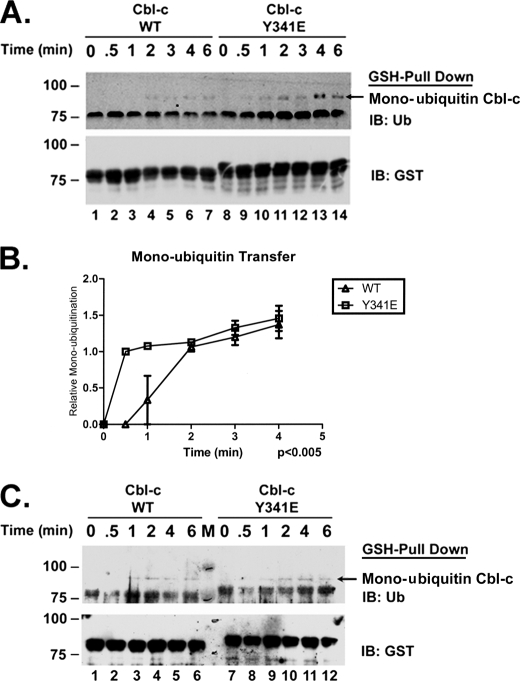

Ubiquitination as measured in the gel-based assay requires multiple cycles in which the E3 binds an ubiquitin-loaded E2, transfers the ubiquitin to the substrates, and then releases the unloaded E2 (39). The E3 is then free to bind another ubiquitin-loaded E2 and repeat the process. The higher affinity of Cbl-c WT for the E2 compared with the phosphomimetic mutant suggests that the lower activity of the WT protein is due to a slower release of the unloaded E2. This slower release would inhibit binding of an ubiquitin-loaded E2 and lower the rate of ubiquitination. To test whether the rate of release is responsible for the differing activity of the two proteins, we performed a time course experiment first incubating Cbl-c WT and Cbl-c Y341E with a catalytically dead mutant E2 (Ubch5b C85A), which is unable to be loaded with ubiquitin (38). E2 WT was loaded with lysine-null ubiquitin (K0 ubiquitin) for 1 h prior to the addition of the Cbl-c proteins. After the addition of the ubiquitin-charged E2 to the E3 proteins that had been incubated with mutant E2, time points were collected at 30 s, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6 min. The E3s were bound to GSH-Sepharose beads, centrifuged, washed at each time point, and analyzed by immunoblots with anti-ubiquitin antibodies. The transfer of the ubiquitin under these conditions would require the release of the mutant E2 so that the protein could bind the ubiquitin-loaded E2. The appearance of the monoubiquitinated species appears earlier with Cbl-c Y341E, (0.5 min) than Cbl-c WT (2 min) (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 4 and 9). Data from three experiments are quantified in Fig. 6B. Because the release of an uncharged mutant E2 would be required for the E3 interaction with a ubiquitin-charged E2 necessary for ubiquitin transfer, these data indicate that the Y341E mutant releases the E2 faster than the WT Cbl-c. These data are consistent with the higher affinity of WT Cbl-c for the E2 as determined in Fig. 5.

FIGURE 6.

Catalytically dead E2 inhibits Cbl-c WT E3 activity more than Cbl-c Y341E activity. In vitro E3 assays were performed using recombinant GST-tagged Cbl-c constructs as labeled above the panel. Assays were performed in the presence of ubiquitin-loaded E2 WT and were terminated at the times indicated above the panel. GSH pulldowns were performed and the beads washed and immunoblotted (IB) as indicated. Arrow indicates monoubiquitinated GST-Cbl-c. A, Cbl-c proteins were incubated with catalytically dead UbcH5b C85A prior to being added to the reaction. Assays were performed in the presence of equimolar UbcH5b WT and the C85A mutant. B, experiments as shown in panel A were quantified by densitometry for the relative Cbl-c monoubiquitination for WT and Y341E in the presence of UbcH5b C85A. The intensity of band at the earliest time point was set to a value of 1, and the subsequent intensities are relative to that time point. Data are the mean of three experiments ± S.E. C, assays were performed in the absence of catalytically dead UbcH5b C85A. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown to the left of the panels.

To test whether the phosphomimetic mutation affects the rate of ubiquitin transfer in addition to E2 turnover, an E3 assay time course was repeated using K0 ubiquitin without initially incubating the E3 with a catalytically dead E2. A molar excess of E2 WT was loaded with K0 ubiquitin for 1 h prior to the addition of the E3. Time points were collected at 30 s 1, 2, 4, and 6 min and treated as previously described. A monoubiquitinated species for both Cbl-c WT and Cbl-c Y341E first appears at 1 min (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 3 and 9). Thus, the rate at which the initial ubiquitin is transferred from the ubiquitin-loaded E2 to the Cbl-c protein is similar for both WT and Y341E proteins.

DISCUSSION

The ability of Cbl proteins to regulate TK signaling is largely dependent on their ability to transfer ubiquitin to their substrates. Published work has demonstrated that the N termini of Cbl and Cbl-b negatively regulate their E3 activity and that phosphorylation of a tyrosine in the linker region, (Tyr-371 in Cbl) can enhance the E3 activity of the Cbl protein (27). This phosphorylation results in a conformation change of the proteins, demonstrated by protease sensitivity (27). The region within the TKB responsible for the negative regulation of Cbl E3 activity was not determined further in these studies and the mechanism by which phosphorylation alters activity was not elucidated.

There have been no such studies for Cbl-c. In this work we have shown that, like the other human Cbl proteins, the E3 activity of Cbl-c is negatively regulated by the N-terminal TKB. Further analysis by our work has shown that a region composed of the EF-hand and the SH2 domains of Cbl-c is primarily responsible for this decreased activity (Fig. 1). Similar to the activation of Cbl, we have demonstrated that activation of Cbl-c by Src requires that Src phosphorylate Cbl-c on the linker tyrosine (Tyr-341). Furthermore, we show that phosphorylation of this tyrosine is necessary and sufficient to increase the E3 activity of the Cbl-c protein (Figs. 2 and 3). In our studies, we found that activated Src requires the PR region of Cbl-c for their interaction and the subsequent phosphorylation of Cbl-c. This interaction is presumably mediated by the SH3 domain of Src (Fig. 2). The interaction was independent of the TKB domain as Cbl-c constructs with disruption or deletion of the TKB interacted with and were phosphorylated and activated by Src (Fig. 2). Furthermore, Cbl-c proteins with an intact TKB but deletion of the PR region failed to interact with Src and were not phosphorylated or activated by Src (Fig. 2). Published work investigating the interaction between v-Src and Cbl-c in cell lysates found that the interaction is mediated by the TKB domain of Cbl-c (16). However, the work presented here used activated human Src in the absence of other cellular proteins. This may account for the differences seen in the two studies.

It is likely this inhibition of E3 activity by the N terminus is due in part to the interaction of the TKB with the linker tyrosine, Tyr-341 in Cbl-c. The linker region separates the TKB domain of Cbl proteins from the RING finger and is a conserved α helical region of 36 amino acids (35). Although Cbl and Cbl-b have two conserved tyrosines within the linker, Cbl-c has only one tyrosine (35). The tyrosine common to all three proteins (Tyr-371 in Cbl, Tyr-363 in Cbl-b, and Tyr-341 in Cbl-c) is critical for the activation of E3 activity (Figs. 3 and 4) (16, 25, 27). The published crystalline structure of Cbl has shown that the homologous tyrosine (Tyr-371) on Cbl is hydrogen-bonded to two amino acids, one within the SH2 domain and one within the EF-hand. The N-terminal, linker, and RING finger of Cbl-c can be modeled on the reported structure of Cbl (data not shown). Based on this modeling, the linker tyrosine of Cbl-c is hydrogen bonded to threonine 197 in the EF-hand and tryptophan 228 in the SH2 domain. It has been suggested that this would make the linker tyrosine poorly accessible to Src for phosphorylation (40). Consistent with data for Cbl (25, 27), we have shown that despite the predicted poor accessibility, phosphorylation of Tyr-341 is both necessary and sufficient for activation (Figs. 2 and 3). Introduction of the negative charge by phosphorylation of this tyrosine would disrupt the hydrogen bonding between the linker tyrosine and the residues in the EF-hand and SH2 domains. Also, modeling based on the crystal structure predicts that the charged group would prevent folding of the protein to position the linker and TKB in close proximity as in the unphosphorylated state. The study by Kassenbrock and Anderson (27) demonstrated that phosphorylation of Tyr-371 of Cbl, or the phosphomimetic mutation Y371E resulted in a conformational change as measured by protease sensitivity. It is likely that a similar change in confirmation results in Cbl-c upon phosphorylation of Tyr-341.

To further elucidate how the N-terminal region regulates the E3 activity of Cbl-c, we investigated the effect of the N terminus and the phosphomimetic mutation of the linker tyrosine on the interaction between Cbl-c and the E2 UbcH5b. Under conditions where the UbcH5b is in excess, proteins lacking the N-terminal or have a phosphomimetic Y341E mutation are more active than the wild type protein (Fig. 4). In contrast, when UbcH5b is limiting the wild type protein is more active than the mutant protein. This switch in concentration dependence is also seen when we use Cbl-b or the Y363E phosphomimetic mutant of Cbl-b suggesting it is a general property of Cbl proteins. We also found that a second E2, UbcH5c behaves similarly to UbcH5b.

These results indicate that the unphosphorylated wild type protein has a higher affinity for the E2 than either of the two mutants. We confirmed this by directly measuring the binding of the wild type and Y341E proteins with UbcH5b (Fig. 5). Using increases in tryptophan fluorescence that occur upon the interaction of Cbl-c with the UbcH5b, we found that the Kd = 0.29 ± 0.02 μm. In contrast, we were not able to reach saturation of binding between UbcH5b and the Y341E mutant Cbl-c. Based on this result, the Kd for the phosphomimetic mutant would be a minimum of 0.98 μm. This is likely to be an underestimate of the Kd between the Y341E mutant and UbcH5b. Thus, the N terminus of Cbl-c contributes to the binding of Cbl-c to the E2 and the phosphorylation of the linker tyrosine (or a phosphomimetic mutation) results in at least a 3-fold lowering of the affinity between the Cbl-c protein and the E2. The reported crystalline structure of Cbl and UbcH7 indicates that there are two hydrogen bonds formed between the E2 and linker region of Cbl. As introduction of a charged group on the linker tyrosine of the protein alters the conformation of the N terminus (27), it is likely that the linker region can no longer form these H-bonds after phosphorylation. This is a likely explanation for the lower binding affinity between the Y341E phosphomimetic mutant of Cbl-c and UbcH5b.

The interaction between the RING of RF E3s and the E2 has been found to be a weak interaction with Kd values typically greater than 100 μm. For example, the Kd between the RF E3 CNOT4N and UbcH5b under conditions of which there is significant E3 activity was determined to be ∼110 μm (38). Similarly, recent work investigating interaction of the RF E3 GP78 with the E2 Ube2g2 under conditions where there is significant E3 activity has demonstrated a Kd of 144 μm for this interaction (37). The catalytic activity of GP78 is enhanced by an allosteric interaction of a second E2 binding domain of GP78 with the backside of Ube2g2. When the activity is enhanced the Kd is decreased ∼48-fold to 3 μm (37). Interestingly, binding of the non-phosphorylated wild type Cbl-c protein with UbcH5b has a Kd that is ∼10-fold lower than that of the very active GP78 and Ube2g2 in the presence of the peptide. The Y341E phosphomimetic mutation in Cbl-c results in a significantly higher Kd that approaches the lowest values reported for GP78.

The E2 interacts with the RF domain through the same surface that it interacts with the E1, making it impossible for an E2 to be recharged with ubiquitin while bound to an E3 (39). Thus, it has been postulated that the rapid turnover of the E2 is necessary for efficient reloading of the E3 with ubiquitin-charged E2 after transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 to the substrate (41–43). Although the interaction between the wild type Cbl-c protein and UbcH5b is still a relatively weak interaction, our data are consistent with the impaired ability of the wild type protein to turn over the catalytically inactive E2 compared with the phosphomimetic mutant (Fig. 6, A and B). Thus the N terminus of the Cbl-c protein appears to stabilize the E3-E2 interaction and lower the catalytic activity.

Recent publications studying the RF SCF and the E2 Cdc34 have demonstrated the rapid kinetics of ubiquitin transfer from the E2 to the substrate (44) and the kinetics of E2 binding and releasing from the RF (43). Together the studies present a very convincing picture of the dynamic interplay of the substrate, the E3 and E2. In this work each ubiquitin molecule transferred requires the release of the E2 and binding of the RF to a new ubiquitin-charged E2 molecule. Our data are consistent with these findings that the rate of release of the E2 is critical for the regulation of the rate of polyubiquitin transfer.

In vivo, substrate ubiquitination is increased by phosphorylation of Cbl proteins (14, 16, 25, 27, 34, 45). Multiple studies have demonstrated that mutation of the linker tyrosine prevents Cbl-mediated ubiquitination of substrates in vivo (25, 26, 46). Based on our in vitro data, activation of the Cbl protein by phosphorylation of the linker tyrosine would only occur if the E2 is not limiting (Fig. 4A). E3 proteins vastly outnumber E2 proteins suggesting that individual E2s will be in excess of any particular E3 (47). One study determined that the cellular concentration of the E2 Ubc2 ranged from 100 nm to 11 μm in a variety of cell lines (48). Also, E3s may interact with multiple E2s (49). Thus it is likely that in a cell, the E2 is not limiting relative to the concentration of the Cbl proteins. In addition, the concentration of the E2 in the cell may not reflect the local molar ratios of the E2 to the E3 at the site of E3-substrate interaction. Taken together with these findings, our data suggest that the concentration of E2 proteins in a cell is not limiting.

Together with the published reports, our data allow the construction of a model for the regulation of Cbl-c E3 activity. In the non-phosphorylated state, the Cbl-c protein can interact with the ubiquitin-charged E2 and transfer ubiquitin to a potential substrate. However, the N terminus of the Cbl-c protein impairs the ability of the protein to release the E2 and bind to a second ubiquitin-charged E2. Upon interacting with Src, Cbl-c is phosphorylated by the activated kinase on the linker tyrosine (Tyr-341) and this weakens the interaction between Cbl-c and the E2. In this model, the initial Ub transfer would not be different between the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated Cbl-c proteins. However, the slower release of the unloaded E2 from the non-phosphorylated Cbl-c would lead to a greater amount of time between the bindings of subsequent ubiquitin-loaded E2 molecules than for the phosphorylated Cbl-c protein. With each subsequent cycle, this would lead to a greater discrepancy in the polyubiquitinated state of the target substrate associated with the non-phosphorylated and phosphorylated Cbl-c proteins. If, in theory, a single ubiquitin molecule is transferred with each cycle, even a small shift in the amount of time between bindings would lead to a measurable difference after multiple cycles. Thus the more rapid cycling of the E2 would result in more rapid polyubiquitination. Our data also suggest that this model can be generalized to other Cbl proteins and in all likelihood the interaction of Cbl proteins with other TKs.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Allan Weissman for helpful discussions and the expression vector for Ubch5b and Dr. Paul Randazzo for helpful discussions and help with binding studies. We also thank Raul Cachau for help with the structural modeling.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by the National Institutes of Health Intramural Research Program, NCI, Center for Cancer Research.

We have used the HUGO nomenclature for the Cbl proteins. The nomenclature is as follows: Cbl refers to the first mammalian family member identified (eg. c-Cbl, Cbl2, and RNF55); Cbl-b refers to the second mammalian Cbl protein identified (eg. RNF56); Cbl-c refers to the third Cbl protein identified (eg. Cbl-3, Cbl-SL, and RNF57).

- E3

- ubiquitin ligase

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- TK

- tyrosine kinase

- TKB

- tyrosine kinase binding

- RF

- RING finger

- SH2

- Src homology 2

- PR

- proline rich

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- Ub

- ubiquitin

- E1

- ubiquitin-activating enzyme

- E2

- ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme

- FL

- full-length

- WT

- wild type

- ΔCT

- deleted C-terminus

- ΔNT

- deleted N-terminus

- LB

- Luria-Bertani

- CAPS

- N-cyclohexyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid

- ID

- internal deletion

- aa

- amino acid

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tsygankov A. Y., Teckchandani A. M., Feshchenko E. A., Swaminathan G. (2001) Oncogene 20, 6382–6402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duan L., Reddi A. L., Ghosh A., Dimri M., Band H. (2004) Immunity 21, 7–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsygankov A. Y. (2008) in Cbl Proteins (Tsygankov A. Y. ed) 1st Ed., Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keane M. M., Ettenberg S. A., Nau M. M., Banerjee P., Cuello M., Penninger J., Lipkowitz S. (1999) Oncogene 18, 3365–3375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nau M. M., Lipkowitz S. (2003) Gene 308, 103–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keane M. M., Rivero-Lezcano O. M., Mitchell J. A., Robbins K. C., Lipkowitz S. (1995) Oncogene 10, 2367–2377 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Langdon W. Y., Blake T. J. (1990) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 166, 159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blake T. J., Shapiro M., Morse H. C., 3rd, Langdon W. Y. (1991) Oncogene 6, 653–657 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lupher M. L., Jr., Andoniou C. E., Bonita D., Miyake S., Band H. (1998) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 30, 439–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meng W., Sawasdikosol S., Burakoff S. J., Eck M. J. (1999) Nature 398, 84–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joazeiro C. A., Wing S. S., Huang H., Leverson J. D., Hunter T., Liu Y. C. (1999) Science 286, 309–312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lorick K. L., Jensen J. P., Fang S., Ong A. M., Hatakeyama S., Weissman A. M. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 11364–11369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Levkowitz G., Waterman H., Zamir E., Kam Z., Oved S., Langdon W. Y., Beguinot L., Geiger B., Yarden Y. (1998) Genes Dev. 12, 3663–3674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yokouchi M., Kondo T., Sanjay A., Houghton A., Yoshimura A., Komiya S., Zhang H., Baron R. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35185–35193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Magnifico A., Ettenberg S., Yang C., Mariano J., Tiwari S., Fang S., Lipkowitz S., Weissman A. M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 43169–43177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim M., Tezuka T., Tanaka K., Yamamoto T. (2004) Oncogene 23, 1645–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donovan J. A., Wange R. L., Langdon W. Y., Samelson L. E. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 22921–22924 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meisner H., Daga A., Buxton J., Fernández B., Chawla A., Banerjee U., Czech M. P. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 2217–2225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivero-Lezcano O. M., Sameshima J. H., Marcilla A., Robbins K. C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 17363–17366 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odai H., Sasaki K., Hanazono Y., Ueno H., Tanaka T., Miyagawa K., Mitani K., Yazaki Y., Hirai H. (1995) Jpn. J. Cancer Res. 86, 1119–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan P. E., Davies G. C., Nau M. M., Lipkowitz S. (2006) Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gao M., Karin M. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 581–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt M. H., Dikic I. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 907–918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peschard P., Ishiyama N., Lin T., Lipkowitz S., Park M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29565–29571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levkowitz G., Waterman H., Ettenberg S. A., Katz M., Tsygankov A. Y., Alroy I., Lavi S., Iwai K., Reiss Y., Ciechanover A., Lipkowitz S., Yarden Y. (1999) Mol. Cell 4, 1029–1040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thien C. B., Walker F., Langdon W. Y. (2001) Mol. Cell 7, 355–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kassenbrock C. K., Anderson S. M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28017–28027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ettenberg S. A., Magnifico A., Cuello M., Nau M. M., Rubinstein Y. R., Yarden Y., Weissman A. M., Lipkowitz S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 27677–27684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davies G. C., Ryan P. E., Rahman L., Zajac-Kaye M., Lipkowitz S. (2006) Oncogene 25, 6497–6509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsui C. C., Pierchala B. A. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 8789–8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang X. A., Dong X. Y., Li Y., Wang Y. D., Chen W. F. (2004) Protein Expr. Purif. 33, 332–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thien C. B., Langdon W. Y. (1997) Oncogene 15, 2909–2919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheffner M., Huibregtse J. M., Vierstra R. D., Howley P. M. (1993) Cell 75, 495–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukazawa T., Miyake S., Band V., Band H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 14554–14559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nau M. M., Lipkowitz S. (2008) in Cbl Proteins (Tsygankov A. Y. ed) Vol. 1, 1 Ed., pp. 3–25, Nova Science Publishers, Inc., New York [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weissman A. M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 169–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das R., Mariano J., Tsai Y. C., Kalathur R. C., Kostova Z., Li J., Tarasov S. G., McFeeters R. L., Altieri A. S., Ji X., Byrd R. A., Weissman A. M. (2009) Mol. Cell 34, 674–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ozkan E., Yu H., Deisenhofer J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18890–18895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eletr Z. M., Huang D. T., Duda D. M., Schulman B. A., Kuhlman B. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 933–934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng N., Wang P., Jeffrey P. D., Pavletich N. P. (2000) Cell 102, 533–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodrigo-Brenni M. C., Morgan D. O. (2007) Cell 130, 127–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Christensen D. E., Brzovic P. S., Klevit R. E. (2007) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 941–948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kleiger G., Saha A., Lewis S., Kuhlman B., Deshaies R. J. (2009) Cell 139, 957–968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pierce N. W., Kleiger G., Shan S. O., Deshaies R. J. (2009) Nature 462, 615–619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tanaka S., Neff L., Baron R., Levy J. B. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 14347–14351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sanada M., Suzuki T., Shih L. Y., Otsu M., Kato M., Yamazaki S., Tamura A., Honda H., Sakata-Yanagimoto M., Kumano K., Oda H., Yamagata T., Takita J., Gotoh N., Nakazaki K., Kawamata N., Onodera M., Nobuyoshi M., Hayashi Y., Harada H., Kurokawa M., Chiba S., Mori H., Ozawa K., Omine M., Hirai H., Nakauchi H., Koeffler H. P., Ogawa S. (2009) Nature 460, 904–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang S., Weissman A. M. (2004) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 61, 1546–1561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Siepmann T. J., Bohnsack R. N., Tokgöz Z., Baboshina O. V., Haas A. L. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 9448–9457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christensen D. E., Klevit R. E. (2009) FEBS J. 276, 5381–5389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]