Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To examine the educational benefits of international elective rotations during graduate medical education.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS: We studied Mayo International Health Program (MIHP) participants from April 1, 2001, through July 31, 2008. Data from the 162 resident postrotation reports were reviewed and used to quantitatively and qualitatively analyze MIHP elective experiences. Qualitative analysis of the narrative data was performed using NVivo7 (QRS International, Melbourne, Australia), a qualitative research program, and passages were coded and analyzed for trends and themes.

RESULTS: During the study period, 162 residents representing 20 different specialties were awarded scholarships through the MIHP. Residents rotated in 43 countries, serving over 40,000 patients worldwide. Their reports indicated multiple educational and personal benefits, including gaining experience with a wide variety of pathology, learning to work with limited resources, developing clinical and surgical skills, participating in resident education, and experiencing new peoples and cultures.

CONCLUSION: The MIHP provides the structure and funding to enable residents from a variety of specialties to participate in international electives and obtain an identifiable set of unique, valuable educational experiences likely to shape them into better physicians. Such international health electives should be encouraged in graduate medical education.

This program provides the structure and funding to enable residents from various specialties to participate in international electives and obtain an identifiable set of unique, valuable educational experiences. Such electives should be encouraged in graduate medical education.

Residents have many opportunities for international health experiences during their training. These vary between short-term international electives, research projects, and global health tracks in many family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatric residency programs.1 Several articles have suggested that medical students desire international experiences during residency and that they select their residency program based in part on their ability to do an international health elective during residency.2,3 Residents' desire for more international health experiences has drawn investigators to further evaluate whether offering international electives provides benefit beyond the perceived benefit in recruitment.

Most data regarding residents involved in international health electives come from 2 survey-based studies of international health programs offered to internal medicine residents.4,5 These 2 studies primarily addressed career choices after residency, finding that participants in international health electives were more likely than nonparticipants to care for immigrants and patients on public assistance and were more likely to pursue careers in general medicine and public health. They also showed that residents who participated in international health electives had a higher opinion of the physical examination as a diagnostic tool.4 Several studies have shown a similar impact of these electives on medical student professional and educational development.6,7 However, few studies have assessed the immediate educational and personal benefits of international health electives for residents.

The Mayo International Health Program (MIHP) was created to give residents enrolled in graduate medical education training programs at Mayo Clinic the opportunity to spend a 1-month international elective in a medically underserved location. This program is unique in that it provides funding and supervision across all residencies and all specialties within the Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education. Since the program's initiation, the MIHP has obtained narrative reports from all program participants. The MIHP's goals are to “help residents and fellows: (1) provide valuable care to underserved patients, (2) promote increased cultural awareness, (3) provide exposure to the diagnosis and treatment of diseases not usually seen in modern Western medicine, (4) increase awareness of cost-effective care in a setting of limited resources, (5) promote improvement of history and physical examination skills, [and] (6) provide opportunities for research.”8 We sought to assess the impact of this program from its creation in 2001 through July 31, 2008, and to determine its degree of success in achieving its stated goals. Through this analysis, we want to provide a model for resident international electives and gain insight into the educational and personal benefits of international health electives in graduate medical education in a variety of specialties, thus providing guidance for further research on this topic.

PARTICIPANTS AND METHODS

Overview of the Program

The MIHP was developed in 2001 as a means to facilitate resident involvement in global health in the context of elective training in graduate medical education programs (for a more detailed overview of the program, see the MIHP Web site8). Pilot funding was originally provided by the Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education in cooperation with the Mayo Fellows Association, a peer representation group for all Mayo trainees. With the exception of the first 2 years of operation, the program has been fully supported by gifts from generous donors. Scholarships of up to $2000 are available to residents and fellows from all Mayo Clinic graduate medical education programs (Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota) to facilitate international health electives.

The application process begins in the spring before the academic year of the international elective, and therefore all residents use elective time after their first year. The application includes information regarding the sponsoring institution, insurance coverage, estimated budget, travel/housing arrangements, clinical roles and responsibilities, and completion of a Travel Risk Assessment Form (based on US Department of State travel warnings). Approval of the program director is required to ensure that trainees are in good standing with their program and have available elective time to participate in the rotation.

In choosing a site, applicants may (1) go to an MIHP-designated site, (2) set up a rotation through an MIHP contact, or (3) choose an independent site via their own contacts. The 4 designated sites are St. Mary's Mission Hospital in Nairobi, Kenya9; Hospital Albert Schweitzer in Deschapelles, Haiti10; Patan Hospital in Kathmandu, Nepal11; and Nyakato Health Center in Mwanza, Tanzania.12 These programs have been selected as educationally beneficial sites with established mentors engaged in supervision and evaluation of residents, and the program information is listed on the MIHP Intranet Web site. Interested residents may also draw on other MIHP contacts in India, Jamaica, and Mexico. For independent sites, the resident must identify the site, find an onsite mentor, and show that the site provides care to an underserved population. The onsite mentor must provide a brief description of the clinical responsibilities and acknowledge his or her role in mentorship of the resident. The educational value, appropriate mentorship, and safety of the rotation are reviewed by the MIHP selection committee and approved or denied accordingly.

The MIHP selection committee is composed of physicians with international health experience. The committee includes 12 faculty members from a variety of specialties representing all 3 Mayo Clinic campuses, as well as resident and fellow representatives, a program administrator, and a liaison to the Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education and the Mayo Fellows Association. The committee meets each spring to review applications and select residents to receive scholarship funding. Once residents have been selected to receive a scholarship, they must complete the following before disbursement of the funds: (1) visit the institutional travel clinic for appropriate vaccinations and preventive medications, (2) complete an off-campus approval form for rotation approval by the School of Graduate Medical Education, and (3) submit a final Travel Warning Risk Assessment Form based on the US Department of State Web site13 (this is required again in case the safety in the country has changed since the original application). Once these have been completed, half of the scholarship amount is awarded. On return from the trip, each trainee must complete a rotation report, which outlines the details of the trip and provides a narrative of the experience. On completion and approval of this report, the second half of the award is disbursed.

The Postelective Report

The purpose of the postelective report is to collect residents' experiences and provide information for future participants. Each report contains information about the rotation location, organization, rotation mentor, and a case log of all the patients and diseases that residents encountered. The residents also are asked the following systems-based improvement question: “Are there areas of our health care system (local or national) that could be improved based on your reflections on your MIHP experience?” Residents are given the following open-ended instructions: “[Provide a] minimum one page description of your experience. Please include a statement indicating how this experience impacted you either personally and/or professionally. Include tips for other fellows/residents if they should choose to go to this site.”

Also included in the report are some practical questions about housing, safety, licensure, and recommended items to bring, aimed at informing future residents who would be interested in traveling to the same site for future MIHP rotations.

Data Collection

Rotation reports were collected for every resident trip from the inception of the program in 2001 through July 31, 2008, and were available for review on the MIHP internal Web site. All 162 reports were downloaded from the MIHP Web site, converted from Adobe Acrobat format to Microsoft Word, and uploaded into a MIHP project folder for analysis using the qualitative research program NVivo7 (QRS International, Melbourne, Australia).14 This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analyses

Quantitative data were collected and organized to display the number of countries and patients served and to provide information on resident training program and specialty.

The primary author (A.P.S.), who was trained formally in the use of NVivo7 software, read all of the reports and created a memorandum for each report containing a list of basic themes that were generated during the read-through. The reports were then reviewed, and the passages relating to the identified themes were coded within the text. The themes were categorized by educational and personal benefits and then tabulated using NVivo7, identifying the frequency with which each theme occurred among the reports. The most common themes (noted in ≥10% of all reports) were organized into groupings of educational and personal benefits, and their frequency of occurrence was determined.

A second author (S.P.M.) reviewed a random sample of reports (5%), took the major themes identified by the primary author and documented them within each report, and reported additional themes within the reports. A comparison of the agreement between authors was made. The primary (A.P.S.) and secondary reviewer agreed on all major themes, with no additional major themes discovered, indicating that the evaluation of the primary reviewer was adequate for the remainder of the reports. The passages from each theme were reviewed, and representative passages were chosen for the Results section of this article.

RESULTS

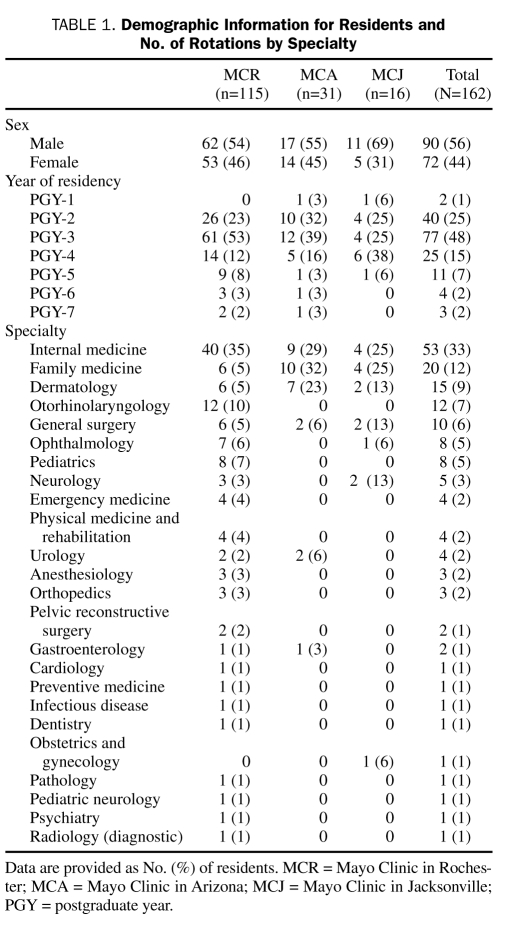

From its inception in 2001 through July 31, 2008, 162 residents have travelled to 43 different countries on 5 continents, caring for over 40,000 patients worldwide (Figure). Residents from 3 training facilities (Mayo Clinic in Arizona, Florida, and Minnesota) and from 20 specialties have participated in the MIHP, in both inpatient and outpatient settings (Table 1).

FIGURE.

Map of countries served by the Mayo International Health Program. Residents have served through this program in the countries highlighted in black. The numbers in parentheses indicate the number of residents who have had international health electives in the country. The total number equals 163 because 1 resident went to 2 countries in a single trip (Italy, Ethiopia). (Map function courtesy of http://english.freemap.jp.)

TABLE 1.

Demographic Information for Residents and No. of Rotations by Specialty

Qualitative Analysis of Postelective Reports

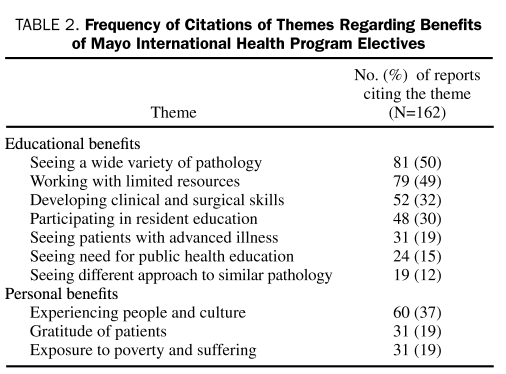

Most postelective reports were similar in length (1-3 pages) and relatively uniform in tone; however, some were more reflective and others more descriptive. The open-ended nature of the report allowed for a rich and varied discussion of important themes pertaining to the overall impact of the international health electives. Although most identified themes related to the educational and personal impact of the trip, residents were free to discuss any topics that affected them during their experience (Table 2). The response to the systems-based practice question was variable, and these responses were not included in the analysis.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of Citations of Themes Regarding Benefits of Mayo International Health Program Electives

Wide Variety of Pathology

Half of the residents reported benefit from seeing a wide variety of pathology and gaining experience with new disease entities and therapies. A resident in dermatology summarized the educational impact well in his statement:

The education gleaned from this experience was immeasurable. I saw dozens of diseases that I will probably never see in the United States. As I was directly involved in treating these patients, I was constantly reading and studying to learn how to better treat these patients. As I have plans to do humanitarian medical care at least yearly in developing countries, this was an invaluable experience in gaining exposure to a very high-need population with a huge variety of pathology.

A resident specializing in ears, nose, and throat shared the following sentiment:

The wide diversity of pathology and sheer volume of patients was invaluable in solidifying my cleft surgical skills and providing me with a stable foundation on which to grow my skills.

Not only did residents learn about new diseases, but they gained fresh perspective on familiar disease entities by treating patients who presented with advanced illness or by trying out different treatment approaches. Across the spectrum of specialties, the residents remarked on the educational importance of seeing both familiar and unfamiliar diseases, particularly diseases of higher prevalence in underserved areas, including tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus infection and AIDS, tropical infectious diseases, malnutrition, and poor hygiene.

Limited Resources

Residents reported benefiting from learning to work with limited resources and making decisions about resource allocation and cost-effectiveness of care. The limitation of resources ranged from facilities and equipment to laboratory evaluation and treatments. To some residents, working with limited resources brought frustration:

Despite my ability to adapt to the situation that I was in by the end of my time there, I still often felt frustrated by my inability to provide care that I knew existed and was readily available in other parts of the world.

Residents contrasted the scanty resources to the abundant ones available in the United States and realized how they could impact their host institution. One internal medicine resident reflected on his experience in South Africa:

I felt that in this place it was impossible to make any difference. It has been a real struggle to use my skills and experience in such a complicated and dysfunctional system. But precisely for this reason my role as person as well as my contribution as a physician were exalted.

Residents in surgery had to work with unfamiliar operating room conditions and equipment:

The surgeries themselves were interesting, but often fraught with frustration at the lack of modern conveniences that we take for granted in the United States—good lighting, climate control (air conditioning), functional equipment, and an abundance of linens, medications, and other material goods. Even these frustrations, however, provided useful lessons in concentration, determination, creativity, and appreciation for what we have in the U.S.

Many of the other lessons learned grew out of the challenge of working with limited resources.

Clinical and Surgical Skills

Residents developed their clinical skills, having to rely more often on history and physical examination findings than on diagnostic tests. One internal medicine resident summarized this well:

From a medical education standpoint, the [MIHP] participant will hone his or her physical exam skills and be pushed to the limit of their medical knowledge. The only diagnostic tools available are a blood pressure cuff, glucometer, thermometer, oto/ophthalmoscope, urine dipstick, vaginal speculum, and a stethoscope. Reliance on laboratory and imaging is non-existent and the physician must use his or her clinical judgment to make a diagnosis. In many respects it is medicine in its purest form.

The intersection between limited diagnostic testing and clinical skills was commented on by 2 pediatric residents, who noted that “The rotation definitely increased my confidence in my physical examination skills, forcing me to remember and rely on my history and physical examination alone,” and “I learned to trust my clinical skills and analyze the cost effectiveness of various tests. It was a very insightful trip.” A decreased reliance on laboratory and imaging testing improved residents' confidence in their clinical skills and decision-making and gave them a perspective on resource utilization and justification for testing.

Surgical residents gained confidence and learned new surgical techniques through experience, performing surgery in challenging environments. One resident specializing in the ears, nose, and throat reflected:

From a professional standpoint, cleft lip and palate surgery utilizes a multitude of soft-tissue surgery techniques and provides an unparalleled opportunity to hone facial surgery skills.

An ophthalmology resident made the following comment on technique:

Under the judicious supervision of [my mentor], I learned the cataract extraction technique used in most of the developing world, but no longer practiced much in North America, due to our fortunate access to technological developments. Nevertheless, the advanced nature of the cataracts we operated on would not have been amenable to our modern cataract extraction techniques.

Resident Education

Residents participated in formal education internationally, receiving education within international health systems and participating in teaching international residents and students. One dermatology resident highlighted the educational experience by stating:

One of my favorite things about the rotation was Chacagem. This is somewhat like grand rounds or hall conference, and is a time where the residents present all of the patients they have seen during the day to the attending physicians and other residents. Here, the skin condition is presented and further work-up and treatments are discussed among the group. A lot of teaching also occurs during this time, as the attending physicians point out clinical findings that the patients have and offer differential diagnoses.

A family medicine resident felt enriched by his host institution's “great emphasis on learning by lectures and direct patient contact,” commenting that:

Most of Wednesday and Thursday mornings was devoted towards didactics in the form of Grand rounds, ‘interesting case’ presentations, and lectures. There were Microbiology rounds on Friday afternoon where I saw slides of specimens that are hard to find even in textbooks in the USA.

The MIHP allowed residents to experience and learn from different forms of education. Many residents found it rewarding to be able to teach local physicians, residents, and allied health staff. One internal medicine resident wrote:

Soon after my arrival both young doctors and nurses were always interacting and asking me questions about patients' care, diagnostic or therapeutic dilemmas, new literature evidences. I never met anyone so eager to learn. For this reason unexpectedly it turned out as a great opportunity to foster my teaching experience.

A surgical resident added: “Teaching in Costa Rica was a very rewarding experience. The confidence I gained in my surgical ability was greatly increased by being able to successfully teach others.” By teaching, residents felt as if they were contributing to the host institutions. One ophthalmology resident wrote, “The fundamental goal of each mission is not to sweep into a given country and perform as many surgeries as possible. Rather, its goal is primarily attaining a sustainable transfer of knowledge and skill.” Being able to teach gave residents a feeling of confidence, developed their teaching skills, and gave them a sense that they were contributing to the institutions that hosted them.

Personal Benefits

Residents mentioned a number of key personal benefits. Many benefited from experiencing new people, cultures, ideas, and ways of thinking. One internal medicine resident summed up the impact of the experience by saying:

More important than their diseases were the patients themselves. The patients introduced me to a culture that, despite extreme poverty, is enriched by strong family values and a sense of community. I was impressed by how willing and eager people were to help each other. I have never met patients so gracious, so in need, as these. It was extremely gratifying to administer health care to this community.

Along with this, various adjectives were used by residents to describe the experience, including life-changing, humbling, and eye-opening; they “grew” from this experience and “were changed.” Of the residents, 26% explicitly stated that they were grateful for the experience; another 27% stated that they had a desire to return. One internal medicine resident described the rotation as “one of the most profound experiences of my three years of medical residency training.” The personal impact of these experiences on the residents was evident.

Negative Themes

Although most of the themes and responses identified in the reports were positive, words like frustrating, difficult, and challenging were used throughout the reports in conjunction with many of the otherwise positive themes. These were often incorporated by acknowledging the challenges that accompanied overall positive observations. For instance, one internal medicine resident discussed dealing with limited resources:

One of the most difficult things that I experienced while in Malawi was…the feeling of helplessness as I cared for these two young children and being unable to provide the medical care that I knew they needed…[it] was as an exceptional experience in international health. It provided an opportunity for me to see and understand first hand the struggles, frustrations and also the successes of providing health care in a developing country.

Although at times overwhelming, many of the challenges that residents faced laid the groundwork for greater overall learning.

The negative impacts on residents' educational experience were identified in less than 10% of responses. Although 1 theme identified concern for general safety and health (n=11), no serious incidents regarding safety or health occurred among our residents. Residents reported difficulty adjusting to cultural differences (n=7) or health systems (n=7; eg, paternalistic approaches, hierarchies of medical teams), and some noted difficulty adjusting after return to the United States (n=2). Some residents were overwhelmed by the severity of illness (n=8) or the number of patients they were asked to see (n=6), balanced by the frustration that yet more patients needed to be seen. These negative impacts were minor but not insignificant.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, our study is the first that has used systematic qualitative methods to evaluate residents' opinions about the benefits of international experiences during graduate medical education. The qualitative methodology allowed us to evaluate responses to open-ended questions, leading to a broad variety of themes and a deeper understanding of previously published numerical survey data on residents' international elective experiences.4,5 Previous studies have addressed the effects of international health electives on the educational and professional development of medical students and residents and have assessed electives' impact on their skills, attitudes, and knowledge.3-7 In one review of 7 studies involving 522 medical student participants and 166 resident participants, survey data suggested that international health electives (1) affected participants' future career choice in primary care and underserved care, (2) improved clinical skills, (3) changed attitudes toward health care delivery in underserved communities, and (4) provided knowledge of topics in tropical diseases.3 Narrative information from the postrotation resident reports in our own study further supports the educational benefits of participation in an international health elective during residency. From this analysis, the MIHP is meeting its goals of providing care to underserved populations and valuable learning experiences to residents. Our findings agree with and add to the previous literature,3-7 which suggested considerable educational benefit from these rotations, demonstrating the variety of benefits across several specialties.

This study has shown the numerous ways in which international experiences benefited residents' formal education and personal lives. Important educational benefits included experience with a variety of pathology, experience working with limited resources, improvement in clinical and surgical skills, and opportunities for involvement with resident education. This study highlights the importance of direct experience with unfamiliar disease processes, health systems, and cultures in medical education, highlighting the challenges that they present. International health electives provide unique experiences and are perceived by residents to enhance skills and knowledge of global health topics and clinical skills.

Very few negative impacts were identified by residents participating in international rotations. Possible reasons for this include the way in which the questions were asked (negative impacts were not specifically elicited) and residents' discomfort in reporting potential negative impacts. However, the program prepares residents for health and safety issues by requiring a travel clinic appointment and a review of the US Department of State Web site safety warnings before the elective. The MIHP does not currently have any curriculum in place to help prepare for some of the other concerns addressed by a few residents, particularly regarding adjustment to cultural and medical practices in the sites that they are visiting. In this way, our study identifies areas for further curriculum development.

Whether programs like the MIHP result in long-term behavioral change among participating residents is an important question. We anticipate that international experiences will change residents' future behavior, leading them to practice more cost-effective medicine, adjust resource use, improve surgical skills, and do more international work. Indeed, at least 4 MIHP alumni have demonstrated commitment to long-term care for the underserved in international settings after their training by pursuing extended work abroad, including 2 who began a clinic to care for the underserved in the country of their MIHP elective. A systematic survey to more comprehensively assess behavior changes among MIHP alumni is beyond the scope of our current investigation but is an area of anticipated future study.

Providing global health training during graduate medical education can pose several challenges both for the residency administration and for the residents involved.15 Residency programs have difficulty providing financial and administrative support for international experiences. Residents have financial and scheduling constraints, including time spent away from family and difficulty finding host programs. These all present barriers for participation, barriers that are worth surmounting (eg, by providing a structure for participating in rotations and, if possible, offsetting residents' travel costs) given our study's findings of the considerable benefits residents derive from international electives.

Our study has limitations. All of the authors are employed at the MIHP's home institution and play some role in the formal education of its residents. Narrative reports were requested from residents, not provided by them spontaneously. Residents were asked to write at least 1 page, and the wording of the request, although open-ended, takes for granted that residents were affected in some way and does not specifically ask for potential negative impacts. Text was analyzed in its entirety for the purpose of this study by only 1 author (A.P.S.), with a second author reviewing a representative sample of the reports; an acceptable degree of agreement was reached regarding the analysis of the main themes. Although we used NVivo7 software to help organize selected themes and quantify responses, other potentially meaningful themes may have been excluded. Conclusions derived from this analysis reflect the experience of the participants in the MIHP's first 8 years only.

DIRECTIONS FOR FUTURE STUDIES

A number of important research questions remain regarding international health experiences in resident medical education: Are residents who have participated in such programs more comfortable in caring for people of different ethnic backgrounds? Are they more likely than their counterparts to care for the underserved after their training is complete? Are they happier? Are these residents less likely to order unnecessary diagnostic tests and/or invasive studies? Do they have common backgrounds that lead them to this sort of program? Do they perform better on examinations covering tropical diseases and other illnesses more common in the developing world? Do they perform better on clinical examination skill testing? Do they receive better evaluations as educators? The qualitative data provide a substrate for further evaluation of how international health electives affect resident behavior and knowledge.

The systems-based practice question generated very heterogeneous responses that were not included in this study. For future research, this question needs to be revised to obtain more specific responses given the importance of resident competency in systems-based practice.

Finally, we know of no published analysis of the impact that international rotations have on the countries in which the residents serve. A well-designed survey of overseas mentors would be useful in determining the benefit and harm of these programs. Such information would assist international health programs like the MIHP in better preparing residents and organizing their experiences. We acknowledge that a variety of investigative techniques, including formal ethnography, could provide valuable information.

CONCLUSION

International health electives are an important part of residency education. These rotations have provided many educational and personal benefits to residents in many specialties, offering a fresh perspective on health care delivery and enhancing clinical and medical decision-making skills. The MIHP has provided financial and administrative support to residents, facilitating resident participation in these electives and furthering the overall goals of resident education. The benefits of international electives for resident growth and education are worthy of further support by residency programs and should prompt the development of similar initiatives in other residency programs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms Michelle L. Pederson, Mayo International Health Program Coordinator, for her assistance in gathering the data.

Footnotes

This work was supported in part by the Mayo Clinic Internal Medicine Residency Office of Educational Innovations as part of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Educational Innovations Project.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Medical Association AMA-RSF resources: international opportunities during residency. American Medical Association Web site http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/about-ama/our-people/member-groups-sections/resident-fellow-section/rfs-resources/international-residency-opportunities.shtml Accessed June 25, 2010

- 2.Bazemore AW, Henein M, Goldenhar LM, Szaflarski M, Lindsell CJ, Diller P. The effect of offering international health training opportunities on family medicine residency recruiting. Fam Med. 2007;39(4):255-260 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson MJ, Huntington MK, Hunt DD, Pinsky LE, Brodie JJ. Educational effects of international health electives on U.S. and Canadian medical students and residents: a literature review. Acad Med. 2003;78(3):342-347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gupta AR, Wells CK, Horwitz RI, Bia FJ, Barry M. The International Health Program: the fifteen-year experience with Yale University's internal medicine residency program. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;61(6):1019-1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller WC, Corey GR, Lallinger GJ, Durack DT. International health and internal medicine residency training: the Duke University experience. Am J Med. 1995;99(3):291-297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiller TM, De Mieri P, Cohen I. International health training: the Tulane experience. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1995;9(2):439-443 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pust RE, Moher SP. A core curriculum for international health: evaluating ten years' experience at the University of Arizona. Acad Med. 1992;67(2):90-94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mayo School of Graduate Medical Education The Mayo International Health Program. Mayo Clinic Web site http://www.mayo.edu/msgme/mihp.html Accessed June 25, 2010

- 9.St. Mary's Mission Hospital Web sites http://www.stmarysmissionhospital.org and http://www.maryknollafrica.com/Health-Fryda.htm Accessed June 29, 2010

- 10.Hospital Albert Schweitzer Web site. http://www.hashaiti.org/ http://www.hashaiti.org/ Accessed June 25, 2010.

- 11.Patan Hospital Web site. http://www.patanhospital.org.np/ http://www.patanhospital.org.np/ Accessed June 25, 2010.

- 12.IHPTZ.Org International Health Partners US-TZ Web site. http://www.ihptz.org/ http://www.ihptz.org/ Accessed June 25, 2010.

- 13.US Department of State Travel.State.Gov. Web site. http://travel.state.gov/ http://travel.state.gov/ Accessed June 25, 2010.

- 14.Wickhan M, Woods M. Reflecting on the strategic use of CAQDAS to manage and report on the qualitative research process. Qual Rep. 2005;10(4):687-702 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drain PK, Holmes KK, Skeff KM, Hall TL, Gardner P. Global health training and international clinical rotations during residency: current status, needs, and opportunities. Acad Med. 2009;84(3):320-325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.