Abstract

The nuclear respiratory factor-1 (NRF1) gene is activated by lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which might reflect TLR4-mediated mitigation of cellular inflammatory damage via initiation of mitochondrial biogenesis. To test this hypothesis, we examined NRF1 promoter regulation by NFκB, and identified interspecies-conserved κB-responsive promoter and intronic elements in the NRF1 locus. In mice, activation of Nrf1 and its downstream target, Tfam, by Escherichia coli was contingent on NFκB, and in LPS-treated hepatocytes, NFκB served as an NRF1 enhancer element in conjunction with NFκB promoter binding. Unexpectedly, optimal NRF1 promoter activity after LPS also required binding by the energy-state-dependent transcription factor CREB. EMSA and ChIP assays confirmed p65 and CREB binding to the NRF1 promoter and p65 binding to intron 1. Functionality for both transcription factors was validated by gene-knockdown studies. LPS regulation of NRF1 led to mtDNA-encoded gene expression and expansion of mtDNA copy number. In cells expressing plasmid constructs containing the NRF-1 promoter and GFP, LPS-dependent reporter activity was abolished by cis-acting κB-element mutations, and nuclear accumulation of NFκB and CREB demonstrated dependence on mitochondrial H2O2. These findings indicate that TLR4-dependent NFκB and CREB activation co-regulate the NRF1 promoter with NFκB intronic enhancement and redox-regulated nuclear translocation, leading to downstream target-gene expression, and identify NRF-1 as an early-phase component of the host antibacterial defenses.

Keywords: Mitochondrial biogenesis, Nuclear respiratory factor-1, Reactive oxygen species, Toll-like receptor-4

Introduction

The impact of activation of innate immunity on the regulation of energy production, despite its importance in cell survival, is poorly understood, especially with respect to cis-acting elements that bind to gene promoters involved in the transcriptional program of mitochondrial biogenesis. An example is the full spectrum of processes involved in immunity, inflammation, proliferation and apoptosis that are activated by the pleiotropic transcription factor NFκB and lead to a broad array of effects (Ghosh and Karin, 2002). The five NFκB family members, p50, p52, p65 (RelA), cRel and RelB, share a Rel-homology domain that is responsible for dimerization and for the DNA binding that imparts transcriptional activity (Hayden and Ghosh, 2008). In classical NFκB activation, Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands, such as the TLR4 cognate lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and NFκB-dependent cytokine secretion, particularly TNFα, lead to IκK activation, resulting in phosphorylation of IκB, followed by ubiquitylation by the E3 ligase (Skaug et al., 2009). Ubiquitylated IκB is degraded, allowing NFκB to enter the nucleus to activate transcription.

Further processing is required for NFκB-activated gene expression; for instance, p65 phosphorylation enables transcription by allowing interactions with acetyltransferase co-activators such as CBP and p300 (Zhong et al., 1998). There is also crosstalk between NFκB and other transcription factors, including CREB, p53, IRF3 and IRF7, that use CBP/p300 (Martin et al., 2005; Yang et al., 2004). Some NFκB-regulated genes require chromatin modification; constitutive and immediately accessible (CIA) promoters require no modification, whereas regulated and late accessibility (RLA) promoters depend on stimulus-specific chromatin remodeling for differential control of inflammatory gene expression (Ramirez-Carrozzi et al., 2006). Known connections between NFκB and physiological processes are actively expanding; for instance, NFκB is associated with regulation of mammalian aging (Adler et al., 2007), and in myoblasts, the classical NFκB pathway inhibits differentiation, whereas in newly contractile myotubes, selective IκKα activity and the p52-RelB non-canonical pathway stimulate mitochondrial biogenesis by unknown mechanisms (Bakkar et al., 2008).

Another transcription factor, nuclear respiratory factor-1 (NRF-1), is essential for the integration of nuclear- and mitochondrial-encoded gene transcription (Evans and Scarpulla, 1989). NRF-1 dimerizes and binds to palindromic promoter sites of mitochondrial genes (Virbasius et al., 1993), interacting with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ co-activator-1α (PGC-1α) and PGC-1-related co-activator (PRC), which can operate in concert with CREB to activate target genes involved in mitochondrial function (Vercauteren et al., 2006; Wu et al., 1999). Among the several hundred NRF-1 target genes are subunits of all five mitochondrial respiratory complexes (MRCs), assembly factors, parts of the mtDNA transcription and replication machinery, components of heme biosynthesis and mitochondrial protein import, and mtDNA transcription factors A (Tfam) and B (TFB1M and TFB2M, mtTFB1 and mtTFB2) (Kelly and Scarpulla, 2004). Tfam and the mtTFBs transcribe the mitochondrial genome, leading to an increase in mitochondrial-encoded subunits of the MRC (Scarpulla, 2008). The Nrf1−/− mouse shows mtDNA depletion and embryonic lethality, confirming an integral role of NRF-1 in cell viability (Huo and Scarpulla, 2001).

NRF1 expression, similarly to that of NFκB, is stimulated by exogenous factors and by endogenous physiological events (Bergeron et al., 2001; Piantadosi and Suliman, 2006; Scarpulla, 2008; Xia et al., 1997). NRF-1 is coordinately involved in the regulation of mitochondrial mass (Chen and Yager, 2004), and is strongly upregulated by LPS in wild-type but not in Tlr4−/− mice. In the latter case, the limited response delays the restoration of mtDNA copy number (Suliman et al., 2004; Suliman et al., 2005). Despite the hundreds of genes, including dozens of transcription factors potentially activated by NFκB (Tian and Brasier, 2003), no direct interactions between classical NFκB signaling and the transcriptional activation of mitochondrial biogenesis have been defined. Hence, we tested the hypothesis that NFκB, acting through the LPS-receptor pathway, regulates NRF1 directly, leading to amplification of mitochondrial mRNA transcription and enrichment of mtDNA copy number. Our initial findings substantiated such a role for NFκB; however, the full protection of mtDNA copy number after activation of the LPS receptor complex also required cooperative CREB-dependent regulation of NRF1.

Results

NRF-1 and mtDNA transcription and replication via NFκB activation in vivo

The effect of NFκB activation on Nrf1 expression was characterized in the livers of mice injected with a single i.p. dose of heat-inactivated E. coli (5×106 c.f.u.) by measuring sequential Nrf1 mRNA levels. In wild-type mice, Nrf1 mRNA analysis by real time RT-PCR showed that hepatic mRNA levels increase significantly 6-24 hours after E. coli administration (Fig. 1A). To test whether NFκB activation regulates NRF-1 production, mice were pre-treated with the irreversible IκB kinase inhibitor, BAY11-7085, followed by E. coli. BAY11 significantly delayed and attenuated the increase in Nrf1 mRNA (Fig. 1A). The inhibitory effect of BAY11 on NFκB was confirmed by suppression of E. coli-induced NOS2 expression (data not shown). To confirm that NFκB participates in Nrf1 gene expression, we challenged p50−/− mice with heat-inactivated E. coli. The absence of p50 inhibited only the 6 hour Nrf1 gene expression (Fig. 1A), implicating p50 in initial Nrf1 induction and one or more other subunits in the complete early-phase response.

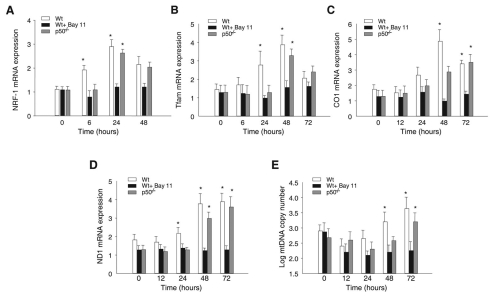

Fig. 1.

NFκB-dependent activation of Nrf1 and downstream NRF1 target-gene expression in mice. Timed experiments for the effects of administration of heat-inactivated E. coli in wild-type BAY11-treated mice and p50−/− mice. (A) Hepatic Nrf1 mRNA expression determined by real time RT-PCR. (B) Hepatic Tfam mRNA expression by real time RT-PCR. (C) Hepatic mitochondrial CO1 (Mtco1) mRNA expression by real time RT-PCR. (D) Hepatic mitochondrial ND1 (Mtnd1) mRNA expression by real time RT-PCR. (E) Hepatic mitochondrial DNA copy number determined by real time PCR. Values are means ± s.e. of 4-6 mouse livers (*P<0.05).

NRF-1 stimulates nuclear-encoded Tfam expression by binding to NRF-1-response elements in the promoter region (Virbasius and Scarpulla, 1994). Tfam is then imported into mitochondria and increases mtDNA transcription and replication (Scarpulla, 2002). The mRNA levels for Tfam and two mitochondrial-encoded proteins, COI and NDI, were analyzed by real time RT-PCR to determine whether Nrf1 induction by NFκB activation causes Tfam transcription and mitochondrial-encoded target gene expression. In wild-type mouse liver, Tfam mRNA levels increased at 24 and 48 hours after E. coli administration, and the response was blocked by addition of BAY11 (Fig. 1B). Tfam expression was also delayed in p50−/− mice until 48 hours (Fig. 1B). mRNA levels of mtDNA-encoded COI (Mtco1) and NDI (Mtnd1) increased 24-48 hours after E. coli administration; this was inhibited in BAY11-treated mice and delayed in p50−/− mice (Fig. 1C-D). We also examined downstream NFκB-mediated effects of NRF-1 induction by checking hepatic mtDNA copy number, and found an increased copy number at 48 and 72 hours after E. coli administration that was inhibited in wild-type mice by BAY11 and delayed in p50−/− mice (Fig. 1E).

Identification of κB sites in the NRF-1 locus

Since NRF-1 expression was induced in an NFκB-dependent manner, we explored how LPS and E. coli stimulate NRF1 gene expression. Despite mounting evidence that the immune system activates NRF1 (Piantadosi and Suliman, 2006; Suliman et al., 2003; Suliman et al., 2005), there are no reports of the gene having functional κB-binding sites. We searched for NFκB and CREB consensus binding sequences using web-based rVISTA to identify conserved sequences for specific transcription factors by linking them to the TRANSFAC database (Loots and Ovcharenko, 2004). Analysis of the mouse and human proximal 1.5kb of the NRF1 5′UTR (DNAsis and Genomatix) identified potential NFκB-response elements (κBREs) within the conserved NRF1 5′-promoter sequence. A schematic of the NRF1 locus with expanded sequences is shown in Fig. 2A where the regions at −500 to −120 of the mouse and −920 to −150 of the human upstream of the NRF-1 transcription start site (TSS) bear sequences identified with a high likelihood for NFκB binding by exhibiting 90-100% identity with the canonical NFκB enhancer sequence, 5′-GGRRNNYYCC-3′ (where R is a purine, Y is a pyrimidine and N is any nucleic acid). Comparative sequence analysis, effective for finding functional coding and non-coding elements in vertebrates (Loots et al., 2002), identified 11 NFκB sites in the non-coding region; one in the promoter region is interspecies-conserved whereas three conserved sites are located in intron 1 at positions +902 and +972 relative to the human or mouse TSS. As the other NFκB sites are not conserved between human and mouse, intron 1 might be particularly important for NFκB regulation of NRF1 gene expression.

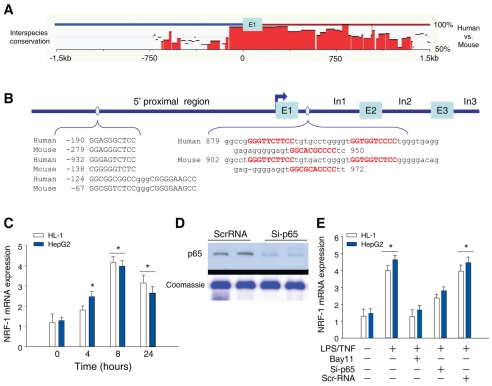

Fig. 2.

Bioinformatics analysis of the 5′-proximal region of the NRF1 gene promoter and conserved region of intron 1 in the mouse and human. (A) Sequences were aligned between human and mouse using rVISTA 2.0. The middle histogram represents the interspecies DNA conservation within the 5′-UTR segment. CNS (interspecies conservation more than 75%) is emphasized in red. (B) The first three exons (E) and the first three introns (In) for the NRF1 gene are shown. NFκB consensus sequences for human and mouse NRF1 genes identified by Genomatix and DNAsis are displayed on the blue line under the histograms. Detailed sequences spanning promoter and intron NFκB motifs are depicted at the bottom. Red letters indicate the NFκB consensus sequences. (C) Timed NRF-1 induction in human HepG2 and mouse HL-1 cells after LPS +TNFα exposure (10 ng/ml each). (D) Western blot for p65 in HepG2 cells transfected with control siRNA or p65 siRNA. (E) NRF-1 expression in HepG2 and HL-1 cells before and 8 hours after incubation with LPS+TNFα. Cells with BAY11 (50 μM) were pretreated for 1 hour before addition of LPS+TNF. Cells with control siRNA or siRNA targeting p65 (si-p65) were transfected 48 hours before LPS+TNF treatment for 8 hours. NRF1 mRNA expression was determined by q-RT-PCR. Values with error bars are means ± s.e. of four replicates (*P<0.05).

To establish NRF1 as an NFκB target gene, we treated TLR4-activatable human HepG2 and mouse HL-1 cardiac cells with LPS and TNFα and measured NRF-1 expression by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Cell dose-time experiments with LPS and TNFα, singly and in combination, revealed maximal NRF1 mRNA induction by 10 ng/ml of each after 4-8 hours (data not shown). LPS upregulated NRF1 mRNA expression in both cell lines, with earlier induction in HepG2 than in HL-1 cells (Fig. 2C) and LPS+TNFα gave the most rapid response. To examine the contribution of NFκB to NRF1 gene activation by LPS and/or TNFα, cells were transfected with control non-specific siRNA or siRNA targeting RelA/p65, and silencing efficacy was determined at 48 hours (Fig. 2D). After establishing an optimal protocol for each line, the cells were treated with LPS and/or TNFα for 8 hours. Control siRNA did not affect basal or LPS- and TNF-induced NRF1 transcription, whereas knockdown of RelA/p65 reduced basal and LPS-stimulated NRF1 mRNA levels by about half (Fig. 2E). To confirm that NFκB directly mediates LPS- and TNF-induced NRF1 expression, cells were treated for 6 hours with BAY11 before LPS or TNF, which blocked the increase in NRF1 mRNA and provided evidence that NFκB mediates the response (Fig. 2E). Figs 1 and 2 thus indicate that NFκB activation contributes to LPS- and LPS+TNF-induced NRF1 transcription in vivo and in HepG2 and HL-1 cells.

Given the potential NFκB-binding sites identified in the NRF1 promoter and intron 1 regions, we used electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (EMSA) to investigate NFκB binding specificity at these sites. Liver nuclear extracts from mice treated with E. coli were used in binding reactions with probes containing either NFκB promoter (P) sequences (Fig. 3A) or intron (I) sequences (Fig. 3B). In Fig. 3C, when promoter region probes P1-P4 were used in the analysis, the signal for the DNA-protein complex was shifted in liver extract from E. coli-treated mice. Signal intensity was highest with P2, and this labeling was essentially absent in liver nuclear extracts from untreated mice (lane C). Furthermore, when a mutant probe (Mu) for the NFκB consensus sequence was used with liver extract from E. coli-treated mice, no DNA-protein complex was observed (Fig. 3C).

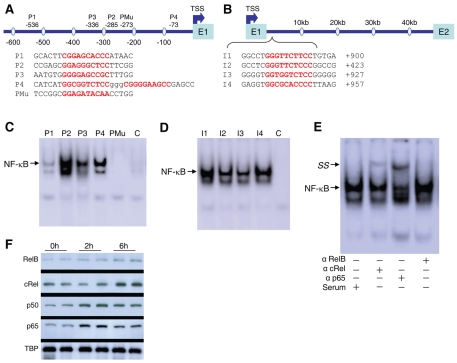

Fig. 3.

Gel-shift analyses using oligonucleotide probes for NFκB in the Nrf1 locus. The probes are listed below the maps of the (A) 5′-proximal region and (B) intron 1 region. A mutant (Mu) probe was also used. Nuclear extracts from wild-type mice with or without E. coli administration were prepared from fresh liver and used for gel-shift analysis with different NFκB consensus probes from Nrf1. Arrows indicate NFκB complexes. (C) Gel-shift experiments using NFκB-motif containing probes; lanes 1-4 are nuclear extract from livers of wild-type mice 2 hours after addition of E. coli using 32P-labeled oligonucleotides derived from the Nrf1 promoter (labeled P1-P4, respectively). A mutant oligonucleotide was used in lane 5, and lane 6 is nuclear extract from control mouse liver using oligonucleotide P2. (D) Gel-shift on mouse liver nuclear extracts at 2 hours after E. coli exposure using the intronic region oligonucleotides I1-I4. (E) EMSA of wild-type mouse liver nuclear protein 2 hours after E. coli exposure. Nuclear protein was incubated with 32P-labeled NFκB recognition site (P2) and with serum or polyclonal anti-RelB, anti-cRel or anti-p65. The supershift complex is indicated by SS. The cRel and p65 supershifts are typical of three experiments. (F) Representative nuclear western blots of NFκB subunits in wild-type mouse liver after E. coli treatment. TBP was detected as a loading control.

When nuclear probes for the intronic region (I1-I4) were used, a shift in the DNA-protein signal from E. coli-treated mice was observed (Fig. 3D). The signal intensity was highest with I1, and was greatly attenuated in nuclear extracts from untreated mice (Fig. 3D, lane C). Supershift experiments with anti-RelA or anti-cRel antibody showed that the P2-binding factor was primarily p65, and to a lesser extent, cRel, but no RelB supershift was detected (Fig. 3E). This indicated a specific NFκB interaction with the predicted binding site in the Nrf1 promoter.

NFκB subunit nuclear translocation was also checked at different times. Liver nuclei of E. coli-treated mice showed p65 translocation by 2 hours and cRel translocation by 6 hours (Fig. 3F). E. coli induced a minor p50 translocation at 2 hours and almost no RelB translocation.

NFκB binding to Nrf1 promoter in vivo

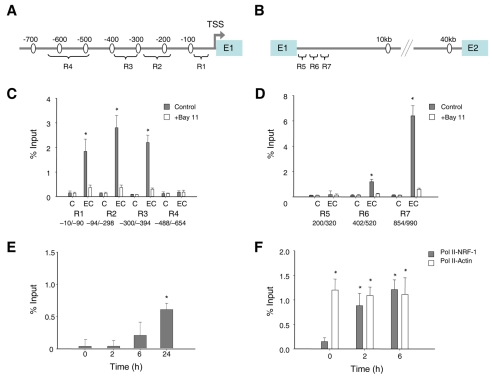

ChIP assays were used to examine whether NFκB bound directly to putative κB sites identified in the Nrf1 promoter and intronic regions in mouse liver after E. coli challenge. ChIP was used with anti-NFκB p65 and primer sets designed to detect the promoter and intron 1 of Nrf1 (Fig. 4A,B). Since recruitment of transcription factors precedes the maximal transcription rate (Ryser et al., 2007; Ryser et al., 2004), we monitored p65 occupancy of these Nrf1 regions at 2 hours and 6 hours after E. coli and found that p65/RelA bound most strongly at 6 hours to promoter regions R1 to R3 (Fig. 4C) and to intron 1 at R7, just downstream of exon 1 (Fig. 4D). The ChIP indicated moderate p65 promoter occupancy after E. coli treatment, but more active binding at intron 1 (Fig. 4D). Since anti-cRel antibody had shown binding to P2, we assessed the occupancy of cRel at the Nrf1 promoter, and cRel binding at position −94 to −298 was found at 6 and 24 hours (Fig. 4E). Occupancy of the Nrf1 promoter by p65 was also accompanied by DNA PolII recruitment, which is indicative of initiation of transcription (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

ChIP analysis for NFκB occupancy at the Nrf1 promoter and intronic sites. (A) Primer locations for ChIP and quantitative real-time PCR at the 5′-proximal regions of Nrf1 (R1, R2, R3, R4). (B) Locations of primers for ChIP and quantitative real-time PCR at intron 1 of Nrf1 (regions R5, R6, and R7). (C) Hepatic ChIP analysis for promoter regions R1-4 in control (C) and E. coli-treated (EC) mice with or without the NFκB inhibitor BAY11. (D) Hepatic ChIP analysis for intron regions R5-7 of control (C) and E. coli-treated (EC) mice with or without BAY11. Rabbit anti-p65 antibody (Cell Signaling) was used for the ChIP assay and quantification of immunoprecipitated DNA fragments was performed by real-time PCR. Values in C and D were normalized to corresponding input control (*P<0.01 compared with BAY11. Data are means ± s.e. for 4-6 experiments). (E) ChIP analysis of liver nuclei pre- and at 2, 6 and 24 hours after E. coli (anti-cRel antibody; Santa Cruz). (F) ChIP confirmation of occupancy of the RNA PolII transcription complex in the NRF-1 and β-actin gene promoters using antibody against RNA PolII at 0, 2 and 6 hours after the mice received HKEC. Values for E and F were normalized to corresponding input control (*P<0.05 compared with time 0. Data in E and F are means ± s.e. of four experiments).

CREB binding to Nrf1 promoter and enhanced transcription

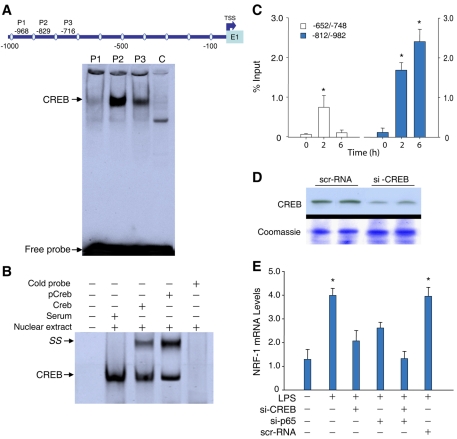

The Nrf1 promoter region revealed CRE-binding sites at three locations: −714, −829 and −968, respectively. CREB binding was evaluated in nuclear protein extracts from control and E. coli-stimulated livers with unique oligonucleotides for the three promoter CRE motifs (Fig. 5). The EMSA indicated the formation of a single DNA-protein complex (Fig. 5A, arrow) with changes in the intensity of the complex in response to E. coli, with the highest intensity for the −829 tcTGACACCAtg sequence (Fig. 5A). Since transcriptional activation by CREB occurs when Ser133 is phosphorylated, EMSA was used with supershift assays for CREB and phosphorylated CREB to test binding at the Nrf1 promoter CRE sites. We found an oligonucleotide-protein complex supershift in liver nuclear extracts from mice treated with E. coli (Fig. 5B). Unlabeled CRE oligonucleotide in molar excess outcompeted labeled oligonucleotide for binding, indicating specificity of the CRE complex.

Fig. 5.

CREB activation by EMSA and ChIP assay. (A) Liver nuclear extracts from mice treated with E. coli were incubated with 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes containing CREB consensus sites from the Nrf1 promoter (see map). Lane 1, probe P1 at −968 ttGGAGGTCAgc; lane 2, probe P2 at −829 tcTGACACCAtg; lane 3, probe P3 at −716 ctGATGACAtaa; lane 4, control (C) nuclear extract. (B) CREB activation measured by EMSA. Incubation of 32P-labeled −829-tcTGACACCAtg with nuclear extract and total or phosphorylated CREB antibody, but not serum, supershifted the complex (SS). Cold probe (100-fold excess) eliminated the CREB-specific complex (arrow). (C) ChIP analysis of liver nuclei of control and E. coli-treated mice using anti-CREB antibody (Santa Cruz) at 0, 2 and 6 hour time points. (D) Western blot for HepG2 cells transfected with scrambled siRNA or CREB siRNA showing CREB silencing. (E) NRF-1 expression in control cells or cells treated with LPS and transfected with p65 siRNA, CREB siRNA, or both. Histograms show mean ± s.e. of 4-6 experiments at 8 hours after LPS (*P<0.05 vs control).

A further ChIP assay in liver revealed significant CREB binding to the Nrf1 promoter at two different positions (−652 to −748, −812 to −982) (Fig. 5C). Interestingly, the two sites were activated at different times in E. coli-treated mice and the −829 CREB site showed more binding activity at 6 hours.

To confirm NRF1 as a transcriptional target of NFκB p65 and CREB, one or both were silenced in HepG2 cells. We have reported NRF-1 silencing in these cells at 24-48 hours, and effective CREB silencing is demonstrated in Fig. 5D. The transfected cells were treated with LPS and TNF for 8 hours and NRF1 expression was measured by real-time RT-PCR. These data showed that NRF1 induction was suppressed by silencing CREB and p65 (Fig. 5E).

LPS induces a functional Nrf1 promoter

We mapped the upstream Nrf1 promoter region to expand our knowledge of potential interactions between basal transcriptional core promoter elements and specific DNA-binding and accessory transcription factors. For instance, Nrf1 ARE consensus sequences bind NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nfe2l2) to enhance its expression in the heart (Piantadosi et al., 2008), but in inflammation, the presence of complex cognate TLR signaling would imply the involvement of several transcription factors in transcriptional regulation of Nrf1.

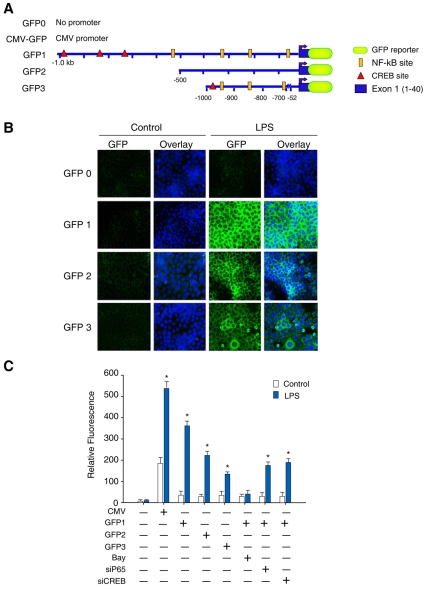

Regulatory sequences upstream of the core region that might have a role in Nrf1 transcription were delineated by cloning three DNA fragments spanning −1000 to +40 bp, −500 to +40 bp and a chimera −1000 to −700 plus −52 to +40 bp region of the mouse Nrf1 promoter upstream of the TSS into plasmid pGlow-TOPO (Fig. 6A). The constructs were designated GFP1 (p1040-Nrf1glow), GFP2 (p540-Nrf1glow) and GFP3 (p392-Nrf1glow).

Fig. 6.

Functional cis-acting elements in the NRF1 promoter. NFκB and CREB function at the NRF1 promoter was established in HepG2 cells transfected with plasmid pGlow (GFP0) containing no promoter region (negative control) or plasmids harboring regions −500 to +40 (GFP2) or a chimeric promoter for −1000 to −700 plus −52 to +40 bp (GFP3) of the NFR1 gene. To assess additive effects of the two elements spanning −1000 to +40 of NRF-1, transfection was also carried out using promoter −1000 to +40 (GFP1). (A) Schematic representations of various plasmids used in the transfection assays are labeled on the left (drawings are not to scale). Plasmids pCMV-GFP and GFP0 plasmid were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. (B) HepG2 cells transfected with the GFP plasmids. The activity of each construct was measured before and 24 hours after LPS. Green indicates GFP expression driven by the NRF1 promoter construct by fluorescence microscopy. The blue fluorescence is nuclear staining with DAPI. (C) Relative activity of each construct measured before and after 24 hours of LPS treatment. The activity of construct GFP1 was measured as fluorescence intensity after treatment of cells with the NFκB inhibitor BAY11 or after co-transfection with p65 or CREB siRNA. Comparative fluorescence intensity represents means ± s.e. of three independent studies performed with plasmids in triplicate (*P<0.05).

We expected that GFP expression from the basal promoter would be altered depending on the presence of regulatory sequence(s) in this region. For these assays, HepG2 cells were used for ease of transfection and high LPS responsiveness. After transfection with the vectors, HepG2 cells were treated for 8 hours with LPS, and GFP activity was measured 24 hours later by fluorescence microscopy or by microplate fluorometer. Our results with these constructs are shown in Fig. 6B (cell images) and Fig. 6C (histograms). In preliminary studies, the basal NRF1 promoter transcription efficiency was ~1.06-fold that of control promoter-free vector (GFP0; not shown). After LPS exposure in cells transfected with GFP1, green fluorescence intensity increased 11-fold compared with untreated cells (Fig. 6B,C), whereas fluorescence increased ~7-fold in cells transfected with GFP2 vector compared with untreated cells (Fig. 6B,C), suggesting that the −500 to +40 region of NRF1 augments transcription by the basal promoter. GFP1 transfection revealed an enhanced NRF1 promoter transcription efficiency compared with cells transfected with plasmid GFP2, thus implicating additional regulatory motifs between −1000 and −500 in the sequence. The −1000 to −500 region also had CREB consensus sequences at −968, −829, −716 and −714; however, deletion of −700 to −52 as in GFP3 caused a 63.5% decrease in GFP fluorescence intensity compared with GFP1, indicating that CREB cooperates with NFκB in the 1040 bp fragment to drive optimal NRF1 promoter activity.

To assess the effect of NFκB binding on NRF1 promoter activity, transient transfection analysis with the GFP1 construct was carried out in HepG2 cells with and without BAY11 treatment. GFP1-transfected cells treated with BAY11 followed by exposure to LPS showed a ~90% lower promoter transcription efficiency compared with control LPS-treated cells (Fig. 6C). Cooperation between NFκB and CREB was seen in HepG2 cells co-transfected with GFP1 and p65 siRNA or CREB siRNA. Co-transfection before LPS treatment with p65 or CREB siRNA decreased transcriptional efficiency at the NRF1 promoter by 52% and 48%, respectively. Thus, NFκB p65 and CREB are both required for optimal NRF1 expression after LPS treatment. BAY11 also blocked the effects of CREB, and conversely, CREB siRNA reduced the effect of CREB and decreased the stimulatory effects of NFκB. This crosstalk indicates that NFκB and CREB cooperate for maximal LPS-induced NRF1 promoter activation.

Intronic NFkB enhancement of NRF1 gene expression

To determine the role of the intronic κB binding sites in NRF1, we constructed a GFP vector consisting of a promoter sequence derived from the 5′-proximal NRF1 region (from −1000 to +40 bp or −500 to +40 bp relative to the TSS) and an enhancer sequence derived from the first intron (+902 to +980 bp of intron 1 relative to the TSS). This 78 bp fragment with the enhancer sequence, apart from the NFκB site, includes no other known transcription factor elements. A mutation of the NFκB site was introduced into construct GFP7. As shown in Fig. 7A-C, the GFP reporter vector with 5′-proximal region (GFP 4) and the 78 bp NFκB-binding region had 58-fold higher fluorescence intensity after LPS treatment compared with control vector without the promoter or enhancer (GFP0) and ~14-fold compared with untreated controls. Transfection of GFP5 vector (−500 to +40) with the intronic enhancer site resulted in a ~7.7-fold induction in GFP fluorescence intensity after LPS treatment. However, deletion of the 648 bp between −700 and −52 to form GFP6, containing only the CREB site, caused the GFP fluorescence intensity to drop by 50% after LPS (Fig. 7C). We further examined the effects of BAY11 on the enhancer activity of NFκB using a vector with both the 5′-proximal NFκB region and enhancer (GFP5). Here BAY11 alone did decrease GFP activity compared with the control (Fig. 7C). Experiments using a vector containing mutant intronic κB sites (GFP7) decreased the LPS effect on GFP activity by 50% compared with results with GFP5 (Fig. 7C), confirming the involvement of the intronic kB site in NRF1 gene expression. These results indicate that intronic NFκB functions as a cis-acting enhancer element on the NRF1 locus.

Fig. 7.

NFκB binding in intron 1 enhances NRF1 promoter activity. (A) Schematic representations of various plasmids used in the transfection assay are given on the left. The plasmid drawings are not to the scale. Plasmids pCMV-GFP and GFP0 plasmid were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. The reporter constructs are GFP0 (negative control), pCMV-GFP (positive control); GFP4, containing the 1040 bp region at the 5′ site (−1000 to +40 bp of exon 1) plus the 78 bp region of intron 1; GFP5, containing the 540 bp region at the 5′ site (−500 to +40) plus the 78 bp region of intron 1; GFP6, containing the 78 bp of intron 1 region of the NFκB sites plus the chimeric promoter region (−352 to +40 bp of exon 1), and GFP7, containing the mutation at intronic NFκB sites within 78 bp plus the region from plasmid GFP5. (B) HepG2 cells transfected with the respective plasmids. The activity of each construct was measured before and after 24 hours of LPS treatment. Green fluorescence represents GFP expression driven by NRF1 promoter and intronic constructs detected by fluorescence microscopy. The blue fluorescence is nuclear staining with DAPI. (C) Ratio of observed fluorescence intensity to the basal level for GFP0 or to untreated controls. The relative activity of each construct was measured before and 24 hours after LPS treatment. GFP4 activity was measured after treatment of cells with BAY11. Relative fluorescence intensity represents mean ± s.e. of three studies performed with plasmids in triplicate (*P<0.01 vs GFP1 and P<0.05 vs BAY11).

Mitochondrial H2O2 signaling of NFκB- or CREB-mediated NRF1 gene expression

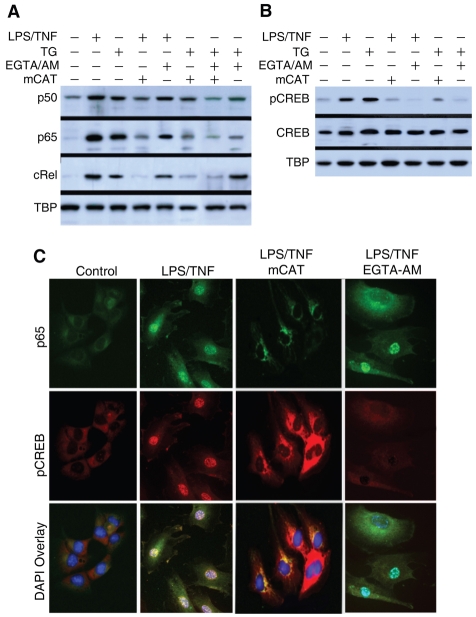

NFκB and CREB are among the redox-regulated transcription factors that can be activated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Frey et al., 2008). Because innate immune effector molecules, such as TNFα, stimulate mitochondrial ROS production, we asked whether mitochondrial ROS influence NFκB- or CREB-mediated NRF1 gene expression directly or alternatively via cytoplasmic Ca2+ signaling. Superoxide and H2O2 egress via Complex III, for instance, might serve as a messenger for NFκB activation directly, or perhaps in conjunction with Ca2+ (Sen et al., 1996). Therefore we used a mitochondrial-targeted catalase vector to investigate the role of mitochondrial H2O2 production in activation of NFκB and CREB. Normal mouse HL-1 atrial cardiomyocytes were transfected with mtCAT or empty vector for 48 hours, exposed to LPS+TNF for 4 hours, and nuclear extracts were analyzed for NFκB and CREB. The presence of mCAT inhibited the LPS+TNF-dependent accumulation of nuclear NFκB subunits by ~50-80% and phosphorylated CREB by approximately two thirds (Fig. 8A,B), implicating mitochondrial H2O2 release as a control point.

Fig. 8.

Role of reactive oxygen species and calcium on LPS-induced activation of NFκB and CREB. (A) Nuclear western blots of p65, p50 and cRel protein in cells transfected with mCAT or empty vector for 48 hours before administration of LPS and TNF. In some experiments, cells were treated with Ca2+ chelator (20 μM EGTA-AM) or with 30 nM thapsigargin (TG), or both for 30 minutes followed by LPS and TNF for 2 hours. Nuclear extracts were immunoblotted with anti-p65, anti-p50, anti-cRel or anti-TBP. (B) Nuclear western blots of pCREB and total CREB protein in cells with or without mCAT transfection 48 hours before LPS and TNF treatment. In some experiments, cells were treated with 20 μM EGTA-AM or with 30 nM TG or both for 30 minutes followed by LPS and TNF for 2 hours. Nuclear extracts were immunoblotted with antibodies against phosphorylated CREB, CREB or TBP. (C) Confocal images of control HL-1 cells with or without mCAT transfection 48 hours before treatment with LPS and TNF. In some experiments, cells were treated with 20 μM EGTA-AM for 30 minutes followed by LPS and TNF for 2 hours. Cells were stained with anti-p65 (green) or with anti-pCREB (red) antibodies and nuclei were visualized with DAPI (blue).

Since mitochondrial H2O2 might be involved in stress-induced Ca2+ signaling, the effects of Ca2+ mobilization on nuclear translocation of NFκB and phosphorylated CREB were evaluated using EGTA-AM, a potent cellular Ca2+ chelator, and thapsigargin (TG), an inhibitor of Ca2+-ATPase in the ER. Since most Ca2+ chelators are short acting, HL-1 cells were pre-treated with EGTA-AM (20 μM) for 30 minutes followed by LPS and TNF for 2 hours and nuclear extracts probed for NFκB subunits by western blot. LPS- and TNF-induced nuclear translocation of p65, p50 and cRel was decreased, but not prevented by EGTA-AM (Fig. 8A), indicating a small Ca2+ effect. EGTA-AM did however block the nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated CREB (Fig. 8B).

Thapsigargin produces rapid Ca2+ efflux from the ER lumen (Thastrup et al., 1990), and in contrast to slow-acting ER stress-eliciting agents (Pahl and Baeuerle, 1995), rapidly activates NFκB (Pahl et al., 1996). If ER Ca2+ release is involved in NFκB activation after treatment with LPS and TNF, it would be important to know whether it interacts with mitochondrial H2O2 generation. HL-1 cells stimulated with TG (30 nM for 30 minutes) did activate NFκB, but mCAT transfection nearly completely blocked nuclear accumulation of p65 and cRel (Fig. 8A), implying that ER Ca2+ release stimulates mitochondrial H2O2, which ultimately mediates NFκB activation. TG also stimulated nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated CREB, and this effect was partially abrogated by mCAT (Fig. 8B).

Confocal microscopy demonstrated the LPS- and TNF-mediated nuclear translocation of p65 and phosphorylated CREB in HL-1 cells, which was inhibited by mCAT (Fig. 8C). Ca2+ chelation by EGTA-AM did not block LPS+TNF-induced nuclear p65, but did block nuclear accumulation of phosphorylated CREB; the latter together with the mCAT data implies an interaction between mitochondrial H2O2 and ER Ca2+.

Discussion

A direct link between the innate inflammatory response mediated by NFκB signaling and the transcriptional activation of mitochondrial biogenesis has not been reported previously. This work has identified active intragenic NFκB-responsive cis-elements both in the promoter and in the first intron of NRF1, a pivotal transcription factor for mitochondrial biogenesis, which enables mitochondrial gene expression during the inflammatory response. These κB elements act as transcriptional enhancers that allow the LPS-TLR4 cognate and the early-phase cytokine TNFα, to activate NRF1. Also new is the aspect of synchronization between the classical NFκB pathway and the bZIP transcription factor CREB, which is integral to the regulation of pyruvate, glycogen and fatty acid metabolism (Zhang et al., 2005). This unusual mechanism of NRF1 regulation drives NRF-1 target-gene expression during the TLR4-mediated immune response.

Because TLR4 activates NFκB (da Silva Correia and Ulevitch, 2002; Li and Verma, 2002) and can be accompanied by CREB activation (Illario et al., 2008; Martin et al., 2005), it was necessary to address direct transcription factor binding to the NRF1 locus as an explanation for LPS-mediated NRF-1 expression (Suliman et al., 2003). A bioinformatics analysis revealed κB sites spanning the NRF1 locus in both the 5′-proximal (promoter) and intronic regions. Three κB sites within intron 1 are conserved across species, and we considered these potentially crucial for NRF1 expression because interspecies-conserved regions often correspond to DNaseI HS sites (Kang and Im, 2005), which could be targets for binding of transcription factors. Therefore, we focused our analysis initially on NFκB.

By EMSA, NFκB was demonstrated to function as an enhancer element within the NRF1 locus through significant p65 and weaker cRel binding at the NRF1 promoter. ChIP analysis confirmed that the NRF1 promoter site of interest is occupied primarily by p65. GFP-reporter assays using NRF1 promoter deletion and NFκB-mutation constructs in HepG2 cells demonstrated that NFκB contributes to LPS-induced reporter activity in the mouse Nrf1 promoter. The enhancer operates efficiently with a promoter derived from the 5′-proximal region, but not with a minimal promoter. Because the 5′-proximal region includes κB-responsive elements (Saraiva et al., 2005), it cooperates with these elements to exert its enhancing effects. The discovery of a working NFκB enhancer element at intron 1 in the NRF1 gene locus is quite intriguing, because binding of NFκB to intronic elements is rare (Charital et al., 2009).

We confirmed the NFκB intronic functionality by GFP-reporter assays by co-transfecting HepG2 cells with NRF-1 reporter constructs and siRNA to knock down CREB or p65 after stimulation with LPS. These assays indicated that full NRF1 induction requires not only NFκB, but also CREB, and that these two transcription factors interact because NFκB silencing blocks the CREB effect and vice versa. It is thus possible that NFκB not only activates CREB, but that CREB participates in LPS-mediated NFκB activation for NRF1 expression.

Stress-related mtDNA damage leads to sustained mitochondrial ROS production (Suliman et al., 2005) that alters the expression of an array of genes associated with apoptotic phenotype and cell survival (Suliman et al., 2007b). Exposure to LPS alone, or LPS and TNF, in HL-1 cells activates NFκB and CREB, while stimulating the production of H2O2, a known regulator of NFκB nuclear translocation (Beg et al., 1993). In these cells, NFκB activation required mitochondrial H2O2 whereas Ca2+ had a minimal role. Mitochondrial-targeted catalase (mCAT) but not the Ca2+ chelator EGTA-AM blocked NFκB activation by the LPS signal, whereas after Ca2+ mobilization by TG, EGTA-AM, and mCAT blocked nuclear accumulation of p65 and cRel. Ca2+ chelation fully abrogated TG-mediated accumulation of phosphorylated CREB, but mCAT also partially blocked accumulation of phosphorylated CREB, placing importance on mitochondrial H2O2 in both NFκB and Ca2+-mediated CREB activation. Thus, the evidence in heart cells implicates only mitochondrial H2O2 production in the LPS- and TNF-induced nuclear translocation of NFκB and mitochondrial H2O2-associated Ca2+ mobilization in the nuclear translocation of pCREB. Both conditions are consistent with the redox regulation of NRF1 (Piantadosi and Suliman, 2006); however, the sites of intramitochondrial ROS production were not determined in this case. Moreover, the conditional participation of other redox mechanisms involving NFκB, for instance via NO and CREB (Dhakshinamoorthy et al., 2007), has not been excluded. Under comparable NFκB-activating conditions, IκK activation and accelerated loss of IκB inhibitory protein is frequently reported (Kamata et al., 2002).

Loss-of-function experiments indicated that LPS and TNF induce NRF1 transcription through NFκB-promoter and intronic-enhancement elements, thus providing an explanation for the prompt increases in NRF-1, an established integrator of nuclear-mitochondrial communication (Scarpulla, 2002), during the early phase of the antibacterial host response. Similarly, LPS and TNF increase NRF-1-regulated Tfam gene expression and subsequent increases in mtDNA-encoded COI and NDI mRNA, reflecting mitochondrial transcriptional activity befitting reports that LPS exposure doubles COI mRNA content in mouse cells (Chen et al., 2004). Following NRF-1 production, Tfam levels and mtDNA copy number also increase, which is necessary to support the capacity for oxidative phosphorylation (Scarpulla, 2008) and which might reduce oxidative stress (Stirone et al., 2005).

NRF1 induction through NFκB and CREB binding to intragenic DNA with enhancement of NRF-1-regulated Tfam transcription addresses the Tfam-regulated mitochondrial gene transcription and early mtDNA replication found in LPS-injured animals (Suliman et al., 2003), as well as the late restitution of mtDNA copy number after LPS exposure in Tlr4-null mice (Suliman et al., 2005). Tfam is required for efficient mitochondrial promoter recognition by DNA polγ, and is necessary for maintenance of oxidative phosphorylation as well as for mtDNA replication during mitochondrial proliferation (Scarpulla, 2008). The NFκB-CREB signal integration for NRF1 function also reflects a rapid optimization of mitochondrial gene expression coincident with metabolic and inflammatory stressor influences on host defense and repair through classical NFκB activation, apparently without dependence on non-canonical mechanisms (Bakkar et al., 2008).

In conclusion, NRF1 promoter co-regulation by NFκB and pCREB combinatorial interactions enhanced by p65 binding to NRF1 intron 1 and with essential regulation by mitochondrial H2O2 represents the first known mechanism by which LPS-receptor-mediated signaling engages directly in the transcriptional control of mitochondrial biogenesis. The implications for rapid mitochondrial turnover and quality control are vital to cell survival during inflammatory pathogenesis, and interference with this mechanism would place cells at consequential risk for increased apoptosis and/or necrosis, particularly during exaggerated or prolonged activation of host antibacterial defenses.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Antibodies against p65, cRel, RelB (Cell Signaling), CREB, pCREB and TBP were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. All secondary and fluorescent antibodies were from Invitrogen. The mCAT vector was developed and characterized in our laboratory (Suliman et al., 2007a; Suliman et al., 2007b). Small interfering (si) RNA oligonucleotides were from Ambion. Mouse recombinant tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF), EGTA-AM and E. coli LPS were from Sigma. Thapsigargin and BAY11-7085 were obtained from BioMol (Plymouth Meeting, PA).

Mice

The studies were pre-approved by Duke Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee; male C57BL/6 and p50−/− mice were obtained from Jackson Labs and used at 12-16 weeks of age. E. coli (serotype 086a:K61, ATCC, Rockville, MD) was non-disruptively heat-inactivated (Suliman et al., 2005). Heat-killed bacteria were diluted with sterile 0.9% NaCl to a concentration of 5×106/ml and single 0.5 ml doses injected i.p. into mice. At the appropriate times, the livers were harvested and snap-frozen. For NFκB inhibition, mice were injected with BAY11-7085 (20 mg/kg i.p. in 1% DMSO diluted with 0.9% NaCl). BAY11 was administered twice to each animal, once 6 hours before E. coli injection and then 6 hours after E. coli.

Cell studies

HepG2 (human hepatocellular carcinoma) cells purchased from ATCC were maintained in RMPI 1640 medium (Hyclone) containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Murine atrial HL-1 cells, a generous gift from William C. Claycomb (LSU Medical Center, New Orleans, LA), were cultured in Claycomb medium with 10% FBS, 100 μM norepinephrine and 4 mM L-glutamine in gelatin- or fibronectin-coated flasks or plates. Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 and 95% air. Cells were transfected with scrambled (negative control) or targeted siRNA using FuGene HD transfection reagent (Roche) and transfection efficiencies of 65-80% and gene suppression achieved. For pharmacological inhibition of NFκB in cells challenged with LPS+TNF, BAY11-7082 (5 μg/ml) was used.

Bioinformatics profiling

Mouse and human NRF1 loci were aligned and the extent of DNA sequence homology computed with the web-based Regulatory Visualization Tools for Alignment (rVISTA; www.gsd.lbl.gov/vista) (Loots and Ovcharenko, 2004; Loots et al., 2002). Promoter analysis was performed with consensus sequences for transcription factor binding located with DNASIS (Hitachi Software; Alameda, CA) and confirmed with MatInspector (Genomatix Software; München, Germany). Putative NFκB- or CREB-binding sites of 92-100% homology were identified in the NRF1 promoter and intronic region (Ensembl Gene ID ENSMUSG00000058440).

EMSA and ChIP

Nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared as described (Suliman et al., 2003; Suliman et al., 2005) and nuclear extracts were incubated with [32P]dCTP-labeled, double-stranded probes containing an NFκB consensus site from the NRF1 promoter or the putative CRE-binding sites. For competition experiments, unlabeled oligonucleotide was added 10 minutes before addition of labeled probe. For positive controls 32P-labeled probe derived from consensus for CREB or NFκB oligonucleotides (Promega) were used. For supershift experiments, 1 μg of Cell Signaling antibody to p65 (3034), cRel (4727), Rel B (4954) or Santa Cruz Biotechnology anti-CREB (sc-186X), pCREB (sc-7978X) or rabbit IgG was added to the binding reactions. Reaction products were resolved on non-denaturing 5% polyacrylamide gels, which were dried and exposed to X-ray film.

ChIP assays were performed with ChIP-IT kits (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA) using the manufacturer's protocol (Suliman et al., 2007a). Approximately 200 mg mouse liver was diced on ice, suspended in PBS, and fixed in 1% (v/v) formaldehyde at room temperature to crosslink proteins to DNA. Reactions were stopped with 0.125 M glycine and the samples centrifuged first at 3000 r.p.m. for 10 minutes and then at 7500 r.p.m. for 5 minutes, and the final pellet was suspended in ChIP buffer. Genomic DNA was sheared by sonication on ice and lysates were tumbled overnight at 4°C with salmon sperm DNA and protein-A-agarose with anti-RNA polymerase II (sc-9001X, Santa Cruz), anti-p65 (Cell Signaling) or normal rabbit IgG. Complexes were precipitated, washed serially, and eluted with fresh elution buffer (1% SDS and 100 mM NaHCO3). Na+ concentration was adjusted to 200 mM with NaCl followed by incubation at 37°C to reverse protein-DNA crosslinks. DNA was purified with a PCR purification kit (Qiagen) and then amplified across the targeted mouse Nrf1 promoter regions containing κB-binding sites. Liver extracts from Wt or BAY11 treated mice were evaluated for NFκB enrichment by quantitative real-time RT-PCR (qPCR) in 20 μl mixtures of SYBR Green master mix and 0.1 μM primers. NFκB enrichment was evaluated using primers for upstream regions of the mouse Nrf1 gene (sequences provided on request). PCR primer efficiency was determined using input DNA and adjusted accordingly. DNA in each ChIP sample was normalized to the corresponding input chromatin (ΔCt) and enrichment defined as change in Ct in treated versus untreated control samples (ΔΔCt), relative to baseline control (IgG).

Reporter constructs

Starting with mouse liver genomic DNA, the 5′-proximal region 1.5 kbp upstream of the TSS on the NRF1 locus (−1500 to +40) was amplified under standard PCR conditions and cloned into the reporter construct pGlow-TOPO (Invitrogen). The 3′ primer at +40 was 5′-GCGAGCGCTGCCGCCTCTGCC-3′ and 5′ primer, 5′-ACTTGGAAGGCAAGGACAGG-3′. To identify the regulatory sequences within −1500 to +40 region of the NRF-1, several fragments harboring 5′-end deletions of this region were generated by PCR using plasmid −1500/+40GFP as a template and region-specific primers and Pfu polymerase (Stratagene). Three PCR-amplified fragments spanning −500 to +40, −1000 to +40, and a chimera of −1000 to −700 plus −52 to +40 bp region of the NRF1 promoter upstream of the TSS were cloned in plasmid pGlow-TOPO. The constructs generated were designated p1040-Nrf1glow (GFP1), p540-Nrf1glow (GFP2) and p393-Nrf1glow (GFP3). Transformants were screened for the presence of the insert by restriction enzyme digestion and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

To test for the intronic enhancer, a fragment of intron 1 (78 bp fragment including NFκB sites) was amplified with Pfu polymerase using specific primers. The primers for intronic region amplification were the sense primer, 5′-CCTGGGTTCTTCCTGGGACT-3′ and the antisense primer, 5′-GTTCCTTCTTAAGGGGTGCGCC-3′. To generate p1040-Nrf1glow +78-intron1 (GFP4), p540-Nrf1glow+78-intron 1 (GFP5) and (p393-Nrf1glow+78-intron1 (GFP6), we cloned the intron 1 fragment (+902/+980) of the Nrf1 gene from mouse genomic DNA and then fused it downstream of the promoter driving exon 1 by the fusion PCR method and using GFP1, GFP2 and GFP3 as a template. Mutations in the intronic sequences were created by PCR-site-directed mutagenesis using plasmid GFP5 as a template. Amplified fragments were ligated directly to the 5′-proximal regions upstream of the TSS prepared in the pGlow-TOPO vector. The transformants were screened for the presence of the insert by restriction enzyme digestion and confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Transient transfection and GFP reporter assays

HepG2 cells (5×104/well) were plated in 24-well plates and incubated overnight. NRF1 promoter GFP constructs (1.0 μg) or CMV-GFP plasmid (0.1 μg, as positive control) were transfected into HepG2 cells using FuGene (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Glow-TOPO empty vector was used as a negative control (GFP0). 48 hours after transfection, cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy on a Nikon fluorescence microscope and filter with an excitation range of 480-510 nm. For fluorometric assays, cells were harvested in PBS at different times after transfection. Whole-cell pellets were resuspended in 50 μl PBS and transferred to a 96-well plate containing black wells (Labsystems). Fluorescence intensity was measured in a spectrofluorometer (Genius, Tecan) using excitation at 380 nm and emission at 510 nm corrected for background activity for the pGlow-TOPO vector alone and for cell number between experiments. All transfection data are means ± s.e. of three experiments performed in triplicate. For RNA interference, reporters and plasmids and/or siRNA (100 nM) were co-transfected into HepG2 cells with FuGene. 48 hours later, additional complete medium containing the appropriate pharmacological agent(s) was added. 24 hours after treatment, cells were washed once with PBS and the intensity of the fluorescence was measured.

Protein immunoblotting

Western blots were performed on liver and cell lysates and nuclear extracts after separation of protein by SDS-PAGE. After transfer, primary and secondary antibodies were applied and the signals developed with ECL. Band images were quantified digitally from the mid-dynamic range, and the data expressed relative to a stable reference (Piantadosi et al., 2008). For immunochemistry, cells were grown in one-well chamber slides to ~70% confluence to avoid hypoxia. After treatments, cells were washed in PBS, fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde, and washed in 1% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were labeled with primary antibodies against p65 (1:200) and pCREB (1:100) (Suliman et al., 2007b).

MtDNA copy number and respiratory proteins

MtDNA was determined by SYBR green quantitative PCR (qPCR). Fluorescence intensities were recorded and analyzed on an ABI Prism 7000 sequence-detector system (Applied Biosystems). MtDNA-encoded cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (Mtco1) and NADH dehydrogenase subunit I (Mtnd1) mRNA were quantified by RT-PCR and normalized to nuclear-encoded 18S rRNA (Suliman et al., 2007a; Suliman et al., 2007b).

Real-time PCR

qPCR was performed on an ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System with TaqMan gene expression and premix assays (Applied Biosystems). 18S rRNA served as an endogenous control. Quantification of gene expression was determined using the comparative threshold cycle CT and RQ method.

Statistics

Grouped data are expressed as the means ± s.e. for n=4-6 replicates. Statistical significance was tested with the unpaired Student's t-test or two-way analysis of variance using commercial software. Differences at P<0.05 were considered significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Craig Marshall, Susan Fields, Marta Salinas, and John Patterson for excellent technical assistance. Supported by R01 AI0664789 (C.A.P.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Adler A. S., Sinha S., Kawahara T. L., Zhang J. Y., Segal E., Chang H. Y. (2007). Motif module map reveals enforcement of aging by continual NF-kappaB activity. Genes Dev. 21, 3244-3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakkar N., Wang J., Ladner K. J., Wang H., Dahlman J. M., Carathers M., Acharyya S., Rudnicki M. A., Hollenbach A. D., Guttridge D. C. (2008). IKK/NF-kappaB regulates skeletal myogenesis via a signaling switch to inhibit differentiation and promote mitochondrial biogenesis. J. Cell Biol. 180, 787-802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beg A. A., Finco T. S., Nantermet P. V., Baldwin A. S., Jr (1993). Tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-1 lead to phosphorylation and loss of I kappa B alpha: a mechanism for NF-kappa B activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 3301-3310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron R., Ren J. M., Cadman K. S., Moore I. K., Perret P., Pypaert M., Young L. H., Semenkovich C. F., Shulman G. I. (2001). Chronic activation of AMP kinase results in NRF-1 activation and mitochondrial biogenesis. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 281, E1340-E1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charital Y. M., van Haasteren G., Massiha A., Schlegel W., Fujita T. (2009). A functional NF-kappaB enhancer element in the first intron contributes to the control of c-fos transcription. Gene 430, 116-122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Q., Yager J. D. (2004). Estrogen's effects on mitochondrial gene expression: mechanisms and potential contributions to estrogen carcinogenesis. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1028, 258-272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. Q., Delannoy M., Cooke C., Yager J. D. (2004). Mitochondrial localization of ERalpha and ERbeta in human MCF7 cells. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286, E1011-E1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Silva Correia J., Ulevitch R. J. (2002). MD-2 and TLR4 N-linked glycosylations are important for a functional lipopolysaccharide receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 1845-1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakshinamoorthy S., Sridharan S. R., Li L., Ng P. Y., Boxer L. M., Porter A. G. (2007). Protein/DNA arrays identify nitric oxide-regulated cis-element and trans-factor activities some of which govern neuroblastoma cell viability. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 5439-5451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. J., Scarpulla R. C. (1989). Interaction of nuclear factors with multiple sites in the somatic cytochrome c promoter. Characterization of upstream NRF-1, ATF, and intron Sp1 recognition sequences. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 14361-14368 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey R. S., Ushio-Fukai M., Malik A. (2008). NADPH oxidase-dependent signaling in endothelial cells: role in physiology and pathophysiology. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 11, 791-810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh S., Karin M. (2002). Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell 109, S81-S96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2008). Shared principles in NF-kappaB signaling. Cell 132, 344-362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo L., Scarpulla R. C. (2001). Mitochondrial DNA instability and peri-implantation lethality associated with targeted disruption of nuclear respiratory factor 1 in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 644-654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illario M., Giardino-Torchia M. L., Sankar U., Ribar T. J., Galgani M., Vitiello L., Masci A. M., Bertani F. R., Ciaglia E., Astone D., et al. (2008). Calmodulin-dependent kinase IV links Toll-like receptor 4 signaling with survival pathway of activated dendritic cells. Blood 111, 723-731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamata H., Manabe T., Oka S., Kamata K., Hirata H. (2002). Hydrogen peroxide activates IkappaB kinases through phosphorylation of serine residues in the activation loops. FEBS Lett. 519, 231-237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang K. H., Im S. H. (2005). Differential regulation of the IL-10 gene in Th1 and Th2 T cells. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1050, 97-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly D. P., Scarpulla R. C. (2004). Transcriptional regulatory circuits controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Genes Dev. 18, 357-368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Verma I. M. (2002). NF-kappaB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 725-734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots G. G., Ovcharenko I. (2004). rVISTA 2.0: evolutionary analysis of transcription factor binding sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W217-W221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loots G. G., Ovcharenko I., Pachter L., Dubchak I., Rubin E. M. (2002). rVista for comparative sequence-based discovery of functional transcription factor binding sites. Genome Res. 12, 832-839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin M., Rehani K., Jope R. S., Michalek S. M. (2005). Toll-like receptor-mediated cytokine production is differentially regulated by glycogen synthase kinase 3. Nat. Immunol. 6, 777-784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl H. L., Baeuerle P. A. (1995). A novel signal transduction pathway from the endoplasmic reticulum to the nucleus is mediated by transcription factor NF-kappa B. EMBO J. 14, 2580-2588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl H. L., Sester M., Burgert H. G., Baeuerle P. A. (1996). Activation of transcription factor NF-kappaB by the adenovirus E3/19K protein requires its ER retention. J. Cell Biol. 132, 511-522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi C. A., Suliman H. B. (2006). Mitochondrial transcription factor A induction by redox activation of nuclear respiratory factor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 324-333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piantadosi C. A., Carraway M. S., Babiker A., Suliman H. B. (2008). Heme oxygenase-1 regulates cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis via Nrf2-mediated transcriptional control of nuclear respiratory factor-1. Circ. Res. 103, 1232-1240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Carrozzi V. R., Nazarian A. A., Li C. C., Gore S. L., Sridharan R., Imbalzano A. N., Smale S. T. (2006). Selective and antagonistic functions of SWI/SNF and Mi-2beta nucleosome remodeling complexes during an inflammatory response. Genes Dev. 20, 282-296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryser S., Massiha A., Piuz I., Schlegel W. (2004). Stimulated initiation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) gene transcription involves the synergistic action of multiple cis-acting elements in the proximal promoter. Biochem. J. 378, 473-484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryser S., Fujita T., Tortola S., Piuz I., Schlegel W. (2007). The rate of c-fos transcription in vivo is continuously regulated at the level of elongation by dynamic stimulus-coupled recruitment of positive transcription elongation factor b. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5075-5084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saraiva M., Christensen J. R., Tsytsykova A. V., Goldfeld A. E., Ley S. C., Kioussis D., O'Garra A. (2005). Identification of a macrophage-specific chromatin signature in the IL-10 locus. J. Immunol. 175, 1041-1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpulla R. C. (2002). Nuclear activators and coactivators in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1576, 1-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scarpulla R. C. (2008). Transcriptional paradigms in Mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Physiol. Rev. 88, 611-638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen C. K., Roy S., Packer L. (1996). Involvement of intracellular Ca2+ in oxidant-induced NF-kappa B activation. FEBS Lett. 385, 58-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skaug B., Jiang X., Chen Z. J. (2009). The role of ubiquitin in NF-kappaB regulatory pathways. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 769-796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stirone C., Duckles S. P., Krause D. N., Procaccio V. (2005). Estrogen increases mitochondrial efficiency and reduces oxidative stress in cerebral blood vessels. Mol. Pharmacol. 68, 959-965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliman H. B., Carraway M. S., Welty-Wolf K. E., Whorton A. R., Piantadosi C. A. (2003). Lipopolysaccharide stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis via activation of nuclear respiratory factor-1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 41510-41518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliman H. B., Welty-Wolf K. E., Carraway M., Tatro L., Piantadosi C. A. (2004). Lipopolysaccharide induces oxidative cardiac mitochondrial damage and biogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 64, 279-288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliman H. B., Welty-Wolf K. E., Carraway M. S., Schwartz D. A., Hollingsworth J. W., Piantadosi C. A. (2005). Toll-like receptor 4 mediates mitochondrial DNA damage and biogenic responses after heat-inactivated E. coli. FASEB J. 19, 1531-1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliman H. B., Carraway M. S., Ali A. S., Reynolds C. M., Welty-Wolf K. E., Piantadosi C. A. (2007a). The CO/HO system reverses inhibition of mitochondrial biogenesis and prevents murine doxorubicin cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 3730-3741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suliman H. B., Carraway M. S., Tatro L. G., Piantadosi C. A. (2007b). A new activating role for CO in cardiac mitochondrial biogenesis. J. Cell Sci. 120, 299-308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thastrup O., Cullen P. J., Drobak B. K., Hanley M. R., Dawson A. P. (1990). Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2(+)-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 2466-2470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B., Brasier A. R. (2003). Identification of a nuclear factor kappa B-dependent gene network. Recent. Prog. Horm. Res. 58, 95-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vercauteren K., Pasko R. A., Gleyzer N., Marino V. M., Scarpulla R. C. (2006). PGC-1-related coactivator: immediate early expression and characterization of a CREB/NRF-1 binding domain associated with cytochrome c promoter occupancy and respiratory growth. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 7409-7419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virbasius C. A., Virbasius J. V., Scarpulla R. C. (1993). NRF-1, an activator involved in nuclear-mitochondrial interactions, utilizes a new DNA-binding domain conserved in a family of developmental regulators. Genes Dev. 7, 2431-2445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virbasius J. V., Scarpulla R. C. (1994). Activation of the human mitochondrial transcription factor A gene by nuclear respiratory factors: a potential regulatory link between nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression in organelle biogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 1309-1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Puigserver P., Andersson U., Zhang C., Adelmant G., Mootha V., Troy A., Cinti S., Lowell B., Scarpulla R. C., et al. (1999). Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98, 115-124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y., Buja L. M., Scarpulla R. C., McMillin J. B. (1997). Electrical stimulation of neonatal cardiomyocytes results in the sequential activation of nuclear genes governing mitochondrial proliferation and differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94, 11399-11404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H., Ma G., Lin C. H., Orr M., Wathelet M. G. (2004). Mechanism for transcriptional synergy between interferon regulatory factor (IRF)-3 and IRF-7 in activation of the interferon-beta gene promoter. Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 3693-3703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Odom D. T., Koo S. H., Conkright M. D., Canettieri G., Best J., Chen H., Jenner R., Herbolsheimer E., Jacobsen E., et al. (2005). Genome-wide analysis of cAMP-response element binding protein occupancy, phosphorylation, and target gene activation in human tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 4459-4464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong H., Voll R. E., Ghosh S. (1998). Phosphorylation of NF-kappa B p65 by PKA stimulates transcriptional activity by promoting a novel bivalent interaction with the coactivator CBP/p300. Mol. Cell 1, 661-671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]