Abstract

Canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC)-encoded nonselective cation channels (NSCCs) are crucial for many cellular responses in a variety of cells; however, their molecular expression and functional roles in airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs) remain obscure. The objective of this study was to determine whether TRPC1 and TRPC3 molecules could be important molecular constituents of native NSCCs controlling the resting membrane potential (Vm) and [Ca2+]i in freshly isolated normal and ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized/-challenged mouse ASMCs. Western blotting, RT-PCR, single-channel recording, whole-cell current-clamp recording, and a fluorescence imaging system were used to determine TRPC expression, NSCC activity, resting Vm, and resting [Ca2+]i. Specific individual TRPC antibodies and siRNAs were applied to test their functional roles. TRPC1 and TRPC3 proteins and mRNAs were expressed in freshly isolated ASM tissues. TRPC3 antibodies blocked the activity of NSCCs and hyperpolarized the resting Vm in ASMCs, whereas TRPC1 antibodies had no effect. TRPC3, but not TRPC1 gene silencing, largely diminished NSCC activity, hyperpolarized the resting Vm, lowered the resting [Ca2+]i, and inhibited methacholine-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. In OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs, NSCC activity was greatly augmented, resting Vm was depolarized, and TRPC3 protein expression was increased. TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies blocked the increased activity of NSCCs and membrane depolarization in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells. TRPC3 is an important molecular component of native NSCCs contributing to the resting Vm and [Ca2+]i in normal ASMCs, as well as membrane depolarization and hyperresponsiveness in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells, whereas TRPC1-encoded NSCCs are only activated in OVA-sensitized/-challenged airway myocytes.

Keywords: canonical transient receptor potential, nonselective cation channels, resting membrane potential, airway smooth muscle cells, asthma

CLINICAL RELEVANCE.

TRPC3 is a predominant molecular component of native nonselective cation channels in airway smooth muscle cells, which is important for the regulation of the resting membrane potential and [Ca2+]i as well as asthma-evoked membrane depolarization and airway hyperresponsiveness. TRPC1-encoded channels are not active in normal airway smooth muscle cells but are activated to mediate cellular responses in asthmatic cells.

Canonical transient receptor potential (TRPC) channels are encoded by genes that are most closely related to the trp gene, which was originally identified in Drosophila, where the trp gene–encoded channels are involved in the photoreceptor signal transduction pathway. TRPC molecules consist of seven members, designated TRPC1 through TRPC7, and have been considered to be the molecular identities of nonselective cation channels (NSCCs) that mediate physiological and pathological cellular responses in many types of excitable and non-excitable cells (1–3).

TRPC1 and TRPC3 mRNAs and proteins have been consistently shown to be expressed in cultured, passaged airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs), and other TRPC members have been found to be present or absent (4–6). A previous study has found that siRNA-mediated TRPC3 gene silencing largely blocks acetylcholine- and TNF-α–induced Ca2+ responses in passaged human ASMCs (6), whereas another report has shown that TRPC6 silencing has no effect on an increase in [Ca2+]i induced by 1-oleyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG), an activator of NSCCs, in passaged guinea pig ASMCs (7). On the other hand, there is no patch clamp study of TRPC channels in ASMCs and there is a lack of information about the molecular expression and functional role of TRPC members in freshly isolated ASMCs.

Albert and colleagues have demonstrated that specific TRPC3 antibodies block the activity of single NSCCs in rabbit ear artery SMCs, suggesting that TRPC3 may encode native NSCCs in vascular SMCs (8). The resting membrane potential (Vm) in SMCs is between −40 and −50 mV, which is less negative than a K+ equilibrium potential of −85 mV. The less negative Vm in rabbit coronary and pulmonary artery SMCs is associated with constitutively active NSCCs (9, 10). Although these channels are constitutively active, they may not only permit direct extracellular Ca2+ influx through the channels themselves; they may also cause membrane depolarization leading to Ca2+ influx via voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels (VDCCs) (1–3). Apparently, NSCCs encoded by TRPC3 or other TRPC molecules are likely to be important for the regulation of the resting Vm and intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) in SMCs, despite no direct experimental data to support this view.

A well characterized feature in asthma is airway muscle hyperresponsiveness. Although the underlying mechanisms are being investigated, membrane depolarization has been found in ovalbumin-sensitized/challenged ASMCs (11, 12). Presumably, membrane depolarization may increase the cell excitability and sensitivity to contractile agonists or can cause extracellular Ca2+ influx, contributing to airway muscle hyperresponsiveness. Because TRPC channels are possibly involved in controlling Vm and [Ca2+]i in SMCs, they may play a significant role in asthmatic airway hyperresponsiveness by mediating membrane depolarization in asthmatic ASMCs.

We hypothesized that TRPC1 or TRPC3 could be an important molecular component of native NSCCs controlling the resting Vm and [Ca2+]i in freshly isolated ASMCs and contributing to asthma-induced membrane depolarization in ASMCs and airway muscle hyperresponsiveness. To test this hypothesis, we first examined whether TRPC1 and TRPC3 molecules might be expressed in freshly isolated mouse ASMCs using Western blot and reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis and determined whether either or both of these TRPC molecules would be critical molecular components of native NSCCs in controlling the resting Vm and [Ca2+]i using the patch clamp recording and fluorescence imaging approaches. We also investigated whether TRPC1, TRPC3, or both could be up-regulated in expression or function, thereby contributing to asthma-induced membrane depolarization and airway hyperresponsiveness, using the patch clamp recording, an unrestricted whole-body plethysmograph system, and the tissue bath technique.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of Freshly Isolated Airway Smooth Muscle Tissues and Cells

Freshly isolated ASM tissues and cells were obtained from tracheas of male C57/B6 mice as described previously (13–15). All animal experiments were performed according to an approved protocol by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Albany Medical College. Mice at 8 to 9 weeks of age were killed by intraperitoneal injection of sodium pentobarbital. Tracheas were dissected off the connective tissue, cartilage, and epithelium to yield ASM tissues. To obtain single ASMCs, isolated ASM tissues were minced and incubated in low Ca2+ physiological saline solution (PSS) containing 1.0 mg/ml papain, 0.5 mg/ml dithioerythritol, and 1.0 mg/ml BSA at 37°C for 15 minutes, followed by incubation in low Ca2+ PSS consisting of 1 mg/ml of collagenase II, collagenase H, dithiothreitol, and BSA at 37°C for 40 minutes. The digested tissues were washed three times by low Ca2+ PSS and gently triturated to release single cells. The low Ca2+ PSS composition was 125 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 0.1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgSO4, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4).

Western Blot and RT-PCR

Western blot and RT-PCR analysis were performed as described previously (16). In Western blot experiments, isolated ASM tissues were homogenized in ice-cold RIPA buffer. The homogenate was centrifuged to obtain total cell lysate. The protein concentration was determined using a Bio-Rad Protein Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane using a Bio-Rad Semi-Dry Electrophoresis Transfer Cell. The nonspecific binding sites on the membrane were blocked by 5% nonfat milk. The membrane was incubated with specific antibodies against TRPC1 and TRPC3 (1:200 dilution) or actin (1:1,000 dilution), followed by horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody, and developed using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). TRPC1 and TRPC3 protein expression levels were normalized to actin expression levels. TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies were purchased from Alomone Laboratories (Jerusalem, Israel), and actin antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

For RT-PCR analysis, total RNAs were obtained from ASM tissues. The first-strand cDNAs were synthesized from RNAs. The resultant cDNA templates were amplified with the specific forward and reverse oligonucleotide primers: 5′-gccatctttgtcaccaggtt-3′ and 5′-gctcgagcaaacttccattc-3′ for mouse TRPC1 gene (NM_011643) and 5′-attcttcgaagccccttcat-3′ and 5′-acgtgaactgggtggtcttc-3′ for mouse TRPC3 gene (NM_019510). The amplified products were electrophoresed on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining.

Single Channel Recording

Single NSCC currents were recorded with an EPC-10 patch-clamp system (Heka Electronics, Lambrecht, Germany) at 10 kHz using the inside-out recording configuration of the patch clamp technique (8, 17) at room temperature (∼ 22°C). Patch pipettes had resistances of approximately 8 MΩ when filled with patch pipette solution. The holding potential was routinely set at −50 mV. Currents were analyzed offline using Clampfit-9 software (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) at 1 kHz and the 50% amplitude threshold method with excluding any events lasting for less than 0.664 ms (2 × rise time), as reported previously (8, 17). The open probability (NPo) was calculated using the equation: NPo = total open time of all channel levels in the patch/sample recording. The bath solution contained 18 mM CsCl, 108 mM Cs-aspartate, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM Na2ATP, 0.2 mM NaGTP, 1 mM CaCl2 10 mM BAPTA, 11 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). The patch pipette solution had 126 mM NaCl, 1.5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, and 11 mM glucose (pH 7.2) and included 100 μM 4,4‘-diisothiocyanatostilbene-2,2’-disulfonic acid, 100 μM niflumic acid, and 5 μM nicardipine. Under these conditions, voltage-gated Ca2+ and K+, as well as Ca2+-activated and swell-activated Cl− channels, were blocked to allow recordings of NSCC conductance (8).

Measurement of Resting Membrane Potential

The resting Vm was measured using the current clamp configuration of the whole-cell patch clamp technique (13–15) at room temperature. The resistance of patch pipettes was 3 to 5 MΩ. The bath solution contained 135 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). The patch pipette solution consisted of 130 mM KCl, 2.0 mM MgCl2, 3.0 mM EGTA, 1.0 mM CaCl2, 5.0 mM Na2ATP, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2).

Measurement of [Ca2+]i

[Ca2+]i was determined using a fluorescence imaging system (IonOptix Corp., Milton, MA) as described previously (14, 15) at room temperature. Single cells were loaded with 4 μM fura-2/AM for 30 minutes and perfused with PSS for 15 minutes. The fluorescent dye was alternatively excited at 340 and 380 nm wavelengths, and the emitted fluorescence at 510 nm was detected.

Transfection of siRNAs

Freshly isolated ASMCs were plated into multiple-well plates with 10% FBS and Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C and transfected with 80 nM TRPC1, TRPC3, or nontarget (control) siRNAs for 72 hours using 2 μl/ml Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according the manufacturer's instructions. TRPC1 (catalog number: J-043863-05), TRPC3 (catalog number: J-049680-05), and nontarget siRNAs (catalog number: D-001810-01-05) were purchased from Dharmacon (Chicago, IL). The efficiency of siRNA-mediated gene silencing was evaluated using Western blot or RT-PCR analysis.

Preparation of OVA-Sensitized/-Challenged Mouse Model

Mice (6–7 wk old) were sensitized by intraperitoneal injection of 0.2 ml OVA (0.6 mg) and aluminum hydroxide (0.4 mg) mixture in 0.9% saline solution. On Days 15 through 19, animals were challenged by intranasal instillation of 50 μl OVA (0.3 mg/ml). Control mice were treated with 0.9% saline solution alone. After the last intranasal exposure to the OVA or saline, mice were subjected to a determination of airway muscle contractile responses to the muscarinic agonist methacholine, assessed by measuring enhanced pause (Penh) using an unrestricted whole-body plethysmograph system (Buxco Research Systems, Wilmington, NC).

Airway muscle contractile responses to methacholine were examined in isolated tracheal rings using the tissue bath technique (14, 15). Isolated tracheal rings were placed in 2-ml tissue bath chambers (Radnoti, Monrovia, CA), containing PSS that was aerated with 21% O2, 5% CO2, and 74% N2 and warmed at 35°C. The resting tone was set at 250 mg. Contractile force was recorded using a PowerLab/4SP recording system (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO), with a highly sensitive force transducer (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using paired or unpaired Student's t test for appropriate two-sample comparisons and using one-way ANOVA with an appropriate post hoc test for multiple-sample comparisons. P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

TRPC1 and TRPC3 Proteins Are Expressed in Freshly Isolated ASMCs

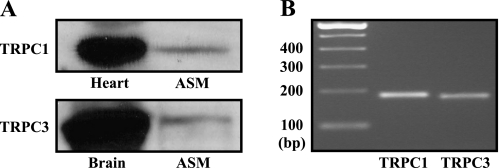

Because previous studies have consistently shown that TRPC1 and TRPC3 molecules are present in cultured, passaged ASMCs (5–7, 18), we examined whether these two TRPC molecules were also expressed in freshly isolated mouse ASM tissues using Western blotting, with TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies that have been confirmed to have the reactivity to the mouse TRPC1 and TRPC3 by the manufacturer. TRPC1 and TRPC3 proteins were detected in freshly isolated ASM tissues (Figure 1A). In complement to these results, RT-PCR analysis revealed that TRPC1 and TRPC3 mRNAs were present as well in isolated ASMCs (Figure 1B). Thus, these two molecules are expressed in cultured and freshly isolated ASMCs, suggesting their potential functional importance in this type of cells.

Figure 1.

Canonical transient receptor potential 1 (TRPC1) and TRPC3 proteins and mRNAs are expressed in freshly isolated airway smooth muscle cells (ASMCs). (A) Western blot results shown are the representatives of at least three different experiments. Heart muscle and brain tissues were used as controls for TRPC1 and TRPC3, respectively. (B) Gel electrophoresis showed RT-PCR products for TRPC1 and TRPC3 mRNAs. Similar results were obtained from five independent experiments.

TRPC3 Is an Important Molecular Component of Native Constitutively Active NSCCs in Freshly Isolated ASMCs

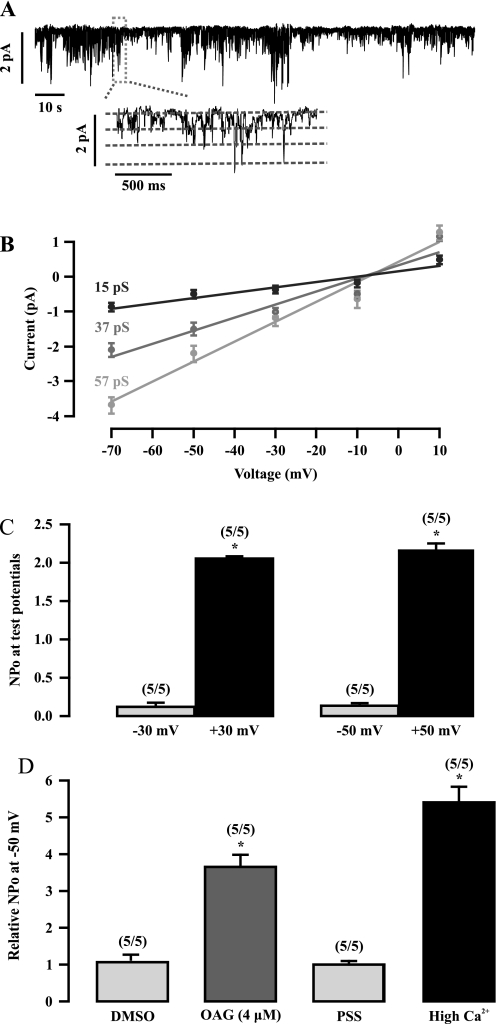

TRPC3 has been shown to be an important molecular constituent of native constitutively active NSCCs in vascular SMCs (8). We questioned whether native constitutively active NSCCs could also be detected in ASMCs. To address this question, we investigated the activity of native NSCCs in freshly isolated mouse ASMCs using the inside-out single channel recording. Figure 2A shows a typical example of these recordings, where the basal activity of native NSCCs with three conductance states was observed in an inside-out patch held at −50 mV. The channel activity could be maintained for up to 20 minutes without displaying a time-dependent decrease. The relationship between the single channel current amplitudes and membrane potentials (range, −70 to 10 mV) showed that the mean channel conductances were 15, 37, and 57 pS, respectively. All three conductance states had the same reverse potential of approximately 0 mV (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Native constitutivelyactive nonselective cation channels (NSCCs) are present in freshly isolated ASMCs. (A) An original recording shows the activity of single NSCCs in a cell membrane patch. The channel activity was recorded at −50 mV using the inside-out patch clamp configuration. The inset illustrates the channel recording at an extended time scale. (B) Graph displaying the mean current–voltage relationship of NSCC currents, which yielded three unitary conductances of 15, 37, and 57 pS. Each data point was obtained from at least five cells from five different animals. (C) Summary of the open probability (NPo) of single NSCCs at −50, −30, 30, and 50 mV. The numbers in parentheses indicates the numbers of patches (cells) and animals investigated. *P < 0.05 compared with the corresponding negative potential. (D) The effect of 1-oleyl-2-acetyl-sn-glycerol (OAG) and high Ca2+ on the NPo of NSCCs at −50 mV. The NPo was determined before and after bath application of 0.4% DMSO, OAG (4 μM) in 0.4% DMSO physiological saline solution (PSS), PSS, or high Ca2+ (100 mM) for 3 minutes. *P < 0.05 compared with control (before application of vehicle or reagent tested).

We next examined and compared the activity of native NSCCs at different membrane potentials. The channel activity was significantly higher at positive potentials than at negative potentials (Figure 2C). The mean open probability (NPo) was 0.135 ± 0.034 at −50 mV and 2.158 ± 0.094 at +50 mV. These results suggest that the native NSCCs exhibit outward rectification in ASMCs.

OAG, a diacylglycerol analog, is an activator of NSCCs in vascular myocytes (19). We assessed the effect of OAG on the channel activity in ASMCs. In control experiments, bath application of 0.4% DMSO, used as a solvent of OAG, had no effect on the channel activity (Figure 2D). The mean NPo values at −50 mV before and after application of DMSO for 3 minutes were 0.165 ± 0.059 and 0.171 ± 0.058, respectively. However, bath application of OAG (4 μM) in 0.4% DMSO solution increased channel NPo. Similarly, the NPo of NSCCs was increased by elevating the bath Ca2+ concentration from 1.5 to 100 mM. Conversely, the channel activity was inhibited by removing bath Ca2+ (data not shown). Together, our findings reveal that constitutively active NSCCs are present in freshly isolated ASMCs, exhibiting three distinct conductance states and diacylglycerol- and Ca2+–gated properties, which are similar to native constitutively active NSCCs in vascular SMCs (19, 20).

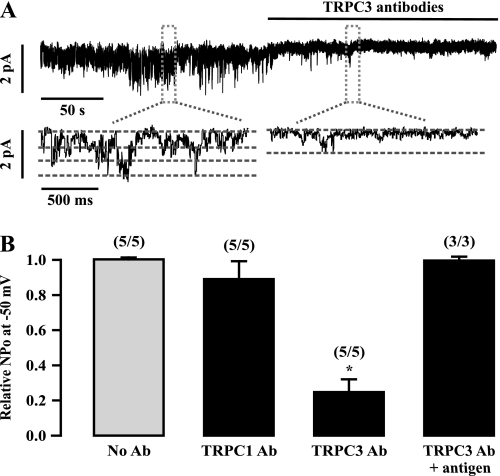

To explore whether TRPC1 and TRPC3 molecules encode native constitutively active NSCCs in ASMCs, we examined the effect of specific antibodies against these two molecules on the activity of NSCCs. Because the inside-out, single-channel recording mode allows the intracellular side of excised membrane patches to face the bath solution, TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies, which recognize their intracellular region, were applied by bath application. Application of TRPC3 antibodies resulted in a rapid, large inhibition of the channel activity (Figure 3A). The mean NPo was decreased by 75 ± 9% after application of TRPC3 antibodies for 3 minutes (Figure 3B). The effect of TRPC3 antibodies was eliminated in the presence of its antigen peptides. In contrast, application of TRPC1 antibodies had no effect.

Figure 3.

TRPC3 antibodies strongly inhibit the activity of single native constitutively active NSCCs in freshly isolated ASMCs. (A) An original recording of single NSCCs in an inside-out patch at −50 mV before and after bath application of specific TRPC3 antibodies (1:200 dilution). The inserts exhibit the channel recording at an extended time scale. (B) Summary of the effect of TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies in the absence and presence of their antigen peptides on the activity of single NSCCs. The relative NPo is presented as the difference in the channel activity recorded before and after application of individual TRPC antibodies (Ab). *P < 0.05 compared with control cells (without application of TRPC antibodies).

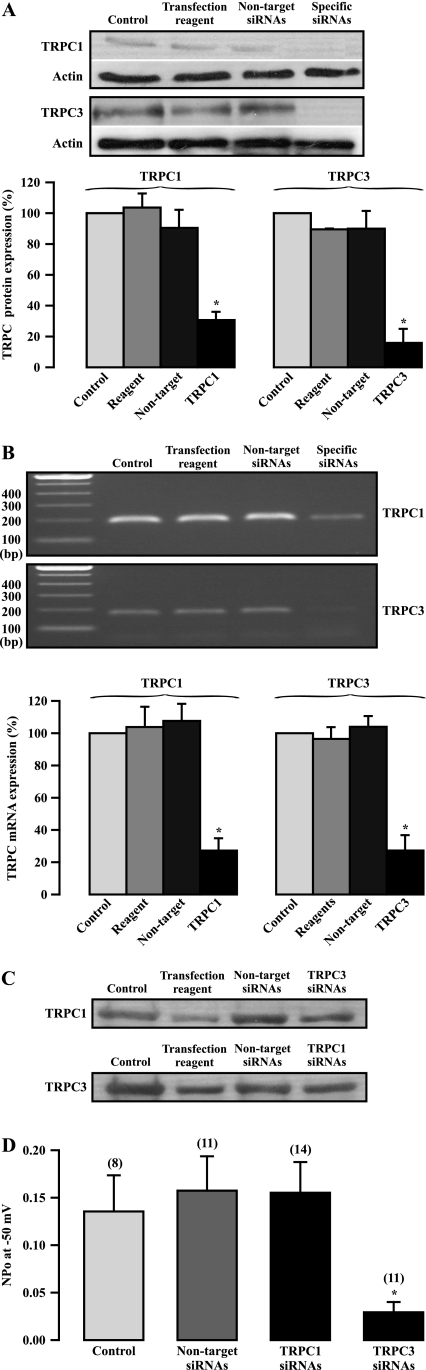

To complement studies using antibodies, we investigated the effect of siRNA-mediated TRPC1 and TRPC3 gene silencing on the activity of NSCCs. Neither transfection of Lipofectamine transfection reagent nor nontarget siRNAs for 72 hours had a significant effect on TRPC1 and TRPC3 expression, as determined by Western blot analysis (Figure 4A). However, transfection of specific TRPC1 siRNAs significantly inhibited its protein expression. Similarly, specific TRPC3 siRNA transfection also largely decreased its protein expression. The siRNA-mediated suppression of TRPC1 expression was further confirmed by RT-PCR analysis (Figure 4B). Furthermore, transfection of TRPC1 siRNAs did not change TRPC3 expression, and TRPC3 siRNAs had no effect on TRPC1 expression (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

TRPC3 gene silencing by siRNAs largely blocks the activity of native constitutively active, nonselective cation channels in ASMCs. (A) Western blotting of TRPC1 and TRPC3 protein expression in cells cultured for 72 hours alone (control) and transfected with Lipofectamine transfection reagent, nontarget TRPC1, and TRPC3 siRNAs for 72 hours. The gel was derived from different experiments, and the photo represents a composite. Bar graph summarizes TRPC1 and TRPC3 protein expression relative to control. Data in each group were obtained from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. (B) RT-PCR analysis of TRPC1 and TRPC3 mRNA expression in control cells and cells transfected with Lipofectamine transfection reagent, nontarget TRPC1, and TRPC3 siRNAs for 72 hours. Data in each group were derived from five separate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. (C) Western blot images show the effect of TRPC1 siRNA transfection on TRPC3 expression, and the effect of TRPC3 siRNA transfection on TRPC3 expression. The results shown are the representatives of at least three individual experiments. (D) The effect of TRPC1 and TRPC3 siRNA transfection for 72 hours on the activity of NSCCs in inside-out patches at −50 mV. Data in each group were obtained from three different experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

Because cell passage due to long-term culture leads to significant changes in the expression and functions of ion channels in ASMCs (21–23), we examined the effect of cell culture for 72 hours on the activity of NSCCs. The results indicate that this short-term cell culture had no significant effect. The mean channel NPo was 0.149 ± 0.026 in freshly isolated cells (n = 36) and 0.135 ± 0.038 in cultured cells (n = 8). Transfection of nontarget siRNAs did not alter the mean channel NPo (Figure 4D). In spite of the large inhibition of its expression, TRPC1 gene silencing did not inhibit the activity of NSCCs. On the contrary, TRPC3 gene silencing produced a large, inhibitory effect. Compared with nontarget siRNAs, transfection of TRPC3 siRNAs caused a reduction in the mean NPo by 81%. These data further demonstrate that native constitutively active NSCCs are mainly encoded by TRPC3 in ASMCs.

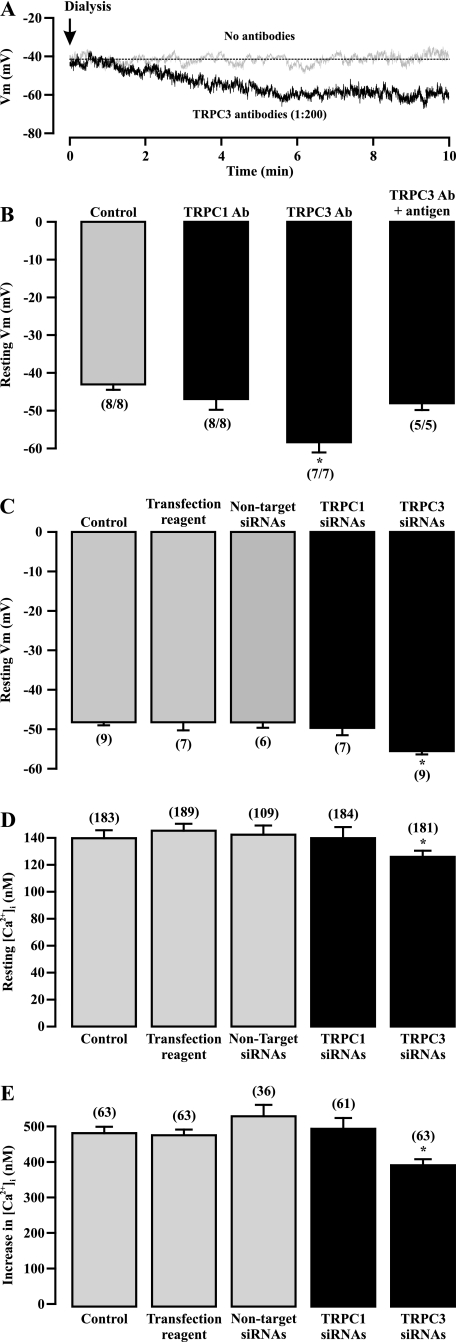

TRPC3-Encoded NSCCs Are Important for Controlling the Resting Membrane Potential and [Ca2+]i in Freshly Isolated ASMCs

We explored the potential contribution of TRPC3-encoded NSCCs to the resting Vm in ASMCs. The resting Vm was unaltered for up to 20 minutes in a cell after intracellular dialysis (without antibodies in the patch pipette) (Figure 5A). Similar results were observed in eight cells (Figure 5B). However, dialysis of TRPC3 antibodies resulted in a progressive, pronounced Vm hyperpolarization in a cell (Figure 5A); the maximum effect occurred after dialysis for 5 to 6 minutes. The mean resting Vm was −58.4 ± 2.7 mV after dialysis of TRPC3 antibodies for 6 minutes, which was significantly more negative than the mean value of −43.6 + 1.7 mV in control cells (undialyzed with antibodies) (Figure 5B). The effect of TRPC3 antibodies was blocked by codialysis of their antigen peptides. Dialysis of TRPC1 antibodies did not produce a significant effect on the resting Vm.

Figure 5.

TRPC3-encoded channels contribute to the resting membrane potential (Vm) in ASMCs. (A) Original recordings of the resting membrane potential in cells dialyzed without and with TRPC3 antibodies (1:200 dilution). (B) Summary of the effect of intracellular dialysis of TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies (Ab, 1:200 dilution) on the resting Vm. *P < 0.05 compared with control (dialyzed without TRPC antibodies). (C) Effect of TRPC1 and TRPC3 siRNA transfection for 72 hours on the resting Vm. Data in each group were obtained from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control (cells cultured for 72 h alone). (D) Effect of transfection of TRPC1 and TRPC3 siRNAs for 72 hours on the resting [Ca2+]i. Data in each group were obtained from three different experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control. (E) Effect of TRPC1 and TRPC3 transfection for 72 hours on methacholine (100 μM)-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. *P < 0.05 compared with control.

To confirm the effect of TRPC antibodies, we determined the effect of TRPC1 and TRPC3 gene silencing on the resting Vm. Like the activity of NSCCs, the resting Vm in short-term (72 h) cultured cells (48.2 ± 0.8 mV; n = 9) was comparable to that in freshly isolated cells (46.1 ± 0.7 mV; n = 28). Neither transfection of Lipofectamine transfection reagent nor nontarget siRNAs had an effect on the resting Vm (Figure 5C). Transfection of TRPC1 siRNAs did not alter the resting Vm. In contrast, the resting Vm was significantly more negative in cells transfected with TRPC3 siRNAs than in cells transfected with Lipofectamine transfection reagent or nontarget siRNAs. These results are consistent with the role of TRPC1 and TRPC3 in mediating the activity of constitutively active NSCCs.

Active NSCCs permit extracellular Ca2+ influx through the channels themselves and may also cause membrane depolarization, VDCC activation, and Ca2+ influx. We tested whether TRPC3-encoded NSCCs could be involved in the regulation of the resting [Ca2+]i using gene silencing. The mean resting [Ca2+]i was 139.7 ± 5.9 nM in cells cultured for 72 hours (n = 183), which is similar to that in freshly isolated cells, as we reported recently (14) (Figure 5D). Transfection of Lipofectamine transfection reagent or nontarget siRNAs did not change the resting [Ca2+]i. Similar to the effect on the activity of NSCCs and resting Vm, transfection of TRPC1 siRNAs had no effect, but transfection of TRPC3 siRNAs significantly lowered the resting [Ca2+]i.

To further explore the functional importance of TRPC3-encoded NSCCs, we assessed the effect of TRPC3 gene silencing on the muscarinic agonist methacholine-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. Application of methacholine (100 μM) caused a large increase in [Ca2+]i in control cells (cultured for 72 h alone; Figure 5E). The muscarinic increase in [Ca2+]i was not altered in cells transfected with Lipofectamine transfection reagent or nontarget siRNAs. Transfection of TRPC1 siRNAs did not produce an effect. On the contrary, TRPC3 gene silencing significantly inhibited methacholine-induced increase in [Ca2+]i. The mean methacholine-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i was decreased by 18% in cells transfected with TRPC3 siRNAs relative to control cells (385.3 ± 17.1 nM versus 472.9 ± 19.8 nM).

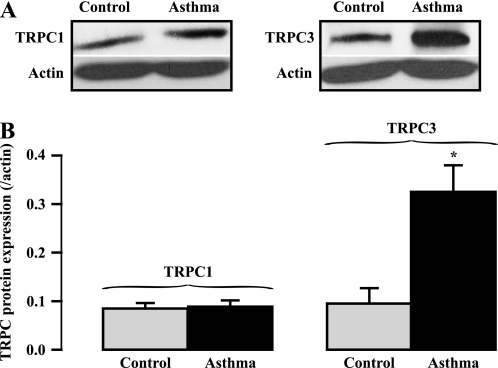

TRPC3-Encoded Native Constitutively Active NSCCs Are Significantly Up-Regulated in Expression and Activity in Freshly Isolated OVA-Sensitized/-Challenged ASMCs

TRPC-encoded NSCCs have been assumed to be involved in airway muscle hyperresponsiveness in asthma (5, 6); however, a lack of direct experimental evidence inspired us to investigate whether TRPC1 and TRPC3 expression were altered in ASM tissues from OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice. Using Western blot analysis, we found that TRPC1 protein expression level was not changed in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASM tissues (Figure 6). On the other hand, TRPC3 protein expression level was increased in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASM tissues. The mean TRPC3 expression level was augmented by 3-fold in OVA-sensitized/-challenged tissues relative to control tissues.

Figure 6.

TRPC3 protein expression is specifically increased in ovalbumin (OVA)-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs. (A) Western blotting determination of individual TRPC protein expression in ASM tissues from normal and OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice. (B) Bar graph shows summary of individual TRPC protein expression. TRPC expression levels were normalized to actin expression levels. Data were obtained from at least three different experiments. The mean data were taken from three separate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with control (mice without OVA-sensitization/challenge).

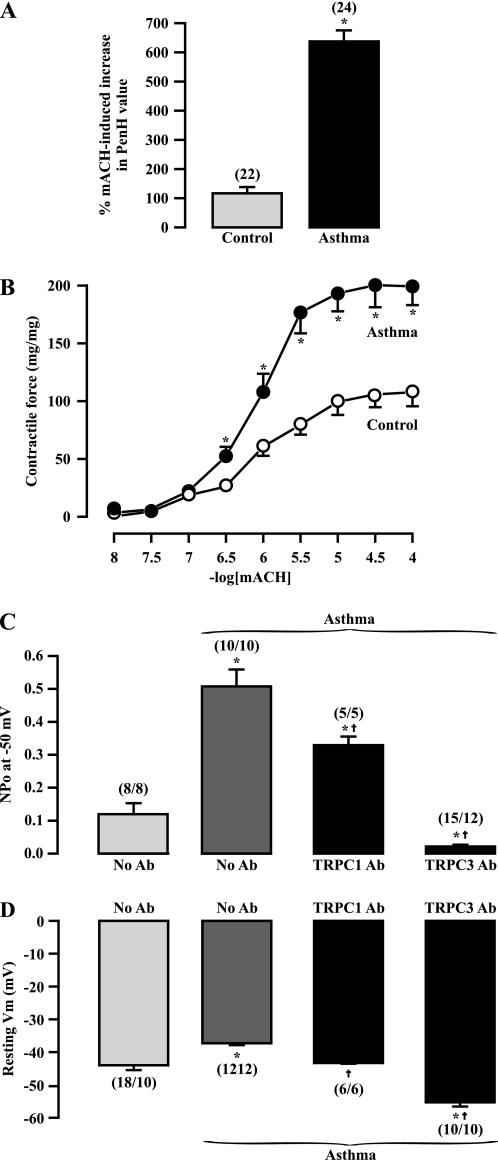

OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice showed airway muscle hyperresponsiveness. Aerosol application of methacholine evoked a large increase in the Penh value, an indicator of airway constriction, determined using a Buxco's unrestricted whole-body plethysmograph system, in control and OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice. However, the methacholine-provoked increase in Penh value was 5.1 times greater in OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice than in control mice (Figure 7A). Compatible with the increased Penh value, methacholine-evoked muscle contraction was markedly augmented in isolated tracheal rings from OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice (Figure 7B).

Figure 7.

TRPC1- and TRPC3-encoded channels contribute to the increased activity of native constitutively active cation channels and membrane depolarization in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs. (A) OVA-sensitized/challenged mice showed airway muscle hyperresponsiveness determined by the increased Penh value after aerosol application of methacholine (30 mg/ml), measured using a Buxco's unrestricted whole-body plethysmograph system. (B) Bar graph summarizes methacholine-evoked muscle contraction in isolated tracheal rings from 10 control and 12 OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice. *P < 0.05 compared with control. (C) Effect of bath application of TPPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies (Ab, 1:200 dilution) on the increased activity of NSCCs at −50 mV in outside-out patches from OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice. *P < 0.05 compared with normal cells dialyzed without TRPC antibodies; †P < 0.05 compared with OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells dialyzed without TRPC antibodies. (D) Effect of intracellular dialysis of TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies (Ab, 1:200 dilution) on the membrane depolarization in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs. *P < 0.05 compared with control. †P < 0.05 compared with OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells dialyzed without TRPC antibodies.

The open probability of native NSCCs was markedly increased in inside-out patches from OVA-sensitized/-challenged mouse ASMCs. The mean NPo was increased by 4.2-fold in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells relative to normal (nonsensitized/challenged) cells (Figure 7C). Bath application of specific TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies for 3 minutes blocked the increased channel activity in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells. In addition, the channel NPo in cells after application of TRPC3 antibodies was significantly lower than that in normal cells.

Similar to previous findings in OVA-sensitized/-challenged rat cells (11), membrane depolarization was found in OVA-sensitized/-challenged mouse ASMCs (Figure 7D). The mean resting Vm was −43.1 ± 1.4 mV in control cells and −37.3 ± 0.6 in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells. Intracellular dialysis of TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies for 6 minutes prevented membrane depolarization in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells. Moreover, the mean Vm in cells after dialysis of TRPC3 antibodies was much more negative than that in normal cells. Thus, TRPC3-encoded native constitutively active NSCCs are up-regulated in expression and activity, contributing to membrane depolarization and hyperresponsiveness in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs, whereas TRPC1-encoded NSCCs are only activated to mediate the increased cellular responses in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs.

DISCUSSION

An earlier study using RT-PCR has shown that TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, and TRPC6 mRNAs are expressed in cultured, passaged guinea-pig ASMCs (4). However, another study indicates that TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC4, and TRPC6 (but not TRPC2 and TRPC5) mRNAs are detected in passaged human ASMCs (5). It has also been found that TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, and TRPC6 (but not TRPC2) mRNAs are present in passaged human ASMCs (6). Previous studies using Western blot analysis or immunofluorescence staining further revealed expression of TRPC1, TRPC3, and TRPC6 proteins in passaged guinea pig ASMCs (4, 24); TRPC1, TRPC3, and TRPC4 proteins in porcine ASMCs (18); TRPC6 protein in passaged guinea pig and human ASMCs (5, 7); and TRPC1, TRPC3, TRPC4, TRPC5, and TRPC6 proteins in passaged human ASMCs (6). Using Western blot and RT-PCR analysis in this study, we have found that TRPC1 and TRPC3 proteins and mRNAs are detected in freshly isolated mouse ASM tissues (see Figure 1). Taken together, the results from the current and previous studies reveal that TRPC1 and TRPC3 are exclusively present in cultured and freshly isolated ASMCs as well as in all species examined, suggesting that these two TRPC molecules may form functional NSCCs to exert important functional roles in ASMCs.

In support of the formation of TRPC3-encoded functional NSCCs in ASMCs, it has been reported that TRPC3 gene silencing significantly inhibits TNF-α– and acetylcholine-induced Ca2+ influx in passaged human ASMCs (6). Previous studies using the cell-attached single channel recording have shown the existence of constitutively active NSCCs with a unitary conductance of 17, 20, and 25 pS in freshly isolated bovine and human ASMCs (25–28). However, there is no patch clamp study of TRPC-encoded channels in this type of cells. Using the inside-out single channel recording, here we have demonstrated that constitutively active NSCCs are present in freshly isolated mouse ASMCs and exhibit three conductance states of 15, 37, and 57 pS (Figure 2). The difference in the channel conductances in previous reports and our study may be largely due to the use of different recording techniques because single channel activity is recorded much more easily in excised patches than in cell-attached patches. More importantly, we have shown that the open probability of single native NSCCs is mostly inhibited by specific TRPC3 antibodies and siRNAs and is unaffected by TRPC1 antibodies and siRNAs (Figures 3 and 4). These data indicate that native constitutively active NSCCs are encoded predominantly by TRPC3 in ASMCs. Similarly, a previous report has disclosed that application of TRPC3 antibodies blocks the activity of single native NSCCs in rabbit ear artery SMCs (8), indicating that TRPC3 is a crucial molecular component of NSCCs in vascular SMCs. TRPC3 gene silencing results in the inhibition of its expression and NSCC activity to a very similar extent (by ∼ 80%). Apparently, the inhibited activity of NSCCs can be explained by a reduction in the functional TRPC3-encoded channels.

The resting Vm normally is between –40 and –50 mV in ASMCs, which is to a great extent less negative than the K+ equilibrium potential of approximately −85 mV (11, 12). It has been shown that native NSCCs are associated with the less negative resting Vm in rabbit pulmonary and coronary artery SMCs (9, 10). These data, together with previous research reporting that TRPC3 is an important molecular constituent of NSCCs in rabbit ear artery SMCs (8), suggest that TRPC3-formed NSCCs are most likely to be involved in the generation of the resting Vm in SMCs. In support of this view, our data show that specific TRPC3 antibodies and gene silencing significantly hyperpolarize the resting Vm (Figure 5). In contrast, TRPC1 antibodies and gene silencing fail to produce an effect. Therefore, TRPC3-encoded, constitutively active NSCCs contribute to the less negative resting Vm in ASMCs.

The constitutively active NSCCs may result in extracellular Ca2+ influx through the channels themselves as well as through VDCCs; as such, these channels are likely to play an important role in the regulation of the resting [Ca2+]i. We have found that specific TRPC3 gene silencing significantly lowers the resting [Ca2+]i, whereas TRPC1 gene silencing has no effect (Figure 5). These findings for the first time provide the experimental proof for the functional importance of NSCCs, particularly TRPC3-encoded channels, in controlling the resting [Ca2+]i in SMCs. Moreover, TRPC3 gene silencing inhibits methacholine-evoked increase in [Ca2+]i. Similarly, a previous study has reported that TRPC3 gene silencing blocks acetylcholine-induced increases in [Ca2+]i as well in cultured, passaged ASMCs (6). Collectively, TRPC3-encoded NSCCs are important for agonist-induced Ca2+ responses in freshly isolated and cultured airway myocytes. Our previous pharmacological studies suggest that NSCC-associated extracellular Ca2+ influx may contribute to approximately 21% of methacholine-induced initial increase in [Ca2+]i in ASMCs (29, 30). In this study, we have found that TRPC3 gene silencing inhibits methacholine-evoked initial increase in [Ca2+]i by 18%. Relative to intracellular Ca2+ release, Ca2+ influx through TRPC3-encoded NSCCs makes a smaller contribution to muscarinic initial increase in [Ca2+]i. On the other hand, this TRPC3-mediated Ca2+ signal is persistent during muscarinic stimulation and may thus play a significant role in the control of contraction in ASMCs under physiological and pathological conditions.

The 80 nM of siRNAs used in this study is fairly high. However, this or higher concentrations of siRNAs have been used to effectively silence specific genes without cytotoxic effect in previous studies. For example, 100 and 200 nM of siRNAs have been used to achieve TRPC3 and TRPC6 gene silencing in ASMCs. More importantly, the NSCC activity, resting Vm, [Ca2+]i, and the muscarinic increase in [Ca2+]i are unaltered in cells transfected with nontarget or TRPC1 siRNAs relative to control cells (cultured alone or transfected with Lipofectamine transfection reagent). Transfection of TRPC3 siRNAs does not change TRPC1 gene expression and vice verse. The effects of TRPC1 and TRPC3 siRNAs are comparable to those of TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies. Therefore, the findings from experiments using siRNAs provide reliable and useful information on the functional role of TRPC1 and TRPC3 in ASMCs.

Asthma is a chronic airway inflammatory disease with a well known characteristic of airway muscle hyperresponsiveness, which may result from a membrane depolarization–associated increase in the cell excitability and sensitivity to contractile agonists in ASMCs (11, 12). Airway muscle contractile responses to the muscarinic receptor agonist methacholine are largely enhanced in OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice and in isolated tracheal rings from these mice (Figure 7), indicating asthmatic airway muscle hyperresponsiveness. Although the molecular mechanisms for asthma-evoked membrane depolarization are being investigated, we now provide novel experimental evidence revealing that TRPC3 protein expression level is significantly higher in ASM tissues from OVA-sensitized/-challenged mice relative to normal (nonsensitized/challenged) mice; however, the TRPC1 protein expression level is unaltered (Figure 6). The activity of NSCCs is significantly increased in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs (Figure 7). The increased channel activity is abolished by application of TRPC3 antibodies. Moreover, the activity of NSCCs in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells after application of TRPC3 antibodies is lower than that in normal (nonsensitized/challenged) cells, which is consistent with the concept that TRPC3 encodes the native constitutively active NSCCs in normal ASMCs (Figures 3 and 4). Taken together, TRPC3-encoded native constitutively active NSCCs are significantly up-regulated in expression and activity in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs, contributing to asthmatic airway muscle hyperresponsiveness. TRPC1 antibodies can also prevent the increased activity of NSCCs in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs (Figure 7), although TRPC1 protein expression is unaltered (Figure 6). In spite of the lack of a clear explanation for these results, we speculate that TRPC1-encoded NSCCs, which are silent in normal cells, can be activated by an unknown mechanism in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells.

Comparable to previous reports (11, 12), the current study has also shown that the resting Vm is depolarized in OVA-sensitized/-challenged mouse ASMCs (Figure 7). The membrane depolarization in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells is fully blocked by intracellular dialysis of TRPC3 antibodies. The resting Vm in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells after dialysis of TRPC antibodies has been found to be more negative than that in normal cells. TRPC1 antibodies also abolish membrane depolarization in OVA-sensitized/-challenged cells. These results are in agreement with the effect of TRPC1 and TRPC3 antibodies on the activity of NSCCs. Therefore, TRPC3-encoded NSCCs not only contribute to the resting Vm but also play an important role in asthma-induced membrane depolarization and associated hyperresponsiveness in ASMCs, whereas TRPC1-encoded NSCCs can only be significantly activated to mediate cellular responses in asthmatic ASMCs.

In conclusion, in this study we have for the first time provided evidence revealing that TRPC1 and TRPC3 proteins are expressed in freshly isolated ASMCs, similar to cultured ASMCs (4–6). TRPC3 can form native constitutively active NSCCs controlling the resting Vm and [Ca2+]i in ASMCs. TRPC3-encoded channels are up-regulated in molecular expression and functional activity in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs, which play an important role in asthma-evoked membrane depolarization and hyperresponsiveness. TRPC1-encoded NSCCs remain unchanged in their molecular expression but play an important role in mediating cellular responses in OVA-sensitized/-challenged ASMCs.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Amanda Belawski and Rachel Wurster for technical assistance.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01HL071000 (Y.-X.W.), by AHA Scientist Development Grant 0630236N (Y.-M.Z.), and by Established Investigator Award 0340160N (Y.-X.W.).

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1165/rcmb.2009-0091OC on July 31, 2009

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of the authors has a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Montell C, Birnbaumer L, Flockerzi V, Bindels RJ, Bruford EA, Caterina MJ, Clapham DE, Harteneck C, Heller S, Julius D, et al. A unified nomenclature for the superfamily of TRP cation channels. Mol Cell 2002;9:229–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clapham DE, Montell C, Schultz G, Julius D. International Union of Pharmacology. XLIII. Compendium of voltage-gated ion channels: transient receptor potential channels. Pharmacol Rev 2003;55:591–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilius B, Owsianik G, Voets T, Peters JA. Transient receptor potential cation channels in disease. Physiol Rev 2007;87:165–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ong HL, Brereton HM, Harland ML, Barritt GJ. Evidence for the expression of transient receptor potential proteins in guinea pig airway smooth muscle cells. Respirology 2003;8:23–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Corteling RL, Li S, Giddings J, Westwick J, Poll C, Hall IP. Expression of transient receptor potential C6 and related transient receptor potential family members in human airway smooth muscle and lung tissue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;30:145–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.White TA, Xue A, Chini EN, Thompson M, Sieck GC, Wylam ME. Role of transient receptor potential C3 in TNF-α-enhanced calcium influx in human airway myocytes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2006;35:243–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Godin N, Rousseau E. TRPC6 silencing in primary airway smooth muscle cells inhibits protein expression without affecting OAG-induced calcium entry. Mol Cell Biochem 2007;296:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert AP, Pucovsky V, Prestwich SA, Large WA. TRPC3 properties of a native constitutively active Ca2+-permeable cation channel in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol 2006;571:361–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bae YM, Park MK, Lee SH, Ho WK, Earm YE. Contribution of Ca2+-activated K+ channels and non-selective cation channels to membrane potential of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells of the rabbit. J Physiol 1999;514:747–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terasawa K, Nakajima T, Iida H, Iwasawa K, Oonuma H, Jo T, Morita T, Nakamura F, Fujimori Y, Toyo-oka T, et al. Nonselective cation currents regulate membrane potential of rabbit coronary arterial cell: modulation by lysophosphatidylcholine. Circulation 2002;106:3111–3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu XS, Xu YJ. Potassium channels in airway smooth muscle and airway hyperreactivity in asthma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2005;118:574–580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirota S, Helli P, Janssen LJ. Ionic mechanisms and Ca2+ handling in airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J 2007;30:114–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu QH, Zheng YM, Wang YX. Two distinct signaling pathways for regulation of spontaneous local Ca2+ release by phospholipase C in airway smooth muscle cells. Pflugers Arch 2007;453:531–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu QH, Zheng YM, Korde AS, Li XQ, Ma J, Takeshima H, Wang YX. Protein kinase C-ɛ regulates local calcium signaling in airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;40:663–671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu QH, Zheng YM, Korde AS, Yadav VR, Rathore R, Wess J, Wang YX. Membrane depolarization causes a direct activation of G protein-coupled receptors leading to local Ca2+ release in smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009;106:11418–11423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng YM, Wang QS, Rathore R, Zhang WH, Mazurkiewicz JE, Sorrentino V, Singer HA, Kotlikoff MI, Wang YX. Type-3 ryanodine receptors mediate hypoxia-, but not neurotransmitter-induced calcium release and contraction in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells. J Gen Physiol 2005;125:427–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dong L, Zheng YM, Van RD, Rathore R, Liu QH, Singer HA, Wang YX. Functional and molecular evidence for impairment of calcium-activated potassium channels in type-1 diabetic cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008;28:377–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ay B, Prakash YS, Pabelick CM, Sieck GC. Store-operated Ca2+ entry in porcine airway smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2004;286:L909–L917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Albert AP, Piper AS, Large WA. Properties of a constitutively active Ca2+-permeable non-selective cation channel in rabbit ear artery myocytes. J Physiol 2003;549:143–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Albert AP, Large WA. Comparison of spontaneous and noradrenaline-evoked non-selective cation channels in rabbit portal vein myocytes. J Physiol 2001;530:457–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snetkov VA, Hirst SJ, Ward JP. Ion channels in freshly isolated and cultured human bronchial smooth muscle cells. Exp Physiol 1996;81:791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sweeney M, McDaniel SS, Platoshyn O, Zhang S, Yu Y, Lapp BR, Zhao Y, Thistlethwaite PA, Yuan JX. Role of capacitative Ca2+ entry in bronchial contraction and remodeling. J Appl Physiol 2002;92:1594–1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shepherd MC, Duffy SM, Harris T, Cruse G, Schuliga M, Brightling CE, Neylon CB, Bradding P, Stewart AG. KCa3.1 Ca2+ activated K+ channels regulate human airway smooth muscle proliferation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2007;37:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ong HL, Chen J, Chataway T, Brereton H, Zhang L, Downs T, Tsiokas L, Barritt G. Specific detection of the endogenous transient receptor potential (TRP)-1 protein in liver and airway smooth muscle cells using immunoprecipitation and Western-blot analysis. Biochem J 2002;364:641–648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Snetkov VA, Pandya H, Hirst SJ, Ward JP. Potassium channels in human fetal airway smooth muscle cells. Pediatr Res 1998;43:548–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snetkov VA, Ward JP. Ion currents in smooth muscle cells from human small bronchioles: presence of an inward rectifier K+ current and three types of large conductance K+ channel. Exp Physiol 1999;84:835–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snetkov VA, Hapgood KJ, McVicker CG, Lee TH, Ward JP. Mechanisms of leukotriene D4-induced constriction in human small bronchioles. Br J Pharmacol 2001;133:243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Helli PB, Janssen LJ. Properties of a store-operated nonselective cation channel in airway smooth muscle. Eur Respir J 2008;32:1529–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang YX, Fleischmann BK, Kotlikoff MI. M2 receptor activation of nonselective cation channels in smooth muscle cells: calcium and Gi/Go requirements. Am J Physiol 1997;273:C500–C508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang YX, Kotlikoff MI. Muscarinic signaling pathway for calcium release and calcium-activated chloride current in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol 1997;273:C509–C519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]