Abstract

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (Pdgfrα) identifies cardiac progenitor cells in the posterior part of the second heart field. We aim to elucidate the role of Pdgfrα in this region. Hearts of Pdgfrα deficient mouse embryos (E9.5–E14.5) showed cardiac malformations consisting of atrial and sinus venosus myocardium hypoplasia, including venous valves and sinoatrial node. In vivo staining for Nkx2.5, showed increased myocardial expression in Pdgfrα mutants, confirmed by Western blot analysis. Due to hypoplasia of the primary atrial septum, mesenchymal cap and dorsal mesenchymal protrusion, the atrioventricular septal complex failed to fuse. Impaired epicardial development and severe blebbing coincided with diminished migration of epicardium-derived cells and myocardial thinning, which could be linked to increased WT1 and altered α4-integrin expression. Our data provide novel insight in a possible role for Pdgfrα in transduction pathways that lead to repression of Nkx2.5 and WT1 during development of posterior heart field derived cardiac structures.

Keywords: Pdgfrα knockout mouse embryos, heart development, dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (DMP), sinus venosus myocardium, epicardium-derived cells (EPDCs)

Introduction

Platelet-derived growth factors (PDGFs) are expressed in many cardiac structures as shown in the avian embryo (van den Akker et al. 2005; Bax et al. 2009). This not only accounts for myocardium of the primary heart tube, but also for second heart field (SHF) derived myocardium and mesenchyme at the venous pole (van den Akker et al. 2005; Bax et al. 2009).

Loss of PDGF receptor alpha (Pdgfrα) signaling leads to neural crest related malformations at the outflow tract (OFT) of the heart, like persistent truncus arteriosus and double outlet right ventricle (Schatteman et al. 1995; Richarte et al. 2007). We recently described pulmonary venous (PV) abnormalities in Pdgfrα mutant mice originating at the venous pole of the heart (Bleyl et al. 2010). In this region, both in avian and mouse, expression of PDGFR-α was observed not only in the sinus venosus myocardium but also in the mesenchyme of the SHF (van den Akker et al. 2005; Bax et al. 2009), referred to as posterior heart field (PHF) (Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 2007) as opposed to the anterior heart field (AHF) at the OFT (Kelly 2005). The PHF and its derivatives arise in part from the mesothelial lining of the coelomic cavity by epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation (EMT) (Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 2007; Mahtab et al. 2008). Splanchnic mesoderm and mesenchyme of the dorsal mesocardium at the venous pole not only support a recruitment of SV myocardium (myocardial component of the PHF), but also the formation of the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion (DMP) (Snarr et al. 2007b) and the proepicardial organ (PEO) (mesenchymal components of the PHF) (Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 2007; Mahtab et al. 2008; Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 1998). The DMP is in continuity with the mesenchymal cap on the primary atrial septum that normally fuses with the AV cushions to form a AV septal complex that is important for normal AV septation (Snarr et al. 2007b).

The epicardium, developing from the PEO, spreads out over the myocardial surface. After completion of epicardial covering of the heart, epicardial cells undergo EMT and migrate into the subepicardial space between the epicardium and myocardium. A subpopulation of epicardium-derived cells (EPDCs) then migrates into the myocardium to form interstitial fibroblasts, and smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts of the coronary vasculature (Dettman et al. 1998; Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 1998). Besides their physical contribution to the developing heart, EPDCs have a regulatory role in the differentiation of atrioventricular valves (Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 1998; Lie-Venema et al. 2007) and in the development of the ventricular myocardium (Eralp et al. 2005; Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 2000). Expression of PDGFR-α in the PEO, epicardium and EPDCs (Bax et al. 2009; Mellgren et al. 2008) suggests a role for Pdgfrα-signaling in the remodeling of the ventricular compact myocardium through epicardial-to-myocardial interaction. Indeed, loss of Pdgfrα-signaling leads to hypoplastic ventricular myocardium (Schatteman et al. 1995).

Building on our previous work on Pdgfrα (van den Akker et al. 2005; Bax et al. 2009; Bleyl et al. 2010), we now analyzed the cardiovascular abnormalities in Pdgfrα deficient mouse embryos at several developmental stages to elucidate the function of Pdgfrα-signaling in cardiac development with specific relation to its expression during normal development in the PHF. Proper epicardial adhesion and epicardial-myocardial interaction have been described to be established by the interaction between vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) and α4-integrin (Kwee et al. 1995; Sengbusch et al. 2002). Also, the initiation of the process of EMT by several factors, like Snail, E-cadherin, Wilm’s Tumor1 (WT1) and retinoic acid (RA)-synthesizing enzyme RALDH2 (Merki et al. 2005; Perez-Pomares et al. 2002; Martinez-Estrada et al. 2010) are important for the epicardial-myocardial interaction.

Here, we present data demonstrating a role for Pdgfrα-regulated PHF-derived myocardial differentiation and remodeling.

Results

General characteristics of the Pdgfrα mutant embryos

We determined the cardiac phenotype of the Pdgfrα−/− embryos (E9.5–E14.5) and as expected we observed cardiac malformations in the OFT region in Pdgfrα mutants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardiac malformations seen in Pdgfrα−/− and PDGFRαGFP/GFP embryos between embryonic day (E) 9.5–14.5.

| Total KO hearts | E9.5 (n=4) | E10.5 (n=4) | E11.5 (n=5) | E12.5 (n=3) | E13.5 (n=4) | E14.5 (n=2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth retardation (>E0.5) | 1 | 2 | ||||

| PEO hypoplasia | 4 | |||||

| Epicardial dissociation | 3 | 3 | ||||

| Myocardial hypoplasia | 3 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Ventricular septal fenestrations | 2 | 3 | ||||

| DMP hypoplasia | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | ||

| Abnormal orientation PV connection | 4 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Aortic arch right sided | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Common arterial trunk | 2 | 1 | 1 | |||

| Dextroposed Ao | 2 | 2 | ||||

| Double Outlet Right Ventricle (DORV) | 2 | |||||

| Atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) | 2 | 1 |

In the further analysis of the Pdgfrα−/− embryos we focused on cardiac malformations at the venous pole region and those related to altered epicardial-myocardial interaction (Table 1). Since previous studies showed that Pdgfrα−/− embryos were growth retarded, littermates that deviated more than E0.5 from their estimated embryonic day were excluded from morphometric and immunhistochemical analysis (Table 1).

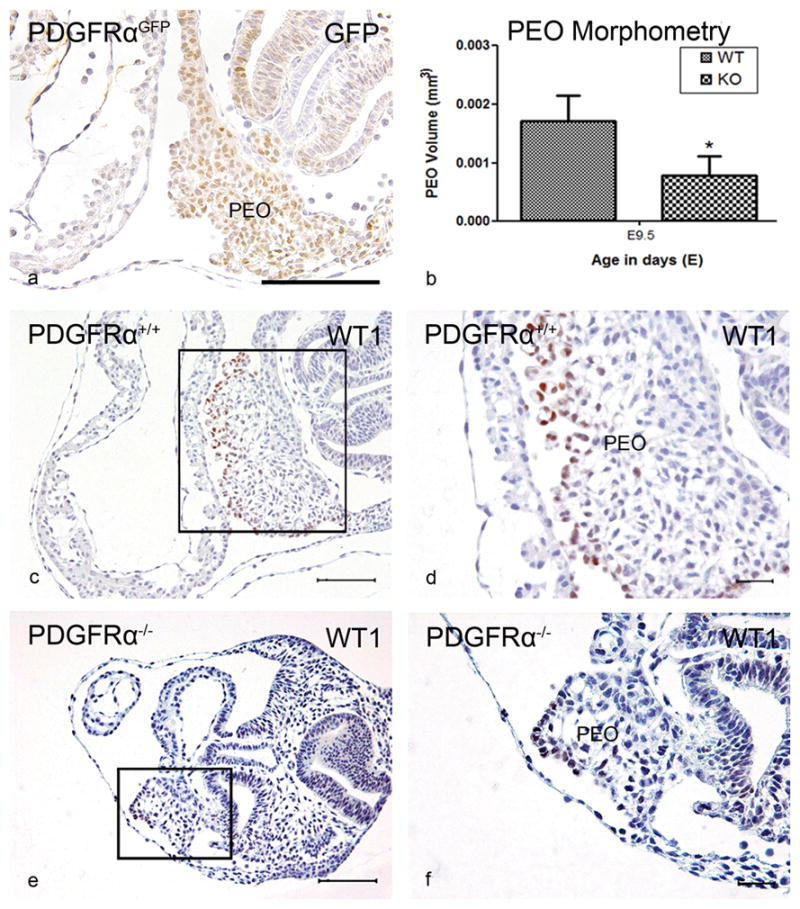

Stage E9.5

At E9.5, we observed marked expression of PDGFRαGFP at the venous pole in the mesocardium, the myocardium of the sinus venosus, the PEO and in the coelomic mesothelium (Figure 1a and Supplemental Figure I a–c). Positive cells were found dispersed throughout the atrial and ventricular myocardium including the inner curvature (Supplemental Figure I d–f). The OFT myocardium was negative for PDGFRαGFP (Supplemental Figure I c). In four Pdgfrα mutant embryos there was a significantly smaller PEO (53,9%, P<0.05) (Figure 1b) and all showed an abnormal orientation of the pulmonary vein (PV). The number of cells expressing WT1 in the PEO and in the coelomic mesothelium seemed less (Figure 1c–f), although the expression of WT1 seemed more intense in the positive cells compared to the wildtype.

Figure 1. PEO abnormalities in Pdgfrα−/− embryos at stage E9.5.

PDGFR-α expression in the PEO was reported by GFP in PDGFRαGFP knockin embryos (PDGFRαGFP) (a). The volume of the PEO (mm3) of Pdgfrα−/− (KO) (n=4) was significantly (*) smaller (P<0.05) compared to WT embryos (n=3) (b). Transverse sections showed in the PEO WT1 expression (c,e overview, d,f magnification). Scale bars: a = 100 μm, c,d = 200 μm, e,f = 30μm

Stage E10.5

At this stage, PDGFRαGFP embryos showed expression in the mesenchymal cap, covering the rim of the primary atrial septum (AS) (Figure 2a), the venous valves and the cardinal vein myocardium (Supplemental Figure II a–c). The developing sinoatrial node (SAN), marked by expression of MLC-2a and negativity for Nkx2.5, was also positive for the receptor. The atrial and ventricular myocardium has become negative for PDGFRαGFP while the epicardium and developing AV cushions on the ventricular septum (VS) and OFT cushions were positive (Supplemental Figure II a–i). The marked expression of WT1 in the epicardium of the mutants that covered the myocardium was scattered. In three Pdgfrα−/− embryos only an abnormal orientation of the PV was found (Table 1).

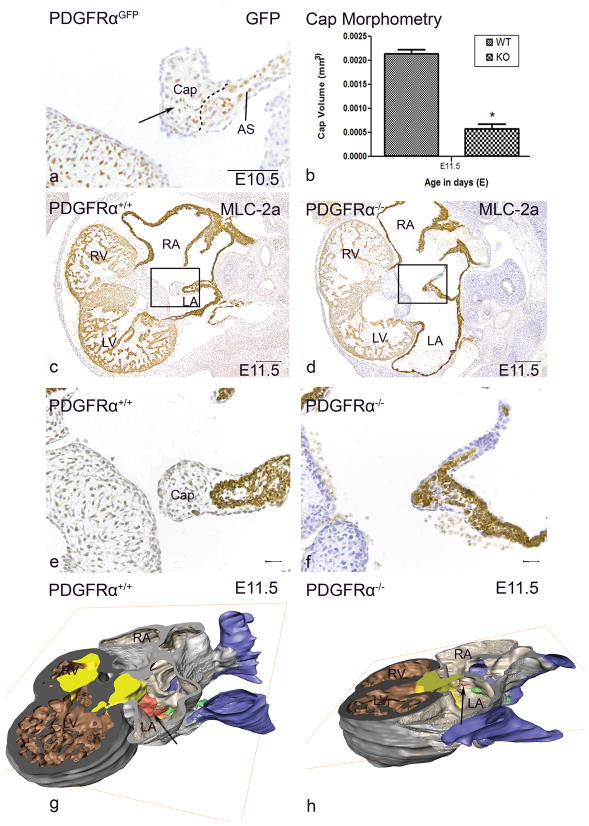

Figure 2. The mesenchymal cap.

At stage E10.5, PDGFR-α expression in the mesenchymal cap (Cap, arrow) and atrial septal myocardium (AS) was seen by GFP in PDGFRαGFP knockin embryos (PDGFRαGFP) (a). At stage E11.5, the mesenchymal cap on the primary AS was significantly (*) smaller in Pdgfrα−/− (KO) (n=3) embryos compared to controls (WT) (n=3) (P<0.05) (b). Transverse sections and lateral view of 3D-reconstructions of Pdgfrα−/−(d,f,h) and WT embryos (c,e,g) showing a hypoplastic Cap (red) that has not fused with the atrioventricular (AV) cushions (yellow). Color codes: atrial myocardium: light grey, cardinal veins lumen/sinus venosus lumen: blue, ventricular myocardium: dark grey. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle. Scale bars: a = 100 μm, c,d = 200 μm, e,f = 30μm

Stage E11.5

Several abnormalities in the sinus venosus region were observed in the Pdgfrα−/− embryos. The venous valves were shorter compared to the wildtype (Figure 2c,d). The AS and mesenchymal cap were hypoplastic (Figure 2c–h). Morphometric analysis showed that the mesenchymal cap was 72,7% smaller compared to the control (P<0.05) (Figure 2b). The mesenchymal cap did not fuse with the atrioventricular cushions (Supplemental Figure III) and the DMP was hypoplastic and did not border the incorporation of the PV into the left atrium. The orientation of the PV was more caudal (Supplemental Figure III), however the connection was still to the left atrium (Figure 2h). No malformations of the ventricular myocardium were observed.

Stage E12.5

At this stage, in the three Pdgfrα−/− embryos several cardiac malformations could be discerned (Table 1). The connection of the PV to the left atrium was more caudal. Furthermore, the myocardium of the cardinal veins was hypoplastic and showed fenestrations. In all mutants, the mesenchymal cap and DMP were hypoplastic, as we already described previously for the DMP (Bleyl et al. 2010).

The epicardium was dissociated from the ventricular myocardium (Figure 3b,f,j) and almost no EPDCs had migrated into the myocardium (Figure 3j) compared to the wildtype (Figure 3a,e,i). The ventricular myocardium (Figure 3f) and in 2/3 mutants the myocardium of the developing VS was spongy.

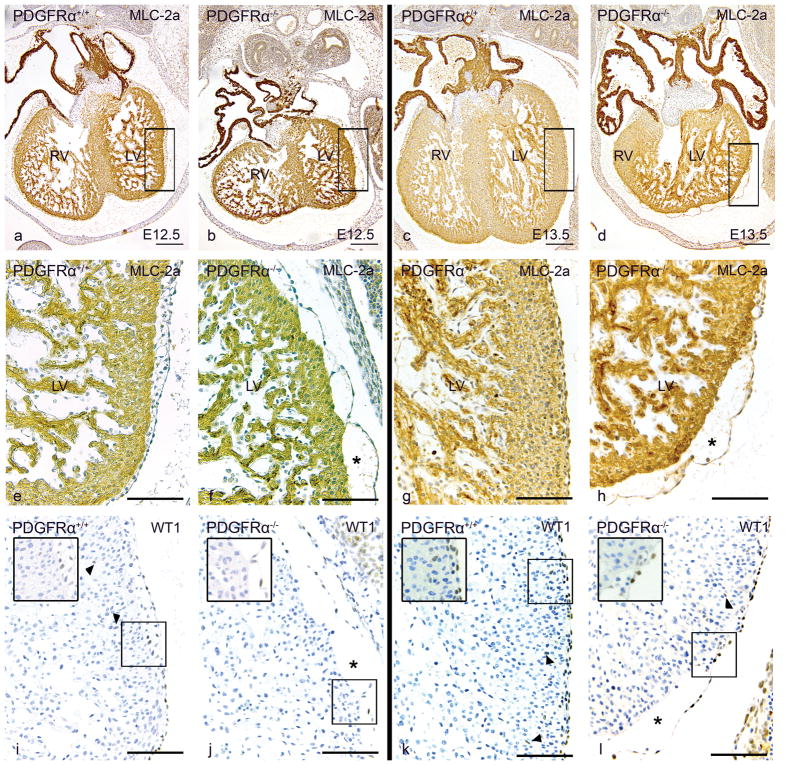

Figure 3. Epicardial-myocardial interaction.

Transverse sections of Pdgfrα+/+ embryos of stage E12.5 (a,e,i) and E13.5 (c,g,k) stained with MLC-2a (a–h) and WT1 (i–l) were compared to Pdgfrα−/− embryos (E12.5(b,f,j), E13.5(d,h,l)). At both stages, hypoplasia of the compact ventricular myocardium as well as dissociation of the epicardium (* in f,h,j and l) was associated with impaired migration of WT1 positive EPDCs into the myocardium in the Pdgfrα−/− embryos (j, arrowheads in 1 and enlargements in boxes) compared to wildtype embryos (arrowheads in i,k). LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle. Scale bars: a–d = 200 μm, e–l = 100 μm

Stage E13.5

Examination of four stage E13.5 Pdgfrα−/− embryos revealed a variety of cardiac malformations (Table 1). In two mutants, the venous valves were shorter and thicker. The SAN (Figure 4b,d,g) was significantly smaller (37,0%, P<0.05) showing more Nkx2.5 positive cells (Figure 4f) compared to the wildtype (Figure 4a,c,e). A similar phenomenon was seen in the myocardium of the cardinal veins (Figure 4f). The myocardium of the dorsal atrial wall (Figure 4c–f) and the AS were hypoplastic. We could clearly discern a hypoplastic DMP. Three Pdgfrα−/− embryos showed abnormal orientation of the PV connection to the left atrium. In one mutant, the common PV ended blindly posterior to the atrial septum, as described previously (Bleyl et al. 2010).

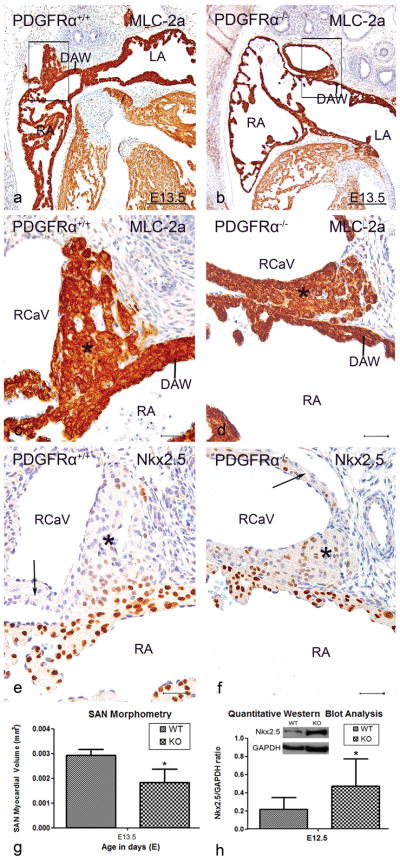

Figure 4. Altered Nkx2.5 expression in the Sinoatrial node.

At stage E13.5, sections show that the sinoatrial node (SAN) (asterisks) and myocardium of the cardinal vein (CaV) (arrow in e) were positive for MLC-2a (a,c) and negative for Nkx2.5 (e) in Pdgfrα+/+ embryos of stage E13.5. In the Pdgfrα−/− embryos (b,d,f) the SAN is significantly smaller (37,0%, P<0.05 (g)) and more Nkx2.5 positive cells were seen. The same accounts for the hypoplastic CaV myocardium (arrow in f), dorsal atrial wall (DAW) and atria. LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RCaV: right cardinal vein; RV, right ventricle (RV). Scale bars: a,b = 200 μm, c–f = 30 μm.

In three of the four Pdgfrα−/− embryos there was partial epicardial dissociation and incomplete epicardial covering, accompanied by hypoplasia of the compact ventricular myocardium (Figure 3c,d,g,h,k,l), being more severe on the right side. In the embryos with dissociated epicardium, almost no EPDCs had migrated into the underlying myocardium (Figure 3k,l) as shown by WT1 staining. The developing VS was hypoplastic (Figure 3c,d) and in 3/4 fenestrated.

Stage E14.5

At E14.5, expression of PDGFR-α has almost disappeared from the myocardium, expression was found in the SAN and myocardium of the cardinal veins (CaV) (Supplemental Figure IV a–i) Marked expression was also found in the epicardium covering the ventricles (Supplemental Figure IV a,b) with some scattered cells in the septum. The AV cushions and DMP mesenchyme still expressed the receptor (Supplemental Figure IV d,e). Remarkable was the expression in the endocardial and endothelial cells of the AV, semilunar and venous valves, specifically on the non flow side (Supplemental figure IV c,f,h). The myocardium of the PV was negative for PDGFRαGFP only the surrounding mesenchyme and myocardial cluster between the left LCaV and PV were positive (Supplemental Figure V).

In both PDGFRαGFP/GFP mutants (Table 1) there was hypoplasia of the SAN, the dorsal atrial wall, the AS and the DMP compared to the PDGFRαGFP control. The orientation of the PV connection to the left atrium was more caudal. In both PDGFRαGFP/GFP embryos, although dissociation and incomplete epicardial covering was not observed, there was diminished migration of WT1 positive EPDCs into the underlying hypoplastic myocardium. The VS was hypoplastic and fenestrated (Table 1).

Myocardial morphometry

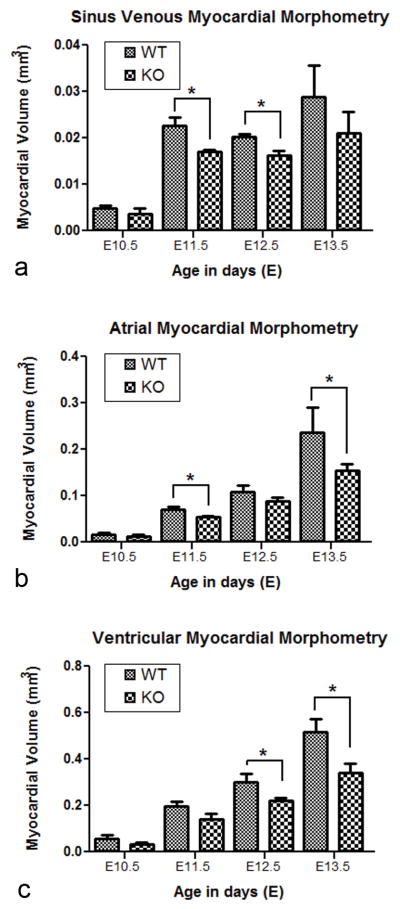

Morphometric analysis of the volume (mm3) of sinus venosus, atrial and ventricular myocardium of Pdgfrα−/− embryos was determined from E10.5–E13.5 (Figure 5). At stage E9.5, the volume of the atrial and ventricular myocardium was decreased by 47.5% (P<0.05) (Supplemental Figure VI) compared to wildtype. The volume of the sinus venosus myocardium was significantly decreased at stage E11.5 (24,7%) and E12.5 (20,6%) (P<0.05) (Figure 5a). At stage E11.5 and E13.5, the volume of the atrial myocardium was decreased by 21,8% and 34,9% (P<0.05) (Figure 5b), respectively. At E12.5 and E13.5 the ventricular walls were hypoplastic and the myocardial volume was significantly smaller (26,3% and 34,5%, respectively) (P<0.05) (Figure 5c).

Figure 5. Myocardial morphometry.

The myocardial volume of the sinus venosus (a), atrial (b) and ventricular myocardium (c) of Pdgfrα−/− (KO) embryos of embryonic day (E) 10.5 (n=3), E11.5 (n=3), E12.5 (n=3) and E13.5 (n=4) was compared to wildtype (WT) hearts of E10.5 (n=3), E11.5 (n=3), E12.5 (n=3) and E13.5 (n=3). Pdgfrα−/− embryos had a significantly (*) smaller sinus venosus myocardial volume (P<0.05) at stage E11.5 and E12.5 and a smaller atrial myocardial volume at E11.5 and E13.5 (P<0.05) compared to the wildtype embryos. The Pfgfrα knockout embryos also had a significantly (*) smaller ventricular myocardial volume (P<0.05).

Pdgfrα mutants show increased Nkx2.5 and WT1 expression

At stage E13.5, the SAN and myocardium of the cardinal veins of Pdgfrα deficient embryos contained more Nkx2.5 positive cells as compared to the wildtype which showed almost no Nkx2.5 expression. This increased number of Nkx2.5 positive cells suggested an interaction between PDGFR-α and Nkx2.5. Therefore, we performed Western blot analysis of the thorax of E12.5 embryos. This revealed 2,2 times higher Nkx2.5 protein levels in the Pdgfrα−/− embryos compared to the wildtype embryos (P<0.05) (Figure 4h).

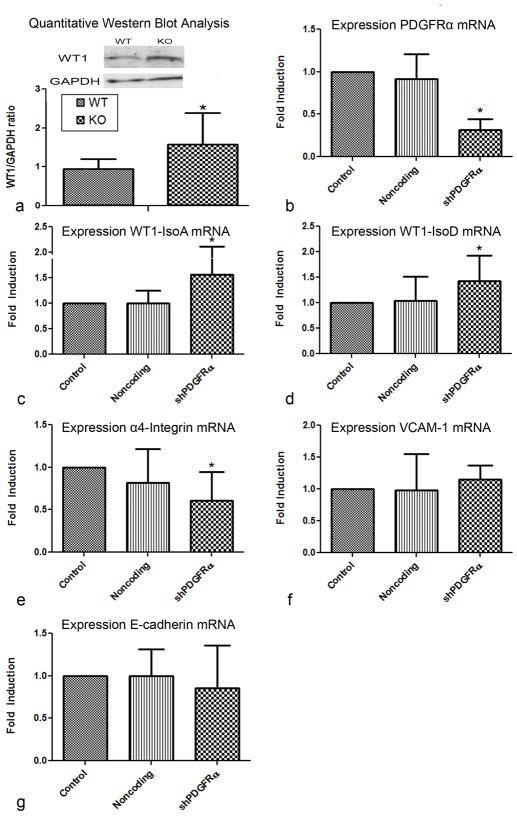

Also an interaction between PDGFR-α and WT1 was suggested by the seemingly diminished number of WT1 positive cells with a possible more intense expression of WT1. Analysis of the E12.5 knockout embryos by Western blot analysis for WT1 revealed increased protein levels of WT1 by 66,7% (P<0.05) in Pdgfrα−/− embryos (Figure 6a,b).

Figure 6. Inhibition of Pdgfrα alters expression of WT1.

Quantification of WT1 expression in E12.5 embryos by Western blot analysis. The WT1 expression increased significantly (*) by 66,7% (P<0.05) (a). Quantification of Pdgfrα mRNA expression was significantly (*) reduced in epicardial cells after induction of shRNA of Pdgfrα (P<0.05) (b). WT1 isoform A (c) and WT1 isoform D (d) mRNA expression in epicardial cells was increases significantly (P<0.05) after transduction of shRNA of Pdgfrα. The expression α4-integrin (ITGA4) (e) mRNA was significantly (*) decreased in RNA interference of Pdgfrα (P<0.05). The expression of VCAM-1 and E-cadherin mRNA did not show a significant change (f,g).

In vitro experiments were also performed to elucidate a possible interaction between PDGFR-α and WT1. We transduced human adult epicardial cells with an epithelium-like morphology also referred to as cobblestone-like EPDCs, that both express PDGFR-α and WT1, with shRNAs for Pdgfrα (shPdgfrα). qPCR analysis for Pdgfrα after transduction showed that shPdgfrα transduction decreased mRNA expression of Pdgfrα by 68,6% (P<0.05) (Figure 6c). Knockdown of Pdgfrα resulted in increased mRNA expression of WT1 of both isoforms A and D by 56,8% and 42,4% (P<0.05) (Figure 6c,d), respectively. So both protein and mRNA data show increased expression of WT1 in absence of PDGFR-α.

Pdgfrα−/− embryos of stage E12.5 and E13.5 showed dissociation and blebbing of the epicardium and diminished migration of EPDCs into the myocardium. The interaction between VCAM-1 and α4-Integrin has been reported to be important for the contact formation between the myocardium and epicardial cells and for the migration of EPDCs into the myocardium. PCR analysis showed that shPdgfrα transduction decreased the expression of α4-Integrin by 39,2% (P<0.05) (Figure 6e) and did not change the expression of VCAM-1 significantly (Figure 6f).

Since WT1 has been reported to transcriptionally regulate the expression of E-cadherin during the process of EMT, we analyzed the expression of E-cadherin in shPdgfrα transduced epicardial cells. PCR analysis showed that shPdgfrα did not change the expression of E-cadherin significantly (Figure 6g).

Discussion

PDGFs have been reported to play an important role in the cardiac development. This is based on both description of the normal expression pattern during development in avian (van den Akker et al. 2005; Bax et al. 2009) and in mouse embryos (Schatteman et al. 1992). Mutant mice supported this view specifically with regard to the disturbed role in neural crest contribution to the OFT (Price et al. 2001; Schatteman et al. 1995), related to neural crest abnormalities (Richarte et al. 2007).

This study concentrates on the possible role of Pdgfrα in development of the SHF, and specifically the region of the venous inflow also referred as the PFH, where we detected a marked expression in both mesenchyme and myocardium (Bax et al. 2009; Bleyl et al. 2010). This mesenchymal population is also the source of the epicardium which allowed us to study epicardial-myocardial interaction in the differentiation of the ventricular wall.

Altered addition of myocardium at the venous pole of the heart

The sinus venosus myocardium is composed of several components, the SAN, dorsal atrial wall, the wall of the pulmonary and cardinal veins. It is distinguished by expression of MLC-2a, T-box transcription factor gene Tbx18, podoplanin, PDGFR-α (Bax et al. 2009; Mahtab et al. 2009; Christoffels et al. 2006) and the absence of Nkx2.5 (Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 2007; Christoffels et al. 2006). Our analysis of Pdgfrα−/− embryos revealed hypoplasia of the sinus venosus myocardium including the SAN accompanied by increased expression of Nkx2.5. Nkx2.5 is required to distinguish working atrial from sinoatrial myocardium and ectopic expression results in bradycardia (Blaschke et al. 2007; Espinoza-Lewis et al. 2009) and aberrant expression of Cx43, suggesting that upregulation of Nkx2.5 results in deregulation of the genetic program controlling sinus nodal function (Blaschke et al. 2007; Espinoza-Lewis et al. 2009; Pashmforoush et al. 2004). The increased expression of Nkx2.5 in Pdgfrα−/− embryos, in vivo seen in the SAN and myocardium of the cardinal veins and supported by Western blot analysis, suggests a role for Pdgfrα in SAN pacemaking development. It is, however, not clear whether Nkx2.5 expression is directly regulated by Pdgfrα or that this is a downstream event as Pdgfrα signaling activates a number of transduction pathways. A functional link between Pdgfrα and Nkx2.5 has recently been described in Nkx2.5−/− embryos with a 2-fold increase in Nkx2.5-GFP+/Pdgfrα+ progenitor cells (Prall et al. 2007).

The hypoplasia of the myocardium of the dorsal atrial wall as well as the atrial septum (AS) in the Pdgfrα−/− embryos is probably due to diminished SHF-derived myocardial contribution. The atrial septum as well as the overlying mesenchymal cap both were positive for PDGFRαGFP.

Diminished contribution of the DMP in cardiac development

PDGFR-α expression as reported by GFP, in the PDGFRαGFP knockin mice, was observed in the DMP. This population of extracardiac mesenchyme arises from the SHF (Snarr et al. 2007a) and is hypoplastic in Pdgfrα−/− embryos (Bleyl et al. 2010).

Myocardial transition of the DMP is regulated by Nkx2.5 and occurs by a mesenchymal-to-myocardial differentiation of SHF-derived cells (Snarr et al. 2007a). We postulate that early onset of myocardial differentiation of the DMP could lead to hypoplasia of the DMP. This explains, in combination with the hypoplasia of the atrial septum and the mesenchymal cap, the failed fusion within the AV septal complex which can lead to AVSD (Blom et al. 2003), as we observed in the Pdgfrα−/− embryos.

Abnormal PV development

Dysregulation of Pdgfrα also caused abnormal orientation of the PV connection to the left atrium and other inflow tract anomalies including TAPVR (Bleyl et al. 2010), suggesting a role for Pdgfrα-signaling in PV development. The wall of the PV is formed from the surrounding mesodermal precursors in the dorsal mesocardium postulated to be derived from the PHF (Gittenberger-de Groot et al. 2007). As the expression of PDGFR-α was only seen in the mesenchyme surrounding the myocardium of the PV, we postulate that the altered incorporation and diminished myocardial contribution to the wall of the PV (Bleyl et al. 2010) could be caused by altered mesenchymal-myocardial interaction. This altered interaction could cause an abnormal differentiation rate of PV myocardium due to increased Nkx2.5 expression. Indeed, pulmonary myocardial formation is described to be regulated by Nkx2.5 expression, preceding the expression of markers for differentiated myocytes (Mommersteeg et al. 2007).

Patients with abnormal PV development often show conduction abnormalities, including sinus node dysfunction (sick sinus syndrome and bradycardia) (Korbmacher et al. 2001). Hypoplasia of pulmonary venous myocardium and the sinus node in TAPVR patients could be the cause of these arrhythmias. It would be interesting to study patients with TAPVR, due to dysregulation of Pdgfrα, for conduction abnormalities related to increased Nkx2.5 expression (Pashmforoush et al. 2004).

Impaired PEO development, epicardial adhesion and migration

The PEO develops from the coelomic mesothelium at the venous pole of the heart (Lie-Venema et al. 2007). The hypoplasia of the PEO in the Pdgfrα mutants is most probably due to diminished addition of mesenchyme from the PHF. After attachment to the myocardial heart tube, cells spread out to cover the complete heart. The epicardial dissociation or blebbing observed in Pdgfrα−/− embryos resembles that in RXRα−/− embryos (Jenkins et al. 2005) and may be caused by many mechanisms (Lie-Venema et al. 2007) including altered Integrin/VCAM interaction, important for epicardial adhesion. In RXRα−/− embryos lower expression of myocardial VCAM-1 disturbed the Integrin/VCAM interaction (Kang and Sucov 2005). Our in vitro data showed that this pathway is also affected in the Pdgfrα mutants as shPdgfrα mediated knockdown of the receptor decreased α4-integrin mRNA expression. The expression of VCAM-1 mRNA did not change after shPdgfrα transduction in epicardial cells, as is described that VCAM-1 is mainly expressed in the myocardium (Kang and Sucov 2005). This supports a role for Pdgfrα-integrin-signaling needed for correct PEO development, epicardial adhesion and migration.

Impaired migration of EPDCs

The most important process for the formation and migration of EPDCs is EMT. Analysis of Pdgfrα−/− embryos revealed disturbed EMT and diminished migration of EPDCs. A transcription factor that is involved in EMT of EPDCs is Snail, which represses cell adhesion molecules including E-cadherin and thereby stimulating EMT. A recent paper showed that expression of Snail and E-cadherin is controlled by WT1 (Martinez-Estrada et al. 2010), a transcription factor essential for the development of EPDCs (Perez-Pomares et al. 2002). However, the expression of E-cadherin is not altered in shPdgfrα transduced human adult epicardial cells with an epithelium-like morphology in which the expression of WT1 is increased. Therefore, the effect of WT1 overexpression on E-cadherin expression is not directly correlated to the effect of WT1 knockdown as described previously (Martinez-Estrada et al. 2010). Cardiac malformations such as hypoplasia of ventricular myocardium and altered AV cushion development observed in Pdgfrα−/− embryos are comparable to models with a downregulation of WT1 expression, like WT1 and Sp3 mutants (Van Loo et al. 2007; Perez-Pomares et al. 2002). A link between PDGFR-α and WT1 is suggested because both are coexpressed in the epicardium and EPDCs during heart development (Mellgren et al. 2008; Perez-Pomares et al. 2002) and confirmed by our present morphological analysis of Pdgfrα mutants in which the number of WT1 expressing cells was less compared to the control. With Western blot analysis and in vitro knockdown experiments, however, we proved an increase of WT1 expression in the absence of Pdgfrα. This might be explained by a higher expression per cell. It is not clear at this stage whether WT1 expression is directly regulated by the Pdgfrα-signaling pathway or if this is a downstream event within a more extensive pathway.

Conclusion

Our data demonstrate the essential role of Pdgfrα in cardiac development, especially for the addition of the myocardial and mesenchymal components of the PHF at the venous pole of the heart. Furthermore, we have established a possible functional link between Pdgfrα and the expression of Nkx2.5 in the SAN. A functional link was also established between Pdgfrα and the expression of WT1 which leads to abnormal epicardial development. Therefore, we implicate a role for Nkx2.5 and WT1 in Pdgfrα-regulated myocardial differentiation and remodeling. Our finding that Pdgfrα mutants show marked upregulation of Nkx2.5 and WT1 provides new insight in a possible role of Pdgfrα as part of transduction pathway repressing Nkx2.5 and WT1 in the development of PHF-derived cardiac structures. This presents an opportunity for further study.

Experimental procedure

Generation of Pdgfrƒα−/− and eGFP Mice and harvesting of embryos

The Pdgfrα knockout mice have been described previously (Soriano 1997; Tallquist and Soriano 2003). Pdgfrα deficient embryos are embryonic lethal, dying in two waves. Approximately 60% die by E8.5 of unknown causes and the remainder die by E16.5 with multiple defects including cardiac anomalies, cleft face, neural tube defects, body wall defects and hemorrhages (Orr-Urtreger and Lonai 1992; Price et al. 2001; Soriano 1997) (Orr-Urtreger and Lonai 1992). Pdgfrα−/+ heterozygotes are viable and fertile and these mice were crossed to obtain Pdgfrα−/− embryos and Pdgfrα+/+ (wildtype) littermates. Pdgfrα-animals were housed in the animal facility under standard conditions. All procedures were carried out following approval from the Institutional Animal and Use committee at the University of Utah School of Medicine and in accordance with institutional policies.

PDGFR-α knock-in mutants (B6.129S4-Pdgfrαtm11(EGFP)Sor/J), in which an allele of the PDGFR-α expresses a nuclear localized H2B-eGFP fusion gene from the endogenous Pdgfrα locus (PDGFRαGFP) (Soriano 1997; Tallquist and Soriano 2003) were used to investigate the spatial and temporal expression of this receptor. The endogenous Pdgfrα promoter drives expression of the H2B-eGFP fusion gene. PDGFRαGFP/GFP embryos, in which both alleles of the PDGFR-α expresses a nuclear localized green fluorescent protein from the Pdgfrα locus, were used in this study at stage E14.5 as Pdgfra−/−. The PDGFRαGFP and PDGFRαGFP/GFP animals were housed in the Scheele Animal Facility at MBB, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, under standard conditions. All procedures were carried out following approval from the animal ethical board of Northern Stockholm and in accordance with institutional policies.

In both institutes, the morning of the vaginal plug after crossing the animals was stated as embryonic day (E) 0.5. Pregnant females were sacrificed and embryos were harvested and the thorax was isolated. PCR genotyping in both institutes was performed on yolk sac DNAs with several primers as described previous (Imamoto and Soriano 1993; Bleyl et al. 2010) (Imamoto and Soriano 1993). The collected embryos were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24–48 hours and further processed for paraffin immunohistochemical investigation. Subsequently, 5 μm serial sections were mounted on egg white/glycerine-coated microscope slides (Menzel-Gläser).

Immunohistochemistry

Serial sections were subjected to standard immunohistochemical procedures (Mahtab et al. 2008; van den Akker et al. 2005; van den Akker et al. 2005; Mahtab et al. 2008). Briefly, after rehydration of the slides, inhibition of endogenous peroxidase was performed with a solution of 0.3% H2O2 in PBS for 20 min. Microwave antigen retrieval was applied for the GFP, WT1 and Nkx2.5 staining, by heating the sections (12 min to 98°C) in citric acid buffer (0.01 Mol/L, pH 6.0). Sections were incubated overnight with primary antibodies against: HHF35 (actin), M0635, Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; MLC-2a, a kind gift of Dr. S.W. Kubalak, Charleston, USA; Nkx2.5, SC-8697, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, USA; Wilm’s tumor suppressor protein 1 (WT1), CA1026, Calbiochem, USA; GFP, A11122, Molecular probes, Eugene, USA. Subsequently, the slides were incubated with a secondary biotin-labeled goat-anti-rabbit (BA-1000, Vector Labs) or horse-anti-goat (BA-9500, Vector Labs) in combination with normal goat serum (S-1000, Vector Labs) or normal horse serum (S-2000, Vector Labs) for 1 hr, respectively. Additional incubation with Vectastain ABC staining kit (PK-6100, Vector Labs) for 45 min was performed. For visualization, slides were rinsed in PBS and Tris/Maleate (pH 7.6). 3-3′ diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) (D5637, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as chromogen and Mayer’s haematoxylin as counterstaining. Finally, all slides were dehydrated and mounted with Entellan (Merck).

3D-reconstruction

We made 3-D reconstructions of the atrial and ventricular myocardium with the use of MLC-2a stained sections of wildtype as well as Pdgfrα−/− embryos. The 3-D reconstruction of the mesenchymal cap was also made with the use of the MLC-2a staining. The 3D- reconstructions of the proepicardial organ (PEO) were based on WT1 staining of E9.5 embryos. The reconstructions were made as described earlier (Jongbloed et al. 2004; Mahtab et al. 2008) with the use of the AMIRA software package (Template Graphics Software, San Diego, USA).

Morphometric analysis

The morphometric analysis was performed on the PEO, sinus venosus, atrial and ventricular myocardium and on the mesenchymal cap. The PEO volume estimation was performed in 3 wildtype and 4 Pdgfrα−/− mutant hearts of E9.5. The myocardial volume estimation was also performed in at least 3 wildtype and 3 knockout hearts per embryonic stage E9.5–E13.5. For the analysis of the mesenchymal cap, embryos of stage E11.5 were used. For all the mentioned cardiac structures we used the Cavalieri’s principle as described by Gundersen and colleagues (Gundersen H.J. and Jensen E.B. 1987). Briefly, regularly spaced points (70mm2 for stage E9.5–E11.5 and 100mm2 for the other stages) were randomly positioned on the MLC-2a stained myocardium and on the WT1 stained PEO. The distance between the subsequent sections on the slides was 0.020mm for stage E9.5 and E10.5, for the older stages there was a distance of 0.025mm between the subsequent sections. For the volume measurement we used the HB2 Olympus microscope with a 40x or 100x magnification objective for myocardium and 200x for PEO and mesenchymal cap.

Western Blotting

For total protein extraction, the thorax of 4 wildtype and 4 knockout embryos of stage E12.5 was flash frozen and homogenized in Tripure isolation reagent (Roch Applied Science). Protein concentrations were determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay. Homogenates were size-fractionated on 10% PAGE gels and transferred to Hybond PVDF membranes. After blocking non-specific binding sites, membranes were incubated overnight with the anti-WT1 (CA1026, Calbiochem) and anti-Nkx2.5 (Nkx2.5, SC-14033, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies followed by incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled secondary antibody (goat anti-rabbit or rabbit anti-goat) for 1 hour. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Chemiluminescence was induced by ECL Advanced Detection reagent and detected by exposure to Hyperfilm ECL. WT1, Nkx2.5 and GAPDH bands were quantified by Quantity One image analysis software.

Cells and cell culture

Epicardial cells were isolated from human atrial appendages as described previously (van Tuyn et al. 2007). Briefly, epicardium was removed from the adult atrial tissue and minced into small pieces. Epicardial pieces were cultured in medium containing 45% DMEM, 45% M199, 10% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (FCSi), 100U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen) and 2 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF, BD Biociences). The epicardial pieces were removed from the culture dish as soon as outgrowth of cells was visible. Medium was refreshed every 3 days. Epicardial cels with an epithelium-like morphology from passage 3–4 were used for lentiviral transductions.

RNA interference

Epicardial cells cultured from atrial appendages of three different patients were transduced with shRNAs. Three lentiviral clones were used for shRNA-mediated Pdgfrα knockdown or a scrambled sequence as a control was used, all obtained from the MISSION-library (Sigma). Cells were transduced with shRNA lentivirus in the presence of 4ug/ml polybrene for 6 hours. Three days after puromycin (1 ug/ml) selection, transduced cells were collected for RNA isolation.

mRNA isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA from transfected epicardial cells was isolated by using Nucleospin RNAII (Macherey-Nagel) as described by the manufacturer. cDNA was synthesized with 750 ng RNA per sample, using iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). cDNA samples were subjected to quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR). Primers were designed with Primer 3 and qPrimerDepot (htp://primerdepot.nci.nih.gov/) and synthesized by Eurogentec (Seraing, Belgium). Primer sequences and annealing temperatures are available on request. PCR conditions were: 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 30 seconds at 95°C, 30 seconds annealing temperature (60°C) and 30 seconds at 72°C. All samples were normalized for input based on housekeeping gene β-actin, which was not influenced by the different shRNAs (data not shown).

Statistics

Statistical analysis on the volume measurement and Western blot analysis were performed with independent sample t-test. All data of the volume measurements are presented as average ± SD. The PCR data were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method, by comparing signal of the shRNA-treated groups with that of the control group, both relative to an internal control, β-actin. Analysis of the qRT-PCR data were performed with ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis for group comparisons. Significance was assumed when P<0.05 using SPSS 16.0 software program (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA). Graphics of statistical analysis were composed by Graphpad software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by a NIH grant NHLBI HL 84559-01 to SB Bleyl.

We thank Dr. A.G. Jochemsen (Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, LUMC, Leiden, the Netherlands) for his technical assistance with the WT1 Western blots.

Reference List

- Bax NA, Lie-Venema H, Vicente-Steijn R, Bleyl SB, Van Den Akker NM, Maas S, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Platelet-derived growth factor is involved in the differentiation of second heart field-derived cardiac structures in chicken embryos. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:2658–2669. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke RJ, Hahurij ND, Kuijper S, Just S, Wisse LJ, Deissler K, Maxelon T, Anastassiadis K, Spitzer J, Hardt SE, Schöler H, Feitsma H, Rottbauer W, Blum M, Meijlink F, Rappold GA, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Targeted mutation reveals essential functions of the homeodomain transcription factor Shox2 in sinoatrial and pacemaking development. Circulation. 2007;115:1830–1838. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.637819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleyl SB, Saijoh Y, Bax NA, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Wisse LJ, Chapman SC, Hunter J, Shiratori H, Hamada H, Yamada S, Shiota K, Klewer SE, Leppert MF, Schoenwolf GC. Dysregulation of the PDGFRA gene causes inflow tract anomalies including TAPVR: integrating evidence from human genetics and model organisms. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:1286–1301. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blom NA, Ottenkamp J, Wenink AG, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Deficiency of the vestibular spine in atrioventricular septal defects in human fetuses with down syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2003;91:180–184. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03106-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels VM, Mommersteeg MT, Trowe MO, Prall OW, Gier-de Vries C, Soufan AT, Bussen M, Schuster-Gossler K, Harvey RP, Moorman AF, Kispert A. Formation of the venous pole of the heart from an Nkx2-5-negative precursor population requires Tbx18. Circ Res. 2006;98:1555–1563. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000227571.84189.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettman RW, Denetclaw W, Ordahl CP, Bristow J. Common epicardial origin of coronary vascular smooth muscle, perivascular fibroblasts, and intermyocardial fibroblasts in the avian heart. Dev Biol. 1998;193:169–181. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eralp I, Lie-Venema H, DeRuiter MC, Van Den Akker NM, Bogers AJ, Mentink MM, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Coronary artery and orifice development is associated with proper timing of epicardial outgrowth and correlated Fas ligand associated apoptosis patterns. Circ Res. 2005;96:526–534. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000158965.34647.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza-Lewis RA, Yu L, He F, Liu H, Tang R, Shi J, Sun X, Martin JF, Wang D, Yang J, Chen Y. Shox2 is essential for the differentiation of cardiac pacemaker cells by repressing Nkx2-5. Dev Biol. 2009;327:376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Mahtab EA, Hahurij ND, Wisse LJ, DeRuiter MC, Wijffels MC, Poelmann RE. Nkx2.5 negative myocardium of the posterior heart field and its correlation with podoplanin expression in cells from the developing cardiac pacemaking and conduction system. Anat Rec. 2007;290:115–122. doi: 10.1002/ar.20406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vrancken Peeters M-P, Bergwerff M, Mentink MM, Poelmann RE. Epicardial outgrowth inhibition leads to compensatory mesothelial outflow tract collar and abnormal cardiac septation and coronary formation. Circ Res. 2000;87:969–971. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.11.969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vrancken Peeters M-P, Mentink MM, Gourdie RG, Poelmann RE. Epicardium-derived cells contribute a novel population to the myocardial wall and the atrioventricular cushions. Circ Res. 1998;82:1043–1052. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.10.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen HJ, Jensen EB. The efficiency of systematic sampling in stereology and its prediction. J Microscopy. 1987;147:229–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1987.tb02837.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imamoto A, Soriano P. Disruption of the csk gene, encoding a negative regulator of Src family tyrosine kinases, leads to neural tube defects and embryonic lethality in mice. Cell. 1993;73:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90641-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins SJ, Hutson DR, Kubalak SW. Analysis of the proepicardium-epicardium transition during the malformation of the RXRalpha−/− epicardium. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:1091–1101. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongbloed MR, Schalij MJ, Poelmann RE, Blom NA, Fekkes ML, Wang Z, Fishman GI, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Embryonic conduction tissue: a spatial correlation with adult arrhythmogenic areas? Transgenic CCS/lacZ expression in the cardiac conduction system of murine embryos. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:349–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JO, Sucov HM. Convergent proliferative response and divergent morphogenic pathways induced by epicardial and endocardial signaling in fetal heart development. Mech Dev. 2005;122:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly RG. Molecular inroads into the anterior heart field. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2005;15:51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbmacher B, Buttgen S, Schulte HD, Hoffmann M, Krogmann ON, Rammos S, Gams E. Long-term results after repair of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;49:101–106. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-11706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwee L, Baldwin HS, Min Shen H, Stewart CL, Buck C, Buck CA, Labow MA. Defective development of the embryonic and extraembryonic circulatory systems in vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) deficient mice. Development. 1995;121:489–503. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lie-Venema H, van den Akker NM, Bax NA, Winter EM, Maas S, Kekarainen T, Hoeben RC, DeRuiter MC, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Origin, fate, and function of epicardium-derived cells (EPCDs) in normal and abnormal cardiac development. Scientific World Journal. 2007;7:1777–1798. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2007.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtab EA, Vicente-Steijn R, Hahurij ND, Jongbloed MR, Wisse LJ, DeRuiter MC, Uhrin P, Zaujec J, Binder BR, Schalij MJ, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Podoplanin deficient mice show a Rhoa-related hypoplasia of the sinus venosus myocardium including the sinoatrial node. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:183–193. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahtab EA, Wijffels MC, van den Akker NM, Hahurij ND, Lie-Venema H, Wisse LJ, DeRuiter MC, Uhrin P, Zaujec J, Binder BR, Schalij MJ, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Cardiac malformations and myocardial abnormalities in podoplanin knockout mouse embryos: correlation with abnormal epicardial development. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:847–857. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Estrada OM, Lettice LA, Essafi A, Guadix JA, Slight J, Velecela V, Hall E, Reichmann J, Devenney PS, Hohenstein P, Hosen N, Hill RE, Munoz-Chapuli R, Hastie ND. Wt1 is required for cardiovascular progenitor cell formation through transcriptional control of Snail and E-cadherin. Nat Genet. 2010;42:89–93. doi: 10.1038/ng.494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellgren AM, Smith CL, Olsen GS, Eskiocak B, Zhou B, Kazi MN, Ruiz FR, Pu WT, Tallquist MD. Platelet-Derived Growth Factor Receptor {beta} Signaling Is Required for Efficient Epicardial Cell Migration and Development of Two Distinct Coronary Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Populations. Circ Res. 2008;103:1393–1401. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merki E, Zamora M, Raya A, Kawakami Y, Wang J, Zhang X, Burch J, Kubalak SW, Kaliman P, Belmonte JC, Chien KR, Ruiz-Lozano P. Epicardial retinoid X receptor alpha is required for myocardial growth and coronary artery formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:18455–18460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504343102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mommersteeg MT, Brown NA, Prall OW, de Gier-de VC, Harvey RP, Moorman AF, Christoffels VM. Pitx2c and Nkx2-5 Are Required for the Formation and Identity of the Pulmonary Myocardium. Circ Res. 2007;101:902–909. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.161182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr-Urtreger A, Lonai P. Platelet-derived growth factor-A and its receptor are expressed in separate, but adjacent cell layers of the mouse embryo. Development. 1992;115:1045–1058. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.4.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashmforoush M, Lu JT, Chen H, Amand TS, Kondo R, Pradervand S, Evans SM, Clark B, Feramisco JR, Giles W, Ho SY, Benson DW, Silberbach M, Shou W, Chien KR. Nkx2-5 pathways and congenital heart disease; loss of ventricular myocyte lineage specification leads to progressive cardiomyopathy and complete heart block. Cell. 2004;117:373–386. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00405-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Pomares JM, Phelps A, Sedmerova M, Carmona R, Gonzalez-Iriarte M, Munoz-Chapuli R, Wessels A. Experimental Studies on the Spatiotemporal Expression of WT1 and RALDH2 in the Embryonic Avian Heart: A Model for the Regulation of Myocardial and Valvuloseptal Development by Epicardially Derived Cells (EPDCs) Dev Biol. 2002;247:307–326. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prall OW, Menon MK, Solloway MJ, Watanabe Y, Zaffran S, Bajolle F, Biben C, McBride JJ, Robertson BR, Chaulet H, Stennard FA, Wise N, Schaft D, Wolstein O, Furtado MB, Shiratori H, Chien KR, Hamada H, Black BL, Saga Y, Robertson EJ, Buckingham ME, Harvey RP. An Nkx2-5/Bmp2/Smad1 negative feedback loop controls heart progenitor specification and proliferation. Cell. 2007;128:947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RL, Thielen TE, Borg TK, Terracio L. Cardiac Defects Associated with the Absence of the Platelet-derived Growth Factor alpha Receptor in the Patch Mouse. Microsc Microanal. 2001;7:56–65. doi: 10.1017.S1431927601010054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richarte AM, Mead HB, Tallquist MD. Cooperation between the PDGF receptors in cardiac neural crest cell migration. Dev Biol. 2007;306:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatteman GC, Morrison-Graham K, van Koppen A, Weston JA, Bowen-Pope DF. Regulation and role of PDGF receptor α-subunit expression during embryogenesis. Development. 1992;115:123–131. doi: 10.1242/dev.115.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatteman GC, Motley ST, Effmann EL, Bowen-Pope DF. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha subunit deleted patch mouse exhibits severe cardiovascular dysmorphogenesis. Teratology. 1995;51:351–366. doi: 10.1002/tera.1420510602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengbusch JK, He W, Pinco KA, Yang JT. Dual functions of [alpha]4[beta]1 integrin in epicardial development: initial migration and long-term attachment. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:873–882. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200203075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snarr BS, O’Neal JL, Chintalapudi MR, Wirrig EE, Phelps AL, Kubalak SW, Wessels A. Isl1 expression at the venous pole identifies a novel role for the second heart field in cardiac development. Circ Res. 2007a;101:971–974. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snarr BS, Wirrig EE, Phelps AL, Trusk TC, Wessels A. A spatiotemporal evaluation of the contribution of the dorsal mesenchymal protrusion to cardiac development. Dev Dyn. 2007b;236:1287–1294. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano P. The PDGFα receptor is required for neural crest cell development and for normal patterning of the somites. Development. 1997;124:2691–2700. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.14.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallquist MD, Soriano P. Cell autonomous requirement for PDGFRalpha in populations of cranial and cardiac neural crest cells. Development. 2003;130:507–518. doi: 10.1242/dev.00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Akker NM, Lie-Venema H, Maas S, Eralp I, DeRuiter MC, Poelmann RE, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Platelet-derived growth factors in the developing avian heart and maturating coronary vasculature. Developmental Dynamics. 2005;233:1579–1588. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Loo PF, Mahtab EA, Wisse LJ, Hou J, Grosveld F, Suske G, Philipsen S, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Transcription Factor Sp3 knockout mice display serious cardiac malformations. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8571–8582. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01350-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Tuyn J, Atsma DE, Winter EM, van der Velde-van Dijke, Pijnappels DA, Bax NA, Knaan-Shanzer S, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Poelmann RE, van Der Laarse A, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ, de Vries AA. Epicardial cells of human adults can undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and obtain characteristics of smooth muscle cells in vitro. Stem Cells. 2007;25:271–278. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.