Abstract

Prenatal ethanol exposure causes deficits in hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning. At present, there are no clinically effective pharmacotherapeutic interventions for these deficits. In this study, we examined whether the cognition-enhancing agent 4-(2-{2-[(2R)-2-methylpyrrolidinyl]ethyl}-benzofuran-5-yl) benzonitrile (ABT-239), a histamine H3 receptor antagonist, could ameliorate fetal ethanol-induced long-term potentiation (LTP) deficits. Long-Evans rat dams consumed a mean of 2.82 g/kg ethanol during a 4-h period each day. This voluntary drinking pattern produced a mean peak serum ethanol level of 84 mg/dl. Maternal weight gain, offspring litter size, and birth weights were not different between ethanol-consuming and control groups. A stimulating electrode was implanted in the entorhinal cortical perforant path, and a recording electrode was implanted in the dorsal dentate gyrus of urethane-anesthetized adult male offspring. Baseline input/output responses were not affected either by prenatal ethanol exposure or by 1 mg/kg ABT-239 administered 2 h before data collection. No differences were observed between prenatal treatment groups when a 10-tetanus train protocol was used to elicit LTP. However, LTP elicited by 3 tetanizing trains was markedly impaired by prenatal ethanol exposure compared with control. This fetal ethanol-induced LTP deficit was reversed by ABT-239. In contrast, ABT-239 did not enhance LTP in control offspring using the 3-tetanus train protocol. These results suggest that histamine H3 receptor antagonists may have utility for treating fetal ethanol-associated synaptic plasticity and learning deficits. Furthermore, the differential effect of ABT-239 in fetal alcohol offspring compared with controls raises questions about the impact of fetal ethanol exposure on histaminergic modulation of excitatory neurotransmission in affected offspring.

Heavy or binge patterns of drinking during pregnancy can cause profound morphological and neurological aberrations in offspring called fetal alcohol syndrome (Lemoine et al., 1968; Jones and Smith, 1973). However, increasing evidence indicates that even moderate drinking during pregnancy can cause subtle, long-term behavioral and cognitive impairments in the absence of the birth defects associated with fetal alcohol syndrome (for review, see Kodituwakku, 2009). These behavioral deficits may not become apparent until the educational years (Streissguth et al., 1990; Jacobson et al., 1998; Hamilton et al., 2003) and may increase in severity as the child matures (Streissguth et al., 1994).

The mechanisms by which prenatal ethanol exposure causes long-lasting impairments in learning and memory are not well understood. Our previous studies of Sprague-Dawley rats using a 5% ethanol liquid diet paradigm as a model of moderate drinking during pregnancy indicated that prenatal ethanol-exposed offspring exhibit performance deficits on increasingly challenging memory tasks (Sutherland et al., 2000; Weeber et al., 2001). These memory impairments are, in part, linked to physiological alterations that diminish activity-dependent enhancement of synaptic neurotransmission in hippocampal formation of affected offspring (Sutherland et al., 1997; Savage et al., 1998). Furthermore, decreased positive allosteric modulation of dentate granule cell N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptors (Costa et al., 2000) and mGluR5 receptor-mediated potentiation of glutamate release from perforant path nerve terminals (Galindo et al., 2004) have been implicated as putative neurochemical mechanisms underlying fetal ethanol-induced deficits in synaptic plasticity and learning.

Presynaptic histamine H3 receptors mediate the inhibition of transmitter release of a number of central nervous system neurotransmitters including histamine (Arrang et al., 1983), serotonin, norepinephrine, dopamine (Schlicker et al., 1988, 1989, 1993), acetylcholine (Clapham and Kilpatrick, 1992), and glutamate (Brown and Reymann, 1996). Conversely, histamine H3 receptor antagonists enhance the release of acetylcholine, dopamine (Fox et al., 2005), and glutamate (A. El-Emawy and D. D. Savage, unpublished observations), whereas their impact on serotonin, norepinephrine, and GABA release have been less studied to date. The ability of H3 receptor antagonists to facilitate acetylcholine, dopamine, and glutamate release has generated considerable interest in their therapeutic potential for a variety of neurologic and psychiatric disorders, particularly diseases with attendant neurocognitive deficits. Indeed, H3 receptor antagonists enhance behavioral performance in a variety of rodent learning paradigms (Fox et al., 2003, 2005; Foley et al., 2009) and reversed contextual fear conditioning and spatial navigation deficits in fetal ethanol-exposed Long-Evans rats (Savage et al., 2010).

The present study had two experimental objectives. First, we wanted to determine whether the LTP deficits observed previously in Sprague-Dawley rats whose mothers consumed a 5% ethanol liquid diet (Sutherland et al., 1997) also occur in Long-Evans rat offspring whose mothers voluntarily drank 5% ethanol in saccharin water. Long-Evans rats were selected for study based on the preponderance of their use in learning and memory studies (Andrews, 1996). The voluntary drinking paradigm was selected because it has the dual advantage of not requiring multiple diet control groups to control for paired feeding of a liquid diet as well as for allaying concern that the consumption of liquid diets may be stressful (Rasmussen et al., 2000), a potential confounder in fetal alcohol exposure studies. The second study objective was to determine whether the cognition-enhancing agent 4-(2-{2-[(2R)-2-methylpyrrolidinyl]ethyl}-benzofuran-5-yl)benzonitrile (ABT-239), a nonimidazole antagonist of H3 histamine receptors (Esbenshade et al., 2005; Miller et al., 2008) that reverses learning deficits in a variety of models including our current fetal ethanol exposure paradigm (Savage et al., 2010), would also reverse fetal ethanol-induced deficits in dentate gyrus LTP. The pharmacologic rationale for selecting ABT-239 was based on prior observations, suggesting that prenatal ethanol exposure diminished activity-dependent potentiation of glutamate release in hippocampal slices (Savage et al., 1998). The 1 mg of ABT-239/kg dose was selected for our study based on prior observations that it was an optimal test dose for increasing acetylcholine release in vivo and enhancing performance in a variety of behavioral paradigms (Fox et al., 2005), including the reversal of fetal ethanol-induced deficits in contextual fear conditioning and spatial navigation (Savage et al., 2010). Given that histamine H3 receptor agonists inhibit glutamate release (Brown and Reymann, 1996), we predicted that the histamine H3 receptor antagonist ABT-239 would attenuate fetal ethanol-induced LTP deficits in the dentate gyrus.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

All reagents were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless indicated otherwise in parenthetical text.

Voluntary Drinking Paradigm.

All procedures involving the use of live rats were approved by the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Four-month-old Long-Evans rat breeders (Harlan Industries, Indianapolis, IN) were single-housed in plastic cages at 22°C and kept on a “reverse” 12-h dark/light schedule (lights on from 9:00 PM to 9:00 AM) with Harlan Teklad rodent chow and tap water ad libitum. After at least 1 week of acclimation to the animal facility, all female rats were provided 0.066% saccharin in tap water for 4 h each day from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM. The saccharin water contained 0% ethanol on the 1st and 2nd day, 2.5% ethanol (v/v) on the 3rd and 4th day, and 5% ethanol on the 5th day and thereafter. Daily 4-h consumption of ethanol was monitored for at least 2 weeks, and then the mean daily ethanol consumption was determined for each female. Females whose mean daily ethanol consumption was greater than 1 S.D. from the group mean were removed from the study. In general, fewer than 12% of females were removed in a given breeding round. The remainder of the females were assigned to either a saccharin control or 5% ethanol drinking group and matched such that the mean prepregnancy ethanol consumption by each group was similar. Subsequently, females were placed with proven male breeders until pregnant, as indicated by the presence of a vaginal plug. Female rats did not consume ethanol during the breeding procedure. Beginning on gestational day 1, rat dams were provided saccharin water containing either 0 or 5% ethanol for 4 h/day, from 10:00 AM to 2:00 PM. The volume of saccharin water provided to the control group was matched to the mean volume of saccharin water consumed by the ethanol group. Daily 4-h ethanol consumption was recorded for each dam. At birth, litters were culled to 10 pups each. Offspring were weaned at 28 days of age and group-housed, two males per cage, until used in the in vivo electrophysiology studies.

Maternal Serum Ethanol Levels.

A separate set of 12 rat dams was used to determine serum ethanol concentrations. These dams were run through the same voluntary drinking paradigm as described above, except that blood samples were collected at the end of the 4-h ethanol consumption episode on gestational days 15, 17, and 19. Each rat dam was briefly anesthetized with isoflurane and had 100 μl of whole blood collected from the tail vein. Samples were immediately mixed with 0.2 ml of 6.6% perchloric acid, frozen, and stored at −20°C until assayed. Serum ethanol standards were created by mixing rat whole blood from untreated rats with known amounts of ethanol ranging from 0 to 240 mg of ethanol/dl and then mixing 100-μl aliquots of each standard with perchloric acid and storing the standards frozen with the samples. Serum ethanol samples were assayed using a modification of the method of Lundquist et al. (1959).

In Vivo Electrophysiology.

Male adult rat offspring, 105 to 140 days of age and weighing 370 to 500 g were anesthetized with urethane (two injections of 0.75 g/kg, 30 min apart). A subset of control and fetal ethanol-exposed offspring received an intraperitoneal injection of 1 mg of ABT-239/kg dissolved in isotonic phosphate-buffered saline solution (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, 2 mM NaH2PO4, and a pH of 7.4.) 5 min after the first urethane injection (approximately 2 h before the 3-tetanus train protocol). Upon loss of the pedal reflex, a rat was placed into a stereotaxic frame (David Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA). Rectal temperature was closely monitored and maintained at 37.3°C using a temperature controller (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) throughout the entire surgical and recording procedure. The stereotaxic procedure was conducted as described previously (Sutherland et al., 1997). In brief, after the skull was exposed, five holes were drilled using a dental burr. Three self-tapping screws attached to stainless steel wires and gold Amphenol pins were inserted into the skull; two served as ground and reference signals for the recording circuit and one served as the return component of the stimulating circuit. Recording and stimulating Teflon-coated, stainless steel, unipolar electrodes (114 μm o.d.; A-M Systems, Carlsborg, WA) were implanted using bregma coordinates (recording electrode, anteroposterior −3.5 mm and mediolateral +1.8 mm; stimulating electrode, anteroposterior −8.1 mm and mediolateral +4.3 mm) (Paxinos and Watson, 1986). Electrodes were then connected to an isolated pulse stimulator (model 2100; A-M Systems) and to a differential a.c. amplifier (model 1800; A-M Systems). Recording signals were amplified (1000×), bandpass-filtered (0.1 Hz–10 kHz), and transferred to a personal computer via an analog-to-digital converter (model BNC-2090; National Instruments, Austin, TX). The electrodes were slowly inserted into the dentate gyrus (recording electrode: dorsoventral −3.8 mm from bregma) and entorhinal cortex (stimulating electrode, dorsoventral −4.0 mm from bregma). Responses to a guide stimulus (400-μA intensity) were monitored during the electrode descent process.

Once optimal positioning of electrodes and stable baseline responses were achieved, an input/output curve was generated, using current intensities ranging from 50 to 500 μA. The stimulus intensity sufficient to generate 40% of maximal population spike (PS) response (ES40), which averaged approximately 300 μA, was then used for high-frequency tetanization and subsequent test stimulus recordings. Animals failing to exhibit a PS of at least 4 mV with 500-μA stimulus intensity were removed from the study (n = 2). Synaptic potentiation was induced by either 3 or 10 trains of high-frequency stimulation (HFS) of 400 Hz over 25 ms with 30-s intertrain intervals. After tetanization, responses to the test stimulus were measured every 10 s over the next 60 min. To minimize random fluctuations, responses obtained over 1-min intervals (six consecutive responses) were averaged. The first ascending portion of each response curve was used to calculate the fast excitatory postsynaptic potential slope (fEPSP). Population spike amplitude was calculated, measuring the difference between the average of the first and second positive deflections to the negative peak.

Data Analysis.

For each rat, the baseline (pretetanus) responses over 10 min were averaged, the mean was normalized to 100%, and the post-tetanus response data were formed by the baseline average. Comparison of the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure after tetanus was performed using one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) on ranks followed by Dunnett's post hoc comparisons against baseline (100% value). Differences between treatments at discrete time points were examined using a two-tailed Student's t test. All statistical procedures were performed using SigmaPlot (version 11.0; Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA).

Results

Voluntary Drinking Paradigm.

A summary of the voluntary drinking paradigm data are presented in Table 1. Rat dams stably consumed an average of 2.82 ± 0.13 g of ethanol/kg b.wt. over the 4-h interval each day during pregnancy (approximately 16 ml of 5% ethanol in 0.066% saccharin water). This pattern and level of ethanol consumption produced a mean maternal serum ethanol concentration of 84.0 ± 5.5 mg/dl during the 3rd week of gestation. Ethanol consumption did not affect maternal weight gain during pregnancy, nor did it produce any significant differences in litter size or offspring birth weight or body weights at time of surgery (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Effects of daily 4-h consumption of 5% ethanol on female dams and their offspring

Data are means ± S.E.M. (group sample size).

| Saccharin Control | 5% Ethanol | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal weight gain during pregnancy (g increase in body weight from gestation days 1 through 21) | 127 ± 3 (44) | 121 ± 4 (51) |

| Daily 4-h consumption of 5% ethanol (g ethanol/dl serum, collected at the end of a 4-h drinking period) | N.A. (51) | 2.82 ± 0.13 |

| Maternal serum ethanol concentration (mg ethanol/dl serum, collected at the end of a 4-h drinking period) | N.A. (24) | 84.0 ± 5.5 |

| Litter size (no. live births/litter) | 12.5 ± 0.1 (41) | 12.4 ± 0.3 (42) |

| Pup birth weight (g) | 6.17 ± 0.13 (41) | 6.13 ± 0.11 (42) |

| Male offspring weights at surgery (g body weight on day of stereotaxic surgery) | 473 ± 10 (24) | 473 ± 10 (21) |

N.A., not applicable.

Baseline Input/Output Responses.

Figure 1 depicts input/output curves for fEPSP slope and PS amplitude in control and fetal ethanol-exposed offspring treated with either saline or 1 mg of ABT-239/kg. Synaptic responses to stimuli ranging from 50 to 500 μA collected before tetanus were not affected by prenatal ethanol exposure (Fig. 1, A and B), suggesting that the stimulus-response mechanisms mediating baseline glutamate release and postsynaptic ionotropic glutamate receptor responsiveness to glutamate are intact in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring. Furthermore, ABT-239 treatment did not affect input/output curves compared with those of saline-treated offspring in either prenatal treatment group (Fig. 1, C and D). Immediately after establishing the input/output curve for each rat, a curve-fitting procedure was used to determine the ES40. The ES40 was then used for both the test stimulus and the HFS tetanization protocol in subsequent recordings. The mean ES40 values were not different across the four experimental groups (saccharin-saline, 305 ± 17 μA; ethanol-saline, 323 ± 18 μA; saccharin-ABT-239, 281 ± 14 μA; and ethanol-ABT-239, 290 ± 14 μA).

Fig. 1.

Effect of prenatal ethanol exposure and ABT-239 on input/output responses to perforant path stimulation of dentate granule cells over a current intensity range of 50 to 500 μA. A, fEPSP responses, expressed in volts per millisecond, in control and fetal ethanol-exposed offspring in the absence of ABT-239. B, PS amplitude responses, expressed in volts, in control and fetal ethanol-exposed offspring in the absence of ABT-239. C, fEPSP responses in control and fetal ethanol-exposed offspring in the presence of 1 mg/kg ABT-239. D, PS amplitude responses in control and fetal ethanol-exposed offspring in the presence of ABT-239. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E.M. of responses from the number of rats noted in parentheses for each experimental group.

Synaptic Responses to the 10- and 3-Tetanus Train Protocols.

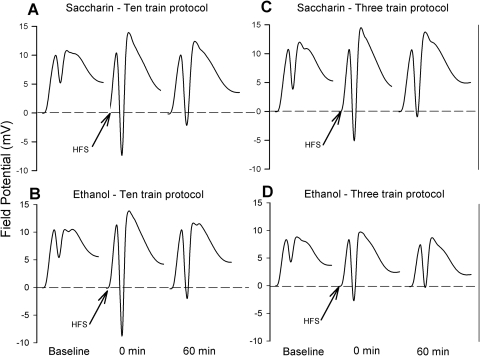

Field potential wave form responses obtained from saline-treated rats in the two prenatal treatment groups using the 10- and 3-tetanus train protocols are depicted in Fig. 2. The response curves are characterized by a rapid ascending fEPSP followed by a negative PS, a typical response of dentate gyrus granule cells upon medial perforant pathway stimulation. Figure 3 summarizes the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on LTP after either the 10- or 3-tetanus train protocol in the absence of ABT-239 treatment. Application of 10 tetanizing trains resulted in LTP in both prenatal exposure groups. The fEPSP slope was significantly increased compared with baseline values in controls and ethanol-exposed rats (Fig. 3A) throughout the 60-min post-tetanus recording period. Population spike amplitude was also significantly elevated in both groups compared with baseline (Fig. 3B) during the 60-min post-tetanus period. No statistical differences between control and ethanol-exposed offspring were observed.

Fig. 2.

Stimulus-response curves of dorsal dentate granule cell recordings from controls (A and C) and prenatal ethanol-exposed offspring (B and D), before and after the application of either 10 (A and B) or 3 (C and D) trains of high-frequency (400 Hz) stimulations (HFS indicated by arrows). Each curve represents the mean of 30 field potential responses over a 5-min interval in a single rat before tetanus, immediately after tetanus (time 0) and 60 min after tetanus.

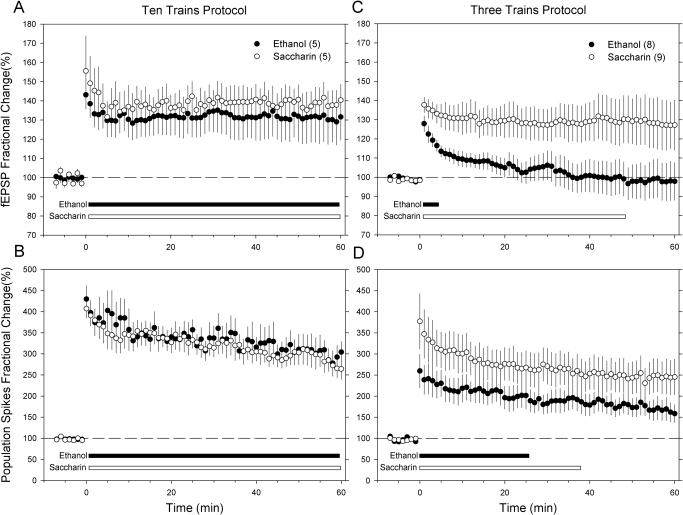

Fig. 3.

Effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on dentate granule cell responses before and after 10 or 3 trains of HFS. Graphs illustrate fEPSP responses (A) and PS amplitude responses (B) after 10 tetanizing trains and fEPSP responses (C) and PS amplitude responses (D) after 3 tetanizing trains. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E.M. responses averaged over 1-min intervals from five to nine rats in each experimental group (sample sizes are noted in parentheses). The horizontal bars at the bottom of each graph denote the duration of time after tetanus that each response was significantly greater than the pretetanus baseline response (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks, Dunnett's post hoc test, p < 0.05).

The 3-tetanus train protocol produced slightly less synaptic potentiation in the control group at time 0 compared with the 10-tetanus train protocol. The potentiation of the fEPSP response was significantly greater than the (pretetanus) baseline for up to 48 min post-tetanus (Fig. 3C), whereas the PS amplitude was significantly greater than baseline up to 37 min post-tetanus (Fig. 3D). In striking contrast to the control group, potentiation of the fEPSP response in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring only lasted for the first 5 min after tetanus and then rapidly decayed to the baseline level (Fig. 3C). Pairwise comparisons indicated that the fEPSP response in prenatal ethanol-exposed rats was significantly less than control at all time points after the first 2 min post-tetanus. Although the duration of PS amplitude potentiation was 13 min shorter in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring compared with controls (Fig. 3D), pairwise comparisons at each time point did not reveal significant differences in PS responses between prenatal treatment groups.

Effects of ABT-239 on Synaptic Potentiation Using the 3-Tetanus Train Protocol.

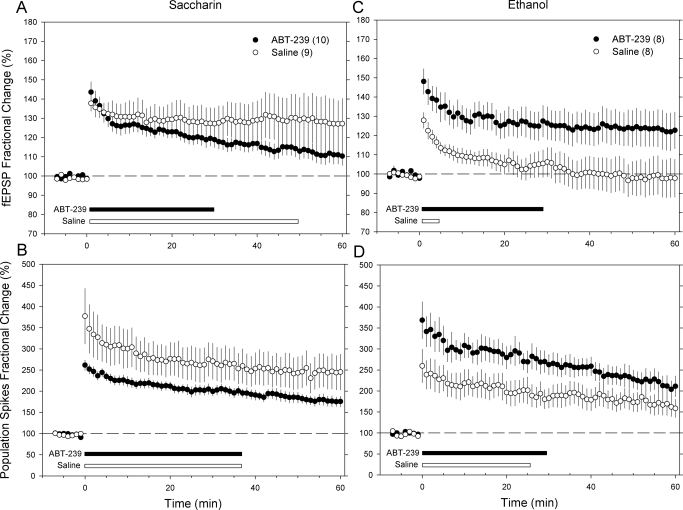

The effects of ABT-239 on LTP using the 3-tetanus train protocol are depicted in Fig. 4. In control offspring, ABT-239 did not enhance fEPSP slope or PS amplitude compared with saline-treated controls. Indeed, ABT-239 reduced the duration of time after tetanus when the fEPSP response was significantly elevated above baseline (Fig. 4A) without altering the potentiation of the PS amplitude response (Fig. 4B). However, pairwise comparisons indicated that the fEPSP responses at each time point post-tetanus were not different between the saline- and ABT-239-treated control rats.

Fig. 4.

Effect of ABT-239 on LTP induced by 3 tetanizing stimulus trains. Graphs illustrate fEPSP (top) and PS responses (bottom) in the control (A and B) or fetal ethanol-exposed (C and D) groups treated with either saline or 1 mg of ABT-239/kg i.p. approximately 2 h before tetanization. Each data point represents the mean ± S.E.M. responses averaged over 1-min intervals from 8 to 10 rats in each experimental group (sample sizes are noted in parentheses). The horizontal bars at the bottom of each graph denote the duration of time after tetanus that each response was significantly greater than the pretetanus baseline response (one-way repeated-measures ANOVA on ranks, Dunnett's post hoc test, p < 0.05).

In contrast to control rats, ABT-239 elevated both fEPSP and PS amplitude responses in prenatal ethanol-exposed rats compared with saline-treated rats (Fig. 4, C and D). ABT-239 markedly increased the duration of time that fEPSP responses were elevated over baseline to a level similar to that of the ABT-239-treated saccharin control rats. Pairwise comparisons indicated that the fEPSP responses in ABT-239-treated fetal ethanol rats were significantly greater than those in saline-treated fetal ethanol rats. Conversely, ABT-239-treated fetal ethanol rats were not significantly different from either the saline- or ABT-239-treated saccharin control rats. ABT-239 also increased PS amplitude responses in fetal ethanol rats (Fig. 4D), but the effects were more modest. The period of time when PS amplitude was significantly greater than baseline was increased by just 5 min in ABT-239-treated fetal ethanol rats, and the differences between saline- and ABT-239-treated fetal ethanol rats at each post-tetanus time interval were generally not significant.

Discussion

There are two salient observations from this study. First, intermittent voluntary consumption of moderate quantities of ethanol during pregnancy reduces LTP in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring, but only when a submaximal number of tetanizing trains are used. When 10 tetanizing trains were used to elicit maximal LTP, no differences were observed between groups (Fig. 3, A and B). However, the synaptic potentiation elicited by 3 tetanizing trains was markedly reduced in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring compared with controls (Fig. 3, C and D). Thus, the effects of prenatal ethanol exposure on synaptic potentiation are subtle, reminiscent of the subtle learning deficits we have observed in littermates of the offspring used in this study (Savage et al., 2010). The effect of prenatal ethanol exposure on LTP using the 3-tetanus train protocol (Fig. 3, C and D) is qualitatively similar to that reported by Sutherland et al. (1997). In particular, the fEPSP response in fetal ethanol-exposed rats rapidly decayed back to baseline levels within 5 min after tetanus (Fig. 3C). Population spike responses were also diminished in the fetal ethanol-exposed group (Fig. 3D) but to a lesser extent than fEPSP responses. The mechanisms by which prenatal ethanol exposure adversely affects fEPSP to a greater extent than PS amplitude after submaximal tetanizing stimuli is unknown. A strong correlation between fEPSP slope and PS latency was observed in all treatment groups (data not shown), which indicates that neither fetal ethanol exposure nor ABT-239 treatment affects fEPSP/PS coupling. Several authors have reported dissociations between fEPSP slope and PS amplitude after high-frequency tetanization (Bliss and Gardner-Medwin, 1973; Taube and Schwartzkroin, 1988), suggesting that these are independent parameters and reflect different cellular mechanisms. The early aspects of the fEPSP used for slope measurement are primarily dependent on AMPA receptor activation and activity-dependent increases in fEPSP slope are attributable to increased affinity or number of AMPA receptors responding to glutamate released with the test stimulus. In contrast, the PS reflects the number of granule cells firing action potentials, and increases in PS amplitude after tetanus indicate an increase in the number of cells firing action potentials in response to the test stimulus (Bliss and Lomo, 1973; Taube and Schwartzkroin, 1988). Given that fEPSP potentiation was impaired to a greater extent than PS amplitude potentiation, our results suggest that prenatal ethanol exposure may affect the mechanisms responsible for increased postsynaptic AMPA receptor-mediated granule cell depolarizations after tetanus, whereas the recruitment of additional granule cells after tetanus is affected to a lesser extent.

The differential fEPSP responses in control and fetal ethanol-exposed rat after three trains of tetanic stimulation is reminiscent of results reported by Raymond (2007), describing different forms of LTP distinguished by the magnitude and duration of the LTP response. In this paradigm, four trains of tetanus (LTP2) produce a fEPSP response curve similar to our three-train paradigm in controls (Fig. 3, C and D). His one-train paradigm (LTP1) produced a fEPSP response more robust than the three-train response in our fetal ethanol-exposed rats (Fig. 3C). Raymond attributed these different levels of LTP to a progressively increasing involvement of different but synergistic mechanisms for increasing postsynaptic cytoplasmic calcium levels. In particular, LTP1 involves NMDA receptor-mediated increases in calcium and LTP2 includes the synergistic involvement of group I mGluR receptor-activated signaling cascades that trigger calcium release from endoplasmic stores. The differential LTP effect observed with a three tetanizing train stimulus suggests that a diminished contribution of mGluR receptor-mediated elevations in cytoplasmic calcium may be one factor contributing to the LTP deficit in fetal ethanol-exposed rats. The gradual decay in LTP between 5 and 30 min after tetanus is consistent with the lack of more slowly developing cellular signaling mechanisms important in the maintenance phase of LTP (Reymann and Frey, 2007). In support of this speculation, we have observed significant reductions in mGluR5 receptors in the dentate gyrus of fetal ethanol-exposed rats (Galindo et al., 2004). Studies in other laboratories have demonstrated the facilitatory role of mGluR5 receptors in the expression of LTP, particularly under submaximal tetanizing conditions (Raymond et al., 2000; Naie and Manahan-Vaughan, 2005). These data suggest that diminished mGluR5 receptor function in fetal ethanol-exposed rats may be critical in the inability of these rats to elicit a “LTP2-type” response after three tetanizing trains, as was observed in the control rats (Fig. 3A).

In addition to putative postsynaptic mechanisms for this fetal ethanol-induced LTP deficit, it is important to note that presynaptic mechanisms may also contribute to this deficit. Prenatal ethanol exposure in Sprague-Dawley rats produced a striking reduction in mGluR5 agonist-stimulated phosphorylation of presynaptically localized GAP-43 in dentate gyrus slices (Galindo et al., 2004). This deficit was accompanied by a similar deficit in mGluR5 agonist potentiation of [3H]d-aspartate release, a marker of glutamate release, from dentate gyrus slices (Galindo et al., 2004). Furthermore, whereas electrically evoked [3H]d-aspartate release in response to a test stimulus was not different between controls and fetal ethanol-exposed rats, the ability of three trains of high-frequency stimulations to potentiate evoked [3H]d-aspartate release from hippocampal slices, a process that develops over the first 30 min after tetanus, was significantly reduced in fetal ethanol-exposed rats (Savage et al., 1998). Both the timing and magnitude of these changes suggest that fetal ethanol-induced deficits in activity-dependent elevations in glutamate release could contribute to the results observed in Fig. 3C. Subsequent studies of entorhinal cortical perforant path nerve terminal function in Long-Evans rats will be required to substantiate this speculation.

The second principal observation in this study is that the LTP deficit observed in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring can be ameliorated by treatment with the histamine H3 receptor antagonist ABT-239. ABT-239 restored LTP in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring to levels not significantly different from those of saline-treated control rats (Fig. 4). At the 1 mg/kg dose, ABT-239 enhanced synaptic potentiation (Fig. 4, C and D) without increasing baseline input/output responses (Fig. 1, C and D), suggesting that the histamine H3 receptor system affects the mechanisms of activity-dependent synaptic potentiation at doses that do not affect baseline neurotransmission. Although it is tempting to speculate that the primary action of ABT-239 was to directly facilitate glutamate release from perforant path nerve terminals in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring, there are other mechanisms of ABT-239 action that may have contributed to enhanced synaptic potentiation. For example, the inhibition of H3 receptors on cholinergic nerve terminals facilitates acetylcholine release (Fox et al., 2005), which, in turn, could facilitate glutamatergic neurotransmission. In addition, H3 receptor antagonist-mediated inhibition of autoreceptors located on histaminergic nerve terminals promotes histamine release (Arrang et al., 1983), which may facilitate excitation of glutamatergic neurons mediated via histamine H1 and H2 receptors (Haas, 1984; Manahan-Vaughan et al., 1998). Furthermore, histamine has been reported to have positive allosteric effects at the spermidine site on NMDA receptors (Bekkers, 1993). The extent to which each of these other putative mechanisms of ABT-239 action may have contributed to prolonged synaptic potentiation in fetal ethanol-exposed offspring is not known, but it is likely that the manner by which H3 receptor antagonists enhance synaptic transmission at glutamatergic synapses in the central nervous system is complex.

One of the curious observations from these studies is the fact that LTP was not enhanced by the administration of ABT-239 in saccharin control offspring (Fig. 4, A and B). This is notable, in part, because the 3-tetanus train protocol did not maximize the degree of synaptic potentiation possible compared with the 10-tetanus train protocol (Fig. 3). Indeed, the data suggest that ABT-239 produced a slight inhibition of synaptic potentiation at the 1 mg/kg dose (Fig. 4, A and B), whereas basic input/output responses before the tetanizing protocol were unaffected (Fig. 1, C and D). The basis for the differential effect of ABT-239 on synaptic potentiation between prenatal ethanol-exposed and control offspring is unknown. However, this differential effect raises questions of whether prenatal ethanol exposure has altered histaminergic regulation of glutamatergic transmission in a manner that is amenable to therapeutic intervention. Specifically, does fetal ethanol exposure elevate the inhibitory influence of H3 receptors on glutamate and, possibly, acetylcholine release in the dentate gyrus? A preliminary study of histamine H3 agonist-stimulated [35S]guanosine 5′-O-(3-thio)triphosphate binding has revealed that histamine H3 receptor-effector coupling is significantly increased in the dentate gyrus of fetal ethanol-exposed rats (D. D. Savage, J. B. Chavez, J. L. Seidel, and M. J. Rosenberg, unpublished observations). These results lend credence to the speculation of a fetal alcohol-induced enhancement of histamine H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of activity-dependent synaptic potentiation. This speculation is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

In summary, we have observed that fetal ethanol-induced LTP deficits are amenable to a cognition-enhancing agent that acts as a H3 receptor antagonist. The fact that ABT-239 was without effect in unexposed control rat offspring highlights the importance of examining the therapeutic potential of agents in animal models that emulate the clinical disorder in question. Furthermore, the differential effect in fetal ethanol-exposed rats compared with controls also raises suspicion that prenatal ethanol exposure may have altered histaminergic regulation of excitatory neurotransmission in affected brain regions. The mechanistic basis for these alterations is unknown but may involve fetal alcohol-induced alterations in histamine neurotransmission, an area that has not been investigated in this field of research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Marion Cowart, Timothy Esbenshade, and Tiffany Garrison and Abbott Laboratories for the generous donation of ABT-239. We also thank Dr. Robert Sutherland for helpful discussions about the data and Denise Cordaro, Christie Wilcox, and Dr. Kevin O'Hair for their outstanding animal care support for this project.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [Grants AA016619, AA017068]; and by dedicated research funds from the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.109.165027.

- NDMA

- N-methyl-d-aspartate

- ABT-239

- 4-(2-{2-[(2R)-2-methylpyrrolidinyl]ethyl}-benzofuran-5-yl)benzonitrile

- mGluR

- metabotropic glutamate receptor

- LTP

- long-term potentiation

- PS

- population spike

- ES40

- stimulus intensity sufficient to generate 40% of maximal population spike response

- HFS

- high-frequency stimulation

- fEPSP

- fast excitatory postsynaptic potential slope

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- AMPA

- α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid.

References

- Andrews JS. (1996) Possible confounding influence of strain, age and gender on cognitive performance in rats. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res 3:251–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrang JM, Garbarg M, Schwartz JC. (1983) Auto-inhibition of brain histamine release mediated by a novel class (H3) of histamine receptor. Nature 302:832–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekkers JM. (1993) Enhancement by histamine of NMDA-mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Science 261:104–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Gardner-Medwin AR. (1973) Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the unanaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol 232:357–374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss TV, Lomo T. (1973) Long-lasting potentiation of synaptic transmission in the dentate area of the anaesthetized rabbit following stimulation of the perforant path. J Physiol 232:331–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RE, Reymann KG. (1996) Histamine H3 receptor-mediated depression of synaptic transmission in the dentate gyrus of the rat in vitro. J Physiol 496 (Pt 1):175–184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapham J, Kilpatrick GJ. (1992) Histamine H3 receptors modulate the release of [3H]-acetylcholine from slices of rat entorhinal cortex: evidence for the possible existence of H3 receptor subtypes. Br J Pharmacol 107:919–923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa ET, Savage DD, Valenzuela CF. (2000) A review of the effects of prenatal or early postnatal ethanol exposure on brain ligand-gated ion channels. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:706–715 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esbenshade TA, Fox GB, Krueger KM, Miller TR, Kang CH, Denny LI, Witte DG, Yao BB, Pan L, Wetter J, et al. (2005) Pharmacological properties of ABT-239 [4-(2-{2-[(2R)-2-methylpyrrolidinyl]ethyl}-benzofuran-5-yl)benzonitrile]: I. Potent and selective histamine H3 receptor antagonist with drug-like properties. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313:165–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley AG, Prendergast A, Barry C, Scully D, Upton N, Medhurst AD, Regan CM. (2009) H3 receptor antagonism enhances NCAM PSA-mediated plasticity and improves memory consolidation in odor discrimination and delayed match-to-position paradigms. Neuropsychopharmacology 34:2585–2600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GB, Esbenshade TA, Pan JB, Radek RJ, Krueger KM, Yao BB, Browman KE, Buckley MJ, Ballard ME, Komater VA, et al. (2005) Pharmacological properties of ABT-239 [4-(2-{2-[(2R)-2-methylpyrrolidinyl]ethyl}-benzofuran-5-yl)benzonitrile]: II. Neurophysiological characterization and broad preclinical efficacy in cognition and schizophrenia of a potent and selective histamine H3 receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 313:176–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox GB, Pan JB, Faghih R, Esbenshade TA, Lewis A, Bitner RS, Black LA, Bennani YL, Decker MW, Hancock AA. (2003) Identification of novel H3 receptor (H3R) antagonists with cognition enhancing properties in rats. Inflamm Res 52 (Suppl 1):S31–S32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galindo R, Frausto S, Wolff C, Caldwell KK, Perrone-Bizzozero NI, Savage DD. (2004) Prenatal ethanol exposure reduces mGluR5 receptor number and function in the dentate gyrus of adult offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28:1587–1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas HL. (1984) Histamine potentiates neuronal excitation by blocking a calcium-dependent potassium conductance. Agents Actions 14:534–537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DA, Kodituwakku P, Sutherland RJ, Savage DD. (2003) Children with fetal alcohol syndrome are impaired at place learning but not cued-navigation in a virtual Morris water task. Behav Brain Res 143:85–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson JL, Jacobson SW, Sokol RJ, Ager JW., Jr (1998) Relation of maternal age and pattern of pregnancy drinking to functionally significant cognitive deficit in infancy. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22:345–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Smith DW. (1973) Recognition of the fetal alcohol syndrome in early infancy. Lancet 302:999–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodituwakku PW. (2009) Neurocognitive profile in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Dev Disabil Res Rev 15:218–224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemoine P, Haronsseau H, Borteryu JP, Menuet JC. (1968) Les enfants de parents alcooliques: anomalies observees a propos de 127 cas. Ouest Med 25:476–482 [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist F, Fugmann U, Klaning E, Rasmussen H. (1959) The metabolism of acetaldehyde in mammalian tissues: reactions in rat-liver suspensions under anaerobic conditions. Biochem J 72:409–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manahan-Vaughan D, Reymann KG, Brown RE. (1998) In vivo electrophysiological investigations into the role of histamine in the dentate gyrus of the rat. Neuroscience 84:783–790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller TR, Baranowski JL, Estvander BR, Witte DG, Carr TL, Manelli AM, Krueger KM, Cowart MD, Brioni JD, Esbenshade TA. (2008) A robust and high-capacity [35S]GTPγS binding assay for determining antagonist and inverse agonist pharmacological parameters of histamine H3 receptor ligands. Assay Drug Dev Technol 6:339–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naie K, Manahan-Vaughan D. (2005) Pharmacological antagonism of metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 regulates long-term potentiation and spatial reference memory in the dentate gyrus of freely moving rats via N-methyl-d-aspartate and metabotropic glutamate receptor-dependent mechanisms. Eur J Neurosci 21:411–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. (1986) The Rat Brain: In Stereotaxic Coordinates, Academic Press, Sydney [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen DD, Boldt BM, Bryant CA, Mitton DR, Larsen SA, Wilkinson CW. (2000) Chronic daily ethanol and withdrawal: 1. Long-term changes in the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 24:1836–1849 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CR. (2007) LTP forms 1, 2 and 3: different mechanisms for the “long” in long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci 30:167–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CR, Thompson VL, Tate WP, Abraham WC. (2000) Metabotropic glutamate receptors trigger homosynaptic protein synthesis to prolong long-term potentiation. J Neurosci 20:969–976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reymann KG, Frey JU. (2007) The late maintenance of hippocampal LTP: requirements, phases, ‘synaptic tagging’, ‘late-associativity’ and implications. Neuropharmacology 52:24–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DD, Cruz LL, Duran LM, Paxton LL. (1998) Prenatal ethanol exposure diminishes activity-dependent potentiation of amino acid neurotransmitter release in adult rat offspring. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 22:1771–1777 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage DD, Rosenberg MJ, Wolff CR, Akers KG, El-Emawy A, Staples MC, Varaschin RK, Wright CA, Seidel JL, Caldwell KK, Hamilton DA. (2010) Effects of a novel cognition-enhancing agent on fetal ethanol-induced learning deficits. Alcohol Clin Exp Res DOI: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01266.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Betz R, Göthert M. (1988) Histamine H3 receptor-mediated inhibition of serotonin release in the rat brain cortex. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 337:588–590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Fink K, Detzner M, Göthert M. (1993) Histamine inhibits dopamine release in the mouse striatum via presynaptic H3 receptors. J Neural Transm Gen Sect 93:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlicker E, Fink K, Hinterthaner M, Göthert M. (1989) Inhibition of noradrenaline release in the rat brain cortex via presynaptic H3 receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 340:633–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Sampson PD. (1990) Moderate prenatal alcohol exposure: effects on child IQ and learning problems at age 7 1/2 years. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 14:662–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Sampson PD, Olson HC, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Scott M, Feldman J, Mirsky AF. (1994) Maternal drinking during pregnancy: attention and short-term memory in 14-year-old offspring—a longitudinal prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 18:202–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland RJ, McDonald RJ, Savage DD. (1997) Prenatal exposure to moderate levels of ethanol can have long-lasting effects on hippocampal synaptic plasticity in adult offspring. Hippocampus 7:232–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland RJ, McDonald RJ, Savage DD. (2000) Prenatal exposure to moderate levels of ethanol can have long-lasting effects on learning and memory of adult rat offspring. Psychobiology 28:532–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taube JS, Schwartzkroin PA. (1988) Mechanisms of long-term potentiation: EPSP/spike dissociation, intradendritic recordings, and glutamate sensitivity. J Neurosci 8:1632–1644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeber EJ, Savage DD, Sutherland RJ, Caldwell KK. (2001) Fear conditioning-induced alterations of phospholipase C-β1a protein level and enzyme activity in rat hippocampal formation and medial frontal cortex. Neurobiol Learn Mem 76:151–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]