Abstract

The contribution of direct and indirect alloresponses by CD4+ Th1 and Th2 cells in acute and chronic rejection of allogeneic transplants remains unclear. In the present study, we addressed this question using a transplant model in a single MHC class I-disparate donor–recipient mouse combination. BALB/c-dm2 (dm2) mutant mice do not express MHC class I Ld molecules and reject acutely Ld+ skin grafts from BALB/c mice. In contrast, BALB/c hearts placed in dm2 mice are permanently accepted in the absence of chronic allograft vasculopathy. In this model, CD4+ T cells are activated following recognition of a donor MHC class I determinant, Ld 61–80, presented by MHC Class II Ad molecules on donor and recipient APC. Pre-transplantation of recipients with Ld 61–80 peptide emulsified in complete Freund’s adjuvant induced a Th1 response, which accelerated the rejection of skin allografts, but it had no effect on cardiac transplants. In contrast, induction of a Th2 response to the same peptide abrogated the CD8+ cytotoxic T cells response and markedly delayed the rejection of skin allografts while it induced de novo chronic rejection of heart transplants. This shows that Th2 cells activated via indirect allorecognition can exert dual effects on acute and chronic rejection of allogeneic transplants.

Keywords: Chronic graft rejection, Heart transplantation, Skin graft, T-cell allorecognition, Th1/Th2 cells

Introduction

Transplantation of allogeneic tissues triggers a vigorous inflammatory immune response that is initiated via the recognition of donor Ag by the recipient CD4+ T lymphocytes. Such T-cell allorecognition is mediated via two distinct pathways: the direct pathway in which T cells are stimulated by intact allogeneic MHC II molecules displayed on donor APC [1, 2] and the indirect pathway in which T cells interact with processed alloantigen peptides presented by self-MHC II molecules at the surface of recipient APC [3–5].

In direct alloreactivity, donor bone marrow-derived passenger leukocytes present a multitude of peptides in an MHC class II context thereby eliciting a polyclonal CD4+ T-cell response in the host’s lymphoid organs. Likewise, it is traditionally accepted that this reaction represents the driving force behind early acute graft rejection. Alternatively, the indirect T-cell alloresponse is oligoclonal in that it is mediated by a selected set of alloreactive T-cell clones recognizing a few dominant peptides presented by self-MHC [6, 7]. Despite its low frequency, the indirect alloresponse is sufficient to ensure acute rejection of skin allotransplants [8, 9]. However, it is unclear whether, in the absence of a direct CD4+ T-cell alloresponse, indirect alloreactivity can mediate on its own acute rejection of less immunogenic vascularized solid organ transplants, including kidneys and hearts. This presumably depends upon the strength of the indirect response and its ability to promote the differentiation of functional alloreactive CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (CTL).

Early acute allograft rejection of solid organ transplants can be prevented with immunosuppressive drugs such as calcineurin inhibitors. However, a large portion of heart, lung and kidney transplants ultimately succumb to chronic rejection, a slow process involving perivascular inflammation, fibrosis and arteriosclerosis associated with intimal thickening and subsequent luminal occlusion of graft vessels [10–12]. It is believed that the CD4+ T-cell direct alloresponse gradually fades away after transplantation as donor passenger leukocytes vanish. In contrast, the indirect alloresponse is perpetuated via spreading to formerly cryptic determinants on alloantigens and graft tissue-specific Ag [13–18]. Also, indirect alloreactivity is thought to play a critical role in the production of alloantibodies [19–21] that are known mediators of the chronic rejection process [22–26]. Therefore, there is strong circumstantial evidence suggesting that indirect rather than direct type of alloreactivity initiates chronic rejection of allografts. In support of this view, some correlation between the presence of indirect alloreactivity and chronic rejection has been reported [27–31]. Additionally, a study by Madsen’s group shows that immunization with a donor MHC peptide can accelerate the onset of chronic allograft vasculopathy in heart-transplanted miniature swines [32]. However, there is still no formal demonstration that the indirect alloresponse by CD4+ T cells is necessary and/or sufficient to induce de novo chronic rejection of organ allotransplants.

Here, we investigated the contribution of alloreactivity by Th1 and Th2 cells to the acute and chronic allograft rejection of skin and heart transplants in a single MHC class I-disparate donor/recipient (BALB/c to BALB/c-dm2 (dm2)) mouse combination. In this model, skin allografts are acutely rejected within 10 days post-transplantation while heart transplants are accepted permanently without signs of chronic rejection. We observed that induction of a pro-inflammatory Th1 response to a dominant MHC class I allopeptide (Ld 61–80) accelerated acute rejection of skin but it did not provoke the rejection of heart allotransplants. In contrast, while immune deviation of the alloreactivity toward a Th2 response markedly delayed acute rejection of skin allografts by Th1 cells, it triggered chronic rejection of cardiac transplants. This shows that Th2 cells can exert dual effects on acute and chronic forms of allograft rejection. The implications of these findings for the design of selective immune therapies in allotransplantation are discussed.

Results

Immunogenicity of Ld 61–80 allopeptide in transplanted and naive BALB/c-dm2 mice

dm2 mice are BALB/c mice lacking expression of the Ld MHC class I molecule due to a mutation in the 3′ region of the corresponding gene. Consequently, dm2 mice recognize the Ld molecule as foreign and reject acutely WT BALB/c skin grafts. Here, we used this model to study the immune physiology of transplant rejection in a single MHC class I-mismatched donor/recipient combination.

We have previously shown that the third polymorphic region of MHC class I glycoproteins (region 61–80) contains a dominant determinant that is presented in indirect fashion, i.e. by recipient dm2 APC to recipient CD4+ T cells after allotransplantation in mice [33, 34]. In addition, the Ld 61–80 peptide is naturally processed by BALB/c APC and continuously presented by Ad MHC class II molecules. Therefore, CD4+ T cells from dm2-transplanted mice could also recognize the Ld peptide on donor APC via a process that can be referred to as “semi-direct allorecognition.”

First, we measured the immunogenicity of the Ld 61–80 peptide in naive and transplanted dm2 mice. Naive dm2 mice were immunized subcutaneously with the peptide Ld 61–80 emulsified in CFA. Ten days later, CD4+ T cells from regional lymph nodes were isolated and incubated in vitro for 24 h with the immunizing peptide Ld 61–80 or a control hen eggwhite lysozyme (HEL) binding peptide, HEL 105–120. The frequencies of activated T cells producing IL-2 and IFN-γ (type 1 cytokines) and IL-4 and IL-5 (type 2 cytokines) were determined by ELISPOT. As shown in Fig. 1A, immunization with Ld allopeptide induced a potent inflammatory type 1 cytokine CD4+ T-cell response in dm2 mice (> 100 spots/million T cells). A few activated type 2 IL-4-producing T cells were also detected (15 ± 3 spots per million T cells). No response was found in non-immunized mice or in the Ld 61–80 peptide-immunized mice restimulated in vitro with the irrelevant HEL 46–61 peptide (<3 spots/million T cells).

Figure 1.

T-cell response of dm2 mice immunized with Ld 61–80 peptide emulsified in CFA. dm2 mice were injected subcutaneously in the hind foootpad with Ld 61–80 peptide (100 ug) emulsified in CFA. Ten days later, draining popliteal LN T cells were collected and tested for cytokine production by ELISPOT and for cytotoxic response against various targets. (A) T cells were cultured in vitro with the immunizing Ag (Ld 61–80, solid bars) or with a control Ag (HEL 46–61, hatched bars). Control non-immunized mice are shown as white bars. The results are presented as spots per million T cells + SD for each cytokine. The results are representative of five mice tested individually. CTL responses of mice immunized with Ld 61–80 peptide (B), no peptide (C), and control OVA 323–339 peptide (D). The ability of T cells to kill allogeneic Ld+ (BALB/c, squares), Ld (B6, circles) and control syngeneic (dm2, triangles) are shown. Spontaneous release ranged from 10 to 15% of maximal release. Data are representative of three independent experiments including 4–5 mice tested individually.

Next, CD8+ T cells from Ld 61–80-immunized mice were isolated and tested for their ability to kill target cells presenting the allopeptide. These CD8+ T cells could also kill allogeneic BALB/c target cells in the absence of any exogenously added peptide (Fig. 1B). No CTL response was detected with syngeneic Ld-deficient dm2 targets or with irrelevant B6 (H-2b) allogeneic cells. Non-immunized dm2 mice (Fig. 1C) as well as dm2 mice immunized with control OVA 323–339 peptide (Fig. 1D) did not mount a CTL response to BALB/c allogeneic cells. It is noteworthy that, in this model, dm2 targets pulsed with the Ld peptide were also killed by CD8+ T cells, a result we previously reported [35]. This suggests that the Ld peptide can be presented by Kd or Dd on dm2 APC.

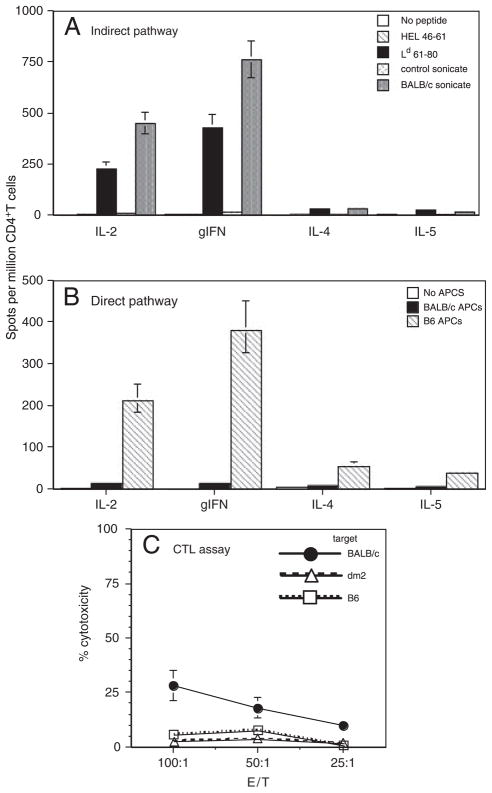

In another set of experiments, (Ld−) dm2 mice were transplanted with skins from (Ld+) BALB/c mice. At the time of rejection (10–12 days post-transplantation), T cells were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of recipients. CD4+ T-cell response to Ld 61–80 peptide was assessed by ELISPOT. As shown in Fig. 2A, BALB/c skin transplantation induced a vigorous inflammatory type 1 alloresponse to Ld 61–80 peptide. In this setting, CD4+ T cells were activated by recipient dm2 APC and the Ld 61–80 allopeptide, i.e. through the indirect allorecognition pathway. The response to Ld 61–80 represented approximately 60% of the overall indirect alloresponse as recorded with donor BALB/c sonicates (Fig. 2A). Some direct CD4+ T-cell response was detected, a result presumably reflecting the previously reported presentation of endogenously processed Ld 61–80 by MHC class II Ad molecules on BALB/c APC [33]. A potent CD4+ T-cell direct response was found in dm2 mice transplanted with fully mismatched B6 skins (Fig. 2B). Finally, a low but significant CD8+ T-cell-mediated CTL response to BALB/c targets could be recorded in dm2 mice engrafted with BALB/c skins (Fig. 2C). This CTL response was responsible for acute skin graft rejection given that in vivo treatment of recipients with anti-CD8 mAb prevented rejection (data not shown). These results show that in dm2 mice, the CD4+ T-cell alloresponse directed to the dominant Ld 61–80 allopeptide is sufficient to induce a CTL direct response by CD8+ T cells and the subsequent acute rejection of BALB/c skins (depicted in Fig. 3).

Figure 2.

T-cell response of dm2 mice transplanted with a BALB/c skin. dm2 mice (Ld−) were transplanted with a skin from single MHC class I-mismatched BALB/c donors (Ld+). At the time of rejection (10–12 days post-transplantation), CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were isolated from recipients’ spleens and tested for their alloreactivity. (A) CD4+ T cells were tested by ELISPOT for their indirect alloresponse to BALB/c donor. T cells were incubated with recipient APC along with donor sonicates or the dominant donor allopeptide Ld 61–80. T cells cultured with medium alone or control B6 sonicates and irrelevant peptide HEL 46–61 were used as controls. The results are presented as spots per million T cells ± SD for each cytokine. Data are representative of two experiments each including 3–5 mice tested individually. The number of spots obtained with non-transplanted mice ranged from 5–15 spots/million T cells. (B) CD4+ T cells were tested by ELISPOT for their direct alloresponse (MLR) to BALB/c donor. T cells were incubated with donor irradiated MHC class I-mismatched BALB/c APC (solid bars) or fully mismatched B6 APC (hatched bars) or medium (white bars). The results are presented as spots per million T cells ± SD for each cytokine. Data are representative of five experiments each including 2–3 mice tested individually. (C) Cytotoxic response of CD8+ T cells from transplanted dm2 mice against donor BALB/c targets (solid dots). Syngeneic targets (triangles) and third-party B6 targets (squares) were used as controls. The spontaneous release ranged from 10 to 15% of maximal release. The data shown here are representative of two independent experiments including three mice tested individually. The percentages of cytotoxicity recorded with T cells from non-transplanted mice ranged from 2 to 8%.

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the alloresponse in dm2 mice transplanted with BALB/c skin. Donor MHC class I, including Ld 61–80 peptide, are processed and presented in an MHC class II context by recipient APC (exogenous processing, indirect pathway) or donor APC (endogenous processing, direct pathway) to CD4+ T cells. Activated donor-specific CD4+ T cells produce IL-2 thus promoting the differentiation of cytotoxic CD8+ T cells recognizing donor MHC class I at the surface of donor cells (direct allorecognition).

Influence of immunization of dm2 mice with Ld 61–80 peptide on the rejection of BALB/c skin grafts

To induce a type 1 cytokine inflammatory indirect alloresponse, dm2 mice were injected i.p. with Ld 61–80 peptide emulsified in CFA (i.p.-CFA). Ten days later, these mice were engrafted with BALB/c skins and tested for their alloresponse and graft rejection. As shown in Fig. 4A, Ld peptide immunization in CFA was associated with a significant increase in anti-donor CTL response as compared with unprimed mice (Fig. 3A) and an accelerated rejection of BALB/c skin allografts (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of Ld 61–80 immunization in CFA on allocytotoxicity and skin graft rejection. dm2 mice were immunized subcutaneously with Ld 61–80 MHC class I peptide emulsified in CFA. Ten days later, these mice received a skin graft from a BALB/c donor. (A) Cytotoxic response of CD8+ T cells against donor BALB/c targets (solid circles). Syngeneic targets (triangles) and third-party B6 targets (squares) were used as controls. Spontaneous release ranged from 10 to 15% of maximal release. The percentages of cytotoxicity recorded with T cells from non-transplanted mice ranged from 5 to 10%. (B) Survival of BALB/c skin grafts in Ld 61–80-CFA-immunized dm2 mice (solid line) and control non-immunized mice (dotted line). Data are representative of three independent experiments each including four mice tested individually. The Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance between two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used to assess statistical significance between the scores. Graft survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

In another set of experiments, dm2 mice were administered i.p. with Ld 61–80 peptide emulsified in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (i.p.-IFA), a procedure known to polarize T-cell response toward type 2 cytokine (Th2: IL-4, IL-5, IL-10) immunity [36–38]. Ten days after immunization, these mice received a BALB/c skin graft and were tested for their alloresponse (ELISPOT), CTL response against BALB/c targets and rejection. Such i.p.-IFA peptide administration resulted in a marked increase in the Th2 response and a reduction of the Th1 response (Table 1). In addition, these mice failed to mount a CTL response to BALB/c allotarget cells (Fig. 5A). Most importantly, rejection of skin allografts was delayed to 60–80 days in all treated mice (Fig. 5B). Control mice injected with PBS or an irrelevant peptide in IFA rejected skin grafts in 10–14 days. Finally, some dm2 mice were treated with anti-IL-4 Ab (mAb: 11B11, 2 mg given i.p.) 1 day before i.p.-IFA Ld 61–80 peptide administration. These mice rejected BALB/c skin grafts like control mice (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these results show that pre-transplantation sensitization of indirect Th1 alloresponse results in accelerated acute rejection of skin transplants correlating with an increase in CTL alloreactivity. In contrast, activation of Ld 61–80 allospecific Th2 cells prior to placement of skin allografts significantly prolonged transplant survival, a phenomenon associated with a reduced inflammatory Th1 alloresponse and the abrogation of the anti-donor cytotoxic T-cell activity.

Table 1.

Adjuvant-driven T-cell responses of Ld 61–80 peptide in dm2 mice

| Immunization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| none | Ld 61–80 CFA | Ld 61–80 IFA | Ld 61–80 soluble | |

| IL-2 | 8 | 188 | 12 | 15 |

| gIFN | 5 | 224 | 8 | 12 |

| IL-4 | 2 | 5 | 162 | 3 |

| IL-5 | 2 | 2 | 98 | 4 |

dm2 mice were immunized subcutaneously with Ld 61–80 MHC class I allopeptide given with CFA, IFA or without adjuvant. Ten days later, CD4+ T cells were isolated from draining lymph nodes and cultured in vitro for 40 h with Ld 61–80 peptide. The frequencies of CD4+ T cells producing type 1 cytokines (IL-2 and IFN-γ) and type 2 cytokines (IL-4 and IL-5) were measured by ELISPOT. The results represent the number of spots per million CD4+ T cells. Bold underlined numbers represent values that are significantly higher than the background (p<0.001). The number of spots obtained with T cells from non-immunized mice and mice immunized with HEL 46–61 control peptide ranged from 0 to 4 spots per million T cells. The number of spots obtained with T cells from Ld 61–80 peptide-immunized mice cultured in the absence of peptide ranged from 2 to 5 spots per million T cells. The results are representative of three experiments performed on 2–4 mice tested individually.

Figure 5.

Effects of Ld 61–80 immunization in IFA on allocytotoxicity and skin graft rejection. dm2 mice were immunized i.p. with Ld 61–80 MHC class I peptide emulsified in IFA. Ten days later, these mice received a skin graft from a BALB/c donor. (A) Cytotoxic response of CD8+ T cells against donor BALB/c targets (solid circles). Syngeneic targets (triangles) and third-party B6 targets (squares) were used as controls. Spontaneous release ranged from 10 to 15% of maximal release. The percentages of cytotoxicity recorded with T cells from non-transplanted mice ranged from 3 to 7%. (B) Survival of BALB/c skin grafts in Ld 61–80-CFA-immunized dm2 mice (black, solid and dotted lines) and control non-immunized mice (grey doted line). Data are representative of three independent experiments each including three mice tested individually. The Student’s t-test was used to assess statistical significance between two groups, and one-way ANOVA was used to assess statistical significance between the scores. Graft survival was analyzed using the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival curves were compared using the log-rank test.

Effects of Th1 and Th2 indirect alloresponses on heart transplant rejection

Cardiac allotransplants are less immunogenic than their skin counterparts. Actually, in certain MHC class I-mismatched mouse donor/recipient combinations, cardiac allografts enjoy long-term survival while skin grafts are acutely rejected. In our model, dm2 mice did not acutely reject BALB/c hearts. Moreover, histological examination of transplanted hearts revealed no signs of chronic rejection in the majority of mice tested even 100 days after heart transplantation (Fig. 6A and B). Two mice out of ten with transplanted hearts exhibited mild interstitial infiltration and fibrosis detectable 120 days post-transplantation (Table 2).

Figure 6.

Histopathology of BALB/c heart transplants from dm2 mice sensitized with Ld 61–80 peptide emulsified in IFA. dm2 mice were immunized i.p. with Ld 61–80 MHC class I peptide emulsified in IFA. Ten days later, these mice received a heart transplant from a BALB/c donor. (A, B) Histology of BALB/c heart transplants from control unimmunized dm2 mice. (C, D) Photomicrographs (40×) of allogeneic hearts harvested 50 and 100days post-transplantation from a Ld 61–80-sensitized recipient mouse display a lymphocytic inflammatory cell infiltrate and vessel obstruction. Data are representative of eight mice tested individually.

Table 2.

Chronic rejection scores of BALB/c heart transplants in dm2 mice immunized with Ld 61–80

| Immunization | Graft survival (days) | Vessel occlusion (%) | Fibrosis (1–5) | Interstitial inflammation (1–5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | >100 | 5±0.5 | 0 | 1±0.3 |

| IFA | >100 | 4±0.6 | 1±0.2 | 0 |

| HEL 46–61-IFA | >100 | 7±1.7 | 1±0.3 | 1±0.2 |

| Ld 61–80 IFA | 52±10 | 85±10 | 4±0.5 | 4±0.7 |

dm2 mice were immunized i.p. with Ld 61–80 alloMHC class I peptide emulsified in IFA. Ten days later, these mice were transplanted with a BALB/c heart. One hundred days later, heart transplants were collected and examined for chronic rejection using histological techniques. The vascular cross-sections were graded using morphometric scale (0–5) of luminal occlusion. In this scale 0 represents a normal vessel, whereas a score of 5 indicates more than 80% occlusion of the lumen. Second, from this scale, we determined the percentage of vessels elaborating disease (i.e. morphometric score >0). Non-immunized mice as well as mice injected with control HEL peptide 46–61 administered in IFA or with IFA alone were used as controls. The results represent mean values ± SD obtained from 5–8 mice tested in each group.

Next, we investigated whether immunization of dm2 mice with the peptide Ld 61–80 would influence their ability to reject BALB/c hearts. First, dm2 mice were injected i.p. with the Ld 61–80 peptide in CFA 10 days prior to heart transplantation. While this procedure induced a Th1-mediated alloresponse (Table 1), it did not cause acute rejection of BALB/c hearts and had no influence on the course of chronic rejection (data not shown). In contrast, dm2 mice which received the Ld 61–80 peptide i.p.-IFA and mounted a Th2 indirect alloresponse (Table 1) displayed severe signs of chronic allograft vasulopathy detectable as early as 50 days after cardiac transplantation (Table 2 and Fig. 6, right panels). No effects were observed with control HEL peptides administered i.p.-IFA (Table 2). Also, no signs of chronic rejection of syngeneic heart transplants were observed in dm2 mice treated with Ld 61–80 peptide given i.p.-IFA (data not shown). Therefore, in this model, activation of Th2 but not Th1 indirect alloreactivity induces chronic rejection of cardiac allotransplants.

Discussion

The vigorous polyclonal direct alloresponse by inflammatory CD4+ T cells recognizing alloMHC class II molecules on donor passenger leukocytes represents the driving force behind acute rejection of fully allogeneic allotransplants [39–41]. However, in the absence of MHC class II mismatch and direct CD4+ T-cell allorecognition, the CD4+ T-cell indirect alloresponse is sufficient to ensure acute rejection of MHC class I-disparate skin allografts [42, 43]. Indeed, indirect allorecognition is known to induce DTH, promote CTL activity by CD8+ T cells and trigger the production of anti-donor Ab by B cells [8, 19, 21, 44]. Most importantly, this type of alloreactivity is oligoclonal in that it involves a limited set of T cells specific for a few dominant donor determinants [6, 7, 45]. This suggests that Ag-based tolerization may be designed to tolerize this pathway of allosensitization. In this study, we tested this possibility using the single MHC class I-disparate combination dm2 (Ld)-BALB/c (Ld+) in which the majority of CD4+ T cells recognize a dominant determinant, Ld 61–80. We observed that induction of a Th2 response to the dominant peptide Ld 61–80 significantly delayed the rejection of BALB/c (Ld+) skin allografts by dm2 (Ld) mice. This effect was associated with the abrogation of both Th1 inflammatory responses and CTL responses. In our model, third party skin grafts were rejected in 10 days, thereby supporting a model of donor Ag-specific suppression compatible with the activation of Th2 T cells. Matesic et al. have previously reported that adoptive transfer of IL-4/IL-5-producing CD4+ T cells, but not CD8+ T cells, can cause alloskin graft rejection associated with an eosinophilic infiltration of the skin [46]. Together with our results, this indicates that Th2 cells activated indirectly can prevent acute rejection of skin grafts but induce delayed rejection of these transplants via a non-inflammatory process. In our model, no eosinophils were detected in skin allografts rejected by Th2 cells. We surmise that Th2 cells could ensure the rejection of skin allografts by promoting the production of anti-donor Ab.

Unlike their skin counterparts, BALB/c heart transplants are not acutely rejected by dm2 mice. This presumably reflects the weakness of the CD4+ T-cell indirect alloresponse induced by heart transplants. In support of this, we have previously shown that the magnitude of indirect CD4+ T-cell alloreactivity is low after cardiac transplantation as compared with skin and corneal transplants [47]. In the absence of direct alloreactivity, a low indirect alloresponse is likely to result in the lack of differentiation of functional CTL, a phenomenon we previously documented in the case of corneal allotransplants [48]. The poor ability of cardiac transplants to induce an indirect alloresponse is not an intrinsic property of these organs as we recorded vigorous CD4+ indirect alloresponses when the heart was placed under the skin (Gilles Benichou, unpublished data). It is possible that upon immediate vascularization of the transplant, as in classical cardiac transplantation, donor APC migrate to the host’s thymus and spleen rather than lymph nodes. This could contribute to the poor immunogenicity of heart and kidney transplants as compared to skin grafts. In addition, the skin contains large numbers of highly immunogenic dendritic cells including Langerhans cells, a feature which presumably accounts for their ability to trigger potent alloimmune reponses. It is noteworthy that not all single MHC class I-disparate vascularized heart transplants escape acute rejection in mice. For instance, A/J mice reject acutely A.TL hearts that differ by a single MHC class I allele (Kk versus Ks) [15]. The presence of Th-independent CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in certain mouse strains may account for this heterogeneity [49].

Induction of a Th2 indirect alloresponse to the Ld 61–80 allopeptide induced rapid and severe chronic allograft vasculopathy in dm2 recipients of a BALB/c heart. This finding extends previous studies showing some correlation between chronic rejection and the presence of activated T cells directed to donor HLA peptides in transplant recipients [27–31]. Until now, the most convincing evidence of the potential role of indirect allorecognition in chronic allograft rejection has been provided by J. Madsen’s group, which reported that injection of donor MHC class I peptides could accelerate the course of chronic allograft vasculopathy in heart-transplanted miniature swine [32]. To our knowledge, the present study demonstrates for the first time that induction of an indirect CD4+ T-cell alloresponse can induce de novo chronic rejection of an allotransplant.

In our model, the Th2 but not Th1 indirect alloresponse induces de novo chronic allograft vasculopathy in heart transplants. This is in agreement with previous studies suggesting the involvement of Th2 cells in cardiac allograft rejection and vasculopathy [31, 50–52]. Th2 cells activated via indirect allorecognition are likely to mediate their effect on chronic rejection by stimulating the production of Ab displaying non-complement fixing IgG1 isotype [37, 53]. Chronic rejection may also result from the activation of autoreactive T cells directed to cardiac tissue Ag including myosin and vimentin Ag, which are known to contribute to cardiac allograft rejection [15, 54–56]. It is at first glance surprising that the indirect Th1 alloresponse to the peptide Ld 61–80 activated some cytotoxic T cells while it failed to mediate the acute rejection of cardiac transplants in this model. We surmise that given the low frequency of this response directed to a single peptide, it does not reach the threshold that is necessary to achieve acute graft rejection.

This study shows that the fate of MHC class I-disparate transplants depends upon the type of the tissue grafted and the nature of indirect CD4+ T cell alloresponse. In our model, skin allografts elicit an immediate and potent inflammatory indirect alloresponse that eventuates in acute rejection. Alternatively, induction of an antagonist Th2 indirect response delays graft rejection presumably by suppressing the CD8+ direct cytolytic response. In contrast, transplantation of a vascularized heart induces a poor Th1 indirect alloresponse and fails to achieve acute rejection. In this setting, induction of a Th2 but not a Th1 indirect alloresponse resulted in de novo development of chronic rejection. This suggests that although immune deviation of indirect alloreactivity to Th2 type of response could be used to prevent acute allograft rejection, it may induce or exacerbate the chronic rejection of vascularized solid organ transplants.

Materials and Methods

Mouse skin and heart transplantations

Mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). The care of animals was in accordance with institutional guidelines. Vascularized heterotopic cardiac transplantation was performed as described by Corry et al. [57]. Transplanted hearts were monitored daily by palpation through the abdominal wall. Heart beat intensity was graded on a scale of 0 (no palpable impulse) to 4 (strong impulse). Rejection was defined by the loss of palpable cardiac contractions and verified by autopsy and pathological examination. Skin allografts were performed according to the technique previously described by Billingham and Medawar [58].

T-cell and T-cell subsets isolation

T cells as well as CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell subsets were isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes of transplanted and naive mice by negative selection using commercially available T-cell purification columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Accurate Chemical & Scientific, Westbury, NY, USA) (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Purified T cells were washed in HBSS and used in ELISPOT assays.

Preparation of APC

Mitomycin C-treated splenocytes from donor and recipient naive mice were used as allogeneic stimulator cells or syngeneic APC, respectively. Single cell suspensions of splenocytes devoid of RBC were prepared in AIM-V medium containing 0.5% FBS and treated with mitomycin C (50 μg/mL) for 30 min at 37°C. The cells were washed once in HBSS, incubated for 10 min at 37°C and washed once again before resuspension in AIM-V, 0.5% FBS at 1–3 × 107 cells/mL.

Preparation of sonicates

Spleen cells were suspended at 3 × 107 cells/mL in AIM-V medium containing 0.5% FBS and sonicated with 10 pulses per 1 s each. The resulting suspension was frozen in a dry ice/ethanol bath, thawed at room temperature and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min to remove intact cells.

Anti-IL-4 mAb treatments

For anti-IL-4 mAb treatments, mice were given a single i.p. injection of 2 mg of rat mAb specific for mouse IL-4 cytokine (clone 11B11). Ab were purified from tissue culture supernatants using a protein G column. The hybridoma 11B11 was obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD, USA).

Measurement of direct and indirect alloimmune T-cell responses

Spleen and lymph node T cells from naive and skin- or heart-transplanted mice were used as a source of responder cells to measure the total alloresponse as well as the direct and indirect responses. RBC were lyzed for 2 min in Tris-NH4Cl solution. T cells were then washed twice in AIM-V (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, NY, USA) medium containing 0.5% FBS and resuspended at 107 cells/mL with 0.5% FBS in AIM-V for use.

ELISPOT assays were performed as described elsewhere [39]. Briefly, ELISPOT plates (Polyfiltronics, Rockland, MA, USA) were coated with either 3 μg/mL of rat anti-mouse IL-2 (JES6-1A12) or 4 μg/mL of rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (R4-6A2) or 2 μg/mL of rat anti-mouse IL-4 (11B11) capturing mAbs. The plates were then blocked for 1.5 h with PBS containing 1% BSA and washed with sterile PBS. To measure the direct alloresponse, 0.3 × 106 T cells from transplanted or naive mice were cultured with 106 irradiated (2000 Rad) syngeneic or allogeneic splenocytes. To measure indirect responses, T cells from recipients were incubated with sonicates as previously described [39]. The frequency of T cells producing IL-2, IFN-γ and IL-4 was determined 24 h later. After removal of cells from the plates and washing, 2 μg/mL of biotin-ylated rat anti-mouse IL-2 mAb (JES6-5H4), rat anti-mouse IFN-γ mAb (XMG 1.2) or rat anti-mouse IL-4 mAb (BVD6-24G2) were used followed by incubation with streptavidin D horseradish peroxidase (Vector, Burlingame, CA, USA) diluted at 1:2000 in PBS/0.025% Tween. All mAbs were obtained from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, USA). After washing, the plates were developed using 0.8 mL of 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA; 10 μg dissolved in 1 mL dimethyl formamide) mixed with 24 mL of 0.1 M sodium acetate, pH 5.0, containing 12 mL H202. The resulting spots were counted using a computer-assisted enzyme-linked immunospot image analyzer (T Spot Image Analyzer, Cellular Technology, Cleveland, OH, USA).

Cytotoxic T-cell assays

Spleen T cells derived from BALB/c recipient mice were harvested 9–11 days after transplantation and tested for their ability to lyse peritoneal exudate cells from either donors (B6), syngeneic (BALB/c) or third party (CBA) origins as described elsewhere [35].

Morphology

Cardiac transplants were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, coronally sectioned and stained with H&E for evaluation of cellular infiltrates and myocyte damage (acute rejection) by light microscopy. For assessment of chronic rejection, cardiac grafts were stained with Verhoeff’s elastin (vessel arteriosclerosis scoring) or Mason’s trichrome (evaluation of fibrosis). Arteriosclerosis was assessed by light microscopy and the percentage of luminal occlusion and intimal thickening was determined using a scoring system as previously described [59]. Only vessels that display a clear internal elastic lamina were included in morphometric analysis (5–7 vessels per section). All arteries were scored by at least two examiners in a blinded fashion.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using STATView software (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA, USA). p-values were calculated using paired t-test. p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ms. Karla Stenger, Colleen Doherty and Sarah Connolly for their assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Drs. G. Tocco, A. Alessandrini and H. Winn for helpful discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (KO2AI53103 and R01 HD050484) to G. B.

Abbreviations

- HEL

hen eggwhite lysozyme

- IFA

incomplete Freund’s adjuvant

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Krensky AM. T cells in autoimmunity and allograft rejection. Kidney Int Suppl. 1994;44:S50–S56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lombardi G, Lechler R. The molecular basis of allorecognition of major histocompatibility complex molecules by T lymphocytes. Ann Ist Super Sanita. 1991;27:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benichou G, Takizawa PA, Olson CA, McMillan M, Sercarz EE. Donor major histocompatibility complex (MHC) peptides are presented by recipient MHC molecules during graft rejection. J Exp Med. 1992;175:305–308. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fangmann J, Dalchau R, Fabre JW. Rejection of skin allografts by indirect allorecognition of donor class I major histocompatibility complex peptides. Transplant Proc. 1993;25:183–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Z, Colovai AI, Tugulea S, Reed EF, Fisher PE, Mancini D, Rose EA, et al. Indirect recognition of donor HLA-DR peptides in organ allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1150–1157. doi: 10.1172/JCI118898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benichou G, Fedoseyeva E, Lehmann PV, Olson CA, Geysen HM, McMillan M, Sercarz EE. Limited T cell response to donor MHC peptides during allograft rejection. Implications for selective immune therapy in transplantation. J Immunol. 1994;153:938–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Z, Colovai AI, Tugulea S, Reed EF, Harris PE, Maffei A, Molajoni ER, et al. Mapping of dominant HLA-DR determinants recognized via the indirect pathway. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:1014–1015. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00348-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee RS, Grusby MJ, Glimcher LH, Winn HJ, Auchincloss H., Jr Indirect recognition by helper cells can induce donor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1994;179:865–872. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee RS, Grusby MJ, Laufer TM, Colvin R, Glimcher LH, Auchincloss H., Jr CD8+ effector cells responding to residual class I antigens, with help from CD4+ cells stimulated indirectly, cause rejection of “major histocompatibility complex-deficient” skin grafts. Transplantation. 1997;63:1123–1133. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704270-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayry P, Isoniemi H, Yilmaz S, Mennander A, Lemstrom K, Raisanen-Sokolowski A, Koskinen P, et al. Chronic allograft rejection. Immunol Rev. 1993;134:33–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1993.tb00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hosenpud JD, Mauck KA, Hogan KB. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: IgM antibody responses to donor-specific vascular endothelium. Transplantation. 1997;63:1602–1606. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199706150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell PS, Chase CM, Colvin RB. Alloantibody- and T cell-mediated immunity in the pathogenesis of transplant arteriosclerosis: lack of progression to sclerotic lesions in B cell-deficient mice. Transplantation. 1997;64:1531–1536. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199712150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benichou G, Malloy KM, Tam RC, Heeger PS, Fedoseyeva EV. The presentation of self and allogeneic MHC peptides to T lymphocytes. Hum Immunol. 1998;59:540–548. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(98)00059-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fedoseyeva EV, Kishimoto K, Rolls HK, Illigens BM, Dong VM, Valujskikh A, Heeger PS, et al. Modulation of tissue-specific immune response to cardiac myosin can prolong survival of allogeneic heart transplants. J Immunol. 2002;169:1168–1174. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fedoseyeva EV, Zhang F, Orr PL, Levin D, Buncke HJ, Benichou G. De novo autoimmunity to cardiac myosin after heart transplantation and its contribution to the rejection process. J Immunol. 1999;162:6836–6842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suciu-Foca N, Ciubotariu R, Colovai A, Foca-Rodi A, Ho E, Rose E, Cortesini R. Persistent allopeptide reactivity and epitope spreading in chronic rejection. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:100–101. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suciu-Foca N, Harris PE, Cortesini R. Intramolecular and intermolecular spreading during the course of organ allograft rejection. Immunol Rev. 1998;164:241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1998.tb01224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilkes DS. The role of autoimmunity in the pathogenesis of lung allograft rejection. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2003;51:227–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suciu-Foca N, Liu Z, Harris PE, Reed EF, Cohen DJ, Benstein JA, Benvenisty AI, et al. Indirect recognition of native HLA alloantigens and B-cell help. Transplant Proc. 1995;27:455–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Auchincloss H, Jr, Sultan H. Antigen processing and presentation in transplantation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:681–687. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steele DJ, Laufer TM, Smiley ST, Ando Y, Grusby MJ, Glimcher LH, Auchincloss H., Jr Two levels of help for B cell alloantibody production. J Exp Med. 1996;183:699–703. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.2.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vongwiwatana A, Tasanarong A, Hidalgo LG, Halloran PF. The role of B cells and alloantibody in the host response to human organ allografts. Immunol Rev. 2003;196:197–218. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-065x.2003.00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soleimani B, Lechler RI, Hornick PI, George AJ. Role of alloantibodies in the pathogenesis of graft arteriosclerosis in cardiac transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1781–1785. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuo E, Maruyama T, Fernandez F, Mohanakumar T. Molecular mechanisms of chronic rejection following transplantation. Immunol Res. 2005;32:179–185. doi: 10.1385/IR:32:1-3:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin YP, Jindra PT, Gong KW, Lepin EJ, Reed EF. Anti-HLA class I antibodies activate endothelial cells and promote chronic rejection. Transplantation. 2005;79:S19–S21. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000153293.39132.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Colvin RB. Antibody-mediated renal allograft rejection: diagnosis and pathogenesis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1046–1056. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suciu-Foca N, Ciubotariu R, Itescu S, Rose EA, Cortesini R. Indirect allorecognition of donor HLA-DR peptides in chronic rejection of heart allografts. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:3999–4000. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)01318-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suciu-Foca N, Ciubotariu R, Liu Z, Ho E, Rose EA, Cortesini R. Persistent allopeptide reactivity and epitope spreading in chronic rejection. Transplant Proc. 1998;30:2136–2137. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)00564-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reznik SI, Jaramillo A, SivaSai KS, Womer KL, Sayegh MH, Trulock EP, Patterson GA, Mohanakumar T. Indirect allorecognition of mismatched donor HLA class II peptides in lung transplant recipients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Am J Transplant. 2001;1:228–235. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2001.001003228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poggio ED, Clemente M, Riley J, Roddy M, Greenspan NS, Dejelo C, Najafian N, et al. Alloreactivity in renal transplant recipients with and without chronic allograft nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1952–1960. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000129980.83334.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shirwan H. Chronic allograft rejection. Do the Th2 cells preferentially induced by indirect alloantigen recognition play a dominant role? Transplantation. 1999;68:715–726. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199909270-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee RS, Yamada K, Houser SL, Womer KL, Maloney ME, Rose HS, Sayegh MH, Madsen JC. Indirect recognition of allopeptides promotes the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3276–3281. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051584498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fedoseyeva EV, Tam RC, Orr PL, Garovoy MR, Benichou G. Presentation of a self-peptide for in vivo tolerance induction of CD4+ T cells is governed by a processing factor that maps to the class II region of the major histocompatibility complex locus. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1481–1491. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.5.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Soares LR, Orr PL, Garovoy MR, Benichou G. Differential activation of T cells by natural antigen peptide analogues: influence on autoimmune and alloimmune in vivo T cell responses. J Immunol. 1998;160:4768–4775. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Popov IA, Fedoseyeva EV, Orr PL, Garovoy MR, Benichou G. Direct evidence for in vivo induction of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells directed to donor MHC class I peptides following mouse allotransplantation. Transplantation. 1995;60:1621–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forsthuber T, Yip HC, Lehmann PV. Induction of TH1 and TH2 immunity in neonatal mice. Science. 1996;271:1728–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yip HC, Karulin AY, Tary-Lehmann M, Hesse MD, Radeke H, Heeger PS, Trezza RP, et al. Adjuvant-guided type-1 and type-2 immunity: infectious/noninfectious dichotomy defines the class of response. J Immunol. 1999;162:3942–3949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karulin AY, Hesse MD, Tary-Lehmann M, Lehmann PV. Single-cytokine-producing CD4 memory cells predominate in type 1 and type 2 immunity. J Immunol. 2000;164:1862–1872. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benichou G, Valujskikh A, Heeger PS. Contributions of direct and indirect T cell alloreactivity during allograft rejection in mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:352–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenberg AS, Singer A. Cellular basis of skin allograft rejection: an in vivo model of immune-mediated tissue destruction. Annu Rev Immunol. 1992;10:333–358. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.10.040192.002001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sayegh MH. Why do we reject a graft? Role of indirect allorecognition in graft rejection. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1967–1979. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Auchincloss H, Jr, Lee R, Shea S, Markowitz JS, Grusby MJ, Glimcher LH. The role of “indirect” recognition in initiating rejection of skin grafts from major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:3373–3377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Illigens BM, Yamada A, Fedoseyeva EV, Anosova N, Boisgerault F, Valujskikh A, Heeger PS, et al. The relative contribution of direct and indirect antigen recognition pathways to the alloresponse and graft rejection depends upon the nature of the transplant. Hum Immunol. 2002;63:912–925. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Waaga AM, Murphy B, Chen W, Khoury SJ, Sayegh MH. Class II MHC allopeptide-specific T-cell clones transfer delayed type hypersensitivity responses in vivo. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:1008–1009. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00345-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Z, Sun YK, Xi XYP, Hong B, Harris PE, Reed EF, Suciu-Foca N. Limited usage of T cell receptor V beta genes by allopeptide-specific T cells. J Immunol. 1993;150:3180–3186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matesic D, Valujskikh A, Pearlman E, Higgins AW, Gilliam AC, Heeger PS. Type 2 immune deviation has differential effects on alloreactive CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:5236–5244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boisgerault F, Anosova NG, Tam RC, Illigens BM, Fedoseyeva EV, Benichou G. Induction of T-cell response to cryptic MHC determinants during allograft rejection. Hum Immunol. 2000;61:1352–1362. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(00)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Boisgerault F, Liu Y, Anosova N, Ehrlich E, Dana MR, Benichou G. Role of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in allorecognition: lessons from corneal transplantation. J Immunol. 2001;167:1891–1899. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Williams MA, Trambley J, Ha J, Adams AB, Durham MM, Rees P, Cowan SR, et al. Genetic characterization of strain differences in the ability to mediate CD40/CD28-independent rejection of skin allografts. J Immunol. 2000;165:6849–6857. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.12.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Csencsits K, Wood SC, Lu G, Magee JC, Eichwald EJ, Chang CH, Bishop DK. Graft rejection mediated by CD4+ T cells via indirect recognition of alloantigen is associated with a dominant Th2 response. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:843–851. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Koksoy S, Kakoulidis TP, Shirwan H. Chronic heart allograft rejection in rats demonstrates a dynamic interplay between IFN-gamma and IL-10 producing T cells. Transplant Immunol. 2004;13:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mhoyan A, Wu GD, Kakoulidis TP, Que X, Yolcu ES, Cramer DV, Shirwan H. Predominant expression of the Th2 response in chronic cardiac allograft rejection. Transplant Int. 2003;16:464–473. doi: 10.1007/s00147-003-0590-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Heeger PS, Forsthuber T, Shive C, Biekert E, Genain C, Hofstetter HH, Karulin A, Lehmann PV. Revisiting tolerance induced by autoantigen in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant. J Immunol. 2000;164:5771–5781. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rolls HK, Kishimoto K, Illigens BM, Dong V, Sayegh MH, Benichou G, Fedoseyeva EV. Detection of cardiac myosin-specific autoimmunity in a model of chronic heart allograft rejection. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:3821–3822. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(01)02617-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jurcevic S, Ainsworth ME, Pomerance A, Smith JD, Robinson DR, Dunn MJ, Yacoub MH, Rose ML. Antivimentin antibodies are an independent predictor of transplant- associated coronary artery disease after cardiac transplantation. Transplantation. 2001;71:886–892. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200104150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Azimzadeh AM, Pfeiffer S, Wu GS, Schroder C, Zhou H, Zorn GL, III, Kehry M, et al. Humoral immunity to vimentin is associated with cardiac allograft injury in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2005;5:2349–2359. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Corry RJ, Winn HJ, Russell PS. Primarily vascularized allografts of hearts in mice. The role of H-2D, H-2K, and non-H-2 antigens in rejection. Transplantation. 1973;16:343–350. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Billingham RE, Medawar PD. The technique of free skin grafting in mammals. J Exp Biol. 1951;28:385. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Russell ME, Hancock WW, Akalin E, Wallace AF, Glysing-Jensen T, Willett TA, Sayegh MH. Chronic cardiac rejection in the LEW to F344 rat model. Blockade of CD28-B7 costimulation by CTLA4Ig modulates T cell and macrophage activation and attenuates arteriosclerosis. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:833–838. doi: 10.1172/JCI118483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]