Abstract

A k-space-time Bayesian statistical reconstruction method (K-Bayes) is proposed for the reconstruction of metabolite images of the brain from proton (1H) Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging (MRSI) data. K-Bayes performs full spectral fitting of the data while incorporating structural (anatomical) spatial information through the prior distribution. K-Bayes provides increased spatial resolution over conventional discrete Fourier transform (DFT) based methods by incorporating structural information from higher-resolution co-registered and segmented structural Magnetic Resonance Images. The structural information is incorporated via a Markov random field (MRF) model that allows for differential levels of expected smoothness in metabolite levels within homogeneous tissue regions and across tissue boundaries. By further combining the structural prior model with a k-space-time MRSI signal and noise model (for a specific set of metabolites and based on knowledge from prior spectral simulations of metabolite signals) the impact of artifacts generated by low-resolution sampling is also reduced. The posterior mode estimates are used to define the metabolite map reconstructions, obtained via a generalized Expectation-Maximization algorithm. K-Bayes was tested using simulated and real MRSI datasets consisting of sets of k-space-time-series (the recorded free induction decays). The results demonstrated that K-Bayes provided qualitative and quantitative improvement over DFT methods.

Keywords: Bayesian Image Analysis, Expectation-Maximization, K-Bayes, Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy Imaging (MRSI), Metabolite maps, MRSI reconstruction

I. Introduction

Magnetic resonance (MR) techniques provide a means for mapping a number of physical and chemical parameters in the human body. In particular, magnetic resonance spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) [1, 2] combines the spatial sampling methods of structural magnetic resonance imaging (structural MRI) with sampling of a spectroscopic data dimension, thereby enabling discrimination of multiple resonance frequencies and mapping of multiple tissue metabolites. MRSI information is of diagnostic interest because alterations of metabolite concentrations can provide a more sensitive indication of disease than observing tissue structure via structural MRI alone.

The spatial resolution of MR techniques differs greatly, from approximately 1 mm3 for structural MRI (which images anatomy through measurement of variation in water concentration) to 1000-2000 mm3 for MRSI. This is because concentrations of metabolites are approximately a factor of 10,000 times smaller than that of water, leading to lower signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for MRSI than structural MRI. The lower SNR must be partially offset by obtaining data at much lower spatial resolution, i.e. by sampling at fewer spatial frequencies, usually the center region of k-space (or spatial frequency-space).

Proton (1H) MRSI datasets consist of a set of (discrete) time series with typical lengths on the order of 512 timepoints. Each series is recorded at an individual point in k-space, (kx, ky), where the various kx and ky values correspond to different settings of the x and y direction magnetic field gradients, respectively. Typically, a set of slices to cover the brain is recorded and the z - (or slice) direction can be encoded in standard image space through gradient slice selection or as a 3rd k-space dimension. The k-space data are usually recorded in the form of a square lattice over k-space, and this is the form of the data considered here. However, an advantage of the proposed modeling scheme over standard discrete Fourier transformation (DFT) methodology is that it can naturally incorporate any k-space sampling schemes, for example where the center of k-space, which has the greatest SNR, is sampled the most densely.

The most widely used methods for reconstructing MRSI datasets focus on 4D DFT and spectral fitting or 3D spatial DFT followed by time domain fitting [3-6]. Conventional use of DFT for reconstruction of low-resolution MRSI data produces low-resolution images and artifacts associated with the limited sampling of spatial frequencies, such as Gibbs ringing, aliasing and blurring. Moreover, DFT has no mechanism for regularization via the incorporation of prior information, e.g. noise is transformed directly from k-space to image space. While a number of techniques have been suggested to address these issues individually (see e.g., Chapter 8 of Liang and Lauterbur [7]), a unified solution would be of great utility.

A number of general methods for improving spatial resolution within MR modalities have been proposed; however none of these has the dual advantage of combining a low-resolution k-space-time data generation model with prior information obtained from high-resolution structural (anatomical) scanning methods. Reconstruction to higher resolution using Bayesian image analysis methods for multi-contrast structural MRI is presented in [8]; however, they do not incorporate a full signal model and hence are subject to all of the problems with artifacts that are incurred from use of the DFT for reconstruction of low-resolution modalities. A model that incorporates a raw signal model for structural MRI was presented for maximum likelihood estimation in [9] and Bayesian maximum a posteriori reconstruction in [10]; however, the first model's focus was on high-resolution structural MRI, and the only prior information considered in [10] was a notion of overall a priori smoothness. Denney and Reeves [11] have developed a Bayesian approach for MRSI reconstruction that models the data in k-space-time and utilizes an edge preserving prior. They do not directly model the raw k-space-time series data of MRSI but instead use spectrally integrated estimates of the metabolites at each k-space point; for the paper they only considered the relatively strong water and lipid signals. Important uncertainty information is discarded when ignoring the original data and working with spectrally integrated estimates directly. Furthermore, the edge-preserving prior does not utilize tissue class information that could be valuable when determining effects specific to certain tissue types.

A related body of literature exists for the Bayesian reconstruction of emission tomography data using a co-registered and segmented structural MRI as prior information [12-14]. The idea is to model the distribution of counts at the receptors from individual voxels and combine this with structural prior spatial models of varying types, including models that incorporate line site detection for determining the tissue boundaries [12]; models that classify into a number of tissue regions within the emission tomography map [13]; and tissue composition models similar to the prior spatial model developed herein for MRSI [14].

A number of papers [15-20] aim to use tissue classification information to improve the reconstruction (and associated resolution) of MRSI data outside the Bayesian framework. The idea is to utilize basis function in order to smoothly represent signals within homogeneous tissue areas. Because it needs to be kept sparse (either by limiting the size of the basis set or by penalizing selection from a larger basis set), the basis function representation restricts the space of potential reconstructions. The earliest basis sets used were piece-wise constant functions such as those used in Spectral Localization by Imaging (SLIM) [15] and in Spectral Localization with Optimal Pointspread function (SLOOP) techniques, [16]. The SLOOP method extends on SLIM by optimizing the set of phase encoding gradients to match the pointspread function of the volumes of interest. The SLIM piece-wise constant basis function approach was also generalized to a wide range of basis function sets through the generalized series formulation [17]. A related Bayesian method is proposed by Haldar et al [21] that combines the basis set approach with prior structural information. The idea is to obtain k-space data at high-resolution, accepting significant loss of SNR in the data, and then use a structural prior distribution with “soft” edge classifications to recover the lost SNR.

In this report, an alternative image reconstruction method based on a combination of MRSI process modeling and Bayesian image analysis is presented for the enhancement of metabolite maps (K-Bayes). First developed for (non-dynamic) perfusion MRI [22, 23], the K-Bayes approach is here expanded considerably to accommodate the additional spectral fitting problem inherent to MRSI. K-Bayes combines information from high-resolution tissue segmented structural MRIs with low-resolution k-space-time MRSI data. The acquired MRSI data are supplemented by additional sources of prior information that characterize known relationships between local tissue structural patterns and the spatial distribution of metabolites in the brain. Therefore, K-Bayes effectively performs a full spectral fitting of the data along with incorporation of spatial information. To the authors’ knowledge, there are no other existing reconstruction methods that use a true Bayesian k-space-time signal acquisition model to directly reconstruct metabolite maps from low-resolution MRSI data. K-Bayes thereby provides a unified solution for reducing artifacts and increasing image resolution and accuracy.

II. The K-Bayes Model

The main modeling objectives of K-Bayes for MRSI data are: 1) to incorporate a full signal (and noise) model to relate the raw k-space-time data to the metabolite maps to be reconstructed and 2) to incorporate anatomical information from high-resolution structural MRIs. This is achieved within the framework of Bayesian image analysis modeling [24-26]. The definition of a full k-space-time signal acquisition model alongside a noise model forms the likelihood part of K-Bayes. The prior distribution for K-Bayes relates the spatial distribution of metabolites to a high-resolution and coregistered structural MRI that is segmented into gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), and cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF). The prior model incorporates knowledge of the expected ‘smoother’ behavior of metabolites within homogeneous tissue regions as opposed to less smooth behavior across the boundaries of different tissues; differences between gray and white matter metabolite concentrations have been determined to reach as much as 30% for creatine (Cr) in the temporal lobe and choline (Cho) in the parietal lobe [27]. That is, neighboring locations within homogeneous tissue type are expected to have more similar values than either 1) neighboring voxels of different tissue type, or 2) voxels of homogeneous tissue type that are further apart. These expectations are incorporated into a prior distribution via the use of Markov random field (MRF) models [25, 26, 28] that describe (probabilistically) the spatial distribution of metabolites: characterizing the different spatial correlation structure of metabolites within homogeneous tissue regions compared with that across tissue boundaries. Also incorporated into the prior distribution is the knowledge that metabolite levels should be zero outside the head and can be assumed negligible within CSF. The information in the data (incorporated via the likelihood) and the structural information used in the prior distribution are combined via Bayes’ Theorem. The combination leads to a posterior distribution of metabolite maps that is defined at the higher resolution of the structural MRI. K-Bayes reconstructed metabolite maps are obtained by maximizing the posterior distribution. Maximization is achieved by applying an iterative (generalized) Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm [29] to an expanded set of model variables.

A. The K-Bayes MRSI Signal Model and Likelihood

The 4D multi-slice MRSI signal model for K-Bayes both corrects and expands upon the model given in Young et al. [4] and Soher et al. [5]. Each signal time series, s(kx, ky, w,t), for a fixed kx, ky and w, is modeled as a discretely sampled, exponentially decaying, sum of sinusoids that correspond to the resonance frequencies of the metabolite spectra present. Here, kx, ky represent the strength of the magnetic field gradients in the x and y directions respectively (the k-space position); w represents the MRSI slice index; and t = 0,δ,2δ,...,δ(T – 1) represents time after the onset of the free-induction-decay (FID), or from the maximum of a signal echo. The model relates the complete set of k-space complex time-series to 3D image volumes of metabolite signals located at different spectral frequencies (the metabolite maps):

| [1] |

The multiple integral of Eq. [1] is evaluated over each voxel at the higher resolution of the structural MRI. The signal s(kx, ky, w,t) at each k-space-time-point (kx,ky, w,t), sums the contribution to that signal from all voxels and metabolites, namely, all voxels in the w-th MRSI slice. The w-th MRSI slice corresponds to slices wc to (w + 1)c – 1 of the structural MRI (where c is the number of structural MRI slices corresponding to a single MRSI slice). The set Λ = {(p,q,r) : p = 0,..., P – 1; q = 0,...,Q – 1; r = 0,..., R – 1} is the set of voxel locations at the structural MRI resolution, which is ultimately the set of locations for which the metabolite maps are to be reconstructed with K-Bayes. (Note therefore that in general the set of voxels included in this sum is a function of the particular 3-D structural MRI pulse sequence used.) Hence, reconstructed voxels are to be indexed by (p,q,r) and the triple integral is over the voxel centered at those coordinates. The index m is over the individual metabolite compounds each having N(m) resonance lines with amplitudes Lmn (known from a priori spectral information, e.g. based on spectral simulation or obtained from phantom datasets). The number and distribution of spectral lines are considered constant across voxels, though the model can be extended to allow these to vary. In the current formulation, the metabolite lines and their relative ratios are fixed in advance with the overall amplitude as the only varying component to be estimated by K-Bayes.

Therefore, the quintuple summation in Equation [1] is over all metabolites, resonance lines and voxels in the w-th k-space slice. The Am(x,y,z) values are the unknown quantities of interest, i.e., the metabolite amplitudes over the brain, and are reconstructed over the set of high-resolution voxels Λ. Other terms in the model are: ωm representing the frequency shift for metabolite m; ωmn a small relative frequency shift for resonance line n from ωm; B0(x,y,z) the magnetic field inhomogeneity map; ϕmn a phase shift for resonance line n of metabolite m, again known from prior knowledge, and ϕA(x,y,z) is a so-called “zero-order phase adjustment map”. The terms Ta(x,y,z) and Tb(x,y,z) correspond to Lorentzian and Gaussian decay rates, respectively. Note that the decay rates can be further extended to vary as a function of line or multiplet group, but that would be beyond the scope of any current metabolite estimation methodology know to the authors and we opt for the more parsimonious form here. The model contains no explicit modeling of a broad, smoothly varying baseline signal (in the spectral dimension) due to lipid and macromolecular contributions. We propose two possible approaches to incorporate the baseline signal in K-Bayes: 1) estimate and subtract the baseline signal from the data DFT'd in all four dimensions (4DFT) and then 4DFT back the baseline-subtracted data to k-space-time, or 2) since the macromolecular component of the baseline signal is actually composed of a finite number of quickly decaying resonances, we could model the baseline signal directly as the sum of a set of individual metabolite contributions with short T2. (In the applications in this paper we used approach 1.)

Note that for 3D k-space acquisition sequences (as opposed to multi-slice acquisition), Eq. [1] requires slight modifications so that s(kx, ky, w,t) becomes s(kx,kykz,t): the summation over r becomes a sum for r = 0 to R – 1 (where R is the number of high-resolution voxels in the third dimension, i.e. z -direction), and the spatial localization term in the exponential includes an extra kzr / R component.

The Ta, Tb, ϕA, B0 spatial maps are estimated in advance (alongside baseline estimates if using approach 1 for baseline correction) using an initial analysis of the MRSI data: automated spectral fitting (SITools-FITT) [5]; these are then spatially interpolated to give values at the required higher resolution of the structural MRI. The interpolated Ta, Tb, ϕA and B0 maps are subsequently assumed to be fixed and known. Estimated maps of the metabolites of interest are also interpolated and used as starting values for K-Bayes. The ωm , ωmn, ϕmn values can be obtained by spectral simulation [3].

An important issue that arises in the implementation of this model is how to choose the metabolites and associated resonance lines to include in the model. This precise choice would be experiment and TE-specific. Obviously all metabolites of interest in the study should be included, as well as any other metabolites that are thought to contribute a significant signal (thereby reducing residual noise levels). The papers by Young et al. [3, 4] and Soher et al. [5] address the choice of metabolites and spectral lines for inclusion in MRSI signal models in detail.

1. After performing the integration the model becomes:

| [2] |

where sinc(x) = sin(x) / x . An implicit assumption for this model is that Am, B0, Ta, Tb, and ϕA, are constant over each voxel at the resolution of the structural MRI. This assumption is not too restrictive when imposed at the high-resolution of the structural MRI as there is no additional empirical information available at higher resolution. This mechanism of increasing all maps to the highest resolution available enables the reconstruction of metabolite maps at enhanced resolution with maximal information.

The process s(kx,ky,w,t) cannot be observed directly, but only after contamination by noise. The resulting noisy signal (i.e. data, d) is modeled as

| [3] |

The error/noise component is modeled as isotropic complex Gaussian noise: ε(kx,ky,w,t) ~ CN(0, σ2I2), where CN(μ,V) is used to denote a bivariate Gaussian distribution with the first component representing the real and the second the imaginary part of a complex random variable with vector mean μ and covariance matrix V. The independence imposed by the covariance matrix σ2I2 provides for an isotropic noise distribution in the complex plane.

This leads to the following likelihood for the full dataset:

| [4] |

where π(·) is used to denote a generic probability distribution. Note that indices are omitted to indicate the full array, i.e. writing d instead of d(kx,ky,w,t).

B. The K-Bayes Prior Distribution

A segmented and co-registered structural MRI (that could be acquired within the same experimental session as the MRSI) provides a readily available and detailed source of prior spatial information. The acquired structural MRI is segmented into GM, WM, and CSF, using one of the many available segmentation algorithms [30, 31]. The goal of the prior distribution is to characterize known behavior of metabolites within homogeneous regions of tissue. The segmentation information is incorporated into the model via a prior distribution that satisfies two criteria: metabolite levels should be encouraged to vary smoothly across space within each of the tissue types of GM and WM, and sharper changes in metabolite levels should be considered more feasible at the identified GM-WM boundaries and at edges of the brain or ventricles. Regions outside the brain or areas of CSF should not have a detectable metabolite signal. These criteria provide information to the K-Bayes model regarding the spatial distribution of metabolites within homogeneous and heterogeneous tissue regions and can be mathematically represented within a prior distribution based on MRF models [26, 28, 32]. The prior model used here is defined at the spatial resolution of the structural MRI as follows:

| [5] |

with the added constraint that Am is assumed zero everywhere both outside the brain and within regions consisting of CSF. (This condition can be relaxed if required.) The sum in Eq. [5] over < (p,q,r),(p',q',r') > is over all pairs of ‘neighboring’ voxels (p,q,r), (p',q',r') and is only over first-order neighbors, i.e. where only horizontally and vertically adjacent pairs are considered to be neighbors; though this can be generalized to higher-orders (and in the language of the MRF literature, arbitrary cliques) in a straightforward manner. The functions IG[(p,q,r),(p',q',r')], IW[(p,q,r),(p',q',r')] and IB[(p,q,r),(p',q',r')] are indicator functions for matching pairs of GM, WM and brain tissue (GM or WM) voxels, respectively, e.g. IG[(p,q,r)(p',q',r')] = 1 if both (p,q,r) and (p',q',r') are GM voxels and = 0 otherwise. The parameters , , and control the level of stochastic smoothing between neighbors (stochastic because it is determined by a random field model that describes the similarity of neighboring values); describes the a priori expected smoothness of non-matching tissue type neighbors, and , describe the extra components of smoothness for GM and WM neighboring pairs, respectively. (The m index allows these parameters to be different for each of the metabolites.) This prior distribution model can be considered as an extension of the intrinsic pairwise Gaussian difference prior [33, 34]; extended such that the smoothness parameter depends on the tissue type(s) of the voxel pairs. The prior therefore acts as an adaptive stochastic smoothing mechanism that is able to reduce the level of smoothing constraint when crossing tissue type boundaries. The variance/smoothing parameters , , and could be estimated directly via an additional E-step in the EM algorithm (described below) for a set of training subjects chosen from existing datasets acquired under the imaging protocol. Averages of these estimates could then be used as fixed parameter values in all future datasets acquired under the same imaging protocol. Fixing parameters within any multi-subject imaging study is important to avoid inducing potential biases for group comparisons. As an alternative approach to estimating the parameters, we could choose , , and by calibrating past experimental results to match the biological expectations for the spatial structure of metabolite maps. This would require a complex process whereby, for example, a biologist would sit and review reconstructed maps based on different sets of prior parameters (again from a training set) and score them based on their biological plausibility. Finally, note that if the dimensions of voxels are not isotropic, then , and should not take the same values in all principle directions.

C. Posterior Estimation

In order to obtain an estimate (reconstruction) of the metabolite maps, the posterior distribution is maximized with respect to the sets of metabolite amplitudes at all voxels. This is equivalent to maximizing the product of the likelihood and the prior distribution and is only one of many possible estimates that can be obtained from the posterior distribution. However, it is a common choice for Bayesian image analysis because a) it is easy to understand, and b) there is known (and relatively computationally efficient) methodology that can be used to obtain it [26]. A generalized form of the Expectation-Maximization (EM) procedure [29] was used for optimization. The algorithm is generated in a similar fashion to the algorithms in Green [35] and Miller et al. [9], where a set of unobservable latent variables is created to simplify the computational algorithm. These variables are treated as missing data within the EM algorithm. The latent variables for the EM reconstruction approach described here are defined as:

| [6] |

The term z(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m) is the contribution of data (signal plus noise) at k-space location (kx,ky) within slice w and at time t to the total amount of metabolite m within voxel (p,q,r), namely, Am(p,q,r). The noise term εz(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m) ~ is based on the assumption that the signal noise for a particular k-space-time data point is distributed with even magnitude across all voxels and metabolite signals in the associated MRSI slice. This is not the same as saying that the noise structure is homogeneously distributed across the reconstructed metabolite maps. The K-Bayes model does not directly relate to the overall noise structure in image space, but only to a single k-space-time point. A key advantage of K-Bayes is that noise generated by non-uniform k-space sampling schemes such as spiral or radial acquisitions is appropriately modeled without the need to reference the noise structure in image space.

Note that the individual z -variables are not actually defined in a rigorous sense because of the uncertainty principle, i.e. it is impossible to simultaneously specify a point precisely in both k -space and image-space [36]. However, because we only consider different linear combinations of the z -variables (which are well defined) within the M-step of the EM optimization procedure, our methodology remains valid at all times.

For a certain set of starting values an iterative procedure is taken where firstly the expectation is calculated for each z -variable given the current values of the metabolite amplitudes Am and all other z -variables (the E-step). When all the z -variables have been calculated, the metabolite maps are then re-calculated by maximizing the conditional posterior distribution given the current estimates of the z -variables for each Am(p,q,r) in turn (the M-step). The algorithm then iterates between E- and M-steps and is considered to have converged when there are no further changes (to some specified tolerance) of the Am terms within subsequent iterations. For the M-step the image is stepped-through in a checker-board manner; all the ‘black squares’ are updated followed by all the ‘white squares’. This creates maximally independent coding sets [32] of voxels for a first-order MRF as used here. The E- and M-steps have analytic solutions for each variable, and thus no approximation or iterative procedures are required. However, if K-Bayes were extended to incorporate further terms as unknowns (such as Ta and Tb currently estimated outside K-Bayes using SITools-FITT), numerical optimization procedures would be required. The specific E- and M-steps are derived in the Appendix. The j -th iteration of the K-Bayes EM algorithm has E-step:

| [7] |

where ν = cPQ the number of high-resolution voxels in each structural MRI slice.

The corresponding M-step is:

| [8] |

where j* can be taken as j – 1, or for slightly improved performance, the latest available update (either j – 1 or j).

D. Algorithmic Implementation

To implement the K-Bayes algorithm the following steps are required.

Perform conventional DFT-based reconstruction of the MRSI data using e.g. freely available SITools-FITT

Spatially zero-fill all fitted parameter maps Am, Ta, Tb, ϕ, B0, effectively interpolating the maps to structural MRI resolution.

Coregister and re-slice high-resolution structural MRI data to match interpolated DFT reconstructed maps.

Segment re-sliced structural MRI into GM, WM, CSF and non-brain for use as prior information in K-Bayes.

Use original k-space-time data and segmented re-sliced structural MRI as input to K-Bayes. The interpolated DFT fitted metabolite maps can be used as start values for the K-Bayes reconstructed maps.

Iterate between E- and M-steps of the K-Bayes algorithm until the reconstructed metabolite maps have all converged to within some specified acceptable tolerance.

III. Simulation Study

The simulation study compared K-Bayes and conventional DFT reconstruction under controlled conditions. The study utilized simplified versions of the full K-Bayes model described in Eqs. [1] and [2]. The first general simplification was that all phase and frequency offset terms were set to zero and that the Ta and Tb were fixed at spatially constant values. Since these terms are a priori assumed known in the current K-Bayes implementation (from direct estimation or prior simulation), these assumptions (and value choices) were made without loss of generality; we could have chosen any viable values for these parameters and then assume them as fixed and known to get the same result. Note that this simplification is only valid because they are set that way in the simulation. These assumptions are not valid for real data (and are not made in the real data examples later) where Ta and Tb do vary spatially, and phase and frequency offset terms do not equal zero. In real data reconstructions these parameters will be estimated, thereby inducing some error propagation (see Discussion). The second simplification was to incorporate only two spatial dimensions (single slice datasets are common in MRSI). The data were modeled as long time-to-echo (TE) data so that only single resonance frequencies needed to be incorporated for each metabolite. Therefore, the assessment of K-Bayes is not unduly limited by focusing on single resonance frequencies for each metabolite, as observed with long TE. Note that the resonance frequencies (and relative amplitudes of the multiple metabolite resonances seen in short TE data) are assumed to be known in advance from spectral simulations [3]. Although the resonance values from spectral simulations will contain some error, they will be very accurate. In particular, given the level of accuracy and precision of the simulated resonances, an MRSI dataset that is being reconstructed is unlikely to significantly improve estimation of the true resonances.

In 2D, with single metabolite frequencies, Eq. [2] reduces to:

| [9] |

and the likelihood and prior distribution are similarly reduced to only two spatial dimensions. The extensions to 3D space and short TE data are straightforward (in terms of coding), but have increased computational burdens.

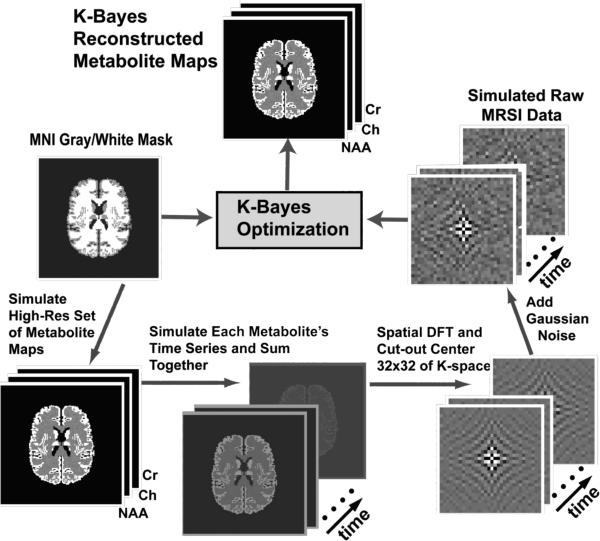

Figure 1 outlines the data simulation and reconstruction procedure. The simulated MRSI dataset was generated based on the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) structural MRI of the human brain [37] that had been segmented into GM, WM, and CSF. The k-space-time data was created by first generating a high-resolution metabolite intensity map with concentrations of 1.0 in GM and 0.5 in WM from the segmented MNI brain (128×128). The ensuing map was used to generate individual high-resolution metabolite maps for each of N-acetylaspartate (NAA), Cr and Cho with relative amplitudes of 1.0, 0.25, and 0.5, respectively. The difference in overall intensity for the three metabolite maps seen in Figure 2 is indicative of the relative metabolite concentrations. ‘Hotspot’ high-intensity regions were added in the WM regions for NAA and Cho such that the WM intensity was doubled (indicated by arrows in Figure 2). The hotspots were included for the purpose of testing whether K-Bayes was robust to spatial changes not matching prior expectations; i.e., to what extent would the MRF prior distribution smooth away metabolite variation that did not correspond to structural boundaries. Finally, nearest-neighbor spatial smoothing was applied across the metabolite maps to simulate a small bleeding effect across tissue boundaries: each voxel's value was replaced by the mean of the combination of itself and its four nearest neighbors.

Figure 1.

Simulation study procedure: Simulated high-resolution metabolite maps are generated based on a structural MRI segmented into GM, WM, and CSF. At each high-resolution voxel the time-series signal was generated as the sum of exponentially decaying metabolite frequencies corresponding to the metabolite resonance frequencies. The data are then DFT'd spatially into k-space-time and the central 32×32 region of k-space is extracted to yield low-spatial-resolution k-space-time data. Finally, independent complex Gaussian noise is added at each k-space-timepoint. The generated low-resolution k-space-time MRSI data along with the segmented structural MRI are the input for K-Bayes.

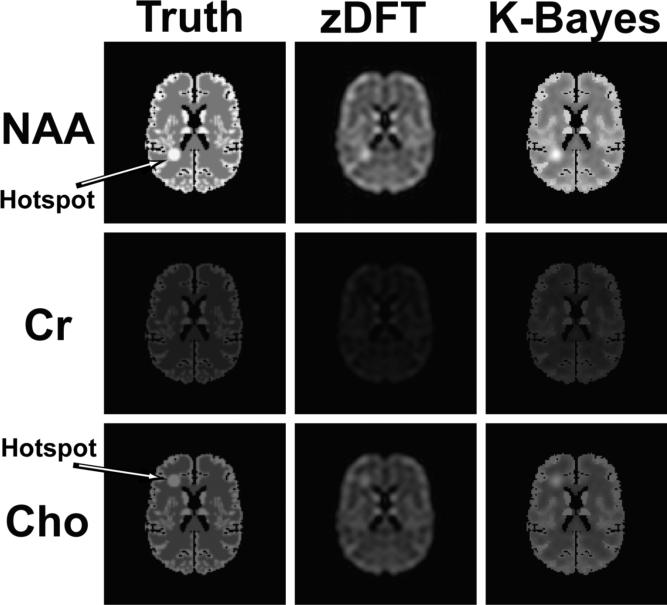

Figure 2.

Reconstructions of MRSI simulated data for three metabolites each of which has a single resonance frequency. Each row corresponds to a single metabolite and the columns correspond to the truth, zDFT and K-Bayes reconstructions, respectively. The true simulated maps for each metabolite differed only in terms of overall intensity and presence or location of hotspot. The difference in overall intensity for the three metabolite maps is indicative of their relative metabolite concentrations. K-Bayes provided consistently superior reconstructions for all three metabolites.

High-resolution image-space-time data (length 128 timepoints and sampling interval of 1.0 milliseconds) were generated from the set of metabolite intensity maps. At each voxel the signal was generated as the sum of three exponentially decaying metabolite frequencies (NAA, Cr, Cho). The metabolite frequencies were simulated at 2.0 parts per million (ppm) for NAA, 3.0 ppm for Cr and 3.2 ppm for Cho. The signal's magnitude at each frequency was defined by the intensity of the voxel in the associated metabolite map. The signal was simulated separately for each point in high-resolution-image-space in order to approximate a continuous spatial process and the data were then DFT'd spatially into k-space-time. The central 32×32 region of k-space was then extracted to yield low-spatial-resolution k-space-time data. Finally, independent complex Gaussian noise was added at each k-space-timepoint with standard deviation of 0.1. This low-resolution data along with the original segmentation (i.e. tissue type) data became the input for K-Bayes.

We tested different combinations of values for σ2, , , and within the model, and found that the resulting reconstructions were reasonably robust to specification of the smoothing parameters in the MRF model. The actual values used for the simulation results shown in Figure 2 were σ2 = 0.1, , , and , with the values kept the same for all metabolites, m. The increased strength of a priori smoothness in GM over WM (i.e. compared with ) is required to balance the reduced connectedness amongst GM neighbors as compared with WM (i.e., because GM consists of the relatively thin surface of the cortex). The absolute value of σ2 does not directly influence the posterior estimation of the metabolite maps; only the relative magnitude of σ2 compared with the prior smoothing parameters is important. This lack of identifiability for the combined set of σ2, , , and can be seen by examination of the M-step of the EM algorithm in Eq. [8].

The quality of the K-Bayes reconstruction after suitable convergence of the algorithm was compared to that for the (spatially) zero-filled discrete Fourier transform (zDFT). The zDFT reconstruction was obtained by first performing a spatial DFT for each timepoint's image, leading to a time-series of images in image space. Subsequently, a least-squares time-domain fitting procedure was applied at each voxel to provide the metabolite amplitude estimates. The model fitted by least squares was the same model used to simulate the data, i.e., the sum of a set of exponentially decaying sinusoids. The metabolite amplitudes were the unknown parameters to be estimated and all other parameters were fixed to those used in the simulation. Zero-filling in the spatial dimension increased the spatial resolution of the DFT-based reconstruction to that of the gold standard high-resolution truth (i.e. the true intensity maps used to simulate the data) and the K-Bayes reconstruction. The use of consistent resolution permitted direct comparison of the different reconstruction methods across voxels with respect to the gold standard. We further examined bicubic spline interpolated DFT maps (sDFT) to determine whether the choice of interpolation scheme might be important. Comparisons with the gold standard high-resolution truth were made in terms of i) visual examinations of the reconstructed maps; ii) the average bias in each of GM, WM, and the hotspots; iii) the root mean square error (RMSE) across all tissue and in only the hotspots. Bias in this context is defined as and RMSE as , where y is the gold standard, x is the reconstructed image, and i indexes over the set of voxels for which the metric is to be evaluated.

Figure 2 shows the reconstructions for the k-space-time simulations. The maps consist of: Left, the truth (gold standard), i.e. the three original 128×128 maps for each of three metabolites; Center, the corresponding zDFT reconstructions; and Right, the K-Bayes reconstructions. There is considerable visual improvement in each of the K-Bayes reconstructions compared with zDFT. The sDFT reconstruction is very similar to the zDFT reconstruction and is therefore not shown. The K-Bayes reconstructions have increased spatial definition compared with zDFT. Furthermore, the zDFT reconstructed maps contain Gibbs ringing not visible in the K-Bayes ones. K-Bayes appears to preserve the hotspots similarly to the zDFT reconstruction, apparently signaling that in this example K-Bayes is as robust as zDFT when detecting metabolite level changes that are not defined by tissue structure boundaries.

The qualitative visual improvements are verified numerically in Table 1, where K-Bayes consistently does better than zDFT and sDFT; the two DFT-based schemes led to very similar results, but sDFT did slightly worse across all metrics than zDFT. Across the three metabolites, GM and WM bias for K-Bayes was always less than 6% of that for the DFT-based reconstructions, and RMSE for K-Bayes was always less than 50% of that for either DFT approach. Perhaps surprisingly, even in the hotspot we see that K-Bayes has less than 35% of the bias of the DFT-based reconstructions and less than 50% of the RMSE. Although K-Bayes imposes smoothness on the high-resolution reconstruction it does so with guidance from the structural prior. In contrast, the interpolation imposed on the DFT-based reconstructions implies an arbitrary level smoothness that ignores both structural information and the noise in the original signal (which is also incorporated into the interpolation).

Table 1.

Statistical comparison of the reconstruction methods for the simulated MRSI data reconstructions in terms of bias and RMSE. The first column gives the metric and the second column subsets this by metabolite. The final three columns respectively give the zDFT, sDFT (spline-interpolated DFT) and K-Bayes values of the metric-metabolite pair. K-Bayes consistently provided the smallest bias and RMSE.

| Metric | Metabolite | zDFT | sDFT | K-Bayes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM Bias | NAA | −0.657 | −0.716 | −0.026 |

| Cr | −0.235 | −0.247 | −0.008 | |

| Cho | −0.239 | −0.272 | −0.014 | |

| WM Bias | NAA | −0.345 | −0.367 | −0.014 |

| Cr | −0.124 | −0.128 | −0.004 | |

| Cho | −0.125 | −0.138 | −0.007 | |

| RMSE | NAA | 0.262 | 0.290 | 0.097 |

| Cr | 0.088 | 0.092 | 0.024 | |

| Cho | 0.105 | 0.123 | 0.048 | |

| Hotspot Bias | NAA | −0.305 | −0.340 | −0.071 |

| Cho | −0.126 | −0.160 | −0.042 | |

| Hotspot RMSE | NAA | 0.310 | 0.353 | 0.095 |

| Cho | 0.129 | 0.172 | 0.053 |

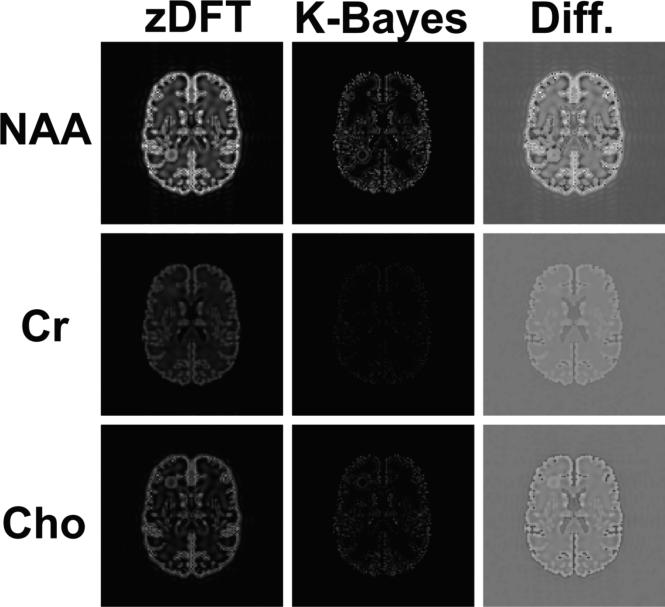

Figure 3 displays maps of the absolute residuals from the truth for each of the three metabolites NAA, Cr and Cho. The first two columns display the absolute zDFT and absolute K-Bayes residuals, respectively. These absolute residual maps are all constrained to be on the same scale. It is clear that for all metabolites K-Bayes has (on average) reduced absolute residuals compared with zDFT. This reduction in average intensity simply reflects the overall reduction in RMSE expressed in Table 1. The third column shows the zDFT minus K-Bayes difference (Diff.) in absolute residuals. The greatest reductions in residual error are seen as the brightest voxels, and they primarily occur in GM cortical regions and the WM hotspot. zDFT does a little better than K-Bayes for a small proportion (~10%) of voxels in the brain. These are shown as the darkest voxels in the Diff. map, typically close to the GM boundary in WM. The likely cause of the reduced accuracy of K-Bayes in these voxels is the effect of the cross-tissue-type boundary smoothing/variance parameter ; although zDFT also smoothes across the boundary, it is doing so based on underestimated GM intensities and therefore the nearby WM intensities are less elevated. (It is noted earlier that the original spatial smoothing of the simulated data was applied in a highly localized fashion.)

Figure 3.

Maps displaying the absolute values of residuals (relative to the truth) for the three metabolites NAA, Cr and Cho. Each row corresponds to a single metabolite and the columns correspond to the absolute zDFT residuals, absolute K-Bayes residuals and the difference between the absolute zDFT and absolute K-Bayes residuals (Diff.), respectively. The absolute residual maps in the first two columns are all constrained to the same intensity range as are the difference maps. K-Bayes has (on average) reduced intensity absolute residual maps compared with zDFT (reflecting overall reduction in RMSE). The greatest reductions in residual error occur in gray matter cortical regions.

A. Sensitivity to varying hotspot size

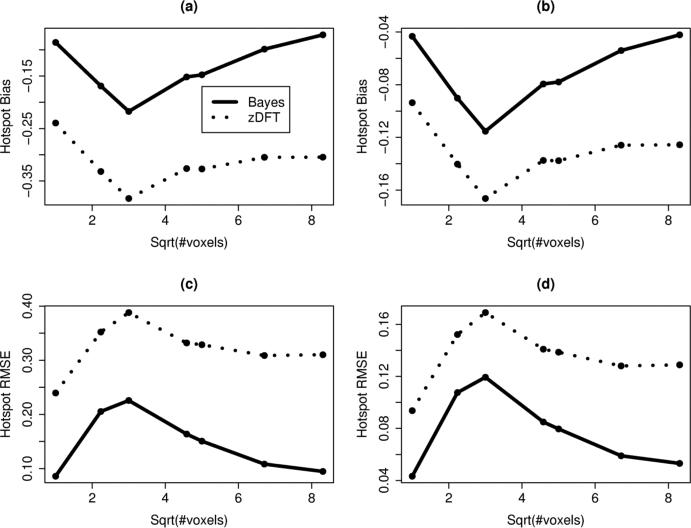

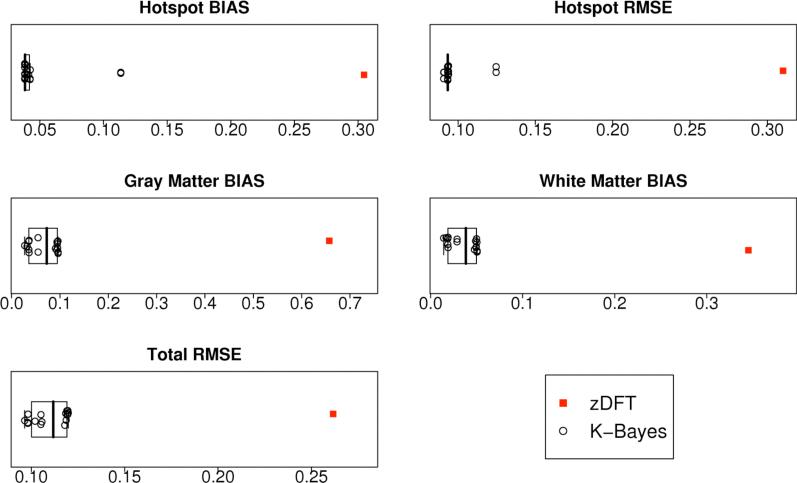

To determine the extent of K-Bayes’ capability for providing gains over zDFT for highly localized anomalies we repeated the reconstruction procedure and performed comparisons for a range of hotspot sizes (not surprisingly the metrics did not vary much outside of the hotspot). Figure 4 displays plots of Bias and RMSE for zDFT and K-Bayes across the varying hotspot sizes (in terms of the square root of the number of voxels contained in the hotspot) for both the NAA and Cho hotspots. K-Bayes produced highly consistent improvements (reduced magnitude Bias and RMSE) over zDFT across hotpot sizes.

Figure 4.

Plots of hotspot Bias and RMSE for zDFT and K-Bayes across varying hotspot sizes represented by the square root of the number of voxels contained in the hotspot. The hotspots were defined by including all neighboring voxels to the center voxel within a certain radius. The panels display (a) NAA Bias; (b) Cho Bias; (c) NAA RMSE; (d) Cho RMSE. Points are at values where the hotpot included voxels up to that distance from the center. K-Bayes provided consistent improvements over zDFT across all hotspot sizes in terms of reduced hotspot Bias magnitude and RMSE irrespective of hotspot size.

B. Simulated data reconstruction sensitivity to anatomic parameter specification

To determine the sensitivity of the K-Bayes reconstruction to the parameters of the anatomic distribution we performed reconstructions of NAA maps for 16 sets of parameters (hotspot radius as in original simulation). These parameter sets covered the ranges , and : thus covering two orders of magnitude in each parameter. Figure 5 graphically summarizes the statistical metrics for the associated K-Bayes and zDFT fits. The first thing to note is that no matter which set of anatomic parameters was chosen, K-Bayes performed much better than zDFT in all metrics. Furthermore all K-Bayes reconstructions are tightly clustered relative to the zDFT value for all metrics (with just a couple of exceptions for the hotspot metrics). That is, despite large shifts in the parameters, the reconstructed images had very similar properties in all cases. To show that this relatively stable solution with respect to the parameters provides an appropriate balance between the accurate reconstruction of global effects, small focal effects, and noise removal, we must examine the individual box plots more closely. We note that there is consistently very tight clustering of the K-Bayes reconstructions in the non-hotspot metrics. For the hotspot metrics we see two exceptions. One set of parameters that leads to an outlier (lowest a priori smoothness level) only increases the RMSE. In these cases the hotspot is flattened by too strong smoothing parameters causing increased bias and RMSE simultaneously (all the error is to one side of the truth). Nonetheless, even these most limited of K-Bayes reconstructions still have greatly improved hotspot bias and RMSE compared with zDFT.

Figure 5.

Boxplots of statistical metrics for zDFT reconstruction and 16 K-Bayes NAA reconstructions with differing anatomical parameter sets. zDFT is always the single point to the right (i.e. the worst score).

This sensitivity analysis indicates that K-Bayes is robust to a wide range of anatomic parameter sets and hence that the optimal balance between the anatomic information and the k-space-time data is well defined by the two data sources and not substantially influenced by any particular choice of parameter set.

Overall, these simulation results generate a very encouraging assessment of the potential gains afforded by K-Bayes in the reconstruction of MRSI datasets. However, they do provide close to an upper bound on the gains because the datasets are generated based on the K-Bayes model. That is, the signal model used is from the likelihood, and the metabolite maps are generated from the structural information (albeit with added blurring and hotspots). Inaccuracies in the signal model will equally propagate into errors for DFT-based reconstructions as well as K-Bayes. The potential realization of the relative gains of K-Bayes for real data reconstruction is therefore bounded by the extent to which differentials in metabolite levels respect tissue boundaries. Despite this limitation, some gains are made by K-Bayes in the simulation study even when metabolite differentials do not match the tissue boundaries, i.e. in the hotspot.

IV. Spin-echo data

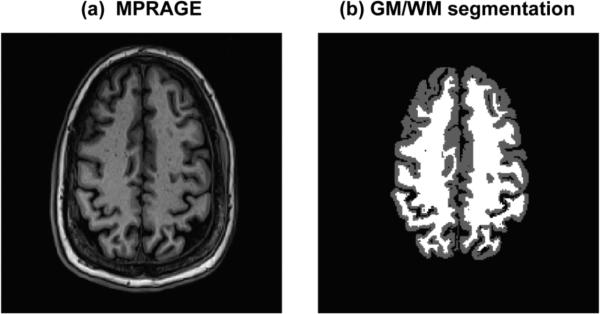

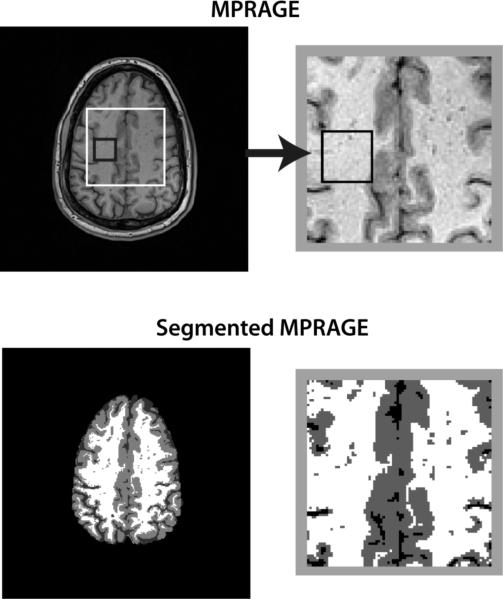

A spin-echo MRSI dataset from a male healthy volunteer, age 42 years, was reconstructed using K-Bayes and zDFT. The dataset was acquired at 3T with TR/TE = 1400/70ms, a 36×36 k-space matrix and a 256×256mm field-of-view (FOV). A corresponding GM/WM/CSF segmented magnetization prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo (MPRAGE) scan with nominal voxel size of 1×1×1.5mm across a 256×256mm FOV served as the structural information for K-Bayes. Each k-space-time-series consisted of 512 points with a sampling interval of 0.649ms, i.e., spectral bandwidth of 1540Hz. Figure 6 displays the structural MPRAGE scan and corresponding segmented map.

Figure 6.

Structural view of spin-echo data slice: (a) MPRAGE structural scan (b) GM/WM segmented version of MPRAGE.

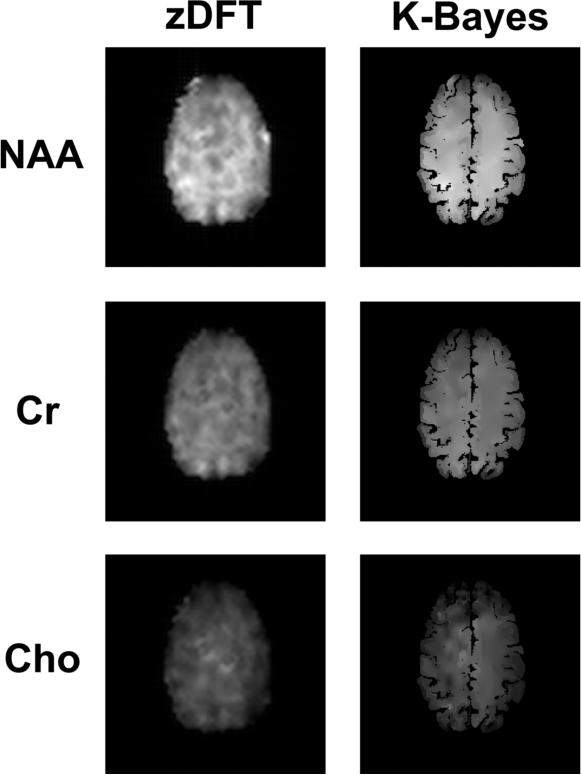

The data were initially processed using the SITools spectral analysis software [38]. Using the signal model of Young et al. [4] and Soher et al. [5], metabolite, residual water, and lipid signals were identified in all voxels and removed from all spectra while maintaining metabolite signals through the use of a singular value decomposition (SVD) based fitting algorithm. Residual signals left in most spectra outside the range of the predominant metabolites (1.9 to 3.9 PPM) appeared close to white noise. This ‘metabolite-only’ dataset was 1) DFT'd back into k-space-time for use in K-Bayes and 2) fitted using the SITools-FITT module to create NAA, Cr, and Cho metabolite maps. As part of the SITools-FITT, small baseline signal contributions due to macromolecular peaks in the metabolite region were identified and fitted. Metabolite maps were sinc interpolated to 256×256mm to match the voxel size of the MPRAGE acquisition and K-Bayes reconstruction. The spatially zero-filled frequency, phase, Lorentzian, and Gaussian decay estimates plus fitted macromolecular baseline signals were input into K-Bayes as fixed parameters. The zDFT estimates of the three metabolite signals (NAA, Cr, Cho) were used as starting maps for K-Bayes. Parameters for the structural prior distribution were obtained by trial and error. However, we found through a robustness study (not shown) that reconstructions were quite robust to within an order of magnitude change in the prior parameters. This requires further verification on multiple datasets. If K-Bayes is to be applied in multi-subject studies, we advocate that a structured approach to parameter setting be taken, such as that described in Section III.

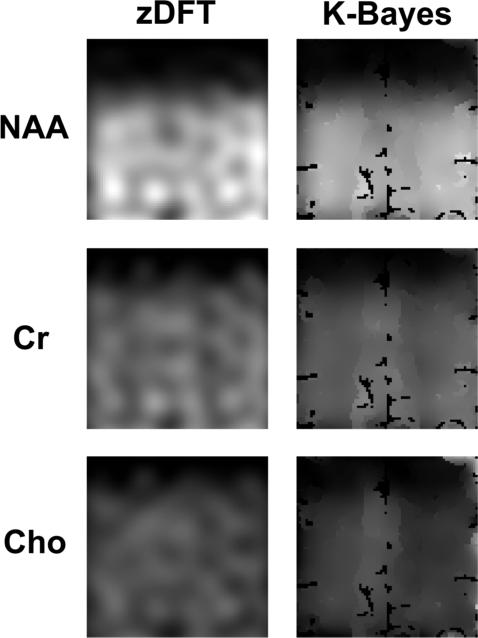

The reconstructed maps in Figure 7 show that K-Bayes produces additional detail (relative to zDFT reconstruction) unrelated to the underlying anatomy as well as showing variation clearly related to anatomy. These encouraging results suggest that K-Bayes is capable of finding a reasonable balance between the accurate reconstruction of global effects, small focal effects, and noise.

Figure 7.

Spin-echo metabolite map reconstructions: zDFT (left column) and K-Bayes (right column) reconstructions for NAA, Cr, and Cho.

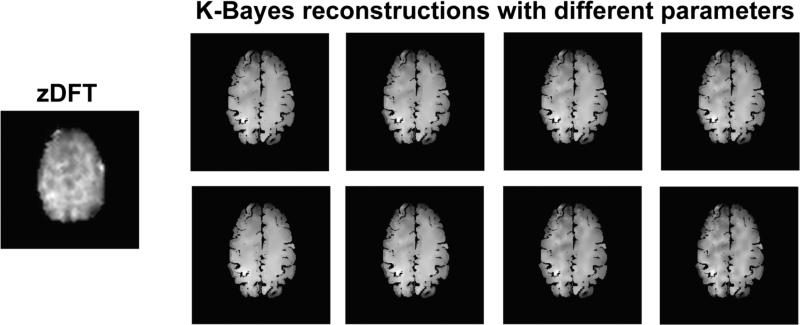

A. Sensitivity analysis of spin-echo data reconstructions to anatomic parameter settings

To determine the sensitivity of K-Bayes to the parameters of the anatomic distribution, we performed reconstructions for 8 sets of anatomic parameters. For the three parameters, these 8 sets covered the range , , . These ranges are all greater than an order of magnitude. Although the ranges appear different from those in the simulation, they are in fact quite similar in the relative magnitude of the parameters to the (square of the) range of the data.

The eight K-Bayes reconstructed NAA maps are shown in Figure 8, contrasted with the single zDFT reconstruction. (We show only figures since we lack a gold standard with which to assess statistical metrics.) Clearly, variation in K-Bayes reconstructions is small compared to the difference between them and the zDFT reconstruction, indicating that K-Bayes is robust to a wide range of anatomical distribution parameter sets. Thus the optimal way to balance anatomic and k-space-time data is well defined in the data sources themselves. More precisely, the location of the posterior maximum (the optimal reconstruction) does not vary greatly for a wide range of prior smoothing parameter values; despite large shifts in parameters, the image at the posterior maximum is quite similar in all cases.

Figure 8.

Left: zDFT reconstruction. Right: eight images corresponding to a range of K-Bayes reconstructions with different parameter settings. K-Bayes reconstructions are more similar to each other than to zDFT.

V. PRESS box data with single voxel spectroscopy validation

A proton resolved spectroscopy (PRESS) chemical shift imaging (CSI) (“PRESS box”) dataset was acquired from a single male healthy volunteer, age 40. The PRESS box covered a region of 80×80×15mm, acquired as a 32×32 k-space matrix over a 240×240mm FOV. A corresponding GM/WM/CSF segmented structural MRI (MPRAGE) with voxel dimensions 1×1×1.5mm and 256×256mm FOV was used as the structural information for K-Bayes. Each k-space-time-series consisted of 1024 points with a sampling interval of 0.649ms, i.e., spectral bandwidth of 1540Hz. Figure 9 displays the structural scan with a white box outlining the PRESS box region.

Figure 9.

Spatial location of PRESS-CSI data: Top left: MPRAGE structural scan with PRESS box outlined in white. Top right: PRESS box zoomed. Bottom left: segmented MPRAGE. Bottom right: zoomed version of segmented PRESS box.

SITools-4DFT and SITools-FITT were employed for conventional spectral DFT and fitting of the data [38] using the signal model of Young et al. [4] and Soher et al. [5]. The complex baseline signal at each voxel was fit using a spline model with knots placed 30 frequency points apart in the spectrum. There was considerable residual water signal in the dataset, 10-100 times the area of the NAA peak, despite applying water suppression during signal acquisition. The residual water signal was typically observed to be Lorentzian shaped, but in many voxels was significantly asymmetric or had an actual shoulder. We determined experimentally that the residual water signal could be fit with three extra frequencies located at 4.6, 4.7, and 4.8ppm sufficiently well to provide, along with the spline baseline, reasonable removal of the residual water signals. After water and baseline signal removal, the residuals left in most spectra (outside the range of the predominant metabolites) appeared close to white noise. The resulting integrated spectral maps for each metabolite and frequency components of water signal were subsequently zero-filled to 240×240mm in the k-space dimensions to match the voxel size of the MPRAGE acquisition.

ZDFT reconstructed maps of the B0, phase, Lorentzian and Gaussian decay map estimates (plus the fitted macromolecular baseline signals) from SITools-FITT were used as fixed quantities in K-Bayes. The corresponding zDFT map estimates from SITools-FITT of the three metabolite signals (NAA, Cr, Cho), as well as the three frequency components of water signal, were used as starting maps for K-Bayes. Parameters for the structural prior distribution were obtained by trial and error. There appeared to be more sensitivity in the reconstruction to the specific choice of parameter values for the PRESS box reconstruction. This is possibly due to the limitations of using K-Bayes with this particular PRESS box dataset, as discussed below).

Figure 10 displays zDFT and K-Bayes reconstructed maps of NAA, Cr, and Cho. Qualitatively, K-Bayes produces improved definition and reduced noise in the reconstructed metabolite maps. Although these PRESS results demonstrate feasibility, there are limitations. The PRESS box dataset is far from the ideal form for utilizing K-Bayes; there was a sharp drop-off at the top of the PRESS box that led to bias in the neighboring homogeneous tissue regions that do contain signal affected by the MRF prior (i.e., biased towards zero in regions of high signal). Note that the conservative approach was taken by assuming that the prior PRESS box segmented tissue map corresponded to the a priori defined PRESS box. This approach is in contrast to trying to determine the PRESS box after looking at the data. Further evidence of the inaccuracy in spatial localization of the PRESS box can be seen in the edge-effects of the upper right corner of the K-Bayes reconstructed Cho map: any signal outside the demarked PRESS box is likely being “squeezed into the edge of the box”.

Figure 10.

PRESS-CSI metabolite map reconstructions: zDFT (left column) and K-Bayes (right column) reconstructions for NAA, Cr, and Cho.

A further limitation of both real MRSI data studies was that we only considered a single-slice 2D segmented structural MRI as prior information (the middle slice). Since both datasets consisted of 15mm thick slices, there would be variation in tissue composition along the slice in the z -direction. Taking z -direction variability into account via 3D spatial modeling would likely further improve K-Bayes reconstruction quality. This is discussed further in the next section.

VI. Summary and Discussion

A. Summary

Although MRSI provides useful regional information on metabolite levels in the brain, the results of conventional reconstruction methods are limited by the low spatial resolution inherent in the data acquisition imposed by typical signal to noise ratio considerations. K-Bayes can help quantify regional metabolite levels with much greater precision than that attainable through DFT/spectral-integration-based reconstruction. The increased precision is due to the enhanced spatial specification obtained by incorporating segmented structural MRI prior information, and the use of a full signal model for the k-space-time data. The increased precision of estimated metabolite levels could considerably benefit clinical studies that quantify regional differences in metabolite concentrations between different subject populations (e.g. patients with Alzheimer's disease versus healthy controls). The extra accuracy obtained by K-Bayes could be crucial in detecting real differences between disease states. Furthermore, the use of K-Bayes could expand to non-brain applications of MRSI. All that is required to implement K-Bayes is a high-resolution structural segmentation of the anatomy along with a physiologically reasonable model of the distribution of metabolites concentrations within and between structurally homogeneous regions.

B. On advance estimation of maps using FITT

In the current implementation of K-Bayes the maps Ta(x,y,z), Tb(x,y,z), ϕa(x,y,z) and B0(x,y,z) are estimated in advance using SITools-FITT, raising a question as to how use of these zDFT results might be affecting the K-Bayes results through error propagation. The degree of this potential error propagation would depend on the true relative smoothness of each map (i.e. the smoothness of the actual underlying process). Our assumption is that these maps vary more slowly in practice than the metabolite maps do, especially at tissue boundaries and in particular at brain edges. This seems reasonable. K-Bayes does provide visual improvements in the metabolite maps. Since the errors in Ta(x,y,z), Tb(x,y,z), ϕa(x,y,z) and B0(x,y,z) are common to both K-Bayes and zDFT reconstruction, one assumes that the improvements derive from K-Bayes despite the limitations of the propagated error. In the future, if estimation of these parameter maps becomes feasible as extra estimation steps within the K-Bayes process (via planned algorithmic enhancements) we expect further improvements in metabolite quantification from K-Bayes.

C. On the variation of T2 with respect to metabolite peaks

We know that the terms Ta(x,y,z) and Tb(x,y,z) can vary as a function of metabolite, and this may have important consequences, particularly in short-TE applications where spectral peaks with a wide range of T2 values are present. However, our choice to ignore it in the model presented deserves justification.

Currently, Ta(x,y,z) and Tb(x,y,z) are estimated in advance via SITools-FITT. There is in fact an undocumented provision in the SITools-FITT software package to fit different Ta(x,y,z) and Tb(x,y,z) for distinct metabolite peaks. If these maps are obtained, then very little additional effort or computation is required to extend the K-Bayes model to incorporate the additional maps (other than a little extra memory requirement). However, we opted not to utilize this option because current SNR values for spectroscopic imaging data for coupled metabolites (those for which this provision would matter) make it extremely difficult to quantify such subtle differences. In fact, other effects, such as the chemical shift effect and other spatial effects due to the presence of gradients, currently dominate variations in T2 for in vivo data [39, 40]. In the case of strongly coupled metabolites, properly labeling metabolite peaks in terms of multiplet group is a difficult theoretical problem, in particular for strongly coupled metabolites, while separately fitting Ta(x,y,z) and Tb(x,y,z) for every peak in every voxel would lead to an infeasible spectral fitting problem. Therefore, some work remains in terms of devising an optimal strategy for including Ta(x,y,z) and Tb(x,y,z) variation over peaks for spectral fitting. One advantage to generation of prior spectral information via phantom measurement is that it might principle provide information on such variations [41] in which case this information could be incorporated into a K-Bayes analysis. But in practice any such differences are currently too subtle to detect and the most significant differences would be expected to arise in the case in-vivo data for which phantom generated prior information provides no advantage.

In the long run we aim to incorporate estimation of Ta(x,y,z) and Tb(x,y,z) within the K-Bayes framework as maps to be estimated via additional M-steps (at the cost of considerable extra computational complexity). As part of this process we will consider the extension to include separate maps for each line or/and multiplet. To ensure a tractable solution to this extension, additional prior assumptions may be required to relate maps of different metabolite peaks to each other.

D. On the issue of MRI versus MRSI slice thickness

In our real data examples (spin-echo and PRESS) the slice thickness of the MRSI was much thicker than that of the corresponding structural MRI slice used as prior information. The 15mm slice will contain partial voluming effects since the tissue structure will not be perfectly homogeneous across the MRSI slice. This is a notable limitation of the real data examples. The complete solution is to extend application of K-Bayes to full 3D-space datasets. Considerable computational enhancement will be required in order to make this practical.

In our spin-echo and PRESS data examples, we selected the central segmented structural MRI slice to define the anatomical prior information in the simplified 2D space case rather than the many other reasonable choices: e.g. defining a prior over blurred boundaries or taking the voxel-wise tissue class mode across all structural MRI slices. We chose the central slice partly for simplicity, partly because it represents the tissue class at the point of highest excitation in the slice, and finally because the central anatomic image represents a true slice through the brain, which is helpful for visualization purposes.

E. Future applicability

Two methodological issues should be addressed before K-Bayes can achieve more general applicability. The first is that the method requires good co-registration of segmented structural MRI with MRSI data. Similarly, poor quality segmentation can reduce the benefits of K-Bayes. Poor segmentation again corresponds to poor prior information, though unless the segmentation has high mis-classification rates, the problems associated with low-resolution MRSI data will be worse than any error introduced by inaccurate segmentation. The second (and primary) issue encountered with using K-Bayes is computational time. The 2D reconstruction examples were performed on a Dell Precision 370 desktop computer running RedHat Enterprise Linux 4.0 on a single thread of an Intel Xeon 2.33GHz processor. These were programmed in C and compiled with a gcc compiler. Reconstructions reached reasonable convergence in a day. Although it is impractical to achieve full convergence to the level of machine tolerance, the statistical metrics of the reconstructions did not change significantly after this time. Parallelization similar to that used in [10] will help to significantly reduce computational time. Because the algorithm is highly parallelizable, a large reduction in computational time can be achieved by distributing the processing and spreading the memory load amongst multiple processors. The benefit of parallelization will potentially be greater than linear speed up with the number of processors, because the significant memory burden will be distributed as well. Computational improvement of this level would potentially allow for K-Bayes to be used as a routine approach for obtaining high-resolution and accurate metabolite maps. Given the decreasing prices for multiprocessor supercomputers and random access memory (RAM), there is great potential for K-Bayes to become widely applicable in clinical settings.

VII. Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Society for Imaging Informatics in Medicine (SIIM) research grant; NIH grants R01 NS41946, P41 RR023953, R01 EB008387. We acknowledge the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center where part of this work was performed.

Appendix

Derivation of K-Bayes E- and M-steps

E-step

The E-step update applied to each missing data point z(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m) is determined by its expectation given the data and the set of metabolite maps A: E[z(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m)|d,A] = E[z(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m)|d(kx,ky,w,t),A], where z(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m) is only defined when the r -th slice of the structural MRI is contained within the w -th slice of the MRSI. Note that the value of r effectively defines that for w though we keep w as a parameter of z for notational clarity.

Bayes’ Theorem gives

Now,

where ν = cPQ

Therefore,

Completing the square, this leads to

Therefore, π(z(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m)|d(kx,ky,w,t),A) is complex Gaussian with mean

and the j th E-step update for z(kx,ky,p,q,r,w,t,m) is,

M-step

To generate the M-step, the log-posterior distribution, log (π(Am(p,q,r)|z,Ȃm(p,q,r)) is maximized with respect to , where Ȃm(p,q,r) corresponds to all elements of A other than Am(p,q,r).

Differentiating the log-posterior distribution with respect to Am(p,q,r) and setting equal to zero gives

| [10] |

where δ(p,q,r) is the set of neighboring voxels to voxel (p,q,r).

Rearranging [10] in terms of Am(p,q,r), leads to

| [11] |

Differentiating [10] again with respect to Am(p,q,r) we obtain that the second differential of the log-posterior is

| [12] |

The inequality of Equation [12] confirms that the solution given by [11] is a local maximum and therefore the j th M-step update for Am(p,q,r) is:

| [13] |

References

- 1.Brown TR, Kincaid BM, Ugurbil K. NMR chemical shift imaging in three dimensions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1982;79:3523–3526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.11.3523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maudsley AA, Hilal SK, Perman WH, Simon HE. Spatially resolved high resolution spectroscopy by four-dimensional NMR. J Magn Reson. 1983;51:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young K, Govindaraju V, Soher BJ, Maudsley AA. Automated spectral analysis I: formation of a priori information by spectral simulation. Magn Reson Med. 1998 Dec;40:812–5. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young K, Soher BJ, Maudsley AA. Automated spectral analysis II: application of wavelet shrinkage for characterization of non-parameterized signals. Magn Reson Med. 1998 Dec;40:816–21. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soher BJ, Young K, Govindaraju V, Maudsley AA. Automated spectral analysis III: application to in vivo proton MR spectroscopy and spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1998 Dec;40:822–31. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Beer R, van den Boogaart A, van Ormondt D, Pijnappel WW, den Hollander JA, Marien AJ, Luyten PR. Application of time-domain fitting in the quantification of in vivo 1H spectroscopic imaging data sets. NMR Biomed. 1992;5:171–178. doi: 10.1002/nbm.1940050403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang Z-P, Lauterbur PC, IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society . Principles of magnetic resonance imaging : a signal processing perspective. SPIE Optical Engineering Press; IEEE Press; Bellingham, Wash. New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hurn MA, Mardia KV, Hainsworth TJ, Kirkbridge J, Berry E. Bayesian Fused Classification of Medical Images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1996;15:850–858. doi: 10.1109/42.544502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller IM, Schaewe TJ, Cohen SB, Ackerman JJH. Model-Based Maximum-Likelihood Estimation for Phase- and Frequency-Encoded Magnetic-Resonance-Imaging Data. Journal of Magnetic Resonance, Series B. 1995;107:10–221. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schaewe TJ, Miller IM. Parallel Algorithms for Maximum A Posteriori Estimation of Spin Density and Spin-spin Decay in Magnetic Resonance Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1995:362–373. doi: 10.1109/42.387717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denney TS, Jr., Reeves SJ. Bayesian image reconstruction from Fourier-domain samples using prior edge information. Journal of Electronic Imaging. 2005;14:043009, 1–11. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ouyang X, Wong WH, Johnson VE, Hu X, Chen C-T. Incorporation of Correlated Structural Images in PET Image Reconstruction. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1994;13:627–640. doi: 10.1109/42.363105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowsher JE, Johnson VE, Turkington TG, Jaszczak RJ, Floyd CE, Jr., Coleman RE. Bayesian Reconstruction and Use of Anatomical A Priori Information for Emission Tomography. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1996;15:673–686. doi: 10.1109/42.538945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sastry S, Carson RE. Multimodality Bayesian Algorithm for Image Reconstruction in Positron Emission Tomography: A Tissue Composition Model. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1997;16:750–761. doi: 10.1109/42.650872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu X, Levin DN, Lauterbur PC, Spraggins T. SLIM: spectral localization by imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1988;8:314–22. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910080308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Von Kienlin M, Mejia R. Spectral localization with optimal pointspread function. Journal of magnetic resonance. 1991;94:268–287. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang ZP, Lauterbur PC. A generalized series approach to MR spectroscopic imaging. Medical Imaging, IEEE Transactions on. 1991;10:132–137. doi: 10.1109/42.79470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang ZP, Lauterbur PC. An efficient method for dynamic magnetic resonance imaging. Medical Imaging, IEEE Transactions on. 1994;13:677–686. doi: 10.1109/42.363100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jacob M, Zhu X, Ebel A, Schuff N, Liang ZP. Improved Model-Based Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopic Imaging. Medical Imaging, IEEE Transactions on. 2007;26:1305–1318. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.898583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bao Y, Maudsley AA. Improved Reconstruction for MR Spectroscopic Imaging. Medical Imaging, IEEE Transactions on. 2007;26:686–695. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2007.895482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haldar JP, Hernando D, Song SK, Liang ZP. Anatomically constrained reconstruction from noisy data. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2008;59:810. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kornak J, Young K, Schuff N, Du A, Maudsley AA, Weiner MW. K-Bayes Reconstruction for Perfusion MRI I: Concepts and Application. Journal of Digital Imaging. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10278-009-9183-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kornak J, Young K. K-Bayes Reconstruction for Perfusion MRI II: Modeling and Technical Development. Journal of Digital Imaging. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s10278-009-9184-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Geman S, German D. Stochastic Relaxation, Gibbs Distributions, and the Bayesian Restoration of Images. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence. 1984;6:721–741. doi: 10.1109/tpami.1984.4767596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besag JE. Towards Bayesian Image Analysis. Journal of Applied Statistics. 1989;16:395–407. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winkler G. Image Analysis, Random Fields, and Markov Chain Monte Carlo Methods: A Mathematical Introduction. 2nd ed. Springer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maudsley A, Domenig C, Govind V, Darkazanli A, Studholme C, Arheart K, Bloomer C. Mapping of brain metabolite distributions by volumetric proton MR spectroscopic imaging (MRSI) Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2009;61 doi: 10.1002/mrm.21875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Besag JE. Spatial Interaction and The Statistical Analysis of Lattice Systems (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1974;36:192–236. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dempster AP, Laird NM, Rubin DB. Maximum Likelihood From Incomplete Data Via the EM Algorithm (with discussion) Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B. 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ashburner J, Friston KJ. Multimodal Image Coregistration and Partitioning - A Unified Framework. NeuroImage. 1997;6:209–217. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1997.0290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation-maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001 Jan;20:45–57. doi: 10.1109/42.906424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Besag JE. Statistical Analysis of Non-lattice Data. The Statistician. 1975;24:179–195. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kunsch HR. Intrinsic Autoregressions and Related Models on the Two-dimensional Lattice. Biometrika. 1987;74:517–524. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Besag JE, Kooperberg C. On Conditional and Intrinsic Autoregressions. Biometrika. 1995;82:733–746. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green PJ. Bayesian Reconstructions From Emission Tomography Data Using A Modified EM Algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging. 1990;9:84–93. doi: 10.1109/42.52985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen L. Time-frequency analysis: theory and applications. 1995.

- 37.Cocosco CA, Kollokian V, Kwan RK-S, Evans AC. BrainWeb: Online Interface to a 3D MRI Simulated Brain Database. Proceedings of 3rd International Conference on Functional Mapping of the Human Brain; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maudsley AA, Lin E, Weiner MW. Spectroscopic imaging display and analysis. Magn Reson Imaging. 1992;10:471–85. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(92)90520-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaiser LG, Young K, Matson GB. Elimination of spatial interference in PRESS-localized editing spectroscopy. Magnetic resonance in medicine: official journal of the Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine/Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2007;58:813. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kaiser LG, Young K, Matson GB. Numerical simulations of localized high field 1H MR spectroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 2008;195:67–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jmr.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Provencher S. Automatic quantitation of localized in vivo 1H spectra with LCModel. NMR in Biomedicine. 2001;14 doi: 10.1002/nbm.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]