Abstract

Distinct populations of leptin-sensing neurons in the hypothalamus, midbrain, and brainstem contribute to the regulation of energy homeostasis. To assess the requirement for leptin signaling in the hypothalamus, we crossed mice with a floxed leptin receptor allele (Leprfl) to mice transgenic for Nkx2.1-Cre, which drives Cre expression in the hypothalamus and not in more caudal brain regions, generating LeprNkx2.1KO mice. From weaning, LeprNkx2.1KO mice exhibited phenotypes similar to those observed in mice with global loss of leptin signaling (Leprdb/db mice), including increased weight gain and adiposity, hyperphagia, cold intolerance, and insulin resistance. However, after 8 weeks of age, LeprNkx2.1KO mice maintained stable adiposity levels, whereas the body fat percentage of Leprdb/db animals continued to escalate. The divergence in the adiposity phenotypes of Leprdb/db and LeprNkx2.1KO mice with age was concomitant with increased rates of linear growth and energy expenditure in LeprNkx2.1KO mice. These data suggest that remaining leptin signals in LeprNkx2.1KO mice mediate physiological adaptations that prevent the escalation of the adiposity phenotype in adult mice. The persistence of severe adiposity in LeprNkx2.1KO mice, however, suggests that compensatory actions of circuits regulating growth and energy expenditure are not sufficient to reverse obesity established at an early age.

Introduction

Given the increased worldwide prevalence of obesity and associated chronic diseases, understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms regulating food intake, body composition, and energy expenditure have become a research priority (1, 2). The discovery of leptin, an adipokine (3) that circulates in levels proportional to fat stores (4), and its receptor (encoded by Lepr; refs. 5, 6) initiated a fundamental change in the way scientists view the circuits regulating energy homeostasis. Analyses of mice lacking leptin (Lepob/ob) and Lepr (Leprdb/db) provided evidence that leptin signaling influences a wide range of phenotypes related to energy balance, including food intake, body composition, glucose homeostasis, metabolic rate, and thermoregulation (7–10). Cells in the CNS expressing the long isoform of Lepr (Lepr-b) have been shown to mediate most of leptin’s effects on energy balance (11–14).

The highest levels of Lepr-b expression are found in the mediobasal hypothalamus (15, 16). This finding, together with the observations that physical or chemical ablation of neurons in the hypothalamus resulted in severe dysregulation of food intake and body composition (17–20), led many to hypothesize that the hypothalamus is the principal site of leptin-mediated regulation of phenotypes related to energy homeostasis. Moreover, localized restoration of Lepr-b expression in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH) ameliorates many of the metabolic phenotypes of Leprdb/db mice (21, 22). Conversely, the selective loss of Lepr-b signaling in subpopulations of neurons in the ARH or ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH) results in alterations in phenotypes related to energy homeostasis (although the phenotypes were often mild compared with Leprdb/db animals; refs. 23–25).

Although the most extensive efforts have focused on characterizing leptin-mediated signaling in hypothalamic neurons, a growing body of evidence supports the idea that leptin’s effects on energy balance are also mediated by Lepr-b–expressing neurons in other regions of the CNS. Brainstem nuclei, such as the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and dorsal raphe, express Lepr-b and have been implicated in the regulation of phenotypes related to energy expenditure, food intake, and body composition (26–28). Leptin-sensing neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) have been reported to modulate signaling in the mesolimbic dopamine system associated with food reward (29–31). Extrahypothalamic leptin-sensing populations could exert their influence on energy homeostasis through circuits that are dependent and/or independent of leptin-sensing circuits in the hypothalamus.

In order to distinguish the requirement for leptin signaling in the hypothalamus from the contributions of leptin-sensing neurons in the midbrain and brainstem, we used a genetic strategy to restrict disruption of leptin signaling to the forebrain. We used the Nkx2.1-Cre driver line to achieve early and broad Cre recombinase expression in the hypothalamus and not in the caudal CNS (32). Nkx2.1-Cre mice were crossed to mice segregating for a conditional allele of Lepr in which loxP sites flank exon 17 (Leprfl), the exon that contains the Box 1 motifs crucial for leptin signal transduction through JAK2 and STAT3 pathways (33). Cre-mediated recombination of the Leprfl allele produces a LEPR that lacks exon 17 and has a truncated missense exon 18, which has previously been reported to recapitulate the phenotypes found in the Leprdb/db1J mutation (23, 33).

We found that phenotypes related to fat deposition, food intake, energy expenditure, thermoregulation, and glucose homeostasis in young Nkx2.1-Cre;Leprfl/fl mice (hereafter referred to as LeprNkx2.1KO mice) closely resembled those described for Leprdb/db animals (34). From 8 weeks of age, LeprNkx2.1KO mice maintained a stable level of adiposity and did not exhibit the continuous increase in percent body fat seen in Leprdb/db mutants. The observed increases in linear growth, metabolic rate, and locomotor activity and changes in thermoregulatory circuits of LeprNkx2.1KO compared with Leprdb/db animals likely contribute to the stabilization of adiposity levels in mature LeprNkx2.1KO mice. These results raise the possibility that hypothalamic leptin signals are critical for establishing baselines of metabolic phenotypes in young animals that are maintained through the actions of distinct signaling networks in mature animals.

Results

Strategy to disrupt leptin signaling in the hypothalamus.

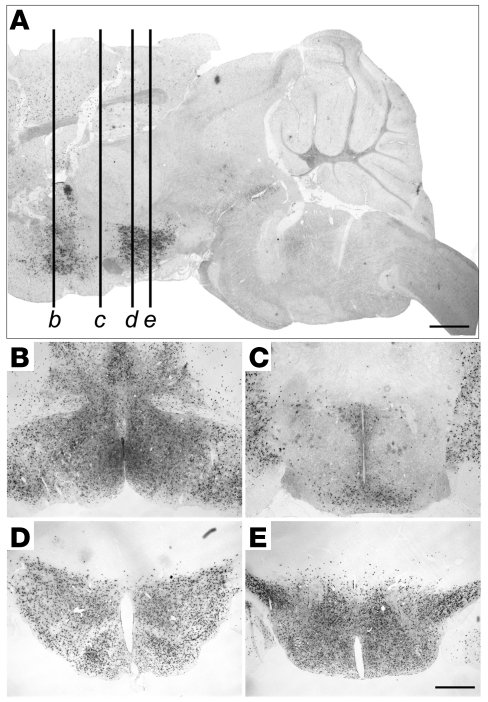

To limit the disruption of leptin signaling to the hypothalamus and not affect other regions implicated in mediating leptin’s effects on energy homeostasis, we used a transgenic line in which Cre recombinase expression is regulated by Nkx2.1 promoter elements. The Nkx2.1-Cre driver recapitulates the normal pattern of Nkx2.1 expression in the ventral forebrain, medial ganglionic eminence, posterior pituitary, lungs, esophagus, and thyroid starting at embryonic day 9.5 (32, 35, 36). To characterize the distribution of functional Cre protein within the hypothalamus, we crossed Nkx2.1-Cre mice with ROSA26LacZ reporter mice (37) and examined the resulting Nkx2.1-Cre;ROSA26LacZ mice for β-galactosidase activity. We observed broad X-gal staining throughout most of the hypothalamus, including all of the nuclei that have been previously implicated in leptin sensing and/or energy homeostasis, such as the medial preoptic area, paraventricular nucleus, ARH, VMH, dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (DMH), lateral hypothalamic area, and ventral premammillary nucleus (Figure 1). Scattered X-gal–stained cells were sometimes detected in the subfornical organ, a previously reported site of leptin action (38). One notable exception to the near-ubiquitous distribution of active Cre protein within the hypothalamus was that many neurons at the level of the suprachiasmatic nucleus were not stained with X-gal (Figure 1, A and C). We did not detect X-gal staining in caudal brain regions, including in extrahypothalamic nuclei that have been implicated in energy homeostasis, such as the VTA and dorsal raphe (Figure 1A). Thus, consistent with previous reports (32), we found that the Nkx2.1-Cre driver was not active in caudal brain regions.

Figure 1. The Nkx2.1-Cre driver is expressed broadly in the hypothalamus, but not in the midbrain or brainstem.

X-gal staining in sagittal (A) and coronal (B–E) sections of Nkx2.1-Cre;ROSA26LacZ mice. (A) Sagittal section approximately 200 μm from midline. Labeled lines correspond to approximate locations of coronal sections in B–E: medial preoptic area (B), suprachiasmatic nucleus and paraventricular nucleus (C), ARH (D), and ventral premammillary nucleus (E). Scale bars: 2 mm (A); 500 μm (B–E).

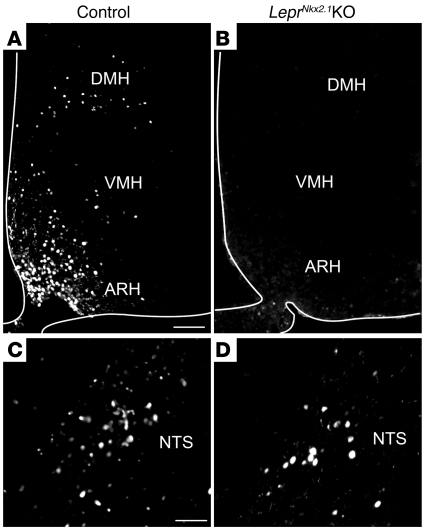

We generated LeprNkx2.1KO mice by crossing Leprfl/fl mice with Nkx2.1-Cre mice. F1 Leprfl/+ and Nkx2.1-Cre;Leprfl/+ offspring were bred to generate the experimental LeprNkx2.1KO mice and Leprfl/fl littermate controls. In LeprNkx2.1KO mice, a truncated form of Lepr that lacks critical JAK and STAT3 motifs is generated in Cre-expressing cells (33). To verify that leptin signaling is disrupted in the hypothalamus and not in the brainstem, we assessed whether the STAT3 pathway is activated in response to an acute peripheral leptin injection by performing immunohistochemistry to detect the phosphorylated form of STAT3 (pSTAT3; ref. 39). Following the injection of a single i.p. dose of leptin, we observed pSTAT3 immunoreactivity in the ARH, VMH, DMH, and NTS of controls (Figure 2, A and C). In LeprNkx2.1KO mice treated with leptin, similar numbers of cells in the NTS were pSTAT3 immunoreactive, whereas there were few to no pSTAT3-immunoreactive cells in the ARH, VMH, or DMH (Figure 2, B and D). Control and LeprNkx2.1KO mice injected with PBS had a few pSTAT3-immunoreactive cells in the ventromedial ARH, but not in any other brain region assessed (data not shown).

Figure 2. Disruption of leptin signaling is localized to the hypothalamus in LeprNkx2.1KO mice.

(A–D) Immunohistochemical detection of p-STAT3 following overnight fast and subsequent treatment with leptin. p-STAT3 staining was detected in the ARH, VMH, and DMH (A) and the NTS (C) of control animals. p-STAT3 staining was not observed in the ARH, VMH, or DMH (B), but was seen in the NTS (D), of LeprNkx2.1KO animals. White outlines in A and B denote tissue edges. Scale bars: 100 μm (A and B); 50 μm (C and D).

Disruption of hypothalamic leptin signaling leads to obesity in young animals and increased somatic growth.

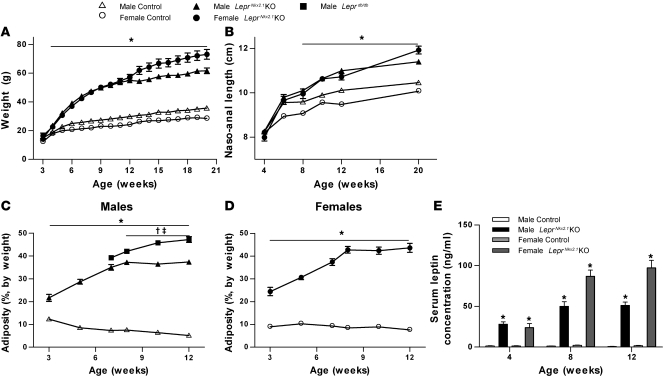

We first investigated the requirement for hypothalamic leptin signals in the regulation of body weight, somatic growth, and body composition in LeprNkx2.1KO mice and littermate controls. Although there were no significant differences in weight between sex-matched groups at weaning, small but significant differences did emerge by 4 weeks (Figure 3A). The naso-anal lengths of control and LeprNkx2.1KO mice did not differ at 4 or 6 weeks (Figure 3B). At 12 weeks of age, LeprNkx2.1KO mice were considerably heavier than their sex-matched controls (males, 185% of controls; females, 236% of controls; Figure 3A). These sex-matched LeprNkx2.1KO groups were also longer than control groups by about 10% (Figure 3B). Between 12 and 20 weeks of age, LeprNkx2.1KO males exhibited the same rate of increase in body weight and length as did sex-matched controls, whereas LeprNkx2.1KO females continued to grow at a faster rate than LeprNkx2.1KO males and control groups from both sexes; weights of LeprNkx2.1KO females after 13 weeks were significantly higher than age-matched LeprNkx2.1KO males (Figure 3, A and B).

Figure 3. Growth rate and fat deposition are increased in young LeprNkx2.1KO mice.

(A) Weights of male and female LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice; n ≥ 10 for all groups at all points. (B) Naso-anal length over time of male and female LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice; n ≥ 5 for all groups at all points. (C) Adiposity, as measured by NMR, of male LeprNkx2.1KO, control, and Leprdb/db mice over time; n ≥ 4 for all groups at all points. (D) Adiposity, as measured by NMR, of female LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice over time; n ≥ 5 for all groups at all points. (E) Plasma leptin, as measured by ELISA, at 4, 8, and 12 weeks of male and female LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice; n ≥ 5 for all groups at all points. (A–E) Results are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.01, LeprNkx2.1KO versus control; †P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus control; ‡P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus LeprNkx2.1KO. P values were calculated between age- and sex-matched groups.

In contrast to the absence of a body weight phenotype at 3 weeks, the adiposity of 3-week-old LeprNkx2.1KO animals was 2 to 3 times that of sex-matched controls (Figure 3, C and D). From 3 to 8 weeks, LeprNkx2.1KO mice deposited fat at levels disproportionate to their weight gain, reaching 37% body fat in males and 43% in females (Figure 3, C and D). Between 8 and 12 weeks of age, these elevated adiposity levels in LeprNkx2.1KO mice were stably maintained, as fat mass increased in proportion to lean mass in both male and female LeprNkx2.1KO groups. In contrast, adiposity levels in Leprdb/db males steadily increased from 8 to 12 weeks of age. Plasma leptin levels reflected this initial increase and subsequent plateau in adiposity in the LeprNkx2.1KO groups after 8 weeks of age (Figure 3E).

Energy expenditure phenotypes are different in mature LeprNkx2.1KO versus Leprdb/db animals, whereas food intake is similar.

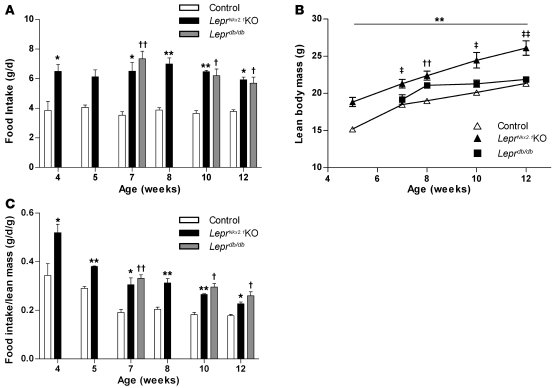

To investigate whether altered body composition in LeprNkx2.1KO animals is caused by differences in energy intake and/or expenditure, we measured food intake, oxygen consumption, and locomotor activity. In both control and LeprNkx2.1KO mice, consistent daily food intake was established by 4 weeks, with LeprNkx2.1KO mice consuming about 60% more than controls at all time points examined (Figure 4A). Daily food intake of LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db mice was not significantly different at 7, 10, or 12 weeks of age. As LeprNkx2.1KO males consistently exhibited increased lean body mass compared with controls (Figure 4B), we considered that higher levels of food intake may not be disproportionate, but are required to sustain elevated growth rates. When normalized to lean mass, food intake of controls during the postweaning period of rapid growth was initially high and subsequently stabilized at lower levels after 8 weeks of age (Figure 4C). Normalized food intake in the LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db groups was elevated over controls from weaning through 12 weeks; however, the degree of hyperphagia in both mutant models decreased gradually with age (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Hyperphagia in LeprNkx2.1KO mice.

(A) Daily food intake of male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice at several ages; n ≥ 3 for all groups at all points. (B) Absolute lean body mass of male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice over time; n ≥ 4 for all groups at all points. (C) Daily food intake of male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice normalized to lean body mass at several ages; n ≥ 3 for all groups at all points. (A–C) Results are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, LeprNkx2.1KO versus control; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus control; ‡P < 0.05, ‡‡P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus LeprNkx2.1KO. P values were calculated between age-matched groups.

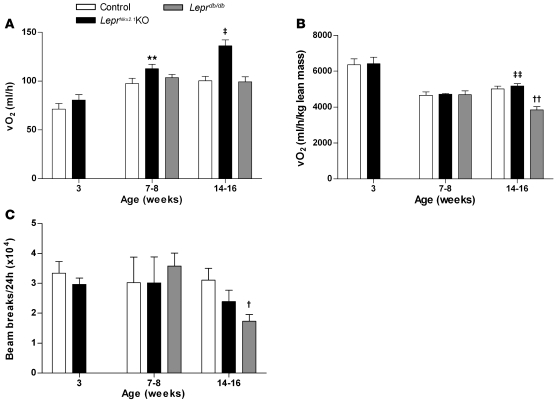

In contrast to the closely correlated energy intake between LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db models, phenotypes related to energy expenditure differed. To account for the fact that the mouse models under consideration exhibit marked differences in body composition, and that lean mass has a higher level of oxygen consumption than fat mass (40), we present the data in terms of total oxygen consumption per mouse and oxygen consumption normalized to lean body mass. At 3 weeks, there was no significant difference in oxygen consumption between LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice, either in absolute terms or when normalized to lean mass (Figure 5, A and B). Locomotor activity in LeprNkx2.1KO males was slightly decreased compared with controls at 3 weeks, but did not reach statistical significance (Figure 5C). We did detect a slight increase in absolute oxygen consumption of LeprNkx2.1KO over controls at 7–8 weeks (control, 97.5 ± 5.5 ml/h; LeprNkx2.1KO, 112.7 ± 4.4 ml/h; n = 3 both groups; P < 0.01); however, we did not detect differences in normalized oxygen consumption or locomotor activity among LeprNkx2.1KO, Leprdb/db, and control groups at this age (Figure 5). At 14–16 weeks, Leprdb/db mice were hypometabolic (normalized oxygen consumption, control, 5,019 ± 151 ml O2/h/kg lean mass; Leprdb/db, 3,848 ± 183 ml O2/h/kg lean mass; n = 3 for both groups; P < 0.01) and exhibited significantly decreased locomotor activity (control, 31,050 ± 3,990 beam breaks/d; Leprdb/db, 17,321 ± 2,220 beam breaks/d; n = 3 for both groups; P < 0.05) relative to controls (Figure 5, B and C). In contrast, 14- to 16-week-old LeprNkx2.1KO mice consumed about 36% more oxygen than did control and Leprdb/db mice (control, 100.3 ± 4.8 ml/h; LeprNkx2.1KO, 136.0 ± 6.2 ml/h; Leprdb/db, 99.3 ± 4.1 ml/h; n = 3 for all groups; P = 0.01, LeprNkx2.1KO vs. control and Leprdb/db). When lean mass was taken into account, LeprNkx2.1KO and control animals consumed similar amounts of oxygen, which was more than that consumed by Leprdb/db mice (Figure 5B). LeprNkx2.1KO mice exhibited an intermediate level of locomotor activity relative to control and Leprdb/db groups, but did not significantly differ from either group (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Increased energy expenditure in LeprNkx2.1KO vs Leprdb/db mice.

(A) Daily absolute oxygen consumption (VO2) of male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice at 3 different ages. (B) Daily oxygen consumption normalized to lean body mass of male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice at 3 different ages. (C) Locomotor activity, as measured by daily beam breaks, in male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice at 3 different ages. (A–C) n ≥ 3 for all groups at all points. Results are mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, LeprNkx2.1KO versus control; †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus control; ‡P < 0.05, ‡‡P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus LeprNkx2.1KO. P values were calculated between age-matched groups.

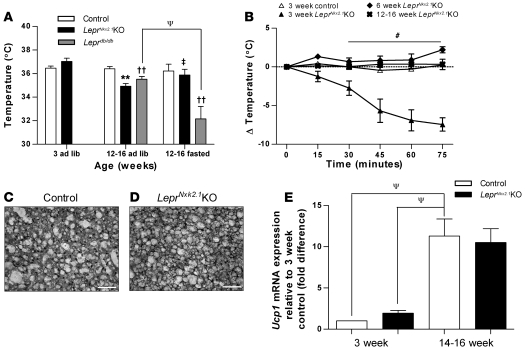

Compared with well-known defects in fed and fasted core body temperature and cold tolerance in Leprdb/db mice, male LeprNkx2.1KO mice displayed an unusual pattern of thermoregulation. In the fed state at 3 weeks, male LeprNkx2.1KO mice showed no difference in core body temperature compared with controls (control, 36.5°C ± 0.2°C, n = 3; LeprNkx2.1KO, 37.0°C ± 0.3°C, n = 7; P = 0.12; Figure 6A). However, as adults, male LeprNkx2.1KO mice in the fed state had core body temperatures significantly lower than controls (control, 36.4°C ± 0.2°C; LeprNkx2.1KO, 34.9°C ± 0.2°C; n = 4 both groups; P < 0.01; Figure 6A). This difference was similar to the difference found between adult Leprdb/db and control mice (control, 36.4°C ± 0.2°C, n = 4; Leprdb/db, 35.5°C ± 0.2°C, n = 8; P < 0.01; Figure 6A). Surprisingly, the core temperature decrease known to occur in Leprdb/db mice in response to fasting was not seen in adult LeprNkx2.1KO mice. Whereas there was a greater than 3°C drop in core body temperature in Leprdb/db mice in response to an overnight fast (ad libitum, 35.5°C ± 0.2°C; overnight fasted, 32.1°C ± 1.1°C; n = 8 for both groups; P < 0.05), no such drop was seen in LeprNkx2.1KO mice (ad libitum, 34.9°C ± 0.2°C, n = 4; overnight fasted, 35.9°C ± 0.5°C, n = 5; P = 0.14; Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Dysregulation of acute thermogenesis in young LeprNkx2.1KO mice.

(A) Baseline core body temperatures in ad libitum–fed or fasting male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice at young and adult time points. (B) Response to acute cold challenge in LeprNkx2.1KO mice at 3, 6, and 12–16- weeks of age and in 3-week-old control mice. (C and D) H&E stain of BAT from 3-week-old control (C) and 3-week-old LeprNkx2.1KO (D) mice. Scale bars: 50 μm. (E) Quantitative PCR analysis of Ucp1 in BAT in control and LeprNkx2.1KO mice at 2 time points. (A, B, and E) n ≥ 4 for all groups at all points. Results are mean ± SEM. **P < 0.01, LeprNkx2.1KO versus control; ††P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus control; ‡P < 0.05, Leprdb/db versus LeprNkx2.1KO; #P < 0.05, 3-week-old LeprNkx2.1KO versus all other groups; ΨP < 0.05 as indicated by brackets.

To further elucidate the thermogenic phenotype, male LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice were exposed to an acute cold challenge at 3, 6, and 12–16 weeks of age. At 3 weeks, LeprNkx2.1KO mice quickly dropped their body temperature (Figure 6B). After 30 minutes, the core body temperature of LeprNkx2.1KO mice had dropped approximately 3°C from baseline. By 75 minutes, the temperature of 5 of 7 subjects had dropped below 30°C, necessitating their removal from the cold stress due to animal welfare concerns. In contrast, 6-week-old LeprNkx2.1KO mice increased their core body temperature by 1.3°C within the first 15 minutes of the cold stress and remained above their initial temperature for the duration of the challenge. LeprNkx2.1KO mice 14–16 weeks of age maintained temperature within 0.4°C of baseline for the extent of the assay. Controls at both 3 weeks (Figure 6B) and 12–16 weeks (data not shown) were found to maintain temperature within approximately 0.5°C of baseline. We did not find any major histological differences in the brown adipose tissue (BAT) from 3-week-old LeprNkx2.1KO mice that could account for the impaired response to cold stress (Figure 6, C and D), nor did we observe infiltration of BAT by white adipocytes in adults, as was previously reported in systemic disruptions of leptin signaling (41). We found no significant differences between BAT Ucp1 expression in LeprNkx2.1KO males and age-matched controls at 3 weeks and at 14–16 weeks (Figure 6E).

Neuroendocrine responses to the loss of hypothalamic leptin signals resemble those of Leprdb/db animals.

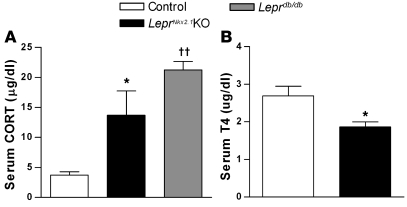

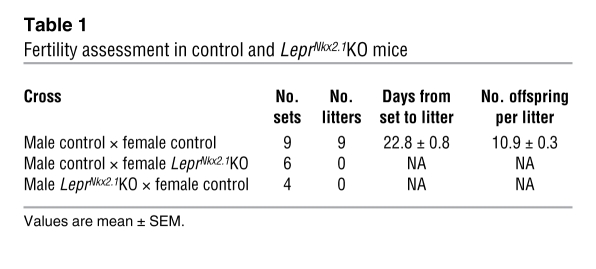

We examined indicators of activity of gonadal, adrenal, and thyroid axes to determine whether LeprNkx2.1KO mice exhibit neuroendocrine profiles similar to fasted animals, as has been previously described for leptin-deficient models (42). To assess phenotypes in the adrenal axis, we measured 10 am serum corticosterone (CORT) levels in 8-week-old animals. Like Leprdb/db males, LeprNkx2.1KO males exhibited elevated CORT levels compared with sex-matched controls (control, 3.69 ± 0.60 μg/ml, n = 13; LeprNkx2.1KO, 13.70 ± 4.02 μg/ml, n = 9; Leprdb/db, 21.23 ± 1.41 μg/ml, n = 4; Figure 7A). We assayed the level of thyroxine (T4) in adult male control and LeprNkx2.1KO mice as an indicator of the activity of the thyroid axis. LeprNkx2.1KO males, on average, had lower T4 levels (control, 2.7 ± 0.3 μg/dl; LeprNkx2.1KO, 1.9 ± 0.1 μg/dl; n = 8 both groups; P < 0.05; Figure 7B). We also assessed reproductive function in male and female LeprNkx2.1KO mice. Animals at least 8 weeks of age were placed in mating cages with wild-type mice for at least 66 days. Whereas 9 of 9 matings between male and female controls produced healthy litters within 4 weeks, both male and female LeprNkx2.1KO mice did not produce any offspring (Table 1).

Figure 7. Activation of the adrenal and thyroid access differs in LeprNkx2.1KO versus control mice.

(A) Morning CORT levels in male control, LeprNkx2.1KO, and Leprdb/db mice at 8 weeks; n > 3 for all groups. (B) Serum T4 levels in male control and LeprNkx2.1KO mice at 13–15 weeks; n = 8 for all groups. (A and B) Results are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, LeprNkx2.1KO versus control; ††P < 0.01, Leprdb/db versus control.

Table 1 .

Fertility assessment in control and LeprNkx2.1KO mice

Disruption of leptin signaling in the hypothalamus leads to early glucose intolerance and insulin resistance.

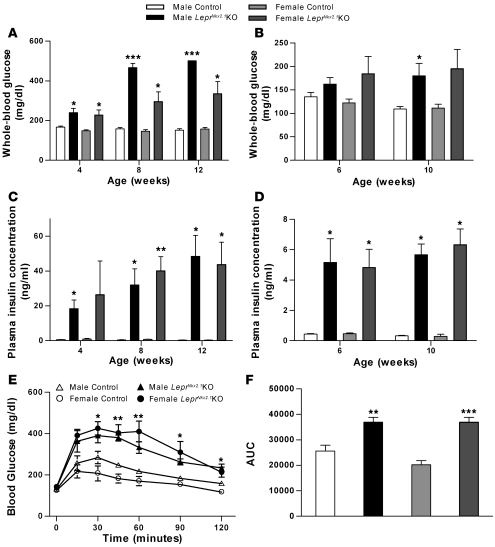

We also assessed phenotypes related to glucose homeostasis. As early as 4 weeks, there was a small but significant difference between random-fed whole-blood glucose levels in sex-matched groups (Figure 8A). Significant differences in random-fed blood glucose persisted at 8 and 12 weeks. Fasted whole-blood glucose was somewhat different. At 6 weeks, there was no significant difference between control and LeprNkx2.1KO groups. At 10 weeks, fasting blood glucose achieved a significant difference between male, but not female, control and LeprNkx2.1KO groups (Figure 8B).

Figure 8. Impaired glucose homeostasis in LeprNkx2.1KO mice.

(A) Random-fed whole-blood glucose of LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice at several time points. (B) Fasted whole-blood glucose of LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice at 6 and 10 weeks. (C) Random-fed plasma insulin, as measured by ELISA, of LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice at 4, 8, and 12 weeks. (D) Fasted plasma insulin, as measured by ELISA, of LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice at 6 and 10 weeks. (E) GTT of LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice at 5 weeks of age. 2 mg/kg dextrose was injected i.p. at time 0. (F) Area under the curve calculation of GTT at 5 weeks of age. (A–F) n ≥ 5 for all groups at all points. Results are mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001. P values were calculated between age- and sex-matched groups.

Differences in plasma insulin were evident between control and LeprNkx2.1KO groups from a very early age (Figure 8C). At 4 weeks, there was a significant difference in fed-state serum insulin in males; although no significant difference was found in females at 4 weeks, this was due to the wide range in plasma insulin of knockout females (4.2–65.1 ng/ml) versus that for controls (0.4–2.5 ng/ml). At all other time points and conditions tested (8 and 12 weeks random fed; 6 and 10 weeks fasted), LeprNkx2.1KO animals exhibited higher plasma insulin levels than their sex-matched controls (Figure 8, C and D).

At 5 weeks of age, animals were subjected to a glucose tolerance test (GTT; Figure 8E). There was no difference in fasted whole-blood glucose between groups at time 0; however, compared with sex-matched controls, LeprNkx2.1KO mice showed significantly higher blood glucoses at all time points after 15 minutes. Differences in glucose tolerance between sex-matched groups were confirmed with area under the curve analysis of the GTT (Figure 8F).

Discussion

Collective actions of leptin-sensing neurons throughout the CNS influence a wide range of phenotypes related to energy homeostasis (43, 44). Experiments to acutely modulate energy balance by i.c.v. injections of leptin or regulators of signaling pathways downstream of leptin have implicated the mediobasal hypothalamus as a primary mediator of leptin signaling (reviewed in ref. 45). Similarly, ablation of subpopulations of hypothalamic neurons in the adult result in dramatic alterations in behaviors related to energy homeostasis (46–48). However, efforts to disrupt leptin signaling in subpopulations of hypothalamic neurons from birth have generally led to mild phenotypes (23–25, 46). These observations are consistent with the hypothesis that the capacity to compensate for deficits in components of the leptin-sensing circuits is largely restricted to immature animals.

Adaptations in circuits transmitting other peptidergic signals are not sufficient to correct for the congenital loss of leptin signals in Lepob/ob and Leprdb/db mice, consistent with the hypothesis that at least some of the compensatory capacity lies within the population of leptin-sensing neurons. As leptin-sensing neurons in the hypothalamus are highly interconnected, these neurons are well positioned to provide adaptive responses to localized disruptions of leptin signaling within this dense neuronal network. In addition to the hypothalamus, neurons in the VTA and brainstem also modulate food intake and energy homeostasis phenotypes, and thus represent another potential source of network plasticity (27–30). We used the LeprNkx2.1KO mouse model to ascertain whether the actions of leptin-sensing neurons in the caudal CNS are sufficient to compensate for an early loss of hypothalamic leptin signaling. Metabolic phenotypes of LeprNkx2.1KO mice from weaning through adulthood were assessed and compared with those of mouse models involving global disruption of leptin signaling, including Leprdb/db (Figures 3–7), LeprΔ17 (33), and s/s (49). It should be noted that the Leprdb/db mice are on a C57BL/6 background (compared with a mixed C57BL/6 × FVB/NJ background for the LeprNkx2.1KO) and were imported directly from Jackson Laboratories; both factors could influence the severity of metabolic phenotypes. Therefore, we have focused our comparisons of LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice versus Leprdb/db mice on changes in the progression of phenotypes from 7 weeks of age to adulthood.

Metabolic phenotypes of LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db mice were similar in postweaning mice, but diverged with maturity. We found that the adiposity, food intake, energy expenditure, and glucose homeostasis phenotypes of 7-week-old LeprNkx2.1KO mice closely resembled those of Leprdb/db animals. Whereas adiposity levels continued to escalate in mature Leprdb/db males (47.2% at 12 weeks; Figure 3C) and LeprΔ17 animals (49.7% at 16 weeks; ref. 41), both male and female LeprNkx2.1KO mice maintained stable, but elevated, adiposity levels from 8 weeks of age (males, 37%; females, 43%). After 8 weeks of age, LeprNkx2.1KO males and females exhibited an increased rate of linear growth and increased accrual of lean mass relative to control and Leprdb/db animals (Figure 3B and Figure 4B). In adult males, several phenotypes related to energy expenditure, including metabolic rate, locomotor activity, and acute cold tolerance, were not significantly different between LeprNkx2.1KO and control mice; deficits in these functions persisted in Leprdb/db animals (Figure 5C and Figure 6, A and B). Phenotypes related to food intake, glucose homeostasis, baseline CORT, and fertility were not statistically different between LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db animals at all ages examined (Figure 4C, Figure 7A, Figure 8, A–F, Table 1, and data not shown).

These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that the hypothalamus is essential to mediate leptin’s effects on phenotypes related to energy homeostasis in young mice, but with increasing age, the functions of other neuronal networks act to prevent the escalation of adiposity phenotypes observed in global leptin signaling mutants. The phenotypes that differ between mature LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db animals — linear growth, oxygen consumption, locomotor activity, and cold tolerance — likely contribute to the increased energy expenditure in LeprNkx2.1KO animals, and thus may underlie the defense of constant adiposity levels. Based on these observations, we propose that circuits that modulate growth, thermoregulation, locomotor activity, and metabolic rate are likely sources of compensatory signals that act to stabilize adiposity levels after 8 weeks of age. Potential sources of compensatory actions include: (a) leptin-sensing neurons that do not express the Nkx2.1-Cre driver (i.e., largely, but not exclusively, extrahypothalamic), (b) leptin signaling not transduced through LEPR exon 17 (50, 51), and (c) leptin-independent signals. These findings raise the possibility that there are significant differences in the way that neuronal networks interact to regulate energy homeostasis across developmental time periods. Analyses of LeprNkx2.1KO phenotypes in the context of published models involving deficits in leptin signaling are presented below.

Somatic growth and body composition.

Lepob/ob and Leprdb/db mice are characterized by increased fat deposition at the expense of somatic growth, but LeprNkx2.1KO mice exhibited increased naso-anal length and early-onset obesity (Figure 3). The remarkable body lengths exhibited by LeprNkx2.1KO mice (11.4 vs. 10.5 cm and 11.9 vs. 10.1 cm in 20-week-old males and females, respectively; Figure 3B) likely reflect the combined interaction of the mutant genotype and FVB/NJ background. Increased naso-anal lengths (more so in females) have also been reported in mouse models of impaired melanocortin signaling (52, 53). Activation of the growth axis can be attributed to 2 types of signals, which are not mutually exclusive. Melanocortin-independent leptin signaling pathways that are not disrupted in the LeprNkx2.1KO model may be activated as a result of hyperleptinemia. It is also possible that leptin-independent pathways that are activated as a secondary consequence of increased adiposity are responsible for the growth phenotype.

LeprNkx2.1KO mice deposited higher levels of body fat until 8 weeks, at which point adiposity levels plateaued (males, 37%; females, 43%; Figure 3, C and D); this contrasted with escalating levels in adult Leprdb/db and LeprΔ17 animals (Figure 3C and ref. 41). Although not explicitly addressed, adiposity in models involving a disruption of leptin or PI3K signaling in subsets of ARH neurons result in increased adiposity levels that do not substantially escalate in adults (23, 25, 54). These findings support the hypothesis that hypothalamic leptin signals play an essential role in establishing baseline levels of adiposity in young animals that are subsequently defended by the actions of other neuronal circuits.

Food intake.

Leptin’s effects on food intake are likely mediated through the integration of outputs from PI3K, STAT3, and ERK signaling pathways (55–60). Whereas initial studies of the central regulation of food intake were focused on the hypothalamus, a growing body of evidence supports an important role for extra-hypothalamic neuronal populations, most notably in the midbrain and brainstem, in mediating leptin’s effects on feeding behaviors (reviewed in ref. 61). LeprNkx2.1KO mice provide a useful tool to identify those aspects of food intake phenotypes that require hypothalamic leptin signaling. LeprNkx2.1KO mice exhibited hyperphagia from weaning; daily food intake increased between 3 and 6 weeks of age, after which point the absolute amount of food consumed remained relatively constant through the adult period (controls, 3.7 ± 0.4 g/d; LeprNkx2.1KO, 6.5 ± 0.7 g/d; Figure 4A). When food intake was normalized to lean mass, the hyperphagic phenotype of LeprNkx2.1KO mice dissipated over time such that by 12 weeks, normalized food intake was only 28% higher in LeprNkx2.1KO over control mice (compared with 51% at 4 weeks; Figure 4C). However, at 7, 10, and 12 weeks, there were no significant differences between absolute and normalized food intake measurements in LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db animals. These findings are consistent with the hypothesis that hypothalamic leptin signaling is a major determinant of food intake levels.

Energy expenditure.

Leptin influences energy expenditure by effects on several parameters, including metabolic rate, thermogenesis, locomotor activity, and level of sympathetic tone (62). We found that absolute and normalized measures of oxygen consumption were similar in all groups examined at 3 weeks. Whereas the normalized metabolic rates of LeprNkx2.1KO and control animals were similar in adults, Leprdb/db animals were hypometabolic (Figure 5B). In contrast to severe impairments in cold tolerance exhibited by Leprdb/db and LeprΔ17 mice (33), all but the youngest postweaning LeprNkx2.1KO mice were capable of mounting a normal response to cold. Locomotor activity in LeprNkx2.1KO animals, as assessed by beam breaks, was at an intermediate level between control and Leprdb/db animals, but did not significantly differ from either (Figure 5C). The absence of a significant deficit in locomotor activity can be explained by 2 possibilities, which are not mutually exclusive: (a) spontaneous hyperactivity reported in FVB/NJ mice may mask a genetic impairment (63); and (b) although leptin signaling in POMC neurons or ARH neurons may be sufficient to rescue deficits in the locomotor activity of Leprdb/db animals (22, 64), it is possible that leptin signaling in neurons that do not express the Nkx2.1-Cre transgene is also sufficient to rescue locomotor activity. Together, these observations strongly suggest a primary role for hypothalamic leptin-mediated signals in regulating phenotypes related to energy expenditure in the postweaning period. With maturity, the functions of leptin-sensing circuits that are not impaired in the LeprNkx2.1KO model may act to stabilize the level of adiposity achieved at 8 weeks of age by increasing total energy expenditure.

Hypothalamic leptin resistance is sufficient to elicit neuroendocrine responses associated with the fasted state.

Systemic leptin resistance in Leprdb/db mice, and thus the inability to appropriately sense leptin-mediated signals of energy surplus, is thought to underlie adaptations in the adrenal, thyroid, and gonadal axes that resemble the starved state (65). CORT levels were elevated in LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db adults (Figure 7A), consistent with the idea that hypothalamic neurons are required to mediate leptin’s effects on the adrenal axis. Activity of the thyroid axis was reduced in both LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db animals (Figure 7B and ref. 62). However, as Nkx2.1-Cre is also expressed in the thyroid, we are not able to distinguish between contributions caused by defects in leptin signaling within the hypothalamus and/or thyroid. The observation that s/s mice are fertile suggests that STAT3-mediated leptin signals are not responsible for reproductive deficits in Leprdb/db animals (49). Together with the finding that neuronal expression of Lepr can rescue fertility in Leprdb/db mice (14), our data support the idea that STAT3-independent leptin signaling in the hypothalamus is critical for fertility in both males and females. The neuroendocrine phenotypes of LeprNkx2.1KO mice closely resembled those of Leprdb/db animals, despite the ability of neurons in the caudal CNS to transduce leptin signals in an environment of chronic hyperleptinemia (Figure 1A and Figure 2D). These data support the idea that leptin resistance in the hypothalamus of Leprdb/db animals underlies many changes in adrenal, thyroid, and gonadal axes that mimic the fasted state.

Glucose homeostasis.

Leptin signaling through the STAT3 and PI3K pathways has been implicated in leptin-mediated regulation of glucose homeostasis; Cre-mediated recombination of the Leprfl allele is predicted to disrupt signaling through both pathways (23, 33). Restoration of Lepr expression in subsets of ARH neurons ameliorates glucose homeostasis (14, 22, 64, 66). Based on these observations, we anticipated that disruption of hypothalamic leptin signaling would result in disturbed glucose homeostasis. We found that LeprNkx2.1KO mice exhibited hyperinsulinemia and hyperglycemia at 4 weeks and impaired GTT at 5 weeks. The persistent hyperglycemia in LeprNkx2.1KO mice is likely attributable to the interaction of the LeprΔ17 mutation with the FVB/NJ background, as Leprdb/db mice on a C57BL/6J background are only mildly hyperglycemic (67, 68). Although strain differences preclude direct comparisons between the absolute insulin and glucose values, the early onset of hyperglycemia, hyperinsulinemia, and impaired GTT in LeprNkx2.1KO and Leprdb/db mice and the observation that serum insulin levels are the same in LeprHypΔ17, LeprΔ17, and Leprdb/db mice provide strong evidence that the hypothalamus is the principal site of leptin-mediated regulation of glucose homeostasis in the postnatal period (33, 41, 69). Normal glucose homeostasis in s/s mice indicates that STAT3-mediated leptin signals are not essential for this function (70). Alternatively, the PI3K pathway has been implicated in mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis (66). Together with these studies, our present data are consistent with a model in which hypothalamic leptin signaling through PI3K-dependent pathways is critical. These data cannot rule out the possibility that other leptin-sensing cells contribute to glucose regulation, but their function is not sufficient to overcome the insulin resistance secondary to the severe obesity found in LeprNkx2.1KO mice.

Implications for research in childhood obesity.

As the prevalence of childhood obesity has risen worldwide, so have the risks of associated medical conditions, such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. To date, strategies to treat childhood obesity remain largely ineffective. Epidemiological studies have shown that patterns of increased food intake and adiposity in overweight children are predictive of adult obesity, and thus lend urgency to the need for novel approaches to combat the obesity epidemic in children. Research efforts in the past several decades have identified many signals and cellular components of neuronal circuits that regulate food intake and body weight; however, the vast majority of these studies have been performed in mature animals. Our analyses of physiological functions in LeprNkx2.1KO mice revealed a dramatic temporal shift in the progression of phenotypes related to somatic growth, adiposity, and energy expenditure. Young LeprNkx2.1KO mice exhibited phenotypes similar to mice with systemic loss of leptin signals; in mature animals, several parameters related to somatic growth and energy expenditure were increased, and adiposity levels did not escalate. The maintenance of constant adiposity levels throughout adulthood raises the possibility that the capacity for adaptations in circuits regulating growth and energy expenditure may function not only in defense of baseline adiposity levels in LeprNkx2.1KO animals, but under normal physiological conditions as well. These observations are consistent with the idea that the regulation of phenotypes related to energy homeostasis may be different (and less complex) in immature animals. If this notion proves true, manipulations of critical components of circuits that establish metabolic profiles in young animals would represent a promising strategy to combat childhood obesity.

Methods

Generation of LeprNkx2.1KO mice.

Hypothalamus-specific recombination of a floxed allele of Lepr was carried out by crossing Leprfl/fl FVB/NJ (33) females, provided by S. Chua (Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York, New York, USA), with male Nkx2.1-Cre mice, provided by S. Anderson (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York, USA) on a C57BL/6 background (32). F1 heterozygotes (Nkx2.1-Cre;Leprfl/–) were intercrossed, yielding LeprNkx2.1KO as well as Leprfl/fl control mice in the expected Mendelian ratios. Mouse genotypes were assessed by PCR on genomic DNA from tail tips using the following primers: Cre recombinase, GCGGTCTGGCAGTAAAAACTATC (forward) and GTGAAACAGCATTGCTGTCACTT (reverse); LEPR WT or flox multiplex set, GTCTGATTTGATAGATGGTCTT (forward), AGAATGAAAAAGTTGTTTTGGGA (forward), and GGCTTGAGAACATGAACAC (reverse).

Animal husbandry.

Mice were maintained in a temperature- and light-controlled environment (22°C ± 1°C; 12-hour light/12-hour dark cycle). Except where noted, mice were housed in sex-matched groups of 2–4 with at least 1 LeprNkx2.1KO and 1 control animal per cage. Pregnant and nursing mice were housed no more than 2 dams per cage. Pups were weaned on postnatal day 21. Unless otherwise noted, mice had ad libitum access to chow (9% calories from fat, 5058 Mouse diet 20; Labdiet) and water until the time of sacrifice. Leprdb/db C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Jackson Labs. All procedures were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Columbia University Health Sciences Division.

Fertility assessment.

1 or 2 female mice were housed with 1 male mouse for at least 45 days or until pregnancy was obvious in females, at which point the male was removed from the cage. Delivery date (measured as days after original set) and number of pups delivered were noted as applicable.

Preservation of organ specimens.

At the time of sacrifice, animals were randomly divided into 2 groups: those to be perfused for brain preservation, and those not to be perfused. In the nonperfused groups, animals were anesthetized with 2.5% Avertin, 0.02 ml/g i.p., before cervical dislocation. BAT was dissected and preserved in Allprotect tissue reagent (Qiagen). In the perfused group, animals were transcardially perfused with saline followed by 4% PFA in phosphate buffer (PB). Brains were postfixed in 4% PFA in PB at 4°C for 3 hours, cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PB, and embedded in OCT medium and frozen at –80°C until time of section. Animals to be used in LEPR functional analysis studies were fasted overnight, and in the morning were injected with either recombinant mouse leptin (4 mg/kg i.p., provided by A.F. Parlow, National Hormone and Peptide Program, Torrance, California, USA) or PBS (8 μl/g) 30 minutes before sacrifice and perfusion as above.

Histological analysis.

All frozen tissue tissues were sectioned at 10 μm. BAT was stained with H&E or with Oil O red. To identify LacZ-positive cells, perfused brain sections were washed in 1× PBS plus 2 mM MgCl2, 0.001% sodium deoxycholate, and 0.02% NP-40 buffer and incubated at room temperature overnight in a solution of buffer, 5 mM each potassium ferricyanide and potassium ferrocyanide, 20 mM Tris, and 1 mg/ml X-gal. For p-STAT3 immunohistochemistry, sections were sequentially pretreated with 1% NaOH with 1% H2O2 solution, 0.3% glycine, and 0.3% SDS, and blocked in 1.5% horse serum and 0.1% Triton-X before being incubated at 4°C overnight in the primary antibody (rabbit anti-pSTAT3, diluted 1:800; Cell Signaling). After PBS wash, slides were incubated with secondary antibody (HRP-conjugated bovine anti-rabbit, diluted 1:500; Santa Cruz Biotech), before being washed and developed with tyramide-Cy3 (Perkin Elmer).

Analysis of growth and body composition.

Beginning at weaning, mice were weighed weekly. To measure length, mice were anesthetized, and their naso-anal length was quantified with a digital caliper. To determine body composition, mice were subjected to nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (Bruker the Minispec) at 3, 5, 7, 8, 10, and 12 weeks of age.

Measurement of glucose, insulin, leptin, T4, and CORT.

Unless otherwise noted, all blood samples were collected between 10 am and noon. Fasting blood samples were taken following 14–16 hours of fasting with ad libitum access to drinking water. Whole blood for glucose levels was taken via tail nick and assayed using a glucometer with disposable test strips (Abbott). The upper limit of measurement was 500 mg/dl; any “HI” readings were recorded as 501 mg/dl. Plasma for insulin and leptin assessment was collected via orbital sinus puncture on isoflurane-anesthetized animals. Blood was collected into heparinized tubes and stored on ice before being centrifuged; plasma was decanted and stored at –20°C until used in leptin (Millipore) or insulin (Mercodia) ELISA, per the manufacturer’s protocol. With a 10× dilution, the upper limit of detection of plasma insulin was 65 ng/ml; all samples falling above the upper limit were recorded as 65.1 ng/ml. Serum for T4 was collected via eye bleed on isoflurane- or Avertin-anesthetized animals in unheparinized tubes and allowed to clot before being centrifuged, decanted, and stored at –20°C until used in T4 RIA (Siemens). Serum for CORT was collected from tail bleeds on minimally stressed animals at 10 am. Serum was processed as above and analyzed for CORT content via RIA (MP Biomedicals) in the laboratory of S. Wardlaw (Columbia University, New York, New York, USA).

GTT.

Mice were allowed ad libitum access to drinking water, but were fasted for a period of 14–16 hours before commencement of GTT at 10 am. Whole-blood glucose level was assessed as above immediately before a given mouse received a 2 g/kg i.p. bolus of dextrose. Whole-blood glucose was assayed via tail nick at 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after injection.

Cold challenge.

Short-term cold challenge was assayed on male 3-, 6-, and 14- to 16-week-old mice at 10 am as described previously (62). Following the cold stress, animals were removed from further metabolic analyses.

Indirect calorimetry, locomotor activity, and food intake.

Male mice aged 3, 7–8, and 14–16 weeks were acclimated to respiratory chambers for 24 hours before measurements. Oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, food intake, and locomotor activity were measured simultaneously over a 72-hour period using a 16-cage Indirect Calorimetry System combined with Feeding Monitor and TSE ActiMot system (TSE-Systems). Oxygen consumption and carbon dioxide production were measured using a paramagnetic O2 sensor and a spectrophotometric CO2 sensor, respectively, over a 24-hour period. A photobeam-based activity monitoring system detected and recorded every ambulatory movement.

Semiquantitative RT-PCR.

Total RNA was isolated from BAT that had been stored in Allprotect tissue reagent using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was achieved using transcriptor first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Roche). Quantitative PCR was done on a LightCycler (Roche) using the LightCycler FastStart DNA master SYBR Green I. Levels for Ucp1 (forward, GTGAAGGTCAGAATGCAAGC; reverse, AGGGCCCCCTTCATGAGGTC) were normalized against 18s (forward, CCGCAGCTGGAATAATGGA; reverse, CCCTCTTAATCATGGCCTCA).

Statistics.

Data are presented as group mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were performed between sex-matched groups using 2-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test or 1-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-hoc analysis. A P value of 0.05 or less was considered to be statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Columbia Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center Pathology Core for cryosectioning and the Animal Phenotyping Core for help with metabolic cages (DK52431-16). We also thank Rudy Leibel, Sharon Wardlaw, and Stephanie Padilla of Columbia University for critically reading this manuscript and providing helpful suggestions. This work was supported by NIH grant T32 GM008464-17 (to L.E. Ring) and by the Russ Berrie Foundation (to L.M. Zeltser).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Citation for this article: J Clin Invest. 2010;120(8):2931–2941. doi:10.1172/JCI41985.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popkin BM. Recent dynamics suggest selected countries catching up to US obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(1):284S–288S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28473C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372(6505): 425–432. doi: 10.1038/372425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maffei M, et al. Leptin levels in human and rodent: measurement of plasma leptin and ob RNA in obese and weight–reduced subjects. Nat Med. 1995;1(11):1155–1161. doi: 10.1038/nm1195-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tartaglia LA, et al. Identification and expression cloning of a leptin receptor, OB–R. Cell. 1995;83(7):1263–1271. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen H, et al. Evidence that the diabetes gene encodes the leptin receptor: identification of a mutation in the leptin receptor gene in db/db mice. Cell. 1996;84(3):491–495. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81294-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman DL. Obese and diabetes: two mutant genes causing diabetes–obesity syndromes in mice. Diabetologia. 1978;14(3):141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF00429772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halaas JL, et al. Weight–reducing effects of the plasma protein encoded by the obese gene. Science. 1995;269(5223):543–546. doi: 10.1126/science.7624777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelleymounter MA, et al. Effects of the obese gene product on body weight regulation in ob/ob mice. Science. 1995;269(5223):540–543. doi: 10.1126/science.7624776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chua SC, Jr, et al. Phenotypes of mouse diabetes and rat fatty due to mutations in the OB (leptin) receptor. Science. 1996;271(5251):994–996. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campfield LA, Smith FJ, Guisez Y, Devos R, Burn P. Recombinant mouse OB protein: evidence for a peripheral signal linking adiposity and central neural networks. Science. 1995;269(5223):546–549. doi: 10.1126/science.7624778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seeley RJ, et al. Intraventricular leptin reduces food intake and body weight of lean rats but not obese Zucker rats. Horm Metab Res. 1996;28(12):664–668. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-979874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen P, et al. Selective deletion of leptin receptor in neurons leads to obesity. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(8):1113–1121. doi: 10.1172/JCI13914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Luca C, et al. Complete rescue of obesity, diabetes, and infertility in db/db mice by neuron–specific LEPR–B transgenes. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(12):3484–3493. doi: 10.1172/JCI24059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elmquist JK, Bjørbaek C, Ahima RS, Flier JS, Saper CB. Distributions of leptin receptor mRNA isoforms in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;395(4):535–547. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980615)395:4<535::AID-CNE9>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leshan RL, Björnholm M, Münzberg H, Myers MG., Jr Leptin receptor signaling and action in the central nervous system. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(suppl 5):208S–212S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hetherington AW, Ranson SW. Hypothalamic lesions and adiposity in the rat. Anat Rec. 1940;78(2):149–172. doi: 10.1002/ar.1090780203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anand BK, Brobeck JR. Localization of a feeding center in the hypothalamus of the rat. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1951;77(2):323–324. doi: 10.3181/00379727-77-18766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debons AF, Krimsky I, Maayan ML, Fani K, Jemenez FA. Gold thioglucose obesity syndrome. Fed Proc. 1977;36(2):143–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lorden JF, Caudle A. Behavioral and endocrinological effects of single injections of monosodium glutamate in the mouse. Neurobehav Toxicol Teratol. 1986;8(5):509–519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton GJ, et al. Arcuate nucleus–specific leptin receptor gene therapy attenuates the obesity phenotype of Koletsky (fa(k)/fa(k)) rats. Endocrinology. 2003;144(5):2016–2024. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coppari R, et al. The hypothalamic arcuate nucleus: a key site for mediating leptin’s effects on glucose homeostasis and locomotor activity. Cell Metab. 2005;1(1):63–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balthasar N, et al. Leptin receptor signaling in POMC neurons is required for normal body weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2004;42(6): 983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dhillon H, et al. Leptin directly activates SF1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body–weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;49(2):191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van de Wall E, et al. Collective and individual functions of leptin receptor modulated neurons controlling metabolism and ingestion. Endocrinology. 2008;149(4):1773–1785. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grill HJ. Distributed neural control of energy balance: contributions from hindbrain and hypothalamus. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2006;14(suppl 5):216S–221S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes MR, et al. Endogenous leptin signaling in the caudal nucleus tractus solitarius and area postrema is required for energy balance regulation. Cell Metab. 2010;11(1):77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yadav VK, et al. A serotonin–dependent mechanism explains the leptin regulation of bone mass, appetite, and energy expenditure. Cell. 2009;138(5):976–989. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fulton S, et al. Leptin regulation of the mesoaccumbens dopamine pathway. Neuron. 2006;51(6):811–822. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hommel JD, et al. Leptin receptor signaling in midbrain dopamine neurons regulates feeding. Neuron. 2006;51(6):801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leinninger GM, et al. Leptin acts via leptin receptor–expressing lateral hypothalamic neurons to modulate the mesolimbic dopamine system and suppress feeding. Cell Metab. 2009;10(2):89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu Q, Tam M, Anderson SA. Fate mapping Nkx2.1–lineage cells in the mouse telencephalon. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506(1):16–29. doi: 10.1002/cne.21529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMinn JE, et al. An allelic series for the leptin receptor gene generated by CRE and FLP recombinase. Mamm Genome. 2004;15(9):677–685. doi: 10.1007/s00335-004-2340-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bray GA, York DA. Hypothalamic and genetic obesity in experimental animals: an autonomic and endocrine hypothesis. Physiol Rev. 1979;59(3):719–809. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1979.59.3.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizuno K, Gonzalez FJ, Kimura S. Thyroid–specific enhancer–binding protein (T/EBP): cDNA cloning, functional characterization, and structural identity with thyroid transcription factor TTF–1. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11(10):4927–4933. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.10.4927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sussel L, Marin O, Kimura S, Rubenstein JL. Loss of Nkx2.1 homeobox gene function results in a ventral to dorsal molecular respecification within the basal telencephalon: evidence for a transformation of the pallidum into the striatum. Development. 1999;126(15):3359–3370. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.15.3359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soriano P. Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet. 1999;21(1):70–71. doi: 10.1038/5007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith JT, Acohido BV, Clifton DK, Steiner RA. KiSS–1 neurones are direct targets for leptin in the ob/ob mouse. J Neuroendocrinol. 2006;18(4):298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01417.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vaisse C, Halaas JL, Horvath CM, Darnell JE, Jr, Stoffel M, Friedman JM. Leptin activation of Stat3 in the hypothalamus of wild–type and ob/ob mice but not db/db mice. Nat Genet. 1996;14(1):95–97. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Butler AA, Kozak LP. A recurring problem with the analysis of energy expenditure in genetic models expressing lean and obese phenotypes. Diabetes. 2010;59(2):323–329. doi: 10.2337/db09-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McMinn JE, et al. Neuronal deletion of Lepr elicits diabesity in mice without affecting cold tolerance or fertility. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289(3):E403–E411. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00535.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bray GA. Endocrine disturbances and reduced sympathetic activity in the development of obesity. Infusionstherapie. 1990;17(3):124–130. doi: 10.1159/000222462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morton GJ, Cummings DE, Baskin DG, Barsh GS, Schwartz MW. Central nervous system control of food intake and body weight. Nature. 2006;443(7109):289–295. doi: 10.1038/nature05026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bates SH, Myers MG. The role of leptin––>STAT3 signaling in neuroendocrine function: an integrative perspective. J Mol Med. 2004;82(1):12–20. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0494-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams KW, Scott MM, Elmquist JK. From observation to experimentation: leptin action in the mediobasal hypothalamus. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(3):985S–990S. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26788D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Luquet S, Perez FA, Hnasko TS, Palmiter RD. NPY/AgRP neurons are essential for feeding in adult mice but can be ablated in neonates. Science. 2005;310(5748):683–685. doi: 10.1126/science.1115524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gropp E, et al. Agouti–related peptide–expressing neurons are mandatory for feeding. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(10):1289–1291. doi: 10.1038/nn1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bewick GA, et al. Post–embryonic ablation of AgRP neurons in mice leads to a lean, hypophagic phenotype. FASEB J. 2005;19(12):1680–1682. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3434fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bates SH, et al. STAT3 signalling is required for leptin regulation of energy balance but not reproduction. Nature. 2003;421(6925):856–859. doi: 10.1038/nature01388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bjorbaek C, et al. Divergent roles of SHP–2 in ERK activation by leptin receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(7):4747–4755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kloek C, Haq AK, Dunn SL, Lavery HJ, Banks AS, Myers MG., Jr Regulation of Jak kinases by intracellular leptin receptor sequences. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(44):41547–41555. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205148200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolff GL. Growth of inbred yellow (Aya) and non–yellow (Aa) mice in parabiosis. Genetics. 1963;48:1041–1058. doi: 10.1093/genetics/48.8.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huszar D, et al. Targeted disruption of the melanocortin–4 receptor results in obesity in mice. Cell. 1997;88(1):131–141. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81865-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Belgardt BF, et al. PDK1 deficiency in POMC–expressing cells reveals FOXO1–dependent and –independent pathways in control of energy homeostasis and stress response. Cell Metab. 2008;7(4):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Niswender KD, Morton GJ, Stearns WH, Rhodes CJ, Myers MG, Jr, Schwartz MW. Intracellular signalling. Key enzyme in leptin–induced anorexia. Nature. 2001;413(6858):794–795. doi: 10.1038/35101657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bates SH, Myers MG., Jr The role of leptin receptor signaling in feeding and neuroendocrine function. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003;14(10):447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buettner C, Pocai A, Muse ED, Etgen AM, Myers MG, Jr, Rossetti L. Critical role of STAT3 in leptin’s metabolic actions. Cell Metab. 2006;4(1):49–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rahmouni K, Sigmund CD, Haynes WG, Mark AL. Hypothalamic ERK mediates the anorectic and thermogenic sympathetic effects of leptin. Diabetes. 2009;58(3):536–542. doi: 10.2337/db08-0822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Skibicka KP, Grill HJ. Hindbrain leptin stimulation induces anorexia and hyperthermia mediated by hindbrain melanocortin receptors. Endocrinology. 2009;150(4):1705–1711. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hayes MR, Skibicka KP, Bence KK, Grill HJ. Dorsal hindbrain 5′–adenosine monophosphate–activated protein kinase as an intracellular mediator of energy balance. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2175–2182. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Myers MG, Jr, Münzberg H, Leinninger GM, Leshan RL. The geometry of leptin action in the brain: more complicated than a simple ARC. Cell Metab. 2009;9(2):117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bates SH, Dundon TA, Seifert M, Carlson M, Maratos-Flier E, Myers MG., Jr LRb–STAT3 signaling is required for the neuroendocrine regulation of energy expenditure by leptin. Diabetes. 2004;53(12):3067–3073. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.12.3067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Võikar V Kõks S, Vasar E, Rauvala H. Strain and gender differences in the behavior of mouse lines commonly used in transgenic studies. Physiol Behav. 2001;72(1–2):271–281. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(00)00405-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huo L, et al. Leptin–dependent control of glucose balance and locomotor activity by POMC neurons. Cell Metab. 2009;9(6):537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ahima RS, et al. Role of leptin in the neuroendocrine response to fasting. Nature. 1996;382(6588):250–252. doi: 10.1038/382250a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Morton GJ, Gelling RW, Niswender KD, Morrison CD, Rhodes CJ, Schwartz MW. Leptin regulates insulin sensitivity via phosphatidylinositol–3–OH kinase signaling in mediobasal hypothalamic neurons. Cell Metab. 2005;2(6):411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chua S, Jr, Liu SM, Li Q, Yang L, Thassanapaff VT, Fisher P. Differential beta cell responses to hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance in two novel congenic strains of diabetes (FVB– Lepr (db)) and obese (DBA– Lep (ob)) mice. Diabetologia. 2002;45(7):976–990. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0880-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haluzik M, et al. Genetic background (C57BL/6J versus FVB/N) strongly influences the severity of diabetes and insulin resistance in ob/ob mice. Endocrinology. 2004;145(7):3258–3264. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Le Marchand–Brustel Y, Jeanrenaud B. Pre– and postweaning studies on development of obesity in mdb/mdb mice. Am J Physiol. 1978;234(6):E568–E574. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.234.6.E568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bates SH, Kulkarni RN, Seifert M, Myers MG., Jr Roles for leptin receptor/STAT3–dependent and –independent signals in the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005;1(3):169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]