Abstract

K5 lyase A (KflA) is a tail spike protein (TSP) encoded by a K5A coliphage, which cleaves K5 capsular polysaccharide, a glycosaminoglycan with the repeat unit [-4)-βGlcA-(1,4)- αGlcNAc(1-], displayed on the surface of Escherichia coli K5 strains. The crystal structure of KflA reveals a trimeric arrangement, with each monomer containing a right-handed, single-stranded parallel β-helix domain. Stable trimer formation by the intertwining of strands in the C-terminal domain, followed by proteolytic maturation, is likely to be catalyzed by an autochaperone as described for K1F endosialidase. The structure of KflA represents the first bacteriophage tail spike protein combining polysaccharide lyase activity with a single-stranded parallel β-helix fold. We propose a catalytic site and mechanism representing convergence with the syn-β-elimination site of heparinase II from Pedobacter heparinus.

Keywords: Bacteriophage, Crystal Structure, Heparan Sulfate, Polysaccharide, Protein Structure, K5 Capsular Polysaccharide, Polysaccharide Lyase, Viral Tail Spike

Introduction

The KflA protein is a K5 lyase, an enzyme found as a tail spike protein of coliphages K5A (1, 2) and K1–5 (3), where it catalyzes depolymerization of K5 capsular polysaccharide. K5 lyase enables the phage to recognize and remove the protective K5 capsule around host bacteria, thereby exposing phage receptors in the outer membrane. The K5 capsular polysaccharide is a virulence factor of Escherichia coli K5 isolates, which are responsible for extraintestinal infections (4, 5). The polysaccharide is identical to N-acetyl-heparosan (heparan), a structure present in nonmodified regions of heparan sulfate, and KflA has been utilized previously to study the domain structure of heparan sulfate (6). A bacterial K5 lyase, ElmA, from E. coli K5 strain SEBR 3282 also has been described (7).

The structures of several bacterial glycosaminoglycan-degrading lyases have been published: hyaluronate lyases (EC 4.2.2.1) and chondroitin AC lyases (EC 4.2.2.5) have catalytic N-terminal domains with (α/α)5 toroid topology and C-terminal β-sheet/sandwich domains (8–10), they act at GlcA residues within their substrates. Chondroitin ABC lyases (11, 12) and heparinase II from Pedobacter heparinus (13) have overall structural similarity with these enzymes and can act at GlcA or IdoA (C5-epimerised GlcA) substrate residues, with each enzyme using two overlapping and epimer-specific catalytic groupings (12, 13). A heparin lyase (EC 4.2.2.7, heparinase I) from Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron recently has been shown to have a β-jellyroll domain containing an IdoA-specific active site similar to the IdoA-specific site of heparinase II (14). Heparin-sulfate lyases (heparitinase or heparinase III, EC 4.2.2.8) act at GlcA residues of suitable substrates (15); no representative structure has yet been published, but these enzymes have sequence homology within the C-terminal β-sheet/sandwich domain of heparinase II. Chondroitinase B (EC 4.2.2.4) from Pedobacter heparinus (16, 17) is the only glycosaminoglycan lyase known to contain the right-handed parallel β-helix topology that we report here for KflA. It acts at IdoA residues within the substrate dermatan sulfate.

The first reported structure of a bacteriophage-derived glycosaminoglycan lyase was that of the hyaluronate lyase HylP1, a tail fiber protein of the inducible prophage SF370.1 of Streptococcus pyogenes strain SF370 (18). HylP1 contains a catalytic domain with triple-stranded β-helix topology (TSβH),4 a fold previously observed in noncatalytic domains of other viral tail proteins, including bacteriophage T4 short tail fiber gp12 (19) and needle protein gp5 (20, 21). Short stretches of this fold also are found in the C-terminal domains of coliphage K1F endosialidase (22) and P22 TSP (23), where it acts to stabilize trimeric proteins. We report that this structure also is found within KflA.

Viral tail spike proteins with predominantly single-stranded parallel β-helix architecture include Salmonella phage P22 TSP (23, 24), Shigella phage Sf6 TSP (25), and E. coli phage HK620 TSP (26). These are all glycoside hydrolases, facilitating host recognition and infection through binding and degradation of host O-antigen of lipopolysaccharide. This β-helix fold also is widely found in pectic lyases and some alginate lyases as well as in a small number of glycoside hydrolase subfamilies, including polygalacturonases, rhamnogalacturonases, and dextranases. Groupings of these enzymes based on structure and activity are described in the CAZy database (27).

In this paper, we report the structure of KflA, which represents the first viral tail spike protein with polysaccharide lyase activity and a catalytic single-stranded β-helix domain, a combination frequently observed in bacterial polysaccharide lyases. Also, the proposed catalytic site resembles the syn-β-elimination site of heparinase II, despite the fact that these enzymes have a very different topology.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Strains and Plasmids

The arabinose-inducible plasmid pLYA100 was used for expression, purification, and mutagenesis, as described previously (28), encoding an N-terminally His6-tagged variant of full-length K5 lyase (Swiss-Prot accession no. O09496) from coliphage K5A (His-KflA).

Site-directed Mutagenesis

Mutations of kflA within pLYA100 were generated by the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Each mutant of kflA used in this paper was fully sequenced to preclude mutations introduced by PCR. Errors were found in the published sequence of kflA, the new sequence revealed KflA is much more similar to K5 lyase from coliphage K1–5 (Swiss-Prot accession no. Q9AZ47) than previously determined (99% similarity, 98% identity, length of 632 amino acids). Based upon this sequence, the molecular mass of native KflA is predicted to be 66.9 kDa.

Expression and Purification

His-KflA was expressed as described previously (28). Cells were lysed as described previously (28), but in a modified buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.5, 500 mm NaCl, 10% glycerol, 12.5 mm imidazole) supplemented with 1 mg/ml lysozyme and 0.1% (v/v) protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma, P8849). The lysate was centrifuged (40,000 × g, 10 min, 10 °C), and the supernatant was loaded onto a HisTrap column (GE Healthcare). His-KflA was eluted by increasing imidazole concentration to 250 mm in a linear gradient.

Selenomethionine derivatized His-KflA (seleno-KflA) was purified as above from E. coli B834 (methionine auxotroph strain) transformed with pLYA100 grown in selenium-methionine medium (Molecular Dimensions Ltd.). Protein expression was induced by addition of 0.2% (w/v) l-arabinose when culture A600 reached 0.5.

Mutant variants of His-KflA were screened by lyase assay of cell lysate supernatant from 50-ml cultures of E. coli DH5α harboring the corresponding plasmid, induced as for seleno-KflA. Cells were lysed in BugBuster reagent (Novagen). Cultures with low lyase activity were scaled up to 500 ml, and His-KflA variants were purified by nickel-affinity chromatography.

Gel Permeation Chromatography

Affinity-purified His-KflA was concentrated to 10 mg/ml by centrifugation over a 100-kDa cut-off membrane (Vivaspin 6, Vivascience). A 0.5-ml sample was loaded onto a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (Pharmacia), equilibrated, and eluted with 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 5% glycerol (v/v) at 0.25 ml/min.

Additional Analytical Methods

SDS-PAGE was performed according to the method of Laemmli (29), and unboiled SDS-PAGE samples were heated (37 °C for 30 min) prior to loading (supplemental Fig. S1, a and b). His-KflA content of purified samples was calculated from measurement of A280 (2-μl sample, in triplicate, by Nanodrop) using estimates of extinction coefficient and molecular mass calculated using ProtParam (30). Calculation of pKa values of ionizable groups using the solved structure were performed using H++ server at Virginia Tech (31, 32, 33).5

Lyase Activity Assay

The spectrophotometric assay described previously (28) was performed using a modified reaction buffer (25 mm Tris acetate, pH 8.5, 50 mm NaCl) at 37 °C, recording A232 (supplemental Fig. S2, summarized in Table 1). Initial screening assays were performed by incubating cell lysate supernatants (20 μl) in reaction buffer containing 250 μg K5 for 1 h at 37 °C before recording A232.

TABLE 1.

Enzyme activity and molecular mass estimates of purified His-KflA and mutated variants

Vmax is the initial rate of product formation (means ± S.E., μmol min−1 mg−1 purified enzyme) at 37 °C. Nondetectable activity is denoted by ND (detection limit shown in parentheses). Percentage activity relative to His-KflA is shown in parentheses (means ± S.E.). Initial substrate concentration was 500 μg K5 per 1 ml of reaction volume, and 1 μg of purified protein was used in each reaction, except for E206A and Lys208 mutant assays, where 5 μg purified protein was used. Molecular masses were estimated by light-scattering measurements.

| Sample | Vmax ± S.E. (activity ± S.E.) | Molecular mass |

|---|---|---|

| kDa | ||

| His-KflA | 40.3 ± 0.8 (100 ± 2%) | 168.2 (166.0 ± 1.3)a |

| Y229F | 9.4 ± 0.6 (23.3 ± 1.4%) | 156.4 |

| Y229A | ND (<2%) | 166.5 |

| E206A | ND (<0.5%) | 165.8 |

| K208A | ND (<0.5%) | 157.4 |

| K208R | ND (<0.5%) | 162.5 |

| K208M | ND (<0.5%) | 139.5 |

a The molecular mass was estimated via analytical ultracentrifugation (means ± S.E.).

Crystallization

Crystals were grown from hanging drops; drops were formed by mixing 1 μl of 5.2 mg/ml His-KflA in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 5% (v/v) glycerol with an equal volume of well solution containing 0.2 m KBr and 10% polyethylene glycol 3350. Crystallization was carried out at 20 °C. Needle-like crystals, with the approximate dimensions of 70 μm × 70 μm × 300 μm, formed within 7 days. For data collection, crystals were soaked in a cryoprotectant solution of 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.4 m KBr, and 30% polyethylene glycol 400 for 10 min, followed by flash freezing in liquid nitrogen. Seleno-KflA failed to form crystals under the same conditions as His-KflA but could be crystallized by macroseeding smaller crystals derived from His-KflA into hanging drops of seleno-KflA, which had been set up under the same conditions as for His-KflA, and left for 4 days. Seeded crystals grew within 2–3 days and were subjected to cryoprotection in the same manner as His-KflA. Data were processed using XDS (34) for seleno-KflA and MOSFLM (35) for the His-KflA. Details of space groups, cell dimensions, and data collection statistics are given in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

X-ray data processing and refinement statistics

| Seleno-KflA | His-KflA | |

|---|---|---|

| Data set | ||

| X-ray source | Diamond IO4 | Diamond IO2 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97 | 0.95 |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) | 68.5 130.2 145.8 | 68.5 130.4 145.7 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 30–2.40 (2.46–2.40) | 42–1.60 (1.69–1.60) |

| Total no. reflections | 1,524,155 | 2,246,259 |

| No. unique reflections | 98,276 | 173,321 |

| Average redundancy | 15.5 (15.4)a | 13.0 (12.3) |

| % completeness | 99.7 (99.4) | 100 (100) |

| Rmerge (%)b | 0.088 (0.236) | 0.092 (0.361) |

| Output 〈I/σI〉 | 29.6 (13.3) | 21.6 (7.5) |

| Refinement resolution range (Å) | 42–1.6 (1.64–1.60) | |

| Non-hydrogen atoms | ||

| All | 11,734 | |

| Water | 874 | |

| Rcryst (%) | 17.6 (20.9) | |

| Rfree (%) | 20.3 (25.1) | |

| Mean B value (Å2) | 9.3 | |

| r.m.s.d.cfrom ideal values | ||

| Bond distance (Å) | 0.008 | |

| Bond angle | 1.19° | |

| Estimated overall coordinate error (Å)d | 0.051 | |

| Ramachandran plot statistics (%)e(excluding Gly, Pro) | ||

| Most favored regions | 86.5 | |

| Additionally allowed regions | 12.9 | |

| Generously allowed regions | 0.3 | |

| Disallowed regions | 0.2 | |

Structure Solution and Refinement

Experimental phases were derived from single wavelength anomalous diffraction data collected from a single seleno-KflA crystal. Density calculations and analysis of the self-rotation function indicated a trimer in the asymmetric unit. The locations of 21 selenium atoms of a possible 24 were located using SOLVE (36). These phases were inputted into PHENIX (37) and subjected to density modification and automated model building, which resulted in construction of most of the final model. The final stages of model building were conducted manually, using Coot (38), combined with refinement using REFMAC (39). The final model was complete for all residues from Pro7 to Thr504 on all three chains, and additionally contained 12 bromide ions. The geometry of the model was examined using PROCHECK (40): all main chain and side chain stereochemical parameters were found to be within the limits expected for a refined structure at 1.6-Å resolution. Atomic coordinates and structure factors were deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 2X3H.

RESULTS

His-KflA migrated on SDS-PAGE with an estimated mass of 57 kDa, and nonboiled samples migrated with an apparent mass of 123 kDa (supplemental Fig. S1a). Molecular mass estimated by gel permeation on a calibrated column was 173 kDa (data not shown). Light-scattering analysis and analytical ultracentrifugation of His-KflA gave estimated masses of 168 and 166 kDa, respectively (Table 1). These results suggest His-KflA forms oligomers as reported for K1 endosialidases, which exist in solution as SDS-resistant trimers (23, 41).

Structure

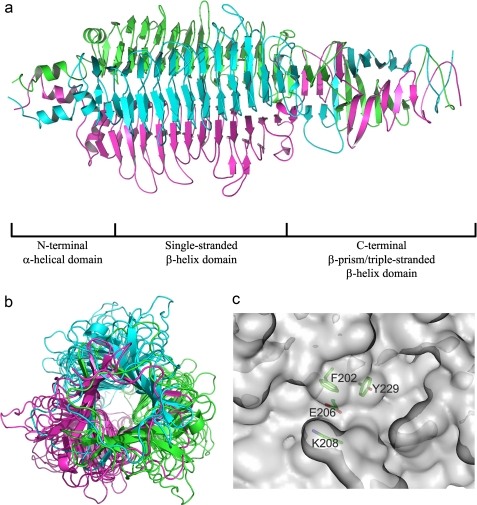

As anticipated from biophysical analysis, the crystal structure of KflA revealed a trimeric complex. The overall structure of mature His-KflA comprises a trimer of three identical monomers intertwined at the carboxyl-terminal domain, with a central 3-fold non-crystallographic axis running along the main axis of the macromolecule (Fig. 1, a and b). The structure can be divided into three domains: a small α-helical domain at the N terminus, a central single-stranded, right-handed β-helix domain and a β-prism/triple-stranded β-helix domain at the C terminus (Fig. 1a).

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the KflA trimer. a, ribbon plot side view: the three monomers are shown in different colors, with the N terminus to the left. The separate domains within the structure are indicated. b, view down the 3-fold axis of KflA, from the C-terminal end of the molecule. c, surface plot of a single monomer from KflA, showing the proposed catalytic groove in the enzyme surface. The locations of Phe202, Glu206, Lys208, and Tyr229 side chains are shown; covalent bonds are colored according to participating atom type (green, carbon; blue, nitrogen; and red, oxygen).

The β-helix contains 12 complete “winds,” with each containing three β-sheets termed PB1, PB2, and PB3, using the nomenclature of Yoder and Jurnak (42) separated by short turns (T1, T2, and T3), some of which have loop insertions. Within each monomer, PB1 sheets face away from the central trimer axis and form a solvent-exposed, concave cleft running along the axis of the β-helix. Three inter-monomeric clefts also exist along the trimeric axis (Fig. 1, a and b).

The lumen of the KflA β-helix contains a stack of 12 hydrophobic residues along PB2 and a ladder of seven stacked Asn residues bordering T1 and PB2. KflA also contains a stack of four Ser residues within T1; this is a feature found in many β-helical proteins that is proposed to stabilize the tight turns between PB1 and PB2 sheets (42). Several intermonomeric contacts are formed along the cleft between β-helices of neighboring chains, including salt bridges exemplified by the pairings Asp290–Arg357 and Asp130–Lys193.

The C-terminal domain of each mature KflA monomer consists of a pair of anti-parallel β-sheets, a pair of parallel β-sheets, and a single β-sheet (forming one turn of a triple-stranded β-helix) followed by five anti-parallel β-sheets (forming one face of a three-sided β-prism), ending in a spiraling coil. In this region, each monomer chain makes multiple contacts with each neighboring chain, effectively holding the trimer together through a 720° rotation (supplemental Fig. S3a). The extensive contacts between monomer chains in the trimeric structure may explain the high thermostability previously observed for KflA, with an unfolding transition point at 65 °C and peak enzyme activity at 44 °C (43).

Active Site Identification

Based on the role of histidine and tyrosine side chains in the catalytic mechanisms proposed for other glycosaminoglycan lyases (10, 44–48), the residues His226, Tyr229, His282, and Tyr253 were selected as targets for site-directed mutagenesis. These residues were individually exchanged for Ala and the resulting His-KflA mutants were assayed for lyase activity. The initial screening assay showed high activity levels (data not shown), comparable with nonmutated His-KflA, except in the case of Y229A. To examine the role of Tyr229 further, the Y229F variant was generated, and both Tyr229 mutants were purified by nickel affinity and assayed for lyase activity. The Y229F mutation reduced activity to ∼25%, whereas the Y229A variant had <2% activity compared with His-KflA (Table 1).

Calculation of pKa values for ionizable residues in their local environments within the structure of KflA highlighted a large shift in the predicted pKa of Glu206 from ≤4.5 to ≥7.4. This side chain may therefore be readily protonated under physiological conditions. Glu206 is at the bottom of a narrow cleft formed by Phe202 and Lys208 (Fig. 1c), located centrally within the intramonomeric groove formed by PB1. This is a typical active site location in other β-helix enzymes. The pKa analysis also provides an explanation of the reduced activity of the Y229F mutant, as Tyr229 is predicted to be a major contributor to the raised pKa of Glu206, through electrostatic interaction. The observation of reduced lyase activity of the Y229A variant compared with the Y229F variant may reflect involvement of the benzyl ring of Tyr229 in substrate binding, possibly through a stacking interaction with pyranosyl sugar rings in the substrate.

No lyase activity could be detected in variants of His-KflA containing mutations at Glu206 (E206A) or nearby Lys208 (K208A, K208R, and K208M) (Table 1). His-KflA and all purified variants behaved similarly during the expression and purification steps and had molecular masses consistent with trimer formation when analyzed by light scattering (Table 1). These trimers were also all SDS-resistant and temperature-labile (supplemental Fig. S1, a and b). A crystal structure of E206A confirmed that this mutant adopted the same structure as His-KflA (data not shown). Lyase assay curves for purified His-KflA, and variants are presented (supplemental Fig. S2). On the basis of these data, we propose that Glu206 and Lys208 are the catalytic residues in the β-elimination reaction catalyzed by KflA.

DISCUSSION

The determination of the structure of KflA has revealed a number of interesting features. First, it forms a trimeric structure with each chain containing a single-stranded β-helix domain with a lyase catalytic site. Unlike K1F endosialidase, KflA is not a processive enzyme, and the trimeric state of KflA may ensure host attachment is maintained through constant partial occupancy of the substrate binding sites present in the trimer. KflA exhibits side chain stacking interactions within the β-helix, which is a common feature of many β-helices (42, 49, 50). The placement of the Asn ladder in KflA at the end of T1 is unusual; previously described β-helix proteins commonly have an internal Asn ladder within the short turn, T2 (50).

A striking similarity was noted between the fold of the C-terminal β-prism/TSβH domain from KflA and the equivalent domain in K1F endosialidase (22). The KflA β-prism extends further than the equivalent fold in K1F endosialidase, with the result that the pairing between chains is altered, but both proteins retain essentially the same strand pattern (supplemental Fig. S3a). The structural similarity covers the last 98 amino acids of the mature proteins and is particularly noticeable throughout the last 31 amino acids, which have a root mean square deviation value of 0.94 Å using TM-align (51) in STRAP software (52). This region contains limited sequence homology between the two mature proteins toward the C terminus residues (41, 53, 54). The folding of this domain in K1F endosialidase, forming two regions of TSβH separated by a region of β-prism, has been proposed to account for the high thermostability of the trimeric structure (22). The TSβH found in the C-terminal domain of P22 TSP is described as a “clamp” holding the trimer together (55), contributing to the high thermostability of P22 TSP. It is likely that the intertwining of the three monomer strands in the C-terminal domain of KflA contributes greatly to the high thermostability observed previously for KflA, with an unfolding transition point at 65 °C and peak enzyme activity at 44 °C (43).

Post-translational Modification

Proteolytic maturation has been reported for K1 endosialidases (41) and ElmA (7). Sequence alignments show KflA contains a conserved post-translational cleavage site at Ser505 (41, 53, 54). The migration of His-KflA on SDS-PAGE at an apparent molecular mass of 57 kDa is consistent with cleavage at Ser505, removing a 14.6-kDa carboxyl-terminal fragment to yield a 56.3-kDa mature protein. The predicted molecular mass of 168.9 kDa for mature, trimeric His-KflA is in good agreement with our analysis by gel permeation chromatography, light scattering, and analytical ultracentrifugation techniques.

The domain removed during maturation has been described as an autochaperone assisting in folding and assembly of trimeric tail spike proteins, with the autolytic cleavage event contributing to stability by making unraveling of trimers energetically unfavorable (54). Recently, the structure and catalytic mechanism of the autochaperone of K1F endosialidase has been described (53). We have aligned the C-terminal region of KflA with the K1F autochaperone (supplemental Fig. S3b), further demonstrating the structural similarity between the C-terminal domains of K1F endosialidase and KflA.

The autochaperone domain contains a highly basic region located on the C-terminal α-helix, which is well conserved within K5 lyases and K1 endosialidases (41) and which closely resembles a Cardin-Weintraub motif (43, 56, 57). This motif is implicated in binding of glycosaminoglycans and was previously proposed to contribute to substrate recognition and binding by KflA (43). The observation of this motif in K1 endosialidase may reflect a more general interaction between a patch of basic side chains with an unbranched, polyanionic polysaccharide such as polySia (polysialic/neuraminic acid or K1 capsular polysaccharide). Removal of the autochaperone through proteolytic maturation raises questions regarding the significance and role of this motif, it is conceivable that the cleaved fragment remains phage-associated under normal conditions of phage assembly to enhance host recognition. However, evidence from cryoelectron microscopy (58) indicates that the autochaperone domain does not remain associated with mature KflA or K1E endosialidase.

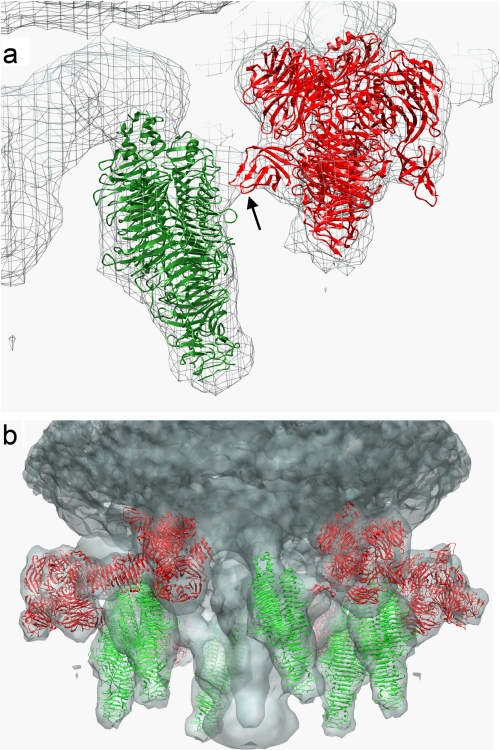

The morphology of ϕK1–5 and ϕK1E was recently studied by cryoelectron microscopy (58). A comparison of the density maps enabled identification of the electron density contribution by K5 lyase, as this enzyme is absent from ϕK1E. The authors showed the P22 TSP structure fitted the density map of K5 lyase. Six symmetrically related copies of the KflA trimer were fitted into the 6-fold averaged electron density map for the K1–5 tail using the fitting function within the UCSF Chimera package (Fig. 2, a and b) (66). This procedure used a simulated map generated from the KflA structures at 24-Å resolution, corresponding to the estimated resolution of the density map for the K1–5 tail (58), and gave a correlation coefficient of 0.77. Interaction between neighboring tail spikes occurs through the β-barrel domain of K1 endosialidase (Fig. 2a). The partners in this interaction are attached to different molecules of adapter protein (gp37), thereby creating an unbroken ring of interacting TSPs around the base of the bacteriophage, which may contribute to stability and correct orientation of tail spikes (Fig. 2b).

FIGURE 2.

Assembly of KflA within the cryo-electron microscopy density map of the tail spike region of K1–5. Ribbon plots of KflA (green) and K1F endosialidase (Protein Data Bank code 1v0F; red) are shown superimposed onto a mesh of the K1–5 tail spike density map (58). a, detail of the contact between KflA and K1F endosialidase trimers; the endosialidase β-barrel domain is indicated. b, arrangement of KflA and K1F endosialidase trimers within the 6-fold symmetric structure of the K1–5 tail spike, superimposed on the semitransparent map of the cryo-electron microscopy density map. KflA and K1F endosialidase were fitted into the density map (accession no. 1335 from the Macromolecular Structure database at the European Bioinformatics Institute), and the figure was generated using the UCSF Chimera package (66).

Catalytic Mechanism

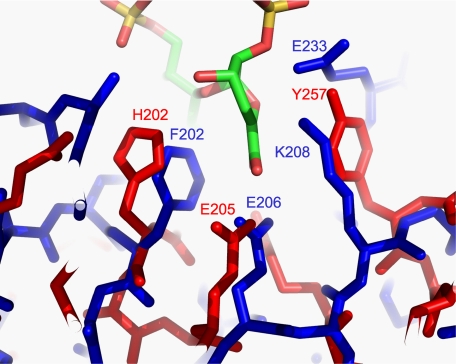

All of the glycosyl moieties in K5 polysaccharide have been shown by NMR to be in the 4C1 chair configuration (59). The β-elimination at GlcA requires abstraction of the axial proton at C5 and breaking of the equatorial glycosidic bond attached to C4. This mechanism is a syn-β-elimination (both leaving groups on the same face of the incipient unsaturated bond) (60). Hyaluronan lyases, chondroitin AC lyases, and heparinase III also catalyze syn-β-elimination reactions, but none of these have a catalytic single-stranded β-helix. Despite being a glycosaminoglycan lyase and having the same overall fold as KflA, chondroitinase B catalyzes an anti-β-elimination at IdoA moieties of dermatan sulfate; this requires a different spatial arrangement of catalytic side chains to that required for syn-β-elimination. Heparinase I and pectic lyases also catalyze anti-β-elimination reactions. Heparinase II has two overlapping catalytic side chain groupings, which can catalyze anti- or syn-β-elimination at IdoA or GlcA components, respectively, in suitable substrates (13). Comparison of KflA residues Glu206 and Lys208, implicated by the mutational analysis to be involved in the catalytic mechanism, with the proposed catalytic residues of other polysaccharide lyases revealed similarity to the active site proposed for heparinase II in syn-β-elimination at GlcA substituents of heparan sulfate. This is essentially the same reaction as that catalyzed by KflA, differing only in the degree of modification of neighboring glycosyl units tolerated by the two enzymes. Despite the overall structure of the catalytic domain of heparinase II (α/α-toroidal) being very different to that of KflA, the two active sites show similar spatial arrangement when superimposed (Fig. 3). Convergence has been noted before between Pel10A, an (α/α)3-barrel pectate lyase, and Pel1C, a parallel β-helix pectate lyase (60), which catalyze anti-β-elimination. The mechanism proposed for heparinase II (13) involves hydrogen-bond formation between the carboxylic group of GlcA and that of Glu205. Tyr257 is proposed to act as a “base” to abstract the proton at C5 of GlcA. Tyr257 also is proposed to act as an “acid,” donating a proton to the proximal glycosidic oxygen, breaking the linkage between C1 of GlcNAc and C4 of GlcA. This dual action of catalytic Tyr residues also has been suggested for other syn-β-eliminases (8).

FIGURE 3.

Overlay of active site residues from KflA and heparinase II. KflA residues are shown in blue, and heparinase II residues are shown in red (Protein Data Bank code 2FUT). The heparin disaccharide ligand from heparinase II is also shown.

The mechanism proposed here for KflA involves hydrogen bond formation between the protonated carboxylic group of Glu206 and the carboxylate of GlcA. This dissipates the negative charge on this group, allowing proton abstraction at C5 of GlcA by Lys208. Lys208 also is proposed to donate a proton to the oxygen of the glycosidic linkage terminating at C4 of GlcA. The order in which reactions at Lys208 occur (and at Tyr257 of heparinase II) has not been determined.

The products of this reaction on a K5 polysaccharide molecule are two shorter chains, one with GlcNAc at the new reducing end and another with Δ-4,5-unsaturated GlcA (4-deoxy-α-l-threo-hex-4-enopyranosyluronic acid) at the nonreducing end. During initial stages of the in vitro assay, reaction products are noninhibitory, as they are cleavable substrates for KflA.

Other mechanisms proposed for lyases to neutralize the negative charge on substrate hexuronate residues include charge dissipation through hydrogen bond formation to Asn side chains as found in hyaluronan lyase (45) and chondroitin AC lyase (8), interaction with Arg side chains as found in pectin lyases A and B (61, 62) or with coordinated Ca2+ ions as found in pectate lyase C (63) and chondroitinase B (17). KflA does not require metal ions for function (28), and no such cofactor was observed in the crystal structure, leading us to conclude the catalytic role of Glu206 is not the coordination of a metal cofactor. Rather, we propose Glu206 is involved in direct hydrogen bond formation with the carboxylic group of GlcA substrate components in a role analogous to that of Glu205 in the syn-β-elimination catalytic site of heparinase II.

Dual Host Specificity

This phenomenon has been reported previously in the case of ϕK1–5, which can infect and replicate in E. coli K1 and K5 strains (3). Coliphage K1–5 has both K1 endosialidase and K5 lyase tail spikes, each attached to the virion through interaction of the N-terminal domain with separate attachment sites on the gp37 adapter protein (Fig. 2, a and b) (58). Coliphage K5A has been observed previously to infect E. coli K95 strains and degrade K95 polysaccharide (64, 65), frequently leading to mistyping of K95 strains as K5. Located 3′ to kflA in the genome of ϕK5A is open reading frame523 which likely encodes a K95-specific TSP (3). We have confirmed plaque formation in lawns of E. coli K95 by ϕK5A (data not shown). Therefore, ϕK5A may more accurately be named ϕK5–95. Dual-specificity has obvious implications for phage evolution and expansion of host range as has been discussed previously (3).

In conclusion, the structure of K5 lyase A reported in this paper represents the first viral tail spike protein to combine a single-stranded β-helix fold with a β-eliminase catalytic mechanism, an enzyme activity common among bacterial glycosaminoglycan-degrading enzymes. Also, the proposed catalytic mechanism involves an unusual role of Glu206 in direct hydrogen bonding to the carboxylate group within the substrate, mimicking the catalytic role of Glu205 in heparinase II.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Tom Jowitt and Marj Howard (Biomolecular facility, Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester) for light scattering and analytical ultracentrifugation analyses and Dr. Jim Warwicker (Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester) for assistance with pKa predictions and interpretation.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) of the United Kingdom.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 2X3H) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S3.

J. Warwicker, personal communication.

- TSβH

- triple-stranded β-helix topology

- TSP

- tail spike protein

- ϕ

- bacteriophage

- gp

- gene product.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gupta D. S., Jann B., Jann K. (1983) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 16, 13–17 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hänfling P., Shashkov A. S., Jann B., Jann K. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 4747–4750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scholl D., Rogers S., Adhya S., Merril C. R. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 2509–2515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vann W. F., Schmidt M. A., Jann B., Jann K. (1981) Eur. J. Biochem. 116, 359–364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moxon E. R., Kroll J. S. (1990) Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 150, 65–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy K. J., Merry C. L., Lyon M., Thompson J. E., Roberts I. S., Gallagher J. T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 27239–27245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Legoux R., Lelong P., Jourde C., Feuillerat C., Capdevielle J., Sure V., Ferran E., Kaghad M., Delpech B., Shire D., Ferrara P., Loison G., Salomé M. (1996) J. Bacteriol. 178, 7260–7264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lunin V. V., Li Y., Linhardt R. J., Miyazono H., Kyogashima M., Kaneko T., Bell A. W., Cygler M. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 337, 367–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Féthière J., Eggimann B., Cygler M. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 288, 635–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li S., Kelly S. J., Lamani E., Ferraroni M., Jedrzejas M. J. (2000) EMBO J. 19, 1228–1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang W., Lunin V. V., Li Y., Suzuki S., Sugiura N., Miyazono H., Cygler M. (2003) J. Mol. Biol. 328, 623–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaya D., Hahn B. S., Bjerkan T. M., Kim W. S., Park N. Y., Sim J. S., Kim Y. S., Cygler M. (2008) Glycobiology 18, 270–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shaya D., Tocilj A., Li Y., Myette J., Venkataraman G., Sasisekharan R., Cygler M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 15525–15535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Y. H., Garron M. L., Kim H. Y., Kim W. S., Zhang Z., Ryu K. S., Shaya D., Xiao Z., Cheong C., Kim Y. S., Linhardt R. J., Jeon Y. H., Cygler M. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 34019–34027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Su H., Blain F., Musil R. A., Zimmermann J. J., Gu K., Bennett D. C. (1996) Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 2723–2734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang W., Matte A., Li Y., Kim Y. S., Linhardt R. J., Su H., Cygler M. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 294, 1257–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michel G., Pojasek K., Li Y., Sulea T., Linhardt R. J., Raman R., Prabhakar V., Sasisekharan R., Cygler M. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32882–32896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith N. L., Taylor E. J., Lindsay A. M., Charnock S. J., Turkenburg J. P., Dodson E. J., Davies G. J., Black G. W. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 17652–17657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Raaij M. J., Schoehn G., Burda M. R., Miller S. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 314, 1137–1146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossmann M. G., Mesyanzhinov V. V., Arisaka F., Leiman P. G. (2004) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 171–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kanamaru S., Leiman P. G., Kostyuchenko V. A., Chipman P. R., Mesyanzhinov V. V., Arisaka F., Rossmann M. G. (2002) Nature 415, 553–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stummeyer K., Dickmanns A., Mühlenhoff M., Gerardy-Schahn R., Ficner R. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 90–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steinbacher S., Seckler R., Miller S., Steipe B., Huber R., Reinemer P. (1994) Science 265, 383–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinbacher S., Miller S., Baxa U., Budisa N., Weintraub A., Seckler R., Huber R. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 267, 865–880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Müller J. J., Barbirz S., Heinle K., Freiberg A., Seckler R., Heinemann U. (2008) Structure 16, 766–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barbirz S., Müller J. J., Uetrecht C., Clark A. J., Heinemann U., Seckler R. (2008) Mol. Microbiol. 69, 303–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cantarel B. L., Coutinho P. M., Rancurel C., Bernard T., Lombard V., Henrissat B. (2009) Nucleic Acids Res. 37, D233–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke B. R., Esumeh F., Roberts I. S. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 3761–3766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M. R., Appel R. D., Bairoch A. (2005) in The Proteomics Protocols Handbook (Walker J. M. ed) pp. 571–607, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anandakrishnan R., Onufriev A. (2008) J. Comp. Biol. 15, 165–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gordon J. C., Myers J. B., Folta T., Shoja V., Heath L. S., Onufriev A. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W368–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warwicker J. (2004) Protein Sci. 13, 2793–2805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kabsch W. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 795–800 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Leslie A. G. W. (1992) Joint CCP4+ESF-EAMCB Newsletter on Protein Crystallography, No. 26 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Terwilliger T. C., Berendzen J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55, 849–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murshudov G. N., Vagin A. A., Dodson E. J. (1997) Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 53, 240–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laskowski R. A., McArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 281–293 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mühlenhoff M., Stummeyer K., Grove M., Sauerborn M., Gerardy-Schahn R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12634–12644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoder M. D., Jurnak F. (1995) FASEB J. 9, 335–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rek A., Thompson J., Roberts I. S., Kungl A. J. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1774, 72–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huang W., Boju L., Tkalec L., Su H., Yang H. O., Gunay N. S., Linhardt R. J., Kim Y. S., Matte A., Cygler M. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 2359–2372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li S., Jedrzejas M. J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41407–41416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pritchard D. G., Trent J. O., Li X., Zhang P., Egan M. L., Baker J. R. (2000) Proteins 40, 126–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rigden D. J., Jedrzejas M. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 50596–50606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pojasek K., Shriver Z., Hu Y., Sasisekharan R. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 4012–4019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yoder M. D., Lietzke S. E., Jurnak F. (1993) Structure 1, 241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins J., Mayans O., Pickersgill R. (1998) J. Struct. Biol. 122, 236–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y., Skolnick J. (2005) Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 2302–2309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gille C., Frömmel C. (2001) Bioinformatics 17, 377–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schulz E. C., Dickmanns A., Urlaub H., Schmitt A., Muhlenhoff M., Stummeyer K., Schwarzer D., Gerardy-Schahn R., Ficner R. (2010) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 210–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schwarzer D., Stummeyer K., Gerardy-Schahn R., Mühlenhoff M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 2821–2831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreisberg J. F., Betts S. D., Haase-Pettingell C., King J. (2002) Protein Sci. 11, 820–830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cardin A. D., Demeter D. A., Weintraub H. J., Jackson R. L. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 203, 556–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hileman R. E., Fromm J. R., Weiler J. M., Linhardt R. J. (1998) Bioessays 20, 156–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leiman P. G., Battisti A. J., Bowman V. D., Stummeyer K., Mühlenhoff M., Gerardy-Schahn R., Scholl D., Molineux I. J. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 371, 836–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blundell C. D., Roberts I. S., Sheehan J. K., Almond A. (2009) J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17, 71–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Charnock S. J., Brown I. E., Turkenburg J. P., Black G. W., Davies G. J. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12067–12072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mayans O., Scott M., Connerton I., Gravesen T., Benen J., Visser J., Pickersgill R., Jenkins J. (1997) Structure 5, 677–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vitali J., Schick B., Kester H. C., Visser J., Jurnak F. (1998) Plant Physiol. 116, 69–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scavetta R. D., Herron S. R., Hotchkiss A. T., Kita N., Keen N. T., Benen J. A., Kester H. C., Visser J., Jurnak F. (1999) Plant Cell 11, 1081–1092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nimmich W. (1994) J. Clin. Microbiol. 32, 2843–2845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nimmich W., Schmidt G., Krallmann-Wenzel U. (1991) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 66, 137–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.