Can one's political ideology influence one's health? Aggregate studies correlating average voting patterns with average mortality levels,1–4 or average health dissatisfaction,3 suggest that mortality tends to be lower in areas where the majority vote for the party with conservative political orientation. This finding has usually been presented as reflecting the differences in socio-economic deprivation between areas voting for a party with conservative values and areas voting for a party with liberal values.1 We are not aware of any studies that examine the association between political ideology and health at the disaggregated, individual level. In the USA, it has been shown that individuals’ political ideology correlates with the degree of importance they attach to health ‘care’,5,6 with individuals who identify as democrats assigning a higher priority on issues related to health care compared with individuals who identify as republicans.6 It is not clear, however, whether there are fundamental differences in health status and behaviours between individuals who identify with conservative and liberal political parties.

We analysed the 1972–2006 cumulative General Social Surveys (GSS) data,7 which allows an examination of health status/behaviours and political ideology at a micro level. Health status was ascertained from a question, ‘Would you say your own health, in general, is excellent, good, fair, or poor?’ For analysis, we created a binary variable with poor health = 1, 0 otherwise. Smoking status was measured based on an affirmative response to the following question, ‘Do you smoke?’. Of those reported, 5% were considered as in poor health and 35% were smokers in the weighted, pooled samples. Political ideology was based on a question, ‘Generally speaking, do you usually think of yourself as a republican, democrat, Independent, or what?’, with respondents’ choosing one of the following categories: strong democrat (15%), not very strong democrat (22%), independent near democrat (12%), independent (15%), independent near republican (9%), not very strong republican (16%), strong republican (10%) and other party (1%). For ease of presentation and interpretation, we also grouped these into democrats (49%) comprising strong democrat/not very strong democrat/independent near democrat, republicans (35%) comprising strong republican/not very strong republican/independent near republican, and independent/others (16%). We included age, sex, race, marital status, religious service attendance, highest educational degree, total family income in the last year prior to the survey and survey year as covariates. After excluding missing values on the responses and predictors, the final analytic sample consisted of 32 716 individuals for the poor-health model and 14 803 individuals for the smoking model. In the GSS, the self-rated health question was asked over 23 survey years whereas smoking was asked for 13 survey years, which accounts for the large differences in the sample sizes. We used weighted, binary logistic regression model procedures as implemented in SAS v9.1.

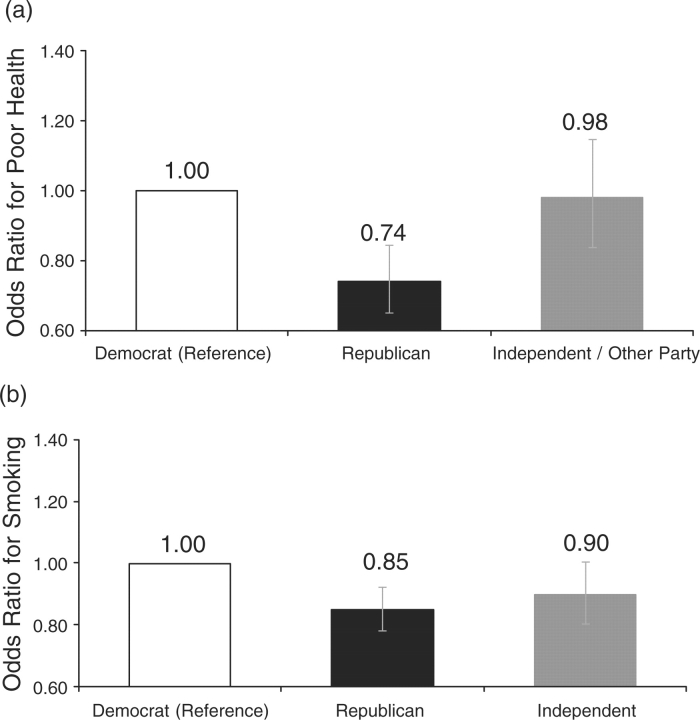

In fully adjusted models, using democrats as a reference, the odds ratio (OR) for reporting poor health for republicans was 0.74 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65, 0.85] (Figure 1a). Similarly, republicans were less likely to be smokers (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.78, 0.92) compared with democrats (Figure 1b). The ORs for reporting poor health or smoking for independent/others were not different from democrats.

Figure 1.

ORs and 95% CIs for (a) reporting poor health and (b) smoking by political ideology

Using the finer categorization of political ideology, the patterns were largely similar. In adjusted models, using ‘strong democrat’ as a reference, the OR for reporting poor health by strong republicans, not very strong republicans and independent near republicans was 0.68 (95% CI 0.55, 0.85), 0.63 (95% CI 0.51, 0.76) and 0.71 (95% CI 0.56, 0.90), respectively. The differential for not very strong democrat was not statistically, significantly different from the reference group (strong democrat). However, independent near democrats had a lower OR of reporting poor health than strong democrats (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63 and 0.95). Independents (with no democrat or republican leaning) did not have a statistically, significant differential from strong democrats. In adjusted models, using ‘strong democrat’ as a reference, the OR for reporting smoking by strong republicans, not very strong republicans and independent near republicans was 0.76 (95% CI 0.65, 0.89), 0.76 (95% CI 0.66, 0.86) and 0.81 (95% CI 0.70, 0.95), respectively. The differential for not very strong democrat was different from strong democrats (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.76, 0.97), unlike the differential for independent near democrats. Independents (with no democrat or republican leaning) had a lower OR of reporting smoking (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73, 0.96).

Our analysis suggests that there might be fundamental health differences between individuals who identify with a conservative political party and individuals who identify with a liberal political party. Specifically, individuals affiliating with the republican party report lower rates of poor health. Crucially, this association does not seem to be due to republicans, on average, having higher socio-economic status (SES) than democrats. The observation that republicans enjoy better health status may reflect the core republican value of individual responsibility, which could translate into increased adherence to health-promoting behaviours. This is indirectly supported by our analysis, which shows that, on average, republicans are less likely to be smokers compared with democrats after accounting for several factors including race/ethnicity and SES. It may also be that republicans exhibit greater religiosity (beyond attendance) compared with democrats,8 which may lead to health promoting social conditions such as enhanced social ties and networks. Alternatively, it is possible that our measures of SES (income and education) are inadequate in terms of controlling for one's SES. The effects of identifying with the republican party, however, did not alter substantially in unadjusted and adjusted models.

Our results at the disaggregated level are similar to the results seen in aggregate studies on mortality and party voting behaviour,1–4 with some exceptions. For instance, suicide rates were observed to be higher during periods of conservative government in England, Wales and Australia.9,10 In the context of the USA, our analysis suggest that perhaps the reason why republicans assign a lower priority to health care could be because they are healthier compared with democrats. Whether one's political ideology is an independent risk factor, or a marker of something else, clearly requires further research. It does not seem implausible, however, that conservative values at the individual level may be health promoting.

Acknowledgements

S.V. Subramanian is supported by the National Institutes of Health Career Development Award (NHLBI 1 K25 HL081275).

References

- 1.Davey Smith G, Dorling D. ‘I'm all right, John’: voting patterns and mortality in England and Wales, 1981–92. Br Med J. 1996;313:1573–77. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorling D, Davey Smith G, Shaw M. Analysis of trends in premature mortality by Labour voting in the 1997 general election. Br Med J. 2001;322:1336–37. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7298.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelleher C, Timoney A, Friel S, McKeown D. Indicators of deprivation, voting patterns, and health status at area level in the Republic of Ireland. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2002;56:36–44. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondrichin SV, Lester D. Voting conservative and mortality. Percept Mot Skills. 1998;87:466. doi: 10.2466/pms.1998.87.2.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blendon RJ, Brodie M, Altman DE, Benson JM, Hamel EC. Voters and health care in the 2004 election. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005:W5-86–W5-96. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blendon RJ, Altman DE, Benson JM, et al. Voters and Health Reform in the 2008 Presidential Election. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2050–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr0807717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Surveys GS. General social surveys (GSS) Nesstar's user guide—data analysis. (Accessed October 10, 2008). Available at: http://www.norc.org/GSS+Website/Data+Analysis/

- 8.Glaeser EL, Ponzetto GAM, Shapiro JM. Strategic extremism: why republicans and democrats divide on religious values. Q J Econ. 2005;120:1283–330. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page A, Morrell S, Taylor R. Suicide and political regime in New South Wales and Australia during the 20th century. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2002;56:766–72. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.10.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shaw M, Dorling D, Davey SG. Mortality and political climate: how suicide rates have risen during periods of conservative government, 1901–2000. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2002;56:723–25. doi: 10.1136/jech.56.10.723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]