The formation and interconversion of nitrogen oxides has been of interest in numerous contexts for decades. Early studies focused on gas phase reactions, particularly with regard to industrial and atmospheric environments, and on nitrogen fixation. Additionally, investigation of the coordination chemistry of nitric oxide (NO) with hemoglobin dates back nearly a century. With the discovery in the early 1980s that NO is biosynthesized as a molecular signaling agent, the literature has been focused on the biological effects of nitrogen oxides, but the original concerns remain relevant. For instance, hemoglobin has long been known to react with nitrite, but this reductase activity has recently been considered to be important to produce NO under hypoxic conditions. The association of nitrosyl hydride (HNO; also commonly referred to as nitroxyl) with heme proteins can also produce NO by reductive nitrosylation. Furthermore, HNO is considered to be an intermediate in bacterial denitrification, but conclusive identification has been elusive. The authors of this article have approached the bioinorganic chemistry of HNO from different perspectives, but have converged due to the fact that heme proteins are important biological targets of HNO.

HNO-heme adducts

Interest in HNO in the Farmer lab originated from efforts to model reductive heme-based catalysis involved in the global nitrogen cycle (Scheme 1).1 The six-electron reduction of nitrite to ammonia can be driven by a single enzyme, as in the assimilatory nitrite reductases, or can occur stepwise via the dissimilatory enzymes, which take nitrite to NO, N2O and N2. Heme nitroxyl intermediates have been postulated in these NOx reductions, as indicated by the dotted line in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Species involved in the nitrogen cycle

A common mechanistic question in enzymatic reduction of nitrogen oxides is whether a nitroxyl intermediate is generated by sequential electron transfers or by a two-electron process such as hydride transfer (Scheme 2).2, 3 The contention is that a ferrous nitrosyl intermediate (FeII-NO) if transiently formed would be stable and difficult to reduce, thus acting as a catalytic dead end. For example, the single electron reduction of NO-FeIIMb occurs at ca. -650 mV vs. NHE,4 which is at the edge of the biologically reduction range.5

Scheme 2.

Reduction of coordinated NO+ to NO and NO-

An authentic nitroxyl intermediate has been observed during turnover of the fungal NO reductase cytochrome P450nor.6 In its catalytic cycle, a ferric nitrosyl complex of P450nor is reduced by NADH to generate an intermediate (λmax at 444 nm) that subsequently reacts with NO to give ferric heme and nitrous oxide, which is the nitrogen product of the HNO self-consumption pathway.7, 8 Ulrich showed that the putative nitroxyl intermediate may be formed from reaction of NaBH4 with the ferric nitrosyl adduct,9 suggesting that nature does indeed bypass the thermodynamically stable FeII-NO in forming a reactive nitroxyl intermediate. The electronic structure, basicity and possible sites of protonation during turnover of this formal {FeII-NO}8 species has been investigated recently.10, 11 Correspondingly to the free species,12-14 Lehnert et al. found an energetic preference for the Fe-N(H)O tautomer over that of Fe-NOH in the monoprotonated form.11 The axial thiolate ligand to the P450 heme promoted a second protonation, yielding a catalytically active intermediate described as FeIV-NHOH-.11

In a recent series of papers, we have shown that an HNO adduct of ferrous myoglobin (HNO-FeIIMb) can be formed by reduction of NO-FeIIMb or by trapping of free HNO by deoxymyoglobin (FeII-Mb).15, 16 The HNO-FeIIMb adduct is relatively stable, and as a unique structural model for heme nitroxyl intermediates, it has been structurally characterized by 1H NMR,17 Resonance Raman and XAS/XANES analysis.18 The1H NMR spectrum is particularly diagnostic, with characteristic signals for HNO at 14.9 ppm and for the methyl group of Val68 at -2.5 ppm.

In the Farmer lab,19 NO-FeIIMb is generally synthesized by the common technique of mixing metmyoglobin (FeIIIMb), nitrite and dithionite (Eq. 1).20 This reaction also has physiological relevance for biosynthesis of NO.21 Ulrich's work9 prompted us to change the reductant from NaNO2 to NaBH4, in the hope of obtaining the HNO-FeII species. Indeed, the reaction of FeIIIMb with nitrite and borohydride results in a product mixture with absorbance spectra that is consistent with production of HNO-FeIIMb in >96% yield (S2-3). Similarly, sequential addition of nitrite and borohydride to hemoglobin yields HNO-FeIIHb solutions of ca. 65% yield (S4-6).

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

In contrast, independently prepared and purified NO-FeIIMb does not undergo reaction with borohydride (S8, Eqs. 1, 3). This lends credence to the supposition that NO-FeII is avoided during catalytic turnover in P450nor. This also implies that free HNO, or an HNO-releasing species, is generated upon reduction of nitrite by borohydride in aqueous solution.

A complication is that the 1H NMR spectrum of HNO-FeIIMb prepared by the nitrite/borohydride method has a doubling of the proton resonances within the heme pocket (Figure 1), suggesting a diastereomeric mixture. Neither photolysis nor heating to 60°C affects this doubling. However, if an HNO-FeIIMb sample prepared by this method is air oxidized to FeIIIMb, and the HNO-adduct is then regenerated using the trapping methodology, only single resonances are observed in the two characteristic regions. A similar doubling of resonances was previously perceived for reconstituted metmyoglobin adducts and was attributed to heme orientational disorder;22-24 the vinylic side groups of the heme are asymmetrical, and thus flipping of the heme within a protein pocket will produce two different diastereomers. To examine this hypothesis, a sample of apomyoglobin was reconstituted with the iron complex of symmetrical 2,4-dimethyl deuteroporphyrin (Scheme 3), and its HNO adduct was prepared by the nitrite/borohydride method. The resulting 1H NMR spectrum of the low concentration product solution yields single HNO and valine resonances, consistent with the heme orientational hypothesis. Further 2D NMR studies are underway to better characterize the structural differences of these diastereomeric forms.

Figure 1.

1H-NMR spectra of the HNO adduct of myoglobin (0.5-1 mM) in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 either (A) prepared by the NaNO2/NaBH4 method or (B) generated by oxidation of A, reduction to FeIIMb and subsequent reaction with the HNO donor Piloty's acid at pH 10. H15NO-FeIIMb was prepared either by (C) DTDP reduction of NO-FeIIMb or (D) by reduction with Na15NO2/NaBH4. (E) shows the HNO adduct of iron 2,4-dimethyl deuteroporphyrin (0.1 mM) reconstituted myoglobin in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.

Scheme 3.

2,4-dimethyl deuteroporphyrin

To better understand how HNO adducts are formed in the nitrite/borohydride procedure, the three reactants were combined sequentially in several ways (S1a). HNO-FeIIMb was formed when either met or deoxymyoglobin was reacted with nitrite and borohydride in any addition order. One plausible reaction of hydride with nitrite is the generation of free HNO, which might then be trapped by FeII-Mb (Eqs. 4 and 5).

| (4) |

| (5) |

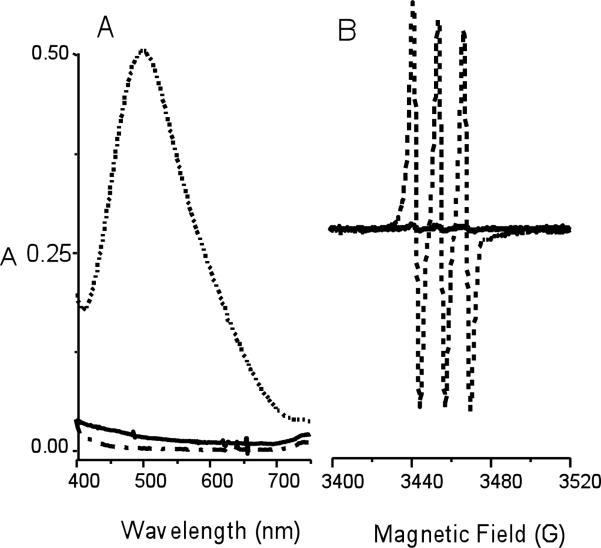

The possible generation of free HNO was examined with the known scavengers nickel(II)tetracyanate (Ni(CN)42-)25 and iron(II) N-methyl-D-glucamine dithiocarbamate (FeIIMGD)26 (Eqs. 6, 7). The characteristic 498 nm absorbance band of Ni(CN)3NO3- was observed when Ni(CN)42- was reacted with nitrite/borohydride (Figure 2), but was not apparent in the analogous reaction of Ni(CN)42- with nitrite/dithionite. Likewise, the reaction of FeIIMGD with nitrite/dithionite yielded a product solution whose EPR spectrum at 77 K matched that of the reported NO-FeIIMGD complex (Figure 2). Substitution of dithionite by borohydride yielded a product solution with a similar signal but at less than 5% of the intensity, suggesting that the majority of product was the diamagnetic NO--FeIIMGD species. Both reactions clearly suggest that HNO or an HNO-releasing species is formed in the presence of nitrite/borohydride.

| (6) |

| (7) |

Figure 2.

A). Electronic spectra of the reaction of K2[Ni(CN)4] (solid line) with Na2S2O4 (dash dot) and NaNO2-NaBH4 (dashed) in carbonate buffer at pH 9.4. B) X-band EPR spectra of the reaction of FeIIMGD with NaNO2/Na2S2O4 (dashed line) and NaNO2/NaBH4 (solid line) in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 at 77 K.

The versatility of using borohydride to generate HNO adducts in aqueous solutions was investigated with nitroprusside ([Fe(CN)5NO]2-), which was recently shown to undergo two sequential reductions at high pH to generate an HNO adduct ([Fe(CN)5HNO]3-) with characteristic absorbance and 1H NMR spectra.27 Reaction of borohydride with [Fe(CN)5NO]2- at pH 9 (Eq. 8) yields a product solution with the 450 nm absorbance band and 20.2 ppm resonance in the 1H NMR (Figure 3) that are consistent with the reported [Fe(CN)5HNO]3- complex. Thus, use of borohydride provides a convenient route to HNO complexes in a one-flask reaction using simple chemical reagents, rather than the laborious stepwise procedures previously utilized.

| (8) |

Figure 3.

Absorbance spectrum of [Fe(CN)5HNO]3- prepared by NaBH4 reduction of Na2[Fe(CN)5NO]; inset shows the 1H-NMR spectrum of [Fe(CN)5HNO]3- (ca. 1 mM) in 50 mM phosphate buffer.

Acidity/Basicity of HNO-metal adducts

In 1970, the pKa of HNO in solution was estimated at 4.7, but more recent work showed the value to be ~11.5.28, 29 Coordination to a cationic metal ion should lower the pKa of HNO, but this has been difficult to characterize in known small molecule complexes. As mentioned above, Olabe and coworkers reported generation of an HNO adduct of nitroprusside ([FeII(CN)5(HNO)]3-) by two sequential reductions of [FeII(CN)5(NO)]2- using dithionite at high pH.27 The adduct is unstable at pH 10, however lowering the pH to 7 increases stability such that an HNO resonance can be observed at 20.02 ppm (Figure 3). Analysis of the 1H NMR signal during pH titration indicated a pKa value of 7.7.

For HNO-FeIIMb, a change in the HNO resonance in the 1H NMR spectrum was not observed from pH 6.5-10, suggesting that the pKa is well above the range of the well-known acid-alkaline transition for FeIIIMb. Protein samples at higher pH are unstable over time and unsuitable for NMR studies.30 However, electronic absorption spectra of dilute samples of HNO-FeIIMb at high pH do show characterizable changes. As seen in Figure 4, the high energy band blue shifts at pHs above 11, whereas changes were not evident in the spectra of NO-FeIIMb or FeII-Mb. This suggests that the pKa of the HNO adduct is above 10 and likely close to 11.31

Figure 4.

Normalized electronic absorbance spectra of the Q-band region of HNO-FeIIMb (ca. 10 μM) at pH 7, 11 or 13.

For heme-based oxidoreductases and other metalloproteins, the influence of hydrogen bonding residues within an active site is often crucial to the mechanism of action. A recent DFT analysis of Resonance Raman data on a variety of NO adducts of heme proteins led Spiro to postulate a differential effect of hydrogen bonding to the nitrogen or oxygen atoms of the coordinated nitrosyl.32 Whereas hydrogen bonding to the oxygen atom strengthens back bonding with the metal, hydrogen bonding to the nitrogen atom weakens both the Fe-N and N-O bonds and primes the nitrosyl adduct for reduction to the HNO-FeIIMb state. Such hydrogen bonding interactions would likely play an important role in NOx reducing enzymes, such as several heme-based nitrite reductases and the P450 and binuclear iron nitric oxide reductases.33

Evidence for such interactions is observed by analysis of deuterium exchange in HNO-FeIIMb, which can be quantified by integration of the HNO peak at 14.9 ppm against that of the methyl group of Val68 at -2.5 ppm in the 1H-NMR (Figure 5). The rate of H/D exchange of HNO in HNO-FeIIMb is also quite distinctive. The exchange rate is slow at physiological pH (t1/2 ~ 5.5 h at pH 8), but increases significantly under more alkaline conditions (t1/2 is ~16 or 9 min at pH 9 or 10, respectively). This behavior may be linked to changes in hydrogen bonding interactions with the distal His64, which hydrogen bonds to the oxygen of the HNO adduct.

Figure 5.

1H-NMR assignment is shown for HNO-FeIIMb (top) and DNO-FeIIMb (bottom) samples in the HNO (left), the meso (center) and the Val68 methyl (right) regions.

Previous NMR analysis of HNO-FeIIMb found few differences between spectra collected at pH 7 or 10; notable exceptions were resonances assigned to N-H protons on the proximal His93, which shifted from 9.32 to 9.68 ppm, and that of distal His64, which at 8.11 ppm at pH 8.5 but is not observed at pH 10. Loss of this distal His64 hydrogen bonding interaction with the HNO adduct would explain the abrupt change in H/D exchange in the same pH region. As illustrated in Scheme 4, the His64 hydrogen bonding interaction promotes charge buildup on the HNO moiety via back bonding with the electron-rich FeII. This may be considered as stabilization of a resonance form with full charge delocalization onto the ligand, i.e., an FeIII-HNO- form for which the N-bound proton would be more tightly held. A similar doubly protonated form was suggested as an FeIV-NHOH- intermediate in the P450nor cycle.11 Loss of this charge stabilizing interaction at the oxygen atom may result in a lowering of the pKa of the nitrogen-bound proton and thus an increase in H/D exchange. A reviewer suggests that deprotonation of His64 may open access to the distal pocket, thus facilitating H/D exchange.34

Scheme 4.

HNO as an O2 analogue

HNO is the simplest analogue of alkylnitroso compounds (RNO), which have long been known to bind to ferrous heme proteins.35, 36 Mansuy and coworkers were the first to describe the binding of RNO compounds to Mb and Hb,37 as well as to make the analogy of RNO binding to that of dioxygen.38 Although quite rare, a small number of well-characterized organometallic HNO complexes have been identified. Several routes to HNO-metal complexes have been reported, including direct reduction of a metal nitrosyl, two-electron oxidation of a metal-hydroxylamine adduct,39, 40 insertion of NO into a metal hydride bond,41, 42 and addition of hydride to a metal bound NO.43-45 Similarly to OO-FeIIMb, all known HNO complexes are low spin d6 and diamagnetic, and all have a characteristic HNO resonance significantly downfield in the 1H NMR.46

Until this year, only FeIIMb had been shown to directly complex HNO in solution to form an identifiable HNO complex. Recently,47 other oxygen-binding proteins such as hemoglobin (Hb), leghemoglobin (legHb) and an H2S-binding hemoglobin from the clam L. pectinata were shown to readily trap free HNO in solution to form HNO adducts in good yield as characterized by peaks at ca. 15 ppm in the 1H NMR spectra. Peptidic protons in strong hydrogen bonds may also have downfield resonances, as shown in Figure 6 for the HNO adduct of hemoglobin, which has distinctive downfield resonances at ca. 12-13 ppm due to hydrogen bonds at the α and β subunit interface. Therefore, a key proof is to generate a labeled H15NO adduct, as the resulting HNO resonance will be split into a doublet by the 15N nuclear spin. 15N-labeled samples also allow Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence (HSQC) spectra to be readily obtained, which provide characterization of the 15N chemical shifts, as demonstrated in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

NMR spectrum of the HNO adduct of human hemoglobin in pH 7 phosphate buffer. At bottom is the 1H NMR spectrum A) in the HNO and B) valine regions. At top is the corresponding C) 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of H15NO adduct and D) the 2D 1H-1H NOESY spectrum showing the interaction between HNO and the valine methyl protons.

The affinity of the oxygen-binding heme proteins for both HNO and O2 also suggests that HNO might bind and/or inhibit non-heme oxygenases. For instance, HNO-precursors inhibit the pigmentation of melanogenic cells,48 which depend on the activity of tyrosinase, an oxygenase which binds O2 between two copper centers.49

HNO in mammals

Interest in HNO in mammalian systems dates to the early 1980s when vasodilation was determined to be actively mediated by an unidentified species50 designated the endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF)51. The EDRF was subsequently determined to be NO, but the identification process led to comparisons of the effects of NO and HNO donors in vasoactive assays. Such experiments were the genesis of the current expanding interest in the pharmacological effects of HNO donors. Consequently, analysis of the aqueous chemistry as well as the biochemistry of HNO has arisen in order to identify the chemical origins of the pharmacological effects. The chemical reactions of HNO under physiological conditions and their consequences in mammalian biology are beyond the scope of this review and have been presented recently elsewhere.46, 52-54 Other recent research has focused on identification of mechanisms and markers of HNO biosynthesis and on production of novel HNO donors with properties tailored for clinical use. Donor compounds are necessary not only for facile or controlled delivery but also due to the self-consumption of HNO via irreversible dehydration of the dimer.55, 56 Donors of HNO have also been recently reviewed.57, 58

About the same time that the vasoactivity of HNO was observed, Nagasawa and colleagues determined that cyanamide (H2NCN), an alcohol deterrent used in Europe, Canada, and Japan for clinical treatment of chronic alcoholism, is bioactivated by mitochondrial catalase to produce HNO.59-61

|

(9) |

Cyanamide is a potent inhibitor of aldehyde dehydrogenase (AlDH), which catalyzes the conversion of the acetaldehyde generated in the oxidative metabolism of ethanol to acetate. Inhibition of AlDH results in acetaldehydemia, provoking an unpleasant physiological response and ostensibly leading to alcohol avoidance. The inhibition mechanism involves association of HNO with an active site thiol.62

These results provided the first clinical application of an HNO donor and demonstrated that HNO donors could be administered safely and with effect to humans. Consequently, a large series of prodrugs of HNO were developed to elicit this response in vivo (see for instance 63-68). Additionally, thiols were shown to be major targets of HNO. Subsequently, the interaction of HNO with thiols was shown to lead to reversible (Eq. 11) and potentially irreversible (Eq. 12) modifications, depending on the availability of a second thiol to bind to the N-hydroxysulfenamide (RSNHOH) intermediate (Eq. 10).69-73

| (10) |

| (11) |

| (12) |

That protein thiols are able to be modified by HNO donors despite the presence of high concentrations of low molecular weight thiols such as glutathione (GSH) has now been shown in a number of systems.74-78 The mechanism by which HNO escapes scavenging by GSH is not entirely understood, but may relate to its hydrophobicity or to unique properties of protein thiols.

In a somewhat later study, Wink and coworkers demonstrated that an HNO donor (Angeli's salt) elicited significant cytotoxicty toward lung fibroblasts compared to NO donors.79 This cytotoxicty is dependent upon an aerobic environment, is exacerbated by chemical depletion of cellular GSH and is induced in part by double strand DNA breaks and base oxidation.79-83 Moreover, this comparative analysis provided the first indication that HNO could affect cellular functions by altering the redox status of the cell in a manner unique from NO. Although HNO is capable of inducing oxidative stress, it can also act as an antioxidant via facile hydrogen atom donation to oxidizing radical species (akin to tocopherol) and subsequent generation of NO, which is an established antioxidant.84 Significantly, the studies demonstrating the pro-oxidant effects were performed at high levels of HNO whereas the antioxidant properties were observed at much lower concentrations.

Later collaborative comparisons demonstrated that the in vitro toxicity of HNO could be replicated in vivo in a model of ischemia-reperfusion injury in rabbits in contrast to NO, which proved to be protective in the same model.85 Importantly, a subsequent study showed that HNO could be protective toward reperfusion injury if administered prior to the ischemic event.86 Similar O2-dependent responses to HNO were observed in neuronal channel response.87

Together, these studies led to examination of the reaction of HNO with O2, but the product has yet to be identified;79-83, 88-90 for further discussion of this reaction, see reference 52. Significantly, the autoxidation of HNO is generally too slow (103 M-1 s-1) to be of kinetic consequence in many biological systems, particularly at pharmacological levels of HNO.91, 92 Furthermore, a number of comparisons of HNO and NO donors have now appeared in the literature (reviewed in 52, 53, 91, 93-97) and nearly universally demonstrate that the physiological properties of HNO and NO are discrete.

Perhaps most importantly, the analyses by Wink and colleagues led to intensive investigation of the cardiovascular properties of HNO in dogs (reviewed in 53, 93). HNO was found to enhance myocardial contractility even in failing hearts.98, 99 As such, HNO donors may act as a novel class of vasodilators and treatments for heart failure.100 This discovery substantially increased interest in HNO and led to an accelerated publication rate. Ensuing analyses demonstrated that HNO targets key regulators of normal myocyte contractile function and increases sensitivity of myofilaments to calcium in a thiol-sensitive manner.101, 102 103

During the cardiovascular studies, Paolocci and colleagues98 determined that the vascular effects of HNO in dogs were limited to the venous side of the circulatory system unlike NO donors, which are systemic hypotensive agents. In vascular smooth muscle, NO leads to dilation by binding to the regulatory ferrous heme of soluble guanylyl cyclase (sGC), which increases the rate of conversion of GTP to cGMP. The strong trans effect of NO induces cleavage of the proximal histidine upon binding, leading to an activating conformational change (Scheme 5). The observation that infusion of HNO donors did not lead to elevated cGMP levels in plasma both indicated that HNO and NO do not interconvert in blood and renewed interest in the vasoactive mechanisms of HNO.91

Scheme 5.

Activation of sGC upon binding of NO to the regulatory heme.

Several HNO donors have been observed to induce vasorelaxation in vivo or in rodent arterial/aortic ring assays.63, 104-106 These results instigated further examination of the effects of HNO donors on sGC function, usually by measurement of cGMP levels or determination of vasorelaxive potency in the presence of sGC inhibitors.63, 104, 106-114 The question of direct activation of sGC was addressed by Dierks and Burstyn,115 who exposed partially purified bovine lung sGC to donors of NO, NO+ and HNO and observed enhanced cGMP formation only upon introduction of NO. This finding in addition to earlier examinations of the reaction of HNO with myoglobin and hemoglobin69, 116, 117 led to the assumption that HNO does not react with ferrous hemes. Kinetic analysis later suggested that the primary cellular targets for HNO are thiols and oxidized metals while NO is thought to principally interact with other free radicals and with reduced metals.91, 118

To explain the vasoactivity of HNO, the suggestion was made that HNO is converted to NO particularly in the aortic ring assays, for instance by superoxide dismutase (SOD), metHb, flavins104 or by release of normally sequestered species during tissue preparation. Furthermore, it may be that addition of millimolar DTT, which is a vital stabilizing agent for sGC due to the oxidative instability of the heme and protein thiols under aerobic conditions, scavenged HNO before it could bind to the heme. This possibility in conjunction with the demonstration by Farmer and coworkers16, 17 of the thermally stable adduct of HNO with deoxymyoglobin led the Fukuto and Miranda labs to further investigate whether HNO can directly enhance the activity of sGC using bovine lung sGC purified in the Burstyn lab.

Exposure of sGC to two structurally distinct HNO donors in thiol-free media led to a concentration-dependent increase in cGMP formation.119 The extent of activation was lower than that from NO but was significantly elevated compared to basal levels. That sGC was not affected by a metal-chelator but was modified by DTT clearly indicated that HNO can directly interact with sGC.

Both the heme and the multiple cysteine thiols of sGC are reasonable targets for HNO (Scheme 6). Removal of the heme decreased both HNO and NO-mediated activity, supporting a direct interaction with the heme for both nitrogen oxides. Surprisingly, HNO did not activate ferric sGC, which was expected to undergo reductive nitrosylation to form the ferrous heme complex (Eq. 13).

| (13) |

Ferric sGC has been previously noted to be substitutionally inert to cyanide.120 The impact of the reactivity of HNO with the protein thiols was investigated by substituting the heme with the metal-free porphyrin, which activates the enzyme to a similar extent to the ferrous nitrosyl complex.121 In this case, HNO decreased activity, suggesting that cysteine thiols can function in a negative allosteric fashion when oxidized.

Scheme 6.

Routes of activation of sGC by HNO in purified, O2-free systems

A second recent investigation122 appeared to confirm104 that HNO does not affect sGC activity unless SOD is present. We suggest that as with other studies that suggest the requirement for oxidation of HNO to NO, buffer components may be lead to unexpected scavenging of HNO. In addition to thiols, HEPES buffer has been shown previously to scavenge HNO,83 and related agents such as TEA, which was used in the recent activity studies, may have a similar effect.

Conclusion

Exposure to HNO is known to affect a variety of thiol containing proteins. That thermally stable complexes of HNO with heme proteins can now be readily produced suggests the possibility that metalloproteins may also be significant pharmacological targets for HNO. Since investigation of the chemical origin for the differing cardiovascular effects observed for HNO and NO donors in the studies by Paolocci et al. demonstrated that infusion of HNO did not result in a measurable increase in plasma levels of cGMP,91 questions remain about the role of HNO in whole organisms compared to in vitro assays or studies using excised tissues, which may have artifactual responses to HNO donors. Furthermore, whether HNO can activate sGC or coordinate to hemoglobin or myoglobin under physiological/cellular conditions remains to be determined. The coordination chemistry of HNO should be a fruitful area for both metalloprotein and small molecule chemistry for the foreseeable future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Horse skeletal muscle myoglobin (95-100%) adult human hemoglobin, sodium nitrite, sodium borohydride, sodium trimethoxyborohydride and zinc dust were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received. Piloty's acid was purchased from Cayman Chemicals. 4,4’-dimethyl-2,2’-dipyridyl (DTDP), tetracyanato nickelate,123 and N-methyl-D-glucaminedithiocarbamate26 were prepared and purified following literature procedures. Stock solutions of Piloty's acid were freshly prepared in deionized water before each experiment. Manipulation of various hemes and their adducts of NO and HNO were performed inside an anaerobic glove box. Purification of heme-adducts was carried out on a pre-equilibrated Sephadex G25 column in 50 mM phosphate buffer either at pH 7 or 9.4. All absorption spectra were recorded on a Hewlett-Packard 8453A spectrophotometer. Proton NMR experiments were recorded on Bruker Avance 600 or Varian 800 MHz spectrometers. The spectra were acquired by direct saturation of the residual water peak during the relaxation delay. Chemical shifts were referenced to the residual water peak at 4.8 ppm. X-Band EPR spectra were recorded with a Bruker EMX spectrometer equipped with a standard TE102 (ER 4102ST) or a high-sensitivity ER 4119HS resonator.

UV-Vis experiments

A sample of HNO-FeIIMb was concentrated on Centricon YM10. Several microliters were added to 2 mL of appropriate buffer (100 mM phosphate buffer for pH 7 and 8; 100 mM carbonate buffer for pH 10; appropriate concentration of NaOH with 50 mM NaCl for pH 11, 12 and 13). Spectra were collected in a glove box on a USB2000 spectrophotometer.

H/D exchange experiments

For the NMR experiments, HNO-FeIIMb was prepared using Piloty's acid, as described above. Aliquots were removed and concentrated on Centricon YM10 using 100 mM carbonate buffers at pH 10.0, 9.5, 9.0 and 100 mM phosphate buffer at pH 8.0. Two dilution concentration cycles were performed, until the pH of the solution in the waste reservoir was at the appropriate pH. The protein solution was concentrated to ~200 μL. To the bottom a J-Young tube was added 360 μL (60%) of D2O, and to the top compartment was added total of 240 μL (40 %) HNO-FeIIMb solution diluted with buffer. The solution was mixed and time course 1H NMR spectra were collected. The HNO peak was integrated and plotted versus time. For the 95+% D2O sample, the HNO-FeIIMb solution was fully exchanged with D2O in a Centricon column.

Preparation of nitrosyl heme proteins

To a micromolar solution of heme (200 μl) in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7 was added sodium nitrite. After standing for 5 min, and sodium dithionite was added at a ratio of sodium nitrite to sodium dithionite of 1:3. The nitrosyl hemes were purified on size exclusion Sephadex G25 column and then concentrated on a Amicon YM10 membrane filters.

Nitrite/borohydride preparation of HNO-FeIIMb

To a 60 mg of Mb in 2 mL of carbonate buffer pH 9.4 was added 10-20 eq of sodium nitrite followed by careful addition of either solid sodium borohydride1 (10 eq) or 200 μl of 1 M solution of sodium borohydride in 1 M sodium hydroxide. Upon addition of sodium borohydride, a visible color change from brown to red was observed, which indicated formation of HNO-FeIIMb. The reaction solution was then added to a pre-equilibrated G-25 Sephadex column in 50 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7. The fast moving dark red band was collected and concentrated on an Amicon YM10 filter.

Reaction of tetracyanatonickelate with nitrite/dithionite and nitrite/borohydride mixtures

Tetracyanatonickelate (5 mg) was dissolved in 1 ml of 50 mM carbonate buffer pH 10 in a 1 cm cuvette. After addition of sodium nitrite (1 mg) followed by sodium borohydride (2 mg), the solution immediately turned to dark purple color. The absorbance spectrum was collected with no attempt to isolate the reaction products.

Reaction of Fe(II) N-methyl-D-glucaminedithiocarbamate with nitrite-dithionite and nitrite/borohydride mixtures

Two samples of FeIIMGD (5 mg) were dissolved in separate 1 ml of 50 mM carbonate buffer pH 10 in 1 cm cuvettes; to one was added sodium nitrite (1 mg) followed by sodium borohydride (2 mg); to the other sodium nitrite (1 mg) followed by sodium dithionite (2 mg). Both reaction mixtures immediately turned dark green, and aliquots were transferred to EPR tubes and frozen. No attempt was made to purify the reaction products.

Reduction of sodium nitroprusside by sodium borohydride

Sodium nitroprusside (10 mg) was dissolved in 1 mL of 50 mM carbonate buffer. Sodium nitrite and sodium borohydride were then added, and the brick red colored solution was then used for studies without further purification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work supported by grants from National Science Foundation (PJF CHE-0100774, KMM CHE-0645818) and National Institutes of Health (PJF 1R21ES016441-01, KMM R01-GM076247).

Footnotes

Sodium borohydride is highly reactive white solid powder that violently reacts with water and aid combustion, so proper protection and care should be taken while handling it.

Supporting Information Available: Additional experimental details and figures. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Blair E, Sulc F, Farmer PJ. Biomimetic NOx Reductions by Heme Models and Proteins. In: Zagal JH, Bedioui F, Dodelet J-P, editors. N4-Macrocyclic Metal Complexes. Springer; New York: 2006. pp. 149–190. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Einsle O, Messerschmidt A, Huber R, Kroneck PMH, Neese F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11737–11745. doi: 10.1021/ja0206487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silaghi-Dumitrescu R. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003:1048–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayachou M, Lin R, Cho W, Farmer PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9888–9893. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo M, Sulc F, Ribbe MW, Immoos CE, Farmer PJ, Burgess BK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12100–12101. doi: 10.1021/ja026478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiro Y, Fujii M, Iizuka T, Adachi S, Tsukamoto K, Nakahara K, Shoun H. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:1617–1623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiro Y, Fujii M, Isogai Y, Adachi S, Iizuka T, Obayashi E, Makino R, Nakahara K, Shoun H. Biochemistry. 1995;34:9052–9058. doi: 10.1021/bi00028a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakahara K, Tanimoto T, Hatano K, Usuda K, Shoun H. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:8350–8355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daiber A, Nauser T, Takaya N, Kudo T, Weber P, Hultschig C, Shoun H, Ullrich V. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2002;88:343–352. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(01)00386-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silaghi-Dumitrescu R. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2003;6:1048–1052. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehnert N, Praneeth VKK, Paulat F. J. Comp. Chem. 2006;27:1338–1351. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruna PJ, Marian CM. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1979;67:109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guadagnini R, Schatz GC. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;102:774–783. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luna A, Merchan M, Roos BO. Chem. Phys. 1995;196:437–445. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin R, Farmer PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:2393–2394. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulc F, Immoos CE, Pervitsky D, Farmer PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1096–1101. doi: 10.1021/ja0376184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sulc F, Fleischer E, Farmer PJ, Ma DJ, La Mar GN. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2003;8:348–352. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Immoos CE, Sulc F, Farmer PJ, Czarnecki K, Bocian DF, Levina A, Aitken JB, Armstrong RS, Lay PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:814–815. doi: 10.1021/ja0433727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pervitsky D, Immoos C, van der Veer W, Farmer PJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:9590–9591. doi: 10.1021/ja073420y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnold EV, Bohle DS. In: Methods Enzymol. Packer L, editor. Vol. 268. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 41–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gladwin MT, Kim-Shapiro DB. Blood. 2008;112:2636–2647. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-115261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tran AT, Kalish H, Balch AL, La Mar GN. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2000;5:624–633. doi: 10.1007/s007750000145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.La Mar GN, Hauksson JB, Dugad LB, Liddell PA, Venkataramana N, Smith KM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991:1544–1550. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jue T, Krishnamoorthi R, La Mar GN. 1983. pp. 5701–5703.

- 25.Bonner FT, Akhtar MJ. Inorg. Chem. 1981;20:3155–3160. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia Y, Cardounel AJ, Vanin AF, Zweier JL. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;29:793–797. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Montenegro AC, Amorebieta VT, Slep LD, Martin DF, Roncaroli F, Murgida DH, Bari SE, Olabe JA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2009;48:4213–4216. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartberger MD, Liu W, Ford E, Miranda KM, Switzer C, Fukuto JM, Farmer PJ, Wink DA, Houk KN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:10958–10963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162095599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shafirovich V, Lymar SV. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002;99:7340–7345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112202099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagao S, Hirai Y, Suzuki A, Yamamoto Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4146–4147. doi: 10.1021/ja043975i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sulc F. Dissertation. University of California; Irvine: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu C, Spiro TG. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:613–621. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0349-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson SJ, Richardson DJ. Adv. Photosyn. Resp. 2004;16:169–206. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye X, Yu A, Champion PM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:1444–1445. doi: 10.1021/ja057172m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Richter-Addo GB. Accounts Chem. Res. 1999;32:529–536. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J, Chen L, West AH, Richter-Addo GB. 2002. pp. 1019–1065. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Mansuy D, Battioni P, Chottard JC, Lange M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:6441–6443. doi: 10.1021/ja00461a046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mansuy D, Battioni P, Chottard JC, Riche C, Chiaroni A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:455–463. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Melenkivitz R, Hillhouse GL. Chem. Commun. 2002:660–661. doi: 10.1039/b111645b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Southern JS, Green MT, Hillhouse GL, Guzei IA, Rheingold AL. Inorg. Chem. 2001;40:6039–6046. doi: 10.1021/ic010669m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marchenko AV, Vedernikov AN, Dye DF, Pink M, Zaleski JM, Caulton KG. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:4087–4089. doi: 10.1021/ic025699j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchenko AV, Vedernikov AN, Dye DF, Pink M, Zaleski JM, Caulton KG. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:351–360. doi: 10.1021/ic0349407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Southern JS, Hillhouse GL, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:12406–12407. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melenkivitz R, Southern JS, Hillhouse GL, Concolino TE, Liable-Sands LM, Rheingold AL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:12068–12069. doi: 10.1021/ja0277475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sellmann D, Gottschalk-Gaudig T, Haussinger D, Heinemann FW, Hess BA. Chem.-Eur. J. 2001;7:2099–2103. doi: 10.1002/1521-3765(20010518)7:10<2099::aid-chem2099>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farmer PJ, Sulc F. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2005;99:166–184. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar MR, Pervitsky D, Chen L, Poulos T, Kundu S, Hargrove MS, Rivera EJ, Diaz A, Colon JL, Farmer PJ. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5018–5025. doi: 10.1021/bi900122r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ganesan AK, Ho H, Bodemann B, Petersen S, Aruri J, Koshy S, Richardson Z, Le LQ, Krasieva T, Roth MG, Farmer PJ, White MA. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mayer AM. Phytochemistry. 2006;67:2318–2331. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Furchgott RF, Zawadzki JV. Nature. 1980;288:373–376. doi: 10.1038/288373a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Furchgott RF, Cherry PD, Zawadzki JV, Jothianandan D. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1984;6:S336–S343. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198406002-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miranda KM. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2005;249:433–455. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wink DA, Miranda KM, Katori T, Mancardi D, Thomas DD, Ridnour LA, Espey MG, Feelisch M, Colton CA, Fukuto JM, Pagliaro P, Kass DA, Paolocci N. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circul. Physiol. 2003;285:H2264–H2276. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00531.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fukuto JM, Dutton AS, Houk KN. Chembiochem. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith PAS, Hein GE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960;82:5731–5740. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kohout FC, Lampe FW. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965;87:5795–5796. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miranda KM, Nagasawa HT, Toscano JP. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2005;5:649–664. doi: 10.2174/1568026054679290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.King SB, Nagasawa HT. Methods Enzymol. 1999;301:211–220. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(99)01084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DeMaster EG, Shirota FN, Nagasawa HT. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1984;122:358–365. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)90483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.DeMaster EG, Nagasawa HT, Shirota FN. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 1983;18:273–277. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(83)90185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nagasawa HT, DeMaster EG, Redfern B, Shirota FN, Goon DJ. J. Med. Chem. 1990;33:3120–3122. doi: 10.1021/jm00174a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeMaster EG, Redfern B, Nagasawa HT. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998;55:2007–2015. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(98)00080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fukuto JM, Hszieh R, Gulati P, Chiang KT, Nagasawa HT. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;187:1367–1373. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90453-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee MJC, Nagasawa HT, Elberling JA, DeMaster EG. J. Med. Chem. 1992;35:3648–3652. doi: 10.1021/jm00098a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nagasawa HT, Yost Y, Elberling JA, Shirota FN, DeMaster EG. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993;45:2129–34. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(93)90026-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nagasawa HT, Kawle SP, Elberling JA, Demaster EG, Fukuto JM. J. Med. Chem. 1995;38:1865–1871. doi: 10.1021/jm00011a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Conway TT, DeMaster EG, Lee MJC, Nagasawa HT. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:2903–2909. doi: 10.1021/jm980200+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lee MJC, Shoeman DW, Goon DJW, Nagasawa HT. Nitric Oxide. 2001;5:278–287. doi: 10.1006/niox.2001.0349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Doyle MP, Mahapatro SN, Broene RD, Guy JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:593–599. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Turk T, Hollocher TC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1992;183:983–988. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80287-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wong PSY, Hyun J, Fukuto JM, Shirota FN, DeMaster EG, Shoeman DW, Nagasawa HT. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5362–5371. doi: 10.1021/bi973153g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shoeman DW, Nagasawa HT. Nitric Oxide. 1998;2:66–72. doi: 10.1006/niox.1998.0166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shoeman DW, Shirota FN, DeMaster EG, Nagasawa HT. Alcohol. 2000;20:55–59. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(99)00056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sidorkina O, Espey MG, Miranda KM, Wink DA, Laval J. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;35:1431–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2003.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cook NM, Shinyashiki M, Jackson MI, Leal FA, Fukuto JM. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003;410:89–95. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(02)00656-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim WK, Choi YB, Rayudu PV, Das P, Asaad W, Arnelle DR, Stamler JS, Lipton SA. Neuron. 1999;24:461–469. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80859-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ascenzi P, Bocedi A, Gentile M, Visca P, Gradoni L. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1703:69–77. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2004.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lopez BE, Rodriguez CE, Pribadi M, Cook NM, Shinyashik i. M., Fukuto JM. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005;442:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2005.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wink DA, Feelisch M, Fukuto J, Christodoulou D, Jourd'heuil D, Grisham MB, Vodovotz Y, Cook JA, Krishna M, DeGraff WG, Kim S, Gamson J, Mitchell JB. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1998;351:66–74. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ohshima H, Gilibert I, Bianchini F. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;26:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00327-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ohshima H, Yoshie Y, Auriol S, Gilibert I. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998;25:1057–1065. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Chazotte-Aubert L, Oikawa S, Gilibert I, Bianchini F, Kawanishi S, Ohshima H. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:20909–20915. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.30.20909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Miranda KM, Yamada K, Espey MG, Thomas DD, DeGraff W, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC, Colton CA, Wink DA. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;401:134–144. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lopez BE, Shinyashiki M, Han TH, Fukuto JM. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2007;42:482–491. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ma XL, Gao F, Liu GL, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Fukuto JM, Wink DA, Feelisch M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1999;96:14617–14622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pagliaro P, Mancardi D, Rastaldo R, Penna C, Gattullo D, Miranda KM, Feelisch M, Wink DA, Kass DA, Paolocci N. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Colton CA, Gbadegesin M, Wink DA, Miranda KM, Espey MG, Vicini S. J. Neurochem. 2001;78:1126–1134. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Miranda KM, Espey MG, Yamada K, Krishna M, Ludwick N, Kim S, Jourd'heuil D, Grisham MB, Feelisch M, Fukuto JM, Wink DA. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:1720–1727. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miranda KM, Dutton AS, Ridnour LA, Foreman CA, Ford E, Paolocci N, Katori T, Tocchetti CG, Mancardi D, Thomas DD, Espey MG, Houk KN, Fukuto JM, Wink DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:722–731. doi: 10.1021/ja045480z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002;402:166–171. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Miranda KM, Paolocci N, Katori T, Thomas DD, Ford E, Bartberger MD, Espey MG, Kass DA, Feelisch M, Fukuto JM, Wink DA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:9196–9201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1430507100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liochev SI, Fridovich I. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2003;34:1399–1404. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00111-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pagliaro P. Life. Sci. 2003;73:2137–2149. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00593-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Paolocci N, Jackson MI, Lopez BE, Miranda K, Tocchetti CG, Wink DA, Hobbs AJ, Fukuto JM. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007;113:442–458. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Irvine JC, Ritchie RH, Favaloro JL, Andrews KL, Widdop RE, Kemp-Harper BK. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008;29:601–608. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Flores-Santana W, Switzer C, Ridnour LA, Basudhar D, Mancardi D, Donzelli S, Thomas DD, Miranda KM, Fukuto JM, Wink DA. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2009;32:1139–1153. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1805-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Switzer CH, Flores-Santana W, Mancardi D, Donzelli S, Basudhar D, Ridnour LA, Miranda KM, Fukuto JM, Paolocci N, Wink DA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:835–840. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Paolocci N, Saavedra WF, Miranda KM, Martignani C, Isoda T, Hare JM, Espey MG, Fukuto JM, Feelisch M, Wink DA, Kass DA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:10463–10468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181191198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Paolocci N, Katori T, Champion HC, St. John ME, Miranda KM, Fukuto JM, Wink DA, Kass DA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:5537–5542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0937302100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Feelisch M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:4978–4980. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031571100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Cheong E, Tumbev V, Abramson J, Salama G, Stoyanovsky DA. Cell Calcium. 2005;37:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tocchetti CG, Wang W, Froehlich JP, Huke S, Aon MA, Wilson GM, Di Benedetto G, O'Rourke B, Gao WD, Wink DA, Toscano JP, Zaccolo M, Bers DM, Valdivia HH, Cheng H, Kass DA, Paolocci N. Circ. Res. 2007;100:96–104. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000253904.53601.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dai T, Tian Y, Tocchetti CG, Katori T, Murphy AM, Kass DA, Paolocci N, Gao WD. J. Physiol. 2007;580:951–960. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fukuto JM, Hobbs AJ, Ignarro LJ. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;196:707–713. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Murphy ME, Sies H. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1991;88:10860–10864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.23.10860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fukuto JM, Chiang K, Hszieh R, Wong P, Chaudhuri G. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;263:546–551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pino RZ, Feelisch M. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1994;201:54–62. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ellis A, Lu H, Li CG, Rand MJ. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:521–528. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.VanUffelen BE, Van der Zee J, de Koster BM, VanSteveninck J, Elferink JGR. Biochem. J. 1998;330:719–722. doi: 10.1042/bj3300719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ellis A, Li CG, Rand MJ. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;129:315–322. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wanstall JC, Jeffery TK, Gambino A, Lovren F, Triggle CR. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:463–472. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Costa G, Labadia A, Triguero D, Jimenez E, Garcia-Pascual A. Naunyn-Schmied. Arch. Pharmacol. 2001;364:516–523. doi: 10.1007/s002100100480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Irvine JC, Favaloro JL, Kemp-Harper BK. Hypertension. 2003;41:1301–1307. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000072010.54901.DE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Andrews KL, Irvine JC, Tare M, Apostolopoulos J, Favaloro JL, Triggle CR, Kemp-Harper BK. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2009;157:540–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dierks EA, Burstyn JN. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51:1593–1600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(96)00078-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Bazylinski DA, Hollocher TC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:7982–7986. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Doyle MP, Mahapatro SN. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:3678–3679. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Miranda KM, Nims RW, Thomas DD, Espey MG, Citrin D, Bartberger MD, Paolocci N, Fukuto JM, Feelisch M, Wink DA. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2003;93:52–60. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00498-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Miller TW, Cherney MM, Lee AJ, Francoleon NE, Farmer PJ, King SB, Hobbs AJ, Miranda KM, N. BJ, Fukuto JM. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:21788–21796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.014282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stone JR, Sands RH, Dunham WR, Marletta MA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3258–3262. doi: 10.1021/bi952386+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wolin MS, Wood KS, Ignarro LJ. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:13312–13320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zeller A, Wenzl MV, Beretta M, Stessel H, Russwurm M, Koesling D, Schmidt K, Mayer B. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009;76:1115–1122. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.059915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Jószai R, Beszeda I, Bényei A, Fischer A, Kovács M, Maliarik M, Nagy P, Shchukarev A, Tóth I. Inorg. Chem. 2005;44:9643–96451. doi: 10.1021/ic050352c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.