Abstract

The changing demographics in the country require new strategies for providing culturally competent care. The Northern California Region Member Patient Survey provides detailed information for the clinician when the data is segmented into subsets by age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Any gaps identified allow for the clinician to focus on key areas for improvement in an efficient manner respecting the time constraints of a busy practice.

Introduction

The Context

The intent of this article is to tell a story, to share a method so others can emulate it, to present data, and to guide further study, all to improve care, service, and satisfaction. The incentives for physicians to improve their service scores may include: 1) to attain partnership in the medical group, 2) increased compensation in salary or incentive payments, and 3) higher professional satisfaction. Organizational incentives include higher patient retention rates and lower physician turnover rates. It has been well documented within Kaiser Permanente (KP), by Kristen Gregory, PhD, Director of Patient Satisfaction Assessment for The Permanente Medical Group (TPMG) in charge of the member patient survey Member Patient Satisfaction (MPS) survey, that higher satisfaction scores correlate with patient retention.

A young Asian woman physician from China is labeled as a low performer because of her service scores and ultimately transfers to a different facility. In the Internal Medicine Department, a man, age 20 years, is told by his physician that his fatigue is from partying too much; after a car accident, the patient is diagnosed with leukemia. A Spanish-speaking woman travels to Mexico to be treated because without adequate interpretation services available to explain her condition, she lacks trust.

Complex Demographic Picture

The demographic picture in California is changing, creating a complex demographic challenge for the physician, for the facility, and for the organization.1 The impact is felt in service, brand image, membership growth, and physician satisfaction. A strategy to deal with the changing landscape requires a new approach to the evaluation of demographic data. The following service improvement program combines patient satisfaction “service scores,” data segmentation, and data analysis. It has demonstrated successful outcomes dealing with increasing complexity of demographic change in our facility. It has also shown that addressing ethnicity issues alone is not sufficient to provide culturally competent care; other factors such as gender and age are critical for understanding the service needs of patients. It has also demonstrated that the interaction between clinician and patient is extremely complex and both may have biases that have to be identified. Bias can be either positive or negative but the area of bias tends to be ignored as it is seen as a negative attribute by the clinician. The use of data segmentation and analytics offers recognition for clinicians in the demographic subsets at which they excel. It identifies areas of opportunity for the clinician to improve, which usually was not identified until pointed out by the data. Once the area of opportunity is identified, appropriate resources can be applied to assist the clinician. The work is strategic in that the clinician only focuses on the demographic gaps and not his/her entire schedule. This is critical given the time constraints and busy schedules of physicians and of clinicians.

Multiplural Population

Southern Alameda County in northern California (NC) has a multiplural population—no population segment over 50%—and has unique populations including a large Afghan population2 and a large population of hearing-impaired patients. Asians are the fastest-growing group in Fremont and are underrepresented as KP members (Pierre Adler, personal communication, 2009).a Latinos and other smaller demographic groups are also growing. Small companies with nonwhite and women ownership are rapidly growing in number.a The KP Northern California (KPNC) staff, both physician and nonphysician, is increasingly diverse, reflecting changes in the surrounding communities and requiring new strategies for service improvement and professional satisfaction.

Demographic Shifts

It is critical to understand that there may be demographic variation even within the same facility. Variation occurs by individual clinician and at the department level. In Hayward, for example, the percentage of Asian patients seen in Internal Medicine was 24% whereas the percentage of Asian patients seen in psychiatry was only 8%. The reluctance to be seen in the Psychiatry Department was discussed in a Filipino focus group when talking about postpartum depression. There was a fear expressed by the participants that family members or friends might find out that they had been seen in psychiatry.

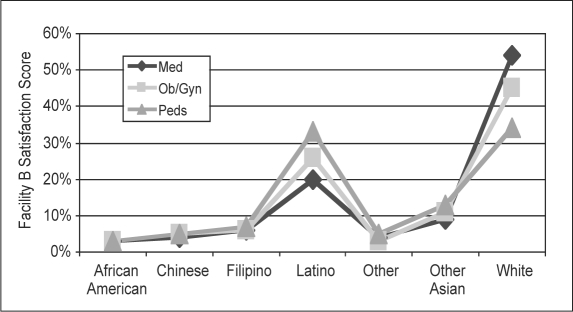

Figure 1 shows variation by Primary Care Departments in a KPNC facility. The graph shows that whites are the predominant group seen in Internal Medicine; whereas Latinos have the same percentage of survey returns as whites in the Pediatric Department. Ob/Gyn, which has a blend of younger and older patients, was in the middle. This same pattern is seen in other facilities with heterogeneous populations, although the pattern in pediatrics may be shifting from predominantly Latino to Asian. These changing dynamics have implications such as in hiring physicians and staff for the various departments even within the same facility.

Figure 1.

Member Patient Satisfaction survey scores in internal medicine, gynecology, and pediatrics. Sorted by race/ethnicity in a San Jose Medical Center. Three-year average: 2005-2007.

My Own Clinic Service Scores

The innovation project began with my own clinic service scores in the Fremont Ob/Gyn Department. When I joined TPMG in 1979, there were very few female Ob/Gyn physicians and the options for women to choose a woman physician were limited. Over the years, this situation has changed as more women have entered the field of Ob/Gyn. Over time this changing expectation became apparent as women in younger age groups evaluated me lower than women in older age groups. It was common to be told by a younger patient that she did not want to see me because of my sex; over time this created a negative bias toward seeing women patients in the younger age group. It was apparent that I needed to change the bias I developed over the years if I was to improve my service scores. One intervention I employed was to attend the Four Habits Communication Program.3,4 My other key intervention was to improve the clinical experience of young women when they came in for care. This focused work paid off with a 60-point improvement in this population segment with a 10-point gain in my overall score over a six-month period.

Fremont Internal Medicine Department

The next phase of the project involved ten physician volunteers from the Fremont Internal Medicine Department who, over the next year, all improved their service scores by targeting key segments in their demographic data. As a result, the Fremont Internal Medicine Department became a Significant Improver (physician or group measured relative to themselves). On the basis of these results, the program was offered throughout the Hayward/Fremont facilities and to other facilities in the Northern California Region. Long-term tracking has the Hayward/Fremont facilities improving at a faster rate than the regional average from 2007 to 2008. Training programs have been developed for the physician, the chief, and diversity and communication consultants. Programs are now in development for staff, managers, and the support departments of the Laboratory, Pharmacy, and Radiology Departments.

It was apparent that I needed to change the bias I developed over the years if I was to improve my service scores.

Methodology

The Data, Diversity, and Demographics Program (DDDP)—a response to the MPS survey, which evaluates service—was developed at the Fremont/Hayward facilities located in northern California. Although this article describes the DDDP to demonstrate some early results, it is not meant to be an objective evaluation of the program.

Member Patient Satisfaction Survey

TPMG has long employed the MPS survey, which returns results on an average of 100 patient-survey results per year per clinician. Scores are tabulated quarterly and biannually and are broken out by categories including familiarity, gender, age, and ethnicity in five broad ethnic segments: African American, Asian, Latino, white, and other. A physician's overall score is displayed on page one of the report and has been emphasized as the indicator of a physician's service. The more granular data is found on page two, which was often ignored: its potential value not understood. Over time, the overall service score became an important component of an individual physician's performance evaluation, with critical implications.

The Program

The DDDP uses the existing service-score database from the MPS surveys and resources from other organizational areas: diversity, service, marketing, and human resources. Initially, focus groups were conducted with key demographic groups including Muslim, Indian, Chinese, Filipino, and young adults, which contributed specific cultural and demographic perspectives to the program design. An integrated marketing team works with the diverse population in the Fremont/Hayward area to create a positive brand image (with personal attention to patients of all ages and ethnicities) and with the Service Department to ensure service expectations are met. Human resources is included as a critical partner to support the needs of a diverse physician and staff population.

The training program consists of an hour of individual consultation with each clinician who is interested in the program after having received an MPS score. The consultation is confidential as issues may be raised that are quite sensitive. Part of the hour is spent talking about how MPS works and what to look for on the survey. The segmentation section is carefully examined letting the data open areas of discussion. High-scoring areas are recognized and commended and low-scoring areas are identified as opportunities. One or two tipping points are identified. A tipping point is defined as an area that will have the biggest impact on moving the overall score upwards. Physicians who score greater than 85% will have a small demographic subset on which to focus. Physicians with lower overall scores should look for a larger demographic subset on which to focus. Resource materials are then made available that will help the physician improve the targeted subset score.

Data Validity

At the beginning of the program some physicians offered resistance because of concerns about the validity of the data—the issue was statistical significance. With only a hundred surveys per physician per year, some segment categories represented only three to five survey returns whereas other survey categories could have 50 survey returns or more. This is a legitimate concern as there is normal data fluctuation, especially with smaller sample sizes. The solution was to track small sample sizes over a longer period of time observing for consistent trends.

Results

Population Intervention— The Chinese Patient

The Chinese population scores physicians the lowest in the MPS survey, whereas the white patient population scores physicians the highest. Some Chinese-speaking physicians with large panels of Chinese-speaking patients were having difficulties with their overall service scores. At one point, morale was suffering and physicians were either transferring or refusing to take on new Chinese-speaking patients. A workgroup of physicians was formed to study the issue and to create a strategy for improving professional satisfaction. Two Chinese-patient focus groups were held to better understand the needs of both Chinese patients and the physicians who care for them.

Some of the questions probed patients’ medical care experiences in China compared with their medical care experiences in the US. In China, for example, many patients didn't make appointments but dropped into the clinic expecting to be seen. Patients would often bring family members with the expectation that they would be seen as well.

Successful interventions that supported physicians included: expression of the awareness of the issues faced by Chinese physicians and acknowledgement of their hard work to satisfy patients. This led to retention of the Chinese-speaking physicians, which is a key strategy for membership growth and service score improvement. Other changes included: educating the chiefs about the issues, stronger interpreter services, cultural understanding of the Chinese MPS survey tool, and bilingual medical assistant support. Because it is not feasible for Chinese-speaking physicians to care for all Chinese patients in the service area, it is an expectation as a business imperative that all physicians be responsible for their demographic patient subsets. To meet that goal requires strong interpreter services, bilingual support staff, diversity training programs, translated materials, and leadership's understanding of the issues faced by bilingual physicians with large non-English-speaking panels.

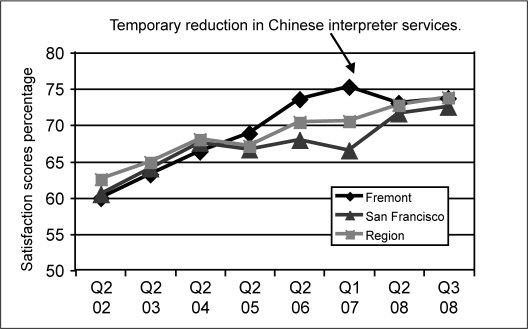

The intervention in Fremont started in 2002 and the work in San Francisco started in the summer of 2008. San Francisco has a strong diversity program and is a leader in innovation such as the Chinese module and Chinese translation services. Figure 2 shows the impact on service scores at the facility and regional level. San Francisco and Fremont, with large Chinese populations, are moving the regional average up; however, Fremont scores dropped when the Chinese interpreter services were temporarily reduced.

Figure 2.

Chinese Member Patient Satisfaction survey scores (quarterly/year) for the Fremont Medical Center, the San Francisco Medical Center, and the Northern California Region.

Population Intervention— The African-American Patient

One physician who had consistent overall scores in the high 80s (top of range 100) had only one low-group (segment) score over a three-year period: the African-American score of 40 to 50, which was based on only three to four surveys returned per year. This was consistent with the population ratio in Fremont. The physician agreed to focus on this population subset and over the next year this subset score moved up, as did the overall score, now in the low 90s. The physician used cultural information such as the Handbook on Culturally Competent Care for the African-American Population5 available from National Diversity.

System Intervention—Urologists

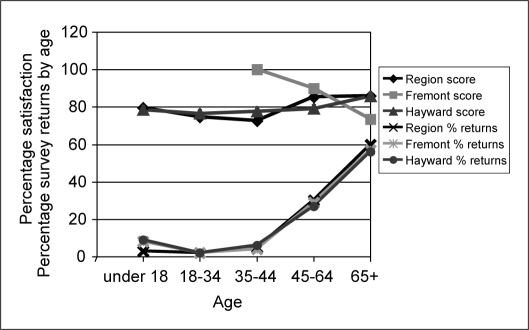

Systems issues are critical and understanding their impact on service scores is crucial. A low service score number does not define the problem but gives direction on which areas to focus. For example, in the Fremont Medical Center Urology Department, physicians were receiving lower scores from older men but those at the Hayward Medical Center were not, even though the same five urologists were working at both campuses (Figure 3). We found that the Fremont campus had no ultrasound machine to diagnose prostate cancer, so the men had to be rescheduled a month later at the Hayward campus. After an ultrasound was purchased the urologists’ service scores went up in that particular age group. The problem lay with the system and not with the physicians. A problem area was identified in the MPS score and deeper exploration found the solution.

Figure 3.

Satisfaction scores and percentage of survey returns: Urology Department, male patients.

Context—Work Environment

Seeing data in context is critical to understanding what the data shows. Numbers by themselves have no meaning out of context. An example was a physician who normally scored in the 90s, then had a drop-off of her overall MPS score into the 70s for one quarter. The physician was puzzled; however, it was the quarter during which she went to another facility to help out while they trained on the HealthConnect electronic medical record. The physician saw all new patients and never had the same office or medical assistant. After she returned to her regular department, her scores rose again to the 90s. Statistical variation is normal—even 15 to 20 point swings between quarters with survey returns only numbering 20. Too often physicians and chiefs, caught up in short-term statistical swings, don't look at the overall trend.

Tenure and Physician Retention

Tenure is an important factor in understanding a physician's service scores. A new physician has a large proportion of new members and a small proportion of regular patients. Over time this corrects itself as patients bond with the physician and the percentage of returning patients increases. This alone accounts for much of physicians’ improving their scores over time. However, it may take longer for physicians who come from other countries and for whom English is a second language.

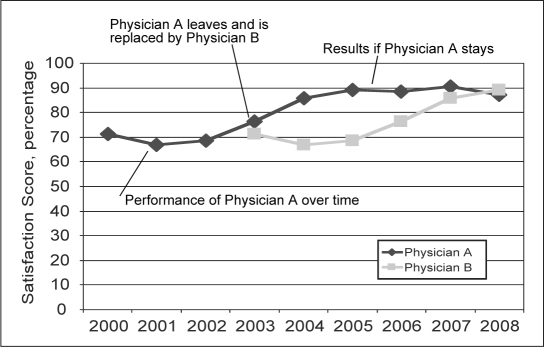

Figure 4 shows a common pattern for a new physician in that a service score drop in the second or third years of practice are common. This physician started in the year 2000 with a score of 70 and then had a decline for the following two years. After year three, the physician showed steady improvement and now scores consistently in the high 80s to low 90s. The improvement did not happen, however, until after the time for a partnership vote had passed. If physician A had quit or not made partnership in 2003, a new physician being hired would start the process over again. The patients in the panel of Dr A would have to be reassigned to a new physician with an overall negative impact on service scores.

Figure 4.

Affect on overall satisfaction scores when a new physician replaces another physician compared to when a physician is retained.

Looking at score subsets gives a chief more information on which to evaluate a physician's true performance.

Discussion

Even though the program is still in an early phase, we believe some observations will prevail over time. The MPS survey is extremely accurate in evaluating service scores with demographic subsets, and, as a corollary, it has been very difficult for some physicians to improve service scores by just focusing on the overall score. Using the knowledge they gain from examining their demographic subsets is an efficient and effective use of the physicians’ time because they can target those subsets that bring down the overall score: sex, age, ethnicity, or some combination of those factors. Another observation is that physicians are often unaware of which subgroups of patients mark them low, and it is only with this data that weaknesses are identified. Furthermore, there are demographic subsets that are of critical importance to the organization for membership growth and retention—new members, young adults, and emerging ethnic markets are critical for long-term success yet lag other groups in satisfaction. The program not only improves service scores it also becomes part of the business case for attracting key membership growth.

The Golden Rules of Service

There are two basic guidelines for a clinician to follow to do well with a diverse patient population. The golden rule is to treat someone like you want to be treated. Having areas of cultural similarities helps to create trust between the patient and clinician. It is much easier for a physician to create an established panel when there are areas shared by both patient and physician. An example was one woman from the Filipino focus group who shared her preference for an Ob/Gyn physician. Her first choice was a female Filipino; second choice, male Filipino; and third choice, any Asian physician. She felt it necessary to have the “Asian issue” out of the way before she could trust a physician. With a female Filipino physician she would have immediate common interests, whereas with a non-Asian physician she would have to work to establish a trusting relationship. A caring physician who takes the time to establish trust can usually succeed in creating a positive clinical experience.

The Platinum Rule of Service

If a patient differs culturally from the physician, however, follow the platinum rule: treat a person how they want to be treated. One can never stereotype because there are always exceptions to the rule. Three sisters in the Muslim focus group had very different expectations about whom they wanted for a physician. One dressed very conservatively in a black hijab and would not see a male physician under any circumstance. Another would see a male physician if her husband was present in the room. The third, wearing casual Western attire, had no issues seeing a male physician. Taking extra time to learn about a culture different from the physician's, and investing extra time in creating a positive experience, will create a professional relationship with the majority of patients.

KP has well-developed educational materials regarding effective ways for clinicians to communicate with patients of diverse backgrounds.

Focus on Three Areas

There are three key areas to focus on to improve service scores and membership growth. Physician retention is crucial as a long-term strategy because patient trust is built over time, and the result of physician turnover is the patient again seeking a physician they trust. Second, system issues may affect scores or create physician dissatisfaction resulting in physicians leaving. The third component of segmenting scores is to recognize physicians for the value they bring, while pointing to areas for improvement.

Service Score Analysis

When going through the service score analysis, generally physicians are very reluctant to discuss their scores especially if they are low. They may have doubts about the validity of the numbers, be cynical about the value of these scores, or not see the importance. When diversity issues are raised, physicians are very concerned about being perceived as biased or prejudiced. It is absolutely critical to create a safe environment when discussing service-score issues. Recognition of physicians’ areas of excellence is critical. To be complete the discussion must contain systems’ issues and physician retention.

Conclusion

The DDDP, which started in 2003 with a single physician, has now been implemented in seven KPNC facilities; there are three more on the waiting list. The program is entirely voluntary and has expanded based on the results that have been seen—a true grassroots program. The core concept is using segmented data and analyzing the numbers to identify tipping points at the department and individual level. It recognizes areas of excellence for each physician and identifies areas of opportunity. The balance between recognition and accountability is a key aspect of the success of the program. Identifying systems’ issues is a key component that adds credibility to the program. The analytic component though key is only as strong as those doing the analysis. Having trained physicians to mentor and coach other physicians on how to provide consistent care across all demographic groups is crucial. Recognizing the value that all clinicians bring is the final piece for success. On the basis of learnings to date, the concepts from the DDDP are being applied to other areas. A program is now in development looking at hospital scores (HCAHPs). Health care disparity is another critical issue where segmented data is crucial to identify groups at risk. The last area is unconscious bias, which is a contributing factor to health care disparities. It is believed that the DDDP will play a significant role in identifying unconscious bias when present in both the physician and the patient. This work is being done in collaboration with Massachusetts General Hospital.6,7

… treat someone like you want to be treated… If a patient differs culturally from the physician, however, … treat a person how they want to be treated.

Footnotes

a Senior Analyst, Market Strategy and Analysis Department, The Permanente Medical Group, Oakland, CA

Disclosure Statement

The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to give special thanks and acknowledgment to Kristen Gregory, PhD, and her staff for their support in this project. They volunteered hours of their time to help this project move forward.

Mosaic

We have become not a melting pot but a beautiful mosaic. Different people, different beliefs, different yearnings, different hopes, different dreams.

— Jimmy Carter, b 1924, 38th President of the US and 2002 Nobel Peace Prize recipient

soul of the healer

“Peace and Prayers in Bhutan” photographs By Anita Kulkarni, MD

Dr Kulkarni is an Emergency Medicine Physician at the Santa Clara Medical Center in Santa Clara, CA.

The Bhutanese people believe that prayers inscribed on each prayer flag are being recited every time the flag flutters in the breeze. Walking across a bridge being surrounded by peace and prayers … .

References

- 1.Holton L. New study confirms California's changing demographics, Release No. 61 [press release on the Internet]. Sacramento, CA: Judicial Council of California Administrative Office of the Court Pubic Information Office; 2000 Oct 31. [cited 2009 Oct 8]. Available from: www.courtinfo.ca.gov/presscenter/newsreleases/NR61-00.HTM.

- 2.Economicexpert.com. [homepage on the Internet] Montreal, Quebec: Economic Expert; updated 2009 Oct 8 [cited 2009 Oct 8]. Available from: www.economicexpert.com/a/Fremont:California.htm.

- 3.Stein TS, Kwan J. Thriving in a busy practice: physician-patient communication training. Eff Clin Pract. 1999 Mar-Apr;2(2):63–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stein T. A decade of experience with a multiday residential communication skills intensive: has the outcome been worth the investment? Perm J. 2007 Fall;11(4):30–40. doi: 10.7812/tpp/07-069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaiser Permanente National Diversity Council, Kaiser Permanente National Diversity Department. A provider's handbook on culturally competent care. 2nd ed. Oakland, CA: KaiserFoundation Health Plan, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sabin J, Nosek BA, Greenwald A, Rivara FP. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009 Aug;20(3):896–913. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sabin JA, Rivara FP, Greenwald AG. Physician implicit attitudes about stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care. 2008 Jul;46(7):678–85. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181653d58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]