Abstract

The development of nanocrystal quantum dots (NQDs) with suppressed nonradiative Auger recombination has been an important goal in colloidal nanostructure research motivated by the needs of prospective applications in lasing devices, light emitting diodes, and photovoltaic cells. Here, we conduct single-nanocrystal spectroscopic studies of recently developed core-shell NQDs (so-called “giant” NQDs) that comprise a small CdSe core surrounded by a 16-monolayer-thick CdS shell. Using both continuous-wave and pulsed excitation, we observe strong emission features due both to neutral and charged biexcitons, as well as multiexcitons of higher order. The development of pronounced multiexcitonic peaks in steady-state photoluminescence of individual nanocrystals, as well as continuous growth of the emission intensity in the range of high pump levels, point toward a significant suppression of nonradiative Auger decay that normally renders multiexcitons nonemissive. The unusually high multiexciton emission efficiencies in these systems open interesting opportunities for studies of multiexciton phenomena using well-established methods of single-dot spectroscopy, as well as new exciting prospects for applications, that have previously been hampered by nonradiative Auger decay.

Introduction

Previous studies of carrier recombination dynamics in semiconductor nanocrystal quantum dots (NQDs) under intense pulsed excitation have shown that Auger decay is a general phenomenon that dominates multiexciton dynamics in these nanostructures, irrespective of composition, core/shell geometry, or shape in the case of elongated quantum rods (for review, see, e.g., refs. 1–3). This process is especially detrimental in lasing applications of nanocrystals, as it leads to very short, picosecond optical gain lifetimes.4–7 It also limits the performance of NQD-based light emitting diodes8,9 and photovoltaic cells10,11 because it introduces an additional recombination channel in charged nanoparticles.8 Thus, the development of Auger-recombination-free NQDs would greatly benefit a large number of emerging nanocrystal-based technologies.

Recently, we reported a new class of NQDs (termed “giant” NQDs or g-NQDs) that comprise a small CdSe core (3–4 nm diameter) encapsulated in a thick shell (10–19 monolayers) of a wider band gap CdS.12,13 Our initial spectroscopic studies of these structures indicated a significant improvement in photostability of g-NQDs compared to standard NQDs, as well as a much higher tolerance to harsh chemical and heat treatments. Additionally, these new nanostructures showed a significant suppression of photoluminescence (PL) intermittency (“blinking”) observed in single-dot measurements. A similar effect of blinking suppression was also observed in ref. 14, where similar structures were investigated.

PL intermittency is a well-documented property of colloidal NQDs (see, e.g., refs. 15–17). The transition from the emitting to the non-emitting state has usually been attributed to transfer of an electron or a hole to a trap outside of the nanoparticle.17–19 This process results in a charged nanocrystal, which is non-emissive because of fast Auger recombination of a photoexcited electron-hole pair via energy transfer to the pre-existing charge. Thus, the suppression of PL blinking observed in g-NQDs pointed towards reduction in the efficiency of Auger recombination and/or reduced likelihood of nanocrystal photocharging. Recently, we indeed observed a significant suppression of Auger decay in ensemble studies of g-NQDs where we directly monitored dynamics of single and biexciton emission.20 Based on these measurements, we inferred that the lower bound of the biexciton Auger decay time was 15 ns, which was ca. 75 times longer than in standard CdSe/ZnS nanocrystals possessing a similar emission wavelength. Long Auger decay times (10.5 ns) were also observed for charged excitons (trions) in thick-shell NQDs in single-nanocrystal studies.21 Furthermore, a suppression of Auger recombination was also recently reported for two other types of NQDs – CdTe/CdSe core/shell structures22 and CdZnSe/ZnSe nanocrystals possessing a radially graded alloy at the core/shell interface.23 In ref. 22, the conclusion of reduced Auger decay efficiency was made based on the observation of intense steady-state emission from multiexciton states in single-NQD studies, while in ref. 23 a similar conclusion was drawn on the basis of greatly reduced single-nanocrystal PL blinking.

Here, we present new evidence for significantly suppressed Auger decay in g-NQDs that is based on a large body of spectroscopic data obtained from single-dot measurements under both continuous-wave (cw) and pulsed excitation and for two different pump wavelengths (532 and 405 nm). Specifically, in contrast to single-dot PL spectra of standard NQDs, which show emission solely due to single excitons under cw excitation independent of pump level, high-pump-intensity g-NQD emission spectra are dominated by features due to biexcitons. Based on the spectral position of emission peaks, we conclude that the 532 nm pump (direct excitation of the CdSe core) results solely in neutral species, while the 405 nm pump (excitation of the CdS shell) can produce either neutral or charged excitations. We observe that both charged and neutral biexcitons, as well as charged excitons (trions), are highly emissive, and the corresponding emission peaks do not saturate at high pump levels. On the contrary, the PL signal of standard NQDs saturates as a result of fast Auger decay, which leads to suppression of emission from biexciton and charged states. Using intense pulsed excitation, we are even able to observe efficient emission from multiexcitons of higher order – 3 and above. Together, these results confirm a significant enhancement in multiexciton emission yields in g-NQDs compared to standard NQDs, which directly points toward greatly suppressed Auger recombination and an opportunity to utilize these newly developed nanostructures for the range of applications from efficient light emission to light harvesting.

Experimental

In this work, we focus on g-NQDs with a 3 nm CdSe core overcoated with 16 monolayers of CdS, which corresponds to shell thickness of ca. 5.6 nm. These nanocrystals were fabricated as described in ref. 12. For single-nanocrystal measurements, a dilute solution of g-NQDs was dispersed onto a crystalline quartz substrate (<0.5 NQD/μm2), which was then mounted in a continuous-flow liquid He cryostat. An inverted optical microscope with a 40X, 0.6 NA objective was used to image the sample onto the entrance slit of a 1/3 meter imaging spectrometer. PL spectra were collected using a liquid-nitrogen-cooled charge-coupled device. The integration time was up to 60 min at the lowest pump intensities. At high pump intensities, we acquired multiple spectra using a ca. one-minute acquisition time to ensure that the observed spectral features were not artifacts of spectral diffusion.

For measurements under cw radiation, we used either a frequency doubled Nd:YAG laser (532 nm emission wavelength) or a blue diode laser (405 nm emission wavelength). In experiments with pulsed excitation, we used a 405 nm, 300 ps pulsed diode laser operating at a 10 MHz repetition rate. PL dynamics were measured with 500 ps resolution via time correlated single photon counting. All measurements were conducted at 4 K.

Continuous wave 532 nm excitation

Observation of neutral biexcitons

Figure 1a shows the pump intensity dependent PL spectra of a typical individual nanocrystal measured using cw 532 nm excitation. The respective photon energy is below the absorption onset of the thick CdS shell, and therefore, it corresponds to the situation when charge carriers are photoinjected directly into the CdSe core. The pump intensities are indicated in terms of a normalized power, P, where P = 1 corresponds to the power density of 1 kW cm−2.

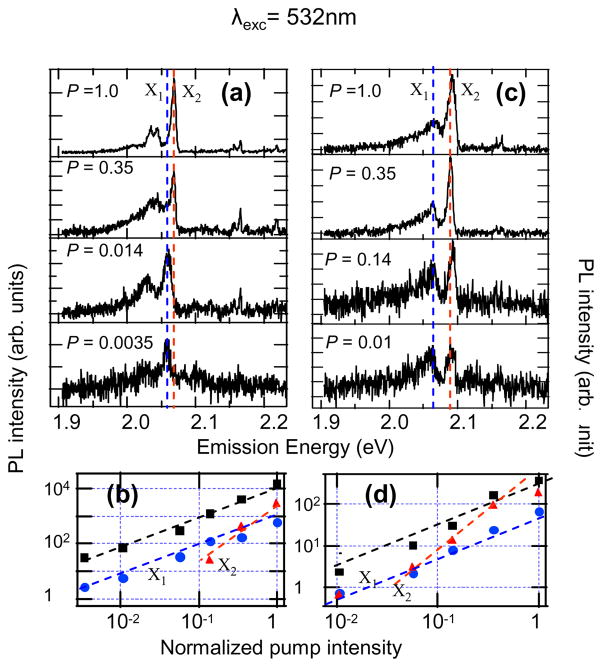

Figure 1.

PL spectra of two individual g-NQDs (‘a’ and ‘c’) measured at progressively increasing pump intensities (indicated in normalized units) of cw 532 nm excitation indicate a transition from single exciton (X1) to biexciton (X2) emission. The dependence of the amplitudes of these features on pump level is shown, respectively, in ‘b’ and ‘d’ (blue circles for X1 and red triangles for X2) together with the spectrally integrated PL signal (black squares).

The PL spectra measured at pump power P < 0.1 (two bottom spectra in Fig. 1a) comprise a main zero-phonon peak at 2.06 eV (X1) accompanied by a broad, lower-energy phonon replica. At P > 0.1, a new peak (X2) emerges at ~10 meV to the blue from the X1 feature. The intensity of the X2 peak quickly increases with pump power and it becomes a dominant PL feature at P > 0.3. We also observe a weaker phonon replica of the X2 band, which is composed of two peaks that correspond to CdS and CdSe longitudinal optical phonons (35 meV and 25 meV, respectively).

We further examine the pump-intensity dependence of the X1 and X2 peaks as well as the spectrally integrated PL signal (Fig. 1b). At P < 0.1, the amplitude of the X1 line scales linearly with pump power (blue circles in Fig. 1b). At pump levels above the onset for the development of the X2 feature (P > 0.1), the growth of the X1 peak becomes sub-linear, while the amplitude of the X2 band shows a quick quadratic growth (red triangles in Fig. 1b). Based on these observations, we can assign the X1 and X2 features to single excitons and biexcitons, respectively. Interestingly, across the whole pump power range studied in these measurements, the spectrally integrated PL intensity scales linearly with P (black squares in Fig. 1b), even well above the onset for biexciton emission. This behavior is in contrast to that observed for standard nanocrystals, where the PL signal quickly saturates at pump levels above the onset for multiexciton generation.24 Saturation is a result of fast nonradiative Auger decay, which dominates recombination dynamics of multiexcitons. The lack of such saturation in g-NQD samples together with the fact that the X2 band dominates the emission spectrum of these nanostructures at high pump levels clearly indicate that the biexciton decay in this case is primarily due to radiative processes and not Auger recombination.

In our studies with 532 nm excitation, we have measured more than 30 different g-NQDs. For all of them, at high pump intensities, we observe the development of the X2 peak, which is blue shifted with regard to the X1 feature. Furthermore, in all cases the X2 amplitude shows quadratic growth with increasing pump level (see the PL data set for one more g-NQD in Figs. 1c and d). The separation between the X2 and the X1 features varies from NQD to NQD (Fig. 2; histogram shown in red) and is on average 25 ± 5 meV (the uncertainty interval is given in terms of a standard deviation).

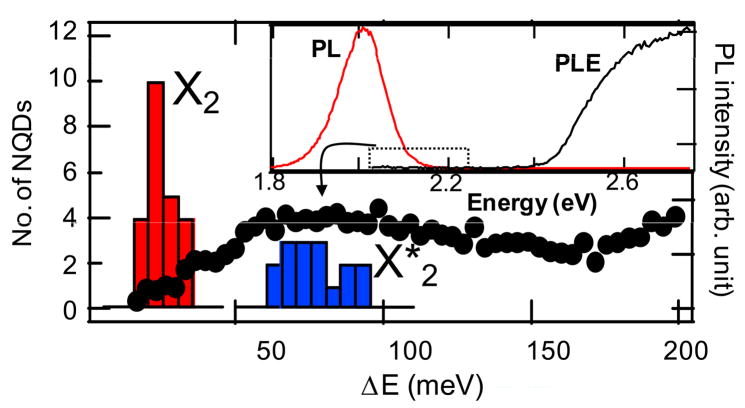

Figure 2.

Distributions of spectral shifts (ΔE) of the X2 vs. X1 band (histogram shown in red) and the X*2 vs. X*1 band (histogram shown in blue) derived from the analysis of the PL spectra of ~40 individual g-NQDs plotted in comparison to the expanded view of the ensemble PLE spectrum (black circles). The full ensemble PL and PLE spectra are shown in the inset.

The shift of the biexciton emission line relative to the single-exciton PL spectrum provides a measure of the exciton-exciton interaction energy, ΔXX. For core-only CdSe nanocrystals, the biexciton emission line is shifted to the red from the single-exciton band (ΔXX < 0), which corresponds to exciton-exciton attraction.24 The fact that in g-NQDs, the biexciton band is blue shifted with regard to the X1 feature is indicative of exciton-exciton repulsion. Our previous studies of exciton-exciton interactions in nanocrystals show that this effect is typical of systems with a significant difference in spatial distributions of electrons and holes (such as type-II nanocrystals), which breaks local charge quasi-neutrality.5, 25,26 In the case of g-NQDs, local imbalance between positive and negative charges develops as a result of a significant difference in localization regimes for electrons (delocalized over the entire g-NQD volume) and holes (confined to the core). Using formalism of ref. 26 for treating exciton-exciton interactions in core-shell nanocrystals, we obtain that for the parameters of g-NQDs studied here, ΔXX is ~30 meV. This value is in good agreement with the measured interaction energy of 25 ± 5 meV.

Continuous wave 405 nm excitation

Observation of trions and charged biexcitons

We have also studied single-g-NQD PL spectra using 405 nm excitation. This pump wavelength corresponds to photoinjection of carriers into the thick CdS shell, which provides a higher absorption cross section compared to 532 nm excitation (by a factor of 10-to-30 based on the ensemble absorption spectrum and direct comparison of a single g-NQD PL signal for 405 and 532 nm pump wavelengths) but also leads to increased likelihood of charge carrier escape from the nanocrystals to the interface states as discussed below.

For the 405 nm excitation, we observe two distinctly different behaviors in the measured PL spectra depending on the particular g-NQD. Some of the nanocrystals (type A g-NQDs; Figs. 3a and b) exhibit X1 and X2 spectral structures as well as pump-intensity-dependent trends that are similar to those observed for the 532 nm excitation (Fig. 4; top panel). In this case, however, we can monitor the evolution of the PL spectra across a wider range of pump powers. Specifically, with the 405 nm pump, we observe a nearly linear scaling of the spectrally integrated PL signal with P for the four-order-of-magnitude change in the excitation level (Fig. 3b). This confirms great reduction in the efficiency of nonradiative Auger recombination, which would normally lead to saturation of PL intensity at high pump levels.

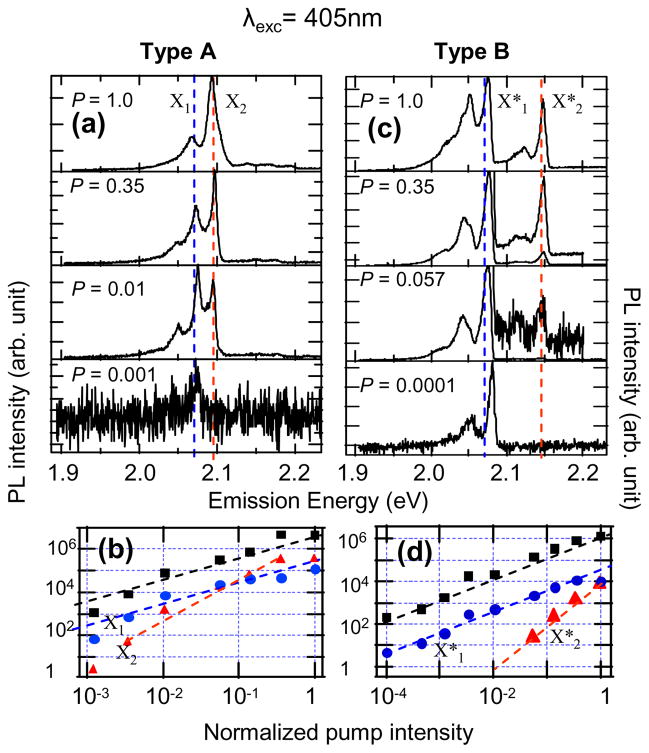

Figure 3.

PL spectra of two individual g-NQDs (‘a’ and ‘c’; the same dots as those in Figs. 1c and 1a, respectively) measured at progressively increasing pump intensities (indicated in normalized units) of cw 405 nm excitation that indicate two different types (A and B) of spectral features. The A-type g-NQD shows spectral peaks (in ‘a’) and PL pump-intensity dependences (in ‘b’) that are similar to those observed for cw 532 nm excitation and characteristic of emission from single excitons and biexcitons in neutral dots. The spectral features (in ‘c’) and pump-intensity dependences observed for the B-type g-NQD are consistent with emission from trions and charged biexcitons from charged nanocrystals.

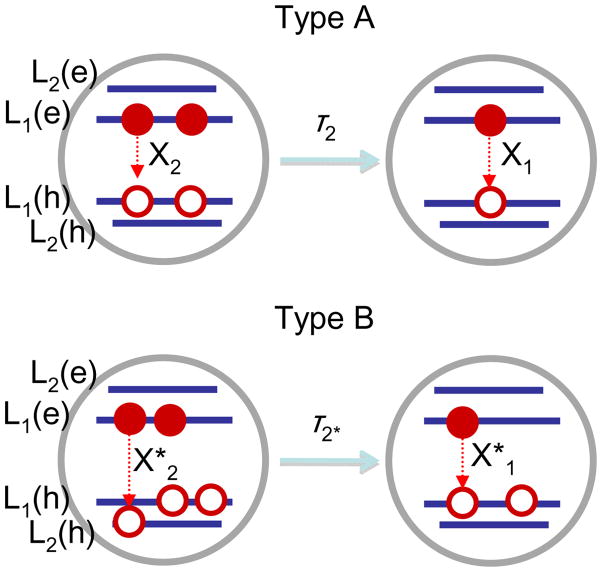

Figure 4.

Spectral features X2 and X1 in neutral (type-A) nanocrystals are due to emission from biexcitons and single excitons, respectively. The blue-shift of the X2 emission energy with regard to the X1 transition (not shown in the figure) is due to exciton-exciton repulsion, which develops in g-NQDs as a result of imbalance in spatial distributions of electron and hole wave functions. The decay constant of the biexciton (τ2) is likely defined solely by radaitive transitions. In charged (type-B) g-NQDs, photoexcited biexcitons (charged biexcitons) emit due to both the band-edge transition [L1(e) − L1(h)] and the transitions involving a higher energy state [L1(e) − L2(h); shown by the arrow]. In the figure, for the purpose of example, we show a dot which contains an excess hole; however, based on the available data we cannot indentify with certainty the sign of the charge residing in the nanocrystal. Based on measured pump-dependent PL intensity, the decay of the charged biexciton (time constant τ2*) is likely dominated by radiative processes.

Under 405 nm excitation, some of the nanocrystals (type B; Figs. 3c and d) display multiexciton PL spectra that are different from those measured using the 532 nm pump. Specifically, at P > 0.1, we detect a new peak, X*2, (accompanied by a weak phonon replica) which is blue shifted by ~75 meV from the low-pump-intensity X*1 feature. Simultaneously, we observe the increase in the amplitude of a low-energy shoulder of the X*1 line.

The appearance of the higher energy X*2 peak indicates that the observed emission is due to a multiexciton, which in addition to carriers in the lowest energy level (L1) involves at least one carrier (an electron or a hole) in the first excited state (L2) (Fig. 4; bottom panel). In the simple particle-in-the-box model, the maximum occupancy of the lowest-energy quantized levels is two. Therefore, the third carrier can only be accommodated in a higher energy excited level, which would produce emission at the energy above the biexciton line. Such a multicarrier state will also emit at the band-edge energy due to recombination involving the L1 electron and hole levels. Based on the above considerations, X*2 features can be assigned to emission due to radiative recombination of the L2 carrier, while the shoulder growing on the red side of the X*1 band can be attributed to recombination of the same multiexciton but via the L1 levels. The existence of the higher-energy optical transition at the position of the X*2 band is also evident from the ensemble PL excitation (PLE) spectra that show a distinct absorption feature at ~80 meV above the center of the emission band (Fig. 2; black circles). The latter value is in good agreement with the average shift of 75 ± 15 meV of the X*2 peak with respect to the band-edge X*1 feature (Fig. 2; histogram shown in blue).

To clarify the nature of the multiexciton responsible for the higher-energy X*2 band, we analyze the pump intensity dependence of the PL signal (Fig. 3d). We observe that the amplitude of the X*1 band grows linearly with P, while the X*2 band grows quadratically. These scalings are typical for the single exciton and the biexciton, respectively. The fact, that the biexciton produces emission involving not only the lowest-energy but also the excited levels indicates that it has been excited in the nanocrystal with a pre-existing long-lived charge, as was previously observed for CdSe NQDs.24 Thus, the B-type PL spectra most likely arise from charged g-NQDs, and consequently, X*1 and X*2 bands correspond to emission from charged single excitons (trions) and charged biexcitons, respectively. In the schematics in the lower panel of Fig. 4, we consider an example of a positively charged nanocrystal, which has an excess hole. We would like to point out, however, that based on the data available we cannot make a conclusive assignment of the type of charge residing in the type-B g-NQDs.

The assignment of the X*1 feature to the trion is consistent with the fact that even at very low pump intensities we do not observe any transformations from one band-edge line to the other that would be reminiscent of the interplay between the X1 to X2 features seen in the case of the 532 excitation (Figs. 1a and c). Instead, a single X*1 peak is observed for all pump intensities spanning the four-orders-of-magnitude range. Furthermore, the intensity of this peak shows almost perfect linear scaling over the entire range of pump powers (Fig. 3d). This is in contrast to switching between the linear and quadratic scalings, which accompanies the transition from the X1 to the X2 band in the case of the 532 nm excitation.

Interestingly, the spectrally integrated PL intensity measured with the 405 nm pump scales linearly with P without any signatures of saturation for both A and B type g-NQDs (Figs. 3b and d; black squares), indicating that both trions and charged biexcitons recombine primarily radiatively as the neutral biexcitons. This conclusion is at odds with one from ref. 21, where trions in g-NQDs were identified as “gray” (relatively weakly emitting) states with emission quantum yields of only 19%. We would like to point out, however, that the measurements of ref. 21 were conducted at room temperature while our studies have been done at T = 4 K. The effect of temperature on radiative and nonradiative decay channels in g-NQDs still remains unexplored. Therefore, it is not clear whether the emission efficiency of the trions (as well as other multicarrier states) is sensitive to changes in sample temperature.

The above results imply that the probability of nanocrystal photocharging for 405 nm excitation is higher than that for the 532 nm pump. The suppression of photocharging in the case of 532 nm excitation is likely due to the fact that the electrons and holes are created directly in the CdSe core, which is separated from the environment by the thick CdS shell. On the other hand, the 405 nm photons create carriers within the CdS shell. These “hot” carriers can either relax to the lowest-energy emitting core levels or get trapped at CdS shell surface states. Even if the second pathway is not very efficient, over time it can still lead to accumulation of a significant number of charged g-NQDs, especially under conditions of cw pumping when the nanocrystals are continuously recycled between the ground and the excited state. Furthermore, since the thick shell prevents the escape of charges from the core as well as the reentry of the opposite charge from the interface, one might expect that the g-NQDs can remain in the charged state for much longer than standard nanocrystals.

Based on our measurements, we attempted to quantify the likelihood of finding a charged nanocrystal in the case of the cw 405 nm pumping. Overall, we have studied ~30 g-NQDs. The ratio between the numbers of dots that exhibit B versus A behavior varied between 50/50 to 80/20 depending on pump intensity. These results indicate that under cw 405 excitation, the g-NQDs in our samples are on average more likely to be charged than neutral.

Pulsed excitation

Observation of high-order multiexcitons

We have also investigated spectral and dynamical properties of multiexcitons using pulsed 405 nm excitation. The maximum fluence in these measurements was 0.29 mJ cm−2 per pulse (j = 1 in normalized units). Interestingly, for pulsed excitation all of the studied dots have shown the A-type spectra typical of neutral nanocrystals, indicating a reduced probability of photocharging compared to cw 405 excitation. This suppression of photocharging likely results from the reduced excitation rate, which is at least a factor of 20 lower for pulsed excitation compared to the case of cw pumping. In our earlier ensemble studies of g-NQD solutions conducted under pulsed 405 nm excitation,20 we did not detect any signatures of significant photocharging either. Specifically, the measurements of multiexciton decay done on “static” and “stirred” solutions produced nearly identical dynamics. If photocharging were the issue, accumulation of charged dots within the excited volume of the “static” sample would have affected the measured dynamics.

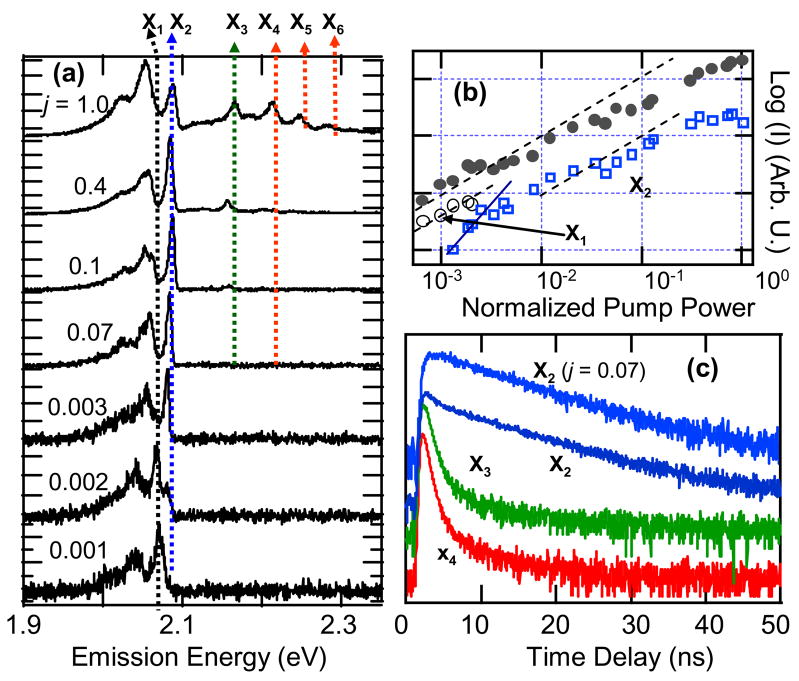

Using pulsed excitation, we are able to detect multiexcitons of higher order in addition to biexcitons. In the example in Fig. 5a, the single-exciton X1 band, which grows linearly with j, along with its phonon replica dominate the PL spectra at low pump fluences (see two bottom spectra in Fig. 5a and the pump-intensity dependence shown by open black circles in Fig. 5b). At j ~ 0.002, we observe the emergence of the X2 feature located ~13 meV above the X1 line. As expected for biexcitons, the amplitude of the X2 band grows quadratically with pump power (blue open squares in Fig 5b). At j of ca. 0.1, we observe a new higher energy band (X3) separated from X1 by ~85 meV (second spectrum from the top in Fig. 5a). The development of this higher-energy feature is likely due to the onset for the filling of the first excited L2 state, which allows us to attribute the X3 band to a triexciton (not a charged biexciton, as the clear X1–to-X2 transition allows us to conclude that this NQD is neutral). A further increase in the pump level leads to the development of three new higher-energy features (X4–X6) that appear at energies 140 to 210 meV above the X1 band. For these features, we do not have enough data points to clearly infer their scaling with j. However, given the fact that they emerge following the development of the X3 band, they likely correspond to multiexcitons of the fourth order and higher.

Figure 5.

(a) Time integrated PL spectra of the individual g-NQD measured using pulsed excited 405 nm excitation for different per pulse fluences (indicated in normalized units in the figure). In addition to the X1 and X2 bands, the spectra reveal four more higher-energy peaks (labeled X3 –X6) that are due to emission of triexcitons and other multiexcitons of higher order. (b) Pump-intensity dependence of the X1 (black open circles) and the X2 (blue open squares) features along with the spectrally integrated PL intensity (gray solid circles); dashed and solid lines correspond to linear and quadratic dependences, respectively. At low intensities, the measured dependence for the spectrally integrated PL signal is nearly linear but becomes sub-linear at j > 0.1. A progressive deviation of the measured data from the linear dependence with increasing j indicates that the decay of higher-order multiexcitons is contributed by Auger recombination, which leads to decreasing multiexciton emission yields with increasing exciton multiplicity. (c) PL dynamics measured at the positions of the X2, X3, and X4 features for j = 1. The X2 trace measured for j = 0.07 is also shown for comparison.

The observation of well-pronounced PL features due to high-order multiexcitons strongly supports the conclusion of a significant suppression of Auger recombination in g-NQDs. We would like to point out, however, that while the decay of biexcitons in g-NQDs is likely dominated by radiative processes, nonradiative Auger recombination still provides an appreciable contribution to decay of higher order multiexcions. We draw this conclusion based on the fact that the pump-power dependence of the spectrally integrated PL signal (solid black circles Fig. 5b) changes from linear to sublinear at j ~0.1, which corresponds to the onset for the development of the X3 band. A progressive deviation of the PL pump-intensity dependence from the linear growth with increasing j also indicates a decrease in the emission quantum yield with increasing multiexciton order. These observations can be explained by the fact that Auger decay times scale faster with exciton multiplicity (N) than the radiative lifetime. Specifically, previous studies of multiexcitons in nanocrystals indicate that the scaling of Auger lifetimes (τA) for larger nanocrystals is either cubic (τA∞N3) statistical [τA∞N2 (N − 1); ref. 2], while the “fastest” scaling observed for radiative lifetimes in nanocrystals is quadratic (τA∞N2).27

Finally, we conducted a time-resolved PL study of individual g-NQDs. Figure 5c displays the spectrally resolved PL dynamics measured at j = 1 at the spectral positions of the X2 to X4 peaks. The relaxation of the biexcitonic X2 feature shows a small initial fast component followed by the extended single exponential decay with the lifetime of ~11 ns. Since our previous analysis of pump-intensity dependent PL signals indicates that biexciton decay is primarily due to radiative processes, we attribute the 11 ns time constant to biexciton radiative recombination, and the initial fast component to decay of higher-order multiexcitons. This assignment is supported by the fact that the X2 dynamics measured at j = 0.07 [trace labeled as X2(j = 0.07) in Fig. 5c], when the PL spectra do not have any signatures of higher-order multiexcitons, show “clean” single-exponential decay with the 11 ns time constant.

At present, our measurements are not sensitive enough to monitor the dynamics of the X1 feature, which is seen only at very low excitation levels (j < 0.003). However, on the basis of ensemble measurements, we infer that the low-temperature single-exciton radiative lifetime in these g-NQDs is ~45 ns. If we further assume quadratic scaling of emission rates with exciton multiplicity,27 the corresponding biexciton radiative time constant should be ~11.25 ns. This value is in agreement with the measured lifetime of the X2 feature, providing further evidence that biexciton dynamics in g-NQDs is dominated by radiative recombination but not Auger decay.

The X3 and X4 peaks exhibit similar dynamics that are characterized by multiexponential decay with the initial “fast” time constant of ~1 ns. These dynamics are likely contributed not only by radiative processes but also by nonradiative Auger decay, as indicated by a sublinear pump-power dependence of the PL intensity at high excitation fluences (black solid circles of Fig. 5b). Because of close separation between X3–X6 features, the PL decay measured at high spectral energies is likely contributed by various high-order (3 and greater) multiexciton states. For quadratic scaling of radiative rates and a single-exciton radiative time of 45 ns, the radiative lifetime of states with multiplicity from 3 to 6 are in the 5-to-1.25 ns range. Even the shortest of these estimated times is still longer than the measured PL decay time constant, which points again to the fact that the dynamics measured for higher-order multiexcitons are not purely radiative but contributed by nonradaitive Auger recombination.

The mechanism underlying the suppression of Auger decay observed here for g-NQDs and in two recent reports for other types of nanostructures22,23 is still under investigation. In ref. 20, we discussed potential contributions to this suppression due to effects of the large g-NQD volume, reduced overlap between the electron and hole wave functions, exciton-exciton repulsion, and a smooth confinement potential at the CdSe/CdS interface. A preliminary conclusion of this analysis was that the most important factor was the smoothening of the interfacial potential, which reduces the uncertainty of the carrier momentum during the collision with the interface, and hence, the probability of Auger transitions. The impact of the shape of the interfacial potential on the rate of Auger recombination was recently discussed in great detail in ref. 28. At present, we are conducting direct experimental studies of the effect of controlled alloying, which smoothens the interfacial potential, on Auger decay rates in different types of core/shell nanocrystals.

Conclusions

In summary, we have performed detailed studies of low-temperature (T = 4 K) steady-state emission spectra and PL dynamics of CdSe/CdS g-NQDs using different pump-photon energies (532 vs. 405 nm) and excitation regimes (cw vs. pulsed). Using cw 532 nm excitation, we observe a well-resolved peak of biexciton emission (X2), which is blue-shifted from the single-exciton line on average by 25 ± 5 meV. This peak dominates the PL spectra at high pump intensities, which is in contrast to the situation in standard nanocrystals where biexcitons are essentially nonemitting as they decay primarily via fast nonradiative Auger recombination. The observation of a strong biexciton peak in g-NQD spectra points towards significant suppression of Auger decay in these nanostructures.

In the case of the cw 405 nm excitation, we observe two types of spectral behaviors depending on the particular g-NQD, which we attribute to co-existence of neutral and charged nanocrystals in the photoexcited ensemble. The PL spectra of neutral g-NQDs measured under 405 nm pumping are similar to those recorded for 532 nm excitation. On the other hand, charged g-NQDs instead of single-exciton and biexciton peaks show spectral features due to trions and charged biexcitons. The latter species are identified by a high-energy peak (X*2), blue shifted by 75 ± 10 meV from the band-edge feature, that develops as a result of the recombination of carriers occupying the first-excited electron or hole state. As is the case for neutral biexcitons, charged biexcitons, as well as trions, are highly emissive, which again indicates a significant reduction in the rate of Auger recombination.

Under pulsed 405 nm pumping, we do not observe any pronounced signature of photocharging, indicating that this process is much less efficient than under cw irradiation. At high intensities of pulsed excitation, in addition to the band-edge biexciton peak we observe a series of four high-energy peaks (X3–X6) located at 140 to 210 meV above the single-exciton line. We attribute these peaks to emission of multiexcitons of the order of 3 and higher. The single-nanocrystal PL dynamics measured for different emission peaks indicate the biexciton lifetime of 11 ns and ca. 1 ns average decay time for multiexcitons of higher order. We attribute the 11 ns time constant to almost purely radiative decay of biexcitons as indicated by a linear scaling of the corresponding emission line with pump level. On the other hand, the 1 ns decay of higher order multiexcitons in addition to radiative processes is also likely contributed by Auger recombination as suggested by a slight deviation from linearity in the measured PL pump intensity dependence observed at very high excitation levels.

The overall conclusion of this work is that Auger recombination is significantly suppressed in CdSe/CdS g-NQDs and that multiexcitonic emission is not simply observable, but efficient in this system. Specifically, our observations of nearly purely radiative trion and biexciton (charged and neutral) decay and strong emission from states of multiplicity 3 and higher clearly suggest that mutliexcitons in the CdSe/CdS g-NQDs are much more readily available for light-emitting applications than in standard nanocrystals. A significant potential of g-NQDs for lasing applications is indicated, for example, by our recent observations of an extraordinarily large spectral width (> 500 meV) of optical gain and multiband amplified spontaneous emission due to contributions of multiexcitons of order more than eight.20

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted in part in the Center for Integrated Nanotechnologies (CINT) jointly operated by Los Alamos and Sandia National Laboratories (LANL and SNL) for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). H.H. and J.A.H. acknowledge partial support by NIH-NIGMS Grant 1R01GM084702-01. A.V.’s work at LANL was conducted as part of the CINT user program. D.B. acknowledges support by the Chemical Sciences, Biosciences and Geosciences Division of the Office of Basic Energy Sciences (BES), Office of Science, U.S. DOE. V.I.K. is supported by the Center for Advanced Solar Photophysics, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the Office of BES, Office of Science, U.S. DOE. J.V.-B. and Y.C. acknowledge support by Los Alamos National Laboratory Directed Research and Development Funds.

References

- 1.Klimov VI. Ann Rev Phys Chem. 2007;58:635–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physchem.58.032806.104537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klimov VI, McGuire JA, Schaller RD, Rupasov VI. Phys Rev B. 2008;77(19) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Efros AL, Kharchenko VA, Rosen M. Solid State Commun. 1995;93(4):281–284. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klimov VI, Mikhailovsky AA, Xu S, Malko A, Hollingsworth JA, Leatherdale CA, Eisler HJ, Bawendi MG. Science. 2000;290(5490):314–317. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klimov VI, Ivanov SA, Nanda J, Achermann M, Bezel I, McGuire JA, Piryatinski A. Nature. 2007;447(7143):441–446. doi: 10.1038/nature05839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kazes M, Lewis DY, Ebenstein Y, Mokari T, Banin U. Adv Mater. 2002;14(4):317. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundar VC, Eisler HJ, Bawendi MG. Adv Mater. 2002;14(10):739. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anikeeva PO, Madigan CF, Halpert JE, Bawendi MG, Bulovic V. Phys Rev B. 2008;78(8) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colvin VL, Schlamp MC, Alivisatos AP. Nature. 1994;370(6488):354–357. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greenham NC, Peng XG, Alivisatos AP. Phys Rev B. 1996;54(24):17628–17637. doi: 10.1103/physrevb.54.17628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nozik AJ. Physica E. 2002;14(1–2):115–120. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y, Vela J, Htoon H, Casson JL, Werder DJ, Bussian DA, Klimov VI, Hollingsworth JA. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130(15):5026. doi: 10.1021/ja711379k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hollingsworth JA, Vela J, Yongfen C, Htoon H, Klimov VI, Casson AR. Proc SPIE Int Soc Opt Eng. 2009;718904:7. doi: 10.1117/12.809678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahler B, Spinicelli P, Buil S, Quelin X, Hermier JP, Dubertret B. Nat Mater. 2008;7(8):659–664. doi: 10.1038/nmat2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nirmal M, Dabbousi BO, Bawendi MG, Macklin JJ, Trautman JK, Harris TD, Brus LE. Nature. 1996;383:802. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuno M, Fromm DP, Hamann HF, Gallagher A, Nesbitt DJ. J Chem Phys. 2000;112:3117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stefani FD, Hoogenboom JP, Barkai E. Phys Today. 2009;62(2):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Efros AL, Rosen M. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;78(6):1110–1113. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peterson JJ, Nesbitt DJ. Nano Lett. 2009;9(1):338–345. doi: 10.1021/nl803108p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Santamaria F, Chen YF, Vela J, Schaller RD, Hollingsworth JA, Klimov VI. Nano Lett. 2009;9(10):3482–3488. doi: 10.1021/nl901681d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spinicelli P, Buil S, Quelin X, Mahler B, Dubertret B, Hermier JP. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102(13) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.136801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osovsky R, Cheskis D, Kloper V, Sashchiuk A, Kroner M, Lifshitz E. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102(19) doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.197401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang XY, Ren XF, Kahen K, Hahn MA, Rajeswaran M, Maccagnano-Zacher S, Silcox J, Cragg GE, Efros AL, Krauss TD. Nature. 2009;459(7247):686–689. doi: 10.1038/nature08072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Achermann M, Hollingsworth JA, Klimov VI. Phys Rev B. 2003;68(24) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Efros AlL, Rodian AV. Solid State Commun. 1989;72(645) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piryatinski A, Ivanov SA, Tretiak S, Klimov VI. Nano Lett. 2007;7(1):108–115. doi: 10.1021/nl0622404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGuire JA, Joo J, Pietryga JM, Schaller RD, Klimov VI. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41(12):1810–1819. doi: 10.1021/ar800112v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cragg GE, Efros AL. Nano Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1021/nl903592h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]