Abstract

Lack of control of food intake, excess size and frequency of meals are critical in to the development of obesity. The stomach signals satiation postprandially and may play an important role in control of calorie intake. Sodium alginate (based on brown seaweed Laminaria Digitata) is currently marketed as a weight loss supplement, but its effects on gastric motor functions and satiation are unknown. We evaluated effects of 10 days treatment with alginate or placebo on gastric functions, satiation, appetite and gut hormones associated with satiety in overweight or obese adults. We conducted a randomized, 1:1, placebo-controlled, allocation-concealed study in 48 overweight or obese participants with excluded psychiatric co-morbidity and binge eating disorder. All underwent measurements of gastric emptying (GE), fasting and postprandial gastric volumes (GV), postprandial satiation, calorie intake at a free choice meal and selected gut hormones after 1 week of alginate (3 capsules vs. matching placebo per day, ingested 30 minutes before the main meal). Six capsules were ingested with water 30 minutes before the gastric emptying, gastric volume and satiation tests on days 8–10. There were no treatment group effects on gastric emptying or volumes, gut hormones (ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1, PYY), satiation, total and macronutrient calorie intake at a free choice meal. There was no difference detected in results between obese and overweight patients. Alginate treatment over 10 days has no effect on gastric motor functions, satiation, appetite or gut hormones. These results question the use of short-term alginate treatment for weight loss.

INTRODUCTION

Obesity is an increasing global epidemic (1) with substantial co-morbidity (2). Meal size, food selection, and frequency of meals determine, in part, an individual’s weight status (3). Cessation of a meal depends on the balance between the sensations of hunger or appetite prior to the meal and of satiation (the feeling of fullness) during the meal (4,5). Decreased satiation in response to food intake may lead to obesity (6,7). The physiological factors associated with postprandial fullness are gastric sensation, emptying and volume [fasting and postprandially (8,9)] and certain gut hormones are involved in mediating satiation, including ghrelin, cholecystokinin (CCK), glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), and peptide YY (PYY) (10).

There is a need for the development of effective and safe therapies for the long term management of obesity. One approach involves the addition of pectin, guar gum or other non-digestible materials that can result in increased viscosity of intragastric contents, delayed gastric emptying, increased postprandial fullness sensation, and decreased insulin and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP) responses postprandially (11–13). These effects are considered important in the improved control of glycemia (14,15) and provide the rationale for treatment of diabetics with guar (16). However, guar is often unpalatable and patient compliance is inconsistent. Thus, it is not surprising that, over a three month period, there may be no effect of guar on weight or diabetic control (17). Alternative dietary supplements have been developed in an attempt to reduce weight in overweight and obese adults.

CM3 alginate is a weight-loss supplement available worldwide, over-the-counter in pharmacies, and via the internet as a “complementary” product. The alginate is extracted from brown seaweed Laminaria digitata and forms the basis for the product; CM3 is derived from cotton wool and bark and contains highly cross-linked cellulose, which expands into a soft sponge-like cuboid after dissolution of the capsule in the stomach or proximal small intestine. The manufacturer claims that CM3 stays for 6–8 hours in the stomach, where it stimulates “satiation sensors” and makes it easier to eat less.

One previously published randomized trial of CM3 alginate showed weight loss of 3–4 kg more than placebo (18). In a recent crossover trial, Berthold and colleagues showed no effect of acute administration of CM3 alginate on appetite sensations, or on gastric emptying (19). Given this contradictory information, and the fact that the effect of CM3 alginate on stomach volume and accommodation are unknown, the aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of CM3 alginate on gastric motor functions, appetite, satiation and satiety gut hormones in overweight and obese adults.

METHODS

Participants

Forty-eight healthy male or female adult volunteers, aged 18–65 years, in either overweight (BMI 25 to 30 Kg/m2) or obese (BMI 30 to 45 Kg/m2) categories were recruited for randomized treatment with CM3 alginate versus placebo, and underwent physiological studies at the Clinical Research Unit (CRU). Study participants had screening questionnaires to assess gastrointestinal symptoms at baseline [Bowel Disease Questionnaire {BDQ}] (20) to assess underlying anxiety or depression [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale {HADS}] (21) and to exclude a binge eating disorder [Questionnaire on Eating and Weight Patterns-Revised] (22).

The following is a summary of the exclusion criteria: weight exceeding 137 kg (due to limitations regarding SPECT imaging studies); prior abdominal surgery other than appendectomy, cholecystectomy, Caesarian section or tubal ligation; positive history of chronic gastrointestinal diseases, systemic disease that could affect gastrointestinal motility or use of medications that may alter gastrointestinal motility, appetite (e.g. sibutramine [Meridia®, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL] or absorption e.g., orlistat [Xenical®, Roche, USA, Nutley, NJ; Alli®, GlaxoSmithKline, USA, Research Triangle Park, NC]); significant untreated psychiatric dysfunction based upon HADS and the self-administered alcoholism screening test (AUDIT-C Alcoholism Screening Test [23]); intake of medication within 7 days of the study (except birth control pill, estrogen replacement therapy, and thyroxine replacement and occasional use of simple analgesics); and binge eating disorderbased upon responses to validated questionnaire (22).

The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Experimental Therapy

CM3 alginate is a patented formulation that contains a compressed, lyophilized sodium-alginate active complex, based on brown seaweed Laminaria digitata. Due to its ability to absorb water quickly, alginate can be changed through a lyophilization process to a new structure which has the ability to expand. It dissolves in the stomach and expands into a soft, gel-like solid, which remains stable in the acid environment of the stomach but dissolves due to the neutral or alkaline environment when it reaches the small intestine. Alginates also bind bile acids and, with chronic administration, they may affect fat absorption (24).

The trial product (CM3 http://www.buyephedradietpills.com/cm3-alginate.html) was purchased by Mayo Research Pharmacy. The purchased capsules were inserted in white 00 size gelatin capsules (which dissolve immediately in water) in order to be identical to placebo capsules (which contained lactose monohydrate) produced by Mayo Clinic Research Pharmacy. The dose of three per day is the recommended dose (according to the manufacturer) in the medium- and long-term treatment; on the other hand, the recent paper by Berthold et al (19) used 6 tablets before the ingestion of the meal used to measure gastric emptying. Therefore, we elected to use the higher dose of 6 tablets per day during the measurements of gastric function.

Participants were requested to swallow the capsules swiftly together with at least 240mL of water, at least half an hour before their main meal of the day at home. Capsules were ingested under supervision during the actual studies conducted in the Clinical Research Unit before meals. To enhance adherence, participants were asked to keep records of when they took their study medication, and these were reviewed at the follow-up visits.

Each capsule contains a cylindrical block of cellulose (18 × 7 × 5 mm3) and contains 405 mg of sodium alginate. The volume of each capsule is estimated to be 4.1mL. When put in water, the capsule content expands 6 fold.

Experimental Procedures

Study Design

The study was conducted in a randomized, placebo-controlled, allocation-concealed fashion. Study participants ingested 3 capsules of CM3 alginate or matching placebo 30 minutes prior to the main meal of the day for one week (days 1–7). On days 8–10, 6 capsules were ingested each day 30 minutes before the gastric emptying, gastric accommodation and satiation tests were conducted. The tests were conducted on consecutive days but not necessarily in the same order (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Experimental protocol

Randomization

Eligible subjects were randomized to either placebo or CM3 alginate. The randomization were balanced on gender and BMI (overweight vs. obese). The randomization schedule was generated by the study statistician and provided directly to research pharmacy. All other study personnel and subjects were kept blinded to the treatment assignments

Satiation by the Nutrient Drink Test and Measurement of Gut Peptides

We used a standardized and validated nutrient drink test (25,26) to measure satiation and postprandial symptoms when drinking a liquid nutrient at constant rate (30mL/min Ensure®: 1Kcal/mL, 11% fat, 73% carbohydrate and 16% protein) (27). Satiation was measured using a scale that combines verbal descriptors and numbers (0 = no symptoms; 5 = maximum or unbearable fullness/satiation). Participants scored the time needed to reach each level of fullness using a digital timer. Nutrient intake was stopped when participants reached the score of 5, and nutrient drink volume to achieve maximum satiation was recorded, and hence calorie intake. Postprandial fullness and symptoms of nausea, bloating and pain, was measured 30 minutes after the meal using 100mm horizontal visual analog scales (VAS), with the words ‘none’ and ‘worst ever’ anchored at the left and right ends of the lines for each symptom.

Prior to starting the satiation test, an intravenous cannula was placed in a hand or forearm vein for subsequent blood draws. Eight blood draws (10mL each) were obtained for measurement of serum levels of ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1 and PYY during and after the nutrient drink test at −15, 0 (beginning of feeding), 15, 30, 45, 60, 120, and 180 minutes. The total blood drawn during the study in each participant was 120mL.

Standard Buffet Meal to Assess Appetite

The standard, free choice, buffet meal was served after completion of the scintigraphic gastric emptying test, that is, 4 hours after ingestion of the radiolabeled test meal. In between the two meals, participants were not allowed to ingest any food or liquids. The free choice meal items were (per serving): Stouffers lasagna (450 calories, 22% protein calories, 46% carbohydrate calories, 32% fat calories), Stouffers vegetable lasagna (420 calories, 16% protein calories, 37% carbohydrate calories, 47% fat calories), cartons of Kraft pudding (120 calories, 2% protein calories, 76% carbohydrate calories, 22% fat calories), and skim milk (90 calories, 36% protein calories, 64% carbohydrate calories, 0% fat calories). This approach has been successfully used in other studies to measure caloric intake after infusion of peptide hormones associated with change in feeding (28). Volunteers were given food of known weights, and the amounts of food calories and macronutrients were calculated from the reported intake.

Gastric Emptying of Solids and Liquids

After an overnight fast, the participant received the study medication with a glass of water 30 minutes prior to the radiolabeled meal. 0.75 mCi 99mTc-sulfur colloid was added to two raw eggs during the scrambling, cooking process. The eggs were served on one slice of bread with 240ml of 1% milk (total calories: 296 kcal, 32% protein, 35% fat, 33% carbohydrate) labeled with 0.05 mCi 111In-DTPA. Anterior and posterior gamma camera images were obtained immediately after ingestion of the radiolabeled meal, every 15 minutes for the first 2 hours, then every 30 minutes for the next 2 hours (total 4 hours after the radiolabeled meal), and analyzed as in previous studies (29–31).

Geometric means of decay-corrected counts in anterior and posterior gastric regions of interest were used to estimate the proportion of 99mTc emptied at each time point (gastric emptying). Intra-individual coefficient of variation in gastric emptying of solids is ~12%.

Assessing Gastric Volume by 99mTc-SPECT Imaging

We used a noninvasive method to measure gastric volume during fasting and after 300 mL of Ensur® (316 Kcal) using single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT). The method has been validated in detail elsewhere (32,33). Intravenous injection of 99mTc-sodium pertechnetate, which is taken up by the parietal and non-parietal cells of the gastric mucosa, allows visualization of the stomach wall. Tomographic images of the gastric wall are obtained t using a dual-head gamma camera (SMV SPECT System™, Twinsburg, Ohio, U.S.A.) that rotates around the body, and imaging processing (AVW 3.0, Biomedical Imaging, Mayo Foundation) used to render a three-dimensional reconstruction of the stomach to measure its volume (mL). We have previously validated the method in vitro and in vivo (34). There is high intra-observer reproducibility to measure gastric volume with this technique (35). Intra- and inter-individual coefficients of variation (at average 9 months) are ~12% (33).

Radioimmunoassay

Active ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1 and PYY were measured in the Immunochemistry Core Laboratory of the Mayo Clinic Clinical Research Unit.

Active ghrelin was measured by competitive radioimmunoassay (RIA) (Linco/Millipore Research, St. Charles, MO 63304). Intra-assay coefficients of variation were 7.3% and 7.8% at 77.5 and 538.3 pg/mL. Inter-assay CVs were 9% and 12% at 40 and 356 pg/mL. The analytical measurement range (AMR) was 10 pg/mL – 2000 pg/mL.

CCK was measured by a double antibody radioimmunoassay (Alpco Diagnostics, Windham, NH 03087). Inter-assay coefficients of variation were 8.7% at 2.5 pmol/L and 6.0% at 11.6 pmol/L. The analytical measurement range of this assay was 0.3 to 25 pmol/L.

GLP-1 was measured as the biologically active GLP-1 (7–36, 7–37) using a two-site noncompetitive immunoassay based on enzyme labeled quantification of GLP-1 detected by a fluorogenic substrate.

PYY was measured by radioimmunoassay (Linco Research, Inc., St. Louis, MO). PYY exists in at least two molecular forms, 1–36 and 3–36, both of which are physiologically active.

Statistical Analysis

The primary endpoints for analysis were: T1/2 for gastric emptying of solids, fasting whole gastric volume, postprandial whole gastric volume, maximum tolerated volume of Ensure® during nutrient challenge test meal, caloric intake from a standard “free choice” meal, and integrated plasma ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1 and PYY levels over the 3 hours after the challenge meal.

The secondary endpoints were: T1/2 of gastric emptying of liquids, aggregate symptom score 30 minutes after ingestion of Ensure®, individual postprandial symptom scores, and mean postprandial ghrelin, CCK, GLP-1, and PYY levels.

Treatment effects on each of these endpoints were assessed using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), incorporating gender (gastric emptying) or BMI (remaining endpoints) as a covariate. These analyses used all randomized subjects (ITT analysis). Subjects with a missing value for a particular endpoint had the missing value imputed using the corresponding mean value (over all subjects with non-missing data on that endpoint). The residual error degrees of freedom were corrected for the number of missing values imputed for a given endpoint (i.e. subtracting one degree of freedom for each missing value imputed) to adjust the residual error variance used to test for treatment effects.

The proportions of subjects with adverse events in the two treatment groups were compared using Fisher’s exact test. A two-sided alpha level of 0.05 was used in the analyses to identify statistically significant differences, and no adjustment was made to testing multiple endpoints as each of them represented different specific hypotheses for the action of alginate.

Sample Size Assessment

Table I summarizes data for primary response measures and uses the (relative variation, CV%) to estimate the effect size detectable with 80% power based on a two-sample t-test at a two-sided α level of 0.05. The effect size is the difference in group means as a percentage of the overall mean for each response and assumes 20 participants per group. We anticipated that the proposed statistical analysis would provide 80% power to detect somewhat smaller differences between groups by adjusting for relevant covariates (e.g. gender in assessing gastric emptying T½) and, in fact, the sample sizes obtained in this study (N=23 vs. 25) would also have increased the power somewhat for the differences shown. The data for satiety testing in healthy volunteers for scintigraphic gastric emptying and for SPECT have been previously published (25,30,34).

Table I.

Sample Size Considerations

| Assuming n=20 per group | Mean | S.D. | CV % | Effect Size† (%)Detectable with 80% Power (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response Type | ||||

| Solid (egg meal) Gastric Emptying T ½ | 112 | 36 | 32 | 29 |

| Satiety Volume (ml) | 1350 | 336 | 25 | 23 |

| Fasting gastric volume (ml) by SPECT | 215 | 67 | 31 | 28 |

| Post-meal gastric volume (ml) by SPECT | 673 | 107 | 16 | 15 |

Effect size is the difference in group means as a percentage of the (overall) listed mean value; CV = coefficient of variation

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

A total of 48 subjects were recruited from November 2008 to March 2009. Table II summarizes the baseline characteristics (mean ± SEM) for the participants in the placebo and alginate groups. There were no differences in age, gender, and BMI between participants among the treatment groups. None of the participants had features suggestive of bulimia, depression or anxiety.

Table II.

Demographics of Participants

| Placebo (N=23) | Alginate (N=25) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.9 ± 2.4 | 41.5 ± 2.5 |

| Gender (Females: Males) | 13:10 | 14:11 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 30.3 ± 0.8 | 31.8 ± 1.2 |

| Overall: 25 to <30 n(%) | 11 (48) | 13 (52) |

| 30 to <35 n(%) | 8 (35) | 5 (20) |

| >=35 n(%) | 4 (17) | 7 (28) |

| Females: 25 to <30 n(%) | 6 (46) | 7(50) |

| 30 to <35 n(%) | 5 (38) | 4 (29) |

| >=35 n(%) | 2 (15) | 3 (21) |

| Males: 25 to <30 n(%) | 5 (50) | 6 (55) |

| 30 to <35 n(%) | 3 (30) | 1 (9) |

| >=35 n(%) | 2 (20) | 4 (36) |

| Obese, n (%) | 12 (52) | 12 (48) |

| HADS Depression score | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 |

| HADS Anxiety score | 3.0 ± 0.5 | 3.6 ± 0.5 |

Gastric Function and Satiation

These data are shown in Table III. There were no significant treatment effects on fasting and postprandial gastric volumes, or on gastric emptying of solids or liquids. There were no significant treatment effects on maximum tolerated volume and postprandial aggregate symptom scores. The individual symptom scores are also shown in Table III and were not different between the two treatment groups.

Table III.

Effect of Treatment on Gastric Motor Functions and Symptoms after Ingestion of Food or Fully Satiating Meal

| Placebo (N=23) | Alginate (N=25) | Overall p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|

| GE T1/2 solid (min) | 113.7 + 4.1 | 115.8 + 3.6 | 0.68 |

| GE T1/2 liquid (min) | 28.4+1.4 | 26.9 +1.3 | 0.44 |

| Fasting gastric volume, mL | 270.8 ± 12.3 | 282.5 ± 10.3 | 0.32 |

| Postprandial (PP) gastric volume, mL | 827.8 ± 23.2 | 799.4 ± 18.7 | 0.45 |

| Delta gastric volume, mL | 554.4 ± 23.3 | 516.9 ± 15.7 | 0.21 |

| Maximum tolerated volume, mL | 1461.9 ± 61.4 | 1365.5 ± 80.5 | 0.45 |

| Aggregate symptom score, mm | 142.7 ± 10.9 | 131.5 ± 11.0 | 0.53 |

| Nausea score, mm | 25.4 ± 5.4 | 17.2 ± 4.0 | 0.16 |

| Fullness score, mm | 69.4 ± 3.4 | 67.2 ± 3.0 | 0.78 |

| Bloating score, mm | 37.7 ± 4.7 | 37.6 ± 5.4 | 0.93 |

| Pain score, mm | 10.1 ± 2.6 | 9.5 ± 2.6 | 0.94 |

| Buffet meal total weight (g) | 1129.2 ± 81.4 | 1168.1 ± 99.0 | 0.89 |

| Total Kcal | 951.2 ± 71.2 | 975.4 ± 74.2 | 0.92 |

| Protein % | 22.2 ± 0.3 | 22.2 ± 0.3 | 0.99 |

| CHO % | 53.3 ± 0.6 | 53.2 ± 0.6 | 0.87 |

| Fat % | 24.5 ± 0.5 | 24.6 ± 0.5 | 0.84 |

Note: All values are mean ± SEM, unless otherwise specified;

from ITT ANCOVA models

Free Choice Meal

There were no significant differences in the total calories (kcal) ingested and total meal weight (grams) at the free choice buffet meal between placebo and alginate groups (Table III). Additionally, there were no significant differences in macronutrient intake between the two treatment groups (Table III).

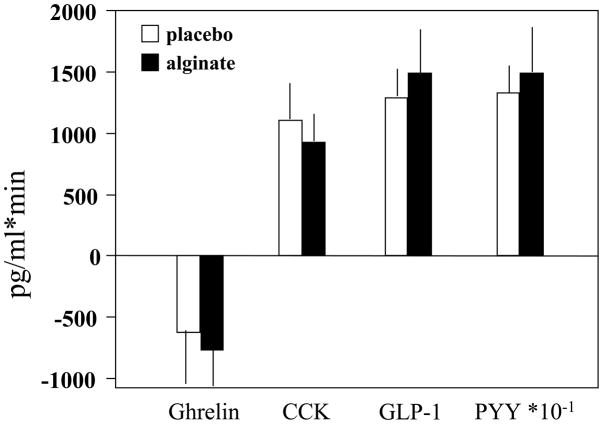

Gut Hormones

Table IV and Figure 2 show the mean values and the area under the curve (postprandial values relative to fasting) of the three hormones of interest. Technical problems with some samples precluded assays in all participants. The number of patients with samples available is shown in Table IV. The statistical analysis used ITT principles with imputation for missing data. There were no treatment-related significant differences in the three satiety related hormones.

Table IV.

Mean Postprandial Hormone Values (Mean ± SD)

| Active Ghrelin | CCK | GLP-1 | PYY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n with available plasma | 43 | 39 | 17 | 32 |

| Placebo | 27.47±12.6 | 8.1±3.7 | 9.7±1.3 | 155.7±40.1 |

| Alginate | 27.2±11.6 | 6.11±3.5 | 14.5±3.3 | 147.2±42.9 |

| Overall p value* | 0.75 | 0.104 | 0.18 | 0.56 |

ANCOVA with BMI as a covariate; ITT analysis

Figure 2.

Area under the curve of postprandial responses in plasma ghrelin, CCK and PYY levels

Adverse Effects

The most common adverse effects with alginate treatment, occurring in at least 10% of the patients, were abdominal bloating (n=3) and upper respiratory tract infections (n=3). One patient randomized to alginate treatment developed cutaneous vasculitis. This patient underwent dermatological evaluation and treatment and has been improving after withdrawal from the study.

Other adverse events occurring with alginate treatment in less than 10% of the patients were heartburn, musculoskeletal pain, headache, GI upset and constipation. There were no significant differences in the proportions of subjects with adverse events between alginate and placebo.

DISCUSSION

In this study we evaluated the effect of a commercially available CM3® alginate, on gastric motor and sensory functions in overweight and obese otherwise healthy individuals. We also evaluated the effect of alginate on satiation by using a nutrient drink test and energy intake in an ad libitum buffet meal.

First, alginate treatment did not affect solid and liquid gastric emptying by scintigraphy. These findings are similar to the data by Berthold et al. (19), although they measured gastric emptying with 13C-octanoic breath test. For the gastric emptying measurements, Berthold et al. used a stable isotope breath test method that incorporated the mathematical analysis of Ghoos and colleagues (36); the latter analysis provided a concordance correlation coefficient relative to simultaneous scintigraphy of 0.44 (37). Therefore, we repeated the studies of the effect of gastric emptying using well-validated scintigraphy. In spite of the different methodologies to evaluate gastric emptying, our studies confirmed the results obtained with stable isotope breath test and found no statistically significant difference in gastric emptying with this cellulose and alginate. Earlier studies (12,38) had claimed that altering meal viscosity with the addition of an alginate would reduce gastric emptying, leading to increased sensation of fullness. However, our study and data from Berthold and colleagues have proven in controlled studies that this statement is not reproducible. Overall, these data suggest that the weight loss observed in prior studies (19) with an alginate does not appear to be influenced by alterations in gastric motor functions. Given the negative results it is important to note that the variation in endpoints observed in this study was similar to the variation used in the sample size assessment and, therefore, a type II statistical error is unlikely to explain the lack of treatment effects.

Second, CM3 alginate treatment did not alter postprandial gastric volumes, satiation measured using a well-established nutrient drink challenge test, or satiety or appetite measured by an influence energy intake in a free choice buffet meal. The manufacturer of alginate CM3® claims that the capsule expands from its original size in the stomach into a viscous gel that leads to increased satiation with eventual weight loss in a long-term period. In our current study, we failed to show a direct impact on satiation. Prior studies have attempted to demonstrate this, but ascertainment of satiation and study design was suboptimal, as satiation was measured with nonvalidated methods and they lacked power (12). Overall, our study data suggest that the increased size and viscosity of CM3 alginate in the stomach have no impact on gastric motor functions or satiation.

Our data are distinct from a study by Paxman and colleagues who showed, based on food diaries recorded by participants, that a week of treatment with an alginate shake reduced energy intake (39). However, the interpretation of caloric intake observed in a controlled setting of an ad libitum buffet meal with total and macronutrient intake calculated by a research dietitian appears more robust when compared to data recorded from food diaries completed by participants. The satiation volume was ~90mL lower with CM3 alginate than placebo and, if this difference was to be replicated daily over a long period, it could conceivably result in weight loss. It is unclear if treatment with an alginate for a longer period of time could alter caloric intake chronically; however, this warrants further investigation.

Third, we assessed the postprandial levels of gut peptides that are associated with satiation or satiety. Since our hypothesis was that CM3 alginate might retard gastric emptying of solids, we chose to evaluate these peptide responses after ingestion of the liquid formula, for which we anticipated there would be a lower effect of the dietary supplement on gastric emptying. Ghrelin, an orexigen produced in the stomach that is known to be suppressed postprandially, was not significantly affected by treatment. Thus, we did not detect further decreases in the mean and integrated responses to the meal with CM3 alginate than with placebo. We also assessed the satiety peptides, CCK from the upper small intestine and PYY from the lower small intestine, and did not detect any treatment differences in the mean postprandial levels of the integrated response during the first 3 hours after onset of meal ingestion. These data suggest that CM3 alginate does not alter the postprandial levels of any of the representative gastric, upper or lower small intestinal satiety-modulating peptides.

While alginate has been demonstrated to affect glycemic control in non-diabetic individuals (40), the exact mechanism is unclear and does not appear to affect GLP-1 or CCK levels in our studies. In contrast, studies evaluating these peptides with guar gum, a high degree viscosity fiber similar to alginate, have shown increased postprandial levels of GLP-1 (41) and CCK (42) in humans.

In conclusion, our study fails to demonstrate significant effects of alginate treatment on gastric motor functions, satiation, appetite or circulating levels of gut peptides associated with satiety. Our data suggest that formal and robust studies are necessary before such a dietetic approach can be recommended as a means to induce weight loss.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Mayo CTSA grant RR0024150 from National Institutes of Health. Dr. Camilleri is supported by grants R01 DK67071 and K24 DK02638 from National Institutes of Health. We thank the Immunochemistry Core Laboratory for assistance with hormonal assays and Cindy Stanislav for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Troiano RP. Changes in the distribution of body mass index of adults and children in the US population. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:807–818. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubert HB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. Obesity as an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease: a 26- year follow-up of participants in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 1983;67:968–977. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.5.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blundell JE, Gillett A. Control of food intake in the obese. Obes Res. 2001;9 (Suppl 4):263S–270S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nicolaidis S, Even P. Physiological determinant of hunger, satiation, and satiety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:1083–1092. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.5.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geiselman PJ. Control of food intake. A physiologically complex, motivated behavioral system. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1996;25:815–829. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(05)70356-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwartz GJ, Tougas G, Moran TH. Integration of vagal afferent responses to duodenal loads and exogenous CCK in rats. Peptides. 1995;16:707–711. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(95)00033-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Geliebter A, Westreich S, Gage D. Gastric distention by balloon and test-meal intake in obese and lean subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:592–594. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Ferber I, Stephens D, Burton DD. Contributions of gastric volumes and gastric emptying to meal size and postmeal symptoms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1685–1694. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado-Aros S, Chial HJ, Burton DD, Camilleri M. Increased caloric intake and decreased postprandial fullness with increased BMI are related to greater fasting gastric volume: a controlled study of 170 volunteers. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:A31. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:13–23. doi: 10.1172/JCI30227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Russo A, Stevens JE, Wilson T, Wells F, Tonkin A, Horowitz M, Jones KL. Guar attenuates fall in postprandial blood pressure and slows gastric emptying of oral glucose in type 2 diabetes. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1221–1229. doi: 10.1023/a:1024182403984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoad CL, Rayment P, Spiller RC, Marciani L, Alonso Bde C, Traynor C, Mela DJ, Peters HP, Gowland PA. In vivo imaging of intragastric gelation and its effect on satiety in humans. J Nutr. 2004;134:2293–2300. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.9.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenkins DJ, Taylor RH, Nineham R, Goff DV, Bloom SR, Sarson DL, Misiewicz JJ, Alberti KG. Manipulation of gut hormone response to food by soluble fiber and alpha-glucosidase inhibition. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:393–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins DJ, Taylor RH, Nineham R, Goff DV, Bloom SR, Sarson D, Alberti KG. Combined use of guar and acarbose in reduction of postprandial glycaemia. Lancet. 1979;2:924–927. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)92622-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams JA, Lai CS, Corwin H, Ma Y, Maki KC, Garleb KA, Wolf BW. Inclusion of guar gum and alginate into a crispy bar improves postprandial glycemia in humans. J Nutr. 2004;134:886–889. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.4.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM. Slow release carbohydrate and the treatment of diabetes. Proc Nutr Soc. 1981;40:227–235. doi: 10.1079/pns19810033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen M, Leong VW, Salmon E, Martin FI. Role of guar and dietary fibre in the management of diabetes mellitus. Med J Aust. 1980;1:59–61. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1980.tb134625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krakamp B, Diefenbach G, Müller-Wieland D. Adipositastherapie—Plazebokontrollierte Doppelblindstudie zur Wirksamkeit von CM3. Kassenarzt. 2001;11:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berthold HK, Unverdorben S, Degenhardt R, Unverdorben M, Gouni-Berthold I. Effect of a cellulose-containing weight-loss supplement on gastric emptying and sensory functions. Obesity. 2008;10:2272–2280. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., 3rd Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1456–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yanovski SZ, Nelson JE, Dubbert BK, Spitzer RL. Association of binge eating disorder and psychiatric comorbidity in obese subjects. Am J Psychiatr. 1993;150:1472–1479. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.10.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;58:1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandberg AS, Andersson H, Bosaeus I, Carlsson NG, Hasselblad K, Härröd M. Alginate, small bowel sterol excretion, and absorption of nutrients in ileostomy subjects. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:751–756. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/60.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chial HJ, Camilleri C, Delgado-Aros S, et al. A nutrient drink test to assess maximum tolerated volume and postprandial symptoms: effects of gender, body mass index and age in health. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2002;14:249–253. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tack J, Piessevaux H, Coulie B, Caenepeel P, Janssens J. Role of impaired gastric accommodation to a meal in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1346–1352. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kissileff HR. Effects of physical state (liquid-solid) of foods on food intake: procedural and substantive contributions. Am J Clin Nutr. 1985;42:956–965. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/42.5.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vazquez Roque MI, Camilleri M, Stephens DA, Jensen MD, Burton DD, Baxter KL, Zinsmeister AR. Gastric sensorimotor functions and hormone profile in normal weight, overweight, and obese people. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1717–1724. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, Greydanus MP, Brown ML, Proano M. Towards a less costly but accurate test of gastric emptying and small bowel transit. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:609–615. doi: 10.1007/BF01297027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cremonini F, Mullan BP, Camilleri M, Burton DD, Rank MR. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic transit measurements for studies of experimental therapies. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2002;16:1781–1790. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burton DD, Camilleri M, Mullan BP, Forstrom LA, Hung JC. Colonic transit scintigraphy labeled activated charcoal compared with ion exchange pellets. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1807–1810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuiken SD, Samsom M, Camilleri M, et al. Development of a test to measure gastric accommodation in humans. Am J Physiol. 1999;277:G1217–G1221. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.277.6.G1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Schepper H, Camilleri M, Cremonini F, Foxx-Orenstein A, Burton D. Comparison of gastric volumes in response to isocaloric liquid and mixed meals in humans. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16:567–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2004.00533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bouras EP, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, et al. SPECT imaging of the stomach: comparison with barostat, and effects of sex, age, body mass index, and fundoplication. Gut. 2002;51:781–786. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Delgado-Aros S, Burton DD, Brinkmann BH, Camilleri M. Reliability of a semi automated analysis to measure gastric accommodation using SPECT in humans. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:A-287. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghoos YF, Maes BD, Geypens BJ, et al. Measurement of gastric emptying rate of solids by means of a carbon-labeled octanoic acid breath test. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1640–1647. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90640-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Odunsi S, Camilleri M, Szarka LA, Zinsmeister AR. Optimizing analysis of stable isotope breath tests to estimate gastric emptying of solids. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2009;21:706–711. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01283.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Torsdottir I, Alpsten M, Holm G, Sandberg AS, Tolli J. A small dose of soluble alginate-fiber affects postprandial glycemia and gastric-emptying in humans with diabetes. J Nutr. 1991;121:795–799. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.6.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paxman JR, Richardson JC, Dettmar PW, Corfe BM. Daily ingestion of alginate reduces energy intake in free-living subjects. Appetite. 2008;51:713–719. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams JA, Lai CS, Corwin H, Ma Y, Maki KC, Garleb KA, Wolf BW. Inclusion of guar gum and alginate into a crispy bar improves postprandial glycemia in humans. J Nutr. 2004;134:886–889. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.4.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Adam TC, Westerterp-Plantenga MS. Glucagon-like peptide-1 release and satiety after a nutrient challenge in normal-weight and obese subjects. Br J Nutr. 2005;93:845–851. doi: 10.1079/bjn20041335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heini AF, Lara-Castro C, Schneider H, Kirk KA, Considine RV, Weinsier RL. Effect of hydrolyzed guar fiber on fasting and postprandial satiety and satiety hormones: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial during controlled weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:906–909. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]